Abstract

Study Objectives:

Many patients undergo surgery for snoring and sleep apnea, although the efficacy and safety of such procedures have not been clearly established. Our aim was systematically to review studies of the efficacy and adverse effects of surgery for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea.

Design:

Systematic review.

Measurements:

PubMed and Cochrane databases were searched in September 2007. Randomized controlled trials of surgery vs. sham surgery or conservative treatment in adults, with daytime sleepiness, quality of life, apnea-hypopnea index, and snoring as outcomes were included. Observational studies were also reviewed to assess adverse effects. Evidence of effect required at least two studies of medium and high quality reporting the same result.

Results:

Four studies of benefits and 45 studies of adverse effects were included. There was no significant effect on daytime sleepiness and quality of life after laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty and radiofrequency ablation. The apnea-hypopnea index and snoring was reduced in one trial after laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty but not in another trial. Subjective snoring was reduced in one trial after radiofrequency ablation. No trial investigating the effect of any other surgical modality met the inclusion criteria. Persistent side-effects occurred after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and uvulopalatoplasty in about half the patients and difficulty in swallowing, globus sensation and voice changes were especially common.

Conclusions:

Only a small number of randomized controlled trials with a limited number of patients assessing some surgical modalities for snoring or sleep apnea are available. These studies do not provide any evidence of effect from laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty or radiofrequency ablation on daytime sleepiness, apnea reduction, quality of life or snoring. We call for research of randomized, controlled trials of surgery other than uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and uvulopalatoplasty, as they are related to a high risk of long-term side-effects, especially difficulty swallowing.

Citation:

Franklin KA; Anttila H; Axelsson S; Gislason T; Maasilta P; Myhre KI; Rehnqvist N. Effects and side-effects of surgery for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea – a systematic review. SLEEP 2009;32(1):27–36.

Keywords: Sleep apnea syndromes, snoring, surgery, adverse effects, meta-analysis

SNORING IS A SIGN OF INCREASED UPPER AIRWAY RESISTANCE, AND OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA IS CHARACTERIZED BY RECURRENT EPISODES OF UPPER airway obstruction during sleep. Excessive daytime sleepiness is common among heavy snorers and among patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome.1–3 A number of recent prospective studies report than patients with obstructive sleep apnea run an increased risk of stroke and early death.4–8

Surgical treatment for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea aims to increase the upper airway cross-sectional area, remove obstructive tissues, such as enlarged tonsils, or bypass the upper airway. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty became popular shortly after its introduction in 1981.9 The uvula, the distal part of the soft palate and the tonsils are removed, with the aim of enlarging the oropharyngeal airspace and thereby reducing sleep apneas, snoring, and daytime sleepiness. Laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty and temperature-controlled radiofrequency tissue ablation were subsequently introduced, and these surgical modalities could be performed under local anesthesia. Other surgical modalities include tracheostomy, inferior sagittal mandibular osteotomy and genioglossus advancement with hyoid myotomy and suspension, laser midline glossectomy and lingual plasty, maxillo-mandibular osteotomy and advancement, expansion sphincter pharyngoplasty, palatal implants, nasal surgery, epiglottoplasty for selected cases of laryngomalacia, and so on. The efficacy of surgical modalities has, however, been questioned in systematic reports, and laser-assisted uvulopalatopharyngoplasty is not recommended for the treatment of sleep disordered breathing.10–14 There is a lack of systematic reviews of adverse effects, as many subjects still undergo surgery because of snoring and sleep apnea.

The present aim was systematically to review studies of the efficacy and adverse effects of surgery for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea in adults.

METHODS

Search Strategy

PubMed and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register were searched on 1 September 2007; (“Sleep apnea syndromes” [Mesh] OR “Snoring” [Mesh]) AND (“Surgery” [Mesh] OR “Surgery” [Subheading] or Radiofrequency) Limits: English, Randomized Controlled Trial, Meta-Analysis.

PubMed was searched on 1 September 2007 for side-effects; sleep apnea syndromes/surgery [Mesh] OR snoring/surgery [Mesh] AND (adverse effects [Mesh Subheading] OR complications [Mesh subheading] OR complication [Text Word] OR complications [Text Word]) NOT (comment [Publication Type] OR editorial [Publication Type] OR news [Publication Type]) Limits: English.

Reference lists of all the identified articles were searched for additional studies.

Inclusion Criteria for the Selection of Articles and Study end Points

Two reviewers independently screened abstracts according to inclusion criteria. For all possibly relevant articles, full reports were requested. Randomized, controlled studies of medium and high quality comparing surgery for snoring or obstructive sleep apnea with sham operations or conservative treatment were included. The primary outcomes were daytime sleepiness measured using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, Multiple sleep latency test or Maintenance of wakefulness test and Quality of life. Secondary outcomes were the apnea-hypopnea index and severity of snoring.

The review of adverse effects included randomized, controlled studies and observational studies of medium and high quality reporting complications and side-effects of surgery other than post-operative pain. All studies reporting life-threatening side effects and deaths in relation to surgery were included.

Quality Assessment and Evidence Grading

A modified JADAD ranking scale from 0–5 was used to assess the quality of randomized, controlled trials.13,15 We used questions on single blinding instead of double blinding, with the following questions: Was the trial described as randomized? Was the allocation concealed? Were patients blinded to treatment alternative? Were investigators blinded to treatment alternative? Was there a description of withdrawals? A score of 0–2 was rated as poor quality, 3 as medium quality, and 4–5 as high quality.

