Abstract

We sought to examine whether the presence of a non-cancer pain condition is independently associated with an increased risk for suicidal ideation, plan, or attempt after adjusting for socio-demographic and psychiatric risk factors for suicide, and whether risk differs by specific type of pain. We analyzed data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, a household survey of U.S. civilian adults age 18 years and older (n=5692 respondents). Pain conditions, non-pain medical conditions, and suicidal history were obtained by self report. DSM-IV mood, anxiety and substance use disorders were assessed using the World Health Organization’s Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Antisocial and borderline personality traits were assessed with the International Personality Disorder Examination screening questionnaire. In unadjusted logistic regression analyses, the presence of any pain condition was associated with lifetime and 12-month suicidal ideation, plan, and attempt. After controlling for demographic, medical and mental health covariates, the presence of any pain condition remained significantly associated with lifetime suicidal ideation (odds ratio [OR] 1.4, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1–1.8) and plan. Among pain subtypes, severe or frequent headaches and ‘other’ chronic pain remained significantly associated with lifetime suicidal ideation and plan; ‘other’ chronic pain was also associated with attempt.

PERSPECTIVE

The risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviors that may accompany back, neck and joint pain can be accounted for by co-morbid mental health disorders. There may be additional risk accompanying frequent headaches and ‘other’ chronic pain that is secondary to psychosocial processes not captured by the mental disorders assessed.

Keywords: Suicide, pain, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is the 11th leading cause of death and the seventh leading cause of potential years of life lost in the United States 13. Known risk factors for suicide include socio-demographic factors (age, gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, non-religiosity), presence of a psychiatric illness, and comorbid medical conditions 10, 13, 25, 33. Prior studies suggest an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in individuals with non-cancer pain conditions 35. Prevalence rates have come primarily from specialty pain centers and range from 5–24% for current and 5.2–50% for lifetime suicidal ideation 35. It is unknown how these studies apply to the broader population with pain. Furthermore, these studies have not adjusted for other suicide risk factors, particularly depression, anxiety, and substance abuse: conditions found commonly in individuals with non-cancer pain conditions.

A few studies have examined population-based risk for suicidal ideation and attempts in persons with pain. Magni et al found significantly increased lifetime suicidal thoughts and attempts in respondents to the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey with chronic abdominal pain after adjusting for age, gender, marital status, poverty index and CES-D score 24. In a survey of HMO members age 21–30 years, Breslau found the presence of lifetime migraine with aura to be significantly associated with an increased likelihood of lifetime suicidal thoughts and attempts after adjusting for comorbid mania, dysthymia, anxiety disorder or substance use disorder 5. Druss and Pincus did not find a significant association between lifetime suicidal ideation or attempt and arthritis among respondents age 17 to 39 years to the 1988–94 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, after adjusting for major depression, history of heavy alcohol use, and socio-demographic variables(3). These studies focused on individuals with specific pain conditions, making it difficult to extrapolate to chronic pain conditions in general. More recently, Ratcliffe et al found a significant association between the presence of migraine, arthritis, back problems, or fibromyalgia and 12-month suicidal ideation or attempt among respondents to the Canadian Community Health Survey, after controlling for mood/anxiety disorders, substance dependence, and socio-demographic variables 26.

In this study, we sought to examine the association of common non-cancer pain conditions (arthritis/rheumatism, chronic back or neck problems, frequent or severe headaches, and other chronic pain) with increasing levels of suicidality (lifetime and 12-month ideation, plan, attempt) using data from a population-based survey of U.S. adults, and adjusting for other known socio-demographic and clinical risk factors for suicide. Specifically, we sought to answer the following questions:

Is the presence of non-cancer pain independently associated with an increased risk for suicidal ideation, plan, or attempt after adjusting for the effects of comorbid mood, anxiety and physical health disorders, substance abuse disorders, selected personality traits, and socio-demographic risk factors for suicide?

Do specific pain conditions differ in their associated risks for suicidal ideation, plan, or attempt?

A summary of findings from these analyses was presented as a poster at the May 2008 American Pain Society meeting3.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Source

Data are from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R), a household survey of English-speaking U.S. adults (age 18 years or older) carried out between February 2001 and April 2003. The sample was based on a multi-stage clustered area probability sampling design representative of the U.S. civilian population; response rate was 70.9%. The survey was administered in two parts. Part I was administered to all 9282 respondents and included all core diagnostic assessments. Part II included questions about risk factors, consequences, other correlates, and additional disorders, and was administered to 5692 respondents, including all who met lifetime criteria for at least one mental disorder assessed in Part I, met subthreshold lifetime criteria for any of these disorders and sought treatment, or ever made a suicide plan or attempt, as well as a probability sample of other respondents to Part I. Informed consent was obtained verbally before the interview, and the study was approved by the institutional review boards at Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan. Details of the NCS-R study design and methods can be found elsewhere 18, 19. Data for the analyses reported here come from the public use data set for the Part II sample. Excluding missing responses for questions assessing the presence of lifetime pain conditions and suicidal ideation left a total of 5681 and 5677 responses, respectively, available for the analyses described here.

