Abstract

There is increasing evidence for a role of dopamine in the development of obesity. More specifically, dopaminergic hypofunction might lead to (over)compensatory food intake. Overeating and resulting weight gain may be induced by genetic predisposition for lower dopaminergic activity, but might also be a behavioral mechanism of compensating for decreased dopamine signaling after dopaminergic overstimulation, for example after smoking cessation or overconsumption of high palatable food. This hypothesis is in line with our incidental finding of increased weight gain after discontinuation of pharmaceutical dopaminergic overstimulation in rats. These findings support the crucial role of dopaminergic signaling for eating behaviors and offer an explanation for weight-gain after cessation of activities associated with high dopaminergic signaling. They further support the possibility that dopaminergic medication could be used to moderate food intake.

Background

Eating and dopaminergic signaling are closely related. Food reward and food-reward associated stimuli both elevate dopamine levels in crucial components of the brain reward circuits [1,2]. In fact, food might be the most important natural stimulator of the reward system in the brain [3]. Therefore, overeating may represent an attempt to compensate for hedonic reward deficiency under conditions of reduced dopaminergic activity.

Relative dopaminergic deficiency can be caused by different conditions, for example genetic predisposition or after adaptive downregulation of the dopaminergic system due to preceding overstimulation. Thus, substitutional food intake might explain weight gain after smoking cessation, during antipsychotic medication and in obesity.

A rebound effect of eating behavior after dopaminergic overstimulation could account for the weight gain often associated with smoking cessation, because during smoking, nicotine excites dopamine-containing cells in the ventral tegmental area, resulting in dopamine release in mesolimbic and mesocortical projections [4].

Additionally, an increase in body weight is a side effect of many commonly used drugs. Particularly, antidopaminergically acting neuroleptics, tricyclic antidepressants, lithium, and some anticonvulsants contribute to weight gain. To date, the underlying mechanisms are still poorly understood although interactions with the dopamine system have been implicated [5].

Similarly, in obesity body mass index is negatively correlated with D2 receptor density in the striatum [6,7], which might reflect neuroadaptation secondary to overstimulation with palatable food [8,9]. Thus, increased food intake may be a compensatory behavior for low dopaminergic drive [10]. Stice et al. recently reported that lower striatal activation in response to food intake was associated with obesity. Furthermore, this relation was modulated by genetically determined D2 receptor availability [11].

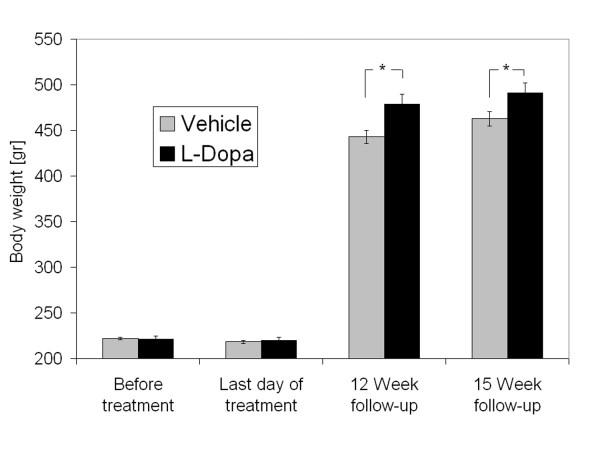

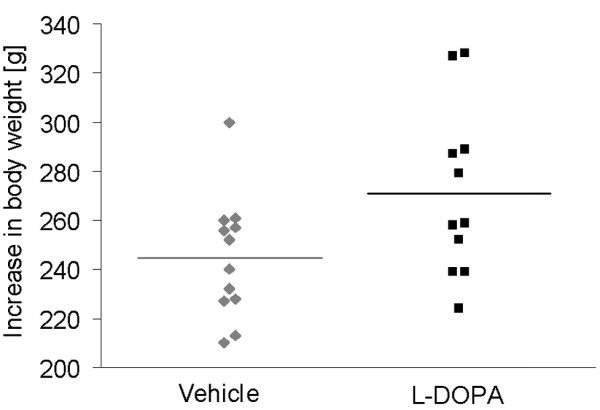

These results are in line with our own incidental observation of increased body weight after pharmaceutical dopaminergic overstimulation in an animal model. Regulation of feeding by acute dopaminergic stimulation has already been demonstrated [e.g. [12]], but rebound effects after overstimulation have not been reported. Food restricted rats received the dopamine precursor levodopa over five days and were then withdrawn from dopaminergic medication. Subsequently, animals were allowed to feed ad libitum. Over the next 12 weeks the intervention group gained 15% more weight than the vehicle group (p < 0.01) and continued to be heavier at 16 week follow-up (p < 0.05, see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Effects of L-DOPA treatment on body weight. Rats treated previously with L-DOPA had the same weight as rats treated with a vehicle solution before and immediately after the treatment, but gained more weight during a follow-up period. Results represent the means ± SD of body weight for each group measured at the respective time point. Asterisk indicates a significant difference (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Individual data on increase in body weight. All but one rat from the vehicle group gained less weight than the mean weight gain of the L-DOPA group. About half of the rats from the L-DOPA group gained more weigh than almost all rats from the vehicle group. Results represent the individual difference in body weight for each rat from both groups between the last day of treatment and the 15-week follow-up.

