Abstract

This study examined Expressed Emotion in the families of children and adolescents who were: (1) in a current episode of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), (2) in remission from a past episode of MDD, (3) at high familial risk for developing MDD, and (4) low-risk controls. Participants were 109 mother-child dyads (children ages 8-19). Expressed emotion was assessed using the Five Minute Speech Sample. Psychiatric follow-ups were conducted annually following the Five Minute Speech Sample assessment. Mothers of children with a current or remitted episode of MDD and at high risk for MDD were more likely to be rated high on Criticism than mothers of controls. There were no differences in critical expressed emotion among mothers of children in the current, remitted, or high-risk for depression groups. Higher initial critical expressed emotion was associated with a greater likelihood of having a future onset of a depressive episode in high-risk and depressed participants. Diagnostic groups did not differ in Emotional Overinvolvement. Findings suggest that expressed emotion that is critical in nature may be a relatively stable characteristic feature of the family environments of children with and at high-risk for depression, and may be important in understanding the onset and clinical course of child adolescent depressive disorders.

Depression during childhood and adolescence is a frequent and recurrent problem that is associated with disruptions in emotional, social and occupational functioning into adulthood and increased rates of attempted and completed suicides (Bardone, Moffitt, Caspi, & Dickson, 1996; Rohde, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1994; Weissman et al., 1999). Most adolescents with depression will go on to have recurrent episodes and persistent social impairment between episodes (Puig-Antich et al., 1985b; Weissman et al., 1999). In order to improve upon existing prevention and intervention programs, a better understanding of the contextual factors that contribute to the onset, maintenance, and recurrence of depressive episodes in children and adolescents is crucial.

The development and maintenance of depressive disorders in childhood and adolescence involves the interplay among inherited and acquired biological characteristics and the individual's social environment (Cicchetti & Toth, 1998). In particular, features of the family environment appear to play an important role in child adolescent depression (for reviews see Kaslow, Deering, & Racusin, 1994; Sheeber, Hyman, & Davis, 2001). Interpersonal theories of depression emphasize high levels of rejection in the environments of depressed individuals (Coyne, 1976). Consistent with interpersonal theories, a growing body of literature suggests that the families of children and adolescents with depressive disorders are characterized by low levels of warmth, support, and communication (Messer & Gross, 1995; Puig-Antich et al., 1985a; Sheeber & Sorensen, 1998) and high levels of parent-child negativity, criticism, and conflict (Puig-Antich et al., 1993; Stark, Humphrey, Crook, & Lewis, 1990). Despite this emerging picture, relatively few studies have examined the family environments of clinical samples of depressed children and adolescents. Finally, existing studies have relied heavily on self-report measures of the family environment, which may be biased by lack of objectivity in parents' and children's descriptions of their attitudes and behaviors (Sheeber et al., 2001).

Another limitation of the extant literature on the role of the family environment in child and adolescent depression is that existing studies have been unable to tease out whether disruptions in family environment serve as precursors or sequelae of child and adolescent depressive disorders (Birmaher, Ryan, Williamson, & Brent, 1996). Some evidence suggests that adverse family relationships precede the onset of depression. For example, a large body of literature demonstrates increased levels of hostility and decreased levels of warmth in the families of children at risk for depression as a result of having a parent with MDD (Downey & Coyne, 1990). Only a few studies have directly compared the family environments of children at risk for MDD with those who have already developed MDD. Birmaher et al. (2004) found that children who had already developed MDD showed lower levels of communication and warmth and higher levels of parent-child tension than children at low-risk for depression; however, they found no differences in family relationships between children at high and low familial risk for developing MDD. Stein et al. (2000) also found that the family relationships of children with MDD were more discordant than those of low-risk children, however, the families of high-risk children showed scores in between the MDD and low-risk families. Stein et al. (2000) suggest that measures that access the affective environment of the family may be more useful in capturing potential differences in family functioning among families of low-risk, high-risk, and MDD children.

Another limitation of the existing literature on family environment and child and adolescent depression has been an absence of studies that have examined the family environments of children outside of a depressive episode. In one of the only studies to address this question, Puig-Antich et al. (1985b) found that moderate interpersonal problems appear to improve on recovery, but that more severe interpersonal problems, including those in the family environment, persist during recovery and remission. This suggests that there may be residual effects of depression on children's family environments. Although we use the term “remitted” specifically to refer to depressive symptoms, it is important to recognize that interpersonal and psychosocial impairment related to depressive symptoms may persist even after symptoms have resolved.

Familial expressed emotion is one index of the affective climate of the family that offers promise in understanding risk for and course of depression in children and adolescents. The present study examined expressed emotion in the mothers of youth with current depression, remitted depression, and youth at high familial risk for depression (based on having at least one first-degree and one second-degree relative with a history of affective disorder) in comparison to a sample of low-risk normal controls. Expressed emotion is a measure of family members' emotional attitudes toward a child or other family member that focuses on the level of criticism and emotional overinvolvement expressed toward the family member. The Five Minute Speech Sample (Magana et al., 1986) is a brief method of assessing expressed emotion in which parents are audiotaped while describing their child and their relationship with him or her for five minutes. Transcripts are later scored along two dimensions of expressed emotion: (1) Criticism and (2) Emotional Overinvolvement. The Criticism dimension reflects critical and hostile attitudes and includes making a negative opening remark, producing evidence of a negative relationship with the child, or making one or more criticisms during the course of the speech sample. Parental Criticism on the Five Minute Speech Sample has been related to observed parental antagonism, negativity, disgust, harshness, and low responsiveness in parent-child interactions (McCarty, Lau, Valeri, & Weisz, 2004). The Emotional Overinvolvement dimension reflects intrusive overconcern about the child, and includes evidence of self-sacrifice or over-protectiveness, exaggerated emotional displays by the speaker, and overidentification with the child.

Although extensive research over the past three decades has indicated a strong association between expressed emotion and poor clinical outcome in adult schizophrenic patients and relapse in adult depressives (Butzlaff & Hooley, 1998; Hooley, Orley, & Teasdale, 1986), only a handful of studies have examined the effects of expressed emotion on the onset and course of depression in children and adolescents. These few studies have found higher rates of critical expressed emotion in the families of depressed inpatient children (Asarnow, Tompson, Hamilton, Goldstein, & Guthrie, 1994) and in mothers of an outpatient sample of depressed children (Asarnow, Tompson, Woo, & Cantwell, 2001) as compared to community and psychiatric controls. Higher rates of critical expressed emotion also have been associated with an increased number of acute episodes of mood disorders in preadolescent children (Hirshfeld, Biederman, Brody, & Faraone, 1997) and lower rates of recovery in samples of depressed children (Asarnow, Goldstein, Tompson, & Guthrie, 1993; McCleary & Sanford, 2002).

