Summary

The paralogous transcriptional activators, MarA, SoxS and Rob, activate a common set of promoters, the marA/soxS/rob regulon of Escherichia coli, by binding a cognate site (marbox) upstream of each promoter. The extent of activation varies from one promoter to another and is only poorly correlated with the in vitro affinity of the activator for the specific marbox. Here, we examine the dependence of promoter activation on the level of activator in vivo by manipulating the steady-state concentrations of MarA and SoxS in Lon protease mutants and measuring promoter activation using lacZ transcriptional fusions. We found that: (i) the MarA concentrations needed for half-maximal stimulation varied by at least 19-fold among the 10 promoters tested; (ii) most marboxes were not saturated when there were 24,000 molecules of MarA per cell; (iii) the correlation between MarA concentration needed for half-maximal promoter activity in vivo with marbox binding affinity in vitro was poor and (iv) the two activators differed in their promoter activation profiles. The marRAB and sodA promoters could both be saturated by MarA and SoxS in vivo. However, saturation by MarA resulted in greater marRAB and lesser sodA transcription than did saturation by SoxS implying that the two activators interact with RNAP in different ways at the different promoters. Thus, the concentration and nature of activator determines which regulon promoters are activated and the extent of their activation.

Keywords: gene regulation, AraC protein family, stress response

Introduction

Cells have to distinguish among different kinds and levels of stress and respond in an appropriate manner. An over-response may be as injurious as an under-response. The MarA, SoxS and Rob transcriptional activators of Escherichia coli are interesting in this regard since they activate a common set of about 40 promoters (referred to here as the marA/soxS/rob regulon) whose functions engender antibiotic-resistance, superoxide-resistance and organic solvent tolerance.1–3 Each activator is regulated in response to a different signal: aromatic weak acids (e. g., salicylate) increase the transcription of marA; superoxides (e. g., generated by paraquat) increase the transcription of soxS; and bile salts, decanoate and dipyridyl activate the abundant Rob protein. The up-regulation of these activators increases antibiotic efflux (acrAB, tolC), decreases outer membrane permeability (micF), increases superoxide-resistance functions (zwf, fpr, sodA), substitutes superoxide-resistant proteins for sensitive ones (acnA, fumC), enhances DNA repair (nfo) and regulates other genes whose functions are not known (e.g., inaA). The ability to fine-tune the responses of the regulon components to different magnitudes of diverse signals would appear to be very important.

Although these paralogous activators of the AraC family share substantial amino acid and structural homologies,4 they bind their cognate DNA sites (marboxes) with different affinities as measured in vitro. The consensus sequence for the marbox is degenerate and asymmetrical (AYnGCACnnWnnRYYAAAY) and there are thousands of such sites in the chromosome.5–8 However, to enable activation, the marboxes have to be configured in a specific orientation and distance relative to the −35 and −10 signals for RNA polymerase.

There is wide variation among the regulon promoters in the extent of their responses to a particular activator and a given promoter may respond very differently (discriminate) to the different activators. Both effects are only partly due to differences in activator affinities for the marboxes.5,7,9 We wished to study the affinity-independent factors for this discrimination between activators by saturating the marboxes with different activators, thus eliminating differences due to binding.

We expressed marA and soxS from a high copy-number plasmid under the control of the LacIq repressor. Since MarA and SoxS are very sensitive to degradation by Lon protease, we used Lon-deficient cells to further increase the concentration of activators. Then, we determined the relationship between IPTG concentration, intracellular concentration of MarA and the expression of ten regulon promoters. We found that the expression of different members of the regulon required markedly different concentrations of MarA to achieve half-maximal activation. This suggests that activator concentration, determined by environmental signals, is used to tune the extent of regulon response so that it is commensurate with the signal. In addition, promoter saturation by MarA was not achieved for the majority of the promoters.

