Abstract

In the United States, bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is the treatment most used for superficial bladder cancer. Patients with carcinoma in situ (CIS) treated with intravesical BCG plus interferon have a 60% to 70% chance of a complete and durable response if they were never treated with BCG or if they failed only 1 prior induction or relapsed more than a year from induction. Intravesical gemcitabine is safe, but its usefulness for BCG-refractory patients is unclear. Valrubicin, approved for intravesical treatment of BCG-refractory CIS of the bladder, has efficacy and acceptable toxicity. Cystectomy should be considered in high-risk, non-muscle-invasive cancer, particularly if intravesical therapy failed.

Key words: Bladder cancer, Bacillus Calmette-Guérin, Cystectomy, Gemcitabine, Valrubicin

The management of superficial bladder cancer requires a clear understanding of diagnostic, prognostic, and treatment parameters. Cystoscopy remains the gold standard for detection, but despite good visualization and resection, bladder cancers recur frequently. Because of this, a variety of drugs has been used intravesically. The most commonly used drug in the United States is bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), both with and without interferon and mitomycin. Table 1 lists the main agents used for intravesical therapy.

Table 1.

Agents for Intravesical Therapy

| Adriamycin |

| BCG |

| BCG + interferon |

| Epodyl |

| Gemcitabine |

| Interferon |

| Mitomycin |

| Thiotepa |

| Valrubicin |

BCG, bacillus Calmette-Guérin

Table 2 lists the characteristics of intravesical chemotherapy. Strategies for administering intravesical therapy include perioperative single-dose therapy, adjuvant therapy, and maintenance. Perioperative therapy is underutilized. A meta-analysis published by Sylvester and colleagues1 reviewed transurethral resection and an immediate perioperative dose of chemotherapy (epirubicin, mitomycin C, thiotepa, or pirarubicin) versus transurethral resection alone. Patients with a single tumor and a single dose of perioperative chemotherapy showed a 39% reduction in recurrence (P≤ .0001). Patients with multiple tumors showed a 56% reduction, but this was not statistically significant (P = .06) because of large confidence intervals. Most patients included in the analysis had low-risk tumors. About one-third of patients with single, low-risk tumors had recurrences with a single dose of therapy, and two-thirds of those with multiple tumors had recurrences, suggesting that a single dose is not adequate for patients with multiple tumors.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Intravesical Chemotherapy

| • Prevents early recurrence Percentage recurrence is reduced by approximately 12%–15% |

| • No long-term benefit |

| • Does not prevent disease progression |

| • Single perioperative instillation Most effective treatment strategy for patients at low risk |

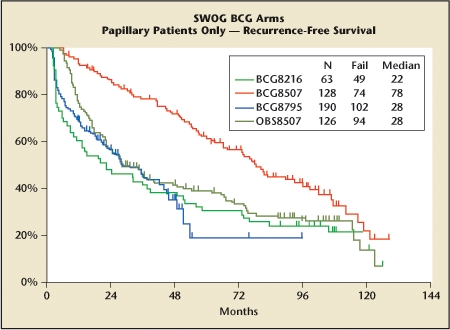

Table 3 lists the characteristics of BCG therapy. The pioneering work on adjuvant therapy with BCG in superficial bladder cancer through the 1980s raised the question of whether there is a role for maintenance therapy. The Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) trial published in 20002 examined an adjuvant regimen of BCG for 6 weeks versus BCG with an intensive maintenance strategy (Figure 1). Recurrence rates were significantly better in maintenance versus no-maintenance groups (P < .0001). Maintenance therapy, however, increased both overall and high-grade toxicity. The protocol at that time called for the continuation of full-dose therapies until toxicity was excessive. A better strategy is to decrease the dose of BCG when toxicity occurs so that patients can stay on treatment.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Therapy With BCG

| • Decreases recurrence |

| • Decreases progression |

| • Optimal delivery remains unclear 3-week re-inductions work |

| • Toxicity is moderate but acceptable Decrease the dose for toxicity |

| • Failure after 2 courses Alternative therapy indicated |

BCG, bacillus Calmette-Guérin

Figure 1.

Recurrence-free survival is better in patients receiving an intensive maintenance schedule than in those who received an induction course alone or less intensive maintenance. BCG, bacillus Calmette-Guérin; SWOG, Southwest Oncology Group. This figure was published in Journal of Urology, Volume 163, Lamm DL et al, “Maintenance bacillus Calmette- Guérin immunotherapy for recurrent TA, T1 and carcinoma in situ transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a randomized Southwest Oncology Group Study,” pages 1124–1129, Copyright American Urological Association, Inc., 2000.

