Abstract

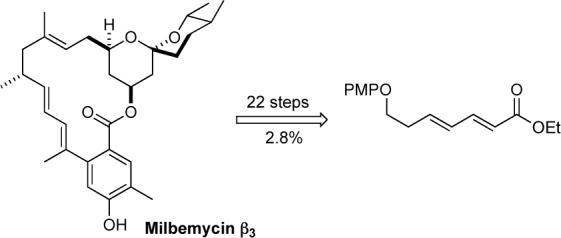

The enantioselective synthesis of the spiroketal/macrolide natural product milbemycin β3 has been achieved in 22 steps and 2.8% overall yield from an achiral dienoate. The spiroketal ring system was installed by three sequential asymmetric hydrations followed by sprioketalization. Both the absolute and relative stereochemistry of milbemycin β3 was introduced by two Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylations, two π-allyl-palladium catalyzed reductions and an iridium catalyzed hydrogen migration/Claisen rearrangement to install the C-12 stereocenter.

Since their initial isolation and structural determination, the milbemycins1,2 have attracted significant interest for their potential use as pesticides and pharmaceuticals. In addition to antibiotic activity, various members of this class of spiroketal/macrolide natural products have shown significant activity against various agricultural pests (e.g. mites, beetles, and tent caterpillars)2,3 and parasites (e.g. nematodes, mites, ticks, and larvae of biting flies),2,4 while displaying minimal cytotoxicity to plants and animals.5 Pharmacological interest in the milbemycins re-emerged, after it was discovered that they are also potent efflux pump inhibitors.6

In addition to this array of fascinating biological activities, the milbemycin structural complexity has also attracted the attention of the synthetic community.7,8 To date several total syntheses of milbemycin β3 have been completed,7 along with various efforts to the spiroketal ring system.8 While all of the previous syntheses of the milbemycin (1) derived their asymmetry from the chiral pool, we were interested in a de novo asymmetric approach that would use asymmetric catalysis to install the six stereocenters in milbemycin β3 from achiral starting materials (5 and 10, Scheme 1).9 Herein we describe our successful efforts to implement this strategy for the de novo synthesis of milbemycin β3.

Scheme 1.

Milbemycin β3 (1) and its Retrosynthesis.

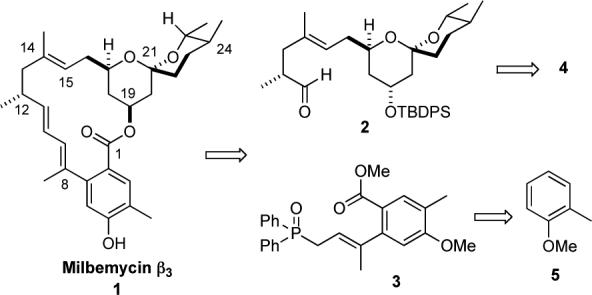

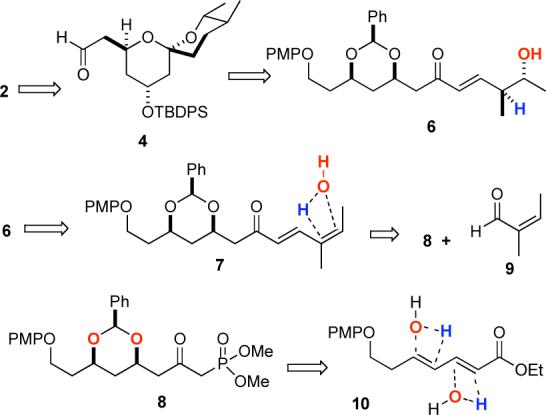

Retrosynthetically, we envisioned milbemycin β3 (1 ) being prepared by an olefination/macrolactonization strategy. This transform divided the molecule into two halves, an achiral phosphine oxide 3, which was first prepared by Smith,10 and a silyl-protected hydroxyaldehyde 2, which possessed both the spiroketal and the five chiral centers of milbemycin. Following the Barrett precedent, we planned to install the sixth chiral center during a Mitsunobu macrocyclization.11

