Abstract

Calcium imaging using fluorescent reporters is the most widely used optical approach to investigate activity in intact neuronal circuits with single-cell resolution. Calcium signals, however, are often difficult to interpret, especially if the desired output quantity is membrane voltage or instantaneous firing rates. Combining dendritic intracellular electrophysiology and multi-photon calcium imaging in vivo, we recently investigated the relationship between optical signals recorded with the fluorescent calcium indicator Oregon Green BAPTA-1 (OGB-1) and spike output in principal neurons in the locust antennal lobe. We derived from these experiments a simple, empirical and easily adaptable method requiring minimal calibration to reconstruct firing rates from calcium signals with good accuracy and 50-ms temporal resolution.

Keywords: calcium imaging, spiking, two-photon microscopy, dendrites, olfaction

Despite the wide availability of optical voltage reporters to estimate activity in intact neuronal circuits with single-cell resolution (Chanda et al., 2005; Cohen et al., 1978; Ferezou et al., 2006; Nuriya et al., 2006; Obaid et al., 1999; Sjulson and Miesenbock, 2006; Zhou et al., 2007), calcium imaging using fluorescent reporters (Denk and Svoboda, 1997; Helmchen and Waters, 2002; Smetters et al., 1999; Tsien, 1999; Yuste and Katz, 1991) remains the most used optical approach to achieve similar goals. The robustness of exogenous and endogenous labeling with calcium reporters and the minimal impact they have on neuronal viability make them, in principle, excellent tools to probe activity at the level of neuron populations, single neurons, or single sub-cellular compartments (e.g., dendrites, spines, presynaptic boutons). The availability of genetically engineered calcium indicators (Mank and Griesbeck, 2008; Miyawaki et al., 1997, 1999; Reiff et al., 2005) and the possibility of controlling their selective expression (Feng et al., 2000; Hebert and McConnell, 2000; Jefferis et al., 2001, 2007; Zong et al., 2005) reinforce their use and promise. Despite important remaining issues related to indicator response kinetics (see below), the constant refinement of fluorescent calcium indicator proteins (Garaschuk et al., 2007; Mank et al., 2006; Mao et al., 2008; Wallace et al. 2008), combined with improvements in optical microscopy techniques (Deisseroth et al., 2006; Dombeck et al., 2007; Engelbrecht et al., 2008; Holekamp et al., 2008; Llewellyn et al., 2008) makes calcium imaging a major tool to elucidate activity and function in neuronal circuits (Carlsson et al. 2005; Friedrich and Korsching, 1997; Galizia et al., 1999; Holekamp et al., 2008; Ohki et al., 2005; Sobel and Tank, 1994; Spors et al., 2006; Tabor et al., 2008; Wachowiak and Cohen, 2001; Wang et al. 2003, 2004). Often deemphasized, however, is the fact that calcium signals are not always straightforward to interpret, especially if the desired output quantity is membrane voltage or instantaneous firing rates. This study (and its source, Moreaux and Laurent, 2007) proposes a simple empirical method to estimate instantaneous firing rates of single neurons from fluorescence signals obtained in vivo, using the calcium indicator Oregon Green BAPTA-1.

Problems Arising When Converting Calcium Signals into Voltage or Firing Rates

In the study of neuronal systems, signals from calcium indicators are, given an appropriately selected indicator with adequate calcium sensitivity, usually interpreted as indicating spiking activity; whereas calcium signals and voltage are generally indeed correlated, calcium signals can also be generated by sub-threshold voltage events or influx through ionotropic ion channels (Goldberg et al., 1999; Kovalchuk et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2007; Perez-Reyes, 2003; Soler-Llavina and Sabatini, 2006). Conversely, an indicator's sensitivity may not be matched to the firing statistics of the neurons under study. Correctly interpreting a calcium signal – being in a position to separate synaptic inputs from spike output for example, or estimating the fraction of spike output detected – thus depends on a judicious match between the indicator's sensitivity and the properties of the neurons under study. Often, this match is difficult or impossible to optimize, for lack of information on the neurons sampled, or for lack of prior testing, especially in the precise conditions in which imaging will be used (the operating range of neurons can differ dramatically between in vitro and in vivo conditions, for example). This match becomes increasingly important as the desired temporal resolution of activity estimates approaches the temporal scale of single action potentials. We note that neuronal activity often consists simply of modulations around baselines rates (themselves sometimes elevated, e.g., 30 spikes/s, or as low as 0) to instantaneous peaks up to several hundred spikes/s. In short, one should be both careful and realistic about what can be reasonably achieved.

To make possible a reasonable extraction of spiking activity, the relationship between calcium signals and voltage should be carefully addressed in a neuron-specific manner. We believe that this is fundamental for a correct functional interpretation of imaging data. Plainly, the functional calibration of indicators should be done in the cell type in which calcium will later be used as a substitute for electrical recordings, and ideally, in the same physiological conditions. Such conditions are harsh, probably even sometimes impossible. Yet, if we do not keep in mind their necessity, we run the risk of having to later re-interpret calcium-imaging data, causing unnecessary revisions.

