Abstract

The formation of sialic glycosides using a thiosialic acid derivative, diphenyl sulfoxide and trifluoromethanesulfonic anhydride is reported. With an excess of diphenyl sulfoxide glycal formation can be completely suppressed and excellent yields are obtained for coupling to a wide range of primary, secondary and tertiary acceptors.

The sialic acids, discovered in vertebrates by Blix and Klenk in 1941, are a family of more than 40 2-keto-3-deoxy-nonulosonic acids that are incorporated in oligosaccharides and glycoconjugates which play important biological roles in high animals and human beings.1 The lead member of the series, N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac), is often found at the terminal positions of glycoproteins and glycolipids and connected to galactosides or 2-acetamido-galactosides by α(2→3) or α(2→6) linkages. The biological significance of the sialic acid glycosides combines with the widely acknowledged difficulty inherent in their synthesis to render this class of glycosidic bonds one of the most widely studied in the field of carbohydrate chemistry.2,3 Both the challenge and the importance of the problem are readily appreciated from the application of almost every major class of glycosidic bond forming reaction to the sialic acid glycosides in recent years.2,3,4 Thioglycosides are no exception to this rule, with most common promoters having been evaluated in this respect,2,3,4 with the exceptions of the recent 1-benzenesulfinyl piperidine (BSP)/triflic anhydride system developed in this laboratory,5,6 the related diphenyl sulfoxide (Ph2SO)/triflic anhydride method as adapted to the thioglycosides by van Boom,6,7 and the Kahne sulfoxide method.6,8 We are interested in developing rapid, low temperature α-selective sialylations from thioglycoside donors, avoiding the use of acetonitrile and its stereodirecting effect, which is common to much work in the area,2,3,4,9 and report here on our preliminary observations.

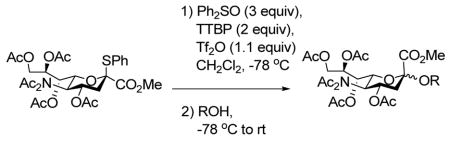

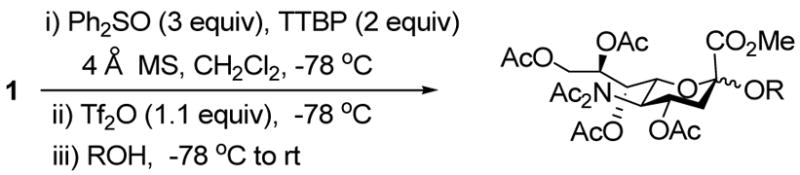

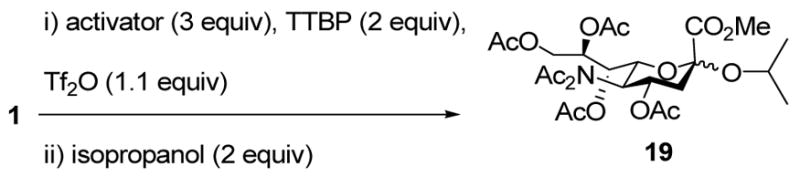

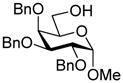

Among the various 2-thiosialyl donors, we chose methyl 2-β-phenylthio-4,7,8,9-tetra-O-acetyl N,N-diacetylneuraminate 1, because of its crystalline nature and enhanced selectivity, compared to the N-monoacetyl counterpart.3n,10 Initially, we investigated our BSP/Tf2O/TTBP activation method,7 but saw no activation even after changing the hydroxy protecting groups from esters to more armed silyl ethers. We explored therefore the more potent promotion system Ph2O/Tf2O, which was developed by Gin for dehydrative glycosylation strategies,11 including sialytations.11d Hoping to generate the β-anomeric sialyl triflate as intermediate species, we first applied a stoichiometric quantity of the Ph2SO/Tf2O combination in the presence of the mild, hindered base 2,4,6-tri-tert-butylpyrimidine (TTBP).12 Unfortunately, while activation was complete at −78 °C in a matter of minutes, it was followed by immediate and quantitative elimination to the glycal 3. However, raising the amount of Ph2SO to 3 equivalents, with otherwise unchanged conditions, we found that the coupling reaction proceeded in excellent yield and good selectivity on subsequent addition of isopropanol (Table 1, entry 1, 97%, 2.3:1 α/β). We postulate that the initial intermediate oxacarbenium ion/anomeric triflate pair 2 undergoes instantaneous decomposition to the glycal 3 in the absence of a suitable nucleophile. However, in the presence of excess sulfoxide this species is trapped to give two covalent sulfonium salts 4 and 5, which serve as resevoirs for the oxacarbenium ion in the subsequent glycosylation. Low temperature NMR experiments in CD2Cl2 support this hypothesis, with two apparently isomeric species being observed in the ratio 1.5:1 when the reaction was conducted with 3 equiv of Ph2SO.13 These intermediates, tentatively assigned to 4 and 5, were immediately converted to the two methyl glycosides, also in the ratio 1.5:1 on addition of methanol at −78 °C.

