SUMMARY

The cell wall of mycobacteria contains an unusual outer membrane of extremely low permeability. While Escherichia coli uses more than 60 proteins to functionalize its outer membrane, only two mycobacterial outer membrane proteins (OMPs) are known. The porin MspA of Mycobacterium smegmatis provided the proof of principle that integral mycobacterial OMPs share the β-barrel structure, the absence of hydrophobic α-helices and the presence of a signal peptide with OMPs of gram-negative bacteria. These properties were exploited in a multi-step bioinformatic approach to predict OMPs of M. tuberculosis. A secondary structure analysis was performed for 587 proteins of M. tuberculosis predicted to be exported. Scores were calculated for the β-strand content and the amphiphilicity of the β-strands. Reference OMPs of gram-negative bacteria defined threshold values for these parameters that were met by 144 proteins of unknown function of M. tuberculosis. Two of them were verified as OMPs of unknown functions by a novel two-step experimental approach. Rv1698 and Rv1973 were detected only in the total membrane fraction of M. bovis BCG in Western blot experiments, while proteinase K digestion of whole cells showed the surface accessibility of these proteins. These findings established that Rv1698 and Rv1973 are indeed localized in the outer membrane and tripled the number of known OMPs of M. tuberculosis. Significantly, these results provide evidence for the usefulness of the bioinformatic approach to predict mycobacterial OMPs and indicate that M. tuberculosis likely has many OMPs with β-barrel structure. Our findings pave the way to identify the set of proteins which functionalize the outer membrane of M. tuberculosis.

Keywords: secondary structure, prediction, amphiphilicity, beta-strand, exported, inner membrane, periplasmic, secreted proteins

INTRODUCTION

The cell wall of mycobacteria is an intriguingly complex structure consisting of a great variety and a large amount of lipids1, 2. Very long chain-fatty acids, the mycolic acids, are covalently bound to the arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan co-polymer and were proposed to form the inner layer of an asymmetric outer membrane while other lipids constitute the outer leaflet3. X-ray diffraction studies showed that the mycolic acids are indeed oriented in parallel and perpendicular to the plane of the cell envelope4. The presence of a second lipid bilayer outside of the cytoplasmic membrane in mycobacterial species has recently been visualized for the first time in a near native state by cryo-electron microscopy5. The discovery and the analysis of the porin MspA of Mycobacterium smegmatis provided the first conclusive evidence that functionally similar, but structurally completely different outer membrane proteins (OMPs) exist also in mycobacteria6-9. Despite the well-documented importance of OMPs for the import of nutrients, secretion processes and host-pathogen interactions in gram-negative bacteria10, surprisingly few OMPs of mycobacteria are known. The only two well characterized examples of integral OMPs are the porin MspA of M. smegmatis and the channel-forming protein OmpA of M. tuberculosis11-14. By contrast, E. coli uses more than 60 proteins to functionalize its outer membrane15, none of which has significant sequence similarity to any M. tuberculosis protein.

Traditionally, OMPs have been discovered by isolating the cell envelope and then separating the inner from the outer membrane in sucrose gradients16-18. Due to the covalent linkages between the peptidoglycan, the arabinogalactan and the mycolic acid layer1, it is difficult to mechanically lyse mycobacterial cells19. This is usually achieved only by harsh conditions, which inadvertently leads to mixing of components of both membranes. This has hampered localization experiments and identification of M. tuberculosis OMPs so far20. Bioinformatic analysis of the genome of M. tuberculosis provides an alternative strategy, but OMPs are more difficult to identify by the amino acid sequence than inner membrane proteins, whose hydrophobic α-helices are predicted with accuracies exceeding 99%21. So far, all known OMPs are β-barrel proteins, which are characterized by a pattern of alternating hydrophobic and hydrophilic amino acids in the β-strands forming the β-barrel22. Such a pattern is recognizable in the protein sequences and has been exploited in recent years to develop programs for prediction of β-barrel proteins. For example, more than 10 previously unknown OMPs were predicted for E. coli23. Notably, a consensus method performed better than each individual prediction method for a set of 20 β-barrel OMPs whose structures are known at atomic resolution24. The success of these approaches motivated the application of one of these algorithms to predict OMPs of M. tuberculosis25. However, the usefulness of this analysis is limited for several reasons: (i) Pajon et al. did not exclude proteins with hydrophobic α-helices and therefore the list of predicted OMPs contains a large number of inner membrane proteins (IMPs). (ii) One of the two variables chosen as predictors of putative β-barrel structures was based on the prevalence of a C-terminal phenylalanine26, which is typical for OMPs of gram-negative bacteria but is not present in the two known mycobacterial OMPs MspA and OmpA6, 7, 11. (iii) Proteins with sequence homology to known cytoplasmic and periplasmic proteins or lipoproteins, which are anchored in membranes by their lipid moieties and not by a transmembrane β-barrel27, were not excluded from the list.

In this study, we have employed an algorithm entirely based on physical principles to predict OMPs of M. tuberculosis. In contrast to all other prediction methods so far, we provide a scoring system for the number and amphiphilicity of β-strands of a particular protein. By combining both parameters with biological knowledge we predicted 144 proteins as OMPs of Mtb. The subcellular localization of two of these proteins was determined by demonstrating their association with membranes and their surface accessibility to proteases. This alternative approach identified Rv1698 and Rv1973 as OMPs of M. tuberculosis and provided experimental evidence for the usefulness of the bioinformatic predictions.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Genome-wide analysis to identify putative OMPs of M. tuberculosis

A FASTA file with 3991 protein sequences for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv genome was obtained from ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/genbank/genomes/Bacteria/Mycobacterium_tuberculosis_H37Rv/[version: AL123456.2 date: 04/18/2006,28]. All sequences were scanned for sequence similarity matches against the Pfam database of protein motifs (version 20.029) using hmmpfam30, 31. To identify exported proteins of M. tuberculosis we predicted the presence of an N-terminal signal peptide using SignalP 3.032, 33. All proteins that had a Ymax score ≥ 0.51 were considered as exported proteins. These proteins were selected and the sequences corresponding to the signal peptide predicted by SignalP were removed. These shortened sequences should represent the mature proteins and were used for all further analyses. Next, the sequences were examined by TMHMM to predict transmembrane α-helices34, 35. For all proteins that did not have a hydrophobic α-helix the secondary structure was predicted from the sequence using the Jnet algorithm36 which gives the best performance among secondary structure prediction algorithms and achieves a 76.4% average accuracy on a large test set of proteins37. Predicted β-strands of a minimum of five consecutive residues were registered. Next, we computed the amphiphilicity of these β-strands. To this end, the mean hydrophobicity of one side of a β-strand Hβ(i) was calculated at position i in a sequence following Vogel and Jähnig38 as Hβ(i) = 1/5 × (h(i-4)+h(i-2)+h(i)+h(i+2)+h(i+4)), where h(i) is the hydrophobicity of the amino-acid at position i. Note that in a sequence of aminoacids from 1 to N, these values can only be computed for i = 5, ..., N - 4. The values of hydrophobicity for the amino-acids were taken from Sweet and Eisenberg39. Given the average value of hydrophobicity over a whole sequence Hβm, we counted the zero crossings of the Hβ - Hβm. We combined this measurement with the secondary structure prediction. The number of hydrophobicity crossings per residues in β-strand was defined as “amphiphilicity” of the β-strands of a protein and used as discriminating parameter. Higher values indicate the propensity to form a transmembrane β-barrel (Fig. 1). Further, the number of cysteines was counted, and the pI of the protein was computed using the piCalculator BioPerl module (http://www.bioperl.org/).

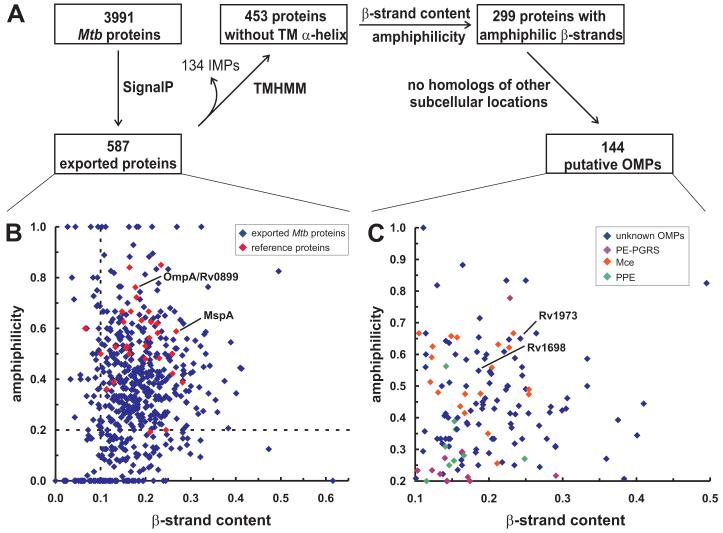

Fig. 1. Prediction of putative OMPs of M. tuberculosis H37Rv.

A. Strategy. The 3991 predicted proteins of M. tuberculosis H37Rv were analyzed for the presence of a signal peptide using the SignalP algorithm32. The 587 proteins containing a signal peptide were analyzed using the TMHMM algorithm35 to recognize hydrophobic α-helices. Their β-strand content was predicted using Jnet36. The amphiphilicity of the β-strands was computed using an algorithm from Vogel and Jähnig38.

B. β-strand content and amphiphilicity of the predicted exported proteins. The minimal length of a transmembrane β-strand was set to five amino acids. The red diamonds represent 29 known OMPs from gram-negative bacteria and from mycobacteria (MspA, OmpA/Rv0899).

C. β-strand content and amphiphilicity of 144 putative outer membrane proteins. Only exported proteins are depicted that do not have a transmembrane α-helix and have β-strand content of at least 0.09 and amphiphilicity of at least 0.19. In addition, all proteins with similarities to proteins with other subcellular localizations are not shown. Rv1698 and Rv1973 were chosen to experimentally examine their subcellular localization. The purple, orange and green diamonds represent members of the PE-PGRS, Mce and PPE families, respectively.

