Abstract

The gene encoding the protease Nep secreted by the haloalkaliphilic archaeon Natrialba magadii was cloned and sequenced. Upstream of the nep gene, a region related to haloarchaeal TATA-box and BRE-like consensus sequences was identified. The nep-encoded polypeptide had a molecular mass of 56.4-kDa, a pI of 3.77 and included a 121-amino acid propeptide not present in the mature Nep. A Tat motif (GRRSVL) was also identified at residues 10 to 15 suggesting it is a substrate of the Tat pathway. The primary sequence of Nep was closely related to serine proteases of the subtilisin family from archaea and bacteria (50 to 85% similarity). The nep gene was expressed in Escherichia coli and Haloferax volcanii resulting in production of active Nep protease. In contrast to the recombinant E. coli strains in which Nep activity was only detected in cell lysate, high levels of Nep protein and activity were detected in the culture medium of stationary phase recombinant Hfx. volcanii strains. The Hfx. volcanii synthesized protease was active in high salt, high pH and high DMSO. This study provides the first molecular characterization of a halolysin-like protease from alkaliphilic haloarchaea and is the first description of a recombinant system that facilitates high-level secretion of a haloarchaeal protease.

Keywords: Natrialba magadii, Haloalkaliphilic protease, Gene cloning and expression, Solvent tolerance, Tat pathway

Introduction

Proteases are key enzymes in many processes important to the cell and are widely used in biotechnology and industry (Rao et al. 1998). Many representatives of the Archaea domain are extremophiles, thriving in conditions lethal to most cells. Thus, Archaea represent an important resource of enzymes, including proteases, for applied research as well as for basic enzymology.

Haloarchaea dominate in hypersaline environments (>2.5 M NaCl). As a result of this adaptation, haloarchaea and their enzymes are active and stable in environments of high salt (Mevarech et al. 2000). Thus, for applications which require low water activity such as high salt or organic solvents, haloarchaea and their enzymes have great potential as biocatalysts.

Extracellular proteases have been isolated and characterized at the biochemical level from a number of neutrophilic haloarchaea (optimum growth at pH 6–7) (De Castro et al. 2006; Vidyasagar et al. 2006). Genes encoding several of these proteases have been isolated and expressed in heterologous systems (Kamekura et al. 1992; Kamekura et al. 1996; Shi et al. 2006). However, the levels and activity/stability of the halophilic proteases generated from these recombinant systems are low.

In contrast to the neutrophilic haloarchaea, the alkaliphilic haloarchaea require high pH (8.5–11) and high salt (4–5 M NaCl) for growth and, thus, are considered a distinct physiological group (Tindall et al. 1984). Although there is limited information on the biology of this group, the extremophilic properties of the haloalkaliphiles for salinity and pH suggest that these microbes and their enzymes represent an underutilized resource for basic research and industrial applications.

Only a few proteases of haloalkaliphilic archaea have been purified and characterized at the biochemical level. These include an extracellular protease secreted by the haloalkaliphilic strain A2 (Yu 1991), a membrane-bound chymotrypsinogen B-like protease of Natronomonas pharaonis (Stan-Lotter et al. 1999), and extracellular proteases of Natronococcus occultus and Natrialba magadii (reviewed in De Castro et al. 2006). None of the genes encoding these enzymes has been cloned or modified for high-level expression in recombinant hosts. Of these, the Nab. magadii extracellular protease (Nep) is a 45-kDa serine protease that was purified and characterized from the extracellular medium (Giménez et al. 2000) and is active and stable in high salt, high pH and high concentrations of organic solvent (Ruiz and De Castro 2007). Nep activity is predominant in the culture medium of stationary phase Nab. magadii cells enabling its rapid and relatively simple purification (Giménez et al. 2000). Thus, Nep has many favorable properties for its application as a biocatalyst in reactions requiring high pH and/or low water activity such as protease catalyzed-peptide synthesis.

In this study, the gene encoding the Nab. magadii Nep protease was isolated, sequenced, and expressed in recombinant Escherichia coli and Hfx. volcanii. Nep-dependent proteolytic activity was detected in both systems with high-level production and secretion of an active and stable form of Nep in the Hfx. volcanii host. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the isolation of a gene which has biochemical evidence to support its encoding a halolysin-like protease from the alkaliphilic group of haloarchaea. It is also the first study to demonstrate the high-level synthesis of a haloarchaeal protease in an active and stable form in the extracellular medium of a recombinant host.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase and Taq DNA polymerase were purchased from Fermentas (Glen Burnie, MD), New England BioLabs (Ipswitch, MA), and Promega (Madison, WI). Azocasein was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and yeast extract was from Oxoid (Remel; Lenexa, KS). Plasmid DNA was isolated using WizardPlus SV Minipreps DNA purification System, and DNA fragments were purified using the WizardPlus Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega). All other chemicals and reagents were analytical grade and were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA).

Strains and culture conditions

Strains used in this study are indicated in Table 1. Cells were grown at 37 °C in liquid culture (150 rpm) or on solid medium supplemented with 1.5% (w/v) agar. E. coli was grown in Luria Bertani (LB) medium, Nab. magadii was grown in yeast extract (5 g/L) medium (Tindall et al. 1984), and Hfx. volcanii was grown in YPC medium (Dyall-Smith 2006). Medium was supplemented with 100 μg ampicillin, 50 μg kanamycin, 25 μg chloramphenicol and/or 2 μg novobiocin per ml as needed. E. coli DH5α was used for routine cloning. Hfx. volcanii DS70 was transformed with plasmid DNA isolated from an E. colidam- strain (GM33), as previously described (Cline et al. 1995).

Table 1.

Strains, plasmids and oligonucleotide primers used in this study.

| Strains and plasmids | Phenotype, genotype or oligonucleotides sequences | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial/archaeal strains | ||

| Nab. magadii ATCC43099 | ATCC | |

| Hfx. mediterranei CCM 3361 | (Rodríguez-Valera et al. 1983) | |

| Hfx. volcanii DS70 | DS2 cured of pHV2 | (Wendoloski et al. 2001) |

| E. coli DH5α | F− recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17(rk− mk+) supE44 relA1 lac [F’ ProAB lacIqZ ΔM15::Tn10(Tetr)] | NE BioLabs |

| E. coli XL-Blue | recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rk− mk−) supE44 thi-1 gyrA relA1 | Invitrogen |

| E. coli ER 1647 | F− fhuA2 (lacZ) r1 supE44 trp31 mcrA1272::Tn10(Tetr) his-1 rpsL104 (Strr)xyl-7 mtl-2 metB1 Δ(mcrC-mrr)102::Tn10(Tetr) recD1040 | Novagen |

| E. coli BM25.8 | supE44, thi D(lac–proAB) [F’ traD36, proAB +, lacIqZΔM15] limm434 (KanR)P1 (CamR) hsdR (rk12− mk12−) | Novagen |

