Abstract

Objective To compare the tolerability of malaria chemoprophylaxis regimens in non-immune travellers.

Design Randomised, double blind, study with placebo run-in phase.

Setting Travel clinics in Switzerland, Germany, and Israel.

Main outcome measure Proportion of participants in each treatment arm with subjectively moderate or severe adverse events.

Participants 623 non-immune travellers to sub-Saharan Africa: 153 each received either doxycycline, mefloquine, or the fixed combination chloroquine and proguanil, and 164 received the fixed combination atovaquone and proguanil.

Results A high proportion of patients reported adverse events, even in the initial placebo group. No events were serious. The chloroquine and proguanil arm had the highest proportion of mild to moderate adverse events (69/153; 45%, 95% confidence interval 37% to 53%), followed by mefloquine (64/153; 42%, 34% to 50%), doxycycline (51/153; 33%, 26% to 41%), and atovaquone and proguanil (53/164; 32%, 25% to 40%) (P = 0.048 for all). The mefloquine and combined chloroquine and proguanil arms had the highest proportion of more severe events (n = 19; 12%, 7% to 18% and n = 16; 11%, 6% to 15%, respectively), whereas the combined atovaquone and proguanil and doxycycline arms had the lowest (n = 11; 7%, 2% to 11% and n = 9; 6%, 2% to 10%, respectively: P = 0.137 for all). The mefloquine arm had the highest proportion of moderate to severe neuropsychological adverse events, particularly in women (n = 56; 37%, 29% to 44% versus chloroquine and proguanil, n = 46; 30%, 23% to 37%; doxycycline, n = 36; 24%, 17% to 30%; and atovaquone and proguanil, n = 32; 20%, 13% to 26%: P = 0.003 for all). The highest proportion of moderate or severe skin problems were reported in the chloroquine and proguanil arm (n = 12; 8%, 4% to 13% versus doxycycline, n = 5; 3%, 1% to 6%; atovaquone and proguanil, n = 4; 2%, 0% to 5%; mefloquine, n = 2; 1%, 0% to 3%: P = 0.013).

Conclusions Combined atovaquone and proguanil and doxycyline are well tolerated antimalarial drugs. Broader experience with both agents is needed to accumulate reports of rare adverse events.

Introduction

Each year an estimated 50 million travellers visit malaria endemic areas. Around 30 000 cases of malaria are reported annually in non-endemic, industrialised countries, and this imported malaria remains a public health problem with its high mortality.1 Recommendations vary widely as to the optimum prophylactic treatments for travellers to high risk endemic areas, such as sub-Saharan Africa. Four regimens are currently available: mefloquine, combined atovaquone and proguanil, doxycycline, and combined chloroquine and proguanil.2-5 The lack of unanimity about which regimen to prescribe is mainly due to controversy about the tolerability of antimalarial drugs in non-immune, healthy travellers and a paucity of data from randomised controlled studies.

Two double blind studies found that tolerability to combined atovaquone and proguanil was better than to mefloquine or combined chloroquine and proguanil.6,7 We compared the tolerability of non-immune travellers to the four commonly recommended antimalarial regimens.

Participants and methods

Between 1998 and 2001, we recruited people seeking advice before travelling to malaria endemic areas. Inclusion criteria were a consultation at least 17 days before departure, written informed consent, age between 18 and 70 years, and planned travel for 1-3 weeks in sub-Saharan Africa (mainly Kenya and game parks in the Republic of South Africa). Exclusion criteria were known deficiency for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, a history of severe adverse events with any of the four study drugs or a contraindication for their use, pregnancy or unwillingness to adhere to reliable contraception, history of seizures, psychiatric disorders, severely impaired renal or hepatic function, concurrent or recent vaginal infections or bacterial enteric disorder, a history of photosensitivity, or unwillingness to adhere to the study protocol. Our study was not powered to evaluate the efficacy of the regimens for malaria prevention. No cases of malaria were reported for any study arm.

