Abstract

Working with a Streptomyces albus strain that had previously been bred to produce industrial amounts (10 mg/ml) of salinomycin, we demonstrated the efficacy of introducing drug resistance-producing mutations for further strain improvement. Mutants with enhanced salinomycin production were detected at a high incidence (7 to 12%) among spontaneous isolates resistant to streptomycin (Strr), gentamicin, or rifampin (Rifr). Finally, we successfully demonstrated improvement of the salinomycin productivity of the industrial strain by 2.3-fold by introducing a triple mutation. The Strr mutant was shown to have a point mutation within the rpsL gene (encoding ribosomal protein S12). Likewise, the Rifr mutant possessed a mutation in the rpoB gene (encoding the RNA polymerase β subunit). Increased productivity of salinomycin in the Strr mutant (containing the K88R mutation in the S12 protein) may be a result of an aberrant protein synthesis mechanism. This aberration may manifest itself as enhanced translation activity in stationary-phase cells, as we have observed with the poly(U)-directed cell-free translation system. The K88R mutant ribosome was characterized by increased 70S complex stability in low Mg2+ concentrations. We conclude that this aberrant protein synthesis ability in the Strr mutant, which is a result of increased stability of the 70S complex, is responsible for the remarkable salinomycin production enhancement obtained.

Improvement of the productivity of commercially viable microbiotic strains is an important field in microbiology, especially since wild-type strains isolated from nature usually produce only a low level (1∼100 μg/ml) of antibiotics. A great deal of effort and resources is therefore committed to improving antibiotic-producing strains to meet commercial requirements. Current methods of improving the productivity of industrial microorganisms range from the classical random approach to using highly rational methods, for example metabolic engineering. Although classical methods are still effective even without using genomic information or genetic tools to obtain highly productive strains, these methods are always time- and resource-intensive (27, 31).

Members of the genus Streptomyces produce a wide variety of secondary metabolites that include about half of the known microbial antibiotics. We reported previously that a certain str mutation that confers streptomycin resistance is able to give rise to secondary metabolite production in Streptomyces lividans and Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) (3, 20, 24). Later, we demonstrated that the introduction of a specific str mutation, as well as a gentamicin resistance-producing mutation (gen), into other bacterial genera gave rise to a marked antibiotic productivity increase, thus further elucidating the antibiotic production mechanism in S. coelicolor A3(2) (6). Furthermore, by inducing a mutation that confers resistance to rifampin, we were able to restore the impaired production of antibiotics in the relA and relC mutants of S. coelicolor A3(2) (8, 11, 29). Recently, the str mutation in Pseudomonas putida has also demonstrated an ability to tolerate organic chemicals (5). These results offer some alternative strategies for the improvement of antibiotic productivity. Next, we demonstrated that by inducing combined drug resistance-producing mutations, we can continuously increase the production of an antibiotic in a stepwise manner (7). These single, double, and triple mutations displayed, in hierarchical order, a remarkable increase in the production of actinorhodin. However, unlike wild-type strains, improvement of industrial strains is, in general, much more difficult as productivity has already been raised by various genetic and physiological approaches. Therefore, we attempted in the present study to expand our novel approaches to the improvement of antibiotic productivity to these industrial strains by focusing on methods by which to induce combined drug resistance-producing mutations. We also clarified some biochemical aspects in these mutant strains, uncovering some surprising facts with respect to a cell's ability to synthesize proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and preparation of mutants.

Strain SAM-X was derived from wild-type strain JCM 4703 by working with various mutagens (UV, N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine [NTG], nitrogen mustard, etc.) for several years. Spontaneous streptomycin-resistant (Strr), gentamicin-resistant (Genr), or rifampin-resistant (Rifr) mutants were obtained from colonies that grew within 7 days after spores (or cells) were spread on GYM (19) agar containing various concentrations of the above drugs.

Media and growth condition.

