Abstract

Background and objectives: Low birth weight (LBW), resulting from intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) or prematurity, is a risk factor for adult hypertension and chronic kidney disease. LBW is associated with reduced nephron endowment and increased glomerular volume; however, the development of secondary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) has not been reported previously.

Design, setting, participants & measurements: The authors describe six patients with clinical and pathologic findings suggesting a secondary form of FSGS, in whom a history of prematurity and very LBW was obtained. No other known causes of secondary FSGS were identified.

Results: The cohort consisted of two women and four men with a mean age of 32 yr. Patients were born at 22 to 30 wk gestation with mean birth weight of 1054 g (range 450 to 1420 g). Mean 24-h urine protein was 3.3 g/d (range 1.3 to 6.0 g/d), mean creatinine clearance 89 cc/min (range 71 to 132 cc/min), mean creatinine 1.2 mg/dl (range 0.9 to 1.5 mg/dl), and mean serum albumin 4.1 g/dl (range 3.4 to 4.8 g/dl). No patient had full nephrotic syndrome. Renal biopsy revealed FSGS involving a minority (mean 8.8%) of glomeruli, with a predominance of perihilar lesions of sclerosis (five of six patients), glomerulomegaly (all six patients), and only mild foot process effacement (mean 32%), all features typical of postadaptive FSGS.

Conclusions: Our findings support that very LBW and prematurity promote the development of secondary FSGS. Because birth history is often not obtained by adult nephrologists, this risk factor is likely to be underrecognized.

The index case is a 15-yr-old Caucasian male who was found to have mild proteinuria during routine urinary screening. His birth was complicated by prematurity (23 wk gestational age) and a very low birth weight (1.40 kg). He had had numerous perinatal problems associated with prematurity including respiratory complications, intracranial hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, bowel obstruction, sepsis, and retinopathy of prematurity. There was no history of hematuria, urinary reflux, renal insufficiency, recent fevers, hearing loss, or familial renal disease. He was taking no medications. The patient was followed for several weeks and was found to have persistent, mild proteinuria not associated with exercise or posture (nonorthostatic).

Physical examination revealed a height of 172 cm and a weight of 75 kg (body mass index = 25.4 kg/m2), BP of 127/79 mmHg (90th percentile), and no edema. Renal ultrasound revealed normal-appearing kidneys measuring 10.5 cm and 9.6 cm in length. Laboratory examination showed a hematocrit of 50% (normal = 37% to 45%), white blood cell count 7.8 × 109/L (normal = 4.5 to 13.5 × 109/L) with normal differential, platelet count 221 × 109/L (normal 150 to 450 × 109/L), blood urea nitrogen 15 mg/dl (5.8 mmol/L) (normal = 7 to 18 mg/dl [2.5 to 6.4 mmol/L]), creatinine clearance 100 cc/min, serum creatinine 0.9 mg/dl (75.6 μmol/L), total serum protein 7.3 g/dl (73 g/L) (normal 6 to 8.2 g/dl [60 to 82 g/L]), and serum albumin 4.4 g/dl (44 g/L) (normal 3.4 to 5.0 g/dl [34 to 50 g/L]). Serum electrolytes, including sodium, potassium, bicarbonate, chloride, and calcium, were normal. The following serologies were negative: anti-nuclear antibody, anti–double-stranded DNA antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen, and hepatitis C antibody. Serum complement levels, including C3 and C4, were within normal range. Urinalysis revealed a specific gravity of 1.030, pH 5, and protein > 300 mg/dl, with negative glucose, heme and leukocyte esterase. The 24-h urinary protein was 1.34 g. Microscopic examination of the urine revealed zero to five white blood cells per high-power field, no red blood cells, and no hyaline or granular casts. A renal biopsy was performed to determine the cause of persistent subnephrotic proteinuria.

