Abstract

Hospital surveillance was established in the Nile River Delta to increase the understanding of the epidemiology of diarrheal disease among Egyptian children. Between September 2000 and August 2003, samples obtained from children less than 5 years of age who had diarrhea and who were seeking hospital care were cultured for enteric bacteria. Colonies from each culture with a morphology typical of that of Escherichia coli were tested for the heat-labile (LT) and heat-stable (ST) toxins by a GM-1-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and colonization factor (CF) antigens by an immunodot blot assay. Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) isolates were recovered from 320/1,540 (20.7%) children, and ETEC isolates expressing a known CF were identified in 151/320 (47%) samples. ST CFA/I, ST CS6, ST CS14, and LT and ST CS5 plus CS6 represented 75% of the CFs expressed by ETEC isolates expressing a detectable CF. Year-to-year variability in the proportion of ETEC isolates that expressed a detectable CF was observed (e.g., the proportion that expressed CFA/I ranged from 10% in year 1 to 21% in year 3); however, the relative proportions of ETEC isolates expressing a CF were similar over the reporting period. The proportion of CF-positive ETEC isolates was higher among isolates that expressed ST. ETEC isolates expressing CS6 were isolated significantly less often (P < 0.001) than isolates expressing CFA/I in children less than 1 year of age. Macrorestriction profiling of CFA/I-expressing ETEC isolates by using the restriction enzyme XbaI and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis demonstrated a wide genetic diversity among the isolates that did not directly correlate with the virulence of the pathogen. The genome plasticity demonstrated in the ETEC isolates collected in this work suggests an additional challenge to the development of a globally effective vaccine for ETEC.

Diarrheal surveillance in developing countries consistently demonstrates that enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) is a significant cause of morbidity (51). ETEC disease typically manifests as an acute watery diarrhea which can elicit gastrointestinal symptoms ranging from mild to severe, with or without fever and vomiting (8, 16). The consumption of ETEC-contaminated water or food is the most probable route of infection, and a relatively high inoculum (∼108 CFU) is required (17). Although ETEC-associated diarrhea usually resolves in 1 to 3 days, the disease may be debilitating and may lead to death, particularly in young children and elderly individuals (16).

ETEC infection and the subsequent disease are primarily facilitated by two classes of virulence factors (22). ETEC adhesive fimbriae or colonization factor (CF) antigens enable bacteria to adhere to and colonize the host intestinal mucosa. The subsequent secretion of a heat-labile toxin (LT), a heat-stable toxin (ST), or both toxins (LTST) by the bacteria disrupts intestinal epithelial cell signaling pathways in the host, resulting in diarrhea.

To date, more than 20 ETEC CFs have been characterized (11, 27). The diversity of ETEC CFs is due to differences in the primary amino acid sequences of the adhesive fimbrial structural subunits. Thus, ETEC adhesin proteins have been grouped into families or as distinct fimbriae on the basis of the underlying genetic diversity (5). The CFA/I family or ETEC class 5 fimbriae consist of CFA/I, CS1, CS2, CS4, CS14 (PCFO166), CS17, CS19, and PCFO71. CS3, CS6, CS10 (2230), CS11 (PCFO148), and CS12 (PCFO159) are distinct antigens, while CS8 and CS21 (Longus) represent type IV-like fimbriae. Some CF antigens share sequence similarity with fimbriae common to animal-associated ETEC strains, such as CS5, which is similar to the F41 fimbria; CS13 (PCFO9), which is similar to K88 and CS12 fimbriae; and CS18 (PCFO20) and CS20, which are similar to the 987P fimbria (11, 47). ETEC isolates may express a single detectable CF, as is the case for CFA/I, or multiple CFs, such as that observed with CS3 (CS3 alone or in combination with CS1 or CS2) and CS6 (CS6 alone or in combination with CS4 or CS5).

In Egypt, several community-based studies have reported on the burden of ETEC infection in native children and foreign travelers (2, 34). To complement these studies, a hospital-based surveillance was initiated in September 2000 to determine the etiology of severe diarrhea in children less than 5 years of age in two referral hospitals located in the agricultural community of Abu Homos (population, 348,000) and the periurban community of Benha (455,000) in northern Egypt (53). The etiology of diarrhea during the first 2 years of this study has been reported previously, including the prevalence and the phenotype distribution of the ETEC isolates. In the study described in the current report, we compared the year-to-year variations in ETEC isolates expressing enterotoxins and the CF types over a 3- year period, beginning in September 2000, with special emphasis paid to the four most significantly expressed ETEC CFs. In addition, we examined the genomic profile of ETEC using XbaI macrorestriction profiling and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) to determine whether there was an association between specific strains and pathogenicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

Between September 2000 and August 2003, surveillance was established at the Benha Fever Hospital and Abu Homos General Hospital in the Nile Delta of Egypt (53). Due to the large number of children who come to the hospitals for evaluation of diarrhea, the study enrollment was limited to every fifth child whose primary complaint was diarrhea. After informed consent was obtained, a physical examination was performed and a detailed questionnaire that collected information on the present illness along with the patient's history of diarrheal diseases and selected demographic information was completed. Acute diarrhea was defined as a watery diarrheal episode without visible blood lasting less than 14 days, while dysentery was defined when the stool contained blood or mucus. Persistent diarrhea was defined as diarrhea whose duration was greater than 14 days (53).

Two rectal swab specimens were collected from each child. One was placed in Cary-Blair medium, and the other was placed in buffered glycerol saline transport medium. Both specimens were stored at 4°C. Stool aliquots were also collected from the children and frozen at −20°C. Specimens were transported to the Enteric Disease Research Program Laboratory of U.S. Naval Medical Research Unit No. 3 (NAMRU-3) within 3 days of collection. At NAMRU-3, the specimens were cultured for the common enteric pathogens, such as Campylobacter spp. and Shigella spp., by using standard bacteriological methods. From each culture, up to five colonies with E. coli-like morphologies were picked from MacConkey agar plates. Individual isolates were preserved in Trypticase soy broth containing 15% glycerol and were stored at −70°C until they were tested. Frozen stools were tested with specific enzyme immunoassay-based commercial kits; a Rotaclone kit (Meridian Bioscience, Inc., Cincinnati, OH) and a Cryptosporidium II kit (Techlab, Blacksburg, VA) was used for the detection of rotavirus and Cryptosporidium antigens (1), respectively (53).

Detection of ETEC and E. coli surface antigens.