Although studies of schizophrenic adults suggest that the duration of critical expressed emotion is related to chronicity of disorder, several studies have found that critical expressed emotion does not improve during the remission of schizophrenic episodes (Hogarty et al., 1986; Hooley & Richters, 1995; Tarrier et al., 1988). No child studies that we are aware of have directly examined changes in expressed emotion following recovery from depression, although Vostanis and Nicholls (1995) found that maternal expressed emotion ratings did not change over a 9-month period among children with emotional disorders.

Critical expressed emotion in the families of children with, and at risk for, depression is likely to result from complex transactional processes between the parent and child (Anderson, Lytton, & Romney, 1986; Patterson, DeBaryshe, & Ramsey, 1989; Sameroff, 1975). Research suggests that negative attitudes and parenting behaviors among depressed mothers and among mothers of children with behavior problems are at least partially driven by children's aversive behaviors (Hammen, Burge, & Stansbury, 1990; Hetherington & Martin, 1986; Patterson, 1982). With respect to critical expressed emotion, children who are depressed, or who are temperamentally prone to later depression as a result of being high in negative reactivity, may engage in problematic child behaviors that elicit critical attitudes from parents (Asarnow et al., 1993; McCarty et al., 2004). Depressed children and their parents may engage each other in mutually reinforcing, escalating cycles of criticism and negative affect, similar to the coercive cycles Patterson (1982) observed among aggressive children and their parents. Miklowitz's (2004) transactional model of the development of high expressed emotion in families suggests that the “seeds” for high expressed emotion typically begin with a child who has a temperamental, cognitive, or behavioral vulnerability toward psychiatric disorder, in conjunction with a parent (or parents) who, through his or her own temperamental and psychiatric vulnerability, is prone to react to the child's vulnerabilities with frustration or distress. This pairing results in frequent critical interactions, which through repeated exposure, influence the child's self-schemas, attributions, and capacity for emotion regulation in ways that further increase the likelihood that the child will become depressed. Once depressed, the critical patterns established in the family system perpetuate the child's problems, impeding recovery and increasing interpersonal stresses that may be associated with subsequent recurrent episodes.

Although initial evidence for a link between child and adolescent depression and critical expressed emotion is strong, there is less evidence for the validity and predictive utility of the Emotional Overinvolvement component of expressed emotion in child and adolescent samples (McCarty et al., 2004; Wamboldt, O'Connor, Wamboldt, Gavin, & Klinnert, 2000). One explanation for this deviation from the adult expressed emotion literature may be related to the degree of age-appropriate parental involvement and praise required by children. Whereas a high amount of parental praise may be considered inappropriate for adult patients, parental praise may be developmentally appropriate and even beneficial for children and adolescents (McCarty & Weisz, 2002). For example, McCarty and Weisz (2002) found that higher numbers of positive comments among the families of clinically referred youth were associated with lower levels of internalizing problems. Although most studies have not found an association between Emotional Overinvolvement and children's psychiatric outcomes (Asarnow et al., 1994; Asarnow et al., 2001; McCarty & Weisz, 2002), a few studies have suggested that children's anxiety may be associated with higher parental Emotional Overinvolvement (Hirshfeld et al., 1997; Stubbe, Zahner, Goldstein, & Leckman, 1993).

The present study extends the research on parental expressed emotion and child and adolescent depression by examining whether elevated critical expressed emotion is evident (1) in families of children at high-risk for depression, (2) in families after children recover from a previous episode of MDD, or, (3) only during an acute depressive episode. We also examine how baseline critical expressed emotion is associated with the longitudinal course of depression. We address these questions by investigating levels of expressed emotion in the families of children and adolescents from four groups varying in depressive status and risk for depression: (a) children who are in a current episode of MDD, (b) children with a past episode of MDD who are currently in remission, (c) nondepressed children at high familial risk for developing MDD in the future, and (d) nondepressed controls at low-risk for developing MDD in the future based on family history. We hypothesized higher rates of critical expressed emotion among the families of high-risk children and children with current or past episodes of MDD in comparison to children from low-risk families. We also examined whether critical expressed emotion predicted the course of depression in youth at risk for a future depressive episode, including youth at high familial risk for depression as well as MDD youth with a current or remitted episode of depression. We hypothesized that high critical expressed emotion at baseline would be associated with a greater likelihood of experiencing a future episode of depression during the follow-up period.

In addition, we conducted exploratory analyses to examine whether Emotional Overinvolvement, or any of its subcomponents, was associated with child depression. We predicted that Emotional Overinvolvement would not be related to child depression, with the exception of positive remarks. We expected positive remarks to be lower in the families of children with and at high risk for MDD based on McCarty and Weisz' (2002) finding that positive comments were associated with lower levels of internalizing, as well as general evidence of lower warmth and positivity in depressed and high-risk families (see Goodman & Gotlib, 1999; Sheeber et al., 2001).

Method

Participants

This report includes data from 109 mother-child dyads participating in a longitudinal study of neurobehavioral factors in pediatric affective disorder (see Birmaher et al., 2000). Children (57 female) ranged in age from 8 to 19 (M = 13.24; SD = 2.58). Mothers were biological mothers who reported having always lived with the child at least part of the time. Five Minute Speech Sample data also were collected from fathers when available, but this procedure did not generate enough data from fathers to be included in this report. Dyads were divided into four groups based on the child's current psychiatric diagnoses at the time of the Five Minute Speech Sample assessment: (a) MDD Current; n = 29; (b) MDD Remitted; n = 18; (c) High-Risk (HR); n = 21; and Low-Risk (LR); n = 41. In order to ensure significant impairment and to be consistent with previous research on family functioning in child and adolescent depression, participants had to meet full criteria for a primary diagnosis of current or past MDD to be included in the MDD current or remitted group. However, they were allowed to have secondary comorbid disorders. One-fourth (26%) of depressed participants had a comorbid diagnosis of Dysthymic Disorder, 47% of depressed participants (62% current and 22% remitted) had a current comorbid anxiety disorder (Separation Anxiety Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, or Social Phobia), and 32% (38% current and 22% remitted) had a current comorbid behavioral disorder (Conduct Disorder, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, or Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder). One-fourth (24%) of high-risk participants had a current behavioral disorder and 1 participant had a current anxiety disorder.1

