Abstract

In the Drosophila nervous system, the glial cells missing gene (gcm) is transiently expressed in glial precursors to switch their fate from the neuronal default to glia. It encodes a novel 504-amino acid protein with a nuclear localization signal. We report here that the GCM protein is a novel DNA-binding protein and that its DNA-binding activity is localized in the N-terminal 181 amino acids. It binds with high specificity to the nucleotide sequence, (A/G)CCCGCAT, which is a novel sequence among known targets of DNA-binding proteins. Eleven such GCM-binding sequences are found in the 5′ upstream region of the repo gene, whose expression in early glial cells is dependent on gcm. This suggests that the GCM protein is a transcriptional regulator directly controlling repo. We have also identified homologous genes from human and mouse whose products share a highly conserved N-terminal region with Drosophila GCM. At least one of these was shown to have DNA-binding activity similar to that of GCM. By comparing the deduced amino acid sequences of these gene products, we were able to define the “gcm motif,” an evolutionarily conserved motif with DNA-binding activity. By PCR amplification, we obtained evidence for the existence of additional gcm-motif genes in mouse as well as in Drosophila. The gcm-motif, therefore, forms a family of novel DNA-binding proteins, and may function in various aspects of cell fate determination.

Keywords: DNA-binding activity, transcriptional regulator

In the development of the nervous system, two different types of cells, neurons, and glia, are often derived from common precursors. We identified a Drosophila gene, glial cells missing (gcm), which was shown to function in glial vs. neuronal cell fate determination (1–6). Cells in the Drosophila central nervous system arise from about 30 neuroblasts in each hemisegment (7). One of them is called a glioblast, since it only generates longitudinal glial cells (8). Other neuroblasts mostly produce neurons, but some of them generate both neurons and glial cells (9, 10). It was shown that the cells expressing the gcm gene in the Drosophila nervous system generate or become glial cells (1, 2, 4).

The gcm gene was identified by screening for mutations affecting the formation of the nervous system (1–3). It was shown that the longitudinal tracts were disrupted in the mutant central nervous system and that a neuronal disorganization was also observed in the peripheral nervous system. By examining the expression of glial markers in gcm mutants, it was shown that the glial cells were entirely absent from an early stage of neurogenesis on (1, 2, 4). This absence is due to transformation of the presumptive glial cells into neurons both in the central and peripheral nervous systems (1, 2, 4). The opposite is observed when gcm is ectopically expressed in neuroblasts; presumptive neurons are transformed into glial cells (1, 2). Therefore, gcm expression in neuroblasts or in immature glial cells ensures that cells differentiate into glia instead of neurons.

The gcm gene encodes a 504-amino acid protein and contains no previously characterized motifs, other than a nuclear localization signal (1, 2). The simplest model for GCM function is to assume that GCM itself binds to DNA and directly regulates the expression of its target genes. In this paper we describe the DNA-binding properties of GCM. We show that the N-terminal region binds to DNA in a sequence specific manner. Eleven GCM-binding sites are found in the 5′ putative regulatory region of the repo gene (11–13), whose expression is dependent on gcm (1, 2, 4). Finally, the isolation of human and mouse genes is described whose products have a conserved N-terminal region that corresponds to the DNA-binding domain of GCM. From the conserved amino-acid residues, we define the gcm-motif as a novel amino acid sequence with DNA-binding activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Production of Fusion Proteins.

Fusion proteins were prepared using a protein fusion and purification system (New England Biolabs). To construct plasmids, PCR was performed with pfu DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka), and the amplified fragments containing parts of the gcm gene were inserted in-frame into the pMAL-c2 vector. Fusion proteins and MBP-lacZα, which was used as a control for gel-shift assays, were induced in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)pLysS. They were then sonicated, extracted, and affinity-purified using amylose resin. Full-length GCM fusion protein was also produced, but because of the low yields we were unable to use this protein.

Screening of the Genomic Library and Preparation of Probes for Gel-Shift Assays.