| E. coli Rosetta (DE3) | F− ompT [Ion] hsd SB (rB mB) (an E. coli B strain) with DE3, a λ prophage carrying the T7 RNA polymerase gene | Novagen |

| E. coli GM33 | F− dam-3 sup-85 (Am) | (Marinus and Morris 1973) |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-3Z | Apr; 2743-bp expression plasmid vector | Promega |

| pET-24b (+) | Kmr; 5309-bp expression plasmid vector | Novagen |

| pET-nep | Kmr; 1623-bp coding region of nep in the NdeI-HindIII sites of pET-24b(+); nep expressed in E. coli Rosetta (DE3) | This work |

| pET-nep-His | Kmr; 1620-bp coding region of nep lacking the translation stop codon (TAA) in the NdeI-HindIII sites of pET-24b(+); nep-his6 expressed in E. coli Rosetta (DE3) | This work |

| pJAM202 | Apr, Nvr; 1,152-bp XbaI-to-DraIII fragment of pJAM621 blunt- end ligated with a 9.9-kb BamHI-to-KpnI fragment of pBAP5010; psmB-his6 expressed from Hc rRNA P2 in Hfx. volcanii | (Kaczowka et al. 2003) |

| pJAM-nep | Apr Nvr; NdeI-BlpI fragment of pET-nep cloned into pJAM202; nep expressed from Hc rRNA P2 in Hfx. volcanii DS70 | This work |

| pJAM-nep-His | Apr Nvr; NdeI-Blpl fragment of pET-nep-His cloned into pJAM202; nep-his6 expressed from Hc rRNA P2 in Hfx. volcanii DS70 | This work |

| Primersa | ||

| MI-S | 5′-CCGAACGATCCAATGTACGGCCAGTACGCTCCACAG-3′ | This work |

| MI-AS | 5′-CGCCATCGACGTGCCGGA-3′ | This work |

| NEP-S | 5′-ATGACACGTGATACCAATAGTAATGTCG-3′ | This work |

| NEP-AS | 5′-AGTTGCTGATGCCGGCGTGTC-3′ | This work |

| NEP-NdeI-F | 5′-ACGTCTTcatatgACACGTGATACCAATAG-3′ | This work |

| NEP-HindIII-stop-R | 5′-TTaagcttTTAGGAGCCCAGTTCTTCG-3′ | This work |

| NEP-HindIII-nonstop-R | 5′-TTaagcttGGAGCCCAGTTCTTCG-3′ | This work |

Restriction sites are indicated in lowercase. DNA sequence corresponding to start and stop codons of the nep gene are underlined.

Protein sequencing

Nep was purified from Nab. magadii as previously described (Giménez et al. 2000). Purified protease (670 pmol) was inhibited with 1 mM PMSF in 3 M NaCl and sequenced by Edman degradation (Edman and Begg 1967) at LANAIS-PRO facility, CONICET-UBA, Argentina.

Cloning the nep gene of Nab. magadii: generation of DNA probes and genomic libraries

Genomic DNA was extracted from Nab. magadii and Haloferax mediterranei as previously described (Ng et al. 1995). Attempts to synthesize a DNA probe by PCR using Nab. magadii genomic DNA with primers MI-S and MI-AS [corresponding to the N-terminal sequence of Nep (NH2-PNDPMYGQQYAPQR) and a subtilisin active site motif (NH2-AMSTGS), respectively] (Table 1) were unsuccessful. Considering the similarity of the N-terminal amino acid sequence of Nep with halolysins of neutrophilic haloarchaea, the Hfx. mediterranei genomic DNA was used as template for PCR-amplification of an heterologous DNA probe. Haloarchaeal codon usage frequencies (Place 1995) were included in primer design. The PCR reaction (25 μl) contained: 100 ng of genomic DNA, 200 μM each deoxynucleotide triphosphate, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 μM of each primer, 1 × PCR buffer and 2 U of Taq DNA polymerase. Reactions were incubated at: 94 °C (2 min) for 1 cycle; 94 °C (30 sec), 50 °C (30 sec) and 72 °C (30 sec) for 25 cycles; and 72 °C (2 min) for 1 cycle. The PCR-product of expected size (0.7-kb) was gel-purified, cloned in plasmid pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), sequenced, and labeled by random priming with 32P-dCTP (Sambrook et al. 1989). The labeled fragment was used to screen a PstI-subgenomic library of Nab. magadii genomic DNA in plasmid vector pGEM-3Z (Promega) by hybridization. For isolation of full-length nep, a random genomic library was prepared by ligation of 6–15 kb Sau3AI-fragments of Nab. magadii genomic DNA into λ BlueSTAR BamHI vector arms (Novagen, New Canaan CT). Ligated DNA was packaged with λ Phage Maker extract, and phages were plated onto E. coli ER 1647, following the manufacturer’s specifications (Novagen). Replica filters of the genomic library (75,000 PFU) were analyzed by hybridization with a 664-bp digoxigenin- (DIG-) labeled DNA probe generated by PCR amplification using primers Nep-S and Nep-AS (Table 1), according to manufacturer’s instructions (Boehringer Mannheim). Positive plaques were detected by CSPD-based chemiluminescence and purified. Cre-mediated plasmid excision was performed using E. coli BM 25.8. Plasmid DNA was amplified in E. coli DH5α, subjected to restriction enzyme mapping, and sequenced using the dideoxy termination method (Sanger et al. 1977) (ICBR DNA Facility, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL USA). DNA and deduced protein sequences were compared to public databases available at NCBI (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) using BLAST. Sequence alignments were performed using CLUSTAL W 1.82.

Generation of nep expression plasmids

For expression in E. coli, the nep coding region was PCR-amplified from positive plaques, cloned into plasmid pET-24b(+), and sequenced to validate fidelity of the cloned PCR product. Primers used for PCR-amplification included: Nep-NdeI-F, Nep-HindIII-stop-R, and Nep-HindIII-nonstop-R (Table 1). The E. coli expression plasmids generated included: pET-nep and pET-nep-His which respectively encode Nep and Nep with a C-terminal poly-histidine tag (Nep-His6). For Hfx. volcanii expression, the DNA fragments containing nep and nep-His were isolated from the pET-based plasmids and ligated into the shuttle plasmid vector pJAM202 using NdeI and Bpu1102I (BlpI). Each modified nep gene was positioned upstream of a T7 terminator and downstream of the Halobacterium cutirubrum (Hc) rRNA P2 promoter and Shine Dalgarno site located on pJAM202. The Hfx. volcanii expression plasmids generated included: pJAM-nep and pJAM-nep-His which respectively encode Nep and Nep-His6.

