Abstract

An adenovirus type 5 mutant deleted for the preterminal protein (pTP) gene was constructed using cell lines that express pTP. The pTP deletion mutant virus is incapable of replicating in the absence of complementation and does not express detectable levels of viral mRNAs that are expressed only after the onset of replication. Accumulation of early-region mRNAs, including that for E1A, exhibits a lag relative to that observed from the wild-type virus. However, E1A mRNA accumulation attains a steady-state level similar to the level of expression during the early phase of infection with the wild-type virus. In 293-pTP cells (human embryonic kidney cells that express pTP in addition to high levels of adenovirus E1A and E1B proteins), the pTP deletion mutant virus replicates efficiently and yields infectious titers within 5-fold of that of the wild-type virus. The deletion of 1.2 kb of pTP-encoding sequence increases the size of foreign DNA that can be introduced into the virus and, with an absolute block to replication, makes this virus an important tool for gene therapy.

Keywords: gene expression, gene therapy, complementing cells, infectious cycle

Adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) offers a powerful tool for transduction and gene therapy. It can be grown to high titer and further concentrated and infects a broad range of vertebrate tissues. The molecular nature of the infectious cycle of Ad5 and the closely related Ad2 has been intensively studied in vitro (for review, see refs. 1–4). The genetics of Ad5 have been studied in detail and strains exist with mutations in a broad range of genes (5) that have potential application for gene therapy. The mutant strains are typically complemented for growth in cell lines that express the mutated gene. The most important of these cell lines is the 293 human embryonic kidney line that is transformed by and expresses high levels of E1A and E1B proteins of Ad5 (6). Cell lines that express E4 orf6 (7), the single-strand DNA binding protein (DBP) encoded by E2A (8–10), and preterminal protein (pTP) encoded by E2B (11) have been constructed. In addition, cell lines derived from 293 cells that express pTP (11, 12), pIX (13), or E4 orf6 (14) and an A549-derived cell line that inducibly expresses both the E1 and E2A products (14) have recently been constructed. These cell lines complement multiply-deleted virus strains that are of particular importance for use as gene therapy vectors.

While adenovirus offers great potential as a gene therapy agent, certain problems arise in its use. In particular, transduction in vivo with first generation adenovirus vectors that are replication-defective causes an inflammatory response that leads to the destruction of transduced cells (15, 16). The mechanism by which the immune response is primed is not clear, but the low level of viral replication that occurs contributes (17, 18) to the development of T- and B-cell responses (16). The immune response may be dependent on expression of either early or late region viral genes. Late region genes are expressed only after the onset of viral replication while the level of early region gene expression increases substantially with the increasing gene copy number that accompanies replication. Thus, the development of mutant vectors that are absolutely incapable of replicating may help to reduce the inflammatory response and will provide tools for studies to determine the mechanism by which inflammation is induced.

The adenovirus chromosome is a linear double-stranded DNA of approximately 36 kb. Replication is primed by a protein, the 77-kDa pTP, through covalent attachment of a dCMP residue, the first nucleotide in the genome, to Ser580. pTP is proteolytically processed in maturing virions to the 55-kDa terminal protein (TP) covalently attached to the DNA in infectious virions. Replication occurs through leading-strand synthesis only by DNA polymerase, which is also encoded by E2B. The mechanism of replication leads to the production of large amounts of single-stranded DNA and to the requirement for large amounts of DBP. While a mechanism for replication in vitro in the absence of pTP exists (19), all three viral gene products encoded by the E2 region appear to be essential for viral replication in vivo (for review, see refs. 20–23).

Replication-incompetent viruses with deletions within either the pTP (as well as VAI, VAII, L1, and L2) (24) or DBP (14, 25, 26) genes have been constructed. However, complementation of these viruses is complicated by the fact that, in the case of the pTP deletion-mutant virus, a virus wild-type for the deleted genes must be used to provide the missing functions in trans, and in the case of the DBP mutants, very large amounts of DBP are required in the viral life cycle. Since pTP appears to be required at a level of two copies per viral genome, it offers a tempting target for deletion to construct a replication-incompetent virus that can be grown to high titers in a complementing cell line.

In this study, 293 cell lines that constitutively (11) or inducibly (12) express pTP were used to construct a pTP deletion mutant virus. This virus can be grown to high titer using the 293-pTP cells but does not replicate in the absence of complementation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines.

