Abstract

In Germany humans with acute granulocytic ehrlichiosis have not yet been described. Here, we characterized three different genes of Anaplasma phagocytophilum strains infecting German Ixodes ricinus ticks in order to test whether they differ from strains in other European countries and the United States. A total of 1,022 I. ricinus ticks were investigated for infection with A. phagocytophilum by nested PCR and sequence analysis. Forty-two (4.1%) ticks were infected. For all positive ticks, parts of the 16S rRNA and groESL genes were sequenced. The complete coding sequence of the ankA gene could be determined in 24 samples. The 16S rRNA and groESL gene sequences were as much as 100% identical to known sequences. Fifteen ankA sequences were ≥99.37% identical to sequences derived from humans with granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Europe and from a horse with granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Germany. Thus, German I. ricinus ticks most likely harbor A. phagocytophilum strains that can cause disease in humans. Nine additional sequences were clearly different from known ankA sequences. Because these newly described sequences have never been obtained from diseased humans or animals, their biological significance is currently unknown. Based on this unexpected sequence heterogeneity, we propose to use the ankA gene for further phylogenetic analyses of A. phagocytophilum and to investigate the biology and pathogenicity of strains that differ in the ankA gene.

Anaplasma phagocytophilum is a gram-negative, obligately intracellular bacterium that replicates within neutrophils. Recently, the organisms formerly known as Ehrlichia phagocytophila, the causative agent of tick-borne fever in cattle and sheep, Ehrlichia equi, the causative agent of equine granulocytic ehrlichiosis (EGE), and the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) have been assigned to the single species A. phagocytophilum based on 16S rRNA and groESL gene analyses, the presence of shared antigens, and common biological characteristics (15).

A. phagocytophilum is tick transmitted and causes febrile diseases in humans and animals. Clinically, HGE is characterized by fever, headache, myalgia, and arthralgia. Typical laboratory findings are leukopenia, thrombopenia, and elevated liver enzyme levels (5). HGE was first described in the United States in 1994 (12), and more than 600 cases have been reported since then in the United States (5). However, in Europe, HGE has been diagnosed only in a small number of patients living in Slovenia (4, 30, 37), The Netherlands (52), Sweden (7, 25), Norway (26), and Poland (51).

The presence of A. phagocytophilum in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Europe is well documented (1, 3, 13, 14, 20, 24, 28, 33-35, 38, 40, 43, 54). In German I. ricinus ticks, the reported infection rate ranges from 1.6 to 2.3% (6, 17, 21). Despite the presence of A. phagocytophilum in German ticks and seropositivity rates as high as 2.6% in the normal population and 14% in certain risk groups (16, 23), human patients with granulocytic ehrlichiosis have not yet been described in Germany.

We therefore asked whether A. phagocytophilum strains infecting German ticks differ from strains known to be pathogenic in other European countries or in the United States. A total of 1,022 I. ricinus ticks were investigated for the presence of A. phagocytophilum by means of PCR, and the infecting strains were characterized by sequence analysis of three different genes (the 16S rRNA gene, groESL, and ankA).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tick collection.

A total of 1,022 I. ricinus ticks were collected between 1998 and 2001. Of these, 1,019 ticks were from different regions of Germany (733 from Bavaria, 269 from Baden-Württemberg, 8 from Nordrhein-Westfalen, 8 from Lower Saxony, and 1 from Rheinland-Pfalz) and 3 were from Austria. Two hundred eighty-seven ticks had been part of a previous study (6). Ticks were removed from the vegetation or from the fur or skin of dogs, cats, deer, or humans. Six hundred ninety-seven ticks were adult females, 223 were adult males, 73 were nymphs, and 2 were larvae. For 12 adults the sex was not determined, and for 15 ticks the instar was unknown. Ticks were stored at −20°C until analysis.

PCR analyses.

DNA was extracted using the QIAamp tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). PCR amplification of the tick mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene was carried out as a quality control for the prepared DNA (8). Nested PCRs for detection of A. phagocytophilum that amplify a 546-bp product of the 16S rRNA gene were performed as described previously (6). In samples that were positive for A. phagocytophilum DNA, 1,297 bp of the groESL heat shock operon was amplified (30, 48). Amplification of the ankA gene of A. phagocytophilum (also termed ank) with published primers (32) was possible for only 15 out of 42 positive samples. When PCRs were carried out at low stringency, parts of the ankA genes of eight additional samples could be amplified. These PCR products were sequenced, and primers for the amplification of the complete open reading frame could be obtained (Table 1). In 1 of 42 samples, only the first half of the ankA gene was amplified with previously published primers (32). By the strategy described above, the second half of the gene could be amplified. Primers used for PCR and sequencing of the ankA gene are summarized in Table 1; the respective nucleotide sequences are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for amplification and sequencing of the ankA gene

| No. of ticks | First PCR

|

Nested PCR

|

Additional primers used for sequencinga | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primers used | Reference or source | Primers used | Reference or source | ||

| 15 of 42 | U7 + 1R1 | 32 | U8 + 1R7 | 32 | FvL ankU3 |

| U5 + 1R4 | 32 | FvL ankU1 | |||

| U3 + 1R2 | 32 | FvL ankU2 | |||

| 15 of 42 | 1F + 4R1 | 32 | 1F + 1R | 32 | FvL ank1 |

| 2F1 + 2R1 | 32 | FvL ank2 | |||

| 3F + 3R | 32 | FvL ank3 | |||

| 4F1 + 4R1 | 32 | ||||

| 15 of 42 | 4F2 + D2 | 32 | 4F3 + D1 | 32 | |

| 8 of 42 | U8 + 1Rmod | 32; this study | U8 + 1R7mod | 32; this study | |

| U5mod + 1R4mod | This study | ||||

| U3mod + 1R2mod | This study | U3 Seq1 | |||

| U3 Seq2 | |||||

| U3 Seq3 | |||||

| U3 Seq4 | |||||

| 8 of 42 | 1F + 4R1mod | 32; this study | 1Fmod2 + 1Rmod | This study | |

| 2F1 mod + 2R1mod | This study | ||||

| 8 of 42 | 1Fmod2 + D1 | This study; 32 | 3Fmod + D1 | 32; this study | 3Fmod Seq1 |