Inclusion Criteria

Children with MDD met diagnostic criteria according to DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) or DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) classification. Following Frank et al. (1991), MDD Remitted children were considered in remission at follow-up if they were symptom free from depression for 8 consecutive weeks. High-risk (HR) children were required to have at least one first-degree and one second-degree relative with a lifetime history of: (1) childhood-onset depression; (2) recurrent depression; (3) bipolar disorder; or (4) psychotic depression. In addition, HR children were required to have no lifetime episode of any mood disorder. Low-risk (LR) children were required to be free of any lifetime psychopathology. In addition, they were required to have no first-degree relatives with a lifetime episode of any mood or psychotic disorder; no second-degree relatives could have a lifetime history of childhood-onset, recurrent, psychotic, or bipolar depression or schizoaffective or schizophrenic disorder; and no more than 20% of second-degree relatives could have a lifetime episode of MDD.

Exclusion Criteria

Since the children in this study were originally recruited to participate in a broader set of biological protocols (Birmaher et al., 2000), the following exclusionary criteria applied at the time of the initial interview: (1) the use of any medication with central nervous system effects within the past 2 weeks; (2) significant medical illness; (3) extreme obesity or growth failure; (4) IQ of 70 or less; (5) inordinate fear of intravenous needles; and (6) specific learning disabilities.

Procedures

All study procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh's Institutional Review Board. Dyads were recruited from 3 sources: (1) community advertisements (primarily radio and newspaper ads), (2) inpatient and outpatient clinics at a major medical center in which children or their parents were being treated, and (3) referrals from other research studies or other participants in the present study. Data on recruitment source was collected for 85% of the present sample. This data suggests that for the depressed participants, approximately 69% were recruited from the community, 23% from medical clinics, and 8% from research studies. Participants with current and remitted MDD did not differ significantly from each other in recruitment source (χ2 = 3.37, p = .34). For low-risk participants, approximately 82% were recruited from the community, 3% from medical clinics, and 15% from research studies, and for high-risk participants, approximately 56% were recruited from the community, 6% from medical clinics, and 39% from research studies. High-risk and low-risk participants did not differ significantly from each other in recruitment source (χ2 = 5.97, p = .11); however, a greater proportion of low-risk participants were recruited from the community then depressed participants (χ2 = 7.87, p < .05).

Children and their parents were required to sign assents and informed consents, respectively. Structured diagnostic interviews were administered to establish lifetime and present psychiatric diagnoses and familial risk for affective disorder. Qualifying children completed a battery that included psychophysiological tests and questionnaires about the psychosocial environment (see Birmaher et al., 2000). Dyads were invited to return for annual follow-up visits that included follow-up psychiatric interviews for children and re-administration of tasks. During the visits, mothers completed the Five Minute Speech Sample, which was later coded from audiotape. This report utilizes Five Minute Speech Sample data from the first visit in which the mother completed the Five Minute Speech Sample (referred to as the baseline visit). Because the Five Minute Speech Sample was not included in the initial years of this longitudinal study, the baseline visit used in this report was not always the participants' first year of participation in the larger study. The baseline visit corresponded with the initial year of participation in the study for 38% of the sample, but the Five Minute Speech Sample was completed at a follow-up visit for 62% of the sample (9% year one, 14% year two, 8% year three, 8% year four, 6% year five, 3% year six, 6% year seven, 7% year eight, and 1% year nine). However, psychiatric evaluations were completed each year, thus the current child diagnostic information included in this report was collected at the same time as the baseline Five Minute Speech Sample.

Dyads were invited to continue to return for annual follow-up psychiatric interviews following completion of the baseline visit. As this study was part of a 20-year longitudinal project, the duration of the follow-up period varied significantly depending upon the length of time since the participants' initial entry into the study. The present report includes longitudinal follow-up psychiatric information for high-risk and depressed participants who were followed for a minimum of 5 years after completing the baseline visit. Thus, more recent participants in the longitudinal study were not included in this analysis. Five years was selected as the minimum to ensure that a reasonable period of time had passed to observe first onsets of depression in high-risk youth as well as a recurrence of depression in depressed youth. Using this approach, follow-up data were available for 17 High-Risk participants (81%), 19 MDD Current participants (66%), and 12 MDD Remitted participants (67%). The length of follow-up intervals ranged from 5 to 14 years from the baseline visit (M = 8.77, SD = 2.30). Because the length of follow-up intervals varied between participants, the length of the follow-up period from the baseline visit was included as a covariate in all longitudinal analyses.

Instruments

Child Structured Diagnostic Interviews

Each child and his or her parent(s) were interviewed to determine the child's psychiatric history. At intake, child lifetime and present psychiatric symptomatology was assessed using a structured interview. In the initial years of the study, children were administered the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Epidemiologic version (K-SADS-E; Orvaschel, Puig-Antich, Chambers, Tabrizi, & Johnson, 1982) to assess lifetime history and the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (6–18 Years)-Present Episode version (KSADS-P; Chambers et al., 1985) to assess current episodes. During the later years of the study, we switched to the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia in School-Age Children—Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL, Kaufman, Birmaher, Brent, & Rao, 1997), which combines aspects of the K-SADS-P and K-SADS-E into one interview. Parents and children were interviewed separately, with clinical interviewers integrating data from both informants to arrive at a final diagnosis. At each annual follow-up assessment, participants less than 18 years were re-interviewed using the KSADS. Again, parents and children were interviewed separately with clinicians integrating data from both informants. The interview period covered the time from the last assessment up until the time of the interview. For participants 18 years or older, the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (SCID; Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1990) was administered to the participant only also covering the time from the last assessment up until the time of the interview. From the follow-up interviews, we constructed a variable reflecting the length of time since the last episode of depression for MDD youth in remission to include as a covariate in analyses.

