Abstract

OBJECTIVE

We implemented and monitored a clinical service, Consultation Planning, Recording and Summarizing (CPRS), in which trained facilitators elicit patient questions for doctors, and then audio-record, and summarize the doctor-patient consultations.

METHODS

We trained 8 schedulers to offer CPRS to breast cancer patients making treatment decisions, and trained 14 premedical interns to provide the service. We surveyed a convenience sample of patients regarding their self-efficacy and decisional conflict. We solicited feedback from physicians, schedulers, and CPRS staff on our implementation of CPRS.

RESULTS

278 patients used CPRS over the 22 month study period, an exploitation rate of 32% compared to our capacity. Thirty-seven patients responded to surveys, providing pilot data showing improvements in self-efficacy and decisional conflict. Physicians, schedulers, and premedical interns recommended changes in the program’s locations; delivery; products; and screening, recruitment and scheduling processes.

CONCLUSION

Our monitoring of this implementation found elements of success while surfacing recommendations for improvement.

PRACTICE IMPLICATIONS

We made changes based on study findings. We moved Consultation Planning to conference rooms or telephone sessions; shortened the documents produced by CPRS staff; diverted slack resources to increase recruitment efforts; and obtained a waiver of consent in order to streamline and improve ongoing evaluation.

Keywords: Audio-recording, Implementation, Question prompting, Coaching, Shared Decision Making, Summaries

1. Introduction

Breast cancer patients consult specialists to arrive at treatment strategies, choosing among surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and biologic therapy. These treatments offer reduction in mortality and recurrence risk, at the cost of increased risk of complications, side effects, and long-term harm. As a means to effective information gathering and participation in decisions, experts advise breast cancer patients to make a list of questions before they attend their meetings with specialists; bring a friend to take notes; and make an audio-recording of the consultation [1].

Researchers have systematically reviewed the evidence base surrounding such visit preparation, audio-recording, and summarizing practices. Scott et al. found that providing audio recordings and/or consultation summaries can increase patient knowledge and patient satisfaction [2]. Kinnersley et al. found that “interventions before consultations for helping patients address their information needs… seem to help patients ask more questions in consultations” [3]. These and other reviews are not definitive, due to the relatively small number of studies and the mixed results. However, as Kinnersley and colleagues point out, “In terms of practice there are strong justifications unrelated to evidence-based medicine for adopting a collaborative approach to the medical encounter, such as, for example, patient preferences and moral imperatives” [3].

Indeed, based on our studies of visit preparation and recording [4–6], as well as evidence about the benefits of very similar interventions [7, 8], we began to pilot Consultation Planning, Recording, and Summarizing (CPRS) in 1998 at the UCSF BCC. Since then, we have found no research describing the routine implementation of visit preparation, recording, and summarizing interventions as integrated components of a clinical service. While the components have been shown in clinical studies to be satisfying to patients, and effective to varying degrees in improving various patient outcomes, researchers do not know whether integration into a clinic workflow is possible, how it affects patient measures such as self-efficacy and decisional conflict, and whether integration into routine practice is acceptable to physicians, schedulers, and staff affected by the interventions and can be sustained over the long term.

We therefore monitored our implementation of Consultation Planning, Recording, and Summarizing (CPRS) at the point in its evolution when we were integrating it more fully into programs in our clinic. Our hypotheses were that CPRS could be integrated into clinical care at our academic medical enter, that it would be associated with improvements in patient self-efficacy and decisional conflict, that it would be acceptable to physicians, schedulers, and staff, and that we could engage in continuous quality improvement to sustain and enhance the implementation. Specifically, this study asked the following questions:

How many patients did we serve with CPRS?

What changes in decisional self-efficacy and decisional conflict did we observe in a convenience sample of patients using CPRS?

What aspects of CPRS should be continued, discontinued, or improved in order to assure the ongoing success of the implementation?

2. Methods

2.1 Setting and Population

The UCSF Breast Care Center (BCC) is a multidisciplinary clinic in a university medical center. In 2005, the BCC saw 599 breast cancer patients new to the clinic who consulted specialists about treatment decisions over the course of 843 visits, with 44% of those visits being to 5 surgeons and 56 % to 9 oncologists. The average age in 2005 was 57 years. The distribution of diagnosis by stage was 94 new patients with ductal or lobular carcinoma in situ (16%); 414 patients with stage 1–3 breast cancer (69%); 19 patients with metastatic disease (3%); and 72 patients with unknown/unrecorded stage (12%). The distribution of first treatment course was 32% lumpectomy, 21% mastectomy, and 20% chemotherapy. The ethnic/racial distribution in 2005 was 64.5% White, 18.5% Asian, 7.5% Hispanic, 6.5% African American, and 3.0% Unknown/Other. Most patients had private (67%) or public (29.5%) insurance, with 3.5% uninsured.