Variables

Pain and Other Medical Conditions

Lifetime chronic medical conditions were assessed by self report with the question, “Have you ever had any of the following?” followed by a list of 15 conditions. For the purpose of this study, a self-reported pain condition was defined as a positive response to any of the following conditions which commonly involve pain: arthritis/rheumatism, chronic back or neck problems, frequent or severe headaches, or ‘other’ chronic pain. This definition is consistent with prior published reports using data from NCS-R32, 36, and with the WHO Collaborative Study of Psychological Problems in General Health Care15. In the latter study, back pain, headache, and joint pain were the three most commonly reported anatomical pain sites among those with pain persisting six months or longer. A positive response to any of the following was considered a non-pain chronic condition: seasonal allergies, stroke, heart attack, heart disease, high blood pressure, asthma, other chronic lung disease, diabetes or high blood sugar, ulcer in the stomach or intestine, epilepsy or seizures, or cancer. An estimate of pain duration in years was defined as age the respondent reported first having the condition subtracted from current age; if these two ages were equivalent, pain duration was defined as 0.5 years. NCS-R also asked if the condition was still present in the prior 12 months for some of the conditions, including all of the pain conditions except arthritis/rheumatism. For the purpose of this study, a 12-month pain condition was defined as those reporting ever having arthritis or those reporting diagnosis or treatment for the other pain conditions in the past 12 months. Most respondents endorsing any lifetime pain condition (99.9%) also endorsed a 12-month pain condition, although not necessarily the same type of pain condition (e.g., 55.9% of those endorsing lifetime headaches endorsed 12-month headaches).

Functioning and Disability

The World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale (WHO-DAS) assesses both the persistence and severity of difficulties in the respondent’s functioning in five domains (mobility, self care, social, cognitive, and role functioning) during the 30 days before the interview due to all physical and mental health problems. Total score and subscale scores range from 0–100, with higher scores reflecting greater disability 8. Respondents were also asked how often they have trouble falling or staying asleep. For this study, responses were dichotomized as ‘nearly all the time’ or ‘pretty often’ vs. ‘not very much’ or ‘never.’ Respondents were also asked how often they experienced “physical discomfort, such as pain, nausea, or dizziness in the past 30 days” and the severity of that discomfort, on average. For purposes of this study, responses were dichotomized based on endorsement of severe physical discomfort.

Mental Health and Substance Abuse

Lifetime and 12-month DSM-IV mental health and substance use disorders were assessed with the World Mental Health Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) 20. For the purposes of this study, anyone meeting criteria for a major depressive episode, dysthymia, bipolar 1, bipolar 2, panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and/or post-traumatic stress disorder was defined as having a mood or anxiety disorder. Anyone meeting criteria for alcohol and/or drug abuse or dependence was defined as having an alcohol or drug use disorder. The NCS-R interview did not assess respondents for all DSM-IV personality disorder criteria, but did include a subset of questions from the International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE) screening questionnaire, including all of the screening questions for borderline (BPD) and antisocial personality disorders (APD) 22. The IPDE screening questionnaire is designed to have high sensitivity but low specificity, and is therefore expected to produce a considerable number of false-positive but relatively few false-negative classifications with respect to the IPDE Interview23. Consistent with the scoring of the IPDE screening questionnaire, we defined endorsement of three or more items for BPD or APD as a positive screen. These two personality disorders have been associated with suicidal ideation and behavior in prior studies 21, 25. Psychological distress was assessed using the K10 scale 6, 16. The 10 questions in the K10 scale use a 5-point Likert scale and ask respondents how frequently they experienced symptoms of psychological distress (eg, feeling so sad that nothing can cheer you up) during the past 30 days. This reference period was modified in NCS-R to "the one month in the past 12 months when you were at your worst emotionally.” K10 was scored on a 0–40 scale, with higher scores indicating greater distress.

Suicidality

Suicidality was assessed in NCS-R with questions asking if the respondent ever seriously thought about committing suicide, made a plan for committing suicide, or attempted suicide. Follow-up questions assessed whether any of these happened in the prior 12 months. Based on evidence that reports of embarrassing behaviors are higher in self-administered than in interviewer-administered surveys, questions about suicide were printed in a self-administered booklet and referred to by letter, or read to respondents unable to read.

Data Analysis

Weights designed by NCS-R staff adjusted for differential probabilities of selection, over-sampling of Part I respondents with a mental disorder, and were used to make the data representative of the U.S. population 18. In our descriptive analyses, statistical differences were assessed with chi square statistic for categorical variables or F statistic for continuous variables. Logistic regression analysis was used to estimate odds ratios for suicidal ideation, plan or attempt, while controlling sequentially for socio-demographic covariates (age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, education level, religious affiliation, log-transformed household income), medical conditions (number of non-pain chronic conditions), presence of a mood or anxiety disorder, presence of an alcohol or drug use disorder, and a positive screen for APD or BPD personality traits. The covariates and order in which they were added to the models were determined a priori based on known risk factors for suicide; with the expectation that mental disorders would account for the largest, most clinically modifiable risk. In the case of non-dichotomous categorical covariates, dummy variables were created for use in the models. When assessing the independent effects of specific pain conditions, the other pain conditions were included as medical covariates. For variables defined as lifetime or 12-month, the appropriate correlate to the outcome of interest was used (e.g., lifetime covariates when assessing lifetime suicidality). The models used for the logistic regression analyses are summarized in the table in Appendix A. All analyses were based on weighted data, controlled for stratification and clustering, and were conducted using SAS version 9.1.3 (Cary, NC) procedures for survey sampling; these procedures use the Taylor expansion method to estimate sampling errors of estimators based on complex sample designs. Statistical significance was evaluated with two-tailed tests (p<0.05).