Analysis of the secondary structure of selected proteins

The SignalP3.0 algorithm32 was accessed at http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/ to confirm the presence of signal peptides for selected proteins of M. tuberculosis. The TMHMM program34, 35 and the ConPred II prediction server40 were used for prediction of hydrophobic transmembrane α-helices. M. tuberculosis proteins were considered not to be integral inner membrane proteins when both methods did not predict a transmembrane α-helix. All programs were used with standard settings unless otherwise noted.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155 was grown at 37°C in Middlebrook 7H9 liquid medium (Difco Laboratories) supplemented with 0.2% glycerol, 0.05% Tween 80 or on Middlebrook 7H10 agar (Difco Laboratories) supplemented with 0.2% glycerol unless indicated otherwise. For growth of Mycobacterium bovis BCG ATCC 27291 the enrichment OADC (BD Biosciences) was added to the Middlebrook 7H9 liquid medium. Escherichia coli DH5α and Escherichia coli Rosetta (Novagen) were used for cloning experiments and for overexpression of ompA, rv1698 and rv1973, respectively, and were routinely grown in LB medium at 37°C. The following antibiotics were used when required at the following concentrations: ampicillin (100 μg ml-1 for E. coli), kanamycin (30 μg ml-1 for E. coli; 10 μg ml-1 for mycobacteria), hygromycin (200 μg ml-1 for E. coli, 50 μg ml-1 for mycobacteria).

Overexpression in E. coli and preparation of recombinant Rv1698, Rv1973 and OmpA

The T7 expression system was chosen to express rv1698, rv1973 and ompA in E. coli as previously described for the porin gene mspA of M. smegmatis 41. The genes were amplified from chromosomal DNA of M. tuberculosis H37Rv by PCR using the primers as listed in Table S2. The truncated rv1698, rv1973 and ompA genes lacking the first 90, 69, and 132 nucleotides were generated from plasmids pMN335 (rv1698), pMN339 (rv1973) and pML588 (OmpA) using corresponding primers (Table S2) by PCR, respectively. These genes were cloned into the vector pET28b+ (Novagen) or its derivate under control of the T7 promoter using corresponding restriction sites (Table 3). The recombinant rv1698 and rv1973 genes encoded an N-terminal His6 tag, whereas recombinant ompA genes encoded a C-terminal His6 tag. The resulting plasmids pML122 (rv1698), pML123 (rv1973) and pML591 (ompA) were transformed into E. coli Rosetta.

For protein expression and purification, 1 L culture was grown for each recombinant strain to OD600=0.6-1.0, and induced with isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at a final concentration of 0.5 mM for 2 h at 37°C. The bacteria were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 20 ml lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, pH 8.0) and sonicated on ice using sonicator 3000 (Misonix). After sonication, DNAse (final con. 0.01mg/ml) and lysozyme (final con. 0.1mg/ml) were added, and incubated at RT for 20 min. Then, the mixture was centrifuged at 4,500xg for 15 min at 4 °C, and the pellet was resuspended in 20 ml lysis buffer, sonicated on ice, and centrifuged as above to separate inclusion bodies from cell debris. The inclusion body (pellet) was washed with 20 ml lysis buffer (without Triton X-100) three times and resuspended in 500 μl TS buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH8.0), dispersed completely by sonication, and then dissolved drop wise into 8 ml TS buffer with 8.5 M urea. One fifth of suspended inclusion bodies (100 μl) was used for each column purification, mixed gently with 500 μl equilibration buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl and 0.5% OPOE, pH8.0) and put into ultrasonication bath (FS60H, Fisher Scientific) for 15-30 min to disperse proteins completely before loading. Ni2+ charged resin column (HIS-Select™ Spin Columns, Sigma) was equilibrated with 600 μl equilibration buffer and loaded with treated sample. Unbound protein was washed out three times using 600 μl wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% OPOE, 5 mM imidazole, pH8.0). Bound proteins were eluted from the column using 500 μl elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% OPOE, 500 mM imidazole, pH8.0).

The recombinant proteins of rRv1698His and rRv1973His were purified from inclusion bodies, whereas most of the rOmpAHis protein was solubilized from lysed cells of E. coli without any detergents. The rOmpAHis protein was purified by Ni2+-affinity chromatography as described above with minor modifications. The protein concentrations were determined using bicinchoninic acid (BCA; Pierce, Rockford, USA). The purified proteins were used as positive controls in Western blot and ELISA experiments.

Generation of polyclonal antisera against putative outer membrane proteins of M. tuberculosis

To generate a polyclonal antisera against Rv1698 and Rv1973, 200 μg purified recombinant protein per rabbit was injected using TiterMax® adjuvant (TiterMax). After 28 days, serum samples were taken and checked for protein-specific antibodies in ELISA experiments. All absorptions were 40-fold increased when 1 μg purified protein was incubated with serum compared to incubation with preimmunisation serum of the same animal. The terminal bleedings were done at day 35. The antisera were obtained from Rockland Immunochemicals, Inc. The anti-OmpA antiserum was kindly provided by Dr. Philip Draper.

Expression of putative outer membrane proteins of M. tuberculosis in M. bovis BCG

The full-length rv1698, rv1973 and ompA genes were generated from chromosomal DNA M. tuberculosis H37Rv by PCR, and used to replace the mspA fragment in pMN016 using restriction sites PacI and SwaI resulting under control of the psmyc promoter (Table 1). In the resulting plasmids pMN035 (rv1698), pMN039 (rv1973) and pML003 (ompA), the psmyc promoter was exchanged by pimyc promoter, which was obtained from pMN01342, to yield the plasmids pMN335 (rv1698), pMN339 (rv1973) and pML588 (ompA) using the restriction sites PacI and PmeI. The M. bovis BCG strain was transformed with the expression vectors pMN335 (rv1698), pMN339 (rv1973) and pML588 (ompA) and carrying the M. tuberculosis genes in fusion with pimyc promoter. The vectors pMN013 (pimyc-mspA), pMN437 (psmyc-mycgfp2+) and pML970 (psmyc-phoAHA) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The M. bovis BCG strains carrying the corresponding plasmids were streaked on 7H10 agar plates, and inoculated into 7H9 liquid medium until OD600=0.8.

Table 1. Plasmids used in this work.

“Origin” means origin of replication. The annotations HygR and KanR indicate that the plasmids confer resistance to hygromycin and kanamycin, respectively

| Plasmid | Parent vector, relevant genotype and properties | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pMN013 | Pimyc-mspA; ColE1 origin; PAL5000 origin; HygR; 6000 bp | 42 |

| pMN016 | psmyc-mspA; ColE1 origin; PAL5000 origin; HygR; 6164 bp | 8 |

| pMN406 | pimyc-mycgfp2+; ColE1 origin; PAL5000 origin; HygR; 6059 bp | will be published elsewhere |

| pMN437 | psmyc-mycgfp2+; ColE1 origin; PAL5000 origin; HygR; 6236 bp | will be published elsewhere |

| pET28b+ | f1 origin, pBR322 origin, LacI; KanR; 5368 bp | Novagen |

| pMN035 | Psmyc-rv1698; ColE1 origin; PAL5000 origin; HygR; 6484 bp | this study |

| pMN039 | Psmyc-rv1973; ColE1 origin; PAL5000 origin; HygR; 6004 bp | this study |

| pMN335 | Pimyc-rv1698; ColE1 origin; PAL5000 origin; HygR; 6307 bp | this study |

| pMN339 | Pimyc-rv1973; ColE1 origin; PAL5000 origin; HygR; 5827 bp | this study |

| pML003 | Psmyc-ompA; ColE1 origin; PAL5000 origin; HygR; 6534 bp | this study |

| pML122 | PT7-hisrv1698; f1 origin, pBR322 origin, LacI; KanR; 6184 bp | this study |

| pML123 | PT7-hisrv1973; f1 origin, pBR322 origin, LacI; KanR; 5736 bp | this study |

| pML440 | pimyc-phoA; ColE1 origin; PAL5000 origin; HygR; 7707 bp | 45 |

| pML588 | Pimyc-ompA; ColE1 origin; PAL5000 origin; HygR; 6357 bp | this study |

| pML591 | PT7-ompAhis; f1 origin, pBR322 origin, LacI; KanR; 6129 bp | this study |

| pML970 | pimyc-phoAHA; ColE1 origin; PAL5000 origin; HygR; 6895 bp | this study |

Subcellular fractionation of M. bovis BCG

To separate membrane proteins from cytoplasmic proteins of M. bovis BCG we made use of an established protocol43. Each strain was grown to OD600=0.8 in 7H9 Middlebrook medium supplemented with 10% OADC, 0.2% glycerol and 0.05% Tween 80 with or without hygromycin and harvested by centrifugation. The cells were washed twice with PBS (80 mM Na2HPO4, 20 mM NaH2PO4, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.2), resuspended in PBS and lysed by sonication 5 times for 20 sec on ice with 10 sec interval and 12 Watt output power. Unbroken cells were removed by low speed centrifugation at 4,000xg. The supernatant of cell lysates was subjected to ultra-centrifugation at 100,000xg for 1 h. The resulting supernatant (SN100) was isolated and the pellet was washed 3 times with PBS (P100). The P100 pellet consists of cell envelope material including inner and outer membrane proteins. The P100 pellet was resuspended in PBS buffer containing 2% SDS and extracted at 50°C for 2 h before performing ELISA and Western blot analysis. All samples were mixed with 4 fold protein loading buffer (160 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.0, 12% SDS, 32% glycerol, 0.4% Bromophenol blue) according to 1:3 ratio (v/v for supernatant, or v/w for pellet) and boiled for 5 min before loading on the 10% SDS-PAGE gel.

Subcellular fractions of M. tuberculosis

Subcellular fractions of M. tuberculosis H37Rv such as the cell wall (CW), total membrane (MEM) and SDS-soluble cell wall proteins (SCWP), cytosol and culture filtrate were obtained from Colorado State University (CSU) as part of the NIH (NIAID) Contract HHSN266200400091C entitled “Tuberculosis Vaccine Testing and Research Materials”. The protocols describing how these fractions were produced are available at http://www.cvmbs.colostate.edu/microbiology/tb/pdf/scf.pdf. Briefly, M. tuberculosis H37Rv was grown to late-log phase (day 14) in glycerol-alanine-salts (GAS) medium, washed with PBS (pH 7.4) and inactivated by gamma-irradiation. The cells are then suspended in PBS containing 8 mM EDTA, DNase, RNase and a proteinase inhibitor cocktail (PMSF, pepstatin A, and leupeptin), and broken at 4°C. Unbroken cells are removed by low speed centrifugation (3,000xg). The cell wall including the outer membrane is first isolated by 27,000xg centrifugation for 45 min. The cell wall pellet is collected (CW), suspended and dialyzed in 0.01M ammonium bicarbonate, and extracted at 50°C with 2% SDS for 2h to yield the SDS-soluble cell wall proteins (SCWP). The supernatant of the 27,000xg centrifugation consisting of soluble proteins and inner membrane is further separated by centrifugation at 100,000xg for four hours. The proteins in the 100,000xg supernatant consist mainly of water-soluble cytoplasmic and periplasmic proteins (cytosol), while the pellet primarily contains membrane proteins (MEM). The culture supernatant is harvested from the live cells by passing through a 0.2 micron filter. The culture filtrate (CFP) is concentrated by Amicon ultrafiltration using a membrane with a molecular weight cutoff of 5,000 Da.