2.2 Study design, sample, and participants

The study consisted of prospectively planned field observations in which we qualitatively and quantitatively monitored the process and impact of the CPRS service in the UCSF BCC through record reviews, surveys, and interviews. Patients were eligible for CPRS if they had a confirmed diagnosis of breast cancer, and were scheduled for an appointment at the UCSF BCC regarding a treatment decision between March 1, 2005 and December 31, 2006, during one of the two daily times when a CPRS staff member was available. We approached patients to respond to efficacy surveys if they spoke and wrote English, and if our staff could approach them to obtain informed consent and administer surveys without interrupting other visit activities such as rooming, vital signs, patient history questionnaires, history-taking by residents, or discussions with nurses and attending physicians.

We also studied physician, schedulers, and CPRS staff reactions to the implementation. We included, over the study period, five surgeons and nine oncologists who saw breast cancer patients in our clinic. We included the schedulers who acted as new patient schedulers for the physicians, and the 14 CPRS staff that performed CPRS for the patients of the physicians. The CPRS staff consisted of BCC employees participating in a premedical internship program after graduation from college and before attending medical school. BCC faculty hire these interns as research study coordinators, and assign them to the CPRS team for one day per week as a means of enriching their internship experience with additional patient contact. The CPRS staffing policies meant that one day per week per CPRS staff member translated into a capacity of two CPRS service slots per day, one in the morning, and one in the afternoon.

We obtained ethics approval from the UCSF Committee on Human Research and the Human Subjects Research Review Board of the Department of Defense, and obtained informed consent from patients for study surveys.

2.3 Intervention and Procedures

Members of our study team had developed [4], evaluated [9, 10], and begun to implement [11] CPRS between 1994 and 2004. In 2005, we obtained a grant to better integrate CPRS, along with other decision support programs, into the routine clinical care workflow at the UCSF BCC.

After a needs assessment and program redesign phase featuring input from clinic physicians, nurses, and schedulers, as well as our institution’s risk management department, the Director of the BCC decided that new patient schedulers would henceforth offer CPRS (along with other supportive services) to breast cancer patients at the time they were scheduling their appointments with physicians. We therefore amended the clinic scheduler job descriptions, and established monthly meetings between the schedulers and the Decision Services team to monitor the scheduling of CPRS.

Schedulers used a script we provided to describe CPRS to patients as a supportive service in which a CPRS staff member would meet the patient at the clinic 60–90 minutes in advance of their medical appointment, help the patient brainstorm and write down a list of questions for the doctor, and then accompany the patient, audio-recording the medical appointment and taking notes.

Physicians at the BCC were already accustomed to CPRS due to the prior period of development, piloting, and ad-hoc (i.e. non-integrated) implementation [11–13]. During the study period there was a maximum of 8 and a total of 14 CPRS staff, since the study period spanned two fiscal years during which some interns went on to medical school and new interns arrived. We offered the CPRS training at the start of each fiscal year in a 3-day workshop led by the Director of Decision Services (JB) and featuring assistance from second-year interns (including JC, DC, ML). The CPRS trainees learned, through lectures and role-plays, to administer a Consultation Planning prompt sheet (see Table 1), and to paraphrase and summarize patient questions into Consultation Plans (Table 2) and physician responses into Consultation Summaries (Table 3). Trainees learned to word-process these documents on portable computers, print copies for patients, family members, and attending physicians, and store copies on a secure clinic file server. Trainees also learned to audio-record the physician visits using digital audio recorders, burn compact discs for patients after their visit, and store electronic copies on the secure clinic file server as required by the UCSF Risk Management department. We enjoined the trainees from providing medical advice or information as part of the CPRS encounter, and monitored their compliance with these and other CPRS procedures and policies, documented in a 247-page reference guide, during weekly staff meetings [14].

Table 1.

