Summary

Reports in the clinical literature and studies of fmr-1 knockout mice have led to the hypothesis that, in addition to mental retardation, fragile X syndrome is characterized by a dysregulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function. We have systematically examined this hypothesis by studying the effects of stress on adrenocorticotrophic hormone and corticosterone levels in adult, male fmr1 knockout mice. Initially we determined the circadian rhythms of the plasma hormone levels in both wild type and fmr1 knockout mice and established the optimal time to impose the stress. We found no genotypic differences in the circadian rhythms of either hormone. We studied two types of stressors, immobilization and spatial novelty; spatial novelty was 5 min in an elevated plus-maze. We varied the duration of immobilization and followed the time course of recovery of hormones to their pre-stress levels. Despite the lower anxiety exhibited by fmr-1 knockout mice in the elevated plus maze, hormonal responses to and recovery from this spatial novelty were similar in both genotypes. Further, we found no genotypic differences in hormonal responses to immobilization stress. The results of our study indicate that, in FVB/NJ mice, the hormonal response to and recovery from acute stress is unaltered by the lack of fragile X mental retardation protein.

Keywords: corticosterone, adrenocorticotrophic hormone, circadian rhythm, fragile X, restraint, elevated plus-maze

1. Introduction

Fragile X syndrome (FraX), the most common inherited form of mental retardation, is caused by silencing of a single gene, FMR1, resulting in the absence of the gene product, fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP). FraX phenotype includes cognitive impairments (Rousseau et al., 1994); behavioral dysfunction such as hyperactivity, social anxiety, attention problems and autistic-like behavior (Miller et al., 1999); and some physical abnormalities including macroorchidism in males (Hagerman, 2002). It has also been suggested that boys with FraX have dysregulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis function. Two clinical reports show higher salivary cortisol concentrations in boys with FraX under both normal and stressful conditions (Wisbeck et al., 2000; Hessl et al., 2002), and some data suggest that higher levels of cortisol may be associated with greater severity of behavioral problems (Hessl et al., 2002).

In the fmr1 knockout (KO) mouse model of FraX (Bakker et al., 1994) effects on the HPA axis have also been reported. Immobilization stress effected changes in c-fos expression that varied with duration of stressor, brain region, and genotype (Lauterborn, 2004). In paraventricular nucleus (PVN) c-fos expression was increased similarly in both WT and KO immediately following 30 min of immobilization. After 2 h of immobilization, c-fos was close to pre-stress levels in WT, but remained elevated in KO mice. Serum corticosterone (CORT) levels were elevated after either 30 min or 2 h of immobilization in both genotypes, but effects were greater in KOs after 2 h of stress. Following immobilization stress, serum CORT concentrations recovered more slowly in KO mice (Markham et al., 2006). In addition, one of the mRNAs bound by FMRP is a glucocorticoid receptor mRNA (Miyashiro et al. 2003). Although total glucocorticoid receptor levels appear to be normal in KOs, there is a reduced immunoreactivity in stratum radiatum of the hippocampus (Miyashiro et al. 2003). Normally, circulating glucocorticoids acting on glucocorticoid receptors suppress HPA axis responses through a negative feedback loop. The hippocampus, rich in glucocorticoid receptors, likely plays a major role in the negative feedback. Taken together with results of the clinical studies these findings suggested a dysregulation of the HPA axis in FraX.

Our previous finding that in vivo rates of regional cerebral protein synthesis (rCPS) are increased in selective brain regions in adult fmr1 KO mice (Qin et al., 2005) sparked our interest in a possible dysregulation of HPA axis function. Affected regions in our study included the PVN of the hypothalamus, hippocampus, and the basolateral amygdala, all regions known to be involved in mediating the response to stress. The present study was undertaken to further examine possible dysregulation of HPA axis function in FraX. We have studied the effects of two types of stressors (immobilization and spatial novelty) on stress hormone levels in adult, male fmr1 KO mice. We have varied the duration of the immobilization and followed the time course of recovery of hormones to their pre-stress levels.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Animals

All procedures were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines on the Care and Use of Animals and an animal study protocol approved by the National Institute of Mental Health Animal Care and Use Committee. FVB/NJ-fmr1tm1Cgr breeding pairs (heterozygous females and hemizygous males) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). All mice were housed in a central facility and maintained under controlled conditions of normal humidity and temperature with standard alternating 12-h periods of light (7 am–7 pm) and darkness (7 pm–7 am). Mice were housed 2–4/cage. Food (NIH-31 rodent chow) and water were provided ad libitum. Breeding pairs of heterozygous female and WT males provided offspring in two experimental groups: hemizygous and WT males. Mature mice at 100 ± 10 days of age were studied.

