Abstract

Understanding fidelity — the faithful replication or repair of DNA by polymerases — requires tracking of structural and energetic changes involved, including the elusive transient intermediates, for nucleotide incorporation at the template/primer DNA junction. We report using path sampling simulations and a reaction network model strikingly different transition states in DNA pol β's conformational closing for correct dCTP versus incorrect dATP incoming nucleotide opposite a template G. The cascade of transition states leads to differing active-site assembly processes toward the “two-metal-ion catalysis” geometry. We demonstrate that these context-specific pathways imply different selection processes: while active site assembly occurs more rapidly with the correct nucleotide and leads to primer extension, the enzyme remains open longer, has a more transient closed state, and forms product more slowly when an incorrect nucleotide is present. Our results also suggest that the rate-limiting step in pol β's conformational closing is not identical with that for overall nucleotide insertion and that the rate-limiting step in the overall nucleotide incorporation process for matched as well as mismatched systems occurs after the closing conformational change.

Introduction

The delicate interplay between DNA damage and repair is crucial to the integrity of our genome and has immense biomedical repercussions to various cancers, neurological aberrations, and the process of premature aging. DNA polymerases are central to these functions because of their role in replication as well as excision repair pathways [1]. The eukaryotic DNA repair enzyme, polymerase β of the X-family, with thumb, palm, and fingers subdomains, binds to DNA and fills single-stranded gaps in DNA with moderate accuracy (‘fidelity’). X-ray crystallography has provided exquisite views of the polymerase frozen-in-action: closed (active) and open (inactive) forms of the enzyme related by a large subdomain motion (∼ 6Å) of the thumb [2]. By transitioning between the inactive and active forms, the enzyme recruits a nucleotide unit (dNTP, 2′-deoxyribonucleoside 5′-triphosphate) complementary to the template base (e.g., C opposite G) about 1000 times more often than the incorrect unit (e.g., A opposite G) [3-6]; each such cycle adds a nucleotide unit to the primer strand. This ‘induced-fit’ mechanism in which the correct incoming base triggers the requisite conformational change, while an incorrect unit hampers the process, is thus crucial to our understanding of pol β's activity.

The temporal bridge connecting the crystal anchors is not completely resolved by kinetic studies of pol β [7,8]. This bridge could reveal mechanistic details of the pol β reaction pathway, such as key slow motions and their significance to catalytic efficiency and fidelity associated with nucleotide insertion. Prior simulations using standard dynamics techniques have: suggested that key residues in the enzyme active site (e.g., Phe272, Arg258) exhibit subtle conformational rearrangements during the thumb's subdomain motion [9-12] and incorrect nucleotide incorporations [10]; rationalized observations for pol β mutants [13]; dissected the roles of both the nucleotide-binding as well as catalytic Mg2+ ions [14]; and delineated key transition-state regions and the associated cooperative dynamics in DNA pol β's closing [15]. Numerous experiments on pol β mutants [16] also reveal effects of localized mutations (Y265H, Y271F, Y271H, G274P, D276V, N279A, N279L, R283A, R283K, R283L) on the enzyme's efficiency and fidelity.

Building on knowledge accumulated from these prior modeling and experimental studies, we report here detailed structural and energetic characterization of transient intermediates along the closing pathway of a correct (G:C) versus incorrect (G:A) nucleotide incorporation before the chemical reaction of primer extension. This comparison in atomic detail is made possible by an application to biomolecules [15] of the transition path sampling method [17] coupled to an efficient method to compute reaction free energy [18] and a network model for reaction rates [19]. All these components have been validated for biomolecular applications, though the well-appreciated force-field approximations are relevant to all large-scale simulations. Extensive prior modeling, however, indicates that simulations can offer important insights to link structure-function relationship. Here, our analyses reveal the disparate barriers and active-site assembly processes that guide the enzyme's conformational change and thereby serve to help discriminate between error-free and error-prone repair processes. Specifically, the active site of the closed mismatch complex is unstable with respect to the open state, and together with different metastable basins before the chemically-competent transition state, this crucial difference hampers incorporation of incorrect nucleotide units.

In bridging the conceptual gap between crystal structures and kinetic data, our computa-tional link can contribute valuable insights into the factors that affect fidelity discrimination in DNA synthesis and repair. The cascade of transition states navigating base-pair selection can serve to guide crystallization experiments of key intermediates along the pathway, particularly of mismatches (e.g., [20,21]), to further interpret fidelity mechanisms. Taken together, these cooperative motions of key enzyme residues suggest sequential inspection and surveillance mechanisms which trigger context-specific and substrate-sensitive conformational, energetic, and dynamic pol β pathways.

Computational Methodology

A. System Preparation

Models of solvated pol β/DNA/dCTP (correct G:C system) and pol β/DNA/dATP (incorrect G:A system) complexes were prepared from 1BPX (open binary) and 1BPY (closed ternary) crystal structures [2]. Hydrogen atoms were added by CHARMM's subroutine HBUILD [22]. Also added were: a hydroxyl group to the 3′ terminus of the primer DNA strand, missing residues 1–9 of pol β, and specific water molecules coordinated to the catalytic Mg2+ (missing in the ternary complex). For the G:C system, the open complex was modified by incorporating the incoming unit dCTP (deoxyribocytosine 5′-triphosphate) with nucleotide-binding Mg2+, producing the 1BPX ternary complex. For the G:A system, the open and closed complexes were built from the G:C system by replacing the incoming dCTP by dATP and orienting the dATP in an anti conformation, following the crystal structure of pol β with a mispair in the active site [20]. We note that the same mismatch (template G, incoming A) was found to be in the anti-anti conformation in the crystal complexes of high-fidelity Bacillus DNA polymerase I solved in the Beese group [21].