Western blot analysis

Proteins from bacterial extracts (such as the cell wall, total membrane and SDS-soluble cell wall proteins), cell lysates as obtained after sonication, supernatants and SDS-extracted pellets after ultracentrifugation of lysates, and purified proteins, were separated on a SDS-containing 10% polyacrylamide gel. The proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane using a standard protocol 44 and were detected by the rabbit antiserum against MspA (pAK #813)6, OmpA, Rv1698, Rv1973 and GFP (Sigma), respectively. Horseradish peroxidase coupled to an anti-rabbit antibody oxidized Luminol (ECL plus kit, Amersham) whose chemoluminescence was detected by EpiChemi3 Darkroom (UVP BioImaging system).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with whole cells of M. bovis BCG

To examine the accessibility of a protein on the cell surface of M. bovis BCG, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with whole cells was employed as described earlier for M. smegmatis7. Cells were grown to an OD600 of about 0.8, harvested by centrifugation, washed twice in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 80 and resuspended in 50 mM NaHCO3 (pH 9.6) to yield a cell concentration of about 109 cells/ml. Aliquots of 100 μl of cell suspension or dilutions thereof were transferred into wells of microtiter plates (NUNC-Immuno™ MaxiSorp™ Surface, Nalge Nunc International). At the same time, lysed cells as obtained after sonication, supernatants and SDS-extracted pellets after ultracentrifugation of lysates were also coated in the wells. After incubation overnight at 4 °C, wells were washed two times with 200 μl TBST buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.05 % Tween 80. Remaining protein binding sites were blocked with 200 μl 5 % powdered skim milk in TBST for 1 h at room temperature. Polyclonal antibodies were diluted 1:2000 and incubated with cells for 1.5 h at room temperature. The wells were washed 3 times with 200 μl TBST. Horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma) was diluted 1:10000 in TBST and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. After 4 washing steps with 200 μl TBST, 50 μl of O-phenylenediamine substrate (Sigma) was added per well. To harvest the cells after each incubation and during the washing steps, special swing-out insets were used for centrifugation (3000 rpm for 5 min). The supernatant was removed by carefully decanting the plates. All incubations were carried out at room temperature. Incubation of the sample with substrate occurred in the dark until a color change to yellow occurred. Then, the reaction was stopped by addition of 50 μl 1 M H2SO4. The plate was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min and the supernatant was transferred into a new 96-well plate for measuring absorption at 490 nm with a microplate reader (Synergy HT, Bio-TEK Instrument Inc, USA). The lysed cells, supernatants and pellets after sonication, and purified recombinant proteins were also coated on the well and treated in the same way as described above.

Protease accessibility assay

PhoA was used as a control for the protease accessibility assay. To this end, the M. smegmatis phoA gene was amplified from the vector pML440 45 by PCR using the primers phoASD_01 and phoA-HA (Table S1). The SphI digested PCR fragment was cloned into the backbone of pMN406 obtained by digestion with SphI and SwaI to yield the vector pML970 expressing a PhoAHA fusion protein under the control of the mycobacterial promoter pimyc (Table 1). To examine the surface accessibility of GFP, PhoAHA, Rv1698 and Rv1973, protease accessibility experiments were performed as described previously46 with minor modifications. M. bovis BCG strains carrying the plasmids pMN437 (psmyc-mycgfp2+), pML970 (pimyc-phoAHA), pMN335 (pimyc-rv1698), pMN339 (pimyc-rv1973) and wt M. bovis BCG were grown in 50 ml of Middlebrook 7H9/OADC medium and harvested as the cultures reached an OD600 of 4.0. The cells were washed once with TBS buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl) and then re-suspended in 1 ml of the same buffer. Two aliquots of 200 μl were taken and Proteinase K (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to one of the aliquots to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. After 30 min incubation at 37 °C the reaction was stopped by adding complete EDTA free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) from a 7-fold stock solution. The samples were immediately centrifuged, washed twice in 500 μl TBS and re-suspended in 150 μl TBS containing 1% SDS. The suspensions were kept at 40°C with shaking (850 rpm) for 30 min, and 50 μl of 4x protein loading buffer was added into each sample. All samples were boiled for 10 min, centrifuged to remove insoluble debris and 20 μl of the protein extract were separated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel and analysed by western blotting using the appropriate antibodies and standard protocols44.

RESULTS

Prediction of exported proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis

The easiest way to identify putative OMPs of M. tuberculosis would be to find homologs of OMPs known from gram-negative bacteria. However, an extensive search did not yield any homologs except for OmpA, which showed a weak similarity in the periplasmic C-terminal domain11, 47. The apparent difference of integral OMPs may reflect the different chemical environments in the outer membranes of mycobacteria and gram-negative bacteria as previously noted48. This assumption was confirmed by the crystal structure of the porin MspA of M. smegmatis9. In an alternative approach, we, therefore, followed a four-step strategy based on secondary structure analysis to identify putative OMPs of M. tuberculosis as outlined in Fig. 1A. The vast majority of bacterial OMPs have a canonical N-terminal signal sequence (positive charges, hydrophobic α-helix, signal peptidase cleavage site), which targets proteins to the Sec system for translocation across the inner membrane49. Therefore, the first step was to identify all M. tuberculosis proteins with a signal peptide using the SignalP algorithm32. This algorithm predicted 587 out of 3991 annotated proteins of M. tuberculosis H37Rv to be exported by the Sec translocase (Table S2). Notably, OmpA (Rv0899), a pore-forming OMP, which is required for growth of M. tuberculosis at low pH and for survival in mice12, was not in this list, because its N-terminus does not fit well the definitions of classical signal peptide as noted earlier11 and confirmed recently14.

Identification of inner membrane proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis

The final subcellular location of exported proteins in gram-negative bacteria depends on their physical and structural properties and could be (i) the inner membrane, (ii) the periplasm, (iii) the outer membrane or (iv) the extracellular space (medium)50. Proteins with at least one hydrophobic α-helix after cleavage of the signal peptide are assumed to be inner membrane proteins because an hydrophobic α-helix acts as a stop-transfer sequence and anchors the protein in the inner membrane of gram-negative bacteria51. Hence, the next step was to identify inner membrane proteins in the list of the 587 exported proteins of M. tuberculosis. We used the TMHMM algorithm35, which recognizes hydrophobic α-helices with near 100% reliability, to identify 134 IMPs (Table S1) within the group of 587 exported proteins of M. tuberculosis. These proteins constitute a subgroup of the 787 inner membrane proteins of M. tuberculosis as provided by the PEDANT database (http://pedant.gsf.de). It is concluded that more than 80% of all IMPs of M. tuberculosis do not appear to have a canonical signal peptide. The majority of the 134 inner membrane proteins with signal peptide showed sequence similarities to inner membrane proteins known from other bacteria. In order to identify putative OMPs we were interested in the 453 remaining proteins without certain transmembrane helix.

Prediction of outer membrane proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis

All known integral OMPs of gram-negative bacteria have a β-barrel structure with a hydrophobic surface22, 52. The β-barrel structure of MspA9 and its localization in the outer membrane of mycobacteria7 indicate that this also applies to mycobacterial OMPs. Amino acids in β-strands that are part of a membrane-spanning β-barrel have alternating hydrophilic and hydrophobic residues9, 53, 54. This pattern can be recognized in the protein sequence and has been exploited by a number of algorithms to detect OMPs in gram-negative bacteria24, 55, 56. However, this approach is only useful after exclusion of integral inner membrane proteins, which sometimes also follow such a pattern in extramembrane domains23. To test the usefulness of the Jnet algorithm36, the secondary structure of 29 known OMPs of gram-negative bacteria were predicted (Table 1). β-Barrel proteins such as OmpC and OmpF of E. coli consist entirely of β-strands as shown in the crystal structures53 and yielded β-strand scores between 0.18 and 0.28. All reference proteins with the exception of TolC have a β-strand score of at least 0.1 (Fig. 1C, Table S2). The amphiphilicity of these β-strands was calculated using an algorithm which was specifically developed for detection of OMPs38. Values close to one indicate that their β-strands show a perfect pattern of alternating hydrophilic and hydrophobic residues, whereas a value of zero means that all residues in each beta-strand are either hydrophobic of hydrophilic. Eleven of these proteins including MspA of M. smegmatis and OmpA of M. tuberculosis have an amphiphilicity score exceeding 0.5 (Fig. 1C) indicating that more than half of the amino acids in their predicted β-strands consisted of alternating hydrophilic and hydrophobic residues. The porin of Rhodobacter capsulatus57 set the lower limit with an amphiphilicity score of 0.19. Therefore, we conservatively set threshold values of 0.09 for the β-strand score and of 0.19 for the amphiphilicity for putative OMPs of M. tuberculosis. These thresholds were met by 299 out of the 453 proteins without certain transmembrane helix (Table S2). Then, the following proteins were eliminated: (i) 72 proteins annotated as lipoproteins, which are not integral membrane proteins but are anchored solely by an acyl chain into the membrane27, (ii) 74 proteins with similarities to known periplasmic and cytoplasmic proteins, and (iii) 9 secreted proteins. This reduced the number of putative OMPs to 144 (Fig. 1C, Table 2). Most of these putative OMPs (94/144) do not have any homologs of known function and are therefore annotated as unknown proteins. In addition, 19 Mce, 11 PE/PGRS and 10 PPE proteins have secondary structures similar to those of OMPs (Fig. 1C, Table 2). Nine proteins that have only one β-strand consisting of five or more residues are marked with a star in Table 2. These proteins are unlikely to form a β-barrel and to be integral OMPs.

Table 2. Putative OMPs of M. tuberculosis.