Results

Quantitation of IPTG-dependent MarA synthesis

We measured the dependence of marA/soxS/rob regulon promoter activity on MarA and SoxS activator concentration in E. coli. To vary the expression of MarA and SoxS, marA and soxS were placed under the control of the lacZ promoter on a high copy-number plasmid (pUC19-derivative) in a strain carrying F' lacIq. The expression of MarA and SoxS was induced by growth to early logarithmic phase in IPTG for ~10 generations to be sure that equilibrium had been attained. Since MarA and SoxS are known to be sensitive to degradation by Lon protease, these experiments were carried out primarily in lon− clpP− strains where these activators are stable.10 We measured the steady-state promoter transcription (β-galactosidase) levels of regulon promoter::lacZ fusions and, in parallel, the concentration of MarA as a function of IPTG concentration. We were thus able to correlate promoter activity with the number of MarA molecules per cell.

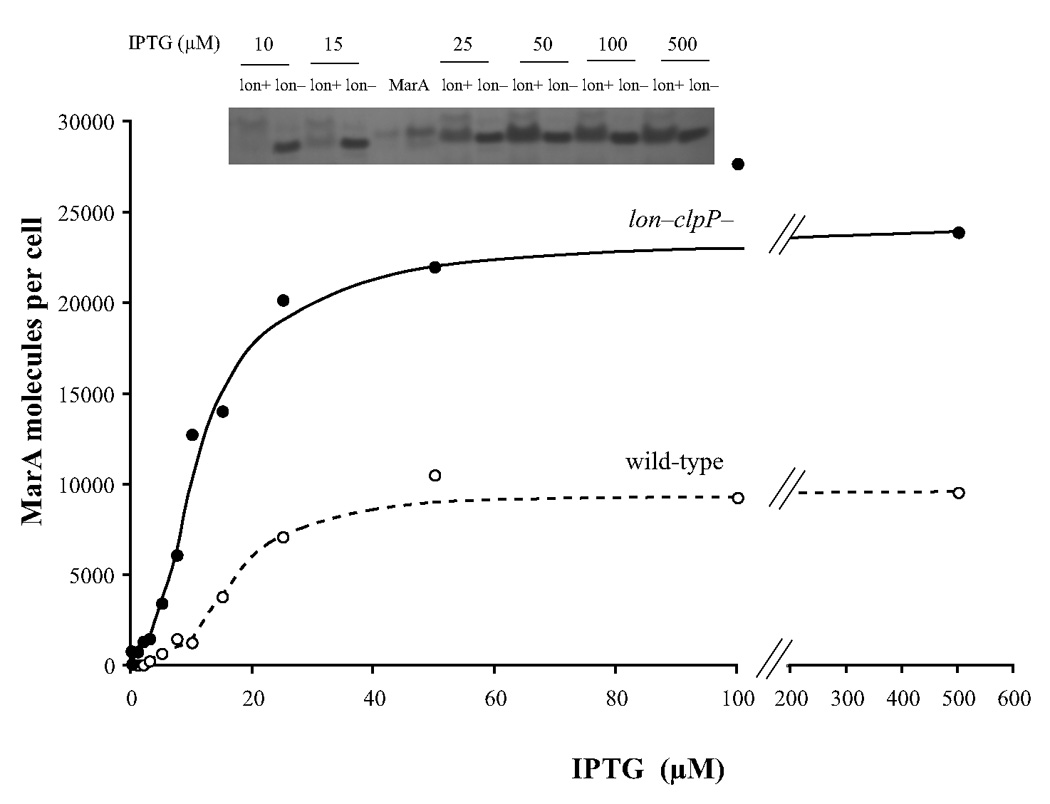

The relation between IPTG concentration and number of MarA molecules per cell is shown in Figure 1. MarA was measured using the Western blotting technique. Because of the instability of MarA, a number of different extraction techniques were tried, with and without protease inhibitors, and considerable care was taken to collect and lyse the cells rapidly. Despite these precautions, we were unable to detect MarA in the uninduced wild-type cells. The inset to Figure 1 shows a typical Western blot for cells grown in different concentrations of IPTG, with authentic MarA controls used to standardize the measurements. Data from many such gels were compiled in a graph of MarA concentration per cell against IPTG concentration for the wild-type and lon− clpP− strains (Fig. 1). The number of MarA molecules per cell increased from a number too low to estimate in the wild-type cells in the absence of IPTG to ~1,300 at 15 µM IPTG. At higher IPTG concentrations, the rate of increase began to diminish and the number of MarA molecules per cell was close to the asymptotic maximum of ~10,000 by ~50 µM IPTG. In the lon− clpP− strains where the numbers were more accurately measured, MarA increased from ~800 molecules per cell in the absence of IPTG to ~24,000 at the highest IPTG concentrations.

