Abstract

Successful treatment of human tuberculosis requires 6–9 months' therapy with multiple antibiotics. Incomplete clearance of tubercle bacilli frequently results in disease relapse, presumably as a result of reactivation of persistent drug-tolerant Mycobacterium tuberculosis cells, although the nature and location of these persisters are not known. In other pathogens, antibiotic tolerance is often associated with the formation of biofilms – organized communities of surface-attached cells – but physiologically and genetically defined M. tuberculosis biofilms have not been described. Here, we show that M. tuberculosis forms biofilms with specific environmental and genetic requirements distinct from those for planktonic growth, which contain an extracellular matrix rich in free mycolic acids, and harbour an important drug-tolerant population that persist despite exposure to high levels of antibiotics.

Introduction

Human tuberculosis infections typically require treatment with multiple antibiotics for 6–9 months to avoid re-emergence of the disease (Hopewell et al., 2006). The reasons why such extended treatments are required are not completely understood, but as antibiotics effectively kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis during the first 14 days of treatment (Jindani et al., 2003; Sirgel et al., 2005), a subpopulation of drug-tolerant cells that are either inaccessible or non-responsive to small molecules must persist (Wallis et al., 1999). Current models of M. tuberculosis persistence typically invoke the presence of dormant populations of non-growing cells that reactivate upon host immunosuppression (Wayne and Sohaskey, 2001). While in vitro data indicate that active growth is important for susceptibility of M. tuberculosis to many front-line antibiotics (Xie et al., 2005), mutant strains that are defective in in vitro dormancy do not appear defective in in vivo persistence (Parish et al., 2003; Voskuil et al., 2003; Rustad et al., 2008).

In other infectious diseases, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis and Escherichia coli in urinary tract infections, biofilms provide an important reservoir of cells that can repopulate colonized sites upon removal of drug treatment (Singh et al., 2000; Anderson et al., 2004). As a correlation between biofilm formation and bacterial persistence has been proposed (Costerton et al., 1999; Balaban et al., 2004; Roberts and Stewart, 2005), the question arises as to whether M. tuberculosis can form drug-tolerant biofilms. If so, it raises the possibility of M. tuberculosis biofilm formation as a potential new target for drugs that facilitate the use of current anti-tuberculosis antibiotics administered in ultra-short regimens. In a surfactant-free liquid medium culture, M. tuberculosis can form organized pellicle-like structures on the air–media interface (Darzins and Fahr, 1956), although the growth characteristics and persistence of the pathogen in these multicellular communities have not been closely scrutinized.

Cellular and molecular studies on biofilms of several mycobacterial species have been performed (Schulze-Robbecke and Fischeder, 1989; Hall-Stoodley and Lappin-Scott, 1998; Marsollier et al., 2005; Hall-Stoodley et al., 2006). Mycobacterium smegmatis forms biofilms both on PVC surfaces and on liquid–air interfaces, and exhibits sliding motility on agar surface; the genetic requirements for biofilm formation and sliding motility are similar (Recht and Kolter, 2001; Ojha et al., 2005; Ojha and Hatfull, 2007). M. smegmatis biofilm formation requires a low level of supplemental iron that is acquired by the exochelin uptake system (Ojha and Hatfull, 2007) and is genetically distinct from planktonic growth (Recht and Kolter, 2001; Ojha et al., 2005). Unlike most other biofilm-forming bacteria, M. smegmatis biofilms contain a lipid-rich extracellular matrix and the FAS-II system responsible for the synthesis of mycolic acids is implicated in this process (Ojha et al., 2005). In particular, mutations in both inhA and kasB give rise to biofilm defects, and GroEL1 – a dedicated chaperone for biofilm formation – specifically interacts with components of the FAS-II system. Mycolic acid synthesis is therefore closely associated with M. smegmatis biofilm formation and this is of particular note as the front-line anti-tuberculosis drug isoniazid acts on the essential InhA enzyme in mycolate synthesis (Vilcheze et al., 2006).

Here, we investigate the conditions that support growth of M. tuberculosis biofilms and demonstrate that biofilm formation is genetically and physiologically distinct from planktonic growth of M. tuberculosis. These biofilms are unusual in that the tubercle bacilli are embedded in a lipid-rich extracellular matrix containing free methoxy mycolic acids. Moreover, we show that M. tuberculosis biofilms are drug-tolerant and harbour persistent cells that survive high concentrations of anti-tuberculosis antibiotics.

Results and discussion

Growth of M. tuberculosis biofilms

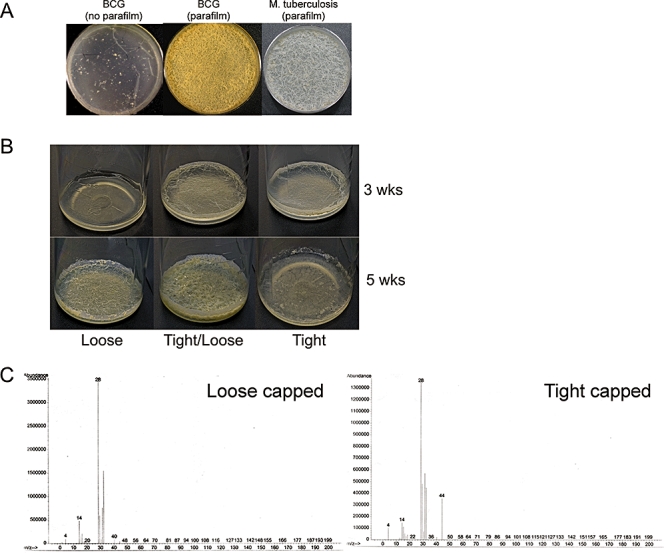

Biofilm growth of non-tuberculosis mycobacteria is dependent on growth conditions and medium. M. tuberculosis does not grow in the modified M63 medium that supports formation of M. smegmatis biofilms at liquid–air interfaces (Recht et al., 2000; Branda et al., 2005; A.K. Ojha and G.F. Hatfull, unpubl. obs.) and, in an established medium, such as Sauton's, we found that both M. tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis BCG form a thin film in a Petri dish without the thick textured reticulation that is typical of mature biofilms of M. smegmatis and other mycobacteria (Fig. 1A). However, serendipitously we observed that when using the same Sauton's medium, the sealing of the dishes with parafilm supports growth of lush mature biofilms by both M. bovis and M. tuberculosis (Fig. 1A) after 5 weeks of incubation, which are visually indistinguishable from those of M. smegmatis.

