Abstract

Objectives To identify factors that predict repeat admission to hospital for adverse drug reactions (ADRs) in older adults.

Design Population based retrospective cohort study.

Setting All public and private hospitals in Western Australia.

Participants 28 548 patients aged ≥60 years with an admission for an ADR during 1980-2000 followed for three years using the Western Australian data linkage system.

Results 5056 (17.7%) patients had a repeat admission for an ADR. Repeat ADRs were associated with sex (hazard ratio 1.08, 95% confidence interval 1.02 to 1.15, for men), first admission in 1995-9 (2.34, 2.00 to 2.73), length of hospital stay (1.11, 1.05 to 1.18, for stays ≥14 days), and Charlson comorbidity index (1.71, 1.46 to 1.99, for score ≥7); 60% of comorbidities were recorded and taken into account in analysis. In contrast, advancing age had no effect on repeat ADRs. Comorbid congestive cardiac failure (1.56, 1.43 to 1.71), peripheral vascular disease (1.27, 1.09 to 1.48), chronic pulmonary disease (1.61, 1.45 to 1.79), rheumatological disease (1.65, 1.41 to 1.92), mild liver disease (1.48, 1.05 to 2.07), moderate to severe liver disease (1.85, 1.18 to 2.92), moderate diabetes (1.18, 1.07 to 1.30), diabetes with chronic complications (1.91, 1.65 to 2.22), renal disease (1.93, 1.71 to 2.17), any malignancy including lymphoma and leukaemia (1.87, 1.68 to 2.09), and metastatic solid tumours (2.25, 1.92 to 2.64) were strong predictive factors. Comorbidities requiring continuing care predicted a reduced likelihood of repeat hospital admissions for ADRs (cerebrovascular disease 0.85, 0.73 to 0.98; dementia 0.62, 0.49 to 0.78; paraplegia 0.73, 0.59 to 0.89).

Conclusions Comorbidity, but not advancing age, predicts repeat admission for ADRs in older adults, especially those with comorbidities often managed in the community. Awareness of these predictors can help clinicians to identify which older adults are at greater risk of admission for ADRs and, therefore, who might benefit from closer monitoring.

Introduction

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are a major public health problem in older populations.1 2 3 In Western countries, ADRs cause 3-6% of all hospital admissions1 2 3 and are responsible for about 5-10% of inpatient costs.4 5 6 We have previously reported that repeat ADRs resulting in either hospital admission or extended hospital stay increased at a greater rate than first time ADRs in older adults from 1980-2003. Furthermore, in Western Australia by 2003 over 30% of all ADRs were repeat ADRs.7

Despite concerns that ADRs represent an important medical problem in older people, the predictive factors are still poorly understood. Older patients are vulnerable to ADRs because of the multiple drugs that they receive to manage chronic diseases and also because of changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.8 9 Risk factors reported to be independently associated with ADRs have included advancing age, sex, comorbidity, multiple drug regimens, inappropriate use of medication, alcohol intake, poor cognitive function, and depression.4 10 11 12 13 14 15 There is currently no consensus on which factors have the greatest impact.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study based on a state-wide population of patients to investigate whether or not comorbid conditions, age and other demographic factors, and drug category are associated with a repeat admission for ADRs in people aged ≥60.

Methods

Study setting and population

We used administrative data from all public and private hospitals in Western Australia, a state with a population of 2.09 million in 2007.16 The study population consisted of all residents aged ≥60 with a hospital admission related to an ADR identified through the data linkage system. This system links state-wide administrative health data at the individual level using probabilistic matching of patients’ names and other identifiers with clerical review of doubtful matches. It includes links between seven core datasets, of which the statutory death registry from 1969 and the hospital morbidity data system (HMDS) from 1970 form the main parts.17 We used extracts of linked hospital morbidity records and death records, with encryption to protect the identity of individual patients. The data were extracted in February 2005.

The hospital morbidity data system contained information on encrypted patient identification and episode number; age, sex, indigenous status, and postcode; date of admission and date of separation (that is, transfer, discharge, or inpatient death); international classification of diseases (ICD) codes for the main diagnosis and up to 19 additional diagnoses for up to four external causes (E codes), and for the main procedure and up to 10 additional procedures; type of hospital attended (public, private, other), admission type (emergency or elective), and payment classification. We used ICD-9 for 1980-7,18 ICD-9-CM for 1988-June 1999,19 and ICD-10-AM from July 1999 onwards.20 Data from the death records included encrypted patient identification, age, sex, indigenous status, primary cause of death, date of death, and postcode. We extracted linked hospital and death records for all patients aged ≥60 with an admission for ADR in 1980-2003 in Western Australia. In an assessment of the technical performance of the linkage system in finding true matches between records, both the proportion of invalid links (false positives) and of missed links (false negatives) was estimated to be 0.11%.17

Definition of ADR and identification of patients

We included all ADRs that resulted in hospital admission or that occurred while patients were in hospital and extended the length of hospital stay. An ADR event was defined as any hospital separation with an ICD E code indicating that either the admission or extended hospital stay was because of the adverse effects of drugs, medicines, and biological substances in therapeutic use: E930–E949 (ICD-9 and ICD-9-CM) or Y40–Y59 (ICD-10-AM). The codes included any adverse effect caused by correct use of drugs, medicines, or biological substances properly administered in therapeutic or prophylactic doses, excluding errors in the technique of administration of drugs, intentional and unintentional overdose, and abuse of a drug. Thus, our definition of ADRs was consistent with the more recent and clearer version: “An appreciably harmful or unpleasant reaction, resulting from an intervention related to the use of a medicinal product, which predicts hazard from future administration and warrants prevention or specific treatment, or alteration of the dosage regimen, or withdrawal of the product.”21 An ADR hospital episode was defined as a period of continuous treatment for an ADR in one or more hospitals, as a person might have been transferred from one hospital to another before they were discharged. We checked all records for transfers between hospitals and, where they existed, combined the admissions into a single “episode” for analysis.

