Abstract

We analyzed a large collection of Escherichia coli isolates typed by enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus (ERIC)-PCR with BioNumerics gel analysis software. However, the interexperimental variation of ERIC-PCR caused the computer software to classify repeated isolates as different. ERIC-PCR should not be used as the sole determinant of genetic similarity when typing large numbers of bacterial isolates via computer software.

Enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus (ERIC) sequences are short, highly conserved 126-bp noncoding regions found in Enterobacteriaceae (4, 14, 16, 19). ERIC-PCR uses any combination of primers designed to the conserved ERIC region in order to generate an electrophoretic banding pattern based on the frequency and orientation of ERIC sequences in a bacterial genome. Molecular genotyping by ERIC-PCR is faster and more cost-effective than pulsed-field gel electrophoresis or multilocus sequencing for generating information about the genetic similarity of bacterial strains. For many organisms, it possesses a higher discriminatory ability than that of other quick-typing techniques, leading to its increased frequency of use (1, 3, 13, 17). However, questions have been raised about the reproducibility of ERIC-PCR between experiments (5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 15, 17, 18).

In molecular epidemiologic studies describing the genotypic diversity of a large number of isolates, analysis of overall relatedness is usually dependent on computer interpretation of molecular fingerprints. Slight inconsistencies between PCRs pose a severe problem when a substantial number of fingerprints from multiple different PCRs are compared.

We began an investigation of the genetic relatedness of 350 uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains from different countries, mostly in Europe. DNA was extracted from overnight growth of pure subcultures that were then lysed by boiling. Genotyping was performed using the ERIC2 fingerprinting assay, which uses one 22-bp primer designed to the conserved ERIC region (6, 9). PCRs were prepared using reagents from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, Calif.) and performed in the same thermal cycler (MJ Research, Watertown, Mass.). The PCR amplifications were performed in 25-μl volumes containing 5 mM MgCl2, 2 U of Platinum Taq polymerase, 0.4 mM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Invitrogen), 10 ng of crude template DNA, and 25 pmol of the ERIC2 primer (5′-AAGTAAGTGACTGGGGTGAGCG-3′). A negative control consisting of the same reaction mixture without a DNA template was included in each PCR. PCR amplification included a 2-min hot start at 94°C, denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 60°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 4.5 min and, after 35 cycles, a final extension for 1 min at 72°C. Amplified PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis on 2.0% agarose (Molecular Bio Grade; Fisher Biotech) gels (6 by 6 in.) and normalized using a 100-bp ladder (Invitrogen) in three evenly spaced lanes per gel. Gels were run at 100 V for 3 h, stained with 0.35 μg of ethidium bromide in 150 ml of distilled water for 20 min, visualized, and saved as tagged image files by using Gel Doc 2000 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.).

Electrophoretic patterns were entered into BioNumerics gel analysis software (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). To ensure adequate gel-to-gel banding pattern comparison, the analysis includes a normalization step which makes each lane an equal length. A process of “band scoring” identifies bands in each lane that combine to make the fingerprint based on the threshold of stringency and optimization settings, which we set at 1.0% (10).

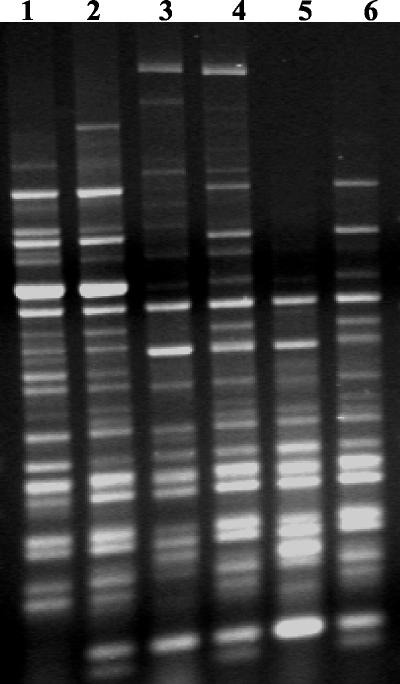

We found banding patterns to vary slightly by PCR, consistent with findings of other researchers. Bright bands are generally consistent, but lighter bands are often subject to interexperimental variability and are often ignored by the human reader (3, 11, 15, 18). By utilizing computer software, we hoped to control for the band intensity variability found in the literature. Shift in band intensity is not a problem when band-based analysis is performed, which takes into account only the presence or absence of bands. However, we found inconsistencies in the presence of bands as well. Band gain and loss pose a severe problem for computer-based analysis. Lighter bands can become darker or lighter or even disappear between different experiments (Fig. 1). Some researchers have eliminated light bands from analysis with the intention of eliminating the irreproducibility of fingerprints (9, 15). Choosing which bands will be included in a given molecular fingerprint introduces subjective bias and reduces the fingerprint down to only a few bands, significantly reducing the discriminatory power of the technique.