GYM and SPY media were described previously (19). All mutant strains were stored after cultivation on spore formation medium (SFM; 1% soybean meal, 4% glucose, 0.1% NaCl, 0.01% MgSO4, 0.1% CaCO3, 2% agar powder) after single-colony isolation. Before inoculation, the strains were incubated at 30°C for 4 to 7 days on a GYM plate to allow abundant sporulation. Precultivation was carried out in a 25-ml test tube containing 2 ml of SPY medium and incubated at 30°C for 48 h on a reciprocal shaker (350 rpm). The preculture (1 ml) was inoculated into 100-ml flasks containing 10 ml of production medium [13% soybean oil, 0.13% wheat bran, 0.78% wheat germ, 0.65% soybean meal, 0.2% NaCl, 0.2% KCl, 0.02% MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.3% (NH4)2SO4, 0.02% K2HPO4, 0.5% CaCO3]. Incubation was carried out on a rotary shaker (220 rpm) at 30°C for 10 days. A 2-ml volume of water was added at day 5 to prevent evaporation.

Assay for salinomycin.

Salinomycin was extracted from the whole broth by addition of and mixing with an equal volume of methanol. The extracts were mixed with an equal volume of vanillin solution (3% vanillin, 1.5% H2SO4, 50% methanol) and then incubated at 70°C for 20 min. After centrifugation, the amount of salinomycin was determined by measurement of the optical density of the supernatants at 522 nm. A bioassay with Staphylococcus aureus 209P as a test organism was also carried out to confirm the results of the chemical assay.

Mutation analysis of the rpsL and rpoB genes.

The rpsL gene fragment from the Strr mutants was obtained by PCR with the mutants' genomic DNA as a template and synthetic oligonucleotide primers P1 (forward; 5′-CAGCAGCTSGTSCGSAAG-3′), P2 (forward; 5′-ACSCCCAAGAAGCCCAA-3′), and P3 (reverse; 5′-GCSTTCGTCCGSGCSGCSTCG-3′), which were designed from the sequence for S. lividans and S. coelicolor A3(2). The partial rpoB fragment for the Rifr mutants was obtained by PCR with the mutants' genomic DNA as a template and synthetic oligonucleotide primers P4 (forward; 5′-GGCCCTCGGCTGGACCACCG-3′) and P5 (reverse; 5′-CCCGAACATCGGTCTGATCG-3′), which were designed from the sequence for S. coelicolor A3(2). The PCR and DNA sequencing methods used were described previously (7, 8, 29).

In vitro translation assay.

We used the poly(U)-directed cell-free translation system described by Legault-Demare and Chambliss (14), with some modifications. Cells of S. albus strains grown to various growth phases in GYM medium were harvested by filtration with filter paper and washed with standard buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.7), 10 mM magnesium acetate, 30 mM ammonium acetate, 6 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol] containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. After the cells were ground with abrasive aluminum oxide powder, ribosomes (precipitant; designated P-150) and supernatant solution (designated S-150) were obtained by ultracentrifugation (150,000 × g, 3 h). The ribosome fraction was washed once with standard buffer. Ribosomes and S-150 were then dialyzed against a 60-fold volume of standard buffer for 6 h, divided into small aliquots, frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until used for experiments. All of the above-described procedures were performed at 4°C. Ribosome mixtures containing 5 A260 units of ribosome per ml, 0.5 mg of protein from S-150 per ml, 55 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 1 mM dithiothreitol, 210 mM potassium acetate, 27.5 mM ammonium acetate, 10.7 mM magnesium acetate, and 68 μM folinic acid were preincubated at 30°C for 10 min to remove the endogenous mRNA. The reaction mixture (100 μl) contained 60 μl of the ribosome mixture, 1.2 mM ATP, 0.8 mM GTP, 0.64 mM 3′,5′-cyclic AMP, 80 mM creatine phosphate, 25 μg of creatine kinase, 0.05 U of RNase inhibitor (recombinant solution; Wako), 15 μg of Escherichia coli tRNA, 20 amino acids (but not phenylalanine) at 0.4 mM each, 75 μg of poly(U), and 0.22 μM [14C]phenylalanine (0.01 μCi). Reactions were started by addition of poly(U), and the reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for the appropriate time (e.g., 10 to 20 min). Reactions were stopped by addition of 1 ml of 10% trichloroacetic acid, followed by boiling at 100°C for 15 min. Precipitated proteins were collected on nitrocellulose filters, and incorporation of [14C]phenylalanine into the acid-insoluble fraction was determined with a liquid scintillation counter.

Density gradient sedimentation of 70S ribosome.