Several meta-analyses have explored the efficacy of intravesical BCG and mitomycin C. The reliability of such analyses is limited because the included studies had different eligibility criteria, follow-up, and maintenance strategies. The addition of a maintenance strategy significantly improves outcome with BCG.3

A critical issue is defining treatment failure. The SWOG trial of BCG maintenance versus no maintenance included 116 patients with carcinoma in situ (CIS) randomized to induction only and 117 randomized to maintenance.2 Not unexpectedly, after 6 weeks of BCG, the 2 groups had essentially identical complete response (CR) rates. At the 6-month evaluation, investigators found an additional 11% of patients in the induction-only arm disease free, increasing the overall response rate from 57% to 68%. The maintenance group received another 3 weeks of BCG, and their response rate increased from 55% to 84% at 6 months, a rate that was significantly better than that seen in the induction only arm (P = .004). These data suggest that with CIS, BCG can result in a delayed response, but maintenance therapy substantially increases the rate of CR at 6 months.

BCG and Interferon

Prior to the advent of intravesical BCG, CIS progressed at a rate of about 7% per year.4 Maintenance BCG therapy can decrease the risk of progression.3 Intravesical chemotherapy for CIS provides CR rates up to 52%, but has lower response rates than BCG and has not been demonstrated to reduce progression risk.

Interest in interferon as an intravesical agent against bladder cancer developed in the 1980s. Results of early prospective series with interferon were disappointing, but patients tolerated regimens well, and interferon appeared to have some activity against CIS. Over the subsequent decade, sufficient experience with both agents had accumulated to suggest using them together as salvage therapy in patients with recurrence following intravesical BCG. In 2001, a preliminary trial of this approach reported that 63% of patients were disease free at 12 months and 53% were disease free at 24 months.5

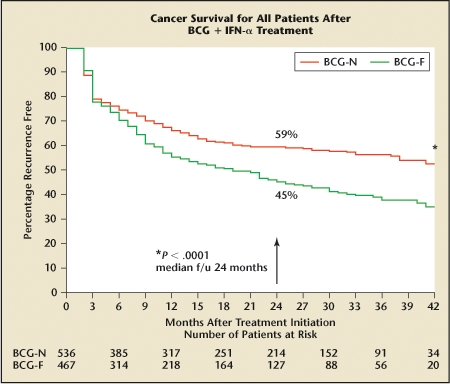

A large multicenter phase II trial to assess the combination of BCG and interferon enrolled about 1000 patients, 231 with CIS (Figure 2).6 Focusing on the CIS subgroup, approximately 95% of patients enrolled were older than 50 and 84% were male. Sixty-three percent had CIS alone; the remainder had CIS with papillary disease. Slightly less than half of the patients enrolled had never been treated with BCG. Ten percent were refractory to initial treatment, that is, their disease never disappeared completely. The rest whose previous treatment could be determined had recurrent disease after 1 or more courses of BCG. A small proportion (17%) had undergone BCG maintenance therapy, and 23% had undergone intravesical chemotherapy.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier recurrence rates in patients receiving intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) and interferon (IFN) characterized by whether they never received BCG (BCG-N) or had tumor recurrence after prior BCG (BCG-F). Reprinted from Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations, Volume 24, Joudi FN et al, “Final results from a national multicenter phase II trial of combination bacillus Calmette-Guérin plus interferon alpha-2B for reducing recurrence of superficial bladder cancer,” pages 344–348, Copyright 2006, with permission from Elsevier.

Investigators tailored both the induction regimen and maintenance program to prior history of intolerance to BCG. Interferon doses remained the same throughout. The course of active treatment was 18 months.