Discussion

There is growing evidence for a role of dopaminergic signaling in the development of obesity. Compensatory eating due to hypofunctionality of the dopaminergic system can not only be based on genetically determined factors, but might also be induced by preceding overstimulation with natural stimulation or pharmacological enhancement. The later was demonstrated by our incidental finding that a decreased dopaminergic tone (relative to a preceding period of extrinsically elevated dopaminergic drive) enhanced weight gain after a period of food deprivation.

While acute administration of levodopa in combination with carbidopa leads to an increase in brain dopamine levels [13,14], diminished dopaminergic responses to external stimulation have been observed after repeated levodopa administration [15-17]. (Over)stimulation of the dopaminergic system by intake of dopaminergic substances or chronic overconsumption of food [10], leads to adaptational processes in the dopaminergic system [18,19]. This downregulation is likely to be complex and seems to involve decreased dopamine synthesis [20], and decreased post-synaptic receptor expression [21,22]. In addition to hedonic or motivational changes in response to food, interactions of the dopaminergic system with adiposity signals might have induced changes in feeding behavior [see [23] for review]. We assume that in our study the hyperdopaminergic state during the repeated levodopa administration induced a hypodopaminergic state after drug discontinuation, which resulted in rebound effects of weight gain as a compensatory mechanism [3].

Dopaminergic modulation of such rebound effects can explain weight-gain after cessation of activities associated with high dopaminergic signaling. Additionally, they offer explanations for individual differences and pharmacological treatment related to post-smoking weight-gain. For instance, in smokers with dopamine receptor polymorphism variants associated with lower dopamine drive, food seems to have greater reinforcing effects as indicated by an increased weight gain after smoking cessation relative to individuals without this variant [24,25].

Our results also raise the possibility that dopaminergic medication may be helpful in preventing compensatory food intake and offer a potential pharmacological treatment of obesity [26]. Increased food reinforcement and weight gain in ex-smokers can be attenuated by bupropion, a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that raises brain dopamine levels and increases receptor activation [27]. Similarily, after an increase in brain synaptic dopamine via pharmacological inhibition of the dopamine transporter, obese men reduced their energy intake by one third compared to placebo during a meal of highly palatable food [28]. On the other hand dopaminergic treatment in Parkinson's disease or Restless Legs Syndrome may be associated with the inverse effect, i.e. an unwanted weight loss [29].

Conclusion

Our findings support evidence of dopaminergically induced eating behavior to compensate for low dopaminergic signaling. They should alert us to the possibility that overeating after withdrawal might be a potential side-effect of dopaminergic stimulation. On the other hand, our results also raise the possibility that dopaminergic medication may be helpful in preventing compensatory food intake. These possibilities and limitations of dopaminergic stimulation on motivation merit further investigation.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JR performed statistical analysis of data, and prepared the final manuscript. OS organized the study and collected the data. BC participated in the conception and design of the main study. IB participated in preparing the final manuscript. HW and SK designed and supervised the main study, SK drafted an initial manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Volkswagen Stiftung (Az.: I/80 708), as well as Marie Curie Research and Training Network: Language and Brain (RTN:LAB) funded by the European Commission (MRTN-CT-2004-512141) as part of its Sixth Framework Programme, Neuromedical Foundation Muenster and BMBF-consortium Dopaminergic learning enhancement (01GW0520).

Contributor Information

Julia Reinholz, Email: reinhj@uni-muenster.de.

Oliver Skopp, Email: oskopp@uni-muenster.de.

Caterina Breitenstein, Email: caterina.breitenstein@uni-muenster.de.

Iwo Bohr, Email: iwo.bohr@uni-muenster.de.

Hilke Winterhoff, Email: winterh@uni-muenster.de.

Stefan Knecht, Email: knecht@uni-muenster.de.