Bacterial colonies were tested for LT and ST production by using a GM-1-based indirect enzyme linked-immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and an inhibition ELISA, respectively (40, 44). An isolate was defined as ETEC if it expressed LT or ST, or both toxins. Only isolates confirmed to be ETEC by ELISA were further tested for the expression of CFA/I, CS1 to CS8, CS12, CS14, and CS17 by an immunodot blot assay (3, 20, 49). For the purpose of data analysis, if more than one ETEC toxin phenotype or two different CF types were indentified in the specimen obtained from the same child, the case was defined as having mixed toxins (e.g., LT and LTST) or mixed CFs.

PFGE.

Macrorestriction profiling of genomic DNA was performed with the restriction endonuclease XbaI, as described previously (24). DNA was resolved by PFGE with a CHEF-DRII apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA). Briefly, the ETEC isolates were cultured overnight at 37°C on MacConkey agar and were suspended in 75 mM NaCl-25 mM EDTA buffer (pH 7.4) to attain an optical density of 1.8 at 610 nm. Bacterial cells were suspended in 1.6% Seakem Gold agarose (Cambrex BioScience, Rockland, ME); and the cells were lysed in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM EDTA, and 1% N-lauryl sarcosine buffer containing 0.5 mg/ml proteinase K for 48 h at 55°C. After the bacterial DNA was repeatedly washed in TE (Tris-EDTA) buffer, it was digested with XbaI (20 U) overnight at 37°C. Restricted fragments of genomic DNA were then separated for 22 h at 14°C and 6 V/cm, with initial and final linear pulses of 1.8 and 18.7 s, respectively. The DNA patterns were captured with a digital camera, after they were stained with ethidium bromide and visualized with UV light. Cluster analysis was performed with Bionumerics software (version 4; Applied Mathematics, Austin, TX) with a band optimization setting of 0% and a band tolerance setting of 1.2. Dendrograms based on the similarities of enzyme-digested genomic DNA obtained from the ETEC isolates studied were generated by using the complete linkage method, and the genetic distance was computed by using the Dice method (45).

Data analysis.

Data analysis was performed by use of the chi-square test or Fisher's exact probability test, as appropriate.

RESULTS

Between September 2000 and August 2003, 1,540 children between birth and 5 years of age were enrolled in the study. Different pathogens were observed in this study; however, our focus was on ETEC. Of the children in the study, 320 were culture positive for ETEC (20.7%). The frequency of ETEC infection and the associated virulence traits were compared between the two study sites, and no significant differences were found (data not shown). As a result, the data were combined and the children from the two sites were considered one cohort.

Phenotypic distribution of ETEC virulence factors.

In total, 298/320 (93.1%) ETEC isolates obtained from cases with diarrhea produced LT only (42%; n = 134), ST only (39%; n = 125), or LTST (12%; n = 39) (Table 1). For the remaining cases (7%; n = 22), a mixture of ETEC isolates expressing different toxin phenotypes was detected, such as one ETEC isolate producing LT and another producing ST.

TABLE 1.

Phenotypic distribution of ETEC toxins and E. coli surface antigens from September 2000 to August 2003

| CF type identified | No. (%) of ETEC isolates associated with the following toxin type:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LT (n = 134) | LTST (n = 39) | ST (n = 125) | Mixed (n = 22) | All ETEC (n = 320) | |

| CFA/I | 2 (5.1) | 44 (35.2) | 4 (18.2) | 50 (15.6) | |

| CS1 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) | |||

| CS1 + CS3 | 1 (0.8) | 1 (4.5) | 2 (0.6) | ||

| CS2 + CS3 | 1 (0.8) | 1 (4.5) | 2 (0.6) | ||

| CS3 | 1 (4.5) | 1 (0.3) | |||

| CS4 + CS6 | 4 (18.2) | 4 (1.3) | |||

| CS5 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (2.6) | 3 (2.4) | 5 (1.6) | |

| CS5 + CS6 | 15 (38.5) | 4 (3.2) | 2 (9.1) | 21 (6.6) | |

| CS6 | 1 (0.7) | 21 (16.8) | 22 (6.9) | ||

| CS7 | 7 (5.2) | 1 (4.5) | 8 (2.5) | ||

| CS8 | 2 (1.5) | 2 (0.6) | |||

| CS12 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (0.9) | |

| CS14 | 8 (20.5) | 10 (8.0) | 2 (9.1) | 20 (6.3) | |

| CS17 | 4 (3.0) | 4 (1.3) | |||

| Mixed CFa | 3 (7.7) | 3 (2.4) | 6 (1.9) | ||

| CF undetectedb | 117 (87.3) | 9 (23.1) | 37 (29.6) | 6 (27.3) | 169 (52.8) |

Children with mixed ETEC infections shed two different ETEC isolates, each of which expressed one CF antigen; these were LTST CS3 and CS5 plus CS6, LTST CFA/I and CS5 plus CS6, LTST CFA/I and CS7, ST CS2 plus CS3 and CS6, ST CS6 and CS17, and ST CS3 and CS6.

CF was undetected with a panel of 12 monoclonal antibodies to CFA/I, CS1 to CS8, CS12, CS14, and CS17.

The proportions of ETEC isolates expressing ST and LT in children with diarrhea seeking hospital care were similar over the 3-year period of the study, and the year-to-year variations were not significant (Table 1; data not shown). The numbers of cases of ETEC-associated diarrhea detected during years 1, 2, and 3 of the study were 120, 99, and 101, respectively. ETEC isolates expressing LT were isolated from similar proportions of cases during the first 2 years of the study (year 1, 43.3% [n = 52]; year 2, 50.5% [n = 50]) but from a lower proportion of cases in year 3 (31.7%; n = 32). Similarly, ETEC isolates expressing ST were isolated from comparable proportions of ETEC diarrhea episodes during years 1 (41.7%; n = 50) and 3 (50.5%; n = 51) but from a lower proportion during the second year of the study (24.2%; n = 24). ETEC isolates expressing both LT and ST were recovered at the lowest frequency throughout the study; the highest proportions of such cases were found in years 2 and 3 (17.2% [n = 17] and 12.9% [n = 13], respectively). Children with multiple ETEC infections (as determined by a mixed toxin phenotype) were recovered more frequently in years 1 and 2 (8.1% [n = 9] and 7.5% [n = 8], respectively) than in year 3 (5.0% [n = 5]).