Figure 1.

MarA molecules per cell as a function of IPTG concentration in wild type and lon− clpP−cells. The inset is one of many Western blots from which the values in the graph were calculated. As previously noted,12 MarA made in vivo migrates slightly faster than the purified material from the plasmid construct which contains an additional 5 amino acids at its N-terminus. There is a band also present with pre-immune serum that moves slightly less rapidly than the MarA. Each lane contained the extract from 4.5*107 lon− clp− cells (M3897) or 1.4*108 wild-type cells (M3723). The two MarA lanes contained 11 (left lane) and 33 ng (right lane) of purified MarA.

It is clear that at concentrations of IPTG beyond about 15 µM, the concentration of MarA changes very little for either lon+ clpP+ or protease-deficient cells (Fig. 1). The levels of MarA in wild-type cells are clearly lower as expected but, surprisingly, not by a constant factor over the entire range. Despite the fact that MarA is reported to have a very short half-life, the relatively modest (~2.4-fold) difference seen between the concentration of MarA in wild-type and lon− clpP− cells at high concentrations of IPTG nonetheless can be accounted for on the assumption that the amount of MarA per cell exceeds the KM for the Lon protease. Indeed, modeling of the data presented and turnover data (unpublished) are consistent with a Lon protease KM for MarA of 33 µM, consistent with the KMs found for other Lon protease substrates.11

Activation of promoter transcription as a function of MarA concentration in vivo

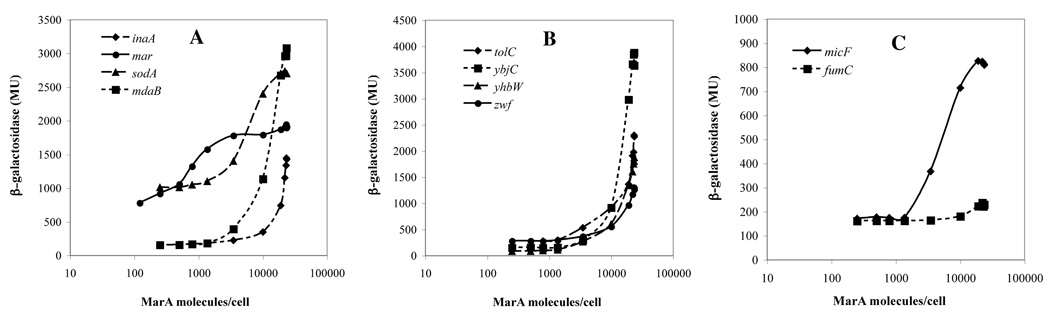

Even in Lon protease-deficient cells, the majority of regulon promoters did not achieve saturation at the highest MarA concentrations attained in vivo (24,000 molecules per cell). Of the 10 promoters studied in detail the activation profiles for only three achieved plateaus: marRAB, sodA (Fig. 2A) and micF (Fig. 2C). Two others, mdaB (Fig. 2A) and ybjC (Fig. 2B), may be near saturation but the profiles for the remaining five promoters showed no plateau.

Figure 2.