Expression of nep in recombinant E. coli and Hfx. volcanii

E. coli Rosetta (DE3) cells harboring the pET-based plasmids were grown in LB medium containing 50 μg/mlkanamycin and 35 μg/ml chloramphenicol to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.4 to 0.5. Expression of the nep geneswas induced by addition of 0.4 mM IPTG, and samples were withdrawn after 1, 3 and 5 h (37°C, 150 rpm). Hfx. volcanii DS70 cells harboring the pJAM-based plasmids were grown to stationary phase (OD600 of 1.8 to 2.5) in YPC medium supplemented with 2 μg novobiocin per ml. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g (4 °C, 10 min) and analyzed for Nep production as described below.

SDS-PAGE and protease assay of nep-expressing strains

Concentrated cell-free culture medium and cell pellets were suspended in 1 × SDS-PAGE loading buffer containing 0.1% (w/v) SDS and 0.1 M DTT, boiled for 5 min and applied to 12% (v/v) polyacrylamide gels with SDS. Molecular mass standards were BenchMark Pre-Stained Protein Ladder (Invitrogen). After electrophoresis, protein bands were visualized by Coomassie Brillant Blue staining.

Proteolytic activity of cell lysate and culture media was determined as previously described (Giménez et al. 2000). Briefly, cell pellets were suspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer at pH 8 supplemented with 3 M NaCl to a theoretical OD600 of 20, disrupted by ultrasound and clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 × g (10 min, 4 °C). When indicated, the culture medium was concentrated by gradual addition of one volume of cold absolute ethanol, incubated (1 h on ice), and centrifuged at 5,000 × g (4 °C, 10 min). The resulting precipitate was suspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8 supplemented with 3 M NaCl at 1/10 original sample volume and recentrifuged to eliminate insoluble material. Proteolytic activity of these cellular and extracellular fractions was measured at 45 °C in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer at pH 8 containing 1.5 M NaCl and 0.5% (w/v) azocasein. Reactions were stopped by addition of 1 volume of cold 10% (v/v) TCA, and acid-soluble products were detected by A335. One unit of protease activity was defined as the amount of enzyme producing an increase of 1 A335 unit per h under these assay conditions. Hfx. volcanii cells harboring pJAM-based plasmids were also grown on YPC plates containing 0.8% (w/v) non-fat skim milk and assessed for the formation of clear halos indicative of extracellular protease activity.

Salt and pH optima of the HvNep and NmNep proteases

All reactions included the substrate azocasein at 0.5% (w/v). For salt effects, the reaction mixture was buffered with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) and was supplemented with the indicated concentrations of NaCl. For pH effects, the reaction included 1.5 M NaCl and 50 mM of the following buffers: Na-phosphate (pH 7), Tris-HCl (pH 8) or glycine-NaOH (pH 10). Initial rates of hydrolysis of azocasein were calculated from time course reactions performed with 0.8 units of enzyme as measured under standard assay conditions. Cell-free culture medium supernatants of either Nab. magadii (NmNep) or Hfx. volcanii harboring pJAM-nep (HvNep) were used as a source of the Nep enzyme. All determinations were performed in duplicate.

Preparation of anti-Nep antibodies and Western blotting

The enzyme sample (preincubated with 1 mM PMSF for 30 min at room temperature) was electrophoresed on a 12% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel contaning 0.1% (w/v) SDS to separate the major protease band from other protein species resulting from autolysis. The gel was stained with Coomassie Brillant Blue R-250 and the major protein band was excised from the gel and used as antigen. This protein band was coincident with the detection of azocaseinolytic activity on a SDS-PAGE gel containing betaine loaded with the uninhibited enzyme. The gel piece was homogenized with buffer phosphate saline (12 mM phosphate buffer, 3 mM KCl and 140 mM NaCl) and the homogenate was emulsified in Freund’s complete adjuvant (Sigma) and injected subcutaneously into a rabbit. The same amount of booster injections were given every two weeks using incomplete Freund’s adjuvant. The rabbit was bled before the first injection (preimmune serum) and then one week after the last booster to obtain immune serum (anti-Nep antibodies). Western blots were performed by standard protocols using 1/4,000 anti-Nep antibody diluted in blocking buffer and 1/10,000 alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody.

Mass spectrometry

The target bands on SDS-PAGE gels were excised and subjected to in gel digestion with trypsin followed by peptide mass fingerprinting by matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) using a MALDI-TOF-TOF spectrometer, Ultraflex II (Bruker), in the Mass Spectrometry Facility CEQUIBIEM, Argentina. Spectra from all experiments were converted to DTA files and merged to facilitate database searching using the Mascot search algorithm v2.1 (Matrix Science, Boston, MA) against the non-redundant protein sequences of GenBank (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD) and the sequences of the full length and mature form of Nep deduced from the nep gene isolated in this study.

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Number

The DNA and deduced protein sequences of the Nab. magadiinep have been assigned GenBank Accession Number AY804127, Version AY804127.2 GI: 119951969, Protein ID: AAV66536.