2.2. Genotyping

At the time of weaning we analyzed genomic DNA extracted (Puregene, Gentra Systems, Inc, Minneapolis, MN, USA) from a small section of tail to test for the presence or absence of the knockout allele as previously described (Qin et al., 2002). Primers to screen for the presence or absence of the mutant allele were 5'-ATCTAGTCATGCTATGGATATCAGC-3' and 5'-GTGGGCTCTATGGCTTCTGAGG-3'. The DNA, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) buffer, and TaqDNA polymerase (AmpliTag Gold, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) were combined and subjected to 35 cycles at 95, 62, and 72°C. After amplification, the products were separated by electrophoresis on a 2.0% agarose gel at 100 V for 15 min. The PCR product at ≈800 bp indicated the presence of the null allele.

2.3. Hormone assays

At the outset of the study we determined the optimum conditions for collection of blood for hormone assays. We measured CORT levels in blood samples collected from tail or trunk under different conditions which included with or without light halothane anesthesia, guillotine decapitation v. decapitation with scissors and tapered plastic film tube restraint (DecapiCone, Disposable rodent restrainers, Braintree Scientific INC., MA). We found that rapid decapitation using momentary tapered plastic film tube restraint without any anesthesia is the best way to sample blood (data not shown). This method subjected animals to minimal stress and provided stable CORT measurements.

Following rapid decapitation, core blood was collected into heparinized tubes containing EDTA. Blood was centrifuged to separate the plasma, and plasma samples were stored at −70°C until assayed. Concentrations of ACTH (200 µl) and CORT (5µl) in plasma samples were determined by radioimmunoassay (Corticosterone 125I RIA kit and hACTH 125I RIA kit, MP Biomedicals, LLC, Orangeburg, NY, USA). Samples were counted in a Wallac Wizard Gamma Counter 1480 (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Inter- and intra-assay variability was monitored by the use of a standard. For the CORT assay the coefficient of variation within assays ranged from 4–8% and between assays was 11%. For the ACTH assay the coefficient of variation within assays ranged from 1–10% and between assays was 15%. For a given experiment, hormone levels were assayed in a single batch.

2.4. Circadian fluctuations in HPA hormones

Before embarking on studies in which we perturbed the HPA system, we analyzed the daily rhythms of these hormones in the fmr1 KO and WT mice to test for differences between the two genotypes in circadian fluctuations. We measured baseline plasma concentrations of CORT and ACTH over a 24 h period in adult male WT and KO mice. Animals were acclimated to handling over a period of 4 days. On the fifth day animals were rapidly decapitated, six mice of each genotype per time point, with time points at 2 am, 6 am, 10 am, 2 pm, 6 pm, and 10 pm.

2.5. Acute Stress

Mice that had no previous exposure to these or any other stressful conditions were subjected to one of two stress stimuli:

Restraint stress. Mice were placed in a plastic cylinder (Mouse Restrainer, model 500M, Braintree Scientific, Inc., Braintree, MA, USA) for 30 min or 120 min. Plastic cylinders are configured so that forward, backward, and rotational movement are prevented.

Exposure to spatial novelty. Mice were place in an elevated plus-maze and allowed to explore for 5 min. The apparatus consists of two dark arms (30 × 5 × 15 cm) and two open arms elevated 50 cm from the surface. Initially animals were placed at the center facing an open arm. The time spent in the dark and open arms and the numbers of entrances into dark or open arms were recorded.

Each stress study consisted of four groups of mice of each genotype (10–12 mice per group) studied under the following conditions: 1) unstressed, 2) 30 min or 120 min of restraint stress or 5 min plus-maze, 3) 30 min of recovery from the stress, and 4) 120 min of recovery from the stress. Mice were studied at the nadir of the CORT fluctuation. After the stress, mice were either rapidly decapitated or returned to the home cage for the recovery interval before decapitation. All sampling was done before 11 am.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The effects of genotype and time of day and the effects of genotype and condition following a stressor on CORT and ACTH concentrations were assessed by means of two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests to assess differences between genotypes at each time point in the case of a statistically significant interaction. The effect of genotype on behavior in the elevated plus-maze was assessed by means of Student’s t-test.