The BCG-naive group did very well. At 3 months, 76% had CR, and at 6 months about 70% remained disease free. About 60% of this group has remained disease free over roughly a 3-year follow-up. The study documented most of the recurrences in the first year. In contrast, those who had failed prior treatment were not as likely to have a CR and recurred more frequently and at a steady rate through the follow-up period. Further, those who entered the study after failing 2 or more BCG inductions were 2 to 3 times more likely to be nonresponders to BCG plus interferon (P ≤ .0001). Most of the difference between response in the BCG-naive and BCG-failure group is attributable to those who failed more than 1 cycle of BCG. Patients 70 years and older with both papillary and CIS seemed to be less responsive to BCG (P = .06), possibly because of an age-related decrease in immune responsiveness.7

Patients whose last relapse was more than a year from their last treatment had a CR to salvage treatment and long-term cancer-free survival similar to the treatment-naive group. It was better than those whose relapse was less than a year prior to study entry and significantly better than those who entered the study having been refractory to all prior treatment (P = .007). The only 2 significant predictors of poor response to salvage treatment were relapse within 1 year of treatment and nonresponse to 2 or more prior courses of BCG. Each conveyed about a 2-fold risk of poor response. Investigators offered patients who did not respond to the first course of BCG and interferon at the first 3-month assessment a second salvage course. This subgroup of retreated patients (who, by not responding to the initial study treatment, acquired 1 significant risk factor, ie, refractory disease), had about 30% response to a second course of BCG and interferon. Those who entered the study with 1 unfavorable factor (ie, being refractory to prior treatment, failing 2 or more prior courses of BCG, or relapsing within a year of prior treatment) and had, by nonresponse to the first study treatment, acquired a second unfavorable factor, had only 15% response.

Patients with CIS treated with intravesical BCG plus interferon have a 60% to 70% chance of a complete and durable response if they have never been treated with BCG or if they have failed only 1 prior induction or relapsed more than a year from induction. Patients who failed therapy immediately, failed in less than 12 months, or had 2 or more failures have an intermediate response to BCG and interferon. Those patients who failed BCG therapy more than once and within a short period fare poorly with this treatment and should consider an alternative therapy.

Newer Agents: Gemcitabine and Valrubicin

Gemcitabine

Gemcitabine (2′,2′-difluorodeoxycytidine) is a novel deoxycytidine analogue with a broad spectrum of antitumor activity. After transport into the cell, it is phosphorylated and incorporated into RNA and DNA, causing inhibition of cell growth and triggering apoptosis. Gemcitabine has shown efficacy when used systemically against advanced bladder cancers with single-agent responses in the range of 27% to 38%.

Gemcitabine appears to be relatively safe at concentrations of 40 mg/ mL (2000 mg/50 mL) and can be held in the bladder for up to 2 hours with minimal transient systemic absorption and low detectible levels of active metabolites. Early single intravesical instillation appears feasible, with the caveat of avoiding instillation if there is a bladder perforation.

In an open-label trial examining prophylactic use of intravesical gemcitabine, Bartoletti and colleagues8 followed 116 patients with noninvasive intermediate-risk and high-risk bladder cancer (Ta, T1, and CIS) given 2000 mg/50 mL in weekly instillations for 6 weeks. Based on the European Organization on the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) risk stratification, intermediate-risk patients had about a 26% recurrence rate (21/81 recurred, 2 progressed), and high-risk patients had about 77% (27/35 recurred, 5 progressed). This regimen worked better in lower-risk patients, patients with first-time tumors (P = .04), and patients who had no prior therapy (P = .03). Toxicity was relatively low. The most frequently reported toxicity was urgency (14/116, 12%), followed by dizziness and slight fever (6/116, 5%).

Gemcitabine has also been studied in BCG-refractory patients. In the Bartoletti study cited earlier, 18 out of 24 (75%) intermediate-risk and 7 out of 16 (43.7%) high-risk BCG-refractory patients achieved CR.8 Dalbagni and colleagues conducted a phase II study using a more intensive, twice-weekly administration in 30 BCG-refractory patients.9 With median follow- up of 19 months (range, 0-35), 15 of the 30 (50%) had an initial CR. However, 12 out of 15 (80%) had recurrence, with a median recurrence-free survival of 3.6 months. Eleven of the 30 (37%) eventually went on to cystectomy.