Using a transition metal variant of the Smith's vinyl anion addition Claisen rearrangement, we planned to prepare 2 from spiroketal 4, which in turn could be prepared from the partially protected tetraol 6. Finally, we hoped to establish the four chiral centers and triol functionality of 6 by the iterative use of our asymmetric hydration protocol (i.e. 10 to 8 and 7 to 6).12

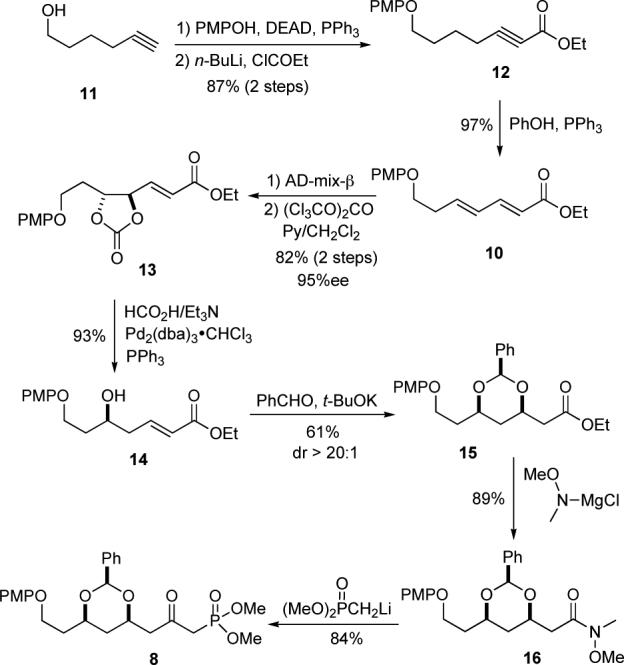

In practice dienoate 10 was prepared by a 3-step protocol from commercially available 11 via protection, carboxylation and ynoate isomerization.13 Using our 3-step asymmetric hydration protocol (dihydroxylation, carbonate formation and palladium catalyzed reduction)12 dienoate 10 was regio- and enantioselectively transformed into δ-hydroxy enoate 14 , which in turn was diastereoselectively hydrated to form the protected 3,5-dihydroxy ester 15 using Evans’ procedure.14 The ester 15 was then converted into the β-keto-phosphonate 8 via Weinreb amide 16 (75% for the two steps).