3. Results

3.1. Circadian fluctuations in HPA hormones

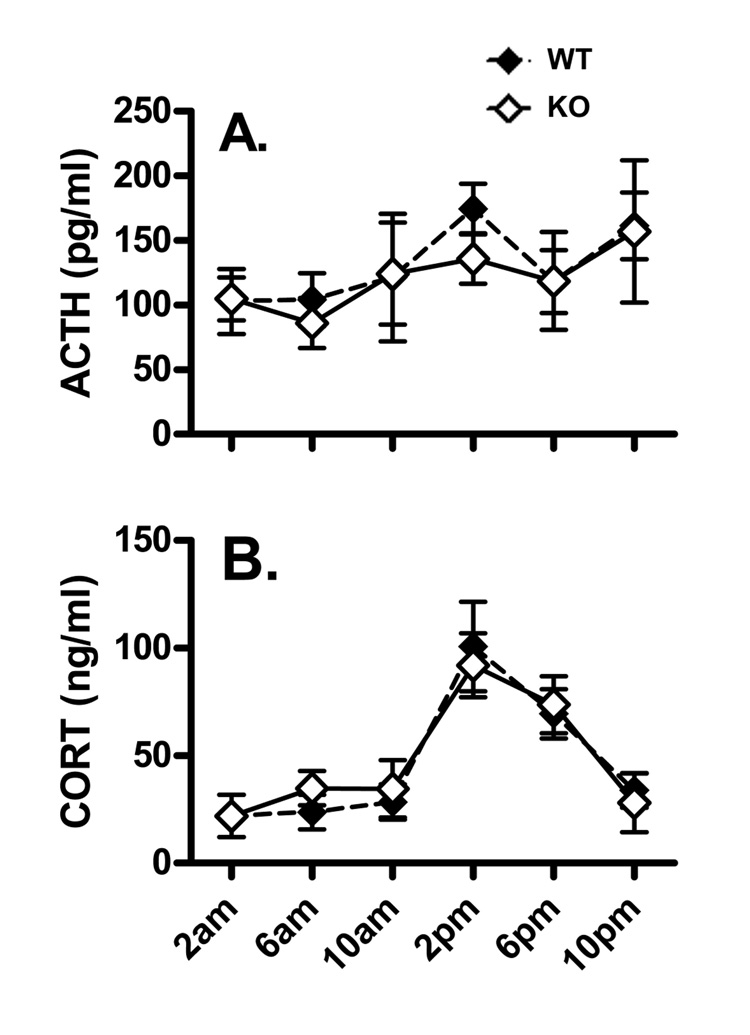

Plasma ACTH and CORT concentrations showed dramatic changes across the 24 h period (Fig. 1). ACTH concentration appears to increase between 6 am and 2 pm, and is lowest at 2 am and 6 am in both genotypes. The highest mean values occurred at 2 pm in WT and at 10 pm in KO. Values of CORT in both WT and KO mice were low between 10 pm and 10 am. The highest measured value occurred at 2 pm in both genotypes and was over three times the baseline value. Between 2 pm and 6 pm, CORT declined by 20–30%. Results were analyzed by means of a two-way ANOVA with genotype and time of day as factors. There were no statistically significant interactions and no effects of genotype for either hormone. The only statistically significant effect was the effect of time of day on CORT concentration (F(5,63)=12.02; P<0.0001). Based on these results we studied mice between 7 and 10 am at the nadir of the CORT rhythm when the HPA axis is most responsive to the effects of stress.

Figure 1.

Effects of time of day on basal concentrations of plasma ACTH (A) and CORT (B) in WT (filled symbols) and KO (open symbols) mice. Values are the means ± SEMs for the following number of animals: A. 6 WT and 6 KO at 6 and10 am, 7 WT and 6 KO at 2, 6, and 10 pm, 7 WT and 5 KO at 2 am; B. 6 WT and 6 KO at 6 and 10 am, 7 WT and 5 KO at 2 pm, 4 WT and 4 KO at 6 pm, 7 WT and 4 KO at 10 pm, 7 WT and 9 KO at 2 am. Shaded areas represent times when the lights in the facility were turned off. Results were analyzed by means of a two-way ANOVA with genotype and time of day as factors. There were no statistically significant interactions and no effects of genotype for either hormone. The only statistically significant effect was the effect of time of day on CORT concentrations (F(5,63)=12.02; P<0.0001).