Valrubicin

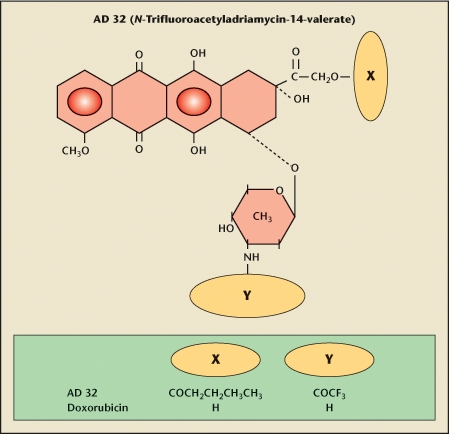

Valrubicin is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for intravesical treatment of BCG-refractory CIS of the bladder. Valrubicin (AD 32, Valstar® [Indevus Pharmaceuticals, Lexington, MA]) is N-trifluoroacetyladriamycin- 14-valerate, a lipid-soluble anthracycline semisynthetic analogue of doxorubicin. Substitutions of the 14-carbon side chain of the valerate ester and the trifluoroacetyl group on the 3-amino group render the molecule highly lipophilic and poorly water soluble (Figure 3). Valrubicin lacks the high level of preferential binding to the negatively charged cell membrane of hydrophilic agents like doxorubicin. This is the source of the decreased toxicity of valrubicin, and conversely, the source of the cardiotoxicity and contact toxicity of doxorubicin. Unlike doxorubicin, valrubicin rapidly traverses cell membranes and accumulates in the cytoplasm, where it interferes with the incorporation of nucleosides into the nucleic acids, resulting in chromosomal damage and cell-cycle arrest in G2.

Figure 3.

Valrubicin (AD32, Valstar) is N-trifluoroacetyladriamycin-14-valerate. It is a lipid-soluble anthracycline semisynthetic analogue of doxorubicin. The molecule is highly lipophilic and not very water soluble because of substitutions of the 14-carbon side chain of the valerate ester and the trifluoroacetyl group on the 3-amino group. Accordingly, valrubicin does not bind preferentially to the negatively charged cell membrane of hydrophilic agents like doxorubicin. This is the source of the decreased toxicity of valrubicin, and conversely, the source of the cardiotoxicity and contact toxicity of doxorubicin. Unlike doxorubicin, valrubicin rapidly traverses cell membranes and accumulates in the cytoplasm, where it interferes with the incorporation of nucleosides into the nucleic acids, resulting in chromosomal damage and cell-cycle arrest in G2.

The principal metabolites of valrubicin, N-trifluoroacetyldoxorubicin and N-trifluoroacetyldoxorubicinol, both inhibit topoisomerase II, thus also inhibiting DNA synthesis. The effects of valrubicin on DNA and RNA synthesis inhibition are not a function of the conversion of valrubicin into doxorubicin. Therefore, there is no concern about cross-contamination from doxorubicin.

Intravesical administration in rodents showed minimal metabolism; 91% of the valrubicin was recovered upon draining the bladder. Low levels of drug and metabolites were detectable in the plasma, but there was no systemic toxicity, even at the maximal doses based on bladder volume and solubility, nor were standard dermal irritation models reactive.

The 800-mg intravesical dose results in significant bladder wall penetration at levels that exceed the concentrations needed to achieve 90% cell kill in human bladder cancer. Metabolism was negligible in the first 2 hours, which is the conventional retention period for intravesical therapy. Voiding of the instillate resulted in almost complete excretion of the drug. The mean percentage recovery of valrubicin and total anthracycline levels were 98.6% and 99%, respectively.

A phase I/II pilot study of intravesical valrubicin determined that 900 mg was the maximum tolerable dose, although 800 mg was used in subsequent studies. Serum levels of unmetabolized valrubicin were low and transient. A study conducted at the University of Tennessee examined tissue penetration of valrubicin in surgical specimens from 6 patients to whom the drug was given immediately before cystectomy (data on file, Anthra Pharmaceuticals, Princeton, NJ). The dose dwelled in the bladder for about 30 minutes during surgical mobilization. After surgery, tissue penetration of the drug was assayed and found at depths of 1250 µm or more.

A multi-institutional study of intravesical valrubicin enrolled 90 patients with CIS who were refractory or recurrent after at least 1 6-week course of BCG.10 Almost all (99%) had at least 2 prior intravesical therapies, and 60% had 3 or more. Nineteen patients (21%) had a CR, including 7 (10% of the total study group) who remained disease free with a median follow-up of 30 months. Fourteen had noninvasive recurrences that were easily managed. At least 2 patients have not had to undergo cystectomy over a follow-up period of 10 years (R. E. Greenberg, unpublished data, 2008). Forty-four patients (56%; 40 nonresponders and 4 responders) eventually underwent cystectomy. Of these, about 15% had extravesical or node-positive disease. Four patients died of their cancer. None of these individuals had experienced CR, and none had gone on to cystectomy. None of the patients who started the study with a pathologic diagnosis of T1 grade 3 with CIS had a CR.