Assignment to regimen and masking

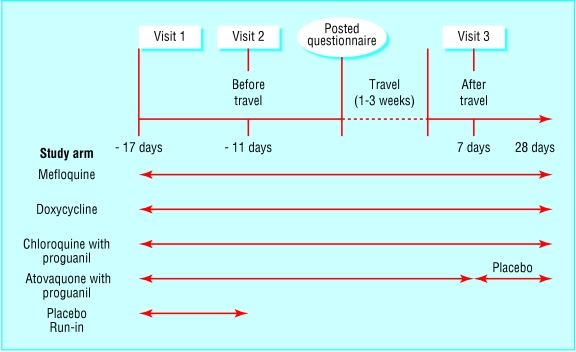

Participants received drugs daily for 17 days before departure, during the stay in Africa, and for four weeks after return (see fig 1). The treatment groups were assigned the following regimens: group 1, doxycycline monohydrate 100 mg once daily (Vibramycin; Pfizer); group 2, combined chloroquine diphosphate 161.21 mg (equivalent to chloroquine 100 mg base) and proguanil hydrochloride 200 mg once daily (Savarine; Zeneca); group 3, mefloquine hydrochloride 274.09 mg (equivalent to 250 mg mefloquine base; Lariam; Roche) once weekly for 17 days before departure, during the stay in Africa, and for four weeks after return (placebo capsules were taken on the six days when no active drug was required); and group 4, combined atovaquone 250 mg and proguanil hydrochloride 100 mg (Malarone; GlaxoSmithKline) once daily for 17 days before departure, during the stay in Africa, and for one week after return, then placebo daily for three weeks.

Fig 1.

Study design

A placebo run-in phase for one quarter of participants in each arm was incorporated into the first week of study intake. These participants then joined one of the active treatment groups according to randomisation.

The drugs were provided as identical capsules blister packed in weekly cards. Randomisation was performed by the company that packed the study drugs (Quintiles; West Lothian, Scotland). Randomisation was from a computer generated table of numbers in permuted blocks of five. Participants were allocated treatment sequentially in order of study numbers. Allocation concealment was by sealed envelope.

Test instruments

Tolerability was assessed with three questionnaires. Participants completed these during recruitment and at follow up 13-11 days before departure, 6-4 days before departure, and 7-14 days after return.

Adverse events

Adverse events were recorded using a questionnaire similar to that used in a postal questionnaire survey of UK travellers.8 We modified the questionnaire to capture recognised, possible adverse events associated with any of the four study drugs: nausea, diarrhoea, mouth ulcers, itching, headache, strange or vivid dreams, dizziness, anxiety, depression, visual disturbance, fits or seizures, abnormal reddening of the skin, abnormal vaginal discharge or vaginal itching, and a category for “any other.” Participants were asked to grade the severity of the adverse events on a scale of 1 to 4: grade 1, trivial; grade 2, some interference with daily activities; grade 3, medical advice sought; and grade 4, hospital admission required.

Moods and feelings

Moods and feelings were captured by the profile of mood states questionnaire.9 This questionnaire detects tension, depression, anger, vigour, fatigue, and confusion. Items were scored on a 5 point scale from 0 “not at all” to 4 “extremely.” The questionnaire has been successfully used in studies on the tolerability of malaria chemoprophylaxis in tourist and military populations.10,11

Quality of life

Participants were asked to grade the 13 positive statements, such as I can enjoy my everyday life, in the quality of life questionnaire on a scale of 1 “not at all true” to 6 “true,” The higher the score, the better the perceived quality of life.

Statistical analyses

The main outcome measure was the proportion of participants in each arm with subjectively moderate or severe adverse events. The initial sample size was intended to be 383 per arm, but because recruitment was slower and more difficult than expected and there was the possibility of the drugs exceeding their expiry date, the study was closed before this sample size was achieved.