Family History Information

To determine high-risk and low-risk status, we also collected information about psychiatric history among first and second-degree relatives. For the majority of high and low-risk families (77%), we collected this information using mother and father report on the Family History Interview (Weissman et al., 1986), and through direct interview of at least two relatives on both the paternal and maternal side of the family. Parents signed consent forms permitting the research staff to contact relatives to solicit their participation in the study. Relatives were interviewed about their own psychiatric history using the K-SADS-E for relatives aged 6 to 18 years and the SCID-I for adult relatives. When direct interview of relatives was not possible, we based familial psychiatric history on mother and father report on the Family History Interview. Diagnoses obtained by interviews with family members have similar specificity but less sensitivity than diagnoses obtained by direct interview (Weissman et al., 1986).

All interviews were carried out by trained BA- and MA-level research clinicians. Interrater reliabilities for diagnoses assessed during the course of this study were estimated to be k ≥ 0.70. The results of the interview were presented at a consensus case conference with a child psychiatrist, who reviewed the findings and preliminary diagnosis and provided a final diagnosis based on DSM-III-R or DSM-IV criteria.

Five Minute Speech Sample (Magana et al., 1986)

The Five Minute Speech Sample is a brief procedure for assessing expressed emotion attitudes from a speech sample recorded by a family member. Mothers were instructed to speak for five minutes without any interruptions about the target child and how they get along together. Audiotaped recordings of the Five Minute Speech Sample were coded by a certified rater who was blind to diagnostic information about the child. Interrater reliability was assessed regularly (kappa = .87). Each speech sample was scored based on criteria developed by Magana-Amato et al. (1993, 1986). A Five Minute Speech Sample is scored high on Criticism if any of the following criteria are met: negative initial statement, negative relationship rating, or one or more criticisms. A borderline high Criticism score is assigned if the parent expresses dissatisfaction with the child that is not extreme enough to be rated as criticism (Magana-Amato, 1993). A high Emotional Overinvolvement rating is assigned if the parent reports self-sacrificing or overprotective behavior, breaks down in tears, or shows a combination of any of the following: excessive detail about the past, statements of positive attitude (such as expressions of love for the child or willingness to do anything for the child), and/or five or more positive remarks about the child. A borderline high Emotional Overinvolvement score is assigned if the parent shows moderate evidence of self-sacrificing or overprotective behavior, or if they show only one of the latter three indicators of Emotional Overinvolvement (Magana-Amato, 1993). Magana-Amato (1993) recommends that borderline expressed emotion be counted as high in samples where parents might be reluctant to express critical statements, such as toward children (as opposed to adult offspring). Following this recommendation and most previous research with child samples (e.g. Hirshfeld et al., 1997; Jacobsen, Hibbs, & Ziegenhain, 2000; Kershner, Cohen, & Coyne, 1996; Stubbe et al., 1993), borderline expressed emotion scores were included in the high category.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents demographic characteristics of participants by diagnostic group. As shown in Table 1, Chi-square tests revealed no group differences in gender or ethnicity (white vs. non-white). One-way ANOVA's revealed that there was no group difference in socioeconomic status (SES) as measured using the Hollingshead Four-Factor Index (Hollingshead, 1975); however, there was a group effect for child age (F(3,105) = 3.35, p < .05). Post-host LSD tests indicated that participants in the MDD remitted group were significantly older than those in the MDD current, High-Risk, and Low-Risk groups. Age was included as a covariate in subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants.

| MDD Current

(n = 29) |

MDD Remitted

(n = 18) |

High-Risk

(n = 21) |

Low-Risk

(n = 41) |

Statistic | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (% Female) | 58.6 | 38.9 | 57.1 | 51.2 | χ2[3] = 1.98 | Φ = .14 |

| Ethnicity (% White) 1 | 86.2 | 88.9 | 100.0 | 90.2 | χ2[3] = 2.96 | Φ = .17 |

| SES (Hollingshead)2 | ||||||

| M | 41.9 | 45.5 | 43.9 | 49.5 | F[3,100] = 2.36 | ηp2 = .07 |

| SD | 11.9 | 11.1 | 10.6 | 13.1 | ||

| Child Age | ||||||

| M | 12.9a | 14.9a, b | 13.2 | 12.8b | F[3,105] = 3.35* | ηp2 = .09 |

| SD | 2.8 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 2.6 |

Groups sharing same superscript significantly different with p ≤ .05.

p < .05;

p < .01.

% White did not vary for mothers and children. Non-white ethnicity included African American (n = 6), Biracial (n = 3), and Indian (n = 1).

SES data were missing for 5 families.