The 293 cells, a human embryonic kidney cell line that is transformed by and expresses the E1A and E1B genes of Ad5 (6) and 293 cell lines that express Ad5 pTP (11, 12) were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% calf serum. HeLa suspension cells were grown in Joklik’s modified minimal essential medium containing 7% horse serum.

Viruses.

Viruses used were dl308 (27), which is phenotypically wild type with a partial deletion and replacement of E3 sequence and has XbaI sites at 3.8 map units (within the E1A gene) and 29.4 map units (at the 5′ border of the DNA encoding the main exon of pTP), and dl309 (27), which is identical to dl308 except that it lacks the XbaI site at 29.4 map units.

Construction of Plasmids.

A plasmid encoding the left end of the adenovirus chromosome through the XbaI site at 10,589 bp (the 5′ end of the region encoding the main exon of pTP; coordinates are indicated numbering from the E1A end of the viral chromosome) was constructed by modifying the plasmid pXC15 [constructed by J. Logan (Nextran, Princeton, NJ)and G. Winberg (Karolinska Institute, Stockholm), and containing the first 5788 bp of the adenovirus chromosome]. The XbaI site (bp 1340) within the E1A gene was replaced with a BstBI site using an adaptor that maintains the E1A translational reading frame. The KpnI site (bp 2052) within the E1B region was mutated by insertion of oligonucleotides 5′-TTGCTGGATTTTCTGG-3′ and 5′-CCAGAAAATCCAGCAAGTAC-3′ between the KpnI (bp 2052) and BalI sites (bp 2068). The mutated base pair, which is italic in each strand, maintains the overlapping coding sequence for the 21-kDa and 55-kDa proteins. The XhoI site at 5788 bp was then changed to an XbaI site by insertion of an oligonucleotide linker. Finally, the AflII (bp 3533) to XbaI (bp 10589) fragment from dl309 DNA was inserted between the AflII and XbaI sites of the modified pXC15 to create p0-29.4X-B,ΔK. A virus containing the BstBI site in place of the XbaI site within the E1A gene was constructed by overlap recombination using dl327Bstβ-gal DNA with screening for white plaques in the presence of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-galactoside (28) and shown to be phenotypically wild type for growth and expression of early region genes (data not shown).

A green fluorescent protein cDNA (29) was introduced between the XbaI (bp 10,589) and SalI (bp 9842) sites of p0-29.4X-B,ΔK in the same translational reading frame as pTP to generate p0-29.4pTP-GFP. To create the pTP deletion mutant allele that was introduced into the viral chromosome, the BglII–-SalI fragment between bp 8915 and 9442 was deleted by partial digestion with BglII in the presence of ethidium bromide at 10 μg/ml followed by complete digestion with SalI, blunt-ending with T4 DNA polymerase in the presence of all four dNTPs, isolation of the appropriate fragment using electrophoresis in low-melting-point agarose, and ligating. The green fluorescent protein cDNA was then deleted by digestion with EcoRI (an EcoRI site was introduced with the green fluorescent protein cDNA) and XbaI, blunt-ending using T4 DNA polymerase in the presence of all four dNTPs, isolation of the large fragment using electrophoresis in low-melting-point agarose, and ligating to yield p0-29.4ΔpTP.

Construction of a pTP Deletion Mutant Virus.

Construction of the pTP deletion mutant dl308ΔpTP is outlined in Fig. 1. For restriction mapping of plaque-purified virus, viral DNAs were prepared by the method of S. Hardy (Somatix, San Francisco) by lysing cells in the presence of spermine (to precipitate unencapsidated DNA) followed by digestion with proteinase K, phenol extraction, and repeated ethanol precipitations. The viral DNAs were examined by agarose gel electrophoresis after restriction digestion. Viruses that had the pTP deletion mutant allele were grown in 293-pTP40 cells that express pTP from a modified genomic copy of the pTP gene (12). The virus stocks were plaque-titered using 293-pTP40 cells and titered for infectious DNA reaching the nucleus using HeLa cells grown in suspension (30).

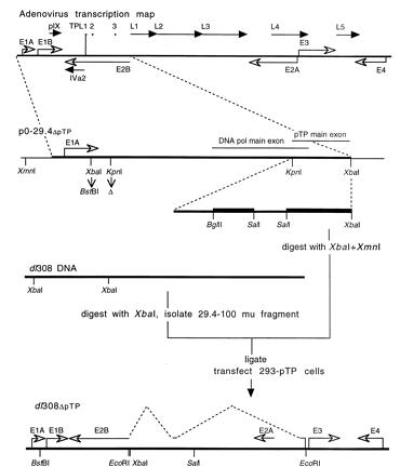

Figure 1.