Results and Discussion

Cloning and sequencing of the nep gene

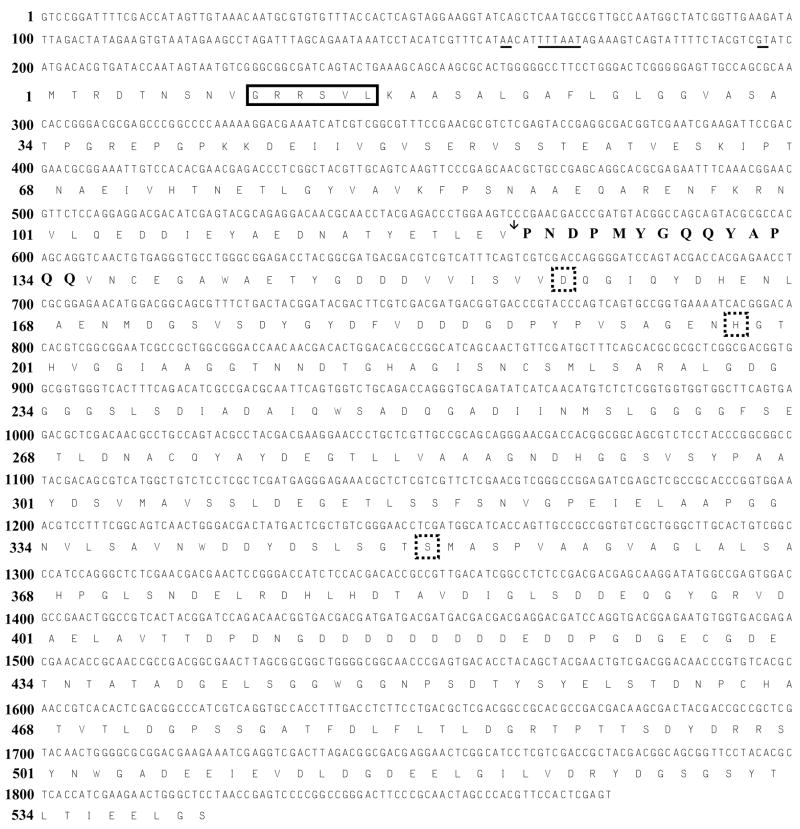

Nep was purified from the extracellular medium of Nab. magadii and sequenced by Edman degradation. The resulting N-terminal amino acid sequence of 14 residues (NH2-PNDPMYGQQYAPQQ) was used to isolate the full-length nep gene from Nab. magadii genomic DNA by hybridization (see methods for details). The putative promoter of the isolated nep gene included an archaeal TATA-box consensus sequence (5′-TTTAAT-3′; positions −34 to −29) proximal to a potential transcription start site (5′-GT- 3′, positions −5 to −4) and downstream from a BRE-like element (5′-AA-3′; positions −39 to −38) (Fig. 1). These sequences were closely related to the consensus motifs established for haloarchaeal promoters (Palmer and Daniels 1995; Reeve 2003). The 1623-bp open reading frame downstream of this promoter encoded a protein of 541 amino acid residues with an estimated molecular mass of 56,454-Da. The amino acid composition of this polypeptide showed a high percentage (20%) of acidic residues with a theoretical pI of 3.77, a feature in agreement with the acidic properties of other haloarchaeal proteins (Mevarech et al. 2000). The N-terminal sequence of purified Nep was encoded by nucleotides at position +364 to +406 relative to the putative translation start point, suggesting the polypeptide translated from nep includes a 121 amino acid residue propeptide (12,626-Da) which is cleaved to generate a mature 43,828-Da protease. This result is consistent with the 45-kDa molecular mass estimated by gel filtration for the Nep purified from Nab. magadii (Giménez et al. 2000) and suggests the native Nep is monomeric.

Fig. 1.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence of nep encoding the extracellular 45-kDa Nep serine protease of Nab. magadii. Nucleotide and amino acid residue positions are numbered on the left with the deduced amino acid sequence in single letter code below the nucleotide sequence. A putative haloarchaeal TATA-box (−34 to −29) and BRE-like element (−39 to −38), as well as a potential transcription start point (−5 to −4), are underlined. Amino acid residues 10–15, boxed with solid lines, indicate a predicted signal for the Tat secretion pathway. The cleavage site of Nep maturation is indicated with a vertical arrow. The N-terminal amino acid sequence determined from the mature Nep is indicated in bold letters. Conserved amino acid residues of the Asp-His-Ser catalytic triad active site are indicated with broken-line boxes.

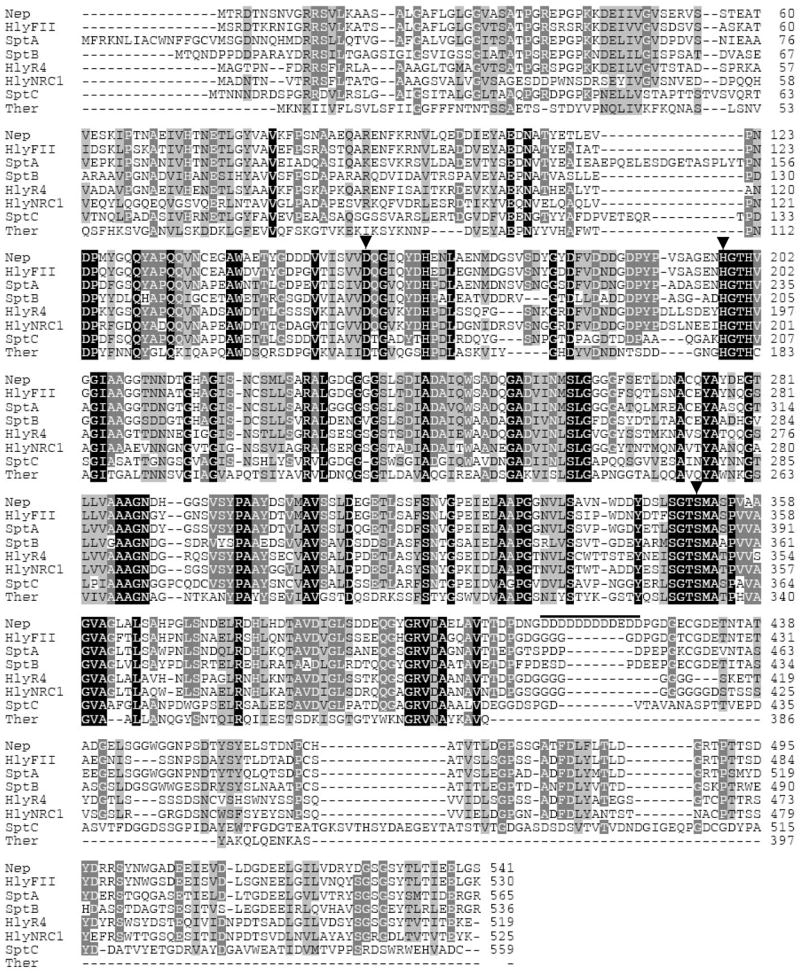

The polypeptide deduced from the complete nep gene was 62–85 % similar to halolysins characterized from neutrophilic haloarchaea (Fig. 2). These included the Natrialba asiatica halolysin, Natrinema sp J7 (previously Halobacteriumsalinarum isolateJ7) SptA protease, and Hfx. mediterranei halolysin R4 (Kamekura et al. 1992; Kamekura et al. 1996; Shi et al. 2006). Nep was also related to serine proteases of the subtilisin family from bacteria (e.g. Bacillus cereus thermitase, 50 % similarity) and uncharacterized halolysins predicted from DNA sequences including VNG2573G of Halobacterium sp. NRC-1 and SptB/SptC of Natrinema sp J7. Although neutrophilic and alkaliphilic haloarchaea belong to distinct physiological groups, these results reveal halolysin-like proteases are distributed in both groups. Halolysins, however, are not universal among the haloalkaliphilic archaea. For example, halolysin-like coding sequences are not predicted for Natronomonas pharaonis DSM 2160, the only haloalkaliphilic archaeon with a complete genome sequence available to date (Falb et al. 2005). Furthermore, Nep-cross hybridizing sequences are not detected in the genomic DNA of Ncc. occultus (not shown), which secretes a 130-kDa extracellular serine protease (Studdert et al. 2001). Thus, it remains to be determined whether halolysin-(Nep-) like proteases are common or unusual among the alkaliphilic group of haloarchaea.

Fig. 2.

Amino acid sequence alignment of the Nab. magadii Nep with other proteases of the subtilisin family. Nep: Nab. magadii serine protease, Nab. magadii (AAV66536); HlyFII: halolysin precursor, Nab. asiatica (P29143); HlyR4: halolysin R4, Hfx. mediterranei (BAA10958); HlyNRC1: deduced halolysin sequence, Halobacterium NRC-1 (NP_281139); SptA, SptB, SptC: proteases, Natrinema J7 (AAX19896, AAX19897, ABA19042); Ther: thermitase, B. cereus (NP_832079). Similarity (100 to 50%) is shown as shaded areas from black to light grey. Critical active site residues are indicated with arrowheads. The acidic patch (position 413 to 424) in Nep is indicated with a line. Genebank accession numbers are in parentheses.

