Abstract

Background and objectives: The prevalence of mineral metabolism abnormalities is almost universal in stage 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD), but the presence of abnormalities in milder CKD is not well characterized.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: Data on adults ≥20 yr of age from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2004 (N = 3949) were analyzed to determine the association between moderate declines in estimated GFR (eGFR), calculated using the Modfication of Diet in Renal Disease formula, and serum intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) ≥ 70 pg/ml.

Results: The geometric mean iPTH level was 39.3 pg/ml. The age-standardized prevalence of elevated iPTH was 8.2%, 19.3%, and 38.3% for participants with eGFR ≥ 60, 45 to 59, and 30 to 44 ml/min/1.73 m2, respectively (P-trend < 0.001). After adjustment for age; race/ethnicity; sex; menopausal status; education; income; cigarette smoking; alcohol consumption; body mass index; hypertension; diabetes mellitus; vitamin D supplement use; total calorie and calcium intake; and serum calcium, phosphorus, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels—and compared with their counterparts with an eGFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2—the prevalence ratios of elevated iPTH were 2.30 and 4.69 for participants with an eGFR of 45 to 59 and 30 to 44 ml/min/1.73 m2, respectively (P-trend < 0.001). Serum phosphorus ≥ 4.2 mg/dl and 25-hydroxyvitamin D < 17.6 ng/ml were more common at lower eGFR levels. No association was present between lower eGFR and serum calcium < 9.4 mg/dl.

Conclusions: This study indicates that elevated iPTH levels are common among patients with moderate CKD.

Alterations in bone and mineral metabolism are present in nearly all patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD) (1,2). Although severe osteodystrophy is less common in earlier stages of CKD, elevated intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) levels, considered one of the earliest markers of abnormal bone mineral metabolism in CKD, have been reported frequently in clinic-based studies of patients with renal insufficiency (3–10). Also, even moderate reductions in renal function have been associated with significant increases in the risk of hip fracture (11,12). However, the stage of CKD at which iPTH begins to increase and the risk factors for elevated iPTH have not been well characterized (13).

To identify and manage metabolic bone abnormalities in the context of CKD, the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) guidelines recommend routine measurement of serum iPTH, phosphorous, and calcium levels (13). Among patients with elevated iPTH above the target range, assessment of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] status and correction of 25(OH)D insufficiency are recommended. In addition, dietary interventions, including reduced phosphorous consumption, may be required. However, many patients find adherence to such diets difficult (4,14,15). Therefore, phosphate binders and calcitriol should be considered as adjunctive therapy (16,17).

Despite these guidelines, knowledge of the epidemiology of metabolic bone disease in the population with less severe CKD remains limited (18,19). Given the large number of patients with CKD, characterizing the burden of, and outcomes associated with, alterations in bone and mineral metabolism has important clinical implications. Furthermore, studies of early CKD are essential for preventing adverse outcomes caused by longstanding untreated mineral metabolism alterations. To better characterize the level of renal function at which markers of metabolic bone disease become abnormal, we analyzed data on estimated GFR (eGFR) and iPTH from the population-based National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2004. Because serum calcium, phosphate, and 25(OH)D levels are associated with iPTH levels, we assessed the association between these serum markers and eGFR in a secondary analysis. In addition, factors associated with elevated iPTH were determined.

Materials and Methods

NHANES 2003–2004 was a cross-sectional survey that included a nationally representative sample of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population of the United States. The procedures involved in this study have been published in detail and are available online (20). Participants were selected for enrollment by means of a stratified, multistage probability sampling strategy. Stages of selection included counties, blocks, households, and persons within households. Overall, 4742 adults (20 yr of age and older) completed both the interview and medical evaluation components of the NHANES 2003–2004. After we excluded participants who were missing serum creatinine (n = 287), had an eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 or were on dialysis (n = 43), lacked iPTH measurements (n = 4), or lacked covariate data (n = 459), 3949 participants were available for analysis.

Study procedures in NHANES 2003–2004 consisted of an in-home interview followed by a medical evaluation and blood sample collection at a mobile examination center. Of relevance to the current analysis, variables collected during the in-home interview included age, race/ethnicity, sex, menopausal status (for women), cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, education, household income, and medical history. For the current analysis, race/ethnicity was defined as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Mexican-American, and other. Information regarding the use of vitamin D and calcium supplements in the 2 wk before the participants’ study visits were obtained through questionnaires and pill bottle reviews.

The NHANES 2003–2004 examination procedures included measurement of height, weight, and BP. Three BP measurements were taken during the examination visit using a protocol adapted from the American Heart Association. On the basis of the average of the three measurements, hypertension was diagnosed if any of the following conditions was met: systolic BP ≥ 140 mmHg, diastolic ≥ 90 mmHg, or self-reported current use of BP-lowering medication. Because fasting plasma glucose level was available only from a subsample of participants, diabetes mellitus was defined as a self-report of a previous diagnosis by a doctor or other healthcare provider while not pregnant, along with current use of insulin and or oral hypoglycemic drugs. During the medical examination, a 24-h dietary recall was conducted. A second recall was conducted by telephone 3 to 10 d later. For the 3680 participants who completed both recalls, the average calorie and calcium intake was used for analysis. Data from a single recall was used for the remaining 269 participants who completed the first but not the second diet recall. Total calcium intake (mg/d) was calculated as the sum obtained through diet and supplementation.