Precipitated ribosomes (P-150; see above) were suspended in standard buffer lacking glycerol but containing the specified concentrations of magnesium acetate. The samples (each containing 170 μg of protein) were laid onto a 10 to 40% liner sucrose gradient in the same Mg2+ concentration buffer for each sample. The gradients were centrifuged (180,000 × g, 4 h) in a Beckman SW41 rotor at 4°C. The distribution of ribosomes on the gradients was recorded with a BIOCOMP Position Gradient Fractionator (Towa Kagaku) equipped with an ATTO Bio-Mini UV Monitor set at 254 nm.

RESULTS

Construction of drug-resistant mutants.

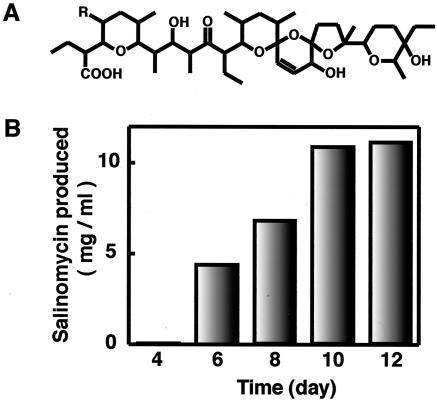

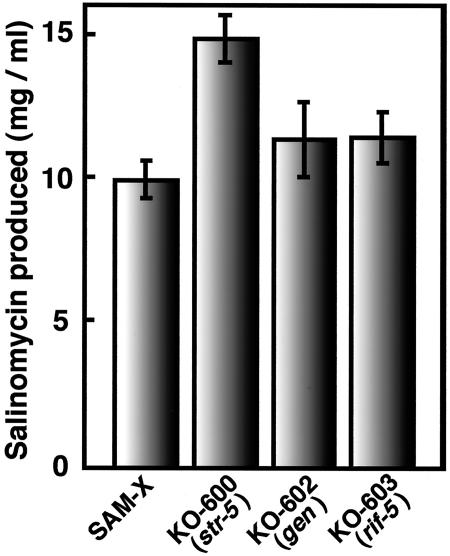

S. albus industrial strain SAM-X was derived from wild-type strain JCM 4703 by sequential treatment with mutagens (UV, NTG, nitrogen mustard, etc.) and is able to produce a high level (10 mg/ml) of salinomycin (Fig. 1A) when cultured for 10 days in an appropriate medium (Fig. 1B). In comparison, wild-type strain 4703 produces only a small amount (250 μg/ml) of salinomycin. First, we introduced a single drug resistance-producing mutation into strain SAM-X. Spontaneous mutants resistant to streptomycin, gentamicin, or rifampin developed when SAM-X spores were spread and incubated on GYM agar containing each drug at 5 to 30 times the MIC. Then we examined the amount of salinomycin produced from these drug-resistant mutants (we tested 40 isolates for each drug). Mutants with enhanced salinomycin production were detected at a high frequency (8 to 12%) from the Strr, Genr, or Rifr mutant isolates. The most productive mutant isolated from each drug was 1.2 to 1.5 times as productive as the parental strain (SAM-X) (Fig. 2), although the majority of these drug-resistant mutants produced a smaller amount of salinomycin than did the parental strain. The most productive strains were designated KO-600, KO-602, and KO-603, respectively (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Structure of salinomycin (A) and time course of salinomycin production by S. albus industrial strain SAM-X (B).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of salinomycin production by drug-resistant mutants KO-600, KO-602, and KO-603. Incubation was carried out in production medium for 10 days. Error bars represent standard deviations.

TABLE 1.

Strains of S. albus used in this study

| Strain | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| JCM4703 | Prototrophic wild type | Japan Collection of Microorganisms |

| SAM-X | Industrial strain | N. Otake |

| KO-600 | str-5 | Streptomycin-resistant mutant of SAM-X |

| KO-601 | str-7 | Streptomycin-resistant mutant of SAM-X |

| KO-602 | gen | Gentamicin-resistant mutant of SAM-X |

| KO-603 | rif-5 | Rifampin-resistant mutant of SAM-X |

| KO-604 | rif-8 | Rifampin-resistant mutant of SAM-X |

| KO-605 | str-5 gen | Gentamicin-resistant mutant of KO-600 |

| KO-606 | str-5 gen rif | Rifampin-resistant mutant of KO-605 |

| KO-608 | str-5 gen rif-5 | Rifampin-resistant mutant of KO-605 |

| KO-610 | str-5 gen rif | Rifampin-resistant mutant of KO-605 |

Mutational analysis.