| 3Fmod Seq2 | |||||

| 3Fmod Seq3 | |||||

| 3Fmod Seq4 | |||||

| 3Fmod Seq5 | |||||

| 3Fmod Seq6 | |||||

| 8 of 42 | 4F2 + D2 | 32 | 4F3 + D1 | 32 | |

| 1 of 42 | U7 + 1R1 | 32 | U8 + 1R7 | 32 | FvL ankU3 |

| U5 + 1R4 | 32 | FvL ankU1 | |||

| U3 + 1R2 | 32 | FvL ankU2 | |||

| 1 of 42 | 1F + 4R1mod | 32; this study | 1F + 1R | 32 | |

| 2F1neu + 4Rneu | This study | 2F1neu Seq1 | |||

| 2F1neu Seq2 | |||||

| 2F1neu Seq3 | |||||

| 2F1neu Seq4 | |||||

| 4F1neu Seq1 | |||||

| 4F1neu Seq2 | |||||

| 4F1neu Seq3 | |||||

| 4F1neu Seq4 | |||||

| 4F1neu Seq5 | |||||

| 1 of 42 | 4F2neu + D1 | 32; this study | |||

Primers were designed for this study and are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Nucleotide sequences of primers used for amplification and sequencing of the ankA gene

| Primer | Nucleotide sequence |

|---|---|

| Amplification | |

| U5mod | GCA AGC ACG TGA GGC AGC G |

| U3mod | GCG TAT GGA TCA CGA GAA AA |

| 1Fmod2 | GTA TTC TGC AGT CTG CTC TTA G |

| 1Rmod | CTT AGT GCT TCA GCG GTC AG |

| 1R2mod | GCG TAG GAA ACT TAG AAC TA |

| 1R4mod | CAT ACT GCA CTG CAC TCA TCC |

| 1R7mod | ATA TCT GCT CCA TAC CAC TG |

| 2F1mod | CAC TGA AGT GGT TGC TGT AA |

| 2R1mod | GAA TAT AAA GCC TCA TGT AAC G |

| 2F1neu | CAA GAG ACA ACT CTG GCT TTT |

| 3Fmod | GCT GCA AGC CGC TCC ATT CT |

| 4F2neu | CAG AAG GAT TAC AGG GAG CA |

| 4R1mod | CTT TGA GGA GCT TCT GGT TG |

| 4Rneu | GGA TCC TGC TTT GCC TTT TC |

| Sequencing | |

| FvL ankU1 | CAC TCC GCT TCA TAT TGC TA |

| FvL ankU2 | ACT CCT GAG TCT GTT GTA AA |

| FvL ankU3 | TAA CAC ATC CTC TTT CAA CC |

| FvL ank1 | GAA GAA ATT ACA ACT CCT GAA |

| FvL ank2 | GCA GCT GCT AAT GGT GAC GG |

| FvL ank3 | TAT CAT CCT TGG GTA GTG G |

| U3 Seq1 | GCT CAG GTT CCC CAG AAG TA |

| U3 Seq2 | AAT TTT GGC TAT CAT TAG AAG AT |

| U3 Seq3 | GAA CAC CCT CAA TCA ACA TC |

| U3 Seq4 | CAT CTC CAG TGA CAG GTG TA |

| 2F1neu Seq1 | GGA TCT ATG GAT GAA CAA GG |

| 2F1neu Seq2 | ATT AAC AAG TGC CAG GTG TAA |

| 2F1neu Seq3 | CAG TAA TGA TTC TCC GCT TG |

| 2F1neu Seq4 | GTA TCA CCA GAA TGT TTC CT |

| 3Fmod Seq1 | CCA TTT GCT CTT TGC TGA GAA |

| 3Fmod Seq2 | CTG GGG CAA CAG CAT CAG T |

| 3Fmod Seq3 | CAC TGG AGA ATA AAG AAG TAG G |

| 3Fmod Seq4 | ATG CAA CAG TGA AAA AGG GTC |

| 3Fmod Seq5 | CTT TTT GAG AAG TAT CAC TC |

| 3Fmod Seq6 | GCT GAA GGT CTA GGA ACG CC |

| 4F1neu Seq1 | GTC AGC ATA GAT AGA TTC AGG |

| 4F1neu Seq2 | AGA AGA AAT AGA TTC CCA AGT A |

| 4F1neu Seq3 | GCC TAT CTA CGA GGA CAT TA |

| 4F1neu Seq4 | TAG AAG AGC GTG TCC AAG TA |

| 4F1neu Seq5 | TCT TTC TTC TTA ACC ACA GAT A |

PCRs for amplification of the ankA gene were carried out as follows: 2 to 5 μl of DNA was used as a template in a 50-μl reaction mixture containing 50 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 0.5 μM each primer, and 0.2 μl (1 U) of Taq DNA polymerase (Gibco BRL, Karlsruhe, Germany). The PCRs were performed in a Gene Amp PCR System 9700 (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) under the following cycling conditions: denaturation for 3 min at 94°C followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, the predicted melting temperature of the primers minus 4°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Final extension of the product was carried out at 72°C for 10 min. Nested amplifications used 1 μl of the primary PCR product as the template. DNA from A. phagocytophilum (E. equi MRK) was used as a positive control (kindly provided by J. Stephen Dumler, The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, Md.), and sterile H2O served as a negative control. To avoid contamination, the extraction of DNA, the preparation of the master mixes, and the PCR were performed in three separate rooms.

DNA sequencing and data analysis.

All PCR products were bidirectionally sequenced without prior subcloning by using the ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer and the Big Dye Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems). In the case of the 546-bp product of the 16S rRNA gene, sequencing was performed with the primers used for the PCR as well as with two other primers (342 f [CTA CGG GAG GCA GCA GT] and 356 r [TGC TGC CTC CCG TAG GA]). The groESL sequence was determined as described previously (11, 30, 48) together with primer FvL groESL (GGG AGA TGG AAC TAC TAC AT). For sequence analysis of the ankA gene, the same primers as those for the PCR were used (32), but complementation was achieved by use of additional sets of primers (Table 1). Sequences were edited and assembled with the SeqMan program (Lasergene package; DNAstar, Madison, Wis.). Alignments were performed using the PileUp program of the Wisconsin Package (version 10.2; Genetics Computer Group [GCG], Madison, Wis.). Percent identity and percent similarity were determined by the OldDistances program of the GCG package by using the length of the shorter sequence without gaps as the denominator. For amino acid sequence comparison, a BLOSUM62 matrix was applied. The GrowTree program of the GCG package was used for phylogenetic analyses, and phylograms were generated by the unweighted pair-group method using arithmetic averages (UPGMA).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rRNA gene sequence of sample D14 matches the previously reported sequence of the Ehrlichia sp. “Frankonia 1” (GenBank accession no. AF136713). The 16S rRNA gene sequences of samples G35 and G22 are identical to the previously described sequences of the Ehrlichia sp. “Frankonia 2” (GenBank accession no. AF136712) and the Ehrlichia sp. “Baden” (GenBank accession no. AF136714), respectively. The remaining 16S rRNA gene sequences received GenBank accession no. AY281771 to AY281809. GenBank accession numbers for the groESL and ankA sequences are AY281810 to AY281851 and AY282368 to AY282391, respectively.