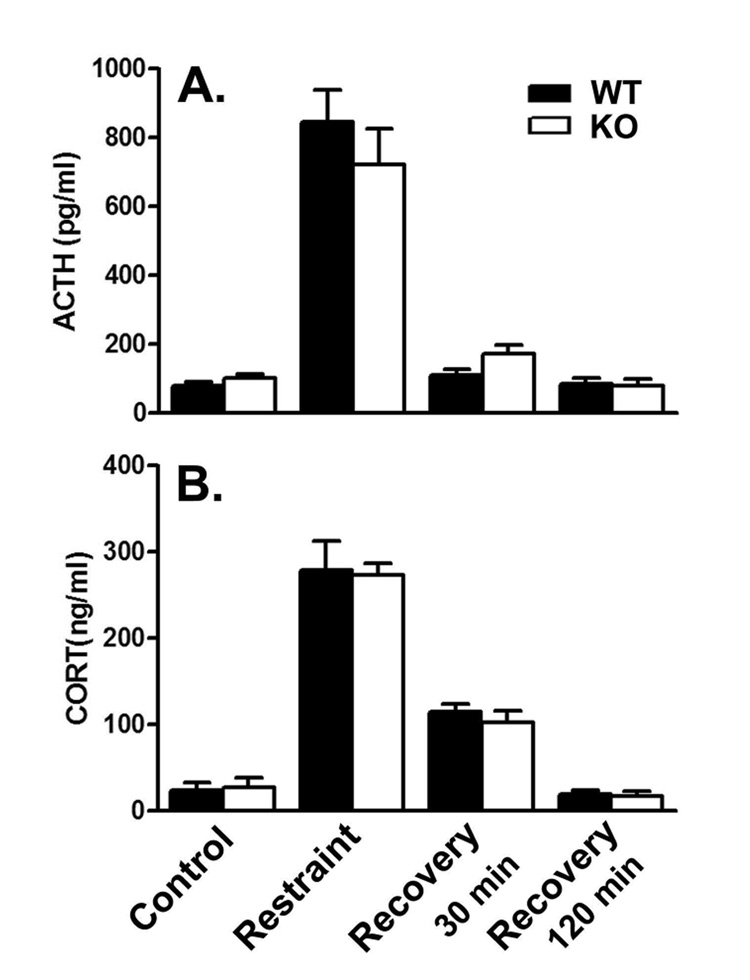

3.2. Restraint stress for 30 min

Mean plasma ACTH concentration increased six fold in KO mice and more than nine fold in WT mice immediately following 30 min of restraint (Fig. 2A). With 30 min of recovery in the home cage, ACTH concentrations were almost returned to baseline and after 120 min were clearly at baseline levels. Mean plasma CORT concentration increased 10–11 times baseline values in both genotypes immediately after 30 min of restraint stress (Fig. 2B). With 30 min of recovery in the home cage, elevations in plasma CORT concentration were reduced to about 3–4 times baseline in both genotypes. After 120 min recovery, plasma CORT concentrations were restored close to baseline. Results were analyzed by means of a two-way ANOVA with genotype and stress condition as factors. There were no statistically significant interactions and no effects of genotype for either hormone. The effects of stress condition were statistically significant for both ACTH (F(3,80)=61.37; P<0.0001) and CORT (F(3,81)=80.44; P<0.0001).

Figure 2.

Recovery from 30 min of restraint stress in WT (filled bars) and KO (open bars) mice: effects on plasma ACTH (A.) and CORT (B.). Values are the means ± SEMs for the following number of animals: A. Control, 6 WT and 6 KO; 30 min restraint, 14 WT and 13 KO; 30 min recovery, 12 WT and 12 KO; 120 min recovery 13 WT and 13 KO; B. Control, 6 WT and 6 KO; 30 min restraint, 13 WT and 12 KO; 30 min recovery, 12 WT and 12 KO; 120 min recovery 14 WT and 13 KO. Results were analyzed by means of a two-way ANOVA with genotype and condition as factors. There were no statistically significant interactions and no effects of genotype for either hormone. Effects of condition were statistically significant for both ACTH (F(3,81)=61.37; P<0.0001) and CORT (F(3,81)=80.44; P<0.0001) concentrations.