Construction of the pTP deletion mutant virus. The RNA polymerase II transcription map for Ad5 is schematically presented at the top. Early region primary transcripts (except for E2B, for which only the primary coding region is presented) are indicated with open arrowheads. Late region mRNAs are presented with solid arrowheads with the primary transcripts for IVa2 and pIX indicated. The coding regions of the major late transcript are presented (L1–L5) along with the tripartite leader segments (TPL1–3) found on each of the mRNAs derived from the major late transcript. The left end of the viral chromosome through 29.4 map units (enlarged within the dashed lines) was used to make plasmid p0-29.4ΔpTP. Bacterial plasmid sequence is indicated by thin lines, the adenovirus sequence by a thicker line, and the regions of the pTP gene deleted by thickest lines in the enlargement (indicated by dashed lines) of the region encoding the main exon of pTP. The XbaI site within the E1A gene was replaced with a BstBI adaptor and the KpnI site within the E1B gene was deleted by site-specific mutation. p0-29.4ΔpTP DNA was digested with XbaI and XmnI and ligated with the 29.4–100 map unit fragment of dl308 DNA that had been digested with XbaI and purified by centrifugation twice on 10–40% sucrose gradients. The ligation mixture was used to transfect 293-pTP2 cells that stably express pTP (11) and 293-pTP14 cells that inducibly express pTP at relatively high concentration (12) using Ca3(PO4)2 precipitation. A schematic representation of dl308ΔpTP with early region transcripts including the splicing pattern for pTP (dashed lines) and sites for a limited number of restriction enzymes is presented below.

Analysis of mRNA.

Cytoplasmic RNA was isolated by lysing cells in 10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8/10 mM NaCl/3 mM MgCl2/0.5% Nonidet P-40. The cytosolic fractions were digested with proteinase K, phenol-extracted, and ethanol-precipitated three times. The pellets were resuspended in RNase-free water and concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically. RNase protection assays (31) were performed using antisense strands synthesized in the presence of [α-32P]UTP hybridized with 5 μg of cytoplasmic RNA isolated from infected cells.

Analysis of Viral Replication.

Cells harvested at various times after infection were lysed as for analysis of RNA. Nuclei were pelleted, digested with proteinase K in the presence of 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, phenol-extracted, ethanol-precipitated, digested with RNase A, and ethanol-precipitated two additional times. Appropriate dilutions of total cellular DNA were denatured and affixed to nitrocellulose using a slot blot apparatus. The amount of virus specific DNA was determined by hybridization with wild-type adenovirus DNA 32P-labeled to high specific activity (32) followed by quantitation using a PhosphorImager. For Southern blot analysis, DNA was digested with HindIII, and the fragments were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose, and hybridized with wild-type adenovirus DNA uniformly labeled with 32P (32).

RESULTS

Construction of an Adenovirus Mutant That Does Not Express pTP.

An adenovirus mutant in which approximately 700 bp encoding N-terminal and 500 bp encoding C-terminal regions of pTP were deleted was constructed and termed dl308ΔpTP (Fig. 1). The deletions introduced into the pTP coding region leave intact the sequence on the opposite strand that encodes the third segment of the tripartite leader from the major late transcript as well as the sequence overlapping the C terminus of pTP that encodes the N-terminal region of DNA polymerase. Examination of the restriction pattern ofdl308ΔpTP DNA isolated from virus grown in 293-pTP40 cells that express pTP from a modified genomic copy of the pTP gene (12) demonstrated that the deletion mutant allele of pTP was incorporated into the virus (data summarized in Fig. 1; also, see Fig. 3B).

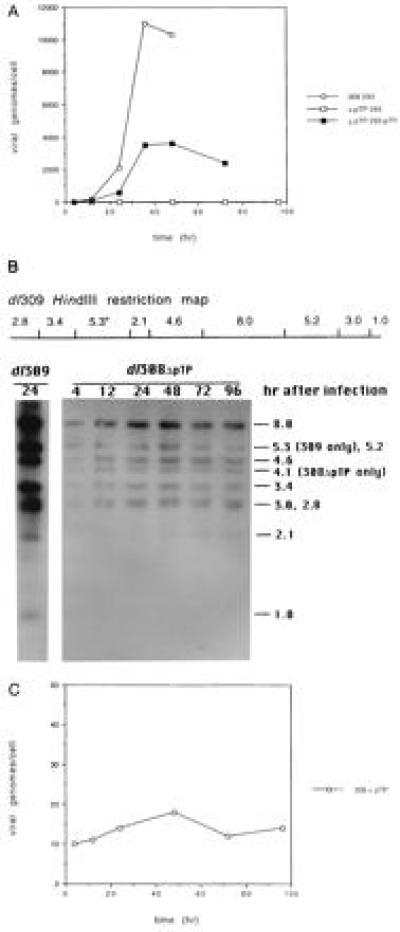

Figure 3.

