Abstract

Dermatophytes are common pathogens of skin but rarely cause invasive disease. We present a case of deep infection by Trichophyton rubrum in an immunocompromised patient. T. rubrum was identified by morphological characteristics and confirmed by PCR. Invasiveness was apparent by histopathology and immunohistochemistry. The patient was treated successfully with itraconazole.

CASE REPORT

A 56-year-old male was admitted for evaluation of elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), anemia, and multiple subcutaneous nodules on both legs. The patient was under close medical supervision due to an autoimmune disease with liver, cardiac, and lung involvement.

His medical history included pericarditis (27 years before admission), and a profound jaundice after a respiratory infection treated with cefuroxime (3 years before admission). Serology was negative for hepatitis viruses and positive for antiparietal, antinuclear, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Liver biopsy revealed a profound destruction of liver architecture, fibrosis, active inflammation, and cholestasis. Treatment with steroids was followed by a good clinical response and normalization of liver enzymes. Attempts to wean the patient from steroids including administration of azathioprine and cyclosporine failed, and during the 2 years prior to admission he received both prednisone and cyclosporine. Several weeks before admission, he was evaluated for a chronic cough. He had undergone a transbronchial biopsy that disclosed chronic inflammation and thickening of the basement membrane, without any specific diagnosis, but responded to an increase of the dose of steroids. A few weeks later, while trying to taper the steroids, he developed multiple, hard cutaneous nodules, distributed mainly on the lower limbs. Some later softened and discharged caseous material spontaneously.

Other underlying conditions included glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, nephrolithiasis, benign prostate hypertrophy, bilateral inguinal hernia repair, and osteoporosis.

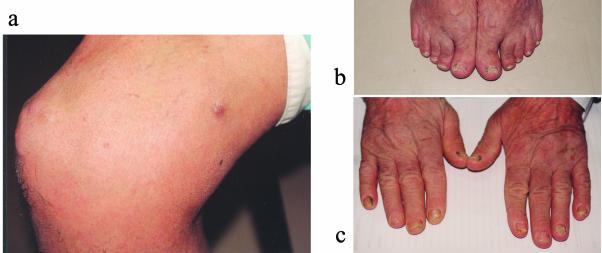

On admission, medications included prednisone (10 mg once a day [QD]), cyclosporine (100 mg QD), ursodeoxycholic acid (300 mg twice a day), alendronate (10 mg QD), omeprazole (20 mg QD), and calcium (600 mg) and vitamin D (0.25 μg) once daily. On physical examination, rhonchi were heard over both lungs. A few hard, mobile subcutaneous nodules were present on both lower limbs, mainly around the knees and thighs (Fig. 1a), and the sacral area. Some of these nodules were purplish and soft. Onychomycosis was present on the feet and both hands (Fig. 1b and c).

FIG. 1.

Clinical signs at admission. (a) Multiple firm nodules can be seen over the patella. A softer, purple nodule can be seen on the thigh. (b) Onychomycosis of feet. (c) Onychomycosis of both hands.

Laboratory test results were as follows: ESR, 80; hemoglobin level, 10.8 g/dl; leukocyte count, 7,900/μl (42% granulocytes); albumin level, 34 g/liter; total protein level, 83 g/liter; liver enzyme levels, normal.