Streptomycin resistance frequently results from a mutation in the rpsL gene, which encodes ribosomal protein S12 (2, 4, 15). Likewise, rifampin resistance results from a mutation in the rpoB gene, which encodes the β subunit of RNA polymerase (9). We sequenced and compared the wild-type and mutant rpsL and rpoB genes. As summarized in Table 2, the Strr mutant with enhanced salinomycin production (KO-600) contained a mutation within the rpsL gene resulting in an alteration of Lys-88 to Arg. On the other hand, four Strr mutants showing a reduced ability to produce salinomycin (as represented by strain KO-601) displayed one of the following rpsL mutations: K43N, K43R, K43M, or K43T. Apparently, these rpsL mutations were ineffective for increasing salinomycin production. In Rifr mutant KO-603, a mutation was detected in the rpoB gene that altered Ser-442 to Phe, while the other Rifr mutant, KO-604, showing no enhancement in salinomycin production, displayed a distinctive rpoB mutation that altered Ser-442 to Tyr (Table 2). Although gentamicin and streptomycin are classified as aminoglycoside antibiotics, Genr mutant strain KO-602 demonstrated no mutation in the rpsL gene.

TABLE 2.

Summary of mutations of S. albus rps gene resulting in amino acid exchange

| Strain | Altered gene | Position of mutationa | Amino acid exchange | Level of resistance (μg/ml) to:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STRb | GEN | RIF | ||||

| SAM-X | 0.1 | 0.1 | 5 | |||

| KO-600 | rpsL | 263 A→G | Lys-88→Arg | 7 | 0.1 | 5 |

| KO-601 | rpsL | 128 A→G | Lys-43→Arg | 50 | 0.1 | 5 |

| KO-602 | NDc | 0.1 | 0.1∼0.15 | 5 | ||

| KO-603 | rpoB | 1325 C→T | Ser-442→Phe | 0.1 | 0.1 | >500 |

| KO-604 | rpoB | 1325 C→A | Ser-442→Tyr | 0.1 | 0.1 | >500 |

| KO-605 | NDd | 7 | 0.2 | 5 | ||

| KO-606 | NDe | 7 | 0.2 | 20 | ||

| KO-608 | rpoB | 1325 C→T | Ser-442→Phe | 7 | 0.2 | >500 |

| KO-610 | NDe | 7 | 0.2 | 5∼7 | ||

Numbering originates at the start codon of the open reading frame.

STR, GEN, and RIF, streptomycin, gentamicin, and rifampcin, respectively.

ND, mutation not detected in rpsL.

ND, no additional mutation detected in rpsL.

ND, mutation not detected in rpoB.

Construction of combined-resistance mutants.

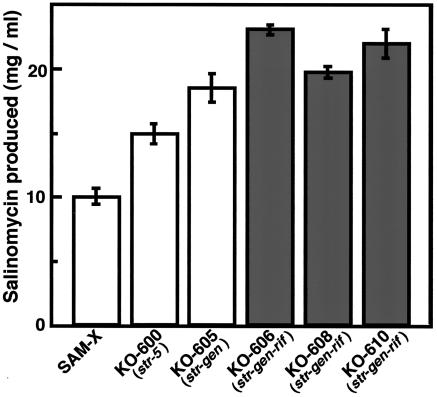

Next, we constructed double mutants by generating spontaneous Genr mutants from Strr mutant KO-600. The frequency of double mutants producing a greater amount of salinomycin was as high as 7%, and the most productive mutant detected displayed a 1.25-fold improvement over strain KO-600 (Fig. 3). This new mutant was designated strain KO-605.

FIG. 3.

Enhanced ability of single-, double-, and triple-drug-resistant mutants to produce salinomycin. Incubation was carried out for 10 days.

Triple mutants were constructed by generating spontaneous Rifr mutants from Strr Genr double mutant KO-605. The frequency of triple mutants producing a greater amount of salinomycin was 8%, and the most productive mutant detected demonstrated a 1.26-fold improvement over the parental double-mutant strain. Three representative triple mutants were designated KO-606, KO-608, and KO-610 (Table 1 and Fig. 3). No cross-resistance was detected among mutants resistant to streptomycin, gentamicin, or rifampin (Table 2). Finally, compared to the original industrial strain, SAM-X, we successfully achieved a more-than-twofold salinomycin productivity increase by introducing combined-resistance mutations. Strain KO-608 displayed an rpoB mutation resulting in an alteration of Ser-442 to Phe (same mutation as KO-603), whereas no mutation in the rpoB gene was detected in KO-606 and KO-610.