Detailed descriptions of blood collection and processing are provided in the NHANES Laboratory/Medical Technologists Procedures Manual. Serum iPTH was measured at the University of Washington on an Elecsys 1010 autoanalyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), using an electrochemiluminescent process. To measure iPTH, this second-generation method uses a biotinylated monoclonal PTH-specific antibody and a monoclonal PTH-specific antibody labeled with a ruthenium complex to form a sandwich complex. This assay provides measurements of iPTH within 10% of the Nichol's Allegro assay (21). Three levels of control specimens were used to assess the quality of each serum iPTH run. Coefficients of variation for serum iPTH remained < 10% throughout the study period. On the basis of the cut-point for defining elevated iPTH among adults with stage 3 CKD from the K/DOQI guidelines, elevated serum iPTH was defined as ≥ 70 pg/ml (13). Serum calcium and phosphorus levels were measured on the Synchron LX20 (Beckman-Coulter, Fullerton, CA). Serum calcium was corrected for serum albumin using the formula: adjusted calcium = measured calcium − [(4.0 − serum albumin in g/dl) × 0.8]. Serum 25(OH)D was quantified by RIA with a I125-labeled tracer, using the DiaSorin (Saluggia, Italy) assay in a two-step procedure (22). Elevated serum phosphorus was defined as values in the highest quartile (≥ 4.2 mg/dl), and low serum calcium and 25(OH)D were defined as values in the lowest quartile (< 9.4 mg/dl and < 17.6 ng/ml, respectively).

Serum creatinine was measured by the modified kinetic method of Jaffe. Serum creatinine measurements were consistent with the assays used in the development of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation, which was used to calculate eGFR (23).

Statistical Analyses

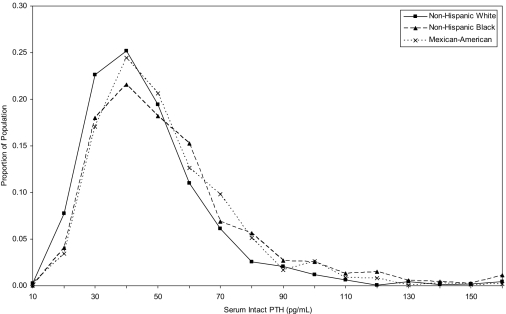

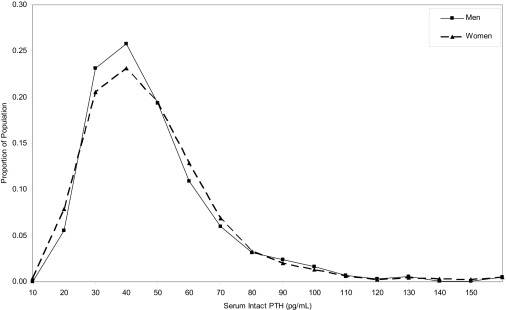

The overall age-standardized geometric mean serum iPTH and the prevalence of iPTH ≥ 70 pg/ml were calculated and stratified by participant characteristics. Standardization was performed to the age distribution of the United States’ adult population. Differences in age-standardized means and proportions across categories were calculated using linear and logistic regression models, respectively. Next, the distribution of iPTH was plotted separately for non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, Mexican-Americans, and for men and women.

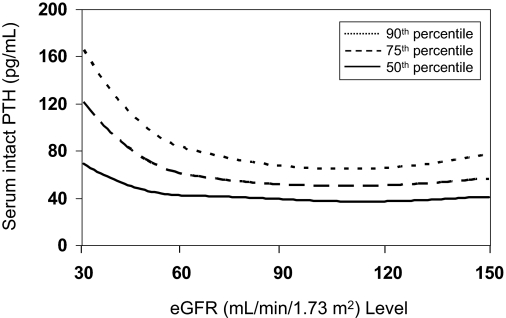

To explore iPTH levels across a broad range of eGFR (i.e., from 30 to 150 ml/min/1.73 m2), we used restricted quadratic splines with knots at eGFR levels of 60, 90, and 120 ml/min/1.73 m2. These splines were generated using quantile regression models for the median and 75th and 90th percentiles of iPTH after standardization to 60 yr of age and the sex and race/ethnicity distribution of U.S. adults (51% women, 80% non-Hispanic white, 12% non-Hispanic black, and 8% Mexican-American). Next, eGFR was categorized into three levels: ≥ 60, 45 to 59, and 30 to 44 ml/min/1.73 m2, and the age-standardized geometric mean serum iPTH and age-standardized prevalence and multivariate-adjusted prevalence ratios of elevated serum iPTH were calculated by eGFR level. Three sets of multivariate analyses were performed. Initially, the association of iPTH with eGFR was calculated after adjustment for age, race/ethnicity, and sex. A subsequent model included additional adjustment for menopausal status (for women), household income, education, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, vitamin D supplement use, and total calorie and dietary calcium intake. A final model also included adjustment for serum calcium, phosphorus, and 25(OH)D levels. Linear trends across eGFR levels were calculated by including eGFR level as an ordinal variable in the regression model. In secondary analyses, age-standardized geometric mean serum calcium, phosphorus, and 25(OH)D levels, and prevalence and prevalence ratios of low serum calcium, high serum phosphorus, and low 25(OH)D by level of eGFR were calculated.

Finally, correlates of elevated serum iPTH were determined for the overall population and separately among participants with and without stage 3 CKD (i.e., eGFR of 30 to 59 ml/min/1.73 m2) using prevalence ratios. Data were reanalyzed with elevated iPTH defined as levels ≥65 pg/ml, the upper limit of normal for the assay used in NHANES 2003–2004, with markedly similar results (data not shown). All data management was performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), and all analyses were weighted to the U.S. population using SUDAAN 9.01 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) after taking into account the multistage, complex survey design of NHANES 2003–2004.

Results

The geometric mean serum iPTH level was 39.3 pg/ml (95% confidence interval [CI]: 37.7, 40.8 pg/ml), and 9.6% of U.S. adults had an elevated iPTH (Table 1). Levels of serum iPTH were higher at older age and, after age-standardization, among non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican-Americans (compared with non-Hispanic whites). Levels were also higher at progressively higher body mass index levels and among participants with hypertension. Also, after age-standardization, serum iPTH levels were lower among former and current smokers (compared with those who never smoked), those who consumed ≥ 2 drinks per day (compared with nondrinkers), and those who took vitamin D supplements. Levels were also lower at higher levels of calcium intake and at higher levels of serum calcium, phosphorus, and 25(OH)D.

Table 1.

