Abstract

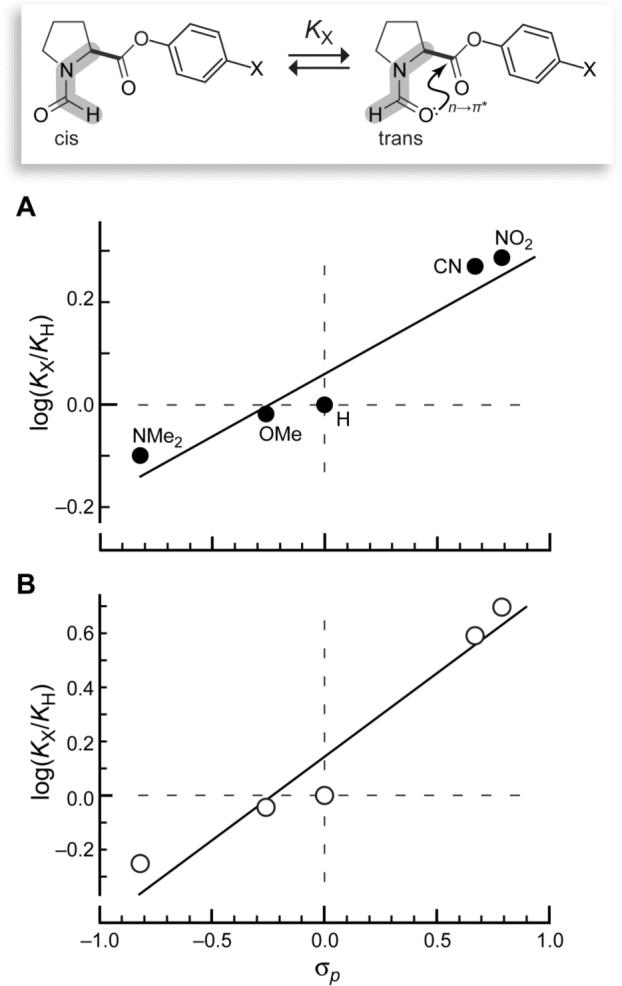

The trans/cis ratio of the amide bond in N-formylproline phenylesters correlates with electron-withdrawal by a para substituent. The slope of the Hammett plot (ρ = 0.26) is indicative of a substantial effect. This effect arises from a favorable n→π* interaction between the amide oxygen and ester carbonyl. In a polypeptide chain, an analogous interaction can stabilize the conformation of trans peptide bonds, α-helices, and polyproline type-II helices.

Certain non-covalent interactions are known to direct a polypeptide chain to assume a folded structure. Those interactions include the hydrophobic effect, hydrogen bonding, Coloumbic forces, van der Waals forces, and cation–π interactions.1 Recently, we suggested that n→π* interactions should be added to this list.2,3 In an n→π* interaction (which is not to be confused with an n→π* electronic transition) the oxygen of a peptide bond (Oi−1) donates electron density from one of its lone pairs into the antibonding orbital of the carbon in the subsequent peptide bond (Ci′=Oi). This Oi−1···Ci′=Oi interaction, which mimics the approach of a nucleophile to the electrophilic carbon of an acyl group, is strongest when Oi−1 is positioned proximally and along the Bürgi–Dunitz trajectory to Ci′=Oi. In polypeptides, this geometry occurs in the α-helix and polyproline type-II (PPII) helix,2c which is the structure assumed by the strands of the prevalent collagen triple helix.3,4

The n→π* interaction can occur only if the peptide bond containing Oi−1 is trans (i.e., Z), as opposed to cis (E). Accordingly, the trans/cis ratio of an Xaai−1–Proi peptide bond can report on the strength of an n→π* interaction. We had demonstrated previously that the n→π* interaction contributes to the endogenous preference for trans peptide bonds.2c Here, we present a simple model system that uses the trans/cis ratio of a peptide bond to report on the energetics of an n→π* interaction.

We reasoned that the strength of an n→π* interaction could be altered by using p-substituted phenyl esters of N-formyl-l-proline to modulate the electrophilicity of the carbonyl (Ci′=Oi). Our expectation was that the trans/cis ratio would correlate with that electrophilicity. We chose N-formylproline because its trans/cis ratio is close to unity and can thus serve as the basis for a highly sensitive assay.2c The esters were synthesized by condensation of N-formylproline with the corresponding phenol using PyBOP activation, and were purified by flash chromatography.