RESULTS

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

Tables 1 and 2 describe the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of NCS-R respondents by presence of a lifetime self-reported pain condition. Individuals with a lifetime pain condition differed significantly on all variables examined except for religion when compared to those without a lifetime pain condition.

Table 1.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents with or without Self-Reported Pain Conditions

| N, weighted % | With Lifetime Self-Reported Pain | Without Lifetime Self-Reported Pain (N=2298) | P Value | χ2/F | df | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, Female | 2133 | 58.6% | 1176 | 46.6% | <0.001 | 46.8 | 1 |

| Age Group | <0.001 | 119.39 | 2 | ||||

| 18–44 years | 1641 | 42.7% | 1556 | 63.6% | |||

| 45–64 years | 1221 | 36.1% | 564 | 25.0% | |||

| 65 years and older | 529 | 21.2% | 178 | 11.4% | |||

| Race/Ancestry | <0.001 | 22.14 | 4 | ||||

| Non-Latino White | 2547 | 76.3% | 1630 | 68.6% | |||

| African-American or Afro-Caribbean | 401 | 10.8% | 316 | 14.2% | |||

| Hispanic | 283 | 9.4% | 244 | 13.0% | |||

| Asian | 34 | 1.0% | 49 | 2.5% | |||

| Other | 126 | 2.5% | 59 | 1.8% | |||

| Education | <0.001 | 28.18 | 3 | ||||

| 0–11 years | 570 | 19.3% | 279 | 13.8% | |||

| 12 years | 1050 | 33.5% | 660 | 31.2% | |||

| 13–15 years | 1011 | 27.2% | 698 | 28.0% | |||

| 16 years or more | 760 | 19.9% | 661 | 26.9% | |||

| Marital Status | <0.001 | 109.33 | 2 | ||||

| Married/cohabiting | 1948 | 58.2% | 1287 | 53.4% | |||

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 870 | 25.2% | 368 | 15.6% | |||

| Never married | 573 | 16.6% | 643 | 30.9% | |||

| Household Income, Mean ± SE | $55,765 | ±1,425.7 | $63,374 | ±2,312.4 | 0.001 | 13.42 | 1, 42 |

| Religion | 0.13 | 5.70 | 3 | ||||

| Protestant | 1837 | 55.3% | 1154 | 51.8% | |||

| Catholic | 766 | 23.0% | 572 | 26.7% | |||

| No religion | 503 | 14.2% | 378 | 14.1% | |||

| Other | 276 | 7.5% | 182 | 7.4% | |||

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of Respondents with or without Self-Reported Pain Conditions

| N, weighted % | With Lifetime Self-Reported Pain (N=3391) | Without Lifetime Self-Reported Pain (N=2298) | P Value | χ2/F* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain Type | ||||||

| Arthritis | 1588 | 51.0% | ………………… | ……………… | …………. | |

| Chronic back/neck problems | 1905 | 54.7% | ………………… | ……………… | …………. | |

| Frequent or severe headaches | 1660 | 42.5% | ………………… | ……………… | …………. | |

| Other chronic pain | 706 | 17.9% | ………………… | ……………… | …………. | |

| Number of chronic pain conditions, mean, ±SE | 1.7 | ±0.02 | ………………… | ……………… | …………. | |

| Number of Non-Pain Chronic Conditions, Mean, ±SE | 1.4 | ±0.03 | 0.8 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 222.78 |

| Mental Health/Substance Abuse | ||||||

| Mood or anxiety disorder | ||||||

| Lifetime | 1928 | 39.1% | 947 | 22.9% | <0.001 | 95.79 |

| 12-month | 1147 | 22.8% | 482 | 11.2% | <0.001 | 120.07 |

| Alcohol or drug use disorder | ||||||

| Lifetime | 710 | 16.3% | 434 | 12.8% | 0.005 | 7.73 |

| 12-month | 144 | 3.5% | 139 | 4.2% | 0.23 | 1.42 |

| Positive screen for borderline or antisocial personality traits | 1208 | 27.4% | 614 | 18.6% | <0.001 | 44.16 |

| Psychological distress, mean K10 score†, ±SE | 13.4 | ±0.3 | 10.7 | 0.3 | <0.001 | 51.01 |

| Suicidality | ||||||

| Seriously considered | ||||||

| Lifetime suicidal ideation | 912 | 19.3% | 432 | 11.4% | <0.001 | 57.48 |

| 12 month | 155 | 3.3% | 74 | 1.8% | 0.002 | 9.74 |

| Made a suicide plan | ||||||

| Lifetime | 366 | 7.2% | 138 | 3.4% | <0.001 | 34.17 |

| 12 month | 52 | 1.1% | 16 | 0.4% | <0.001 | 11.89 |

| Made an suicide attempt | ||||||

| Lifetime | 331 | 6.6% | 137 | 3.3% | <0.001 | 36.72 |

| 12 month | 34 | 0.7% | 15 | 0.3% | 0.022 | 5.23 |

Degrees of freedom=1 for categorical variables; 1,42 (F test) for continuous variables

