Abstract

DNA polymerase η (Polη) catalyzes the efficient and accurate synthesis of DNA opposite cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers, and inactivation of Polη in humans causes the cancer-prone syndrome, the variant form of xeroderma pigmentosum. Pre-steady-state kinetic studies of yeast Polη have indicated that the low level of fidelity of this enzyme results from a poorly discriminating induced-fit mechanism. Here we examine the mechanistic basis of the low level of fidelity of human Polη. Because the human and yeast enzymes behave similarly under steady-state conditions, we expected these enzymes to utilize similar mechanisms of nucleotide incorporation. Surprisingly, however, we find that human Polη differs from the yeast enzyme in several important respects. The human enzyme has a 50-fold-faster rate of nucleotide incorporation than the yeast enzyme but binds the nucleotide with an approximately 50-fold-lower level of affinity. This lower level of binding affinity might provide a means of regulation whereby the human enzyme remains relatively inactive except when the cellular deoxynucleoside triphosphate concentrations are high, as may occur during DNA damage, thereby avoiding the mutagenic consequences arising from the inadvertent action of this enzyme during normal DNA replication.

DNA polymerase η (Polη) is unique among eukaryotic DNA polymerases in its proficient and accurate ability to replicate through UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (9, 11, 14, 22). Inactivation of Polη in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (10, 16, 27) as well as in humans (21, 25) results in increased UV-induced mutagenesis, and a lack of Polη in humans causes the variant form of xeroderma pigmentosum (8, 14), a syndrome characterized by an elevated incidence of sunlight-induced skin cancers. Thus, Polη acts to reduce the frequency of UV-induced mutagenesis and carcinogenesis.

Biochemical studies have shown that both yeast and human Polη replicate through a cis-syn thymine-thymine (TT) dimer efficiently and accurately by incorporating two As opposite the two Ts of the dimer (9, 11, 22). Polη can also efficiently replicate through other DNA lesions, such as 8-oxoguanine and O6-methylguanine (4, 5). We previously suggested (as determined on the basis of the proficient ability of Polη to replicate through distorting DNA lesions) that Polη possesses an active site that is remarkably tolerant of geometric distortions in the DNA, allowing it to incorporate nucleotides opposite DNA lesions (23). Support for this hypothesis came from steady-state kinetic studies, which showed that yeast and human Polη synthesize DNA with a low level of fidelity with error frequencies on the order of 10−2 to 10−3 (11, 23), and in an in vitro reaction, human Polη was found to synthesize DNA with a low level of fidelity (15).

While steady-state kinetics can provide an accurate measure of the fidelity of nucleotide incorporation, it provides little information about the mechanistic basis of fidelity. This is because in steady-state kinetics one observes only the slowest step of the nucleotide incorporation reaction, which for Polη and other DNA polymerases occurs after the chemical step of phosphodiester bond formation. Consequently, steady-state kinetics cannot determine the contributions to fidelity of crucial elementary steps such as nucleotide binding to the enzyme-DNA binary complex, conformational changes in the enzyme-DNA-nucleotide ternary complex, and the chemical step of phosphodiester bond formation, all of which precede the rate-determining step under steady-state conditions (1, 7, 12, 13, 17, 26).

To examine the mechanistic basis of the low level of fidelity of Polη, Washington et al. previously carried out a pre-steady-state kinetic analysis with yeast Polη. They found that relative to classical high-fidelity replicative DNA polymerases, which lack the ability to replicate through distorting DNA lesions, yeast Polη discriminates between the correct and incorrect nucleotide poorly at both the initial nucleotide binding and subsequent nucleotide incorporation steps (24). Washington et al. also showed that the rate-limiting step in the first turnover of nucleotide incorporation was substantially slower than in classical polymerases and presented evidence that this step was a conformational change in the ternary complex immediately preceding the chemical step of phosphodiester bond formation (24).

Here we have carried out a pre-steady-state kinetic analysis of human Polη to better understand the mechanistic basis of its low level of fidelity. Because the yeast and human enzymes behave so similarly under steady-state conditions, we expected the pre-steady-state mechanism of nucleotide discrimination by the human enzyme to be the same as that of the yeast enzyme. Quite unexpectedly, we found that the mechanisms of the yeast and human enzymes differ in several important respects. Relative to the yeast enzyme, the human enzyme has a faster intrinsic rate of nucleotide incorporation. In this respect, human Polη is more like a classical DNA polymerase than yeast Polη. However, relative to the yeast enzyme, the human enzyme has a substantially lower level of affinity for the incoming nucleotide. Consequently, unlike the yeast enzyme, the human enzyme could be more sensitive to changes in the cellular deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) concentrations, and that sensitivity may serve to keep this low-fidelity enzyme relatively inactive except when the cellular dNTP concentrations rise, as might occur upon DNA damage (2).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Purification of human Polη.