RESULTS

In 46 of 1,022 I. ricinus ticks, the 16S rRNA gene-based nested PCR for detection of A. phagocytophilum yielded products of the correct size. Sequence analysis revealed that 42 (4.1%) ticks were infected with A. phagocytophilum. The infection rate was 4.3% (30 of 697) in adult females, 4.5% (10 of 223) in adult males, and 2.7% (2 of 73) in nymphs. The prevalences of infected ticks in Bavaria (4.1%; 30 of 733) and Baden-Württemberg (3.7%; 10 of 269) were comparable. One of 111 ticks removed from humans was infected (sample P80). Four hundred ninety-six base pairs (without primer sequences) of three samples were 99.80 to 100% identical to the 16S rRNA gene of Wolbachia pipientis (GenBank accession no. AJ306308). The sequenced 331 bp of another PCR product was 100% identical to the 16S rRNA gene of the Ehrlichia-like sp. “Schotti variant” (GenBank accession no. AF104680). The negative-control samples included in each PCR run did not yield amplification products.

16S rRNA gene sequences.

Sequence analysis of 497 bp (without primer sequences) of the 16S rRNA gene revealed seven sequence types of A. phagocytophilum infecting German ticks. The sequences were 99.20 to 100% identical to each other and 99.40 to 100% identical (one to three nucleotide exchanges) to the prototype sequence of A. phagocytophilum, which was originally derived from a patient with HGE (GenBank accession no. U02521). Sixteen sequences (samples G35, G55, I68, I121, I200, K71, K84, S16, W34, W37, W63, W98, W140, W229, W284, and X7) were 100% identical to a sequence previously obtained from German I. ricinus ticks (GenBank accession no. AF136712). Ten sequences (samples D12, D13, D14, D20, D21, D22a, I63, I145, I158, and X17) showed 100% identity to a sequence which was previously derived from I. ricinus ticks in Sweden (GenBank accession no. AJ242784) and Germany (GenBank accession no. AF136713) and from roe deer in Switzerland (GenBank accession no. AF384212) and Slovenia (GenBank accession no. AF481850). In six sequences (samples G22, G24, G26, I20, J1, and SG3), 100% identity to another sequence from I. ricinus ticks in Sweden (GenBank accession no. AJ242783) and in Germany (GenBank accession no. AF136714) was found. An A. phagocytophilum strain with the latter sequence has been implicated in a case of granulocytic ehrlichiosis in a roe deer in Norway (46). One sequence (sample W271) was 100% identical to the prototype sequence of A. phagocytophilum (GenBank accession no. U02521). Another sequence (sample N6) showed 100% identity to a sequence from red deer in Slovenia (GenBank accession no. AF481852) and from I. ricinus ticks in the United Kingdom (GenBank accession no. AY149637).

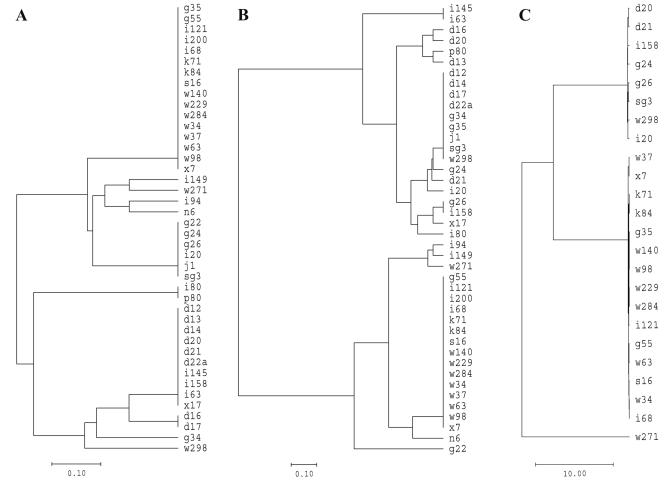

Three sequences (samples I80, P80, and W298) had nucleotide exchanges at two to three positions compared to the prototype sequence of A. phagocytophilum (GenBank accession no. U02521) and were also different from any other known A. phagocytophilum sequence. Two of them were identical to each other. The analysis of five sequences yielded one double peak in the respective chromatograms. These peaks occurred mainly at positions known for nucleotide exchanges, suggesting that one individual tick might harbor more than one A. phagocytophilum variant. Apart from these double peaks, two sequences (samples I94 and I149) were identical to the prototype sequence of A. phagocytophilum (GenBank accession no. U02521), and three (samples D16, D17, and G34) matched the sequence from I. ricinus ticks in Sweden and Germany and from roe deer in Switzerland and Slovenia described above (GenBank accession no. AJ242784, AF136713, AF384212, and AF481850). The phylogram presented in Fig. 1A shows the relationships of the 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained.

FIG. 1.

Phylograms showing the relationships of the 16S rRNA gene (A), groESL (B), and ankA (C) nucleotide sequences. Scale bars indicate substitutions per 100 residues.

groESL sequences.

A total of 1,256 bp (without primer sequences) of the groESL heat shock operon was analyzed for the 42 ticks that were infected with A. phagocytophilum. The sequences were 98.01 to 100% identical to each other. Although the majority of these sequences showed the highest degree of identity to sequences derived from roe deer, red deer, and I. ricinus ticks in Europe, 98.41 to 100% identities to sequences from HGE patients and horses with EGE in North America and Europe were also found.