Cubic periodic domains for both initial models were constructed using Simulaid and PBCAID [23]. To neutralize the system at an ionic strength of 150 mM, water molecules with minimal electrostatic potential at the oxygen atoms were replaced by Na+, and those with maximal electrostatic potential were replaced with Cl−. All Na+ and Cl− ions were placed more than 8 Å away from any protein or DNA atoms and from each other. The electrostatic potential for all bulk oxygen atoms was calculated with DelPhi. The resulting system has 40238 atoms (including 11249 water molecules). Consistent with a pH value of 7.0, we assume de-protonated states (i.e., −1 charge each) for Asp190, Asp192, and Asp256, as made recently [24]. Appendix A (appendices are provided under supplementary information) provides protonation states of titratable side chains with discussion. These settings produce a net charge of +7 for pol β, −29 for DNA, and −4 for the dNTP. There are 42 Na+ ions, 20 Cl− ions, 2 Mg2+ ions, producing a charge of 26 and overall neutral system.

B. Minimization, Equilibration and Dynamics Protocol

Energy minimizations, equilibration, and dynamics simulations were performed using the program CHARMM [22, 25] and the all-atom version c28a3 forcefield (Chemistry Department, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA). The system was minimized using the Steepest Descent method for 10,000 steps followed by Adapted Basis Newton-Raphson [22,26] for 20,000 steps. The system was then equilibrated for 1 nanosecond at room temperature by the Verlet integrator in CHARMM prior to dynamics production runs.

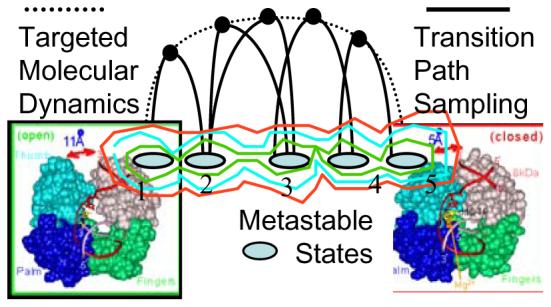

C. Transition Path Sampling (TPS) and BOLAS Free Energy Protocols

Very recently, we have developed a general protocol for harvesting mechanistic pathways for macromolecular systems by transition path sampling [17,27] using a divide-and-conquer approach. Our protocol has developed strategies to [15]: (i) generate initial trajectories, (ii) identify the different transition state regions, (iii) implement transition path sampling sampling in conjunction with CHARMM [22], (iv) assess convergence, and (v) compute the reaction free energy pathway [18]. In this work, we also develop and apply in this context a network model for generating reaction rates as a result of the combined transition states (see Section E below, and Fig. 4). Details of TPS and BOLAS are available in Refs. [15,18].

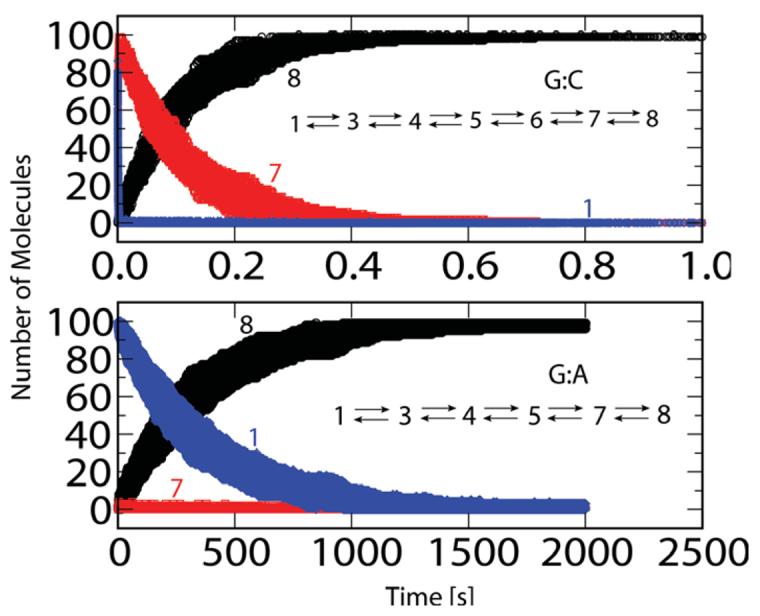

Figure 4.

Comparison of reaction kinetics for G:C and G:A systems. The temporal evolution of open (blue band), closed (red band) and product (black band) species are derived based on 100 evolution trajectories from binary (open) complexes. Inset describes the reaction networks according to profiles in Fig. 1. The networks are solved with the stochastic algorithm of Gillespie [19] (Appendix D). The spread in the kinetics (thickness of bands shown) represents the inherent stochasticity of the system and is not due to variations in the values of the individual rate-constants (kijs in Table I). The effect of uncertainties in the kij values on the time evolution has not been considered here.

As described in Ref. [15] (see also Appendix B), trajectories in each transition state region are harvested using the shooting algorithm [27] to connect two metastable states via a Monte Carlo protocol in trajectory space. In each shooting run, the momentum perturbation size dP ≈ 0.002 in units of amu×Å/fs is used to yield an acceptance rate of 25 to 30%.