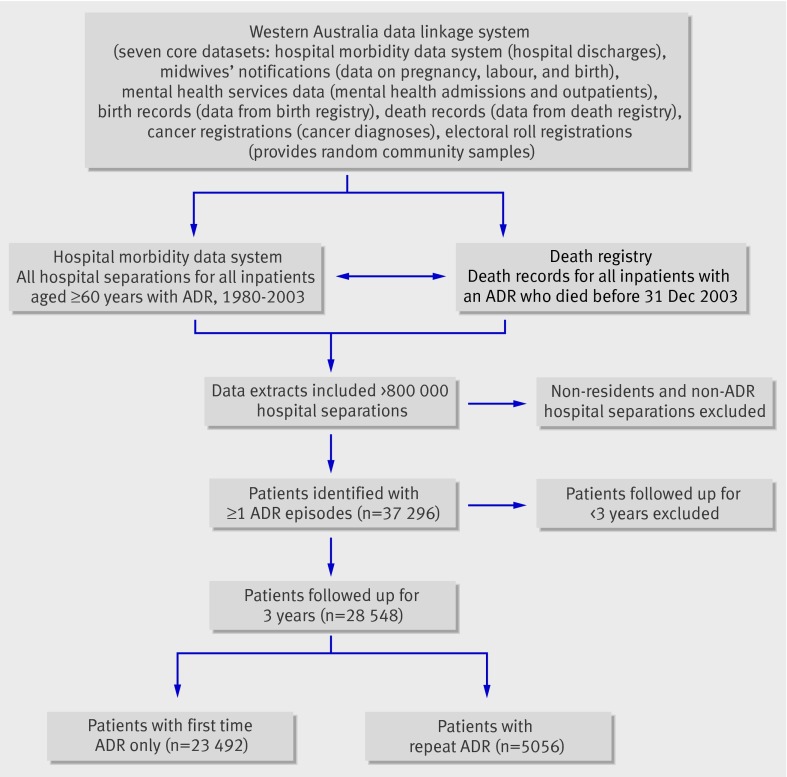

To ensure correct identification of first time ADRs, we initially examined all admissions of the patients dating back to 1970. We included 803 732 hospital separations and audited these records to ensure that each patient met the selection criteria. We excluded people who were not residents of Western Australia and those with hospital episodes unrelated to ADRs. There were 37 296 patients who lived and were treated in Western Australia and had at least one admission episode for an ADR. Each patient’s first ADR record was identified, thereby distinguishing first time from repeat episodes. We included 28 548 patients with a first time ADR in 1980-2000 as a cohort and followed them up for three years. The figure shows the process of selecting patients for the study.

Process of selecting patients for study from the Western Australia data linkage system

Follow-up and outcome measurements

The length of follow-up was the time in days from hospital separation for the first time ADR episode (time zero) to the date of a second separate admission for an ADR or, in the absence of a repeat event within three years, to the date of the third anniversary from time zero or date of death if within three years (censored).

We identified the drugs responsible for first time ADRs from the E codes on the hospital morbidity data system. In the 3.9% of all instances when multiple drugs were thought to be responsible for an ADR we included in the analysis only the drug clinically considered to be primarily responsible. Drugs were grouped into 20 broad categories as defined in ICD-10-AM, with closest possible equivalent specifications for ICD-9 and ICD-9-CM. Table 1 shows the distributions of admissions for first time ADRs according to these drug categories and details the modifications required in the drug categories caused by differences between ICD-9/ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-AM. Table 2 gives more specific details of the top 30 drug groups most often implicated in first time ADRs at the four digit E code level (ICD-9/ICD-9-CM) and three digit Y code level (ICD-10-AM), which accounted for more than 81% of all episodes in the study.

Table 1 .

Drug categories (from ICD external cause codes) responsible for admission for first time adverse drug reaction (ADR) in patients aged ≥60, Western Australia, 1980-2000

| Drug category (as defined in ICD-10-AM) | ICD-9/ICD-9-CM | ICD-10-AM | No (%) of patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic antibiotics* | E930 | Y40 | 2672 (9.4) |

| Other systemic anti-infectives/antiparasitics | E931 | Y41 | 430 (1.5) |

| Hormones (including synthetics and antagonists) | E932 | Y42 | 2174 (7.6) |

| Primarily systemic agents | E933 | Y43 | 2122 (7.4) |

| Agents primarily affecting blood constituents | E934 | Y44 | 2432 (8.5) |

| Analgesics/antipyretics/anti-inflammatory drugs | E935 | Y45 | 4694 (16.4) |

| Antiepileptics/antiparkinsonian drugs | E936 | Y46 | 1121 (3.9) |

| Sedatives, hypnotics, antianxiety drugs | E937 | Y47 | 406 (1.4) |

| Anaesthetics and therapeutic gases | E938 | Y48 | 414 (1.5) |

| Psychotropic drugs† | E939 | Y49 | 1534 (5.4) |

| Central nervous system stimulants | E940 | Y50 | 18 (0.1) |

| Drugs primarily affecting autonomic nervous system‡ | E941 | Y51 | 476 (1.7) |

| Agents primarily affecting cardiovascular system | E942 | Y52 | 5576 (19.5) |

| Agents primarily affecting gastrointestinal system | E943 | Y53 | 252 (0.9) |

| Agents affecting water balance/minerals/uric acid§ | E944 | Y54 | 2024 (7.1) |

| Agents affecting muscles/respiratory system | E945 | Y55 | 563 (2.0) |

| Topical agents affecting skin, eyes, ENT, dental | E946 | Y56 | 577 (2.0) |

| Other and unspecified drugs and medicines | E947 | Y57 | 982 (3.4) |

| Bacterial vaccines | E948 | Y58 | 16 (0.1) |

| Other and unspecified vaccines/biologicals | E949 | Y59 | 65 (0.2) |

| Total | 28 548 (100.0) |

ADR=adverse drug reaction; ICD=International Classification of Diseases; ENT=ear, nose, throat.

*Excludes antineoplastic antibiotics (E930.7) from ICD-9/ICD-9-CM (were added to primarily systemic agents, which include antineoplastics).

†Excludes benzodiazepines (E939.4) from ICD-9/ICD-9-CM (were added to group sedatives, hypnotics, antianxiety drugs, which includes benzodiazepines in ICD-10).

‡Excludes sympatholytics (E941.3) from ICD-9/ICD-9-CM (were added to agents primarily affecting cardiovascular system, which include these in ICD-10).