The following scores were used for observational studies reporting side-effects. High quality required a prospective study; before and after data for adverse effects; defined groups of patients and a detailed description of methods and adverse effects; loss to follow-up of less than 30%. Medium quality required a prospective design or consecutive patients; a summary description of patients and methods; a detailed description of adverse effects; loss to follow-up of less than 30%.

Strong evidence required at least two studies of high quality reporting the same result. Moderate evidence required at least one study of high quality and two of medium quality, while limited evidence required at least two studies of medium quality.

Data Abstraction

The data were independently abstracted by two reviewers and the authors were contacted in the event of questions. The number of participants, baseline characteristics, type of surgery, time of follow-up, design, benefits and adverse effects were extracted.

Statistical Analysis

Means and 95% confidence interval (CI) for change in active treated patients compared with control patients was calculated from mean of change (after - before) and standard deviation of change (SD). Differences of mean change between active treatment and control treatment were presented with 95% confidence interval (95% CI). A significant effect was regarded when 0 was not included in the confidence interval. For meta-analysis, we used Cochrane Review Manager software (version 5.0; Cochrane Library Software, Oxford, England). Means and SD for change in outcome was entered in the analysis. The weighted mean difference was used for comparisons of change in difference between active treatment and control. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Weighted means for adverse effects were calculated as = Σ ni/n * pi. Where ni = number of treated patients, n = sum of all treated patients and pi = proportion of patients with an adverse effect.

RESULTS

Efficacy

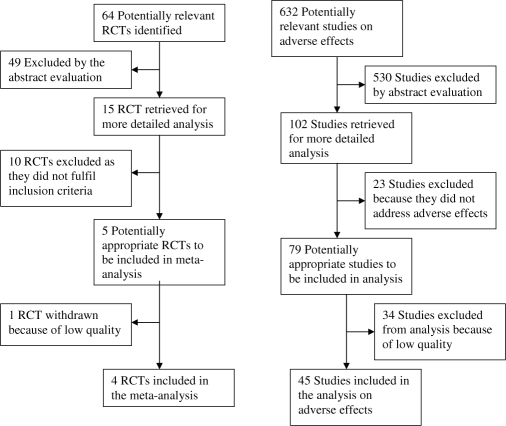

There were 64 hits in the search, and 15 potentially relevant articles were read. Five randomized controlled trials comparing surgery with sham surgery or conservative treatment were identified (Figure 1). One trial comparing uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and conservative treatment was excluded from further analysis due to low quality and a modified JADAD score of 2.16 Four parallel, randomized, controlled trials of high quality met the inclusion criteria, 2 studies investigated the effect of laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty and 2 the effect of radiofrequency ablation (Table 1).17–20

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the process of study selection.

Table 1.

Description of Included Studies of Medium and High Quality

| Source | Location | Study design | Sample size* | Operation | Outcomes | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferguson et al., 200317 | Canada | RCT, parallel | 46 (45) | LAUP | ESS, AHI, SAQLI, Snoring, Side-effects | High |

| Woodson et al., 200318 | USA | RCT, parallel | 60 (52) | TCRAFTA | ESS, AHI, SF36, FOSQ, Side-effects | High |

| Larossa et al., 200419 | Spain | RCT, parallel | 28 (25) | LAUP | ESS, AHI, SF36, Snoring, Complications | High |

| Stuck et al., 200520 | Germany | RCT, parallel | 26 (23) | TCRAFTA | ESS, Snoring, Side- effects | High |

| Studies of adverse effects | ||||||

| Esclamado et al., 198923 | USA | Consecutive patients | 132 | UPPP | Perioperative complications | Medium |

| Harmon et al., 198924 | USA | Consecutive patients | 132 | UPPP | Peri- and postoperative complications | Medium |

| Walker et al., 199625 | USA | Consecutive patients | 275 | LAUP | Postoperative complications | Medium |

| Riley et al., 199726 | USA | Prospective | 182 (182) | Different operations | Postoperative complications | Medium |

| Mickelson et al., 199827 | USA | Consecutive patients | 347 | UPPP | Postoperative complications | Medium |

| Terris et al., 199828 | USA | Consecutive patients | 109 (109) | UPPP | Peri- and postoperative complications | Medium |

| Hultcrantz et al., 199929 | Sweden | Consecutive patients | 55 | UPP | Long-term side-effects | Medium |

| Levring-Jäghagen et al., 199930 | Sweden | Consecutive patients | 76 (68) | UPP | Persistent dysphagia | Medium |

| Powell et al., 199931 | USA | Prospective | 20 (18) | TCRAFTA tongue | Postoperative complications, swallowing function | Medium |

| Remacle et al., 199932 | Belgium | Prospective | 89 | LAUP UPPP | Complications | Medium |

| Boudewyns et al., 200033 | Belgium | Prospective | 103 (44) | TCRAFTA soft palate | Postoperative complications | Medium |

| Coleman et al., 200034 | USA | Prospective | 12 | TCRAFTA soft palate | Postoperative complications | Medium |

| Grontved et al., 200035 | Denmark | Consecutive patients | 69 | UPPP | Complications | Medium |

| Hagert et al., 200036 | Sweden | Consecutive patients | 457 (415) | UPPP LAUP | Long-term side-effects | Medium |

| Hukins et al., 200037 | Australia | Prospective | 20 | TCRAFTA soft palate | Postoperative complications | Medium |

| Li et al., 200038 | USA | Prospective | 22 | TCRAFTA soft palate | Long term side-effects | Medium |

| Osman et al., 200039 | UK | Prospective | 47 (47) | UPPP LAUP | Postoperative complications | Medium |

| Bäck et al.. 200140 | Finland | Prospective | 21 (16) | TCRAFTA soft palate | Postoperative complications | Medium |