Analysis of the primary sequence of Nep revealed conservation of the catalytic triad Asp, His and Ser residues critical for proteolytic activity of proteases of the subtilisin clan. In addition, a C-terminal extension, which is absent in the bacterial subtilisins, was common to all of the halolysin-like proteases including Nep (Fig. 2). Removal of this C-terminal “tail” abolishes the protease activity of Hfx. mediterranei halolysin R4 and, thus, has been proposed to be essential for the stability of halolysins in high salt (Kamekura et al. 1996). Interestingly, a highly acidic patch was identified in the C-terminal domain of the Nab. magadii Nep (positions 413 to 424) which was not conserved in the other proteases. This 12 residue stretch was a prominent and distinguishing feature of the haloalkaliphilic Nep that was not shared with any of the neutrophilic proteases and, thus, may have a role in maintaining the stability of Nep at the two extremes (high pH and/or salt).

A GRRSVL sequence (spanning residues 10 to 15) of the Nep propeptide was identified as a twin-arginine signal sequence motif by TATFIND (Rose et al. 2002) (Fig. 1). This motif (xRRShL, where h is hydrophobic and × is nucleophilic or acidic) was common to all of the haloarchaeal proteases and suggests that Nep is secreted via the Tat pathway. The Tat system is a Sec-independent protein translocation pathway with the unique ability to export folded proteins (Bolhuis 2002). Based on in silico data, haloarchaea are predicted to extensively use the Tat system as an adaptation to the high salt conditions allowing cytoplasmic folding of proteins before their secretion (Rose et al. 2002). So far only a few proteins have been confirmed experimentally to be exported by the Tat system in haloarchaea (Rose et al. 2002; Hutcheon et al. 2005; Shi et al. 2006; Giménez et al. 2007). Whether Nep is secreted via the Tat or other secretion system remains to be established; however, Nep is known to be secreted from the cell based on purification of its mature form from the extracellular matrix of Nab. magadii

Expression of nep in recombinant E. coli

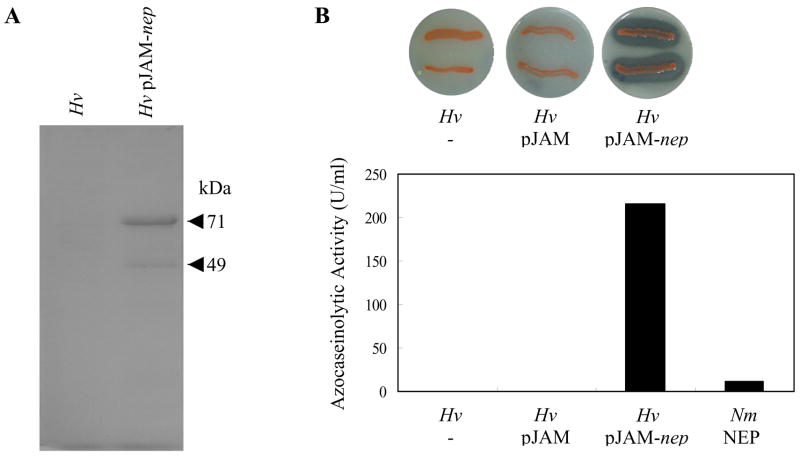

Synthesis of Nep protein was assessed in recombinant E. coli, a mesohalic bacterium. Cell lysate and culture medium of an E. coli strain expressing the nep-His gene (encoding Nep with a C-terminal His-tag) was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot using polyclonal anti-Nep antibodies. Protein bands of 85 and 70-kDa were detected by Coomassie Brillant Blue staining (Fig. 3 A) and Western blot (data not shown) in the lysate of E. coli cells after induction of nep-His expression. Similar results were observed for E. coli cells transformed with nep gene without the His tag. A major 40-kDa protein was also detected in the culture medium of induced cells (Fig. 3 A). To validate the identity of these proteins, the polypeptides were excised from the gel, subjected to trypsin digestion and analyzed by MALDI-TOF/TOF tandem mass spectrometry. Peptides corresponding to Nep were identified for the 85-kDa and 70-kDa protein bands including: the 1843.991-Da K.AASALGAFLGLGGVASATPGR.E (for both proteins) and the 1090.529-Da K.FPSNAAEQAR.E (for the 85-kDa species). Both peptides correspond to the preprosequence of the nep-encoded polypeptide indicating that these proteins were not processed. However, the 70-kDa species may be a partially degraded product of the larger form of Nep. The molecular masses of the Nep proteins expressed in recombinant E. coli are most likely overestimated (85 and 70-kDa vs 56-kDa for the polypeptide translated from nep gene) due to the abnormal electrophoretic mobility of acidic proteins in SDS-PAGE gels (Hou et al. 2000).

Fig. 3.

Expression of nep in recombinant E. coli. A. SDS-PAGE of the cell lysate (C) and ethanol precipitated cell-free culture medium (M) of E. coli cells harboring pET-nep-His after 0, 1 and 3 h of induction with IPTG. Protein bands were visualized by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. Arrowheads indicate the relative molecular masses of the induced proteins (85-, 70- and 40-kDa). B. Proteolytic activity of the cell lysate of E. coli harboring control plasmid pET24b(+) or pET-nep-His after 1 and 3 h induction with IPTG (empty and filled bars, respectively). The results are representative of at least two independent experiments.

On the other hand, the 40-kDa polypeptide was not specific to Nep and was identified as the E. coli OmpF porin, chain A. This protein may have leaked through the membrane and accumulated in the culture medium of the recombinant E. coli cells, as has been shown for other proteins expressed in E. coli (Georgiu and Segatori 2005).

To assess whether the Nep-specific proteins produced in E. coli were active, the proteolytic activity of cell lysate and culture medium was measured using azocasein as a substrate (Fig. 3 B). Of the various E. coli samples examined, significant hydrolysis of azocasein was detected only in the lysate of cells induced for expression of nep-His (Fig. 3 B) or nep genes (data not shown). In contrast, limited to no protease activity was detected in lysate of control cells (Fig. 3 B) or in the culture medium of induced or control cells (data not shown). These results indicate that even though some proteolytic activity was detected that was associated with E. coli cells”, Nep was not efficiently translocated, processed and/or folded in the bacterial host.

