Abstract

The Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH) is a partnership between Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital, Moi University School of Medicine, and a consortium of universities led by Indiana University. AMPATH has over 50 000 patients in active care in 17 main clinics around western Kenya.

Despite antiretroviral therapy, many patients were not recovering their health because of food insecurity. AMPATH therefore established partnerships with the World Food Program and United States Agency for International Development and began high-production farms to complement food support.

Today, nutritionists assess all AMPATH patients and dependents for food security and refer those in need to the food program. We describe the implementation, challenges, and successes of this program.

THERE IS A COMPELLING monotony to the maps of sub-Saharan Africa that delineate high-prevalence areas of HIV, poverty, and food insecurity—each map might literally be superimposed on the others. This overlap is not a coincidence. The interplay between HIV, poverty, and food insecurity is increasingly recognized as a major contributor to the devastation now challenging much of sub-Saharan Africa.1–3 It is unlikely that any scientific evidence can depict the actual human and economic costs to societies burdened by the disability and death of young adults, endless numbers of widows, unparalleled numbers of orphans, and falling school attendance by an expanding number of malnourished, vulnerable children. Responses targeting only the rapid scale up of antiretroviral therapy are unlikely to meet the needs of many of the patients they serve. To those on the front lines of HIV care in sub-Saharan Africa, it is clear that food security and poverty reduction are essential components of a meaningful response to the havoc wrought by the HIV pandemic.1,4,5 Medical care is necessary but insufficient, whereas health care attends to all these sectors.

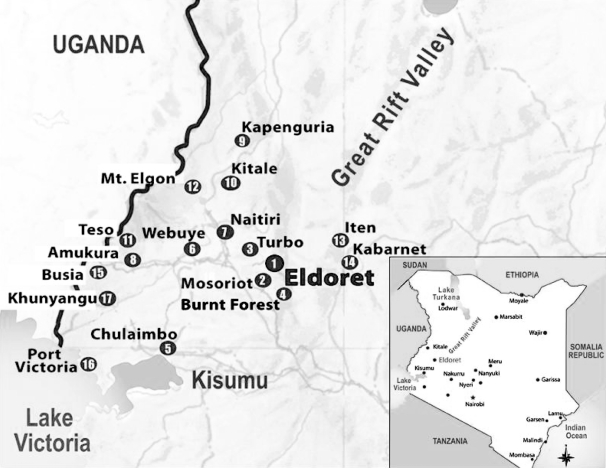

In 2001, Kenya's second national referral hospital, Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital; its second medical school, Moi University School of Medicine; and a consortium of medical schools from the United States led by Indiana University School of Medicine initiated a bold response to the HIV pandemic in western Kenya. They launched the Academic Model for the Prevention and Treatment of HIV/AIDS now known as the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH), which has grown into one of Africa's largest and most rapidly growing HIV care programs.6,7 AMPATH is currently working in a network of 17 Ministry of Health facilities in western Kenya, including a national referral hospital, several district hospitals, subdistrict hospitals, and many rural health centers (Figure 1, Table 1). AMPATH is currently serving over 50 000 HIV-infected patients, half of whom are receiving combination antiretroviral treatment. Each month, approximately 2000 new patients are enrolled, roughly 40% to 50% of whom begin antiretroviral treatment.

FIGURE 1.

Map of western Kenya showing locations of Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH) clinics.

Note. Eldoret is the location of the program headquarters.

TABLE 1.

