Abstract

A prospective series of 65 patients with surgically confirmed lung cystic hydatid disease was evaluated in terms of their radiologic characteristics, serologic response, and presence of cysts in other organs. Cysts were mostly single and located in lower lung lobes. Liver compromise was found in 34% of the patients. Despite a systematic search, no patient showed brain cysts in this series. Twelve patients had previous hydatid disease: six in the liver and eight in the lung (two had involvement of both organs in the past). Serology using bovine cyst fluid in an immunoblot assay was 85% sensitive. Serologic response was not associated with number or cyst or compromise of other organs but was clearly associated to the presence of at least one complicated cyst. Cyst status in terms of complications should be described to allow appropriate assessment of serologic evaluations.

INTRODUCTION

Cystic hydatidosis, a zoonotic disease caused by the dog tapeworm Echinoccocus granulosus, is distributed throughout world. Eggs from the adult tapeworm are shed with the feces of infected dogs and ingested by sheep or other suitable intermediate hosts. The embryos or oncospheres hatch in the small intestine, penetrate the mucosa, and migrate through blood or lymphathic vessels to the viscera. There, the oncosphere evolves to form a fluid-filled vesicle, the hydatid cyst. When hydatid cysts are ingested by the definitive host (dogs or other canids), the primitive scolices in the cyst develop to adult tapeworms in the dog intestine.1,2

Cystic hydatid disease (CHD) involves most frequently the liver (75% of cases) and lung (15% of cases).2 Liver hydatidosis is the primary location, resulting from invading oncospheres being filtered in this organ’s rich capillary network. Lung hydatidosis apparently results from larvae that passed through the liver filter and got trapped in the arterial capillaries of the lung. More rarely, the lung may be the site of secondary metastatic hydatidosis by rupture of a liver cyst.3

After a certain period of time, cysts grow gradually in size, appearing in most cases as symptoms of abdominal or thoracic pain or palpable masses. Some of these cysts are complicated either by rupture or aggregated bacterial infection, appearing as new symptoms of fever, vomiting, and others related to the infectious process.3,4 Surgery remains the treatment of choice for hydatid cysts of the lung, with needle puncture/aspiration being the preferred therapeutic method for uncomplicated liver cysts.5-9

Co-existing lung disease is found in ∼8-16% of patients with liver CHD, and vice versa, concomitant liver disease is found in 10-40% of patients with lung CHD.1,3,5,6,10 Compromise of other organs beyond the liver and lungs is uncommon. Brain compromise is claimed to be present in 2-3% of all cases; nevertheless, these estimates come from neurologically symptomatic patients in case series (thus ignoring early or pre-symptomatic brain infections). There is little or no information about the frequency of brain hydatid cysts in patients with lung or liver CHD without neurologic symptoms.11-13

Diagnosis of CHD is based on radiological methods (chest x-rays, ultrasonography, computed tomography [CT], and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]).3,14-16 Immunodiagnosis, mostly using ELISA and indirect hemagglutination (IHA) assays, plays a complementary role for diagnostic confirmation and serologic monitoring of surgical or pharmacologic treatment.17-21 In clinical practice, the use of immunodiagnosis in CHD is hindered by lack of appropriate sensitivity, particularly in pulmonary disease.22,23

This prospective series of confirmed lung CHD cases attempted to assess potential associations between clinicopathologic features and serologic findings. We also assessed systematically whether asymptomatic brain cysts could be present in neurologically asymptomatic lung CHD patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was performed in Lima, Peru, at the Hospital Nacional Hipolito Unanue and the Hospital Nacional Dos de Mayo, two government hospitals that are referral centers for treatment of lung hydatid disease. Patients were enrolled at Hospital Nacional Hipolito Unanue in three different periods of time: July to October 2003, January to December 2004, and September to November 2005. Patients at Dos de Mayo hospital were enrolled during the last period only.

We prospectively attempted to include all patients who had been admitted for surgery of lung CHD. All these patients had a presumptive diagnosis of lung hydatid disease based on a compatible image, and in some cases, supported by immunologic diagnosis. Given the intermittent nature of our visits for patient enrollment (twice a week), in some cases, patients were enrolled a few days after surgery. Patients whose post-surgical diagnosis was different from CHD were excluded. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia (FWA 00000525, Lima, Peru).