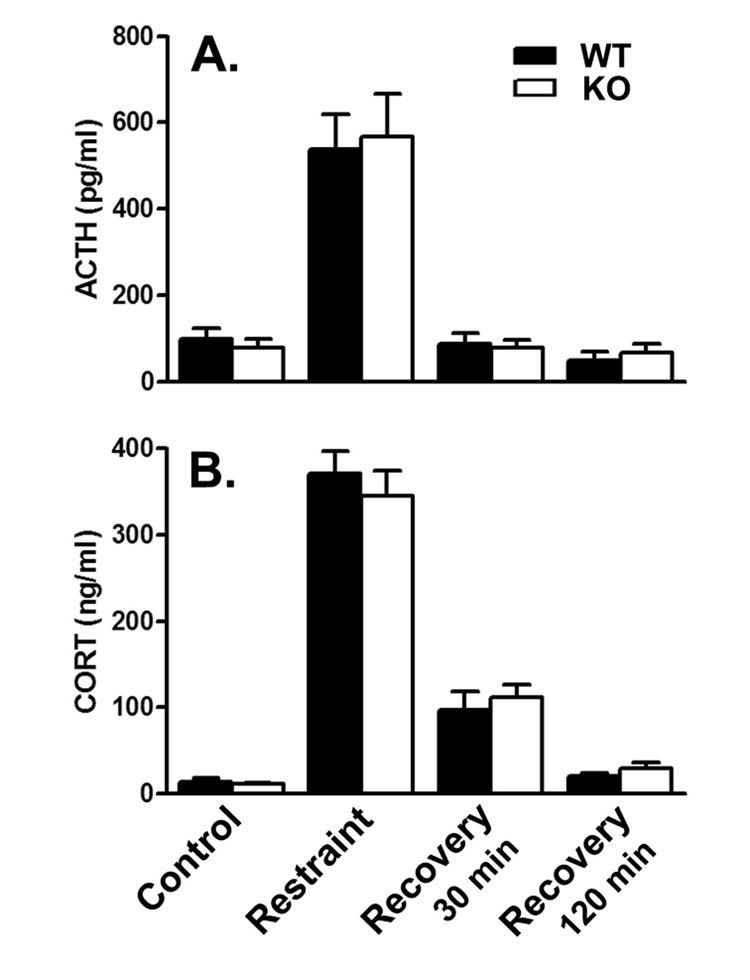

3.3. Restraint stress for 120 min

Mean plasma ACTH concentration increased 5–7 fold in both genotypes immediately following 120 min of restraint (Fig. 3A). Within 30 min of recovery in the home cage, ACTH concentrations were restored to baseline. Mean plasma CORT concentration increased 25–31 times baseline values in both genotypes immediately after 120 min of restraint stress (Fig. 3B). With 30 min of recovery in the home cage, elevations in plasma CORT concentration were reduced to about 5–10 times baseline in both genotypes. After 120 min recovery, plasma CORT concentrations were restored very close to baseline. Results were analyzed by means of a two-way ANOVA with genotype and stress condition as factors. There were no statistically significant interactions and no effects of genotype for either hormone. The effects of stress condition were statistically significant for both ACTH (F(3,62)=34.13; P<0.0001) and CORT (F(3,76)=183.17; P<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Recovery from 120 min of restraint stress in WT (filled bars) and KO (open bars) mice: effects on plasma ACTH (A.) and CORT (B.). Values are the means ± SEMs for the following number of animals: A. Control, 10 WT and 11 KO; 120 min restraint, 10 WT and 11 KO; 30 min recovery, 10 WT and 11 KO; 120 min recovery 10 WT and 11 KO; B. Control, 9 WT and 10 KO; 120 min restraint, 9 WT and 11 KO; 30 min recovery, 8 WT and 8 KO; 120 min recovery 5 WT and 10 KO. Results were analyzed by means of a two-way ANOVA with genotype and condition as factors. There were no statistically significant interactions and no effects of genotype for either hormone. Effects of condition were statistically significant for both ACTH (F(3,62)=34.13; P<0.0001) and CORT (F(3,76)=183.17; P<0.0001) concentrations.

