Abstract

Most autoantigens implicated in multiple sclerosis (MS) are expressed not only in the central nervous system (CNS) but also in the thymus and the periphery. Nevertheless, these autoantigens might induce a strong autoimmune response leading to severe destruction within the CNS. To investigate the influence of a dominantly presented autoantigen on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), we generated transgenic mice expressing the autoantigenic peptide MBP1-10 covalently bound to the MHC class II molecule I-Au. These mice were crossed either with B10.PL or with TCR-transgenic Tg4 mice, specific for the transgenic peptide-MHC combination. In double transgenic mice we found strong thymic deletion and residual peripheral T cells were refractory to antigen stimulation in vitro. Residual peripheral CD4+ T cells expressed activation markers and a high proportion was CD25 positive. Transfer of both CD25-negative and CD25-positive CD4+ T cells from double transgenic animals into B10.PL mice strongly inhibited the progression of EAE. Despite this thorough tolerance induction, some double transgenic mice developed severe signs of EAE after an extended period of time. Our data show that in the circumstances where autoantigenic priming persists, and where the number of antigen-specific T cells is high enough, autoimmunity may prevail over very potent tolerance-inducing mechanisms.

Keywords: autoimmunity, central nervous system, T lymphocytes, tolerance, transgenic mice, regulatory T cells

Introduction

The common concept regarding organ-specific autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis (MS) implies that organ-specific antigens are hidden from the naive immune repertoire due to lack of expression outside the organ and to the inability of naive T cells to trans-migrate into these organs. In this way the immune system would not be tolerant towards these hidden antigens but simply ignorant. It is thought that external triggers like viral or bacterial infections initiate the destructive immune response against autoantigens. Infections could either condition the organ and give access to formerly hidden antigens or could activate pre-existing autoantigen-specific naive T cells by molecular mimicry or bystander activation (1, 2). In contrast to naive T cells, activated T cells efficiently trans-migrate into tissues, thereby initiating the autoimmune disease (3). This view was strengthened by experiments with mice harboring TCR-transgenic T cells, which ignored their antigen expressed specifically in the pancreas until infected with viruses expressing this antigen, which ultimately lead to diabetes (4, 5).

This concept of immunological ignorance was challenged by others, who showed that antigens expressed specifically in peripheral organs are indeed recognized by peripheral T cells but readily induce tolerance of the antigen-specific T cells (6). In one system even very low levels of peripherally expressed antigen lead to tolerance induction (7). It was later shown that this so-called “peripheral tolerance mechanism” was dependent on the continuous presence of the antigen (8) and was, in the case of liver-specific antigens, broken by IL-2, irradiation or by listeria infection (9-11). These findings were supported by the concept of the danger theory from Matzinger (12), which emphasizes that only antigens in the context of danger molecules like that seen during infections, now called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (13), lead to the mounting of a destructive (auto-) immune response.

For a long time the central nervous system (CNS) was seen as a special immune-privileged organ that is protected by the blood-brain barrier from the cellular and humoral immune system and that lacks the normal lymphatic drainage of other organs. By this means many of the CNS-specific antigens should be hidden for the immune repertoire (14, 15).

Recently it was shown that in addition to activated T cells also naive T cells might migrate into the brain (16, 17). It also became evident that most of the formerly so-called brain-specific antigens are also expressed either by other peripheral organs or by the thymus (18-23). These two facts contradict the idea of “sequestered autoantigens”. As most of these antigens are expressed also in the thymus and/or in the periphery, they should induce central and/or peripheral tolerance mechanisms, respectively.

A possible explanation of CNS-autoimmune diseases is the existence of a balanced system between tolerance induction, on the one hand, and the precursor frequency and activation of autoreactive T cells, on the other. To investigate this hypothesis, we created transgenic mice that express the autoantigenic N-terminal MBP1-10 peptide, covalently bound to the MHC class II molecule I-Au under the control of an MHC class II promoter. These mice dominantly present the antigen in the thymus and the periphery. We crossed two of these lines, with different expression levels of the transgene, with B10.PL or Tg4 mice transgenic for a TCR, which recognizes the latter peptide-MHC combination (24). These mice allowed us to investigate the influence of T cell precursor frequency and autoantigen expression on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) induction.

We show here that even under very strong tolerance-inducing conditions, where a myelin-autoantigen is dominantly presented in the thymus and in the periphery, some TCR-transgenic mice are susceptible to EAE after an extended induction period.

Methods

Mice

All mice were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions in the animal facilities of the German Cancer Research Centre. B10.PL mice were from Jackson Laboratories and DBA/2 and C57BL/6 strains were from in-house breeding or from WIGA (Hanover, Germany). TCR-transgenic Tg4 mice express the TCR of the T cell hybridoma 1934.4 (Vα4 and Vβ8.2) derived from an encephalitogenic CD4-positive Tcell clone (24, 25). Its TCR is specific for the MBP-derived peptide Ac1-9 presented by I-Au. Tg4 mice, backcrossed to a homozygous I-Au background by the group of David Wraith, were continuously crossed to B10.PL and screened for the transgene either by PCR with tail DNA or by FACS staining of PBLs with anti-CD4 and anti-Vβ8 (F23.1). In transgene-positive mice nearly all CD4+ cells are positive for Vβ8.2. In experiments only Tg4 mice heterozygous for the transgenic TCR were used. For analyzes of double transgenic mice, or (see below) on an I-Au-negative background were crossed with Tg4 mice, litters were tested for the transgenes, and F1-heterozygous animals were used for the assays.

Generation of transgenic MBP-IAu mice

We received from David Wraith the I-Au α and β cDNAs in the expression vectors pHβAPr-2-neo and pHβApr-2gpt, respectively. The Vector pDR51 with the human MHC class II DRβ51 promoter was from Yoshinori Fukui. This promoter was described as vector for reliable and MHC class II-specific expression in several transgenic mouse systems (26, 27). To have an intron in our transgene vectors, we exchanged the SV40-termination sequence of pDR51 by the SV40 splice poly(A) sequence derived via PCR (primer A, TAAGAATTCAAGCTTAGATCTGATCTTTGTGAAGGAACC, and primer B, AATAAGCTTGAATTCGGTACCCGGGGATCGATCCAGACAT) from the vector pBLCAT6. The PCR product was ligated into the HindIII and EcoRI sites of pDR51 to generate pDR51 splice.

β-chain construct

With a first PCR we introduced the C-terminal part of the DRβ51 signal sequence, the MBP peptide and the restriction sites SacI, Bg/II, and HindIII into the I-Au-β cDNA. (primer C, TAAGAATTCGAGCTCCCCACTGGCTTTGGCTGGAGACTCCGGCGCATCACAGAAGAGACCCTCACAGAGATCTGAAAGGCATTTCTTGGTCCAG, and primer D, ATTGGATCCAAGCTTTCACTGCAGGAGCCCTGCTGG). For the appropriate cleavage of the signal sequence we had to introduce the amino acid sequence GDS N-terminal to the MBP sequence. As a replacement of the natural acetylation we use a glycine residue between the GDS sequence and the MBP1-10 sequence (see Fig. 1 and text). With that PCR product we replaced the DRβ51 cDNA of pDR51 splice via SacI and HindIII and created pDR-IAuβ splice. With a second PCR we introduced the linker sequence and two Bg/II sites into the original I-Au cDNA (primer E, GCGGAATTCAGATCTGGAGGTGGTGGATCCGGTGGAGGAGGGAGTGGCGGAGGTGGAAGCGAAAGGCATTTCTTGGTCCAG, and primer F, ATTGGATCCAGATTAAGCTTTCACTGCAGGAGCCCTGCTGG). This PCR product was cloned into the Bg/II sites of pDR-IAuβ splice to get pDR-MBP-IAuβ splice (Fig. 1).