Recently, the correspondence between odor-evoked, somatic and dendritic calcium signals and spike output has been evaluated in vivo in Drosophila projection neurons (PNs) expressing the genetically encoded calcium reporter G-CaMP 1.3 (Jayaraman and Laurent, 2007). A recent investigation combining calcium imaging and voltage recordings in a nose and brain preparation of Xenopus laevis revealed the underestimated cell-specificity of the correlation between spontaneous and odor-evoked spiking activity and mitral and granule cells' somatic calcium signals (Lin et al., 2007). In vivo somatic calcium signals were combined with simultaneous voltage recordings in anesthetized rats to identify temporally sparse spontaneous activity (∼1 Hz) and compared to somatic calcium recordings alone in awake animals (Greenberg et al., 2008). Spiking activity was restricted to single action potentials or short bursts; an original template-matching method (Greenberg et al., 2008, SI) applied to the calcium signal alone successfully extracted spike times with good accuracy. In adult zebrafish brain and nose explants, in a study combining soma calcium-signal and voltage recordings, Yaksi and Friedrich (2006) used a deconvolution method to extract spiking activity of sensory neurons stimulated with odors. The method assumed that each action potential gives rise to a stereotyped somatic calcium transient with mono-exponential decay over time, and that calcium summation caused by a train of action potentials is described well by a simple convolution of a mono-exponential kernel with the spike-train. This approach gave good firing-rate reconstructions with image sampling rates of ∼30 Hz on neuronal populations of adult zebrafish (Tabor et al., 2008; Yaksi and Friedrich, 2006), a remarkable achievement.

Note that most past attempts to extract spiking activity from single neurons have been performed using the fluorescence of calcium indicators recorded at the soma. In invertebrates such as insects, spike-related calcium/fluorescence transients are usually smaller from the soma (sometimes even absent, as in locust PNs; Moreaux and Laurent, 2007) than from dendrites; importantly, they can also be slower (∼1 s vs. ∼50 ms, decay times), making the capture of neuronal firing modulation questionable. Usually neurons' somata are spread out in space (more so in larger brains) hindering the capture of a complete neuronal population, even with fast scanning imaging techniques (Göbel et al. 2007; Holekamp et al., 2008; Reddy et al., 2008), and imposing non-ideal trade-offs between spatio-temporal resolution and signal/noise. Each approach should thus be tailored to its experimental system; all methods do not fit all experimental and biological situations. Here we focus on one system, the locust olfactory system, and propose an easily modified method to extract firing-rate estimates from calcium-dendritic signals recorded in vivo using the common calcium indicator OGB-1.

Dendritic Calcium Imaging in Early Olfactory Circuits

The early olfactory system – olfactory bulb (vertebrates) or antennal lobe (insects) – with its well organized glomerular anatomy offers a beautiful opportunity to use dendritic calcium imaging to help decipher basic rules of sensory processing (Buck and Axel, 1991; Hallem et al., 2004; Mombaerts et al., 1996; Vosshall et al., 2000). In the exploration of such a sensory system, intrinsic and calcium imaging of glomeruli have been used in vivo to investigate spatio-temporal activity patterns of input, output and local neurons. Typically, imaging of glomeruli using various kinds of fluorescent calcium indicators has been used as a proxy for electro-physiological recordings (Carlsson et al., 2005; Fried et al., 2002; Friedrich and Korsching, 1997; Galizia et al., 1999; Sachse and Galizia, 2002; Spors et al., 2006; Wachowiak and Cohen, 2001; Wang et al., 2003). An important point to elucidate in insect antennal lobe circuits is the true relationship between spike output and imaging data in PNs, the antennal lobe's sole output. We address this issue in locust, combining dendritic voltage recordings and two-photon calcium imaging in vivo during odor stimulation in intact, non-anesthetized animals (Figure 1). Our goal was to identify the main causes of calcium signal fluctuations, to determine whether calcium signals might be used to estimate PNs spike output, and if so, with what accuracy.

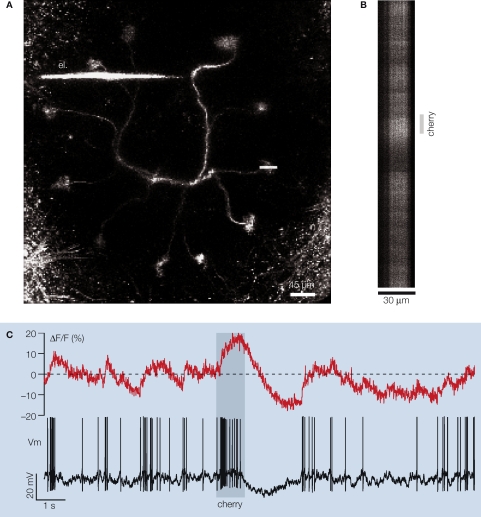

Figure 1.

In vivo simultaneous dendritic voltage recordings and two-photon calcium imaging in the locust projection neuron. (A) A frontal view of a PN labeled from a secondary dendrite via a microelectrode (el.) filled with the fluorescent calcium indicator OGB-1. Eleven of the PN's 12 glomerular tufts can be seen, forming a circle in one plane. The soma and axon of the neuron are respectively above and below the dendritic plane (not included in this view). Shortly after dendritic impalement, one of the several tufts of the PN is selected for fluorescence imaging (horizontal white line). Calcium signal is then acquired simultaneously with voltage across the glomerular tuft using a line scan (typically 30 μm × 24 s). (B) Example of a single 16 s-long line-scan trial during odor presentation [different PN from that in (A)]. (C) Glomerular calcium ΔF/F integrated along the scanned line [500 Hz sampling, PN in (B)] and simultaneous intracellular membrane potential Vm (15 kHz sampling). Stippled line: average baseline fluorescence before odor presentation to the animal. Note the complex modulations of the calcium signal and their relationship to voltage.