Diagnostic Group and Expressed Emotion

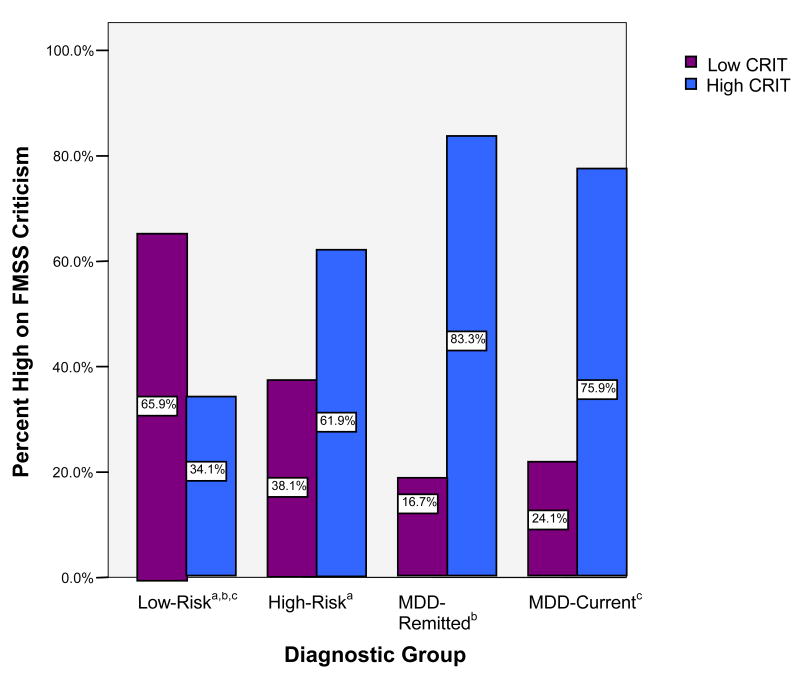

Binary logistic regression analyses were conducted predicting expressed emotion from child diagnostic group, controlling for child age. Models were fit separately for Emotional Overinvolvement and Criticism scores. As shown in Table 2, diagnostic group was significantly related to Criticism scores (χ2df=4 = 18.95, p < .001; see Figure 1)2. Compared to mothers of Low-Risk children, the likelihood of scoring high on Criticism was greater among mothers with children in the MDD Current, MDD Remitted, and High-Risk groups. Children with current vs. remitted MDD did not differ from each other in likelihood of receiving a high Criticism score (B = .47, p =.55, odds ratio [OR] = 1.60, 95% confidence interval [CI] = .34-7.47). Among mothers of children with remitted MDD, the likelihood of receiving a high Criticism score did not vary as a function of the length of time since the child's last episode of MDD (B = -.01, p = .75, odds ratio [OR] = .99, 95% confidence interval [CI] = .92-1.07). High-risk children did not differ significantly from children with current MDD (B = -.66, p = .29, odds ratio [OR] = .52, 95% confidence interval [CI] = .15-1.76) or remitted MDD (B = -1.13, p = .15, odds ratio [OR] = .32, 95% confidence interval [CI] = .07-1.52) in likelihood of receiving a high Criticism score. This pattern of findings was replicated controlling for the presence of a current comorbid diagnosis of dysthymic disorder (χ2df=3 = 17.85, p < .001), anxiety disorder (χ2df=5 = 20.02, p < .001) and behavioral disorder (χ2df=5 = 20.02, p < .001).

Table 2.

Binary Logistic Regression Analyses Predicting Likelihood of Scoring High on Critical Expressed Emotion from Child Diagnostic Group, Controlling for Child Age

| Predictor | Model χ2df=4 | B | odds ratio [OR] | 95% confidence interval [CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDD Current vs. Low-Risk | 1.80*** | 6.06 | 2.08 - 17.64 | |

| MDD Remitted vs. Low-Risk | 2.27** | 9.70 | 2.29 - 41.11 | |

| High-Risk vs. Low-Risk | 1.14* | 3.14 | 1.05 - 9.37 | |

| Child Age | -.00 | 1.0 | .84 - 1.18 | |

| 18.95*** |

p ≤ .05.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Percentage of each diagnostic group scoring low and high on Five Minute Speech Sample Criticism.

Note: FMSS = Five Minute Speech Sample. CRIT = Criticism. Borderline scores included with high scores.

a, b, c groups with the same subscript differ significantly at p ≤ .05

Diagnostic group was not associated with Emotional Overinvolvement scores (χ2df=4 = 2.33, p=0.68). As previous research indicates that the individual criteria for Emotional Overinvolvement may be differentially associated with child outcomes (e.g. McCarty & Weisz, 2002), we also examined associations between diagnostic group and each Emotional Overinvolvement criterion (see Table 3). There was only one instance of an emotional display, so this criterion was not considered further. As shown in Table 3, diagnostic group did not predict statements of attitude, self-sacrificing/overprotective behavior, or excessive detail about the past. However, a one-way ANOVA revealed that diagnostic groups differed significantly in the number of positive remarks made by mothers (F(3,105) = 2.90, p < .05; ηp2 = .08). Post-hoc LSD tests indicated that mothers of both currently and previously depressed children made fewer positive remarks about their children than mothers of low-risk children.

Table 3.

Emotional Overinvolvement Criteria Ratings by Diagnostic Group

| EE Criterion | MDD- Current

(n = 29) |

MDD- Remitted

(n = 18) |

HR

(n = 21) |

LR

(n = 41) |

χ2/F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Sacrificing (%) | 31.0 | 16.7 | 14.3 | 14.6 | χ2[4] = 5.20 |

| Emotional Display (%) | 3.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A1 |

| Statement of Attitude (%) | 13.8 | 11.1 | 9.5 | 14.6 | χ2[4] = 0.95 |

| Number Positive Remarks | 2.9 a | 2.7 b | 3.3 | 5.2 a, b | F[3,105] = 2.90* |

Age was included as a covariate in all analyses.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

groups with the same subscript differ significantly with p ≤ .05;

Too few participants were rated high in emotional display to conduct statistical analyses.

Longitudinal Analysis

We first examined rates of new onsets of depression throughout the follow-up period. A first onset of depression was diagnosed throughout the follow-up period for 8 high-risk participants (47%). A new episode of depression was diagnosed for 16 participants who were in a current episode of depression at the baseline visit (84%), and 8 participants whose depression was in remission at the baseline visit (67%). One of the previously remitted participants developed Dysthymic Disorder and all others developed MDD.

Next, we examined whether level of Criticism or Emotional Overinvolvement measured at the baseline assessment predicted which children went on to develop a future episode of depression during the follow-up period. As high-risk participants and those with current or remitted MDD were all considered at risk for future onsets of depressive episodes, this analysis included participants from all three groups at high risk for future depression. We did not have power to conduct separate analyses within each group because of small sample sizes (group N's range from 12-19); however longitudinal data were available for 48 participants across the three groups. A dichotomous variable was created to indicate the presence or absence of a future episode of depression during the follow-up period. Binary logistic regression analyses were conducted predicting future episodes of depression from expressed emotion at the baseline visit. Models were fit separately for Emotional Overinvolvement and Criticism scores. These models included covariates for child's age at the baseline visit, the length of the follow-up period, and the child's diagnostic group (HR vs. MDD current vs. MDD remitted) at the baseline assessment.

Criticism score at the baseline assessment predicted the onset of a future episode of depression (B = 1.65, p < 0.05, odds ratio [OR] = 5.20, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.14 – 23.73). Compared to participants whose mothers were rated low in critical expressed emotion, the likelihood of developing a future episode of depression was greater among participants whose mothers were rated high in critical expressed emotion. Specifically, 77% of participants whose mothers were initially rated high in critical expressed emotion developed a future episode of depression compared to 43% of participants whose mothers were initially rated low in critical expressed emotion. Results were replicated excluding the one participant who developed Dysthymic Disorder rather than MDD. Emotional Overinvolvement scores at the baseline FMSS assessment did not predict the onset of a future episode of depression (B = .25, p = .73, odds ratio [OR] = 1.28, 95% confidence interval [CI] = .32 – 5.08).