Secondary outcome measures were the scores from the profile of mood states and quality of life questionnaires. The χ2 test was used to detect differences in the rates and severity of self reported adverse events. We also grouped adverse events in each arm by type (neuropsychological, gastrointestinal, dermatological). We performed logistic regression analyses to check for any effect of sex or age on the incidence of adverse events. SPSS version 6 was used for the statistical analysis.

Analyses of variance were run on the scores for mood states obtained for each group at each follow up. The mean scores were converted to T scores to enable comparison with published normal scores for college students. To assess total mood disturbance, we summed the scores across all six moods and weighed vigour negatively. We checked differences in scores between groups with repeated measures of analysis of variance, and further analyses were checked for the effect of sex, age, and follow up time on mood.

Quality of life scores were computed for each arm for 13-11 days before departure to 7-14 days after return. The mean score was used as an index score for each arm. The score for the placebo run-in phase was based on the results at recruitment and 13-11 days before departure only.

Results

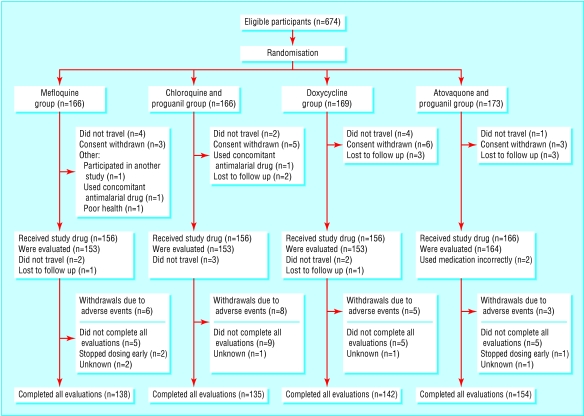

A total of 674 people (49% female) were recruited and completed the adverse events' questionnaire at baseline (fig 2). After exclusion of drop-outs (changes in travel plans, cancelled trips, decision not to take part), our sample population comprised 623 people who had reported any or no adverse event at baseline or at follow up. Overall, 153 participants were assigned to either mefloquine, doxycycline, or combined cholorquine and proguanil, and 164 were assigned to combined atovaquone and proguanil. Sex and age profiles were similar in the arms. Analysis of mood was performed on the 547 participants who completed the mood states questionnaire at baseline and follow up.

Fig 2.

Flow of participants through trial

Adverse events were analysed in 623 participants who completed questionnaires at recruitment and at least one of the follow up periods (table 1). Although a high proportion of participants reported adverse events, none were serious. At the first control time point (13-11 days before departure) some adverse event was reported by 34 (22%) participants in the mefloquine arm, 36 (24%) in the chloroquine and proguanil arm, 25 (16%) in the doxycycline arm, 25 (15%) in the atovaquone and proguanil arm, and 24 (16%) placebo users.

Table 1.

Incidence of adverse events in antimalarial prophylaxis arms according to severity. Values are numbers (percentages, 95% confidence intervals) unless stated otherwise.

| Type of adverse event | Mefloquine group* (n=153) | Chloroquine and proguanil group (n=153) | Doxycycline group (n=153) | Atovaquone and proguanil (n=164) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity of adverse event: | |||||

| Mild† | 135 (88, 83 to 93) | 131 (86, 80 to 91) | 128 (84, 78 to 90) | 134 (82, 75 to 88) | 0.42 |

| Moderate‡ | 64 (42, 34 to 50) | 69 (45, 37 to 53) | 51 (33, 26 to 41) | 53 (32, 25 to 40) | 0.048 |

| Severe§ | 16 (11, 6 to 15) | 19 (12, 7 to 18) | 9 (6, 2 to 10) | 11 (7, 2 to 11) | 0.14 |

| Withdrawals | 6 (4, 1 to 8) | 8 (5, 2 to 9) | 5 (3, 0 to 6) | 3 (2, 0 to 4) | 0.42 |

One participant had a transient ischaemic attack outside follow up; history of two episodes was not declared (mefloquine serum concentrations were negligible).

Trivial but some discomfort noted.

Interferes with daily activity.

Medical advice required.