The β-galactosidase activities of 10 promoters of the marA/soxS/rob regulon as a function of the calculated number of MarA molecules in lon− clpP− cells. The promoter::lacZ fusions are indicated.

The correlation between the concentration of MarA required for half-activation of the promoter activity in vivo and values for the dissociation constants (KD) of MarA for the marbox sequences of the same promoters in vitro9,12 is poor (Table 1). marRAB and micF are among the five promoters that approach saturation of activity in vivo and their marboxes have the highest affinity for MarA in vitro. However, sodA and yjbC are also in this group yet MarA affinity for their marboxes was indetectable or weak, respectively. Thus the affinity of MarA for the marbox as measured in vitro is not the only factor that determines the concentration required for activation of regulon promoters in vivo.

Table 1.

Comparison of in vivo concentrations of MarA required for half-maximal activity of 10 regulon promoters and the in vitro dissociation constants of MarA and the 20 bp promoter marbox sequences

Differential activation by MarA and SoxS of promoters that are saturated by activator in vivo

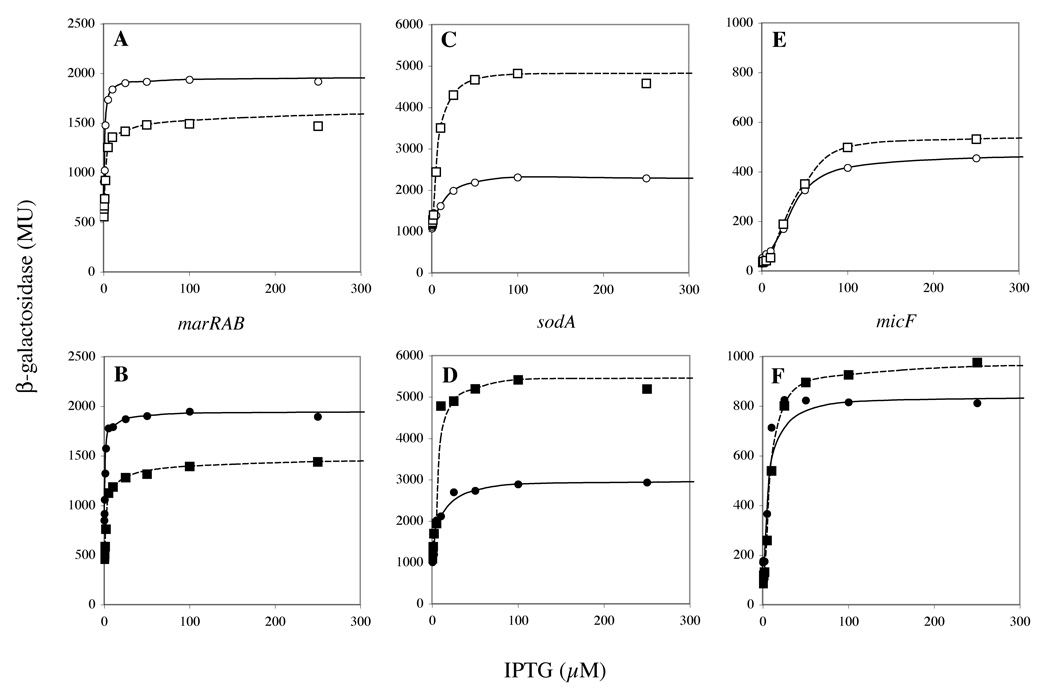

As indicated in the previous section, only marRAB, sodA and micF were fully saturated by MarA in vivo. Although we do not know the number of SoxS molecules per cell that correspond to a given concentration of IPTG used in our experiments, we argue that marRAB and sodA promoters are also saturated with SoxS. First, there was little difference between the wild-type and lon− clpP− cells in the IPTG-stimulated activation of the marRAB and sodA promoters despite the greater concentration of activators in the protease-deficient hosts (Fig. 3). This suggests that SoxS was not limiting. Second, the plateaus for these promoter activites were achieved by SoxS and MarA at low or intermediate concentrations of IPTG whereas higher concentrations were required for promoters that did not achieve saturation by MarA (data not shown). This also suggests that SoxS was not limiting.