The length represents the theoretical number of amino acids of the mature protein after removal of the predicted signal peptide. The signal peptide score Ymax was taken from SignalP 3.0. All further calculations were done with the sequence of the mature protein. The number of β-strands with a length of five or more amino acids was predicted by using the Jnet algorithm. Amphiphilicity is defined as the fraction of alternating hydrophilic and hydrophobic residues in β-strands. This set of putative OMPs was obtained by applying cutoff values of >0.09 for the β-strand percentage and of >0.19 for the amphiphilicity score. Proteins with only one β-strand consisting of 5 or more residues are marked with a star. A core set of 32 putative OMPs was defined by an amphiphilicity score of >0.39 and an isoelectric point (pI) of <6.0. These proteins are highlighted in grey

| No. | Rv# | ID | GeneSymbol | Description | Length | SP score | β-strands | % β-strand | Amphiphilicity | Cysteines | pI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rv0088 | CAA98924 | none | HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 196 | 0.8 | 5 | 0.24 | 0.56 | 0 | 10.75 |

| 2 | Rv0116c | CAA17310 | none | POSSIBLE CONSERVED MEMBRANE PROTEIN | 222 | 0.8 | 7 | 0.4 | 0.34 | 1 | 7.89 |

| 3 | Rv0152c | CAE55246 | PE2 | PE FAMILY PROTEIN | 485 | 0.8 | 8 | 0.14 | 0.27 | 1 | 6.4 |

| 4 | Rv0164 | CAE55251 | TB18.5 | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN TB18.5 | 131 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.28 | 0.42 | 0 | 4.31 |

| 5 | Rv0169 | CAE55253 | mce1A | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE1A | 414 | 0.7 | 8 | 0.21 | 0.63 | 2 | 4.59 |

| 6 | Rv0170 | CAB09753 | mce1B | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE1B | 313 | 0.6 | 7 | 0.19 | 0.48 | 2 | 8.21 |

| 7 | Rv0171 | CAB09754 | mce1C | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE1C | 476 | 0.7 | 5 | 0.11 | 0.67 | 2 | 4.9 |

| 8 | Rv0172 | CAB09755 | mce1D | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE1D | 497 | 0.7 | 8 | 0.17 | 0.41 | 2 | 4.61 |

| 9 | Rv0174 | CAB09741 | mce1F | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE1F | 489 | 0.9 | 6 | 0.17 | 0.48 | 8 | 4.94 |

| 10 | Rv0225 | CAB06992 | none | POSSIBLE CONSERVED PROTEIN | 380 | 0.8 | 7 | 0.19 | 0.44 | 3 | 10.14 |

| 11 | Rv0241c | CAA17333 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 257 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0 | 10.18 |

| 12 | Rv0257* | CAE55259 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 104 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.18 | 0.3 | 3 | 8.99 |

| 13 | Rv0295c | CAA17370 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 239 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.13 | 0.82 | 1 | 5.61 |

| 14 | Rv0309 | CAB09582 | none | POSSIBLE CONSERVED EXPORTED PROTEIN | 183 | 0.9 | 4 | 0.23 | 0.32 | 3 | 8.47 |

| 15 | Rv0320 | CAB09604 | none | POSSIBLE CONSERVED EXPORTED PROTEIN PROBABLE CONSERVED MEMBRANE PROTEIN |

195 | 0.6 | 5 | 0.19 | 0.46 | 2 | 6.51 |

| 16 | Rv0403c | CAB06594 | mmpS1 | MMPS1 PROBABLE CONSERVED MEMBRANE PROTEIN |

120 | 0.8 | 4 | 0.38 | 0.21 | 2 | 6.62 |

| 17 | Rv0451c | CAA17408 | mmpS4 | MMPS4 | 112 | 0.7 | 5 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 2 | 4.75 |

| 18 | Rv0455c* | CAA17411 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN PROBABLE CONSERVED MEMBRANE PROTEIN |

117 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 2 | 6.5 |

| 19 | Rv0506 | CAB00932 | mmpS2 | MMPS2 | 123 | 0.8 | 5 | 0.33 | 0.59 | 2 | 7.51 |

| 20 | Rv0584 | CAA17455 | none | POSSIBLE CONSERVED EXPORTED PROTEIN | 844 | 0.8 | 28 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 3 | 4.76 |

| 21 | Rv0589 | CAE55301 | mce2A | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE2A | 365 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.23 | 0.62 | 2 | 4.58 |

| 22 | Rv0590 | CAB09962 | mce2B | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE2B | 240 | 0.6 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.49 | 2 | 6.72 |

| 23 | Rv0592 | CAB09960 | mce2D | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE2D | 472 | 0.8 | 5 | 0.16 | 0.65 | 2 | 4.63 |

| 24 | Rv0594 | CAB09959 | mce2F | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE2F | 478 | 0.8 | 9 | 0.2 | 0.35 | 8 | 5.24 |

| 25 | Rv0614 | CAB09971 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 287 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.14 | 0.2 | 2 | 6.95 |

| 26 | Rv0677c | CAA17460 | mmpS5 | POSSIBLE CONSERVED MEMBRANE PROTEIN MMPS5 |

108 | 0.7 | 4 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 2 | 4.11 |

| 27 | Rv0679c | CAA17462 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL THREONINE RICH PROTEIN | 122 | 0.8 | 6 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 2 | 4.06 |

| 28 | Rv0755c | CAE55320 | PPE12 | PPE FAMILY PROTEIN | 613 | 0.6 | 7 | 0.15 | 0.39 | 0 | 4.22 |

| 29 | Rv0774c | CAB02386 | none | PROBABLE CONSERVED EXPORTED PROTEIN | 273 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.1 | 0.21 | 2 | 5.97 |

| 30 | Rv0799c | CAB09574 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 304 | 0.6 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.49 | 2 | 5.18 |

| 31 | Rv0817c | CAA17623 | none | PROBABLE CONSERVED EXPORTED PROTEIN | 242 | 0.8 | 4 | 0.19 | 0.59 | 0 | 5.61 |

| 32 | Rv0875c | CAA97382 | none | POSSIBLE CONSERVED EXPORTED PROTEIN | 137 | 0.8 | 4 | 0.3 | 0.42 | 2 | 6.34 |

| 33 | Rv0878c | CAE55333 | PPE13 | PPE FAMILY PROTEIN | 407 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.1 | 0.24 | 1 | 6.25 |

| 34 | Rv0888 | CAA97395 | none | PROBABLE EXPORTED PROTEIN | 458 | 0.5 | 13 | 0.24 | 0.41 | 6 | 4.63 |

| 35 | Rv0906 | CAA97381 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 335 | 0.7 | 6 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 2 | 6.18 |

| 36 | Rv0980c | CAE55345 | PE_PGRS18 | PE/PGRS FAMILY PROTEIN | 423 | 0.7 | 13 | 0.29 | 0.22 | 1 | 4.06 |

| 37 | Rv0988 | CAA17587 | none | POSSIBLE CONSERVED EXPORTED PROTEIN | 353 | 0.8 | 7 | 0.2 | 0.55 | 0 | 4.64 |

| 38 | Rv0999 | CAB08148 | none | HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 212 | 0.7 | 8 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 4 | 6.5 |

| 39 | Rv1006 | CAB08141 | none | HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 538 | 0.9 | 8 | 0.17 | 0.58 | 4 | 4.97 |

| 40 | Rv1067c | CAE55351 | PE_PGRS19 | PE/PGRS FAMILY PROTEIN | 636 | 0.9 | 7 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0 | 5.12 |

| 41 | Rv1081c | CAA17197 | none | PROBABLE CONSERVED MEMBRANE PROTEIN | 101 | 0.6 | 6 | 0.5 | 0.83 | 2 | 8.2 |

| 42 | Rv1087 | CAE55354 | PE_PGRS21 | PE/PGRS FAMILY PROTEIN | 736 | 0.6 | 6 | 0.1 | 0.23 | 0 | 4.05 |

| 43 | Rv1091 | CAE55359 | PE_PGRS22 | PE/PGRS FAMILY PROTEIN | 822 | 0.7 | 9 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0 | 4.11 |

| 44 | Rv1135c | CAE55364 | PPE16 | PPE FAMILY PROTEIN LOW MOLECULAR WEIGHT T-CELL ANTIGEN |

589 | 0.8 | 11 | 0.14 | 0.31 | 0 | 3.96 |

| 45 | Rv1174c | CAA15851 | TB8.4 | TB8.4 | 81 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 2 | 4.37 |

| 46 | Rv1184c | CAA15861 | none | POSSIBLE EXPORTED PROTEIN | 333 | 0.6 | 5 | 0.11 | 0.56 | 0 | 4.56 |

| 47 | Rv1209 | CAB07832 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 99 | 0.7 | 2 | 0.11 | 1 | 0 | 4.84 |

| 48 | Rv1268c | CAB00911 | none | HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 199 | 0.9 | 4 | 0.21 | 0.45 | 1 | 4.17 |

| 49 | Rv1325c | CAE55377 | PE_PGRS24 | PE/PGRS FAMILY PROTEIN | 572 | 0.6 | 10 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0 | 3.96 |

| 50 | Rv1339 | CAA99972 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 248 | 0.5 | 5 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 5 | 5.41 |

| 51 | Rv1351 | CAA99984 | none | HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 79 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.24 | 0.44 | 4 | 11.66 |

| 52 | Rv1375 | CAB02636 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 422 | 0.6 | 8 | 0.18 | 0.42 | 6 | 4.78 |

| 53 | Rv1382 | CAB02643 | none | PROBABLE EXPORT OR MEMBRANE PROTEIN | 131 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.19 | 0.43 | 0 | 4.95 |

| 54 | Rv1386* | CAE55383 | PE15 | PE FAMILY PROTEIN | 70 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.23 | 0.78 | 1 | 4.38 |

| 55 | Rv1419 | CAB02167 | none | HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 123 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.2 | 0.54 | 6 | 4.08 |

| 56 | Rv1433 | CAB09251 | none | POSSIBLE CONSERVED EXPORTED PROTEIN | 250 | 0.6 | 7 | 0.28 | 0.43 | 1 | 5.05 |

| 57 | Rv1477 | CAA16005 | none | HYPOTHETICAL INVASION PROTEIN | 432 | 0.9 | 5 | 0.14 | 0.33 | 1 | 6.82 |

| 58 | Rv1478 | CAA16006 | none | HYPOTHETICAL INVASION PROTEIN | 209 | 0.7 | 4 | 0.19 | 0.45 | 1 | 9.88 |

| 59 | Rv1488 | CAB02038 | none | POSSIBLE EXPORTED CONSERVED PROTEIN | 346 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.15 | 0.33 | 0 | 6.16 |

| 60 | Rv1548c | CAE55401 | PPE21 | PPE FAMILY PROTEIN | 650 | 0.8 | 9 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0 | 4.18 |

| 61 | Rv1566c | CAB09071 | none | Possible inv protein | 201 | 0.9 | 3 | 0.17 | 0.5 | 0 | 10.38 |

| 62 | Rv1669 | CAA17609 | none | HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 93 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 3 | 8.5 |

| 63 | Rv1698 | CAB10955 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 285 | 0.7 | 6 | 0.19 | 0.55 | 0 | 4.83 |

| 64 | Rv1784 | CAA17706 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 923 | 0.6 | 14 | 0.16 | 0.29 | 7 | 5.17 |