We used 1H NMR spectroscopy to measure the trans/cis ratio of each ester (90−170 mM) in CDCl3. We chose chloroform as the solvent to minimize effects from differential solvation of the trans and cis isomers. Because the isomerization of the peptide bond is slow on the NMR timescale, two sets of signals were observed in the spectrum of each ester. Though most of the resonances exist as multiplets and overlap with those from their isomer, the resonance of the formyl proton appears as two singlets—one for each iso mer. The larger, upfield resonance arises from the trans isomer. Integration of the two signals provides the trans/cis ratio at the amide bond.

We find that more electron-withdrawing p-substituents correlate strongly with larger trans/cis ratios (Table 1). Moreover, a linear relationship exists between the log of the trans/cis ratio and the Hammett parameter (σp) of the substituent (Figure 1A), which is indicative of an electronic effect.5 The values of Ktrans/cis and σp are related by ρ = ∂log(KX/KH)/∂σp = 0.26. This ρ-value signifies that the electronic effect of X on Ktrans/cis is substantial, especially given that the interconversion of the cis and trans isomers of Fm–Pro–OC6H4-p-X does not involve a change in covalent bonding.

Table 1.

Trans/Cis Ratios (CDCl3) and σp Values of X in Fm–Pro–OC6H4-p-X at 25 °C.

| X | σpa | Ktrans/cis | ΔG (kcal/mol)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| NO2 | 0.78 | 4.13 ± 0.05 | −0.84 |

| CN | 0.66 | 3.95 ± 0.03 | −0.81 |

| H | 0.00 | 2.120 ± 0.005 | −0.45 |

| OMe | −0.27 | 2.01 ± 0.04 | −0.41 |

| NMe2 | −0.83 | 1.67 ± 0.02 | −0.30 |

From ref. 6.

ΔG = –RTlnKtrans/cis.

Figure 1.

Relationship between the trans/cis ratio and electron-withdrawing ability of X in Fm–Pro–OC6H4-p-X. (A) Values of KX are from experimental data (Table 1) and give ρ = 0.26. (B) Values of KX are from density functional theory calculations on the trans isomer with Cγ-exo pyrrolidine ring pucker (Table 2) and give ρ = 0.60.

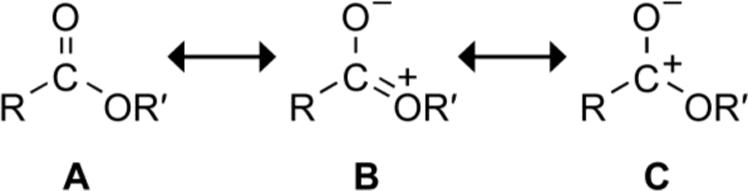

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations predicted a similar correlation between Ktrans/cis and σp (Table 2; Figure 1B), and enabled a detailed analysis. Electron-withdrawing substituents on a phenyl ring are known to increase the electrophilicity7 (and reactivity5) of aryl esters. The electronics of an ester can be described by three major resonance forms: A–C (Scheme 1). As the phenyl substituent becomes more electron-withdrawing, forms B and C become disfavored8 due to π-polarization.9 The diminished delocalization increases the energy of the Ci′=Oi π orbital and decreases the energy of the Ci′=Oi π* orbital, making Ci′=Oi more electrophilic. The decreased delocalization is also manifested in the increased contribution from resonance form A, which results in greater double-bond character and higher Ci′=Oi vibrational frequency.8 These effects are observed theoretically in the cis isomer, which represents the ester electronics in a state unperturbed by the n→π* interaction. In the cis isomer, the calculated vibrational frequency ( vCi′=Oi ) of the carbonyl increases with the electron-withdrawing ability of the p-substituent (Table 2). Moreover, natural bond order (NBO10) analysis of the cis isomer demonstrates a decrease in the ester π* orbital energy ( Eπ*Ci′=Oi ) with increasing electron withdrawal (Table 2). These two effects are indicative of the increased electrophilicity of Ci′=Oi that results from electron-withdrawing groups.