Twenty two participants withdrew from the study owing to adverse events or because allocation concealment had had to be broken. Withdrawal was lowest in the combined atovaquone and proguanil arm (n = 3; 2% (95% confidence interval, 0% to 4%), intermediate in the doxycycline arm (n = 5; 3%, 0% to 6%) and mefloquine arm (n = 6; 4%, 1% to 8%), and highest in the combined chloroquine and proguanil arm (n = 8; 5%, 2% to 9%: P = 0.425). The grade of adverse event leading to withdrawal was mild in five participants, moderate in eight, and severe in five. No severity grades were available for three withdrawals. No statistically significant difference was found in withdrawals between the treatment arms (table 1).

Overall, 528 participants (85% of the sample population) reported at least one adverse event of any severity, and 237 (38%) reported moderate to severe adverse events (primary end point). The highest incidence was in the combined chloroquine and proguanil arm and the lowest in the combined atovaquone and proguanil arm (n = 69; 45%, 37% to 53% and n = 53; 32%, 25% to 40%, respectively). Fifty five participants (9%) reported at least one severe adverse event. The highest incidence was in the combined chloroquine and proguanil arm and the lowest in the doxycycline arm (n = 19; 12%, 7% to 18% and n = 9; 6%, 2% to 10%) (table 1).

The mefloquine arm had the highest incidence of moderate to severe neuropsychological events (n = 56; 37%, 29% to 44%: P = 0.003, table 2) and the lowest incidence of moderate to severe skin events (n = 2; 1%, 0% to 3%: P = 0.013). The combined chloroquine and proguanil arm had the highest incidence of moderate to severe skin adverse events (n = 12; 8%, 4% to 12%). Women reported significantly more neuropsychological, gastrointestinal, and skin problems than men. Men in the combined chloroquine and proguanil arm were more likely to have moderate skin problems. Women in the mefloquine arm were significantly more likely to have moderate neuropsychological problems than women in the doxycycline or combined atovaquone and proguanil.

Table 2.

Proportion of participants in each antimalarial prophylaxis arm reporting adverse events, by type and severity, Values are numbers (percentages, 95% confidence intervals) unless stated otherwise

| Type of adverse event | Mefloquine group (n=153) | Chloroquine and proguanil group (n=153) | Doxycycline group (n=153) | Atovaquone and proguanil group (n=164) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuropsychological*: | |||||

| Severe | 8 (5, 2 to 9) | 6 (4, 1 to 7) | 1 (1, 0 to 2) | 5 (3, 0 to 6) | 0.139 |

| Moderate | 56 (37, 29 to 44) | 46 (30, 23 to 37) | 36 (24, 17 to 30) | 32 (20, 13 to 26) | 0.003 |

| All events | 118 (77, 70 to 84) | 107 (70, 63 to 77) | 105 (69, 61 to 76) | 109 (67, 60 to 74) | 0.187 |

| Gastrointestinal† | |||||

| Severe | 6 (4, 1 to 7) | 9 (6, 2 to 10) | 3 (2, 0 to 4) | 5 (3, 0 to 6) | 0.312 |

| Moderate | 24 (16, 10 to 22) | 31 (20, 14 to 27) | 14 (9, 5 to 14) | 26 (16, 10 to 22) | 0.058 |

| All events | 89 (58, 50 to 66) | 93 (61, 53 to 69) | 81 (53, 45 to 61) | 88 (54, 46 to 61) | 0.451 |

| Skin‡ | |||||

| Severe | 1 (1, 0 to 2) | 2 (1, 0 to 3) | 3 (2, 0 to 4) | 1 (1, 0 to 2) | 0.635 |

| Moderate | 2 (1, 0 to 3) | 12 (8, 4 to 12) | 5 (3, 1 to 6) | 4 (2, 0 to 5) | 0.013 |

| All events | 36 (24, 17 to 30) | 40 (26, 19 to 33) | 36 (24, 17 to 30) | 34 (21, 15 to 27) | 0.730 |