References

- Bassareo V, Di Chiara G. Differential influence of associative and nonassociative learning mechanisms on the responsiveness of prefrontal and accumbal dopamine transmission to food stimuli in rats fed ad libitum. J Neurosci. 1997;17:851–861. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00851.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small DM, Jones-Gotman M, Dagher A. Feeding-induced dopamine release in dorsal striatum correlates with meal pleasantness ratings in healthy human volunteers. Neuroimage. 2003;19:1709–1715. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Leddy JJ. Food reinforcement. Appetite. 2006;46:22–25. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauer JA. Neuroscience: a home for the nicotine habit. Nature. 2005;436:31–32. doi: 10.1038/436031a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudie AJ, Halford JC, Dovey TM, Cooper GD, Neill JC. H(1)-histamine receptor affinity predicts short-term weight gain for typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:2209–2211. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Logan J, Pappas NR, Wong CT, Zhu W, Netusil N, Fowler JS. Brain dopamine and obesity. Lancet. 2001;357:354–357. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03643-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haltia LT, Rinne JO, Merisaari H, Maguire RP, Savontaus E, Helin S, Nagren K, Kaasinen V. Effects of intravenous glucose on dopaminergic function in the human brain in vivo. Synapse. 2007;61:748–756. doi: 10.1002/syn.20418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colantuoni C, Schwenker J, McCarthy J, Rada P, Ladenheim B, Cadet JL, Schwartz GJ, Moran TH, Hoebel BG. Excessive sugar intake alters binding to dopamine and mu-opioid receptors in the brain. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3549–3552. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200111160-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello NT, Lucas LR, Hajnal A. Repeated sucrose access influences dopamine D2 receptor density in the striatum. Neuroreport. 2002;13:1575–1578. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200208270-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C, Strachan S, Berkson M. Sensitivity to reward: implications for overeating and overweight. Appetite. 2004;42:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Spoor S, Bohon C, Small DM. Relation between obesity and blunted striatal response to food is moderated by TaqIA A1 allele. Science. 2008;322:449–452. doi: 10.1126/science.1161550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner TG, Zigmond MJ, Stricker EM. Effects of dopaminergic agonists and antagonists of feeding in intact and 6-hydroxydopamine-treated rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1977;201:386–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raevskii KS, Gainetdinov RR, Budygin EA, Mannisto P, Wightman M. Dopaminergic transmission in the rat striatum in vivo in conditions of pharmacological modulation. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2002;32:183–188. doi: 10.1023/A:1013931609942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M, Morales I, Gonzalez-Mora JL, Gomez I, Sabate M, Dopico JG, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Obeso JA. Different levodopa actions on the extracellular dopamine pools in the rat striatum. Synapse. 2007;61:61–71. doi: 10.1002/syn.20342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannan T, Prikhojan A, Yahr MD. Effects of repeated administration of l-DOPA and apomorphine on circling behavior and striatal dopamine formation. Brain Res. 1998;784:148–153. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(97)01191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opacka-Juffry J, Ashworth S, Ahier RG, Hume SP. Modulatory effects of L-DOPA on D2 dopamine receptors in rat striatum, measured using in vivo microdialysis and PET. J Neural Transm. 1998;105:349–364. doi: 10.1007/s007020050063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata M, Kanazawa I. Repeated L-dopa administration reduces the ability of dopamine storage and abolishes the supersensitivity of dopamine receptors in the striatum of intact rat. Neurosci Res. 1993;16:15–23. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(93)90004-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South T, Huang XF. High-fat diet exposure increases dopamine D2 receptor and decreases dopamine transporter receptor binding density in the nucleus accumbens and caudate putamen of mice. Neurochem Res. 2008;33:598–605. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9483-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader MA, Morgan D, Gage HD, Nader SH, Calhoun TL, Buchheimer N, Ehrenkaufer R, Mach RH. PET imaging of dopamine D2 receptors during chronic cocaine self-administration in monkeys. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1050–1056. doi: 10.1038/nn1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imperato A, Obinu MC, Carta G, Mascia MS, Casu MA, Gessa GL. Reduction of dopamine release and synthesis by repeated amphetamine treatment: Role in behavioral sensitization. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;317:231–7. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(96)00742-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagher A, Bleicher C, Aston JA, Gunn RN, Clarke PB, Cumming P. Reduced dopamine D1 receptor binding in the ventral striatum of cigarette smokers. Synapse. 2001;42:48–53. doi: 10.1002/syn.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordet R, Ridray S, Schwartz JC, Sokoloff P. Involvement of the direct striatonigral pathway in levodopa-induced sensitization in 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:2117–2123. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmiter RD. Is dopamine a physiologically relevant mediator of feeding behavior? Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Shields PG, Wileyto EP, Audrain J, Pinto A, Hawk L, Krishnan S, Niaura R, Epstein L. Pharmacogenetic investigation of smoking cessation treatment. Pharmacogenetics. 2002;12:627–634. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Berrettini W, Pinto A, Patterson F, Crystal-Mansour S, Wileyto EP, Restine SL, Leonard DG, Shields PG, Epstein LH. Changes in food reward following smoking cessation: a pharmacogenetic investigation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;174:571–577. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1823-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcioglu A, Wurtman RJ. Effects of phentermine on striatal dopamine and serotonin release in conscious rats: in vivo microdialysis study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:325–328. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Niaura R. Applying genetic approaches to the treatment of nicotine dependence. Oncogene. 2002;21:7412–7420. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leddy JJ, Epstein LH, Jaroni JL, Roemmich JN, Paluch RA, Goldfield GS, Lerman C. Influence of methylphenidate on eating in obese men. Obes Res. 2004;12:224–232. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palhagen S, Lorefalt B, Carlsson M, Ganowiak W, Toss G, Unosson M, Granerus AK. Does L-dopa treatment contribute to reduction in body weight in elderly patients with Parkinson's disease? Acta Neurol Scand. 2005;111:12–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2004.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]