Replication of wild-type and pTP deletion mutant viruses. The 293 and 293-pTP40 cells were infected with dl309 or dl308ΔpTP at a multiplicity of 10 plaque-forming units per cell. Nuclei were isolated and DNA was prepared at various times after infection. (A) Slot blot analysis of replication in 293 and 293-pTP40 cells. Dilutions of denatured DNA were bound to nitrocellulose using a slot blot apparatus. The blots were hybridized with uniformly 32P-labeled adenovirus DNA and the relative concentration of adenovirus DNA in each sample was determined by PhosphorImager analysis. (B) Southern blot analysis of dl308ΔpTP DNA in 293 cells. DNA was isolated at various times after infection as indicated above the lanes, digested with HindIII, and examined by Southern blot analysis using uniformly 32P-labeled wild-type adenovirus DNA. Above, the HindIII restriction pattern of dl309 DNA is schematically represented with an asterisk indicating the fragment encoding the main exon of pTP. The E1A end of the viral chromosome is at the left. Below, an autoradiograph of the hybridized Southern blot filter is shown. Total DNA isolated 24 hr after infection with dl309 was diluted 1:250 relative to the dl308ΔpTP samples as control. Samples of DNA isolated from cells infected with dl308ΔpTP were not diluted. The sizes of the restriction fragments are indicated in kb on the right. The 5.3-kb dl309 fragment containing the pTP gene is reduced to 4.1 kb by the 1.2-kb deletion in dl308ΔpTP. (C) PhosphorImager analysis of dl308ΔpTP replication from B. The Southern blot filter from B was analyzed by PhosphorImager. The total counts from all of the restriction fragments were determined and are plotted vs. time of infection. Similar results were obtained when the intensities of various individual fragments were determined.

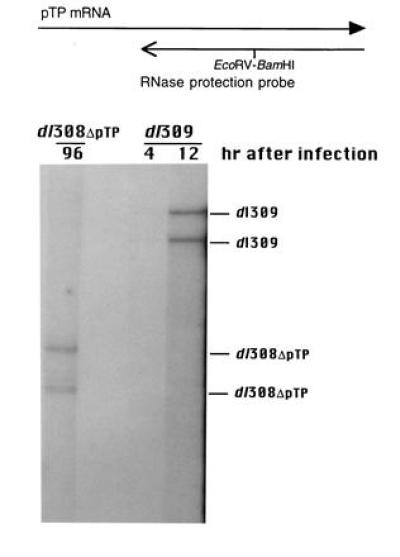

The nature of the pTP mRNA synthesized in 293 cells infected with dl308ΔpTP was examined by RNase protection. The pTP mRNA contained deletions within both the N- (data not shown) and C-terminal coding regions (Fig. 2), confirming that the virus contained the pTP deletion mutant allele. No pTP protein was detectable by Western blot analysis using polyclonal antiserum raised against a fusion protein consisting of the C-terminal two-thirds of pTP and Escherichia coli β-galactosidase purified from E. coli (11) in either HeLa or 293 cells infected with dl308ΔpTP (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Analysis of virally encoded pTP mRNA in 293 cells infected with dl308ΔpTP or dl309. Cytoplasmic RNA isolated 96 hr after infection of 293 cells with dl308ΔpTP and 4 and 12 hr after infection with dl309 was assayed by RNase protection for the presence of pTP RNA using an antisense probe overlapping the 3′ end of the pTP coding sequence from the KpnI site at bp 8533 to the SalI site at bp 9842. A BamHI linker was inserted at the EcoRV site at bp 9195 of the plasmid encoding the probe to create a discontinuity in the protected fragment. The probe and the wild-type pTP mRNA are schematically represented above, with the solid arrowhead indicating that pTP mRNA continues. An autoradiograph of the gel is presented below with the wild-type and deletion mutant protected bands indicated. The RNase protection products were compared with E1A and E1B protection bands from the same gel to determine sizes. The 5′ and 3′ products arising from mRNAs derived from the use of the splice acceptor at bp 10,589 are not expected to be well resolved for either dl309 or dl308ΔpTP. The lower band in each lane may reflect the use of an alternative splice acceptor that lies near the middle of the region encoding the main exon of pTP (41).