Discussion

In this study we found that mothers of children and adolescents with current depression, remitted depression, and those at high familial risk for depression all demonstrated higher levels of critical expressed emotion toward their children than mothers of low-risk control youths, and that this critical expressed emotion predicted future onsets of depressive episodes. Our findings are consistent with previous investigations of expressed emotion in the families of currently depressed children and adolescents (Asarnow et al., 1994; Schwartz, Dorer, Beardslee, Lavori, & Keller, 1990) in demonstrating that critical expressed emotion is a highly prevalent and characteristic feature of the family environment of depressed children and adolescents. Specifically, in the present study, 76% of mothers of currently depressed participants were rated as borderline or high on criticism.

We expanded on previous research by comparing maternal expressed emotion in the families of currently depressed youth to maternal expressed emotion in children at risk for depression and after remission. This analysis suggested that maternal critical expressed emotion did not vary across the mothers of youths vulnerable to depression, during a depressive episode, or after a depressive episode has remitted. With regard to high-risk youth, 66% of mothers of high-risk children were rated borderline or high on the criticism dimension of expressed emotion (compared to only 34% of low-risk mothers). Heightened criticism in the families of high-risk children is likely a result of both parent and child characteristics associated with familial risk for affective disorder, such as temperament and emotional reactivity. In fact, researchers have suggested that the influences of expressed emotion may be bidirectional, with more difficult children eliciting higher levels of critical expressed emotion from their parents (Asarnow et al., 1993; Asarnow et al., 2001; McCarty et al., 2004).

In the remitted group, maternal critical expressed emotion was rated as borderline or high in 83% of the families of formerly depressed children and adolescents, suggesting that the reduction of depressive symptomatology in children and adolescents does not necessarily translate to reduced levels of critical expressed emotion in the family environment. This finding differs from some of the adult schizophrenic literature (e.g. Tarrier et al., 1988), but is consistent with previous evidence regarding the continuity of expressed emotion (Vostanis & Nicholls, 1995) and other aspects of family relationships (Puig-Antich et al., 1985b) following remission of child and adolescent mood disorders. One possible explanation for this finding is that the experience of a depressive episode may have some degree of “scarring” effect on family relationships. The finding of critical expressed emotion in the families of at-risk, depressed and remitted children also highlights the possibility that family environments may have stable characteristics that, once entrenched, are less variable in response to mood changes in children and adolescents.

This possibility is consistent with Miklowitz's (2004) transactional model, which suggests that critical expressed emotion is the result of disturbances in the emotional climate of the family system that become increasingly entrenched over time. Families with depressed and high-risk children often are characterized by genetic and temperamental vulnerability toward emotion dysregulation in both the child and parent, as well as environmental factors such as stress and poor social support that limit parental resources for adaptively managing a challenging child (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999; Sheeber et al., 2001). Parental expressed emotion also has been associated with negative cognitive biases and attributions of children's negative behaviors as stable, idiosyncratic to, and controllable by the child (Bolton et al., 2003), and may be a marker of parental psychopathology or impairment. This combination of factors may trigger a cascade of mutual criticism and negativity that is self-perpetuating (e.g. Patterson, 1982), and results in the child's experience of frequent exposure to critical parental attitudes and interactions.

The current study also expanded upon previous research to address the temporal sequence of maternal expressed emotion and child and adolescent depression by examining the role of critical expressed emotion in trajectories of depression over a follow-up period spanning 5 or more years. We found that high-risk and depressed youth (both current and remitted at the time of the initial assessment) were more likely to develop a future episode of depression if their mothers were initially rated high in critical expressed emotion. This difference was striking, with 77% of participants whose mothers were initially rated high in critical expressed emotion developing a future episode of depression compared to 43% of participants whose mothers were initially rated low in critical expressed emotion. This finding is consistent with research suggesting that critical expressed emotion is predictive of the course of depression in adults (e.g. Hooley et al., 1986). It is also consistent with reports of lower rates of recovery at one year in MDD youth with high parental critical expressed emotion (Asarnow et al., 1993; McCleary & Sanford, 2002). However, it extends these findings to first onset of depression in high-risk youth and recurrence of depression in depressed youth over a longer follow-up period.

Exposure to high rates of maternal criticism may increase the likelihood that a high-risk child will develop depression, perpetuate a depressive episode once it has begun, or trigger relapse in a previously depressed child through several mechanisms. Maternal criticism may increase the frequency and intensity of children's negative affect and may also interfere with the development of adaptive skills for regulating emotion, which typically are acquired and refined in the context of parent-child interactions (Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers, & Robinson, 2007). Critical expressed emotion also may be associated with child and adolescent depression through its influence on children's cognitive style. Parental criticism may reinforce the depressed child's negative cognitive biases about his/ herself, others, and the world that have been associated with the development and maintenance of depressive symptoms (Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989).

We did not find any associations between Emotional Overinvolvement and diagnostic status. This is consistent with the majority of research on expressed emotion in the families of depressed children (e.g. Asarnow et al., 1994), although a few studies have reported an association between Emotional Overinvolvement and anxiety (e.g. Stubbe et al., 1993). The present findings are consistent with recent reports that the Emotional Overinvolvement dimension of expressed emotion may not be applicable to child and adolescent samples (McCarty & Weisz, 2002). This conclusion is further supported by our subcomponent analyses that showed that mothers of controls made a higher number of positive remarks (one of the primary criteria for a high score on Emotional Overinvolvement) than mothers of currently and previously depressed children. This is consistent with the findings of Kershner et al. (1996) and McCarty and Weisz (2002), and suggests that the positive remarks component of Emotional Overinvolvement may actually be protective against child psychopathology.

Strengths and Limitations

Several limitations of the present study should be noted. First, the sample was relatively small and included a broad age range of children, thus making it difficult to detect small to moderate effects and developmental changes in the associations between expressed emotion and diagnostic status. The sample also was predominantly Caucasian and middle class, limiting the generalizability of findings to other populations. As a result of our small sample and differential inclusion/exclusion criteria for child psychiatric comorbidities across our diagnostic groups, we were unable to examine how comorbid child disorders influence expressed emotion. As critical expressed emotion has been linked to child behavioral disorders (Peris & Baker, 2000), further research exploring how comorbid behavioral disorders influence the presence, course, and experience of critical expressed emotion in families of depressed children (e.g. Asarnow et al., 1994) is important. We were able to replicate our findings controlling for the presence of child comorbid behavioral and anxiety disorders, but, due to sample size limitations, were not able to conduct separate analyses within subgroups of children carrying different comorbid diagnoses.

