Abstract

Mechanistic models for biochemical systems are frequently proposed from structural data. Site-directed mutagenesis can be used to test the importance of proposed functional sites, but these data do not necessarily indicate how these sites contribute to function. Herein we apply an alternative approach to the catalytic mechanism of alkaline phosphatase (AP), a widely-studied, prototypical bimetallo enzyme. A third metal ion site in AP has been suggested to provide general base catalysis, but comparison with an evolutionarily-related enzyme casts doubt on this model. Removal of this metal site from AP has large differential effects on reactions of cognate and promiscuous substrates, and the results are inconsistent with general base catalysis. Instead, these and additional results suggest that the third metal ion stabilizes the transferred phosphoryl group in the transition state. These results establish a new mechanistic model for this prototypical bimetallo enzyme and demonstrate the power of a comparative approach for probing biochemical function.

Keywords: Alkaline phosphatase, enzyme, mechanism, evolution

Introduction

Understanding the link between molecular structure and biological function is a central goal of modern biochemistry. Over the last two decades an explosion of structural data has led to deep insights into the mechanisms of fundamental biological processes. Mechanistic models proposed from such structures are often tested by site-directed mutagenesis, with detrimental effects on activity indicating that the mutated sites are functionally significant. There is a major limitation to this approach, however, because mutagenesis data that implies functional significance does not necessarily demonstrate how a given site contributes to function.

Alkaline phosphatase (AP) is one of the best-studied enzymes and serves as a prototype for a wide variety of enzymes that use two metal ions to catalyze phosphoryl transfer reactions.1–4 In AP-catalyzed phosphate monoester hydrolysis, two active site Zn2+ ions coordinate the nucleophile and leaving group, respectively, and a nonbridging oxygen atom of the transferred phosphoryl group is coordinated between the two Zn2+ ions (Fig. 1). A third metal ion site near the bimetallo site contains a Mg2+ ion, and it has been suggested that a Mg2+-bound hydroxide ion acts as a general base to deprotonate the Ser nucleophile (Fig. 2a).2, 5 This model was proposed based on inspection of X-ray crystal structures and has been widely accepted in the literature.6–12 Mutagenesis of the Mg2+ ligands has large detrimental effects on phosphate monoester hydrolysis,13, 14 suggesting that the Mg2+ site is functionally significant, but this outcome is consistent with any model for the contribution of the Mg2+ site to catalysis and does not specifically support the general base model. Indeed, alternative models for the contribution of the Mg2+ site have been proposed, as discussed below,15 and further functional studies are necessary to resolve this ambiguity and to dissect catalysis and specificity in bimetallo enzymes.

Figure 1.

Active site schematics for AP and NPP highlight similarities and differences between these AP superfamily members.2, 15, 36 Functional groups unique to AP are colored blue, and functional groups unique to NPP are colored green. Conserved functional groups are colored black. The phosphate ester substrates are depicted in terms of a transition state representation with partial bond formation and bond cleavage. No information about bond orders and bond lengths is implied.

Figure 2.

Models for the role of the Mg2+ site in catalysis. (a) A Mg2+-bound hydroxide ion acts as a general base to activate the Ser nucleophile. (b) The Mg2+ ion stabilizes the transferred phosphoryl group via its contact to the bimetallo Zn2+ site. (c) The Mg2+ ion stabilizes the transferred phosphoryl group via a water ligand. Each of these models predicts that mutations at the Mg2+ site will have a detrimental effect on phosphate monoester hydrolysis.

Functional studies of biochemical systems frequently take advantage of comparisons between wild type and mutant proteins, between different types of substrates, and between evolutionarily-related proteins. The relatively recent realization that protein families can be grouped into evolutionarily-related superfamilies16 and that many enzymes have the ability to promiscuously catalyze the reactions of their evolutionary relatives17–19 provides powerful, new opportunities to test mechanistic models using all three types of comparisons in a single system. Structural comparisons of evolutionarily-related enzymes can be used to identify the active site features that allow similar enzymes to catalyze different reactions; mutagenesis studies can test the functional significance of these active site groups; and comparisons of the reactivity of different types of substrates in the same active site can be used to test models for how the different structural features contribute to catalysis of distinct reactions.

Recent studies of evolutionarily-related enzymes in the AP superfamily provide an opportunity to test mechanistic models with this comparative approach. AP preferentially hydrolyzes phosphate monoesters and also has a low level of activity for phosphate diester hydrolysis.20 In contrast, an evolutionarily-related member of the AP superfamily, nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase (NPP), uses a structurally indistinguishable bimetallo site (Fig. 1) but preferentially hydrolyzes phosphate diesters.15 The preferences of AP and NPP for phosphate monoester and diester substrates are reversed by ~1015-fold,15, 20 raising the question of what active site features provide specificity for different reactions and how they contribute to catalysis.

A prominent difference between AP and NPP is the presence of a Mg2+ site in AP that is absent in NPP (Fig. 1).15 The Mg2+ site is conserved in AP orthologues across a wide range of bacterial and eukaryotic species,1, 21 and the residues that occupy the corresponding site in NPP are similarly widely conserved.15 If the Mg2+ site contributes to general base catalysis in AP-catalyzed phosphate monoester hydrolysis,2, 5 the simplest expectation is that a general base would also be important for NPP-catalyzed phosphate diester hydrolysis. The absence of the Mg2+ site in NPP, and the lack of any other candidate general base in NPP, prompted us to reexamine the contribution of the Mg2+ site to specificity and catalysis in AP. The results provide evidence against a general base model and instead suggest the importance of additional catalytic interactions beyond the bimetallo core, demonstrating and exemplifying the power of these multi-faceted comparisons for understanding the relationship between structure and function within an enzyme active site.

Results

The specificity difference between AP and NPP

To determine how the Mg2+ site of AP (Fig. 1) affects both phosphate monoester and diester hydrolysis, we undertook a combined structural and functional study motivated by comparisons between the evolutionarily related enzymes AP and NPP. The comparisons described below are based on differences in values of kcat/KM, and these differences determine the specificity between two competing substrates†.27

The overall specificity difference between phosphate monoester and diester reactions in AP and NPP is >1012-fold. This specificity difference is based on the preference of AP for the monoester p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP2−) over the simple diester methyl-p-nitrophenyl phosphate (MpNPP−) (Scheme 1), and the preference of NPP for its preferred diester substrate thymidine-5′-monophosphate-p-nitrophenyl ester over the monoester pNPP2− (see Supplementary Discussion for comparison to the previously reported value of 1015-fold obtained using bis-p-nitrophenyl phosphate (bis-pNPP−) as the model diester substrate for AP).15 Previous structural and functional comparisons of AP and NPP identified functional groups distinct from the bimetallo Zn2+ site that are responsible for about half of the difference in specificity. In AP, Arg166 contributes to preferential monoester hydrolysis by directly interacting with two charged nonbridging oxygen atoms of phosphate monoester substrates (Fig. 1).20, 28 In NPP, a hydrophobic pocket contributes to preferential diester hydrolysis by providing specific binding interactions to the second ester functional group (henceforth referred to as the R′ group) on diester substrates (Fig. 1).15

Scheme 1.

After accounting for the contributions of Arg166 and the R′ binding site, a 4 × 107-fold difference in specificity remains. This difference reflects the preference of R166S AP for pNPP2−relative to MpNPP− (2 × 105-fold) and the preference of NPP for MpNPP− relative to pNPP2− (2 × 102-fold). To determine if the Mg2+ site in AP is responsible for any of the remaining specificity difference, we have removed the Mg2+ site from AP and analyzed the effects on monoester and diester hydrolysis reactions.

Removal of the Mg2+ site in AP

Three AP side chains and three water molecules coordinate the Mg2+ ion in an octahedral geometry (Fig. 3a).15 One of the protein ligands, Asp51, is also a Zn2+ ligand and corresponds to Asp54 in NPP. Another of the protein ligands, Thr155, is the ninth residue in a stretch of 54 residues that has no structural homology to NPP. The remaining protein ligand, Glu322, is structurally homologous to Tyr205 in NPP.15 In NPP, Tyr205 occupies the region corresponding to the Mg2+ site and forms a hydrogen bond with Asp54 (Fig. 3b). We therefore prepared a mutant of AP with Glu322 mutated to Tyr (E322Y AP) with the prediction that the Mg2+ ion would be displaced by the Tyr hydroxyl group.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the Mg2+ site of AP with the corresponding region of NPP in structures with a phosphoryl group bound in the active site. (a) The Mg2+ site in AP with inorganic phosphate bound in the active site (pdb entry 1ALK).2 Thr155, Glu322, Asp51, and three water molecules (blue spheres) coordinate Mg2+ in an octahedral geometry. Asp51 is also a Zn2+ ligand (see Figure 1). One of the Mg2+-bound water molecules is positioned to contact an oxygen atom in the phosphate ligand. (b) The corresponding region of NPP with the phosphoryl group of AMP bound in the active site (pdb entry 2GSU).15 Tyr205 occupies the region corresponding to the Mg2+ site in NPP and forms a hydrogen bond with Asp54. Asp54 is a Zn2+ ligand in NPP and corresponds to Asp51 in AP. Tyr205 of NPP and Glu322 of AP are structural homologous. (c) The structure of E322Y AP in complex with inorganic phosphate (pdb entry 3DYC). The tyrosine residue displaces the Mg2+ ion and contacts Asp51 in a manner analogous to the corresponding site in NPP. (d) Overlay of wt (gray) and E322Y (transparent) AP.