| Skin and vaginal§ | |||||

| Severe | 2 (1, 0 to 3) | 2 (1, 0 to 3) | 4 (3, 0 to 5) | 1 (1, 0 to 2) | 0.509 |

| Moderate | 5 (3, 1 to 6) | 13 (9, 4 to 13) | 9 (6, 2 to 10) | 4 (2, 0 to 5) | 0.058 |

| All events | 45 (29, 22 to 37) | 45 (29, 22 to 37) | 42 (28, 20 to 35) | 40 (24, 18 to 31) | 0.717 |

| Other: | |||||

| Severe | 3 (2, 0 to 4) | 5 (3, 0 to 6) | 4 (3, 0 to 5) | 2 (1, 0 to 3) | 0.644 |

| Moderate | 12 (8, 4 to 12) | 16 (11, 6 to 15) | 12 (8, 4 to 12) | 12 (7, 3 to 11) | 0.748 |

| All events | 46 (30, 23 to 37) | 47 (31, 23 to 38) | 48 (31, 24 to 39) | 36 (22, 16 to 28) | 0.201 |

Symptoms include headache, strange or vivid dreams, dizziness, anxiety, depression, sleeplessness, and visual disturbance.

Nausea, diarrhoea, mouth ulcers.

Itching, abnormal reddening of skin.

Itching, abnormal discharge.

No significant differences in mood were found between the treatment arms. Scores were in the normal range, and means deviated by no more than one standard deviation. All arms showed good mean index scores for quality of life: combined atovaquone and proguanil 4.9 (4.8 to 5.1); combined cholorquine and proguanil 4.9 (4.6 to 5.0); doxycycline 4.8 (4.7 to 5.0); and mefloquine 4.8 (4.7 to 4.9: P = 0.41 for all). The mean index for the placebo group was 4.9.

Discussion

Tolerability to the four currently recommended antimalarial drugs, mefloquine, doxycycline, combined chloroquine and proguanil, and combined atovaquone and proguanil, is high, with no serious adverse events and good quality of life reported. Moods and feelings were also good, with high scores for “vigour” and low scores for “tension,” “depression,” “anger,” “fatigue,” and “confusion”—the so-called iceberg profile.

Although several factors influence the choice of antimalarial regimen, tolerability is important to encourage compliance to treatment of non-immune travellers to endemic areas. A recent evaluation of circumsporozoite seroconversion studies showed that a high proportion of travellers to West Africa, East Africa, and South Africa will be exposed to Plasmodium falciparum.12

Our study is the first to concomitantly examine the tolerability of the currently recommended antimalarial regimens in a uniform group of non-immune tourists. Over three quarters of our participants reported inter-current events. Even in the initial placebo group, where travel was a not a confounding feature, the incidence of adverse events was comparable to the active treatment groups.

Relation to other studies

More that 3000 people have been enrolled in five placebo controlled trials comparing combined atovaquone and proguanil with either combined chloroquine and proguanil, mefloquine, doxycycline, or placebo alone. Our study agreed with the favourable safety profile for atovaquone and proguanil shown in comparator studies.6,7-13 Data on long term tolerability and post marketing surveillance are now required.

Previous studies of doxycycline have been limited to predominantly male soldiers in whom the drug was well tolerated.14-21 Oesophageal ulceration associated with doxycycline prophylaxis was a common reason for admission to hospital of US troops deployed in Somalia.22 This was not a problem in our study, possibly because we used the monohydrate salt of doxycycline and because participants were instructed to take drugs with a glass of water after food and not before bedtime. Skin reactions, including photosensitivity, were expected. One third of the severe problems with doxycycline were skin reactions, although the highest proportions of all such reactions were in the combined chloroquine and proguanil arm. Our participants were advised to use sunscreens and were warned that one of the study drugs was potentially phototoxic. Regression analysis showed no increased risk of vaginal candidiasis with doxycycline. This good tolerability confirms the results of an uncontrolled, questionnaire survey of Australian travellers.23