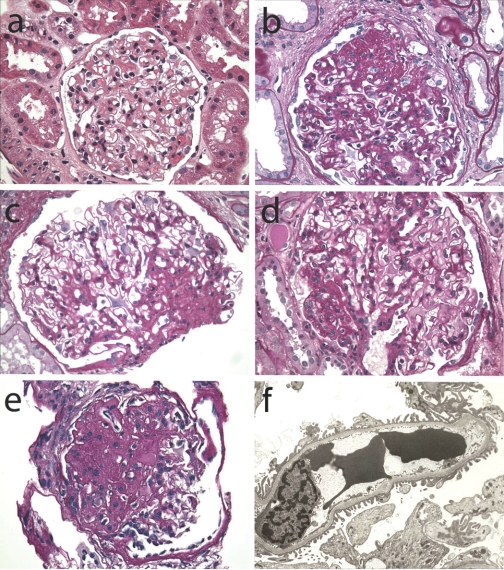

Light microscopic examination showed one core of tissue consisting of renal cortex and a small portion of outer medulla. There were 8 glomeruli, none of which were globally sclerotic. The glomeruli appeared hypertrophied but normocellular, with patent capillaries and glomerular basement membranes of normal thickness. No immune-type fuchsinophilic deposits were identified with the trichrome stain. There was patchy, mild tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis involving approximately 20% of the cortex, with sparse interstitial infiltrates confined to those areas. Nonatrophic tubules appeared hypertrophied. There was mild, focal arteriolosclerosis; interlobular arteries appeared unremarkable. One of the four glomeruli sampled for immunofluorescence showed 2+ segmental tuft staining for IgM and C3. There was negative staining for IgG, IgA, C1, fibrinogen, and kappa and lambda light chains. The cryostat sections were stained with PAS; light microscopic examination disclosed one glomerulus containing a discrete segmental lesion of sclerosis in the perihilar location (Figure 1e).

Figure 1.

Renal biopsy findings. (a) Normal sized control glomerulus (hematoxylin and eosin stain; original Magnification: ×40). (b-e) Representative glomeruli from Patients 1, 2, 5, and 6 demonstrate glomerulomegaly and segmental occlusion of glomerular capillaries by matrix accumulation and hyalinosis in a perihilar distribution in all but one (b) (PAS stain; original magnification: ×40). Patient 6, the index case, is (e). (f) Ultrastructural examination of a glomerular capillary from Patient 4 demonstrates minimal foot process effacement (electron micrograph; original magnification: ×5000)

Ultrastructural evaluation revealed normocellular glomeruli with patent capillaries and unremarkable mesangium. No glomeruli with segmental lesions of sclerosis were sampled. No glomerular immune-type electron-dense deposits or endothelial tubuloreticular inclusions were identified. Glomerular basement membranes appeared normal in thickness, texture, and contour, without evidence of thinning or lamellation. There was irregular effacement of foot processes involving approximately 45% of the glomerular capillary surface area. The proximal tubular epithelial cells were unremarkable. No intracytoplasmic storage material or dystrophic mitochondria were identified.

Differential diagnosis for the renal biopsy findings included primary and secondary forms of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS). The lack of glomerular basement membrane thinning and lamellation ruled out a secondary pattern of FSGS due to Alport syndrome. The subnephrotic proteinuria and absence of full nephrotic syndrome, the presence of glomerular hypertrophy, the relatively mild foot process effacement, and the perihilar distribution of segmental sclerosis favored a secondary form of FSGS due to structural–functional adaptation. In the absence of obesity, renal agenesis or reflux, and in the setting of prematurity and very LBW, FSGS secondary to low nephron endowment was proposed.

After receipt of the renal biopsy results, the patient was started on an ACE inhibitor. After 6 mo of therapy, the patient had a serum creatinine of 0.9 mg/dl, a serum albumin of 4.5 mg/dl, and a urine protein to creatinine ratio of 0.2.

Introduction

Accumulating evidence supports the relationship between low birth weight (LBW) and adult diseases. In the 1980s, Barker et al. (1) proposed the theory of the fetal origins of adult disease, on the basis of epidemiologic associations between LBW and hypertension. Subsequently, LBW has been associated with increased risk for coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes (2). The theory proposes that adverse conditions in utero affect fetal programming and lead to increased susceptibility to chronic disease later in life. Brenner and colleagues later postulated that intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) not only causes LBW, but also results in a congenital deficit of nephrons, leading to glomerular and systemic hypertension and reduced kidney function (3).

FSGS secondary to structural–functional adaptations is a pattern of injury mediated by elevated glomerular capillary pressures and flow rates that occur as an adaptive response to an increase in hemodynamic stress. Hemodynamic stress may occur with a normal endowment of nephrons (as in hypertension, obesity, cyanotic congenital heart disease, sickle cell anemia) or through a reduction in the number of functioning nephrons (unilateral renal agenesis, surgical ablation, reflux, or any advanced disease) (4). Postadaptive FSGS typically manifests absence of full nephrotic syndrome, glomerulomegaly, perihilar lesions of FSGS, and mild foot process effacement (5,6). Although autopsy studies have found a direct correlation between LBW and low nephron endowment and an inverse correlation between LBW and glomerular size (7,8), the occurrence of secondary (postadaptive) FSGS in this setting has not been reported.