Full-length human Polη and truncated human Polη (1-475) were purified as glutathione-S-transferase fusion proteins from yeast strain BJ5464 carrying plasmids pR30.186 and pR30.233, respectively. The proteins were purified and the glutathione-S-transferase portion of the fusion protein was removed with PreScission protease (Amersham Pharmacia) as described previously (24). Protein concentrations were determined by using molar extinction coefficients of 70,731 M · cm−1 for full-length Polη and 54,318 M · cm−1 for Polη (1-475) measuring UV absorption at 280 nm. Protein concentrations were also determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay with bovine serum albumin as a standard. An active-site titration (see Results) showed that 83% of the total concentration of Polη (1-475) was active, and the concentration of enzyme used in all the experiments was corrected for the amount of active enzyme.

Nucleotides.

Ultrapure grade solutions of dATP and dCTP (0.1 M of the sodium salt [pH 7.0]) were obtained from USB and were stored at −70°C. Adenosine 5′ [γ-32P]triphosphate (6,000 Ci/mmol) was purchased from Amersham Pharmacia.

Oligodeoxynucleotide substrates.

The oligodeoxynucleotide used as a primer was a 25mer with the sequence 5′GCCTC GCAGC CGTCC AACCA ACTCA. The oligodeoxynucleotide used as a template was a 45mer with the sequence 5′GGACG GCATT GGATC GACCT TGAGT TGGTT GGACG GCTGC GAGGC. The primer strand (10 μM) was 5′ 32P end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and polynucleotide kinase (Boehringer Mannheim) for 45 min at 37°C. The labeled primer strand (2 μM) was annealed to the template strand (2.5 μM) in 50 mM TrisCl (pH 7.5)-100 mM NaCl at 90°C for 5 min and slowly cooled at room temperature over several hours.

Steady-state kinetics assays.

Full-length Polη or Polη (1-475) (1 nM) was incubated with the DNA substrate (200 nM) and various concentrations of either dATP, the correct nucleotide (0 to 10 μM), or dCTP, the incorrect nucleotide (0 to 500 μM), in 25 mM TrisCl (pH 7.5)-5 mM MgCl2-5 mM dithiothreitol-10% glycerol at room temperature for 5 or 10 min. Reactions were quenched with 10 volumes of formamide-loading buffer (90% deionized formamide, 10 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 1 mg of xylene cyanol/ml, 1 mg of bromophenol blue/ml), and products were separated on a 15% polyacrylamide sequencing gel. The intensities of the gel bands were quantitated using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). The mean and standard error values were determined from three independent experiments.

Pre-steady-state kinetics assays.

Experiments were carried out (using a Rapid Chemical Quench Flow instrument [KinTek]) in 25 mM TrisCl (pH 7.5)-5 mM MgCl2-5 mM dithiothreitol-10% glycerol at 18°C. Preincubated Polη (50 nM final concentration) and the DNA substrate (0 to 200 nM final concentration) were loaded into one sample loop (15 μl), and either dATP (0 to 500 μM) or dCTP (0 to 1,500 μM) was loaded into the other sample loop. Reactions were quenched with 0.3 M EDTA, and products were separated on a 15% polyacrylamide sequencing gel.

Data analysis.

For the steady-state experiments, the linear rate of nucleotide incorporation (v) was graphed as a function of [dNTP], and the kcat and Km parameters were obtained by fitting the data by nonlinear regression (using SigmaPlot 7.0 software) to the Michaelis-Menten equation:

|

(1) |

For the pre-steady-state experiments, the amount of product formed (P) was graphed as a function of time (t) and the data were fitted to the burst equation:

|

(2) |

where A is the amplitude of the burst phase, kobs is the rate constant of the burst phase, and v is the rate of the linear phase. The amplitudes of the burst phases (A) were graphed as a function of [DNA], and the data were fitted to the quadratic equation:

|

(3) |

where KD is the dissociation constant for the DNA and [Polη] is the concentration of active Polη. The rate constants of the burst phases (kobs) were graphed as a function of [dNTP], and the data were fitted to the hyperbolic equation:

|

(4) |

where kpol is the maximum rate constant of the burst phase and KD is the dissociation constant for the dNTP.