FIG. 1.

Gel electrophoresis of three repeat isolates of ERIC2-PCR on E. coli. Lanes 1 and 2 are a single isolate from separate PCR experiments. Lanes 3 and 4 and lanes 5 and 6 are similar pairs.

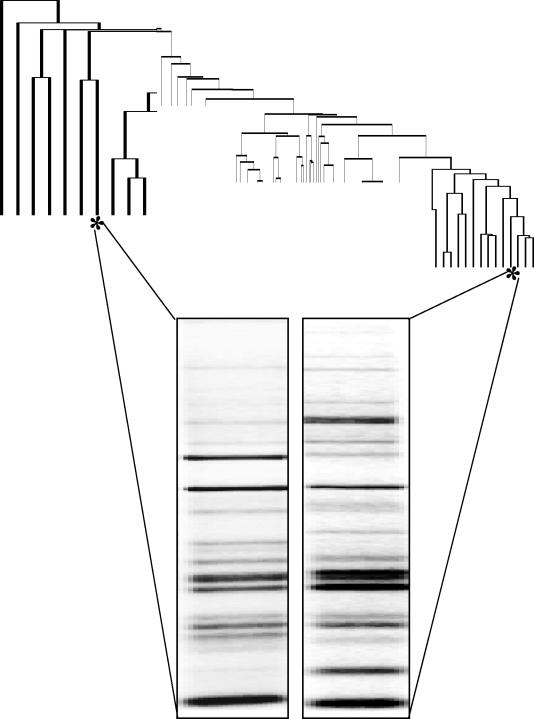

To assess the repeatability of this technique, repeated samples were included throughout the study. Repeated PCR and gel electrophoresis patterns of the same isolates, though appearing somewhat alike, possessed slight differences in band presence. When computer analysis was performed, these slight inconsistencies caused these strains to be classified as very different. Upon generation of a dendrogram including the repeated samples, the same strain was rarely within 90% homology of itself and sometimes at a much greater divergence (Fig. 2). Figure 2 demonstrates the furthest divergence (36%; 64% homology) between two repeat samples in our dendrogram. The overall homology of the tested strains was 55.4%. The two banding patterns, though similar, clearly demonstrate the interexperimental irreproducibility of bands. This may not cause an analytic problem if the same isolate is still closer to itself on a dendrogram than it is to other strains, but this was not the case. In the literature, the determination that ERIC-PCR possesses a high discriminatory power is independent of any examination of reproducibility, which hinders clear determination of strain differences (6, 8). Though intra- and interexperimental variabilities are both important in the analysis of any typing technique, the greatest hindrance to the reproducibility of PCR fingerprinting comes in comparison of different PCR experiments and different gel runs (6).

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the divergence of a single isolate between different PCRs. The inconsistency of the presence and absence of bands between experiments leads to very different placement of a single isolate on a dendrogram. For illustrative purposes, the majority of the dendrogram is condensed.

When genotyping a large number of isolates, it is difficult to include all isolates in the same reaction and on the same gel. When the number of isolates is small and there is additional information, as in an outbreak investigation or a comparison of isolates from one individual, ERIC-PCR is appropriate for quick or preliminary typing (2, 5, 12, 15). It is too variable a technique for use as the sole determinant of genetic relatedness when computer software is utilized. It is possible that improvements in resolution of ERIC-PCR fragments by techniques other than the standard agarose gel electrophoresis, such as acrylamide gel electrophoresis, high-pressure liquid chromatography, or capillary electrophoresis, may improve fragment detection. However, it is not clear that these improvements would make ERIC-PCR a cost-effective alternative to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Weijtens et al. (17) suggest that an additional genotyping technique in conjunction with ERIC-PCR may be necessary if the goal of the research is prove an epidemiological link or to compare isolates from separate PCR experiments. Researchers should be aware of problems associated with using ERIC-PCR beyond the limits of the technique.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant RO1-DK55496.