We also were unable to examine the effects of maternal psychopathology on expressed emotion because maternal psychopathology was an exclusion criterion in some groups but not in others, because data were not always collected on maternal psychopathology at the same time point as the Five Minute Speech Sample assessment, and because of limited statistical power. This is a very important area as previous research has suggested that parental psychopathology is related to expressed emotion (Bolton et al., 2003; Schwartz et al., 1990), thus parental psychopathology could play a role in the understanding the longitudinal course of depression. For example, parental psychopathology could increase the likelihood that a parent will be high in critical expressed emotion, or, the presence of both critical expressed emotion and parental psychopathology could interact to amplify the negative effects of each on a child's depression risk or trajectory. Future research is needed to test these possibilities.

Additionally, without a psychiatric comparison group, the study is not able to address whether heightened expressed emotion is specific to the families of depressed children. The study was also limited to expressed emotion data from mothers. Future research on parental expressed emotion and child adolescent depression should include a focus on paternal expressed emotion and its differential associations with children's depressive illness. Finally, although we were able to use longitudinal data to examine the course of depression among high-risk and depressed youth, small sample sizes limited our ability to conduct within-group analyses of longitudinal course.

Despite these limitations, this study has several notable strengths. It includes a rigorously diagnosed clinical sample of depressed children and adolescents. It also includes children at high familial risk for depression based on an extensive family history as well as children with a past history of depression followed into remission. Finally, it includes longitudinal data spanning a minimum of five years, facilitating an examination of the role of expressed emotion in the course of child and adolescent depression.

Implications for Future Research, Policy, and Practice

The results of this study suggest that expressed emotion likely plays a role in the onset, maintenance, and recurrence of depression in children and adolescents. As such, familial criticism may be a critical target to address in interventions aimed at breaking the cycle of depression in families that suffer from this debilitating disorder. Treatments that address parental criticism and negativity toward the child (as well as child behaviors that elicit negative parental responses) may be effective in reducing levels of depression and in maintaining children's recovery from depression. Findings also suggest that preventive interventions among the families of children at high risk for depression could be effective in decreasing children's likelihood of experiencing future episodes of MDD (e.g. Beardslee & Gladstone, 2001). To the extent that critical expressed emotion also represents a risk factor for relapse, continued critical environments among children and adolescents with a history of depression may also be a crucial target for interventions aimed at relapse prevention.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grants P01 MH41712 (Neal D. Ryan, PI, Ronald E. Dahl, Co-PI), K01 MHO73077 (Jennifer S. Silk, PI) and K01 MH001957 (Douglas E. Williamson, PI).

We thank Laura Trubnick, Michele Bertocci, Ian Kane, Trevor Baker, and the staff of the Child and Adolescent Neurobehavioral Laboratory for their invaluable contributions to assessing the participants in this study. We are grateful to Satish Iyengar for statistical consultation, to Sibyl Zaden for coding speech samples, and to Joanna Prout for feedback on the manuscript.

Footnotes

The relatively low rates of behavioral and anxiety disorders in the high-risk group is a result of the sampling strategy. At initial enrollment into this longitudinal study, behavioral and anxiety disorders were treated as exclusion criteria for high-risk participants. However, the Five Minute Speech Sample and current psychiatric data presented in this report were collected at a follow-up visit for 62% of participants. Thus, several high-risk participants had developed a behavioral or anxiety disorder at the time of the visit included in this report.

To control for the influence of borderline Criticism scores, we also computed a model predicting Criticism from diagnostic group excluding the 31 families who received a borderline score. The influence of diagnostic group on Criticism scores remained significant excluding borderline cases (χ2df=3 = 17.01, p < .001). The only difference in the findings is that the difference between HR and LR families was reduced to a trend (B = 1.22, p = .08, odds ratio [OR] = 3.38, 95% confidence interval [CI] = .85-13.40), which was likely due to reduced power.