§Excludes theophylline (E944.1) from ICD-9/ICD-9-CM (was added to agents affecting muscles/respiratory system, which includes antiasthmatics).

Table 2 .

Top 30 drug groups (ICD E codes) most often implicated in admission for first time adverse drug reaction (ADR) in 28 548 patients aged ≥60, Western Australia, 1980-2000

| Drug groups (as defined in ICD-10-AM) | ICD-9/ICD-9-CM | ICD-10-AM | No (%) of patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic antibiotics: | |||

| Penicillins | E930.0 | Y40.0 | 881 (3.1) |

| Unspecified systemic antibiotics | E930.9 | Y40.9 | 569 (2.0) |

| Other systemic antibiotics | E930.8 | Y40.8 | 505 (1.8) |

| Cephalosporins and other β lactams | E930.5 | Y40.1 | 353 (1.2) |

| Hormones (including synthetics and antagonists): | |||

| Glucocorticoids and synthetics | E932.0 | Y42.0 | 1328 (4.7) |

| Insulins and oral antidiabetic drugs | E932.3 | Y42.3 | 416 (1.5) |

| Primarily systemic agents: | |||

| Antineoplastic/immunosuppressive drugs | E933.1/E930.7 | Y43.1-4 | 1980 (6.9) |

| Agents primarily affecting blood constituents: | |||

| Anticoagulants | E934.2 | Y44.2 | 1964 (6.9) |

| Thrombolytic drugs | E934.4 | Y44.5 | 247 (0.9) |

| Analgesics/antipyretics/anti-inflammatory drugs: | |||

| NSAIDs and antirheumatics | E935.6 | Y45.2-4 | 2026 (7.1) |

| Opioids and related analgesics | E935.2 | Y45.0 | 1388 (4.9) |

| Salicylates | E935.3 | Y45.1 | 442 (1.5) |

| 4-aminophenol derivatives (such as paracetamol) | E935.4 | Y45.5 | 361 (1.3) |

| Antiepileptics and antiparkinsonian drugs: | |||

| Hydantoin derivatives | E936.1 | Y46.2 | 408 (1.4) |

| Antiparkinsonian drugs | E936.4 | Y46.7 | 359 (1.3) |

| Other and unspecified antiepileptics | E936.3 | Y46.6 | 302 (1.1) |

| Psychotropic drugs: | |||

| Antidepressants | E939.0 | Y49.0-2 | 596 (2.1) |

| Phenothiazine antipsychotics/neuroleptics | E939.1 | Y49.3 | 365 (1.3) |

| Agents primarily affecting cardiovascular system: | |||

| Cardiac stimulant glycosides/similar drugs | E942.1 | Y52.0 | 1702 (6.0) |

| Other antihypertensive drugs | E942.6 | Y52.5 | 1708 (6.0) |

| Other antidysrhythmic drugs | E942.0 | Y52.2 | 786 (2.8) |

| Coronary vasodilators | E942.4 | Y52.3 | 662 (2.3) |

| Peripheral vasodilators (ICD-9 sympatholytics) | E941.3 | Y52.7 | 269 (0.9) |

| Agents affecting water balance, mineral/uric acid metabolism: | |||

| Loop and other diuretics | E944.4 | Y54.4-5 | 1257 (4.4) |

| Benzothiadiazine derivatives | E944.3 | Y54.3 | 322 (1.1) |

| Uric acid metabolism drugs (such as colchicine) | E944.7 | Y54.8 | 242 (0.8) |

| Agents affecting muscles/respiratory system: | |||

| Antiasthmatics (including theophylline) | E944.1/E945.7 | Y55.6 | 472 (1.7) |

| Topical agents affecting skin, eyes, ENT, dental: | |||

| Local anti-infectives/anti-inflammatory drugs | E946.0 | Y56.0 | 435 (1.5) |

| Other and unspecified drugs and medicines: | |||

| Unspecified drug or medicines | E947.9 | Y57.9 | 555 (1.9) |

| Other drugs or medicines | E947.8 | Y57.8 | 354 (1.2) |

| Total | 23 254 (81.5) | ||

ADR=adverse drug reaction; ICD=International Classification of Diseases; NSAIDs=non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; ENT=ear, nose, throat.

Comorbidity was measured by using the Charlson comorbidity index22 conditions mentioned in the hospital record for the first time ADR, coded to an ICD-9, ICD-9-CM, or ICD-10-AM rubric that were different from the principal index diagnosis. Nineteen fields existed within the hospital morbidity data system for recording comorbid conditions. The performance of the linkage system in adjusting for comorbidty in longitudinal research designs has been previously demonstrated.23 24 We calculated the Charlson score by adding scores assigned to each specific diagnosis, which was generated using the Dartmouth-Manitoba algorithms for ICD coded administrative data.25 26 Table 3 shows Charlson comorbid conditions (with weights) present at the admission for first time ADR.

Table 3.

Charlson comorbidity conditions (with weights) present at admission for first time adverse drug reaction (ADR) in 28 548 patients aged ≥60, Western Australia, 1980-2000

| Charlson comorbid conditions | Weight | No (%) of patients |

|---|---|---|

| Myocardial infarction | 1 | 1556 (5.5) |

| Congestive cardiac failure | 1 | 4745 (16.6) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1 | 1174 (4.1) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1 | 1827 (6.4) |

| Dementia | 1 | 868 (3.0) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1 | 2034 (7.1) |

| Rheumatological disease | 1 | 832 (2.9) |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 1 | 2145 (7.5) |

| Mild liver disease | 1 | 199 (0.7) |

| Diabetes (mild to moderate) | 1 | 2807 (9.8) |

| Diabetes with complications | 2 | 755 (2.6) |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 2 | 864 (3.0) |

| Renal disease | 2 | 1418 (5.0) |

| Any malignancy, including lymphoma/leukaemia | 2 | 3349 (11.7) |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 3 | 108 (0.4) |