Table 1.

Coupling the Presence of 300% Diphenyl Sulfoxide

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entry | acceptor | product: % yielda (α:β)b |

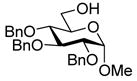

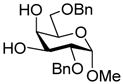

| 1 |

6 |

19: 97% (2.3:1) |

| 2 | MeOH

7 |

20: 94% (1.5:1) |

| 3 |

8 |

21: 91% (1:1) |

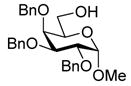

| 4 |

9 |

22: 89% (3.8:1) |

| 5 |

10 |

23: 92% (2:1) |

| 6 |

11 |

24: 97% (1.2:1) |

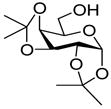

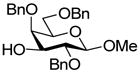

| 7 |

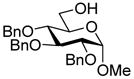

12 |

25: 92% (6:1) |

| 8 |

13 |

26: 94% (10:1) |

| 9 |

14 |

27: 92% (only α)c |

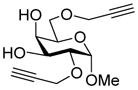

| 10 |

15 |

28: 76% (1:1.2)d |

| 11 |

16 |

29: 81% (1:1.7)d |

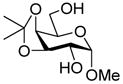

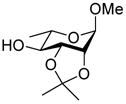

| 12 |

17 |

30: 82% (1:7) |

| 13 |

18 |

- |

isolated yields

determined by 1H NMR on the crude reaction mixture

coupled to the 6-OH

coupled to the 3-OH

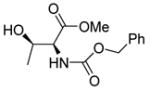

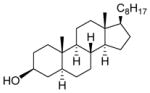

This protocol,14 employing three molar equivalents of diphenyl sulfoxide, was then applied to a range of acceptors (Table 1), with anomeric stereochemistry assigned on the basis of the chemical shift of the sialic acid H-3,15 H-4,16 and, preferably, the sialic acid 3JC1,H3ax.17 With the exception of alcohol 18, for which no coupled product was isolated, the isolated yields of these coupling reactions ranged from good to excellent. Stereoselectivity, on the other hand, varied considerably and was very substrate dependent. Optimal α-selectivities were obtained for the important galactose 6-OH (Table 1, entries 7–9) but, interestingly, considerably lower selectivity was obtained with a glucose 6-OH derivative (Table 1, entry 6). With the 3,4-diols no improvement in selectivity was seen on switching from the 2,6-di-O-benzyl ether 15 to the 2,6-di-O-propargyl ether, despite the reduced steric bulk of the latter acceptor (Table 1, entries 10 and 11).18 Perhaps not surprisingly, the selectivity was obtained with the less reactive 4-OH group (Table 1, entry 12). All in all, it is clear that correct stereochemical matching19 of the acceptor with the donor is important in these couplings, as is becoming increasingly apparent in glycosylation reactions in general.20

With a view to improving the yield, and especially selectivities, we investigated the use of propionitrile as additives, and of several other sulfoxides in place of diphenyl sulfoxide (Table 2).

Table 2.

The Effect of Additives and Sulfoxides

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | activator | solvent (temp.) | % yielda (α:β)b |