References

- Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB. Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review. 1989;96:358–372. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd Edition Revised (DSM-III-R) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KE, Lytton H, Romney DM. Mothers' interactions with normal and conduct-disordered boys: Who affects whom? Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:604–609. [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow J, Goldstein MJ, Tompson M, Guthrie D. One-year outcomes of depressive disorders in child psychiatric in-patients: Evaluation of the prognostic power of a brief measure of expressed emotion. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1993;34:129–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow J, Tompson M, Hamilton EB, Goldstein MJ, Guthrie D. Family expressed emotion, childhood-onset depression, and childhood-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders: Is expressed emotion a nonspecific correlate of child psychopathology or a specific risk factor for depression? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1994;22:129–146. doi: 10.1007/BF02167896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow J, Tompson M, Woo S, Cantwell DP. Is expressed emotion a specific risk factor for depression or a nonspecific correlate of psychopathology? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:573–583. doi: 10.1023/a:1012237411007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardone AM, Moffitt T, Caspi A, Dickson N. Adult mental health and social outcomes of adolescent girls with depression and conduct disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:811–829. [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR, Gladstone TR. Prevention of childhood depression: Recent findings and future prospects. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49:1101–1110. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Bridge JA, Williamson DE, Brent DA, Dahl RE, Axelson DA, Dorn LD, Ryan ND. Psychosocial functioning in youths at high risk to develop major depressive disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:839–846. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000128787.88201.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Dahl RE, Williamson DE, Perel JM, Brent DA, Axelson DA, Kaufman J, Dorn LD, Stull S, Rao U, Ryan ND. Growth hormone secretion in children and adolescents at high risk for major depressive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:867–872. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.9.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, Brent DA. Childhood and adolescent depression: A review of the past 10 years, part I. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:1427–1439. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199611000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton C, Calam R, Barrowclough C, Peters S, Roberts J, Wearden A, Morris J. Expressed emotion, attributions and depression in mothers of children with problem behaviour. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 2003;44:242–254. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butzlaff RL, Hooley JM. Expressed emotion and psychiatric relapse. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:547–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers WJ, Puig-Antich J, Hirsch M, Paez P, Ambrosini PJ, Tabrizi MA, Davies M. The assessment of affective disorders in children and adolescents by semistructured interview: Test-retest reliability of the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children, present episode version. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985;42:696–702. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790300064008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. The development of depression in children and adolescents. American Psychologist. 1998;53:221–241. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976;85:186–193. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Coyne JC. Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:50–76. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, Keller MB, Kupfer DJ, Lavori PW, Rush AJ, Weissman MM. Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder: Remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:851–855. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810330075011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Burge D, Stansbury K. Relationship of mother and child variables to child outcomes in a high-risk sample: A causal modeling analysis. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Martin B. Family factors and psychopathology in children. In: Quay HC, Werry JS, editors. Psychopathological disorders of childhood. 3rd. New York: Wiley and Sons; 1986. pp. 332–390. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld DR, Biederman J, Brody L, Faraone SV. Associations between expressed emotion and child behavioral inhibition and psychopathology: A pilot study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:205–213. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199702000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarty GE, Anderson CM, Reiss DJ, Kornblith SJ, Greenwald DP, Javna CD, Madonia MJ. Family psychoeducation, social skills training, and maintenance chemotherapy in the aftercare treatment of schizophrenia: I. One-year effects of a controlled study on relapse and expressed emotion. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43:633–642. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800070019003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status. Yale University Sociology Department; New Haven: 1975. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Orley J, Teasdale JD. Levels of expressed emotion and relapse in depressed patients. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;148:642–647. doi: 10.1192/bjp.148.6.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Richters JE. Expressed emotion: A developmental perspective. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Emotion, cognition, and representation. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1995. pp. 133–166. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen T, Hibbs E, Ziegenhain U. Maternal expressed emotion related to attachment disorganization in early childhood: A preliminary report. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 2000;41:899–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow NJ, Deering CG, Racusin GR. Depressed children and their families. Clinical Psychology Review. 1994;14:39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershner JG, Cohen NJ, Coyne JC. Expressed emotion in families of clinically referred and nonreferred children: Toward a further understanding of the expressed emotion index. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Magana-Amato A. Manual for coding expressed emotion from the five-minute speech sample. Los Angeles: UCLA Family Project; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Magana AB, Goldstein MJ, Karno M, Miklowitz DJ, Jenkins J, Falloon IR. A brief method for assessing expressed emotion in relatives of psychiatric patients. Psychiatry Research. 1986;17:203–212. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(86)90049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty CA, Lau AS, Valeri SM, Weisz JR. Parent-child interactions in relation to critical and emotionally overinvolved expressed emotion (EE): Is EE a proxy for behavior? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:83–93. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000007582.61879.6f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty CA, Weisz JR. Correlates of expressed emotion in mothers of clinically-referred youth: An examination of the five-minute speech sample. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 2002;43:759–768. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleary L, Sanford M. Parental expressed emotion in depressed adolescents: Prediction of clinical course and relationship to comorbid disorders and social functioning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:587–595. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer SC, Gross AM. Childhood depression and family interaction: A naturalistic observation study. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1995;24:77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ. The role of family systems in severe and recurrent psychiatric disorders: A developmental psychopathology view. Development & Psychopathology. 2004;16:667–688. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404004729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR. The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development. 2007;16:361–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H, Puig-Antich J, Chambers WJ, Tabrizi MA, Johnson R. Retrospective assessment of child psychopathology with the K-SADS-E. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1982;21:392–397. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60944-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. A social learning approach: Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castalia; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, DeBaryshe BD, Ramsey E. A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychologist. 1989;44:329–335. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peris TS, Baker BL. Applications of the expressed emotion construct to young children with externalizing behavior: Stability and prediction over time. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 2000;41:457–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig-Antich J, Kaufman J, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, Dahl RE, Lukens E, Todak G, Ambrosini P, Rabinovich H, Nelson B. The psychosocial functioning and family environment of depressed adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:244–253. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199303000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig-Antich J, Lukens E, Davies M, Goetz D, Brennan-Quattrock J, Todak G. Psychosocial functioning in prepubertal major depressive disorders. I. Interpersonal relationships during the depressive episode. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985a;42:500–507. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790280082008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig-Antich J, Lukens E, Davies M, Goetz D, Brennan-Quattrock J, Todak G. Psychosocial functioning in prepubertal major depressive disorders. II. Interpersonal relationships after sustained recovery from affective episode. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985b;42:511–517. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790280093010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Are adolescents changed by an episode of major depression? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1994;33:1289–1298. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199411000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A. Transactional models in early social relations. Human Development. 1975;18:65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CE, Dorer DJ, Beardslee WR, Lavori PW, Keller MB. Maternal expressed emotion and parental affective disorder: Risk for childhood depressive disorder, substance abuse, or conduct disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1990;24:231–250. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(90)90013-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber L, Hyman H, Davis B. Family processes in adolescent depression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2001;4:19–35. doi: 10.1023/a:1009524626436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber L, Sorensen E. Family relationships of depressed adolescents: A multimethod assessment. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27:268–277. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2703_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB. User's guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R: SCID. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Stark KD, Humphrey LL, Crook K, Lewis K. Perceived family environments of depressed and anxious children: Child's and maternal figure's perspectives. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1990;18:527–547. doi: 10.1007/BF00911106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein D, Williamson DE, Birmaher B, Brent DA, Kaufman J, Dahl RE, Perel JM, Ryan ND. Parent-child bonding and family functioning in depressed children and children at high risk and low risk for future depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:1387–1395. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200011000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbe DE, Zahner GE, Goldstein MJ, Leckman JF. Diagnostic specificity of a brief measure of expressed emotion: A community study of children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1993;34:139–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarrier N, Barrowclough C, Vaughn C, Bamrah J, Porceddu K, Watts S, Freeman H. The community management of schizophrenia: A controlled trial of a behavioural intervention with families to reduce relapse. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;153:532–542. doi: 10.1192/bjp.153.4.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vostanis P, Nicholls J. Nine-month changes of maternal expressed emotion in conduct and emotional disorders of childhood: A follow-up study. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 1995;36:833–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wamboldt FS, O'Connor SL, Wamboldt MZ, Gavin LA, Klinnert MD. The five minute speech sample in children with asthma: Deconstructing the construct of expressed emotion. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 2000;41:887–898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Merikangas KR, John K, Wickramaratne P, Prusoff BA, Kidd KK. Family-genetic studies of psychiatric disorders: Developing technologies. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43:1104–1116. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800110090012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wolk S, Goldstein RB, Moreau D, Adams P, Greenwald S, Klier CM, Ryan ND, Dahl RE, Wickramaratne P. Depressed adolescents grown up. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281:1707–1713. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.18.1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]