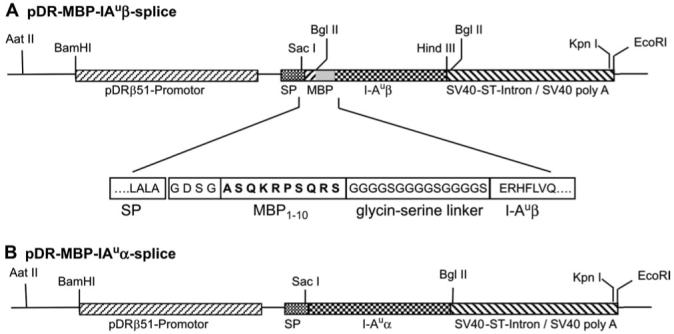

Fig. 1.

DNA constructs used for generation of transgenic mice. The constructs for the MHC class II α (pDR-IAuα splice) and the engineered β chain (pDR-MBP-IAuβ splice) were co-injected. (A) Transgenic DNA construct for the β chain with functional domains and partial amino acid sequence in the region of the MBP peptide (in bold). In the transgenic MPB-IAu mice, the MBP1-10 peptide is connected via a glycine-serine linker to the I-Auβ chain. The first three I-Au-β amino acids GDS are placed N-terminal to the MBP peptide to allow proper cleavage of the signal peptide (SP). The glycine in front of the MBP sequence replaces the natural-found acetylation of the N-terminal MBP peptide. (B) Transgenic DNA construct of the I-Au α chain. Both representations are not drawn to scale.

α-chain construct

For expression of the α chain we also used the DR51 promoter. As we did not want to introduce the GDS sequence N-terminal to the α chain for the proper cleavage of the human pDR51-signal sequence, we planned to replace the three C-terminal amino acid residues of the human signal sequence by the five C-terminal signal sequence residues from the mouse I-Ak sequence. With PCR we introduced the five signal sequence residues and SacI and Bg/II sites into the I-Au α cDNA sequence (primer G, TAAGAATTCGAGCTCCCCACTCAGCCTCTGCGGAGGTGAAGACGACATTGAGGCCGACCATGTAGGC, and primer H, TAAGGATCCAGATCTGAATTCCAAGGGTGTGTG). The PCR product was cloned into the SacI and Bg/II sites of pDR-IAuβ splice to get pDR-IAuα splice (Fig. 1).

Both pDR-IAuα splice and pDR-MBP-IAuβ splice vectors were linearized by AatII and KpnI and the purified fragments were co-injected into C57BL/6 × DBA/2 F2 oocytes. Founders and transgenic litters were tested by Southern blot or PCR of tail DNA (primer sequences—α chain: TGTCCCTCTTCATGGAAGAA and CTGCTCCCATTCATCAGTTC; β chain: CTCAGTGACAGATTTCTACC and CTGCTCCCATTCATCAGTTC). The α and β transgenes were always found to be co-transferred to littermates. Two transgenic mouse lines were established and named and .

Peptides

N-terminal-acetylated MBP1-10 peptide Ac-ASQKRPSQRS (Ac1-10) and its analog with higher affinity to the I-Au molecule Ac-ASQYRPSQRS (Ac1-10 (4Y)) were synthesized in-house using standard Fmoc chemistry and were HPLC purified.

FACS staining and analysis

Staining was performed at 4°C in Dulbecco’s modified PBS supplemented with 3% FCS, 0.45% glucose and 0.01% sodium azide. For most stainings 2-5 × 105 cells from single-cell suspensions were used and were pre-treated with anti-CD16 and anti-CD32 antibodies (Fc-block from BD-Pharmingen) to reduce unspecific staining. Antibodies from BD-Pharmingen were as follows: anti-CD4 PE-labeled GK1.5 clone; anti-CD8α FITC-, biotin- or PE-labeled (53-6.7); anti-CD45R (B220) FITC-, biotin- or PE-labeled; anti-CD62L biotin-labeled (MEL-14); anti-CD69 biotin-labeled (H1.2F3); anti-CD25 biotin-labeled (7D4). Antibodies from GIBCO: anti-CD4 Red613-labeled (H129.19) and anti-CD8α Red613-labeled (53-6.7). The anti-Vβ8-antibody F23.1 (28) and the anti-I-Aβu antibodies MKS4 (29) and 10-2-16 (30) were labeled in our laboratory with biotin (Biotin-X-NHS, Calbiochem) and FITC (Sigma), respectively. To exclude dead cells, cells in the live gate were analyzed and if possible stained with propidium iodide (1 μg ml-1); 5000-10 000 cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACScan; BD).

Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells

Bone marrow stem cells were prepared and differentiated to bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) according to a protocol from Lutz et al. (31). The bone marrow cells were differentiated for 9 days in granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) containing medium. The medium was composed of RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS (Seromed), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U ml-1 penicillin/streptomycin, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 10% of GM-CSF containing supernatant of F1/16 cells. For activation, LPS (1 μg ml-1) was added to the cultures and 24 h later, non-adherent, activated BMDCs were used for FACS staining or T cell proliferation assays. For staining of the transgenic MHC class II on BMDCs the anti-I-Au antibody 10-2-16-bio with streptavidin-PE (SA-PE) was used.

Depletion and isolation of lymphoid cells

B cells were depleted using goat anti-mouse Ig antibodies bound to magnetic particles (Paesel & Lorei, Duisburg). Depletion of MHC class II-positive cells from Tg4 lymphocytes was done after incubation of the cells with the anti-MHC class II-specific antibody MKS4 using Dynabeads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) coupled to goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies.

For T cell transfers single-cell suspensions of spleens and lymph nodes (LNs) were prepared from mice. CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25- T cells were separated using the mouse CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The isolated cells were injected intravenously into the tail vein of B10.PL mice.

T cell proliferation assays

Tg4 lymphocytes were cultured in the presence of titrated amounts of activating MBP peptides or irradiated BMDCs (2000 rad) in a volume of 200 μl in 96-well plates. Medium: RPMI with 10% FCS (Seromed), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U ml-1 penicillin/streptomycin, 1 mM Na-pyruvate and 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol; 24 h later 0.5 μCi [3H]thymidine ([3H]TdR) was added. Proliferation was measured after a further 18-24 h.

EAE induction and scoring

Active EAE was induced according to protocols from Liu and Wraith (32) and Coligan (33). To incomplete freunds adjuvant (IFA) heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis (strain H37 RA; Difco) was added to a concentration of 4 mg ml-1 and solubilized via ultrasound. The autoantigenic MBP peptide Ac1-10 at 4 mg ml-1 in DPBS was emulsified 1:1 with the IFA/M. tuberculosis mixture. Each mice was injected with 100 μl of the emulsion (according to 200 μg peptide) subcutaneous at the base of the tail. At day 1 and 3 after immunization each mouse was intraperitonealy injected with 200 ng pertussis toxin (Calbiochem) in 500 μl DPBS. The clinical symptoms were scored according to Coligan (33)—score: 0, normal; 1, limp tail or hind limb weakness; 2, limp tail and hind limb weakness; 3, partial hind limp paralysis; 4, complete hind limb paralysis; 5, dead or moribund, killed by investigator.

Results

Generation of transgenic mice

We wanted to investigate the influence of an autoantigenic peptide, permanently presented by professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs), on the induction of EAE. Therefore we generated transgenic mice, which dominantly present the autoantigenic peptide MBP1-10 in the context of the murine MHC class II molecule I-Au. To acquire reliable autoantigen presentation, we used a system previously used by other groups to investigate the role of specific peptides in thymic selection (27, 34). We fused the MBP peptide 1-10 and a glycine-serine linker N-terminal to the I-Auβ chain (Fig. 1). The natural N-terminus of the MBP peptide is acetylated and this post-translational modification was shown to be important for binding to I-Au (35, 36). Since it was shown to be a good substitution for the acetylation (35-37), we chose the steric-similar glycine as a replacement. We also placed the first three amino acid residues of the I-Auβ chain N-terminal to the MBP peptide to allow proper cleavage of the DRβ51 signal sequence (27) (Fig. 1). Experiments with the hybridoma cell line 1934.4, specific for I-Au and MBP Ac1-9, showed that such an N-terminal-extended peptide stimulates the hybridoma equally as well as the normal acetylated peptide (data not shown). Since we wanted the MBP-IAu fusion product to be expressed in the natural context of MHC class II expression, we chose the human DRβ51 promoter for the IAuα and the MBP-IAuβ chain. The transgenic constructs were co-injected and we obtained two founder lines with different expression levels of the transgenes, and .