Fig. 1.

Growth of M. tuberculosis biofilms.

A. M. bovis BCG or M. tuberculosis H37Rv was cultured in a Petri dish containing Sauton's medium for 5 weeks with either a standard loose-fitting lid or with a sealed parafilm covering.

B. Bottle assay for the growth of M. tuberculosis mc27000 biofilms. Bottle caps were kept either loose or tight for 5 weeks, or tight for the first 3 weeks and loosened for the last 2 weeks, as indicated.

C. Gases present in either loosely capped or tightly capped bottles (as indicated) were examined by GC/MS. CO2 (44 amu) accumulates in the tightly capped bottles.

We propose that there are two aspects of these parafilm-covered dishes that are important for biofilm growth and maturation. First, as parafilm is likely to restrict the loss of gases and volatile substances by diffusion, we suggest that these volatile agents may either mediate signalling events or satisfy specific metabolic requirements needed for biofilm maturation. Second, because biofilm maturation of other mycobacteria requires continued bacterial growth, it seems likely that the property of parafilm to permit diffusion of oxygen is an important parameter. We note that this underscores a significant difference with models of mycobacterial dormancy which require a micro-anaerobic environment (Wayne and Sohaskey, 2001).

We have reproduced M. tuberculosis biofilm growth using polystyrene bottles, which provide more robust and reproducible conditions. In this format, the medium occupies approximately 10% of the bottle volume and is inoculated by adding cells from a saturated planktonic culture at a 1:100 dilution. If the bottle is tight-capped, then after 3 weeks of incubation, attachment of M. tuberculosis cells to the sides of the polystyrene bottles and some maturation is observed, but there is little change to the biofilm appearance over the subsequent 2 weeks of incubation (Fig. 1B). In contrast, if the bottle caps are kept loosely associated, then biofilm formation is noticeably retarded, and little attachment or maturation is observed after 3 weeks' incubation, and is only apparent after 5 weeks of incubation (Fig. 1B). We find that optimal biofilm formation is observed by maintaining the bottle tightly capped for 3 weeks, and then loosening the caps for the last 2 weeks (Fig. 1B). This is a simple and robust biofilm model that – even though the extent and timing of biofilm development may vary with bottles and caps – enables analysis of gas accumulation under these conditions.

To identify putative gases and volatile substances that are required for biofilm formation, we analysed the gases by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS), comparing those in the head-space of a tight-capped bottle used to grow M. tuberculosis biofilms with those in a loose-capped bottle (Fig. 1C). This analysis showed accumulation of CO2 (44 amu) and lower abundance of oxygen (32 amu) in the tight-capped bottle (Fig. 1C). Other volatile substances may be present, but at concentrations too low for detection by GC/MS. A critical role for CO2 seems implausible as we would expect it to diffuse through a parafilm cover (Fig. 1A).

Role of carbon dioxide in M. tuberculosis biofilm formation

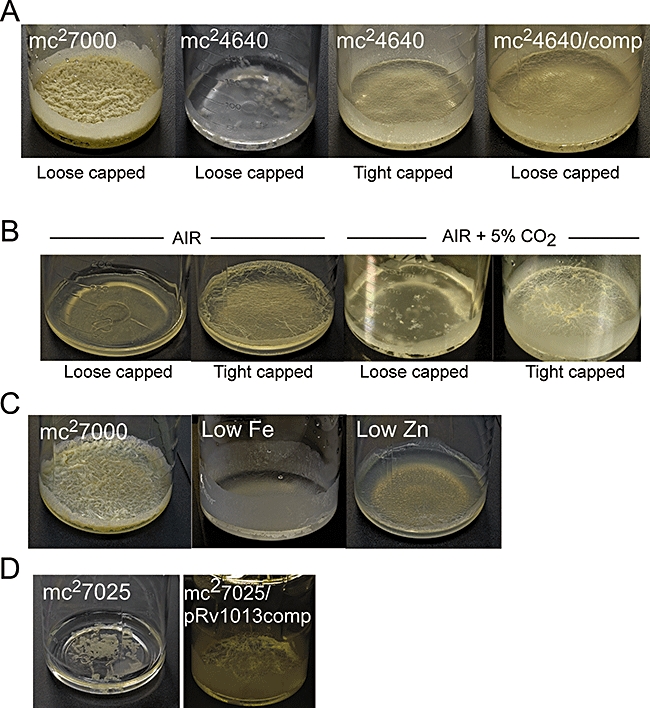

Phenotypic analysis of mutants attenuated in the ability to produce CO2 suggests that CO2 availability plays a rolein M. tuberculosis biofilm formation. For example, a M. tuberculosis mutant (mc24640) that lacks the genes for 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (encoded by Rv2454c and Rv2455c; A. D. Baughn and W. R. Jacobs, unpubl. data) and requires exogenous CO2 for growth on solid medium is defective in biofilm formation (Fig. 2A). Biofilm formation by this strain was partially restored either by precluding gas exchange (tightening the cap of the culture vessel) during the first 3 weeks of incubation, or by complementing the genetic defect by integration of the wild-type Rv2454c-Rv2455clocus (Fig. 2A). We recognize that this mutant is likely to have substantial alterations in its overall carbon metabolism and, owing to the presence of other similarly prominent metabolic sources of CO2, namely isocitrate dehydrogenase and pyruvate dehydrogenase, it is possible that CO2 accessibility is not the sole factor necessary to promote M. tuberculosis biofilms. Yet, it is important to note that biofilm formation of the wild-type strain was stimulated by supplementation with 5% CO2, although to a far lesser degree than sealing of the culture vessel (Fig. 2B). Overall, these data suggest that changes in the composition of the gaseous space other than CO2 accumulation – such as decreasing oxygen tension or increasing concentration of organic volatile molecules – stimulate biofilm development. We have not been able to identify these by GC/MS and the nature of the stimulant remains elusive.