Level of distress for the month in the past year when at worst, emotionally; scores range from 0–40, with higher scores indicative of greater distress

Individuals with a lifetime pain condition differed significantly on all clinical variables except for 12-month alcohol or drug disorder when compared to those without a lifetime pain condition. Within the pain group, those with lifetime suicidal ideation were more likely to have lifetime frequent or severe headaches and/or ‘other’ chronic pain condition, but less likely to have arthritis, and had a higher mean number of pain conditions compared to those without lifetime suicidal ideation (data not shown). Mean duration of the pain condition in years ranged from 13.1 (arthritis) to 18.4 (frequent or severe headaches) and did not differ significantly by presence of lifetime suicidal ideation (data not shown).

‘Other’ Chronic Pain (data not shown)

Most of those with ‘other’ chronic pain had more than one lifetime pain condition (78.6%, compared to 39.1% of those with arthritis, chronic back/neck problems, and/or headaches, χ2 (1) =209.58, p<0.001). Compared to those with lifetime chronic back/neck problems (the pain group most similar to the ‘other’ chronic pain group in age and gender), those endorsing ‘other’ chronic pain had a higher mean number of pain conditions (2.5 vs. 1.8, F=130.60 (1, 42), p<0.001), and greater disability as measured by WHO-DAS scores (role impairment 10.6 vs. 6.9, F=12.44 (1, 42), p=0.001). They were also more likely to meet criteria for a lifetime mood or anxiety disorder (50.1% vs. 39.1%, χ2(1)=16.51, p<0.001), screen positive for borderline or antisocial traits (36.3% vs. 27.2%, χ2(1)=14.19, p<0.001), and have greater psychological distress (K10) scores (15.1 vs. 13.2, F1,42=10.61, p=0.002).

Odds of Suicidality in Those with Self-Reported Pain Conditions

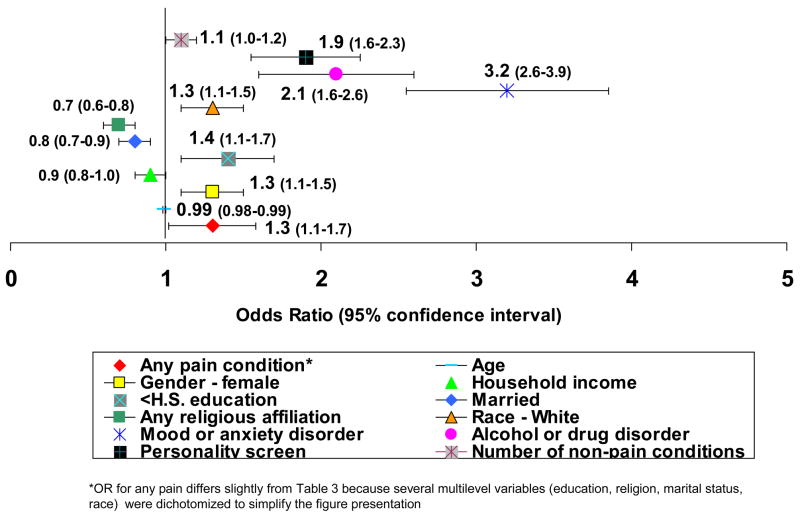

Tables 3 and 4 list the results of logistic regression analyses examining the associations between self-reported pain conditions and serious suicidal ideation, plan and attempt. Table 3 lists odds ratios for lifetime suicidality associated with having any (lifetime) pain condition, and for each of the four pain conditions, individually. Table 4 lists odds ratios for 12-month suicidality associated with having any pain condition in the past 12 months. Results for individual pain conditions were unstable due to small N’s and are therefore not presented. Results for model covariates were consistent with that reported previously in the literature and are presented in Figure 1 17, 25. Having a mood or anxiety disorder was the most significant clinical predictor of lifetime suicidal ideation, followed by an alcohol or drug use disorder and borderline or antisocial personality traits.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Models*: Odds of Lifetime Suicidality in Adults by Presence of Self-Reported Pain Conditions

| Arthritis/Rheumatism (N=1583) | Chronic Back/Neck Problems (N=1899) | Severe or Frequent Headaches (N=1660) | Other Chronic Pain (N=704) | Any Self-Reported Pain, Lifetime (N=3383) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio, 95% confidence interval | ||||||||||

| Suicidal Ideation | ||||||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.2† | 1.0–1.4 | 1.7§ | 1.5–2.0 | 2.4§ | 2.0–2.8 | 2.3§ | 1.8–2.9 | 1.9§ | 1.6–2.2 |