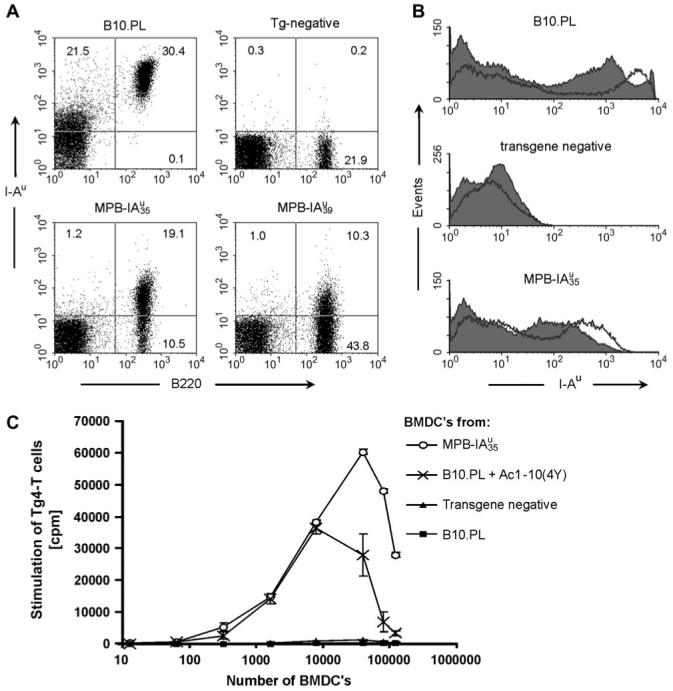

MHC class II-specific expression of the transgenes

To analyze expression of the transgenes we crossed both founder lines on an H-2b background. We stained lymphocytes of these mice with antibodies against I-Au and compared these stainings to lymphocytes from B10.PL (H-2u) mice (Fig. 2). We found typical MHC class II-specific expression on B cells in the LNs (Fig. 2A), spleen and bone marrow (data not shown). Transgenic bone marrow B cells showed up-regulation of the transgenic MBP-IAu at the pre-B cell stage, which is characteristic for MHC class II expression in developing B cells (38) (data not shown). The two transgenic lines differed in their expression level of MBP-IAu. According to FACS analysis expressed the transgene about four times stronger than mice (mean fluorescence intensity of 28 versus 6.9). We also examined BMDCs of mice for expression of the transgenes (Fig. 2B). We found high expression of the transgenic MBP-IAu on BMDCs and its typical MHC class II-specific up-regulation after LPS activation.

Fig. 2.

MHC class II-specific expression of transgenic MBP-IAu in the two founder lines and in vitro activation of Tg4 cells by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. (A) MHC class II-specific expression of transgenic MBP-IAu on LN B cells. FACS analysis of LN cells from B10.PL (H-2u) in comparison to LN cells from transgenic and non-transgenic littermate on an H-2b background, stained with antibodies against I-Au (MKS4-bio/SA-PE) and CD45R (B cells; B220-FITC). Dead cells are excluded from the analysis by propidium iodide (PI) staining. Numbers in the quadrants represent the percentage of cells in the latter. (B) Transgene expression on BMDCs from mice. Dendritic cells were acquired after differentiation of bone marrow cells with GM-CSF. The histograms show FACS analyzes of PI-negative BMDCs after activation (empty) for 24 h with LPS (1 μg ml-1) in comparison to non-activated BMDCs (filled). Transgenic and non-transgenic control mice for the BMDC experiments were on an H-2dxb background. After activation, BMDCs showed different activation makers as size increases, up-regulation of endogenous MHC class II and CD86 (data not shown). (C) LPS-stimulated BMDCs from mice activate Tg4 T cells in vitro. Tg4 LN and spleen cells were depleted from B cells and other MHC class II-positive cells. For each well, 2 × 105 Tg4 Tcells were co-incubated with titrated cell numbers of LPS-activated, irradiated BMDCs (0, 13, 64, 320, 1600, 8000, 40 000, 80 000 and 120 000 BMDCs). After 36 h of co-incubation, [3H]TdR was added and proliferation was measured 24 h later. As positive control BMDCs from B10.PL mice were pulsed 4 h before LPS activation with Ac1-10 (4Y) at 5 μg ml-1 and washed before the proliferation assay to remove residual peptide. The data show mean values of triplicates and the corresponding standard deviations. The experiment was performed twice with similar results.

Activation of Tg4 T cells by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells from transgenic mice

To test whether the transgenes were functionally expressed and that the MBP peptide was presented by the transgenic I-Au molecules, we tested the stimulatory capacity of LPS-activated BMDCs from mice. Due to the high precursor frequency of MBP-specific CD4+ T cells in Tg4 mice, no prior immunization was necessary (24) and therefore we used naive purified Tg4 T cells. We titrated the cell number of transgenic BMDCs in comparison to non-transgenic and peptide-pulsed BMDCs from B10.PL mice. The transgenic BMDCs (H-2dxb background) were highly stimulatory for Tg4 T cells, similar to peptide-pulsed BMDCs from B10.PL mice (Fig. 2C). An allogeneic reaction can be ruled out since the MHC-matched non-transgenic BMDCs did not activate Tg4 T cells at all. This data, together with the following, show that the MBP1-10 peptide in the transgenic mice is presented in a functional and stimulatory manner on the cell surface. Because no antibody is available for the specific MBP-IAu combination, we were not able to show the extent to which the transgenic I-Au molecules are loaded with the covalently bound MBP peptide.

Thymic deletion in double transgenic mice

As the expression of the transgenes should influence thymic selection, we crossed the transgenic lines with Tg4 mice and analyzed the thymi of F1 littermates. The crosses with MBP-IAu mice had an enormous effect on thymus size (not shown), cellularity (Table 1) and on selection of CD4+ thymocytes expressing the transgenic Vβ8.2 chain (Fig. 3). We found a reduction of cellularity from about 54-150 × 106 in Tg4 mice to 0.8-6.7 × 106 in and 1.2-28.4 × 106 in mice. In double transgenic mice, deletion occurred mainly at the double-positive (CD4+CD8+) stage, and in , deletion occurred later during transit into the single-positive stage (Table 1 and Fig. 3B), which correlates well with the different expression levels of the transgenes. The FACS staining in Fig. 3(B) shows a high proportion of single positive (CD4+CD8-) in thymi from double transgenic mice. But due to the strong reduction in thymic cellularity (see legend) the absolute amount of these cells is very low. Additionally we found that expression of the transgenic Vβ8.2 chain in these single-positive (CD4+CD8-) thymocytes of double transgenic mice was very low in comparison to thymocytes from Tg4 mice (Fig. 3B, blue events of region 3). Cells with high-expression of Vβ8.2 were instead found in the double-negative thymocyte population. Figure 3(C) shows that independent of the stage of deletion, both double-positive (CD4+CD8+) and single-positive (CD4+CD8-) thymocytes with high expression of the transgenic Vβ8.2 chain were predominantly deleted. These data show that the transgenic MBP-IAu constructs in both transgenic lines are functionally expressed in the thymus and induce strong central tolerance.

Table 1.