Physiological characterization of mutants.

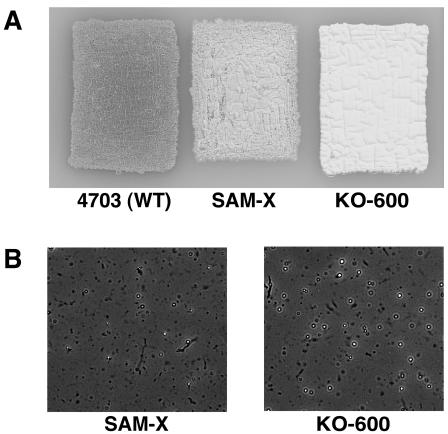

One of the important aspects of industrial microbiology is the ability to form aerial mycelium and spores, since the stability of the mutant's phenotype often depends on the ability to form spores. However, introduction of mutations frequently results in severe sporulation impairment. As examined on SFM agar plate cultures, our highly productive single, double, and triple mutants (KO-600, KO-605, and KO-606) not only grew as well as the parental strain (SAM-X) but produced even more abundant aerial mycelia and spores, as shown for strain KO-600 in Fig. 4A. Strain KO-600 also demonstrated an increased ability to form submerged spores when cultured in liquid medium (Fig. 4B). Thus, streptomycin resistance-producing mutation K88R is effective not only for increasing salinomycin production but also for enhancing morphological development in S. albus.

FIG. 4.

Morphological development of parent and mutant strains. (A) Ability to produce aerial mycelium in wild-type (4703), industrial (SAM-X), and Strr mutant (KO-600) strains. Spores were inoculated on an SFM agar plate and incubated at 30°C for 6 days. (B) Microscopic observation of submerged spores after 14 days of cultivation in production medium.

Strr strain KO-600 displays aberrant protein synthesis.

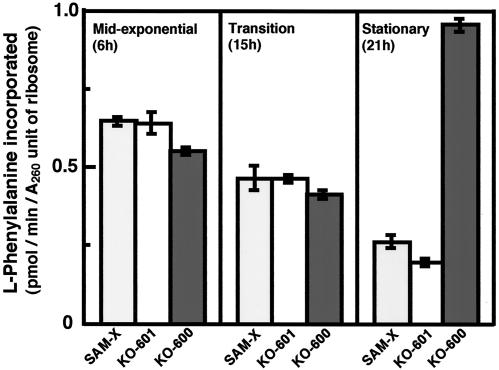

Recent work in our laboratory has demonstrated that certain rpsL mutations that activate antibiotic production in S. coelicolor A3(2) confer an aberration of the cell's protein synthesis mechanism. Namely, an rpsL mutation (altering Lys-88 to Glu) exhibited enhanced protein synthesis activity during the stationary phase, as determined by in vivo translation assays (Y. Okamoto-Hosoya, T. Hosaka, and K. Ochi, unpublished data). We therefore reasoned that S. albus Strr strain KO-600 might give rise to similar results. To assess this possibility, the industrial strain (SAM-X) and KO-600 (str-5), together with KO-601 (str-7), which was used as a reference strain, were grown to various growth phases. Cells harvested at the mid-exponential phase, transition phase, and stationary phase were disrupted with aluminum oxide powder. After preparation of the ribosome fraction and the S-150 fraction, we performed an in vitro translation assay with the poly(U)-directed cell-free translation system (see Materials and Methods). Parental strain SAM-X demonstrated a correlation between the decrease in translation activity and cell aging. Surprisingly, Strr mutant KO-600 demonstrated enhanced translation activity at the stationary phase (Fig. 5). This activity was fivefold greater than that of parental strain SAM-X. In contrast, Strr mutant KO-601 displayed a pattern similar to that of parental strain SAM-X. These results were reproducible in separate experiments. The enhanced translation activity was detected when cells of KO-605 and KO-606 were used instead of KO-600 (data not shown). Thus, enhanced translation activity in the stationary phase is a distinguishing characteristic of Strr mutant strains with the str-5 (K88R) mutation.

FIG. 5.