| 65 | Rv1800 | CAE55427 | PPE28 | PPE FAMILY PROTEIN | 623 | 0.6 | 10 | 0.15 | 0.26 | 2 | 4.22 |

| 66 | Rv1803c | CAE55430 | PE_PGRS32 | PE/PGRS FAMILY PROTEIN | 606 | 0.7 | 7 | 0.14 | 0.2 | 0 | 3.73 |

| 67 | Rv1804c | CAA17725 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 85 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.24 | 0.59 | 4 | 6.76 |

| 68 | Rv1813c* | CAB09499 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 110 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.6 | 4 | 8.96 |

| 69 | Rv1815 | CAB01480 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 193 | 0.9 | 5 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 4 | 5.78 |

| 70 | Rv1890c | CAB10062 | none | HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 200 | 0.7 | 3 | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0 | 10.22 |

| 71 | Rv1906c | CAB10031 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 123 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 2 | 4.65 |

| 72 | Rv1910c | CAB10054 | none | PROBABLE EXPORTED PROTEIN | 171 | 0.8 | 2 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 2 | 6.08 |

| 73 | Rv1914c | CAB10028 | none | HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 106 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.26 | 0.67 | 1 | 10.16 |

| 74 | Rv1955 | CAB06506 | none | HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 140 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.11 | 0.67 | 0 | 11.06 |

| 75 | Rv1966 | CAE55443 | mce3A | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE3A | 376 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.12 | 0.59 | 4 | 5.13 |

| 76 | Rv1967 | CAA17840 | mce3B | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE3B | 313 | 0.6 | 7 | 0.23 | 0.67 | 2 | 9.24 |

| 77 | Rv1968 | CAA17841 | mce3C | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE3C | 383 | 0.6 | 7 | 0.15 | 0.66 | 0 | 7.74 |

| 78 | Rv1969 | CAA17842 | mce3D | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE3D | 391 | 1 | 7 | 0.16 | 0.44 | 2 | 5.02 |

| 79 | Rv1971 | CAA17844 | mce3F | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE3F | 412 | 0.8 | 4 | 0.13 | 0.48 | 4 | 4.7 |

| 80 | Rv1973 | CAA17846 | none | POSSIBLE CONSERVED MCE ASSOCIATED MEMBRANE PROTEIN | 136 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.24 | 0.65 | 0 | 6.52 |

| 81 | Rv1974 | CAA17847 | none | PROBABLE CONSERVED MEMBRANE PROTEIN | 88 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.23 | 0.65 | 2 | 8.19 |

| 82 | Rv1975 | CAA17848 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 193 | 0.8 | 4 | 0.21 | 0.43 | 2 | 4.28 |

| 83 | Rv2075c | CAA98220 | none | Possible hypothetical exported or envelope protein | 456 | 0.8 | 6 | 0.1 | 0.21 | 14 | 6.12 |

| 84 | Rv2112c | CAB10703 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 519 | 0.7 | 7 | 0.15 | 0.51 | 4 | 5.5 |

| 85 | Rv2223c | CAA94646 | none | Probable exported protease | 485 | 0.9 | 8 | 0.16 | 0.36 | 10 | 4.54 |

| 86 | Rv2224c | CAA94647 | none | Probable exported protease | 478 | 0.8 | 11 | 0.19 | 0.38 | 10 | 5 |

| 87 | Rv2232 | CAA94666.2 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 266 | 0.5 | 7 | 0.21 | 0.33 | 1 | 6.17 |

| 88 | Rv2251 | CAA17288 | none | POSSIBLE FLAVOPROTEIN | 455 | 0.6 | 10 | 0.2 | 0.29 | 10 | 6.39 |

| 89 | Rv2253 | CAA17290 | none | Possible secreted unknown protein | 138 | 1 | 4 | 0.27 | 0.38 | 4 | 5.67 |

| 90 | Rv2264c | CAA17301 | none | conserved hypothetical proline rich protein | 569 | 0.7 | 10 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 3 | 4.76 |

| 91 | Rv2307c | CAB00991 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 256 | 0.7 | 5 | 0.14 | 0.32 | 1 | 6.52 |

| 92 | Rv2353c | CAE55477 | PPE39 | PPE FAMILY PROTEIN | 322 | 0.7 | 6 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0 | 3.64 |

| 93 | Rv2356c | CAE55478 | PPE40 | PPE FAMILY PROTEIN LOW MOLECULAR WEIGHT ANTIGEN CFP2 (LOW MOLECULAR WEIGHT PROTEIN ANTIGEN 2) |

585 | 0.7 | 7 | 0.14 | 0.56 | 0 | 3.6 |

| 94 | Rv2376c | CAB08476 | cfp2 | (CFP-2) | 145 | 0.9 | 2 | 0.14 | 0.4 | 0 | 4.94 |

| 95 | Rv2396 | CAE55484 | PE_PGRS41 | PE/PGRS FAMILY PROTEIN | 327 | 0.6 | 7 | 0.17 | 0.2 | 1 | 3.89 |

| 96 | Rv2525c | CAB06183 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 204 | 0.8 | 5 | 0.22 | 0.61 | 1 | 9.42 |

| 97 | Rv2565 | CAB01050 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 556 | 0.5 | 19 | 0.22 | 0.49 | 3 | 5.34 |

| 98 | Rv2597 | CAB01278 | none | PROBABLE MEMBRANE PROTEIN | 182 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.23 | 0.37 | 1 | 4.43 |

| 99 | Rv2599 | CAB01276 | none | PROBABLE CONSERVED MEMBRANE PROTEIN | 112 | 0.9 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.83 | 2 | 9.33 |

| 100 | Rv2668 | CAB02339 | none | POSSIBLE EXPORTED ALANINE AND VALINE RICH PROTEIN | 151 | 0.8 | 4 | 0.3 | 0.43 | 1 | 4.77 |

| 101 | Rv2672 | CAB02326 | none | POSSIBLE SECRETED PROTEASE | 492 | 0.8 | 8 | 0.14 | 0.5 | 10 | 4.65 |

| 102 | Rv2741 | CAE55516 | PE_PGRS47 | PE/PGRS FAMILY PROTEIN | 494 | 0.7 | 7 | 0.16 | 0.36 | 0 | 4.32 |

| 103 | Rv2799 | CAB03647 | none | PROBABLE MEMBRANE PROTEIN | 181 | 0.7 | 4 | 0.2 | 0.33 | 4 | 5.12 |

| 104 | Rv2840c* | CAB03669 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 77 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 1 | 10.11 |

| 105 | Rv2891 | CAA98367 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 212 | 0.9 | 3 | 0.14 | 0.64 | 3 | 11.12 |

| 106 | Rv2956 | CAB05420 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 219 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.16 | 0.88 | 3 | 5.26 |

| 107 | Rv2980 | CAB05432 | none | POSSIBLE CONSERVED SECRETED PROTEIN LOW MOLECULAR WEIGHT PROTEIN ANTIGEN 6 |

148 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.18 | 0.44 | 2 | 7.25 |

| 108 | Rv3004* | CAA16089 | cfp6 | (CFP-6) | 76 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.22 | 0.83 | 0 | 11.83 |

| 109 | Rv3033 | CAA16118 | none | HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 155 | 0.9 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.53 | 4 | 4.82 |

| 110 | Rv3036c | CAA16121 | TB22.2 | PROBABLE CONSERVED SECRETED PROTEIN TB22.2 |

203 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 3 | 4.78 |

| 111 | Rv3096 | CAB08388 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 351 | 0.8 | 6 | 0.14 | 0.41 | 2 | 9.38 |

| 112 | Rv3159c | CAE55561 | PPE53 | PPE FAMILY PROTEIN | 554 | 0.8 | 13 | 0.17 | 0.28 | 0 | 3.93 |

| 113 | Rv3196 | CAA16661 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 271 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.11 | 0.29 | 5 | 10.54 |

| 114 | Rv3209 | CAB08307 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL THREONIN AND PROLINE RICH PROTEIN | 142 | 0.6 | 6 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 2 | 9.78 |

| 115 | Rv3212 | CAB08304 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL ALANINE VALINE RICH PROTEIN | 369 | 0.6 | 14 | 0.31 | 0.46 | 4 | 8.28 |

| 116 | Rv3224A* | CAE55570 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 40 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.23 | 0.5 | 0 | 9.45 |

| 117 | Rv3224B* | CAE55571 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 64 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.19 | 0.71 | 1 | 11.16 |

| 118 | Rv3267 | CAB07086 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN (CPSA-RELATED PROTEIN) | 473 | 0.9 | 11 | 0.2 | 0.51 | 2 | 4.67 |

| 119 | Rv3333c | CAA17105 | none | HYPOTHETICAL PROLINE RICH PROTEIN | 248 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.11 | 0.36 | 2 | 6.95 |

| 120 | Rv3351c | CAA15736 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 247 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.19 | 0.65 | 3 | 9.96 |

| 121 | Rv3388 | CAE55593 | PE_PGRS52 | PE/PGRS FAMILY PROTEIN | 697 | 0.8 | 8 | 0.16 | 0.29 | 0 | 4.68 |

| 122 | Rv3484 | CAB08707 | cpsA | POSSIBLE CONSERVED PROTEIN CPSA | 467 | 0.6 | 8 | 0.14 | 0.41 | 2 | 4.51 |

| 123 | Rv3492c | CAB08715 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL MCE ASSOCIATED PROTEIN | 138 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.41 | 1 | 9.3 |

| 124 | Rv3494c | CAA17731 | mce4F | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE4F | 531 | 0.7 | 5 | 0.12 | 0.51 | 4 | 5.15 |

| 125 | Rv3496c | CAA17733 | mce4D | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE4D | 429 | 0.8 | 11 | 0.25 | 0.47 | 2 | 4.31 |

| 126 | Rv3497c | CAA17734 | mce4C | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE4C | 322 | 0.5 | 6 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0 | 8.74 |

| 127 | Rv3498c | CAA17735 | mce4B | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE4B | 314 | 0.6 | 7 | 0.2 | 0.56 | 2 | 7.5 |

| 128 | Rv3499c | CAE55602 | mce4A | MCE-FAMILY PROTEIN MCE4A | 364 | 0.8 | 2 | 0.12 | 0.63 | 2 | 6.29 |

| 129 | Rv3533c | CAE55610 | PPE62 | PPE FAMILY PROTEIN | 546 | 0.8 | 7 | 0.12 | 0.2 | 0 | 5.51 |

| 130 | Rv3547 | CAB05059 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 124 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.23 | 0.5 | 1 | 9.33 |