For the free energy calculation [18], the probability distribution P(χi) was calculated by dividing the range of order parameter χi into 10 windows. The histograms for each window are collected by harvesting 300 (accepted) trajectories per window according to the procedure outlined in Ref. [18], from which the potential of mean force Λ(χi) is calculated (Appendix B). The arbitrary constant associated with each window is adjusted to make the Λ function continuous. The standard deviation in each window of the potential of mean force calculations is estimated by dividing the set of trajectories in two blocks and collecting separate histograms. The statistical error of ±3kBT in the free energy is estimated from the order parameter window showing the maximum standard deviation in the potential of mean force.

D. Mixed Quantum Mechanics and Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) Simulations of Pol β's Active-Site

The QM/MM approach we adopt is based on an existing interface between GAMESS-UK [28] (an ab-initio electronic structure prediction package) and CHARMM (see Appendix C for details). To focus on the active site of a solvated pol β system with correct (G:C) and incorrect (G:A) base pairs, we define the quantum region (see circled area of Fig. 3 later) as the two Mg2+ ions; the conserved aspartates 190, 192, 256; incoming nucleotide; terminal primer of DNA; Ser 180; Arg 183; and water molecules within hydrogen bonding distance of the QM atoms. These 86 atoms are treated in accord with density functional theory using a B3LYP density functional and 6-311G basis set. The molecular mechanical region consists of the rest of the protein, DNA, Na+, Cl−, and solvent molecules up to three solvation shells (extending over 12 Å) adjoining the protein/DNA/dNTP complex. Wave function optimizations in the QM region are performed according to a density functional formalism, and geometry optimizations of the whole system were performed using the Adopted Basis Newton Raphson method implemented in CHARMM.

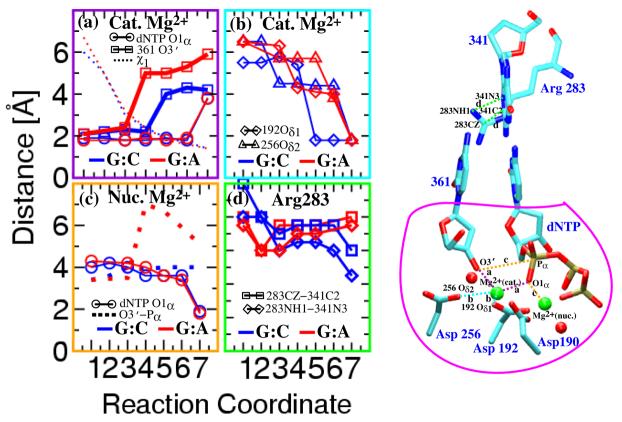

Figure 3.

Evolution of average distances of ligands coordinating the catalytic and nucleotide-binding Mg2+ ions along the reaction coordinate for G:C and G:A. Metastable states 1 to 7 evolve the system in the closing pathway. The extent of thumb closing (χ1 at top), and a crucial distance for the chemical reaction (O3′ of last primer (guanine) residue to Pα of dCTP in bottom plot) are also provided. Coordination and distances are diagrammed on the right: catalytic site ready for the phosphoryl transfer reaction. Circled area represents the QM region

E. Analysis of Reaction Kinetics Using the Gillespie Algorithm

We use Gillespie's method [19] to simulate the time evolution of our system in terms of a network of elementary chemical reactions. In contrast to the traditional approach of treating a network of reactions as a deterministic system and solving a coupled set of differential equations to obtain the temporal evolution of concentrations of species, Gillespie's method considers reaction kinetics profile as a random walk governed by the master equation; thus, reaction events occur with specified probabilities, and each event alters the probabilities of subsequent events. The stochastic nature of the calculation is crucial if the absolute number of reactant or intermediate species in the system is not large.

As detailed in Appendix D, the elements in the reaction network consist of the identified metastable states between the open and closed conformations of the enzyme and, in addition, the chemical reaction step. The rate constants for hopping between adjacent metastable states are obtained from the BOLAS free energy computations for the G:C and G:A systems and that for the chemical step derived from experimentally measured kpol values [3-5,29-37]. A summary of the free energy barriers, rate constants, and kpol values for the matched (G:C) system and the mismatch (G:A) system is provided in Table I later. These network simulations are performed using the STOCKS simulator [38], with a timestep corresponding to one hundredth of the timescale of the fastest transition. One hundred independent trajectories of evolution were simulated to account for the stochastic nature inherent in the kinetic model.

Table I.

Rates kTST estimated by transition state theory

| TS1 | TS2 | TS3 | TS4 | TS5 | TS6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matched G:C system | ||||||

| τmol [ps] | 70 | 4 | 2.5 | 4 | 4 | 0.2a |

| 14 | 4 | 10 | 4 | 7.5 | 27 | |

| 5 | 6 | 16.5 | 6 | 9 | – | |

| 1.2 × 104 | 5 × 109 | 2.5 × 107 | 5 × 109 | 2 × 109 | 9 | |

| 1 × 108 | 6 × 108 | 1 × 104 | 6 × 108 | 3 × 107 | 0 | |

| Mismatched G:A system | ||||||

| τmol [ps] | 70 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 0.2a | |

| 14.5 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 27 | ||

| 2.5 | 6 | 8 | 2 | – | ||

| 6 × 103 | 6 × 108 | 6 × 108 | (−)c | 9 | ||

| 1 × 109 | 6 × 108 | (2 × 107)c | (−)c | 0 | ||

Calculated as (kBT/h)−1

is the free energy of the transition-state region between basins A and B relative to basin A. For example, considering the adjacent states A and B as metastable states 3 and 4 (separated by TS 2), and .