Locust PNs are multiglomerular neurons, with projections to 10 or so individual glomeruli (∼30 μm diameter each). The adult locust antennal lobe contains about 1,000 glomeruli, distributed in a sphere of about 300 μm diameter. The glomeruli visited by individual PNs, however, always lie in a plane. By correctly orienting the preparation, all the glomeruli of a stained PN can thus be observed in one plane of focus. The planes defined by all PNs are parallel to one another. For our experiments, a fine borosilicate micropipette was back-filled with OGB-1, gently advanced into the neuropil and used to impale one PN, usually in its principal omega-shaped dendrite, or in a secondary dendrite close to a glomerular tuft (Figure 1A). Recordings could often be held for several tens of minutes. Odors were presented to the animal in 1 s long pulses, and 24 s of calcium-indicator and intracellular-voltage data were collected (500 Hz image sampling) around the odor stimulus pulse (early fragment shown in Figures 1B,C). Our data thus contained long epochs of baseline activity, stimulus-evoked responses and recovery periods. PN electrical activity recorded in these experiments was identical (baseline activity; response characteristics; peak firing rates; range of response types; oscillatory activity) to that previously described, using different recording methods (soma intracellular recordings: Laurent and Davidowitz, 1994; Laurent et al., 1996; tetrode extracellular recordings: Mazor and Laurent, 2005; Perez-Orive et al., 2002).

The Multiple Components of the Glomerular Dendritic Calcium Signal

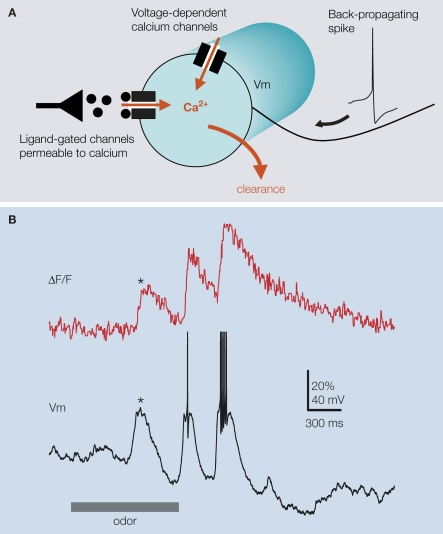

Locust PN dendritic calcium signals are composed of multiple, distinct components. Our experiments suggested that at least three factors (Figure 2A) contribute to the variation of calcium in a glomerular dendrite (Moreaux and Laurent, 2007): calcium transients triggered by action potentials, voltage-dependent calcium entry caused by sub-threshold depolarization, and calcium clearance. First, we observed that a single action potential always produced a detectable calcium increase; single-spike calcium decay time was fast (∼50 ms) after pharmacological blockade of nicotinic-Ach-receptor mediated synaptic input, but slower and non-stereotyped (variable across the glomerular dendrites of a single PN for example) in intact conditions. Spike trains always led to a calcium signal summation. Second, spontaneous or stimulus-evoked sub-threshold depolarizations caused, from a membrane voltage of about −60 mV, a detectable calcium signal (Figure 2B). While insect nicotinic receptors are known to be calcium permeable, much of this sub-threshold calcium signal seemed to be voltage-dependent, for it could be reproduced simply by depolarizing-current injection. By contrast with observations from somatic imaging, calcium clearance after summation in the dendrite was not necessarily mono-exponential. This might be due to local hyper-polarizing inputs from inhibitory pathways. Because these multiple contributions to the calcium signal sampled may interact in complicated (or at least poorly understood) ways, the extraction of a PN spike output is clearly not a straightforward exercise, especially if attaining single-spike resolution is required. We now summarize an empirical method for instantaneous firing-rate estimation, based on the above data and knowledge.

Figure 2.

Projection neuron dendritic calcium signals have multiple components as illustrated in (A) with a simple schematic of a PN-glomerular dendritic compartment (circle). The majors sources of calcium variation are back-propagating spikes triggering fast calcium transients trough high-threshold voltage-dependent calcium-channels, sub-threshold depolarizing activity (through low-activated voltage-dependent calcium-channels, possibly also by activation of calcium-permeable ligand-gated channels), and clearance. (B) Calcium signals are not always correlated with spiking. Simultaneous fluorescence and voltage PN-recording illustrates the occurrence of spike-independent components in the glomerular signal. Odor-evoked depolarizing synaptic input to the PN marked (*) can produce a significant calcium elevation in the absence of spike.

