Abstract

Cycloclasticus sp. strain A5 is able to grow with petroleum polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), including unsubstituted and substituted naphthalenes, dibenzothiophenes, phenanthrenes, and fluorenes. A set of genes responsible for the degradation of petroleum PAHs was isolated by using the ability of the organism to oxidize indole to indigo. This 10.5-kb DNA fragment was sequenced and found to contain 10 open reading frames (ORFs). Seven ORFs showed homology to previously characterized genes for PAH degradation and were designated phn genes, although the sequence and order of these phn genes were significantly different from the sequence and order of the known PAH-degrading genes. The phnA1, phnA2, phnA3, and phnA4 genes, which encode the α and β subunits of an iron-sulfur protein, a ferredoxin, and a ferredoxin reductase, respectively, were identified as the genes coding for PAH dioxygenase. The phnA4A3 gene cluster was located 3.7 kb downstream of the phnA2 gene. PhnA1 and PhnA2 exhibited moderate (less than 62%) sequence identity to the α and β subunits of other aromatic ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases, but motifs such as the Fe(II)-binding site and the [2Fe-2S] cluster ligands were conserved. Escherichia coli cells possessing the phnA1A2A3A4 genes were able to convert phenanthrene, naphthalene, and methylnaphthalene in addition to the tricyclic heterocycles dibenzofuran and dibenzothiophene to their hydroxylated forms. Significantly, the E. coli cells also transformed biphenyl and diphenylmethane, which are ordinarily the substrates of biphenyl dioxygenases.

Polycyclic (fused) aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are a group of hydrocarbons composed of two or more fused benzene rings that occur mostly as a result of fossil fuel combustion and as other by-products of industrial processing. PAHs are released into the marine environment by processes such as accidental discharges during the transport, use, and disposal of petroleum products, marine seepage, and forest and grass fires. PAHs are concentrated in urban marine sediments by industrial processes. Some PAHs are cytotoxic, genotoxic, and carcinogenic to marine organisms and may be transferred to humans through seafood consumption (33, 36, 54).

One group of bacteria capable of degrading aromatic compounds in marine environments belongs to the genus Cycloclasticus. These bacteria utilize a limited number of organic compounds as sole carbon sources, including aromatic hydrocarbons such as toluene, xylene, biphenyl, naphthalene, and phenanthrene (8, 14). It has recently been reported that Cycloclasticus bacteria play an important role in the degradation of petroleum PAHs in a marine environment (24). Also, four Cycloclasticus strains have been isolated from seawater by using phenanthrene as the sole carbon and energy source, and the role of these organisms in the biodegradation of petroleum PAHs in a marine environment has been investigated (24). These strains could grow on petroleum and degraded unsubstituted and substituted PAHs, such as phenanthrene, naphthalene, methylnaphthalene, fluorene, and dibenzothiophene (24).

The results of a previous study suggested that obligate marine bacteria may be more significant PAH degraders in a coastal marine environment than bacteria from terrestrial habitats, such as Pseudomonas sp. (51, 52). However, the PAH degradation mechanisms of obligate marine bacteria have been only partially studied (18, 19, 20, 21, 46, 59). In contrast, the enzymes involved in PAH degradation and genetic regulation have been extensively characterized in terrestrial isolates, including isolates of Pseudomonas and Sphingomonas species (6, 7, 11, 13, 25, 26, 30, 35, 55, 57).

In the present study, we isolated a set of genes that are for degradation of naphthalene, methylnaphthalene, phenanthrene, and dibenzothiophene from the marine bacterium Cycloclasticus sp. strain A5 and analyzed the structure and function of the genes and the enzymes which they encode.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Cycloclasticus sp. strain A5 was grown in an ONR7a medium (8) with naphthalene or phenanthrene at 25°C. Escherichia coli XL1-Blue was used for routine genetic manipulation. E. coli cells containing recombinant plasmids were maintained on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates (49) supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. The concentration of the antibiotics used was 50 μg/ml for both ampicillin and kanamycin.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or phenotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Cycloclasticus sp. strain A5 | Degrades PAHs. such as naphthalene. phenanthrene. biphenyl. etc. | 24 |

| E. coli JM109 | recA1 relA1 thi-1 Δ(lac-proAB) gyrA96 hsdR17 endA1 supE44 (rk− mk−) [F7 traD36 proAB lacIrZΔM15] | 60 |

| E. coli XL1-Blue | hsdR17 supE44 recA1 endA1 gyrA46 thi-1 relA1 lac/F′ [proAB+ lacIqlacZΔM15::Tn10 (Tetr)] | Stratagene |

| E. coli XL1-Blue MRA | Δ(mcrA) 183 Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA1 supE44 thi-1 recA96 gyrA1 relA1 lac | Stratagene |

| Plasmids | ||

| Lorist6 | Kmr: 5.28-kb cosmid vector | 15 |

| pBluescript II SK+ | lacZ Apr: 2.96-kb cloning vector | Stratagene |

| pH1a | Kmr Lorist6::11-kb Sau3A1 fragment from A5 containing phnA1A2A3A4 | This study |

| pH1b | Kmr Lorist6::11-kb Sau3A1 fragment from A5 containing phnA1A2A3A4 | This study |

| pPhnA | Apr: pBluescript:: ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase gene phnA1A2A3A4 from A5 | This study |

| pPhnC | Apr: pBluescript:: extradiol dioxygenase gene phnC from A5 | This study |

Molecular techniques.

Standard procedures were used for plasmid DNA preparation and manipulation and for agarose gel electrophoresis (49). Total genomic DNA of Cycloclasticus sp. strain A5 was isolated by the method of Marmur (34). Plasmid DNA for sequencing was isolated with a QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen), and the cloned sequences were determined by using a Taq DyeDeoxy terminator cycle sequencing kit and a model 377 sequencer (Applied Biosystems). A nucleotide sequence analysis, translation, and alignment with related genes and proteins were carried out by using the SeqED (Applied Biosystems) and GENETYX computer programs. A search of the GenBank nucleotide library for sequences similar to the sequences determined was performed by using BLAST (1) through the National Center for Biotechnology Information web site (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). A phylogenetic analysis was performed by using Clustal W, version 1.7 (58), and phylogenetic trees were constructed from evolutionary distance data (28) by the neighbor-joining method (47) by comparing closely related protein sequences. Recombinant plasmids in E. coli XL1-Blue were induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 4 h for protein analysis. Crude cell extracts were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) by using the method of Laemmli (31).

Construction of the genomic library for Cycloclasticus sp. strain A5.

Total genomic DNA of Cycloclasticus sp. strain A5 was partially digested with restriction endonuclease Sau3AI. After separation in a 0.6% agarose gel, the fraction containing fragments in the size range from 10 to 20 kb was recovered. A calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase-treated and NotI-digested Lorist6 vector (15) was ligated with the digested Cycloclasticus DNA fragments. The ligated DNA was packaged in bacteriophage λ by using a Gigapack III Gold packaging extract in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). The phages were transferred into E. coli strain XL1-Blue MRA and plated for colony formation. The library was replica plated onto LB agar plates with kanamycin, and the plates were screened for clones that turned purple or blue-gray as a result of the formation of indigo from indole due to the dioxygenase activity expressed by the clones (10).