We report the first series of patients with clinical–pathologic features of postadaptive FSGS associated with prematurity and very LBW, in the absence of other known risk factors for secondary FSGS.

Materials and Methods

A cohort of six patients (including the index case above) was identified from the archives of the Columbia Renal Pathology Laboratory between 2000 and 2007 with clinical and pathologic findings suggesting a secondary form of FSGS and a history of prematurity and very LBW. All renal biopsy samples were processed by standard techniques of light microscopy, immunofluorescence (IF), and electron microscopy, with the exception of one case (patient #3) in which electron microscopy was not performed. For each case, 11 glass slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff, trichrome, and Jones methenamine silver were reviewed. The index case required reprocessing of frozen tissue for light microscopy to demonstrate the segmental lesion of glomerulosclerosis. Glomerular tuft diameter was measured from all glomeruli cut at or near the hilus, as described previously (9). The glomerular diameter was measured in a total of 11 to 32 glomeruli (mean 22) per case using a reticle with ocular micrometer (Olympus Scientific, Tokyo, Japan), and means were calculated. IF was performed on 3-μm cryostat sections using polyclonal FITC-conjugated antibodies to IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, C1q, kappa, lambda, fibrinogen, and albumin (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). The intensity of IF staining was graded on a scale of 0 to 3+. Ultrastructural evaluation was performed using a JEOL 100S (Peabody, MA) electron microscope.

Patient records were reviewed for age, sex, renal presentation, medical history (including hypertension and diabetes), and birth history. A clinical–pathologic diagnosis of probable secondary FSGS was based on the absence of full nephrotic syndrome, the presence of focal and segmental sclerosis and hyalinosis of the glomerular tuft preferentially affecting the perihilar region, prominent glomerulomegaly, and mild foot process effacement. In all cases, a history of LBW was sought when no other potential risk factor for secondary FSGS could be identified clinically or pathologically.

Results

The clinical features are listed in Table 1. The cohort consisted of two women and four men, including two African American, one Hispanic, and three Caucasian, with a mean age of 32 yr (range 15 to 53 yr). No patient had a history of diabetes or long-standing hypertension, but four patients had elevated BP of recent onset. No patient had a history of HIV infection, intravenous drug abuse, vesicoureteral reflux, solitary kidney, dysplasia, chronic pyelonephritis, sickle cell disease (HbSS), or other known causes of secondary FSGS. One (patient #4) had mild obesity (BMI = 31.9) due to recent postpartum weight gain. All patients in the cohort were born premature (< 37 wk), and five had documented birth weights less than 1500 g (considered very LBW), with a mean birth weight of 1054 g (range, 450 to 1420 g). Exact gestational age and weight at birth were not available for patient 1, who gave a history of being “extremely premature” and having a “very low” birth weight. All patients presented with proteinuria (mean 24-h urine protein 3.3 g/d; range 1.3 to 6.0 g/d), three of whom were in the nephrotic range, but no patient had nephrotic syndrome. Only one patient presented with edema, and no patient had significantly reduced serum albumin (mean 4.1 g; range 3.4 to 4.8 g). Mean serum creatinine level was 1.2 mg/dl (range 0.9 to 1.5 mg/dl), and mean creatinine clearance was 89 cc/min (range 71 to 132 cc/min). Only one patient had microhematuria.

Table 1.

Clinical findings in patients with very low birth weight-related FSGS

| Characteristic | Patient no.

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Age / race / sex | 52 / B / F | 29 / H / M | 53 / W / M | 25 / B / F | 17 / W / M | 15 / W / M |

| Diabetes present | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.7 | 27.9 | 26.1 | 31.9 | 21 | 25.4 |

| New-onset hypertension | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Gestation (weeks) | Extremely premature | 26 | 30 | 22 | 24 | 23 |

| Birth weight (g) | Very low | 1400 | 1420 | 450 | 600 | 1400 |

| Edema | Trace | No | Moderate | No | No | No |

| 24 h urine protein (g) | 6 | 3.6 | 5.1 | 1.7 | 2 | 1.3 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 4.1 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 4.8 | 4.4 |

| Urinalysis | 3+ protein, inactive | N/A | 4+ protein, inactive | 3+ protein, 7 to 10 RBC | 3+ protein, inactive | 2+ protein, inactive |

| Creatinine clearance (cc/min)a | 74 | 71 | 73 | 85 | 132 | 100 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 1 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

Creatinine clearance was measured by 24-h urine collection in patients 2, 3, 5, and 6. For patients 1 and 4, creatinine clearance was estimated by the Cockcroft-Gault formula.