To assess the structural consequences of the Tyr mutation, we determined the X-ray crystal structure of E322Y AP complexed with inorganic phosphate. As expected, the hydroxyl group of Tyr322 occupies the region corresponding to the Mg2+ site in wt AP and is positioned to form a hydrogen bond with Asp51 (Fig. 3c, d), analogous to the hydrogen bond between Tyr205 and Asp54 in NPP. The aromatic ring of Tyr322 in E322Y AP is rotated ~25° with respect to Tyr205 in NPP. The bimetallo Zn2+ site of AP is largely unaffected by the E322Y mutation. The carboxylate group of Asp51 in E322Y AP is rotated ~15° with respect to Asp51 in wt AP, but there are no significant structural changes elsewhere in the active site. In particular, the Zn2+–Zn2+ distance is not significantly altered by the replacement of the Mg2+ ion with the Tyr residue (Supplementary Fig. 1). Thus, mutation of Glu322 to Tyr in AP produces an active site that lacks the Mg2+ ion and is structurally homologous to the active site of NPP.

To confirm that the Mg2+ ion is absent from E322Y AP in solution, we determined the metal ion content by atomic emission spectroscopy (see Methods). Control experiments with wt AP gave the expected stoichiometry of two Zn2+ ions and one Mg2+ ion for each AP monomer. E322Y AP contained the expected two Zn2+ ions per AP monomer, and no Mg2+ ions were detected (Table 1). Together with the crystal structure, these data show that E322Y AP does not contain a bound Mg2+ ion.

Table 1.

Metal Ion and Phosphorus Content of Wt and E322Y APa

| Zn:protein | Mg:protein | P:protein | |

|---|---|---|---|

| wt APb | 2.25 | 0.91 | 0.92 |

| E322Y AP (after Zn incubation)c | 2.23 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| E322Y AP (before Zn incubation)c | 1.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Estimated errorsd | ±0.18 | ±0.06 | ±0.13 |

| Detection limitsd | ≤0.1 | ≤0.05 | ≤0.1 |

Metal ion and phosphorus content were determined as described in the Methods section. Protein content in each sample was determined from sulfur content, using 12 sulfur atoms per AP monomer to convert to protein content. The wavelengths used for AES detection were 213.8 nm (Zn), 280.2 nm (Mg), 213.6 nm (P), and 180.7 nm (S).

Wt AP was dialyzed as described in the Methods section with 10 μM ZnCl2 and 10 μM MgCl2.

E322Y AP (after Zn incubation) was incubated in a ZnCl2 solution for >5 days as described in the Methods section. E322Y AP (before Zn incubation) was not subjected to this incubation. E322Y AP samples were then dialyzed as described in the Methods section with 10 μM ZnCl2. Control samples with additional 10 μM MgCl2 gave identical results within error, and addition of 1 mM MgCl2 had no effect on activity.

The estimated errors were obtained from independent repeat measurements. The estimated errors and detection limits in absolute metal and phosphorus content were scaled by the protein content (typically ~2.5 μM in a 4 mL sample) for comparison to the ratios reported above.

Removal of Mg2+ has a large effect on phosphate monoester reactions

Removal of the Mg2+ site from AP has a large detrimental effect on the rate of phosphate monoester hydrolysis. The value of kcat/KM of 7.2 × 103 M−1 s−1 for the reaction of E322Y AP with pNPP2− is 5 × 103-fold smaller than the value for wt AP (Table 2). This effect is consistent with previous reports of large decreases in activity with pNPP2− upon mutation of Mg2+ ligands.13, 14 The 5 × 103-fold decrease is a lower limit for the full effect of removal of the Mg2+ site because the reaction of wt AP with pNPP2− is not limited by the chemical step.24–26 To assess the full effect, we measured rate constants for the reaction of E322Y AP with two alkyl phosphates, m-nitrobenzyl phosphate (mNBP2−) and methyl phosphate (MeP2−) (Scheme 1). The reactions of these substrates with wt AP are limited completely (for MeP2−) or partially (for mNBP2−) by the chemical step.25, 29 The values of kcat/KM for E322Y AP-catalyzed mNBP2− and MeP2− hydrolysis are 6 × 105-fold and 7 × 105-fold slower than those for wt AP respectively (Table 2), much larger effects than observed with pNPP2−.

Table 2.

Values of kcat/KM (M−1 s−1) for AP-catalyzed reactionsa

| Substrate | wt AP | E322Y | E322A | R166S | R166S/E322Y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphate Monoesters | |||||

| pNPP2− | 3.3 × 107 | 7.2 × 103 | 8.9 × 103 | 1.0 × 105 | 1.6 |

| mNBP2− | 1.8 × 107 | 31 | n.d.c | 2.3 × 103 | ≤0.02 |

| MeP2− | 1.2 × 106 | 1.6 | n.d.c | 1.1 × 102 | n.d.c |

| Phosphate Diesters | |||||

| MpNPP1− | 18 | 35 | 18 | 0.48 | 0.24 |

| bis-pNPP1− | 5.0 × 10−2 | 7.0 × 10−2 | 3.7 × 10−2 | 5.0 × 10−2 | 2.1 × 10−2 |

| Sulfate Monoesters | |||||

| pNPS1− | 1.0 × 10−2 | 2.9 × 10−6 | n.d.c | 5.8 × 10−5 | ≤10−6 |

|

| |||||

| krel (monoester/diester)b | 3.7 × 106 | 2.1 × 102 | 4.9 × 102 | 2.1 × 105 | 6.7 |

Rate constants were measured in 0.1 M NaMOPS, pH 8.0, 0.5 M NaCl, and varying amounts of Mg2+ and Zn2+ salts as necessary for full enzyme activity (always ≤ 1 mM) at 25 °C. Rate constants for wt and R166S AP are from previous work20, 22, 23, 25, 29, 33 (J. Lassila and D.H., submitted), except that for the reaction of wt AP with MpNPP1− which was obtained herein. The uncertainties for the values of kcat/KM, defined as the standard deviations for repeated measurements, are within ±30%.

krel is the ratio of the rate constants for monoesterase (pNPP2−) and diesterase (MpNPP1−) activity [krel=(kcat/KM)pNPP2−/(kcat/KM)MpNPP−].

n.d. not determined.

To test for energetic cooperativity between the Mg2+ site and Arg166, which also has a large effect on monoesterase activity, we prepared the double mutant R166S/E322Y. Large decreases in phosphate monoesterase activity were observed upon mutation of Glu322 to Tyr in the background of R166S AP. The value of kcat/KM for R166S/E322Y AP-catalyzed pNPP2− hydrolysis was 6 × 104-fold smaller than that for R166S AP (Table 2). For the reaction of R166S/E322Y AP with mNBP2−, only an upper limit for the value of kcat/KM could be determined due to the presence of a slight contaminating activity in the enzyme preparation (see Methods). Using this upper limit, the value of kcat/KM for R166S/E322Y AP-catalyzed mNBP2− hydrolysis was ≥1 × 105-fold smaller than that for R166S AP (Table 2). The limit observed for R166S/E322Y AP relative to R166S AP with mNBP2− as a substrate (≥1 × 105-fold) is similar to the decrease observed for E322Y AP relative to wt AP (6 × 105-fold), suggesting that there is little or no cooperativity between Arg166 and the Mg2+ site in their contributions to catalysis. This result is consistent with the observation that the position of Arg166 is unperturbed in the structure of E322Y AP relative to wt AP.

Although removal of the Mg2+ site from AP has large detrimental effects on phosphate monoester hydrolysis, the physical basis for how the Mg2+ site contributes to catalysis is not obvious. A Mg2+-bound hydroxide ion could serve as a general base, as suggested previously2, 5 (Fig. 2a). Alternatively, the Mg2+ ion could interact with and stabilize the transferred phosphoryl group, either through the bimetallo Zn2+ site via its contact with Asp51 (Fig. 2b) or through a coordinated water ligand (Fig. 2c). In any of these cases, removal of the Mg2+ ion would have a detrimental effect on phosphate monoester hydrolysis. To provide further insight into the role of the Mg2+ site in catalysis, we measured rate constants for E322Y AP-catalyzed reactions with phosphate diesters and sulfate monoesters, substrates that are proficiently hydrolyzed by other members of the AP superfamily.30, 31 The subtle structural differences between these substrates and phosphate monoesters provide a means to incisively assess different models for how active site functional groups contribute to catalysis.