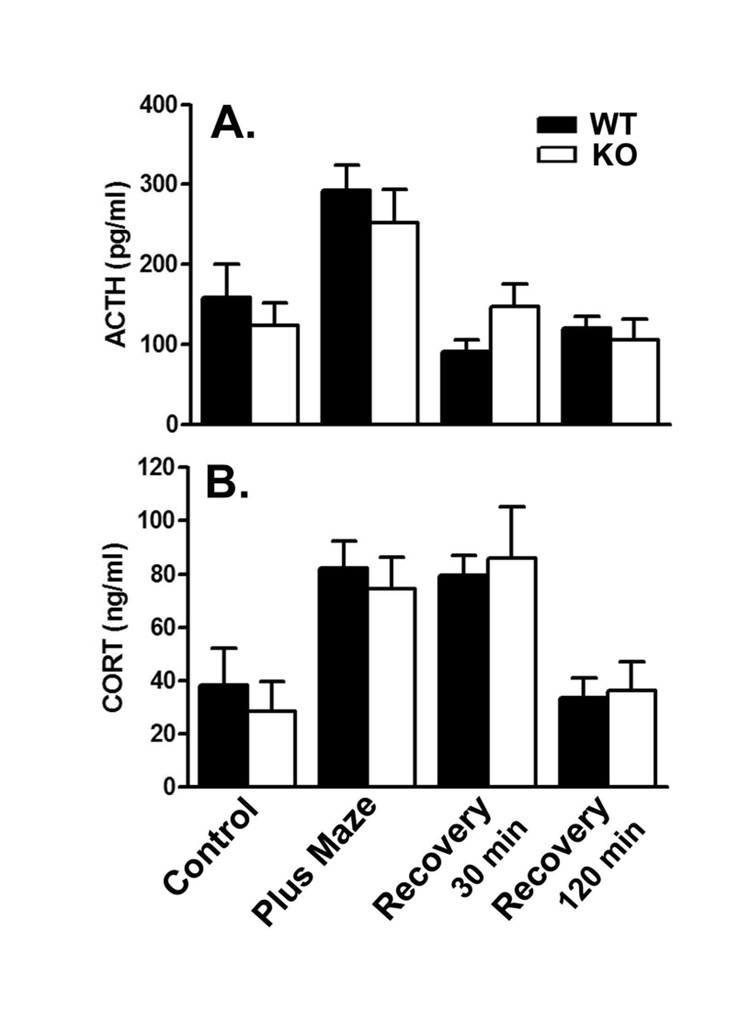

3.4. Spatial novelty

Immediately following 5 min in an elevated plus-maze, mean ACTH concentrations were about twice baseline in both genotypes, but returned to near baseline with 30 and 120 min home cage recovery (Fig. 4A). Plasma CORT concentrations increased 2–3 times baseline in both genotypes after 5 min of plus-maze exposure (Fig. 4B). Plasma CORT remained elevated even after 30 min of home cage recovery, but returned to baseline levels by 120 min. Results were analyzed by means of a two-way ANOVA with genotype and stress condition as factors. There were no statistically significant interactions and no effects of genotype for either hormone. The effects of stress condition were statistically significant for both ACTH (F(3,71)=10.07; P<.0001) and CORT (F(3,70)=7.95; P=0.0001).

Figure 4.

Recovery from spatial novelty of 5 min in an elevated plus maze in WT (filled bars) and KO (open bars) mice: effects on plasma ACTH (A.) and CORT (B.). Values are the means ± SEMs for the following number of animals: A. Control, 8 WT and 4 KO; 5 min spatial novelty, 12 WT and 13 KO; 30 min recovery, 10 WT and 12 KO; 120 min recovery 10 WT and 10 KO; B. Control, 8 WT and 5 KO; 5 min spatial novelty, 12 WT and 13 KO; 30 min recovery, 10 WT and 12 KO; 120 min recovery 9 WT and 10 KO. Results were analyzed by means of a two-way ANOVA with genotype and condition as factors. There were no statistically significant interactions and no effects of genotype for either hormone. Effects of condition were statistically significant for both ACTH (F(3,70)=10.07; P<0.0001) and CORT (F(3,70)=7.95; P<0.0001) concentrations.

We also monitored behavior of the mice during the five min period of spatial novelty in the elevated plus-maze. Despite the similar plasma stress hormone responses in both genotypes we found differences in their behavior in the novel environment. The mean percent time spent in the open arms was 24% greater in KO mice (WT: 49 ± 3%, n=31; KO: 61 ± 3%, n=35; P<0.01, Student’s t-test) suggesting that KO mice responded to the novel environment with less anxiety than WT mice.

4. Discussion

The results of our study indicate that, in FVN/NJ mice, the hormonal response to and recovery from acute stress is unaltered by the lack of FMRP. We found similar hormonal responses in KO and WT mice following 30 or 120 min of restraint or five min of spatial novelty. Patterns of recovery for two hours following any of these stressors were also similar in both genotypes.

4.1. Measurements

Collection of blood samples for measurement of plasma concentrations of stress hormones is fraught with potentially confounding factors. We carefully controlled for effects due to the method of blood collection, the handling of animals, environmental stress, and time of day. Initially, we determined that rapid decapitation without anesthesia gave the lowest and most consistent plasma CORT concentrations. We acclimated animals to handling over a period of 4 days before each study, and we were careful to use completely separate rooms for housing, behavior and decapitation.

We were also careful to consider circadian fluctuations in HPA hormones in both genotypes. Not only do levels of hormones vary over the 24 h period, but responsiveness of the HPA axis also varies. It is at the nadir of the rhythm that the axis is most responsive to stress. The rhythm for ACTH was not clearly defined, and variability in the measurement of ACTH was greater than that of CORT. We found a clear rhythm of CORT concentration that was similar in both genotypes. At the nadir (between 2 and 10 am) of the rhythm for CORT, concentrations of CORT were about one third of those at the zenith (2 pm). Interestingly, the zenith of plasma CORT in our mice on an FVB/NJ background relative to the onset of the dark phase of the light:dark cycle was earlier than reported in other strains of mice. In C57BL/6J and Swiss mice the peak plasma CORT concentration occurred at the beginning of the dark phase (Dalm et al., 2005; Lechner et al., 2000). For the purposes of our study the important finding was that the circadian pattern of CORT secretion was similar in both genotypes (WT and KO). In light of these findings, mice were always subjected to stressors between 7 and 10 am.