Table 2.

Results of Density Functional Theory Calculations (B3LYP/6−31+G*) and Natural Bond Order Analysis on the trans and cis Isomers of Fm–Pro–OC6H4-p-X with Cγ-exo Pyrrolidine Ring Pucker.

| X | ΔE (kcal/mol)a | νC′i=Oi (cm−1)b,c | Eπ*,C′i=Oi (Hartrees)c | En→π* (kcal/mol)d | rOi-1···C′i (Å)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO2 | 2.22 | 1837 | −0.43033 | 1.45 | 2.88 |

| CN | 2.08 | 1835 | −0.42692 | 1.39 | 2.89 |

| H | 1.27 | 1829 | −0.41043 | 0.86 | 2.98 |

| OMe | 1.22 | 1826 | −0.40713 | 0.83 | 2.99 |

| NMe2 | 0.94 | 1824 | −0.40115 | 0.68 | 3.02 |

ΔE = –RTlnKtrans/cis.

Unscaled.

cis Isomer.

trans isomer.

Scheme 1.

The strength of the n→π* interaction in the trans isomer was examined directly with NBO analysis. Second-order perturbation theory indicates that as the trans/cis ratio increases, so does the energy ( En→π*) of the interaction between the lone pair on the amide carbonyl oxygen and the π* orbital of the ester (Table 2). The increasing strength of the n→π* interaction is reflected in the decreasing distance ( rOi−1···Ci′ ) between the amide oxygen and ester carbon (Table 2). The value of ρ = 0.60 for the theoretical data (Figure 1B) is greater than that for the experimental data (Figure 1A). The pyrrolidine ring was held in the Cγ-exo conformation during the theoretical analyses, as this ring pucker allows for much greater n→π* interaction than does the Cγ-endo conformation.2b,11 The pyrrolidine ring has, however, a slight preference for the Cγ-endo pucker.12 Hence, the effect of the p-substituent on the trans/cis ratio is amplified in the calculations.

The link between the electron-withdrawing ability of the remote p-substituent and the trans/cis ratio support the role of an electronic n→π* interaction in the conformational preference of the amide bond. This effect cannot be steric. Located in the para position, the aryl substituent is remote from the amide bond. Moreover, if the effect were steric, then the trans/cis ratios would fall in line with the steric bulk of the substituent. Such a correlation was not observed, as the Ktrans/cis value of the smallest substituent, a proton, is between those of the largest substituents, dimethylamino and nitro.13

We conclude that an n→π* interaction occurs between the amide and ester groups in this model system. In addition, we propose that this interaction has important ramifications for protein structure. An n→π* interaction could stabilize not only a trans peptide bond, but also an α-helix and PPII helix.2c The α-helix,14 like the β-sheet,15 is stabilized by Ci′=Oi···H–N hydrogen bonds between main-chain atoms.1b,16 The Ci′=Oi bonds in α-helices are, however, demonstrably longer than those in β-sheets.17 This greater bond length is consistent with the manifestation of an n→π* interaction in an α-helix. In contrast to the α-helix and β-sheet, the PPII helix does not contain any hydrogen bonds between its main-chain atoms. Yet, recent data indicates a notable prevalence of the PPII helix in both folded proteins and unfolded polypeptide chains.18 We propose that the n→π* interaction stabilizes the PPII helix, contributing significantly to its prevalence. Accordingly, the n→π* interaction is a non-covalent interaction, like the hydrophobic effect, hydrogen bonding, Coloumbic forces, van der Waals forces, and cation–π interactions,1 that directs a polypeptide chain to assume a folded structure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to F. Weinhold (University of Wisconsin–Madison) for contributive discussions. J.A.H. was supported by postdoctoral fellowship AR48057 (NIH). This work was supported by grant AR44276 (NIH).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Procedures for the preparation of N-formylproline phenylesters, and related analytical data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.For reviews, see: Anfinsen CB. Science. 1973;181:223–230. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4096.223.Dill KA. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7133–7155. doi: 10.1021/bi00483a001.Pace CN, Shirley BA, McNutt M, Gajiwala K. FASEB J. 1996;10:75–83. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.1.8566551.Dougherty DA. Science. 1996;271:163–168. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5246.163.Guo W, Shea J-E, Berry RS. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005;1066:34–53. doi: 10.1196/annals.1363.025.Parsegian VA. van der Waals Forces: A Handbook for Biologists, Chemists, Engineers, and Physicists. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2005.