Age-standardized geometric mean serum iPTH and prevalence of elevated serum iPTH by participant characteristics (n = 3,949)

| Characteristic | % of sample | Geometric mean (95% CI) iPTH, pg/ml | iPTH ≥ 70 pg/ml, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 100 | 39.3 (37.7, 40.8) | 9.6 |

| Age group, years | |||

| <40 | 39 | 36.2 (34.5, 37.7) | 7.5 |

| 40 to 59 | 38 | 39.6 (37.7, 42.1) | 7.9 |

| 60 to 74 | 16 | 42.5 (40.9, 44.3) | 12.1 |

| ≥75 | 7 | 48.4 (46.1, 51.4)*** | 20.3*** |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| non-Hispanic white | 80 | 37.7 (36.2, 38.9) | 7.9 |

| non-Hispanic black | 12 | 45.2 (42.9, 47.5)***a | 16.3***a |

| Mexican-American | 8 | 42.9 (40.4, 45.6)***a | 13.9**a |

| Sex | |||

| male | 49 | 39.6 (38.1, 40.9) | 10.0 |

| female | 51 | 38.9 (37.3, 40.4) | 9.2 |

| Postmenopausal (among women) | |||

| yes | 43 | 39.8 (37.2, 42.5) | 10.7 |

| no | 57 | 39.5 (37.8, 41.1) | 7.9 |

| Income | |||

| ≤$20,000 / year | 18 | 39.6 (37.7, 41.7) | 10.0 |

| >$20,000 / year | 82 | 39.3 (37.7, 40.4) | 9.5 |

| Education | |||

| <high school diploma | 18 | 40.4 (38.1, 42.9) | 11.5 |

| ≥high school diploma | 82 | 38.9 (37.7, 40.4) | 9.1 |

| Smoking | |||

| never | 48 | 41.7 (40.4, 42.9) | 11.8 |

| former | 26 | 40.5 (38.9, 42.5) | 8.7*b |

| current | 26 | 34.5 (32.8, 36.2)***b | 6.2**b |

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| none | 33 | 40.9 (38.5, 43.9) | 11.9 |

| >0 but <2 drinks per day | 61 | 38.9 (37.7, 40.5) | 8.7 |

| ≥2 drinks per day | 5 | 34.1 (31.5, 37.3)**c | 3.5*c |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | |||

| <25 (normal weight) | 34 | 36.6 (35.2, 38.5) | 7.7 |

| 25-29 (overweight) | 34 | 38.1 (36.6, 40.0) | 8.0 |

| ≥30 (obesity) | 32 | 43.4 (41.7, 45.2)*** | 13.3** |

| Hypertension | |||

| no | 79 | 38.9 (37.7, 40.0) | 8.9 |

| yes | 21 | 42.5 (39.3, 45.6)* | 11.7** |

| Diagnosed diabetes mellitus | |||

| no | 94 | 39.3 (38.1, 40.9) | 9.5 |

| yes | 6 | 38.5 (36.2, 41.3) | 10.9 |

| Vitamin D supplement use | |||

| no | 86 | 40.0 (38.9, 41.3) | 10.1 |

| yes | 14 | 35.5 (32.8, 38.5)** | 4.8** |

| Quartile of total calorie intake, kcal | |||

| 1 (<1,502) | 23 | 40.4 (38.1, 42.9) | 10.2 |

| 2 (1,502 to 2,071) | 29 | 38.9 (37.4, 40.4) | 8.4 |

| 3 (2,072 to 2,746) | 25 | 38.9 (37.4, 40.4) | 8.2 |

| 4 (≥2,747) | 23 | 39.3 (37.0, 41.6) | 12.3 |

| Quartile of calcium intake, mg | |||

| 1 (<559) | 25 | 43.4 (41.7, 45.1) | 11.9 |

| 2 (559 to 841) | 25 | 39.3 (37.7, 40.8) | 9.3 |

| 3 (842 to 1,259) | 25 | 37.7 (37.7, 40.8) | 9.5 |

| 4 (≥1,260) | 25 | 35.9 (33.8, 38.0)*** | 6.8*** |

| Quartile of serum calcium, mg/dl | |||

| 1 (<9.4) | 20 | 43.9 (40.9, 46.1) | 14.3 |

| 2 (9.4 to 9.7) | 21 | 40.0 (38.1, 41.7) | 8.6 |

| 3 (9.8 to 10.1) | 28 | 38.5 (37.0, 40.0) | 8.2 |

| 4 (≥10.2) | 29 | 36.6 (35.2, 38.1)*** | 7.8*** |

| Quartile of serum phosphorus | |||

| 1 (<3.4) | 18 | 42.1 (39.6, 44.3) | 11.7 |

| 2 (3.4 to 3.7) | 19 | 40.9 (38.5, 43.8) | 10.9 |

| 3 (3.8 to 4.1) | 31 | 38.5 (37.3, 39.6) | 7.2 |

| 4 (≥4.2) | 32 | 37.0 (35.5, 38.5)*** | 9.8*** |

| Quartile of 25(OH)D, ng/ml | |||

| 1 (< 17.6) | 23 | 47.5 (45.6, 49.4) | 19.0 |

| 2 (17.6 to 23.6) | 24 | 39.6 (38.1, 41.7) | 8.3 |

| 3 (23.7 to 30.2) | 27 | 38.9 (37.7, 40.9) | 7.0 |

| 4 (≥ 30.3) | 26 | 32.8 (31.5, 34.5)*** | 5.2*** |

PTH, intact parathyroid hormone; CI, confidence interval

*P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001

P values for age group, body mass index, and quartile of total calorie and calcium intake, serum 25(OH)D, serum phosphorus, and serum calcium are at a trend level.

Compared with non-Hispanic white;

Compared with participants who never smoked;

Compared with nondrinkers.

The distribution of serum iPTH for non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and Mexican-Americans overlapped substantially (Figure 1). However, the median and 75th and 90th percentiles of serum iPTH levels were higher among non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican-Americans compared with non-Hispanic whites. Specifically, the median iPTH levels were 37, 43, and 42 pg/ml; the 75th percentiles were 50, 58, and 56 pg/ml; and the 90th percentiles were 65, 78, and 72 pg/ml among non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and Mexican-Americans, respectively. The entire iPTH distribution overlapped for men and women, and the median and 75th and 90th percentiles were nearly identical (38, 51, and 69 pg/ml, respectively, for men, and 39, 52, and 68 pg/ml, respectively, for women; Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Distribution of intact serum parathyroid hormone by race-ethnicity among adults 20 yr and older who participated in the 2003–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Figure 2.