In order to make the system of equations well-conditioned, we clubbed the free energy barriers and for TS 4 with TS 3 for the mismatch. The numbers in parenthesis reflect this reorganization.

Results

Transition State Identification

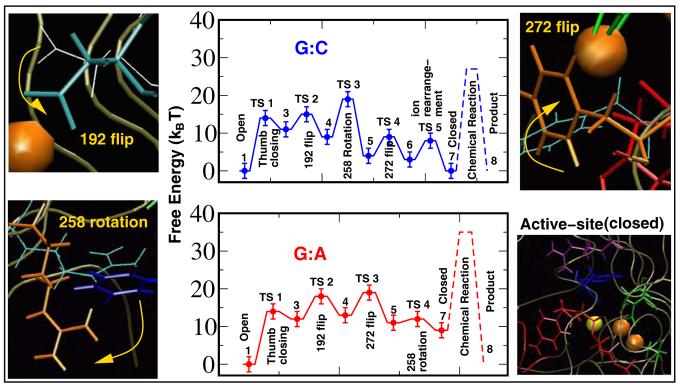

Our analyses of detailed closing pathways before the chemical reaction identify five transition states for the matched G:C system and four transition states for the mismatched G:A system (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Overall captured reaction kinetics profile for pol β's closing transition followed by chemical incorporation of dNTP for G:C and G:A systems. The barriers to chemistry (dashed peaks) are derived from experimentally measured kpol values [3-5,29]. The profiles were constructed by employing reaction coordinate characterizing order parameters (χ1–χ5) in conjunction with transition path sampling (Appendix B). The order parameters χ1–χ5 serve as reaction coordinates to characterize the transition states TS 1–TS 5 in the matched G:C system, as well as TS 1–TS 4 in the mismatched G:A system. The potential of mean force along each reaction coordinate is computed for each conformational event (Appendix B, Figs. S2 and S3). The relative free energies of the metastable states and the free-energy barrier characterizing each transition state are calculated with BOLAS [18].

The following order parameters (χ1–χ5) characterize the reaction profiles [15]: χ1 = measuring the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of heavy atoms in amino acid residues 275–295 in pol β that form the thumb's helix N [2] with respect to the same atoms in the enzyme's closed state (1BPY); χ1 varies from ∼ 6 to 1.5 Å between the open and closed states. χ2 is the dihedral angle defined with respect to the quadruplet of atoms Cγ–Cβ–Cα–C in Asp192; χ2 varies from ∼ 90 to 180° between the unflipped and the flipped states of Asp192. χ3 is dihedral angle Cγ–Cδ–Cε–Cζ, describing the rotation state of Arg258 (dihedral angle Cβ–Cγ–Cδ–Nε is an alternative); χ3 varies between ∼100 and 260° between the unrotated and fully-rotated states of Arg258. (A partially-rotated state (χ3 ≈ 180°) is also observed as a metastable state). χ4 is dihedral angle Cδ1–Cγ–Cβ–Cα describing Phe272; χ4 varies from ∼ −50 to 50° between the unflipped and the flipped states of Phe272. χ5 is the distance between the nucleotide binding Mg2+ ion and the oxygen atom O1α of dCTP; χ5 varies between 3.5 Å and 1.5 Å in a subtle ion-rearrangement in the catalytic region.

These five order parameters characterize all transition states. For G:C, TS 1 is the closing of the thumb, TS 2 is the Asp192 flip, TS 3 is the partial rotation of Arg258, TS 4 is the Phe272 flip, and TS 5 defines a subtle ion-rearrangement in the catalytic region involving the Mg2+ ions and is also associated with the stabilization of Arg258 in its fully rotated state (TS 3 is the partial rotation) which accompanies the ion-rearrangement. For the mismatch, TS 1 is the thumb closing, TS 2 is Asp192's flip, TS 3 is the Phe272 flip, and TS 4 is the complete rotation of Arg258. Significantly, the ion-rearrangement step is absent in the mismatched system, resulting in a disordered active-site that is further away (in space) from the reaction competent state (Fig. 1).

The sequence of the transition states along the closing pathways for both the G:C and G:A systems is determined by ranking the values of the order parameters in the metastable states using a histogram analysis [15]; for example, if χ2 changes from unflipped (in open) to flipped (in closed) values while χ3, χ4, χ5 remain at values of the open structure, we know that TS 2 precedes TS 3–5. For the G:C pathway, the order of events was: thumb closing, Asp192 flip, partial rotation of Arg258, Phe272 flip, and ion-rearrangement in the catalytic region. For the G:A pathway, the thumb closing was followed by Asp192 flip, Phe272 flip, and rotation of Arg258. Thus, the Phe272 flip occurs before rather than after the Arg258 rotation in the mismatch system, and the crucial ion-rearrangement is lacking for G:A compared to G:C.