| Metastatic solid tumour | 6 | 1518 (5.3) |

| AIDS | 6 | 5 (0.0) |

We assigned a socioeconomic disadvantage score for each patient by transforming residential postcode into numerical values of the index of relative socioeconomic disadvantage compiled from the 1986, 1991, 1996, and 2001 Australian censuses and applied to 1980-8, 1989-93, 1994-8, and 1999-2003, respectively.27 The index was developed by the Australian Bureau of Statistics and consists of four variables that reflect or measure relative disadvantage, including low income, low educational attainment, high unemployment, and low skilled occupation; it has been used extensively in public health research.27 The continuous values of the indexes were then partitioned into fifths.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 12.0.1 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). We used the independent samples t test for continuous variables and a χ2 test for categorical variables to compare characteristics between patients with first time only and repeat ADR episodes. Variables associated with first time admissions for an ADR were used for univariate and multivariate analysis. Univariate analysis was undertaken to screen for potentially important variables to be used in the subsequent multivariate analysis. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were fitted by using all variables included as main effects terms, and we performed corresponding linear trend tests. When assessing each drug category, we fitted the Cox regression models using deviation coding, which compared the effect on repeat ADRs of each first time drug category with the average risk of all 20 drug categories. We obtained hazard ratios and associated 95% confidence intervals after adjusting for age, sex, indigenous status, residential locality, socioeconomic disadvantage, admission type, hospital type, length of hospital stay, calendar period of ADR, Charlson comorbidity index, and drug categories. Other studies have identified these variables as those influencing the risk of first time ADRs,10 11 12 13 14 15 and they were significant predictors of repeat ADRs based on the preceding univariate analysis. To assess potential for survival bias, we separately analysed data from all patients and from a subset that excluded those who died in the three year follow-up period.

Results

Results using data from all patients were similar to those obtained when we excluded patients who died in the follow-up period. We have therefore reported only the results from analyses that included all patients. Within the first three years of follow-up, 5056 patients (17.7%) experienced a repeat admission for an ADR. Table 4 presents unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios for repeat ADRs for selected characteristics in the participants. The adjusted hazard ratios for repeat ADRs were 1.08 (95% confidence interval 1.02 to 1.15) for men, 0.87 (0.80 to 0.93) for private hospital admissions, 1.11 (1.05 to 1.18) for length of hospital stay ≥14 days, 2.34 (2.00 to 2.73) for admission in 1995-9 compared with the earliest time period, and 1.71 (1.46 to 1.99) for a Charlson comorbidity index score ≥7, with a significant linear trend across quantitative or ordinal quantitative variables. Residential location in the metropolitan area (1.10, 1.01 to 1.19) was marginally significant (P=0.03). There was no significant effect on repeat ADRs for age, indigenous status, type of admission, and socioeconomic disadvantage.

Table 4.

Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (with 95% confidence intervals) of repeat adverse drug reaction (ADRs) for selected characteristics in older adults

| Characteristics at first admission for ADR | First time ADR only (n=23 492) | Repeat ADR (n=5056) | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value* | HR (95% CI)† | P value* | ||||

| Age at admission (years): | |||||||

| 60-64 | 3226 | 790 | 1.00‡ | 0.18 | 1.00‡ | 0.39 | |

| 65-69 | 3830 | 870 | 0.96 (0.87 to 1.05) | 0.97 (0.88 to 1.07) | |||

| 70-74 | 4697 | 982 | 0.90 (0.82 to 0.99) | 0.93 (0.84 to 1.02) | |||

| 75-79 | 4647 | 1009 | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.04) | 0.99 (0.91 to 1.10) | |||

| ≥80 | 7092 | 1405 | 0.92 (0.84 to 1.00) | 0.96 (0.87 to 1.05) | |||

| Sex: | |||||||

| Female | 13 264 | 2810 | 1.00‡ | <0.001 | 1.00‡ | <0.01 | |

| Male | 10 228 | 2246 | 1.13 (1.07 to 1.19) | 1.08 (1.02 to 1.15) | |||

| Indigenous status: | |||||||

| Non-Aboriginal/TSI | 23 288 | 5006 | 1.00‡ | 0.34 | 1.00‡ | 0.85 | |

| Aboriginal/TSI | 204 | 50 | 1.15 (0.87 to 1.52) | 1.03 (0.77 to 1.37) | |||

| Residential locality: | |||||||

| Regional/rural area | 3936 | 847 | 1.00‡ | 0.53 | 1.00‡ | 0.03 | |

| Metropolitan Perth | 19 556 | 4209 | 1.02 (0.95 to 1.10) | 1.10 (1.01 to 1.19) | |||

| Admission type: | |||||||

| Elective | 6469 | 1405 | 1.00‡ | 0.75 | 1.00‡ | 0.13 | |

| Emergency | 17 007 | 3648 | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.07) | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.12) | |||

| Type of hospital attended: | |||||||

| Public | 19 542 | 4063 | 1.00‡ | <0.001 | 1.00 | <0.001 | |

| Private | 3275 | 930 | 1.32 (1.23 to 1.42) | 0.87 (0.80 to 0.93) | |||

| Other | 675 | 63 | 0.41 (0.32 to 0.53) | 0.80 (0.61 to 1.04) | |||

| Length of hospital stay (days): | |||||||

| <14 | 15 803 | 3408 | 1.00‡ | <0.001 | 1.00‡ | 0.001 | |

| ≥14 | 7689 | 1648 | 1.14 (1.08 to 1.21) | 1.11 (1.05 to 1.18) | |||

| Socioeconomic disadvantage (fifths): | |||||||

| 1 (most) | 4671 | 982 | 1.00‡ | <0.001 | 1.00‡ | 0.15 | |

| 2 | 5495 | 1055 | 0.92 (0.85 to 1.01) | 0.90 (0.83 to 0.99) | |||

| 3 | 3184 | 710 | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.16) | 0.99 (0.90 to 1.09) | |||

| 4 | 3365 | 733 | 1.04 (0.95 to 1.15) | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.04) | |||