Fig. 2.

Environmental and genetic requirements for M. tuberculosis biofilms.

A. M. tuberculosis mc24640, a mutant deleted for genes encoding 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase, requires CO2 for colony formation on solid media and is defective in biofilm formation. Tightly capping the bottle for the first 3 weeks or complementing with genes Rv2454c-Rv2455c (mc24640/comp) partially restores biofilm formation; all cultures were grown for 5 weeks.

B. Exogenous CO2 (5%) is not sufficient to support full growth of M. tuberculosis biofilms. Biofilms were grown in air or air supplemented with 5% CO2 as shown.

C. Low iron (2 μM) and low zinc (none added) inhibit biofilm development with no effect on planktonic growth (see Fig. S1).

D. M. tuberculosis strain mc27025 defective in gene Rv1013 is strongly defective in biofilm formation, and complemented by plasmid pRv1013comp that contains the Rv1013 gene.

Requirement of iron and zinc for M. tuberculosis biofilm maturation

Iron plays a central role in biofilm formation (Banin et al., 2005; Ojha and Hatfull, 2007) and we therefore examined the iron dependence of M. tuberculosis biofilms. Reducing the normal amount of iron (to 2 μM) has no effect on planktonic growth (Fig. S1) but severely retards biofilm growth (Fig. 2C). The effect is most apparent on the maturation stages, and bacteria remain competent to attach to the sides of the polystyrene bottles (Fig. 2C). The requirement of iron specifically for late biofilm development rather than attachment is similar to that reported for M. smegmatis, although we note that 2 μM iron is sufficient to support full M. smegmatis biofilm growth (Ojha and Hatfull, 2007). Removal of the zinc supplement also interrupts M. tuberculosis biofilm development (Fig. 2C) without affecting planktonic growth (Fig. S1); interestingly, both iron and zinc are important metal cofactors for enzymes involved in CO2 generation and capture as well as synthesis of mycolic acids. We note, for example, that carbonic anhydrase requires zinc for generating carbonate from CO2, which is utilized by carboxybiotin-dependent acetyl CoA carboxylases to make the malonyl-CoA and methylmalonyl CoA precursors for mycolic acid biosynthesis; whereas FeS cluster proteins are required for synthesis of the biotin cofactor.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis biofilm growth is genetically distinct from planktonic growth

To determine if biofilm formation can be genetically differentiated from planktonic growth, we isolated mutants from a transposon insertion library of M. tuberculosis that have reduced biofilm growth (D. Sambandan and W. R. Jacobs Jr, unpublished); one such mutant, mc27025, is strongly defective (Fig. 2D), while growing normally in planktonic culture (Fig. S1). The biofilm defect is severe and, even under optimal conditions, there is a nearly complete loss of liquid surface growth, although there is still visible attachment to the surfaces of the polystyrene bottles. The transposon insertion maps to gene Rv1013 encoding a putative acyl-CoA synthase and, although the genes and its product are not well-characterized, it is reported to be upregulated about twofold after 24 h starvation (Betts et al., 2002); complementation with Rv1013 restores the biofilm phenotype (Fig. 2D). A second mutant – defective in helY – shows a similar biofilm defective phenotype (data not shown). Clearly, biofilm formation is a genetically distinct state from planktonic growth or growth on solid agar medium.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis biofilms contain abundant extractable free mycolic acids

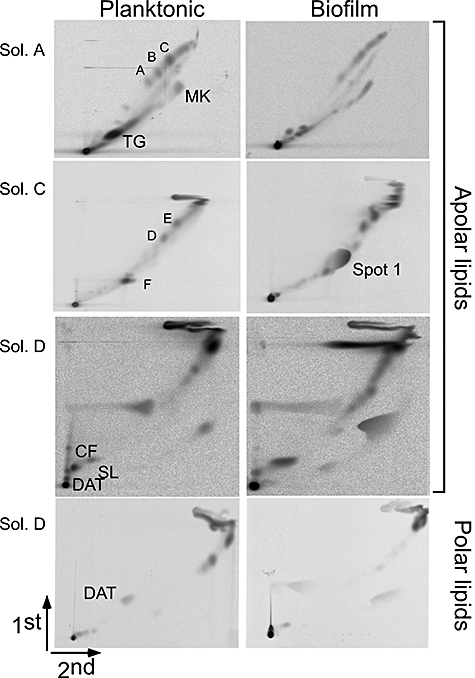

Mycobacterium tuberculosis biofilms are unusual in that they contain novel lipids which are most likely derivatives of mycolic acids (Ojha et al., 2005). Elevated level of these lipids is closely associated with the late stages of biofilm maturation and a ΔgroEL1 mutant defective in maturation fails to make these lipids (Ojha et al., 2005). We therefore examined whether M. tuberculosis biofilms contain lipids that are not present in planktonic cultures. Initially, we extracted both apolar and polar lipids from planktonic and biofilm cultures and compared them by two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography (TLC) as described previously (Dobson et al., 1985) (Fig. 3). Overall, the lipid profiles for the two samples are very similar, with two notable exceptions. First, triacylglyceride (TG) is present in planktonically grown cells as expected, but is present at a reduced level in the biofilm sample (Fig. 3A); presumably, TG is being used as an intracellular carbon source in biofilm growth, as has been shown for starvation conditions (Deb et al., 2006). Interestingly, extraction of apolar lipids and analysis by TLC with solvent C (see Experimental procedures) show the presence of a fatty acid (labelled Spot 1 in Fig. 3) that is much more abundant in the biofilm culture than in planktonic cells.

Fig. 3.

Lipid analysis of planktonically grown cells and biofilms of M. tuberculosis. Total apolar and polar lipids from planktonic and biofilm cultures of M. tuberculosis mc27000 resolved on 2D-TLC are solvent systems as described in the Experimental procedures (solvent A, Sol. A; solvent C, Sol. C; solvent D, Sol. D). Samples were labelled with 14C-acetate and equal amounts of total radioactivity were examined. The lipids are annotated as previously described (Besra, 1998): A–C, phthiocerol dimycoserosate family; MK, menaquinone; D and E, apolar mycolipenates of trehalose; F, free fatty acid; CF, cord factor; DAT, 2,3,-di-O-acyltrehaloses; SL, sulphatides. Spot 1 which is induced in biofilms is also marked.