Consultation Planning Prompt Sheet

| The CPRS staff member uses the high level prompts as open-ended probes to elicit patient questions, and if the patient cannot think of questions, together they review the secondary prompts to stimulate patient questions. The staff member then summarizes the patient questions and concerns in a separate word-processed document (see Appendix 2) |

| Situation – What are your questions or concerns about your situation? |

| What do you know about your situation? Questions about key facts? Diagnosis? Test reports? Pathology report? Anything unusual? |

| Choices – What are your questions or concerns about what you can do? |

| What can you do? Questions about tests? Active monitoring (no further treatment)? Treatment options? Second opinions? Clinical trials? Complementary therapies? Newest treatments? Most proven treatments? Most aggressive treatments? Least aggressive? Middle ground treatments? Remedies for side effects? What to stop doing? What to start? Decisions to make now? Decisions to make later? Past decisions to revisit? |

| Objectives – What are your questions or concerns about what you want? |

| What do you want? Goals for doctor’s appointment? Goals for treatment? Preferences about length and quality of life? Regarding quality of life: what to continue/protect? (e.g. relationships, work, hobbies, daily activities, body image, sexuality, child-rearing, etc.)? Preferences about timing, frequency, duration, intensity, location, costs of treatment? Concerns about interactions with other treatments or medical conditions? Hopes? Fears? Unspoken thoughts or feelings? Learning preference: visual or auditory or other type of learner? Preferred approach to decision-making: holistic or analytical? Qualitative, informal (e.g. talking about pros and cons, journaling/writing)? Quantitative, formal (e.g. rating and weighting? statistical number-crunching)? Somewhere in between? (e.g. filling out a table)? If quantitative: interested in survival/recurrence/complication rates for each choice? Prefer rates to be explained in numbers (e.g. 60% ten-year survival rate) or words (e.g. more likely than not to survive)? Level of effort to expend in analyzing decision? Resources? |

| People – What are your questions or concerns about the people involved in your decision? |

| Who can help? Questions about where else to go for advice or information or support? How do you want this doctor involved in your treatment decisions? Other doctors? Other people (e.g. who come to appointments)? Whom do you want to have a voice in analyzing your decisions (i.e., seek their input)? A vote (involve them in arriving at a final decision)? Visibility (keep them informed)? Who else do you need to talk to? Anyone to exclude? |

| Evaluation – What are your questions or concerns about how each choice affects each objective? |

| How does each choice affect each objective? Questions about specific choices and specific objectives? Baseline prognosis (prognosis with no further treatment)? How choices will affect survival, recurrence (e.g. rates for patients like you?) How choices will affect quality of life? Likelihood of complications, short and long-term side effects? Best-case scenario, worst case, most likely (e.g. in terms of survival, quality of life) for each choice? |

| Decisions – What are your questions or concerns about arriving at a decision? |

| Which choice is best? What are the next steps? Who will do what, when, where, why, how? What resources can help overcome any barriers to next steps? If undecided/unready: Timeline/deadline for arriving at a decision? Priority relative to other commitments? Resources for gathering information/data about how choices affect objectives? Who can help (revisit People above)? What do you want (revisit Objectives above)? |

Table 2.

Example Consultation Plan [names and identifying details redacted]

| Using a portable computer, a CPRS staff member created a word-processed list of questions and concerns by summarizing and paraphrasing the patient’s verbal statements during the Consultation Planning interview just before the medical appointment. The patient approves the staff member’s summary and signs a Service Agreement form indicating that these are the patient’s own questions and that the staff member has not provided advice or information. The CPRS staff member then prints copies of the Consultation Plan for the patient, accompaniers, and the physician to review before and during the appointment. |

| SITUATION |

| I was diagnosed with breast cancer in August and had surgery a month later, followed by radiation |

| I want to understand the following terms on the pathology report: |

| Moderately differentiated infiltrating carcinoma |

| Surgical margins free of tumor – does that mean that there is none for 1/2 cm around edges? |

| I am currently on Arimidex. |

| CHOICES |

| Chemotherapy? |

| If I need chemotherapy, what are the options? |

| Least aggressive therapies? Most aggressive? |

| What does Dr. Smith recommend and why? |

| Neulasta along with chemotherapy? |

| Any further tests? |

| OBJECTIVES For treatment |

|

| For appointment |

|

| PEOPLE |

| I have a friend who will drive me up here on Fridays if necessary. My daughter is supportive. |

| EVALUATION |

| Why do they recommend taking Arimidex for only 5 years? |

| Is there a way to receive chemotherapy gradually over a longer period of time? I would prefer receiving chemotherapy this way, if I do need it. Are infections due to a “jolt to system” from chemotherapy? Is gradual delivery as effective? If I do need chemotherapy: |

| I would like to understand the benefits vs. risks of chemotherapy. |

| I would also like to learn about recovery and side effects of chemotherapy. |

| DECISIONS |

| I will decide whether I need chemotherapy based on my discussion with Dr. Smith. I will decide within the next 24/48 hours. I will take into account my daughter’s opinion. |

Table 3.