To ensure reproducibility of the data, two to four independent experiments were performed for each DNA and dNTP concentration; the amplitudes and rates obtained were in close agreement.

RESULTS

Comparison of full-length and truncated human Polη.

We initially purified two forms of human Polη: the full-length protein and Polη (1-475), a truncated version lacking 238 amino acid residues from the C terminus. Polη (1-475) is completely active, efficiently bypasses a TT dimer, and contains all the amino acid residues that comprise the corresponding palm, fingers, thumb, and PAD domains depicted in the high-resolution X-ray structure of yeast Polη (20). Since Polη (1-475) is expressed about 100-fold better than the full-length protein, we were able to purify this protein in amounts sufficient to carry out a detailed and systematic pre-steady-state kinetic study.

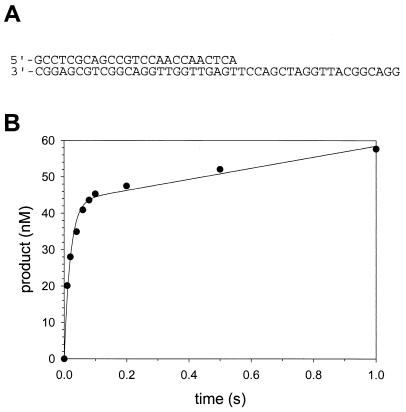

To ascertain whether the efficiency of nucleotide incorporation by Polη (1-475) was similar to that by the full-length protein, we compared the nucleotide incorporation activities of these proteins under steady-state conditions. Each form of Polη (1 nM) was incubated with the DNA substrate (200 nM) (Fig. 1A) and various concentrations of either the correct nucleotide dATP (0 to 10 μM) or the incorrect nucleotide dCTP (0 to 500 μM). The kcat values for the full-length and the truncated forms of Polη were similar, their Km values differed by less than twofold, and the levels of efficiency (kcat/Km) and fidelity of nucleotide incorporation for the two forms of Polη were also quite similar (Table 1). Since both proteins behaved approximately the same, we carried out all further experiments on Polη (1-475), which we will refer to simply as Polη hereafter.

FIG. 1.

Pre-steady-state kinetics of nucleotide incorporation by human Polη. (A) The sequences of the DNA substrate used in this study. (B) Preincubated DNA (200 nM) and Polη (50 nM) were mixed with 500 μM dATP in a rapid chemical quench flow apparatus for various reaction times at 18°C. The solid line represents the best fit to the burst equation with a burst amplitude equal to 43 ± 1 nM, a burst-rate constant equal to 50 ± 5 s−1, and a linear rate equal to 15 ± 2 nM/s.

TABLE 1.

Determinations of steady-state kinetic parameters for correct and incorrect nucleotide insertion by full-length and truncated (1-475) human Polη

| Polymerase | Results

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | (kcat/Km) (μM−1 s−1) | Fidelitya | |

| Full-length Polη | ||||

| Correct | 0.23 ± 0.009 | 0.53 ± 0.07 | 0.43 | |

| Incorrect | 0.063 ± 0.001 | 26 ± 2 | 0.0024 | 180 |

| Polη (1-475) | ||||

| Correct | 0.24 ± 0.005 | 0.32 ± 0.03 | 0.75 | |

| Incorrect | 0.055 ± 0.001 | 17 ± 1 | 0.0032 | 230 |

Fidelity was calculated by the following equation: (kcat/Km)correct/(kcat/Km)incorrect.

Human Polη displays biphasic kinetics.

To determine whether human Polη displayed biphasic or “burst” kinetics, we used the Rapid Chemical Quench Flow instrument to examine the incorporation of the correct nucleotide dATP opposite a template T (Fig. 1A) under pre-steady-state conditions. Preincubated Polη (50 nM final concentration) and the DNA substrate (200 nM) in one syringe were rapidly mixed with dATP (500 μM) from the other syringe. Figure 1B shows the amount of product formed graphed as a function of time. The kinetics of product formation was indeed biphasic. The fast, pre-steady-state burst phase corresponds to the incorporation of nucleotide during the first enzyme turnover, while the slow, steady-state linear phase corresponds to the incorporation of nucleotide during subsequent enzyme turnovers.