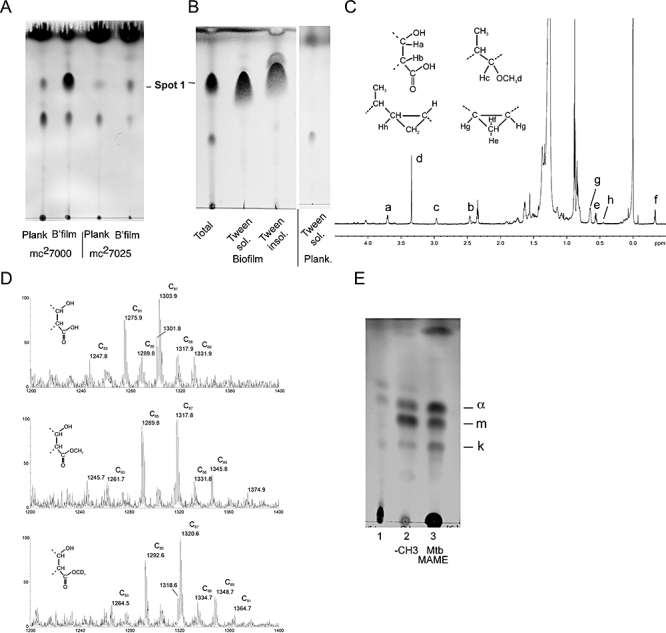

Separation of Spot 1 by TLC and quantification shows that it is present in about fivefold greater abundance in biofilms than in planktonically grown cells (Table S1). Furthermore, the abundance of Spot 1 is reduced in mc27025 mutant biofilms grown under the same conditions as the parental strain (Fig. 4A), indicating that accumulation of spot 1 closely correlates with formation of mature biofilms structures. We further tested whether Spot 1 is anchored to the mycobacterial cells within a biofilm, in which case a strong chemical hydrolysis would be required to isolate it, or if it is extracellular and can be readily extracted by a mild detergent treatment. As shown in Fig. 4B, a substantial proportion of the Spot 1 material is readily extracted with Tween-80, consistent with it being extracellular and presumably a component of the extracellular matrix. To eliminate the possibility that Spot 1 is also present in planktonically grown cells but lost from the sample as a result of solubilization with detergent, we analysed the supernatant of a planktonic culture, but found that Spot 1 is absent (Fig. 4B). Spot 1 is thus specifically made by M. tuberculosis growing in biofilms.

Fig. 4.

M. tuberculosis biofilms contain free mycolic acids.

A. 1D-TLC of apolar lipids extracted from either M. tuberculosis mc27000 cells or the mc27025 mutant growing either planktonically or as biofilms resolved in solvent system C. Samples were labelled with 14C-acetate and equal amounts of total radioactivity were examined.

B. Tween-80 solubilization of biofilm lipids. Biofilm samples were Tween-80 extracted and the Tween-soluble and Tween-insoluble fractions separated by TLC as above. The Tween-containing supernatant from planktonically grown cells was analysed similarly.

C. 1H-NMR spectrum of Spot 1. 1H signals of protons associated with functional groups were assigned using known chemical shifts (Watanabe et al., 1999; X. Trivelli and Y. Guerardel, unpubl. obs.) and labelled (a to h) according to their relative positions. A slight de-shielding of Ha (Δδ + 0.06 p.p.m.) proton from 3.64 to 3.70 p.p.m. and Hb (Δδ + 0.03 p.p.m.) proton from 2.43 to 2.46 p.p.m. compared with their equivalent protons associated to a methyl-esterified carboxyl group is in agreement with the occurrence of a free mycolate.

D. MALDI-TOF-MS analysis of native (top panel), -CH3 (middle panel) and -CD3 (bottom panel) esterified Spot 1. Signals correspond to [M + Na]+ adducts of a family of methoxy mycolates.

E. Spot 1 (lane 1) was methyl-esterified (lane 2) and compared with methyl-esterified mycolic acids purified from Mtb cell wall (lane 3), by resolution on a TLC plate developed in petroleum ether : acetone (95:5) and visualized as in Fig. 4A. a, m and k indicate the alpha, methoxy and keto mycolic acids respectively.

Chemical analysis of Spot 1 shows that it corresponds to free mycolic acids. First, we characterized the Spot 1 lipid by 1H-NMR, which shows specific signals indicative of the presence of functional groups of mycolic acids (Fig. 4C). In addition to the protons adjacent to the carboxyl group that are ubiquitously observed in mycolic acids (Fig. 4C, Ha and Hb), cis-cyclopropyl (Fig. 4C, He, Hf and Hg) and α-methyl methoxy groups (Fig. 4C, Hc, Hd) are readily identified on the 1H-NMR spectrum and confirmed by 1H-13C HSQC NMR experiments (data not shown), strongly suggesting the presence of methoxy mycolates as major components, and probably α mycolates. In addition, minor signals assigned to keto groups were observed in small amounts, establishing the presence of keto mycolates as minor compounds (about 10%). However, no signals indicative of cis- or trans-double bonds were observed, ruling out the occurrence of α1 and α2 mycolates. Most informative are the 1H-NMR chemical shifts of the -CHa- and -CHb- signals that are noticeably de-shielded from 3.64 to 3.70 p.p.m. and from 2.43 to 2.46 p.p.m., respectively, compared with their equivalents when the carboxyl group is methyl-esterified (Watanabe et al., 2001), which suggests that the carboxyl group is free. Accordingly, 1H-13C HMBC experiment of Spot 1 (data not shown) did not show any correlation between the carbon of the carboxyl group and a proton of a potential carrier molecule through a 3JH-C. Furthermore, although very close, the NMR parameters of Hb also slightly differ from those of the -CH2-COOH group of a free fatty acid (2.34 p.p.m.) because of the de-shielding effect of the hydroxyl group in the beta position of mycolic acids. This demonstrates that signals associated with free carboxyl groups do not originate from a contamination of free linear fatty acids in Spot 1. These NMR data strongly suggest that the carboxyl group of the mycolic acid is not engaged in linkage with the C5 carbon of an arabinosyl residue or the C6 carbon of a glucose residue – as observed in mAGP or in TDM respectively – but is free.