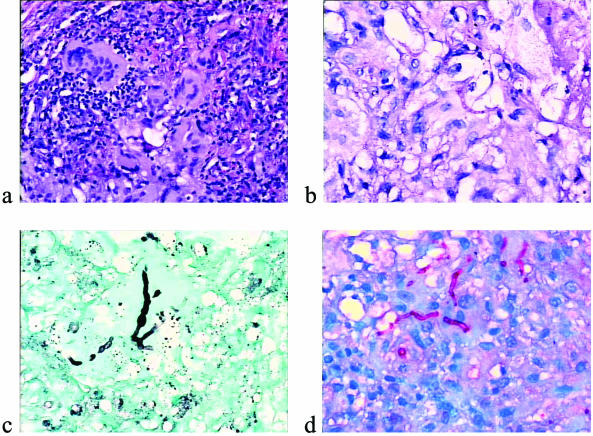

Two of the patient's nodules were excised. A granulomatous inflammatory reaction was present in the dermis and hypodermis. It was composed of monocytes, macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, and rare neutrophils (Fig. 2). Septate hyphae were revealed by both periodic acid-Schiff staining (PAS) and Gomori methamine staining (GMS) inside and outside the macrophages. Immunohistochemistry was performed by the avidin-biotin-peroxidase method (3, 22). Antibodies are listed in Table 1. A majority of the inflammatory cell infiltrate was composed of Mac 387+ CD68+ macrophages, which outnumbered the CD45+ lymphocytes. Factor XIIIa+ dermal dendrocytes were present only in the surrounding connective tissue. Fungal hyphae were labeled by anti-Mycobacterium and anti-Trichophyton antibodies (Fig. 2). Immunostaining for Aspergillus and Fusarium spp. was negative.

FIG. 2.

Histology of nodules. (a) Granulomatous reaction with many multinucleated cells (hematoxylin-eosin stain). (b) Typical fungal hyphae within the granuloma (PAS stain). (c) Pleomorphic fungal hyphae as seen by GMS staining. (d) Immunohistochemistry with an anti-Trichophyton antibody showing intracellular hyphae.

TABLE 1.

Panel of antibodies

| Antibody | Dilution | Target | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-CD45 | 1:200 | Lymphocytes | Dako |

| Mac 387 | 1:200 | Monocytes-macrophages | Dako |

| Anti-factor XIIIa | 1:50 | Dermal dendrocytes | Biogenex |

| Anti-CD68 | 1:200 | Macrophages | Dako |

| Anti-Mycobacteria | 1:200 | Various microorganisms | Dako |

| Anti-Aspergillus | 1:50 | Aspergillus spp. | Dako |

| Anti-Fusarium | 1:50 | Fusarium spp. | University of Liège |

| Anti-Trichophyton | 1:50 | Trichophyton spp. | University of Liège |

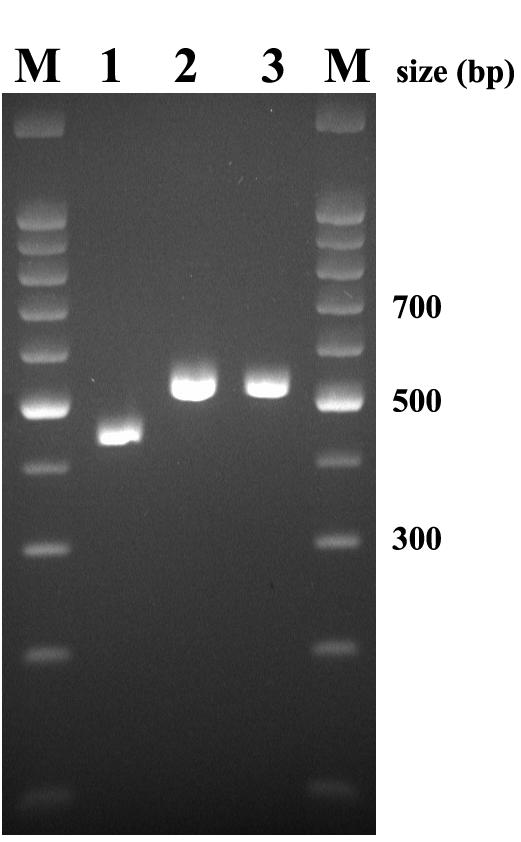

Specimens of pus and nodules were cultured on potato dextrose agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). Trichphyton rubrum was identified according to its characteristic morphology on Trichphyton agar (Difco): granular white colonies with blood-red reverse and production of clavate to pyriform microconidia (5). This identification was confirmed by a PCR-based typing method that analyzes variations in numbers of repetitive elements in the nontranscribed spacer region of the rRNA gene repeats (Fig. 3) (11). This PCR test, using two different sets of primers, is specific for T. rubrum (and very closely related species such as Trichphyton violaceum). This isolate was type TRS1-I, TRS2-II, which is a very common T. rubrum type (11) (TRS1 type data not shown). This PCR failed to amplify any product from DNA extracted from the paraffin-embedded tissue.