Construction of plasmids for overexpression of the enzymes.

To express dioxygenase genes under control of the lac promoter in E. coli, pPhnA and pPhnC were constructed as follows. A 2,723-bp PstI-SalI fragment containing the phnA1 and phnA2 genes from cosmid clone pH1a was subcloned into pBluescript II SK+ (Stratagene) digested with PstI-SalI, and the plasmid was designated pISP. The fragment containing ferredoxin and ferredoxin reductase genes was amplified by PCR by using PCR primers pF-Kp (5′-GGGGTACCAATCTTAGCTAATCTTATTC) and pFr-Xh (5′-TCCCTCGAGTAGGTTAACAATGTTTGAAT) (the introduced KpnI and XhoI restriction sites are underlined). The 1,497-bp PCR product was separated by electrophoresis on a 0.8% (wt/vol) low-melting-point agarose gel and purified with a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen). The amplified DNA was subsequently digested with KpnI and XhoI and ligated into KpnI-XhoI-digested pISP. In the resulting construct (pPhnA), the phnA1A2A3A4 genes were oriented so that they could be expressed under the control of the lac promoter.

A 2,305-bp HindIII-EcoRV fragment containing the phnC gene from cosmid clone pH1a was subcloned into pBluescript II SK+ digested with HindIII-EcoRV, and the resulting plasmid was designated pPhnC.

Whole-cell biotransformations.

E. coli JM109 harboring pPhnA or E. coli JM109 harboring pBluescript II SK+ was grown in LB medium containing 150 μg of ampicillin per ml at 28°C with reciprocal shaking at 175 rpm for 8 h. Four milliliters of this culture was inoculated into 70 ml of M9 medium (49) containing 150 μg of ampicillin per ml, 10 mg of thiamine per ml, and 0.4% (wt/vol) glucose in an Erlenmeyer flask and grown at 28°C with reciprocal shaking at 175 rpm for 16 to 17 h, until the absorbance at 600 nm reached approximately 1. The cells were collected by centrifugation, washed once with the M9 medium, resuspended in 70 ml of fresh M9 medium containing 150 μg of ampicillin per ml, 10 mg of thiamine per ml, 0.4% (wt/vol) glucose, 1 mM (final concentration) IPTG, and each aromatic compound listed in Table 2 at a final concentration of 1 mM, and cultivated in an Erlenmeyer flask at 28°C with reciprocal shaking at 175 rpm for 2 to 3 days. Three independent biotransformation experiments were conducted.

TABLE 2.

Substrate specificity of PhnA dioxygenase

| Substrate | Producta | Conversion rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Phenanthrene | 3,4-Dihydrophenanthrene-3,4-diol (1) | 33 |

| Anthracene | NDb | |

| Naphthalene | 1,2-Dihydronaphthalene-1,2-diol (2) | 71 |

| 1-Methylnaphthalene | 8-Methyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene-1,2-diol (3) | 93 |

| 2-Methylnaphthalene | 7-Methyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene-1,2-diol (4) | 56 |

| Dibenzofuran | 2-Hydroxydibenzofuran (5) | 57 |

| Dibenzothiophene | 2-Hydroxydibenzothiophene (6) | 21 |

| Pyrene | ND | |

| Benzo[a]pyrene | ND | |

| Toluene | ND | |

| Biphenyl | o-Biphenylol (2-phenylphenol) (7) | 12 |

| m-biphenylol (3-phenylphenol) (8) | 4 | |

| Diphenylmethane | 2-Benzylphenol (9) | 14 |

| 2-Phenylbenzoxazole | ND |

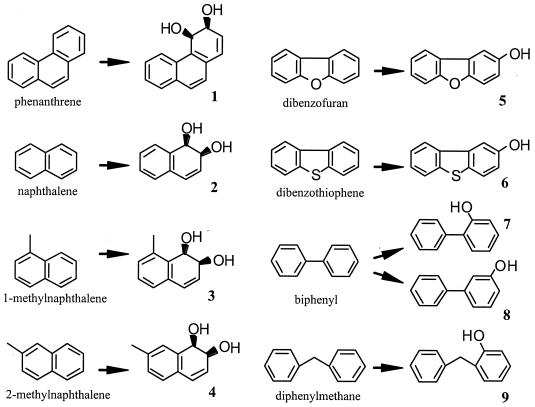

The numbers in parentheses corresponds to the numbers in Fig. 4.

ND, no product detected.

Extraction and HPLC analysis of the converted products.

To extract the converted products and the substrates, the same volume of methanol (MeOH) as the volume of the culture medium was added to the culture of the transformed E. coli cells and mixed for 30 min. After centrifugation to remove the cells, the culture supernatant was subjected to high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) or to further purification of the converted products.

The liquid phase (80 μl) was passed through an XTerra C18 HPLC column (4.6 by 250 mm; Waters) equipped with a photodiode array detector (model 2996; Waters). The column was developed at a flow rate of 1 ml/min with solvent A (H2O-MeOH, 1:1) for 5 min and then with a no. 3 gradient (Waters) from solvent A to solvent B (MeOH-2-propanol, 6:4) for 15 min, and the maximum absorbance in the 230- to 350-nm range was monitored.

Purification and identification of the converted products.

The culture supernatant (700 to 1,400 ml) obtained by the procedure described above was concentrated in vacuo and then extracted twice with 500 ml of ethyl acetate (EtOAc). The resulting organic layer was concentrated in vacuo and analyzed by thin-layer chromatography on silica gel (0.25-mm Silica Gel 60; Merck) developed with the following solvent systems: phenanthrene, hexane-EtOAc (1:1), naphthalene, hexane-EtOAc (1:1), 1-methylnaphthalene, hexane-EtOAc (4:1), 2-methylnaphthalene, hexane-EtOAc (4:1), dibenzofuran, hexane-EtOAc (5:1), dibenzothiophene, hexane-EtOAc (3:1), biphenyl, hexane-EtOAc (10:1), diphenylmethane, and hexane-EtOAc (2:1). The transformed products, as well as the substrates which were in the organic phase, were applied to a silica gel chromatography column (20 by 250 mm; Silica Gel 60; Merck) that was developed with the following solvent systems: phenanthrene, hexane-EtOAc (1:1), naphthalene, hexane-EtOAc (1:1), 1-methylnaphthalene, hexane-EtOAc (4:1), 2-methylnaphthalene, hexane-EtOAc (4:1, stepwise), dibenzofuran, hexane-EtOAc (5:1), dibenzothiophene, hexane-EtOAc (3:1), biphenyl, hexane-EtOAc (15:1), diphenylmethane, and hexane-EtOAc (4:1).

The structure of each transformed product was analyzed by mass spectrometry with a JEOL JMS-AX505W and by nuclear magnetic resonance with a BRUKER AMX400. Tetramethylsilane was used as the internal standard.

Assay of recombinant PAH extradiol dioxygenase.