Example Consultation Summary [names and identifying information redacted.]

| Using a portable computer and digital audio-recorder, a CPRS staff member takes notes and records the consultation. Afterwards, the CPRS staff member creates a word-processed summary of the physician’s responses to the questions and concerns listed on the patient’s Consultation Plan. The CPRS staff member sends a copy of the Consultation Summary to the patient, along with a compact disc containing the recording of the visit. |

| SITUATION |

| Infiltrating ductal carcinoma breaks through duct membrane and invades breast tissue. Your closest margin is 0.5 cm, others are 2.0 cm. |

| CHOICES |

| No chemotherapy |

| Stay on Arimidex, maintain weight, exercise |

| Come to UCSF once every 4–6 months for monitoring, have mammograms done here |

| Chemotherapy |

| 4 cycles of Adriamycin + Cytoxan (AC) |

| 1 dose every 3 weeks, each dose takes about 90 min |

| 4 cycles of Taxotere + Cytoxan (TC) |

| We can try to get authorization for you to receive Neulasta on day 2 at home. Depends on insurance and cost (oftentimes insurance requires that Neulasta be given at an infusion center). |

| Tests |

| No further tests anticipated. If you do decide to go on AC, we need to do an echocardiogram or a MUGA scan on your heart to determine how well it squeezes. |

| OBJECTIVES |

| Gather enough information to make an informed decision about whether to undergo chemotherapy. |

| PEOPLE |

| Oncologists in your area for Neulasta shots: Dr. X and Dr. Y |

| The practice assistant will contact you to schedule chemotherapy if you decide to do it at UCSF |

| EVALUATION |

| Chemotherapy vs. no chemotherapy |

| Adjuvant output (10-year risk estimate – based on cases similar to yours from various databases.) |

| 24.5% risk of recurrence without any treatment besides surgery and radiation |

| 12.5% risk of recurrence if taking aromatase inhibitor |

| 9.4% risk of recurrence if taking chemotherapy plus aromatase inhibitor |

| So Adjuvant! estimates an overall 2.6% reduction in 10-year risk from chemotherapy |

| Chemotherapy Options |

| Adriamycin + Cytoxan (AC) |

| Side effects from adriamycin: hair loss, nausea, vomiting, fatigue |

| Small (1%) chance of damaging the heart by affecting strength of muscle responsible for contractions |

| Taxotere + Cytoxan (TC) |

| Possible side effects: hair loss, body aches, fever, neutropenia (low blood counts) = risk of infections. |

| Neulasta causes bone pain. |

| DECISIONS |

| Are you comfortable with idea that you have 15–19% risk of recurrence in next 10 years without doing chemotherapy? Is it worth it to do chemotherapy for a 3% benefit in recurrence? That is the key issue. |

| I would recommend chemotherapy, since you are young and healthy. We usually start chemotherapy within 6–8 weeks of surgery but would definitely want to start within 3–4 months after surgery |

2.4 Outcomes, measures, and instruments

For study question 1, as a measure of the degree to which we were able to deliver CPRS we counted how many patients received the services and compared this to our capacity.