Removal of Mg2+ has no significant effect on phosphate diester reactions

Remarkably, given its large detrimental effect on phosphate monoester hydrolysis, removal of the Mg2+ site from AP has no significant effect on phosphate diester hydrolysis. The values of kcat/KM for the reactions of E322Y AP with the diesters MpNPP− and bis-pNPP−(Scheme 1) are within 2-fold of the values for wt AP (Table 2). Similarly, the values of kcat/KM for the reactions of R166S/E322Y AP with MpNPP− and bis-pNPP− are only 2–3-fold slower than the values for R166S AP (Table 2). Whenever rate constants for cognate and promiscuous reactions are compared, control experiments are necessary to confirm that the observed reaction of the promiscuous substrate arises from the same active site that catalyzes the cognate reaction, and not from a small amount of a proficient contaminating enzyme. Identical inhibition of the monoesterase and diesterase activities by inorganic phosphate confirmed that these reactions occurred in the same active site for both E322Y and R166S/E322Y AP (Supplementary Fig. 4).

The small effects on diesterase activity observed upon removal of the Mg2+ site in AP can be rationalized in terms of the ability of the related enzyme NPP to proficiently hydrolyze phosphate diesters using an active site similar to AP but lacking a Mg2+ site (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, the differential effect on monoesters and diesters is striking: removal of the Mg2+ site from AP has effects of up to 106-fold on phosphate monoester hydrolysis but an effect of only ~2-fold on diester hydrolysis.

To determine if the presence of the Tyr residue at position 322 is important for maintaining diesterase activity after the Mg2+ ion has been removed, we also prepared E322A AP. The rate constants for E322A AP-catalyzed hydrolysis of pNPP2−, MpNPP−, and bis-pNPP−are all within 2-fold of the rate constants for the corresponding E322Y AP-catalyzed reactions (Table 2), suggesting that the observed effects arise entirely due to the absence of the Mg2+ site and not from the presence of the Tyr residue in its place. The small differences in reactivity between Tyr and Ala at position 322 in AP are similar to the small effects observed upon mutation of NPP Tyr205 to Ala (J.G.Z. and D.H., unpublished results).

The observation that removal of the Mg2+ site has a large detrimental effect on phosphate monoester hydrolysis, but no significant effect on phosphate diester hydrolysis, provides strong evidence against the model in which a Mg2+-bound hydroxide ion serves as a general base (Fig. 2a), as activation of the Ser nucleophile would be expected to be important for both phosphate monoester and diester hydrolysis reactions, which proceed with concerted nucleophilic attack and departure of the leaving group‡.12 Indeed, if general base catalysis were operative, a larger detrimental effect on would be expected for phosphate diesters because nucleophilic participation in the transition state is greater for phosphate diesters than monoesters.12, 32

Two plausible models remain for the role of the Mg2+ site in catalysis, and each is consistent with the observed effects on phosphate monoester and diester reactions. First, the Mg2+ ion could contribute positive charge to the bimetallo Zn2+ site through its contact with Asp51 (Fig. 2b), which could provide a preference for the more highly negatively charged substrates like phosphate monoesters relative to phosphate diesters (Scheme 1). Alternatively, as a Mg2+-bound water molecule appears to interact with a charged, nonbridging oxygen atom of phosphate monoester substrates, the loss of this interaction could be responsible for the substantial decrease in phosphate monoesterase activity upon removal of the Mg2+ site (Fig. 2c). The small effects of removal of the Mg2+ site on diester hydrolysis could then be explained if the uncharged oxygen atom (bearing the R′ group) is oriented toward the Mg2+ site (Fig. 4a). These two models can be distinguished by their predictions for sulfate monoester hydrolysis; the orientation of the R′ group is addressed later.

Figure 4.

Possible orientations of the diester R′ group in the AP active site. (a) The diester R′ group is oriented toward the Mg2+ site. (b) The diester R′ group is oriented away from the Mg2+ site.

Removal of Mg2+ has a large effect on sulfate monoester reactions

Wt AP has a low level of sulfatase activity, with a kcat/KM of 10−2 M−1 s−1 (Table 2) for hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl sulfate (pNPS−, Scheme 1).23 Removal of the Mg2+ site from AP has a large detrimental effect on sulfatase activity (Fig. 5). The value of kcat/KM for the reaction of E322Y AP with pNPS− of 2.9 × 10−6 M−1 s−1 is 3 × 103-fold smaller than the value for wt AP (Table 2). Inorganic phosphate inhibition of the observed sulfatase activity of E322Y AP confirmed that the same E322Y AP active site catalyzes phosphate monoester, phosphate diester, and sulfate monoester hydrolysis (Supplementary Fig. 5). The value of kcat/KM for R166S/E322Y AP was below detection limits (≤10−6 M−1 s−1) and is therefore at least 102-fold slower than that for R166S AP (Table 2).

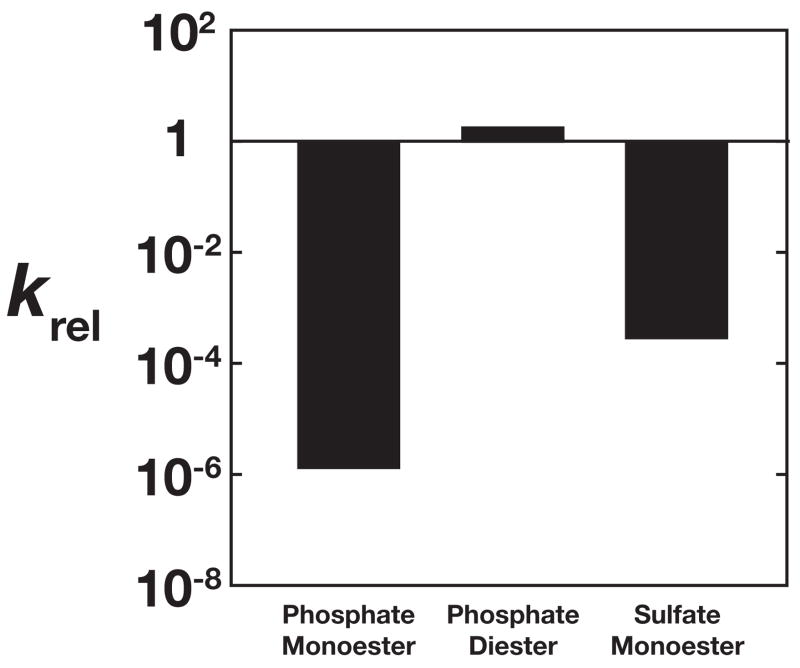

Figure 5.

Effects of removal of the Mg2+ site on different reactions. krel is the ratio of (kcat/KM)E322Y AP to (kcat/KM)wt AP (Table 2). The phosphate monoester, diester, and sulfate monoester substrates used for comparison were MeP2−, MpNPP−, and pNPS− (Scheme 1). Removal of the Mg2+ site has large detrimental effects on phosphate and sulfate monoester hydrolysis and no significant effect on phosphate diester hydrolysis.

The observed ~103-fold decrease in sulfatase activity from wt to E322Y AP is large but significantly smaller than the decrease of ~106-fold observed for phosphate monoester substrates (Fig. 5). Previous studies have demonstrated that removal of AP active site functional groups can have a differential effect on phosphate and sulfate ester reactions. In particular, removal of Arg166 has a 104-fold effect on phosphate monoester hydrolysis and a 102-fold effect on sulfate monoester hydrolysis.33, 34 This difference presumably arises because arginine interacts more strongly with the highly charged nonbridging oxygen atoms of a phosphate monoester (Fig. 1) than the less charged sulfate ester. Similarly, removal of the Mg2+ site and its associated interactions with the substrate, mediated either through space via electrostatic effects or through a hydrogen bond with a coordinated water molecule, would be predicted to have a larger effect on phosphate esters than sulfate esters stemming from differences in total charge on the substrate.

The observation that removal of the Mg2+ site has a large detrimental effect on sulfate monoester hydrolysis is not consistent with a model in which the Mg2+ contributes to catalysis by modulating the properties of the bimetallo Zn2+ site (Fig. 2b). This model predicts that removal of the Mg2+ site would have no significant effect on sulfate monoesters, similar to that observed for phosphate diesters, because the amount of negative charge situated between the two Zn2+ ions is even less for sulfate monoesters than for phosphate diesters.35 Instead, removal of the Mg2+ site has substantial effect on sulfate monoester hydrolysis (Fig. 5), consistent with a model in which the interaction between a Mg2+-bound water molecule and a charged, nonbridging oxygen makes an important contribution to catalysis for phosphate and sulfate monoester substrates (Fig. 2c).