Distribution of serum intact parathyroid hormone among men and women 20 yr and older who participated in the 2003–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Figure 3 displays the age, race/ethnicity, and sex standardized median, and 75th and 90th percentiles of serum iPTH by eGFR. The median serum iPTH was < 50 pg/ml for eGFR levels ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. However, iPTH was higher at eGFR levels below 60 ml/min/1.73 m2; the median serum iPTH was 40 pg/ml at an eGFR of 59 ml/min/1.73 m2, and was 70 pg/ml at 30 ml/min/1.73 m2. A similar pattern was observed for the 75th and 90th percentiles of serum iPTH; levels were stable between an eGFR of 150 and 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, with a steep rise present at eGFR levels from 59 to 30 ml/min/1.73 m2.

Figure 3.

Median (50th percentile) and 75th and 90th percentiles of intact parathyroid hormone levels among adults 20 yr and older who participated in the 2003–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Geometric mean serum iPTH and the age-adjusted prevalence of elevated serum iPTH ≥ 70 pg/ml was higher at lower eGFR categories (Table 2). After adjustment for age, race/ethnicity, and sex, and multivariate adjustment, the prevalence ratios of elevated serum iPTH were progressively higher with lower eGFR levels. No association was present between eGFR and low serum calcium levels. There was a trend toward higher prevalence of elevated serum phosphorus at lower eGFR levels, both before and after multivariable adjustment. The prevalence of 25(OH)D < 17.6 ng/ml was higher at lower eGFR levels. However, this association was no longer present after multivariate adjustment for serum iPTH, calcium, and phosphorus levels.

Table 2.

Geometric mean serum iPTH, calcium, phosphorus, and 25(OH)D and prevalence and prevalence ratios of serum iPTH ≥ 70 pg/ml, serum calcium < 9.4 mg/dl, serum phosphorus ≥ 4.2 mg/dl, and 25(OH)D < 17.6 ng/ml by estimated glomerular filtration rate

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (ml/min/1.73 m2)

|

P trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 60(n = 3,5560) | 45 to 59(n = 296) | 30 to 44(n = 97) | ||

| Geometric mean (95% CI) iPTH, pg/ml | 38.5 (37.0, 40.0) | 48.4 (44.8, 52.4) | 57.4 (48.1, 68.5) | <0.001 |

| Serum iPTH ≥70 pg/ml, %a | 8.2% | 19.3% | 38.3% | <0.001 |

| model 1, PR (95% CI)b | 1.00 (ref) | 2.75 (2.02, 3.75)*** | 5.23 (3.22, 8.50)*** | <0.001 |

| model 2, PR (95% CI)c | 1.00 (ref) | 2.46 (1.77, 3.43)*** | 5.25 (3.13, 8.80)*** | <0.001 |

| model 3, PR (95% CI)c | 1.00 (ref) | 2.30 (1.68, 3.14)*** | 4.69 (3.05, 7.19)*** | <0.001 |

| Mean serum calcium (SD), mg/dl | 9.80 (0.02) | 9.77 (0.06) | 9.58 (0.07) | 0.028 |

| Serum calcium <9.4 mg/dl, %a | 22.0 | 21.2 | 26.5 | 0.600 |

| model 1, PR (95% CI)b | 1.00 (ref) | 0.96 (0.70, 1.31) | 1.17 (0.78, 1.77) | 0.729 |

| model 2, PR (95% CI)c | 1.00 (ref) | 0.95 (0.66, 1.37) | 1.18 (0.73, 1.90) | 0.804 |

| model 3, PR (95% CI)d | 1.00 (ref) | 0.91 (0.62, 1.36) | 1.07 (0.67, 1.70) | 0.919 |

| Mean (SD) serum phosphorus, mg/dl | 3.83 (0.02) | 3.80 (0.04) | 3.91 (0.10) | 0.710 |

| Serum phosphorus ≥4.2 mg/dl, %a | 24.9 | 34.9 | 40.1 | 0.005 |

| model 1, PR (95% CI)b | 1.00 (ref) | 1.37 (0.99, 1.88) | 1.53 (1.00, 2.33)* | 0.011 |

| model 2, PR (95% CI)c | 1.00 (ref) | 1.34 (0.96, 1.85) | 1.54 (1.05, 2.24)* | 0.010 |

| model 3, PR (95% CI)d | 1.00 (ref) | 1.31 (0.94, 1.81) | 1.51 (0.99, 2.30) | 0.022 |

| Mean (95% CI) 25(OH)D, ng/ml | 25.0 (0.7) | 24.6 (0.8) | 23.2 (1.1) | 0.198 |

| 25(OH) D <17.6 ng/ml, %a | 22.3 | 29.3 | 39.3 | 0.009 |

| model 1, PR (95% CI)b | 1.00 (ref) | 1.45 (1.09, 1.93)* | 1.69 (1.07, 2.66)* | 0.003 |

| model 2, PR (95% CI)c | 1.00 (ref) | 1.26 (0.96, 1.65) | 1.58 (1.05, 2.37)* | 0.021 |

| model 3, PR (95% CI)d | 1.00 (ref) | 1.18 (0.88, 1.59) | 1.23 (0.86, 1.74) | 0.176 |

iPTH, serum intact parathyroid hormone; PR, prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval; ref, reference category.

*P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001 compared to the reference category.

Adjusted for age.

Model 1: Includes adjustment for age, race/ethnicity, and sex.

Model 2: Includes adjustment for age, race-ethnicity, sex, menopause status, income, education, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, vitamin D supplement use, and total calorie and dietary calcium intake.