The majority of the groESL sequences segregated into two main sequence types. The first type, represented by 15 sequences (samples G55, I68, I121, I200, K71, K84, S16, W34, W37, W63, W98, W140, W229, W284, and X7), showed 99.92% identity to sequences from red deer (GenBank accession no. AF478562) and roe deer (GenBank accession no. AF478558) in Slovenia. The second type, consisting of nine sequences (samples D12, D14, D17, D22a, G34, G35, J1, SG3, and W298), was 100% identical to a sequence from roe deer in Switzerland (GenBank accession no. AF383226) and Slovenia (GenBank accession no. AF478551). The remaining 18 sequences showed 99.68 to 100% identities to various groESL sequences deposited in GenBank. One of them (sample N6) was 100% identical to a sequence from a Slovenian HGE patient (GenBank accession no. AF033101) and a German horse with EGE (GenBank accession no. AF482760), but in this sample a 16S rRNA gene sequence variant was found. The sample with the 16S rRNA gene prototype sequence (sample W271) showed 100% identity to the groESL sequence from a Scottish goat (GenBank accession no. U96729), an animal known to be susceptible to A. phagocytophilum. In six sequences, one to two double peaks were detected in each of the chromatograms. They occurred mainly at positions where nucleotide exchanges were observed and in samples that also had double peaks in their 16S rRNA gene sequences. Double peaks were restricted to the third position of the codons and did not lead to amino acid exchanges. The phylogram in Fig. 1B shows the relationships of the groESL nucleotide sequences obtained.

The nested PCR we used targets the spacer region between the groES and groEL genes and the first part of the groEL gene. Hence, the first 402 amino acids of the GroEL sequences were analyzed. Only one amino acid exchange was observed (at position 242); all other nucleotide changes were silent. Twenty-two sequences had an alanine at that position, and 20 sequences had a serine.

ankA sequences.

In 24 of 42 samples of DNA from infected ticks, the ankA gene could be amplified by PCR as described in Material and Methods. Sequencing of the total open reading frames revealed three distinct sequence types. The first sequence type comprised 15 sequences (samples G35, G55, I68, I121, K71, K84, S16, W34, W37, W63, W98, W140, W229, W284, and X7) that were closely related to known ankA sequences and were 97.67 to 100% identical to each other at the nucleotide level. At the amino acid level, the percentage of similarity was 97.16 to 100% (Table 3). Two of these sequences (samples I68 and I121) showed 99.45 and 99.40% identities, respectively, to a sequence from a Swedish HGE patient (GenBank accession no. AF100888) and from a German horse with EGE (GenBank accession no. AF482759). In 11 sequences (samples G35, G55, K71, K84, W34, W63, W98, W140, W229, W284, and S16), an as yet undescribed 75-bp (25-amino-acid) direct repeat, starting at nucleotide position 2145, was found. Except for that repeat, these sequences were again 99.37 to 99.48% identical to the sequence from the Swedish HGE patient and the German horse with EGE. In two sequences (samples X7 and W37), another novel, 96-bp (32-amino-acid) direct repeat structure beginning at nucleotide position 2775 was detected. It spans the same region as a previously described 81-bp direct repeat (32). Except for the direct repeat structure, these two sequences were 99.49 and 99.52% identical to sequences from two Slovenian HGE patients (GenBank accession no. AF100886 and AF100887, respectively). All 15 samples representing the first ankA sequence type showed the same 16S rRNA gene sequence variant which was previously obtained from German I. ricinus ticks (GenBank accession no. AF136712). The same was true with respect to the groESL sequences, since all, except sample G35, harbored the same groESL sequence, which was 99.92% identical to sequences from Slovenian red deer and roe deer (GenBank accession no. AF478562 and AF478558, respectively).

TABLE 3.

Identities of ankA nucleotide sequences and similarities of deduced amino acid sequences

| Sample | % Identity of ankA nucleotide sequences (roman) and % similarity of deduced amino acid sequences (italics) for the indicated samples

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D20 | D21 | G24 | G26 | SG3 | I20 | W298 | I158 | W37 | X7 | K71a | G35b | W229c | G55 | W63 | S16 | W34 | I121 | I68 | W271 | |

| D20 | 99.81 | 99.78 | 99.70 | 99.54 | 99.43 | 99.43 | 99.78 | 82.14 | 82.14 | 81.54 | 81.60 | 81.57 | 81.57 | 81.57 | 81.52 | 81.49 | 82.18 | 82.18 | 74.42 | |

| D21 | 99.75 | 99.73 | 99.73 | 99.57 | 99.51 | 99.57 | 99.70 | 82.06 | 82.06 | 81.46 | 81.52 | 81.49 | 81.49 | 81.49 | 81.43 | 81.41 | 82.10 | 82.10 | 74.34 | |

| G24 | 99.42 | 99.34 | 99.86 | 99.73 | 99.62 | 99.62 | 99.84 | 82.17 | 82.17 | 81.57 | 81.62 | 81.60 | 81.60 | 81.60 | 81.54 | 81.52 | 82.21 | 82.21 | 74.42 | |

| G26 | 99.59 | 99.67 | 99.59 | 99.81 | 99.70 | 99.76 | 99.78 | 82.11 | 82.11 | 81.52 | 81.57 | 81.54 | 81.54 | 81.54 | 81.49 | 81.46 | 82.15 | 82.15 | 74.32 | |

| SG3 | 99.51 | 99.59 | 99.59 | 99.67 | 99.68 | 99.62 | 99.62 | 82.06 | 82.06 | 81.46 | 81.52 | 81.49 | 81.49 | 81.49 | 81.43 | 81.41 | 82.10 | 82.10 | 74.26 | |

| I20 | 99.18 | 99.42 | 99.26 | 99.34 | 99.51 | 99.68 | 99.57 | 81.82 | 81.82 | 81.22 | 81.28 | 81.25 | 81.25 | 81.25 | 81.20 | 81.17 | 81.88 | 81.88 | 74.03 | |

| W298 | 99.18 | 99.42 | 99.26 | 99.51 | 99.34 | 99.51 | 99.70 | 81.87 | 81.87 | 81.27 | 81.33 | 81.30 | 81.30 | 81.30 | 81.24 | 81.22 | 81.91 | 81.91 | 74.15 | |