The extradiol dioxygenase gene (phnC) was cloned into the pBluescript SK+ vector (Stratagene) and expressed in E. coli XL1-Blue. After growth of 20-ml cultures to an absorbance at 600 nm of 0.2, IPTG was added to a concentration of 1 mM, and incubation was continued for 3 h to induce phnC. E. coli cells were harvested, washed with 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 10% (vol/vol) acetone, and resuspended in 10 ml of the same buffer. The cells were disrupted by sonication, the cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min, and the resulting supernatant was used as the crude cell extract. The protein concentration of each crude extract was estimated with a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The activity against 1,2-dihydroxynaphthalene (1,2-DHN) was determined spectrophotometrically by the method of Kuhm et al. (29); the reaction mixture contained a 50 mM acetic acid-NaOH buffer (pH 5.5) and 1 to 50 μg of protein. The reaction was started by adding 0.4 μmol of 1,2-DHN in 10 μl of tetrahydrofuran, and the initial rate of decrease in the absorbance at 331 nm was measured. A molar extinction coefficient of 2,600 M−1 cm−1 for 1,2-DHN at 331 nm, as calculated by Kuhm et al. (29), was used. The extradiol dioxygenase activities with other substrates were assayed by measuring formation of the corresponding ring fission products. The absorbance maxima and extinction coefficients used for the ring fission products of the substrates were as follows: 375 nm and 36,000 M−1 cm−1, respectively, for catechol (41); 388 nm and 15,000 M−1 cm−1, respectively, for 3-methylcatechol; 382 nm and 31,500 M−1 cm−1, respectively, for 4-methylcatechol (32); and 434 nm and 22,000 M−1cm−1, respectively, for 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl (56). Each reaction mixture contained 0.1 M sodium phosphate (pH 7.5), 10% (vol/vol) acetone, and 100 μM 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl, 400 μM 3-methylcatechol, 400 μM 4-methylcatechol, or 400 μM catechol.

Chemicals and reagents.

All the chemicals used in this study were the highest purity commercially available. PAHs were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, and the other chemicals were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Difco, Aldrich Chemicals, and Gibco BRL. The enzymes and reagents used for nucleic acid manipulation were purchased from Takara Shuzo.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper have been deposited in the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank libraries under accession number AB102786.

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing of the PAH catabolic genes from strain A5.

To clone the genes responsible for the early stage of PAH degradation, genomic DNA from Cycloclasticus sp. strain A5 was partially digested with restriction endonuclease Sau3AI and ligated into NotI-digested Lorist6 to generate a genomic library. Two of the resulting constructs, which were designated pH1a and pH1b, had the ability to oxidize indole to indigo, which is indicative of the presence of an aromatic oxygenase gene (10). Restriction mapping of these clones revealed that they had the same 10.5-kb Sau3AI fragment.

Analysis of the pH1a nucleotide sequence.

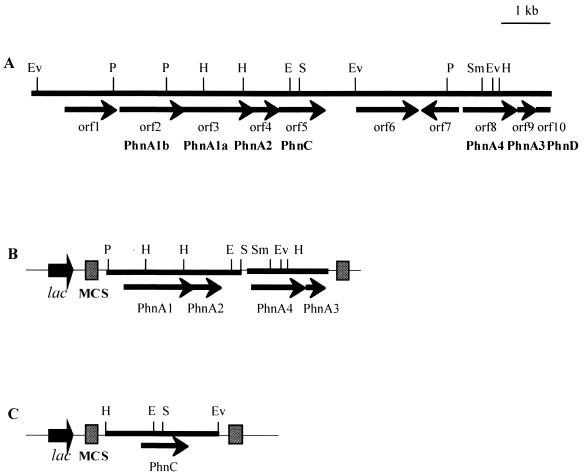

The 10.5-kb nucleotide sequence of pH1a was determined, and sequence analysis revealed the presence of nine complete open reading frames (ORFs) and one partial ORF (Fig. 1). Each ORF was initiated by the canonical ATG start codon and was preceded by a ribosomal binding site.

FIG. 1.

Physical map and genetic organization of the PAH degradation genes (A) and structure of the plasmids constructed, pPhnA (B) and pPhnC (C). ORFs are indicated by arrows, and the direction of reading is indicated by the arrowheads. The gene designation of each ORF is indicated, as are the sites of the common restriction enzymes. Subclones pPhnA and pPhnC contain the phnA1A2A3A4 genes and the phnC gene, respectively, under the control of the lac promoter of pBluescript II SK+. Restriction sites: E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; P, PstI; S, SalI; V, EcoRV.

The functions of individual ORFs were deduced from sequence homology to previously described genes and the corresponding amino acid sequences (Table 3). The predicted polypeptide sequences of seven ORFs exhibited high degrees of similarity with the polypeptide sequences used for catabolism of PAHs. The seven ORFs, ORFs 2 to 5 and 8 to 10, were designated the phnA1b, phnA1, phnA2, phnC, phnA4, phnA3, and phnD genes, respectively (genes for the degradation of PAHs isolated from the phenanthrene degrader). The order of these phn genes, which were not continuously clustered, is different from that previously reported for aromatic ring dioxygenase genes (55, 61).

TABLE 3.

Properties of the phn genes identified on the 10.5-kb fragment of A5

| Gene | Function | Deduced molecular mass (kDa) | Protein with similar sequence | % Identity (no. of residues) | Organism | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| orf1 | PdxA homolog | 34 | Orf1158 | 56 (319) | Sphingomonas aromaticivorans F199 | NP_049207 |

| PdxA | 35 (328) | Bacillus halodurans C-125 | NP_241670 | |||

| PdxA | 34 (322) | Fusobacterium nucleatum ATCC 25586 | NP_603133 | |||

| phnA1b | ISP α subunit | 48 | AhdA1d | 60 (424) | Sphingomonas sp. strain P2 | BAC65433 |

| BphA1d | 60 (426) | Sphingomonas aromaticivorans F199 | NP_049206 | |||

| AhdA1c | 48 (420) | Sphingomonas sp. strain P2 | BAC65426 | |||

| PhnA1 | 22 (460) | Cycloclasticus sp. strain A5 | AB102786 | |||

| phnA1 | ISP α subunit | 52 | BphA1f | 64 (452) | Sphingomonas aromaticivorans F199 | NP_049062 |

| DbtAc | 51 (443) | Burkholderia sp. strain DBT1 | AAK62353 | |||

| PhnAc | 52 (416) | Alcaligenes faecalis AFK2 | BAA76323 | |||

| phnA2 | ISP β subunit | 21 | BphA2f | 52 (173) | Sphingomonas aromaticivorans F199 | NP_049061 |

| ThnA2 | 39 (177) | Sphingopyxis macrogoltabida TFA | AAN26444 | |||

| BphA2 | 33 (171) | Comamononas testosteroni TK 102 | BAC01053 | |||

| phnC | Extradiol dioxygenase | 34 | BphC | 66 (289) | Sphingomonas paucimobilis Q1 | P11122 |

| DmdC | 64 (289) | Sphingomonas paucimobilis TZS-7 | BAB07894 | |||

| BphC | 64 (289) | Sphingomonas aromaticivorans F199 | NP_049210 | |||

| trpB | Tryptophan synthase β subunit | 42 | TrpB | 57 (388) | Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis MB4T | NP_623178 |