| Brown et al., 200141 | Canada | Prospective | 12 | TCRAFTA soft palate | Postoperative complications | Medium |

| Pazos et al., 200142 | USA | Consecutive patients | 30 (30) | TCRAFTA soft palate, tongue | Postoperative complications | Medium |

| Sher et al., 200143 | USA | Prospective | 112 (105) | TCRAFTA soft palate | Postoperative complications | Medium |

| Terris et al., 200145 | USA | Prospective | 23 | TCRAFTA soft palate | Postoperative complications | Medium |

| Woodson et al., 200146 | USA | Prospective | 73 (69) | TCRAFTA tongue | Postoperative complications | Medium |

| Haraldsson et al., 200247 | Sweden | Prospective | 16 | TCRAFTA soft palate | Speech evaluation | Medium |

| Lysdahl et al., 200248 | Sweden | Consecutive patients | 150 (121) | UPPP LAUP | Long-term side-effects | Medium |

| Stuck et al., 200244 | Germany | Prospective | 20 (18) | TCRAFTA soft palate, tongue | Postoperative complications | Medium |

| Berger et al., 200349 | Israel | Prospective | 49 | UPPP LAUP | Early and long-term side-effects | Medium |

| Rombaux et al., 200350 | Belgium | Prospective | 49 | UPPP LAUP TCRAFTA soft palate | Postoperative complications | Medium |

| Said et al., 200351 | USA | Consecutive patients | 50 (39) | TCRAFTA soft palate | Postoperative complications | Medium |

| Jäghagen et al., 200422 | Sweden | Prospective | 46 (42) | UPPP UPP | Swallowing function | High |

| Kezirian et al., 200421 | USA | Prospective | 3130 | UPPP | Postoperative serious side-effects | High |

| Kim et al., 200552 | South Korea | Consecutive patients | 90 | UPPP | Postoperative complications | Medium |

| Li et al.,54 | China | Consecutive patients | 108 | UPPP | Taste disturbances | Medium |

| Pavelec et al., 200653 | Czech Republic | Prospective | 63 | LAUP | Postoperative complications | Medium |

Abbreviations: RCT, randomized, controlled trial; ESS, Epworth sleepiness scale; SF36 Short Form 36; AHI, Apnea-hypopnea index; FOSQ, functional outcome of sleep questionnaire; SAQLI, Calgary Sleep Apnea Quality of Life Index; LAUP, laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty; UPP, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty; UPPP, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty; TCRAFTA, temperature-controlled radiofrequency tissue ablation.

Numbers in parentheses denote the number of patients analyzed after withdrawals.

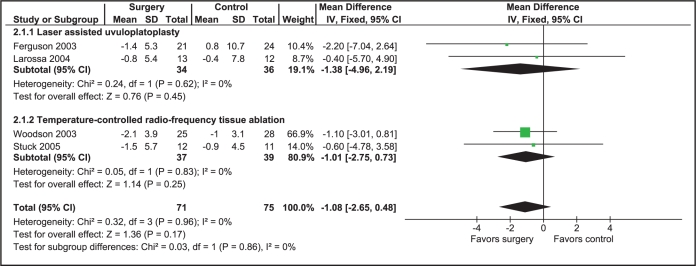

A summary of the effects on outcome for the difference in change is presented in Table 2. These studies show no significant effect on daytime sleepiness measured with the Epworth sleepiness scale after laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty and temperature-controlled, radiofrequency tissue ablation (Figure 2). The apnea-hypopnea index and snoring was reduced in one trial after laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty17 but not in another trial.19 Subjective snoring was reduced, but not the apnea-hypopnea index in one trial after radiofrequency ablation.18 There was no effect on quality of life in any trial. No trial investigating the effect of any other surgical modality met the inclusion criteria.

Table 2.

Effects of Surgery Compared to Placebo or No Treatment

| LAUP Ferguson et al., 200317 | LAUP Larossa et al., 200419 | TCRAFTA Woodson et al., 200318 | TCRAFTA Stuck et al., 200520 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESS | −2.2 (−15, 9.3) | −0.4 (−13, 12) | −1.2 (−3.1, 0.8) | −0.6 (−1.2, 2.3) |

| FOSQ | −0.9 (−0.1, 1.9) | |||

| SAQLI | 0.2 (−0.6, 1.0) | |||

| SF-36 Physical | 1.4 (−38, 41) | −1.0 (−5.1, 3.1) | ||

| SF-36 Mental | −2 (−49, 45) | 2.5 (−1.4, 6.4) | ||

| AHI | −10.5, P = 0.04 | 7 (−76, 90) | −2.7 (−9.9, 4.5) | |

| Snoring intensity | −4.0 (−5.5, −2.5)* | −1.1 (−12, 10) | ||

| Snoring frequency | −3.6 (−1.3, −5.9)* | −106 (−8753, 8541) | ||

| Snoring subjective | −0.5 (−3.8, 2.8) | −2.5 (−4.6, −0.4)* |

Significant as 0 was not included in the confidence interval.

Abbreviations: LAUP, laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty; TCRAFTA, temperature-controlled radiofrequency tissue ablation; ESS, Epworth sleepiness scale; NS, No significant change. SF36 Short Form 36; FOSQ, functional outcome of sleep questionnaire; SAQLI, Calgary Sleep Apnea Quality of Life Index; AHI, Apnea-hypopnea index

Figure 2.

Effect of surgery on daytime sleepiness using the Epworth sleepiness scale.