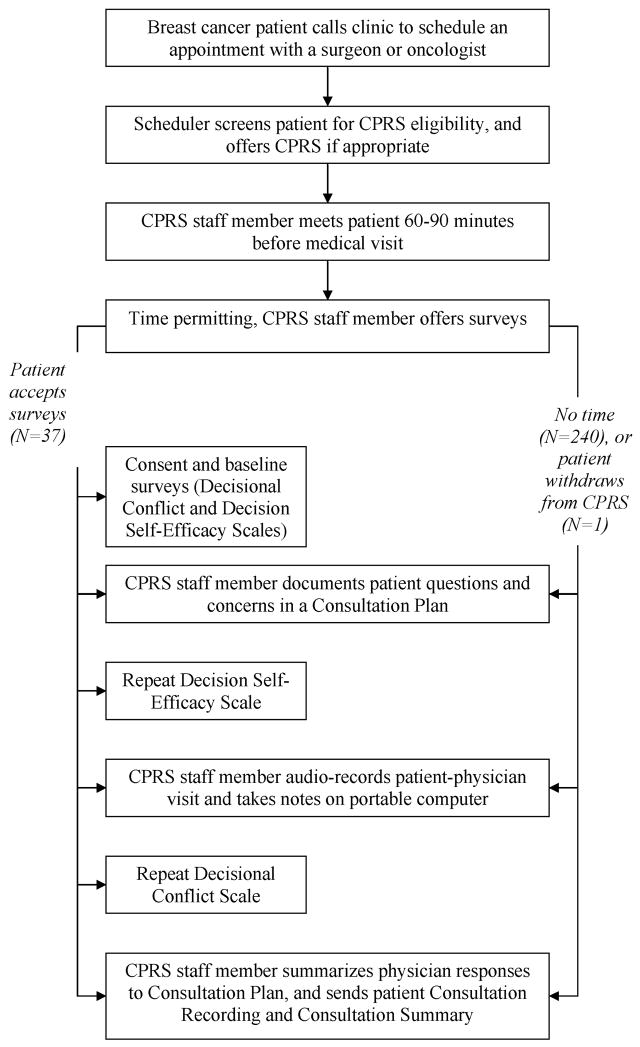

For study question 2, as a means of measuring changes in decision self-efficacy and decisional conflict in patients we administered the Decision Self Efficacy (DSE) and Decisional Conflict (DCS) scales to patients before, during, and after their visits. See Figure 1. The DSE and DCS are Likert scales with acceptable levels of validity and reliability documented in similar studies and similar settings [15, 16]. The DSE measures patients’ confidence in their ability to participate in decision making [17]. The DCS measures the level of decisional conflict perceived by the patient [18].

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing sequence of interventions, including surveys for a convenience sample of patients. CPRS denotes Consultation Planning, Recording, and Summarizing.

For study question 3, over the study period, we were interested in which program design elements physicians, schedulers, and CPRS staff felt were acceptable and should be continued; which were unacceptable and should be discontinued; and which required improvement and should be modified as a means of improving the sustainability of CPRS. The instrument for measuring this outcome consisted of semi-structured interview guides based on the Critical Incident Technique [19], including probes regarding the program infrastructure, policies, processes, techniques, and tools.

2.5 Data Collection, Management, and Analysis

Study Question 1

Schedulers used the clinic scheduling system to schedule CPRS sessions with patients. We compared the total number of completed CPRS sessions to the number of available CPRS slots based on a capacity of two per day, one in the morning and one in the afternoon.

Study Question 2

Physicians requested that we avoid disrupting the flow of patients through the clinic, so we administered our study surveys only when it was convenient, i.e. when patients were not needed by the clinic. For testing the null hypothesis of no change in DCS or DSE score against the alternative of a significant change, we used a two-sided matched-pair t-test of significance at the 0.05 level.

Study Question 3

In order to collect interview data, during regular clinic meetings we probed for physicians, schedulers, and CPRS staff to provide specific best and worst cases of how CPRS had performed in the past with respect to the program goals, and what aspects of the service to continue, discontinue, or change. We stated the program goals as helping patients list their questions and retain records of the answers provided by their physicians. We obtained input from physicians at their weekly multidisciplinary review meeting, and monthly and weekly input from the schedulers and CPRS staff during their respective regular meetings with the Director of Decision Services (JB). The study team reviewed notes from these meetings, and discussed program changes during weekly Decision Services management meetings. The Director of Decision Services made the final decisions on program design, and documented them in the Decision Services Reference Guide, a 247 page manuscript that summarizes the policies and procedures for the program [14].

3. Results

Study Question 1

278 patients received CPRS over 22 months. We estimated that our maximum theoretical capacity during this period was approximately 880 CPRS service units, meaning that the exploitation rate was approximately 32%.

Study Question 2

We approached 38 patients (out of 278, 13%), all female, to answer DSE and DCS surveys. These patients met the physician criteria of not being engaged in other clinic activities such as filling out patient history forms or being roomed by nurses. One patient withdrew from CPRS all 37 and was also not surveyed, leaving 37 survey respondents. Their ages ranged from 35–77, with a median of 57. Most of the patients had graduated from high school and attended some college (n=29, 83%). Twelve (32%) had lobular or ductal carcinoma in situ (stage 0); 15 (41%) had invasive lobular or ductal cancer (stages 1–3); eight (22%) had metastatic cancer (stage 4); 1 (3%) had no cancer and 1 (3%) had colloid cancer.

Among these respondents, CP was associated with an increased DSE score of 0.29 (mean 3.24 to 3.53, mean effect size 0.29, standard deviation for the change of 0.34, standardized effect size of 0.85, 95% confidence interval from 0.18 to 0.41, p<0.001),. CPRS combined with the doctor’s consultation was associated with a reduced DCS score of 0.75 (mean 2.78 to 2.03, mean effect size −0.72, standard deviation for the change of 0.75, standardized effect size of 0.96, 95% confidence interval from −0.97 to −0.46, p<0.001).