The side effects profile in this study was similar to the earlier work. The most common was local bladder irritation. About 90% of patients had some frequency, urgency, or dysuria on at least 1 occasion over the course of therapy. Most episodes were mild, and only 3 of the patients were unable to receive the 6 scheduled doses. Among other reported adverse events, the only relatively common event was urinary tract infection, reported by 18% of patients.

A phase I study of valrubicin in the perioperative period treated 22 patients with a single, well-tolerated dose. Systemic exposure appeared to be dependent not on the dose of the medication given, but on the extent of the transurethral resection (TUR), that is, whether or not there was a perforation.11 This agent may be one that can be given in the perioperative period.

In patients with BCG-refractory CIS, delaying cystectomy for 3 months to assess the effect of valrubicin does not appear to pose an undue risk. However, delaying cystectomy for more than 3 months after treatment failure may contribute to disease progression and reduce survival among those with high-risk noninvasive tumors.12,13 Immediate cystectomy is recommended when valrubicin treatment fails among those patients with high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

Surgical Management of Superficial Bladder Cancer

Patients whose tumors invade the muscularis mucosa have substantial differences in 5-year survival compared to those whose T1 tumors remain superficial to this landmark. Options for patients with high-grade T1 (T1G3) tumors include transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBT) alone (over 50% progression) and TURBT followed by intravesical therapy (30% progression). Radical cystectomy is also advocated but carries a 30% reported morbidity and 2% mortality. The dilemma is that cystectomy for all T1G3 tumors overtreats about 50% of patients.

Identifying Candidates for Cystectomy

Risk stratification is important and includes restaging TUR with examination under anesthesia, careful review of clinical and pathologic features, and imaging as appropriate. Restaging TUR 2 to 6 weeks after the initial diagnosis is important for T1 tumors.14 Dutta and colleagues15 found that 2 out of 3 tumors would be understaged if no muscle were present. This improves to 1 in 3 with muscle tissue present on the slide.

Staging is important and mapping biopsies can detect occult disease. However, performing biopsies in normal- looking urothelium in the presence of Ta or T1 bladder cancer is not usually informative, as about 90% of the patients show no abnormalities.16 Herr and Donat17 conducted a retrospective review of 710 patients with superficial transitional cell carcinoma (TCC). Of the 47% of patients with T1 specimens restaged as T0, 14% progressed within 5 years. Of the 20% with T1 specimens restaged as T1G3, 76% progressed within 5 years, with a median progression of 15 months.

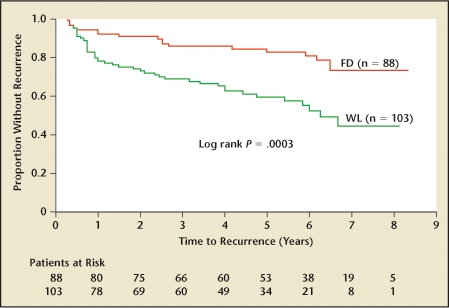

In 1994, Kriegmair and colleagues18 reported improved identification of urothelial tumor tissue using 5- aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA). In 2007, Denzinger and colleagues19 reported 8-year follow-up results on a prospective trial examining the impact on recurrence-free survival of 5-ALA fluorescence versus conventional white light (Figure 4). Residual tumors were found in 25% of patients with the white light resection versus 4.5% of patients who had the fluorescent light resection (P < .0001). Recurrence-free survival at 8 years was reported at 45% in the white light group versus 71% in the 5-ALA fluorescence group (P = .0003). Patients enrolled in the study were generally low risk; only 12% of the study patients had T1G3 cancer. Time to recurrence was significantly longer among those undergoing TUR with 5-ALA fluorescence (P = .04 by log rank).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of recurrence-free survival in patients resected with fluorescence (FD) or white light (WL) cystoscopy. Reprinted from Urology, Volume 69, Denzinger S et al, “Clinically relevant reduction in risk of recurrence of superficial bladder cancer using 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced fluorescence diagnosis: 8-year results of prospective randomized study,” pages 675–679, Copyright 2007, with permission from Elsevier.