If the Mg2+ site contributes to catalysis by stabilizing a charged, nonbridging oxygen (Fig. 2c), then the small effects of the Mg2+ site on diester hydrolysis can only be rationalized if the uncharged oxygen atom (bearing the R′ group) of the diester substrate is oriented toward the Mg2+ site, as alluded to above (Fig. 4a). If the phosphate diester substrate positions a charged oxygen atom toward the Mg2+ site (Fig. 4b), then a large detrimental effect would be expected upon removal of the Mg2+ site, but such an effect is not observed. Therefore, the observed data suggests that the R′ group of diester substrates is oriented toward the Mg2+ site in AP. To test this prediction, we used a thio-substituted phosphate diester to independently determine the orientation of the R′ group in the AP active site.

Thio-effects and the orientation of the R′ group

Phosphorothioates are analogs of phosphate esters with a single sulfur substitution at a nonbridging position (Scheme 1), and the chirality of phosphorothioate diesters provides a means to assess the orientation of the R′ group in the AP active site. The two enantiomers of MpNPPS− (Fig. 6a) are expected to bind the AP active site in different orientations. The sulfur atom is unlikely to bind between the two Zn2+ ions29 (J. Lassila and D.H., submitted), so each enantiomer of MpNPPS− would have only one remaining possible orientation in the AP active site. The RP-enantiomer would orient the R′ (methyl) group toward the Mg2+ site and the sulfur atom toward the backbone amide (Fig. 6b); the SP-enantiomer would bind with its substituents in the opposite orientation.

Figure 6.

AP-catalyzed phosphorothioate diester hydrolysis is stereoselective. (a) Enantiomers of the phosphorothioate diester MpNPPS− (Scheme 1). (b) Only RP-MpNPPS- is detectably hydrolyzed by AP, suggesting that the R′ group is oriented towards the Mg2+ site.

Previous work demonstrated that NPP reacts solely with the RP-enantiomer (J. Lassila and D.H., submitted), which allows a simple experiment to determine if AP prefers a specific enantiomer of MpNPPS−. NPP was used to react the Rp-MpNPPS- enantiomer to completion from a racemic mixture, allowing the unreacted SP-MpNPPS- to be isolated and purified (see Methods). AP reacts with racemic MpNPPS− (Supplementary Table 1), but no reaction of AP was detectable with purified SP-MpNPPS-, and addition of non-thio-substituted substrates to the reactions confirmed that the enzyme was fully active in the reaction conditions after incubation with MpNPPS−. The data provide a limit that AP reacts with the RP-enantiomer at least 102-fold faster than with the SP-enantiomer, suggesting that MpNPPS- preferentially binds in the AP active site with the R′ (methyl) group toward the Mg2+ site and the sulfur atom toward the backbone amide (Fig. 6b). This result is consistent with the expectation from the reactivity comparisons of phosphate monoesters, phosphate diesters, and sulfate monoesters described above, which independently suggested that diesters orient the R′ group toward the Mg2+ site.

Additional confirmation that the R′ group is oriented towards the Mg2+ site comes from comparison of the rate constants for AP-catalyzed reactions of phosphorothioate substrates in the presence and absence of the Mg2+ site. The effects of removal of the Mg2+ site on the phosphorothioate ester substrates are similar to the effects on their corresponding phosphate ester substrate analogs (Supplementary Table 1). Therefore, sulfur substitution does not significantly affect the active site interactions mediated by the Mg2+ site. This result suggests, most simply, that the sulfur atom is oriented away from the Mg2+ site and that the R′ group of the phosphorothioate diester is oriented toward the Mg2+ site.

Discussion

Role of the Mg2+ site in catalysis

Removal of the Mg2+ site from wt or R166S AP has a substantial detrimental effect on both phosphate and sulfate monoester hydrolysis, but not on phosphate diester hydrolysis (Fig. 5). The similarities and differences between these substrates, both in their total charges and in the distribution of charge on the transferred phosphoryl or sulfuryl group, allow dissection of how the Mg2+ site contributes to catalysis. The observation that removal of the Mg2+ site has a large effect on monoester hydrolysis but no significant effect on diester hydrolysis strongly suggests that the Mg2+ site does not mediate general base catalysis as previously proposed (Fig. 2a),2, 5 as activation of the nucleophile would be expected to be important for both phosphate monoester and diester reactions, and indeed more important for phosphate diesters than phosphate monoesters due to the greater nucleophilic participation in the diester transition state.12, 32 Instead, the simplest model that accounts for the existing functional and structural data is that the Ser nucleophile is present as a Zn2+-coordinated alkoxide (Fig. 1).25 In this case, a general base would not be necessary to activate the Ser nucleophile.

An alternative model for the contribution of the Mg2+ site to catalysis was proposed based on the observation that reactivity in AP decreases in the order phosphate monoester > phosphate diester > sulfate monoester.20, 23 This reactivity order corresponds to the amount of negative charge per nonbridging oxygen atom on each of these substrates: largest for phosphate monoesters, intermediate for phosphate diesters, and smallest for sulfate monoesters.35 The preference for more negatively charged substrates like phosphate monoesters was suggested to arise from interactions of the bimetallo Zn2+ site with a nonbridging oxygen atom.35 The Mg2+ ion could contribute to this preference by providing additional positive charge to the bimetallo site indirectly via its interaction with Asp51 (Fig. 2b).15 This model, in its simplest form, predicts that removal of the Mg2+ site would have the largest detrimental effect on phosphate monoester hydrolysis, a smaller effect on phosphate diester hydrolysis, and the smallest effect on sulfate monoester hydrolysis. However, removal of the Mg2+ site had a far larger effect on sulfate monoester hydrolysis than on phosphate diester hydrolysis (Fig. 5), suggesting that the Mg2+ site contributes to catalysis through a different mechanism.

The reactivity comparisons discussed above strongly suggest that the Mg2+ ion contributes to catalysis by interacting with the transferred phosphoryl group indirectly via a coordinated water ligand (Fig. 2c). For phosphate and sulfate monoester substrates, removal of the Mg2+ site eliminates a contact between the Mg2+-bound water and a charged, nonbridging oxygen atom, and the loss of this interaction could be responsible for the large deleterious effects of the E322Y mutation (Fig. 5). For phosphate diester substrates, if the neutral, R′-bearing oxygen atom is oriented toward the Mg2+ site (Fig. 4a), then removal of the Mg2+ site would have no significant effect on phosphate diester hydrolysis. Reactivity comparisons with a chiral thio-substituted diester substrate provided independent evidence that the R′-bearing oxygen atom is oriented toward the Mg2+ site, as only the RP-enantiomer is detectably hydrolyzed by R166S AP (Fig. 6b).

Implications for active site interactions

If the interaction between the Mg2+-bound water and a charged, nonbridging oxygen atom provides a substantial contribution to catalysis for phosphate and sulfate monoesters, why do phosphate diesters fail to take advantage of this interaction? In principle, a diester substrate could orient the R′-bearing oxygen away from the Mg2+ site (Fig. 4b), which would position a charged, nonbridging oxygen atom toward the Mg2+ site and provide a significant contribution to catalysis, analogous to the contribution suggested for monoester substrates. Therefore, there must be some energetic factor that favors orienting the R′-bearing oxygen toward the Mg2+ site and outweighs the potential benefits of orienting the charged oxygen atom toward the Mg2+ site (see Supplementary Information for additional discussion). Steric constraints could dictate the orientation of the R′ group, but there is no indication of such constraints from the structure of AP. Alternatively, specific contacts between the substrate and the enzyme could be responsible for the orientation of the R′-bearing oxygen. In particular, the structure of AP in complex with a vanadate transition state analog36 suggests that the backbone amide of Ser102 donates a hydrogen bond to a substrate oxygen atom in the transition state (Fig. 1). This interaction could contribute to a preference for the diester to orient a charged, nonbridging oxygen atom toward the amide and the R′-bearing oxygen atom toward the Mg2+ site (Fig. 4a). Previous comparisons of AP-catalyzed reactions have focused, perhaps unduly, on the interaction between a nonbridging oxygen atom and the two Zn2+ ions,35 but the results outlined here highlight the importance of active site interactions with all three charged nonbridging oxygen atoms for AP-catalyzed phosphate monoester hydrolysis.