| Adjusted: Step 1 | 1.7§ | 1.4–2.1 | 1.9§ | 1.6–2.2 | 2.2§ | 1.8–2.5 | 2.4§ | 1.9–3.0 | 2.1§ | 1.8–2.6 |

| Step 2 | 1.2 | 1.0–1.5 | 1.4§ | 1.2–1.6 | 1.7§ | 1.4–2.0 | 1.7§ | 1.3–2.2 | 1.9§ | 1.6–2.4 |

| Step 3 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.4 | 1.2 | 1.0–1.4 | 1.3† | 1.1–1.6 | 1.4‡ | 1.1–1.8 | 1.4‡ | 1.1–1.8 |

| Step 4 | 1.1 | 0.9–1.4 | 1.1 | 0.9–1.3 | 1.3† | 1.0–1.5 | 1.4‡ | 1.1–1.8 | 1.4‡ | 1.1–1.8 |

| Suicide Plan | ||||||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.2† | 1.0–1.5 | 2.1§ | 1.6–2.7 | 3.0§ | 2.3–3.8 | 3.2§ | 2.4–4.1 | 2.2§ | 1.7–2.8 |

| Adjusted: Step 1 | 2.0§ | 1.5–2.6 | 2.3§ | 1.7–3.0 | 2.7§ | 2.1–3.5 | 3.3§ | 2.4–4.5 | 2.6§ | 1.9–3.4 |

| Step 2 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.6 | 1.5‡ | 1.1–1.9 | 1.9§ | 1.5–2.5 | 2.1§ | 1.6–2.9 | 2.2§ | 1.6–3.0 |

| Step 3 | 1.1 | 0.9–1.4 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.6 | 1.5‡ | 1.2–2.0 | 1.8§ | 1.4–2.4 | 1.6‡ | 1.2–2.2 |

| Step 4 | 1.1 | 0.9–1.4 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.6 | 1.5‡ | 1.1–1.9 | 1.8§ | 1.3–2.4 | 1.5‡ | 1.1–2.1 |

| Suicide Attempt | ||||||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.4‡ | 1.1–1.7 | 2.2§ | 1.7–2.8 | 2.7§ | 2.1–3.4 | 3.5§ | 2.7–4.5 | 2.1§ | 1.6–2.6 |

| Adjusted: Step 1 | 2.2§ | 1.6–2.9 | 2.4§ | 1.9–3.1 | 1.2§ | 1.1–1.3 | 3.7§ | 2.9–4.8 | 2.3§ | 1.8–3.0 |

| Step 2 | 1.4† | 1.0–1.8 | 1.6§ | 1.3–2.1 | 2.1† | 1.6–2.8 | 2.4§ | 1.9–3.1 | 2.0§ | 1.5–2.5 |

| Step 3 | 1.2 | 1.0–1.6 | 1.3 | 1.0–1.6 | 1.0 | 0.8–1.4 | 2.2§ | 1.7–2.7 | 1.3† | 1.0–1.7 |

| Step 4 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.5 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.6 | 1.0 | 0.7–1.4 | 2.2§ | 1.7–2.7 | 1.3 | 1.0–1.7 |

Covariates:

Step 1: Sociodemographic factors (age, gender, race/ancestry, marital status, education status, religion, log-transformed income)

Step 2: Sociodemographic factors, medical factors (all other self-reported pain conditions [i.e., arthritis, back/neck pain, headaches, ‘other’ pain], number of non-pain chronic conditions [range=0–11]; for “any pain” column, adjustment for medical conditions includes only number of non-pain chronic conditions)

Step 3: Sociodemographic and medical factors, lifetime mood or anxiety disorder, lifetime alcohol or drug abuse/dependence, K10 score

Step 4: Sociodemographic and medical factors, lifetime mood or anxiety disorder, lifetime alcohol or drug abuse/dependence, K10 score, personality screen

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Models*: Odds of Past Year Suicidality in Adults by Presence of Self-Reported Pain Conditions

| Any Self-Reported Pain Conditions in Past Year|| (N=2782) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio 95% | confidence interval | |

| Suicidal Ideation | ||

| Unadjusted | 2.0‡ | 1.3–3.0 |

| Adjusted: Step 1 | 2.8§ | 1.7–4.7 |

| Step 2 | 2.4‡ | 1.4–4.0 |

| Step 3 | 1.6 | 0.9–2.6 |

| Step 4 | 1.4 | 0.8–2.4 |

| Suicide Plan | ||

| Unadjusted | 2.9§ | 1.6–5.3 |

| Adjusted: Step 1 | 4.1§ | 1.9–8.6 |

| Step 2 | 3.1† | 1.4–6.6 |

| Step 3 | 1.9 | 0.9–3.7 |

| Step 4 | 1.6 | 0.8–3.2 |

| Suicide Attempt | ||

| Unadjusted | 2.5‡ | 1.3–4.7 |

| Adjusted: Step 1 | 3.8§ | 1.8–7.9 |

| Step 2 | 2.8 | 1.4–5.8 |

| Step 3 | 2.2† | 1.0–4.8 |

| Step 4 | 1.9 | 0.8–4.4 |

Covariates:

Step 1: Sociodemographic factors (age, gender, race/ancestry, marital status, education status, religion, log-transformed income)

Step 2: Sociodemographic factors, medical factors (number of non-pain chronic conditions [range=0–11])

Step 3: Sociodemographic and medical factors, 12-month mood or anxiety disorder, 12-month alcohol or drug abuse/dependence, K10 score

Step 4: Sociodemographic and medical factors, 12-month mood or anxiety disorder, 12-month alcohol or drug abuse/dependence, K10 score, personality disorder screen

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Includes those reporting ever having arthritis and those reporting diagnosis or treatment for chronic back/neck problems, frequent or severe headaches, or other chronic pain in the past 12 months

Figure 1.