Proportion of Patients Identified as Food Insecure by AMPATH Clinics: Western Kenya, 2007

| Clinic Site | Type of Center | No. of Patients Enrolleda | Food Insecure, % |

| MTRH | National referral hospital | 17 781 | 39 |

| Mosoriot | Rural health center | 5329 | 40 |

| Turbo | Rural health center | 4103 | 30 |

| Burnt Forest | Rural health center | 2654 | 20 |

| Chulaimbo | Rural health center | 8105 | 40 |

| Webuye | Subdistrict hospital | 4508 | 20 |

| Naitiri | Rural health center | 1447 | 25 |

| Amukura | Rural health center | 1769 | 30 |

| Kapenguria | District hospital | 1168 | 44 |

| Kitale | District hospital | 5943 | 20 |

| Teso | District hospital | 1855 | 29 |

| Mount Elgon | District hospital | 708 | 28 |

| Iten | District hospital | 683 | 35 |

| Kabarnet | District hospital | 1083 | 40 |

| Busia | District hospital | 5814 | 30 |

| Port Victoria | Subdistrict hospital | 2257 | 50 |

| Khunyangu | Subdistrict hospital | 1831 | 50 |

| Total | 67 038 | 33.5b |

Note. Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare = AMPATH; MTRH = Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital.

As of January 1, 2008.

Mean percentage.

Early on, AMPATH care providers became acutely aware of the impact hunger and poverty were having on patients presenting for care and on the vulnerable members of their households, most notably children. AMPATH leaders decided to provide nutritional support for all food-insecure patients and dependents within their homes. That decision alone initiated a series of challenges for AMPATH that have proven just as complex as scaling up Kenya's largest antiretroviral delivery program. AMPATH is one of the first HIV care programs in sub-Saharan Africa to roll out comprehensive HIV treatment combined with extensive nutritional support for food-insecure patients and their dependents. We provide an overview of the program, including challenges, successes, and lessons learned, so others might be assisted in building their own food support programs.

The AMPATH Nutrition Program

Eligibility

A qualified nutritionist completes a standardized initial encounter form for all newly registered patients at each AMPATH site. The interview focuses on level of immune suppression, body mass index (or equivalent for children), socioeconomic status and circumstances, and patient's access to food in terms of both quantity and quality, using a version of the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale specifically adapted by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance project for use in developing countries.8 Determination of whether a patient and his or her dependents are food secure ultimately rests with the clinical judgment of the nutritionist. After considering all related variables, if the nutritionist feels that the patient or dependents are unlikely to meet minimal daily nutritional requirements, that family is judged food insecure. Once food insecurity is determined, the patient and all dependents in the home automatically qualify for food support for 6 months.

Careful assessment of individual homes showed that food insecurity extended beyond the food-insecure patient. AMPATH decided that it was unethical to offer food to only the index patient while children in the home lacked access to food. The decision was consistent with existing policies of the World Food Program. The nutritionist writes a “food prescription” that entitles the patient and dependents to a 1-month supply of food. The patient must return to the nutritionist monthly for a new prescription until 6 months are completed. At each monthly visit, the nutritionist reminds the patient how much time is left on the food prescription. Depending on the needs of the patient and family and the food supply, the nutritionist will provide up to 100% of caloric needs for the patient and dependents.

The proportion of patients eligible for food support varies widely among AMPATH sites (Table 1), but, in general, there is more food insecurity in rural areas. Rural populations in the far western part of the catchment area tend to have high poverty levels, small plots of land per family, and poor soil quality. In addition, these western sites have a higher proportion of widows entering care than the overall average within AMPATH of 25%. In Khunyangu, for example, 68% of women who have ever been married are widows at the time of their first visit, as are 46% in Port Victoria and 43% in Busia.

Food Demand

For a given day, week, or month, the total demand for food is defined as the sum of the food prescribed by nutritionists for all patients and their dependents throughout AMPATH for that period. Each food prescription records the quantity and type of food required for each household along with the day and location of anticipated pickup of food. As summarized in Table 2, AMPATH nutritionists, during 2007, assessed over 130 000 patients and their dependents for food insecurity (75% female, 85% aged 19 years or older), counseled 61 535 of them about nutrition, and enrolled 9623 new patients (plus an average of 4 dependents per patient) into the food program.

TABLE 2.