Burst kinetics occurs whenever the slowest step of the nucleotide incorporation reaction follows the chemical step. The slowest step, which is likely the dissociation of Polη from the DNA substrate, limits the rate of the subsequent steady-state turnovers but not the rate of the first enzyme turnover. Consequently, the presence of a pre-steady-state burst phase provided an opportunity to examine nucleotide incorporation in the first enzyme turnover and to assess the contributions of the nucleotide binding step and the nucleotide incorporation step toward the efficiency and fidelity of nucleotide incorporation by human Polη.

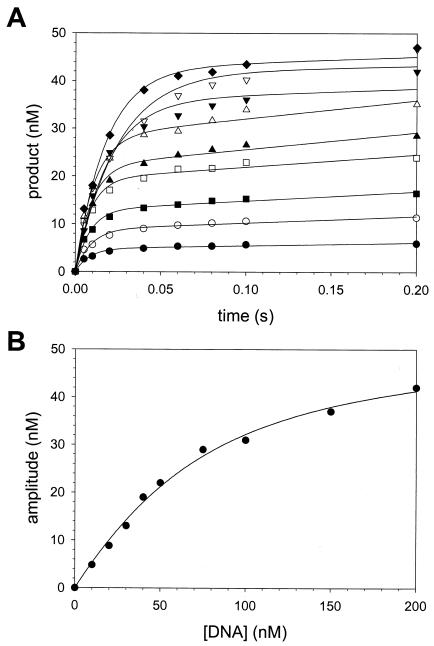

Determination of the KDDNA and the concentration of active human Polη.

To find the appropriate conditions under which to carry out subsequent experiments for examining the kinetics of correct and incorrect nucleotide incorporation in the first enzyme turnover, we needed to obtain a KDDNA value for the Polη-DNA complex and to determine the value for a concentration of active Polη molecules. Because the amplitude of the pre-steady-state burst phase is a measure of the amount of active Polη-DNA complex at the start of the reaction, we were able to obtain these values by examining the correspondence of the pre-steady-state burst amplitude to the concentration of the DNA substrate.

Preincubated Polη (60 nM total concentration as judged by two methods; see Materials and Methods) and various concentrations (10 to 200 nM) of the DNA substrate were rapidly mixed with 500 μM dATP (Fig. 2A). The amplitudes of the pre-steady-state burst phases were graphed as a function of total DNA concentration (Fig. 2B), and a KDDNA value of 38 nM for the Polη-DNA complex and a concentration value of 50 nM for active Polη molecules were obtained from the best-fit curve. Thus, the Polη preparation used in this study was 83% active and the concentration of Polη used in all experiments was corrected for the concentration of active enzyme.

FIG. 2.

Active-site titration of human Polη. (A) Preincubated Polη (60 nM total protein) and various concentrations of DNA (•, 10 nM; ○, 20 nM; ▪, 30 nM; □, 40 nM; ▴, 50 nM; ▵, 75 nM; ▾, 100 nM; ▿, 150 nM; and ♦, 200 nM) were mixed with 500 μM dATP for various reaction times. The solid lines represent the best fits to the burst equation. (B) The burst amplitudes (•) were graphed as a function of [DNA], and the solid line represents the best fit to the quadratic equation with a KDDNA for the Polη-DNA complex equal to 38 ± 4 nM and the active-site concentration of Polη equal to 50 ± 2 nM.

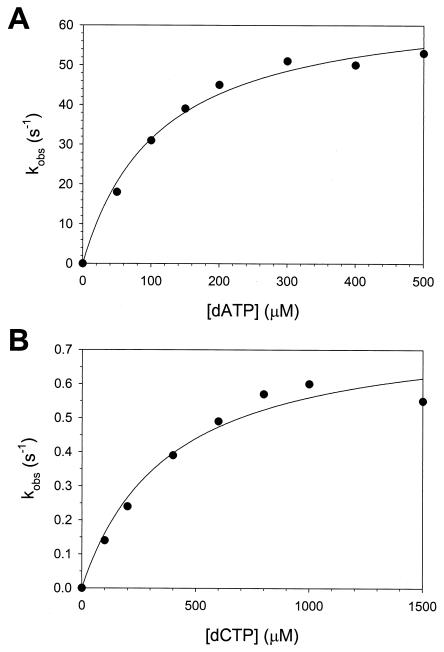

Determination of KDdNTP and kpol for nucleotide incorporation by human Polη.