To discern the diversity of the ETEC CFs obtained in this study, we next examined the expression of 12 CFs for which immunological reagents are available. Overall, 47% (151/320) of the ETEC isolates expressed a detectable CF, as determined with monoclonal antibodies against CFA/I, CS1 to CS8, CS12, CS14, and CS17. The most commonly expressed CF types were CFA/I (15.6%), CS6 (6.9%), CS5 plus CS6 (6.6%), CS14 (6.3%), CS7 (2.5%), and CS17 and CS4 plus CS6 (both 1.3%). We did detect ETEC isolates expressing CS1, CS1 plus CS3, CS2 plus CS3, CS3, CS5, CS8, and CS12; however, all of these isolates were detected in less than 1% of the total ETEC cases (Table 1). In six children, multiple ETEC isolates expressing different CFs were identified; two ETEC isolates produced either ST or LTST and expressing dissimilar CFs (Table 1). Three CF types (CFA/I, CS6 [with or without CS5], and CS14) constituted nearly 75% of all CFs expressed by ETEC isolates expressing an identifiable CF.

The majority of CFs expressed by ETEC isolates expressing a CF were ST associated (Table 1); however, over 70% of the ETEC isolates that expressed an ST or LTST expressed a detectable CF. In contrast, the LTs expressed by the ETEC isolates were uncommonly associated with the CFs for which the isolates were evaluated in this study (13%). Year-to-year variations in the recovery of ETEC isolates expressing detectable CFs were noted, but these variations did not reach statistical significance. ETEC isolates expressing CFA/I were the most commonly recovered ETEC isolates and were identified most frequently in years 1 and 3 (15.8% [n = 19] and 20.8% [n = 21], respectively), with a low frequency of detection in year 2 (10.1%; n = 10). The proportion of ETEC isolates expressing CS6 alone or in addition to CS5 increased from 10.0% in year 1 (n = 12) to 18.2% in year 3 (n = 18), although this difference was not statistically significant, while the proportions of ETEC isolates expressing CS14 and CS17 were similar during the 3 years of the study (data not shown). Conversely, some CFs were observed only at specific times in the study; for example, CS1 plus CS3, CS4 plus CS6, and CS7 were identified in years 1 and 2 of the study and CS12 was identified in years 2 and 3, whereas CS2 plus CS3, CS3, and CS8 were recovered only in year 1.

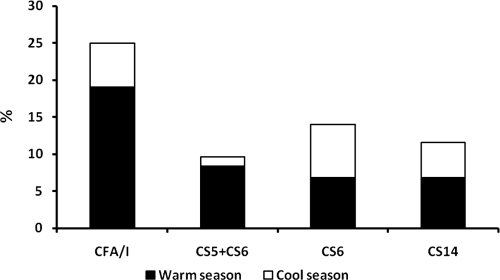

ETEC isolates expressing a detectable CF were mainly recovered from patients in the summer season. However, we observed an appreciable number of ETEC isolates expressing a CF during the cooler months of the year. The proportion of diarrhea episodes associated with the excretion of ETEC showed seasonal variations, with a nadir in February (10.7%) and a peak in June (30.6%). With the exception of ETEC isolates expressing CS6 only or CS14, ETEC isolates expressing a CF were more commonly observed during the warmer months (May to October) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Seasonal association of ETEC CF expression (September 2000 to August 2003).

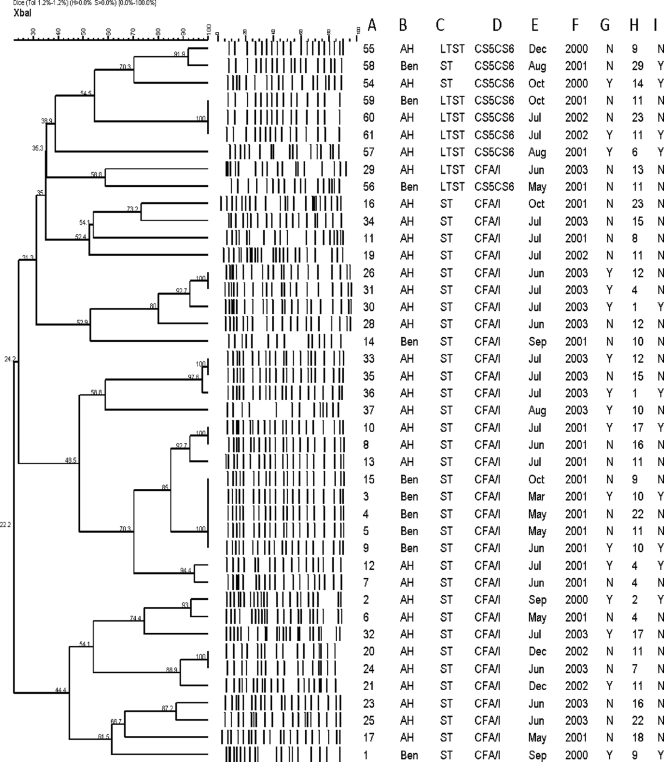

Macrorestriction digestion of ETEC isolates expressing a CF reveals extensive strain diversity.

We looked at the underlying genetic diversity of the most common ETEC phenotype (ST CFA/I) and compared the XbaI macrorestriction patterns (XbaI-mrps) or genomic fingerprints to those of an unrelated ETEC phenotype (LTST or ST expressing CS5 plus CS6). XbaI macrorestriction analysis of each of 42 ETEC isolates (isolates expressing CFA/I [n = 34] and CS5 plus CS6 [n = 8]) that was identified as the sole identifiable pathogen obtained from cases with diarrhea and recovered during different months resulted in genomic patterns consisting of 13 to 22 bands (Fig. 2). At a 52% nucleotide similarity level, nine clusters of strains were apparent. ETEC isolates expressing CS5 plus CS6 formed three distinct clusters, and the remaining six clusters contained all of the CFA/I-expressing isolates. While the eight ETEC isolates expressing CS5 plus CS6 were more similar to one another than to those expressing CFA/I, only a single branch in a single cluster consisted of indistinguishable isolates. These three strains (Ben59, AH60, and AH61) all expressed LT and ST and were found in both communities under study. An additional pair of isolates (AH55 and Ben58) from Benha and Abu Homos also had similar XbaI-mrps, despite different isolation dates and toxin profiles (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram of the XbaI mrps representing the relatedness among ETEC isolates expressing CFA/I and those expressing CS5 plus CS6 with temporal parameters, age, and clinical data. The dendrogram was generated by using the complete linkage method in order to facilitate comparisons. Columns: A, serial number; B, location (Abu Homos [AH] and Benha [Ben]; C, toxin expressed (ST and LT); D, ETEC CF expression; E, month; F, year; G, dehydration (Y, yes; N, no); H, age (in months), I, child hospitalized (Y, yes; N, no).