As no protein species corresponding to the mature Nep was evident in SDS-PAGE gels, the proteolytic activity may be attributed to undetectable amounts of active mature enzyme produced in recombinant E. coli cells and/or partially active unprocessed forms of the recombinant Nep, as it was reported for the subtilisin-like protease from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakaraensis (Kannan et al. 2001). The low activity of Nep observed in the mesohalic E. coli host is not surprising considering that Nep is an extracellular enzyme from a haloalkaliphile and is likely to require processing during or after secretion to attain full activity based on N-terminal sequencing. Interestingly, Nepappeared toxic to E. coli. When un-induced, cells harboring either nep or nep-His exhibited identical doubling times to control strains (29 to 35 min). However, after addition of IPTG to induce gene expression, both strains arrested growth. Although so far our attempts to express nep at high levels in E. coli have not been successful, further optimization may be possible as several halophilic enzymes have been produced in active forms in recombinant E. coli (Feng et al. 2006; Diaz et al. 2006; Kaczowka and Maupin-Furlow 2003).

Synthesis of active Nep enzyme in recombinant Hfx. volcanii

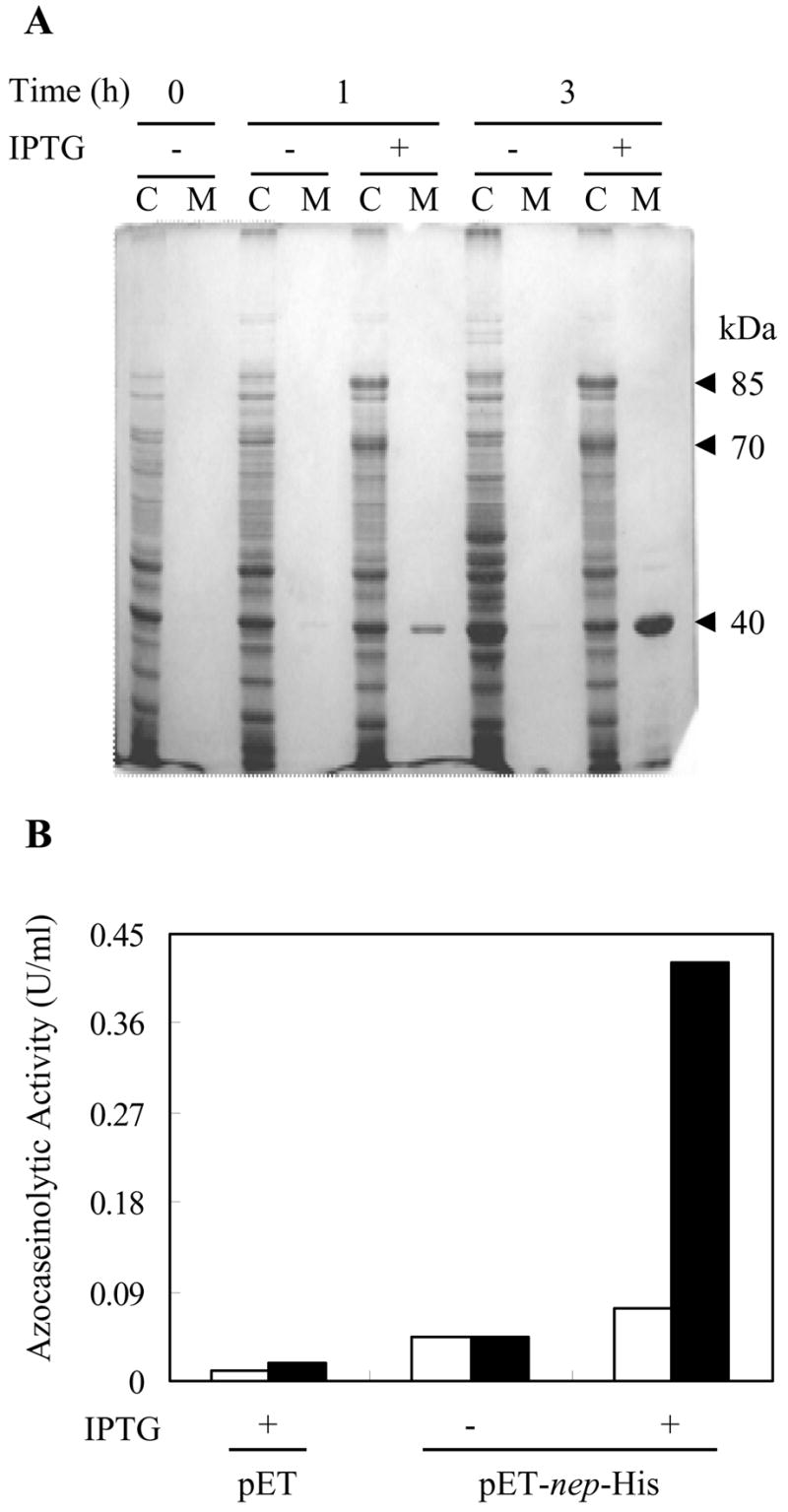

In addition to E. coli, expression of nep was evaluated in the neutrophilic haloarchaeon Hfx. volcanii. The nep coding region was positioned downstream of the strong H. cutirubrum rRNA P2 promoter in an E. coli-Hfx. volcanii shuttle vector (pJAM202) (Table 1). The resulting plasmids, pJAM-nep and pJAM-nep-His which respectively encode Nep with and without a C-terminal polyhistidine tag, were transformed into Hfx. volcanii DS70. Production of Nep in these strains was assessed by SDS-PAGE, Western blot and proteolytic activity assay, as above. SDS-PAGE of the culture medium of stationary phase cells revealed a major protein band of 71-kDa and a minor band of lower molecular mass (49-kDa) which were specific to Hfx. volcanii strains harboring plasmid pJAM-nep (Fig. 4 A). The major band of 71-kDa was subjected to MALDI-TOF-TOF tandem mass spectrometry analysis and a peptide (R.SYNWGADEEIEVDLDGDEELGILVDR.Y ) with a molecular mass of 2951.363 Da was identified to correspond to the C-terminal domain of Nep. This result confirms the identity of this protein and also shows that, similarly to the halolysins produced by neutrophilic haloarchaea, the C-terminal domain of Nep is not cleaved after secretion of the protease into the extracellular medium. Consistent with SDS-PAGE, only Hfx. volcanii cells which harbored pJAM-nep produced detectable levels of this active extracellular protease, as assessed by the appearance of clear halos on plates containing skim milk (Fig. 4 B, upper) and protease activity assay of the culture medium of stationary phase cells (Fig. 4 B, lower). These results suggest that the major protein species (apparent molecular mass of 71-kDa) most likely represents the mature active Nep. The protease activity secreted by recombinant Hfx. volcanii cells was completely inhibited by the serine protease inhibitor PMSF as expected for Nep. Surprisingly, the proteolytic activity of the extracellular fraction of the recombinant Hfx. volcanii (pJAM-nep) was ~ 100-fold higher (215 U/ml) than that of Nab. magadii (2–3 U/ml) (Fig. 4 B) and full activity was retained at 4 °C in the presence of 2.5 M NaCl for at least 7 months. These results clearly demonstrate the generation of a recombinant Hfx. volcanii strain that secretes high levels of Nep in a proteolytically active and highly-stable form. This differs dramatically from the halolysin-like proteases R4, 172 P1 and SptA of the neutrophilic haloarchaea Hfx. mediterranei, Natrialba asiatica (formely strain 172P1)and Natrinema sp. J7, respectively, which were expressed at only low levels in recombinant Hfx. volcanii (Kamekura et al. 1992; Shi et al. 2006).