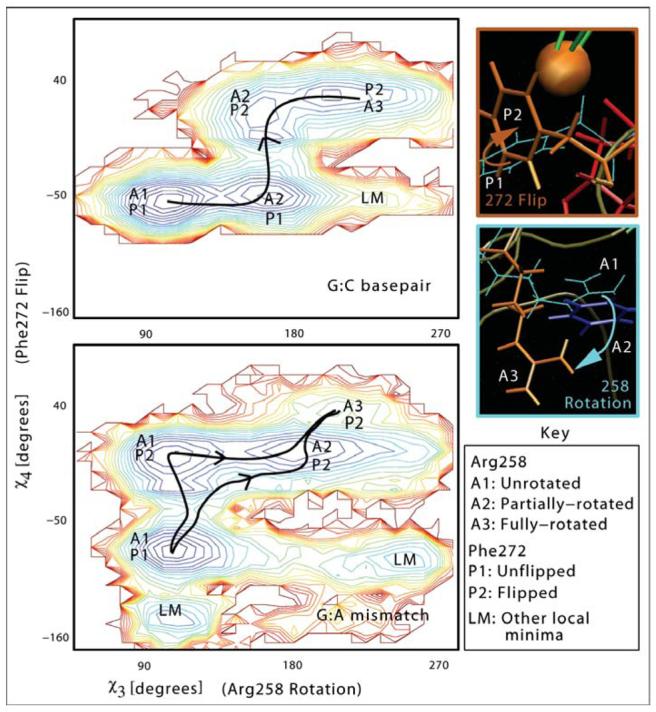

Pathway Analysis

The striking differences in the sequence of events in these pathways are evident by analyzing the conformational states visited in the dynamics trajectories (Fig. 2). Here, we describe the conformational landscapes of the Arg258 rotation and Phe272 flip for each system as contour plots of the function −ln P(χ3, χ4), where χ3, χ4 are the dihedral angles characterizing Arg258 rotation, Phe272 flip, and P(χ3, χ4) is the two-dimensional (2D) probability distribution; P(χ3, χ4) is calculated by accumulating a 2D histogram (of χ3 and χ4) using the harvested trajectories. The metastable states correspond to the blue basins (high probability states), while the transition states correspond to the saddles. Red regions correspond to low probability (high free energy) states. Physical pathways capturing the Arg258's rotation and Phe272's flip are those that connect basins (A1,P1) and (A3,P2) and pass through saddle regions. In both the G:C and G:A cases, the Arg258 rotation occurs in two steps (through the intermediate state A2). The Phe272 flip follows the partial rotation of Arg258 for the G:C case, while the order is reversed for the G:A case. Even more interesting, the G:C landscape exhibits a unique pathway with most of the local minima lying along the physical pathway, while the G:A landscape reveals multiple paths as well as other local minima that do not lie along any R258, F272 rotation/flip pathway.

Figure 2.

Conformational landscapes for the rotation and flipping of Arg258 and Phe272, in the conformational closing pathway of pol β for G:C versus G:A systems.

Potential of Mean Force Calculations

The free energy changes associated with each transition event (Table I) are derived from the potential of mean force calculations (see methodology, and Figs. S2 and S3 of Appendix B), which are used to construct the overall reaction kinetics profiles below. Given the error bars, the barrier corresponding to TS 4 for the mismatch associated with Arg258 rotation may or may not exist. However, given the prominence of this barrier in the G:C system, we depict it for the G:A system (see Fig. 1). Irrespective of the existence of a barrier to Arg258 rotation in G:A system, the event occurs and follows the Phe272 flip and hence represents a step in our cascade of events for the closing conformational change in the mismatched system. The relative unimportance of this barrier for the energetics of the mismatch profile suggests that this residue is not likely to play a crucial role in the discrimination of correct versus incorrect nucleotide incorporation. Kinetics experiments on a R258A mutant system have revealed a modest (2–4 fold) increase in catalytic efficiency and no change in fidelity in comparison to the wildtype enzyme [W. A. Beard and S. H. Wilson, unpublished results].

The conformational profile (Fig. 1) reveals key differences in thermodynamic quantities for G:C vs. G:A. Despite similar overall activation free-energy barriers for conformational change (19 ± 3 kBT), the closed state is thermodynamically stable for the correct G:C system, but only metastable (i.e., higher in free energy by 9 kBT than the open state) for the G:A mispair. Significantly, these barriers are of the same order of magnitude as that for the overall process (including chemistry): 25–28 kBT for G:C, 36 kBT for G:A, obtained from the experimentally measured rate-constants kpol = 3–100 s−1 and 0.002 s−1, respectively [3-6], where kpol is related to the free energy barriers ΔF via kpol = (kBT/h)×exp(−βΔF). These values suggest that even if the chemical step and not the conformational step is rate limiting, the conformational rearrangements prior to the actual chemical reaction direct the system to the reaction-competent state in a substrate-sensitive manner and cause the mismatched closed state to be unstable. This relative instability, together with the disordered catalytic active site for the mispair (Fig. 3), produce the different free energy barriers and hence overall fidelity discrimination.

That substrate-induced conformational changes directly affect fidelity of some moderate and high-fidelity polymerases is consistent with the notion of geometric selection criteria, as recently shown for T7 polymerase encountering a lesion, which blocks the conformational change [39]. Exquisite crystal structures of mismatches for the Bacillus fragment also reflect the relationship between geometric distortion and fidelity [21].