| 5 (least) | 6752 | 1575 | 1.11 (1.02 to 1.20) | 0.94 (0.87 to 1.02) | |||

| Calendar period of ADR: | |||||||

| 1980-4 | 2097 | 183 | 1.00‡ | <0.001 | 1.00‡ | <0.001 | |

| 1985-9 | 3540 | 459 | 1.48 (1.25 to 1.76) | 1.44 (1.21 to 1.72) | |||

| 1990-4 | 5915 | 780 | 1.53 (1.31 to 1.80) | 1.52 (1.29 to 1.79) | |||

| 1995-9 | 9409 | 1946 | 2.37 (2.03 to 2.75) | 2.34 (2.00 to 2.73) | |||

| Charlson comorbidity index score: | |||||||

| 0 | 9511 | 1719 | 1.00‡ | <0.001 | 1.00‡ | <0.001 | |

| 1-2 | 10 220 | 2396 | 1.46 (1.38 to 1.56) | 1.30 (1.22 to 1.38) | |||

| 3-4 | 2262 | 579 | 1.86 (1.69 to 2.04) | 1.42 (1.29 to 1.57) | |||

| 5-6 | 563 | 151 | 2.82 (2.38 to 3.33) | 2.04 (1.72 to 2.42) | |||

| ≥7 | 936 | 211 | 3.10 (2.68 to 3.58) | 1.71 (1.46 to 1.99) | |||

TSI=Torres Strait Islander.

*Test for trend or standard P value across quantitative or ordinal quantitative variables.

†Estimates from Cox regression model included terms for age (continuous), sex (female, male), indigenous status (non-Aboriginal, Aboriginal), residence (regional/rural area, metropolitan), admission type (elective, emergency), type of hospital attended (public, private, other), length of stay (continuous), socioeconomic disadvantage (fifths), calendar period of ADR (continuous), Charlson comorbidity index score (continuous), and drug categories responsible for first time ADR.

‡Reference category.

Table 5 shows the effects of individual Charlson comorbid conditions on repeat ADRs. Compared with patients who had no recorded comorbidity, the analysis identified sizeable adjusted hazard ratios for congestive cardiac failure (1.56, 1.43 to 1.71), peripheral vascular disease (1.27, 1.09 to 1.48), chronic pulmonary disease (1.61, 1.45 to 1.79), rheumatological disease (1.65, 1.41 to 1.92), mild liver disease (1.48, 1.05 to 2.07), mild to moderate diabetes (1.18, 1.07 to 1.30), diabetes with chronic complications (1.91, 1.65 to 2.22), renal disease (1.93, 1.71 to 2.17), any malignancy including lymphoma and leukaemia (1.87, 1.68 to 2.09), moderate to severe liver disease (1.85, 1.18 to 2.92), and metastatic solid tumour (2.25, 1.92 to 2.64). Cerebrovascular disease (0.85, 0.73 to 0.98), dementia (0.62, 0.49 to 0.78), and hemiplegia or paraplegia (0.73, 0.59 to 0.89) were apparently preventive for repeat ADRs. There was no significant relation for myocardial infarction, peptic ulcer disease, or AIDS, although people with AIDS had only two repeat ADRs.

Table 5.

Adjusted hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals for repeat adverse drug reactions (ADRs) for Charlson comorbidity at first admission to hospital for ADR in older adults

| Comorbid conditions | No (%) with first time ADR only | No (%) with repeat ADR | Adjusted HR (95% CI)* | P value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Congestive cardiac failure | 3858 (16.4) | 889 (17.6) | 1.56 (1.43 to 1.71) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 978 (4.2) | 196 (3.9) | 1.27 (1.09 to 1.48) | <0.01 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1537 (6.5) | 497 (9.8) | 1.61 (1.45 to 1.79) | <0.001 |

| Rheumatological disease | 622 (2.6) | 210 (4.2) | 1.65 (1.41 to 1.92) | <0.001 |

| Mild liver disease | 164 (0.7) | 35 (0.7) | 1.48 (1.05 to 2.07) | 0.03 |

| Diabetes (mild to moderate) | 2276 (9.7) | 531 (10.5) | 1.18 (1.07 to 1.30) | <0.01 |

| Diabetes with chronic complications | 507 (2.2) | 248 (4.9) | 1.91 (1.65 to 2.22) | <0.001 |

| Renal disease | 1045 (4.4) | 373 (7.4) | 1.93 (1.71 to 2.17) | <0.001 |

| Any malignancy including lymphoma and leukaemia | 2538 (10.8) | 811 (16.0) | 1.87 (1.68 to 2.09) | <0.001 |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 89 (0.4) | 19 (0.4) | 1.85 (1.18 to 2.92) | <0.01 |

| Metastatic solid tumour | 1245 (5.3) | 273 (5.4) | 2.25 (1.92 to 2.64) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1601 (6.8) | 226 (4.5) | 0.85 (0.73 to 0.98) | 0.02 |

| Dementia | 791 (3.4) | 77 (1.5) | 0.62 (0.49 to 0.78) | <0.001 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 762 (3.2) | 102 (2.0) | 0.73 (0.59 to 0.89) | <0.01 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1332 (5.7) | 224 (4.4) | 0.98 (0.84 to 1.13) | 0.73 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 1847 (7.9) | 298 (5.9) | 1.09 (0.95 to 1.25) | 0.24 |

| AIDS | 3 (<0.1) | 2 (<0.1) | 1.65 (0.41 to 6.71) | 0.48 |

*Estimates from Cox regression models included terms for age (continuous), sex (female, male), indigenous status (non-Aboriginal, Aboriginal), residence (regional/rural area, metropolitan), admission type (elective, emergency), type of hospital attended (public, private, other), length of stay (continuous), socioeconomic disadvantage (fifths), calendar period of ADR (continuous), and drug categories responsible for first-time ADR.

†For hazard ratio (HR), using patients with absent comorbidity as reference category.

Table 6 shows the effect of each drug category (as defined in ICD-10-AM) responsible for first time ADRs. Three drug categories were associated with a greater than average risk of repeat ADRs, with adjusted hazard ratios of 1.51 (1.34 to 1.69) for hormones, 2.12 (1.89 to 2.38) for primarily systemic agents (including antineoplastics, immunosuppressives, and antineoplastic antibiotics), and 4.06 (2.00 to 8.26) for bacterial vaccines. The latter category, however, had low counts for first time and repeat ADRs.

Table 6.