| TrpB-2 | 56 (380) | Pyrococcus furtosus DSM 3638 | NP_579435 | |||

| TrpB | 56 (391) | Brucella suis 1330 | NP_699085 | |||

| orf7 | Unknown | 26 | No obvious homolog | |||

| phnA4 | Reductase | 38 | TouF | 50 (313) | Pseudomonas stutzeri OX1 | CAA06659 |

| PhnAa | 47 (338) | Alcaligenes faecalis AFK2 | BAA76321 | |||

| ThnA4 | 47 (342) | Sphingopyxis macrogoliabida TFA | AAN26446 | |||

| phnA3 | Ferredoxin | 11 | BphA3 | 63 (104) | Sphingomonas aromaticivorans F199 | NP_049211 |

| PhnR | 63 (104) | Sphingomonas chungbukensis | AAC95320 | |||

| NsaA3 | 59 (103) | Sphingomonas sp. strain BN6 | AAB06726 | |||

| phnD | Isomerase | Orf8 | 64 (115) | Burkholderia sp. strain DBT1 | AF96187 | |

| NsaD | 61 (115) | Sphingomonas sp. strain BN6 | AAD45416 | |||

| NahD | 58 (115) | Sphingomonas aromaticivorans F199 | NP_049214 |

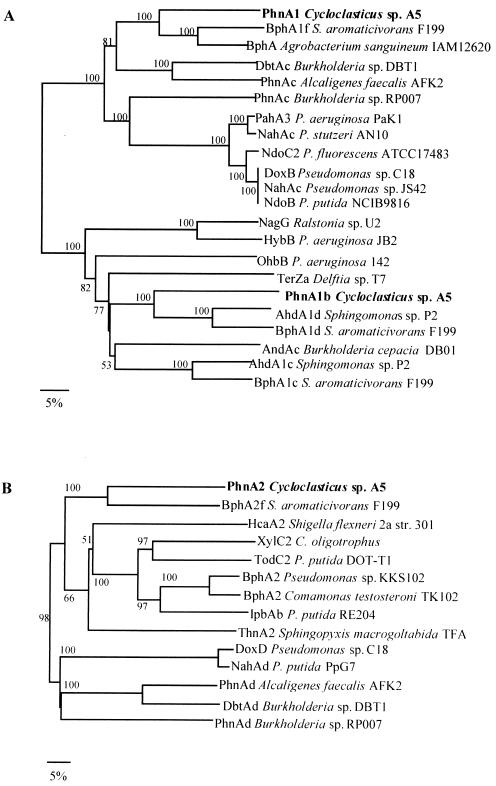

The predicted amino acid sequence of PhnA1b exhibited 60 to 48% sequence identity with the amino acid sequences of the iron-sulfur protein (ISP) α subunits of aromatic oxygenases from Sphingomonas sp. strain P2 (AhdA1d) (43), Sphingomonas aromaticivorans strain F199 (BphA1d) (45), and Sphingomonas sp. strain P2 (AhdA1c) (43). The phylogenetic analysis revealed that PhnA1b clustered with the large oxygenase subunits that catalyzed the hydroxylation of salicylate and substituted salicylate (Fig. 2A). Both the Reiske-type [2Fe-2S] cluster binding site motif (Cys-X1-His-X17-Cys-X2-His) and the His-213, His-218, and Asp-361 residues that may coordinate the mononuclear nonheme iron active site (42) were conserved in the deduced amino acid sequence encoded by phnA1b. The gene homologs for large and small oxygenase subunits are usually located in pairs; however, no small-subunit gene was found in the flanking region of phnA1b.

FIG. 2.

Dendrograms based on the large subunits (A) and small subunits (B) of the aromatic ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases. The dendrograms were constructed by using the previously published amino acid sequences processed by Clustal W. Scale bar = 5% divergence. The numbers at nodes are bootstrap values expressed as percentages. The following sequences were used: P. putida NCIB 9816 nah genes (GenBank accession no. M83950), Pseudomonas sp. strain C18 dox genes (M6045), S. aromaticivorans strain F199 bph genes (AF079317), Burkholderia sp. strain DBT1 dbt genes (AF380367), Burkholderia sp. strain RP007 phn genes (AF061751), A. faecalis AFK2 phn genes (AB024945), Sphingomonas sp. strain P2 ahd genes (AB091692), P. putida PpG7 nahAd gene (M83949), Pseudomonas sp. strain JS42 nahAc gene (U49496), P. stutzeri AN10 nahAc gene (AF039533), P. putida NCIB9816 ndoB gene (M23914), P. fluorescens ATCC 17483 ndoC2 gene (AF004283), P. aeruginosa Pak1 pahA3 gene (D84146), Agrobacterium sanguineum IAM12620 bphA gene (AB062104), P. aeruginosa 142 ohbB gene (AF121970), P. aeruginosa JB2 hybB gene (AF087482), Delfita sp. strain T7 terZa gene (AB081091), Burkholderia cepacia DB01 andAc gene (AY223539), Ralstonia sp. strain U2 nagG gene (AF036940), Cycloclasticus oligotrophus xylC2 gene (U51165), Shigella flexneri 2a str. 301 hcaA2 gene (AAN44085), Comamonas testosteroni TK102 bphA2 gene (AB086835), S. macrogoltabida TFA thnA2 gene (AAN26444), P. putida RE204 ipbAb gene (AF006691), Pseudomonas sp. strain KKS102 bphA2 gene (Q52439), and P. putida DOT-T1 todC2 gene (Y1825).

The amino acid sequence of PhnA1 exhibited 51 to 62% identity with the amino acid sequences of the α subunits of PAH dioxygenases from S. aromaticivorans strain F199 (BphA1f) (45), Burkholderia sp. strain DBT1 (DbtAc) (accession no. AF380367), and Alcaligenes faecalis strain AFK2 (PhnAc) (accession no. BAA76323), whereas the other known α subunits exhibited levels of sequence identity lower than 45%. The phylogenetic analysis of the ISP α subunits of the oxygenase components of aromatic ring dioxygenases revealed that PhnA1 was divergent from nah-nod-dox-pah group (Fig. 2A). The ISP α subunit has both the Cys-X1-His-X17-Cys-X2-His Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] cluster binding motif (35) and the potential mononuclear nonheme iron coordinate site consensus sequence consisting of His-207, His-211, and Asp-360 (42).

The phnA2 gene was found downstream of the phnA1 gene. PhnA2 exhibited moderate amino acid sequence homology to the ISP β subunits of aromatic ring dioxygenases. The β subunit of PAH dioxygenase from S. aromaticivorans (bphA2f) (45) exhibited relatively high sequence identity to PhnA2 (52%). The other known β subunits exhibited levels of sequence identity less than 39%. Figure 2B shows a dendrogram of the ISP β subunits of aromatic ring dioxygenases.