| I158 | 99.50 | 99.42 | 99.42 | 99.50 | 99.34 | 99.26 | 99.50 | 82.13 | 82.13 | 81.54 | 81.59 | 81.56 | 81.56 | 81.56 | 81.51 | 81.48 | 81.91 | 81.91 | 74.37 | |

| W37 | 78.37 | 78.12 | 78.04 | 78.12 | 78.21 | 77.80 | 77.88 | 78.22 | 99.97 | 97.73 | 97.67 | 97.70 | 97.70 | 97.70 | 97.73 | 97.70 | 99.67 | 99.70 | 81.43 | |

| X7 | 78.37 | 78.12 | 78.04 | 78.12 | 78.21 | 77.80 | 77.88 | 78.22 | 99.92 | 97.70 | 97.70 | 97.67 | 97.73 | 97.73 | 97.70 | 97.67 | 99.65 | 99.67 | 81.46 | |

| K71a | 77.14 | 76.89 | 76.81 | 76.89 | 77.14 | 76.56 | 76.64 | 76.98 | 97.32 | 97.24 | 99.87 | 99.89 | 99.81 | 99.81 | 99.87 | 99.84 | 99.89 | 99.84 | 81.01 | |

| G35b | 77.22 | 76.97 | 76.89 | 76.97 | 77.06 | 76.64 | 76.73 | 77.06 | 97.16 | 97.24 | 99.59 | 99.97 | 99.89 | 99.84 | 99.79 | 99.76 | 99.89 | 99.78 | 81.01 | |

| W229c | 77.22 | 76.97 | 76.89 | 76.97 | 77.06 | 76.64 | 76.73 | 77.06 | 97.24 | 97.16 | 99.68 | 99.92 | 99.87 | 99.81 | 99.81 | 99.79 | 99.92 | 99.81 | 80.98 | |

| G55 | 77.22 | 76.97 | 76.89 | 76.97 | 77.06 | 76.64 | 76.73 | 77.06 | 97.24 | 97.32 | 99.43 | 99.68 | 99.59 | 99.95 | 99.84 | 99.87 | 99.84 | 99.89 | 81.06 | |

| W63 | 77.30 | 77.06 | 76.97 | 77.06 | 77.06 | 76.73 | 76.81 | 77.15 | 97.24 | 97.32 | 99.43 | 99.51 | 99.43 | 99.84 | 99.84 | 99.92 | 99.78 | 99.95 | 81.06 | |

| S16 | 77.22 | 76.97 | 76.89 | 76.97 | 77.06 | 76.64 | 76.73 | 77.06 | 97.40 | 97.32 | 99.68 | 99.43 | 99.51 | 99.59 | 99.59 | 99.92 | 99.81 | 99.92 | 81.09 | |

| W34 | 77.22 | 76.97 | 76.89 | 76.97 | 77.06 | 76.64 | 76.73 | 77.06 | 97.32 | 97.24 | 99.59 | 99.35 | 99.43 | 99.68 | 99.84 | 99.76 | 99.78 | 100 | 81.06 | |

| I121 | 77.78 | 77.53 | 77.45 | 77.53 | 77.61 | 77.20 | 77.28 | 77.36 | 99.25 | 99.25 | 99.75 | 99.83 | 99.83 | 99.67 | 99.50 | 99.59 | 99.50 | 99.78 | 82.67 | |

| I68 | 77.86 | 77.61 | 77.53 | 77.61 | 77.69 | 77.28 | 77.36 | 77.45 | 99.34 | 99.25 | 99.59 | 99.42 | 99.50 | 99.75 | 99.92 | 99.75 | 100 | 99.50 | 82.72 | |

| W271 | 70.64 | 70.48 | 70.31 | 70.39 | 70.48 | 70.23 | 70.39 | 70.54 | 79.10 | 78.61 | 78.07 | 78.07 | 78.07 | 78.15 | 78.15 | 78.23 | 78.15 | 79.68 | 79.77 | |

K71 also represents K84.

G35 also represents W140 and W98.

W229 also represents W284.

The second ankA sequence type was detected in eight samples (D20, D21, G24, G26, I20, I158, SG3, and W298) and did not match with known ankA sequences over the entire open reading frame. They were 99.43 to 99.86% identical to each other on the nucleotide level and 99.18 to 99.75% similar to each other on the amino acid level (Table 3). The identity to sequences of the first sequence type was 81.17 to 82.21% on the nucleotide level but was limited to 76.56 to 78.37% on the amino acid level (Table 3). One sequence (sample I158) showed an unique 12-bp deletion at nucleotide position 1102. In three sequences (samples G24, G26, and I158) that showed ambiguous nucleotides in their groESL sequences, as many as six double peaks in the ankA chromatograms were detected. Four of 12 of these ambiguous nucleotides would lead to an amino acid exchange. This indicates that one tick might harbor more than one A. phagocytophilum variant, since BLAST searches in the A. phagocytophilum genome (http://www.tigr.org/tdb/mdb/mdbinprogress.html) revealed only one copy of each of these genes. The infection of ticks (31, 43), rodents (28), and sheep (47) with more than one A. phagocytophilum variant has also been noted by others.

The third sequence type was displayed only by one sequence (sample W271). The first (nucleotides 1 to 1667) and last (nucleotides 3543 to 3764) parts of this sequence were 99.28 and 91.89% identical, respectively, to sequences from HGE patients in Europe and from a German horse with EGE (GenBank accession no. AF100886, AF100887, AF100888, and AF482759), whereas in the middle part the identity to known sequences was limited to about 60%. At the nucleotide level, the third sequence type was 80.98 to 82.72% and 74.03 to 74.42% identical to the first and the second ankA sequence types described above, respectively. At the amino acid level, similarities of 78.07 to 79.77% to the first ankA sequence type and 70.23 to 70.64% to the second ankA sequence type were found (Table 3). Although sample W271 showed the unique ankA sequence described, its 16S rRNA gene and groESL sequences were 100% identical to the prototype sequence of A. phagocytophilum (GenBank accession no. U02521) and to a sequence from a Scottish goat (GenBank accession no. U96729), respectively.

The phylogram presented in Fig. 1C shows the relationships of the ankA nucleotide sequences obtained. The same clusters (except for sample G35) were achieved by using groESL sequences for the construction of the phylograms (Fig. 1B). The origin of the tick (Bavaria or Baden-Württemberg) had no obvious influence on the position of the respective sequence in the phylograms.