| 131 | Rv3558 | CAE55613 | PPE64 | PPE FAMILY PROTEIN | 523 | 0.7 | 10 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0 | 4.06 |

| 132 | Rv3572 | CAB07146 | none | HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 151 | 0.9 | 3 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 4 | 4.55 |

| 133 | Rv3587c | CAA17856 | none | PROBABLE CONSERVED MEMBRANE PROTEIN | 228 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.17 | 0.38 | 4 | 5.13 |

| 134 | Rv3627c | CAB08829 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 432 | 0.8 | 7 | 0.15 | 0.31 | 3 | 5.81 |

| 135 | Rv3683 | CAA18005 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 292 | 0.6 | 5 | 0.16 | 0.4 | 4 | 8.95 |

| 136 | Rv3693 | CAA18015 | none | POSSIBLE CONSERVED MEMBRANE PROTEIN | 393 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.11 | 0.6 | 1 | 11.81 |

| 137 | Rv3705c | CAA18027 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 188 | 0.7 | 5 | 0.23 | 0.41 | 4 | 4.56 |

| 138 | Rv3749c | CAA18071 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 146 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.1 | 0.56 | 0 | 4.86 |

| 139 | Rv3796 | CAE55641 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 331 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.23 | 0.38 | 1 | 5.83 |

| 140 | Rv3802c | CAA17866 | none | PROBABLE CONSERVED MEMBRANE PROTEIN | 296 | 0.9 | 5 | 0.15 | 0.33 | 4 | 5.51 |

| 141 | Rv3878 | CAA17970 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL ALANINE RICH PROTEIN | 247 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0 | 3.87 |

| 142 | Rv3908 | CAB08093 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 226 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.15 | 0.64 | 0 | 7.38 |

| 143 | Rv3909 | CAB08092 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 762 | 0.6 | 14 | 0.18 | 0.61 | 2 | 5.66 |

| 144 | Rv3916c* | CAA16229 | none | CONSERVED HYPOTHETICAL PROTEIN | 240 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 6 | 4.57 |

Other characteristics of outer membrane proteins

In addition to the secondary structure, other properties also appear to be characteristic of OMPs of gram-negative bacteria and might be exploited as predictive parameters for unknown OMPs. Most OMPs of gram-negative bacteria have a low isoelectric point (pI) due to the excess of acidic residues58. The computed isoelectric points of the reference OMPs are all below 6.0 (Table S2) except for Omp32 of Delftia acidovorans which relies on basic amino acids for its function as a channel for organic acids59. Importantly, both MspA of M. smegmatis and OmpA of M. tuberculosis have an acidic isoelectric point (Table S2) indicating that this criterion is a valuable parameter to identify OMPs in mycobacteria as well. 32 of the 144 predicted OMPs of M. tuberculosis have a pI below 6.0 and an amphiphilicity score higher than 0.39. They may represent especially interesting candidates and are highlighted in grey in Table 2.

We explored the possibility of recognizing OMPs if they contain a protein domain characteristic of known OMPs. For this purpose we used the Pfam database which recognizes protein domains based on sequence alignments29, 60. None of the seven Pfam domains of OMPs of gram-negative bacteria were detected above the default cut-off of E-value 0.01 in proteins of M. tuberculosis. Significantly, both MspA of M. smegmatis and OmpA of M. tuberculosis do not have yet a Pfam domain. Hence, the current version of Pfam cannot be used to identify OMPs of M. tuberculosis.

Novel strategy for the experimental verification of the localization of proteins in bacterial outer membranes

To experimentally examine whether the predictions indeed identify outer membrane proteins, we chose two conserved hypothetical proteins, Rv1698 and Rv1973, that both have high scores for β-strand content and amphiphilicity (Table 2). Since it is often difficult to distinguish between inner and outer membrane proteins by subcellular fractionation experiments due to covalent linkages between the peptidoglycan, the arabinogalactan and the mycolic acids in mycobacteria and the concomitant mixing of membranes components, we resorted to a different strategy. The first step was to determine whether these proteins are associated with membranes. The next step was to demonstrate the surface accessibility of these proteins, because OMPs often expose extracellular loops. The confirmation of membrane association in combination with surface accessibility is experimental evidence for localization of a particular protein in the outer membrane because cytoplasmic, inner membrane and periplasmic proteins are inaccessible to reagents which are not able to penetrate the outer membrane. This holds true even if a protein is attached to cell wall components other than the outer membrane, e. g. the peptidoglycan, because it has to penetrate the outer membrane to become surface-accessible and is, thus, an OMP by definition. Examples of such proteins in gram-negative bacteria are TolC- and OmpA-like proteins22.

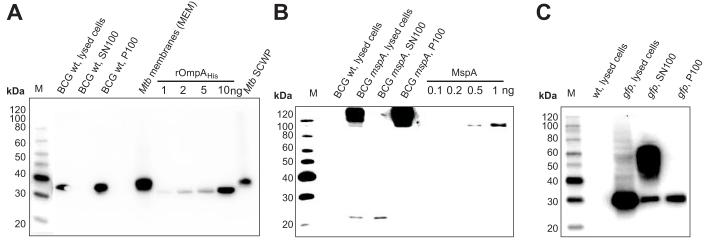

Membrane association of outer membrane proteins in M. bovis BCG and in M. tuberculosis

To examine the membrane association of the two selected putative OMPs, subcellular fractions of wild-type M. tuberculosis obtained as research materials from Colorado State University (CSU) were used: the cell membrane fraction which contains both inner and outer membrane proteins (MEM), the cell wall fraction (CW), the SDS-soluble cell wall proteins (SCWP), the water-soluble proteins (cytosol) and the culture filtrate (CFP). Since some proteins may not be expressed under standard growth conditions in M. tuberculosis and might therefore not be detectable in these fractions, we also expressed those proteins in M. bovis BCG. The cell envelope fraction (P100) and the fraction containing the water-soluble proteins were prepared by centrifuging a lysate of M. bovis BCG at 100,000xg. The ultracentrifugation pellet (P100) should contain the cell envelope including inner and outer membranes and the associated membrane proteins (total membrane). Then, the presence of three reference proteins in SDS extracts of these subcellular fractions was examined in Western blot experiments. OmpA of M. tuberculosis11 and the porin MspA of M. smegmatis7, 9 were shown to be integral OMPs which are accessible at the cell surface and were chosen as reference outer membrane proteins. The green fluorescent protein GFP was used as a marker for cytoplasmic proteins. OmpA is naturally expressed in wild-type M. bovis BCG and was detected only in the total membrane fraction and not in the SN100 fraction (Fig. 2A). This demonstrated that OmpA is associated with membranes of M. bovis BCG. OmpA was also detected in the fraction of M. tuberculosis containing the SDS-soluble cell wall proteins (Fig. 2A). This is consistent with previous findings that OmpA is a cell wall protein of M. tuberculosis19. The detection of OmpA in the cell membrane fraction of M. tuberculosis (Fig. 2A) which should contain mainly inner membrane proteins is an example of the aforementioned difficulties in separating inner and outer membranes of mycobacteria in fractionation experiments.

Fig. 2. Membrane association of the outer membrane proteins marker proteins OmpA and MspA in M. bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis.

Subcellular fractions of M. tuberculosis (from CSU) and of M. bovis BCG were prepared and extracted with 2% SDS. A total of 150 μg protein per of M. tuberculosis fraction was analyzed in an SDS-polyacrylamide (10%) gel and blotted on a PVDF membrane for OmpA (A), MspA (B), and GFP (C). The same cell equivalents were loaded for each M. bovis BCG sample. The proteins were detected using specific antisera and an anti-rabbit antibody-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate.

A. Lanes are (from left to right): M: MagicMark™ XP Western standard (Invitrogen), lysed cells of M. bovis BCG, supernatant SN100 and pellet P100 of lysed cells of M. bovis BCG. M. tuberculosis (Mtb) cell membrane extracts (MEM) and SDS-soluble cell wall proteins (SCWP) of Mtb. Recombinant OmpAHis without the putative signal peptide (44 N-terminal amino acids) was purified from E. coli and was used as a reference. Note that the native proteins of M. tuberculosis and M. bovis BCG have a lower electrophoretic mobility than their recombinant protein because the N-terminus of OmpA is not cleaved14.

B. Lanes are (from left to right): M: MagicMark™ XP Western standard (Invitrogen), lysed cells of wild-type M. bovis BCG and of M. bovis BCG overexpressing mspA from the plasmid pMN013, supernatant SN100 and pellet P100 of lysed cells of M. bovis BCG overexpressing mspA from the plasmid pMN013. Recombinant MspA without the signal peptide was purified from E. coli and was used as a reference.

C. Lanes are (from left to right): M: MagicMark™ XP Western standard (Invitrogen), lysed cells of wild-type M. bovis BCG and of M. bovis BCG overexpressing mycgfp2+ from the plasmid pMN437, supernatant SN100 and pellet P100 of lysed cells of M. bovis BCG overexpressing mycgfp2+. The 60 kDa band in the supernatant fraction represents the GFP dimer, which did not dissociate because the samples were not boiled before loading of the gel.

MspA-like porins are not present in M. bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis. Therefore, we used a recombinant M. bovis BCG strain which expressed MspA from the plasmid pMN013 (Table 1). The Western blot clearly shows that the oligomeric form of MspA is completely associated with the total membrane fraction P100 (Fig. 2B) while only a tiny fraction of monomeric MspA was visible in the soluble fraction. This is consistent with previous experiments which demonstrate that MspA is a membrane protein6, 61.

By contrast, GFP was almost only detected in the fraction containing water-soluble proteins after ultracentrifugation of lysed cells of a recombinant M. bovis BCG strain expressing gfp from plasmid pMN437 (Fig. 2C).

In conclusion these results demonstrated that the membrane fraction of M. bovis BCG was separated from the supernatant containing the soluble proteins by ultra-centrifugation, and that the outer membrane marker proteins OmpA and MspA are associated with the total membrane fraction. Hence, we showed that a simple ultracentrifugation step at 100,000xg is sufficient to separate membrane-bound proteins form soluble proteins in mycobacteria.