Prognosis of Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer

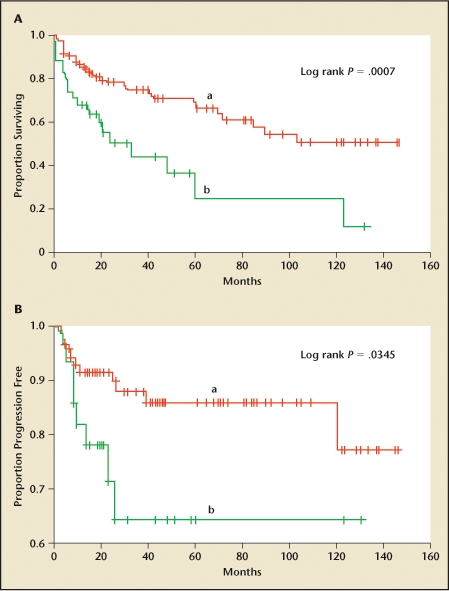

Clinical risk factors for progression and poor outcome include early recurrence, multiplicity of tumors, and response to BCG. As many as 80% of high-risk patients who are not cancer free at 3 months post-BCG can be expected to progress.20 Lymphovascular invasion is a pathologic risk factor.21 The disease-specific hazard ratio for survival has been reported as much as 15.8 times higher (p = .001) in patients without this finding than in patients with it (Figure 5).22 Tumor extent and size over 3 cm, concomitant CIS, prostatic involvement,23 and depth of lamina propria invasion appear to be critical.24

Figure 5.

Overall (A) and progression-free (B) survival of patients without (a) or with (b) vascular, lymphatic, or perineural invasion. Reprinted from Urology, Volume 65, Hong SK et al, “Do vascular, lymphatic, and perineural invasion have prognostic implications for bladder cancer after radical cystectomy?” pages 697–702, Copyright 2005, with permission from Elsevier.

A prediction model based on the combined analysis of nearly 2600 patients with Ta, T1, Tis from 7 EORTC trials was developed in 2006.23 This scoring system is based on the number of tumors, tumor size, prior recurrence rate, T stage, CIS, and grade. Those with the highest scores were most likely to recur early and most likely to progress most rapidly.

The role of tumor markers in prognosis of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer remains controversial. Attempting to use p53 overexpression as an independent predictor of disease progression has had mixed results. In 2005, the International Consensus Panel on bladder tumor markers concluded that although certain markers, particularly p53 and ki67, are promising, the data are unclear and there is insufficient standardization of these tests, making them currently unsuitable for patient care.25

The arguments for cystectomy are substantial when faced with an early but identifiably dangerous tumor. Of 1054 patients undergoing radical cystectomy for transitional cell cancer (TCC) of the bladder between July 1971 and December 1997 at the University of Southern California, 40% with T1G3 were upstaged on the final pathology, and 10% to 15% had positive lymph nodes. Recurrence-free survival for T1 and T2 disease at 5 and 10 years was not greatly different.26 In contrast, the experience at 3 academic medical centers in the United States found disease-specific survival to be considerably better for those who had radical cystectomy for T1 rather than T2 disease.27

The timing of cystectomy is important. Patients who receive early cystectomy (< 2 years after TUR) for recurrent high-risk non-muscle-invasive TCC have a significantly better 15-year survival than those who undergo late cystectomy (> 2 years).28 The effect was most prominent in those with T2 disease but was evident overall and among those with non-muscle-invasive disease. Mahmud and colleagues29 found that patients whose cystectomies were delayed more than 12 weeks were at 20% greater risk of dying (95% confidence interval, 1.0- 1.5; P = .051) than those who had cystectomies earlier.

Lymph node dissection appears to be a critical element in cystectomy. Patients with no positive nodes show a clear survival advantage over those with at least 1 positive node (P < .001).30 In the subset of patients with positive nodes, those with more than 15 nodes removed show a trend for improved outcome (P = .21).30

Patient Considerations

Radical cystectomy appears to be fairly well tolerated, even among elderly (median age, > 75 years) patients. However, those older patients with Karnofsky performance status of 80 have almost twice the risk of sudden death within 5 years of cystectomy compared to those with a Karnofsky score of 90 or greater.31 The impact of body mass on radical cystectomy is significant; body mass index (BMI) higher than 25 is positively correlated with estimated blood loss, operative time, and complication rates.32 However, BMI in patients at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York who had undergone radical or partial cystectomy was not associated with disease-specific survival as a continuous (P = .17) or categorical (P = .51) variable.33 Patients at the Medical University of South Carolina (Charleston, SC) with BMI of less than 20, who underwent cystectomy from 2001 to 2004, did poorly, possibly reflecting cachexia in very ill patients at the time of surgery (T. E. Keane, unpublished data, 2008).