Study Question 3

Physicians endorsed CPRS, which they saw as helping patients organize and clarify questions before the medical appointment; giving physicians a preview before the visit so they could strategize in advance about how to conduct the consultation; and helping ensure that all of the patient’s questions were addressed during the appointment. Physicians also felt that interns were effective as CPRS staff, and supported continuing the arrangement under which clinic research assistants were assigned to CPRS duties one day per week.

Physicians thought we should discontinue the practice of conducting CPRS in exam rooms while patients were waiting. Physicians felt that this occasionally disrupted the clinic processes of rooming the patient and taking vital signs, and frequently exacerbated clinic delays by tying up overbooked clinic exam rooms. They also suggested that we make the practice of having physicians review each Consultation Summary optional, and instead make it clear to patients that the summaries and recordings were provided by CPRS as a convenience for patients, were not necessarily reviewed by physicians, and could contain errors and omissions.

Physicians proposed that CPRS staff change their practices so that Consultation Plans and Summaries be more succinct. They felt that Consultation Plans should run 1–2 pages, and Summaries 2–3 pages.

The schedulers also endorsed the continued implementation of CPRS. They reported that patients particularly resonated with being offered an accompanier to take notes and audio-record the medical appointments. However, the schedulers felt that they could not reliably offer CPRS since this required spending more time with patients and they were chronically behind on their phone calls and scheduling tasks. Therefore, in order to promote increased exploitation of CPRS, the schedulers suggested that the CPRS staff identify, through the clinic scheduling system, those patients with upcoming appointments on days when there were still available CPRS slots, and call those patients until the slots were filled.

Schedulers also reported that the timing of CPRS was often a barrier to scheduling the service for patients coming from far away or for patients who had an early morning appointment. Therefore, schedulers requested that CPRS staff be available to conduct Consultation Planning by telephone with such patients.

The CPRS staff also endorsed the continued implementation of CPRS. They cited the opportunity to work closely with patients and make a positive contribution to patient care at the BCC.

The CPRS staff did wish to modify certain aspects of the program related to waiting for physicians. Specifically, after completing their Consultation Planning duties, CPRS staff frequently had to wait in the clinic for the attending physician to conduct the medical appointment. The CPRS staff found that they could not make productive use of this time, which could range from minutes to hours, depending on clinic delays, because they needed to monitor the physician’s location and intercept them to give them the patient’s Consultation Plan before the start of the appointment. They requested a better process for identifying when they needed to be back in the clinic room to take notes and audio-record, so that they could complete other work assignments while waiting.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1 Discussion

We asked questions about the number of patients provided with the service, levels of decisional self-efficacy and decisional conflict among survey respondents, and aspects of program design that should be continued, discontinued, or modified.

Study Question 1

We found that 278 patients were provided with CPRS over the study period, compared to our CPRS capacity in that period of 880, a service exploitation rate of 32%. On one hand, we were pleased that this novel and complex program reached 278 patients over 22 months. On the other hand, we were concerned that we were not able to serve more patients. We were also concerned that our initial design, which relied on record-keeping by overloaded schedulers, did not generate adequate records of recruitment. Therefore we could not tell whether our program was under-utilized due to poor recruitment or whether many patients were declining the service.

We also learned that the relatively low exploitation rate of 32% meant that our CPRS staff, the premedical interns, were not working at capacity. Meanwhile the new patient schedulers were overloaded. While in theory the new patient schedulers are the ideal people to offer and schedule CPRS for patients visiting our clinic, in practice we concluded that we need to balance the workload across CPRS staff and new patient schedulers.

Study Question 2

In a convenience sample of respondents, Consultation Planning was associated with improvements in pre/post measures of decisional self-efficacy, and CPRS in conjunction with the doctor’s visit was associated with a reduction in decisional conflict. Due to constraints in our study design, namely that we agreed to physician requests not to disrupt the clinic workflow, we were only able to approach and consent 13% of the CPRS service recipients. Therefore we interpret these findings as preliminary findings that helped us pilot two promising program evaluation measures. Our findings of improvement are in line with other studies that have examined the effect of decision support on and decisional conflict [20]. We learned that patients in our sample had a relatively high baseline level of decision self-efficacy, 3.24, which constrains the amount of improvement we can detect. At the same time, the standardized effect size for decision self efficacy was large, 0.85, and indicates that decision self-efficacy, having established good psychometric properties of reliability and validity, may also be sensitive to this intervention.

Patients in our sample started with an average decisional conflict score of 2.78, which is consistent with people at risk for delaying decisions due to their confusion about which course of action is best. After seeing their doctors and receiving the CPRS intervention, decisional conflict levels had fallen to 2.03, which is consistent with people making and following through on decisions [16]. We therefore learned that the direction and magnitude of change in decisional conflict is consistent with the instrument’s norms, and that it may be worthwhile to use this outcome measure in further studies of CPRS.