A Simple Method to Estimate Spike Output from Dendritic Calcium Signals

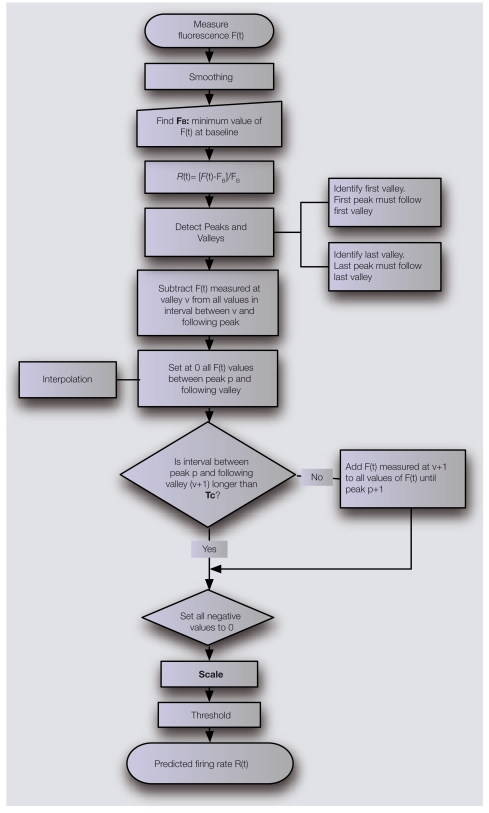

Having access to simultaneously recorded voltage and fluorescence, we investigated (Moreaux and Laurent, 2007) whether a PN's firing rate could be extracted from its glomerular calcium signal recorded at high sampling rate (500 Hz) using empirically derived routines selective for spike-dependent signals. The goal was to transform the fluorescence of the calcium indicator into spiking activity, using consistent rules and ultimately, a small number of experiment-specific measurements that require no physiological recording. We managed to estimate a PN's firing activity with a 50-ms time resolution from a single fluorescence recording, using one experiment-specific parameter and a minimal neuron-specific calibration. In its principle, our estimation method relies on two assumptions: (1) when calcium summation occurs, the intracellular calcium value is linearly related to the average firing rate of the spike-train causing calcium integration, and (2) calcium decays are due either to cessation of firing or to inhibition. With this in mind, the main steps of our algorithm are the following (see flowchart in Figure 3). A fluorescence single trial is smoothed with a Gaussian filter, to “enhance” the fluorescence plateaus (or peaks) and the end of the fluorescence-decays (called valleys). The level of fluorescence representing the absence of firing at baseline (FB, see Figure 4) needs to be determined, so that the assumed linear relationship between the optical signal and firing can be used. FB is the rest value of the spike-independent components, due mainly to net, depolarizing synaptic bombardment. The fluorescence trace is then normalized to this value. Then, peaks and valleys are detected to define segments of activity. Practically, one has to check that the first peak of the recording comes after the first valley and the last peak comes after the last valley. The value read for a given valley is then subtracted from all following fluorescence values, until the next peak is reached. This step sets all the ends of decay to 0 and guarantees a coherent proportionality between the normalized fluorescence and the actual firing rate while not yet accounting for calcium summation. The values from a peak to the next valley are reset to 0 using a simple Gaussian-decay function. Calcium summation is now taken into consideration by comparing the time interval between a valley and the previous peak to a characteristic time, Tc, the duration over which spike-evoked calcium summation is not relevant. If this time interval <Tc, summation must be factored in: the valley value is added to the following values until the next peak. Only positive values of the reconstruction are kept and scaling is applied. Setting a threshold around the average spontaneous spiking activity filters out large time-resolved synaptic events.

Figure 3.

Simple algorithm used to transform the measure of a calcium indicator fluorescence F(t) into a prediction of the firing rate R(t). The algorithm relies on the determination of two parameters: a time parameter Tc and a scaling factor S specific to the indicator and to the cell type under investigation.

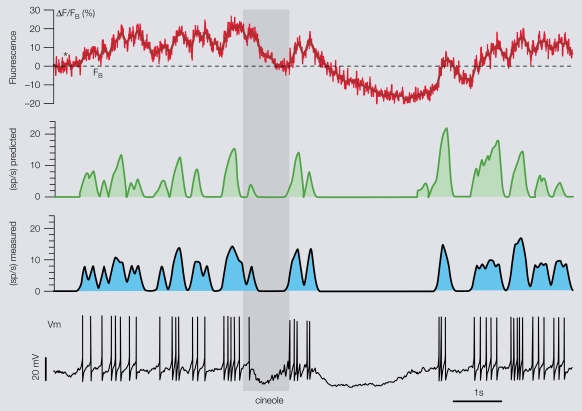

Figure 4.

Calibration of our method with paired imaging and electrophysiology. The determination of the neuron-type/indicator's two specific parameters (Tc, S) is done by optimizing the match between measured firing rate (blue trace, 50-ms Gaussian smoothing) obtained from intracellular trace (Vm) and predicted smoothed firing rate (green trace) reconstructed from the calcium trace (red) using the simple rules describe in the text. For the specific PN/OGB-1 combination, the two calibration parameters were extracted from only five 16 s-long single trials with 1 s odor presentations on different PNs. Stippled line (fluorescence trace) indicates FB, the only experiment-specific measurement.