The MALDI-TOF analysis of Spot 1 (Fig. 4D) shows several major signals between m/z 1247 and 1331 with 14 mu increments fitting with [M + Na]+ adducts either of C82-C86 methyl-esterified methoxy-mycolic acids (Fujita et al., 2005) or, in accordance with the NMR data, of a family of C83-C87 free methoxy mycolates. In agreement with this hypothesis, esterification of Spot 1 with methyl groups (-CH3) in aqueous strong alkali solution led to a mass increment of 14 mu of all the signals, demonstrating the presence of a methylable function, presumably the free carboxylic group, on the molecule. Values of methylated compounds from m/z 1261–1345 fit with those of C83-C87 methyl-esterified methoxy mycolates, as previously described (Fujita et al., 2005). It is noteworthy that the respective intensities of each signal before and after methylation are almost identical (Fig. 4D), strongly suggesting that both families of compounds are indeed related. In addition, esterification of Spot 1 with deuteromethyl (-CD3) group incremented all signals by 17 mu, which unambiguously demonstrated that the 14 mu increment was the result of the addition of a single methyl group to the mycolic acid. Finally, 1H-NMR analysis of the methylated product shows an almost identical spectrum to that of the native molecule, only differing by the chemical shifts of the -CHa- and -CHb- groups that shift back to their typical values for methyl-esterified mycolic acids, demonstrating that methylation occurred on the free carboxyl group. This was further confirmed by 1H-13C HMBC analysis of methylated Spot 1 (data not shown) that showed a clear 3JH-C correlation between the carbon of the carboxyl group and the proton of the methyl group. TLC analysis of methyl-esterified Spot 1 also confirmed the presence of methoxy mycolates with lesser amounts of both α and keto mycolates (Fig. 4E). Thus taken together, NMR, MS and TLC analyses of native and methyl-esterified Spot 1 unambiguously confirm that it is composed of free mycolic acids, an observation of some interest as we are not aware of any other condition in which free mycolic acids are abundant components of M. tuberculosis cultures.

Re-examination of the biofilm-associated fatty acids of M. smegmatis reported previously (Ojha et al., 2005) suggests that these are also free mycolic acids (data not shown). Apolar lipids with similar properties to those in M. tuberculosis can be extracted without hydrolysis and are at reduced levels in the ΔgroEL1 mutant (data not shown). Thus, the development of biofilm-associated extracellular matrices composed of free mycolic acids is not unique to M. tuberculosis, and it seems more likely that these are common features of mycobacterial biofilms. Furthermore, the production of these M. smegmatis lipids does not appear to be via de novo synthesis (Ojha et al., 2005), but rather a GroEL1-mediated switch in the action of the FAS-II system. Because the mycolates are usually covalently attached to the cell surface, it is plausible that the free mycolic acids primarily are generated by cleavage of the ester linkages anchoring them to arabinogalactan, although a putative esterase that could be responsible for this has yet to be identified. This suggests the possibility that mycolic acids play two separate but important roles in mycobacterial physiology: conferring cohesion and structure to biofilm communities of cells, and only being cell-associated when mycobacterial cells are free to migrate from one community to another. We also note that while a groEL1 mutant of M. tuberculosis exhibits no obvious biofilm phenotype under the standard conditions for biofilm growth described here (A.K. Ojha and G.F. Hatfull, unpubl. obs.), M. tuberculosis groEL1 is required for granulomatous inflammation in both mice and guinea pigs (Hu et al., 2008).

Mycobacterium tuberculosis biofilms contain highly drug-tolerant persister cells

Bacterial biofilms typically have a high proportion of cells that are non-responsive to antimicrobials, and these likely correspond to persisters that arise as a result of phenotypic variation in a subpopulation of heterogeneous bacilli and are seen in a variety of microbial species (Spoering and Lewis, 2001; Dhar and McKinney, 2007; Lewis, 2007). We therefore tested whether M. tuberculosis biofilms also display phenotypic variation in response to antibiotics (Fig. 5). In planktonic growth, incubation with either isoniazid or rifampicin leads to cell death and the rate of killing is linear over a 5 day period. In contrast, M. tuberculosis biofilms have a high proportion of cells (∼10%) that survive isoniazid treatment, even at concentrations (10 μg ml−1) greatly above the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) (∼0.1 μg ml−1). As isoniazid fails to kill non-growing cells, this may simply mean that 10% of the cells are not in an active growing state, although we note that the mc27025 mutant is nearly 10-fold more sensitive than its parent strain when grown under these conditions (Fig. 5A).

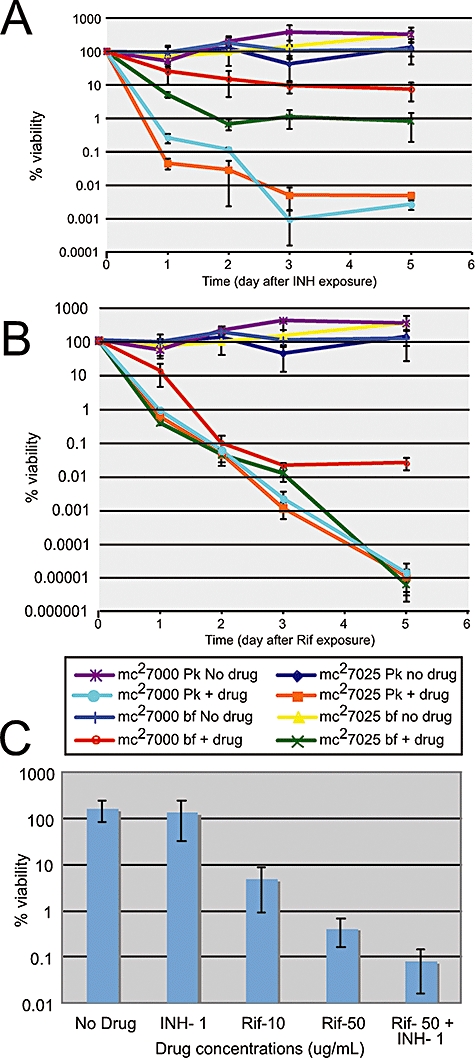

Fig. 5.