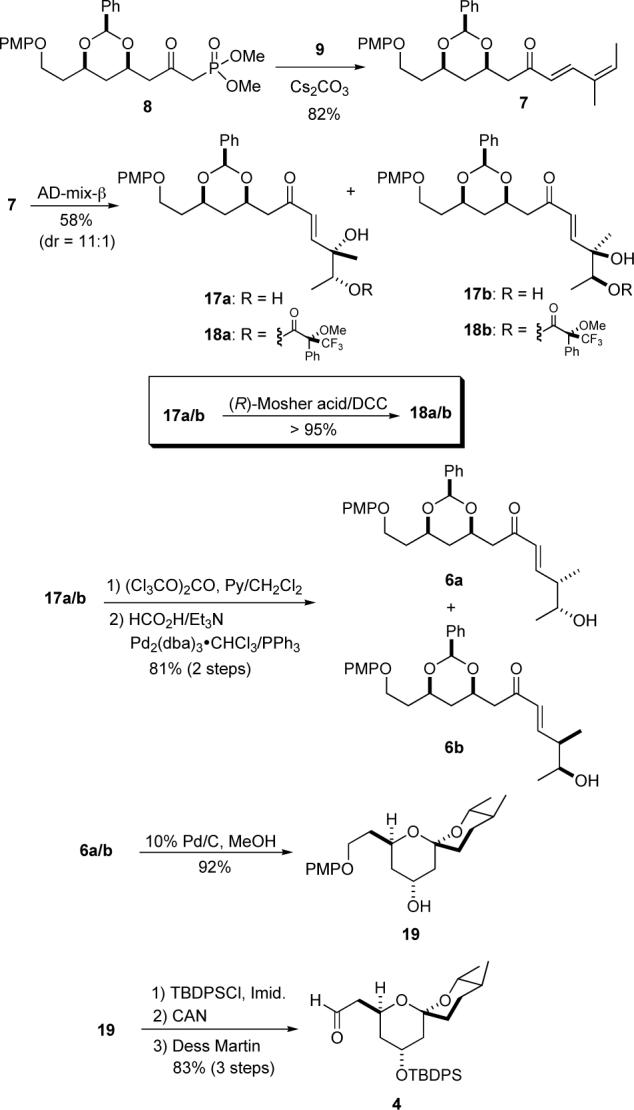

The last five carbons of the spiroketal portion of milbemycin β3 came from angelaldehyde (9) and were installed via a Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons reaction with 8. Exposure of keto-phosphonate 8 to aldehyde 9 with Cs2CO3 as base produced the E,Z-dienone 7 in 82% yield (Scheme 4). Using a similar 3-step sequence, as on dienoate 10, dienone 7 was diastereoselectively hydrated (7 to 17a).12 Regioselective dihydroxylation of 7 gave an inseparable diols 17a/b in 58% yield and diastereocontrol.15 Because of the distance between the relevant stereocenters, it was difficult to distinguish diastereomers 17a and 17b by 1H NMR and TLC. Thus, Mosher ester analysis (17a/b to 18a/b, see Supporting Information) was used to determine the diastereomeric ratio of 17a to 17b (dr = 11:1). The mixture of diastereomers 17a/b was converted into cyclic carbonates and stereoselectively reduced with HCO2H/Et3N and catalytic palladium(0) in CH2Cl2/hexane to give alcohols 6a/b (93%).16 As with 17a/b, the diastereomers 6a/b were not easily differentiated by 1H NMR or separated by chromatography. The diastereomeric alcohols 6a/b were cleanly converted into spiroketal 19 via a one–pot hydrogenation/hydrogenolysis/spiroketalization procedure (92%). The minor diastereomeric impurity in 19 was easily removed by recrystallization from a mixture of EtOAc/hexanes (9:1). The C-19 alcohol was protected as the TBDPS-ether, the PMP-group was oxidatively removed with CAN and the C-15 alcohol was oxidized to the aldehyde with the Dess-Martin reagent in an 83% overall yield.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of Spiroketal 4 via Dienone Hydration.

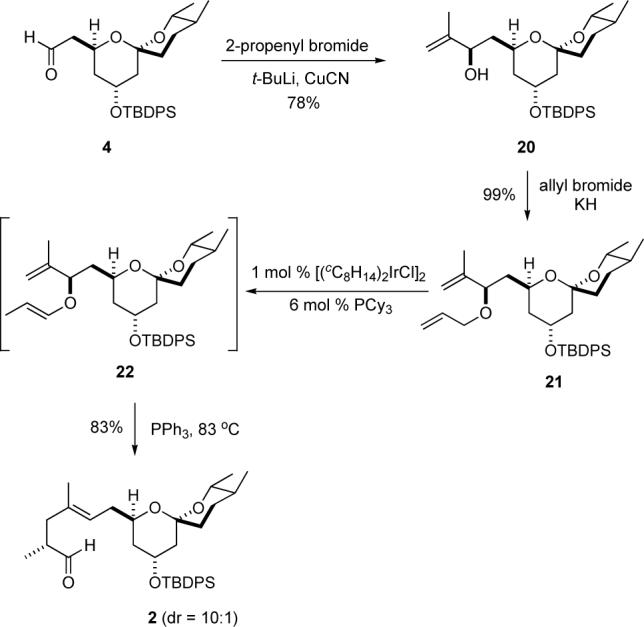

We next looked to extend the C-15 aldehyde to the C-11 aldehyde. Based on the Smith synthesis, we planned to establish the C-14/C-15 E-double bond and the C-12 stereocenter by a Claisen rearrangement. In contrast to Smith's use of an Ireland enolate rearrangement, we chose to use the isomerization-Claisen rearrangement (ICR) developed by Nelson.17 This procedure has the added advantage of providing the aldehyde 2 directly.