A Drosophila genomic library in lambda-DASH (Stratagene) was screened using the repo cDNA (11) as a probe. Isolated genomic clones were subcloned into pBluescript SK-II (Stratagene). Nucleotide sequencing was carried out with the BcaBEST DNA sequencing kit (Takara Shuzo, Kyoto). A region of ≈7 kb upstream of the repo gene was digested with restriction enzymes, AluI, AvaI, EcoRV, FokI, HhaI, HinfI, NdeI, NspI, Sau3aI, and TthHB8I, yielding fragments of between 60–460 bp that were resubcloned into the vector. When used as probes for gel-shift assays, the inserts were excised and end-labeled.

Gel-Shift Assays.

Gel-shift assays were performed as described elsewhere, but with some modifications (14, 15). Most binding reactions were done in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.9), 50 mM KCl, 1 mg/ml BSA, 0.5 mM ZnCl2, 150 ng/ml poly(dI-dC), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 8% glycerol, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Some reactions were performed at different concentrations of KCl; 75, 100, 125, and 150 mM. Approximately 200 ng of each protein was incubated with 5000 cpm of 32P-labeled DNA at 25°C for 30 min. The reaction mixtures were loaded on a 0.5× TBE (45 mM Tris·borate/1 mM EDTA), 4% polyacrylamide gel containing 5% glycerol, and run at 4°C.

Analysis of the Binding Consensus Sequence.

The binding consensus sequence was determined as described (16–18). Binding reactions were performed as above using the fusion protein N243 and oligonucleotides with a random 15-bp sequence inserted between M13-reverse and M13-M4 sequences. The sequences of M13-reverse and M13-M4 are TGTGTGGAATTGTGAGCGGA and GGTTTTCCCAGTCACGACG, respectively. Oligonucleotides that bound to the protein were eluted from the polyacrylamide gel, amplified by PCR with M13-reverse and M13-M4 primers, and then used in the next cycle. After the third selection cycle the oligonucleotides were subcloned into the pCR II vector (Invitrogen) and sequenced.

Competition Assays.

Binding reaction conditions were the same as those of the gel-shift assays described above. Fusion proteins were preincubated for 20 min with unlabeled competitor DNA before adding labeled DNA. The sequences of competitors are as follows: competitor a, M13-reverse-CCTACCCGCATTACG-M13-M4; competitor b, M13-reverse-TATACTAATTTGTTA-M13-M4.

Isolation of Human and Mouse Genes.

The partial clone of hGCMa was identified in the expression sequence tag (EST) data base (Washington University, St. Louis, and Merck). 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) was performed to isolate full-length hGCMa with human placenta 5′ RACE-ready cDNA (CLONTECH 7301-1). The sequences of primers that were used in the first and the second PCR cycles are as follows; CTTCTTGCCTCAGCTTCTAACTTGG (the first PCR cycle) and AATATAAAGCGTCCGTCGTGCCTCC (the second PCR cycle). To confirm the sequence, we also performed 3′ RACE using Human Placenta Marathon-Ready cDNA (CLONTECH, CL7411-1). The primer sequences are CTGGGTGTGGTGGTGTGCGGCCGCGACTGTCTCGC (the first PCR cycle) and GACTGTCTCGCAGAGGAGGGGCGCAAGATCTACCT (the second PCR cycle). The obtained sequence contained a frame-shift compared with that of the EST clone. This may be due to the cloning artifact of the EST clone. For isolation of mouse genes, reverse transcriptase–PCR was performed with mouse adult brain poly(A)+ RNA (CLONTECH CL6616-1). For reverse transcriptase reactions, we used the GIBCO/BRL preamplification system (18089-011). PCR cycles were done with primer pairs, A and C, or B and C. The sequences of the primers are according to the corresponding sequences of hGCMa. (Primer A, TGGGCCATGCGCAATACCAACAACCACAAC; primer B, ATCCTCAAGAAGTCCTGCCTGGGTGTG; primer C, GGCCTTGTCACAGATGGCAGGTCTCAG.) Full-length mGCMa was isolated from mouse E16 placenta poly(A)+ RNA using Marathon cDNA Amplification kit (CLONTECH, CLK1802-1). The primer sequences are TTGTCACAGATGGCAGGTCTCAGGTAAATCTTGCG (the first PCR cycle of 5′ RACE), AGGTAAATCTTGCGGCCTTCCTCTGTGGAGCAGTC (the second PCR cycle of 5′ RACE), TGGGCCATGCGCAATACCAACAACCACAACTCCCG (the first PCR cycle of 3′ RACE) and CTGGGGGTAGTGGTGTGCAGCAGGGACTGCTCCAC (the second PCR cycle of 3′ RACE). Full-length mGCMb was obtained by 5′ RACE and 3′ RACE, using mouse brain Marathon-ready cDNA (CLONTECH 7450-1). We used primers A and B for 3′ RACE. We used primer C for the first PCR cycle of 5′ RACE. The sequence of primer that was used in the second PCR cycle is CTGCAGGTGCGAGCCATCCTTCAGGG. dGCM2 was isolated by PCR from Drosophila genomic DNA, using degenerate A and C primers. [Degenerate A primer, TGGGCNATG(CGN/AG(A/G))AA(T/C)AC; degenerate C primer, GC(T/C)TT(A/G)TC(A/G)CA(A/G/T)ATNGC.] Ex-Taq polymerase (Takara Shuzo) was used in all PCR reactions.