DISCUSSION

Using a large collection of I. ricinus ticks, the present study not only extends previous reports on the infection rate of ticks with A. phagocytophilum in Germany (6, 17, 21) but also provides a detailed phylogenetic analysis of A. phagocytophilum in Europe. Most importantly, the data demonstrate an unexpected and marked nucleotide polymorphism of the ankA gene. Compared to the infection rates observed in other European countries (about 1 to 30%), the prevalence of A. phagocytophilum infection in German ticks lies in the middle of the range of reported values (1, 3, 13, 14, 20, 24, 28, 33-35, 38, 40, 43, 54). The amplification of the 16S rRNA genes of W. pipientis and of the Ehrlichia-like sp. Schotti variant with primers thought to be specific for A. phagocytophilum underlines the necessity to confirm the specificity of the PCR products by sequence analysis. Amplification of related species has also been reported for other primer combinations (24, 27).

The number of proven cases of acute HGE in Europe is low compared to that in the United States. Nevertheless, in several European countries including Germany, significant rates of infection of I. ricinus ticks with A. phagocytophilum have been reported, but no cases of HGE have been diagnosed to date (1, 3, 13, 14, 28, 33, 35, 40). It is unlikely that ticks infected with A. phagocytophilum do not bite humans, because the same species of ticks most successfully transmits Borrelia burgdorferi in these countries, and ticks coinfected with A. phagocytophilum and B. burgdorferi have been detected repeatedly (6, 13, 14, 17, 20, 28, 43). Furthermore, in the present study, one tick that was removed from a human was found to be infected with A. phagocytophilum (sample P80).

Differences between European and North American strains of A. phagocytophilum have been claimed, because in European HGE patients the clinical course appears to be less severe and morulae in peripheral blood neutrophils are uncommon (9). However, at the moment the number of cases in Europe is still too small for a definite conclusion. We therefore characterized three different genes (the 16S rRNA gene, groESL, and ankA) of A. phagocytophilum strains infecting German I. ricinus ticks to test whether these strains differ from strains known to be pathogenic in other European countries or in the United States. The results clearly show that almost half of the analyzed A. phagocytophilum strains in German I. ricinus ticks are closely related by sequence identity to strains that caused granulocytic ehrlichiosis in humans or animals in other European countries and in the United States as well as to a strain that was found in a horse with EGE in Germany (53). Therefore, German I. ricinus ticks most likely harbor A. phagocytophilum strains that are able to elicit granulocytic ehrlichiosis in humans also.

Sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA genes of 42 samples revealed that only 1 sequence was 100% identical to the prototype sequence of A. phagocytophilum (GenBank accession no. U02521). All other sequences, although highly related to the prototype sequence, showed one to three nucleotide exchanges. The impact of such A. phagocytophilum 16S rRNA gene variants has been a matter of debate. Apart from two HGE patients in California, who were infected with strains that had the same 16S rRNA gene sequences as isolates from sick horses (19), all other cases of HGE were, to our knowledge, caused by strains with the 16S rRNA gene prototype sequence. Otherwise, A. phagocytophilum 16S rRNA gene variants have been shown to elicit diseases in horses (11), in roe deer (46), and in sheep (47).

In our positive samples we also sequenced the groESL gene, since the 16S rRNA gene is too conserved to allow for the analysis of genetic heterogeneity. The highest degree of identity found was to A. phagocytophilum sequences from roe deer, red deer, and I. ricinus ticks in Europe. Roe and red deer have been suggested to be one of the reservoirs for A. phagocytophilum in Europe (2, 29, 36), although it is not clear whether the variants infecting these animals can cause disease in humans. Nevertheless, the groESL sequences found in our study showed 98.41 to 100% identities to sequences from HGE patients and horses with EGE in North America and Europe. Two main types of groESL sequences were detected. The latter result is in agreement with the findings of Petrovec et al., who reported two genetic lineages of groESL sequences, one infecting mainly red deer and one infecting roe deer (36).

To further characterize A. phagocytophilum variants infecting German ticks, we chose to analyze the ankA gene, since it is known to be immunodominant (10, 45) and its expression may be subject to immunoselection. The function of AnkA remains unknown to date, but a role in protein-protein interactions and a possible impact on host cell gene transcription have been suggested (10, 32, 45). In a previous pioneering sequence analysis, the identities of the ankA genes of 14 A. phagocytophilum specimens from America and Europe were generally very high, but three different clades of sequences could be clearly identified (32). In our study we observed a high and so far unrecognized diversity of the ankA gene sequences. Except for sample G35, the groESL and ankA sequences clustered in the same way, although the separation into three sequence types was much more distinct in the case of the ankA sequences. It appears that the ankA gene is a valuable tool for describing genetic heterogeneity in A. phagocytophilum. It is possible that the strains that carry the newly described ankA sequences are nonpathogenic, since these sequences have never been detected in cases of HGE or granulocytic ehrlichiosis of animals. Alternatively, these new ankA sequence variants might simply reflect the still-limited sequence information on the ankA gene. Another explanation is the existence of A. phagocytophilum strains that are adapted to a certain animal reservoir and do not cause disease in all hosts to the same extent. This hypothesis is in line with the limited efficacy of some of the cross-infection experiments with A. phagocytophilum strains of human, equine, bovine, and ovine origins (18, 22, 39, 41, 42, 44). Differences in antigenicity and virulence have already been suggested between A. phagocytophilum strains (47, 49, 50).

In addition to the A. phagocytophilum strains carrying the newly described ankA sequences, we also found strains with identities as high as 99.52% to ankA sequences from European patients with HGE and from a German horse with EGE. All these strains carried the same 16S rRNA gene variant. Thus, a defined 16S rRNA gene variant did not allow one to predict a certain ankA sequence different from known sequences. Conversely, 100% identity in the 16S rRNA or groESL gene to sequences from patients with HGE was not associated with an ankA sequence with high identity to known ankA sequences. Therefore, the sequence variability of one gene is not sufficient to determine the genetic diversity of a certain strain. In the future, it will be necessary to cultivate some of the A. phagocytophilum strains and to compare them in animal models in order to unravel the biological significance of the observed genetic diversities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the German Ministry for Education and Research, the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research of the Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen (project A14), and the German Research Foundation (SFB263 project A5).