There is ample precedent for the idea that a backbone amide can make a significant contribution to catalysis. Interactions between backbone amides and phosphate monoester nonbridging oxygen atoms are ubiquitous in proteins that bind phosphoryl groups.37 These interactions play a prominent role in the active sites of protein tyrosine phosphatases, where a set of six backbone amides and a single arginine residue make all of the contacts to the nonbridging oxygen atoms.38–40 The prevalence of backbone amides in these systems raises the question of whether the Mg2+ ion provides any additional benefit to catalysis that could not be supplied by a protein functional group. The choice of a Mg2+ ion or a protein functional group could simply be a result of different evolutionary paths, and either option could provide an equivalent selective advantage. Indeed, a protein functional group is present in place of the Mg2+ site in other AP superfamily members that react with phosphate monoester substrates. Cofactor-independent phosphoglycerate mutases (iPGMs) are members of the AP superfamily, and the bimetallo site ligands and the active site nucleophile are conserved between AP and iPGM.30, 31 Instead of a Mg2+ site, however, iPGM contains a lysine residue positioned to contact a nonbridging phosphate ester oxygen atom, analogous to the proposed contact between a Mg2+-bound water molecule and the substrate in AP.41, 42

Energetic consequences of removal of the Mg2+ site

Removal of the Mg2+ site from AP reduces phosphatase activity by up to 7 × 105-fold (Table 2), corresponding to an energetic effect of 8 kcal/mol. This effect is significantly larger than the effects that are typically observed upon mutation of hydrogen bonding groups, which range from 2–5 kcal/mol.43–45 Thus, there may be additional factors that contribute to the observed effects, beyond simply removal of the interaction between the Mg2+ ion and the transferred phosphoryl group. The E322Y mutation could introduce interactions that are destabilizing for phosphate monoester substrates, although this possibility is unlikely given the similar kinetic parameters for E322Y and E322A AP (Table 2). Alternatively, removal of the Mg2+ site could disrupt other interactions that are important for catalysis. An important constraint on this possibility is that the interactions that are disrupted can only contribute to phosphate and sulfate monoester hydrolysis, as removal of the Mg2+ site has no effect on phosphate diester hydrolysis. Further, the large catalytic contribution from Arg166 is essentially independent of the Mg 2+ site contribution (see above).

Overview of the reactivity difference between AP and NPP

The Mg2+ site in AP accounts for ~104-fold of the reactivity difference between AP and NPP (Fig. 7). The total specificity difference between AP and NPP is >1012-fold, and these enzymes are only 8% identical in sequence.15 Yet, after accounting for the contributions of the Mg2+ site, Arg166, and the R′ binding site in NPP, only a 103-fold difference in specificity is left to account for between AP and NPP. Features that could account for this difference remain to be systematically tested.

Figure 7.

Relative reactivity of diester and monoester substrates with NPP and AP. The bar graph shows krel for reactions of different diester substrates with NPP and AP. krel is the ratio of (kcat/KM)diester to (kcat/KM)monoester. Values of kcat/KM are from Table 2 and previous work.15 Several diester substrates with different R′ groups were used, and in all cases, (kcat/KM)monoester refers to the reaction with pNPP2−. NPP reacts faster with diesters than monoesters (blue bars), and krel increases as the size of the diester R′ group increases.15 Wt AP reacts faster with monoesters than diesters, and removal of Arg166 and the Mg2+ site decreases the preference for monoester substrates (red bars; krel for all AP variants is for MpNPP− relative to pNPP2−). The arrows indicate that the fastest reactions at either extreme are not limited by the chemical step (see Supplementary Discussion).

Implications for the two-metal ion mechanism

The “two-metal ion mechanism” is frequently cited as an explanation for the proficient catalysis of phosphoryl transfer reactions by many enzymes including polymerases, nucleases, and ribozymes.3, 4, 46–53 The two metal ions are suggested to be ideally situated to activate the nucleophile and stabilize charge buildup on both the transferred phosphoryl group and the leaving group in the transition state. This model further suggests that the metal ions are responsible for catalysis of the chemical reaction, while the surrounding protein or RNA functional groups simply serve to position the phosphoryl group with respect to the two metal ions.3, 48 Inferences about the role of the two-metal ion motif in catalysis have been based largely on structural studies, and comparative studies of AP and NPP allow the role of the bimetallo site itself in specificity and catalysis to be directly addressed with functional comparisons.

The results described herein and previously15 strongly suggest that the major contributions to the specificity difference between AP and NPP come from functional contacts to the substrate distinct from the bimetallo site, rather than from differences in the properties of the bimetallo site itself. Further, these effects are very large, on the order of 20 kcal/mol for the features that distinguish between AP and NPP (Fig. 7). The functional groups that make important contributions to specificity, and hence to catalysis, include an arginine residue, a binding site for the diester R′ group, and a third metal ion site (Fig. 1). Indirect evidence suggests that the backbone amide of Ser102 also makes an important contribution to catalysis in AP, and a homologous amide is present in NPP (Fig. 1). These types of functional groups contribute to catalysis in many enzymes that lack bimetallo sites. It is thus not surprising that they would also contribute to catalysis in the context of a bimetallo active site. Although enzymatic catalysis is frequently discussed in terms, like the “two-metal ion mechanism”, that imply a single contribution to catalysis, enzymes have long been recognized to use multiple strategies for catalysis,54 and bimetallo enzymes appear to be no exception.

Summary and implications

Comparisons of evolutionary homologues and multiple substrates in the same active site provide a powerful approach for understanding enzymatic catalysis, allowing mechanistic models to be evaluated at a level of detail that would not have been possible from analysis of a single site-directed mutant and its preferred substrate. These approaches have been used to elucidate the role of the Mg2+ site in the AP superfamily, and the results are not consistent with the accepted literature model suggesting that the Mg2+ ion participates in general base catalysis. Instead, the Mg2+ ion stabilizes the transferred phosphoryl group in the transition state, and this interaction is distinct from those mediated by the Zn2+ bimetallo site. The results also suggest that positioning of charged or polar groups to interact with all three nonbridging oxygen atoms of the transferred phosphoryl group is important for catalysis of phosphate monoester hydrolysis. Future functional studies on AP and NPP will further explore the interplay between the metal ions and the surrounding functional groups in catalysis, and the mechanisms underlying the observed energetic effects.

Methods

Materials

Methyl p-nitrophenyl phosphate (MpNPP−) was synthesized previously.22 m-Nitrobenzyl phosphate (mNBP2−) was a gift from Alvan Hengge.55 The disodium salt of methyl phosphate (MeP2−) was obtained by hydrolysis of methyl dichlorophosphate (Aldrich) with excess sodium hydroxide. Phosphorothioate ester substrates (pNPPS2− and MpNPPS−) were synthesized previously56, 57 (J. Lassila and D.H., submitted). SP-MpNPPS- was obtained by reacting racemic MpNPPS− with NPP to completely hydrolyze the RP enantiomer (J. Lassila and D.H., submitted). The SP enantiomer was then purified by HPLC on a C-18 column in 0.1% TFA and a linear gradient of acetonitrile. All other reagents were from commercial sources. Site-directed mutants were prepared using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene).

AP expression and purification

Escherichia coli AP was purified using an N-terminal maltose binding protein (MBP) fusion construct (AP-MBP) in the pMAL-p2X vector (New England Biolabs) constructed previously.35 This vector includes coding regions for an N-terminal signal peptide for periplasmic export and a Factor Xa cleavage site between MBP and AP that releases E. coli AP residues 1–449 (numbering from after the wt AP signal peptide cleavage site). AP-MBP was used for protein expression because of the higher purity obtainable with the fusion construct and because the mutants used in this study were not stable to heating, a step in the previously described purification of AP.20 Rate constants obtained for wt and R166S AP purified from the AP-MBP fusion construct were identical to those obtained previously for phosphate monoester and diester reactions with AP expressed from the native promoter and signal peptide.20

E. coli SM547 (DE3) cells35, 58 containing AP-MBP were grown to an OD600 of 0.5 in rich medium and glucose (10 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, 5 g of NaCl, and 2 g of glucose per liter) with 50 μg/mL carbenicillin at 37 °C. IPTG was added to a final concentration of 0.3 mM to induce protein expression. After 6–8 hours, cells were harvested by centrifugation. Following osmotic shock and centrifugation, the supernatant was adjusted to 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, and 10 μM ZnCl2 and filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane (Nalgene). The sample was then loaded onto a 30 mL amylose column (New England Biolabs) at 4°C with a flow rate of ≤2 mL/min, washed with 2–3 column volumes of amylose column buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and 200 mM NaCl), and eluted with 10 mM maltose in amylose column buffer. Peak fractions were pooled, and the solution was adjusted to 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM maltose, and 5 mM CaCl2 by addition of the appropriate volumes of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 1 M CaCl2. To cleave the fusion protein, the sample was concentrated by centrifugation through a filter (10 kDa cutoff, Amicon) to ~40–50 mg free AP per mL and Factor Xa was added to the solution (2 units of Factor Xa per mg free AP, Novagen). After incubation for 3–4 days at room temperature to allow the reaction to proceed to >95% completion, the cleavage reaction mixture was diluted to 50 mL in buffer A (20 mM 1-methylpiperazine, 20 mM Bis-Tris-HCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.0), and loaded on to a 5 mL HiTrap Q Sepharose HP column (GE Healthcare). The column was washed with one column volume of buffer A and eluted with a linear gradient from buffer A to buffer B (20 mM 1-methylpiperazine, 20 mM Bis-Tris-HCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 5.0). Peak fractions were pooled and exchanged into storage buffer (10 mM NaMOPS, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, and 100 μM ZnCl2) by three cycles of concentration (centrifugation through a 10 kDa filter, Amicon) and dilution into storage buffer. For variants of AP that were expected to contain a bound Mg2+ ion, 100 μM MgCl2 was also included in the storage buffer. Purified protein was stored at 4 °C. Typical yields for a 6 L culture were 30–40 mg of pure protein. Purity was estimated to be >95% as judged by band intensities on Coomassie blue stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Protein concentration was determined by absorbance at 280 nm in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride, 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.5 using a calculated extinction coefficients of 31390 M−1 cm−1 (or 32675 M−1 cm−1 for variants with Tyr at position 322).59 Mass spectrometry confirmed that the cleaved, purified protein corresponded to AP residues 1–449.