Figure 3.

Activation of three promoters by MarA or SoxS as a function of IPTG concentration in wild-type (A, C, E) and in lon− clpP− cells (B, D, F). marRAB promoter (A, B); sodA promoter (C, D); micF promoter (E, F). Circles, MarA; squares, SoxS; open symbols, wild-type cells; closed symbols, lon− clpP− cells.

Thus, it is interesting that the profiles for MarA and SoxS were significantly different from one another relative to two of these promoters. For the marRAB promoter, the maximal activity with MarA was higher than that with SoxS (Fig. 3A and 3B). This would suggest that MarA is a better activator than SoxS. However, for the sodA promoter the maximal activity with MarA was lower than that with SoxS (Fig. 3C and 3D). Little difference was observed between the profiles for MarA and SoxS stimulation of micF (Fig. 3E and 3F). Since the differences between the behaviors of MarA and SoxS at the marRAB and sodA promoters cannot be explained by differences in binding affinity, we suggest that the interaction between activator and RNAP must be different at the different promoters.

Discussion

We have shown here that the extent to which genes of the marA/soxS/rob regulon are activated is a function of MarA concentration. Under steady-state conditions, intermediate levels of MarA fully activate some members of the regulon (e.g., marRAB, sodA) without significant activation of other members of the regulon (e.g., acnA, pqi5, Fig. 2). While we have not measured the number of molecules of SoxS per cell that were produced by IPTG-treatment, the data (Fig. 2 and unpublished) indicate that the response of the regulon to SoxS concentration is similar.

We call this phenomenon “commensurate regulon activation” because it enables E. coli to mount a proportionate response of the marA/soxS/rob regulon to a stress signal, activating the minimum number of genes necessary for overcoming a prolonged threat. When there is a low level of signal, a low level of activator is made and only a few genes are activated (e.g., micF which decreases outer membrane permeability and sodA which converts superoxides to peroxides). When the stress is greater, more activator is made and additional genes are activated (e.g., mdaB, zwf, fpr). Only at the highest stress levels are the highest activator levels made and the full panoply of genes brought into play (e.g., acrAB, tolC, pqi5). Commensurate activation therefore enables the level of threat to be matched to the cost of a response. For example, over-production of the AcrAB–TolC efflux pump, essential for the removal of multiple antibiotics and organic solvents, may also deplete the cell of energy and vital constituents. If overexpression of these genes were not costly to the cell, we would expect wild-type, unthreatened cells to have higher basal levels of MarA, SoxS and Rob and/or higher basal levels of transcription of the regulon promoters. We presume that the comparatively low levels of basal transcription for each promoter is optimal in the absence of threat. Indeed, it has been observed that overexpression of MarA and SoxS or activation of Rob can lead to severe growth inhibition.13,14

Commensurate activation is likely relevant to transcriptional regulation of systems other than the marA/soxS/rob regulon. For example, it has previously been suggested that different promoters of the CRP modulon are activated at different levels of cAMP-CRP, leading to an observed hierarchy of response to cAMP concentration15,16 although parallel measurements of promoter activity and cAMP-CRP concentration were not measured in those studies. In a further example, the response of different recA-dependent promoters to the same signal is diverse; however, in this case the diversity cannot be completely explained by differences in the way RecA acts at promoters.17

Because of the connections between the mechanisms of the steady-state phenomenon of commensurate activation and the dynamic phenomenon of temporally ordered activation,18–20 we would also expect activation of the marA regulon to exhibit temporal ordering in response to a slow rise in MarA. However, salicylate and paraquat induce a rapid rise in MarA and SoxS levels.13,21 Furthermore, because promoters of the regulon control expression of functionally diverse genes, the temporal ordering might not lead to the advantages in efficiency proposed for temporal ordering of functionally coherent regulons.18–20