RESULTS

The N-Terminal Region of GCM Protein Binds to DNA.

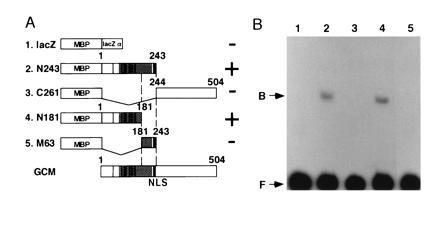

To examine the DNA-binding properties of GCM, we carried out gel-shift assays using fusion proteins containing truncated forms of GCM produced in bacteria (Fig. 1A). DNA fragment A derived from the 5′ upstream region of the repo gene shown in Fig. 3A was used as a probe. The homeobox gene repo is expressed in virtually all glial cells from an early stage onwards (11–13), and this expression is strongly dependent on gcm (1, 2). Hence, repo is a good candidate gene to be a direct target of GCM. Two of the fusion proteins, N243 and N181, bound to the probe in gel-shift assays (Fig. 1B). This indicates that the N-terminal 181-amino acid stretch of GCM has DNA-binding activity. Since this amino acid sequence displays no homology to any known protein, it comprises a novel DNA-binding domain.

Figure 1.

The N-terminal region of GCM binds to DNA. (A) GCM fusion protein constructs tested for DNA-binding activity. Lanes 2–5 show a series of truncated GCM-maltose binding protein (MBP) fusions. The bottom part of the figure shows a schematic drawing of intact GCM. A nuclear localization signal (NLS) and the region rich in basic residues is represented by solid and hatched boxes, respectively. Vertical bars indicate the nine cysteine residues. The numbers above each construct indicate corresponding residues of GCM. MBP-lacZα was used as a control. DNA-binding activity is shown in the right column. (B) Gel-shift assays with GCM fusion proteins. A 100-bp genomic fragment A of repo (see Fig. 3A) was electrophoresed with one of the GCM fusion proteins. Lane numbers correspond to those shown in the left column of A. Two constructs, N243 and N181, showed DNA-binding activity, while C261 and M63 did not. DNA-protein complexes (B) and free probes (F) are indicated.

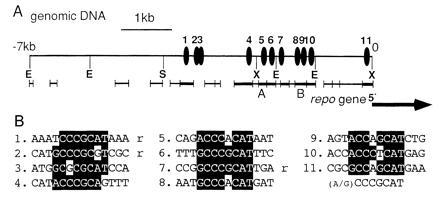

Figure 3.

Eleven GCM-binding sites are present in the region upstream of the repo gene. (A) The GCM-binding sites. Positions of the GCM-binding sequence are indicated by solid ellipses (1–11). The consensus binding sequences are clustered in the proximal upstream 4 kb, whereas none were found between the −4 kb to −7-kb region. The initiation site and the orientation of the repo gene are indicated by a large arrow, according to Halter et al. (12). Xiong et al. (11) reported that one more exon is located at −4 kb in this figure, but we could not find such sequences within the −7-kb region. Thick bars and thin bars respectively show fragments that bound or did not bind to GCM in gel-shift assays. A and B indicate the probes used in the gel-shift assays shown in Figs. 1 and 2. E, EcoRI; S, SalI; and X, XhoI. (B) Alignment of the GCM-binding sequences in the upstream of repo. The numbers correspond to those in A. Nucleotides identical to the consensus sequence are highlighted. Three sequences that are in opposite orientation to the others are indicated by “r.”