To understand the mechanistic basis of the low level of fidelity of Polη, we needed to measure the KDdNTP for the Polη-DNA-dNTP ternary complex and the maximum rate constant of nucleotide incorporation in the first enzyme turnover (kpol) for the correct and the incorrect nucleotides. These values can be obtained by the examination of the variation of the observed rate constant (kobs) of the pre-steady-state burst phase as a function of dNTP concentration. First, we examined this concentration dependence with the correct nucleotide, dATP (Fig. 3A); we obtained a KDdATP of 110 μM and a kpol of 67 s−1 from the best-fit curve (Table 2). Next, we examined the concentration dependence with the incorrect nucleotide, dCTP (Fig. 3B); we obtained a KDdCTP of 380 μM and a kpol of 0.77 s−1 from the best-fit curve (Table 2).

FIG. 3.

Concentration dependence of the rate of nucleotide incorporation by human Polη. (A) For correct nucleotide incorporation, the observed pre-steady-state burst-rate constants (kobs) were graphed as a function of [dATP]; the solid line represents the best fit to the hyperbolic equation with a KDdATP equal to 110 ± 20 μM and a kpol equal to 67 ± 3 s−1. (B) For incorrect nucleotide incorporation, the burst-rate constants (kobs) were graphed as a function of [dCTP]; the solid line represents the best fit to the hyperbolic equation with a KDdCTP equal to 380 ± 100 μM and a kpol equal to 0.77 ± 0.07 s−1.

TABLE 2.

Determinations of pre-steady-state kinetics parameters for correct and incorrect nucleotide incorporation by human DNA Polη, yeast DNA Polη, and the Klenow fragment of E. coli DNA polymerase I

| Polymerase | Results

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KDdNTP (μM) | kpol (s−1) | kpol/KDdNTP | KDdNTPincorrect/KDdNTPcorrect | kpolcorrect/kpolincorrect | Fidelitya | |

| Human Polη | ||||||

| Correct | 110 | 67 | 0.61 | |||

| Incorrect | 380 | 0.77 | 2.0 × 10−3 | 3.5 | 87 | 300 |

| Yeast Polηb | ||||||

| Correct | 2.4 | 1.3 | 0.54 | |||

| Incorrect | 13 | 8.7 × 10−3 | 6.7 × 10−4 | 5.4 | 150 | 810 |

| E. coli Klenow fragmentc | ||||||

| Correct | 5 | 50 | 10 | |||

| Incorrect | 17 | 1.0 × 10−2 | 5.9 × 10−4 | 3.4 | 5,000 | 17,000 |

Human Polη exhibits only a slight elemental effect.

We also examined the effects of substituting a sulfur atom for an oxygen atom at the α-phosphate of the incoming nucleotide. These experiments are usually done to ascertain whether the rate-limiting step in the first enzyme turnover (kpol) corresponds to the chemical step of phosphodiester bond formation or to a conformational change step immediately prior to the chemical step. A small (less than fourfold) elemental effect is taken as evidence of a rate-limiting conformational change step, because the sulfur substitution is expected to reduce the rate of the chemical step by a fourfold or greater amount (6); a larger elemental effect, however, would occur if the chemical step were rate limiting. For Polη incubated with 500 μM of either dATP or dATPαS (the correct nucleotide), the pre-steady-state burst-rate constants were 45 s−1 and 29 s−1, respectively, which corresponds to an elemental effect of 1.6. For Polη incubated with 1,500 μM of either dCTP or dCTPαS (the incorrect nucleotide), the pre-steady-state burst-rate constants were 0.52 s−1 and 0.21 s−1, respectively, which corresponds to an elemental effect of 2.5. These observations support the presence of a rate-limiting conformational change step in the first turnover of human Polη, although they by no means demand it.

DISCUSSION

Rate-limiting step in the first turnover of human Polη.

We measured the kpol and KDdNTP values for the correct and incorrect nucleotide incorporation by human Polη and have presented evidence consistent with a conformational change being rate limiting in the first enzyme turnover. For human Polη, the existence of a rate-limiting conformational change step is inferred from the small elemental effects (1.6-fold and 2.5-fold for the incorporation of the correct and incorrect nucleotides, respectively) observed when a sulfur atom was substituted for an oxygen atom on the α-phosphate of the incoming nucleotide. If the chemical step of phosphodiester bond formation were rate limiting instead, then we would have expected the kpol to have decreased by at least fourfold upon the sulfur substitution (6). The lack of an elemental effect, however, cannot be considered definitive, and additional experimental evidence is needed to unambiguously assign the rate-limiting step to a conformational change. Further evidence with other DNA polymerases for a rate-limiting conformational change step has come from comparisons of pulse-chase and pulse-quench single-turnover experiments (3, 24). The observation of a difference in amplitude between the pulse-chase and pulse-quench experiments indicates the accumulation of an intermediate species in which the nucleotide is stably bound to the enzyme prior to the chemical step. Such experiments have provided compelling evidence for the presence of a rate-limiting conformational change step for the Klenow fragment (3) and also for yeast Polη (24). However, the low level of affinity for nucleotide binding displayed by human Polη makes pulse-chase experiments impractical, as the high nucleotide concentrations necessary to perform the chase cannot be readily achieved.