We also note that the first promoter activated by either activator is marRAB itself.21 This has two consequences: 1) MarA autocatalytically increases its own synthesis, which is a rare feature among transcription factors in E. coli.22,23 Positive self-regulation is associated with multistability 24,25 but we have seen no evidence for multistability in activation of the marA regulon. It will be important to determine the functional consequences of positive autoregulation of MarA. 2) The SoxS signal is also converted into a MarA signal, tying the two responses together. Nevertheless, because of promoter discrimination, overexpression of MarA leads to greater antibiotic resistance and less superoxide resistance than does overexpression of SoxS.9 Thus, commensurate activation enables the cell to bring many different defenses into play depending on the kind of signal, its amplitude and its duration, providing a flexible defense against different levels of threat. It is also likely that in a population of cells there will be substantial heterogeneity in terms of the extent of activation of any particular regulon member and this may provide further advantages for survival.

We can use the relation between promoter activation and MarA concentration (Fig. 2) to back-calculate from the β-galactosidase activity of a cell to an equivalent concentration in MarA for any regulon promoter. Thus, our standard treatment of wild-type cells with 5 mM salicylate for 1 hr is the net equivalent of achieving a steady-state concentration of about 9,000 molecules of MarA per cell, far higher than the 750 molecules measured previously. This is likely due to a systematic error in the Western blot analyses of lon+ clpP+ strains.

We estimate that, at a minimum, there is a 19-fold variation in the amount of MarA needed for half-saturation of the different promoters. This variation is only poorly correlated with the binding affinity of MarA with these promoters in vitro (Table 1). For example, as previously reported, the marboxes of pqi-5 and acrAB bind very tightly to purified MarA but pqi-5 and acrAB require relatively high concentrations of MarA for activation. In contrast, MarA binds the sodA promoter very weakly but sodA is activated by low concentrations of MarA. This suggests that other factors present in vivo such as DNA supercoiling and/or global regulators (Fis, H-NS, etc.) may play important roles in determining promoter response to activator.

We have used the term “discrimination” for differences in activation of a single promoter by the paralogous activators and have shown a rough correlation of activation with the affinity (KD) of a particular activator for a particular marbox.9 However, at the highest activator concentrations attained here, both MarA and, as we have argued above, SoxS saturate the marRAB and sodA marboxes (Fig. 2A and 2B) so KD is not a limiting factor. Nevertheless, the marRAB promoter shows greater activity with MarA than with SoxS whereas the opposite is true for the sodA promoter. One possibility is that the two activators differ in how they interact with RNAP at different promoters and that the specific ternary complex is critical.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

All strains are derivatives of Escherichia coli K-12. Their genotypes are given in Table 2. All lon− strains were derived by P1 transduction from strain SG12079 (lonΔ510 clpP::cat), kindly provided by S. Gottesman. Transductants were selected for chloramphenicol-resistance and then screened for the mucoidy phenotype of lon− cells. Because of this selection, all of the lon− strains are also clpP::cat. Strains designated as “wild-type” are lon+ clpP+.

Table 2.

Strains used in these studies.

| Promoter fused to lacZ | strain #a | Plasmidb | Mutation | lacZ fusion from | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Reference | ||||