GCM Binds Specifically to an Octamer Sequence.

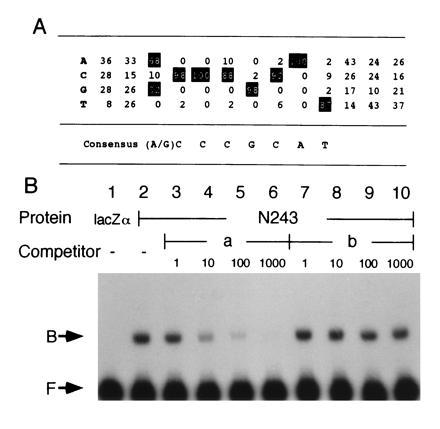

We then searched for the consensus nucleotide sequence recognized by GCM. We performed gel-shift assays using oligonucleotides containing a 15-bp random sequence and the fusion protein, N243. The oligonucleotides that bound to N243 were eluted from the gel and amplified by PCR. These binding-and-PCR cycles were repeated three times. Forty-eight clones of the amplified oligonucleotides were sequenced. Among them, 34 clones contained the octamer sequence, 5′-(A/G)CCCGCAT-3′, and 11 clones had sequences that contained only 1 nucleotide mismatch in this octamer sequence. The remaining three clones had similar sequences with two or three mismatches. A summary of the sequence alignment is shown in Fig. 2A. This result strongly suggests that GCM protein specifically recognizes this octamer sequence.

Figure 2.

GCM specifically binds to an octamer sequence. (A) The GCM consensus-binding sequence. Forty-eight of the clones selected from a pool of random oligonucleotides on the basis of affinity to N243 were sequenced and aligned. Percentage values are the frequency of each base at each position. The most frequently present bases are highlighted and the derived consensus sequence is shown below. (B) Competition assays. Assays were performed using a 200-bp labeled DNA fragment B (see Fig. 3A) with protein N243 in lanes 2–10, and MBP-lacZα in lane 1 as a control. Unlabeled competitors were added to the reaction mixture in equal concentration to the labeled probe or in 10-, 100-, or 1000-fold molar excess. Absence of the competitor is indicated by minus signs. Addition of competitor a, which contains the consensus sequence, abolishes DNA-protein complex. Addition of competitor b, which lacks the consensus sequence, did not show competitive activity. Free probes (F) and DNA-protein complexes (B) are indicated.

The binding specificity was further examined in competition assays (Fig. 2B). The assays were performed using N243 and DNA fragment B derived from the repo upstream region that contains two of the octamer sequences shown in Fig. 3A. Addition of one of the 34 clones that contained the octamer sequence as a nonlabeled competitor (competitor a) resulted in a marked reduction in DNA-protein complex formation, while another oligonucleotide that did not contain the sequence (competitor b) showed no competitive activity (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that GCM protein binds to the nonpalindromic octamer, (A/G)CCCGCAT, with high specificity. This sequence is a novel sequence among other known targets of DNA-binding proteins.

To examine the DNA-binding affinity, we performed gel-shift assays at various ionic concentrations; 50, 75, 100, 125, and 150 mM KCl. We confirmed that the fusion protein N181 bound with the same efficiency to the DNA fragment A shown in Fig. 3A even at these high ionic concentrations (data not shown). This suggests that GCM has a high affinity for this DNA sequence under physiological conditions.

GCM-Binding Sites Are Present in the Immediate 5′ Upstream Region of the repo Gene.

On the assumption that repo is a direct target of GCM, we searched the region upstream of the repo gene for GCM-binding sites. First, we cloned the genomic region and performed gel-shift assays using 21 nonoverlapping DNA fragments, ranging in size from 60 to 460 bp and spanning the 7-kb upstream region (Fig. 3A). We found that the fusion protein N243 bound to eight of these fragments (Fig. 3A). The fusion protein C261 did not bind to any of the fragments. This result is consistent with the previous data shown in Fig. 1B. These binding assays suggest that at least eight GCM-binding sites exist in the 7-kb region.