Summary of data to thymic deletion in the different double transgenic mouse lines in comparison to wild-type or single transgenic mice

| Line | Age (weeks) | Thymocytes (×106) | % Thymocytes (DP) CD4+/CD8+ | % Thymocytes Vβ8.2high/CD4+ | % T cells (LN) Vβ8.2+/CD4+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B10.PL | 6 | 176.0 | 83.8 | 3.8 | 9.6 |

| Tg4a | 5 | 85.9 | 57.0 | 20.7 | 48.6 |

| 9 | 150.4 | 70.9 | 16.0 | 30.3 | |

| 12 | 54 | 68.2 | 20.7 | 45.8 | |

| 6 | 6.7 | 0.4 | 1.7 | n.d.b | |

| 9 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 9.0 | 13.0 | |

| 12 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 5.9 | 4.8 | |

| 13 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 9.0 | 3.5 | |

| 5 | 28.4 | 52.2 | 1.3 | 5.5 | |

| 9 | 1.2 | 51.7 | 6.1 | 3.8 | |

| 11 | 4.0 | 9.5 | 3.8 | 9.4 |

Thymocytes from the respective mouse lines of individual animals with the indicated ages were prepared, counted and stained against CD4, CD8 and Vβ8.2 and then analyzed by FACS. The total thymocyte number (cellularity), which is dependent on the age as well as on the expression of the transgenic constructs, is shown in the third column in millions. Columns 4-6 show the relative percentages of the indicated cell populations determined by FACS (of which examples are shown in Fig. 3). Data from individual mice are shown.

Single transgenic littermates of F1-double transgenics.

n.d.: not determined.

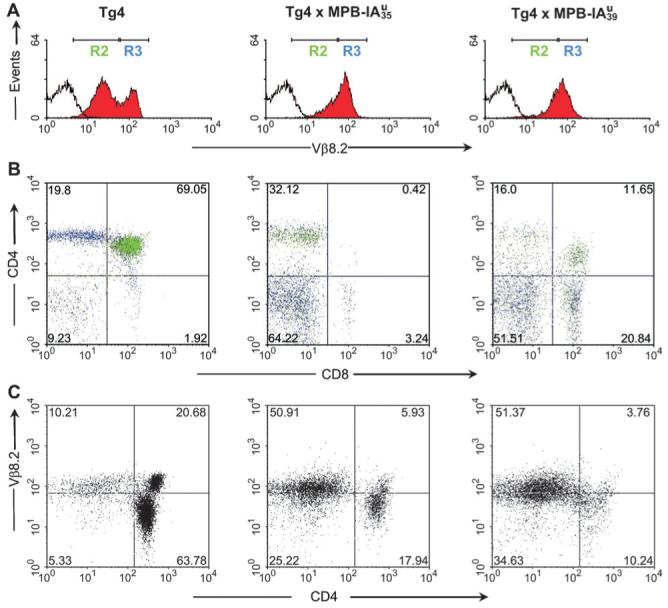

Fig. 3.

Central tolerance induction in double transgenic Tg4 × IAu mice. FACS analysis of thymi from Tg4 and double transgenic mice. Thymocytes were triple stained with CD4-PE, CD8-613 and anti-Vβ8.2-FITC. (A) Histograms show staining for Vβ8.2 (filled red) compared with non-stained cells (empty). The regions R2 and R3 were defined by Vβ8.2 expression: R2 defines cells with low and R3 with high Vβ8.2 expression. (B) Dot blot multicolor analysis of thymocyte CD4 versus CD8 staining. Green dots are cells, which express low Vβ8.2 (from R2) and blue dots are cells with high Vβ8.2 expression (of R3). (C) Deletion of CD4-positive thymocytes with high Vβ8.2 expression. Staining of the transgenic TCR-β chain (Vβ8.2) and CD4. (A-C) All mice were 11-12 weeks old. The total thymocyte cellularity was 54 × 106 for Tg4, 1.4 × 106 for and 4 × 106 for . Numbers in the quadrants represent percentages of cells.

Peripheral CD4 T cells of double transgenic mice express activation markers

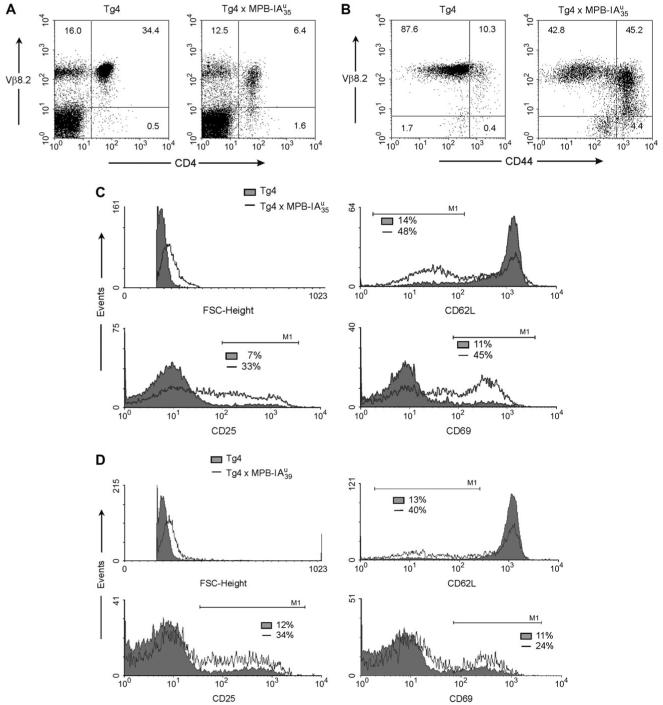

Despite the strong thymic-negative selection we found residual CD4+ T cells in double transgenic mice accounting for 3-14% in lymph the nodes in comparison to 30-50% in Tg4 mice (Table 1 and Fig. 4A). Most of these cells had a down-regulated Vβ8.2 chain and expressed a series of activation markers (Fig. 4). Since allelic exclusion is known to be incomplete for the TCR α chain (39, 40) and it was shown that the expression of secondary Vα chains might rescue thymocytes from negative selection (41), we speculated whether this also was the case for our residual T cells in the double transgenic mice. Unfortunately there is no antibody specific for the transgenic Vα4-chain available. A staining against the endogenous TCR-Vα2 showed that about 37% of CD4+ Vβ8.2+ thymocytes and about 28% of CD4+ Vβ8.2+ LN cells of mice expressed the non-transgenic α chain in comparison to about 6 and 11.4%, respectively, in Tg4 mice. Therefore we assume that the residual T cells in double transgenic animals survive negative selection by expressing other non-transgenic TCR α chains. Despite this putative rescue mechanism we guess that at least half of the cells express the functional TCR specific for MBP-IAu: Figure 4(B) shows that about half the CD4+-LN cells from mice express the activation/memory marker CD44 and that especially these cells display a down-regulated Vβ8.2 expression. Similarly, the expression of the activation markers CD25, CD69, CD62Llo and the higher forward scatter indicate the antigen experience of CD4+ T cells from double transgenic and mice (Fig. 4C and D). It was recently shown that expression of antigens in the thymus induces antigen-specific regulatory CD25+CD4+ T cells (42). Therefore surface expression of CD25 on about 30% of CD4+ cells in double transgenic and (Fig. 4C and D) mice may indicate the presence of a high percentage of regulatory T cells.

Fig. 4.

Reduced number and activation status of peripheral MBP-specific T cells in double transgenic mice. (A-D) FACS analysis of LN cells: (A) Reduction of peripheral CD4+ Tcells and down-regulation of the transgenic Vβ8.2 chain. Staining of Vβ8.2 against CD4. (B) Expression of CD44 on peripheral CD4 T cells. Staining of Vβ8.2 (F23.1-FITC), CD4 (CD4-613) and the activation marker CD44 (CD44-bio/SA-PE). The dot blots show Vβ8.2 against CD44 gated on CD4+ T cells. (C, D) The histograms show the expression of activation markers on CD4-positive, gated cells. Tg4 mice, filled; , empty (C) or , empty (D). Cells were stained for Vβ8.2 (F23.1-FITC), CD4 (CD4-613) and the respective activation marker with biotinylated antibodies followed by SA-PE staining. The numbers show the percentage of cells in the marker region of the respective histogram.