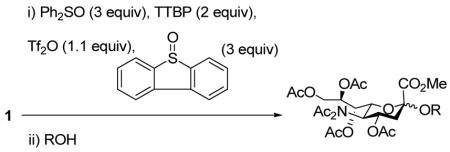

| 1 |

|

CH2Cl2 (− 60 °C) | 82% (2.2:1) |

| 2 |

|

CH2Cl2/CH3CN 1:1 (− 78 °C) | 89% (1.8:1) |

| 3 |

|

CH3CH2CN (− 78 °C) | 77% (2:1) |

| 4 | (4-No2-Ph)PhSO | CH2Cl2 (− 78 °C) | 75% (2.7:1) |

| 5 | (4-MeO-Ph)PhSO | CH2Cl2 (− 78 °C) | 50% (2:1) |

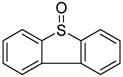

| 6 |

|

CH2Cl2 (− 78 °C) | 50% (6:1) |

isolated yields

determined by 1H NMR on the crude reaction mixture

While a marginally better yield was obtained when the standard solvent was replaced by a 1:1 mixture of acetonitrile and dichloromethane, the α:β selectivity was diminished on coupling to isopropanol (Table 2, entries 1and 2). The use of propionitrile alone as solvent also failed to bring about the desired improvement in selectivity (Table 2, entry 3). Reverting to dichloromethane as solvent, the replacement of diphenyl sulfoxide by the more electron-deficient 4-nitrophenyl phenyl sulfoxide brought about a small increase in selectivity (Table 2, entry 4), while the more electron-rich 4-methoxyphenyl phenyl sulfoxide gave no increase in selectivty and a substantially lower yield (Table 2, entry 5). The use of dibenzothiopene oxide, while giving only a 50% yield of coupled product under the standard activation conditions did result, however, in a significant increase in selectivity to 6:1 in favor of the α-glycoside with model alcohol isopropanol (Table 2, entry 6). The improvement of selectivity on replacing diphenyl sulfoxide by dibenzothiophene oxide must result from a differing population and/or reactivity of the glycosyl sulfonium ions corresponding to 4 and 5. The relatively low yield obtained with dibenzothiophene oxide as activating agent resulted from poor conversion of the donor 1, which is presumably due to reduced electrophilicity of its O-trifluoromethansulfonylated adduct. Accordingly, we developed a protocol in which donor 1 was activated with Tf2O in the presence of both diphenyl sulfoxide and dibenzothiophene oxide and applied to several coupling reactions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Use of Dibenzothiophene as Additive

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entry | acceptor | product: % yielda (α:β)b |

| 1 |

6 |

19: 95% (6:1) |

| 2 |

9 |

22: 62% (3.2:1) |

| 3 |

11 |

24: 65% (1:1) |

| 4 |

12 |

25: 67% (5:1) |

isolated yields

determined by 1H NMR on the crude reaction mixture

Unfortunately, the improvement in selectivity seen with isopropanol did not extended to any of the other examples investigated.

In summary, we have shown that the challenging α-sialylation with 2-thiosialic acid donors can be efficiently performed using the diphenyl sulfoxide/trifluoromethanesulfonic anhydride promotion system. The use of excess diphenyl sulfoxide is shown to be important in these couplings and serves to suppress the formation of the glycal by trapping the first-formed oxacarbenium ion, as suggested by low temperature NMR studies. Sialylations of a series of alcohol nucleophiles showed satisfactory yields and variable anomeric selectivities that are sensitive to the exact nature of the acceptors. With this new procedure, the Neu5Ac α(2→6) Gal glycosidic linkages can be installed with excellent yield and selectivity. Sialylation of secondary sugar acceptors and even the simple tertiary alcohol 1-adamantanol proceeded with good yield but modest selectivity.

Supplementary Material

Full experimental details and characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH (GM 62160) for support of this work.

References

- 1.(a) Schauer R, editor. Sialic Acids: Chemistry, Metabolism and Function. Vol. 10 Springer-Verlag; Wien, New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]; (b) Rosenberg A, editor. Biology of Sialic Acids. Plenum Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Recent reviews: Boons GJ, Demchenko AV. Chem Rev. 2000;100:4539–4565. doi: 10.1021/cr990313g.Ress DK, Linhardt RJ. Current Organic Synthesis. 2004;1:31–46.Boons G-J, Demchenko AV. In: Carbohydrate-based Drug Discovery. Wong C-H, editor. Vol. 1. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2003. pp. 55–102.Kiso M, Ishida H, Ito H. In: Carbohydrates in Chemistry and Biology. Ernst B, Hart GW, Sinaÿ P, editors. Vol. 1. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2000. pp. 345–365.Halcomb RL, Chappell MD. In: Glycochemistry: Principles, Synthesis, and Applications. Wang PG, Bertozzi CR, editors. Dekker; New York: 2001. pp. 177–220.Toshima K, Tatsuta K. Chem Rev. 1993;93:1503–1531.Boons GJ. Contemp Org Synth. 1996;3:173–200.Roy R. Top Curr Chem. 1997;187:241–274.Hasegawa A. In: Modern Methods in Carbohydrate Synthesis. Khan SH, O’Niell RA, editors. Harwood; Amsterdam: 1996. pp. 277–300.Hasegawa A, Kiso M. In: Preparative Carbohydrate Chemistry. Hanessian S, editor. Dekker; New York: 1997. pp. 357–379.