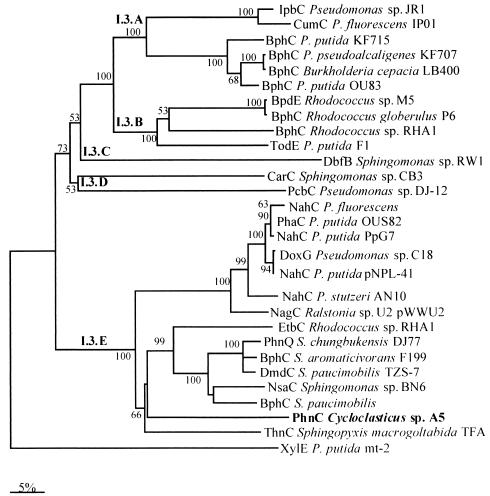

The phnC gene was located downstream of the phnA2 gene, and the amino acid sequence of PhnC exhibited 60 to 66% identity with the amino acid sequences of the 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenases from Sphingomonas paucimobilis (BphC) (56), S. aromaticivorans (BphC) (45), and Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1 (EtbC) (17). Figure 3 shows a dendrogram resulting from a comparison of two-domain extradiol dioxygenases of the I.3 family which preferentially cleave bicyclic substrates (12). The members of the PhnC cluster in group 2 of the I.3.E subfamily, which have more diverse sequences, and enzymes belonging to this group have exhibited high activity with different substrates (2).

FIG. 3.

Dendrogram based on the extradiol dioxygenases. The dendrogram was constructed by using the previously published amino acid sequences processed by Clustal W. Scale bar = 5% divergence. The numbers at nodes are bootstrap values expressed as percentages. The following sequences were used: Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1 ipbC gene (GenBank accession no. U53507), Pseudomonas fluorescens IP01 cumC gene (D37828), P. putida KF715 bphC gene (M33813), Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707 bphC gene (M83673), Burkholderia cepacia LB400 bphC gene (X66122), P. putida OU83 bphC gene (X91876), Rhodococcus sp. strain M5 bpdE gene (U27591), Rhodococcus globerulus P6 bphC gene (X75663), Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1 bphC gene (D32142), P. putida F1 todE gene (JO4996), Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1 dbfB gene (X72850), Sphingomonas sp. strain CB3 carC gene (AF060489), Pseudomonas sp. strain DJ-12 pcbC gene (D44550), P. fluorescens nahC gene (AY048760), P. putida OUS82 pahC gene (D16629), P. putida PpG7 nahC gene (J04994), Pseudomonas sp. strain C18 doxG gene (M60405), P. putida pNPL41 nahC gene (Y14173), P. stutzeri AN10 nahC gene (AF039533), Ralstonia sp. strain U2 nagC gene (AF036940), Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1 etbC gene (D78322), Sphingomonas chungbukensis DJ77 phnQ gene (AF061802), S. aromaticivorans F199 bphC gene (AF079317), S. paucimobilis TZS-7 dmdC gene (AB035677), Sphingomonas sp. strain BN6 nsaC gene (U65001), S. paucimobilis bphC gene (P11122), S. macrogoltabida TFA thnC gene (AF157565), and P. putida mt-2 xylE gene (V01161).

The phnA4 gene was located 2.8 kb downstream of the phnC gene. The amino acid sequence of PhnA4 exhibited 47 to 51% identity with the amino acid sequences of the NADH-ferredoxin oxidoreductase components of mono- and dioxygenase systems from Pseudomonas stutzeri (TouF) (accession no. AJ438269), A. faecalis (PhnAa) (accession no. AB024945), and Sphingopyxis macrogoltabida (ThnA4) (accession no. AF157565). PhnA4 possesses an N-terminal region similar to that of the chloroplast-type ferredoxins, in which four Cys residues (Cys-39, -44, -47, and -78) involved in the coordination of two iron atoms of the [2Fe-2S] cluster are conserved. The flavin adenine dinucleotide-binding domain (amino acids 106 to 196) and NAD-binding domain (amino acids 206 to 318) were found in the C-terminal region of PhnA4.

The phnA3 gene was located downstream of the phnA4 gene, and the gene product exhibited 63% sequence identity with the Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin components of known dioxygenases.

The partial phnD gene was located downstream of the phnA4 gene, and the predicted amino acid sequence of the phnD product exhibited 58 to 60% identity with the amino acid sequences of 2-hydroxychromene-2-carboxylate isomerase from Burkholderia sp. strain DBT1 (orf8) (accession no. AAK96187), Sphingomonas sp. strain BN6 (nsaD) (accession no. AAD45416), and S. aromaticivorans strain F199 (nahD) (45).

Expression of the phnA1A2A3A4 genes in E. coli.

To determine whether the phnA1A2A3A4 genes actually encode the holoenzyme of an aromatic ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase, the genes were introduced into E. coli and expressed. The 2.7-kb PstI-SalI DNA fragment of pH1a, which contained the phnA1 and phnA2 genes, was cloned into the same site of pBluescript II SK+ to obtain pISP. The DNA fragment containing the phnA3 and phnA4 genes into which the XhoI and KpnI sites had been introduced by PCR amplification was cloned into the XhoI-KpnI site of pISP to obtain pPhnA (Fig. 1B).

E. coli carrying pPhnA and pBluescript II SK+ (negative control) was inoculated into LB medium containing ampicillin and induced by 1 mM IPTG. The recombinant proteins encoded by the phnA1, phnA2, phnA3, and phnA4 genes were overexpressed and separated by SDS-PAGE (data not shown). The sizes estimated by SDS-PAGE (52.5, 23.3, 38, and 12.5 kDa) agreed well with the predicted sizes of PhnA1 (52 kDa), PhnA2 (23 kDa), PhnA4 (38 kDa), and PhnA3 (11 kDa).

Biotransformation of various aromatic compounds with recombinant dioxygenase.

To examine the substrate range of aromatic ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase, we conducted three independent biotransformation (bioconversion) experiments with the various aromatic compound substrates listed in Table 2 using the recombinant E. coli cells expressing the phnA1A2A3A4 genes (pPhnA). After the substrates and cells had been cultured for 2 to 3 days, an HPLC analysis showed that E. coli possessing pPhnA transformed phenanthrene, naphthalene, 1-methylnaphthalene, 2-methylnaphthlene, biphenyl, and diphenylmethane, in addition to the tricyclic (fused) heterocycles dibenzofuran and dibenzothiophene, while it was not able to transform anthracene, pyrene, benzo[a]pyrene, toluene, and 2-phenylbenzoxazole (Table 2).

Structural analysis of the products converted by E. coli expressing phnA1A2A3A4.

The crude products obtained with the recombinant E. coli strain from phenanthrene, naphthalene, 1-methylnaphthalene, 2-methylnaphthlene, dibenzofuran, dibenzothiophene, biphenyl, and diphenylmethane were determined by HPLC and thin-layer chromatography, and the products detected were purified by silica gel column chromatography. Table 2 shows the hydroxylated products which were identified by comparison with the previously reported spectral data (mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance data) (5, 22, 23, 38, 39, 40, 48), whose chemical structures are shown in Fig. 4. Phenanthrene, naphthalene, 1-methylnaphthalene, and 2-methylnaphthalene were converted to their cis-dihydrodiol forms, which are the typical products of aromatic ring dioxygenases, whereas the products obtained from dibenzofuran, dibenzothiophene, biphenyl, and diphenylmethane were detected not as cis-dihydrodiols but as monohydroxylated forms. The cis-dihydrodiols of the latter compounds generated enzymatically seemed to be converted to the monohydroxylated compounds shown in Fig. 4 nonenzymatically due to the structural instability of the cis-dihydrodiols.