FIG. 3.

PCR confirmation of the identity of the T. rubrum isolate. DNA was extracted from a colony and amplified with primers to detect the TRS2 type. M, molecular weight marker; lane 1, reference isolate T4-12/12, TRS2 type I; 2, reference isolate T5-0/12, TRS2 type II; 3, case isolate, TRS2 type II.

The patient was treated with itraconazole at 400 mg/day for 1 month, followed by 200 mg/day for two more months until complete disappearance of the nodules and healing of the onychomycosis. After 1 year of follow-up, there was no sign of any clinical or mycological recurrence.

Dermatophytes are common fungal pathogens that produce mainly superficial infections of the skin, nails, and hair. One of the most prevalent species of this group is T. rubrum (7, 20). Rarely, these pathogens cause a more aggressive and invasive form of infection (1, 4, 6, 9, 14, 18, 19) that may present in one of three major patterns, as follows. (i) Majocchi's granuloma (nodular granulomatous perifolliculitis), described more than a century ago (13), is an infection of dermal and subcutaneous tissue, related to disruption of hair follicles and spillage of fungi into the dermis, which produces a granulomatous inflammation. Both immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients may be affected by this type of infection (4, 17). (ii) In deep or invasive disease, invasion is limited mainly to the extremities, and there is subcutaneous involvement without involvement of other internal organs (4). Patients with this syndrome are usually immunocompromised hosts (4, 9, 14). (iii) In exceptional instances, generalized invasive disseminated infection with dermatophytes has been reported (2, 10, 12, 16, 21).

Our patient had a deep infection with T. rubrum. An extensive workup revealed no evidence for disseminated disease in the liver, bone marrow, or lungs. In patients who have superficial infections with dermatophytes, culture from subcutaneous tissue may be contaminated and thus lead to a misdiagnosis of invasive infection. In our patient, the fungus was observed histologically inside the granuloma. The antibody called “anti-Mycobacteria” attached to the hyphae. This antibody is indeed nonspecific but very sensitive in detecting various microorganisms, including fungi (22). In the present case, the fungi were identified as a Trichophyton sp. by immunohistochemistry using a more specific antibody. Furthermore, the species was confirmed by its typical morphological characteristics on culture and by PCR-based molecular typing. Since patients with this type of infection are found only rarely, it is difficult to establish risk factors for invasiveness. Some authors have suggested that specific T-cell immunity is involved (1), but virulence factors of the specific pathogen may also be important. In our patient, the deep infection occurred while he was on immunosuppressive treatment with steroids and cyclosporine. The source of infection may have been the onychomycosis, which creates a huge reservoir of fungal propagules that may be at the origin of an invasive mycosis in immunocompromised patients (3, 8, 15).

It has been suggested that treatment for deep invasive infection with Trichophyton should include either itraconazole or terbinafine (4), and in some severe cases, surgical debridement is also required. Our patient responded well clinically and mycologically to prolonged use of itraconazole, with a gradual reduction in the size and number of nodules until none was palpable at the end of treatment, and has remained disease free 1 year postinfection.

In conclusion, we have presented a case of locally invasive T. rubrum infection diagnosed by histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and culture. This fungus was identified by morphological characteristics, and the identification was further confirmed by PCR-based molecular typing. To our knowledge, the case presented is the first in which immunohistochemistry and molecular typing were used in the diagnosis of such an invasive fungal infection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akiba, H., Y. Motoki, M. Satoh, K. Iwatsuki, and F. Kaneko. 2001. Recalcitrant trichophytic granuloma associated with NK-cell deficiency in a SLE patient treated with corticosteroid. Eur. J. Dermatol. 11:58-62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araviysky, A. N., R. A. Araviysky, and G. A. Eschkov. 1975. Deep generalized trichophytosis. (Endothrix in tissues of different origin.) Mycopathologia 56:47-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arrese, J. E., C. Pierard-Franchimont, and G. E. Pierard. 1996. Fatal hyalohyphomycosis following Fusarium onychomycosis in an immunocompromised patient. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 18:196-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chastain, M. A., R. J. Reed, and G. A. Pankey. 2001. Deep dermatophytosis: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Cutis 67:457-462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Hoog, G. S., J. Guarro, J. Gene, and M. J. Figueras. 2000. Genus: Trichophyton, p. 954-994. Atlas of clinical fungi, 2nd ed. Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