Summary of AMPATH Nutrition Program Activities, by Selected Demographics: Western Kenya, 2007

| Patients and Their Dependents Assessed for Food Insecurity, No. (%) | Patients and Their Dependents Counseled About Nutrition, No. (%) | Patients Enrolled to Receive Food, No. (%) | Patients Discharged From Food Program, No. (%) | |

| Total | 133 792 | 61 535 | 9 623 | 1 805 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 33 784 (25) | 17 573 (29) | 2 584 (27) | 499 (28) |

| Female | 100 008 (75) | 43 962 (71) | 7 039 (73) | 1 306 (72) |

| Age, y | ||||

| ≤5 | 12 562 (9) | 4 553 (7) | 852 (9) | 157 (9) |

| 6–18 | 8 181 (6) | 4 981 (8) | 1 232 (13) | 152 (8) |

| ≥19 | 113 049 (85) | 52 001 (85) | 7 539 (78) | 1 496 (83) |

Note. Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare = AMPATH.

Food Supply

To meet the major challenge of supplying sufficient food to meet patients’ needs, AMPATH uses a combination of production, donation, and purchase.

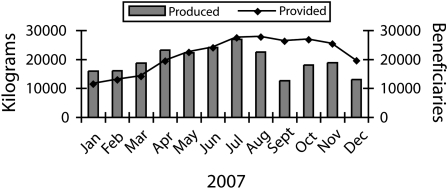

A key component of the AMPATH nutrition program is food production. AMPATH currently manages 6 farms; 4 are high-production, continuous-irrigation farms and 2 are teaching and demonstration farms that aim to demonstrate ways of increasing the yield in small plots owned by AMPATH patients. With a continuous source of water, these farms are able to produce a reliable, year-round supply of fresh vegetables. The combined monthly output of the continuous-irrigation farms is in excess of 20 metric tons of fresh produce (Figure 2). As orchards become more productive by mid-2009, it is hoped that these same farms will add an additional 4 metric tons of fresh fruit each month.

FIGURE 2.

Kilograms of food produced by the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH) nutrition program and the numbers of its beneficiaries: Western Kenya, 2007.

Note. A serious hailstorm negatively affected food production in October; Christmas and the lead-up to national elections affected it in December.

The major donors of donated food are the World Food Program and USAID. The World Food Program currently provides pulses (legumes), corn, corn–soy blends, and cooking oil for up to 30 000 recipients and recently committed to supporting up to 1500 orphans and vulnerable children through AMPATH. USAID provides vitamin-enriched corn–soy blends for an additional 2000 recipients.

AMPATH purchases up to 3000 eggs per day from a network of chicken houses managed by its own patients. Packets of fermented milk are purchased from a local dairy farm. Fermented milk is preferred because it has a shelf life of approximately 10 days in the absence of refrigeration.

The supply of food now available from all these sources provides a culturally acceptable food basket consisting of fresh vegetables, fruit, eggs, milk products, an occasional chicken, corn, pulses, corn–soy blends, and cooking oil.

Food Distribution and Cost

The daily balance of supply and demand within the AMPATH service area must be supported by a delivery system capable of getting the right food at the right time to the right location for individual patients who live throughout much of western Kenya in an area in excess of 30 000 square kilometers. In response to this challenge, industrial engineers from Purdue University joined AMPATH to create a computerized nutrition information system.

Each day, the food prescription for each patient is entered in the nutrition information system along with an estimate of the total supply of food available. The nutrition information system then creates daily work logs detailing the amount, type, and location of food that needs to be moved. In addition, the nutrition information system lists individual patients scheduled to pick up food by day and site. Moving the food requires a transportation system and access to appropriate storage and packing centers. Distribution at the sites requires adequate space and distribution workers. Most distribution workers are specially trained AMPATH patients.

The cost of the food provided to beneficiaries includes the value of donations from the World Food Program and USAID, food purchased, and the total cost of production of food on the AMPATH high-production farms. In addition, the fixed costs of transport, nutritionist, distributors, and data management were totaled for the entire program. Once the program reached its target of 30 000 beneficiaries, this combination of food and fixed costs resulted in a cost per patient of US $0.27 per day.