Odds of Lifetime Suicidal Ideation by Presence of Sociodemographic, Psychiatric and Medical Risk Factors

Any pain condition and each of the individual pain conditions were significantly associated with increased lifetime suicidal ideation, plan and attempt in models adjusting only for socio-demographic covariates (Table 3). When medical covariates were added to the models, arthritis was no longer significantly associated with suicidality, and when lifetime mood or anxiety disorder and lifetime alcohol or drug use disorder were added, chronic back/neck problems were no longer significant. In the final models, the presence of any pain condition remained significantly associated with lifetime suicidal ideation and plan, and ‘other’ chronic pain remained significantly associated with ideation, plan and attempt. Severe or frequent headaches were significantly associated with lifetime suicidal ideation and plan but not attempt. The presence of any self-reported pain condition was associated with an approximately 40% additional increase in risk of lifetime suicidal ideation, plan or attempt, and the presence of ‘other’ chronic pain more than doubled the odds of reporting a lifetime suicide attempt.

Any pain condition in the past year was significantly associated with 12-month suicidal ideation, plan and attempt in models adjusting only for socio-demographic covariates, but in the fully adjusted models, these associations were no longer statistically significant (Table 4). In sensitivity analyses, we re-ran the models for Table 4 after removing arthritis from the definition of a 12-month pain condition (data not shown). This resulted in a slight increase in risk estimates that did not change the significance of the results. We also examined number of pain conditions as a predictor of suicidality (data not shown). Odds ratio estimates were similar to those for any pain condition, and number of pain conditions was also significantly associated with lifetime (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.2–1.4, χ2 (1)=18.34) and 12-month suicide attempt (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.1–2.0, χ2 (1)=8.33).

In stratified analyses (data not shown), ‘other’ chronic pain remained significantly associated with lifetime suicide plan and attempt in those with or without a lifetime mood or anxiety disorder. Any pain condition and each of the other pain conditions, however, were not significantly associated with lifetime suicidality in those without a lifetime mood or anxiety disorder. We also tested for effect modification between mood or anxiety disorder and pain condition (any and specific types), but interaction terms for lifetime and 12-month disorders were not significantly associated with suicidal ideation or attempt (data not shown).

We performed secondary analyses to investigate other variables hypothesized as potentially linking suicidality and pain. Adding WHO-DAS scores to the models had little effect on the associations between ‘other’ chronic pain or any pain condition with lifetime suicidal ideation or plan, but the association between headaches and lifetime suicidal ideation was no longer significant. Alternatively, adding presence of sleep disturbance or severe physical discomfort resulted in small changes in odds ratio estimates, but did not change the significance of the results. We also considered pain associated with cancer. Less than 10% of respondents endorsed a lifetime history of cancer, and 86% of those reported they were cured or in remission at the time of the NCS-R interview. Sensitivity analyses excluding those with cancer from the logistic regression models did not significantly change the results.

DISCUSSION

Results of this study demonstrate an association between self-reported pain conditions and lifetime suicidal thoughts and behavior, independent of the effects of comorbid mood, anxiety, substance use disorders, selected personality traits, and socio-demographic risk factors for suicide. Findings are consistent with prior population-based studies that have found suicidal thoughts and behaviors to be associated with migraine headaches 5 and abdominal pain 24, and add to these studies by examining the effects of specific common pain conditions and adjusting for additional risk factors for suicide. In contrast to the recent analysis by Ratcliffe et al.26, we did not find a significant association between the self-reported presence of any of the pain conditions queried and 12-month suicidality once results were adjusted for psychiatric covariates. This may be a reflection of the additional psychiatric diagnoses included as covariates in our analyses. In addition, the Canadian Community Health Survey included fibromyalgia as a pain condition and interviewed individuals age 15 years and older versus 18 years and older for NCSR.

Consistent with prior studies 2, 32, 36, psychiatric comorbidity was common among individuals with a pain condition. Pain, depression, and disability are known to be mutually reinforcing from prospective epidemiological studies 14. The disappearance of the significant associations between chronic back/neck problems and lifetime suicidality, and between any pain condition and 12-month suicidality, once results were adjusted for mood/anxiety and substance abuse disorders highlights the importance of identifying and treating comorbid psychiatric disorders in this population.