Second, we determined the DNA sequence of the 7-kb upstream region and found that 11 GCM-binding sequences exist within the 4-kb upstream region, whereas no binding sequence was present in the −4-kb to −7-kb region (Fig. 3). Sequences that matched at least seven of the eight nucleotides of the consensus sequence on either strand were counted as GCM-binding sites. Three of the 11 consensus sequences, sites 1, 2, and 7, were in the opposite orientation to the others (Fig. 3B). The eight DNA fragments that bound to N243 in the gel-shift assays contained one or two GCM-binding sequence(s), whereas the fragments that did not bind lacked the sequence. We did not perform binding assays with a DNA fragment spanning sites 2 and 3 (Fig. 3A). It is not absolutely clear whether GCM binds to these two sites, since these sequences have a mismatch at the seventh and third nucleotide, respectively (Fig. 3B), whereas no mismatch was recovered in the experiment shown in Fig. 2A.

The frequency of the appearance of an octamer nucleotide sequence in completely random DNA on both strands is once in every 0.7 kb, if one nucleotide mismatch is allowed. The frequency of 11 binding sites within the 4-kb region adjacent to the repo gene is far beyond the expected value. The clustered 11 GCM-binding sequences suggests that GCM regulates repo expression by binding directly to its upstream region, i.e., GCM is a transcriptional regulator.

A Novel DNA-Binding Motif, gcm-Motif, Is Conserved in Mammals.

To determine if the DNA-binding domain is conserved throughout evolution, we searched for mammalian homologs of the GCM motif. We identified a human gene (hGCMa) in the EST data base that encoded polypeptide with significant amino acid similarity to GCM. This clone starts with the amino acid residue 92 through the C-terminal end. We performed 5′ RACE and 3′ RACE to determine the entire coding sequence of hGCMa. Then, using the conserved region between GCM and hGCMa, we isolated mouse genes (mGCMa and mGCMb) by reverse transcriptase–PCR and RACE. We obtained mGCMa from mouse placenta poly(A)+ RNA and mGCMb from adult brain poly(A)+ RNA.

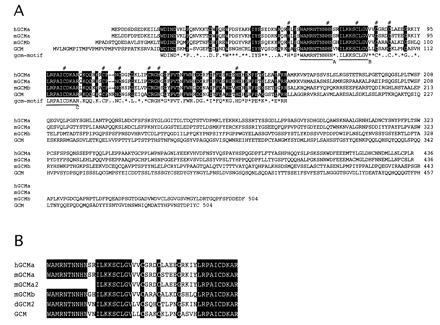

Comparison of the deduced protein sequences of hGCMa, mGCMa, mGCMb and GCM revealed strong conservation of the highly basic N-terminal one-third. From these comparisons we could unambiguously define an evolutionarily conserved motif that we named the “gcm-motif” (Fig. 4A). This motif corresponds to the region containing the DNA-binding activity described above. The gcm-motif spans about 150 amino acid residues starting from WDIND and ending with EXRR. In GCM it corresponds to the region between residues 34–186. The alignment reveals characteristic features, such as 3 absolutely conserved stretches of 9 or 10 amino acid residues, and seven conserved cysteine and four conserved histidine residues (Fig. 4A). In contrast to the highly conserved gcm-motif at the N-terminal regions, C-terminal regions of the genes mostly have no similarity to each other nor to any known proteins. An exception is between hGCMa and mGCMa that share similar amino acid sequences also in their C-terminal regions.

Figure 4.

Comparison of Drosophila and mammalian gcm-motif genes. (A) Sequence alignment of human GCMa (hGCMa), mouse GCMa (mGCMa), mouse GCMb (mGCMb), and Drosophila GCM (GCM). Amino acid residues shared by these four gene products are highlighted and the gcm-motif is shown below. Similar residues are shown by asterisks. The conserved seven cysteine and four histidine residues are indicated by #. Three absolutely conserved stretches of 9 or 10 amino acids are underlined (A–C). Gaps are indicated by dashes. (B) Sequence alignment of PCR products. mGCMa, a2, and b are amplified by RT-PCR, using mouse adult head poly(A)+ RNA as a template. dGCM2 is a product of PCR using Drosophila genomic DNA as template. Those PCR products have about 70% nucleotide identity to GCM.