M. tuberculosis biofilms are drug-tolerant. M. tuberculosis mc27000 or the biofilm-defective mc27025 mutant were grown planktonically or as biofilms and treated with either isoniazid (A) or rifampicin (B); the percentages of viable cells remaining after different times of drug treatment are shown. (C) Percentage of surviving cells following 7 day treatment of M. tuberculosis biofilms with antibiotics at different concentrations.

In contrast, M. tuberculosis biofilms are fully responsive to high rifampicin exposure over a 3 day period with a > 1000-fold reduction in viability (Fig. 5B); however, further exposure causes no reduction in viability, indicating a substantial subpopulation of cells surviving this treatment. At lower concentrations of rifampicin (10 μg ml−1) – still substantially above the MIC (∼1 μg ml−1) – an even greater proportion of drug-tolerant persisters was observed (∼8%; Fig. 5C) following 7 days of exposure. Reducing the INH concentration to 1 μg ml−1 somewhat reduced the proportion of drug-tolerant biofilm cells, but did exhibit a modest synergistic effect when used in combination with rifampicin (Fig. 5C).

This biphasic killing curve in response to rifampicin treatment (Fig. 5A and B) is characteristic of cultures that contain a substantial proportion of persisters, cells that are not killed by the antibiotics but remain genetically sensitive (Dhar and McKinney, 2007); in patients, M. tuberculosis is killed rapidly over the first 2 days of drug treatment, but more slowly thereafter (Jindani et al., 2003). We have analysed the colonies recovered after 5 days of rifampicin treatment, and all tested remain fully antibiotic-sensitive. M. tuberculosis mc27025 does not contain these persisters (Fig. 5B), demonstrating that drug tolerance is biofilm-dependent.

Conclusions

In this study, we have shown that M. tuberculosis forms pellicular biofilms that are distinct from planktonic growth. We have demonstrated that the M. tuberculosis requires a specific environment and genetic programme to form organized biofilm communities which harbour drug-tolerant cells within a structure rich in free mycolic acids. Although the question as to whether M. tuberculosis forms biofilms during infectious growth has received little attention, within the primary granulomas in guinea pig lungs, an acellular rim has been observed adjacent to the edge of the mineralizing central necrosis containing drug-tolerant bacteria in microcolonies with features reminiscent of biofilms (Lenaerts et al., 2007). Taken together with our demonstration that M. tuberculosis forms biofilms as a defined and distinct physiological state harbouring drug-tolerant persisters, we propose that biofilm development represents an excellent drug target. Identification of drugs that inhibit biofilm formation could enable the dramatic shortening of tuberculosis treatments using standard antibiotics, with substantial potential impact on global health and reduction of antibiotic resistance associated with non-compliance.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains, media and growth conditions

Mycobacterium tuberculosis mc27000 is an unmarked version of mc26030 (Sambandamurthy et al., 2006) and the hyg sacB cassette was removed by transduction with phAE87 containing the γδ resolvase and screening for sucrose-resistant and hygromycin-sensitive isolates. mc27000 fails to kill SCID mice following intravenous challenge and is ultimately cleared and has been approved for use in Biosafety Level 2 containment by the Institutional Biosafety Committees of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and University of Pittsburgh. Unless otherwise stated, M. bovis BCG (Pasteur) and M. tuberculosis mc27000 were grown planktonically in 7H9OADC with 0.05% Tween-80 in 5% CO2 and mc27000 was supplemented with 100 μg ml−1 of pantothenic acid. Antibiotics hygromycin (75 μg ml−1) and kanamycin (25 μg ml−1) were added as appropriate.

Biofilm growth

Biofilms of M. bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis (mc27000) were grown in polystyrene Petri dishes by inoculating 10 ml of Sauton's medium (without Tween-80) with 100 μl of a saturated planktonic culture and incubating without shaking at 37°C for 5 weeks in humidified conditions. The dishes were either unwrapped or wrapped with parafilm during incubation. Biofilms of M. tuberculosis strains (mc27000, mc24640, mc24640-comp, mc27025) were also grown in 250 ml polystyrene bottles by inoculating 25 ml of Sauton's media with 250 μl of a saturated planktonic culture and incubating without shaking at 37°C for 5 weeks. Bottles were incubated either loose- or tight-capped in air or with 5% CO2.

Isolation of M. tuberculosis biofilm-defective mutants

A TnHimar transposon library of M. tuberculosis, mc27000 (Bardarov et al., 1997), was screened for mutants defective in the formation of biofilms in 96-well plates. Single colonies were inoculated into Sauton's media without Tween-80 and incubated at 37°C for 5 weeks (D. Sambandan et. al., in preparation). Transposon insertion sites were determined by junction cloning and DNA sequencing. Construction of M. tuberculosis mc24640 was constructed by replacing Rv2454c and Rv2455c for 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (nucleotides 2753746–2756555 corresponding to the published H37Rv genome sequence, Cole et al., 1998) of mc27000 with a hygromycin-resistance cassette (Bardarov et al., 2002); mc24640-comp was constructed by transformation with a pYUB1052 derivative (Braunstein et al., 2000) containing the Rv2454c-Rv2455c region (H37Rv nucleotides 2721932–2757635).

GC-MS analysis

Biofilms of mc27000 were grown in 24 ml of Sauton's media in 236 ml screw-capped glass bottles (with hole caps and septa) in either tightened or loosened-lid conditions. After 3 weeks of incubation, the lids of all the bottles were tightened and the air from the overhead space withdrawn and injected into a GC-MS instrument (Hewlett Packard) with Agilent J and W column. The instrument was maintained at 20°C for the entire run time and the mass spectra of the GC peaks were collected between 1 and 200 amu.