Study Question 3

Overall, physicians, schedulers, and patients endorsed continued implementation of CPRS. Physicians felt that the primary benefit for them was getting a preview of patient questions and concerns as a result of the Consultation Planning process. Physicians recognized that patients also appreciated each of the CPRS components, and thus were willing to cooperate with the process. However, physicians did not want clinic processes (e.g. rooming patients) to be affected by CPRS.

CPRS staff members experienced one of the implications of physician reluctance to modify clinic processes in order to accommodate CPRS. Physicians often run behind schedule. The CPRS staff would time their first intervention, Consultation Planning, to conclude at the time the medical appointment was due to begin. If the physician was running late, the CPRS staff member faced an uncertain waiting period before the next interventions, Consultation Recording and Summarizing, were due to begin. The physicians, running late, could not be counted on to come and get the CPRS staff member from their desk in a clinic back office. So CPRS staff members would wait in the hallway to intercept the physician dashing from the one exam room to the next. This led to unproductive waiting.

Schedulers were caught in an organizational bind. They had agreed, during needs assessment and program redesign interviews, with the practice manager’s suggestion that they offer CPRS. As a result, the practice manager added CPRS scheduling to their job descriptions. But because of competing demands on their time, the schedulers could only schedule approximately 32% of CPRS capacity. One of the schedulers insisted that they all wanted to offer CPRS more often, but explained during a monthly meeting with the Decision Services team, “My other tasks are higher priority. I will get written up in a flash if I don’t call a patient back or have patient materials ready when they’re needed.” The scheduler was referring to written complaints lodged by supervisors or physicians in cases of non-performance of critical duties.

4.2 Conclusion

Our CPRS implementation was successful in delivering evidence-based interventions to 278 breast cancer patients over a 22 month period. The implementation can be enhanced with changes in the program’s screening, recruitment and scheduling processes; locations; delivery; products; and techniques for productive use of staff waiting times.

4.3 Practice Implications

As suggested by new patient schedulers, we have diverted some of our CPRS staff time, which was underutilized due to unscheduled slots, to engage in screening, qualifying, and recruiting patients for CPRS. As a result, in 2007 we operated at 51% exploitation of our CPRS capacity, up from 32% during the study period.

In order to collect more complete data on the CPRS implementation, we have now sought and obtained a waiver of consent from our Institutional Review Board so that in the future we may survey CPRS patients routinely without disrupting the clinic workflow.

In order to eliminate the use of clinic exam rooms for CPRS, as requested by physicians, we have identified reservable rooms around the Cancer Center where we conduct Consultation Planning. We are also beginning to investigate the effects of providing Consultation Planning over the telephone so that the CPRS staff does not encounter space limitations and so that patients do not need to come into clinic 60–90 minutes early.

In response to physician concerns about the length and detail of the documents generated by our program, we have modified our training to emphasize paraphrasing and summarizing techniques so that CPRS staff are able to limit Consultation Plans to 2 pages and Consultation Summaries to 2–3 pages.

Physicians did not always have enough time to review every CPRS document, so we have worked with our institution’s Risk Management department to create a disclaimer that makes it clear that our summaries and recordings are provided as a convenience and may contain errors and omissions.

In order to address CPRS staff requests that their wait times be more productive, we are experimenting with giving patients radio devices and asking them to page their CPRS staff member to come take notes and audio-record the visit, as soon as the physician arrives for the medical appointment.

Based on the findings from this study, and other investigations, the Agency for Health Research and Quality has featured our implementation of CPRS as one of the first 100 Innovation Profiles in its Innovation Exchange [21]. The entry in the Innovation Exchange describes additional features and lessons learned from this implementation.

In addition to training premedical interns to provide CPRS at UCSF, we have trained cancer resource center employees and volunteers around Northern California to offer CPRS, with promising results for patients and CPRS staff [22] We continue our search for what is effective and sustainable in translating into practice the growing body of research about visit preparation, audio-recording, and summarizing. We invite inquiries and collaboration on these topics.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding

The Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making (grant 0015) and United States Department of Defense (DAMD17-03-0481) provided funding for this study. During the analysis and reporting phase of the study, Dr. Belkora was also supported by a career development award from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH), grant number 5 K12 HD052163. The funding sources had no involvement in any aspect of the study.