Yield of dl308ΔpTP.

dl308ΔpTP was grown in 293-pTP14 (pTP expressed from a cDNA; ref. 12) and 293-pTP40 (pTP expressed from a modified genomic construct; ref. 12) cells. Growth to higher titers was achieved in 293-pTP40 cells, with infectious yields of dl308ΔpTP up to approximately 5-fold lower than that of the wild-type virus. The fact that dl308ΔpTP can be grown to titers approximating that of dl309 increases the potential value of dl308ΔpTP as a transducing vector.

Replication of dl308ΔpTP.

dl308ΔpTP and the phenotypically wild-type virus dl309 were used to infect 293 and 293-pTP40 cells to compare the efficiencies of viral DNA replication. Aliquots of infected cells were collected at various times after infection and DNA was prepared from isolated nuclei. The amount of nuclear adenovirus DNA was determined by two methods. First, the DNA was applied to nitrocellulose with a slot blot apparatus and probed with uniformly 32P-labeled adenovirus DNA. The results indicated that dl308ΔpTP did not replicate (or replicated to a very low level) in the absence of complementation in 293 cells but replicated efficiently when complemented by pTP supplied in trans by 293-pTP40 cells (Fig. 3A). In contrast, dl309 replicated efficiently in both 293 (Fig. 3A) and 293-pTP40 (data not shown) cells. To confirm that dl308ΔpTP did not replicate in the absence of complementation, DNA isolated at various times after infection of 293 cells was digested with HindIII and examined by Southern blot analysis using uniformly 32P-labeled adenovirus DNA as probe (Fig. 3B). The adenovirus bands were quantitated using a PhosphorImager (Fig. 3C). Slight changes in dl308ΔpTP DNA content were apparent, but these were within the margin of error of the procedure and did not exhibit the monotonic increase that would be expected with viral replication. These data support the suggestion that dl308ΔpTP does not replicate in 293 cells.

Early Region mRNA Synthesized in Cells Infected With dl308ΔpTP.

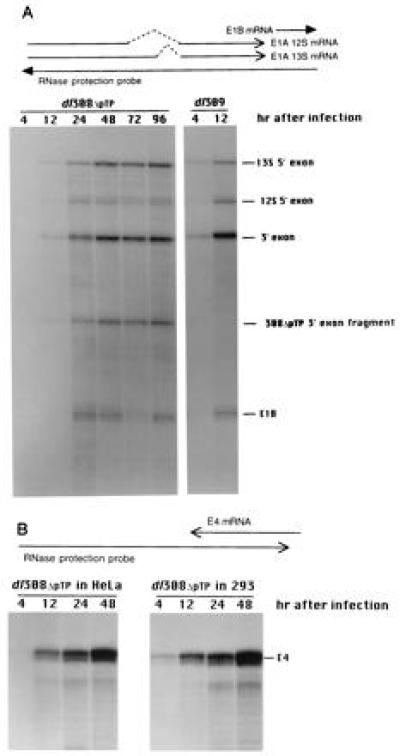

HeLa suspension cells were infected with either dl308ΔpTP or dl309. At various times after infection, RNA was isolated and the relative concentrations of E1A, E1B, and E4 mRNAs were determined by RNase protection. A significant lag before the appearance of E1A mRNA in HeLa cells infected with dl308ΔpTP was reproducibly observed relative to cells infected with dl309 (Fig. 4A). Thus, it is not surprising that there was a lag before the appearance of both E1B (Fig. 4A) and E4 (Fig. 4B and data not shown) mRNAs in HeLa cells infected with dl308ΔpTP since both genes are transcriptionally activated by E1A. At later times of infection in the absence of endogenous E1A protein, E1A and E1B mRNAs in cells infected with dl308ΔpTP reached steady-state concentrations somewhat higher than the level attained at 4 hr after infection with the wild-type virus. Since viral replication in cells infected with dl309 had not begun by 4 hr after infection while the level of early region mRNA accumulation continued to rise, the steady-state levels of E1A and E1B mRNAs in cells infected with dl308ΔpTP are similar to the maximal levels obtained during the early phase of infection by the wild-type virus. In contrast, the levels of E1A and E1B mRNAs in cells infected with dl309 rise to much higher levels during the late phase (data not shown). When E1A protein was supplied in trans by infecting 293 cells, the lag in E4 mRNA accumulation from dl308ΔpTP was reduced (Fig. 4B). In contrast to the E1A and E1B mRNAs, the concentration of E4 mRNAs continued to rise throughout the time course of infection with dl308ΔpTP.