| fumC | M3957 | marA | lon− clpP− | N9083 | 6 |

| inaA | M3905 | marA | lon− clpP− | N9246 | 6 |

| marRAB | M2971 | none | M2971 | 28 | |

| M3687 | none | M2971 | this work | ||

| M3720 | marA | M3687 | this work | ||

| M3938 | soxS | lon− clpP− | M3687 | this work | |

| M3941 | soxS | M3687 | this work | ||

| M4161 | none | lon− clpP− | M3687 | this work | |

| M4543 | marA | lon− clpP− | M4161 | this work | |

| mdaB | M3899 | marA | lon− clpP− | M1095 | 7 |

| micF | M3944 | soxS | M9084 | 6 | |

| M3710 | marA | M9084 | 6 | ||

| M3943 | soxS | lon− clpP− | M9084 | 6 | |

| M3893 | marA | lon− clpP− | M9084 | 6 | |

| sodA | M3713 | marA | N9086 | 6 | |

| M3908 | marA | lon− clpP− | N9086 | 6 | |

| M3939 | soxS | lon− clpP− | N9086 | 6 | |

| M3940 | soxS | N9086 | 6 | ||

| tolC | M4266 | marA | M4263 | Martin, in prepartion | |

| M4267 | marA | lon− clpP− | M4263 | Martin, in prepartion | |

| M4427 | none | M4263 | Martin, in prepartion | ||

| ybjC | M3732 | marA | M1108 | 7 | |

| yhbW | M3723 | marA | M1071 | 7 | |

| M3897 | marA | lon− clpP− | M1071 | 7 | |

| zwf | M3895 | marA | lon− clpP− | N9214 | 6 |

All strains are derivatives of N8452 (ΔmarRAB rob::kan).28 All but M2971 carry F' lacIq (TetR) (from strain XL-1 Blue (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The lonΔ510 clpP::cat strains were prepared by P1 transduction, using lysates grown on strain SG12079 and selecting for CamR.

pRGM9817 is the vector, pRGM9818 carries marA and pJLR70 carries soxS. All are pUC19 derivatives (AmpR) described previously.9

β-galactosidase assays

Bacteria were grown overnight in LB (Lennox) medium at 32°C with appropriate antibiotics, diluted 1:4000 in antibiotic-free medium and grown to an A600 of 0.15 (generally 4–6 hrs) with the indicated concentrations of IPTG. β-galactosidase was measured according to Miller26 and all assays agreed to ± 5%. All assays presented were performed at least 3 times in duplicate and the standard errors of the mean were <± 10%.

Western blotting technique

Cells were grown, extracts prepared and Western blots analyzed as previously described12 using both our anti-MarA antibody and that kindly provided by Laura McMurray and Stuart Levy.27 The addition of protease inhibitors did not enhance the recovery of MarA from the wild-type cells.

Acknowledgements

We thank Laura McMurray and Stuart Levy for generously providing us with anti-MarA antibody and Susan Gottesman for strain SG12079. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH and by the U.S. Department of Energy through the LANL/LDRD Program.