We also performed gel-shift assays with the N-terminal 171 amino acid region of hGCMa, which was produced in bacteria as described in Materials and Methods. This region spans the gcm-motif but is slightly longer. It also could bind to DNA fragment A derived from the repo upstream region shown in Fig. 3A. Competitor a (Fig. 2B), which contained the octamer sequence, successfully competed with hGCMa for binding to the repo upstream region (data not shown). On the other hand, competitor b shown in Fig. 2B that did not have the octamer sequence did not affect formation of the protein–DNA complex. These results indicate that the N-terminal region of hGCMa has a specific DNA-binding activity similar, if not identical, to that of GCM. Thus, the amino acid sequence common to both GCM and hGCMa, that is the gcm-motif, contains the sequence specific DNA-binding activity.

To search for more genes having the gcm-motif, we carried out reverse transcription–PCR and PCR with mouse adult brain poly(A)+ RNA and Drosophila genomic DNA, respectively. We obtained fragments of other gcm-motif genes, one mouse gene (mGCMa2), and one Drosophila gene (dGCM2) (Fig. 4B). This strongly suggests that the gcm-motif is evolutionarily conserved and forms a family of novel DNA-binding proteins.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here show that Drosophila GCM is a novel DNA-binding protein. Its binding is highly specific for an octamer sequence, (A/G)CCCGCAT. This was shown by PCR amplification of oligonucleotides containing 15 bp random sequences selected by the affinity to GCM in the gel-shift assays. We found that most of the 48 clones, which were selected on the basis of GCM affinity, contained the octamer sequence. At each position of the eight nucleotide sequence in the 48 clones, the mismatch frequencies ranged from 0–13% (Fig. 2A). Therefore, GCM shows high specificity for this octamer sequence.

Since repo gene expression in early glial cells is dependent on gcm (1, 2), we suspected that the repo regulatory region had GCM-binding sites. By cloning and sequencing the genomic region flanking the repo gene and carrying out gel-shift assays, we found 11 GCM-binding sequences in the immediate upstream region of the repo gene (Fig. 3A). This finding strongly suggests that GCM functions as a transcriptional regulator and that repo is a direct target of GCM. Here, we counted those octamer sequences as GCM-binding sites if they had at least seven nucleotides identical to the consensus sequence on either of the strands. The rationale for this designation is that among the 21 fragments derived from the repo upstream region, the eight that showed distinct binding by GCM contained one or two of the binding sequences. On the other hand, 13 DNA fragments that did not bind to GCM had no such sequence (Fig. 3A). In addition, fragment A, which was used successfully in the gel-shift assay at 150 mM KCl, the physiological ionic concentration, has one mismatch to the consensus sequence (Fig. 3). The stable binding of octamer sequences with one mismatch under physiological ionic conditions suggests that GCM binds to the consensus sequences with high affinity in vivo.

Among the 11 sites that were found in the repo upstream region, the cluster of sites 4–10 is very distinct. In addition, they have the same orientation, except for site 7 (Fig. 3B). Since the GCM-binding sequence is not palindromic, the orientation of the binding sites may be important for GCM function. Therefore, the clustering of six sites, sites 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, and 10, within the 1.4-kb region with the same orientation might be responsible for the regulation of repo expression.

The results above suggests that the repo gene is a direct target of GCM. However, there must be other target genes as well, since the strongest repo alleles show less extensive defects in the embryonic nervous system (11–13) than gcm mutants. Hence, the isolation of other GCM-target genes is required to clarify how glial vs. neuronal cell fate is controlled.

We searched for gcm-like genes in vertebrates and have so far succeeded in isolating human and mouse genes, hGCMa, mGCMa, and mGCMb, that are homologous to GCM. The N-terminal regions of these genes are highly conserved and we named these conserved amino acid sequences the gcm-motif. This motif corresponds to the DNA-binding region, as demonstrated by gel-shift assays (Fig. 1). The gcm-motif contains many conserved basic amino acid residues, seven cysteine residues, and four histidine residues (Fig. 4A). These residues may have important roles such as in the interaction with DNA, in the coordination with a metal ion or in the conformation of the motif. Analyses of the three-dimensional structure should lead to a better definition of the functions of these residues.