Although the evidence for a rate-limiting conformational change in human Polη is not in itself compelling, the case for a rate-limiting conformational change step with yeast Polη is strong. Hence, by analogy with the yeast enzyme and in the absence of any evidence to the contrary, we tentatively assign the rate-limiting step in the first turnover of human Polη to be a conformational change immediately preceding chemistry.

The mechanism of nucleotide incorporation by human Polη differs from that of yeast Polη.

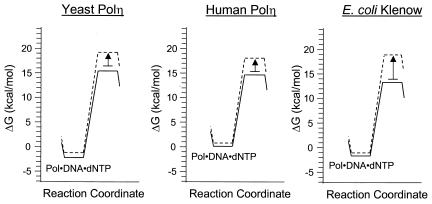

Yeast Polη and human Polη behave similarly under steady-state conditions, as mentioned earlier, and we anticipated that their pre-steady-state mechanisms would also be similar. Surprisingly, we found that the mechanism of human Polη differs from that of yeast Polη in several respects. First, the kpol is faster in the case of the human enzyme than in that of the yeast enzyme. In fact, unlike the kpol of the yeast enzyme, the kpol of the human enzyme is comparable in magnitude to that of the Klenow fragment of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I, a prototypical classical DNA polymerase (Table 2). This can clearly be seen in the free-energy diagrams (Fig. 4), as the activation barrier (ΔG‡) for correct nucleotide incorporation is larger for yeast Polη (17.6 kcal/mol) than it is for either human Polη (14.6 kcal/mol) or for the Klenow fragment (15.0 kcal/mol). However, compared to the results for the Klenow fragment, the differential in kpol for the correct and the incorrect nucleotides is not very large for human Polη. Again, this can be seen in the free-energy diagrams because the ΔΔG‡ (Fig. 4) is much smaller for human (2.6 kcal/mol) and yeast (3.0 kcal/mol) Polη than for the Klenow fragment (5.0 kcal/mol).

FIG. 4.

Gibbs free-energy profiles of yeast Polη, human Polη, and the Klenow fragment of E. coli polymerase (Pol) I. The free-energy changes corresponding to the initial nucleotide binding event and the subsequent rate-limiting nucleotide incorporation event were calculated from the KDdNTP and kpol values, assuming 100 μM dNTP concentration. The solid lines represent the incorporation of the correct nucleotide, the dashed lines represent incorporation of the incorrect nucleotide, and the arrows represent the ΔΔG‡. The KDdNTP and kpol values for the Klenow fragment are from Kuchta et al. (12, 13), and the values for yeast Polη are from Washington et al. (24).

Another difference between human and yeast Polη involves the binding affinity for the nucleotide. The KD for the nucleotide is much higher in the case of the human enzyme than in that of the yeast enzyme, indicating that the human enzyme binds to the nucleotide with weaker affinity than the yeast enzyme. This too can be seen in the free-energy diagrams (Fig. 4), as the level of the energy minima corresponding to the Polη-DNA-dNTP ternary complex (ΔG) is higher in the case of the human enzyme (0.06 kcal/mol) than in that of the yeast enzyme (−2.2 kcal/mol).

Interestingly, despite the clear differences observed in the pre-steady-state kinetics of the yeast and human enzymes, these mechanisms yield similar steady-state kinetic constants for the two enzymes. The reason for this is that the kpol/KD values for these enzymes are similar (Table 2). If nucleotide binding involves a rapid equilibrium, which is a reasonable assumption, then the kpol/KD value should be numerically equal to the kcat/Km steady-state kinetic parameter (compare Table 1 and Table 2). Thus, if both enzymes had similar rates of DNA dissociation (i.e., similar values for kcat), then the Km values would likewise have to be similar. This represents an important example of two divergent mechanisms yielding precisely the same results under steady-state analysis, highlighting the necessity for pre-steady-state kinetic studies to address these detailed mechanistic questions.