Laser-Assisted Uvulopalatoplasty

Ferguson et al. randomized 46 snoring patients with an apnea-hypopnea index of between 10 and 27 to laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty or no treatment and followed them for 7 months.17 There was no significant between-group difference in the Epworth Sleepiness Scale or the Calgary Sleep Apnea Quality of Life Index. The mean apnea-hypopnea index was reduced from 19 to 15 in the actively treated patients and increased from 16 to 23 in non-treated patients, P = 0.04 for the between-group difference in change. Snoring intensity estimated by a bedroom partner on a VAS scale from 0–10 was reduced by surgery from a mean of 9.2 to 4.8 and by no treatment from 8.9 to 8.5, P < 0.0001 for the between-group difference in change. Snoring frequency was reduced from a mean of 9.4 to 5.5 in surgically treated patients and from 8.8 to 8.5 in non-treated patients, P < 0.005.

Larossa et al. randomized 28 snoring patients with an apnea-hypopnea index < 30 to laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty or sham surgery and followed them for 3 months.19 They found no significant difference in change in any of the outcomes, i.e. the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, Short-Form 36 Physical component summary, Short-Form 36 Mental component summary, Subjective snoring intensity, Snoring index or Decibels of snoring (Table 2).

Temperature-Controlled Radiofrequency Tissue Ablation

Woodson et al. performed the largest study and randomized 60 patients with daytime sleepiness, an apnea-hypopnea index of 5 to 40 and a body-mass index < 35 kg/m2 to radiofrequency ablation or sham surgery.18 They report that radiofrequency ablation, compared with sham surgery, improved Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire with a mean of 0.9 (95% CI −0.1, 1.9) P = 0.04 and reduced the apnea index with a mean of −4.8 (−9.3, 0.4) P = 0.02. These P-values were, however, significant only in one sided t-test but not in 2-sided nonparametric test, and 0 was included in confidence interval (Table 2). They found no significant difference in change for the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, Short-Form 36 Physical component summary, Short-Form 36 Mental component summary or the apnea-hypopnea index.

Stuck et al. randomized 26 non-sleepy snorers with an apnea-hypopnea index < 15, a body-mass index < 35 kg/m2 and a mean Epworth sleepiness scale of 8.2 (1.4) to temperature-controlled radiofrequency ablation or sham surgery.20 There was no between-group difference in change in the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. The authors report that snoring estimated by a bedroom partner on a VAS scale from 0–10 was reduced by surgery compared with sham surgery from a mean of 8.1 to 5.2 and by sham surgery from 8.4 to 8.0, P = 0.045 for the difference in change.

Adverse Effects

There were 632 hits in the search and 102 potentially relevant articles were read. Seventy-nine trials met the inclusion criteria. Five of the included studies were of high quality,17,18,20–22 and 33 were of medium quality (Table 1).19,23–54. Forty-one studies were of low quality and they were excluded from further analysis, except for 7 studies reporting life-threatening side-effects and deaths55–95 (Figure 1).

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty was followed by severe complications in the peri- and post-operative period, including death, bleedings and respiratory compromise, in 0% to 16% of patients, with higher frequencies in studies published during the 1980s and lower complication frequencies in studies in recent years.21,23,24,26–28,39,50,52,58,60,77,94

A total of 30 cases of death were reported from six studies published between 1989 and 2004 (Table 3). One high-quality study comprising 3,130 operations reported peri- and post-operative death in 0.2% (95% CI 0.1 to 0.4) and serious complications other than death in 1.5% (95% CI 1.1 to1.9).21 Respiratory compromise, bleedings, intubation difficulties, infections, and cardiac arrest were the main causes of death. Persistent side-effects occurred in a mean (range) of 58% (42%–62%) (limited evidence; Table 4).35,36 Difficulty swallowing, including nasal regurgitation, occurred in 31% (13% to 36%) of operated patients (moderate evidence), voice changes in 13% (7% to 14%) (limited evidence), and taste disturbances in 5% (1% to 7%) (limited evidence).22,35,36,48,54 Other reported side-effects were globus sensation, smell disturbances, and single cases of velopharyngeal insufficiency.36,55

Table 3.

Deaths in the Peri- and Postoperative Period

| Author | Operation | Death case numbers | Source population numbers | Reasons for death | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esclamado 198923 | UPPP | 1 | 135 | Intubation problems | Medium |

| USA | |||||

| Harmon 198924 | UPPP | 2 | 132 | Bleeding (n = 1) | Medium |

| USA | Pulmonary embolism (n = 1) | ||||

| Fairbanks 199057 | UPPP | 16 | Bleeding (n = 1) | Low | |

| USA | Loss of airway (n = 12) | ||||

| Unknown (n = 3) | |||||

| Carenfelt 199358 | UPPP | 3 | 9000 | Cardiac arrest (n = 2) | Low |

| Sweden | LAUP | 1 | 2900 | Bleeding (n = 1) | |

| Infection (n = 1) | |||||

| Haavisto 199460 | UPPP | 1 | 101 | Breathing difficulties and asystole (n = 1) | Low |

| Finland | |||||

| Lee 199762 | UPPP or | 6 | Respiratory arrest (n = 1) | Low | |

| UK | LAUP | Cardiac arrest (n = 1) | |||

| Unknown (n = 4) | |||||

| Kezirian 200421 | UPPP | 7 | 3130 | Unknown (n = 4) | High |

| USA | Respiratory problems (n = 2) | ||||

| Cardiac arrest (n = 1) |

Abbreviations: UPPP, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty; LAUP, laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty.

Table 4.