An additional purification step was performed for proteins with severely compromised activity, such as R166S/E322Y AP, to remove contaminants that can interfere with measurement of low activities. After the amylose column and prior to Factor Xa cleavage, the fusion protein was purified on a HiTrap Q Sepharose HP column with the same pH gradient approach as described above for the final purification step. The fusion protein elutes in a peak that is well-separated from where free AP would elute, thus removing contaminants that would copurify with free AP in the final purification step.

Atomic emission spectroscopy

Protein metal ion content was determined by equilibrium dialysis followed by atomic emission spectroscopy. Samples of E322Y AP were analyzed both as purified and after >5 day incubations in ZnCl2 solutions as described in the main text (“AP Kinetics” section in Methods). Four mL of ≥2 μM enzyme samples were dialyzed in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, and varying amounts of ZnCl2 and MgCl2 with Spectra/Por 7 dialysis tubing (10 kD MWCO, Spectrum Labs). After three buffer changes, with at least 2 hour incubations after each buffer change and a total dialysis time of at least 16 hours, 3.6 mL samples of the dialysate were added to tubes containing 0.4 mL 1 M ammonium acetate, pH 5.3, and analyzed by atomic emission spectroscopy with an IRIS Advantage/1000 radial ICAP Spectrometer (Thermo Jarrell Ash, MA). Control samples of dialysis buffer were also measured in the same manner and used to correct for background. Amounts of zinc, magnesium, sulfur, and phosphorus were measured simultaneously. Amounts of protein were determined from sulfur content, and phosphorus content was measured to determine if the purified protein contained stoichiometric quantities of inorganic phosphate, as is known to be the case for wt AP.60 The results are summarized in Table 1.

Wt AP analyzed in this manner gave 2:1:1 Zn:Mg:protein monomer stoichiometry in the presence or absence of added divalent cations, as expected (Table 1). E322Y AP contained no detectable Mg above background quantities present in dialysis buffers, even when 10 μM MgCl2 was included in the dialysis buffer. As purified, E322Y AP contained only one equivalent of Zn per protein monomer, and after incubation for >5 days in ZnCl2 as described in the AP Kinetics section, two equivalents of Zn were detected per protein monomer (Table 1). No phosphorus above background quantities was detected for any protein except wt AP, which contained the expected one equivalent of phosphorus per protein monomer (Table 1).60

Crystallization. E322Y AP (at 9 mg/mL, in 10 mM NaMOPS, pH 8.0, and 50 mM NaCl) was crystallized at 20 °C by the hanging drop method against 0.2 M NH4F, 16–22% PEG 3350, and 500 μM ZnCl2. Crystals were passed through a 30% glycerol solution in mother liquor and 1 mM ZnCl2 (total) before direct immersion in liquid nitrogen.

Data collection

E322Y crystallized in space group P6322 with one dimer in the asymmetric unit. Diffraction data were collected at ALS (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory) on beamline 8.2.2. To confirm the presence of two Zn2+ ions in the active site, data were collected at the Zn absorption peak (1.2825 Å). Data were integrated and scaled using DENZO and SCALEPACK, respectively.61 Five percent of the observed data was set aside for cross validation. Data statistics are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Crystallographic Data and Model Statistics

| E322Y AP | |

|---|---|

| Data Collection | |

| Beamline | ALS 8.2.2 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.2825 |

| Space Group | P6322 |

| Unit Cell | |

| a (Å) | 161.6 |

| b (Å) | 161.6 |

| c (Å) | 139.3 |

| Resolution Range (Å) | 50-2.30 |

| Effective Resolution (I/σ = 2; Å) | 2.45 |

| No. of total reflections | 5283856 |

| No. of unique reflections | 86186 |

| Completeness (highest-res. shell) | 95.6 (66.6) |

| Redundancy (highest-res. shell) | 13.1 (7.5) |

| I/σ (highest-res. shell) | 12.6 (1.0) |

| Rmergea (%) | 17.4 |

| Refinement Statistics | |

| Rfactor (Rfree)b (%) | 18.1 (24.4) |

| No. of protein atoms | 6570 |

| No. of solvent atoms | 440 |

| No. of ligand atoms | 14 |

| Average B factor | 40.6 |

| RMSD bond lengths (Å) | 0.01 |

| RMSD bond angles (deg) | 1.0 |

Rmerge =Σ|Iobs−Iave|/ΣIobs.

Rfactor = Σ||Fobs| − |Fcalc||/Σ|Fobs|. See Brunger for a description of Rfree.67

Structure determination and refinement

Initial phases were determined by molecular replacement with Phaser62 using wt AP (pdb entry 1ALK)2 as a search model. At this point, σA-weighted 2Fo−Fc and Fo−Fc maps were inspected and a complete model comprising residues 4–449, two Zn2+ ions per monomer, and a Tyr residue in place of Glu322 was constructed using Coot.63 An anomalous difference map confirmed the presence of two Zn2+ ions in the expected positions in the active site based on the structure of wt AP (Supplementary Fig. 1). This map indicated two additional Zn2+ ions per AP dimer at crystal contacts on the protein surface. These Zn2+ ions are not observed in other AP structures from any species, and are most likely a consequence of the high ZnCl2 concentration used during crystallization. These ions were poorly ordered (indicated by B factors of 80 Å2 or more), but were included in the refinement process due to the unambiguous peaks in the anomalous difference map.

Additional, unexpected electron density in the active site was also observed in both the 2Fo−Fc and Fo−Fc maps (Supplementary Fig. 2). The density appeared roughly tetrahedral and suggested the possibility that inorganic phosphate, which binds and inhibits E322Y AP with a KI of 21 μM, was bound in the active site. No phosphate was added to the crystallization conditions, and no phosphate co-purified with E322Y AP (Table 1). However, a malachite green assay for phosphate (described above) and atomic emission spectroscopy for phosphorus revealed that the 50% PEG 3350 solution (Hampton Research) used for crystallization contained significant quantities of phosphate (~400 μM phosphate in a 20% PEG 3350 solution). This quantity of phosphate was more than sufficient to fully occupy the E322Y AP active site at the concentrations of protein used for crystallization. We therefore included an active site-bound phosphate molecule in the model for E322Y AP.

Simulated annealing refinement was carried out using a maximum likelihood amplitude-based target function as implemented in Phenix,64 resulting in an R factor of 22.7%. Further refinement and water picking was carried on with Phenix. Each stage of refinement was interspersed with manual corrections and model adjustments using Coot. A final round of refinement in Phenix treated each monomer as an independent TLS group. The values of R and Rfree for the final refined model were 18.1 and 24.4%, respectively. All structural figures were generated with POVScript+.65

AP kinetics

Values of the bimolecular rate constant kcat/KM were measured for wt and mutants forms of AP. Reactions were performed in 0.1 M NaMOPS, pH 8.0, 0.5 M NaCl, and 10 μM ZnCl2 at 25 °C in quartz cuvettes. For substrates containing 4-nitrophenolate leaving groups, formation of the product was monitored continuously at 400 nm using a Uvikon 9310 spectrophotometer. Reactions of alkyl phosphate substrates (mNBP2− and MeP2−) were monitored using a malachite green assay to detect release of inorganic phosphate as previously described.29 To detect low concentrations of inorganic phosphate, the protocol was modified slightly: 500 μL aliquots from the enzymatic reaction were quenched in 450 μL malachite green solution, and 50 μL of a 34% sodium citrate solution was added after 1 min. After 30 min, absorbance at 644 nm was measured in a Uvikon 9310 spectrophotometer. All rate constants were determined from initial rates. Values of kcat/KM were obtained under conditions where the reaction was shown to be first order in both enzyme and substrate over at least a 10-fold range in concentration.