When aldehyde 4 was exposed to a vinylcuprate reagent an exceedingly diastereoselective addition (dr > 20:1) occurred to give allylic alcohol 20 in good yield (78%). The allylic alcohol 20 was allylated with KH/AllylBr to give allylic ether 21 in nearly quantitative yield (99%). Following the Nelson protocol allylic ether 21 was exposed to catalytic iridium and tricyclohexyl phosphine. Under these conditions, allylic ether 21 cleanly rearranged to the E-enolether 22, at which point 6 mol% PPh3 was added and the dichloroethylene solution was refluxed. After heating for 24 h an 83% yield of aldehyde 2 was isolated. While aldehyde 2 can be purified by SiO2 chromatography, this leads to lower diastereoselectivity (dr = 4:1). The preferred procedure was to use the crude aldehyde in the subsequent transformation. Analysis of the crude 1H NMR indicated that the diastereomeric ratio of crude 2 was on the order of 10:1.

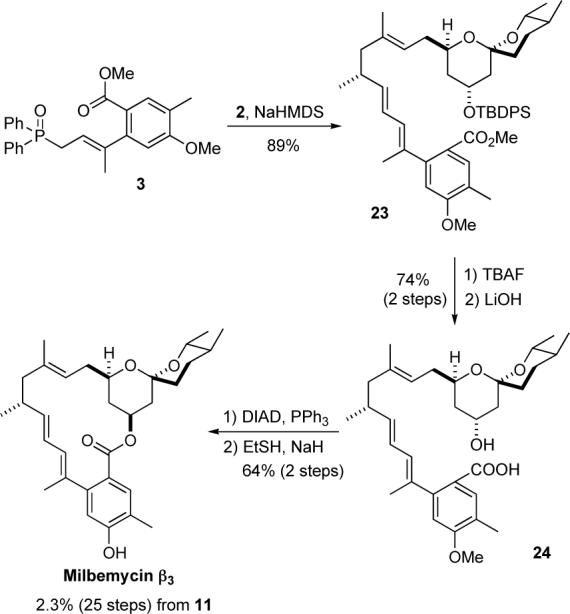

Finally, with aldehyde 2 in hand, we set out to stitch the two fragments together via an olefination and lactonization. The E,E-diene of 23 was stereoselectively installed upon exposure of a crude solution of aldehyde 2 with the sodium salt of phosphine oxide 3. Before the lactonization could commence, the silyl-ether was removed (TBAF, 95%) and the methyl ester was hydrolyzed (LiOH, 78%). Then following the Barrett procedure the 19-epi-seco acid 24 was lactonized with DIAD/PPh3 in good yield (79%). Using NaSEt the methyl protecting group was removed, providing 30 mg of synthetic material that was physically (mp, optical rotation)18 and spectroscopically (1H NMR, 13C NMR, IR and MS) identical to natural milbemycin β3 (1).

In conclusion, a short de novo asymmetric synthesis of milbemycin β3 (1 ) has been developed. This highly enantio- and diastereocontrolled route illustrates the utility of our dienoate/dienone asymmetric hydration strategy for natural product synthesis. In addition, it features the use of Nelson's isomerization-Claisen rearrangement (ICR) in a structurally complex setting. This approach provided milbemycin β3 (1) in 2.3% overall yields from 5-hexyn-1-ol (11), which should be amenable to the preparation of its enantiomer. Further application of this approach to the synthesis of structurally more complex members of this class of compounds and biological testing is ongoing.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 2.

Retrosynthesis of Spiroketal 2.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis and Bis-Hydration of Dienoate 10.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of Aldehyde 2 via an ICR Reaction.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of Milbemycin β3 (1) via a Macrolactonization.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to NIH (GM63150) and NSF (CHE-0415469) for the support of our research program and NSF-EPSCoR (0314742) for a 600 MHz NMR and an LTQ-FT Mass Spectrometer at WVU.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Complete experimental procedures and spectral data for all new compounds can be found in the Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.a Mishima H, Kurabayashi M, Tamura C, Sato S, Kuwano H, Saito A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975;16:711–714. [Google Scholar]; b Takiguchi Y, Ono M, Muramatsu S, Ide J, Mishima H, Terao M. J. Antibiot. 1983;36:502–508. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Takiguchi Y, Mishima H, Okuda M, Terao M, Aoki A, Fukuda R. J. Antibiot. 1980;33:1120–1127. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.33.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For a review see: Shoop WL, Mrozik H, Fisher MH. Vet. Parasitol. 1995;59:139–156. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(94)00743-v. Aoki A. J. Pest. Sci. 1992;19:245–247.