Peripheral T cells of double transgenic mice are refractory to in vitro stimulation

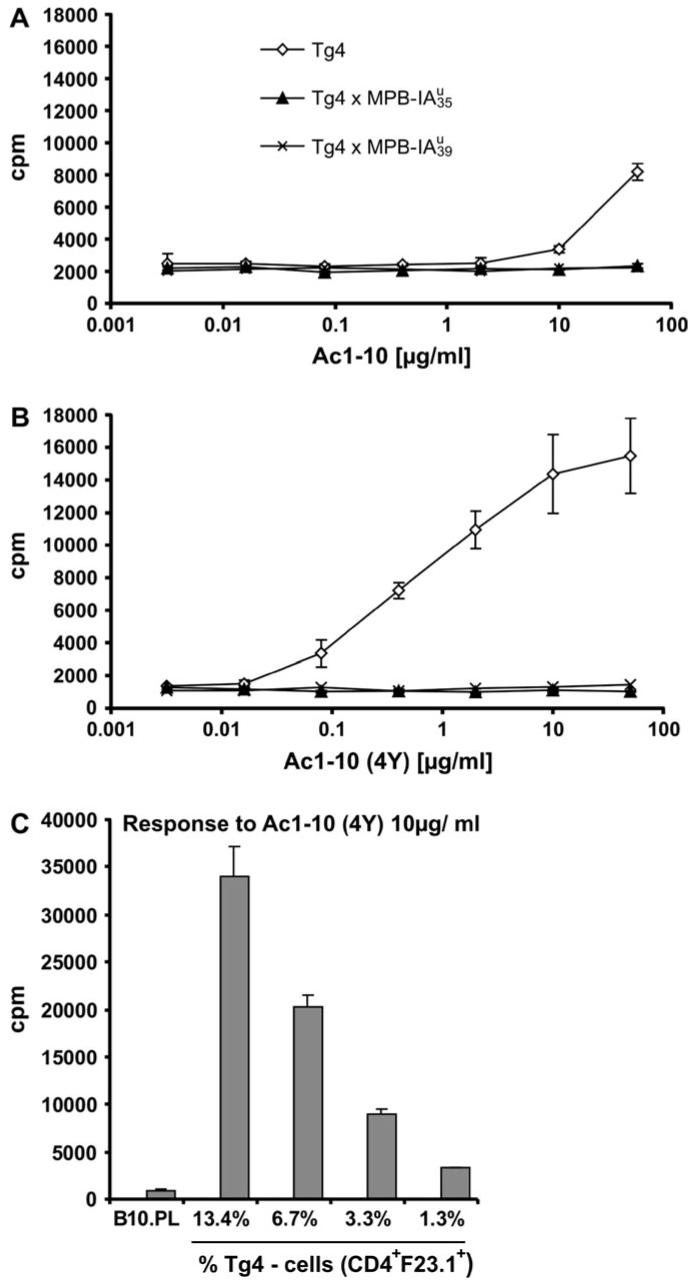

We tested in vitro whether the residual T cells of double transgenic mice could be stimulated with the MBP peptide (Fig. 5). We found that T cells from double transgenic mice of both transgenic lines were completely tolerant to in vitro stimulation either against the natural MBP Ac1-10 or against the higher stimulatory MBP Ac1-10 (4Y) peptide. To show that this tolerance was independent of APCs and of the reduced CD4+ T cell number in double transgenic animals, we stimulated an equal number of CD4+ T cells from Tg4 or , both from an I-Au-negative background, with APCs from B10.PL and Ac1-10 (4Y). Also in this setting we found that the Tg4 T cells respond nicely to peptide stimulation in comparison to complete unresponsiveness of the CD4+ T cells from mice (data not shown). In an additional experiment we titrated the number of transgenic CD4+F23.1+ cells to B10.PL cells from 13.4% down to 1.3% covering percentages of residual CD4+F23.1+ cells found in double transgenics (Fig. 5C). Although a decrease of proliferation was found, the low percentages of 3.3 and 1.3% displayed clear proliferative responses in comparison to the non-reactive B10.PL cells. These experiments exclude that the lack of response by double transgenic splenocytes is due to the low number of residual CD4+F23.1+ cells. This shows that the peripheral Tcell population of double transgenic mice is in vitro tolerant against stimulation by the cognate peptide. We assume that central and peripheral tolerance mechanisms account for this unresponsiveness.

Fig. 5.

T cells from double transgenic mice show diminished proliferative response to autoantigenic MBP peptide; in vitro proliferation assay with splenocytes from Tg4, and mice. To each well containing 3 × 105 naive splenocytes, MBP Ac1-10 (A) or MBP Ac1-10 (4Y) (B) was titrated to be presented by endogenous APCs. Percentage of CD4+ cells of splenocytes in the assay: Tg4, 14%; , 3%; , 4%. All animals were on an H-2dxu background. (C) Low numbers of transgenic CD4+F23.1+ cells from Tg4 mice display proliferative responses. Tg4 splenocytes were titrated to B10.PL splenocytes to the final percentages of transgenic CD4+F23.1+ cells indicated and activated with Ac1-10 (4Y) at 10 μg ml-1. Shown is the mean of triplicates with corresponding standard deviations.

Single transgenic MBP-IAu mice are tolerant to EAE induction

To study whether expression of the transgenic MBP peptide could also influence the wild-type T cell repertoire in non-TCR-transgenic mice, we crossed the transgenic MBP-IAu lines with B10.PL mice and induced active EAE in F1-heterozygotic animals (Table 2, experiment 1). We found that single transgenic mice were almost completely tolerant towards EAE induction and five out of eight mice developed mild signs of EAE, whereas most of the non-transgenic littermates were highly susceptible to EAE. The onset of EAE in mice was very variable ranging from day 18 to 83 post-immunization. EAE duration in these mice was limited to about 3-4 days in comparison to about 10 days or chronicity in non-transgenic littermates (data not shown). These data also show that a diverse wild-type repertoire is tolerized by the transgenic MBP-IAu expression. The slightly higher EAE susceptibility of mice correlates well with the lower transgene expression found in these mice (Fig. 2A).

Table 2.

Summary of EAE in transgenic MBP-IAu mice

| Group | Incidence | Onseta | Mean maximumb | Dead | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1c | ||||||

| Transgene negative (n = 9) | 7/9 | day 20 | (10; 51; 12; 15; 19; 17; 16) | 2.3 | (4; 3; 3; 3; 2; 4; 2) | 0 |

| (n = 7) | 2/7 | day 37 | (15; 59) | 0.3 | (1; 1) | 0 |

| (n = 7) | 4/7 | day 36 | (18; 33; 83; 27) | 0.7 | (1; 2; 1; 1) | 0 |

| Experiment 2d | ||||||

| Tg4 (n = 3) | 3/3 | day 10 | (8; 10; 11) | 4.0 | (5; 4; 3(e)) | 1 |

| (n = 4) | 4/4 | day 47 | (10; 44; 83; 50) | 3.3 | (1; 4; 4; 4) | 0 |

| (n = 2)e | 0/2 | — | — | 0 | (0; 0) | 0 |

| Experiment 3f | ||||||

| Tg4 (n = 8) | 8/8 | day 11 | (days 6-13) | 4.1 | (4; 4; 4; 4; 4; 4; 4; 5) | 1 |

| (n = 7) | 3/7 | day 55 | (67; 45; 53) | 1.7 | (1; 1; 3) | 1 |

| Experiment 4(see Fig. 6) | ||||||

| B10.PL | 6/7 | day 11 | (16; 9; 10; 10; 11; 10) | 2.7 | (3; 4; 1; 0; 4; 5; 2) | 1 |

| B10.PL + CD4+CD25+ | 6/7 | day 11 | (14; 10; 11; 9; 10; 14) | 2 | (1; 3; 2; 3; 4; 0; 1) | 0 |

| B10.PL + CD4+CD25- | 2/7 | day 16 | (21; 12) | 0.6 | (2.5; 2; 0; 0; 0; 0; 0) | 0 |

EAE was induced with MBP Ac1-10 in IFA complemented with heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis and two injections of pertussis toxin as described in Methods and was scored as follows—score: 0, normal; 1, limp tail or hind limb weakness; 2, limp tail and hind limb weakness; 3, partial hind limp paralysis; 4, complete hind limb paralysis; 5, dead or moribund, killed by investigator. Column 2 displays the incidence of diseased mice over the total time of the experiment of the respective group. The mean of disease starting time of the experimental group (onset) and that of individual mice is shown by column 3, whereas the mean maximal score and data of the maximal disease of individual mice are presented in the fourth column. The number of mice, which died by EAE or which were killed with EAE score 5 is indicated in the last column. Specific details of the experiments are given in the respective footnotes.