The value of kcat/KM for the reaction of wt AP with MpNPP− was determined by conducting the reaction in the presence of 10 to 100 μM inorganic phosphate to ensure subsaturating conditions.25 The value of kcat/KM was calculated from the observed second-order rate constant with inhibition and the known inhibition constant for phosphate (KI = 1.1 μM at pH 8.0).20, 25

In initial reactions of E322Y AP mutants, product formation time courses exhibited pronounced upwards curvature. The extent of curvature increased with increasing ZnCl2 concentration up to 100 μM, suggesting that the purified protein was not fully occupied with two Zn2+ ions per protein monomer. Partial Zn2+ occupancy was confirmed by atomic emission spectroscopy. After extensive tests under a variety of conditions, we found that full Zn2+ occupancy could be achieved by incubating enzyme (≤10 μM) in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, and 50 μM ZnCl2 for >5 days at room temperature. Enzyme activated in this manner contained two Zn2+ ions per protein monomer (Table 1) and exhibited linear product formation time courses in reactions containing 10–100 μM ZnCl2. The protein was stable under these conditions for at least one month. Addition of 1 mM MgCl2 had no effect on activity.

The value of KM for the reaction of E322Y AP with pNPP2−is ~0.5 μM, which is too low to allow direct measurement of kcat/KM. Instead, kcat/KM was determined indirectly by measuring apparent second-order rate constants in the presence of 2 to 500 μM inorganic phosphate, a known inhibitor of AP.20, 25 This data was fit to a model for competitive inhibition and yielded the value of kcat/KM in the absence of inorganic phosphate as well as the value of KI for inorganic phosphate (Supplementary Fig. 4). The value of KI thus determined (22 ± 10 μM) was identical to that measured independently for the reactions of MpNPP− (21 ± 1 μM) and bis-pNPP− (21 ± 4 μM), providing confirmation that the value of KI used to determine kcat/KM for pNPP2− was accurate. For the reaction of R166S/E322Y AP with pNPP2−, the value of KM was 27 ± 11 μM, which allowed direct measurement of kcat/KM under subsaturating conditions.

Rate constants for E322Y and R166S/E322Y AP-catalyzed reactions were determined at pH 8.0 for comparison to previously determined rate constants for wt and R166S AP. The rate constants for both wt and R166S AP decrease with increasing pH, with a pKa of 7.9 ± 0.1, possibly due to binding of hydroxide ion to the bimetallo Zn2+ site.20, 25 Decreases in observed rate constants at pH 8.0 for AP mutants could arise not just from decreases in the ability of the enzyme to catalyze the reaction, but also from a shift in the basic limb of the pH-profile to a lower pKa. We therefore determined the pH-rate profiles for the reactions of E322Y and R166S/E322Y AP with pNPP2− over the pH range of 7–10 (Supplementary Fig. 6) using the buffer conditions previously described.20, 25 The rate constants for E322Y and R166S/E322Y AP reactions decrease with increasing pH, with pKa values of 8.5 ± 0.2 and 8.9 ± 0.2, respectively. Thus, the observed decreases in reactivity upon removal of the Mg2+ site reflect real decreases in the catalytic proficiency of AP, and not simply a shift in the basic limb of the pH-profile to a lower pKa.

Only an upper limit for kcat/KM for the reaction of R166S/E322Y AP with mNBP2− could be determined due to the presence of a contaminating activity that was present in multiple enzyme preparations. The contaminating activity was inferred based on differences between the vanadate inhibition of the mNBP2− reaction and the inhibition observed for the pNPP2−, MpNPP−, and bis-pNPP− reactions. Vanadate binds weakly to R166S/E322Y AP and oligomerizes at high concentrations,66 which prevented precise KI measurements. However, it was necessary to use vanadate instead of phosphate as an inhibitor because observed rates for mNBP2− hydrolysis reactions were determined by measuring production of phosphate. Vanadate inhibits the reactions of R166S/E322Y AP with pNPP2−, MpNPP−, and bis-pNPP− with a KI of ≥ 1 mM. However, the observed reaction of R166S/E322Y AP with mNBP2− was strongly inhibited by vanadate with a KI of ~50 μM, indicating that the observed mNBP2− hydrolysis activity arose from a contaminating enzyme. The upper limit for kcat/KM for the reaction of R166S/E322Y AP with mNBP2− of 0.02 M−1 s−1 was estimated from the observed rate constant in the presence of 5 mM vanadate, corrected for expected inhibition of authentic R166S/E322Y AP at this vanadate concentration.

Protein Data Bank accession codes

Protein coordinates and structure factors for E322Y AP have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession code 3DYC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the NIH to D.H. (GM64798). J.G.Z. was supported in part by a Hertz Foundation Graduate Fellowship. T.D.F. was supported by the Universitywide AIDS Research Program of the University of California (F03-ST-216). Portions of this research were conducted at the Advanced Light Source, a national user facility operated by Lawrence Berkeley National Labs. We thank Alvan Hengge for providing the m-nitrobenzyl phosphate substrate, Guangchao Li for assistance with AES measurements, and Axel Brunger for support and helpful discussions. We also thank members of the Herschlag lab for comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

kcat/KM reflects the difference in free energy between the transition state for the first irreversible reaction step and the ground state of free enzyme and substrate in solution. Thus, comparisons of kcat/KM for two different substrates reflect the same free enzyme ground state, unlike comparisons of kcat, which may already include differences in active site interactions between substrates in the ground state E·S complexes. Comparisons of kcat can be further complicated if non-chemical steps like product release are rate-determining, as is the case for AP at alkaline pH.1 We further note that kcat cannot be measured for the promiscuous reactions described below because these substrates do not saturate at achievable concentrations.20, 22, 23 For the reactions discussed in this work, the first irreversible step that limits kcat/KM is the chemical step involving departure of the leaving group, except for the reaction of wt AP with pNPP2− in which a binding or conformational step is rate-determining.24–26

kcat/KM is limited by the chemical step for AP-catalyzed monoester and diester hydrolysis reactions, except for the fastest monoester substrates in which a non-chemical step is rate limiting.22, 25, 29