Multiple pain conditions have been shown to be more strongly associated with psychopathology than single pain conditions 11. Some of this psychopathology may not have been captured by NCS-R. While NCS-R did include a personality screener, this did not account for all personality disorder types. In addition, NCS-R did not assess for somatoform disorders, conditions associated with increased risk for suicidal behavior 7, 21, 25, 29 and increased likelihood of multiple pain conditions 9, 27, 28. The measure of psychological distress included in this study (K10) assessed symptoms within the past year, and thus may not have adequately captured the level of emotional distress experienced prior to lifetime suicidal ideation and behaviors. Chronic pain exerts a significant and enduring negative effect on self-reported health status that is not generally seen with non-painful chronic medical conditions or stable functional impairments (e.g., quadriplegia) 30, 34. Disability and functional impairment associated with chronic pain may precipitate the development of depression and suicidal thoughts. Nevertheless, pain always occurs in the present, while suicidality is most closely linked with hopelessness about the future. Hence, pain alone is unlikely to lead to suicidality, even if severe and persistent, unless it is combined with depression or catastrophizing that prompts hopelessness about the future 12. We may have not captured catastrophizing cognitions in our study that were not associated with one of the Axis I or Axis II disorders assessed.

The associations of lifetime suicidality with headaches and ‘other’ chronic pain were especially large. After adjusting for all covariates, severe or frequent headaches and ‘other’ chronic pain remained significantly associated with lifetime suicidality, suggesting that factors specific to these particular pain conditions, beyond socio-demographic factors and comorbid mood and anxiety disorders, confer risk for suicidal ideation. Potential factors linking pain with suicidality that have been cited in prior studies include sleep disturbance, pain interference with daily activities, and pain duration 12, 31. In our study, the number of years since initial diagnosis for each of the pain conditions did not differ significantly by lifetime suicidal ideation; however, this was an imperfect estimate of duration of pain experienced, since time between onset and diagnosis may vary by condition. Adding WHO-DAS scores or the presence of severe physical discomfort as model covariates did not significantly change our results; however neither of the aforementioned measures is specific to pain, and thus does not adequately capture pain severity or interference. The group with ‘other’ chronic pain clearly carried the heaviest burden of medical and psychiatric conditions, with the greatest associated distress and disability. This group tended to have multiple medical conditions, including several pain conditions. It was not possible to determine from the available data which specific pain conditions were experienced by those endorsing ‘other’ chronic pain in this study. The ‘other’ chronic pain group likely represents a diverse set of conditions not tracked by NCS-R (e.g., fibromyalgia, neuropathic pain, abdominal pain, sickle cell anemia), that may have unique associations with suicide.

Over half of the respondents (53.6%, weighted) to this survey endorsed a lifetime pain condition, and most of these endorsed a pain condition in the prior 12 months as well. This is consistent with data from another population based survey, Healthcare for Communities 4, but higher than the 5.5%–33.0% of primary care patients endorsing pain persisting for at least six months associated with disability or use of health care in the World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Psychological Problems in General Health Care 15. The lack of a marker for pain severity and specific information on pain duration likely resulted in a pain group in this study that is over-inclusive, and thus introduces a conservative bias to the risk estimates. In addition, the high false positive rate of the personality screener we used also likely introduces a conservative bias to risk estimates. Twenty-three percent of the population screened positive for borderline or antisocial personality disorder in our study. In clinical reappraisal interviews using the full IPDE with a probability subsample of 214 NCS-R Part II respondents, however, only 2.3% met criteria for DSM-IV cluster B personality disorder 22.

Strengths of this study are its population-based study design and detailed information on DSM-IV mental health disorders and chronic medical conditions. There are several limitations to our study that should be mentioned. The data is based on retrospective self report and is thus subject to recall bias and willingness to admit suicide-related behaviors and emotional problems. The use of a self-administered format for the suicide questions (i.e., reading of potential responses), however likely improved the response rate to these questions. Prior research suggests that self-report of common chronic diseases has moderate to strong agreement with medical records 1. As noted above, we were limited in the extent to which we could assess pain duration, pain severity, and number/types of pain conditions captured by the ‘other’ chronic pain category. In addition, since the data are cross-sectional, we can not make definitive conclusions about temporal relationship between suicidality and pain (i.e., which came first). The duration and severity of medical conditions were based on self report and not on objective criteria. Finally, our assessment was limited to those with suicidal ideation and attempts but without completion.

In summary, this study demonstrates an independent association between some lifetime self-reported pain conditions and suicidal ideation, plan and attempt. The results highlight the importance of identifying and treating comorbid mental disorders common in patients with non-cancer pain conditions. They also suggest that pain conditions other than arthritis and back/neck pain have associations with suicide not explained by the measures of psychopathology used in the NCS-R. Clinicians should be alert to suicidal risk in patients with pain conditions. Longitudinal studies of pain, depression and suicidal ideation would help to establish the relative roles of potential mediators in the development of suicidality among individuals with chronic pain, and thus identify areas to target in intervention.