Side-Effects After Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty

| Author | Frequency | Weighted mean | Evidence grade | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persistent side-effects | Hagert 200036 | 62% | 58% | Limited |

| Grontved 200035 | 42% | |||

| Difficulty swallowing | Hagert 200036 | 35% | 31% | Moderate |

| Grontved 200035 | 13% | |||

| Lysdahl 200248 | 36% | |||

| Jäghagen 200422 | 29% | |||

| Voice changes | Hagert 200036 | 14% | 13% | Limited |

| Grontved 200035 | 7% | |||

| Taste disturbances | Hagert 200036 | 7% | 5% | Limited |

| Li 200654 | 1% |

Uvulopalatoplasty

Uvulopalatoplasty performed with a scalpel or laser was followed by peri- and post-operative complications in up to 5%, including post-operative bleedings and infections, with one report of death from septicemia (Tables 3).17,19,25,39,50,58 Persistent side-effects were reported in a mean (range) of 59% (48% to 62%) (limited evidence; Table 5).29,36,49 Difficulty swallowing including nasal regurgitation was reported in 27% (19% to 31%) (strong evidence) and globus sensation in 27% (16% to 36%) (limited evidence).17,22,29,30,32,36,48,53 Other reported side-effects included voice changes, smell disturbances, taste disturbances, and single cases of velopharyngeal stenosis.36,49

Table 5.

Side-Effects After Uvulopalatoplasty

| Author | Frequency | Weighted mean | Evidence grade | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persistent side-effects | Hultcranz 199929 | 56% | 59% | Limited | |

| Hagert 200036 | 62% | ||||

| Berger 200349 | 48% | ||||

| Difficulty swallowing | Levring-Jäghagen 199930 | 20% | 27% | Strong | |

| Hultcranz 199929 | 19% | ||||

| Hagert 200036 | 31% | ||||

| Lysdahl 200248 | 27% | ||||

| Ferguson 200317 | 19% | ||||

| Jäghagen 200422 | 29% | ||||

| Globus sensation in throat | Hultcranz 199929 | 19% | 27% | Limited | |

| Hagert 200036 | 36% | ||||

| Pavelec 200653 | 16% |

Temperature-Controlled Radiofrequency Tissue Ablation

There were no reported changes in speech or swallowing one to two months after surgery.18,20,38,47 Side-effects of temperature-controlled, radiofrequency tissue ablation of the soft palate included hemorrhage, infections and velopharyngeal fistula in single cases.33,50 Radiofrequency ablation of the base of the tongue was followed by severe infections or tongue abscesses in 0% to 8% of patients (moderate evidence).18,31,42,44,46 Single cases of mouth floor edema, severe tongue swelling, and a case of pseudo-aneurysm of the lingual artery and heavy bleeding 14 days after surgery have also been reported.42,44,46,92

Other Surgical Modalities

No studies of any other surgical modality meeting the inclusion criteria for adverse effects were found.

DISCUSSION

Randomized, controlled trials do not support any benefit from surgery in the form of laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty and temperature-controlled radiofrequency tissue ablation when it comes to daytime sleepiness or quality of life. Studies do not provide any evidence of effect on apnea-hypopnea index or snoring as there is a need of at least two trials reporting effect for evidence grading. One study reported a reduction in the apnea-hypopnea index and snoring after laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty, while no such effects were found in another trial. A single study reported a reduction in snoring after radiofrequency tissue ablation. No evidence of effect was established for any other surgical modality, as no randomized, controlled trial meeting the inclusion criteria was found for any other surgical modality. Persistent side-effects were reported in a majority of the patients undergoing uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and uvulopalatoplasty, especially in the form of difficulty swallowing, globus sensation in the throat, and voice changes.

Only four controlled trials randomizing a total of 141 patients to either laser-assisted uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and sham/no treatment, or temperature-controlled radiofrequency tissue ablation and sham surgery met the present inclusion criteria. From this small sample of trials, it is not possible to exclude any effect of surgery. However, the many reports of swallowing difficulties after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and uvulopalatoplasty suggest that other surgical modalities than these two should be further tested. Tonsillectomy is one suggested modality as large tonsils are associated with sleep apnea.96 One disadvantage of surgery, especially more invasive surgery, is the problem of performing placebo or sham surgery in the control group. Instead of placebo, we suggest that control patients should be randomized to delayed surgery. In subsequent systematic reviews we suggest that other quality criteria than pure JADAD should be used in quality assessments. We used a modified JADAD focusing on the quality of single blinding instead of double blinding. If patients and surgeons cannot be blinded, one can always try to blind the assessors.

To date, the best study of peri- and post-operative mortality was published by Kezirian et al. in 2004. They reported a mortality of 0.2% among all Veterans Affairs inpatient uvulopalatopharyngoplasty surgery from 1991 to 2001 and serious peri- and post-operative complications in 1.5% of patients.21 However, without evidence of effects of the surgical procedures, it is difficult to accept mortality related to surgery. Two cohort studies followed long-term mortality after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and they report low mortality in the long term for these patients compared with untreated patients and patients on CPAP.97,98 These studies were, however, not randomized controlled trials, and surgically treated patients were younger and had less comorbidity than those treated with CPAP.

This systematic review included only randomized, controlled trials of medium and high quality regarding the efficacy of surgery. The lack of evidence of benefits of surgery is in agreement with a Cochrane review11 and recent reviews by Elshaug et al.12,14 Only a few randomized controlled trials were, however, available, even though surgery for obstructive sleep apnea was introduced more than 25 years ago. To evaluate adverse effects, we included observational studies of medium and high quality in accordance with the GRADE working group.99 When attempting to estimate the risk of side-effects, sources other than randomized trials have to be searched, since randomized controlled trials are seldom designed to evaluate the risk of side-effects. Observational studies may provide better evidence of rare adverse effects and well-designed case series in particular may provide high-quality evidence of the complication rates for surgery.99 These are the main reasons why different inclusion criteria were used for studies of efficacy and studies of side-effects. With the present design, it was found that the evidence of harm was greater than the evidence of benefits in relation to surgery on the soft palate involving the removal of the uvula, i.e., uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and uvulopalatoplasty.