Two Calibration Parameters (Tc and S)

A mapping between calcium signals and voltage (or firing rates) appropriate for integrative studies is probably attainable, regardless of the methodology, only if some prior calibration steps have been carried out in the same preparation and experimental conditions. In practice, because simultaneous voltage and calcium recordings in vivo in non-anesthetized animals tend to be difficult, the calibration steps should be as limited as possible. Our method relies on the knowledge of three parameters. The first, FB (see Figure 4), is experiment-specific and requires no prior calibration (i.e., no paired imaging and electrophysiology). The other two (time parameter, Tc, and scaling factor, S), are the only two parameters requiring calibration through prior paired imaging and electrophysiology. With locust PNs and the calcium indicator OGB-1, these two parameters could be estimated satisfactorily from paired simultaneous voltage and calcium recordings in five different animals and by optimizing the overall fit between predicted (from calcium signal) and measured (with a microelectrode) firing rates (Figure 4).

Once the calibration done, our method was applied to predict PN firing patterns from calcium signals, using different paired recordings as tests. We obtained ∼80–90% mean accuracy. In each experiment, FB was the only experiment-specific parameter required (Figure 5).

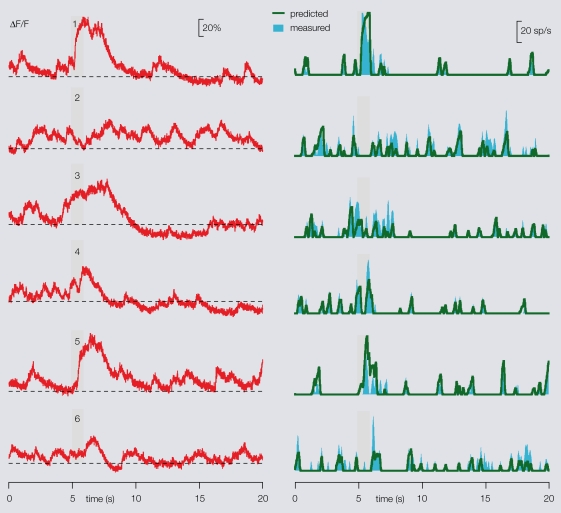

Figure 5.

Prediction of a PN's firing profiles from its dendritic calcium signals. After the specific PN/OGB-1 calibration, the algorithm may be applied to single PN-odor calcium imaging alone, baseline FB being the only trial-specific parameter, as illustrated here. Left: raw fluorescence traces recorded from one PN in response to six different odors (stimulus during gray bar). Stipple line indicates FB for each trial. Right: predicted (from left, green) and measured (cyan) smoothed firing rates. An overall 80–90% mean accuracy is obtained.

Sources of Variability

When exogenous calcium indicators are used, a key issue for firing-rate-estimate accuracy is the consistency of cytoplasmic concentration of the indicator across experiments. With bolus loading techniques, great care (usually acquired after much practice) is required to minimize inter-experiment variations. With multi-cellular labeling, spatial gradients of calcium indicator concentrations may clearly create problems (Göbel and Helmchen, 2007). The time and scaling parameters are related to the calcium-buffering capacity added to the neuron's own by the indicator. In our hands, following strict experimental procedures, the across-experiment variance of the time parameter Tc was very small (∼5%). The major source of error originated from the variance of the scaling parameter, due to a deviation from the assumed linearity between calcium elevation and firing rate. There are at least two distinct potential sources of non-linearity: (1) from the fluorescent calcium indicator itself and (2) from intrinsic cellular properties. The latter especially makes defining a ceiling an empirical issue. With locust PNs and OGB1, we observed that the deviation from linear prediction was usually small for short-lived bursts of high-firing rate (PNs rarely fire at rates >60 sp/s), but larger (and always and underestimate) during prolonged periods of firing, presumably due to a contribution of sustained synaptic inputs and sub-linear summation with spike-related calcium entry. Under pharmacological blockade of synaptic input (in conditions admittedly without much use for network issues), the variance of the scaling factor S was consistent with that of the time parameter measured in normal in vivo condition. Non-linear summation of spike-related events at high-firing rates and the superposition of sub-threshold and spike-dependent components, presumably non-linear, are probably responsible for the variance of the scaling factor.

Choosing the Right Method

If activity is sparse and stereotyped (e.g., short burst of few action potentials), if calcium decay time is shorter than the minimum inter-spike (or burst) interval, and if the correlation between calcium elevation and spiking has been properly established in a cell-specific manner (see Lin et al., 2007 for a warning), then template-matching methods applied to somatic calcium signals can provide a good estimate of the “on/off” state of a single or population of neurons (Greenberg et al. 2008). In the presence of sustained spiking activity, as in sensory receptor neurons for example, the task of estimating firing rates from calcium signals can be more delicate. The deconvolution approach of Yaksi and Friedrich (2006) assumes that spike-related calcium-transients are stereotyped. Deconvolution is performed in the frequency domain, as a high-pass filter applied to the de-noised calcium spectrum. A calibration step requires the determination of the average filter parameters from simultaneous voltage and calcium recordings. Like all inverse problems, this method is very sensitive to signal-to-(high-frequency) noise ratio. It is also computationally intensive. Finally, the required stereotypy of calcium decay is probably met mainly when fast calcium fluctuations are damped, as expected in somata. Our approach is the opposite. No assumption is made about calcium decays associated with interruptions of firing. We impose a simple reset of those segments, detected in the time domain, and take calcium summation into account following a very simple rule. This method is computationally trivial and less sensitive to noise: we detect extrema rather than invert matrices in the frequency domain. Reconstruction accuracy is ∼80–90% on average – i.e., comparable to Yaksi and Friedrich's method (2006) – using raw calcium signals recorded at dendritic sites. The simplicity of the approach should be an advantage if large datasets are to be analyzed. The counterpoint is that our method so far rests on acquiring fast/dendritic calcium signals. Those are potentially well suited for systems such as the olfactory bulb and antennal lobe, where processing occurs in compact glomeruli. How the method fares in different systems, where dendrites are more widespread, remains to be tested

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Key Concept

- Calcium reporter/indicator

molecule emitting a fluorescence signal that is modulated by the binding/unbinding of calcium ions.