The strains from the six remaining clusters were exclusively composed of ETEC isolates expressing ST CFA/I and were more similar to each other than to the cluster expressing CS5 and CS6. Within the six CFA/I-expressing clusters, there were 25 distinctive XbaI-mrps. Five patterns consisted of two or more indistinguishable isolates (n = 16), and the remaining ETEC-expressing CFA/I pattern had unique banding patterns. Three of the six CFA/I-expressing clusters contained isolates from both locations. The largest cluster consisted of 10 ETEC isolates, all of which were collected in 2001. This cluster had five XbaI-mrps, two of which contained multiple indistinguishable CFA/I-expressing ETEC isolates. While there were ETEC isolates from both Abu Homos and Benha in the cluster, the Benha strains were distinguishable from the Abu Homos ones. No single XbaI-mrp for the CFA/I strains persisted throughout the entire study, but within several clusters, similar patterns were observed from year to year.

To identify whether ETEC isolates with certain XbaI-mrps were associated with disease severity, we related the age, hospitalization status, dehydration status, rectal temperature, and the maximum number of stools to the ETEC isolates within the identified XbaI-mrp clusters. For some strains, we found that the PFGE pattern reflected disease status (Fig. 2; compare the following four groups: isolates AH11, AH16, AH19, and AH34; AH26 and AH31; AH20 and AH24; and AH23 and AH25). However, this was not always the case (Fig. 2; compare the following groups: AH8 and AH10; AH33 and AH35; Ben3, Ben4, Ben5, Ben9, and Ben15; and Ben59, AH60, and AH61). Overall, no apparent association between the severity of disease and the isolates within a certain genetic cluster was observed.

Age and clinical data associated with ETEC isolates expressing CFA/I, CS5 plus CS6, CS6, and CS14.

The demographic and clinical data for children with ETEC-associated diarrhea were grouped according to the CF that the isolate expressed (Tables 2 and 3, respectively). Overall, ETEC isolates expressing a CF were more commonly recovered from children under 12 months of age. However, CS6-expressing isolates were more frequently identified in the stools of children 1 to 2 years of age (P < 0.001). In the analyses of the clinical data and CF types, we excluded ETEC cases associated with other bacterial, parasitic (such as Cryptosporidium sp.), or rotavirus infections (n = 109) to avoid the analysis of data for children with overlapping symptoms due to the presence of two enteric pathogens (data not shown). The lower percentage of hospitalization among children infected with ETEC isolates expressing CS6 was not significant compared to the percentage of children infected with ETEC isolates expressing other CF types. Among the children infected with ETEC isolates expressing CFA/I, the percentage with dehydration (40%) noted was not significant compared to the percentage noted among children infected with ETEC isolates expressing other CF types. Visible mucus in the stool was least commonly reported for children infected with ETEC isolates expressing CFA/I or CS5 plus CS6 and was most commonly reported for children infected with ETEC isolates expressing CS6 and CS14 (Table 3). The rate of reporting of visible mucus in the stool did not change when the analysis was restricted to cases without copathogens.

TABLE 2.

Age of cases infected with ETEC isolates expressing CFA/I, CS5plus CS6, CS6, and CS14

| CF type | No. (%) of children stratified by the following ages:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 year (n = 147) | 1 < 2 yr (n = 134) | >2 yr (n = 39) | 0-5 yr (n = 320) | |

| CFA/I | 30 (20.4) | 19 (14.2) | 1 (2.6) | 50 (15.6) |

| CS5 + CS6 | 11 (7.5) | 4 (3.0) | 6 (15.4) | 21 (6.6) |

| CS6 | 3 (2.0)a | 14 (10.4) | 5 (12.8) | 22 (6.9) |

| CS14 | 11 (7.5) | 8 (6.0) | 1 (2.6) | 20 (6.3) |

| Othersb | 18 (12.2) | 16 (11.9) | 4 (10.3) | 38 (11.9) |

| CF undetectedc | 74 (50.3) | 73 (54.5) | 22 (56.4) | 169 (52.8) |

In children less than 1 year of age, ETEC CS6 was recovered significantly less often than CFA/I (P = 0.0001), CS5 plus CS6 (P = 0.03), other CF types (P = 0.007), and CF undetected (0.0001).

Others include CS1, CS1 plus CS3, CS2 plus CS3, CS3, CS4 plus CS6, CS5, CS7, CS8, CS12, and CS17.

CF was undetected with a panel of 12 monoclonal antibodies to CFA/I, CS1 to CS8, CS12, CS14, and CS17.

TABLE 3.

Clinical data reported for cases in which ETEC was identified as the sole pathogen and expressed CFA/I, CS5 plus CS6, CS6, and CS14

| Clinical data | No. (%) of cases by CF type

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFA/I (n = 38) | CS5 + CS6 (n = 16) | CS6 (n = 17) | CS14 (n = 15) | Othersa (n = 25) | CF negativeb (n = 110) | All ETEC (n = 221) | |

| Hospitalization | 7 (18) | 4 (25) | 1 (06) | 2 (13) | 5 (20) | 15 (14) | 34 (15) |

| Dehydration | 15 (40) | 4 (25) | 3 (18) | 4 (27) | 9 (36) | 26 (24) | 61 (28) |

| Vomiting | 29 (76) | 12 (75) | 10 (59) | 9 (60) | 16 (64) | 74 (67) | 150 (68) |

| Temp >38°C (rectal) | 7 (18) | 5 (31) | 5 (29) | 2 (13) | 3 (12) | 18 (16) | 40 (18) |

| Temp (reported) prior to hospital help | 37 (97) | 14 (87) | 16 (94) | 14 (93) | 20 (80) | 94 (85) | 195 (88) |

| Mucus in stool | 20 (53) | 7 (44) | 15 (88)c | 13 (87)d | 13 (52) | 73 (66) | 141 (64) |

| Mean no. with liquid stools per 24 h | 7.4 ± 3.7 | 5.6 ± 2.7 | 6.1 ± 3.7 | 6.7 ± 3.3 | 7.0 ± 3.4 | 5.6 ± 3.2 | 6.2 ± 3.5 |

Others include CS1, CS1 plus CS3, CS2 plus CS3, CS3, CS4 plus CS6, CS5, CS7, CS8, CS12, and CS17.

CF was undetected with a panel of 12 monoclonal antibodies to CFA/I, CS1 to CS8, CS12, CS14, and CS17.

P = 0.011 (CFA/I) and P = 0.003 (CS5 plus CS6).