Model 3: Includes adjustment for variables in Model 2 and serum iPTH ≥ 70 pg/ml, serum calcium < 9.4 mg/dl, serum phosphorus ≥ 4.2 mg/dl, and 25(OH)D < 17.6 ng/ml. N.B., iPTH model included adjustment for serum calcium, phosphorus, and 25(OH)D; calcium model included adjustment for serum iPTH, phosphorus, and 25(OH)D; phosphorus model included adjustment for serum iPTH, calcium and 25(OH)D; and 25(OH)D model included adjustment for serum iPTH, calcium, and phosphorus).

Table 3 summarizes risk factors for elevated iPTH. After adjustment for race/ethnicity and sex, older age was associated with an elevated serum iPTH. After adjustment for age and sex, non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican-Americans were more likely than non-Hispanic whites to have elevated serum iPTH. Furthermore, after adjustment for age, race/ethnicity, and sex, obesity, hypertension, and low levels of serum calcium, 25(OH)D, and eGFR were associated with elevated serum iPTH. Additionally, current smokers, compared to never smokers, and participants who consumed ≥ 2 drinks of alcohol per day versus nondrinkers, participants with higher dietary calcium intakes, and those who took vitamin D supplements were less likely to have elevated serum iPTH. These associations remained present, albeit attenuated, after multivariate adjustment. After multivariate adjustment, men were 1.55 (95% CI: 1.06, 2.27) times more likely than women to have elevated serum iPTH. Of note, adjustment for serum calcium, phosphorus, and 25(OH)D reduced the prevalence ratio of elevated serum iPTH for non-Hispanic blacks, compared with non-Hispanic whites, from 1.76 (95% CI: 1.31, 2.37) to 1.24 (95% CI: 0.94, 1.63). These results were consistent for persons with and without stage 3 CKD (data not shown).

Table 3.

Prevalence ratios (95% confidence interval) of intact serum parathyroid hormone ≥ 70 pg/ml associated with participant characteristics.

| Multivariate Adjusted 1a | Multivariate Adjusted 2b | Multivariate Adjusted 3c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group, years | |||

| <40 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 40 to 59 | 1.02 (0.58, 1.82) | 0.94 (0.54, 1.64) | 0.93 (0.53, 1.64) |

| 60 to 74 | 1.63 (0.92, 2.89) | 1.13 (0.61, 2.08) | 1.07 (0.59, 1.92) |

| ≥75 | 2.99 (1.94, 4.62)*** | 1.52 (0.95, 2.44) | 1.47 (0.94, 2.32) |

| Men | 1.07 (0.85, 1.36) | 1.30 (0.91, 1.87) | 1.55 (1.06, 2.27)* |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| non-Hispanic white | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| non-Hispanic black | 2.08 (1.55, 2.78)*** | 1.76 (1.31, 2.37)** | 1.24 (0.94, 1.63) |

| Mexican-American | 1.76 (1.13, 2.75)* | 1.85 (1.14, 2.98)* | 1.53 (0.94, 2.50) |

| Postmenopausal | 1.41 (0.81, 2.46) | 1.43 (0.82, 2.49) | 1.49 (0.85, 2.60) |

| Income <$20,000/yr | 1.09 (0.88, 1.35) | 1.13 (0.93, 1.38) | 1.15 (0.95, 1.40) |

| Education < high school diploma | 1.02 (0.70, 1.49) | 1.09 (0.76, 1.58) | 1.12 (0.81, 1.56) |

| Smoking | |||

| never | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| former | 0.80 (0.55, 1.16) | 0.81 (0.56, 1.17) | 0.82 (0.57, 1.17) |

| current | 0.57 (0.37, 0.86)* | 0.59 (0.41, 0.85) | 0.52 (0.37, 0.74)** |

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| none | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| >0 but <2 drinks per day | 0.76 (0.54, 1.09) | 0.81 (0.56, 1.18) | 0.85 (0.60, 1.21) |

| ≥2 drinks per day | 0.32 (0.10, 1.01) | 0.36 (0.12, 1.11) | 0.36 (0.12, 1.12) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | |||

| <25 (normal weight) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 25 to 29 (overweight) | 0.99 (0.65, 1.51) | 0.94 (0.65, 1.36) | 0.95 (0.66, 1.36) |

| ≥30 (obesity) | 1.64 (1.15, 2.34)** | 1.50 (1.06, 2.12)* | 1.32 (0.93, 1.87) |

| Hypertension | 1.20 (1.01, 1.41)* | 0.94 (0.70, 1.28) | 0.96 (0.73, 1.27) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.14 (0.71, 1.83) | 0.88 (0.55, 1.42) | 0.80 (0.48, 1.31) |

| Quartile of total calorie intake, kcal | |||

| 1 (<1,502) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 2 (1,502 to 2,071) | 0.72 (0.51, 1.02) | 0.93 (0.63, 1.37) | 0.91 (0.62, 1.32) |

| 3 (2,072 to 2,746) | 0.80 (0.55, 1.17) | 1.10 (0.71, 1.70) | 1.02 (0.66, 1.59) |

| 4 (≥2,747) | 1.06 (0.73, 1.54) | 1.74 (1.01, 3.00)* | 1.65 (0.97, 2.80) |

| Quartile of calcium intake, mg | |||

| 1 (<559) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 2 (559 to 841) | 0.87 (0.63, 1.18) | 0.80 (0.57, 1.12) | 0.83 (0.59, 1.17) |

| 3 (842 to 1259) | 0.86 (0.59, 1.26) | 0.75 (0.49, 1.13) | 0.82 (0.54, 1.24) |

| 4 (≥1,260) | 0.70 (0.52, 0.94)* | 0.58 (0.40, 0.85)** | 0.65 (0.43, 0.98)* |

| Vitamin D supplement use | 0.49 (0.30, 0.79)** | 0.56 (0.32, 0.98)* | 0.63 (0.37, 1.08) |

| Serum phosphorus ≥4.2 mg/dl | 1.12 (0.85, 1.48) | – | 1.14 (0.87, 1.49) |

| Serum calcium <9.4 mg/dl | 1.60 (1.18, 2.17)** | – | 1.45 (1.09, 1.93)* |

| 25(OH)D <17.6 ng/ml | 2.46 (1.83, 3.29)*** | – | 2.10 (1.55, 2.86)*** |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | |||

| ≥60 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 45 to 59 | 2.75 (2.02, 3.75)*** | 2.46 (1.77, 3.43)*** | 2.30 (1.68, 3.14)*** |

| 30 to 44 | 5.23 (3.22, 8.50)*** | 5.25 (3.13, 8.80)*** | 4.69 (3.05, 7.19)*** |

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

–not included in regression model.