- 3.Recent examples: Tanaka K, Goi T, Fukase K. Synlett. 2005:2958–2962.De Meo C, Parker O. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2005;16:303–307.Lin CC, Huang KT, Lin CC. Org Lett. 2005;7:4169–4172. doi: 10.1021/ol0515210.Tanaka H, Adachi M, Takahashi T. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:849–862. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400840.Meijer A, Ellervik U. J Org Chem. 2004;69:6249–6256. doi: 10.1021/jo049184g.Adachi M, Tanaka H, Takahashi T. Synlett. 2004:609–614.Cai S, Yu B. Org Lett. 2003;5:3827–3830. doi: 10.1021/ol0353161.Ishiwata A, Ito Y. Synlett. 2003:1339–1343.Ando H, Koike Y, Ishida H, Kiso M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:6883–6886.De Meo C, Demchenko AV, Boons GJ. Aust J Chem. 2002;55:131–134.Ye XS, Huang X, Wong CH. Chem Commun. 2001:974–975.Yu C-S, Niikura K, Lin CC, Wong CH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;113:2984–2987.De Meo C, Demchenko AV, Boons GJ. J Org Chem. 2001;66:5490–5497. doi: 10.1021/jo010345f.Demchenko AV, Boons GJ. Chem Eur J. 1999;5:1278–1283.Martichonok V, Whitesides GM. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:8187–8191.Martichonok V, Whitesides GM. J Org Chem. 1996;61:1702–1706. doi: 10.1021/jo951711w.

- 4.Barresi F, Hindsgaul O. J Carbohydr Chem. 1995;14:1043–1087. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crich D, Smith M. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:9015–9020. doi: 10.1021/ja0111481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crich D, Lim LBL. Org React. 2004;64:115–251. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Codée JDC, van den Bos LJ, Litjens REJN, Overkleeft HS, van Boeckel CAA, van Boom JH, van der Marel GA. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:1057–1064. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahne D, Walker S, Cheng Y, Engen DV. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:6881–6882. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boons G-J. In: Handbook of Reagents for Organic Synthesis: Reagents for Glycoside, Nucleotide, and Peptide Synthesis. Crich D, editor. Wiley; Chichester: 2005. pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demchenko AV, Boons GJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:3065–3068. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Garcia BA, Poole JL, Gin DY. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:7597–7598. [Google Scholar]; (b) Garcia BA, Gin DY. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:4269–4279. [Google Scholar]; (c) Nguyen HM, Poole JL, Gin DY. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:414–417. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010119)40:2<414::AID-ANIE414>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Haberman JM, Gin DY. Org Lett. 2003;5:2539–2541. doi: 10.1021/ol034815z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crich D, Smith M, Yao Q, Picione J. Synthesis. 2001:323–326. [Google Scholar]

- 13.The H-3eq peaks of the two anomers (at δ3.1 and 2.9 ppm) are characteristic of the two species in the 1H NMR spectrum.

- 14.General experimental procedure for glycosylation reactions: The 2-thiosialic acid donor 1 (0.11 mmol), diphenyl sulfoxide (Ph2SO, 0.32 mmol), TTBP (0.22 mmol), and activated 4 Å powdered molecular sieves were mixed in anhydrous dichloromethane (2 mL) and cooled down to −78 °C under positive argon pressure. The mixture was stirred at −78 °C for 30 min before Tf2O (0.12 mmol) was added. After 10 min, a solution of acceptor (0.22 mmol) in anhydrous dichloromethane (1 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred from 1 to 6 hs at −78 °C and then warmed up to room temperature, filtered, washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 solution, and brine. The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The glycosides were isolated by silica gel column chromatography or by preparative HPLC.

- 15.Dabrowski U, Friebolin H, Brossmer R, Supp M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979;20:4637–4640. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Paulsen H, Tietz H. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1982;21:927–928. [Google Scholar]; (b) van Halbeek H, Dorland L, Vliegenthart JFG, Pfeil R, Schauer R. Eur J Biochem. 1982;122:305–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb05881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Hori H, Nakajima T, Nishida Y, Ohrui H, Meguro H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:6317–6320. [Google Scholar]; (b) Prytulla S, Lauterwein J, Klessinger M, Thiem J. Carbohydr Res. 1991;215:345–349. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crich D, Jayalath P. Org Lett. 2005;7:2277–2280. doi: 10.1021/ol050680g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masamune S, Choy W, Peterson JS, Sita LR. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1985;24:1–76. [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Paulsen H. In: Selectivity, A Goal for Synthetic Efficiency. Bartmann W, Trost BM, editors. Verlag Chemie; Weinheim: 1984. pp. 169–190. [Google Scholar]; (b) Spijker NM, van Boeckel CAA. Angew Chem Int, Ed Engl. 1991;30:180–183. [Google Scholar]; (c) Fraser-Reid B, López JC, Gómez AM, Uriel C. Eur J Org Chem. 2004:1387–1395. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Full experimental details and characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.