The pathologic features are listed in Table 2. Glomerular sampling for light microscopy ranged from 9 to 32 glomeruli. Global glomerulosclerosis involved a mean of 21% of glomeruli (range 0% to 41%), and tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis occupied a mean of 18% of the cortical area (range 5% to 30%). FSGS involved a minority of glomeruli (mean 8.8%; range 5% to 16%), with a predominance of perihilar lesions of sclerosis (five of six patients). Figure 1 shows a normal-sized control glomerulus (Figure 1a) and representative glomeruli from four of the six patients, including the index case (Figure 1b-e). These illustrate glomerular hypertrophy and predominantly perihilar segmental consolidation of the glomerular tuft by extracellular matrix and hyalinosis. Mean glomerular diameter in the LBW patients was 237 ± 14 μm (range 207 to 257), a value significantly greater (P < 0.001) than the previously published mean glomerular diameter of 21 normal controls (168 ± 12 μm; range 138 to 186 μm), and comparable to the glomerular diameter of patients with obesity related glomerulopathy (226 ± 24.6 μm; range 172 to 300 μm) (9). On IF, five cases demonstrated nonspecific trace to 2+ staining for IgM and C3 in areas of segmental glomerular sclerosis. One case (patient 5) had 1+ mesangial positivity for IgA without mesangial hypercellularity, with sparse, small paramesangial electron-dense deposits. No immune-type electron-dense deposits were identified in any other case. Ultrastructural examination revealed only mild foot process effacement (mean 32%; range 25% to 45%) (Figure 1f).

Table 2.

Pathologic findings in patients with very low birth weight-related FSGS

| Finding | Patient no.

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| No. of glomeruli | 20 | 32 | 9 | 25 | 14 | 12 |

| No. of globally sclerotic glomeruli (%) | 6 (30) | 13 (41) | 1 (11) | 5 (20) | 3 (21) | 0 |

| Tubular atrophy and fibrosis (% of cortex) | 15 | 30 | 5 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Glomerular diameter (μm; mean ± SD) | 241 ± 16 | 248 ± 13 | 254 ± 13 | 216 ± 14 | 257 ± 21 | 207 ± 14 |

| No. of segmentally sclerotic glomeruli (%) | 1 (5) | 2 (6) | 1 (11) | 4 (16) | 1 (7) | 1 (8) |

| Perihilar location | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Foot process effacement (%) | 30 | <25 | N/A | 30 | 30 | 45 |

Patient 5 also had minimal mesangial glomerulonephritis consistent with IgA nephropathy (1+ mesangial IgA by immunofluorescence; no mesangial hypercellularity)

Discussion

LBW has been defined by the World Health Organization as a weight at birth of less than 2500 g (5.5 pounds) and is a result of either intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) or preterm birth (before 37 wk gestation), in which birth weight may be low but appropriate for gestational age. Several epidemiologic studies have examined the association between LBW and kidney function. Lackland et al. (10) reported an inverse association between birth weight and ESRD from multiple causes in African Americans and Caucasians of either gender in the southeastern United States. More recently, data from a cohort of 526 subjects in Norway with 38 yr of follow-up revealed a 70% increaseed risk of ESRD associated with birth weights in <10th percentile compared with the 10th to 90th percentiles (11). The findings were also similar for men and women and persisted after adjustments for other birth-related variables. In a study of 422 19-yr-old subjects born very premature (gestational age <32 wk) in The Netherlands, lower birth weight was associated with higher serum creatinine, lower GFR, and microalbuminuria, independent of adult weight (12). The subjects who were small for gestational age had a prevalence of microalbuminuria twice as high as that of subjects with birth weights appropriate for gestational age, indicating that the combination of prematurity and IUGR imposes a greater risk of progressive renal failure in later life.