* P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001.

Multivariate model 1 includes adjustment for age, race-ethnicity, and sex.

Multivariate model 2 includes adjustment for age, race-ethnicity, sex, menopause status, income, education, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, vitamin D supplement use, total calorie and dietary calcium intake, and eGFR.

Multivariate model 3 includes adjustment for variables in multivariate model 2 and serum calcium < 9.4 mg/dl, serum phosphorus ≥ 4.2 mg/dl, and 25(OH)D < 17.6 ng/ml.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate a strong association between moderate CKD and a higher prevalence of elevated serum iPTH levels in a large, nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. The prevalence of elevated serum iPTH, defined in the current study as ≥ 70 pg/ml, was higher at lower eGFR levels. Given estimates that 15 to 16 million U.S. adults have an eGFR below 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, this finding may have far-reaching public health significance for musculoskeletal and cardiovascular outcomes in these individuals (24).

For the 2003 K/DOQI guidelines, an evidence review team identified several studies, mostly with small sample sizes, of the association between renal function, before the need for dialysis treatment, and serum iPTH levels (13). More recently, a graded association between lower eGFR and a higher prevalence of iPTH ≥ 65 pg/ml was reported among a moderate-size population of patients (N = 1814) recruited from clinical offices in the United States and Canada and enrolled in the Study for the Early Evaluation of Kidney Disease (25). The current study extends previous findings to a large, nationally representative sample of the U.S. population. In addition, independent predictors of elevated iPTH levels were identified in the study presented here.

Non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican-Americans in this study were more likely to have elevated iPTH compared with non-Hispanic whites. This finding is consistent with a previous study of patients with CKD that reported blacks to have higher iPTH compared with nonblacks (26). Although a previous study has reported higher dietary calcium intake among whites compared with blacks in the United States, adjustment for dietary calcium intake did not fully explain the higher prevalence of elevated iPTH among non-Hispanic blacks in this study (27). On the basis of our data, lower serum 25(OH)D levels appear to explain a substantial proportion of the higher levels of elevated iPTH in non-Hispanic blacks. Interestingly, Mexican-Americans in the current study also had higher iPTH levels compared with non-Hispanic whites. Few data have been published on iPTH levels among Mexican-Americans. Given the strong association between elevated serum iPTH and health outcomes and the high incidence of stage 5 CKD among non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican-Americans, correcting elevated iPTH in these populations warrants attention.

Consistent with previous studies, we found an association between current smoking and alcohol consumption and a lower prevalence of elevated iPTH (28,29). It has been hypothesized that smoking causes an increase in plasma ionized calcium or chromogranin peptides and decreased bone formation, and that there is a direct toxic effect of cigarette smoke on parathyroid cells (29,30). Also, alcohol consumption has been shown in vitro as well as in two human studies to reduce osteoblast activity (31–33). Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms underlying the associations of cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption with lower levels of iPTH.

The 2003 K/DOQI guidelines recommend routine measurement of 25(OH)D levels in all patients with CKD and iPTH levels above the target range, and treatment with vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) supplementation if serum 25(OH)D levels are < 30 ng/ml. This recommendation is based on the observation that reductions in 25(OH)D, the substrate for renal production of 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D, are associated with compensatory increases in serum iPTH levels in individuals with normal renal function. When the concentration of 25(OH)D exceeds 30 ng/ml, vitamin D supplementation no longer decreases serum iPTH levels (34). Therefore, 25(OH)D deficiency may aggravate elevations in serum iPTH in CKD, and the prevention of vitamin D deficiency may reduce the frequency and severity of secondary hyperparathyroidism. The majority of the adults with reduced eGFR in this study had 25(OH)D levels < 30 ng/ml, highlighting the need for measuring vitamin D levels in CKD.

The data presented here also support a role for 25(OH)D deficiency in the etiology of elevated iPTH in CKD. For example, black race and obesity are recognized risk factors for 25(OH)D deficiency. Blacks have a markedly increased risk of 25(OH)D deficiency, largely as a result of the decreased ability of pigmented skin to synthesize vitamin D3 after exposure to sunlight (35). Multiple studies have demonstrated that obesity is associated with lower 25(OH)D levels and higher PTH levels (36–38). In our study, adjustment for 25(OH)D levels attenuated markedly, but did not fully explain, the associations between these risk factors and elevated PTH levels.

Data from experimental models suggest that iPTH has direct trophic effects on myocardial myocytes and interstitial fibroblasts (39,40). Importantly, higher serum iPTH levels in the context of stage 5 CKD have been associated with increased cardiovascular disease and mortality (41). Furthermore, a relationship between abnormal mineral metabolism and vascular health has been reported in previous epidemiologic studies of the general and stage 5 CKD populations (42). Abnormalities in mineral metabolism may lead to calcification of soft tissues and vascular tissue. Schulz and colleagues described an association between rates of spinal bone loss and aortic calcification in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis (43). Also, Braun and colleagues reported a correlation between lower bone mass and higher coronary artery calcium (r = 0.47, P < 0.05) among a group of dialysis patients (44). London and colleagues described a strong association between arterial calcification, assessed by ultrasonography, adynamic bone disease, and reduced bone remodeling in hemodialysis patients (45).