Acknowledgments

Neither of the authors have any company holdings that would present a conflict of interest. Dr. Braden is supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NRSA) Institutional Research Training Grant [T32 MH20021 (Katon)]. Dr. Sullivan is supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Grant 5R01DA022560-02.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Evaluation of National Health Interview Survey diagnostic reporting. Vital Health Stat 2. 1994:1–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2433–2445. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braden JB, Sullivan M. Suicidal ideation, plans and attempts among individuals with chronic pain conditions: data from the National Co-morbidity Survey Replication (abstract) J Pain. 2008;9:P70. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braden JB, Zhang L, Fan MY, Unutzer J, Edlund MJ, Sullivan MD. Mental health service use by older adults: the role of chronic pain. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:156–167. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31815a3ea9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breslau N. Migraine, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. Neurology. 1992;42:392–395. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.2.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks RT, Beard J, Steel Z. Factor structure and interpretation of the K10. Psychol Assess. 2006;18:62–70. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chioqueta AP, Stiles TC. Suicide risk in patients with somatization disorder. Crisis. 2004;25:3–7. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.25.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chwastiak LA, Von Korff M. Disability in depression and back pain: evaluation of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO DAS II) in a primary care setting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:507–514. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dersh J, Gatchel RJ, Mayer T, Polatin P, Temple OR. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with chronic disabling occupational spinal disorders. Spine. 2006;31:1156–1162. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000216441.83135.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Druss B, Pincus H. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in general medical illnesses. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1522–1526. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.10.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dworkin SF, Von Korff M, LeResche L. Multiple pains and psychiatric disturbance. An epidemiologic investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:239–244. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810150039007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards RR, Smith MT, Kudel I, Haythornthwaite J. Pain-related catastrophizing as a risk factor for suicidal ideation in chronic pain. Pain. 2006;126:272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaynes BN, West SL, Ford CA, Frame P, Klein J, Lohr KN. Screening for suicide risk in adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:822–835. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-10-200405180-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gureje O, Simon GE, Von Korff M. A cross-national study of the course of persistent pain in primary care. Pain. 2001;92:195–200. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00483-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gureje O, Von Korff M, Simon GE, Gater R. Persistent pain and well-being: a World Health Organization Study in Primary Care. JAMA. 1998;280:147–151. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Normand SL, Manderscheid RW, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:184–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Borges G, Nock M, Wang PS. Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the United States, 1990–1992 to 2001–2003. Jama. 2005;293:2487–2495. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, Demler O, Heeringa S, Hiripi E, Jin R, Pennell BE, Walters EE, Zaslavsky A, Zheng H. The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:69–92. doi: 10.1002/mpr.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): background and aims. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:60–68. doi: 10.1002/mpr.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krysinska K, Heller TS, De Leo D. Suicide and deliberate self-harm in personality disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19:95–101. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000191498.69281.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, Kessler RC. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:553–564. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loranger AW. International Personality Disorder Examination: DSM-IV and ICD-10 Interviews. Lutz, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magni G, Rigatti-Luchini S, Fracca F, Merskey H. Suicidality in chronic abdominal pain: an analysis of the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (HHANES) Pain. 1998;76:137–144. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mann JJ. A current perspective of suicide and attempted suicide. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:302–311. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-4-200202190-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ratcliffe GE, Enns MW, Belik SL, Sareen J. Chronic pain conditions and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: an epidemiologic perspective. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:204–210. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31815ca2a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sansone RA, Pole M, Dakroub H, Butler M. Childhood trauma, borderline personality symptomatology, and psychophysiological and pain disorders in adulthood. Psychosomatics. 2006;47:158–162. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sansone RA, Whitecar P, Meier BP, Murry A. The prevalence of borderline personality among primary care patients with chronic pain. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:193–197. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00148-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider B, Wetterling T, Sargk D, Schneider F, Schnabel A, Maurer K, Fritze J. Axis I disorders and personality disorders as risk factors for suicide. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256:17–27. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0593-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siddall PJ, McClelland JM, Rutkowski SB, Cousins MJ. A longitudinal study of the prevalence and characteristics of pain in the first 5 years following spinal cord injury. Pain. 2003;103:249–257. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00452-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith MT, Perlis ML, Haythornthwaite JA. Suicidal ideation in outpatients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: an exploratory study of the role of sleep onset insomnia and pain intensity. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:111–118. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200403000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stang PE, Brandenburg NA, Lane MC, Merikangas KR, Von Korff MR, Kessler RC. Mental and physical comorbid conditions and days in role among persons with arthritis. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:152–158. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000195821.25811.b4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stenager EN, Stenager E, Jensen K. Attempted suicide, depression and physical diseases: a 1-year follow-up study. Psychother Psychosom. 1994;61:65–73. doi: 10.1159/000288871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sullivan MD, LaCroix AZ, Russo JE, Walker EA. Depression and self-reported physical health in patients with coronary disease: mediating and moderating factors. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:248–256. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang NK, Crane C. Suicidality in chronic pain: a review of the prevalence, risk factors and psychological links. Psychol Med. 2006;36:575–586. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Von Korff M, Crane P, Lane M, Miglioretti DL, Simon G, Saunders K, Stang P, Brandenburg N, Kessler R. Chronic spinal pain and physical-mental comorbidity in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Pain. 2005;113:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]