Transition to Food Security

The designers of the AMPATH nutrition system anticipated that 6 months of food support, coupled with restoration of the immune system through antiretroviral therapy, would enable many patients to return to an adequate level of food security. Table 2 shows the number of beneficiaries successfully discontinued from food support in 2007. When it appears that additional nutrition support will be needed beyond 6 months, the patient is evaluated by an AMPATH social worker. If the social worker feels that continued food support is warranted, food will be continued while the patient is referred to another important arm of AMPATH, the Family Preservation Initiative.

This initiative provides an array of programs aimed at enhancing income security for AMPATH patients. For urban patients, this may take the form of microenterprise training with or without the assistance of microfinancing. For rural patients, it often involves linkage with AMPATH agriculture extension workers for consideration of improved farming techniques, planting new crops, or participation in cooperatives with other rural patients to grow high-value produce. The agriculture arm of the initiative is extending its services to all AMPATH sites, offering food and income security rather than dependency for thousands of AMPATH patients and their dependents.

DISCUSSION

Early in the history of the AMPATH program, food insecurity was identified as a pervasive and pernicious companion of HIV-infected patients in western Kenya. Patients who had walked miles to present themselves to AMPATH sites for evaluation and were offered antiretroviral therapy were known to decline therapy and walk back home when they learned that no food was available to allay their hunger. In spite of the challenges of scaling up an expensive and complex nutritional support system, AMPATH proceeded on the assumption that food is necessary for food-insecure patients and their dependents if antiretroviral therapy is to be of any benefit.

Having made the commitment to feed all food-insecure patients and their dependents, AMPATH fully understood the gap between goals and practice in sub-Saharan Africa. Even with adequate funding in hand, scaling up robust antiretroviral therapy of large populations proved to be a formidable challenge. Many of the same barriers to rapid scale up of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa are equally capable of frustrating the best-intended nutrition program. In this report, however, we clearly document that the demand for food by individual patients and their dependents can be determined and, most importantly, that demand can be met by a combination of food production, food donations, and an effective food distribution infrastructure. Our experience suggests that the addition of food to combination antiretroviral therapy has a synergistic clinical and immunological benefit; proving that benefit will be an important next step.

Challenges

Food support is an expensive addition to HIV care, and currently there are no funding sources that explicitly target food security for HIV-infected patients and their dependents. Beyond the costs of growing food, there are additional costs in managing large food donations. Significant investments were necessary for computer support systems, physical facilities, vehicles, and dedicated program management and food distribution staff. AMPATH has been able to support its nutrition program with a combination of funding sources. The US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief was the first to provide partial support of AMPATH's effort to establish a pilot model of nutrition support as a component of comprehensive HIV treatment. The World Food Program joined with AMPATH in a commitment to provide its basic food basket for up to 30 000 food-insecure patients and their dependents. USAID followed by contributing its corn–soy blend for an additional 2000 persons.

Remarkably, all of the land for continuously irrigated high-production farms used by AMPATH has been made available without cost. The initial farm used land made available by a nearby high school. Subsequently, land was provided at no cost to AMPATH by churches, the Ministry of Health, the Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital, Moi University, and local nongovernmental organizations. In addition, philanthropic donations have added critical funding every step of the way.

An immediate concern that arises when food support is provided to poor populations is the prospect of long-term dependency. It is unrealistic to think that one can feed patients until they have regained their health and then expect all of them to return to their previous means of securing food for themselves and their dependents. In our experience, some of the patients on antiretroviral therapy are able to return directly to self-sufficiency; for others, however, food security remains elusive even when their clinical and immune status has returned to normal. Too many jobs have been lost, too many spouses have died, and too many assets have been eroded for many patients who were food insecure even before HIV entered their lives. AMPATH will rely on the increasing strength of its social services program and the expanding capability of the Family Preservation Initiative to assist with those families for whom food security seems like an unattainable goal. Fortunately, additional funds now available will support a more rapid scale up of the Family Preservation Initiative in the years ahead. It is too early to determine the true proportion of patients capable of returning to food security until AMPATH gains more experience with the expanded initiative programs now being made available at all sites.