Mean onset of EAE of mice with EAE. In parenthesis data of single mice with EAE.

Mean maximum of EAE of all mice in one group. In parenthesis data of single mice with EAE.

Duration of experiment, 87 days; all mice, F1 from MBP-IAu × B10.PL; all H-2dxu. Transgene negative: non-transgenic littermates.

Duration of experiment, 106 days; all mice, F1 from ; all H-2dxu. Tg4: single transgenic littermates.

Removed from experiment at day 35 post-immunization.

Duration of experiment, 67 days; all mice, F1 from . Tg4: single transgenic littermates.

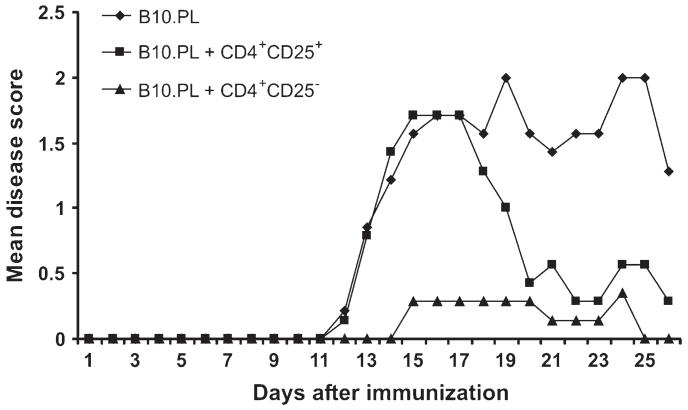

Peripheral T cells of double transgenic mice show regulatory capacity

To find out if a regulatory mechanism contributes to the tolerance induction by the presented antigen in vivo we separately transferred peripheral CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25- T cells from mice into B10.PL mice and induced EAE thereafter. Both cellular fractions reduced the severity of the disease. Surprisingly the transgenic CD4+CD25- T cells showed an even greater suppressive ability than the CD4+CD25+ T cells and nearly completely abolished disease induction (Fig. 6 and Table 2).

Fig. 6.

Regulatory potential of tolerant Tg4 CD4+ T cells. EAE was induced and monitored as described in Materials and Methods 3 days after intravenous transfer of 3 × 105 separated CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25- T cells from peripheral lymphoid organs of non-immunized donor mice. Groups of seven mice each were studied. Data for this experiment are also presented in Table 2 as experiment 4.

Late onset of EAE in double transgenic Tg4 × MBP-IAu mice

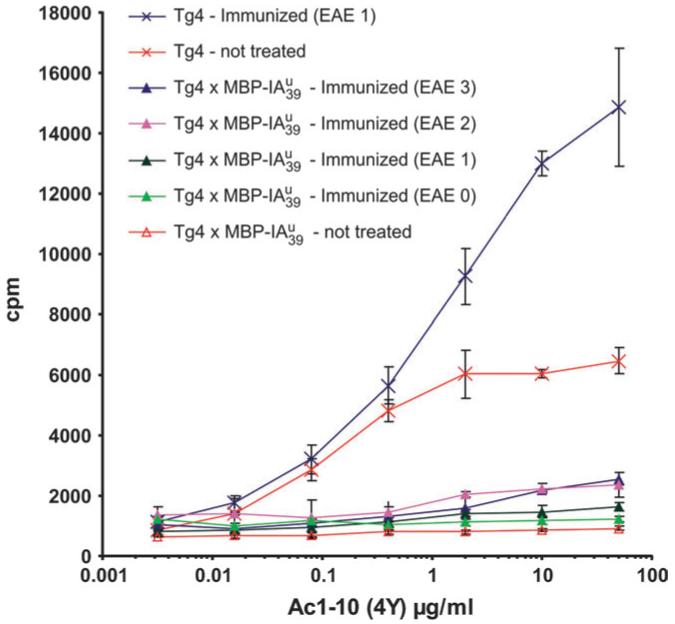

Because of the complete in vitro unresponsiveness of double transgenic mice towards peptide stimulation and the regulatory potential of the transgenic T cells, we also expected these mice to be in vivo tolerant against EAE induction. When we induced EAE in double transgenic mice, one out of seven mice showed an EAE score of 3 and two had symptoms of a score 1 (Table 2, experiment 3). When we induced active EAE in mice, for the first 40 days they seemed to be nearly completely tolerant. Thereafter three out of four mice surprisingly developed severe signs of EAE with a clinical score of 4 at a very late onset time point (day 44-83 post-immunization) (Table 2). Here also the onset varied considerably but the duration of EAE in the diseased mice lasted from about 10 days to chronicity. All single transgenic Tg4 littermates developed fulminant EAE with the typical early onset described for the Tg4-TCR-transgenic animals (32). As we wanted to know whether there was a complete loss of tolerance in diseased mice, we tested the in vitro reactivity of splenocytes from these mice at the end of the EAE experiment (day 106 post-immunization). We did not find a complete loss of in vitro tolerance but rather a very slight reactivity of splenocytes from the two diseased mice at this time point towards Ac1-10 (4Y) (Fig. 7). Therefore we think that the high precursor frequency in and the continued stimulation with the peptide-CFA depot might facilitate the escape of encephalitogenic T cells from tolerance-maintaining mechanisms to develop severe EAE.

Fig. 7.

In vitro recall experiment of double transgenic mice after EAE induction. At the end of the EAE experiment 2 indicated in Table 2 at day 106 post-immunization, splenocytes of individual animals were tested for their in vitro reactivity against MBP Ac1-10 (4Y). Data for the individual mice are presented with their respective EAE score at the time of killing indicated in the graph legend. Diseased double transgenic mice display a slightly enhanced reactivity compared to non-treated double transgenic animals but not a general loss of tolerance.

Discussion

We wanted to investigate the influence of a dominantly presented autoantigen on the susceptibility to EAE. We therefore created two new transgenic mouse lines expressing the MBP peptide 1-10 covalently bound to the MHC class II molecule I-Au. The transgenic construct was MHC class II specifically expressed, stimulated antigen-specific T cells, and induced strong negative selection in thymi of double transgenic mice. Peripheral T cells from double transgenic mice of both lines were in vitro non-reactive to stimulation by the cognate MBP peptide. We found that single transgenic mice were mostly tolerant to EAE induction, whereas double transgenic mice were only incompletely tolerant despite the generation of regulatory T cells. Only very late, after about 40 days of tolerance, did double transgenic mice develop severe EAE.

Similar to us, Vowles et al. expressed the autoantigenic MBP peptide 84-105 under the control of the MHC class II Eα promoter in transgenic SJL mice. As in our single transgenic mice, their transgene also had a profound effect on susceptibility to EAE induced with the MBP peptide (43). As this group did not use TCR-transgenic mice we cannot compare our findings with double transgenic mice to their data. Another group created recombinant adenoviruses expressing MBP1-11 bound to I-Au. The infection with adenoviruses co-expressing these constructs and B7 led to the in vitro activation of the MBP-specific hybridoma 1934.4 and to the in vivo activation of T cells in B10.PL and Pl/J mice (44). This group did not further investigate the influence of such an infection on EAE induction or on thymic selection.