Discussion

The highly cooperative dynamics associated with the conformational transition for pol β trigger systematic differences in the evolution of active-site geometries near the closed state (Figure 3). According to the two-metal-ion-catalyzed phosphoryl transfer mechanism [40], for which functional, kinetic evidence was provided by Bolton et. al. [41], the conserved protein residues of pol β (Asp190, Asp192, and Asp256) strategically orient the Mg2+ ions with respect to the Pα of the dCTP and the O3′ hydroxy terminal of last residue of the DNA primer (see Fig. 3). Our computed geometry of the catalytic region in the closed conformation for G:C is consistent with the two-metal-ion catalytic mechanism with the exception of O3′-Pα distance, which on average is 1.2 Å A larger than the ideal distance of 3.2 Å A for phosphoryl transfer by a dissociative mechanism [42,43]. The corresponding distance for the G:A mispair is significantly higher: 5.5 Å; the crucial distance between the catalytic Mg2+ and the nucleophilic O3′ oxyanion approaches different values (higher by about 1.8 Å A for G:A vs. G:C). Our combined quantum/classical optimizations (Appendix C) have shown that these differences are not mere force-field artifacts. Although subtle differences in the geometries resulting from CHARMM27 and the QM/MM were observed (Fig. S4), the essential differences in the active-site assembly between the G:C and G:A systems were preserved, suggesting that they indeed likely contribute to the discrimination of the incorrect substrate at the active-site. Moreover, the observed geometry for the correct substrate (G:C system) suggests a likely pathway for the initial proton abstraction by Asp256 — a network of hydrogen bonds through two mediating water molecules separating the Oδ2 atom of Asp256 and the O3′ atom — strongly implicating a concerted proton transfer mechanism for the deprotonation of the O3′ group. The possible occurrence of this proton transfer as a first step of the nucleotide incorporation reaction is consistent with the tour-deforce calculation by Warshel et. al. of the energy profiles for nucleotide incorporation in T7 polymerase [24], as well as the recent QM/MM study of the phosphoryl transfer catalyzed by β–phosphoglocomutase by Webster [44].

Thus, our data concerning the existence and impact of different coordination networks and their evolution toward the closed state compatible for the chemical reaction support early suggestions based on NMR studies by the Mildvan group; namely, that error verification or prevention steps following substrate binding but prior to primer elongation involve coordination of the enzyme-bound metal by the α and β-phosphoryl groups [45,46].

In addition, we find that the intimate interaction of the charged residue Arg283 (Fig. 3) with the nucleotide binding pocket (particularly the template residue) is different in the G:C vs. G:A cases, suggesting an energetic discrimination (causing a destabilization of the mismatch) in the environment of the nucleotide binding pocket. These cumulative differences likely produce the higher barrier for G:A in the chemical incorporation step and also explain why Arg283 mutant experiments reveal crucial effects on fidelity [6,47].

The difference in thermodynamic stabilities of the closed conformation between G:C and G:A systems (of 9 kBT, see Figure 1) is almost quantitatively rationalized by the different active-site geometries (Figure 3). The reduced electrostatic interaction (for the mismatch G:A system) between the O3′ of the terminal base of primer DNA and catalytic Mg2+ and that between Cζ of Arg283 and N3 of template base opposite the incomer each account for a lowering of 4 kBT energy. These simple estimates are based on differences in distances (r) translated into energies (E) by the application of Coulomb's law of electrostatics (E ∝ 1/r). Correspondingly, we expect the catalytic Mg2+ ion and Arg283 to play significant roles in stabilizing the closed conformation for the correct substrate (G:C system). In silico evidence for the former comes from dynamics studies [14] which suggest that closing before the chemical incorporation requires both divalent metal ions in the active site while opening after chemical incorporation is triggered by release of the catalytic metal ion. The importance of Arg283 in pol β's activity is already appreciated from the studies of the enzyme mutant R283A, which exhibits a 5000-fold decrease in catalytic efficiency and a 160-fold decrease in fidelity, in comparison to wildtype [6]. These combined studies lend additional support to the group-contribution view (of template stabilized discrimination [47]) in rationalizing the stability differences between pol β complexes with correct and incorrect substrates.

We further demonstrate the significance of the cascade of subtle events orchestrating the active-site assembly for the correct vs. mismatch systems prior to the chemical incorporation and subsequent catalysis by solving a network model of elementary chemical reactions (inset in Figure 4 and Appendix D) to produce the overall rates for the combined process. The elementary reactions and associated rate constants used to construct the entire reaction evolution are gleaned from the transition state and free energy estimates (Table I, also see Appendix D). The resulting profiles in Fig. 4 reveal a striking difference in the evolution of reactants, products, and reaction intermediates between the G:C and G:A systems. The (blue) curve corresponding to the open enzyme state for the matched system rapidly disappears, with the closed state (red band, MS 7) quickly emerging and transitioning into product (black band, MS 8), where dCTP has been incorporated into the primer strand opposite the template guanine residue. Around 0.1 s, which corresponds to the experimental kpol of 10 s−1 [3-5,29], the product curve sharply rises, until all species are product (∼ 1 s).

For the mismatched system, in contrast, the open enzyme state (blue band) disappears very slowly, and the closed enzyme state (red) disappears sharply due to its instability. The product forms much more slowly (black band), in significant amount (>67 %, the time at which the percentage of product species reaches this level corresponds to ) only around 500 s, corresponding to kpol = 0.002 s−1 [3-5,29] for the mismatched G:A system.

Since the transition events follow in sequence, the individual kijs can affect the kinetics (time evolution) in numerous ways and corroborate to produce the overall difference in fidelity discrimination. However, the contrast in time evolution of the products between G:C and G:A systems (black bands in Fig. 4) is mainly due to the difference in the overall height of the barrier to the chemical reaction (see dotted lines in Fig. 1). Likewise, the contrast in the time evolution of the closed state (MS 7, red bands) is primarily due to the differences in the relative stabilities of the closed state (MS 7) with respect to the open state (MS 1). In particular, the stable MS 7 for the G:C system causes a transient accumulation of the closed state, an outcome not observed for the G:A system. These two dominant features also govern the differences in time evolution of the open state (blue bands in Fig. 4).