As part of their routine medical work-up, all patients had abdominal ultrasound or abdominal CT scans to rule out liver and/or spleen involvement. As part of the study, all were offered a brain CT scan, non-contrasted, to assess brain involvement. Enrolled patients had a serum enzyme-linked immuno electrotransfer blot (EITB) assay performed using bovine cyst fluid as antigen, as described by Verastegui and others.23

RESULTS

Study population

There were 69 patients admitted for surgery of lung CHD in the study wards during the enrollment periods. All of them were invited to participate, were provided information on the study, and signed a consent form. In four cases, surgery showed an etiology different from CHD. These four patients were excluded from the study. From the 65 enrolled patients with lung CHD, 1 died and 3 withdrew from the study before serology or brain CT. Thus, the population for analysis of baseline findings is 65 patients, whereas imaging/serology correlations and brain CT results were assessed in 61 patients. The group was made up of 36 males and 29 females, with a mean age of 27.56 ± 15.20 years (range, 4-68 years); 20 (30.76%) were younger than 18 years of age. Over one half of them (N = 39) came from rural villages in the central Peruvian Andes, a known endemic region.

Lung CHD—baseline characteristics

Forty patients had a single cyst, and 25 patients had multiple lesions (total, 105 cysts; mean, 1.61 ± 1.28 cysts; range, 1-10 cysts). Bilateral lung compromise was present in 14 patients (21.53%; total, 34 cysts). The locations of pulmonary cysts are shown in Table 1. Right and left lung involvement occurred in similar frequency (53.33% versus 46.66%). Most patients (46, 70.77%) had at least one complicated (infected or ruptured) cyst. Infected cysts were present in 18 patients, and ruptured cysts were found in 28 patients (Figure 1). In 13 patients, there were both complicated and non-complicated cysts.

Table 1.

Location of pulmonary cysts

| Single cyst patients (N = 40) | Multiple cyst patients (25 patients, 65 cysts) [patients (cysts)] | |

|---|---|---|

| Left | 19* | 20 (30)† |

| Upper lobe | 6 | 12 (14) |

| Lingula | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Lower lobe | 14 | 10 (14) |

| Right | 21* | 19 (35)† |

| Upper lobe | 2 | 10 (10) |

| Middle lobe | 5 | 5 (6) |

| Lower lobe | 16 | 13 (21) |

Three cysts involved more than one lobe; one involved the upper and lower lobes of the left lung, and two involved the middle and lower lobes of the right lung.

Fourteen patients, with 34 cysts, had cysts in both lungs. Also two cysts in the right lung involved more than one lobe (upper + middle and upper + lower lobes).

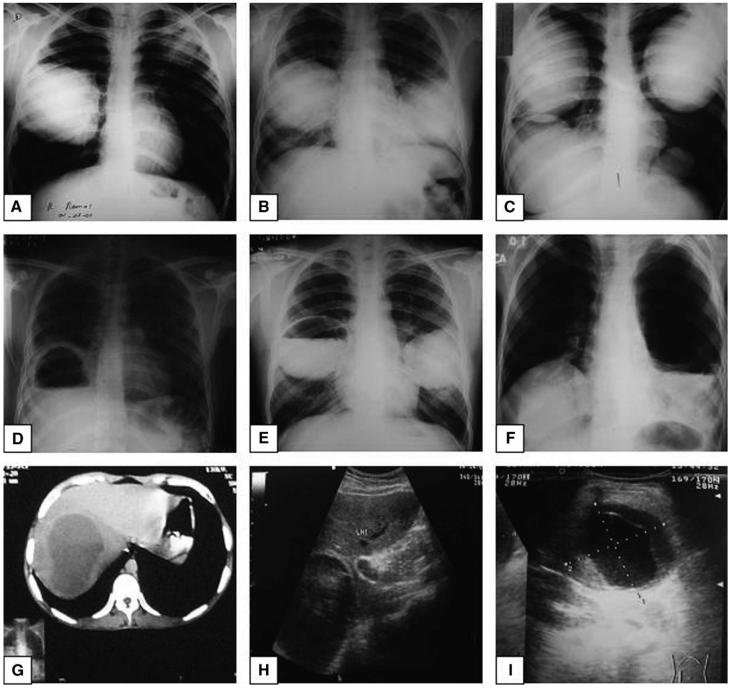

Figure 1.

Hydatid cysts. Top row, Chest x-ray images of lung hyaline or uncomplicated hydatid cysts: (A) unilateral and (B and C) bilateral. Middle row (D, E, F), Chest x-ray images of complicated (broken) lung hydatid cysts. Note the presence of air-liquid levels (arrows). Bottom row, Abdominal CT scan showing an uncomplicated liver cyst (G) and abdominal ultrasound showing uncomplicated (H) and complicated (I) liver cysts. Note the detachment of the internal membrane.