Figure 4.

Synthesis of E1A/1B and E4 mRNAs during infection by wild-type and pTP deletion mutant viruses. (A) E1A and E1B mRNAs present within cytoplasmic RNA at various times after infection of HeLa cells with either dl309 or dl308ΔpTP as indicated above the lanes were analyzed using an antisense probe extending from the BstEII site at 1915 bp (within the E1B gene) to the left end of the chromosome. The antisense probe and the mRNAs are schematically indicated above. Introns within the E1A mRNAs are indicated by dashed lines. The solid arrowhead indicates that the E1B mRNAs continue. An autoradiograph of the gel is presented below with the protected fragments identified. The insertion of a BstBI adaptor at the XbaI site within the E1A 3′ exon of dl308ΔpTP leads to inefficient cleavage at the site of the discontinuity and results in the dl308ΔpTP-specific fragment indicated. (B) The relative amounts of E4 mRNA present within cytoplasmic RNA at various times after infection of HeLa and 293 cells with dl308ΔpTP as indicated above the lanes were analyzed by RNase protection. The antisense probe and the E4 mRNAs are represented schematically above. An autoradiograph of the gel is presented below with the E4 protected band indicated to the right.

Late Region mRNA Synthesized in Cells Infected With dl308ΔpTP.

The ability of the pTP deletion mutant virus to direct synthesis of mRNAs made only during the late phase of infection was examined using RNase protection to assay for IVa2 (Fig. 5) and L5 mRNAs (data not shown). Neither of these late-phase-specific mRNAs was detectable at any time during infection with the pTP deletion mutant virus, while each accumulated to high levels in cells infected with the wild-type virus and in 293-pTP cells infected with dl308ΔpTP (Fig. 5). These data again support the suggestion that little or no replication of dl308ΔpTP occurs in the absence of complementation by pTP supplied in trans.

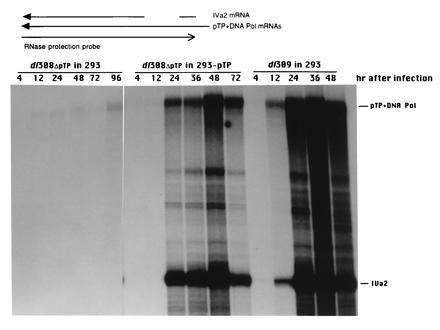

Figure 5.

Synthesis of IVa2 and pTP/Polymerase mRNAs during infection by wild-type and pTP deletion mutant viruses. RNA samples isolated from 293 or 293-pTP40 cells at various times after infection with either dl308ΔpTP or dl309 as indicated above the lanes were assayed by RNase protection for the presence of IVa2 mRNA. The antisense probe consists of the sequence between the XhoI site at bp 5788 and the BstEII site at bp 5186 and overlaps both the pTP and DNA polymerase mRNAs and IVa2 mRNA as schematically indicated above. IVa2 mRNA contains an intron, indicated by the gap, that is not removed from the E2B mRNAs. An autoradiograph of the gel is presented below with the protected species indicated. The fragment protected by the 5′ exon of IVa2 mRNA migrated to the bottom of the gel and is excluded. An overexposure of the lanes containing mRNAs from 293-pTP40 cells infected with dl308ΔpTP and 293 cells infected with dl309 is presented so that the pTP+DNA pol band present in 293 cells infected with dl308ΔpTP is apparent.

Since the IVa2 transcript is entirely contained within the 3′ region of the pTP and DNA polymerase mRNAs, the analysis of IVa2 mRNA also indicates the relative accumulation of E2B mRNAs. E2B mRNA levels increase dramatically after the onset of replication (Fig. 5, lanes containing RNA isolated from 293 cells infected with dl309 and from 293-pTP40 cells infected with dl308ΔpTP), but reach only a low level in HeLa cells infected with dl308ΔpTP, providing further evidence that replication does not occur in the absence of complementation.

Stability of the pTP Deletion Mutation in Complementing Cells.