FIG. 4.

Structures of products converted from aromatic substrates by E. coli cells harboring pPhnA.

Expression of the phnC gene in E. coli.

An expression vector was constructed to analyze the activities of PhnC with different substrates. The 2.3-kb HindIII-EcoRV DNA fragment was cloned into the same site of pBluescript II SK+ (Fig. 1C) and expressed in E. coli JM109. Overproduction of PhnC was confirmed by SDS-PAGE (data not shown). The size estimated by SDS-PAGE (32 kDa) agrees well with the predicted size for PhnC (34 kDa). The activities of PhnC with different monocyclic and bicyclic catechol derivatives were examined spectrophotometrically by using triplicate samples. The values obtained in three independent experiments were averaged (Table 4). The highest activity of PhnC was observed with 3-methylcatechol. Interestingly, the activities of PhnC with fused, unfused, and monocyclic catechols were almost the same.

TABLE 4.

Activity of PhnC extradiol dioxygenase

| Substrate | Activity (μmol/min/mg)a | Relative activity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1,2-DHN | 186 (7) | 53 |

| 2,3-Dihydroxybiphenyl | 167 (27) | 47 |

| 3-Methylcatechol | 353 (75) | 100 |

| 4-Methylcatechol | 229 (6) | 65 |

| Catechol | 154 (40) | 44 |

Average (standard error) for three determinations.

DISCUSSION

We describe in this paper the cloning, sequencing, and functional expression in E. coli of genes coding for a novel PAH ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase from Cycloclasticus sp. strain A5. It has been reported that the gene clusters responsible for PAH degradation are localized on plasmids (nah in a Pseudomonas putida strain [30]; ndo in a P. putida strain [55]; dox in Pseudomonas sp. strain C18 [7]; nag in Pseudomonas sp. strain U2 [13]; phn in Burkholderia sp. strain RP007 [32]) and on chromosomes (pah in P. putida OUS82 [57]; nah in P. stutzeri AN10 [6]). Cycloclasticus sp. strain A5 harbored no plasmid, and the dioxygenase genes described in this paper were localized on the chromosome (Kasai and Harayama, unpublished data). The order of the phn genes was found to be quite different from that of analogous genes reported previously (55, 61).

A phylogenetic analysis of the predicted amino acid sequence of the phnA1 gene product revealed some divergence from the α-subunit sequences described previously in that it falls outside the major cluster, with which the level of amino acid sequence similarity is less than 44% (Fig. 2A), although the basic sequence features of the protein family are conserved. A phylogenetic analysis of the β subunits gave a tree similar to that constructed for the α subunits, indicating that PhnA2 formed a cluster with the β subunit BphA2f from S. aromaticivorans F199 (accession no. NP_049061), which fell outside the major cluster (Fig. 2B).

The phnA3 and phnA4 genes, which encode the ferredoxin and ferredoxin reductase components of the multicomponent PAH dioxygenase, were located 3.7-kb downstream of the β subunit (Fig. 1). Expression in E. coli JM109 of only the genes for the α and β subunits (phnA1 and phnA2) did not result in the presence of active dioxygenase (data not shown), while dioxygenation activity was found when these genes were coexpressed with a cognate electron supply system consisting of the PhnA3 ferredoxin and the PhnA4 ferredoxin reductase from Cycloclasticus sp. strain A5. The genetic organization of most of the ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases that have been investigated involves cistrons encoding the α and β subunits which are contiguous with the genes of the specific electron carrier or at least are clustered in the same transcriptional unit, as is the case for the carbazole dioxygenase of Pseudomonas sp. strain CA10 (50) and the p-cumate dioxygenase of P. putida F1 (9). Moreover, the gene encoding the reductase associated with the electron carrier is also generally, although not always, present in such dioxygenase gene clusters (3). The genes encoding the PAH dioxygenase system of A5 were located on separate transcriptional units (data not shown). This suggests that the electron transport proteins of the PAH dioxygenase system may be shared with other redox systems, possibly to maximize the catabolic potential while limiting its genetic burden. Harayama et al. have proposed that this tolerance between redox and oxygenase partners may also function as an evolutionary process for multicomponent oxygenases (16). Although some potential catabolic and evolutionary benefit may result from multipurpose electron transport proteins, the data raise the question of coordination of expression of the genes. However, the expression mechanism of the dioxygenase genes in Cycloclasticus remains unknown. It would be interesting to investigate whether these proteins are expressed constitutively or coordinately.

We demonstrated that the PhnA dioxygenase has a wide PAH substrate range, although this enzyme could not use anthracene as a substrate. The E. coli cells possessing phnA genes converted phenanthrene, naphthalene, 1-methylnaphthalene, and 2-methylnaphthalene, in addition to the tricyclic fused heterocycles dibenzofuran and dibenzothiophene, to their hydroxylated forms. Significantly, the E. coli cells expressing phnA were also able to transform biphenyl and diphenylmethane with low efficiency; these compounds are unfused linked aromatic compounds and ordinarily are substrates not of PAH dioxygenases but of biphenyl dioxygenases (37, 53). For example, phenanthrene dioxygenase that was isolated from the marine bacterium Nocardioides sp. strain KP7 transformed phenanthrene, anthracene, fluorene, naphthalene, dibenzofuran, and dibenzothiophene, which are polycyclic aromatic compounds, whereas it did not convert biphenyl and diphenylmethane to their hydroxyl products (53). Parales et al. have reported that several amino acids at the active site of the dioxygenase ISP α subunit were consistent with the enzyme's preference for an aromatic hydrocarbon substrate (42). The three-dimensional structure of the oxygenase component (α3 [NdoB], β3 [NdoC]) of the naphthalene dioxygenase of Pseudomonas sp. strain NCIB 9816-4 revealed a long narrow gorge which might provide access for substrates to catalytic iron in NdoB. The five residues constituting the narrowest part of the channel near the catalytic iron in NdoB were completely conserved in PhnA1 of Cycloclasticus sp. strain A5 as Asn-220, Phe-201, His-207, His-212, and Phe-350. However, the residues lining the substrate-binding pocket below the catalytic iron and the residues in the gorge above the catalytic iron were divergent. This sequence diversity may contribute to the wide range of PAHs that are degraded by Cycloclasticus sp. strain A5 (24).

A phylogenetic analysis of the predicted amino acid sequences of the phnA1b gene product revealed that PhnA1b clusters with α oxygenase subunits of salicylate 1-hydroxylase and salicylate 5-hydroxylase. These enzymes are monooxygenases that exhibit sequence similarity with dioxygenases such as naphthalene dioxygenase and require four gene products (i.e., the α and β subunits of a hydroxylase component, ferredoxin, and ferredoxin reductase) for full monooxygenation activity (43, 61). Because the other β-subunit gene of oxygenase was not found in the flanking region of phnA1b, it would be interesting to examine whether PhnA1b can combine with PhnA2 to form a functional ISP and utilize the same ferredoxin and ferredoxin reductase as the PhnA1PhnA2 oxygenase. Such a process was observed in S5H of Ralstonia sp. strain U2, which shared electron transport with naphthalene dioxygenase (61).