Our results differ from reports in the literature in which fmr1 KO mice were similarly stressed (Lauterborn, 2004; Markham et al., 2006). Baseline levels of CORT in our mice tended to be lower and effects of restraint greater than those reported in either study. The likely explanation is that all of our mice were studied at the nadir of the hormonal cycle when hormone values are lowest and responsiveness greatest. In our study, recovery from restraint was partial after 30 min and complete after 120 min in the home cage, whereas in the study reported by Markham et al. (2006) recovery appears to be slower and possibly different between the genotypes. One possible explanation is that in the study of Markham et al. (2006) mice recovered in “an empty cage” rather than the home cage. The “empty cage” may have been an additional stressor, a spatial novelty. In our study “spatial novelty” in an elevated plus-maze produced a more prolonged elevation in CORT, i.e., after 30 min of recovery, concentrations in plasma were similar to those measured immediately following exposure to the plus-maze. Another factor to consider is that of genetic background. Our animals were on an FVB/NJ background, whereas those in the study of Markham et al (2006) were on a C57/Bl6 background. The background of the animals studied by Lauterborn (2004) was not specified. Genetic background can clearly have effects on behavior (Crawley et al., 1997) and can influence the effects of a the fmr1 knockout on behavioral phenotype (Paradee et al., 1999; Dobkin et al., 2000).

4.2. Intensity and Duration of Stressors

Whereas the magnitude of the increases in CORT in response to stress appeared to vary with the intensity of the stressor, the time course of recovery was not a function of either the intensity or duration of the stress. For example the greatest effects on CORT were seen with 120 min of restraint stress and the smallest effects with exposure to 5 min of spatial novelty, but effects on CORT were most prolonged with exposure to spatial novelty. Recovery from the effects of stress was generally faster for ACTH compared with CORT, consistent with the shorter half-life of ACTH. Following any of the three acute stressors studied, ACTH concentrations returned to baseline after 30 min in the home cage, whereas CORT concentrations remained above baseline until the 2 h recovery time point.

4.3. Anxiety

Behavior in the elevated plus-maze indicates that fmr1 KO mice are less anxious than WT mice. This is in agreement with results of behavior of KO mice in the open field and the light-dark exploration test. Normally rodents seek cover and avoid open spaces, behaviors thought to be associated with anxiety (Crawley, 1989). Rodents also prefer a dark environment, and given a choice between going into a lighted chamber and remaining in a darkened chamber, tend to make few transitions into the lighted chamber. In this test KO mice exhibited a greater number of light-dark transitions than WT indicating a lower level of anxiety (Peier et al, 2000). In the open field KO mice spent more time in the center of the field, made more entrances into the center, and moved less distance in the margins (%) compared with WT (Qin et al., 2002; 2005). These behaviors are all consistent with reduced anxiety in the KO.

One of the symptoms associated with FraX is heightened social anxiety (Hagerman, 2002). To our knowledge there is no documentation of heightened non-social anxiety as a symptom of FraX. Social anxiety and nonsocial anxiety can be dissociated. In macaque monkeys, neonatal lesion of the amygdala resulted in increased social fear and decreased fear of inanimate objects (Prather et al., 2001). Further, in children with Williams-Beuren syndrome hypersociability is a major characteristic (Bellugi et al., 1999), but this is coupled with heightened non-social anxiety (Dykens, 2003). In this respect FraX may be a mirror image of Williams-Beuren syndrome. In the mouse model of FraX, behavior in the elevated plus-maze, light-dark exploration test, and the open field do not address the issue of social anxiety. These behavioral phenotypes in the mouse demonstrate reduced non-social anxiety in the KO. Results of the mirrored chamber test provide some indication that KO mice may have increased social anxiety (Spencer et al., 2005). Further assessment of social anxiety will require tests specifically designed to monitor social interactions in mice.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Zengyan Xia for overseeing the breeding colony, determining the genotypes of the mice, and assistance with the plus-maze analysis. We also wish to thank Tianjian Huang for help with dissection of adrenal glands. The research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIMH, NIH and the Fragile X Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bakker CE Dutch-Belgian Consortium. Fmr1 knockout mice: A model to study fragile X mental retardation. Cell. 1994;78:23–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellugi U, Adolphs R, Cassady C, Chiles M. Towards the neural basis of hypersociability in a genetic syndrome. NeuroReport. 1999;10:1653–1657. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199906030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley JN. Animal models of anxiety. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 1989;2:773–776. [Google Scholar]