Drug tolerance assays

For the drug tolerance assay, biofilms of M. tuberculosis (mc27000 and mc27025) were grown in 12-well polystyrene tissue culture plates, each well containing 6 ml of Sauton's media and inoculated with 60 μl of saturated planktonic culture. The plates were parafilm-wrapped and incubated at 37°C for 5 weeks. One set of cultures was harvested at time t0 by collecting the biomass in 0.2% Tween-80, gentle agitation at 4°C for 24 h with 1 mm glass beads and plated for cell viability. From the remaining wells, one set was kept as ‘no-drug control’ and to the rest, either isoniazid (20 μg ml−1) or rifampicin (50 μg ml−1) was injected through the biofilm into the media. Cells were harvested at various times with 0.2% Tween-80, washed twice with Sauton's medium, re-suspended in 6 ml of the same medium, gently agitated at 4°C for 24 h with 0.1% Tween and 1 mm glass beads, and cell viabilities determined. Planktonic cultures of the mc27000 and mc27025 at 0.2 OD were exposed to the same drug concentrations and viabilities determined.

Lipid extraction and analysis

Mycobacterium tuberculosis was grown planktonically to OD 0.2 or in biofilms for 5 weeks, labelled with 1.0 μCi ml−1 of 14C acetate for 24 h prior, and harvested. Cells were re-suspended in 5 ml of methanol: 0.3% NaCl (100:10), mixed with 2.5 ml of petroleum ether for 30 min at room temperature, and the upper petroleum ether layer containing the apolar lipids separated by centrifugation. After solvent evaporation, apolar lipids were dissolved in 0.5 ml of Dichloromethane, and amounts equivalent to 50 000 counts of each sample were analysed by silica two-dimensional TLC developed in solvent systems A (1st dimension – petroleum ether/ethyl acetate 98:2 three times, 2nd dimension – petroleum ether/acetone 98:2), C (1st dimension – chloroform/methanol 96:4, 2nd dimension – toulene/acetone 80:20) and D (1st dimension – chloroform/methanol/water 100:14:0.8, 2nd dimension – chloroform/acetone/methanol/water 50:60:2.5:3) described previously (Dobson et al., 1985). Lipids equivalent to 50 000 c.p.m. were loaded from each sample and visualized by spraying 5% molybdophosphoric acid.

The polar lipids from the menthanol-saline bottom layer were extracted following the same protocol and the lipids were resolved on 2D-TLC using solvent system D.

Free and cell-associated lipids were separated by extraction of 5 week biofilms in 15 ml of PBS containing 0.2% Tween-80 and 1 mm glass beads for 24 h, followed by centrifugation at 6000 r.p.m. for 15 min. Apolar lipids were extracted from the supernatant and the cell pellet as described above. For further analysis of Spot 1, the lipid was scraped off a TLC plate, extracted thrice in diethyl ether and dried.

Mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry analyses of Spot 1 were done on a Voyager Elite reflectron MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA, USA), equipped with a 337 nm UV laser. Samples were solubilized in 1 ml of chloroform/methanol (2:1) of which 1 μl was mixed with 1 μl of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid matrix solution (10 mg ml−1 dissolved in chloroform/methanol 2:1). Spot 1 was analysed in native and esterified forms; dried samples were treated in 1 ml of 15% tetrabutyl ammonium hydroxide at 100°C overnight, esterified by adding 2 ml of chloroform, 1 ml of water and 150 ml of either ICH3 or ICD3 and sonicated for 1 h. Methyl-esterified samples were extracted twice with chloroform/water mixture and dried under a stream of nitrogen.

NMR analyses

Samples were dissolved into deuterated chloroform containing 0.03% of TMS for 1H and 13C referring and transferred into Shigemi tubes matched for D2O. 0.1 ml of deuterium oxide was added to avoid solvent evaporation during long acquisition (Wieruszeski et al., 2006). 1D proton, 2D-COSY, 2D-ROESY with 400 and 450 ms mixing time, 2D-13C-HSQC with multiplicity editing during selecting step and 2D-HMBC experiments were recorded at 299K on a 800 MHz Avance II and 400 MHz Avance Bruker spectrometers at 299K equipped with a 1H/13C/15N/2H and a broad-band probes respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amy Vogelsburger and Tom Harper for excellent technical support. This work was supported by grants from NIH (AI064494) to G.F.H.; the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (ATIP ‘Microbiologie Fondamentale) to L.K.; A.D.B. is supported by a grant from the Helen Hay Whitney Foundation. The 800 MHz NMR spectrometer was funded by European Union (FEDER), Ministère Français de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche, région Nord-Pas de Calais, Université des Sciences et Technologies de Lille, and CNRS.

Supplementary material

This material is available as part of the online article from: http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/

j.1365-2958.2008.06274.x

(This link will take you to the article abstract).