Radiation has been used as an alternative. A randomized study evaluated the role of radiation therapy in 2 groups of patients with T1, grade 3 bladder cancer.34 In group 1, 77 patients were randomized to observation after primary resection or radiation therapy. A second group of 133 patients were randomized to intravesical therapy or radiation therapy. For both overall and progression-free survival, intravesical therapy appears somewhat better than radiation, although not statistically significant (P = .2). In the radiation versus observation alone group, overall survival is essentially identical (P = .95), as is progression- free-survival (P = .6). This study provides evidence that radiotherapy does not prevent or delay the incidence of progression to muscle invasive disease.34

Conclusions

Early (non-muscle-invasive) bladder cancer affects approximately 500,000 people in the United States. Most will experience recurrent disease and have a smaller but significant risk of progression and death. Effective therapy requires reliable tumor staging. Intravesical BCG remains the gold standard both for primary induction and maintenance, but patients who prove refractory to BCG or who have tumor recurrence after 1 or more inductions need careful assessment and consideration of appropriate salvage therapies. At this time, intravesical chemotherapy regimens are suboptimal, though the addition of interferon to primary BCG induction or to salvage regimens has been successful in selected patients. Among those with CIS, valrubicin is the only FDA-approved agent for salvage therapy use in patients who have failed BCG therapy. Response rates in heavily pretreated patients are approximately 20%. Further research is needed to identify more effective salvage therapies for patients with BCG-refractory disease. At the present time, once refractory disease has been identified, prompt cystectomy appears to convey the best long-term disease-free survival.

Main Points.

Early (non-muscle-invasive) bladder cancer affects approximately 500,000 people in the United States. Most will experience recurrent disease and have a smaller but significant risk of progression and death.

Intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is the gold standard for primary induction and maintenance, but patients refractory to BCG or who have tumor recurrence need assessment for appropriate salvage therapies.

Intravesical gemcitabine is safe, but its usefulness for BCG-refractory patients is unclear.

For patients with carcinoma in situ who have failed BCG therapy, valrubicin is the only US Food and Drug Administration- approved agent for salvage therapy.

Once refractory disease has been identified, prompt cystectomy appears to convey the best long-term disease-free survival.