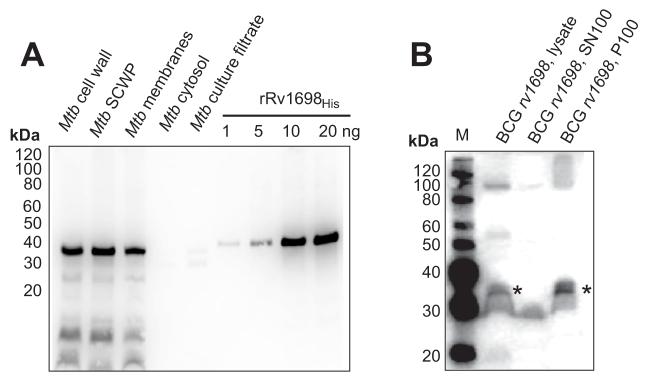

Rv1698 is associated with membranes

Rv1698 is annotated as a conserved hypothetical protein and has a β-strand score of 0.19 and an amphiphilicity score of 0.55 (Table 2). These are values similar to many other known OMPs (Table 2). Furthermore, Rv1698 had no cysteines and had a low pI which are known characteristics of OMPs of gram-negative bacteria. Further computational analysis confirmed the predictions that Rv1698 has a signal peptide from amino acids 1 through 25 (SignalP 3.032), and has no hydrophobic α-helix in addition to that in the putative signal peptide (TMHMM34). To detect Rv1698 in subcellular fractions, we produced specific antibodies in rabbits and mice which were immunized with the recombinant Rv1698 protein purified from E. coli. A Western blot demonstrated that the antibody specifically recognized a ≈35 kDa protein in SDS extracts of the cell wall fraction (CW, SCWP) and in the total membrane fraction of wild-type M. tuberculosis H37Rv, but not in the cytosol fraction and in the culture filtrate (Fig. 3A). A protein of a similar size was recognized in samples of recombinant Rv1698 purified from E. coli (Fig. 3A) and in recombinant M. bovis BCG, which overexpresses Rv1698 (Fig. 3B). Further, ELISA showed a significant signal increase for cell lysates of M. bovis BCG strain when rv1698 was overexpressed from the plasmid pMN335 compared to wt (not shown). These results indicate that the antibodies specifically recognize the Rv1698 protein. Importantly, Rv1698 was associated only with the membrane fraction P100 of an M. bovis BCG strain overexpressing rv1698, but not with the supernatant SN100 containing water-soluble proteins. These results clearly show that Rv1698 is a membrane protein.

Fig. 3. Expression and membrane association of Rv1698 in mycobacteria.

A. Subcellular localization of Rv1698 in M. tuberculosis. Subcellular fractions (obtained from CSU) were extracted with 2% SDS. A total of 50 μg protein of each fraction was analyzed in an SDS-polyacrylamide (10%) gel. The samples were blotted on a PVDF membrane and detected with an Rv1698-specific antibody. M: MagicMark™ XP Western standard (Invitrogen); SCWP: SDS-soluble cell wall proteins. Recombinant Rv1698His without the putative signal peptide (25 N-terminal amino acids) was purified from E. coli and was used as a reference.

B. Expression and membrane association of Rv1698 in M. bovis BCG. The supernatant SN100 and the pellet P100 of lysed cells of M. bovis BCG overexpressing rv1698 from the plasmid pMN335 were prepared by ultracentrifugation at 100,000xg. These samples were extracted with 2% SDS and the same cell equivalents were analyzed in an SDS-polyacrylamide (10%) gel. The gel was blotted on a PVDF membrane and detected with an anti-Rv1698 serum. The Rv1698 monomer is marked with a star. M: MagicMark™ XP Western standard (Invitrogen).

Rv1973 is associated with membranes

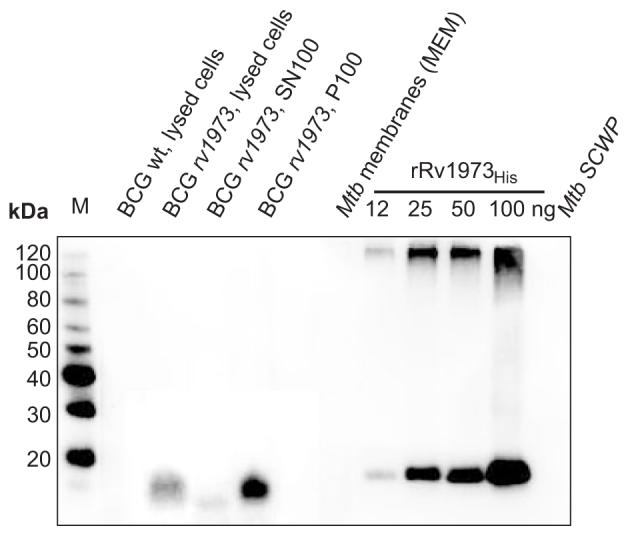

To further validate the bioinformatic predictions, we chose to determine the subcellular localization of Rv1973 as another putative OMP with no homologs of known function. This protein has high scores for both β-strand content (0.24) and amphiphilicity (0.65) (Table 2). It is annotated as a “possible conserved Mce associated membrane protein”. A detailed computational analysis confirmed the predictions that Rv1973 has a signal peptide from amino acids 1 through 18 (SignalP 3.032), and has no hydrophobic α-helix in addition to that in the putative signal peptide (TMHMM34). To detect Rv1973 in subcellular fractions, we produced specific antibodies in rabbits which were immunized with the recombinant Rv1973protein purified from E. coli. A Western blot demonstrated that the antiserum recognized the purified Rv1973His protein of ≈15 kDa (Fig. 4). This apparent molecular mass of monomeric Rv1973 is identical to the theoretical mass for Rv1973 after cleavage of the predicted signal peptide. No protein was recognized in wild-type M. bovis BCG, which does not contain the rv1973 gene (Fig. 4). By contrast, a 15 kDa protein was detected in lysates of a recombinant M. bovis BCG strain overexpressing rv1973 from the plasmid pMN339 (Table 1). This demonstrated that the antiserum specifically recognized Rv1973 in M. bovis BCG. Then, subcellular fractions of an M. bovis BCG strain overexpressing rv1973 from the plasmid pMN339 were examined using this antiserum. Rv1973 was associated with the total membrane fraction P100 but not with the supernatant SN100 containing water-soluble proteins. No signal was obtained for the subcellular fractions of wild-type M. tuberculosis. This indicates that rv1973 is not expressed in wt M. tuberculosis under the growth concentrations used for preparation of these fractions to levels which are detectable in this Western blot experiment.

Fig. 4. Membrane association of Rv1973 in M. bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis.

Subcellular fractions of M. tuberculosis (from CSU) and of M. bovis BCG were extracted with 2% SDS. A total of 150 μg protein per fraction of M. tuberculosis was analyzed in an SDS-polyacrylamide (10%) gel. The same cell equivalents were loaded for each M. bovis BCG sample. The samples were blotted on a PVDF membrane and detected with an anti-Rv1973 serum. Lanes are (from left to right): M: MagicMark™ XP Western standard (Invitrogen), lysed cells of M. bovis BCG, supernatant SN100 and pellet P100 of lysed cells of M. bovis BCG overexpressing rv1973 from the plasmid pMN339, Mtb cell membrane extracts (MEM). Recombinant Rv1973His without the putative signal peptide (lacking the first 18 N-terminal amino acids) was purified from E. coli and used as a reference.

Whole cell ELISA experiments to demonstrate surface accessibility of marker outer membrane proteins

It was shown previously that the porin MspA could be detected by antibodies on the surface of M. smegmatis cells in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA)7. Therefore, we examined whether this method was also useful in detecting OMPs in M. bovis BCG. The ELISA with whole cells of wild-type M. bovis BCG and a recombinant strain of M. bovis BCG overexpressing the native ompA gene showed that more than 80% of OmpA was associated with the total membrane fraction P100 (Fig. S1A) in agreement with the Western blot analysis (Fig. 2A). Significantly, the signal was higher for whole cells of M. bovis BCG overexpressing OmpA compared to wt M. bovis BCG. This demonstrated that OmpA is surface accessible in M. bovis BCG. These results are consistent with the localization of OmpA in the outer membrane of M. tuberculosis as shown recently14. Similarily, more than 90% of MspA was associated with the total membrane fraction P100 (Fig. S2B) consistent with the Western blot analysis. However, MspA was not detected in whole cells of the recombinant M. bovis BCG strain in contrast to M. smegmatis for unknown reasons. It can be concluded that whole cell ELISA can be used to detect some but not all OMPs.

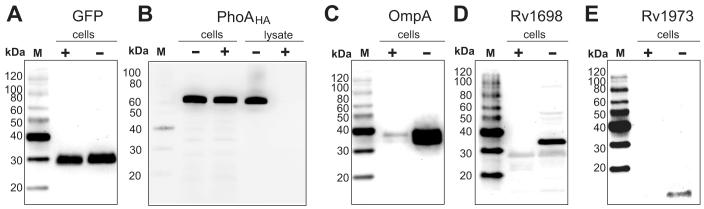

Rv1698 and Rv1973 proteins are surface-accessible in M. bovis BCG

As an alternative method to demonstrate surface accessibility of proteins, we employed protease accessibility experiments as described previously for a mycobacterial surface protein46. Whole cells of wt M. bovis BCG were incubated with and without proteinase K. The cytoplasmic GFP and the periplasmic PhoAHA proteins were clearly protected from proteinase K in M. bovis BCG cells (Fig. 5A and 5B). This was not due to the resistance to digestion as shown by the complete degradation of PhoAHA in cell lysates (Fig. 5B). The finding that PhoA is not surface-accessible is consistent with our previous observation that the activity of PhoA depends on the presence of porins in the outer membrane of M. smegmatis45 and the localization of PhoA in the periplasm of Gram-negative bacteria62. These results also demonstrated that the outer membrane of M. bovis BCG as a permeability barrier to proteinase K is still intact under these experimental conditions. By contrast, the outer membrane marker OmpA is significantly degraded by proteinase K in whole cells of M. bovis BCG (Fig. 5C). Importantly, both Rv1698 and Rv1973 were completely degraded by proteinase K in recombinant M. bovis BCG strains in contrast to the control samples without proteinase K (Fig. 5D and 5E). Thus, we have shown that both Rv1698 and Rv1973 are membrane proteins and are detectable on the cell surface. This demonstrates that Rv1698 and Rv1973 are indeed outer membrane proteins of M. tuberculosis.

Fig. 5. Surface accessibility of OmpA, Rv1698 and Rv1973 in M. bovis BCG.

Proteinase K accessibility experiments were performed using wt M. bovis BCG (OmpA), and M. bovis BCG strains carrying the plasmids pMN437 (psmyc-mycgfp2+), pML970 (psmyc-phoAHA), pMN335 (pimyc-rv1698), and pMN339 (pimyc-rv1973). The strains were incubated with (+) or without (-) proteinase K at 37°C for 30 min. Extracts of whole cells with 1% SDS and cell lysates were separated on an SDS-polyacrylamide (10%) gel. Immunoblots were performed using anti-GFP (A), anti-HA (B), anti-OmpA (C), anti-Rv1698 (D) and anti-Rv1973 (E) antibodies. The MagicMark™ XP western standard (lanes M) was used as reference. Note the apparent molecular mass of PhoAHA is significantly larger than the theoretical molecular mass of 52.5 kDa for the mature protein lacking the signal peptide. This is probably due to acylation of PhoA as shown previously89.