- Firing rate reconstruction

mathematical operations allowing the transformation of intracellular calcium variations into estimates of firing rates.

- Two-photon imaging

optical technique allowing imaging of endogenous or exogenous fluorescent molecules in cellular compartments in vivo in a non-invasive manner.

Biographies

Laurent Moreaux was born in 1973 in France. After obtaining an optoelectronic engineering degree at the University Paris XI (Orsay) and an undergraduate degree at the Institut d'Optique (Orsay), he did his Ph.D. in physics with Jerome Mertz investigating second harmonic microscopy. After a postdoctoral scholar position at Caltech with Gilles Laurent (from 2002 to 2004), exploring the use of optics to measure neuronal activity in insects, he obtained a CNRS junior position at the Université Paris Descartes where he is currently focusing his research on the development and use of optical techniques to probe neuronal activity at spike-time resolution.

Laurent Moreaux was born in 1973 in France. After obtaining an optoelectronic engineering degree at the University Paris XI (Orsay) and an undergraduate degree at the Institut d'Optique (Orsay), he did his Ph.D. in physics with Jerome Mertz investigating second harmonic microscopy. After a postdoctoral scholar position at Caltech with Gilles Laurent (from 2002 to 2004), exploring the use of optics to measure neuronal activity in insects, he obtained a CNRS junior position at the Université Paris Descartes where he is currently focusing his research on the development and use of optical techniques to probe neuronal activity at spike-time resolution.

Gilles Laurent obtained his Doctorate in Veterinary Medicine and a PhD in Neuroethology in 1985–86 from (respectively) the National Veterinary School and the Paul Sabatier University in Toulouse (France). He did postdoctoral studies in Malcolm Burrows's group at the University of Cambridge between 1985 and 1989, and moved to Caltech in 1990, where he is now Hanson Professor of Biology. In 2009, he will be moving to Frankfurt as a Director at a new Max-Planck-Institute for Brain Research. His research interests are in network dynamics and coding, with an experimental focus on small nervous systems (insects, fish, reptiles).

Gilles Laurent obtained his Doctorate in Veterinary Medicine and a PhD in Neuroethology in 1985–86 from (respectively) the National Veterinary School and the Paul Sabatier University in Toulouse (France). He did postdoctoral studies in Malcolm Burrows's group at the University of Cambridge between 1985 and 1989, and moved to Caltech in 1990, where he is now Hanson Professor of Biology. In 2009, he will be moving to Frankfurt as a Director at a new Max-Planck-Institute for Brain Research. His research interests are in network dynamics and coding, with an experimental focus on small nervous systems (insects, fish, reptiles).