Fig. 4.

Expression of nep in recombinant Hfx. volcanii. A. SDS-PAGE of the extracellular fraction of Hfx. volcanii cells transformed with or without plasmid pJAM-nep. Cell-free culture medium (10 μl) was concentrated and desalted by precipitation with 20% (v/v) TCA and washed with acetone. Protein bands were visualized by Colloidal Coomassie Blue staining (www.biochem.uwo.ca/wits/bmsl/polyacrylamide_gel_staining.html). Arrowheads indicate the relative molecular masses of the induced proteins (71- and 49-kDa). B. Protease activity of Hfx. volcanii cells harboring pJAM-nep was detected by the generation of clear halos on casein containing plates (upper panel) and by assay of stationary phase culture supernatants using azocasein as a substrate (lower panel). Hv:Hfx. volcanii DS70; HvpJAM: Hfx. volcanii DS70 harboringpJAM202; HvpJAM-nep: Hfx. volcanii DS70 harboringpJAM- nep; NmNep: Nep produced by Nab. magadii cells. The results are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Effect of salt, pH and DMSO on the activity and stability of HvNep

To facilitate purification, the recombinant Nep proteases were expressed with a His tag in Hfx. volcanii and E. coli (see Methods). However, enrichment of the His-tagged Nep proteases from the culture medium of both cells was unsuccessful, most likely due to incorrect folding of the poly-His tag. As Nep was highly enriched in the culture medium of stationary phase Hfx. volcanii (pJAM-nep) cells with few contaminating proteins based on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4), the biochemical properties of this fraction (HvNep) were compared to Nep purified from Nab. magadii (NmNep) (Giménez et al. 2000). Both Nep fractions had similar optima for protease activity at 1.5 M NaCl and pH 10. However, the HvNep showed lower activity at pH 7–8 compared to NmNep.

Previous work revealed that DMSO can substitute for salt to maintain the stability of NmNep (Ruiz and De Castro 2007). To further investigate these findings, HvNep and NmNep were incubated at 30 °C in aqueous-organic solvent buffers containing 1.5 or 0.5 M NaCl supplemented with 0 to 30% (v/v) DMSO. After 24 h, residual proteolytic activities were measured under standard (low solvent, high salt) conditions. As shown in Table 2, no activity was detected for HvNep and NmNep after preincubation in 0.5 M NaCl alone at 30 °C for 24 h. However, both proteases retained 45% of their residual activities at this ‘low’ salt concentration in the presence of 30% (v/v) DMSO, indicating that they were similarly stabilized by DMSO. Although DMSO had a similar stabilizing influence on both Nep preparations, the activity of HvNep was more sensitive to assay in the presence of organic solvents than NmNep. The proteolytic activity of HvNep was reduced by 81.3% ± 4.7 when assayed in the presence of 1.5 M NaCl and 30% (v/v) DMSO compared to 1.5 M NaCl alone. In contrast, the proteolytic activity of NmNep was reduced by only 51.7% ± 10 under similar assay conditions (data not shown).

Table 2.

Effect of DMSO on HvNEP stability.

| Residual Activity (%)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NmNEP | HvNEP | |||

| 1.5 M NaCl | 0.5 M NaCl | 1.5 M NaCl | 0.5 M NaCl | |

| DMSO (%, v/v) | ||||

| 0 | 64 | 0 | 79 | 0 |

| 15 | 97 | 2 | 99 | 5 |

| 30 | 85 | 44 | 100 | 45 |

Cell-free culture medium supernatants of either N. magadii (NmNep) or H. volcanii harboring pJAM-nep (HvNep) containing 0.8 Units of enzyme were used to perform the stability assays. NmNEP and HvNEP were preincubated in the absence or presence of 15% and 30% (v/v) DMSO and 1.5 or 0.5 M NaCl at 30 °C for 24 h. The residual activities were measured at 45 °C under the standard assay conditions (final solvent concentration below 6%, v/v) and expressed as the product accumulated in 1 h of reaction. Stability was considered as the percentage of residual activity relative to the samples without preincubation (100%). All determinations were performed in duplicate.

Overall, the Nep enzymes synthesized in recombinant Hfx. volcanii and native Nab. magadii (HvNep and NmNep) revealed similar salt and pH optima for protease activity and were equally stabilized by DMSO in dilute salt solutions(Table 2). HvNep, however, was less tolerant than NmNep when assayed for activity in suboptimal conditions (e.g. altered solvent or pH). Considering that Nab. magadii is an obligate haloalkaliphile, it is possible that the folding of Nep protease differs somewhat when synthesized in the neutrophilic host Hfx. volcanii compared to the alkaliphilic Nab. magadii. Alkaline-dependent folding may be necessary for full Nep activity and/or stability under all conditions examined.

This study provides the first molecular characterization of a halolysin-like protease from alkaliphilic haloarchaea and is the first description of a recombinant system that facilitates high-level secretion of a haloarchaeal protease.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Pohlschröder, at the University of Pennsylvania, for analysis of the Nep propeptide using TATFIND. R. E. De Castro was supported by a short-term travel grant for senior researchers from the Fulbright Commission (Argentina) to perform part of this work in the U.S. with J. A. Maupin-Furlow. D. M. Ruiz is a graduate student supported by a fellowship from CONICET (Argentina). This work was also supported in part by research grants from ANPCyT (PICT 15-25456), CONICET (PIP-6522), UNMDP (Argentina) awarded to De Castro and grants from NIH (R01 GM057498) and DOE (DE-FG02-05ER15650) awarded to Maupin-Furlow.

Non-standard abbreviations

- Nep

Natrialba magadii extracellular protease

- Tat

Twin-arginine translocation pathway

- NmNep

Natrialba magadii Nep

- HvNep

Haloferax volcanii Nep

- MALDI-TOF

matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- PMSF

Phenylmethylsulphonyl Fluoride

- BRE

Transcription factor B recognition element

References

- Bolhuis A. Protein transport in the halophilic archaeon Halobacterium sp NRC-1: a major role for the twin-arginine translocation pathway? Microbiology. 2002;148:3335–3346. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-11-3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline SW, Pfeifer F, Doolittle WF. Transformation of halophilic Archaea. In: DasSarma S, Fleischmann EM, editors. Archaea, A Laboratory Manual Halophiles. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York: 1995. pp. 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- De Castro RE, Maupin-Furlow JA, Giménez MI, Herrera Seitz MK, Sánchez JJ. Haloarchaeal proteases and proteolytic systems. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2006;30:17–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2005.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz S, Pérez-Pomares F, Pire C, Ferrer J, Bonete MJ. Gene cloning, heterologous overexpression and optimized refolding of the NAD-glutamate dehydrogenase from Haloferax mediterranei. Extremophiles. 2006;10:105–115. doi: 10.1007/s00792-005-0478-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyall-Smith M. The Halohandbook: Protocols for Haloarchaeal Genetics. 2006:140. http://www.microbiol.unimelb.edu.au/people/dyallsmith/resources/halohandbook/index.html.