While the rate (kcat) and efficiency (kcat/Km) values of single-nucleotide incorporation for yeast and human Polη measured under steady-state conditions are approximately the same (11, 23), we must emphasize that the single-nucleotide incorporation reaction under steady-state conditions is not as biologically relevant as the processive nucleotide incorporation reaction (in which the enzyme incorporates multiple nucleotides prior to dissociating from the DNA). In general, the rate of nucleotide incorporation measured in the first enzyme turnover better reflects the rate of nucleotide incorporation during processive DNA synthesis. Under processive DNA synthesis conditions in the cell, consequently, the yeast and human enzymes would behave quite differently. Under conditions of nucleotide saturation, for instance, the human enzyme would incorporate nucleotides processively at a ∼50-fold-faster rate than the yeast enzyme.

Structural basis of the mechanistic differences.

The primary structures of the human and yeast enzymes are quite similar (8, 14); in the region corresponding to the palm, fingers, thumb, and PAD domains of yeast Polη, moreover, the human enzyme shares a high degree of sequence similarity with the yeast enzyme (20). Despite this structural conservation, the significant mechanistic differences between these enzymes must arise from differences in the way they interact with their substrates. For example, the decrease in the affinity of human Polη for the incoming nucleotide compared to that of yeast Polη must have resulted from the relatively fewer contacts between the human enzyme and the nucleotide in the ground state whereas the faster rate of nucleotide incorporation in the first turnover with human Polη must have resulted from additional contacts with the nucleotide and DNA substrates in the transition state for this step. An understanding of the structural basis of the mechanistic differences between these enzymes will require a comparison of the yet-to-be-determined high-resolution structures of the ternary complexes of yeast and human Polη with DNA and dNTP. In addition, studies of site-directed mutant proteins will be necessary to determine the contributions of individual amino acid residues to the stabilization of ground-state nucleotide binding as well as to the stabilization of the transition state of the nucleotide incorporation steps.

Regulatory implications of the mechanism of human Polη.

A role of a low level of substrate affinity in the regulation of enzymatic activity is a common phenomenon. Enzymes with a low level of substrate affinity are able to respond rapidly to variations in the concentrations of their substrates by increasing their reaction rates in a directly proportional manner. The classic example of this phenomenon is liver glucokinase. When blood glucose levels are low, glucokinase is relatively inactive so that the glucose can be utilized by the other cells of the body. When blood glucose levels are high, however, glucokinase becomes very active and phosphorylates the excess glucose, initiating its conversion to glycogen.