Adjusted hazard ratios (with 95% confidence intervals) of repeat adverse drug reactions (ADRs) for primary drug category responsible for first time ADRs in older adults

| Drug category* | No (%) with first time ADR only | No (%) with repeat ADR | Adjusted HR (95% CI)† | P value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E930/Y40 Systemic antibiotics§ | 2249 (9.6) | 423 (8.4) | 0.81 (0.45 to 1.50) | 0.53 |

| E931/Y41 Other systemic anti-infectives/antiparasitics | 365 (1.6) | 65 (1.3) | 1.02 (0.80 to 1.30) | 0.89 |

| E932/Y42 Hormones (including synthetic and antagonists) | 1649 (7.0) | 525 (10.4) | 1.51 (1.34 to 1.69) | <0.001 |

| E933/Y43 Primarily systemic agents | 1456 (6.2) | 666 (13.2) | 2.12 (1.89 to 2.38) | <0.001 |

| E934/Y44 Agents primarily affecting blood constituents | 1980 (8.4) | 452 (8.9) | 0.93 (0.82 to 1.05) | 0.23 |

| E935/Y45 Analgesics/antipyretics/anti-inflammatory drugs | 4006 (17.1) | 688 (13.6) | 0.76 (0.68 to 0.84) | <0.001 |

| E936/Y46 Antiepileptics/antiparkinsonian drugs | 903 (3.8) | 218 (4.3) | 1.13 (0.97 to 1.32) | 0.12 |

| E937/Y47 Sedatives, hypnotics, antianxiety drugs | 356 (1.5) | 50 (1.0) | 0.74 (0.56 to 0.97) | 0.03 |

| E938/Y48 Anaesthetics, therapeutic gases | 372 (1.6) | 42 (0.8) | 0.52 (0.39 to 0.71) | <0.001 |

| E939/Y49 Psychotropic drugs§ | 1266 (5.4) | 268 (5.3) | 0.96 (0.83 to 1.11) | 0.56 |

| E940/Y50 Central nervous system stimulants | 15 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 0.76 (0.26 to 2.22) | 0.61 |

| E941/Y51 Drugs primarily affecting autonomic nervous system§ | 377 (1.6) | 99 (2.0) | 0.87 (0.71 to 1.07) | 0.18 |

| E942/Y52 Agents primarily affecting cardiovascular system | 4702 (20.0) | 874 (17.3) | 0.93 (0.84 to 1.04) | 0.21 |

| E943/Y53 Agents primarily affecting gastrointestinal system | 220 (0.9) | 32 (0.6) | 0.64 (0.46 to 0.90) | 0.01 |

| E944/Y54 Agents affecting water balance/minerals/uric acid metabolism§ | 1703 (7.2) | 321 (6.4) | 0.99 (0.86 to 1.13) | 0.96 |

| E945/Y55 Agents affecting muscle/respiratory system | 490 (2.1) | 73 (1.4) | 1.01 (0.80 to 1.27) | 0.96 |

| E946/Y56 Topical agents affecting skin, ENT, dental | 496 (2.1) | 81 (1.6) | 0.86 (0.69 to 1.07) | 0.18 |

| E947/Y57 Other and unspecified drugs and medicines | 824 (3.5) | 158 (3.1) | 1.02 (0.86 to 1.21) | 0.80 |

| E948/Y58 Bacterial vaccines | 9 (<0.1) | 7 (0.1) | 4.06 (2.00 to 8.26) | <0.001 |

| E949/Y59 Other and unspecified vaccines/biologicals | 54 (0.2) | 11 (0.2) | 0.96 (0.54 to 1.69) | 0.88 |

*See table 1 for more explicit specifications of ICD-9/ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM code definitions.

†Estimates from Cox regression model included terms for age (continuous), sex (female, male), indigenous status (non-Aboriginal, Aboriginal), residence (regional/rural area, metropolitan), admission type (elective, emergency), type of hospital attended (public, private, other), length of stay (continuous), socioeconomic disadvantage (fifths), calendar period of ADR (continuous), and Charlson comorbidity index score (continuous).

‡P value for each drug category responsible for first time ADR compared with overall effect of drug categories.

§See table 1 for details of modification in drug category between coding systems.

Discussion

Predictive factors for repeat ADR admission

In this population based cohort study of factors that predict repeat admission for ADRs in older adults we found strong evidence that comorbidity from chronic disease rather than advancing age increases their rate of repeat ADRs. Comorbid congestive cardiac failure, diabetes, and peripheral vascular, chronic pulmonary, rheumatological, hepatic, renal, and malignant diseases were all strong predictors of readmissions for ADRs. Our results were consistent with those of earlier studies that a higher Charlson comorbidity index score,4 renal insufficiency,28 and diabetes29 were all risk factors for first time ADRs. We also found that comorbid cerebrovascular disease, dementia, and hemiplegia or paraplegia were associated with a reduced risk of repeat admission for ADRs. First admission for an ADR with a longer hospital stay, admissions in the most recent time period, and male sex also predicted repeat ADR admissions, with admission to private hospitals showing a reduced risk.

ADRs are acknowledged as a major health problem in older people.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 30 A meta-analysis of 68 observational studies reported that the proportion of admissions related to ADRs in older people was four times higher than in younger people.31 We found, however, that advancing age was not independently predictive of repeat admissions related to ADRs in people ≥60. This is consistent with results from previous studies that have examined the independent effects of age on first time ADRs.11 13 Other reported risk factors for first time ADRs include sex, multiple drug regimens, inappropriate use of drugs, alcohol intake, cognitive function, and depression.4 10 11 12 13 14 15 To our knowledge, however, the same risk factors for repeat ADRs have not been previously investigated.

Strengths and limitations

There are several potential explanations for the observed importance of comorbidity. Comorbidity might increase vulnerability to ADRs by impairing body systems—for example, cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal, and hepatic insufficiency can cause changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.28 There might be increased opportunity for drug interactions because of polypharmacy for multiple morbidities. Finally, Berkson’s bias—that is, ADRs are more likely to be identified and diagnosed because of comorbid conditions increasing a person’s contact with the health system.32 A reduced risk of repeat ADRs associated with admission to private hospital might be explained by private patients having generally better health or being socioeconomically advantaged and having stronger social supports. This latter theory, however, is inconsistent with the direct measure of least socioeconomic disadvantage used in this study, which had no effect (hazard ratio 0.94, 0.87 to 1.02).