For many potential CNS autoantigens such as MBP, PLP, MOG, αB-crystallin and S100β, expression outside the CNS, in the periphery or in thymus, has been described (18-23, 45, 46). Therefore the view of autoantigens sequestered for the naive immune system must be reconsidered at least for most putative autoantigens. The susceptibility to EAE induced by several different autoantigens or autoantigenic peptides was often explained by “holes” in the tolerance-inducing system. For example susceptibility to EAE in SJL/J mice, induced by PLP, was explained by the absence of thymic expression of its dominant encephalitogenic epitope (20). Another example is the susceptibility of H-2u-positive mice to EAE induced by MBP Ac1-9. It was shown that this peptide especially had a very low affinity to I-Au (36, 47, 48). This was recently explained by the crystal structure of MBP1-11 bound to I-Au showing that Ac1-11 binds in an unusual manner to I-Au occupying with only seven residues one end of the peptide groove. Also unusually the fourth residue P4 lysine was shown to bind in an unfavorable manner into the P6 pocket of I-Au (35). Intraperitoneal injections of peptide analogs with higher affinity to I-Au, for example Ac1-9 (4Y), led to thymic deletion of MBP-specific T cells in TCR-transgenic Tg3 mice, whereas injection of the wild-type peptide led only to limited deletion in the second TCR-transgenic strain Tg4, which expressed the transgene at higher levels than the Tg3 mice (24). This indicated that encephalitogenic T cells in H-2u mice escape from central tolerance induction due to the sub-optimal thymic presentation of the low-affinity peptide, leading to low avidity interactions below the threshold of negative selection (24). Recently Seamons et al. (49) showed that most MBP peptides that are presented by MBP-pulsed splenocytes from B10.PL mice are Ac1-17 or Ac1-18. The explanation for the apparent lack of tolerance against Ac1-11 in these mice was the occurrence of a second high-affinity binding register MBP5-11 with a dissociation half-life of more than 1000 h. This would compete with the binding of the low-affinity Ac1-11-register to I-Au thereby allowing release of Ac1-11-specific T cells from the thymus. In our system the transgenic expression and presentation of this low-affinity peptide covalently bound to I-Au should increase the average avidity to Ac1-10-specific thymocytes and Tcells. Complementing the data from Liu et al. (24) we found massive thymic deletion in double transgenic mice of both lines (Table 1). This shows that even in our strain with lower transgene expression, , in the invariant chain wild-type background, in which replacement of a big part of MHC class II covalent bound peptides has been shown (34), the efficiency of antigen presentation is considerably higher than that found after an intraperitoneal injection of the peptide.

Despite the strong thymic deletion we still found CD4+ cells expressing the transgenic Vβ8.2 chain in the periphery of double transgenic animals. These cells were reduced in number and expressed a series of activation markers, which are typical signs of previous antigen contact. Staining with an antibody against the non-transgenic Vα2 chain indicated that many of the escaped CD4+ Vβ8.2+ T cells might express secondary endogenous Vα chains. Radu et al. (37) stained naive lymphocytes from Tg4 mice with an MBP1-11-IAu tetramer and showed that about 40% of these cells might express endogenous Vα chains. Our result with about 28 and 11% of peripheral CD4+ T cells expressing the non-transgenic Vα2 chain in double transgenic and Tg4 mice, respectively, indicate that a big part of these cells have escaped thymic-negative selection via expression of endogenous TCR Vα chains. This result confirms the finding by others who showed that the cortical thymic expression of an ovalbumin peptide led to receptor editing in mice also transgenic for a TCR specific for this antigen (OT-1) (41). But in contrast to our system, they only found very limited thymic deletion in double transgenic animals.

Jordan et al. (42) have shown that the transgenic expression of an antigen in the thymus induced antigen-specific CD25-positive regulatory T cells (Treg). Others have described the generation of Tregs of a predominant CD25-negative phenotype (50). We found many of the residual CD4+ T cells in double transgenic mice to express CD25. But both CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25- T cells were able to regulate disease severity, the latter even with the greater potential. In our system of thymic and peripheral autoantigen expression, we did not differentiate to what extent these regulatory T cells are thymus-derived or induced in the peripheral lymphoid organs, but we describe here their generation in coexistence with the recessive tolerance mechanism of deletion.

The question arises whether normal organ-specific autoimmune diseases in humans are always the result of the previously mentioned “holes” in the tolerance-maintaining system or rather the result of a loss or the breaking of pre-existing tolerance mechanisms. In most animal systems only short-term experiments lasting maximal several months are performed, whereas the time span in humans from ongoing stimulation until the first signs of autoimmunity is not known.

Our results indicate that pre-existing tolerance, which includes the dominant setup of regulatory T cells, may be lost with time in situations with an elevated frequency of specific T cells and an ongoing stimulation. In this context the outbreak of autoimmune disease may rather be the tilt of a balance between tolerance and autoimmunity than a lack of tolerance described for other systems (above). Our results using double transgenic mice, which succumb to EAE after an extended induction time, suggest that long-term stimulation, for example, due to persistent viral infections, may break pre-existing tolerance mechanisms and lead to organ-specific autoimmune diseases like MS in humans.

Acknowledgements

We thank Yoshinori Fukui for providing us with the DR51 promoter vector and for helpful discussion about the project. We thank John H. Robinson for the MKS4 hybridoma. We thank Harald Kropshofer for help in the planning of the transgenic vector construction and Edward Fellows and Krishnamoorthy Gurumoorthy for reviewing the manuscript. We thank Esmail Rezavandy, Sabine Schmitt, Gorana Hollmann and Georg Pougialis for excellent technical assistance. The work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungs Gemeinschaft (SFB 405), the Welcome Trust and European Union project MUGEN (NOE-LSHG-CT-2005-005203) to G.J.H.