The human kidney contains on average approximately 850,000 glomeruli, with wide individual variation (7,13,14). Nephrogenesis in humans begins in the 9th week of gestation and continues up to the 36th week, with particularly rapid development during the last trimester. New nephrons are not formed after birth except in the case of extremely preterm infants, in whom nephrogenesis ceases approximately 40 d after birth (15). Thus, the final endowment of nephrons is dependent on a normal intrauterine environment and gestational age at birth. Hinchliffe et al. (16) demonstrated a reduced nephron number in growth-retarded stillbirths and liveborn IUGR infants who died within 1 yr compared with control infants with birth weights appropriate for gestational age. In a similar study of full-term neonates who died within 2 wk of birth, a significantly reduced nephron number was discovered in subjects with LBW (<2500 g) compared to subjects with normal birth weight (>2500 g) (8). In adults, an autopsy study of 122 men and women in the Southeastern United States revealed a significant correlation between birth weight and nephron number in Caucasians (7). Birth weight and nephron number were each inversely correlated with mean arterial pressure. Interestingly, the correlations were nonsignificant among African Americans, suggesting that there are differences in the pathomechanism of hypertension in this population. Using kidney size as a marker for nephron number, Schmidt et al. (17) found that LBW for gestational age had a stronger correlation with kidney size than crude birth weight (i.e. appropriate for gestational age) or gestational age alone, highlighting the importance of normal intrauterine growth. Where measured, an increased glomerular volume significantly correlated with low nephron number and LBW (7,8). This observation supports that in the setting of nephron deficit, glomeruli adapt through hypertrophy and hyperfiltration to maintain renal function. Over the long-term, this response becomes maladaptive, leading to progressive glomerulosclerosis and decline in renal function.

Normal birth weight, however, does not always indicate a normal nephron number. Oligomeganephronia, a type of renal hypoplasia that results from arrested development of the metanephric blastema at 14 to 20 wk gestation, is characterized by a reduced number of nephrons and marked compensatory hypertrophy of glomeruli and tubules. In six patients with oligomeganephronia, the four cases with significant proteinuria had FSGS on biopsy and rapidly progressed to end-stage disease (18).

Evidence supports a central role for podocyte depletion in postadaptive models of FSGS (19). As the glomeruli adapt through hypertrophy and hyperfiltration, podocyte connections to the basement membrane and other podocytes become mechanically strained. Because podocytes are terminally differentiated and unable to proliferate, the prolonged podocyte stress causes detachment and loss, producing synechiae and segmental sclerosis (20). In contrast to idiopathic (primary) FSGS, secondary forms of FSGS due to structural–functional adaptations typically exhibit glomerulomegaly and minimal foot process effacement. The lesions of segmental sclerosis typically involve a minority of glomeruli and have a tendency to be perihilar in distribution (5,6). In addition, patients usually manifest proteinuria in the subnephrotic or nephrotic range, without full nephrotic syndrome.

Important factors influencing fetal development are malnutrition and uteroplacental insufficiency, with the former more likely to be important in developing countries. Animal models of fetal growth restriction can be produced by maternal caloric reduction; maternal restriction of protein, sodium, or iron intake; placental embolization or surgical reduction of blood flow; and exposure to corticosteroids (21,22). These interventions often result in marked reduction in nephron number and kidney function in addition to effects on other organs. Molecular mechanisms that have been implicated include inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system in utero, reduced circulating insulin-like growth factor 1, and increased apoptosis (21,22).

Two cases had additional clinical and renal biopsy findings that merit further discussion. Patient 4 had a mildly elevated BMI (31.9) due to recent postpartum weight gain, raising the possibility of obesity-associated FSGS (9). Patient 5 had 1+ mesangial positivity for IgA by immunofluorescence without mesangial hypercellularity. The glomerulomegaly and focal sclerosis were clearly out of proportion to the minimal mesangial alterations, suggesting incidental IgA deposition. These cases, however, may be considered examples of the “two-hit ” hypothesis, which proposes that the low nephron number (first hit) may influence the presentation and modify the course of a subsequent renal injury (second hit). Indeed, LBW has been associated with a worse outcome in diverse renal diseases, including idiopathic membranous nephropathy, minimal change disease, and IgA nephropathy (23–25).

In summary, we report the first series of FSGS among patients with a history of prematurity and very low birth weight. Although the initial nephron deficit presumably occurred in utero, proteinuria was not detected until adolescence or adulthood, indicating a latent period before renal manifestations become clinically manifest. Because birth history is not often obtained in adults presenting with proteinuria, this association is likely to be underrecognized. The clinical–pathologic findings, including glomerulomegaly, perihilar segmental sclerosis, minimal foot process effacement, and proteinuria in the absence of nephrotic syndrome, strongly favor a secondary form of FSGS. We conclude that low nephron endowment per se promotes the development of secondary FSGS, in addition to being a risk factor for progressive glomerulosclerosis in diverse renal diseases. LBW should be added to the list of predisposing conditions sought in patients with renal biopsy findings suggestive of secondary FSGS.