An important limitation of the study was the absence of data in the hospital morbidity data system on specific drug doses and multiple drug regimens. Nevertheless, we did have information on the drug category primarily responsible for ADRs. We assessed the effect of each drug category by comparing it with the average risk of a repeat ADR from the 20 drug categories responsible for first time ADRs. Hormones, primarily systemic agents, and bacterial vaccines were associated with higher than average risks of repeat ADR, although the numbers in the bacterial vaccines group was small. The higher risk of repeat ADRs from hormones and primarily systemic agents (which include antineoplastic drugs) was expected as severe side effects of these drugs are well known. We examined the diagnoses in patients who had first time ADRs caused by bacterial vaccines and found that nearly 38% of these patients had malignant diseases treated with bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine or other vaccine based immunotherapy. Hence, the increased effect on repeat ADRs observed in the category of bacterial vaccines was probably caused by the concomitant use of antineoplastic agents (part of “primarily systemic agents”). The age standardised rates of all cancers for males and females in 2005 were 356.1 and 260.9 per 100 000 person years, based on a publication from the Western Australia cancer registry.33 Hence, men have a higher incidence of cancer than women in Western Australia, which might explain the observed higher risk of repeat ADRs in men.

The risk of adverse drug effects might increase with increasing drug dose. Although we did not have specific data on drug dose for individuals in our population dataset, we investigated the extent to which doses were prescribed within the normal limits set by the manufacturers as documented in the Monthly Index of Medical Specialities (MIMS-Australia), a database containing approved product information from manufacturers for medicines used in Australia.34 We obtained data on pharmacy dispensing of drugs for discharge and outpatients for the year 2000 from the pharmacy department of one of the teaching hospitals in Western Australia. Analysis of prescribed doses for these drugs showed that nearly all (99.6%) were within the range recommended by the manufacturer as recorded in MIMS Australia.34

The strengths of our study include the cohort design with population based and audited data of high quality,17 thus overcoming issues related to selection and recall biases as well as loss to follow-up. Loss to follow-up would have been small as interstate migration occurred in only 3.5% of residents in Western Australia during the 24 year study period.35 The longitudinal linked data allowed us to identify repeat ADRs in the same patient regardless of changes in the treating hospital. The fact that death records were linked to 69% of participants was consistent with a high level of completeness of follow-up. An important limitation of the study was that the administrative hospital morbidity data system is known to code only 60% of the 17 Charlson comorbid conditions relative to information obtained from chart review.23 False positive diagnoses of comorbid conditions, however, are infrequent for most conditions (range 0-1.5%).23 Although underascertainment of comorbidity is an issue in this study, it seems implausible that the levels of underascertainment would differ substantially between patients with first time ADR only and those with repeat ADRs. Another limitation was that the study focused only on ADRs that either caused hospital admission or extended hospital stay, whereas most ADRs (90%) are fairly minor and occur in the community without admission to hospital.36 ADRs resulting in admission, however, represent the most severe adverse side effects of medication use and lead to considerable morbidity and financial costs. They are thus arguably the most appropriate object of analysis.

As with other studies of this nature, reliability of ascertainment might vary because the presence and diagnosis of an ADR is subject to clinical judgment. The diagnosis of an ADR was made by senior hospital doctors (consultants and registrars) and junior doctors recorded them in text on a structured hospital separation abstract. This step in the process was subject to diagnostic error at a level that is usual in clinical practice. The second step in the process involved coding the text, including external causes or contributing factors, using the ICD-9, ICD-9-CM, or ICD-10-AM coding manuals (for different time periods). This was performed in each of the hospitals by qualified clinical coders who are trained in the use of the ICD codes and were able to obtain additional information from the medical notes as required. The accuracy of clinical coding (including E codes) is routinely checked by coding supervisors as well as by random internal audits.

We found that older adults who experienced an ADR during the most recent study period, 1995-9, had a 2.4-fold greater risk of recurrence than their counterparts in 1980-4. As the study was longitudinal, we need to consider the influence of factors that changed with time. The results are consistent with national drug consumption data that showed an increase in drug exposure in older Australians of 4.7% during 2000-1 alone.37 This increase greatly exceeded population growth, suggesting either a larger population at risk or a higher average level of drug exposure per patient. Our results, derived from population level data, suggest that there exists a strong temporal correlation between repeat ADRs in older adults and greater use of drugs in the community generally.30 38 While efforts to improve the coding of ADRs in hospital morbidity data systems during the observation period might have contributed to some of the observed rise in admissions for ADRs, an earlier validation study in Western Australia, involving a review of hospital charts, found a real increase in hospital morbidity caused by ADRs from 1980 to 1991.39

Conclusions

This population based cohort study found that comorbidity and not advancing age predicted repeat admission for ADRs in patients aged over 60. Comorbid congestive cardiac failure, peripheral vascular, chronic pulmonary, rheumatological, hepatic, renal, and malignant diseases, and diabetes were the comorbid conditions most likely to predict readmission for ADRs from the therapeutic use of drugs. An apparent preventive effect was observed with comorbid cerebrovascular disease, dementia, and hemiplegia or paraplegia, possibly because such patients are under more consistent healthcare supervision. Careful and frequent monitoring of prescribed drugs in older adults with at risk comorbidities might prevent readmissions for ADRs. Evaluation of monitoring programmes delivered by local pharmacists, community nurses, and general practitioners might be the next step towards prevention.

What is already known on this topic

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are a major public health problem in older populations

Repeat ADRs leading to hospital admission have increased at a greater rate than first time ADRs in older adults and by 2003 in Western Australia they had reached 30% of all ADRs

Little information is available on risk factors that predict repeat ADRs

What this study adds

Comorbid congestive cardiac failure, diabetes, peripheral vascular, chronic pulmonary, hepatic, renal, rheumatological, and malignant diseases predict readmission for ADRs

Comorbid cerebrovascular disease, dementia, and paraplegia seem to protect against repeat ADRs, possibly because such patients are under closer healthcare supervision

We thank the Data Linkage Branch, WA Department of Health, in particular, Diana Rosman, manager, for her assistance.