References

- Buck L., Axel R. (1991). A novel multigene family may encode odorant receptors: a molecular basis for odor recognition. Cell 65, 175–187 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90418-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson M. A., Knusel P., Verschure P. F., Hansson B. S. (2005). Spatio-temporal Ca2+ dynamics of moth olfactory projection neurones. Eur. J. Neurosci. 22, 647–657 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04239.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanda B., Blunck R., Faria L. C., Schweizer F. E., Mody I., Bezanilla F. (2005). A hybrid approach to measuring electrical activity in genetically specified neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1619–1626 10.1038/nn1558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L. B., Salzberg B. M., Grinvald A. (1978). Optical methods for monitoring neuron activity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1, 171–182 10.1146/annurev.ne.01.030178.001131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisseroth K., Feng G., Majewska A. K., Miesenböck G., Ting A., Schnitzer M. J. (2006). Next-generation optical technologies for illuminating genetically targeted brain circuits. J. Neurosci. 26, 10380–10386 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3863-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denk W., Svoboda K. (1997). Photon upmanship: why multiphoton imaging is more than a gimmick. Neuron 18, 351–357 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81237-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombeck D. A., Khabbaz A. N., Collman F., Adelman T. L., Tank D. W. (2007). Imaging large-scale neural activity with cellular resolution in awake mobile mice. Neuron 56, 43–57 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht C. J., Johnston R. S., Seibel E. J., Helmchen F. (2008). Ultra-compact fiber-optic two-photon microscope for functional fluorescence imaging in vivo. Opt. Express 16, 5556–5564 10.1364/OE.16.005556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng G., Mellor R. H., Bernstein M., Keller-Peck C., Nguyen Q. T., Wallace M., Nerbonne J. M., Lichtman J. W., Sanes J. R. (2000). Imaging neuronal subsets in transgenic mice expressing multiple spectral variants of GFP. Neuron 28, 41–51 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00084-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferezou I., Bolea S., Petersen C. C. H. (2006). Visualizing the cortical representation of whisker touch: voltage-sensitive dye imaging in freely moving mouse. Neuron 50, 617–629 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried H. U., Fuss S. H., Korsching S. I. (2002). Selective imaging of presynaptic activity in the mouse olfactory bulb shows concentration and structure dependence of odor responses in identified glomeruli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 3222–3227 10.1073/pnas.052658399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich R. W., Korsching S. I. (1997). Combinatorial and chemotopic odorant coding in the zebrafish olfactory bulb visualized by optical imaging. Neuron 18, 737–752 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80314-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galizia C. G., Sachse S., Rappert A., Menzel R. (1999). The glomerular code for odor representation is species specific in the honeybee Apis mellifera. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 473–478 10.1038/8144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaschuk O., Griesbeck O., Konnerth A. (2007). Troponin C-based biosensors: a new family of genetically encoded indicators for in vivo calcium imaging in the nervous system. Cell Calcium 42, 351–361 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göbel W., Helmchen F. (2007). In vivo calcium imaging of neural network function. Physiology (Bethesda) 22, 358–365 10.1152/physiol.00032.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göbel W., Kampa B. M., Helmchen F. (2007). Imaging cellular network dynamics in three dimensions using fast 3D laser scanning. Nat. Methods 4, 73–79 10.1038/nmeth989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg F., Grunewald B., Rosenboom H., Menzel R. (1999). Nicotinic acetylcholine currents of cultured Kenyon cells from the mushroom bodies of the honey bee Apis mellifera. J. Physiol. 514, 759–768 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.759ad.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg D. S., Houweling A. R., Kerr J. N. (2008). Population imaging of ongoing neuronal activity in the visual cortex of awake rats. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 749–751 10.1038/nn.2140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallem E. A., Ho M. G., Carlson J. R. (2004). The molecular basis of odor coding in the Drosophila antenna. Cell 117, 965–979 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert J. M., McConnell S. K. (2000). Targeting of cre to the Foxg1(BF-1) locus mediates loxP recombination in telencephalon and other developing head structures. Dev. Biol. 222, 296–306 10.1006/dbio.2000.9732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmchen F., Waters J. (2002). Ca2+ imaging in the mammalian brain in vivo. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 447, 119–129 10.1016/S0014-2999(02)01836-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holekamp T. F., Turaga D., Holy T. E. (2008). Fast three-dimensional fluorescence imaging of activity in neural populations by objective-coupled planar illumination microscopy. Neuron 13, 661–672 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman V., Laurent G. (2007). Evaluating a genetically encoded optical sensor of neural activity using electrophysiology in intact adult fruit flies. Front. Neural Circuits 1, 1–9 10.3389/neuro.04.003.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferis G. S., Marin E., Stocker R. F., Luo L. (2001). Target neuron prespecification in the olfactory map of Drosophila. Nature 414, 204–208 10.1038/35102574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferis G. S., Potter C. J., Chan A. M., Marin E. C., Rohlfing T., Maurer C. R., Jr., Luo L. (2007). Comprehensive maps of Drosophila higher olfactory centers: spatially segregated fruit and pheromone representation. Cell 128–1187–1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalchuk Y., Eilers J., Lisman J., Konnerth A. (2000). NMDA receptor-mediated subthreshold Ca(2+) signals in spines of hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 20, 1791–1799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent G., Davidowitz H. (1994). Encoding of olfactory information with oscillating neural assemblies. Science 265, 1872–1875 10.1126/science.265.5180.1872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent G., Wehr M., Davidowitz H. (1996). Temporal representations of odors in an olfactory network. J. Neurosci. 16, 3837–3847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B. J., Chen T. W., Schild D. (2007). Cell type-specific relationships between spiking and [Ca2+]i in neurons of the Xenopus tadpole olfactory bulb. J. Physiol. 582, 163–175 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.125963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn M. E., Barretto R. P., Delp S. L., Schnitzer M. J. (2008). Minimally invasive high-speed imaging of sarcomere contractile dynamics in mice and humans. Nature 454, 784–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mank M., Griesbeck O. (2008). Genetically encoded calcium indicators. Chem. Rev. 108, 1550–1564 10.1021/cr078213v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mank M., Reiff D. F., Heim N., Friedrich M. W., Borst A., Griesbeck O. (2006). A FRET-based calcium biosensor with fast signal kinetics and high fluorescence change. Biophys. J. 90, 1790–1796 10.1529/biophysj.105.073536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao T., O'Connor D. H., Scheuss V., Nakai J., Svoboda K. (2008). Characterization and subcellular targeting of GCaMP-type genetically-encoded calcium indicators. PLoS ONE 3, e1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazor O., Laurent G. (2005). Transient dynamics versus fixed points in odor representations by locust antennal lobe projection neurons. Neuron 48, 661–673 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki A., Griesbeck O., Heim R., Tsien R. Y. (1999). Dynamic and quantitative Ca2+ measurements using improved cameleons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 2135–2140 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki A., Llopis J., Heim R., McCaffery J. M., Adams J. A., Ikura M., Tsien R.Y. (1997). Fluorescent indicators for Ca2+ based on green fluorescent proteins and calmodulin. Nature 388, 882–887 10.1038/42264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mombaerts P., Wang F., Dulac C., Chao S. K., Nemes A., Mendelsohn M., Edmondson J., Axel R. (1996). Visualizing an olfactory sensory map. Cell 87, 675–686 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81387-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreaux L., Laurent G. (2007). Estimating firing rates from calcium signals in locust projection neurons in vivo. Front. Neural Circuits 1, 1–13 10.3389/neuro.04.002.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obaid A. L., Koyano T., Lindstrom J., Sakai T., Salzberg B. M. (1999). Spatiotemporal patterns of activity in an intact mammalian network with single-cell resolution: optical studies of nicotinic activity in an enteric plexus. J. Neurosci. 19, 3073–3093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuriya M., Jiang J., Nemet B., Eisenthal K. B., Yuste R. (2006). Imaging membrane potential in dendritic spines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 786–790 10.1073/pnas.0510092103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohki K., Chung S., Ch'ng Y. H., Kara P., Reid R. C. (2005). Functional imaging with cellular resolution reveals precise micro-architecture in visual cortex. Nature 433, 597–603 10.1038/nature03274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Orive J., Mazor O., Turner G. C., Cassenaer S., Wilson R. I., Laurent G. (2002). Oscillations and sparsening of odor representations in the mushroom body. Science 297, 359–365 10.1126/science.1070502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E. (2003). Molecular physiology of low-voltage-activated t-type calcium channels. Physiol. Rev. 83, 117–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy D. G., Kelleher K., Fink R., Saggau P. (2008). Three-dimensional random access multiphoton microscopy for functional imaging of neuronal activity. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 713–720 10.1038/nn.2116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiff D. F., Ihring A., Guerrero G., Isacoff E. Y., Joesch M., Nakai J., Borst A. (2005). In vivo performance of genetically encoded indicators of neural activity in flies. J. Neurosci. 25, 4766–4778 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4900-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachse S., Galizia C. G. (2002). Role of inhibition for temporal and spatial odor representation in olfactory output neurons: a calcium imaging study. J. Neurophysiol. 87, 1106–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjulson L., Miesenbock G. (2006). Optical recording of action potentials and other discrete physiological events: a perspective from signal detection theory. Physiology (Bethesda) 22, 47–55 10.1152/physiol.00036.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetters D. K., Majewska A., Yuste R. (1999). Detecting action potentials in neuronal populations with calcium imaging. Methods 18, 215–221 10.1006/meth.1999.0774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel E., Tank D. W. (1994). In vivo Ca2+ dynamics in a cricket auditory neuron: an example of chemical computation. Science 263, 823–826 10.1126/science.263.5148.823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soler-Llavina G. J., Sabatini B. L. (2006). Synapse-specific plasticity and compartmentalized signaling in cerebellar stellate cells. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 798–806 10.1038/nn1698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spors H., Wachowiak M., Cohen L. B., Friedrich R. W. (2006). Temporal dynamics and latency patterns of receptor neuron input to the olfactory bulb. J. Neurosci. 26, 1247–1259 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3100-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabor R., Yaksi E., Friedrich R. W. (2008). Multiple functions of GABA and GABA receptors during pattern processing in the zebrafish olfactory bulb. Eur. J. Neurosci. 28, 117–127 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06316.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien R. Y. (1999). Monitoring cell calcium. In Calcium as a Cellular Regulator, Carafoli E., Klee C., eds (New York, NY, Oxford University Press; ), pp. 28–54 [Google Scholar]