References

- 1.Aono R. Improvement of organic solvent tolerance level of Escherichia coli by overexpression of stress-responsive genes. Extremophiles. 1998;2:239–248. doi: 10.1007/s007920050066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demple B. Redox signaling and gene control in the Escherichia coli soxRS oxidative stress regulon--a review. Gene. 1996;179:53–57. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White DG, Alekshun MN, McDermott PF. Frontiers in Antimicrobial Resistance. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin RG, Rosner JL. Structure and function of MarA and its homologs. In: White DG, Alekshun MN, Mcdermott PF, editors. Frontiers In Antimicrobial Resistance: A Tribute To Stuart B. Levy. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2005. pp. 235–246. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffith KL, Wolf RE., Jr Systematic mutagenesis of the DNA binding sites for SoxS in the Escherichia coli zwf and fpr promoters: identifying nucleotides required for DNA binding and transcription activation. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;40:1141–1154. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin RG, Gillette WK, Rosner JL. Structural requirements for marbox function in transcriptional activation of mar/sox/rob regulon promoters in Escherichia coli: sequence, orientation and spatial relationship to the core promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;34:431–441. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin RG, Rosner JL. Genomics of the marA/soxS/rob regulon of Escherichia coli: identification of directly activated promoters by application of molecular genetics and informatics to microarray data. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;44:1611–1624. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wood TI, Griffith KL, Fawcett WP, Jair KW, Schneider TD, Wolf RE., Jr Interdependence of the position and orientation of SoxS binding sites in the transcriptional activation of the class I subset of Escherichia coli superoxide-inducible promoters. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;34:414–430. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin RG, Gillette WK, Rosner JL. Promoter discrimination by the related transcriptional activators MarA and SoxS: differential regulation by differential binding. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;35:623–634. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffith KL, Shah IM, Wolf RE., Jr Proteolytic degradation of Escherichia coli transcription activators SoxS and MarA as the mechanism for reversing the induction of the superoxide (SoxRS) and multiple antibiotic resistance (Mar) regulons. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;51:1801–1816. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maurizi M. Degradation in vitro of bacteriophage λ N protein by Lon protease from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:2696–2703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin RG, Gillette WK, Martin NI, Rosner JL. Complex formation between activator and RNA polymerase as the basis for transcriptional activation by MarA and SoxS in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;43:355–370. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffith KL, Shah IM, Myers TE, O'Neill MC, Wolf RE., Jr Evidence for "pre-recruitment" as a new mechanism of transcription activation in Escherichia coli: the large excess of SoxS binding sites per cell relative to the number of SoxS molecules per cell. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;291:979–986. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosner JL, Dangi B, Gronenborn AM, Martin RG. Posttranscriptional activation of the transcriptional activator Rob by dipyridyl in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:1407–1416. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.5.1407-1416.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alper MD, Ames BN. Transport of antibiotics and metabolite analogs by systems under cyclic AMP control: Positive selection of Salmonella typhiumurium cya and crp mutants. J. Bacteriol. 1978;133:149–157. doi: 10.1128/jb.133.1.149-157.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Busby S, Kolb A. The CAP Modulon. In: Lin ECC, Lynch AS, editors. Regulation of Gene Expression in E. coli. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1996. pp. 255–279. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith CL. Response of recA-dependent operons to different DNA damage signals. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:10069–10074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alon U. Network motifs: theory and experimental approaches. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:450–461. doi: 10.1038/nrg2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalir S, McClure J, Pabbaraju K, Southward C, Ronen M, Leibler S, Surette MG, Alon U. Ordering genes in a flagella pathway by analysis of expression kinetics from living bacteria. Science. 2001;292:2080–2083. doi: 10.1126/science.1058758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaslaver A, Mayo AE, Rosenberg R, Bashkin P, Sberro H, Tsalyuk M, Surette MG, Alon U. Just-in-time transcription program in metabolic pathways. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:486–491. doi: 10.1038/ng1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin RG, Jair K-W, Wolf RE, Jr, Rosner JL. Autoactivation of the marRAB multiple antibiotic resistance operon by the MarA transcriptional activator in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:2216–2223. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2216-2223.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thieffry D, Huerta AM, Pérez-Rueda E, Collado-Vides J. From specific gene regulation to genomic networks: a global analysis of transcriptional regulation in Escherichia coli. Bioessays. 1998;5:433–440. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199805)20:5<433::AID-BIES10>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wall ME, Hlavacek WS, Savageau MA. Design of gene circuits: lessons from bacteria. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:34–42. doi: 10.1038/nrg1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atkinson MR, Savageau MA, Myers JT, Ninfa AJ. Development of genetic circuitry exhibiting toggle switch or oscillatory behavior in Escherichia coli. Cell. 2003;113:597–607. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00346-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savageau MA. Alternative designs for a genetic switch: analysis of switching times using the piecewise power-law representation. Math. Biosci. 2002;180:237–253. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(02)00113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller JH. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicoloff H, Perreten V, McMurry LM, Levy SB. Role for tandem duplication and Lon protease in AcrAB-TolC- dependent multiple antibiotic resistance (Mar) in an Escherichia coli mutant without mutations in marRAB or acrRAB. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:4413–4423. doi: 10.1128/JB.01502-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin RG, Rosner JL. Transcriptional and translational regulation of the marRAB multiple antibiotic resistance operon in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;53:183–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]