- 6.Erbagci, Z. 2002. Deep dermatophytoses in association with atopy and diabetes mellitus: Majocchi's granuloma tricophyticum or dermatophytic pseudomycetoma? Mycopathologia 154:163-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans, E. G. 1998. Causative pathogens in onychomycosis and the possibility of treatment resistance: a review. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 38:S32-S36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Girmenia, C., W. Arcese, A. Micozzi, P. Martino, P. Bianco, and G. Morace. 1992. Onychomycosis as a possible origin of disseminated Fusarium solani infection in a patient with severe aplastic anemia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 14:1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grossman, M. E., A. S. Pappert, M. C. Garzon, and D. N. Silvers. 1995. Invasive Trichophyton rubrum infection in the immunocompromised host: report of three cases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 33:315-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hironaga, M., N. Okazaki, K. Saito, and S. Watanabe. 1983. Trichophyton mentagrophytes granulomas. Unique systemic dissemination to lymph nodes, testes, vertebrae, and brain. Arch. Dermatol. 119:482-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson, C. J., R. C. Barton, S. L. Kelly, and E. G. Evans. 2000. Strain identification of Trichophyton rubrum by specific amplification of subrepeat elements in the ribosomal DNA nontranscribed spacer. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4527-4534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lestringant, G. G., S. K. Lindley, J. Hillsdon-Smith, and G. Bouix. 1988. Deep dermatophytosis to Trichophyton rubrum and T. verrucosum in an immunosuppressed patient. Int. J. Dermatol. 27:707-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Majocchi, D. 1883. Sepra una nouva tricofizia (granuloma tricofitico), studi clinici micologici. Bull. R. Accad. Roma 9:220-223. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Novick, N. L., L. Tapia, and E. J. Bottone. 1987. Invasive Trichophyton rubrum infection in an immunocompromised host. Case report and review of the literature. Am. J. Med. 82:321-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierard, G. E., J. E. Arrese, and C. Pierard-Franchimont. 1994. Heterogeneity in fungal nail infections and life-threatening onychomycoses. Br. J. Dermatol. 131:80. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sentamilselvi, G., C. Janaki, A. Kamalam, and A. S. Thambiah. 1998. Deep dermatophytosis caused by Trichophyton rubrum—a case report. Mycopathologia 142:9-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith, K. J., R. C. Neafie, H. G. Skelton III, T. L. Barrett, J. H. Graham, and G. P. Lupton. 1991. Majocchi's granuloma. J. Cutan. Pathol. 18:28-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sommer, S., R. C. Barton, S. M. Wilkinson, W. J. Merchant, E. G. Evans, and M. K. Moore. 1999. Microbiological and molecular diagnosis of deep localized cutaneous infection with Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Br. J. Dermatol. 141:323-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Squeo, R. F., R. Beer, D. Silvers, I. Weitzman, and M. Grossman. 1998. Invasive Trichophyton rubrum resembling blastomycosis infection in the immunocompromised host. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 39:379-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Summerbell, R. C. 1997. Epidemiology and ecology of onychomycosis. Dermatology 194(Suppl. 1):32-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swart, E., and F. J. Smit. 1979. Trichophyton violaceum abscesses. Br. J. Dermatol. 101:177-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiley, E. L., B. Beck, and R. G. Freeman. 1991. Reactivity of fungal organisms in tissue sections using anti-mycobacteria antibodies. J. Cutan. Pathol. 18:204-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]