In vitro translation activities of ribosomes prepared from cells at various growth phases. Strains were grown in GYM medium at 30°C. Samples were taken at the indicated growth phases, and in vitro translation activities were determined with the poly(U)-directed cell-free translation system (see Materials and Methods). Error bars represent standard deviations.

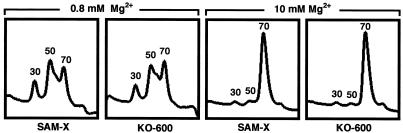

The K88R mutant ribosome forms a more stable 70S complex.

The topography of amino acid-starved ribosomes has been studied in E. coli with an electron microscope. Importantly, starvation for an essential amino acid induces spatial septation of the subunits in the ribosome, indicating that such ribosomes are more open than those in growing cells (21, 30). It has also been reported that ribosomes from methionine-starved cells are structurally unstable in the presence of a low concentration of Mg2+, suggesting that open-form ribosomes are structurally unstable (23). We reasoned that the K88R mutant ribosomes can keep a tighter and closer intersubunit structure, thus leading to active protein synthesis during the late growth phase. To assess this hypothesis, we prepared ribosomes from parental strain SAM-X and the two Strr mutants (KO-600 and KO-601) and examined the stability of the 70S complex in low and high concentrations of Mg2+. Most of the ribosomes existed in the 70S form at a high concentration (10 mM) of Mg2+, but a significant amount of the 70S complexes dissociated into 30S and 50S subunits at a low concentration (0.1 to 0.8 mM) of Mg2+. Strikingly, the K88R mutant ribosomes from KO-600 displayed a greater 70S complex fraction than did the wild-type ribosomes at the low Mg2+ concentration. A typical result obtained with an Mg2+ concentration of 0.8 mM is presented in Fig. 6. The other Strr mutant, KO-601, which possesses the mutant ribosome K43R, did not show an increased 70S complex fraction (data not shown). The K88R mutant ribosome is thus characterized by a more stable 70S complex under the low-salt stress condition.

FIG. 6.

Pattern of dissociation of the 70S complex into 30S and 50S subunits at different concentrations of Mg2+.

DISCUSSION

Working with a highly salinomycin-productive industrial S. albus strain, we successfully demonstrated the efficacy of inducing combined drug resistance-producing mutations to improve antibiotic production. This method not only results in a remarkable increase in salinomycin productivity (2.3-fold by a triple mutation) but also makes possible the generation of positive mutations at a high frequency (7 to 12%). Although much progress has been made in enhancing the productivity of antibiotic-producing strains (12, 13), our method is characterized by the host cell's amenability (generation of spontaneous drug resistance-producing mutations) and the method's applicability to a number of microorganisms (6-8, 24). It should also be emphasized that combined drug resistance-producing mutations (triple mutation) caused no impairment of growth and sporulation under the conditions tested. Rather, the ability to produce aerial mycelium and spores was, in fact, enhanced (Fig. 4).

Strr mutant KO-600, which showed a high level of salinomycin production, contained a mutation (K88R) in the rpsL gene. Although we did not attempt to identify the mutation in the present study, gentamicin resistance is known to result from a mutation in the rplF gene, which codes for the ribosomal L6 protein (10). The action of streptomycin on bacterial ribosomes has been studied in great detail (1, 28), and among the numerous effects attributed to this drug, misreading of mRNA codons is the best known. Gentamicin belongs to the kanamycin class of aminoglycosides but is structurally different from streptomycin. It is well known that S12 mutations, which can confer streptomycin resistance, can in general increase the accuracy of protein synthesis. More recently, defined regions of the 16S rRNA have also come to be associated with the ribosome's accuracy function (16, 18, 22). It is notable that translational accuracy can also be affected by two components of the 50S subunit, ribosomal protein L6 and the 2660 loop region of the 23S rRNA. Mutations have been identified in these components that result in a decreased translation rate, greater accuracy of protein synthesis, and increased resistance to many of the misreading-inducing aminoglycoside antibiotics, in particular, gentamicin (17, 26).