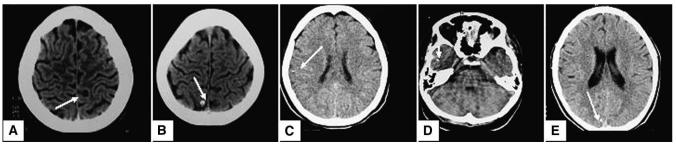

Baseline abdominal ultrasound or CT scan was performed in 53 patients (81.53%). These patients did not differ from the 12 patients without abdominal imaging evaluation in age, sex, or concomitant gastrointestinal signs or symptoms (abdominal pain, loss of appetite, vomiting, palpable masses [27/53, 50.94% versus 8/12, 66.66%]; P = 0.32). Abdominal evaluation diagnosed liver hydatid disease in 15 cases and spleen involvement in 1 case (16/53, 30.18%). The type of liver cysts according to the WHO classification was CE1 in four cases, CE2 in four cases, CE3 in five cases, CE4 in one case, and CE5 in one case. Brain CT scans were performed in all 61 patients. Abnormal CT scans were found in seven patients, none of which had CT findings suggestive of brain hydatidosis. Scans were suggestive of neurocysticercosis in five (four had calcifications and one had a cystic image with an excentric dot suggestive of a scolex; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Brain CT scans compatible with neurocysticercosis. Arrows indicate the lesion (A) cyst with image suggestive of a scolex; (B-E) punctate parenchymal brain calcifications.

Twelve patients had previously diagnosed and treated hydatid disease. Eight of them had previous lung disease and six had previous liver CHD (two had involvement of both organs in the past).

Fifty-two patients were seropositive for antibodies to E. granulosus on EITB (sensitivity 85.24%). Patients with at least one complicated cyst were seropositive in a significantly higher proportion than those with only non-complicated cysts (95.35% versus 61.11%; OR = 14.7; P < 0.001; Table 2). The EITB was consistently positive in all patients with ruptured or infected cysts, with the single exception of one seronegative individual with a ruptured cyst.

Table 2.

Pulmonary hydatid disease features and EITB result

| Positive |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Percent | P | ||

| Organ involvement | Lung, not liver | 29/33 | 87.88 | 0.524 |

| Lung plus other (liver/spleen/soft tissue) | 15/16 | 93.75 | ||

| Number of cysts* | One | 16/18 | 88.88 | 0.545 |

| More than one† | 33/36 | 91.66 | ||

| Complications | No complications | 10/17 | 58.82 | 0.001 |

| Broken, uninfected | 25/26 | 96.15 | ||

| Infected | 17/18 | 94.44 | ||

Considers only patients with abdominal ultrasound or CT evaluation.

Includes 13 patients with a single lung cyst who had other organ involvement.

Interestingly, seroprevalence was quite similar between patients with a single lung cyst and patients with more than one cyst, excluding seven patients with a single lung cyst and without abdominal ultrasound evaluation (16/18, 88.88% versus 33/36, 91.66%; P = 0.545). There were slightly more seropositive cases in patients with involvement of other organs beyond the lung (15/16, 93.75% versus 29/33, 87.88%; P = 0.524).

DISCUSSION

Diagnosis of cystic hydatid disease is based on imaging methods and supported by serologic tests.2,24 The sensitivity and specificity of serology varies depending on assay format, antigen, and the involved organ.23,25,26 Sensitivity of serologic assays in pulmonary CHD ranges around 50-60%, increasing somewhat if the patient has multiple organ involvement or complicated cysts.3,14,23,27 Hepatic cysts seem to produce a stronger immunologic response than do pulmonary cysts.23 In this prospective series of patients with surgically confirmed lung CHD, the overall sensitivity of serology using bovine cyst fluid antigens in an EITB format (85%) was higher than those previously reported for lung disease with diverse methods, with minimal differences between those with and without involvement of the liver or other organs.