What is already known on this topic

All antimalarial chemoprophylactic regimens are associated with mild adverse events, but serious events are rare

What this study adds

Combined chloroquine and proguanil is poorly tolerated and has a high incidence of skin adverse events

A significant proportion of women show mild to moderate neuropsychological adverse events with mefloquine

Combined atovaquone and proguanil and doxycycline are well tolerated during short term chemoprophylaxis

A recent meta-analysis evaluated the tolerability of mefloquine in 2750 non-immune adults and found that the incidence of adverse events was no greater than that of any comparator regimen.24 Tolerability studies have, however, repeatedly highlighted the problem of neuropsychological problems with mefloquine. Several studies and a review have shown that women are significantly more likely to experience adverse events with mefloquine than with comparator drugs.8,10,23,25 We found a significant excess of moderate neuropsychological problems with mefloquine compared with doxycycline and combined atovaquone and proguanil but not with combined chloroquine and proguanil. Furthermore, regression analysis between the medication and sex showed that significantly more women taking mefloquine reported mild to moderate neuropsychological problems (including headache and sleep disturbances) than those taking the other drugs. This confirms the results of earlier uncontrolled questionnaire studies.

Although studies have shown that combined chloroquine and proguanil is associated with a high incidence of adverse events, some health authorities still recommend its use.7,8,26 We found the poorest tolerability to this combination, but the drug remains an alternative treatment when other drugs are contraindicated.

Supplementary Material

The acknowledgments appear on bmj.com

The acknowledgments appear on bmj.com

Contributors: PS and RS designed the study, with statistical input from AT and RJ and were responsible for centre coordination and study management. PS, HDN, BB, ES, MH, BK, OV, and RA obtained ethical approval, recruited participants, and collated the data at their respective centres. AT managed data entry and did the data analysis. RJ analysed moods and feelings. PS drafted the paper. PS and RS will act as guarantors for the paper.

Funding: Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, and Zeneca provided the drugs free of charge. GlaxoSmith Kline and Roche provided research grants. The guarantors accept full responsibility for the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Competing interests: PS has received speakers' honorariums and travel expenses from Roche and GlaxoSmithKline. She acted as a consultant to Roche in a drug safety database evaluation. RS has received speakers' honorariums and travel expenses from GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, and Pfizer. He is also a member of the advisory board of GlaxoSmithKline for malaria prophylaxis related questions. BB has received a speaker's honorarium and travel expenses from GlaxoSmithKline. HN has received speakers' honorariums and travel expenses from GlaxoSmithKline on different occasions. He has been principal or coinvestigator in several vaccine trials sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline.

Ethical approval: Approval was obtained from the ethics committees of all five participating centres in Zurich, Basel, Munich, Frankfurt, and Tel-Aviv.

References

- 1.Muentener P, Schlagenhauf P, Steffen R. Imported malaria (1985-95): trends and perspectives. Bull WHO 1999;77: 560-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. International travel and health 2002. Geneva: WHO, 2002.

- 3.Bradley DJ, Bannister B. Guidelines for malaria prevention in travellers from the United Kingdom for 2001. Commun Dis Public Health 2001;4: 84-101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control. Malaria. In: Health information for international travel. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2001.

- 5.Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel. Canadian recommendations for the prevention and treatment of malaria among international travelers. Ottawa, Canada: Health Canada, 2001. [PubMed]

- 6.Overbosch D, Schilthuis H, Bienzle U, Behrens RH, Kain KC, Clarke PD, et al. Atovaquone-proguanil versus mefloquine for malaria prophylaxis in non-immune travelers: results from a randomized, double-blind study. Clin Infect Dis 2001;33: 1015-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hogh B, Clarke PD, Camus D, Nothdurft HD, Overbosch D, Gunther M, et al. Atovaquone-proguanil vs chloroquine-proguanil for malaria prophylaxis in non-immune travellers: a randomised, double-blind study. Lancet 2000;356: 1888-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrett PJ, Emmins PD, Clarke PD, Bradley DJ Comparison of adverse events associated with the use of mefloquine and combination of chloroquine and proguanil as anti-malarial prophylaxis: postal and telephone survey of travellers. BMJ 1996;313: 525-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF. EdITS manual for the profile of mood states. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service, 1992.