DISCUSSION

Our aim was to identify integral OMPs of M. tuberculosis, which do not have any homology to OMPs in gram-negative bacteria except for OmpA11. The porin MspA of M. smegmatis provided the proof of principle that integral mycobacterial OMPs share similar structural features with OMPs of gram-negative bacteria: The presence of a signal peptide, a β-barrel structure, and the absence of hydrophobic α-helices in the mature protein9. These features were exploited in a straightforward bioinformatic analysis consisting of multiple steps as depicted in Fig. 1A.

Prediction of exported M. tuberculosis proteins

SignalP 3.0 identified 587 proteins of M. tuberculosis with a signal peptide (Table S2) which, as in other bacteria, targets proteins to the general export system SecYEG for translocation across the cytoplasmic membrane49. This is a relatively large number in comparison to 452 and approximately 300 exported proteins predicted by SignalP for the bacterial model organisms E. coli (www.cf.ac.uk/biosi/staff/ehrmann/tools/ecce/ecce.htm) and B. subtilis63, respectively, and probably reflects the complexity of the mycobacterial cell envelope. It should be noted that this difference is not caused by different genome sizes which are very similar for all three species 64-66. The proteins of M. tuberculosis predicted to be exported include 260 proteins of unknown function and 87 out of 168 proteins of the PE- and PPE protein families. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and MS identified 257 secreted proteins in the culture filtrate of M. tuberculosis67. 121 of these secreted proteins are included in our list of exported proteins (Table S2).

Prediction of inner membrane proteins of M. tuberculosis

Our list of exported proteins of M. tuberculosis contains 134 proteins with a hydrophobic α-helix in addition to that in the signal peptide as predicted by TMHMM 2.0. All of these proteins are in the list of 787 possible transmembrane proteins provided by the PEDANT database (pedant.gsf.de) with the exception of Rv0956 and Rv2267. Manual re-analysis confirmed that both mature proteins indeed contain a transmembrane α-helix. These results also showed that the vast majority of inner membrane proteins of M. tuberculosis do not have a signal peptide. This is consistent with the findings for other bacteria that most IMPs are targeted to the inner membrane by the signal peptide recognition particle SRP and a non-cleavable signal anchor helix, which is more hydrophobic than the signal peptide68.

Prediction of outer membrane proteins of M. tuberculosis

It is obvious that the Jnet algorithm underestimates the β-strand contents of OMPs. For example the β-strand contents of MspA and OmpF as derived from their three-dimensional structures exceed 60%9, 53, but were predicted to be 27% and 23%, respectively, by Jnet (Table 1). This appears to affect all proteins similarly because the reference OMPs are still among the proteins with the highest β-strand content (Fig. 1). Thus, it is concluded that the Jnet-derived β-strand percentage is valid as a relative parameter for ranking purposes. However, some of the reference proteins have a very low β-strand content (Fig 1B) and thus our threshold for this parameter is not very discriminative. By contrast, the β-strand amphiphilicity offers a better discriminating power since the reference proteins have on average a higher value than the average Mtb proteins (Fig. 1B). Out of the 154 eliminated proteins, 139 lacked sufficiently amphiphilic β-strands and 69 did not meet the threshold for β-strand content. 54 of these proteins did not meet both criteria.

In contrast to all other predictors of bacterial OMPs23, 25, 55, 69, the algorithm in our approach was not trained with a specific set of known transmembrane β-barrel proteins. This avoided any bias resulting from over-fitting to a data set of OMPs of gram-negative bacteria, which, except for basic structural parameters, is not appropriate for identifying OMPs of M. tuberculosis.

Three different predictors of β-barrel proteins trained to detect OMPs of gram-negative bacteria were previously used to identify putative OMPs of M. tuberculosis25. Parameters which were used to distinguish OMPs from other proteins included a C-terminal sequence motif comprising phenylalanine at the last position in their prediction algorithm, which is typical for porins of gram-negative bacteria26. However, none of the currently identified integral OMPs of mycobacteria (MspA, OmpA, Rv1698 and Rv1973) contain this C-terminal phenylalanine or sequence motif25. Due to the inappropriate choice of predictive parameters and the use of algorithms that were probably over-fitted to an inappropriate training set, it is not surprising that only 21 proteins out of 144 proteins in our list of putative OMPs were also predicted by Pajon et al. Their list of predicted OMPs includes a large number of obviously false positives such as cytoplasmic proteins (kinase Rv0014c (MT0017), the DNA-binding protein HsdS (Rv2761c, MT2831), the transcriptional regulator CopG (Rv1398c, MT1442)), inner membrane proteins such as the sugar permease UgpA (Rv2835c, MT2901), the efflux protein EfpA (Rv2846c, MT2912) and the ammonium transporter AmtB (Rv2920c, MT2988) and lipoproteins such as LpqN (Rv0583c, MT0611) and LpqG (Rv3623, MT3725), which are not transmembrane β-barrel proteins but are anchored by a fatty acid residue attached to an N-terminal cysteine of the processed protein70. It should be noted that most of the cell wall proteins as identified by subcellular fractionation and mass spectroscopy20 are enzymes with locations other than the OM. These examples highlight the crucial importance of combining biological knowledge with bioinformatic methods to compile a useful list of putative OMPs.

However, despite considerable efforts to exclude proteins with subcellular localizations other than the OM, it is almost certain that our list of 144 putative OMPs (Table 2) also contains false positives such as periplasmic or secreted proteins. Indeed, 39 out of the 144 putative OMPs were classified as secreted proteins based on a proteomic analysis of proteins in the culture filtrate of M. tuberculosis67. Careful subcellular localization experiments are required to determine which of these proteins are truly secreted and which might be present in the supernatant due to cell lysis71, 72 or shedding of membrane vesicles as was observed for gram-negative bacteria73, 74. Further, it is apparent that our approach will miss the following classes of OMPs if they exist in mycobacteria: (i) OMPs in which the OM domain represents only a minor part of a protein with large or multiple extracellular or periplasmic domains, (ii) OMPs that do not contain a classical signal peptide detected by SignalP such as OmpA, which has been shown to be an OMP14 and fulfills all other criteria defined above as characteristic of OMPs such as high β-strand content, high amphiphilicity and low pI (Table 1), and (iii) outer membrane lipoproteins that use additional fatty acid residues as OM anchors such as OprM of Pseudomonas aeruginosa75.

The mycobacterial cell entry proteins

The mce1A gene of M. tuberculosis was identified because its expression enabled Escherichia coli to enter epithelial cells76. This gene is part of an operon comprising yrbEA, yrbEB, five mce genes (mceA, mceB, mceC, mceD, mceF) and a gene encoding a lipoprotein. Four copies of this operon are present in the M. tuberculosis genome (mce1-4)77. Interest in these operons has been sparked by findings that mce deletion mutants affected the virulence of M. tuberculosis in mice78-81. Our analysis predicts all Mce proteins as putative OMPs (Table 2). The only exception is Mce2C (Rv0591) which did not meet the SignalP cutoff value and is, therefore, not in the list of exported proteins. A manual re-examination showed that Mce2C may have a signal peptide and has a secondary structure compatible with that of an OMP. Thus, it is predicted that all mce genes code for OMPs of M. tuberculosis. Based on the observations that the mce genes are in the same operon as genes encoding a YrbEA/YrbEB ABC transporter we propose that the Mce proteins form an OM complex which connects to the inner membrane ABC transporters. This hypothesis is currently under investigation in our laboratory.

The PE/PPE proteins

The list of putative OMPs of M. tuberculosis includes 2 PE, 9 PE-PGRS and 10 PPE proteins (Table 2). These proteins belong to large families comprising proteins named for conserved proline and glutamate residues near their N termini82, 83. In addition to these motifs, the family members share homologous N-terminal domains of approximately 110 amino acids for PE proteins and 180 amino acids for PPE proteins83. It has been proposed that the PE/PPE proteins contribute to antigenic variation of M. tuberculosis. Consistent with this function is the accumulating evidence that at least some of these proteins are accessible at the cell surface46, 84, 85. In this regard, it is striking that Rv1386 (PE15), which consists solely of a PE domain (70 amino acids without the predicted signal peptide), has high scores for both β-strand content and amphiphilicity (Table 2). This is consistent with the recent finding that the PE domain might be a cell wall anchor86. However, the vast majority of the PE/PGRS proteins are not predicted as OMPs. This might be a problem of the algorithm which may not be able to detect secondary structural elements in these very unusual sequences. Alternatively, the PE/PGRS proteins may have different functions and subcellular localizations. The formation of protein complexes between paired PE/PPE proteins87 is another finding which attests to the functional diversity of PE proteins.

Experimental evidence for the localization of proteins in mycobacterial outer membranes

In this study, we have developed a new experimental approach to detect mycobacterial OMPs. A single 100,000xg centrifugation of lysed cells of M. bovis BCG is sufficient to separate membrane proteins including OmpA and MspA from soluble proteins such as GFP. Surface accessibility in whole cells of M. bovis BCG was demonstrated for OmpA by both ELISA7 and protease experiments46. This demonstrated unequivocally that OmpA is anchored in the outer membrane of M. bovis BCG consistent with its localization in the cell wall fraction of M. tuberculosis (Fig. 1A) and its function as a pore-forming protein11, 14. The combination of establishing the association with membranes and the surface accessibility provides an alternative method to demonstrate whether the protein of interest is an OMP. This method is considerably less laborious compared to the recently improved protocol for subcellular fractionation of mycobacteria that consists of two cell lysis steps and at least six centrifugations19. An additional advantage is that it avoids the problem of mixing of inner membrane and cell wall fractions which can render localization experiments useless for certain proteins20. This was a problem in particular for M. bovis BCG where substantial amounts of the inner membrane marker protein NADH oxidase were found in all subcellular fractions19. An obvious limitation of our approach is that it cannot be applied to OMPs which do not have surface-exposed loops or whose surface-exposed loops are not accessible. It appears that protease accessibility experiments are superior to antibody-based methods to detect surface proteins such as immunogold staining or whole cell ELISA experiments. This may be due to the unspecificity of cleavage by proteinase K which is not restricted to a particular position in the loops of OMPs in contrast to antibodies which need to bind to epitopes consisting of 5 to 10 amino acids88.

Conclusions