- 2.a Bretscher LE, Jenkins CL, Taylor KM, DeRider ML, Raines RT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:777–778. doi: 10.1021/ja005542v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b DeRider ML, Wilkens SJ, Waddell MJ, Bretscher LE, Weinhold F, Raines RT, Markley JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:2497–2505. doi: 10.1021/ja0166904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hinderaker MP, Raines RT. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1188–1194. doi: 10.1110/ps.0241903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For reviews, see: Jenkins CL, Raines RT. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2002;19:49–59. doi: 10.1039/a903001h.Raines RT. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1219–1225. doi: 10.1110/ps.062139406.

- 4.a Ramachandran GN, Kartha G. Nature. 1954;174:269–270. doi: 10.1038/174269c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ramachandran GN, Kartha G. Nature. 1955;176:593–595. doi: 10.1038/176593a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Rich A, Crick FHC. Nature. 1955;176:915–916. doi: 10.1038/176915a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Rich A, Crick FHC. J. Mol. Biol. 1961;3:483–506. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(61)80016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Bella J, Eaton M, Brodsky B, Berman HM. Science. 1994;266:75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.7695699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammett LP. Chem. Rev. 1935;17:125–136.Hammett LP. Physical Organic Chemistry. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1940. pp. 184–228.Shorter J. Chem. Listy. 2000;94:210–214.

- 6.Hansch C, Leo A, Taft RW. Chem. Rev. 1991;91:165–195. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conteras R, Andres J, Domingo LR, Castillo R, Perez P. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:417–422. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neuvonen H, Neuvonen K, Koch A, Kleinpeter E, Pasanen P. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:6995–7003. doi: 10.1021/jo020121c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bromilow J, Brownlee RTC, Craik DJ, Fiske PR, Rowe JE, Sadek M. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1981;2:753–759. [Google Scholar]

- 10.a Glendening ED, Badenhoop JK, Reed AE, Carpenter JE, Bohmann JA, Morales CM, Weinhold F. NBO 5.0. Theoretical Chemistry Institute, University of Wisconsin–Madison; Madison, WI: 2001. http://www.chem.wisc.edu/~nbo5. [Google Scholar]; b Weinhold F, Landis CR. Valency and Bonding: A Natural Bond Orbital Donor–Acceptor Perspective. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The pyrrolidine ring of proline actually prefers two distinct twist (rather than envelope) conformations. As Cγ experiences the largest out-of-plane displacement in these twisted rings, we refer to pyrrolidine ring conformations (herein and elsewhere) simply as “Cγ-exo” and “Cγ-endo”. For additional information, see: Giacovazzo C, Monaco HL, Artioli G, Viterbo D, Ferraris G, Gilli G, Zanotti G, Catti M. Fundamentals of Crystallography. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2002.

- 12.The pyrollidine ring of Ac–Pro–OMe has 66% Cγ-endo pucker and 34% Cγ-exo pucker in dioxane at 25 °C (ref 2b).

- 13.In contrast to para substituents, ortho substituents can have adverse steric consequences. For example, DFT analysis of the highly electron-withdrawing pentafluorophenyl ester showed a lower trans/cis ratio than in the unsubstituted phenyl ester, presumably due to a steric interaction between the ortho fluoro groups and the amide oxygen (data not shown).

- 14.Pauling L, Corey RB, Branson HR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1951;37:205–211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.37.4.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pauling L, Corey RB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1951;37:251–256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.37.5.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.For a historical review, see: Eisenberg D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:11207–11210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2034522100.

- 17.Lario PI, Vrielink A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:12787–12794. doi: 10.1021/ja0289954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.For reviews, see: Shi Z, Olson CA, Bell AJ, Jr., Kallenbach NR. Adv. Protein Chem. 2002;62:163–240. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(02)62008-x.Creamer TP, Campbell MN. Adv. Protein Chem. 2002;62:263–282. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(02)62010-8.Rath A, Devidson AR, Deber CM. Biopolymers. 2005;80:179–185. doi: 10.1002/bip.20227.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.