The gcm-motif is sufficient for DNA-binding activity, but it is not clear whether the entire motif is necessary. The gcm-motif may also serve other functions, such as a transcriptional regulatory activity. As for the C-terminal regions, their functions remain unknown. We are now examining the function of each region, including the gcm-motif and the diverged C-terminal region, by making transgenic flies that express various truncated forms of GCM.

We are currently investigating the roles of the gcm-motif genes in the mouse. Preliminary experiments have shown that mGCMb is expressed in the embryonic nervous system (unpublished data, in collaboration with K. Ikenaka, National Institute for Physiological Sciences). This gene may have developmental functions similar to those of GCM. The gcm-motif genes are most likely to be transcriptional factors and may potentially function as switch molecules in a variety of differentiation processes. From this point of view, we can immediately draw a parallel between gcm-motif proteins and homeodomain proteins that play important roles in the various processes of pattern formation, both in Drosophila and in vertebrates (19).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Y. Hiromi, F. Matsuzaki, C. Hama, K. Ito, H. Nakagoshi, S. Goto, and N. Yabe for thoughtful discussions. We would like to acknowledge Drs. C. Montell and H. Okano who provided us with repo cDNA and Dr. H. Nakauchi for providing us with mouse E16 placenta poly(A)+ RNA. We also acknowledge Washington University and Merck EST project for providing us with the partial clone of hGCMa. We acknowledge Dr. K. Mogami for critically reading the manuscript, and Ms. Y. Fujioka, M. Seki, M. Funatake, and Y. Mizuguchi for their technical assistance. We thank all the members of our laboratory for helpful input and discussion. This work was supported by a project grant to Y.H. from the Human Frontier Science Program Organization and by the Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology Grants from Japan Science and Technology Corporation. T.H. is supported by Grants from the Science and Technology Agency. Y.A. is a Research Fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: gcm, glial cells missing; RACE, rapid amplification of cDNA ends; EST, expression sequence tag.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank data base (accession nos. D88611–D88613D88611D88612D88613).

References

- 1.Hosoya T, Takizawa K, Nitta K, Hotta Y. Cell. 1995;82:1025–1036. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90281-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones B W, Fetter R D, Tear G, Goodman C S. Cell. 1995;82:1013–1023. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kania A, Salzberg A, Bhat M, D’Evelyn D, He Y, Kiss I, Bellen H J. Genetics. 1995;139:1663–1678. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.4.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincent S, Vonesch J-L, Giangrande A. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1996;122:131–139. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfrieger F W, Barres B A. Cell. 1995;83:671–674. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson D J. Neuron. 1995;15:1219–1222. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodman C S, Doe C Q. In: The Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Bate M, Martinez-Arias A, editors. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1993. pp. 1131–1206. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobs J R, Hiromi Y, Patel N H, Goodman C S. Neuron. 1989;2:1625–1631. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Udolph G, Prokop A, Bossing T, Technau G M. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1993;118:765–775. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.3.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higashijima S, Shishido E, Matsuzaki M, Saigo K. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1996;122:527–536. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.2.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiong W-C, Okano H, Patel N H, Blendy J A, Montell C. Genes Dev. 1994;8:981–994. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.8.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halter D A, Urban J, Rickert C, Ner S S, Ito K, Travers A A, Technau G M. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1995;121:317–332. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell G, Göring H, Lin T, Spana E, Andersson S, Doe C Q, Tomlinson A. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1994;120:2957–2966. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.10.2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ip Y T, Kraut R, Levine M, Rushlow C A. Cell. 1991;64:439–446. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90651-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cabrera C V, Alonso M C. EMBO J. 1991;10:2965–2973. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blackwell T K, Weintraub H. Science. 1990;250:1104–1110. doi: 10.1126/science.2174572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun X-H, Baltimore D. Cell. 1991;64:459–470. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90653-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gogos J A, Hsu T, Bolton J, Kafatos F C. Science. 1992;257:1951–1955. doi: 10.1126/science.1290524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGinnis W, Krumlauf R. Cell. 1992;68:283–302. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90471-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]