The growth advantage of the wild-type virus relative to dl308ΔpTP raises the possibility that reversion of dl308ΔpTP to wild type could lead to rapid outgrowth of the wild-type virus. To test this possibility, the presence of wild-type virus within a dl308ΔpTP stock that had been passaged seven times in complementing cells since growth of the original plaque-purified stock was examined by assaying plaque formation in HeLa cells. At multiplicities of 20–200 plaque-forming units per cell, cytopathic effect due to binding of the virus was observed. However, at no level of virus were plaques obtained. While the presence of a large excess of replication-incompetent virus within the same cell as wild-type virus would likely inhibit growth of the wild-type virus, this evidence suggests that the concentration of wild-type virus was greater than 107-fold less than that of the deletion mutant virus and that the deletion mutation is stable in the complementing cells.

DISCUSSION

The Ad5 mutant lacking pTP expression constructed in this study offers promise for the analysis of pTP function during the adenovirus infectious cycle and as a gene therapy vector. When the pTP mutant allele deleted for 1.2 kb is placed in a background containing a large deletion within the E3 region, it will lead to a further increase in the size of foreign DNA that can be introduced into the viral chromosome. More importantly, the complete absence of replication of this virus in transduced cells should help to reduce the immune response that occurs when first-generation vectors are used.

First-generation replication-defective adenovirus vectors cause a substantial inflammatory response that leads to destruction of transduced cells. In contrast, the wild-type virus is able to form persistent infections in which infectious virus is shed for months or years after the acute infection is resolved (33, 34). The inflammation observed with the use of replication-defective transducing vectors may reflect differences in the tissues infected compared with natural infection, the infectious dose, or inhibition of immune recognition caused by expression of specific adenovirus gene products. The fact that the wild-type virus is capable of forming a persistent infection suggests that, with appropriate manipulation, adenovirus vectors should be able to transduce tissues without inducing a strong inflammatory response.

A number of the possible explanations for how adenovirus transducing vectors provoke an inflammatory response are dependent on viral replication. Expression of early and/or late region viral gene products may lead directly to immune recognition and inflammation. If so, the use of replication-incompetent vectors should help to alleviate the inflammatory response since there will be no expression of late region genes and early region gene expression will be reduced relative to that observed with replication (see Figs. 2, 4, and 5). It is also possible that the disruption of normal viral functions that results from making the vector replication-defective leads to loss of ability to inhibit immune detection. In particular, E1A plays an important role in inhibiting responses that involve interferon. E1A proteins inhibit expression of interferon-inducible host gene expression (35). E1A protein also acts indirectly to protect infected cells through activation of expression of VAI (36), which inhibits activation of the double-stranded RNA-dependent DAI kinase (for review, see ref. 37). Cells transduced with replication-defective vectors may be killed in a manner strictly dependent on interferon or the sensitivity to interferon may act to prime a specific immune response. In the absence of replication, there will be no expression of late region genes and little double-stranded RNA produced, reducing the sensitivity of transduced cells to α and β interferons even in the absence of E1A function.

Numerous additional possibilities exist for the mechanism by which an immune response is generated against adenovirus-transduced cells. For example, it is clear that E1B (38) and E3 (39, 40) proteins play an important role in protecting cells infected with the wild-type virus. In cells transduced with first generation adenovirus vectors, there should be little E3 expression in the absence of activation by E1A proteins and no E1B expression since the E1B region is deleted. Using vectors that are replication-incompetent, it will be possible to restore E1A and E1B to permit studies of the roles of the proteins encoded by these genes, as well as those encoded by E3, in inhibiting immune recognition. In addition, such viruses will aid in determination of the mechanism by which the immune response is primed by adenovirus vectors.

dl308ΔpTP also offers promise for the analysis of pTP function during the adenovirus infectious cycle. The lag observed in expression of early region genes in cells infected with dl308ΔpTP relative to cells infected with dl309 suggests that pTP, or an alternative product of the pTP gene (41), may function in transcriptional regulation beyond its role in nuclear matrix association of the viral chromosome (30). For example, the lag before high-level E1A expression is apparent in infected cells in which pTP is not synthesized could reflect a direct transcriptional activation function for pTP. However, our attempts to demonstrate such a role were unsuccessful (cited in ref. 30). Through the use of dl308ΔpTP and other viruses with more subtle mutations within the pTP gene that can now be generated using the cell lines that express pTP, it should be possible to ascertain the additional roles that pTP plays in the infectious cycle.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Smith and R. Sanderson for critical discussions and the Tissue Culture Core of the University of Colorado Cancer Center (Grant CA 46934) for preparation of tissue culture media. This work was supported by a grant from the Colorado League of Cancer and Grant GM42555 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Abbreivations: pTP, preterminal protein; Ad5, adenovirus 5; DBP, single-strand DNA binding protein.