Low serum calcium and 25(OH)D and high serum phosphorus levels are common among patients with ESRD. Fewer data have been published on the association between these abnormalities across the full range of eGFR (46). In the current study, there was no association between serum calcium and eGFR. In contrast, high serum phosphorus was more common at lower eGFR levels. Previous studies have reported this association and suggested that elevated phosphorus may be responsible for the increased serum iPTH levels seen in stage 3 CKD (47). This is a difficult area to study, because high serum iPTH increases urinary phosphorus excretion. This was observed in the current study: Participants with higher serum iPTH had lower serum phosphorus levels. Nonetheless, a strong association between eGFR and elevated serum iPTH remained present after adjustment for serum calcium, phosphorus, and 25(OH)D levels. There are several potential explanations for this finding. Because high serum iPTH increases urinary phosphorus excretion, adjustment for serum phosphorus may not fully capture the etiology of elevated iPTH. Serum levels of 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D are likely to be reduced in participants with decreased eGFR, because of reductions in nephron mass and 1-α-hydroxylase activity. Deficiency in 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D promotes parathyroid gland hyperplasia and increased PTH synthesis (48). Also, the accumulation of iPTH fragments occurs in participants with CKD (7). NHANES 2003–2004 did not have data on 1,25(OH)2D or PTH fragments precluding its investigation in the current study.

Additional limitations of the current study include its cross-sectional design. Prospective data are needed to estimate the increases in serum iPTH levels because kidney function decreases with age. Another limitation is there were too few participants with stage 4 CKD (i.e. eGFR: 15 to 29 ml/min/1.73 m2; n = 35) to obtain valid levels of serum iPTH for this group. In addition, the MDRD study equation, which we used to calculate eGFR, is not as accurate in estimating GFR > 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Despite these limitations, the current study maintains several strengths. NHANES 2003–2004 included a large nationally representative sample of U.S. adults with a broad spectrum of eGFR. In addition, non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican-Americans were oversampled, permitting reliable estimates in these population subgroups. Also, this study had a broad collection of data including serum levels of iPTH, calcium, phosphorus, and 25(OH)D. Furthermore, this study is the first to identify risk factors for elevated iPTH, including low calcium intake and obesity. These data were collected using standardized protocols with rigorous quality control procedures.

In summary, using a sample of the general US population, the current study provides a description of the prevalence of elevated serum iPTH levels across a broad spectrum of kidney function. Although serum iPTH levels were similar at eGFR levels ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, a steep increase in serum iPTH levels and the prevalence of serum iPTH ≥ 70 mg/ml was present at eGFR levels of 59 to 30 ml/min/1.73 m2. This association was independent of dietary intake of calcium and serum levels of calcium, phosphorus, and 25(OH)D. Given its association with adverse outcomes in CKD, reducing serum iPTH levels may be an important goal for improving quality of life and preventing adverse health outcomes.

Disclosures

None.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Danese MD, Kim J, Doan QV, Dylan M, Griffiths R, Chertow GM: PTH and the risks for hip, vertebral, and pelvic fractures among patients on dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 47: 149–156, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallieni M, Cucciniello E, D'Amaro E, Fatuzzo P, Gaggiotti A, Maringhini S, Rotolo U, Brancaccio D: Calcium, phosphate, and PTH levels in the hemodialysis population: A multicenter study. J Nephrol 15: 165–170, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torres A, Lorenzo V, Hernandez D, Rodriguez JC, Concepcion MT, Rodriguez AP, Hernandez A, de Bonis E, Darias E, Gonzalez-Posada JM: Bone disease in predialysis, hemodialysis, and CAPD patients: Evidence of a better bone response to PTH. Kidney Int 47: 1434–1442, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coburn JW, Elangovan L: Prevention of metabolic bone disease in the pre-end-stage renal disease setting. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: S71–S77, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Llach F, Massry SG, Singer FR, Kurokawa K, Kaye JH, Coburn JW: Skeletal resistance to endogenous parathyroid hormone in pateints with early renal failure. A possible cause for secondary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 41: 339–345, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fajtova VT, Sayegh MH, Hickey N, Aliabadi P, Lazarus JM, LeBoff MS: Intact parathyroid hormone levels in renal insufficiency. Calcif Tissue Int 57: 329–335, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brossard JH, Cloutier M, Roy L, Lepage R, Gascon-Barre M, D'Amour P: Accumulation of a non-(1–84) molecular form of parathyroid hormone (PTH) detected by intact PTH assay in renal failure: Importance in the interpretation of PTH values. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81: 3923–3929, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rix M, Andreassen H, Eskildsen P, Langdahl B, Olgaard K: Bone mineral density and biochemical markers of bone turnover in patients with predialysis chronic renal failure. Kidney Int 56: 1084–1093, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez I, Saracho R, Montenegro J, Llach F: The importance of dietary calcium and phosphorous in the secondary hyperparathyroidism of patients with early renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis 29: 496–502, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coen G, Mazzaferro S, Ballanti P, Sardella D, Chicca S, Manni M, Bonucci E, Taggi F: Renal bone disease in 76 patients with varying degrees of predialysis chronic renal failure: A cross-sectional study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 11: 813–819, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fried LF, Biggs L, Shlipak MG, Seliger S, Kestenbaum B, Stehman-Breen C, Sarnak M, Siscovick D, Harris T, Cauley J, Newman AB, Robbins J: Association of kidney function with incidence hip fracture in older adults. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 282–286, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nickolas TL, McMahon DJ, Shane E: Relationship between moderate to severe kidney disease and hip fracture in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 3223–3232, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Kidney Foundation: K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for bone metabolism and disease in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 42: S1–201, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gretz N, Giovanetti S, Barsotti G, Schmicker R, Rosman G: Influence of dietary treatment on the rate of progression of chronic renal failure. In: Nutritional Treatment of Chronic Renal Failure, edited by Giovanetti S, Boston MA, Kluwer, 1989, pp 211–229