- 10.Schlagenhauf P, Steffen R, Lobel H, Johnson R, Letz R, Tschopp A, et al. Mefloquine tolerability during chemoprophylaxis, focus on adverse event assessments, stereochemistry and compliance. Trop Med Int Health 1996;1: 485-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boudreau E, Schuster B, Sanchez J, Novakowski W, Johnson R, Redmond D, et al. Tolerability of prophylactic Lariam regimens. Trop Med Parasitol 1993;44: 257-65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jelinek T, Blüml A, Löscher T, Nothdurft HD. Assessing the incidence of infection with Plasmodium falciparum among international travelers. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1998;59: 35-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shanks GD. Atovaquone/proguanil. In: Schlagenhauf P, ed. Travelers' malaria. London: Decker, 2001: 227-47.

- 14.Pang LW, Limsomwong N, Boudreau EF, Singharaj P. Doxycycline prophylaxis for falciparum malaria. Lancet 1987;1: 1161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pang LW, Limsomwong N, Singharaj P. Prophylactic treatment of vivax and falciparum malaria with low-dose doxycycline. J Infect Dis 1988;158: 1124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss WR, Oloo AJ, Johnson A, Koech D, Hoffman SL. Daily primaquine is effective for prophylaxis against falciparum malaria in Kenya: comparison with mefloquin, doxycycline, and chloroquin/proguanil. J Infect Dis 1995;171: 1569-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohrt C, Ritchie TI, Widjaja H, Shanks GD, Fitriadi J, Fryauff DJ, et al. Mefloquine compared with doxycycline for the prophylaxis of malaria in Indonesia soldiers. Ann Intern Med 1997;126: 963-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson SL, Oloo AJ, Gordon DM, Ragama OB, Aleman GM, Berman JD, et al. Successful double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled field trial of azithromycin and doxycycline as prophylaxis for malaria in western Kenya. Clin Infect Dis 1998;26: 146-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor WR, Richie TL, Fryauff DJ, Piraeima H, Ohrt C, Tang D, et al. Malaria prophylaxis using azithromycin: a double-blind, placebo controlled trial in Irian Jaya, Indonesia. Clin Infect Dis 1999;28: 74-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nasveld PE, Edstein MD, Kitcher SJ, Rieckmann KH. Comparison of the effectiveness of atovaquone/proguanil combination and doxycycline in the chemoprophylaxis of malaria in Australian defense force personnel. Proceedings of the 49th annual meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 29 Oct to 2 Nov, 2000, Houston, TX. Am J Trop Med Hyg Suppl 2000. [Abstract No 1391.]

- 21.Arthur JD, Echeverria P, Shanks GD, Karwacki J, Bodhidatta L, Brown JE, et al. A comparative study of gastrointestinal infections in United States soldiers receiving doxycycline or mefloquine for malaria prophylaxis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1990;43: 606-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallace MR, Sharp TW, Smoak B, Iriye C, Rozmajzl P, Thornton SH, et al. Malaria among United States troops in Somalia. Am J Med 1996;100: 49-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips MA, Kass RB. User acceptability patterns for mefloquine and doxycycline malaria chemoprophylaxis. J Travel Med 1996;3: 40-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Croft AM, Garner P. Mefloquine for preventing malaria in non-immune adult travellers. Cochrane Database Syst Rec 2001;1: CD00138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlagenhauf P. Mefloquine for malaria chemoprophylaxis 1992-1998: a review. J Travel Med 1999;6: 122-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersen E, Ronne T, Ronn A, Bygbjerg I, Larsen SO. Reported side effects to chloroquine, chloroquine plus proguanil, and mefloquine as chemoprophylaxis against malaria in Danish travelers. J Travel Med 2000;7: 79-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.