Disclosures

None.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Developmental Origins of Renal Disease: Should Nephron Protection Begin at Birth?” on pages 10–13.

References

- 1.Barker DJ, Osmond C, Golding J, Kuh D, Wadsworth ME: Growth in utero, blood pressure in childhood and adult life, and mortality from cardiovascular disease. BMJ 298: 564–567, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker DJ: Adult consequences of fetal growth restriction. Clin Obstet Gynecol 49: 270–283, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner BM, Chertow GM: Congenital oligonephropathy and the etiology of adult hypertension and progressive renal injury. Am J Kidney Dis 23: 171–175, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rennke HG, Klein PS: Pathogenesis and significance of nonprimary focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis. Am J Kidney Dis 13: 443–456, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Agati V: Pathologic classification of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Semin Nephrol 23: 117–134, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Agati VD, Fogo AB, Bruijn JA, Jennette JC: Pathologic classification of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: A working proposal. Am J Kidney Dis 43: 368–382, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughson MD, Douglas-Denton R, Bertram JF, Hoy WE: Hypertension, glomerular number, and birth weight in African Americans and white subjects in the southeastern United States. Kidney Int 69: 671–678, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manalich R, Reyes L, Herrera M, Melendi C, Fundora I: Relationship between weight at birth and the number and size of renal glomeruli in humans: A histomorphometric study. Kidney Int 58: 770–773, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kambham N, Markowitz GS, Valeri AM, Lin J, D'Agati VD: Obesity-related glomerulopathy: An emerging epidemic. Kidney Int 59: 1498–1509, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lackland DT, Bendall HE, Osmond C, Egan BM, Barker DJ: Low birth weights contribute to high rates of early-onset chronic renal failure in the Southeastern United States. Arch Intern Med 160: 1472–1476, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vikse BE, Irgens LM, Leivestad T, Hallan S, Iversen BM: Low birth weight increases risk for end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 151–157, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keijzer-Veen MG, Schrevel M, Finken MJ, Dekker FW, Nauta J, Hille ET, Frolich M, van der Heijden BJ: Microalbuminuria and lower glomerular filtration rate at young adult age in subjects born very premature and after intrauterine growth retardation. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2762–2768, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Douglas-Denton RN, McNamara BJ, Hoy WE, Hughson MD, Bertram JF: Does nephron number matter in the development of kidney disease? Ethn Dis 16: S2–40-45, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schreuder MF, Nauta J: Prenatal programming of nephron number and blood pressure. Kidney Int 72: 265–268, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodriguez MM, Gomez AH, Abitbol CL, Chandar JJ, Duara S, Zilleruelo GE: Histomorphometric analysis of postnatal glomerulogenesis in extremely preterm infants. Pediatr Dev Pathol 7: 17–25, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hinchliffe SA, Lynch MR, Sargent PH, Howard CV, Van Velzen D: The effect of intrauterine growth retardation on the development of renal nephrons. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 99: 296–301, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt IM, Chellakooty M, Boisen KA, Damgaard IN, Mau Kai C, Olgaard K, Main KM: Impaired kidney growth in low-birth-weight children: Distinct effects of maturity and weight for gestational age. Kidney Int 68: 731–740, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGraw M, Poucell S, Sweet J, Baumal R: The significance of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in oligomeganephronia. Int J Pediatr Nephrol 5: 67–72, 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D'Agati VD: Podocyte injury in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: Lessons from animal models (a play in five acts). Kidney Int 73: 399–406, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kriz W, Gretz N, Lemley KV: Progression of glomerular diseases: Is the podocyte the culprit? Kidney Int 54: 687–697, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schreuder M, Delemarre-van de Waal H, van Wijk A: Consequences of intrauterine growth restriction for the kidney. Kidney Blood Press Res 29: 108–125, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vuguin PM: Animal models for small for gestational age and fetal programming of adult disease. Horm Res 68: 113–123, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duncan RC, Bass PS, Garrett PJ, Dathan JR: Weight at birth and other factors influencing progression of idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 9: 875, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zidar N, Avgustin Cavic M, Kenda RB, Ferluga D: Unfavorable course of minimal change nephrotic syndrome in children with intrauterine growth retardation. Kidney Int 54: 1320–1323, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zidar N, Cavic MA, Kenda RB, Koselj M, Ferluga D: Effect of intrauterine growth retardation on the clinical course and prognosis of IgA glomerulonephritis in children. Nephron 79: 28–32, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]