In conclusion, the unraveled cascade of transition states during the closing pathways of correct (G:C) system versus incorrect (G:A) pol β systems suggests crucial differences in the evolution of the active-site assembly towards the two-metal-ion transition state geometry. The more highly distorted and notably less stable active-site for the mismatch (by 9 kBT) establishes a source of discrimination and hence selection criteria for the incoming nucleotide unit. Subject to the force-field approximations and statistical inaccuracies [15], we identify similar barriers to closing prior to chemical incorporation for both systems (19 kBT). These, taken together with overall barriers inferred from experimentally measured kpol values (27 kBT for G:C and 36 kBT for G:A [3-5,29]), point to a rate-limiting chemical incorporation step for both systems. Our reaction profiles (Fig. 1) clearly separate the conformational change step (solid lines) from the chemical incorporation step (dashed lines), and our free energy delineation for the conformational closing prior to chemical incorporation identifies the Arg258 rotation as the rate-limiting step during the conformational change. Our results indicate that the rate-limiting step in the overall nucleotide incorporation process for matched as well as mismatched systems occurs after the closing conformational change. These conclusions are consistent with our earlier studies [9,10,15].

The recent mechanistic enzymology study of DNA pol β by the Tsai group [48] incorrectly summarizes our overall conclusions from recent modeling works. Bakhtina et al. [48] quoted directly from our earlier work on the conformational pathway component of the insertion reaction for pol β's G:C system [14]: “the binding of the catalytic magnesium and the rearrangement of Arg258 may be coupled and represent a slow step in pol β closing before chemistry”. The word “slow” is not synonymous with “rate-limiting” for overall insertion, and any chemical barriers to insertion were not directly addressed in our work. Yet, as discussed above, from comparisons of the computed conformational barriers and the experimentally measured kpol, we suggest that chemistry is rate-limiting for the overall insertion pathway. This point was also discussed in in Ref. [15], and reiterated in later work, where we concluded (and provided experimental hints to the notion) that “additional high-energy barriers must be overcome to reach the ideal geometry appropriate for the chemical reaction” [49]; see also [50,51]. Thus, our computational studies here and elsewhere [14,15,50] do not contradict the results from the fluorescence experiments of Bakhtina et. al. regarding energetics or sequence of events of pol β's nucleotide incorporation cycle. However, a direct comparison of the Bakhtina et. al. experiments with our computational results warrants caution because the non-native experimental conditions used by Bakhtina et. al., namely modified medium (high viscosity sucrose), substrate (deoxyribonucleoside triphoshphate-α-S), as well as ion (inert metal ion Rh(III)) may alter the energy landscape of nucleotide insertion from that of the native system (i.e., in water, with dNTP and divalent ions), on which our computations are based. We reiterate the main points in our computational work — that the chemical step is likely rate-limiting, but that subtle and sequential conformational events occur as the enzyme is steered by substrate binding to the requisite active conformation required for chemistry. In light of the lack of direct experimental evidence for pol β [8], our computed kinetics profiles in Fig. 4 (subject to the statistical uncertainties, see figure caption) also represent valuable predictions that can be tested by pulse-chase/pulse-quench kinetics experiments.

Work in progress suggests that the rate-limiting step for pol β occurs subsequent to nucleotide alignment in the active-site (closing conformational change) and just prior to the actual (phosphoryl transfer) reaction, in a “pre-chemistry avenue” that slowly adjusts metal/phosphoryl coordination at the active-site [Schlick et. al., unpublished results]. Recent NMR studies [52] that indicate localized motions near methionine residues (of which Met191 and Met155 are proximal to metal binding ligands Asp190 and Asp192) along with pioneering work by the Mildvan group [46] corroborate this intriguing possibility that error verification or prevention steps — following substrate binding but prior to primer elongation — involve coordination of enzyme-bound metal-ions by the alpha and beta-phosphoryl groups. Like Alice in Wonderland searching for the golden key to unlock the mysterious doors, the search for unraveling fidelity mechanisms is revealing a sequence of gates — “paths” in conformational, pre-chemistry, and chemistry — through which the passage has crucial biological ramifications. Further experimental and modeling studies are underway to explore the existence of the pre-chemistry avenue and detail the chemical reaction pathway.

Supplementary Material

Table of Content Graphics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Samuel Wilson and William Beard for helpful comments on this work, and Linjing Yang and Karunesh Arora for many stimulating discussions throughout this work. We thank Martin Karplus for use of the CHARMM program and Bernard Brooks, Martin Guest, and Paul Sherwood for help with GAMESS-UK. Acknowledgment is made to NIH grant R01 GM55164, NSF grant MCB-0239689, and the donors of the American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund for support of this research. Computational resources were partly provided by the Advanced Biomedical Computing Center.