It was striking that Strr mutant KO-600 revealed high translation activity at the stationary phase as determined with the in vitro translation assay system (Fig. 5). This high translation activity could be a reason why Strr mutant KO-600 is capable of producing a greater amount of salinomycin. The aberrant protein synthesis ability of mutant KO-600 resulted presumably from a more stable ribosome structure, as demonstrated in the presence of a low Mg2+ concentration (Fig. 6). Antibiotic production, including salinomycin production, usually commences at the late growth phase (i.e., transition phase or stationary phase). Therefore, the enhanced protein synthesis ability at late growth phase would promote the initiation processes (i.e., formation of positive regulatory proteins for antibiotic gene expression) or biosynthetic processes (or both). This notion can be supported by the fact that Strr mutant KO-601, which demonstrated no increased salinomycin production, did not exhibit enhanced translation activity at the stationary phase (Fig. 5). Like Strr mutant KO-600, certain Genr mutants of S. lividans, which demonstrated activated antibiotic production, displayed high translation activity at the stationary phase, as demonstrated by in vitro translation experiments (Hosaka and Ochi, unpublished results). In E. coli, the rate of protein synthesis has been reported to be reduced by more than 90% when cells were starved for amino acids (25). Thus, the aberrant protein synthesis ability of Strr mutant KO-600 is quite distinguishable from previously conducted protein synthesis studies with wild-type strains.