Successes

The fact that almost 2000 beneficiaries have been able to come off—and stay off—of food support since January 2007 is encouraging. The simultaneous rapid scale up of AMPATH's clinical services and nutritional support program means that most beneficiaries began receiving food support early in 2007 and, therefore, have not reached the time for discontinuation as of the time of writing. As the Family Preservation Initiative continues to expand and make its services available to additional AMPATH sites, we expect most patients to eventually become income—and hence food—secure.

It is unlikely that any program in sub-Saharan Africa can fully eliminate food insecurity and dependency in all patients. However, a successful program blending food support with economic development will probably avoid adding to the ranks of the food dependent and, we hope, can reduce the number destined to need food support indefinitely.9 Other successes include the extensive infrastructure developed for the nutrition and food programs, the total number of beneficiaries, the fact that food is provided to the family and not just the individual patient, and the linking of the food program with agricultural or business training through the Family Preservation Initiative.

Sustainability

Sustainability of food support on a scale now operational in AMPATH remains an additional concern. Every facet of the AMPATH nutrition program is vulnerable. Funds supporting the high production farms are from private donations and the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. Continuing donations from the World Food Program compete with endless pressure on an organization constantly facing some of this world's most daunting challenges. And the infrastructure and staff so essential to the distribution of food depend on a patchwork of contributions from many supporters of AMPATH. It is difficult to envision the sustainability of the AMPATH nutrition program or replication to other programs unless new commitments from the national government and the international donor community emerge. These commitments will need to support food security with the same vigor as those currently targeting universal access to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa.

Conclusions

At the time of writing, every food-insecure patient within AMPATH, and every child within that patient's family, has access to food. If nothing else, AMPATH has demonstrated that providing food security to food-insecure families can be done.

AMPATH proceeded with food support for its patients with the full conviction that impoverished HIV-infected patients and their dependents who are hungry require food as an integral component of care. Although improved monitoring and evaluation of the effectiveness of this program are required, further delay in replicating elsewhere the food security programs that AMPATH has implemented means that hundreds of thousands of patients and their dependents will remain hungry in sub-Saharan Africa and in other resource-constrained settings. Having demonstrated that food security can be provided, AMPATH's task now is to find the most cost-effective delivery systems, better understand the path toward sustainability, and welcome the efforts of those interventions that can prevent food insecurity in the first place.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a grant to the USAID–AMPATH Partnership from the United States Agency for International Development as part of the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (grant 623 - A-00 - 08 - 00003 - 00).

We thank the many nutritionists who devote their time and energy toward helping patients maintain or recover their food security, and Johnson Kimeu and Max Riana, who ensure that accurate and timely records are maintained. We also thank the World Food Program, the Moore Foundation, and the many individual donors who have made this work possible.

References

- 1.Kadiyala S, Gillespie S. Rethinking food aid to fight AIDS. Food Nutr Bull 2004;25(3):271–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anabwani G, Navario P. Nutrition and HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: an overview. Nutrition 2005;21(1):96–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wanke C. Nutrition and HIV in the international setting. Nutr Clin Care 2005;8(1):44–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chopra M, Darnton-Hill I. Responding to the crisis in sub-Saharan Africa: the role of nutrition. Public Health Nutr 2006;9(5):544–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Au JT, Kayitenkore K, Shutes E, et al. Access to adequate nutrition is a major potential obstacle to antiretroviral adherence among HIV-infected individuals in Rwanda. AIDS 2006;20(16):2116–2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mamlin J, Kimaiyo S, Nyandiko W, Tierney W, Einterz R. Academic Institutions Linking Access to Treatment and Prevention: Case Study. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Einterz R, Kimaiyo S, Mengech H, et al. Responding to the HIV pandemic: the power of an academic medical partnership. Acad Med 2007;82:812–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coates J, Swindale A, Bilinsky P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide. Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marston B, De Cock K. Multivitamins, nutrition, and antiretroviral therapy for HIV disease in Africa. N Engl J Med 2004;351:78–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]