In conclusion, only a small number of randomized controlled trials with a limited number of patients assessing some surgical modalities for snoring or sleep apnea are available. These studies do not provide any evidence of effect from laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty or radiofrequency ablation on daytime sleepiness, apnea reduction, quality of life or snoring. We call for research of randomized controlled trials of surgery other than uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and uvulopalatoplasty, as they are related to a high risk of long-term side-effects, especially difficulty swallowing.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was performed at the Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care, Stockholm, Sweden. No external funding was obtained. Karl A Franklin is receiving a science award from the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. The Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep. 1999;22:667–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitney CW, Enright PL, Newman AB, Bonekat W, Foley D, Quan SF. Correlates of daytime sleepiness in 4578 elderly persons: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Sleep. 1998;21:27–36. doi: 10.1093/sleep/21.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zielinski J, Zgierska A, Polakowska M, et al. Snoring and excessive daytime somnolence among Polish middle-aged adults. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:946–50. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14d36.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, Lichtman JH, Brass LM, Mohsenin V. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2034–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sahlin C, Sandberg O, Gustafson Y, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is a risk factor for death in patients with stroke: a 10-year follow-up. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:297–301. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valham F, Mooe T, Rabben T, Stenlund H, Wiklund U, Franklin KA. Increased risk of stroke in patients with coronary artery disease and sleep apnea: a 10-year follow-up. Circulation. 2008;118:955–60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.783290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young T, Finn L, Peppard PE, et al. Sleep disordered breathing and mortality: eighteen-year follow-up of the Wisconsin sleep cohort. Sleep. 2008;31:1071–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall NS, Wong KK, Liu PY, Cullen SR, Knuiman MW, Grunstein RR. Sleep apnea as an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality: the Busselton Health Study. Sleep. 2008;31:1079–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujita S, Conway W, Zorick F, Roth T. Surgical correction of anatomic azbnormalities in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1981;89:923–34. doi: 10.1177/019459988108900609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Littner M, Kushida CA, Hartse K, et al. Practice parameters for the use of laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty: an update for 2000. Sleep. 2001;24:603–19. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sundaram S, Bridgman SA, Lim J, Lasserson TJ. Surgery for obstructive sleep apnoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001004.pub2. CD001004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elshaug AG, Moss JR, Southcott AM, Hiller JE. Redefining success in airway surgery for obstructive sleep apnea: a meta analysis and synthesis of the evidence. Sleep. 2007;30:461–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.4.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.SBU. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering (SBU); 2007. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Report of a joint Nordic project. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elshaug AG, Moss JR, Hiller JE, Maddern GJ. Upper airway surgery should not be first line treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea in adults. BMJ. 2008;336:44–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39381.509213.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Controlled clinical trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lojander J, Maasilta P, Partinen M, Brander PE, Salmi T, Lehtonen H. Nasal-CPAP, surgery, and conservative management for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. A randomized study. Chest. 1996;110:114–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferguson KA, Heighway K, Ruby RR. A randomized trial of laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty in the treatment of mild obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:15–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2108050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woodson BT, Steward DL, Weaver EM, Javaheri S. A randomized trial of temperature-controlled radiofrequency, continuous positive airway pressure, and placebo for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128:848–61. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59980300461-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larrosa F, Hernandez L, Morello A, Ballester E, Quinto L, Montserrat JM. Laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty for snoring: does it meet the expectations? Eur Respir J. 2004;24:66–70. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00082903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stuck BA, Sauter A, Hormann K, Verse T, Maurer JT. Radiofrequency surgery of the soft palate in the treatment of snoring. A placebo-controlled trial. Sleep. 2005;28:847–50. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.7.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kezirian EJ, Weaver EM, Yueh B, et al. Incidence of serious complications after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:450–3. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200403000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaghagen EL, Berggren D, Dahlqvist A, Isberg A. Prediction and risk of dysphagia after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and uvulopalatoplasty. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124:1197–203. doi: 10.1080/00016480410017954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esclamado RM, Glenn MG, McCulloch TM, Cummings CW. Perioperative complications and risk factors in the surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:1125–9. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198911000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harmon JD, Morgan W, Chaudhary B. Sleep apnea: morbidity and mortality of surgical treatment. South Med J. 1989;82:161–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walker RP, Gopalsami C. Laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty: postoperative complications. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:834–8. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199607000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C, Pelayo R, Troell RJ, Li KK. Obstructive sleep apnea surgery: risk management and complications. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:648–52. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mickelson SA, Hakim I. Is postoperative intensive care monitoring necessary after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;119:352–6. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(98)70077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terris DJ, Fincher EF, Hanasono MM, Fee WE, Jr, Adachi K. Conservation of resources: indications for intensive care monitoring after upper airway surgery on patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:784–8. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199806000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hultcrantz E, Johansson K, Bengtson H. The effect of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty without tonsillectomy using local anaesthesia: a prospective long-term follow-up. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:542–7. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100144445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levring-Jäghagen E, Nilsson ME, Isberg A. Persisting dysphagia after uvulopalatoplasty performed with steel scalpel. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:86–90. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199901000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Powell NB, Riley RW, Guilleminault C. Radiofrequency tongue base reduction in sleep-disordered breathing: A pilot study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120:656–64. doi: 10.1053/hn.1999.v120.a96956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Remacle M, Betsch C, Lawson G, Jamart J, Eloy P. A new technique for laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty: decision-tree analysis and results. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:763–8. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199905000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boudewyns A, Van De Heyning P. Temperature-controlled radiofrequency tissue volume reduction of the soft palate (somnoplasty) in the treatment of habitual snoring: results of a European multicenter trial. Acta Otolaryngol. 2000;120:981–5. doi: 10.1080/00016480050218735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coleman SC, Smith TL. Midline radiofrequency tissue reduction of the palate for bothersome snoring and sleep-disordered breathing: A clinical trial. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:387–94. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(00)70054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grøntved AM, Karup P. Complaints and satisfaction after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Acta Oto-laryngologica. 2000;543:190–2. doi: 10.1080/000164800454369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hagert B, Wikblad K, Odkvist L, Wahren LK. Side effects after surgical treatment of snoring. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2000;62:76–80. doi: 10.1159/000027721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hukins CA, Mitchell IC, Hillman DR. Radiofrequency tissue volume reduction of the soft palate in simple snoring. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:602–6. doi: 10.1001/archotol.126.5.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li KK, Powell NB, Riley RW, Troell RJ, Guilleminault C. Radiofrequency volumetric reduction of the palate: An extended follow-up study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:410–4. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(00)70057-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osman EZ, Osborne JE, Hill PD, Lee BW, Hammad Z. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty versus laser assisted uvulopalatoplasty for the treatment of snoring: an objective randomised clinical trial. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2000;25:305–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2000.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Back L, Palomaki M, Piilonen A, Ylikoski J. Sleep-disordered breathing: radiofrequency thermal ablation is a promising new treatment possibility. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:464–71. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200103000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown DJ, Kerr P, Kryger M. Radiofrequency tissue reduction of the palate in patients with moderate sleep-disordered breathing. J Otolaryngol. 2001;30:193–8. doi: 10.2310/7070.2001.19696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pazos G, Mair EA. Complications of radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of sleep-disordered breathing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:462–6. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.119863. discussion 6-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sher AE, Flexon PB, Hillman D, et al. Temperature-controlled radiofrequency tissue volume reduction in the human soft palate. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:312–8. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.119141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stuck BA, Maurer JT, Verse T, Hormann K. Tongue base reduction with temperature-controlled radiofrequency volumetric tissue reduction for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002;122:531–6. doi: 10.1080/00016480260092354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Terris DJ, Chen V. Occult mucosal injuries with radiofrequency ablation of the palate. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:468–72. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.119864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woodson BT, Nelson L, Mickelson S, Huntley T, Sher A. A multi-institutional study of radiofrequency volumetric tissue reduction for OSAS. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:303–11. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.118958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haraldsson PO, Karling J, Lysdahl M, Svanborg E. Voice quality after radiofrequency volumetric tissue reduction of the soft palate in habitual snorers. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1260–3. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200207000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lysdahl M, Haraldsson PO. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty versus laser uvulopalatoplasty: prospective long-term follow-up of self-reported symptoms. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002;122:752–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berger G, Stein G, Ophir D, Finkelstein Y. Is there a better way to do laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:447–53. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rombaux P, Hamoir M, Bertrand B, Aubert G, Liistro G, Rodenstein D. Postoperative pain and side effects after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty, and radiofrequency tissue volume reduction in primary snoring. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:2169–73. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200312000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Said B, Strome M. Long-term results of radiofrequency volumetric tissue reduction of the palate for snoring. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112:276–9. doi: 10.1177/000348940311200315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim JA, Lee JJ, Jung HH. Predictive factors of immediate postoperative complications after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1837–40. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000173199.57456.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pavelec V, Polenik P. Use of Er,Cr:YSGG versus standard lasers in laser assisted uvulopalatoplasty for treatment of snoring. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1512–6. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000227958.81725.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li HY, Lee LA, Wang PC, et al. Taste disturbance after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:985–90. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Katsantonis GP, Friedman WH, Krebs FJ, 3rd, Walsh JK. Nasopharyngeal complications following uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 1987;97:309–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Croft CB, Golding-Wood DG. Uses and complications of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. The J Laryngol Otol. 1990;104:871–5. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100114215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fairbanks DN. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty complications and avoidance strategies. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;102:239–45. doi: 10.1177/019459989010200306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carenfelt C, Haraldsson PO. Frequency of complications after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Lancet. 1993;341:437. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)93030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stepnick DW. Management of total nasopharyngeal stenosis following UPPP. Ear Nose Throat J. 1993;72:86–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haavisto L, Suonpaa J. Complications of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1994;19:243–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1994.tb01224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jackson IT, Kenedy D. Surgical management of velopharyngeal insufficiency following uvulopalatopharyngoplasty: report of three cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:1151–3. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199704000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee WC, Skinner DW, Prichard AJ. Complications of palatoplasty for snoring or sleep apnoea. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111:1151–4. doi: 10.1017/s002221510013957x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coleman JA., Jr Laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty: long-term results with a treatment for snoring. Ear Nose Throat J. 1998;77(22-4, 6-9):32–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Isberg A, Levring-Jäghagen E, Dahlström M, Dahlqvist Å. Persistent dysphagia after laser uvulopalatoplasty: a videoradiographic study of pharyngeal function. Acta Otolaryngol. 1998;118:870–4. doi: 10.1080/00016489850182602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.O'Reilly BF, Simpson DC. A comparison of conservative, radical and laser palatal surgery for snoring. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1998;43:194–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pinczower EF. Globus sensation after laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty. Am J Otolaryngol. 1998;19:107–8. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(98)90104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Powell NB, Riley RW, Troell RJ, Li K, Blumen MB, Guilleminault C. Radiofrequency volumetric tissue reduction of the palate in subjects with sleep-disordered breathing. Chest. 