We thank Gunnar Kahlmeter for providing the uropathogenic E. coli samples from the ECO-SENS surveillance study in Europe and Canada, Patricia Tallman for laboratory support, and Amee Manges for technical assistance with the ERIC2 assay.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ben-Hamouda, T., T. Foulon, A. Ben-Cheikh-Masmoudi, C. Fendri, O. Belhadj, and K. Ben-Mahrez. 2003. Molecular epidemiology of an outbreak of multiresistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Tunisian neonatal ward. J. Med. Microbiol. 52:427-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cimolai, N., C. Trombley, D. Wensley, and J. LeBlanc. 1997. Heterogeneous Serratia marcescens genotypes from a nosocomial pediatric outbreak. Chest 111:194-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de la Puente-Redondo, V. A., N. Garcia del Blanco, C. B. Gutierrez-Martin, F. J. Garcia-Pena, and E. F. Rodriguez Ferri. 2000. Comparison of different PCR approaches for typing Francisella tularensis strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1016-1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hulton, C. S. J., C. F. Higgins, and P. M. Sharp. 1991. ERIC sequences: a novel family of repetitive elements in the genomes of Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium and other enterobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 5:825-834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson, J. R., C. Clabots, M. Azar, D. J. Boxrud, J. M. Besser, and J. R. Thurn. 2001. Molecular analysis of a hospital cafeteria-associated salmonellosis outbreak using modified repetitive element PCR fingerprinting. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3452-3460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson, J. R., and T. T. O'Bryan. 2000. Improved repetitive-element PCR fingerprinting for resolving pathogenic and nonpathogenic phylogenetic groups within Escherichia coli. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 7:265-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee, T. M., C. Y. Chang, L. L. Chang, W. M. Chen, T. K. Wang, and S. F. Chang. 2003. One predominant type of genetically closely related Shigella sonnei prevalent in four sequential outbreaks in school children. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 45:173-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loubinoux, J., A. Lozniewski, C. Lion, D. Garin, M. Weber, and A. E. Le Faou. 1999. Value of enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus PCR for study of Pasteurella multocida strains isolated from mouths of dogs. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2488-2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manges, A. R., J. R. Johnson, B. Foxman, T. O'Bryan, K. E. Fullerton, and L. W. Riley. 2001. Widespread distribution of urinary tract infections caused by a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli clonal group. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:1007-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDaniel, J., and S. D. Pillai. 2002. Gel alignment and band scoring for DNA fingerprinting using Adobe Photoshop. BioTechniques 32:120-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pettigrew, M. M., B. Foxman, Z. Ecevit, C. F. Marrs, and J. Gilsdorf. 2002. Use of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus typing, and automated ribotyping to assess genomic variability among strains of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:660-662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rivera, I. G., M. A. R. Chowdhury, A. Huq, D. Jacobs, M. T. Martins, and R. R. Colwell. 1995. Enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus sequences and the PCR to generate fingerprints of genomic DNAs from Vibrio cholerae O1, O139, and non-O1 strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2898-2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saxena, M. K., V. P. Singh, B. D. Lakhcharua, G. Taj, and B. Sharma. 2002. Strain differentiation of Indian isolates of Salmonella by ERIC-PCR. Res. Vet. Sci. 73:313-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharples, G. J., and R. G. Lloyd. 1990. A novel repeated DNA sequence located in the intergenic regions of bacterial chromosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:6503-6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soto, S. M., B. Guerra, A. del Cerro, M. A. Gonzalez-Hevia, and M. C. Mendoza. 2001. Outbreaks and sporadic cases of Salmonella serovar Panama studied by DNA fingerprinting and antimicrobial resistance. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 71:35-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Versalovic, J., T. Koeuth, and J. R. Lupski. 1991. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:6823-6831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weijtens, M. J. B. M., R. D. Reinders, H. A. P. Urlings, and J. Van der Plas. 1999. Campylobacter infections in fattening pigs; excretion pattern and genetic diversity. J. Appl. Microbiol. 86:63-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong, H., and C. Lin. 2001. Evaluation of typing of Vibrio parahaemolyticus by three PCR methods using specific primers. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4233-4240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woods, C. R., J. Versalovic, T. Koeuth, and J. R. Lupski. 1993. Whole cell repetitive element sequence-based polymerase chain-reaction allows rapid assessment of clonal relationships of bacterial isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:1927-1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]