- Edman P, Begg G. A protein sequenator. Eur J Biochem. 1967;1:80–91. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-25813-2_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falb M, Pfeifer F, Palm P, Rodewald K, Hickmann V, Tittor J, Oesterhelt D. Living with two extremes: Conclusions from the genome sequences of Natronomonas pharaonis. Gen Res. 2005;15:336–1343. doi: 10.1101/gr.3952905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Liu HC, Chu JF, Zhou PJ, Tang JA, Liu SJ. Genetic cloning and functional expression in Escherichia coli of an archaeorhodopsin gene from Halorubrum xinjiangense. Extremophiles. 2006;10:29–33. doi: 10.1007/s00792-005-0468-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiu G, Segatori L. Preparative expression of secreted proteins in bacteria: status report and future prospects. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2005;16:538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giménez MI, Studdert CA, Sánchez JJ, De Castro RE. Extracellular protease of Natrialba magadii: purification and biochemical characterization. Extremophiles. 2000;4:181–188. doi: 10.1007/s007920070033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giménez MI, Dilks K, Pohlschröder M. Haloferax volcanii twin-arginine translocation substates include secreted soluble, C-terminally anchored and lipoproteins. Mol Microbiol. 2007;66:1597–1606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheon GW, Vasisht N, Bolhuis A. Characterization of a highly stable α-amylase from the halophilic archaeon Haloarcula hispanica. Extremophiles. 2005;9:487–495. doi: 10.1007/s00792-005-0471-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou S, Larsen SW, Boudko D, Riley CW, Karatan E, Zimmer E, Ordal W, Alam M. Myoglobin-like aerotaxis transducers in Archaea and Bacteria. Nature. 2000;403:540–544. doi: 10.1038/35000570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan Y, Koga Y, Inou Y, Hakuri M, Takagi M, Imanaka T, Morikawa M, Kanaya S. Active subtilisin-like protease from a hyperthermophilic archaeon in a form with a putative prosequence. Appl Environm Microbiol. 2001;67:2445–2452. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.6.2445-2452.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamekura M, Seno Y, Holmes ML, Dyall-Smith ML. Molecular cloning and sequencing of the gene for a halophilic alkaline serine protease (halolysin) from an unidentified halophilic archaea strain (172 P1) and expression of the gene in Haloferax volcanii. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:736–742. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.736-742.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamekura M, Seno Y, Dyall-Smith ML. Halolysin R4, a serine proteinase from the halophilic archaeon Haloferax mediterranei; gene cloning, expression and structural studies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1294:159–167. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(96)00016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczowka SJ, Maupin-Furlow JA. Subunit topology of two 20S proteasomes from Haloferax volcanii. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:165–174. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.1.165-174.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinus MG, Morris NR. Isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid methylase mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1973;114:1143–1150. doi: 10.1128/jb.114.3.1143-1150.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mevarech M, Frolow F, Gloss LM. Halophilic enzymes: proteins with a grain of salt. Biophys Chem. 2000;86:155–64. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(00)00126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng WV, Yang CF, Halladay JT, Arora P, DasSarma S. Isolation of genomic and plasmid DNAs from Halobacterium halobium. In: DasSarma S, Fleischmann EM, editors. Archaea, A Laboratory Manual Halophiles. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York: 1995. pp. 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JR, Daniels CJ. In vivo definition of an archaeal promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1844–1849. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.7.1844-1849.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Place AR. Codon usage tables for halophilic archaea. In: DasSarma S, Fleischmann EM, editors. Archaea, A Laboratory Manual Halophiles. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York: 1995. pp. 259–261. [Google Scholar]

- Rao MB, Tanksale AM, Ghatge MS, Desphande VV. Molecular and biotechnological aspects of microbial proteases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:597–635. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.597-635.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeve JN. Archaeal chromatin and transcription. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:587–598. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Valera F, Juez G, Kushner DJ. Halobacterium mediterranei sp. nov. a new carbohydrate-utilizing extreme halophile. J Syst Appl Microbiol. 1983;4:369–381. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(83)80021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose RW, Bruser T, Kissinger JC, Pohlschröder M. Adaptation of protein secretion to extremely high-salt conditions by extensive use of the twin-arginine translocation pathway. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:943–950. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz DM, De Castro RE. Effect of organic solvents on the activity and stability of an extracellular protease secreted by the haloalkaliphilic archaeon Natrialba magadii. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;34:111–115. doi: 10.1007/s10295-006-0174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. A Laboratory Manual. 2. CSH Press; New York: 1989. Molecular Cloning. [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F, Nicklen Coulson AR. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W, Tang XF, Huang Y, Gan F, Tang B, Shen P. An extracellular halophilic protease SptA from a halophilic archaeon Natrinema sp. J7: gene cloning, expression and characterization. Extremophiles. 2006;10:599–606. doi: 10.1007/s00792-006-0003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stan-Lotter H, Doppler E, Jarosh M, Radax C, Gruber C, Inatomi KI. Isolation of a chymotrypsinogen B-like enzyme from the archaeon Natronomonas pharaonis and other halobacteria. Extremophiles. 1999;3:153–161. doi: 10.1007/s007920050111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studdert CA, Herrera Seitz MK, Plasencia Gil MI, Sánchez JJ, De Castro RE. Purification and biochemical characterization of the haloalkaliphilic archaeon Natronococcus occultus extracellular serine protease. J Basic Microbiol. 2001;41:375–383. doi: 10.1002/1521-4028(200112)41:6<375::AID-JOBM375>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tindall BJ, Mills AA, Grant WD. Natronobacterium gen nov. and Natronococcus gen. nov. two genera of haloalkaliphilic archaebacteria. System Appl Microbiol. 1984;5:41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Vidyasagar M, Prakash S, Litchfield C, Sreeramulu K. Purification and characterization of a thermostable, haloalkaliphilic extracellular serine protease from the extreme halophilic archaeon Halogeometricum borinquense strain TSS101. Archaea. 2006;2:51–57. doi: 10.1155/2006/430763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendoloski D, Ferrer C, Dyall-Smith ML. A new simvastatin (mevinolin)-resistance marker from Haloarcula hispanica and a new Haloferax volcanii strain cured of plasmid pHV2. Microbiology. 2001;147:949–954. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-4-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu TX. Proteases of haloalkaliphiles. In: Horikoshi K, Grant WD, editors. Superbugs: Microorganisms in Extreme Environments. Springer-Verlag; NewYork: 1991. pp. 76–83. [Google Scholar]