We are grateful to J. Stephen Dumler (The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions) for providing the E. equi MRK strain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alberdi, M. P., A. R. Walker, E. A. Paxton, and K. J. Sumption. 1998. Natural prevalence of infection with Ehrlichia (Cytoecetes) phagocytophila of Ixodes ricinus ticks in Scotland. Vet. Parasitol. 78:203-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberdi, M. P., A. R. Walker, and K. A. Urquhart. 2000. Field evidence that roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) are a natural host for Ehrlichia phagocytophila. Epidemiol. Infect. 124:315-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alekseev, A. N., H. V. Dubinina, I. Van De Pol, and L. M. Schouls. 2001. Identification of Ehrlichia spp. and Borrelia burgdorferi in Ixodes ticks in the Baltic regions of Russia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2237-2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnez, M., M. Petrovec, S. Lotric-Furlan, T. Avsic Zupanc, and F. Strle. 2001. First European pediatric case of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4591-4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakken, J. S., and J. S. Dumler. 2000. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 31:554-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumgarten, B. U., M. Röllinghoff, and C. Bogdan. 1999. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi and granulocytic and monocytic ehrlichiae in Ixodes ricinus ticks from Southern Germany. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3448-3451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bjöersdorff, A., B. Wittesjö, J. Berglund, R. F. Massung, and I. Eliasson. 2002. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis as a common cause of tick-associated fever in southeast Sweden: report from a prospective clinical study. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 34:187-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Black, W. C., and J. Piesman. 1994. Phylogeny of hard- and soft-tick taxa (Acari: Ixodida) based on mitochondrial 16S rDNA sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:10034-10038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanco, J. R., and J. A. Oteo. 2002. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Europe. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 8:763-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caturegli, P., K. M. Asanovich, J. J. Walls, J. S. Bakken, J. E. Madigan, V. L. Popov, and J. S. Dumler. 2000. ankA: an Ehrlichia phagocytophila group gene encoding a cytoplasmic protein antigen with ankyrin repeats. Infect. Immun. 68:5277-5283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chae, J.-S., J. E. Foley, J. S. Dumler, and J. E. Madigan. 2000. Comparison of the nucleotide sequences of 16S rRNA, 444 Ep-ank, and groESL heat shock operon genes in naturally occurring Ehrlichia equi and human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent isolates from Northern California. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1364-1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, S.-M., J. S. Dumler, J. S. Bakken, and D. H. Walker. 1994. Identification of a granulocytotropic Ehrlichia species as the etiologic agent of human disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:589-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christova, I., L. Schouls, I. Van De Pol, J. Park, S. Panayotov, V. Lefterova, T. Kantardjiev, and J. S. Dumler. 2001. High prevalence of granulocytic ehrlichiae and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Ixodes ricinus ticks from Bulgaria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4172-4174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cinco, M., D. Padovan, R. Murgia, M. Maroli, L. Frusteri, M. Heldtander, K.-E. Johansson, and E. O. Engvall. 1997. Coexistence of Ehrlichia phagocytophila and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Ixodes ricinus ticks from Italy as determined by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:3365-3366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dumler, J. S., A. F. Barbet, C. P. J. Bekker, G. A. Dasch, G. H. Palmer, S. C. Ray, Y. Rikihisa, and F. R. Rurangirwa. 2001. Reorganization of genera in the families Rickettsiaceae and Anaplasmataceae in the order Rickettsiales: unification of some species of Ehrlichia with Anaplasma, Cowdria with Ehrlichia and Ehrlichia with Neorickettsia, descriptions of six new species combinations and designation of Ehrlichia equi and ′HGE agent' as subjective synonyms of Ehrlichia phagocytophila. Int. J. Syst. E vol. Microbiol. 51:2145-2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fingerle, V., J. L. Goodmann, R. C. Johnson, T. J. Kurtti, U. G. Munderloh, and B. Wilske. 1997. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Southern Germany: increased seroprevalence in high-risk groups. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:3244-3247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fingerle, V., U. G. Munderloh, G. Liegl, and B. Wilske. 1999. Coexistence of ehrlichiae of the phagocytophila group with Borrelia burgdorferi in Ixodes ricinus from Southern Germany. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 188:145-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foggie, A. 1951. Studies on the infectious agent of tick-borne fever in sheep. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 63:1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foley, J. E., L. Crawford-Miksza, J. S. Dumler, C. Glaser, J.-S. Chae, E. Yeh, D. Schnurr, R. Hood, W. Hunter, and J. E. Madigan. 1999. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Northern California: two case descriptions with genetic analysis of the ehrlichiae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:388-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grzeszczuk, A., J. Stanczak, and B. Kubica-Biernat. 2002. Serological and molecular evidence of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis focus in the Bialowieza Primeval Forest (Puszcza Bialowieska), northeastern Poland. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 21:6-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hildebrandt, A., K.-H. Schmidt, V. Fingerle, B. Wilske, and E. Straube. 2002. Prevalence of granulocytic ehrlichiae in Ixodes ricinus ticks in middle Germany (Thuringia) detected by PCR and sequencing of a 16S ribosomal DNA fragment. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 211:225-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudson, J. R. 1950. The recognition of tick-borne fever as a disease of cattle. Br. Vet. J. 106:3-17. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunfeld, K.-P., and V. Brade. 1999. Prevalence of antibodies against the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent in Lyme borreliosis patients from Germany. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 18:221-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenkins, A., B. E. Kristiansen, A. G. Allum, R. K. Aakre, L. Strand, E. J. Kleveland, I. Van De Pol, and L. Schouls. 2001. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and Ehrlichia spp. in Ixodes ticks from southern Norway. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3666-3671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karlsson, U., A. Bjöersdorff, R. F. Massung, and B. Christensson. 2001. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis—a clinical case in Scandinavia. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 33:73-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kristiansen, B. E., A. Jenkins, Y. Tveten, B. Karsten, O. Line, and A. Bjöersdorff. 2001. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Norway. Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforen. 121:805-806. (Article in Norwegian; summary in English.