This high sensitivity may have been caused by the elevated proportion of patients with complicated cysts in this series of symptomatic patients. The presence of complications (rupture and infection/abscess) was the major influencing factor for a positive serology. Symptoms in CHD are caused not only by the growth of the cyst but also by the presence of complications.1,28 Complications are associated with release of parasite antigens, increasing the sensitivity of serologic assays.18,29 Negative cases on EITB frequently harbor intact or calcified cysts, with minimal or no shedding of antigens.30

In our series, 61.53% of patients had a solitary cyst, the right lung was slightly more affected than the left lung (53.33%), and in both lungs, the lower lobe was the most affected (66.07% and 57.14%). Also, there were multiple lung cysts in 38.46% of cases and bilateral cysts in 21.53% of cases. These results are similar to those shown in previous studies where pulmonary hydatid cysts were solitary in most cases (∼75%),31 with a slight predilection for the right lung (∼60%)14 and frequently located in the lower lobes (∼60%),3 and a minority of cases had multiple pulmonary cysts (∼30%) or bilateral cysts (∼20%).3,32 Interestingly, the number of cysts was not correlated to the chances of being seropositive on EITB, as previously shown with other less specific assays.17,18,23,27 In the sheep model, cyst location, total number of hepatic or pulmonary cysts, or the presence of fertile cysts was significantly associated to a positive EITB.33

Even when brain involvement is a rare presentation,11 we systematically assessed brain compromise by using a lastgeneration CT scanner. The rationale for this assessment was that the scarce number of reported cases has been restricted to symptomatic individuals and thus the possibility of presymptomatic disease had not been ruled out. Because lung invasion reflects successful passage of embryos beyond the liver filter, and based on brain hydatid series in which lung was the most common organ involved after the brain, we chose this population as the one with higher risk for brain infection. No cases of brain CHD were detected. Whether the use of contrast-enhanced CT or brain MRI could have detected small lesions in this cohort and changed the negative result can not be ruled out. However, these were not performed because of increased risk for the participants from the use of iodine contrast on CT and because of cost and low availability in endemic regions for MRI. Of note, several individuals had lesions compatible with neurocysticercosis: four cases of punctuate form calcifications and one apparent cyst with scolex. Imaging of calcified hydatid cysts differs from that of calcified cysticercosis.34,35

The presence or absence of complications is seldom reported in serologic studies of lung hydatid disease. Our findings suggest that not only cyst number and location but also whether there are complicated cysts should be described in detail to allow adequate evaluation of serologic results in lung hydatidosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the medical personnel from the Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery Department of Hospital Nacional Hipolito Unanue and the Hospital Nacional Dos de Mayo for cooperation. We also appreciate the assistance and cooperation of personnel from The Cysticercosis Unit of Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Neurologicas.