The phnC gene encodes the PAH extradiol dioxygenase. The results of the phylogenetic analysis showed that PhnC is one of the two-domain extradiol dioxygenases of the I.3 family which preferentially cleave bicyclic substrates (Fig. 3). The activities with fused, unfused, and single-ring compounds were not very different, and significant high PhnC activities were observed with substituted monocyclic catechol compounds (Table 4). Based on these results, there is a possibility that PhnC is involved in both the upper and lower pathways for degradation of naphthalene, phenanthrene, and biphenyl. Identification of the true substrates of PhnC and isolation of other ring cleavage enzymes, such as protocatechuate dioxygenases, would contribute to our understanding of the pathways for degradation of aromatic compounds in Cycloclasticus.

The presence of multiple dioxygenase genes in a single bacterium has recently been reported; for example, four to six dioxygenase α-subunit genes were found in various species of Sphingomonas that are able to efficiently degrade a wide range of aromatic hydrocarbons (4, 27, 44, 45). Geiselbrecht et al. have also reported that Cycloclasticus has at least two kinds of dioxygenase α-subunit genes (14). Since PhnA was not able to convert anthracene and monocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, such as toluene and xylene (Table 3), other dioxygenase genes in Cycloclasticus should be examined to explain the efficient degradation of a wide range of aromatic hydrocarbons by this organism.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Hiromi Awabuchi for her technical assistance.

This work was supported by the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO).

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andujar, E., M. J. Hernaez, S. R. Kaschabek, W. Reineke, and E. Santero. 2000. Identification of an extradiol dioxygenase involved in tetralin biodegradation: gene sequence analysis and purification and characterization of the gene product. J. Bacteriol. 182:789-795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armengaud, J., B. Happe, and K. N. Timmis. 1998. Genetic analysis of dioxin dioxygenase of Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1: catabolic genes dispersed on the genome. J. Bacteriol. 180:3945-3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armengaud, J., and K. N. Timmis. 1998. Genetic analysis of dioxin dioxygenase of Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1: catabolic genes dispersed on the genome. J. Bacteriol. 180:3954-3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bestetti, G., D. Bianchi, A. Bosetti, P. D. Gennaro, E. Galli, B. Leoni, F. Pelizzoni, and G. Sello. 1995. Bioconversion of substituted naphthalenes to the corresponding 1,2-dihydro-1,2-dihydroxy derivatives. Determination of the regio- and stereochemistry of the oxidation reactions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 44:306-313. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosch, R., E. Garcia-Valdes, and E. R. B. Moore. 1999. Genetic characterization and evolutionary implications of a chromosomally encoded naphthalene-degradation upper pathway from Pseudomonas stutzeri AN10. Gene 236:149-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denome, S. A., D. C. Stanley, E. S. Olson, and K. D. Young. 1993. Metabolism of dibenzothiophene and naphthalene in Pseudomonas strains: complete DNA sequence of an upper naphthalene catabolic pathway. J. Bacteriol. 175:6890-6901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyksterhouse, S. E., J. P. Gray, R. P. Herwig, J. G. Lara, and J. T. Staley. 1995. Cycloclasticus pugetii gen. nov., sp. nov., an aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading bacterium from marine sediments. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:116-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eaton, R. W. 1996. p-Cumate catabolic pathway in Pseudomonas putida F1: cloning and characterization of DNA carrying the cmt operon. J. Bacteriol. 178:1351-1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ensley, B. D., B. J. Ratzkin, T. D. Osslund, M. J. Simon, L. P. Wackett, and D. T. Gibson. 1983. Expression of naphthalene oxidation genes in Escherichia coli results in the biosynthesis of indigo. Science 222:167-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erickson, B. D., and F. J. Mondello. 1992. Nucleotide sequence and transcriptional mapping of the genes encoding biphenyl dioxygenase multicomponent polychlorinated-biphenyl-degrading enzyme of Pseudomonas sp. strain LB400. J. Bacteriol. 174:2903-2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Etlis, L. D., and J. T. Bolin. 1996. Evolutionary relationships among extradiol dioxygenases. J. Bacteriol. 178:5930-5937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuenmayor, S., L. M. Wild, A. L. Boyes, and P. A. Williams. 1998. A gene cluster encoding steps in conversion of naphthalene to gentisate in Pseudomonas sp. strain U2. J. Bacteriol. 180:2522-2530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geiselbrecht, A. D., B. P. Hedlund, M. A. Tichi, and J. T. Staley. 1998. Isolation of marine polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH)-degrading Cycloclasticus strains from the Gulf of Mexico and comparison of their PAH degradation ability with that of Puget Sound Cycloclasticus strains Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4703-4710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibson, T. J., A. Rosenthal, and R. H. Waterston. 1987. Lorist6, a cosmid vector with BamHI, NotI, ScaI and HindIII cloning sites and altered neomycin phosphotransferase gene expression. Gene 53:283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harayama, S., M. Kok, and E. Neidle. 1992. Functional and evolutionary relationships among diverse oxygenases. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 46:565-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauschild, J. E., E. Masai, K. Sugiyama, T. Hatta, K. Kimbara, M. Fukuda, and K. Yano. 1996. Identification of an alternative 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenase in Rhodococcus sp. strain RAH1 and cloning of the gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:2940-2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedlund, B. P., A. D. Geiselbrecht, T. J. Bair, and J. T. Staley. 1999. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon degradation by a new marine bacterium, Neptunomonas naphthovorans gen. nov., sp. nov. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:251-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwabuchi, T., and S. Harayama. 1997. Biochemical and genetic characterization of 2-carboxybenzaldehyde dehydrogenase, an enzyme involved in phenanthrene degradation by Nocardioides sp. strain KP7. J. Bacteriol. 179:6488-6494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwabuchi, T., and S. Harayama. 1998. Biochemical and genetic characterization of trans-2′-carboxybenzalpyruvate hydratase-aldolase from a phenanthrene-degrading Nocardioides strain. J. Bacteriol. 180:945-949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwabuchi, T., and S. Harayama. 1998. Biochemical and molecular characterization of 1-hydroxy-2-naphthoate dioxygenase from Nocardioides sp. KP7. J. Biol. Chem. 273:8332-8336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jerina, D. M., H. Selander, H. Yagi, M. C. Wells, J. F. Davey, V. Mahadevan, and D. T. Gibson. 1976. Dihydrodiols from anthracene and phenanthrene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 98:5988-5996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jia, C., D. Piano, T. Kitamura, and Y. Fujiwara. 2000. New method for preparation of coumarins and quinolinones via Pd-catalyzed intramolecular hydroarylation of C—C triple bonds. J. Org. Chem. 65:7516-7522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasai, Y., H. Kishira, and S. Harayama. 2002. Bacteria belonging to the genus Cycloclasticus play a primary role in the degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons released in a marine environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5625-5633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kauppi, B., K. Lee, E. Carredano, R. E. Parales, D. T. Gibson, H. Eklund, and S. Ramswamy. 1998. Structures of an aromatic-ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase-naphthlene 1,2-dioxygenase. Structure 6:571-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan, A. A., and S. K. Walia. 1991. Expression, localization, and functional analysis of polychlorinated biphenyl degradation genes cbpABCD of Pseudomonas putida. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:1325-1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim, E., and G. J. Zylstra. 1999. Functional analysis of genes involved in biphenyl, naphthalene, phenanthrene, and m-xylene degradation by Sphingomonas yanoikuyae B1. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 23:294-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimura, M. 1980. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuhm, A. E., A Stolz, K. L. Nagai, and H.-J. Knackmuss. 1991. Purification and characterization of a 1,2-dihydroxynaphthalene dioxygenase from a bacterium that degrades naphthalenesulfonic acids. J. Bacteriol. 176:2439-2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurkela, S., H. Lehaslasiho, E. T. Palva, and T. H. Terri. 1988. Cloning, nucleotide sequence and characterization of genes encoding naphthalene dioxygenase of Pseudomonas putida strain NCIB9816. Gene 73:355-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laurie, A. D., and G. Lloyd-Jones. 1999. The phn genes of Burkholderia sp. strain RP007 constitute a divergent gene cluster for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon catabolism. J. Bacteriol. 181:531-540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malins, D. C., M. M. Krahn, D. W. Brown, L. D. Rhodes, M. S. Myers, B. B. McCain, and S. L. Chan. 1985. Toxic chemicals in marine sediment and biota from Mukilteo, Washington: relationships with hepatic neoplasms and other hepatic lesions in English sole (Parophrys vetulus). J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 74:487-494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marmur, J. 1961. A procedure for the isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid from microorganisms. J. Mol. Biol. 3:208-218. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mason, J. R., and R. Cammack. 1992. The electron-transport proteins of hydroxylating bacterial dioxygenases. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 46:277-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meador, J. P., J. E. Stein, W. L. Reichert, and U. Varanasi. 1995. Bioaccumulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by marine organisms. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 143:79-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Misawa, N., K. Shindo, H. Takahashi, H. Suenaga, K. Iguchi, H. Okazaki, S. Harayama, and K. Furukawa. 2002. Hydroxylation of various molecules including heterocyclic aromatics using recombinant Escherichia coli cells expressing modified biphenyl dioxygenase genes. Tetrahedron 58:9605-9612. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakai, Y., and F. Yamada. 1978. Carbon-13 NMR studies of a series of benzylphenols. Org. Magn. Reson. 11:607-611. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishioka, M., R. N. Castle, and M. L. Lee. 1985. Synthesis of monoamino- and monohydroxydibenzothiophenes. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 22:215-218. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nojiri, H., J.-W. Nam, M. Kosaka, K. Mori, T. Takemura, K. Furihata, H. Yamane, and T. Omori. 1999. Diverse oxygenations catalyzed by carboazole 1,9a-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. strain CA10. J. Bacteriol. 181:3105-3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nozaki, M. 1970. Metapyrocatechase (Pseudomonas). Methods Enzymol. 17A:522-525.