- Crawley JN, Belknap JK, Collins A, Crabbe JC, Frankel W, Henderson N, Hitzemann RJ, Maxson SC, Miner LL, Silva AJ, Wehner JM, Wynshaw-Boris A, Paylor R. Behavioral phenotypes of inbred mouse strains: implications and recommendations for molecular studies. Psychopharm. 1997;132:107–124. doi: 10.1007/s002130050327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalm S, Enthoven L, Meijer OC, van der Mark M, Karsson AM, de Kloet ER, Oitzl MS. Age-related changes in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity of male C57BL/6J mice. Neuroendocrin. 2005;81:372–380. doi: 10.1159/000089555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin C, Rabe A, Dumas R, El Idrissi A, Haubenstock H, Brown T. Fmr1 knockout mouse has a distinctive strain-specific learning impairment. Neurosci. 2000;100:423–429. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00292-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens EM. Anxiety, Fears, and Phobias in Persons with Williams Syndrome. Dev. Neuropsych. 2003;23:291–316. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2003.9651896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ. The physical and behavioral phenotype. In: Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ, editors. Fragile X Syndrome: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Research. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press; 2002. pp. 3–109. [Google Scholar]

- Hessl D, Glaser B, Dyer-Friedman J, Blasey C, Hastie T, Gunnar M, Reiss AL. Cortisol and behavior in fragile X syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrin. 2002;27:855–872. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauterborn JC. Stress induced changes in cortical and hypothalamic c-fos expression are altered in fragile X mutant mice. Mol. Brain Res. 2004;131:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner O, Dietrich H, Oliveira dos Santos A, Wiegers GJ, Schwarz S, Harbutz M, Herold M, Wick G. Altered circadian rhythms of the stress hormone and melatonin response in lupus-prone MRL/MP-faslpr mice. J. Autoimmun. 2000;14:325–333. doi: 10.1006/jaut.2000.0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham JA, Beckel-Mitchener AC, Estrada CM, Greenough WT. Corticosterone response to acute stress in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrin. 2006;31:781–785. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LJ, McIntosh DN, McGrath J, Shyu V, Lampe M, Taylor AK, Tassone F, Neitzel K, Stackhouse T, Hagerman RJ. Electrodermal responses to sensory stimuli in individuals with fragile X syndrome: A preliminary report. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999;83:268–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashiro KY, Beckel-Mitchener A, Purk TP, Becker KG, Barret T, Liu L, Carbonetto S, Weiler IJ, Greenough WT, Eberwine J. RNA cargoes associating with FMRP in cellular functioning in Fmr1 null mice. Neuron. 2003;37:417–431. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradee W, Melikian HE, Rasmussen DL, Kenneson A, Conn PJ, Warren S. Fragile X mouse:strain effects of knockout phenotype and evidence suggesting deficient amygdala function. Neurosci. 1999;94:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peier AM, McIlwain KL, Kenneson A, Warren ST, Paylor R, Nelson DL. (Over)correction of FMR1 deficiency with YAC transgenics: Behavioral and physical features. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:1145–1159. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.8.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prather MD, Lavenex P, Maudlin-Jourdain ML, Mason WA, Capitanio JP, Mendoza SP, Amaral DG. Increased social fear and decreased fear of objects in monkeys with neonatal amygdala lesions. Neurosci. 2001;106:653–658. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00445-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin M, Kang J, Smith CB. Increased rates of cerebral glucose metabolism in a mouse model of fragile X mental retardation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sc.i,USA. 2002;99:15758–15763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242377399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin M, Kang J, Burlin TV, Jiang C, Smith CB. Postadolescent changes in regional cerebral protein synthesis: An in vivo study in the Fmr1 null mouse. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:5087–5095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0093-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau FD, Heitz D, Tarleton J, et al. A multicenter study on genotype-phenotype correlations in fragile X syndrome, using direct diagnosis with probe StB12:3: The first 2253 cases. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1994;55:225–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer CM, Alekseyenko O, Serysheva E, Yuva-Paylor LA, Paylor R. Altered anxiety-related and social behaviors in the Fmr1 knockout mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2005;4:420–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisbeck JM, Huffman LC, Freund L, Gunnar M, Davis EP, Reiss AL. Cortisol and social stressors in children with fragile X syndrome: A pilot study. Dev. Behav. Ped. 2000;21:278–282. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200008000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]