Literature cited

- 1.Friedberg EC. Nature. 2003;421:436–439. doi: 10.1038/nature01408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sawaya MR, Prasad R, Wilson SH, Kraut J, Pelletier H. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11205–11215. doi: 10.1021/bi9703812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn J, Kraynov VS, Zhong X, Werneburg BG, Tsai M-D. Biochem. J. 1998;331:79–87. doi: 10.1042/bj3310079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vande Berg BJ, Beard WA, Wilson SH. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:3408–3416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002884200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah AM, Li S-X, Anderson KS, Sweasy JB. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:10824–10831. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008680200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beard WA, Osheroff WP, Prasad R, Sawaya MR, Jaju M, Wood TG, Kraut J, Kunkel TA, Wilson SH. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:12141–12144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Showalter AK, Tsai M-D. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10571–10576. doi: 10.1021/bi026021i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joyce CM, Benkovic SJ. Biochemistry. 2004;43:14317–14324. doi: 10.1021/bi048422z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang L, Beard WA, Wilson SH, Broyde S, Schlick T. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;317:651–671. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang L, Beard WA, Wilson SH, Roux B, Broyde S, Schlick T. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;321:459–478. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00617-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arora K, Schlick T. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2003;378:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rittenhouse RC, Apostoluk WK, Miller JH, Straatsma TP. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003;53:667–682. doi: 10.1002/prot.10451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang L, Beard WA, Wilson SH, Broyde S, Schlick T. Biophysical J. 2004;86:3392–3408. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.036012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang L, Arora K, Beard WA, Wilson SH, Schlick T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:8441–8453. doi: 10.1021/ja049412o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radhakrishnan R, Schlick T. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2004;101:5970–5975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308585101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunkel TA, Bebenek K. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:497–529. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dellago C, Bolhuis PG, Geissler PL. Adv. Chem. Phys. 2002;123:1–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.53.082301.113146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radhakrishnan R, Schlick T. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;121:2436–2444. doi: 10.1063/1.1766014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillespie DT. J. Phys. Chem. 1977;81:2340–2361. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krahn JM, Beard WA, Wilson SH. Structure. 2004;12:1823–1832. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson SJ, Beese LS. Cell. 2004;116:803–816. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. J. Comp. Chem. 1983;4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qian X, Strahs D, Schlick T. J. Comp. Chem. 2001;22:1843–1850. doi: 10.1002/jcc.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Florián J, Goodman MF, Warshel A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:8163–8177. doi: 10.1021/ja028997o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacKerell AD, Jr., Banavali NK. J. Comp. Chem. 2000;21:105–120. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schlick T. In: Reviews in Computational Chemistry. Lipkowitz KB, Boyd DB, editors. III. VCH Publishers; New York, NY: 1992. pp. 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bolhuis PG, Dellago C, Chandler D. Faraday Discuss. 1998;110:421–436. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt MW, Baldridge KK, Boatz JA, Elbert ST, Gordon MS, Jensen JJ, Koseki S, Matsunaga N, Nguyen KA, Su S, Windus TL, Dupuis M, Montgomery JA. J. Comput. Chem. 1993;14:1347–1363. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suo Z, Johnson KA. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:27250–27258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kraynov VS, Werneburg BG, Zhong X, Lee H, Ahn J, Tsai M-D. Biochem. J. 1997;323:103–111. doi: 10.1042/bj3230103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhong X, Patel SS, Werneburg BG, Tsai M-D. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11891–11900. doi: 10.1021/bi963181j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dahlberg ME, Benkovic SJ. Biochemistry. 1991;30:4835–4843. doi: 10.1021/bi00234a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuchta RD, Mizrahi V, Benkovic PA, Johnson KA, Benkovic SJ. Biochemistry. 1987;26:8410–8417. doi: 10.1021/bi00399a057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong I, Patel SS, Johnson KA. Biochemistry. 1991;30:526–537. doi: 10.1021/bi00216a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel SS, Wong I, Johnson KA. Biochemistry. 1991;30:511–525. doi: 10.1021/bi00216a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frey MW, Sowers LC, Millar DP, Benkovic SJ. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9185–9192. doi: 10.1021/bi00028a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Capson TL, Peliska JA, Kaboord BF, Frey MW, Lively C, Dahlberg M, Benkovic SJ. Biochemistry. 1992;31:10984–10994. doi: 10.1021/bi00160a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kierzek AM. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:470–481. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y, Dutta S, Doubli S, Bdour HM, Taylor J, Ellenberger T. Nat. Struc. Biol. 2004;11:784–790. doi: 10.1038/nsmb792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steitz TA, Steitz JA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:6498–6502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bolton EC, Mildvan AS, Boeke JD. Molec. Cell. 2002;9:879–889. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00495-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mildvan AS. Proteins: Stru. Fun. Gen. 1997;29:401–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lahiri SD, Zhang G, Dunaway-Mariano D, Allen KN. Science. 2003;299:2067–2071. doi: 10.1126/science.1082710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Webster CE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:6480. doi: 10.1021/ja049232e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrin LJ, Mildvan AS. Biochemistry. 1986;25:5131–5145. doi: 10.1021/bi00366a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferrin LJ, Mildvan AS. DNA replication and recombination. Alan R. Liss, Inc.; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beard WA, Wilson SH. Chem. Biol. 1998;5:R7–R13. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bakhtina M, Lee S, Wang Y, Dunlap C, Lamarche B, Tsai M-D. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5177–5187. doi: 10.1021/bi047664w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arora K, Schlick T. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:5358–5367. doi: 10.1021/jp0446377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arora K, Schlick T. Biophys. J. 2004;87:3088–3099. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.040915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arora K, Beard WA, Wilson SH, Schlick T. Biochemistry. 2005 doi: 10.1021/bi0507682. Accepted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bose-Basu B, DeRose EW, Kirby TW, Mueller GA, Beard WA, Wilson SH, London RE. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8911–8922. doi: 10.1021/bi049641n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.