Abbreviations

- Bio

biotin

- BMDC

bone marrow-derived dendritic cell

- CNS

central nervous system

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- FITC

fluorescein thioisocyanate

- GM-CSF

granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- IFA

incomplete freunds adjuvants

- LN

lymph node

- MBP

myelin basic protein

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- PAMP

pathogen-associated molecular pattern

- PI

propidium iodide

- SP

signal peptide

References

- 1.Steinman L. Multiple sclerosis: a coordinated immunological attack against myelin in the central nervous system. Cell. 1996;85:299. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wekerle H. The viral triggering of autoimmune disease. Nat. Med. 1998;4:770. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wekerle H, Linnington H, Lassmamm H, Meyermann R. Cellular immune reactivity within the CNS. Trends Neurosci. 1986;9:271. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohashi PS, Oehen S, Buerki K, et al. Ablation of “tolerance” and induction of diabetes by virus infection in viral antigen transgenic mice. Cell. 1991;65:305. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90164-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oldstone MB, Nerenberg M, Southern P, Price J, Lewicki H. Virus infection triggers insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in a transgenic model: role of anti-self (virus) immune response. Cell. 1991;65:319. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90165-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schönrich G, Kalinke U, Momburg F, et al. Down-regulation of T cell receptors on self-reactive T cells as a novel mechanism for extrathymic tolerance induction. Cell. 1991;65:293. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90163-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferber I, Schönrich G, Schenkel J, Mellor AL, Hämmerling GJ, Arnold B. Levels of peripheral T cell tolerance induced by different doses of tolerogen. Science. 1994;263:674. doi: 10.1126/science.8303275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tafuri A, Alferink J, Möller P, Hämmerling GJ, Arnold B. T cell awareness of paternal alloantigens during pregnancy. Science. 1995;270:630. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Limmer A, Sacher T, Alferink J, Nichterlein T, Arnold B, Hämmerling GJ. A two-step model for the induction of organ-specific autoimmunity. Novartis Found. Symp. 1998;215:159. doi: 10.1002/9780470515525.ch12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Limmer A, Sacher T, Alferink J, et al. Failure to induce organ-specific autoimmunity by breaking of tolerance: importance of the microenvironment. Eur. J. Immunol. 1998;28:2395. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199808)28:08<2395::AID-IMMU2395>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganss R, Limmer A, Sacher T, Arnold B, Hämmerling GJ. Autoaggression and tumor rejection: it takes more than self-specific T-cell activation. Immunol. Rev. 1999;169:263. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matzinger P. Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1994;12:991. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.005015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, et al. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2000;18:767. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barker CF, Billingham RE. Immunologically privileged sites. Adv. Immunol. 1977;25:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams KC, Hickey WF. Traffic of hematogenous cells through the central nervous system. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1995;202:221. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79657-9_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brabb T, von Dassow P, Ordonez N, Schnabel B, Duke B, Goverman J. In situ tolerance within the central nervous system as a mechanism for preventing autoimmunity [In Process Citation] J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:871. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.6.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carrithers MD, Visintin I, Kang SJ, Janeway CA., Jr. Differential adhesion molecule requirements for immune surveillance and inflammatory recruitment. Brain. 2000;123:1092. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.6.1092. see comments. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fritz RB, Kalvakolanu I. Thymic expression of the gollimyelin basic protein gene in the SJL/J mouse. J. Neuroimmunol. 1995;57:93. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(94)00167-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fritz RB, Zhao ML. Thymic expression of myelin basic protein (MBP). Activation of MBP-specific T cells by thymic cells in the absence of exogenous MBP. J. Immunol. 1996;157:5249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein L, Klugmann M, Nave KA, Tuohy VK, Kyewski B. Shaping of the autoreactive T-cell repertoire by a splice variant of self protein expressed in thymic epithelial cells. Nat. Med. 2000;6:56. doi: 10.1038/71540. see comments. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Derbinski J, Schulte A, Kyewski B, Klein L. Promiscuous gene expression in medullary thymic epithelial cells mirrors the peripheral self. Nat. Immunol. 2001;2:1032. doi: 10.1038/ni723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruno R, Sabater L, Sospedra M, et al. Multiple sclerosis candidate autoantigens except myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein are transcribed in human thymus. Eur. J. Immunol. 2002;32:2737. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2002010)32:10<2737::AID-IMMU2737>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delarasse C, Daubas P, Mars LT, et al. Myelin/oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-deficient (MOG-deficient) mice reveal lack of immune tolerance to MOG in wild-type mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:544. doi: 10.1172/JCI15861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu GY, Fairchild PJ, Smith RM, Prowle JR, Kioussis D, Wraith DC. Low avidity recognition of self-antigen by T cells permits escape from central tolerance. Immunity. 1995;3:407. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wraith DC, McDevitt HO, Steinman L, Acha-Orbea H. T cell recognition as the target for immune intervention in autoimmune disease. Cell. 1989;57:709. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90786-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto K, Fukui Y, Esaki Y, et al. Functional interaction between human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II and mouse CD4 molecule in antigen recognition by T cells in HLA-DR and DQ transgenic mice. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180:165. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.165. see comments. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukui Y, Ishimoto T, Utsuyama M, et al. Positive and negative CD4+ thymocyte selection by a single MHC class II/peptide ligand affected by its expression level in the thymus. Immunity. 1997;6:401. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Staerz UD, Rammensee HG, Benedetto JD, Bevan MJ. Characterization of a murine monoclonal antibody specific for an allotypic determinant on T cell antigen receptor. J. Immunol. 1985;134:3994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kappler JW, Skidmore B, White J, Marrack P. Antigen-inducible, H-2-restricted, interleukin-2-producing T cell hybridomas. Lack of independent antigen and H-2 recognition. J. Exp. Med. 1981;153:1198. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.5.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oi VT, Jones PP, Goding JW, Herzenberg LA. Properties of monoclonal antibodies to mouse Ig allotypes, H-2, and Ia antigens. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1978;81:115. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-67448-8_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lutz MB, Kukutsch N, Ogilvie AL, et al. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J. Immunol. Methods. 1999;223:77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu GY, Wraith DC. Affinity for class II MHC determines the extent to which soluble peptides tolerize autoreactive T cells in naive and primed adult mice—implications for autoimmunity. Int. Immunol. 1995;7:1255. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.8.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coligan JE. Current Protocols in Immunology. J. Wiley & Sons; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ignatowicz L, Kappler J, Marrack P. The repertoire of T cells shaped by a single MHC/peptide ligand. Cell. 1996;84:521. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He XL, Radu C, Sidney J, Sette A, Ward ES, Garcia KC. Structural snapshot of aberrant antigen presentation linked to autoimmunity: the immunodominant epitope of MBP complexed with I-Au. Immunity. 2002;17:83. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wraith DC, Smilek DE, Mitchell DJ, Steinman L, McDevitt HO. Antigen recognition in autoimmune encephalomyelitis and the potential for peptide-mediated immunotherapy. Cell. 1989;59:247. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radu CG, Anderton SM, Firan M, Wraith DC, Ward ES. Detection of autoreactive Tcells in H-2(u) mice using peptide-MHC multimers [In Process Citation] Int. Immunol. 2000;12:1553. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.11.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tarlinton D. Direct demonstration of MHC class II surface expression on murine pre-B cells. Int. Immunol. 1993;5:1629. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.12.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heath WR, Carbone FR, Bertolino P, Kelly J, Cose S, Miller JF. Expression of two T cell receptor alpha chains on the surface of normal murine T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 1995;25:1617. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Padovan E, Casorati G, Dellabona P, Meyer S, Brockhaus M, Lanzavecchia A. Expression of two Tcell receptor alpha chains: dual receptor T cells. Science. 1993;262:422. doi: 10.1126/science.8211163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGargill MA, Derbinski JM, Hogquist K. Receptor editing in developing T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2000;1:336. doi: 10.1038/79790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jordan MS, Boesteanu A, Reed AJ, et al. Thymic selection of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells induced by an agonist self-peptide. Nat. Immunol. 2001;2:301. doi: 10.1038/86302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vowles C, Chan VS, Bodmer HC. Subtle effects on myelin basic protein-specific T cell responses can lead to a major reduction in disease susceptibility in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 2000;165:75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen J, Huber BT, Grand RJ, Li W. Recombinant adenovirus coexpressing covalent peptide/MHC class II complex and B7-1: in vitro and in vivo activation of myelin basic protein-specific T cells. J. Immunol. 2001;167:1297. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pribyl TM, Campagnoni CW, Kampf K, et al. The human myelin basic protein gene is included within a 179-kilobase transcription unit: expression in the immune and central nervous systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:10695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pribyl TM, Campagnoni C, Kampf K, Handley VW, Campagnoni AT. The major myelin protein genes are expressed in the human thymus. J. Neurosci. Res. 1996;45:812. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960915)45:6<812::AID-JNR18>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fairchild PJ, Wildgoose R, Atherton E, Webb S, Wraith DC. An autoantigenic T cell epitope forms unstable complexes with class II MHC: a novel route for escape from tolerance induction. Int. Immunol. 1993;5:1151. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.9.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mason K, Denney DW, Jr., McConnell HM. Myelin basic protein peptide complexes with the class II MHC molecules I-Au and I-Ak form and dissociate rapidly at neutral pH. J. Immunol. 1995;154:5216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seamons A, Sutton J, Bai D, et al. Competition between two MHC binding registers in a single peptide processed from myelin basic protein influences tolerance and susceptibility to autoimmunity. J. Exp. Med. 2003;197:1391. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Apostolou I, Sarukhan A, Klein L, von Boehmer H. Origin of regulatory T cells with known specificity for antigen. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:756. doi: 10.1038/ni816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]