- 3.Thamsborg S, Roepstorff A, Larsen M. Vet. Parasitol. 1999;84:169–186. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(99)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowman DD, Parsons JC, Grieve RB, Hepler DI. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1988;49:1986–1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a Material Safety Data Sheet: Moxidectin: Fort Dodge Animal Health. ; b Fisher MH. Pure Appl. Chem. 1990;62:1231–1240. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chamberland S, Lee M, Lomovskaya O. Milbemycin class efflux pump inhibitors for treating microbial infections and cancer. 1999. WO 98-US20916 19981001. AN1999:244572.

- 7.a Smith AB, III, Schow SR, Bloom JD, Thompson AS, Winzenberg KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:4015–4018. [Google Scholar]; b Schow SR, Bloom JD, Thompson AS, Winzenberg KN, Smith AB., III J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:2662–2674. [Google Scholar]; c Williams DR, Barner BA, Nishitani K, Phillips JG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:4708–4710. [Google Scholar]; d Street SDA, Yeater C, Kocienski P, Campbell SF. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1985:1386–1388. [Google Scholar]; e Attwood SV, Barrett AGM, Carr RAE, Robinson G. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1986:479–481. [Google Scholar]; f Baker R, O'Mahony MJ, Swain CJ. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1985:1326–1328. [Google Scholar]; g Barrett AGM, Carr RAE, Attwood SV, Richardson G, Walshe NDA. J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:4840–4856. [Google Scholar]

- 8.a Yeater C, Street SDA, Kocienski P, Campbell SF. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1985:1388–1389. [Google Scholar]; b Baker R, O'Mahony MJ, Swain CJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:3059–3062. [Google Scholar]; c Crimmins MT, Bankaitis-Davis DM, Hollis WG., Jr. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:652–657. [Google Scholar]; d Holoboski MA, Koft E. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:965–969. [Google Scholar]

- 9.While it did not exclusively use asymmetric catalysis, Emil Koft had previous demonstrated that the spiroketal portion of Milbemycin β3 could be prepared from an achiral starting material, see: ref 8d.

- 10.We prepared phosphine oxide 3 by a slightly modified variant of the Smith route, see Supporting Information and ref 7b.

- 11.Barrett had previously shown that the C-19 carboxylate could be installed by a Mitsunobu reaction, see: ref 7g. and Mitsunobu O. Synthesis. 1981:1–28.

- 12.For examples of the asymmetric hydration of unsubstituted dienoates (e.g. 10 to 8), see: Hunter TJ, O'Doherty GA. Org. Lett. 2001;3(7):1049–1052. doi: 10.1021/ol0156188.. Our study of the asymmetric hydration of substituted dienoates, will be published in due course.

- 13.a Rychnovsky SD, Kim J. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:2659–2660. [Google Scholar]; b Trost B, Kazmaier U. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:7933–35. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans DA, Gauchet-Prunet JA. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:2446–2453. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Because most of the enantiomeric impurity in 7 is converted into the minor diastereomer ent-17b during the asymmetric dihydroxylation (7 to 17a/b), the major diastereomer diol 17a was isolated in essentially enantiomeric pure form. Consequently, the minor diastereomer 17b must be formed with lower enantiopurity. For other examples of this enantioenriching phenomena, see: Ahmed Md. M., Berry BP, Hunter TJ, Tomcik DJ, O'Doherty GA. Org. Lett. 2005;7:745–748. doi: 10.1021/ol050044i.

- 16.The CH2Cl2/hexane solvent mixture was critically important to insure high yields for the palladium catalyzed reduction. For instance, use of THF as solvent gave a 1:1 mixture of double bond regioisomers.

- 17.a Nelson SG, Bungard CJ, Wang K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:13000–13001. doi: 10.1021/ja037655v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Nelson SG, Wang K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:4232–4233. doi: 10.1021/ja058172p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The synthetic material had a melting point range of 182−184 °C and an optical rotation of +99 (c = 0.25, MeOH) which is in good agreement with the literature value (Mp = 181−183 °C; [α]D = +102 (c = 0.17, MeOH)). The actual value for the optical rotation of milbemycin β3 has been a source of disagreement. For an interesting discussion of this issue along with its resolution, see: ref 7g.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.