A point mutation (rif-5) found in mutants KO-603 and KO-608 corresponds to a previously known position (9) that confers rifampin resistance. Although no mutations were detected in the rpoB gene for strains KO-606 and KO-610, these mutant strains may harbor a mutation in an RNA polymerase component other than the β subunit, such as the β′ subunit. It is reasonable to consider that the increased salinomycin production brought about by the Rifr mutation is based at least partly on the independence from ppGpp for initiation of secondary metabolism. Thus, the mutant RNA polymerase may function by mimicking the ppGpp-bound form, eventually leading to enhancement of the initiation process for antibiotic production (11, 29). Alternatively, the mutant RNA polymerase may have different promoter selectivity that is capable of activating different pathways for activating antibiotic biosynthesis. In summary, our novel breeding approach is based on two different aspects, modulation of the translational apparatus by induction of Strr and Genr mutations and modulation of the transcriptional apparatus by induction of a Rifr mutation. It is worth mentioning that modulation of these two mechanisms may function cooperatively to increase antibiotic productivity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Organized Research Combination System of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cundliffe, E. 1990. Recognition sites for antibiotics within rRNA, p. 479-490. In W. E. Hill, A. Dahlberg, R. A. Garrett, P. B. Moore, D. Schlessinger, and J. R. Warner (ed.), The ribosome: structure, function, and evolution. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 2.Finken, M., P. Kirschner, A. Meier, A. Wrede, and E. C. Bottger. 1993. Molecular basis of streptomycin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: alterations of the ribosomal protein S12 gene and point mutations within a functional 16S ribosomal RNA pseudoknot. Mol. Microbiol. 9:1239-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hesketh, A., and K. Ochi. 1997. A novel method for improving Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) for production of actinorhodin by introduction of rpsL (encoding ribosomal protein S12) mutations conferring resistance to streptomycin. J. Antibiot. 50:532-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Honore, N., and S. T. Cole. 1994. Streptomycin resistance in mycobacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:238-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hosokawa, K., N. H. Park, T. Inaoka, Y. Itoh, and K. Ochi. 2002. Streptomycin-resistant (rpsL) or rifampicin-resistant (rpoB) mutation in Pseudomonas putida KH146-2 confers enhanced tolerance to organic chemicals. Environ. Microbiol. 4:703-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hosoya, Y., S. Okamoto, H. Muramatsu, and K. Ochi. 1998. Acquisition of certain streptomycin-resistant (str) mutations enhances antibiotic production in bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2041-2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu, H., and K. Ochi. 2001. Novel approach for improving the productivity of antibiotic-producing strains by inducing combined resistant mutations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1885-1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu, H., Q. Zhang, and K. Ochi. 2002. Activation of antibiotic biosynthesis by specified mutations in the rpoB gene (encoding the RNA polymerase β subunit) of Streptomyces lividans. J. Bacteriol. 184:3984-3991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin, D. J., and C. A. Gross. 1988. Mapping and sequencing of mutations in the Escherichia coli rpoB gene that lead to rifampicin resistance. J. Mol. Biol. 202:45-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuhberger, R., W. Piepersberg, A. Petzet, P. Buckel, and A. Bock. 1979. Alteration of ribosomal protein L6 in gentamicin-resistant strains of Escherichia coli. Effects on fidelity of protein synthesis. Biochemistry 18:187-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lai, C., J. Xu, Y. Tozawa, Y. Okamoto-Hosoya, X. Yao, and K. Ochi. 2002. Genetic and physiological characterization of rpoB mutations that activate antibiotic production in Streptomyces lividans. Microbiology 148:3365-3373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lal, R., R. Khanna, H. Kaur, M. Khanna, N. Dhingra, S. Lal, K. H. Gartemann, R. Eichenlaub, and P. K. Ghosh. 1996. Engineering antibiotic producers to overcome the limitations of classical strain improvement programs. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 22:201-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee, S. H., and Y. T. Rho. 1999. Improvement of tylosin fermentation by mutation and medium optimization. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 28:142-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Legault-Demare, L., and G. H. Chambliss. 1974. Natural messenger ribonucleic acid-directed cell-free protein-synthesizing system of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 120:1300-1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meier, A., P. Kirschner, F. C. Bange, U. Vogel, and E. C. Bottger. 1994. Genetic alterations in streptomycin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis: mapping of mutations conferring resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:228-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melancon, P., C. Lemieux, and L. Brakier-Gingras. 1988. A mutation in the 530 loop of Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA causes resistance to streptomycin. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:9631-9639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melancon, P., W. E. Tapprich, and L. Brakier-Gingras. 1992. Single-base mutations at position 2661 of Escherichia coli 23S rRNA increase efficiency of translational proofreading. J. Bacteriol. 174:7896-7901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montandon, P. E., R. Wagner, and E. Stutz. 1986. E. coli ribosomes with a C912 to U base change in the 16S rRNA are streptomycin resistant. EMBO J. 5:3705-3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ochi, K. 1987. Metabolic initiation of differentiation and secondary metabolism by Streptomyces griseus: significance of the stringent response (ppGpp) and GTP content in relation to A factor. J. Bacteriol. 169:3608-3616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ochi, K., D. Zhang, S. Kawamoto, and A. Hesketh. 1997. Molecular and functional analysis of the ribosomal L11 and S12 protein genes (rplK and rpsL) of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Gen. Genet. 256:488-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ofverstedt, L. G., K. Zhang, S. Tapio, U. Skoglund, and L. A. Isaksson. 1994. Starvation in vivo for aminoacyl-tRNA increases the spatial separation between the two ribosomal subunits. Cell 79:629-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powers, T., and H. F. Noller. 1991. A functional pseudoknot in 16S ribosomal RNA. EMBO J. 10:2203-2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sells, B. H., and H. L. Ennis. 1970. Polysome stability in relaxed and stringent strain of Escherichia coli during amino acid starvation. J. Bacteriol. 102:666-671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shima, J., A. Hesketh, S. Okamoto, S. Kawamoto, and K. Ochi. 1996. Induction of actinorhodin production by rpsL (encoding ribosomal protein S12) mutations that confer streptomycin resistance in Streptomyces lividans and Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Bacteriol. 178:7276-7284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorensen, M. A., K. F. Jensen, and S. Pedersen. 1994. High concentrations of ppGpp decrease the RNA chain growth rate. Implications for protein synthesis and translational fidelity during amino acid starvation in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 236:441-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tapprich, W. E., and A. E. Dahlberg. 1990. A single base mutation at position 2661 in E. coli 23S ribosomal RNA affects the binding of ternary complex to the ribosome. EMBO J. 9:2649-2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vinci, V. A., and G. Byng. 1999. Manual of industrial microbiology and biotechnology. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 28.Wallace, B. J., P.-C. Tai, and B. D. Davies. 1979. Streptomycin and related antibiotics, p. 272-303. In F. E. Hahn (ed.) Antibiotics. V. Mechanism of action of antibacterial agents. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y.

- 29.Xu, J., Y. Tozawa, C. Lai, H. Hayashi, and K. Ochi. 2002. A rifampicin resistance mutation in the rpoB gene confers ppGpp-independent antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Genet. Genomics 268:179-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang, K., L. Pettersson-Landen, M. G. Fredriksson, L. G. Ofverstedt, U. Skoglund, and L. A. Isaksson. 1998. Visualization of a large conformation change of ribosomes in Escherichia coli cells starved for tryptophan or treated with kirromycin. Exp. Cell Res. 238:335-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang, Y. X., K. Perry, V. A. Vinci, K. Powell, W. P. Stemmer, and S. B. del Cardayre. 2002. Genome shuffling leads to rapid phenotypic improvement in bacteria. Nature 415:644-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]