- Vosshall L. B., Wong A. M., Axel R. (2000). An olfactory sensory map in the fly brain. Cell 102, 147–159 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00021-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachowiak M., Cohen L. B. (2001). Representation of odorants by receptor neuron input to the mouse olfactory bulb. Neuron 32, 723–735 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00506-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace D. J., zum Alten Borgloh S. M., Astori S., Yang Y., Bausen M., Kügler S., Palmer A. E., Tsien R. Y., Sprengel R., Kerr J. N. D., Denk W., Mazahir T. H. (2008). Single-spike detection in vitro and in vivo with a genetic Ca2+ sensor. Nat. Methods 5, 797–804 10.1038/nmeth.1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. W., Wong A. M., Flores J., Vosshall L. B., Axel R. (2003). Two-photon calcium imaging reveals an odor-evoked map of activity in the fly brain. Cell 112, 271–282 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00004-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Guo H. F., Pologruto T. A., Hannan F., Hakker I., Svoboda K., Zhong Y. (2004). Stereotyped odor-evoked activity in the mushroom body of Drosophila revealed by green fluorescent protein-based Ca2+ imaging. J. Neurosci. 24, 6507–6514 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3727-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaksi E., Friedrich R. W. (2006). Reconstruction of firing rate changes across neuronal populations by temporally deconvolved Ca2+ imaging. Nat. Methods 3, 377–383 10.1038/nmeth874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuste R., Katz L. C. (1991). Control of postsynaptic calcium influx in developing neocortex by excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters. Neuron 6, 333–344 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90243-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W. L., Yan P., Wuskell J. P., Loew L. M., Antic S. D. (2007). Intracellular long-wavelength voltage-sensitive dyes for studying the dynamics of action potentials in axons and thin dendrites. J. Neurosci. Methods. 164, 225–239 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong H., Espinosa J. S., Su H. H., Muzumdar M. D., Luo L. (2005). Mosaic analysis with double markers in mice. Cell 121, 479–492 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]