P = 0.021 (CFA/I) and P = 0.013 (CS5 plus CS6).

DISCUSSION

Prior to the implementation of immunoprophylaxis measures for the control of ETEC diarrhea, studies are needed to assess variations in the phenotypic, genotypic, and pathogenic properties of the bacterium. In this study, we describe the distribution of ETEC toxins and the associated CF types isolated from children with moderate to severe diarrhea seeking hospital care at two hospitals in the Nile Delta of Egypt over a 3-year period. The CF types expressed by the majority of ETEC isolates expressing a known and detectable CF antigen were restricted to four types, notably, CFA/I, CS6, CS5 plus CS6, and CS14. The majority (55%) of CF types detected were within the class 5 family of fimbriae (CFA/I, CS1, CS2, CS4, CS14, and CS17) (5), and 46% of these were either CFA/I or CS14. It is notable that CS14 has been increasing in frequency in this region as well as elsewhere (25, 26, 37). Our findings support the importance of ETEC isolates expressing the genetically related subclass 5a fimbriae (5) in human disease. In this study, we also noted a significant decrease in the frequency of isolation of ETEC strains expressing CS6 compared with the frequency of isolation of ETEC strains expressing other CF types from infants during their first year of life, an observation not previously reported. Similarly, we also note that the detection of CFA/I-expressing ETEC isolates appeared to be associated with the age of the child. Finally, in this study we have shown that strains of ETEC expressing either CFA/I or CS5 and CS6 are genetically diverse and that organisms with the same XbaI-mrp may have different virulence potentials. This result further demonstrates the genetic heterogeneity within ETEC isolates expressing the same CF, as described elsewhere (24).

The rates of recovery of ETEC and the identities of the CFs reported in this study are similar to those from longitudinal community-based epidemiological studies of ETEC in northern Egypt (infection rates, 15% to 20%) and hospital-based studies in other disparate locales, such as Indonesia, published previously (26, 37, 42, 55). However, we have observed differences in the CFs found to be expressed in the community-based study of pediatric diarrhea and the CFs found to be expressed in a hospital-based study conducted in the same locale. In the community-based study, the most common CFs observed, which constituted at least 2% of the detectable CFs, were CFA/I, CS6 only, CS1 and CS3, and CS14. ETEC isolates expressing CFA/I or CS5 plus CS6 were more commonly identified in the hospital-based study (15.6% and 9.7%, respectively) than in the community-based study (6.6% and 1.5%, respectively). The rates of identification of ETEC isolates expressing CS6 and CS14 were more or less similar in both studies (6.9% and 8.6%, respectively, in the hospital-based study and 6.3% and 5.8%, respectively, in the community-based study). CS1 and CS3 were seldom detected in this study (rates of detection, 0.6% and 4.0%, respectively). Our data suggest that ETEC isolates expressing CS6 were more likely to be recovered from children between 1 and 2 years of age and were recovered significantly less than ETEC isolates expressing CFA/I in children less than 1 year of age. Other ETEC CF types, such as CS8, CS12, CS17, and, in particular, CS3 (with or without the coexpression of CS1 and/or CS2), were infrequently identified in this study (less than 2%). A similar observation has previously been made in Argentina (50), but this observation differs from the results reported in studies from Bangladesh and Egypt (Abu Homos), where these CF components were identified at a higher percentage (23, 30). The incidence of infection due to ETEC isolates expressing CS6 or CS14 is increasing (25, 30, 37, 41). The highest rate of recovery of ETEC isolates expressing a detectable CF was during the warmer months, corroborating previous observations (31, 32). It should be noted, however, that the recovery of ETEC isolates expressing CS6 (39, 54) or CS14 did not appear to vary by season.

ETEC isolates without detectable CF expression, as determined with the currently available immunological reagents, have been recovered from diarrheal cases in different geographical areas (36, 37, 41). In those studies, approximately 50% of the ETEC isolates identified lacked detectable CF expression, as judged by dot blot analysis or DNA hybridization assays (32, 37, 41). We therefore expected that a large proportion of the ETEC isolates recovered in this study would also lack a detectable CF antigen. The highest percentage of ETEC isolates for which a CF was not detectable expressed LT; these results are similar to those obtained in a study that used genotypic detection methods (14, 37). The lack of an identifiable CF may be due to the loss of the plasmid harboring the CF genetic element, genetic regulation of the CF genes or a mutation within the genetic locus, or expression of a CF not covered by our testing panel (8, 35, 55, 56) or may be because the correct types of immunological reagents are not available. We are currently examining ETEC isolates with nondetectable CF expression in an attempt to better understand whether these ETEC isolates may possess a previously undetectable CF.

In this study, we made the assumption that children with severe gastroenteritis would be taken to hospital outpatient clinics more regularly than children with mild or moderate forms of the disease. To discern differences, if any, in the age or diarrhea markers associated with ETEC isolates expressing one of the four major CF antigens found in this study, we related the corresponding patients' demographic and clinical data according to the ETEC CF isolated. Although ETEC infection can cause profuse watery diarrhea with little or no fever or vomiting, previous reports of ETEC isolates recovered from hospitalized infants found the infection to be commonly associated with fever and vomiting (52). In this study, almost 30% of the children with ETEC infection suffered from dehydration (by use of the current WHO definition [10, 12, 38, 46]). In addition, vomiting (65%) and fever (88%) were reported in children shedding ETEC strains even after the exclusion of ETEC disease cases in which more than one pathogen (e.g., rotavirus, Campylobacter spp., or Cryptosporidium spp.) was identified. The observation of severe diarrhea markers (e.g., dehydration, the number of stools per day, and the volume of stool) in some study children may be attributed to the presence of strains that are more virulent because of the presence of additional virulence attributes (4). On the other hand, the elaboration of severe diarrhea symptoms may also be the result of an immunologically naive child's first encounter with an ETEC pathogen.