Contributors: MZ and CDJH devised the idea of the study, designed the methods, and raised funding. MZ was responsible for implementing the study and carrying out all the analyses. CDJH supervised the whole study. The following authors assisted in developing and verifying the study components: SDP for the hospital morbidity dataset; FMS for drug categories, modifications to the drug categories between coding systems, and drug dosing investigation; and DBP for comorbidity and ADR hospital episodes. MKB provided statistical advice. MZ prepared the first draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to each section of the final draft of the manuscript. MZ is guarantor.

Funding: MZ is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: This work was approved by the human research ethics committee of the University of Western Australia.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:a2752

References

- 1.Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA 1998;279:1200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, Green C, Scott AK, Walley TJ, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ 2004;329:15-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roughead EE. The nature and extent of drug-related hospitalisations in Australia. J Qual Clin Pract 1999;19:19-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Onder G, Pedone C, Landi F, Cesari M, Della Vedova C, Bernabei R, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of hospital admissions: results from the Italian Group of Pharmacoepidemiology in the Elderly (GIFA). J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1962-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suh DC, Woodall BS, Shin SK, Hermes-De Santis ER. Clinical and economic impact of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients. Ann Pharmacother 2000;34:1373-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore N, Lecointre D, Noblet C, Mabille M. Frequency and cost of serious adverse drug reactions in a department of general medicine. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1998;45:301-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang M, Holman CDJ, Preen DB, Brameld KJ. Repeat adverse drug reactions causing hospitalization in older Australians: a population-based longitudinal study 1980-2003. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007;63:163-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bates DW. Drugs and adverse drug reactions: how worried should we be? JAMA 1998;279:1216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallagher LP. The potential for adverse drug reactions in elderly patients. Appl Nurs Res 2001;14:220-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Field TS, Gurwitz JH, Avorn J, McCormick D, Jain S, Eckler M, et al. Risk factors for adverse drug events among nursing home residents. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:1629-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carbonin P, Pahor M, Bernabei R, Sgadari A. Is age an independent risk factor of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized medical patients? J Am Geriatr Soc 1991;39:1093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klarin I, Wimo A, Fastbom J. The association of inappropriate drug use with hospitalisation and mortality: a population-based study of the very old. JAMA 2005;293:2131-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fialová D, Topinková E, Gambassi G, Finne-Soveri H, Jónsson PV, Carpenter I, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use among elderly home care patients in Europe. JAMA 2005;293:1348-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onder G, Landi F, Della Vedova C, Atkinson H, Pedone C, Cesari M, et al. Moderate alcohol consumption and adverse drug reactions among older adults. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2002;11:385-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onder G, Penninx BW, Landi F, Atkinson H, Cesari M, Bernabei R, et al. Depression and adverse drug reactions among hospitalized older adults. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian demographic statistics, Mar 2007. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2007. (Report No. 3101.0.)

- 17.Holman CDJ, Bass J, Rouse IL, Hobbs MST. Population-based linkage of health records in Western Australia: development of a health services research linked database. Aust N Z J Public Health 1999;23:453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Manual of the international statistical classification of diseases, injuries and causes of death. 9th rev. Geneva: WHO, 1977.

- 19.National Coding Centre. Australian version of the international classification of diseases. 9th rev, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM), 2nd ed. Sydney: National Coding Centre, 1996.

- 20.National Centre for Classification in Health. The international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 10th rev, Australian modification. ICD-10-AM Australian Coding Standards. 2nd ed. Sydney: Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Sydney, 2000.

- 21.Edwards IR, Aronson JK. Adverse drug reactions: definitions, diagnosis, and management. Lancet 2000;356:1255-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Preen DB, Holman CD, Lawrence DM, Baynham NJ, Semmens JB. Hospital chart review provided more accurate comorbidity information than data from a general practitioner survey or an administrative database. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57:1295-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holman CD, Preen DB, Baynham NJ, Finn JC, Semmens JB. A multipurpose comorbidity scoring system performed better than the Charlson index. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:1006-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:1075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sundararajan V, Henderson T, Perry C, Muggivan A, Quan H, Ghali WA. New ICD-10 version of the Charlson comorbidity index predicted in-hospital mortality. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57:1288-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of population and housing: socio-economic indexes for areas. Canberra: ABS, 2006. (Catalogue No: 2912.0, 2012.0, 2039.0.)

- 28.Corsonello A, Pedone C, Corica F, Mussi C, Carbonin P, Antonelli Incalzi R, et al. Concealed renal insufficiency and adverse drug reactions in elderly hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:790-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corsonello A, Pedone C, Corica F, Mazzei B, Di Iorio A, Carbonin P, et al. Concealed renal failure and adverse drug reactions in older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005;60:1147-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burgess CL, Holman CD, Satti AG. Adverse drug reactions in older Australians, 1981-2002. Med J Aust 2005;182:267-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beijer HJ, de Blaey CJ. Hospitalisations caused by adverse drug reactions (ADR): a meta-analysis of observational studies. Pharm World Sci 2002;24:46-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berkson J. Limitations of the application of fourfold table analysis to hospital data. Biometrics Bull 1946;2:47-53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cancer Statistics. Cancer incidence and mortality in Western Australia, 2005. Perth: Western Australian Cancer Registry, 2007. www.health.wa.gov.au/wacr/downloads/rep05a3a.pdf.

- 34.MIMS Australia. MIMS Annual. Australian ed. St Leonards, New South Wales, Australia: MIMS Australia, June 2006.

- 35.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian demographic trends 1997. Canberra: ABS, 1997. (Catalogue No 3102.0.)

- 36.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR, Rothschild J, Debellis K, Seger AC, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. JAMA 2003;289:1107-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing. Cost to government of pharmaceutical benefits. Canberra: Health Access and Financing Division, Department of Health and Ageing, 2003.

- 38.Safety and Quality Council. Second national report on patient safety, improving medication safety. Canberra: Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2002.

- 39.Dawes VP. Poisoning in Western Australia: overview and investigation of therapeutic poisoning in the elderly [MPH dissertation]. Perth: University of Western Australia, 1994. www.populationhealth.uwa.edu.au/download.cfm?DownloadFile=6E400828-96BA-5DAE-B9DDD3B8A49B2483.