Please note: Blackwell Publishing is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supplementary materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Anderson GG, Dodson KW, Hooton TM, Hultgren SJ. Intracellular bacterial communities of uropathogenic Escherichia coli in urinary tract pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:424–430. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban NQ, Merrin J, Chait R, Kowalik L, Leibler S. Bacterial persistence as a phenotypic switch. Science. 2004;305:1622–1625. doi: 10.1126/science.1099390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banin E, Vasil ML, Greenberg EP. Iron and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11076–11081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504266102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardarov S, Kriakov J, Carriere C, Yu S, Vaamonde C, McAdam RA, et al. Conditionally replicating mycobacteriophages: a system for transposon delivery to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10961–10966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardarov S, Pavelka MS, Sambandamurthy V, Larsen M, Tufariello J, Chan J, et al. Specialized transduction: an efficient method for generating marked and unmarked targeted gene disruptions in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M. bovis BCG and M. smegmatis. Microbiology. 2002;148:3007–3017. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-10-3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besra GS. Preparations of cell wall fractions from mycobacteria. In: Parish T, Stoker NG, editors. Mycobacteria Protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1998. pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Betts JC, Lukey PT, Robb LC, McAdam RA, Duncan K. Evaluation of a nutrient starvation model of Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence by gene and protein expression profiling. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:717–731. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branda SS, Vik S, Friedman L, Kolter R. Biofilms: the matrix revisited. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunstein M, Griffin TI, Kriakov JI, Friedman ST, Grindley ND, Jacobs WR., Jr Identification of genes encoding exported Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteins using a Tn552′phoA in vitro transposition system. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2732–2740. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.10.2732-2740.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284:1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darzins E, Fahr G. Cord-forming property, lethality and pathogenicity of Mycobacteria. Dis Chest. 1956;30:642–648. doi: 10.1378/chest.30.6.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb C, Daniel J, Sirakova TD, Abomoelak B, Dubey VS, Kolattukudy PE. A novel lipase belonging to the hormone-sensitive lipase family induced under starvation to utilize stored triacylglycerol in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3866–3875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505556200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar N, McKinney JD. Microbial phenotypic heterogeneity and antibiotic tolerance. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson G, Minnikin DE, Minnikin SM, Partlett JH, Goodfellow M, Ridell MMM. Systematic Analysis of Complex Mycobacterial Lipids. London: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y, Naka T, McNeil MR, Yano I. Intact molecular characterization of cord factor (trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate) from nine species of mycobacteria by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Microbiology. 2005;151:3403–3416. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Stoodley L, Lappin-Scott H. Biofilm formation by the rapidly growing mycobacterial species Mycobacterium fortuitum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;168:77–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Stoodley L, Brun OS, Polshyna G, Barker LP. Mycobacterium marinum biofilm formation reveals cording morphology. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;257:43–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopewell PC, Pai M, Maher D, Uplekar M, Raviglione MC. International standards for tuberculosis care. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:710–725. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70628-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Henderson B, Lund PA, Tormay P, Ahmed MT, Gurcha SS, et al. A Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutant lacking the groEL homologue cpn60.1 is viable but fails to induce an inflammatory response in animal models of infection. Infect Immun. 2008;76:1535–1546. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01078-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jindani A, Dore CJ, Mitchison DA. Bactericidal and sterilizing activities of antituberculosis drugs during the first 14 days. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1348–1354. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1125OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenaerts AJ, Hoff D, Aly S, Ehlers S, Andries K, Cantarero L, et al. Location of persisting mycobacteria in the Guinea pig model of tuberculosis revealed by R207910. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3338–3345. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00276-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K. Persister cells, dormancy and infectious disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:48–56. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsollier L, Aubry J, Coutanceau E, Andre JP, Small PL, Milon G, et al. Colonization of the salivary glands of Naucoris cimicoides by Mycobacterium ulcerans requires host plasmatocytes and a macrolide toxin, mycolactone. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:935–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojha A, Hatfull GF. The role of iron in Mycobacterium Smegmatis biofilm formation: the exochelin siderophore is essential in limiting iron conditions for biofilm formation but not for planktonic growth. Mol Microbiol. 2007;66:468–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojha A, Anand M, Bhatt A, Kremer L, Jacobs WR, Hatfull GF. GroEL1: a dedicated chaperone involved in mycolic acid biosynthesis during biofilm formation in mycobacteria. Cell. 2005;123:861–873. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish T, Smith DA, Kendall S, Casali N, Bancroft GJ, Stoker NG. Deletion of two-component regulatory systems increases the virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2003;71:1134–1140. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1134-1140.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recht J, Kolter R. Glycopeptidolipid acetylation affects sliding motility and biofilm formation in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5718–5724. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.19.5718-5724.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recht J, Martinez A, Torello S, Kolter R. Genetic analysis of sliding motility in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4348–4351. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.15.4348-4351.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts ME, Stewart PS. Modelling protection from antimicrobial agents in biofilms through the formation of persister cells. Microbiology. 2005;151:75–80. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27385-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustad TR, Harrell MI, Liao R, Sherman DR. The enduring hypoxic response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambandamurthy VK, Derrick SC, Hsu T, Chen B, Larsen MH, Jalapathy KV, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis DeltaRD1 DeltapanCD: a safe and limited replicating mutant strain that protects immunocompetent and immunocompromised mice against experimental tuberculosis. Vaccine. 2006;24:6309–6320. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze-Robbecke R, Fischeder R. Mycobacteria in biofilms. Zentralbl Hyg Umweltmed. 1989;188:385–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh PK, Schaefer AL, Parsek MR, Moninger TO, Welsh MJ, Greenberg EP. Quorum-sensing signals indicate that cystic fibrosis lungs are infected with bacterial biofilms. Nature. 2000;407:762–764. doi: 10.1038/35037627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirgel FA, Fourie PB, Donald PR, Padayatchi N, Rustomjee R, Levin J, et al. The early bactericidal activities of rifampin and rifapentine in pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:128–135. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200411-1557OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoering AL, Lewis K. Biofilms and planktonic cells of Pseudomonas aeruginosa have similar resistance to killing by antimicrobials. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:6746–6751. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.23.6746-6751.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilcheze C, Wang F, Arai M, Hazbon MH, Colangeli R, Kremer L, et al. Transfer of a point mutation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis inhA resolves the target of isoniazid. Nat Med. 2006;12:1027–1029. doi: 10.1038/nm1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voskuil MI, Schnappinger D, Visconti KC, Harrell MI, Dolganov GM, Sherman DR, Schoolnik GK. Inhibition of respiration by nitric oxide induces a Mycobacterium tuberculosis dormancy program. J Exp Med. 2003;198:705–713. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis RS, Patil S, Cheon SH, Edmonds K, Phillips M, Perkins MD, et al. Drug tolerance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2600–2606. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.11.2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Ohta A, Sasaki S, Minnikin DE. Structure of a new glycolipid from the Mycobacterium avium–Mycobacterium intracellulare complex. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2293–2297. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.7.2293-2297.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Aoyagi Y, Ridell M, Minnikin DE. Separation and characterization of individual mycolic acids in representative mycobacteria. Microbiology. 2001;147:1825–1837. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-7-1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayne LG, Sohaskey CD. Nonreplicating persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:139–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieruszeski JM, Landrieu I, Hanoulle X, Lippens G. ELISE NMR: experimental liquid sealing of NMR samples. J Magn Reson. 2006;181:199–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Siddiqi N, Rubin EJ. Differential antibiotic susceptibilities of starved Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:4778–4780. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4778-4780.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.