E. coli pathovars are diverse microorganisms composed of several clones, the genetic background of each of which encodes distinct combinations of virulence determinants. Accordingly, use of the conventional classification of E. coli by O- and H-antigen serotyping may restrict our appreciation of the genetic relationship of different diarrheagenic E. coli pathotypes (7, 24, 26, 27). Phenotypic and genotypic heterogeneity has been demonstrated among ETEC isolates of similar serogroups, such as O153 and O20 (21, 43). The data obtained in this study further support the heterogeneous nature of the ETEC genetic background. Although a limited number of isolates were studied, ETEC isolates expressing CS5 plus CS6 appear to be genetically distinct from ETEC isolates expressing CFA/I. In this study, six groups CFA/I-expressing ETEC isolates were formed. Three of these groups contained isolates from both hospitals, and three groups were unique to Abu Homos, suggesting a greater diversity among the ETEC isolates expressing CFA/I in this setting. However, since there were a greater number of isolates from Abu Homos than Benha (Benha, n = 7; Abu Homos, n = 27), this grouping may be biased. For four of the six CFA/I-expressing groups, ETEC isolates were recovered in each year of the study, although only one pair of isolates (isolates AH20 and AH24) had indistinguishable XbaI-mrps. The most likely explanation for these data is that there is a high degree of turnover of ETEC strains in the human environment. Interestingly, analysis of the ETEC isolates from Benha that had a particular XbaI-mrp (n = 5) and that were recovered from March to June of 2001 suggests that at least some strains may persist in the environment for longer periods of time. Genetic methods, such as multilocus sequence typing (18, 19) and multilocus variable-nucleotide tandem-repeat analysis (15, 48), that will permit the greater resolution of the differences between isolates will need to be used in future analyses of CFA/I-expressing ETEC strains. For example, while the isolates in the Benha cluster appeared to be indistinguishable, there were apparent differences in the pathogenicities associated with the isolates. In this study, the isolates within three of the five indistinguishable strain patterns found within the CFA/I-expressing ETEC isolates (and the only such pattern in the CS5-plus-CS6-expressing isolates) caused disease of different severities. The majority of ETEC XbaI-mrp subtypes in this study did not share a high degree of similarity, as has been observed for other E. coli pathotypes (6). The adaptive ability of E. coli pathogens (30) within the host gastrointestinal tract or outside in the environment should be studied more to obtain additional cues that might influence the diversity of virulence of the ETEC isolates.

An age-dependent isolation rate has previously been observed for ETEC isolates expressing LT CS7 and LT CS17, suggesting a naturally acquired immunity in older children (33). Establishing that CFA/I-expressing isolates also induce an age-dependent immunity in older children would corroborate the concept of immunoprophylaxis against ETEC infection (50). In this study, the decline in the rate of infection with ETEC isolates expressing CFA/I that was seen supports this idea and underlies the importance of ETEC vaccine development, as the risk factors for acquiring ETEC infection are present at higher levels among children up to 24 months of age (5, 29). ETEC class 5 fimbriae, in particular, CFA/I and CS14, in addition to the CS5 and CS7 antigens, were shown to elicit cross-reactive immune responses in primed children (13). It is interesting to note that of the CF-expressing ETEC isolates, 72% were of a type (CFA/I, CS1, CS2, CS3, CS4, CS5, and CS6) capable of inducing an antifimbrial immune response (9, 28).

However, the selective immune pressure on ETEC CFs from a host is unknown. In view of this statement, further study is needed to obtain a better understanding of the naturally acquired ETEC antifimbrial immune responses. In vitro experiments have demonstrated that environmental components have an impact on the expression of ETEC virulence factors (9, 14, 28). Little is known about the in vivo influence of environmental stress and the adaptability of ETEC as well as other E. coli pathovars within their milieu. Consequently, our understanding of the acquisition or deletion of virulence factors affecting ETEC survival inside the host is limited.

A limitation of this study was that rotavirus was the only viral enteric pathogen for which testing was performed. Thus, it is possible that other viral pathogens, including norovirus, enteric adenovirus, or astrovirus, could have been associated with the illnesses with which the study children presented.

In summary, ETEC organisms were primarily isolated from children younger than 24 months of age, and class 5a adhesins were observed more frequently from infants infected with ETEC, suggesting the presence of naturally acquired immunity in older children due to a previous primary infection. Changes in the ETEC-associated CF patterns, as well as increased rates of ETEC strains expressing CS6 or CS14, were noted in Egypt. While the application of XbaI-mrp-PFGE to a subset of Egyptian CFA/I- and CS5-plus-CS6-expressing ETEC isolates did not demonstrate a correlation between clinical symptoms and genotype, it did reveal extensive genotypic diversity among the circulating strains of the same CF recovered from children seeking hospital care and indicated that some isolates have the capacity to persist for a fixed time in the environment. Such data suggest that an ongoing database for the collection and cultivation of genetic and phenotypic information on ETEC organisms may be of value in determining the ecology and pathogenicity of this pathogen.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Savarino, A. Armstrong, and M. Weiner for critically reviewing the manuscript. We appreciate the technical expertise of Iman Touni and Rania Nada; statistical analysis was conducted by Manal Mostafa.

Financial support was received from the Global Emerging Infectious System (Work Unit no. 847705.82000.25GB.E0018).