Financial support: This study was funded by NIAID/NIH Grant P01AI051976, and Fogarty/NIH Grants DW43001140 and DW43006581.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eckert J, Deplazes P. Biological, epidemiological, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis, a zoonosis of increasing concern. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:107–135. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.1.107-135.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McManus DP, Zhang W, Li J, Bartley BP. Echinococcosis. Lancet. 2003;362:1295–1304. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14573-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morar R, Feldman C. Pulmonary echinococcosis. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:1069–1077. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00108403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rebhandl W, Turnbull J, Felberbauer FX, Tasci E, Puig S, Auer H, Paya K, Kluth D, Tasci O, Horcher E. Pulmonary echinococcosis (hydatidosis) in children: results of surgical treatment. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999;27:336–340. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(199905)27:5<336::aid-ppul7>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burgos R, Varela A, Castedo E, Roda J, Montero CG, Serrano S, Tellez G, Ugarte J. Pulmonary hydatidosis: surgical treatment and follow-up of 240 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;16:628–634. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(99)00304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dakak M, Genc O, Gurkok S, Gozubuyuk A, Balkanli K. Surgical treatment for pulmonary hydatidosis (a review of 422 cases) J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2002;47:689–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keramidas D, Mavridis G, Soutis M, Passalidis A. Medical treatment of pulmonary hydatidosis: complications and surgical management. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;19:774–776. doi: 10.1007/s00383-003-1031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shalabi RI, Ayek AK, Amin M. 15 Years in surgical management of pulmonary hydatidosis. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;8:131–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sotomayor A. Cirugía. Tomo X. Cirugía de Tórax y Cardiovascular. Fondo Edit. UNMSM; Lima, Peru: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aribas OK, Kanat F, Turk E, Kalayci MU. Comparison between pulmonary and hepatopulmonary hydatidosis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;21:489–496. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)01140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altinors N, Bavbek M, Caner HH, Erdogan B. Central nervous system hydatidosis in Turkey: a cooperative study and literature survey analysis of 458 cases. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:1–8. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.1.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khaldi M, Mohamed S, Kallel J, Khouja N. Brain hydatidosis: report on 117 cases. Childs Nerv Syst. 2000;16:765–769. doi: 10.1007/s003810000348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turgut M. Hydatidosis of central nervous system and its coverings in the pediatric and adolescent age groups in Turkey during the last century: a critical review of 137 cases. Childs Nerv Syst. 2002;18:670–683. doi: 10.1007/s00381-002-0667-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottstein B, Reichen J. Hydatid lung disease (echinococcosis/hydatidosis) Clin Chest Med. 2002;23:397–408. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(02)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar A, Lal BK, Chattopadhyay TK. Radiologic diagnosis of hydatid disease of the liver. Trop Gastroenterol. 1992;13:52–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedrosa I, Saíz A, Arrazola J, Ferreirós J, Pedrosa CS. Hydatid disease: radiologic and pathologic features and complications. Radiographics. 2000;20:795–817. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.3.g00ma06795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Force L, Torres JM, Carrillo A, Buscà J. Evaluation of eight serological tests in the diagnosis of human echinococcosis and follow-up. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:473–480. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gadea I, Ayala G, Diago MT, Cuñat A, Garcia de Lomas J. Immunological diagnosis of human hydatid cyst relapse: utility of the enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot and discriminant analysis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:549–552. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.4.549-552.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawn SD, Bligh J, Craig PS, Chiodini PL. Human cystic echinococcosis: evaluation of post-treatment serologic followup by IgG subclass antibody detection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70:329–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ravinder PT, Parija SC, Rao KS. Evaluation of human hydatid disease before and after surgery and chemotherapy by demonstration of hydatid antigens and antibodies in serum. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:859–864. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-10-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang W, Li J, McManus DP. Concepts in immunology and diagnosis of hydatid disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:18–36. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.1.18-36.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ortona E, Rigano R, Buttari B, Delunardo F, Ioppolo S, Margutti P, Profumo E, Vaccari S, Siracusano A. An updateon immunodiagnosis of cystic echinococcosis. Acta Trop. 2003;85:165–171. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verastegui M, Moro P, Guevara A, Rodriguez T, Miranda E, Gilman RH. Enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot test for diagnosis of human hydatid disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1557–1561. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.6.1557-1561.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moro PL, Gonzales AE, Gilman RH. Cystic hydatid disease. In: Strickland T, editor. Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Diseases. Saunders; Philadelphia: 2000. pp. 866–871. [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacPherson CN, Romig T, Zeyhle E, Rees PH, Were JB. Portable ultrasound scanner versus serology in screening for hydatid cysts in a nomadic population. Lancet. 1987;2:259–261. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90839-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shambesh MA, Craig PS, Macpherson CN, Rogan MT, Gusbi AM, Echtuish EF. An extensive ultrasound and serologic study to investigate the prevalence of human cystic echinococcosis in northern Libya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:462–468. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zarzosa MP, Orduna A, Gutierrez P, Alonso P, Cuervo M, Prado A, Bratos MA, Garcia-Yuste M, Ramos G, Rodriguez-Torres A. Evaluation of six serological tests in diagnosis and postoperative control of pulmonary hydatid disease patients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;35:255–262. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(99)00079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dervenis C, Delis S, Avgerinos C, Madariaga J, Milicevic M. Changing concepts in the management of liver hydatid disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:869–877. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simsek S, Koroglu E. Evaluation of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot (EITB) for immunodiagnosis of hydatid diseases in sheep. Acta Trop. 2004;92:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moro PL, Garcia HH, Gonzales AE, Bonilla JJ, Verastegui M, Gilman RH. Screening for cystic echinococcosis in an endemic region of Peru using portable ultrasonography and the enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot (EITB) assay. Parasitol Res. 2005;96:242–246. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-1350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Darwish B. Clinical and radiological manifestations of 206 patients with pulmonary hydatidosis over a ten-year period. Prim Care Respir J. 2006;15:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.pcrj.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dincer SI, Demir A, Sayar A, Gunluoglu MZ, Kara HV, Gurses A. Surgical treatment of pulmonary hydatid disease: a comparison of children and adults. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:1230–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dueger EL, Verastegui M, Gilman RH. Evaluation of the enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot (EITB) for ovine hydatidosis relative to age and cyst characteristics in naturally infected sheep. Vet Parasitol. 2003;114:285–293. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(03)00128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alvarez F, Blazquez MG, Oliver B, Manrique M. Calcified cerebral hydatid cyst. Surg Neurol. 1982;17:163–164. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(82)90267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Micheli F, Lehkuniec E, Giannaula R, Caputi E, Paradiso G. Calcified cerebral hydatid cyst. Eur Neurol. 1987;27:1–4. doi: 10.1159/000116120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]