- 15.Barsotti G, Cupisti A, Ciardella F, Morelli E, Niosi F, Giovannetti S: Compliance with protein restriction: Effects on metabolic acidosis and progression of renal failure in chronic uremics on supplemented diet. Contrib Nephrol 81: 42–49, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andress DL: Vitamin D treatment in chronic kidney disease. Semin Dial 18: 315–321, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez JD, Wesseling K, Salusky IB: Role of parathyroid hormone and therapy with active vitamin D sterols in renal osteodystrophy. Semin Dial 18: 290–295, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunningham J, Sprague SM, Cannata-Andia J, Coco M, Cohen-Solal M, Fitzpatrick L, Goltzmann D, Lafage-Proust MH, Leonard M, Ott S, Rodriguez M, Stehman-Breen C, Stern P, Weisinger J: Osteoporosis in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 43: 566–571, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malluche HH, Langub MC, Monier-Faugere MC: Pathogenesis and histology of renal osteodystrophy. Osteoporos Int 7 [Suppl 3]: S184–S187, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES 2003–2004. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhanes/nhanes2003–2004/nhanes03_04.htm. Accessed 9–1- 2006

- 21.Souberbielle JC, Boutten A, Carlier MC, Chevenne D, Coumaros G, Lawson-Body E, Massart C, Monge M, Myara J, Parent X, Plouvier E, Houillier P: Inter-method variability in PTH measurement: Implication for the care of CKD patients. Kidney Int 70: 345–350, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hollis BW, Kamerud JQ, Selvaag SR, Lorenz JD, Napoli JL: Determination of vitamin D status by radioimmunoassay with an 125I-labeled tracer. Clin Chem 39: 529–533, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, Kausz AT, Levin A, Steffes MW, Hogg RJ, Perrone RD, Lau J, Eknoyan G: National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med 139: 137–147, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van LF, Levey AS: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 298: 2038–2047, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levin A, Bakris GL, Molitch M, Smulders M, Tian J, Williams LA, Andress DL: Prevalence of abnormal serum vitamin D, PTH, calcium, and phosphorus in patients with chronic kidney disease: results of the study to evaluate early kidney disease. Kidney Int 71: 31–38, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gutierrez OM, Isakova T, Andress DL, Levin A, Wolf M: Prevalence and severity of disordered mineral metabolism in Blacks with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 73: 956–962, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kant AK, Graubard BI, Kumanyika SK: Trends in black-white differentials in dietary intakes of U.S. adults, 1971–2002. Am J Prev Med 32: 264–272, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.az-Gomez NM, Mendoza C, Gonzalez-Gonzalez NL, Barroso F, Jimenez-Sosa A, Domenech E, Clemente I, Barrios Y, Moya M: Maternal smoking and the vitamin D-parathyroid hormone system during the perinatal period. J Pediatr 151: 618–623, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jorde R, Saleh F, Figenschau Y, Kamycheva E, Haug E, Sundsfjord J: Serum parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels in smokers and non-smokers. The fifth Tromso study. Eur J Endocrinol 152: 39–45, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Need AG, Kemp A, Giles N, Morris HA, Horowitz M, Nordin BE: Relationships between intestinal calcium absorption, serum vitamin D metabolites and smoking in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 13: 83–88, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laitinen K, Lamberg-Allardt C, Tunninen R, Karonen SL, Tahtela R, Ylikahri R, Valimaki M: Transient hypoparathyroidism during acute alcohol intoxication. N Engl J Med 324: 721–727, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perry HM, III, Horowitz M, Fleming S, Kaiser FE, Patrick P, Morley JE, Cushman W, Bingham S, Perry HM, Jr.: Effect of recent alcohol intake on parathyroid hormone and mineral metabolism in men. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 22: 1369–1375, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rico H, Cabranes JA, Cabello J, Gomez-Castresana F, Hernandez ER: Low serum osteocalcin in acute alcohol intoxication: A direct toxic effect of alcohol on osteoblasts. Bone Miner 2: 221–225, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malabanan A, Veronikis IE, Holick MF: Redefining vitamin D insufficiency. Lancet 351: 805–806, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clemens TL, Adams JS, Henderson SL, Holick MF: Increased skin pigment reduces the capacity of skin to synthesise vitamin D3. Lancet 1: 74–76, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parikh SJ, Edelman M, Uwaifo GI, Freedman RJ, Semega-Janneh M, Reynolds J, Yanovski JA: The relationship between obesity and serum 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D concentrations in healthy adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89: 1196–1199, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Looker AC: Body fat and vitamin D status in black versus white women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90: 635–640, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Snijder MB, van Dam RM, Visser M, Deeg DJ, Dekker JM, Bouter LM, Seidell JC, Lips P: Adiposity in relation to vitamin D status and parathyroid hormone levels: A population-based study in older men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90: 4119–4123, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schluter KD, Piper HM: Trophic effects of catecholamines and parathyroid hormone on adult ventricular cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol 263: H1739–H1746, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amann K, Ritz E, Wiest G, Klaus G, Mall G: A role of parathyroid hormone for the activation of cardiac fibroblasts in uremia. J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1814–1819, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horl WH: The clinical consequences of secondary hyperparathyroidism: Focus on clinical outcomes. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19 [Suppl 5]: V2–V8, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goodman WG: The consequences of uncontrolled secondary hyperparathyroidism and its treatment in chronic kidney disease. Semin Dial 17: 209–216, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schulz E, Arfai K, Liu X, Sayre J, Gilsanz V: Aortic calcification and the risk of osteoporosis and fractures. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89: 4246–4253, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Braun J, Oldendorf M, Moshage W, Heidler R, Zeitler E, Luft FC: Electron beam computed tomography in the evaluation of cardiac calcification in chronic dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 27: 394–401, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.London GM, Marty C, Marchais SJ, Guerin AP, Metivier F, de Vernejoul MC: Arterial calcifications and bone histomorphometry in end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1943–1951, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hsu CY, Chertow GM: Elevations of serum phosphorus and potassium in mild to moderate chronic renal insufficiency. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17: 1419–1425, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pitts TO, Piraino BH, Mitro R, Chen TC, Segre GV, Greenberg A, Puschett JB: Hyperparathyroidism and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D deficiency in mild, moderate, and severe renal failure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 67: 876–881, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schomig M, Ritz E: Management of disturbed calcium metabolism in uraemic patients: 1. Use of vitamin D metabolites. Nephrol Dial Transplant 15 [Suppl 5]: 18–24, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]