References

- 1.Flint S J. Adv Virus Res. 1986;31:169–228. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60264-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berk A J. Annu Rev Genet. 1986;20:45–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones, N. (1995) Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 199, Pt. 3, pp. 59–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Nevins, J. R. (1995) Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 199, Pt. 3, pp. 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Shenk T, Williams J. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1984;111:1–39. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-69549-0_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham F L, Smiley J, Russell W C, Nairn R. J Gen Virol. 1977;36:59–72. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-36-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinberg D H, Ketner G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:5383–5386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.17.5383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klessig D F, Brough D E, Cleghon V. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:1354–1362. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.7.1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klessig D F, Grodzicker T, Cleghon V. Virus Res. 1984;1:69–88. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(84)90071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brough D E, Cleghon V, Klessig D F. Virology. 1992;190:624–634. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90900-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaack J, Guo X, Ho W Y-W, Karlok M, Chen C-Y, Ornelles D. J Virol. 1995;69:4079–4085. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4079-4085.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langer S, Schaack J. Virology. 1996;221:172–179. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caravokyri C, Leppard K N. J Virol. 1995;69:6627–6633. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6627-6633.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeh P, Dedieu J-F, Orsini C, Vigne E, Denefle P, Perricaudet M. J Virol. 1996;70:559–565. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.559-565.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dai Y, Schwarz E M, Gu D, Zhang W W, Sarvetnick N, Verma I M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1401–1405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y, Li Q, H C, E, Wilson J M. J Virol. 1995;69:2004–2015. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2004-2015.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engelhardt J F, Ye X, Doranz B, Wilson J M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6196–6200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engelhardt J F, Litzky L, Wilson J M. Hum Gene Ther. 1994;5:1217–1229. doi: 10.1089/hum.1994.5.10-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenny M K, Balogh L A, Hurwitz J. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:9801–9808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stillman B W. Cell. 1983;35:7–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly T J., Jr . In: The Adenoviruses. Ginsberg H S, editor. New York: Plenum; 1984. pp. 271–308. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van der Vliet, P. C. (1995) Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 199, Pt. 2, pp. 1–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Hay, R. T., Freeman, A., Leith, I., Monaghan, A. & Webster, A. (1995) Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 199, Pt. 2, pp. 31–48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Mitani K, Graham F L, Caskey C T, Kochanek S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3854–3858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rice S A, Klessig D F. J Virol. 1985;56:767–778. doi: 10.1128/jvi.56.3.767-778.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vos H L, Brough D E, Van der Lee F M, R C, H, Verheijden G F, Dooijes D, Klessig D F, Sussenbach J S. Virology. 1989;172:634–642. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90206-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones N, Shenk T. Cell. 1978;13:181–188. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaack J, Langer S, Guo X. J Virol. 1995;69:3920–3923. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3920-3923.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward W W, Prasher D C. Science. 1994;263:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schaack J, Ho W Y-W, Freimuth P, Shenk T. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1197–1208. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.7.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melton D A, Kreig P A, Rebagliate M R, Maniatis T, Zinn K, Green M R. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:7035–7056. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.18.7035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feinberg A P, Vogelstein B. Anal Biochem. 1983;132:6–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fox J P, Hall C E, Cooney M K. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;105:362–386. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mullbacher A. Immunol Cell Biol. 1992;70:59–63. doi: 10.1038/icb.1992.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reich N, Pine R, Levy D, Darnell J E., Jr J Virol. 1988;62:114–119. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.1.114-119.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoeffler W K, Roeder R G. Cell. 1985;41:955–963. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathews, M. B. (1995) Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 199, Pt. 2, 173–187. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Rao L, Debbas M, Sabbatini P, Hockenbery D, Korsmeyer S, White E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7742–7746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wold W S. J Cell Biochem. 1993;53:329–335. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240530410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ginsberg H S, Prince G A. Infect Agents Dis. 1994;3:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Broker T R, Keller C, Roberts R J. In: Genetic Maps 1984. O’Brien S J, editor. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1984. p. 99. [Google Scholar]