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Coleman JE. Structure and mechanism of alkaline phosphatase. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1992;21:441–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.21.060192.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim EE, Wyckoff HW. Reaction mechanism of alkaline phosphatase based on crystal structures. Two-metal ion catalysis. J Mol Biol. 1991;218:449–464. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90724-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beese LS, Steitz TA. Structural basis for the 3′-5′ exonuclease activity of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I: A two metal ion mechanism. EMBO J. 1991;10:25–33. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steitz TA. DNA polymerases: Structural diversity and common mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17395–17398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stec B, Holtz KM, Kantrowitz ER. A revised mechanism for the alkaline phosphatase reaction involving three metal ions. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:1303–1311. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auld DS. Zinc coordination sphere in biochemical zinc sites. Biometals. 2001;14:271–313. doi: 10.1023/a:1012976615056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le Du MH, Lamoure C, Muller BH, Bulgakov OV, Lajeunesse E, Menez A, Boulain JC. Artificial evolution of an enzyme active site: Structural studies of three highly active mutants of Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase. J Mol Biol. 2002;316:941–953. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Backer M, McSweeney S, Rasmussen HB, Riise BW, Lindley P, Hough E. The 1.9 angstrom crystal structure of heat-labile shrimp alkaline phosphatase. J Mol Biol. 2002;318:1265–1274. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weston J. Mode of action of bi- and trinuclear zinc hydrolases and their synthetic analogues. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2151–2174. doi: 10.1021/cr020057z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Llinas P, Stura EA, Menez A, Kiss Z, Stigbrand T, Millan JL, Le Du MH. Structural studies of human placental alkaline phosphatase in complex with functional ligands. J Mol Biol. 2005;350:441–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang E, Koutsioulis D, Leiros HKS, Andersen OA, Bouriotis V, Hough E, Heikinheimo P. Crystal structure of alkaline phosphatase from the Antarctic bacterium TAB5. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:1318–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleland WW, Hengge AC. Enzymatic mechanisms of phosphate and sulfate transfer. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3252–3278. doi: 10.1021/cr050287o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tibbitts TT, Murphy JE, Kantrowitz ER. Kinetic and structural consequences of replacing the aspartate bridge by asparagine in the catalytic metal triad of Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase. J Mol Biol. 1996;257:700–715. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu X, Kantrowitz ER. Binding of magnesium in a mutant Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase changes the rate-determining step in the reaction mechanism. Biochemistry. 1993;32:10683–10691. doi: 10.1021/bi00091a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zalatan JG, Fenn TD, Brunger AT, Herschlag D. Structural and functional comparisons of nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase and alkaline phosphatase: Implications for mechanism and evolution. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9788–9803. doi: 10.1021/bi060847t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerlt JA, Babbitt PC. Divergent evolution of enzymatic function: Mechanistically diverse superfamilies and functionally distinct suprafamilies. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:209–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Brien PJ, Herschlag D. Catalytic promiscuity and the evolution of new enzymatic activities. Chem Biol. 1999;6:R91–R105. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khersonsky O, Roodveldt C, Tawfik DS. Enzyme promiscuity: evolutionary and mechanistic aspects. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:498–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen RA. Enzyme recruitment in evolution of new function. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1976;30:409–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.30.100176.002205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Brien PJ, Herschlag D. Functional interrelationships in the alkaline phosphatase superfamily: Phosphodiesterase activity of Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase. Biochemistry. 2001;40:5691–5699. doi: 10.1021/bi0028892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Du MH, Stigbrand T, Taussig MJ, Menez A, Stura EA. Crystal structure of alkaline phosphatase from human placenta at 1.8 Å resolution. Implication for a substrate specificity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9158–9165. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zalatan JG, Herschlag D. Alkaline phosphatase mono- and diesterase reactions: Comparative transition state analysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1293–1303. doi: 10.1021/ja056528r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Brien PJ, Herschlag D. Sulfatase activity of E. coli alkaline phosphatase demonstrates a functional link to arylsulfatases, an evolutionarily related enzyme family. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:12369–12370. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Labow BI, Herschlag D, Jencks WP. Catalysis of the hydrolysis of phosphorylated pyridines by alkaline phosphatase has little or no dependence on the pKa of the leaving group. Biochemistry. 1993;32:8737–8741. doi: 10.1021/bi00085a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Brien PJ, Herschlag D. Alkaline phosphatase revisited: Hydrolysis of alkyl phosphates. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3207–3225. doi: 10.1021/bi012166y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simopoulos TT, Jencks WP. Alkaline phosphatase is an almost perfect enzyme. Biochemistry. 1994;33:10375–10380. doi: 10.1021/bi00200a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fersht A. Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science. W. H. Freeman and Company; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Brien PJ, Lassila JK, Fenn TD, Zalatan JG, Herschlag D. Arginine coordination in enzymatic phosphoryl transfer: Evaluation of the effect of Arg166 mutations in Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:7663–7672. doi: 10.1021/bi800545n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zalatan JG, Catrina I, Mitchell R, Grzyska PK, O’Brien PJ, Herschlag D, Hengge AC. Kinetic isotope effects for alkaline phosphatase reactions: Implications for the role of active-site metal ions in catalysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9789–9798. doi: 10.1021/ja072196+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galperin MY, Bairoch A, Koonin EV. A superfamily of metalloenzymes unifies phosphopentomutase and cofactor-independent phosphoglycerate mutase with alkaline phosphatases and sulfatases. Protein Sci. 1998;7:1829–1835. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galperin MY, Jedrzejas MJ. Conserved core structure and active site residues in alkaline phosphatase superfamily enzymes. Proteins. 2001;45:318–324. doi: 10.1002/prot.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirby AJ, Younas M. The reactivity of phosphate esters. Reactions of diesters with nucleophiles. J Chem Soc B. 1970:1165–1172. [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Brien PJ, Herschlag D. Does the active site arginine change the nature of the transition state for alkaline phosphatase-catalyzed phosphoryl transfer? J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:11022–11023. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Catrina I, O’Brien PJ, Purcell J, Nikolic-Hughes I, Zalatan JG, Hengge AC, Herschlag D. Probing the origin of the compromised catalysis of E. coli alkaline phosphatase in its promiscuous sulfatase reaction. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5760–5765. doi: 10.1021/ja069111+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nikolic-Hughes I, O’Brien PJ, Herschlag D. Alkaline phosphatase catalysis is ultrasensitive to charge sequestered between the active site zinc ions. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9314–9315. doi: 10.1021/ja051603j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holtz KM, Stec B, Kantrowitz ER. A model of the transition state in the alkaline phosphatase reaction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8351–8354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirsch AKH, Fischer FR, Diederich F. Phosphate recognition in structural biology. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46:338–352. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barford D, Flint AJ, Tonks NK. Crystal structure of human protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Science. 1994;263:1397–1404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stuckey JA, Schubert HL, Fauman EB, Zhang ZY, Dixon JE, Saper MA. Crystal structure of Yersinia protein tyrosine phosphatase at 2.5 Å and the complex with tungstate. Nature. 1994;370:571–575. doi: 10.1038/370571a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang M, Zhou M, VanEtten RL, Stauffacher CV. Crystal structure of bovine low molecular weight phosphotyrosyl phosphatase complexed with the transition state analog vanadate. Biochemistry. 1997;36:15–23. doi: 10.1021/bi961804n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jedrzejas MJ, Chander M, Setlow P, Krishnasamy G. Structure and mechanism of action of a novel phosphoglycerate mutase from Bacillus stearothermophilus. EMBO J. 2000;19:1419–1431. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.7.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nukui M, Mello LV, Littlejohn JE, Setlow B, Setlow P, Kim K, Leighton T, Jedrzejas MJ. Structure and molecular mechanism of Bacillus anthracis cofactor-independent phosphoglycerate mutase: A crucial enzyme for spores and growing cells of Bacillus species. Biophys J. 2007;92:977–988. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.093872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fersht AR, Shi JP, Knilljones J, Lowe DM, Wilkinson AJ, Blow DM, Brick P, Carter P, Waye MMY, Winter G. Hydrogen bonding and biological specificity analyzed by protein engineering. Nature. 1985;314:235–238. doi: 10.1038/314235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bryan P, Pantoliano MW, Quill SG, Hsiao HY, Poulos T. Site-directed mutagenesis and the role of the oxyanion hole in subtilisin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3743–3745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wells JA, Cunningham BC, Graycar TP, Estell DA. Importance of hydrogen-bond formation in stabilizing the transition-state of subtilisin. Phil Trans R Soc Lond A. 1986;317:415–423. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strater N, Lipscomb WN, Klabunde T, Krebs B. Two-metal ion catalysis in enzymatic acyl- and phosphoryl-transfer reactions. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1996;35:2024–2055. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilcox DE. Binuclear metallohydrolases. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2435–2458. doi: 10.1021/cr950043b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steitz TA, Steitz JA. A general two-metal-ion mechanism for catalytic RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6498–6502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang W, Lee JY, Nowotny M. Making and breaking nucleic acids: Two-Mg2+-ion catalysis and substrate specificity. Mol Cell. 2006;22:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stahley MR, Strobel SA. Structural evidence for a two-metal-ion mechanism of group I intron splicing. Science. 2005;309:1587–1590. doi: 10.1126/science.1114994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toor N, Keating KS, Taylor SD, Pyle AM. Crystal structure of a self-spliced group II intron. Science. 2008;320:77–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1153803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pingoud A, Fuxreiter M, Pingoud V, Wende W. Type II restriction endonucleases: structure and mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:685–707. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4513-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mitic N, Smith SJ, Neves A, Guddat LW, Gahan LR, Schenk G. The catalytic mechanisms of binuclear metallohydrolases. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3338–3363. doi: 10.1021/cr050318f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kraut DA, Carroll KS, Herschlag D. Challenges in enzyme mechanism and energetics. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:517–571. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grzyska PK, Czyryca PG, Purcell J, Hengge AC. Transition state differences in hydrolysis reactions of alkyl versus aryl phosphate monoester monoanions. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:13106–13111. doi: 10.1021/ja036571j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hollfelder F, Herschlag D. The nature of the transition state for enzyme-catalyzed phosphoryl transfer. Hydrolysis of O-aryl phosphorothioates by alkaline phosphatase. Biochemistry. 1995;34:12255–12264. doi: 10.1021/bi00038a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herschlag D, Piccirilli JA, Cech TR. Ribozyme-catalyzed and nonenzymatic reactions of phosphate diesters: Rate effects upon substitution of sulfur for a nonbridging phosphoryl oxygen atom. Biochemistry. 1991;30:4844–4854. doi: 10.1021/bi00234a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chaidaroglou A, Brezinski DJ, Middleton SA, Kantrowitz ER. Function of arginine-166 in the active site of Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8338–8343. doi: 10.1021/bi00422a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gill SC, von Hippel PH. Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal Biochem. 1989;182:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bloch W, Schlesinger MJ. Phosphate content of Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase and its effect on stopped flow kinetic studies. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:5794–5805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Likelihood-enhanced fast translation functions. Acta Cryst. 2005;D61:458–464. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905001617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Cryst. 2004;D60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Read RJ, Sacchettini JC, Sauter NK, Terwilliger TC. PHENIX: Building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Cryst. 2002;D58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fenn TD, Ringe D, Petsko GA. POVScript+: A program for model and data visualization using persistence of vision ray-tracing. J Appl Cryst. 2003;36:944–947. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Crans DC, Smee JJ, Gaidamauskas E, Yang LQ. The chemistry and biochemistry of vanadium and the biological activities exerted by vanadium compounds. Chem Rev. 2004;104:849–902. doi: 10.1021/cr020607t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brunger AT. Free R value: A novel statistical quantity for assessing the accuracy of crystal structures. Nature. 1992;355:472–475. doi: 10.1038/355472a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.