1998;113:1163–74. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.5.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tytherleigh MG, Thomas MA, Connolly AA, Bridger MW. Patients' and partners' perceptions of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for snoring. J Otolaryngol. 1999;28:73–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tegelberg Å, Wilhelmsson B, Walker-Engström ML, et al. Effects and adverse events of a dental appliance for treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea. Swed Dent J. 1999;23:117–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Andsberg U, Jessen M. Eight years of follow-up--uvulopalatopharyngoplasty combined with midline glossectomy as a treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Acta Oto-laryngologica. 2000;543:175–8. doi: 10.1080/000164800454323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Emery BE, Flexon PB. Radiofrequency volumetric tissue reduction of the soft palate: a new treatment for snoring. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1092–8. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200007000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ferguson M, Smith TL, Zanation AM, Yarbrough WG. Radiofrequency tissue volume reduction: multilesion vs single-lesion treatments for snoring. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:1113–8. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.9.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Blumen MB, Dahan S, Fleury B, Hausser-Hauw C, Chabolle F. Radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:2086–92. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200211000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Finkelstein Y, Stein G, Ophir D, Berger R, Berger G. Laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty for the management of obstructive sleep apnea: myths and facts. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:429–34. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.4.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Walker-Engstrom ML, Tegelberg A, Wilhelmsson B, Ringqvist I. 4-year follow-up of treatment with dental appliance or uvulopalatopharyngoplasty in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized study. Chest. 2002;121:739–46. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.3.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fischer Y, Khan M, Mann WJ. Multilevel temperature-controlled radiofrequency therapy of soft palate, base of tongue, and tonsils in adults with obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1786–91. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200310000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gessler EM, Bondy PC. Respiratory complications following tonsillectomy/UPPP: is step-down monitoring necessary? Ear Nose Throat J. 2003;82:628–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Isono S, Shimada A, Tanaka A, Ishikawa T, Nishino T, Konno A. Effects of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty on collapsibility of the retropalatal airway in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:362–7. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200302000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li HY, Li KK, Chen NH, Wang PC. Modified uvulopalatopharyngoplasty: The extended uvulopalatal flap. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003;24:311–6. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(03)00047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Riley RW, Powell NB, Li KK, Weaver EM, Guilleminault C. An adjunctive method of radiofrequency volumetric tissue reduction of the tongue for OSAS. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:37–42. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59980300482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stuck BA, Starzak K, Verse T, Hormann K, Maurer JT. Complications of temperature-controlled radiofrequency volumetric tissue reduction for sleep-disordered breathing. Acta Otolaryngol. 2003;123:532–5. doi: 10.1080/00016480310001385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tatla T, Sandhu G, Croft CB, Kotecha B. Celon radiofrequency thermo-ablative palatoplasty for snoring - a pilot study. J Laryngol Otol. 2003;117:801–6. doi: 10.1258/002221503770716241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kamel UF. Hypogeusia as a complication of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and use of taste strips as a practical tool for quantifying hypogeusia. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124:1235–6. doi: 10.1080/00016480410016892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kania RE, Schmitt E, Petelle B, Meyer B. Radiofrequency soft palate procedure in snoring: influence of energy delivered. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kieff DA, Busaba NY. Same-day discharge for selected patients undergoing combined nasal and palatal surgery for obstructive sleep apnea. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113:128–31. doi: 10.1177/000348940411300209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Madani M. Complications of laser-assisted uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (LA-UPPP) and radiofrequency treatments of snoring and chronic nasal congestion: a 10-year review of 5,600 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:1351–62. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.05.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Uppal S, Nadig S, Jones C, Nicolaides AR, Coatesworth AP. A prospective single-blind randomized-controlled trial comparing two surgical techniques for the treatment of snoring: laser palatoplasty versus uvulectomy with punctate palatal diathermy. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2004;29:254–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2004.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jones LM, Guillory VL, Mair EA. Total nasopharyngeal stenosis: treatment with laser excision, nasopharyngeal obturators, and topical mitomycin-c. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:795–8. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kezirian EJ, Powell NB, Riley RW, Hester JE. Incidence of complications in radiofrequency treatment of the upper airway. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1298–304. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000165373.78207.BF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Spiegel JH, Raval TH. Overnight hospital stay is not always necessary after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:167–71. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000150703.36075.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hathaway B, Johnson JT. Safety of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty as outpatient surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:542–4. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Herzog M, Schmidt A, Metz T, et al. Pseudoaneurysm of the lingual artery after temperature-controlled radiofrequency tongue base reduction: a severe complication. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:665–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000200795.12919.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Iyngkaran T, Kanagalingam J, Rajeswaran R, Georgalas C, Kotecha B. Long-term outcomes of laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty in 168 patients with snoring. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120:932–8. doi: 10.1017/S002221510600209X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pang KP. Identifying patients who need close monitoring during and after upper airway surgery for obstructive sleep apnoea. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120:655–60. doi: 10.1017/S0022215106001617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Roosli C, Schneider S, Hausler R. Long-term results and complications following uvulopalatopharyngoplasty in 116 consecutive patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:754–8. doi: 10.1007/s00405-006-0051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dahlqvist J, Dahlqvist A, Marklund M, Berggren D, Stenlund H, Franklin KA. Physical findings in the upper airways related to obstructive sleep apnea in men and women. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:623–30. doi: 10.1080/00016480600987842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Marti S, Sampol G, Munoz X, et al. Mortality in severe sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome patients: impact of treatment. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:1511–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00306502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Weaver EM, Maynard C, Yueh B. Survival of veterans with sleep apnea: continuous positive airway pressure versus surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:659–65. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ Clinical research ed. 2004;328:1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]