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Little, S. E., J. E. Dawson, J. M. Lockhart, D. E. Stallknecht, C. K. Warner, and W. R. Davidson. 1997. Development and use of specific polymerase reaction for the detection of an organism resembling Ehrlichia sp. in white-tailed deer. J. Wildl. Dis. 33:246-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liz, J. S., L. Anderes, J. W. Sumner, R. F. Massung, L. Gern, B. Rutti, and M. Brossard. 2000. PCR detection of granulocytic ehrlichiae in Ixodes ricinus ticks and wild small mammals in western Switzerland. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1002-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liz, J. S., J. W. Sumner, K. Pfister, and M. Brossard. 2002. PCR detection and serological evidence of granulocytic ehrlichial infection in roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) and chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra). J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:892-897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lotric-Furlan, S., M. Petrovec, T. Avsic Zupanc, W. L. Nicholson, J. W. Sumner, J. E. Childs, and F. Strle. 1998. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Europe: clinical and laboratory findings in four patients from Slovenia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:424-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Massung, R. F., M. J. Mauel, J. H. Owens, N. Allan, J. W. Courtney, K. C. I. Stafford, and T. N. Mather. 2002. Genetic variants of Ehrlichia phagocytophila, Rhode Island and Connecticut. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:467-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Massung, R. F., J. H. Owens, D. Ross, K. D. Reed, M. Petrovec, A. Bjöersdorff, R. T. Coughlin, G. A. Beltz, and C. I. Murphy. 2000. Sequence analysis of the ank gene of granulocytic ehrlichiae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2917-2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogden, N. H., K. Bown, B. K. Horrocks, Z. Woldehiwet, and M. Bennett. 1998. Granulocytic ehrlichia infection in ixodid ticks and mammals in woodlands and uplands of the U.K. Med. Vet. Entomol. 12:423-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oteo, J. A., H. Gil, M. Barral, A. Perez, S. Jimenez, J. R. Blanco, V. Martinez de Artola, A. Garcia-Perez, and R. A. Juste. 2001. Presence of granulocytic ehrlichia in ticks and serological evidence of human infection in La Rioja, Spain. Epidemiol. Infect. 127:353-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parola, P., L. Beati, M. Cambon, P. Brouqui, and D. Raoult. 1998. Ehrlichial DNA amplified from Ixodes ricinus (Acari: Ixodidae) in France. J. Med. Entomol. 35:180-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petrovec, M., A. Bidovec, J. W. Sumner, W. L. Nicholson, J. E. Childs, and T. Avsic Zupanc. 2002. Infection with Anaplasma phagocytophila in cervids from Slovenia: evidence of two genotypic lineages. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 114:641-647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petrovec, M., S. Lotric-Furlan, T. Avsic Zupanc, F. Strle, P. Brouqui, V. Roux, and J. S. Dumler. 1997. Human disease in Europe caused by a granulocytic Ehrlichia species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1556-1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petrovec, M., J. W. Sumner, W. L. Nicholson, J. E. Childs, F. Strle, J. Barlic, S. Lotric-Furlan, and T. Avsic Zupanc. 1999. Identity of ehrlichial DNA sequences derived from Ixodes ricinus ticks with those obtained from patients with human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Slovenia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:209-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pusterla, N., R. J. Anderson, J. K. House, J. B. Pusterla, E. DeRock, and J. E. Madigan. 2001. Susceptibility of cattle to infection with Ehrlichia equi and the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 218:1160-1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pusterla, N., C. M. Leutenegger, J. B. Huder, R. Weber, U. Braun, and H. Lutz. 1999. Evidence of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Switzerland. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1332-1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pusterla, N., H. Lutz, and U. Braun. 1998. Experimental infection of four horses with Ehrlichia phagocytophila. Vet. Rec. 143:303-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pusterla, N., J. B. Pusterla, U. Braun, and H. Lutz. 1999. Experimental cross-infections with Ehrlichia phagocytophila and human graunlocytic ehrlichia-like agent in cows and horses. Vet. Rec. 145:311-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schouls, L. M., I. Van De Pol, S. G. Rijpkema, and C. S. Schot. 1999. Detection and identification of Ehrlichia, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, and Bartonella species in Dutch Ixodes ricinus ticks. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2215-2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stannard, A. A., D. H. Gribble, and R. S. Smith. 1969. Equine ehrlichiosis: a disease with similarities to tick-borne fever and bovine petechial fever. Vet. Rec. 84:149-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Storey, J. R., L. A. Doros-Richert, C. Gingrich-Baker, K. Munroe, T. N. Mather, R. T. Coughlin, G. A. Beltz, and C. I. Murphy. 1998. Molecular cloning and sequencing of three granulocytic Ehrlichia genes encoding high-molecular-weight immunoreactive proteins. Infect. Immun. 66:1356-1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stuen, S., E. Olsson Engvall, I. Van De Pol, and L. Schouls. 2001. Granulocytic ehrlichiosis in a roe deer calf in Norway. J. Wildl. Dis. 37:614-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stuen, S., I. Van De Pol, K. Bergström, and L. Schouls. 2002. Identification of Anaplasma phagocytophila (formerly Ehrlichia phagocytophila) variants in blood from sheep in Norway. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3192-3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sumner, J. W., W. L. Nicholson, and R. F. Massung. 1997. PCR amplification and comparison of nucleotide sequences from the groESL heat shock operon of Ehrlichia species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2087-2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tuomi, J. 1967. Experimental studies on bovine tick-borne fever. 2. Differences in virulence of strains in cattle and sheep. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 70:577-589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tuomi, J. 1967. Experimental studies on bovine tick-borne fever. 3. Immunological strain differences. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 71:89-100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tylewska-Wierzbanowska, S., T. Chmielewski, M. Kondrusik, T. Hermanowska-Szpakowicz, W. Sawicki, and K. Sulek. 2001. First case of acute human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Poland. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 20:196-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Dobbenburgh, A., A. P. Dam, and E. Fikrig. 1999. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in western Europe. N. Engl. J. Med. 340:1214-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.von Loewenich, F. D., G. Stumpf, B. U. Baumgarten, M. Röllinghoff, J. S. Dumler, and C. Bogdan. 2003. A case of equine granulocytic ehrlichiosis provides molecular evidence for the presence of pathogenic Anaplasma phagocytophilum (HGE agent) in Germany. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 22:303-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.von Stedingk, L. V., M. Gürtelschmid, H. S. Hanson, R. Gustafson, L. Dotevall, E. Olsson, and M. Granström. 1997. The human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) agent in Swedish ticks. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 3:573-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]