A direct consequence of the lower level of nucleotide binding affinity of human Polη is that its activity would be more sensitive to cellular dNTP concentrations than that of the yeast enzyme, and as the cellular dNTP concentrations rise, so would the activity of the human enzyme. It is an intriguing possibility that this provides for a significant degree of regulation in humans of the activity of this rather low-fidelity polymerase. Thus, at low dNTP concentrations such as one would find in resting cells (18, 19), human Polη would be relatively inactive, whereas at the high dNTP concentrations that are likely to occur in dividing cells with DNA damage, its activity would rise. Yeast cells possess higher dNTP levels during the DNA synthesis (S) phase than at other cell cycle stages, and DNA damage elicits a manyfold increase in their levels (2). Although a similar DNA damage-dependent elevation of dNTP concentrations has not yet been documented in human cells, it is quite likely that a similar phenomenon exists. In that case, by primarily restricting the activity of Polη to cells with DNA damage, humans can avoid the mutagenic consequences arising from the inadvertent action of this enzyme in undamaged cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM19261 and NIEHS grant ES012411.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carroll, S. S., and S. J. Benkovic. 1990. Mechanistic aspects of DNA polymerases: Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment) as a paradigm. Chem. Rev. 90:1291-1307. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chabes, A., B. Georgieva, V. Domkin, X. Zhao, R. Rothstein, and L. Thelander. 2003. Survival of DNA damage in yeast directly depends on increased dNTP levels allowed by relaxed feedback inhibition of ribonucleotide reductase. Cell 112:391-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahlberg, M. E., and S. J. Benkovic. 1991. Kinetic mechanism of DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment): Identification of a second conformational change and evaluation of the internal equilibrium constant. Biochemistry 30:4835-4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haracska, L., S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 2000. Replication past O6-methylguanine by yeast and human DNA polymerase η. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:8001-8007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haracska, L., S.-L. Yu, R. E. Johnson, L. Prakash, and S. Prakash. 2000. Efficient and accurate replication in the presence of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine by DNA polymerase η. Nat. Genet. 25:458-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herschlag, D., J. A. Piccirilli, and T. R. Cech. 1991. Ribozyme-catalyzed and nonenzymatic reactions of phosphate diesters: rate effects upon substitution of sulfur for a nonbridging phosphoryl oxygen atom. Biochemistry 30:4844-4854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson, K. A. 1993. Conformational coupling in DNA polymerase fidelity. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 62:685-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson, R. E., C. M. Kondratick, S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 1999. hRAD30 mutations in the variant form of xeroderma pigmentosum. Science 285:263-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson, R. E., S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 1999. Efficient bypass of a thymine-thymine dimer by yeast DNA polymerase, Polη. Science 283:1001-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson, R. E., S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 1999. Requirement of DNA polymerase activity of yeast Rad30 protein for its biological function. J. Biol. Chem. 274:15975-15977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson, R. E., M. T. Washington, S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 2000. Fidelity of human DNA polymerase η. J. Biol. Chem. 275:7447-7450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuchta, R. D., P. Benkovic, and S. J. Benkovic. 1988. Kinetic mechanism whereby DNA polymerase I (Klenow) replicates DNA with high fidelity. Biochemistry 27:6716-6725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuchta, R. D., V. Mizrahi, P. A. Benkovic, K. A. Johnson, and S. J. Benkovic. 1987. Kinetic mechanism of DNA polymerase I (Klenow). Biochemistry 26:8410-8417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masutani, C., R. Kusumoto, A. Yamada, N. Dohmae, M. Yokoi, M. Yuasa, M. Araki, S. Iwai, K. Takio, and F. Hanaoka. 1999. The XPV (xeroderma pigmentosum variant) gene encodes human DNA polymerase η. Nature 399:700-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuda, T., K. Bebenek, C. Masutani, F. Hanaoka, and T. A. Kunkel. 2000. Low fidelity DNA synthesis by human DNA polymerase η. Nature 404:1011-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald, J. P., A. S. Levine, and R. Woodgate. 1997. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD30 gene, a homologue of Escherichia coli dinB and umuC, is DNA damage inducible and functions in a novel error-free postreplication repair mechanism. Genetics 147:1557-1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel, S. S., I. Wong, and K. A. Johnson. 1991. Pre-steady state kinetic analysis of processive DNA replication including complete characterization of an exonuclease-deficient mutant. Biochemistry 30:511-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reichard, P. 1988. Interactions between deoxyribonucleotide and DNA synthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 57:349-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Traut, T. W. 1994. Physiological concentrations of purines and pyrimidines. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 140:1-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trincao, J., R. E. Johnson, C. R. Escalante, S. Prakash, L. Prakash, and A. K. Aggarwal. 2001. Structure of the catalytic core of S. cerevisiae DNA polymerase η: implications for translesion DNA synthesis. Mol. Cell 8:417-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang, Y.-C., V. M. Maher, D. L. Mitchell, and J. J. McCormick. 1993. Evidence from mutation spectra that the UV hypermutability of xeroderma pigmentosum variant cells reflects abnormal, error-prone replication on a template containing photoproducts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:4276-4283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Washington, M. T., R. E. Johnson, S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 2000. Accuracy of thymine-thymine dimer bypass by Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase η. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:3094-3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Washington, M. T., R. E. Johnson, S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 1999. Fidelity and processivity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase η. J. Biol. Chem. 274:36835-36838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Washington, M. T., L. Prakash, and S. Prakash. 2001. Yeast DNA polymerase η utilizes an induced fit mechanism of nucleotide incorporation. Cell 107:917-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waters, H. L., S. Seetharam, M. M. Seidman, and K. H. Kraemer. 1993. Ultraviolet hypermutability of a shuttle vector propagated in xeroderma pigmentosum variant cells. J. Investig. Dermatol. 101:744-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong, I., S. S. Patel, and K. A. Johnson. 1991. An induced-fit kinetic mechanism for DNA replication fidelity: direct measurement by single-turnover kinetics. Biochemistry 30:526-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu, S.-L., R. E. Johnson, S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 2001. Requirement of DNA polymerase η for error-free bypass of UV-induced CC and TC photoproducts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:185-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]