Five coauthors (J.W.S., D.M.R., M.R.M., P.J.R., and R.W.F.) are military service members; the first author (H.I.S.) and other coauthors (I.A.A.M., J.D.K., T.F.W., and S.B.K.) are employees of the U.S. government. This work was prepared as part of our official duties.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private ones of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Department of the Navy, the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Government, or the Egyptian Ministry of Health and Population. This study (protocol no. NAMRU3.2000.0002) was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of NAMRU-3 and the Egyptian Ministry of Health and Population, in compliance with all federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects. Informed consents were obtained from all adult participants and from the parents or the legal guardians of minors.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 October 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdel-Messih, I. A., T. F. Wierzba, R. Abu-Elyazeed, A. F. Ibrahim, S. F. Ahmed, K. Kamal, J. Sanders, and R. Frenck. 2005. Diarrhea associated with Cryptosporidium parvum among young children of the Nile River Delta in Egypt. J. Trop. Pediatr. 51154-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abu-Elyazeed, R., T. F. Wierzba, A. S. Mourad, L. F. Peruski, B. A. Kay, M. Rao, A. M. Churilla, A. L. Bourgeois, A. K. Mortagy, S. M. Kamal, S. J. Savarino, J. R. Campbell, J. R. Murphy, A. Naficy, and J. D. Clemens. 1999. Epidemiology of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli diarrhea in a pediatric cohort in a periurban area of lower Egypt. J. Infect. Dis. 179382-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahren, C. M., L. Gothefors, B. J. Stoll, M. A. Salek, and A. M. Svennerholm. 1986. Comparison of methods for detection of colonization factor antigens on enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 23586-591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alam, M., A. H. Nur, S. Ahsan, G. P. Pazhani, K. Tamura, T. Ramamurthy, D. J. Gomes, S. R. Rahman, A. Islam, F. Akhtar, S. Shinoda, H. Watanabe, S. M. Faruque, and G. B. Nair. 2006. Phenotypic and molecular characteristics of Escherichia coli isolated from aquatic environment of Bangladesh. Microbiol. Immunol. 50359-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anantha, R. P., A. L. McVeigh, L. H. Lee, M. K. Agnew, F. J. Cassels, D. A. Scott, T. S. Whittam, and S. J. Savarino. 2004. Evolutionary and functional relationships of colonization factor antigen i and other class 5 adhesive fimbriae of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 727190-7201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassels, F. J., and M. K. Wolf. 1995. Colonization factors of diarrheagenic E. coli and their intestinal receptors. J. Ind. Microbiol. 15214-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakraborty, S., J. S. Deokule, P. Garg, S. K. Bhattacharya, R. K. Nandy, G. B. Nair, S. Yamasaki, Y. Takeda, and T. Ramamurthy. 2001. Concomitant infection of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in an outbreak of cholera caused by Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139 in Ahmedabad, India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 393241-3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalton, C. B., E. D. Mintz, J. G. Wells, C. A. Bopp, and R. V. Tauxe. 1999. Outbreaks of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infection in American adults: a clinical and epidemiologic profile. Epidemiol. Infect. 1239-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards, R. A., and D. M. Schifferli. 1997. Differential regulation of fasA and fasH expression of Escherichia coli 987P fimbriae by environmental cues. Mol. Microbiol. 25797-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleckenstein, J. M., K. Roy, J. F. Fischer, and M. Burkitt. 2006. Identification of a two-partner secretion locus of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 742245-2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaastra, W., and A. M. Svennerholm. 1996. Colonization factors of human enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC). Trends Microbiol. 4444-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green, B. A., R. J. Neill, W. T. Ruyechan, and R. K. Holmes. 1983. Evidence that a new enterotoxin of Escherichia coli which activates adenylate cyclase in eucaryotic target cells is not plasmid mediated. Infect. Immun. 41383-390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall, E. R., T. F. Wierzba, C. Ahren, M. R. Rao, S. Bassily, W. Francis, F. Y. Girgis, M. Safwat, Y. J. Lee, A. M. Svennerholm, J. D. Clemens, and S. J. Savarino. 2001. Induction of systemic antifimbria and antitoxin antibody responses in Egyptian children and adults by an oral, killed enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli plus cholera toxin B subunit vaccine. Infect. Immun. 692853-2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halvorsen, T., H. Valvatne, H. M. Grewal, W. Gaastra, and H. Sommerfelt. 1997. Expression of colonization factor antigen I fimbriae by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli; influence of growth conditions and a recombinant positive regulatory gene. APMIS 105247-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahali, S., B. Sarkar, S. Chakraborty, R. Macaden, J. S. Deokule, M. Ballal, R. K. Nandy, S. K. Bhattacharya, Y. Takeda, and T. Ramamurthy. 2004. Molecular epidemiology of diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli associated with sporadic cases and outbreaks of diarrhoea between 2000 and 2001 in India. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 19473-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lederer, W., and P. Echeverria. 1989. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli associated diarrhea: the clinical pattern in Khmer children. Acta Leiden 58141-150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levine, M. M., E. S. Caplan, D. Waterman, R. A. Cash, R. B. Hornick, and M. J. Snyder. 1977. Diarrhea caused by Escherichia coli that produce only heat-stable enterotoxin. Infect. Immun. 1778-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindstedt, B.-A., E. Heir, E. Gjernes, T. Vardund, and G. Kapperud. 2003. DNA fingerprinting of Shiga-toxin producing Escherichia coli O157 based on multiple-locus-variable-number tandem repeats analysis (MLVA). Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 212-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindstedt, B.-A., T. Vardund, L. Aas, and G. Kapperud. 2004. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeats analysis of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium using PCR multiplexing and multicolor capillary electrophoresis. J. Microbiol. Methods 59163-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopez-Vidal, Y., and A. M. Svennerholm. 1990. Monoclonal antibodies against the different subcomponents of colonization factor antigen II of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 281906-1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maiden, M. C., J. A. Bygraves, E. Feil, G. Morelli, J. E. Russell, R. Urwin, Q. Zhang, J. Zhou, K. Zurth, D. A. Caugant, I. M. Feavers, M. Achtman, and B. G. Spratt. 1998. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 953140-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nataro, J. P., and J. B. Kaper. 1998. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11142-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oyofo, B. A., S. H. el-Etr, M. O. Wasfy, L. Peruski, B. Kay, M. Mansour, J. R. Campbell, A. M. Svennerholm, A. M. Churilla, and J. R. Murphy. 1995. Colonization factors of enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) from residents of northern Egypt. Microbiol. Res. 150429-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pacheco, A. B., L. C. Ferreira, M. G. Pichel, D. F. Almeida, N. Binsztein, and G. I. Viboud. 2001. Beyond serotypes and virulence-associated factors: detection of genetic diversity among O153:H45 CFA/I heat-stable enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 394500-4505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paniagua, M., F. Espinoza, M. Ringman, E. Reizenstein, A. M. Svennerholm, and H. Hallander. 1997. Analysis of incidence of infection with enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in a prospective cohort study of infant diarrhea in Nicaragua. J. Clin. Microbiol. 351404-1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peruski, L. F., Jr., B. A. Kay, R. A. El-Yazeed, S. H. El-Etr, A. Cravioto, T. F. Wierzba, M. Rao, N. El-Ghorab, H. Shaheen, S. B. Khalil, K. Kamal, M. O. Wasfy, A. M. Svennerholm, J. D. Clemens, and S. J. Savarino. 1999. Phenotypic diversity of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli strains from a community-based study of pediatric diarrhea in periurban Egypt. J. Clin. Microbiol. 372974-2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pichel, M., N. Binsztein, and G. Viboud. 2000. CS22, a novel human enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli adhesin, is related to CS15. Infect. Immun. 