- 42.Parales, R. E., K. Lee, S. M. Resnick, H. Jiang, D. J. Lessner, and D. T. Gibson. 2000. Substrate specificity of naphthalene dioxygenase: effect of specific amino acids at the active site of the enzyme. J. Bacteriol. 182:1641-1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pinyakong, O., H. Habe, T. Yoshida, H. Nojiri, and T. Omori. 2003. Identification of three novel salicylate 1-hydroxylases involved in the phenanthrene degradation of Sphingobium sp. strain P2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 301:350-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Romine, M. F., J. K. Fredrickson, and S. M. Li. 1999. Induction of aromatic catabolic activity in Sphingomonas aromaticivorans strain F199. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 23:303-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romine, M. F., L. C. Stillwell, K.-K. Wong, S. J. Thurston, E. C. Sisk, C. Sensen, T. Gaasterland, J. K. Fredrickson, and J. D. Saffer. 1999. Complete sequence of a 184-kilobase catabolic plasmid from Sphingomonas aromaticivorans F199. J. Bacteriol. 181:1585-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saito, A., T. Iwabuchi, and S. Harayama. 2000. A novel phenanthrene dioxygenase from Nocardioides sp. strain KP7: expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182:2134-2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sakurai, H., T. Tsukuda, and T. Hirao. 2002. Pd/C as a reusable catalyst for the coupling reaction of halophenols and arylboronic acids in aqueous media. J. Org. Chem. 67:2721-2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 50.Sato, S. I., J. W. Nam, K. Kasuga, H. Nojiri, H. Yamane, and T. Omori. 1997. Identification and characterization of genes encoding carbazole 1,9a-dioxygenase in Pseudomonas sp. strain CA10. J. Bacteriol. 179:4850-4858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shiaris, M. P. 1989. Phenanthrene mineralization along a natural salinity gradient in an urban estuary, Boston Harbor, Massachusetts. Microb. Ecol. 18:135-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shiaris, M. P. 1989. Seasonal biotransformation of naphthalene, phenanthrene, and benzo(a)pyrene in surficial estuarine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:1391-1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shindo, K., Y. Ohnishi, H.-K. Chun, H. Takahashi, M. Hayashi, A. Saito, K. Iguchi, K. Furukawa, S. Harayama, S. Horinouchi, and N. Misawa. 2001. Oxygenation reactions of various tricyclic fused aromatic compounds using Escherichia coli and Streptomyces lividans transformants carrying several arene dioxygenase genes. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 65:2472-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sikkema, J., J. A. M. deBont, and B. Poolman. 1995. Mechanisms of membrane toxicity of hydrocarbons. Microbiol. Rev. 59:201-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simon, M. J., T. D. Osslund, R. Saunders, B. D. Ensley, S. Suggs, A. Harcourt, W.-C. Suen, D. L. Cruden, D. T. Gibson, and G. J. Zylstra. 1993. Sequence of genes encoding naphthalene dioxygenase in Pseudomonas putida strains G7 and NCIB9816-4. Gene 127:31-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taira, K., N. Hayase, N. Arimura, S. Yamashita, T. Miyazaki, and K. Furukawa. 1988. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase gene from the PCB-degrading strain of Pseudomonas paucimobilis Q1. Biochemistry 27:3990-3996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takizawa, N., N. Kaida, S. Torigoe, T. Moritani, T. Sawada, S. Satoh, and H. Kiyohara. 1994. Identification and characterization of genes encoding polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon dioxygenase and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon dihydrodiol dehydrogenase in Pseudomonas putida OUS82. J. Bacteriol. 176:2444-2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thompson, J. D., D. G Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang, Y., P. C. K. Lau, and D. K. Button. 1996. A marine oligobacterium harboring genes known to be part of aromatic hydrocarbon degradation pathways of soil pseudomonads. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:2169-2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou, N.-Y., S. L. Fuenmayor, and P. A. Williams. 2001. nag genes of Ralstonia (formerly Pseudomonas) sp. strain U2 encoding enzymes for gentisate catabolism. J. Bacteriol. 183:700-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]