The authors wish to thank the patients, physicians, administrators, premedical interns, and employees of the UCSF Breast Care Center. We also thank Karen Sepucha for ongoing collaboration related to decision support at our Breast Care Center; Martha Daschbach for assistance with regulatory compliance; the staff of the Fishbon Library for research assistance; Pam Derish for scientific writing instruction; and Dan Moore for statistical advice.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jeffrey K. Belkora, University of California, San Francisco.

Meredith K. Loth, University of California, San Francisco

Daniel F. Chen, University of California, San Francisco

Jennifer Y. Chen, University of California, San Francisco

Shelley Volz, University of California, San Francisco

Laura J. Esserman, University of California, San Francisco

References

- 1.Weiss M. Seven minutes! How to get the most from your doctor visit. New York: Western Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott JT, Harmsen M, Prictor MJ, Entwistle VA, Sowden AJ, Watt I. Recordings or summaries of consultations for people with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:CD001539. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kinnersley P, Edwards A, Hood K, Cadbury N, Ryan R, Prout H, Owen D, Macbeth F, Butow P, Butler C. Interventions before consultations for helping patients address their information needs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD004565. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004565.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belkora JK. PhD Dissertation in Department of Engineering-Economic Systems & Operations Research. Stanford University; Stanford, CA: 1997. Mindful collaboration: Prospect mapping as an action research approach to planning for medical consultations; p. 302. http://wwwlib.umi.com/dxweb/gateway. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sepucha K, Belkora J, Tripathy D, Esserman L. Building bridges between physicians and patients: Results of a pilot study examining new tools for collaborative decision making. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1230–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.6.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sepucha K, Belkora J, Mutchnick S, Esserman L. Consultation planning to help patients prepare for medical consultations: Effect on communication and satisfaction for patients and physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2695–2700. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butow PN, Dunn SM, Tattersall MH, Jones QJ. Patient participation in the cancer consultation: Evaluation of a question prompt sheet. Ann Oncol. 1994;5:199–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford S, Fallowfield L, Hall A, Lewis S. The influence of audiotapes on patient participation in the cancer consultation. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:2264–9. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00336-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sepucha KR, Belkora JK, Tripathy D, Esserman LJ. Building bridges between physicians and patients: Results of a pilot study examining new tools for collaborative decision making in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1230–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.6.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sepucha KR, Belkora JK, Mutchnick S, Esserman LJ. Consultation planning to help breast cancer patients prepare for medical consultations: Effect on communication and satisfaction for patients and physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2695–700. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aviv C, Sepucha K, Belkora J, Esserman L. Using action research to improve collaboration between breast cancer patients and physicians: Creating the program for collaborative care. In: Kronenfeld J, editor. Research in the sociology of health care: Changing consumers and changing technology in health care and health care delivery. New York: Elsevier Science; 2001. pp. 207–229. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sepucha K, Belkora J, Aviv C, Mutchnik S, Esserman L. Improving the quality of decision making in breast cancer: Consultation planning template and consultation recording template. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30:99–106. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.99-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sepucha K, Belkora J. Putting shared decision making to work in breast and prostate cancers: Tools for community oncologists. Commun Oncol. 2007;4:685–689. 691. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belkora J. Decision services reference guide. San Francisco, CA: 2007. http://www.guidesmith.org/ds-reference-guide. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cranney A, O’Connor AM, Jacobsen MJ, Tugwell P, Adachi JD, Ooi DS, Waldegger L, Goldstein R, Wells GA. Development and pilot testing of a decision aid for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;47:245–55. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00218-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Connor AM. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making. 1995;15:25–30. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ottawa Health Research Institute. [Accessed on: July 22, 2004];User manual for decision self-efficacy. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/eval.html.

- 18.Ottawa Health Research Institute. [Accessed on: July 22, 2004];User manual for decisional conflict. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/eval.html.

- 19.Flanagan JC. The critical incident technique. Psychol Bull. 1954;51:327–58. doi: 10.1037/h0061470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Connor AM, Stacey D, Entwistle V, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Rovner D, Holmes-Rovner M, Tait V, Tetroe J, Fiset V, Barry M, Jones J. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.AHRQ Health Care Innovations Exchange, Innovation profile: Personalized support improves patient-physician communication and enhances decision making for breast cancer patients. [Accessed on: May 2, 2008];AHRQ Health Care Innovations Exchange. [Web site]. http://www.innovations.ahrq.gov.

- 22.Belkora J, Edlow B, Aviv C, Sepucha K, Esserman L. Training community resource center and clinic personnel to prompt patients in listing questions for doctors: Follow-up interviews about barriers and facilitators to the implementation of consultation planning. Implementation Science. 2008;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]