683280-3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puente, J. L., D. Bieber, S. W. Ramer, W. Murray, and G. K. Schoolnik. 1996. The bundle-forming pili of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: transcriptional regulation by environmental signals. Mol. Microbiol. 2087-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qadri, F., F. Ahmed, T. Ahmed, and A. M. Svennerholm. 2006. Homologous and cross-reactive immune responses to enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli colonization factors in Bangladeshi children. Infect. Immun. 744512-4518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qadri, F., S. K. Das, A. S. Faruque, G. J. Fuchs, M. J. Albert, R. B. Sack, and A. M. Svennerholm. 2000. Prevalence of toxin types and colonization factors in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated during a 2-year period from diarrheal patients in Bangladesh. J. Clin. Microbiol. 3827-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qadri, F., A. Saha, T. Ahmed, A. Al Tarique, Y. A. Begum, and A. M. Svennerholm. 2007. Disease burden due to enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in the first 2 years of life in an urban community in Bangladesh. Infect. Immun. 753961-3968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao, M. R., R. Abu-Elyazeed, S. J. Savarino, A. B. Naficy, T. F. Wierzba, I. Abdel-Messih, H. Shaheen, R. W. Frenck, Jr., A. M. Svennerholm, and J. D. Clemens. 2003. High disease burden of diarrhea due to enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli among rural Egyptian infants and young children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 414862-4864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rao, M. R., T. F. Wierzba, S. J. Savarino, R. Abu-Elyazeed, N. El-Ghoreb, E. R. Hall, A. Naficy, I. Abdel-Messih, R. W. Frenck, Jr., A. M. Svennerholm, and J. D. Clemens. 2005. Serologic correlates of protection against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli diarrhea. J. Infect. Dis. 191562-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rockabrand, D. M., H. I. Shaheen, S. B. Khalil, L. F. Peruski, Jr., P. J. Rozmajzl, S. J. Savarino, M. R. Monteville, R. W. Frenck, A. M. Svennerholm, S. D. Putnam, and J. W. Sanders. 2006. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli colonization factor types collected from 1997 to 2001 in US military personnel during operation Bright Star in northern Egypt. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 559-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roels, T. H., M. E. Proctor, L. C. Robinson, K. Hulbert, C. A. Bopp, and J. P. Davis. 1998. Clinical features of infections due to Escherichia coli producing heat-stable toxin during an outbreak in Wisconsin: a rarely suspected cause of diarrhea in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26898-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serichantalergs, O., W. Nirdnoy, A. Cravioto, C. LeBron, M. Wolf, A. M. Svennerholm, D. Shlim, C. W. Hoge, and P. Echeverria. 1997. Coli surface antigens associated with enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli strains isolated from persons with traveler's diarrhea in Asia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 351639-1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaheen, H. I., S. B. Khalil, M. R. Rao, R. Abu Elyazeed, T. F. Wierzba, L. F. Peruski, Jr., S. Putnam, A. Navarro, B. Z. Morsy, A. Cravioto, J. D. Clemens, A. M. Svennerholm, and S. J. Savarino. 2004. Phenotypic profiles of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli associated with early childhood diarrhea in rural Egypt. J. Clin. Microbiol. 425588-5595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sherlock, O., R. M. Vejborg, and P. Klemm. 2005. The TibA adhesin/invasin from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli is self recognizing and induces bacterial aggregation and biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 731954-1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sizemore, D. R., K. L. Roland, and U. S. Ryan. 2004. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli virulence factors and vaccine approaches. Expert Rev. Vaccines 3585-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sjoling, A., G. Wiklund, S. J. Savarino, D. I. Cohen, and A. M. Svennerholm. 2007. Comparative analyses of phenotypic and genotypic methods for detection of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli toxins and colonization factors. J. Clin. Microbiol. 453295-3301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steinsland, H., P. Valentiner-Branth, P. Aaby, K. Molbak, and H. Sommerfelt. 2004. Clonal relatedness of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli strains isolated from a cohort of young children in Guinea-Bissau. J. Clin. Microbiol. 423100-3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Subekti, D. S., M. Lesmana, P. Tjaniadi, N. Machpud, Sriwati, Sukarma, J. C. Daniel, W. K. Alexander, J. R. Campbell, A. L. Corwin, H. J. Beecham III, C. Simanjuntak, and B. A. Oyofo. 2003. Prevalence of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) in hospitalized acute diarrhea patients in Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 47399-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sullivan, C. B., M. A. Diggle, and S. C. Clarke. 2005. Multilocus sequence typing: data analysis in clinical microbiology and public health. Mol. Biotechnol. 29245-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Svennerholm, A. M., M. Wikstrom, M. Lindblad, and J. Holmgren. 1986. Monoclonal antibodies against Escherichia coli heat-stable toxin (STa) and their use in a diagnostic ST ganglioside GM1-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 24585-590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 332233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turner, S. M., A. Scott-Tucker, L. M. Cooper, and I. R. Henderson. 2006. Weapons of mass destruction: virulence factors of the global killer enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 26310-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valvatne, H., H. Sommerfelt, W. Gaastra, M. K. Bhan, and H. M. Grewal. 1996. Identification and characterization of CS20, a new putative colonization factor of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 642635-2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vaz, T. M., K. Irino, L. S. Nishimura, M. C. Cergole-Novella, and B. E. Guth. 2006. Genetic heterogeneity of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains isolated in Sao Paulo, Brazil, from 1976 through 2003, as revealed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44798-804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Viboud, G. I., N. Binsztein, and A. M. Svennerholm. 1993. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies against putative colonization factors of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and their use in an epidemiological study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31558-564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Viboud, G. I., M. J. Jouve, N. Binsztein, M. Vergara, M. Rivas, M. Quiroga, and A. M. Svennerholm. 1999. Prospective cohort study of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infections in Argentinean children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 372829-2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wenneras, C., and V. Erling. 2004. Prevalence of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli-associated diarrhoea and carrier state in the developing world. J. Health Pop. Nutr. 22370-382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.WHO. 1990. Programme for the Control of Diarrhoeal Diseases. A manual for the treatment of diarrhea—for use by physicians and other senior health workers. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 53.Wierzba, T. F., I. A. Abdel-Messih, R. Abu-Elyazeed, S. D. Putnam, K. A. Kamal, P. Rozmajzl, S. F. Ahmed, A. Fatah, K. Zabedy, H. I. Shaheen, J. Sanders, and R. Frenck. 2006. Clinic-based surveillance for bacterial- and rotavirus-associated diarrhea in Egyptian children. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 74148-153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wolf, M. K. 1997. Occurrence, distribution, and associations of O and H serogroups, colonization factor antigens, and toxins of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10569-584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolk, M., E. Ohad, R. Shafran, I. Schmid, and E. Jarjoui. 1997. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) in hospitalised Arab infants from Judea area—West Bank, Israel. Public Health 11111-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zaki, A. M., H. L. DuPont, M. A. el Alamy, R. R. Arafat, K. Amin, M. M. Awad, L. Bassiouni, I. Z. Imam, G. S. el Malih, A. el Marsafie, et al. 1986. The detection of enteropathogens in acute diarrhea in a family cohort population in rural Egypt. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 351013-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]