References

- 1.Sylvester RJ, Oosterlinck W, van der Meijden AP. A single immediate postoperative instillation of chemotherapy decreases the risk of recurrence in patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of published results of randomized clinical trials. J Urol. 2004;171:2186–2190. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000125486.92260.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamm DL, Blumenstein BA, Crissman JD, et al. Maintenance bacillus Calmette-Guérin immunotherapy for recurrent TA, T1 and carcinoma in situ transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a randomized Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Urol. 2000;163:1124–1129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohle A, Bock PR. Intravesical bacille Calmette- Guérin versus mitomycin C in superficial bladder cancer: formal meta-analysis of comparative studies on tumor progression. Urology. 2004;63:682–686. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zincke H, Utz DC, Farrow GM. Review of Mayo Clinic experience with carcinoma in situ. Urology. 1985;26:39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Donnell MA, Krohn J, DeWolf WC. Salvage intravesical therapy with interferon-alpha 2b plus low dose bacillus Calmette-Guérin is effective in patients with superficial bladder cancer in whom bacillus Calmette-Guérin alone previously failed. J Urol. 2001;166:1300–1304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joudi FN, Smith BJ, O’Donnell MA. Final results from a national multicenter phase II trial of combination bacillus Calmette-Guérin plus interferon alpha-2B for reducing recurrence of superficial bladder cancer. Urol Oncol. 2006;24:344–348. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joudi FN, Smith BJ, O’Donnell MA, Konety BR. The impact of age on the response of patients with superficial bladder cancer to intravesical immunotherapy. J Urol. 2006;175:1634–1639. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00973-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartoletti R, Cai T, Gacci M, et al. Intravesical gemcitabine therapy for superficial transitional cell carcinoma: results of a phase II prospective multicenter study. Urology. 2005;66:726–731. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalbagni G, Russo P, Bochner B, et al. Phase II trial of intravesical gemcitabine in bacille Calmette- Guérin-refractory transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2729–2734. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinberg G, Bahnson R, Brosman S, et al. Efficacy and safety of valrubicin for the treatment of bacillus Calmette-Guérin refractory carcinoma in situ of the bladder. The Valrubicin Study Group. J Urol. 2000;163:761–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patterson AL, Greenberg RE, Weems L, et al. Pilot study of the tolerability and toxicity of intravesical valrubicin immediately after transurethral resection of superficial bladder cancer. Urology. 2000;56:232–235. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00654-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang SS, Hassan JM, Cookson MS, et al. Delaying radical cystectomy for muscle invasive bladder cancer results in worse pathological stage. J Urol. 2003;170:1085–1087. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000086828.26001.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee CT, Madii R, Daignault S, et al. Cystectomy delay more than 3 months from initial bladder cancer diagnosis results in decreased disease specific and overall survival. J Urol. 2006;175:1262–1267. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00644-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herr HW. Restaging transurethral resection of high risk superficial bladder cancer improves the initial response to bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy. J Urol. 2005;174:2134–2137. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000181799.81119.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dutta SC, Smith JA , Jr, Shappell SB, et al. Clinical under staging of high risk nonmuscle invasive urothelial carcinoma treated with radical cystectomy. J Urol. 2001;166:490–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Meijden A, Oosterlinck W, Brausi M, et al. Significance of bladder biopsies in Ta,T1 bladder tumors: a report from the EORTC Genito-Urinary Tract Cancer Cooperative Group. EORTC-GU Group Superficial Bladder Committee. Eur Urol. 1999;35:267–271. doi: 10.1159/000019859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herr HW, Donat SM. A re-staging transurethral resection predicts early progression of superficial bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2006;97:1194–1198. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kriegmair M, Baumgartner R, Riesenberg R, et al. Photodynamic diagnosis following topical application of delta-aminolevulinic acid in a rat bladder tumor model. Investig Urol (Berl) 1994;5:85–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denzinger S, Burger M, Walter B, et al. Clinically relevant reduction in risk of recurrence of superficial bladder cancer using 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced fluorescence diagnosis: 8-year results of prospective randomized study. Urology. 2007;69:675–679. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solsona E, Iborra I, Dumont R, et al. The 3-month clinical response to intravesical therapy as a predictive factor for progression in patients with high risk superficial bladder cancer. J Urol. 2000;164:685–689. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200009010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shariat SF, Karakiewicz PI, Palapattu GS, et al. Nomograms provide improved accuracy for predicting survival after radical cystectomy. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6663–6676. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong SK, Kwak C, Jeon HG, et al. Do vascular, lymphatic, and perineural invasion have prognostic implications for bladder cancer after radical cystectomy? Urology. 2005;65:697–702. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sylvester RJ, van der Meijden AP, Oosterlinck W, et al. Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: a combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials. Eur Urol. 2006;49:466–475. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smits G, Schaafsma E, Kiemeney L, et al. Microstaging of pT1 transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: identification of subgroups with distinct risks of progression. Urology. 1998;52:1009–1013. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00374-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Habuchi T, Marberger M, Droller MJ, et al. Prognostic markers for bladder cancer: International Consensus Panel on bladder tumor markers. Urology. 2005;66:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein JP, Lieskovsky G, Cote R, et al. Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer: long-term results in 1,054 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:666–675. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shariat SF, Karakiewicz PI, Palapattu GS, et al. Outcomes of radical cystectomy for transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a contemporary series from the Bladder Cancer Research Consortium. J Urol. 2006;176:2414–2422. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herr HW, Sogani PC. Does early cystectomy improve the survival of patients with high risk superficial bladder tumors? J Urol. 2001;166:1296–1299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahmud SM, Fong B, Fahmy N, et al. Effect of preoperative delay on survival in patients with bladder cancer undergoing cystectomy in Quebec: a population based study. J Urol. 2006;175:78–83. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stein JP. The role of lymphadenectomy in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2007;9:213–221. doi: 10.1007/s11912-007-0024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weizer AZ, Joshi D, Daignault S, et al. Performance status is a predictor of overall survival of elderly patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer. J Urol. 2007;177:1287–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee CT, Dunn RL, Chen BT, et al. Impact of body mass index on radical cystectomy. J Urol. 2004;172:1281–1285. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000138785.48347.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hafron J, Mitra N, Dalbagni G, et al. Does body mass index affect survival of patients undergoing radical or partial cystectomy for bladder cancer? J Urol. 2005;173:1513–1517. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154352.54965.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harland SJ, Kynaston H, Grigor K, et al. A randomized trial of radical radiotherapy for the management of pT1G3 NXM0 transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Urol. 2007;178:807–813. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]