Abstract

Background

The renal (kNBC1) and intestinal (pNBC1) electrogenic Na+/HCO3- cotransporter variants differ in their primary structure, transport direction, and response to secretagogues. Previous studies have suggested that regulatory differences between the two subtypes can be partially explained by unique consensus phosphorylation sites included in the pNBC1, but not the kNBC1 sequence. After having shown activation of NBC by carbachol and forskolin in murine colon, we now investigated these pathways in HEK293 cells transiently expressing a GFP-tagged pNBC1 construct.

Results

Na+- and HCO3--dependent pHi recovery from an acid load (measured with BCECF) was enhanced by 5-fold in GFP-positive cells compared to the control cells in the presence of CO2/HCO3-. Forskolin (10-5 M) had no effect in untransfected cells, but inhibited the pHi recovery in cells expressing pNBC1 by 62%. After preincubation with carbachol (10-4 M), the pHi recovery was enhanced to the same degree both in transfected and untransfected cells, indicating activation of endogenous alkalizing ion transporters. Acid-activated Na+/HCO3- cotransport via pNBC1 expressed in renal cells is thus inhibited by cAMP and not affected by cholinergic stimulation, as opposed to the findings in native intestinal tissue.

Conclusion

Regulation of pNBC1 by secretagogues appears to be not solely dependent on its primary structure, but also on properties of the cell type in which it is expressed.

Background

The electrogenic Na+/HCO3--cotransporter isoform 1 (NBC1) is basolaterally expressed in the renal proximal tubule, where it mediates HCO3- reabsorption by concerted action with the apical Na+/H+-exchanger isoform NHE3 [1], and in gastrointestinal epithelia, where it serves the intracellular supply of HCO3- destined for secretion [2]. These striking differences in function and transport direction have prompted studies to elucidate the structural and regulatory properties of the respective transporters. It was found that renal NBC is inhibited by an increase in intracellular cAMP [1], enabling the parallel regulation with NHE3, which is also inhibited in a cAMP-dependent manner [3]. In contrast, we could previously show that forskolin stimulates intestinal NBC [4]. However, exposure to cholinergic compounds causes an increase of both the renal and the intestinal Na+/HCO3- cotransporter rates [5,6].

One explanation for the differential regulation of Na+/HCO3- cotransport in these tissues comes from the identification of structurally distinct splice variants of NBC1. The renal (kNBC1) and intestinal (pNBC1) NBC subtypes possess a common C-terminal PKA-dependent phosphorylation site (Ser982 and Ser1026, respectively), which was reported to determine transport stoichiometry in renal cells [7,8]. In addition, however, the longer N-terminal tail of pNBC1 contains unique phosphorylation sites for PKA (Thr49), PKC (Ser38 and Ser65), and casein kinase II (Ser68), which are not found in the kNBC1 sequence and of which at least the cAMP-dependent site is relevant for transporter regulation [7,9].

On the other hand, there is increasing evidence that the cell type plays a central role in determining how ion transport is regulated [10-13]. As knowledge of intestinal Na+/HCO3- cotransporter function and regulation is overall limited, this important aspect has not been studied in great detail. There is only one report on cAMP-dependent stoichiometry changes of heterologously transfected pNBC1 involving the common C-terminal phosphorylation site [7]. However, information on cell-type dependency of intestinal NBC regulation by secretagogues during its presumed physiological function, which is HCO3- uptake in the process of anion secretion [2], is lacking. We therefore set off to investigate HCO3- import via pNBC1 transfected into HEK293 cells in acidification experiments. The aim of the study was to clarify whether regulation of heterologously transfected pNBC1 by secretagogues is similar as in native colonic tissue and thus essentially dependent on structural determinants of the transporter protein, or different and thus affected by the cell type in which it is expressed.

Results

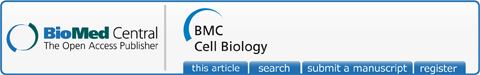

To determine the distribution of NBC1 subtypes in HEK293 cells compared to native tissue, we first performed PCR analysis (Figure 1). Neither pNBC1 nor kNBC1 mRNA was amplified from untransfected HEK293 cells. As anticipated, pNBC1-specific primers detected a signal in HEK293 cells transiently transfected with pNBC1, and in human colon. kNBC1 was detected in human kidney and, to a lesser degree, in human colon samples.

Figure 1.

RT-PCR in untransfected HEK293 cells (HEK293), HEK293 cells transiently transfected with pNBC1 (+pNBC1), as well as human kidney and colon samples using kNBC1- and pNBC1-specific primers (see methods section). While neither isoform was detected in untransfected HEK293 cells, a pNBC1 fragment of the expected size (612 bp) was amplified from transfected HEK293 cells and human colon. kNBC1 was exclusively detected in human kidney samples (expected PCR product size: 489 bp). H2O indicates the reaction where water was used as a template.

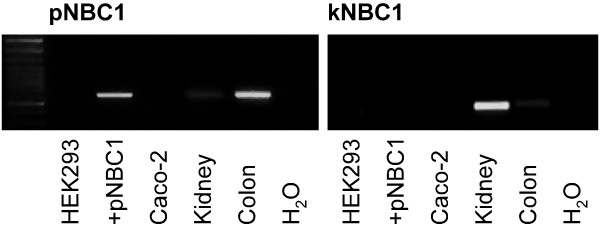

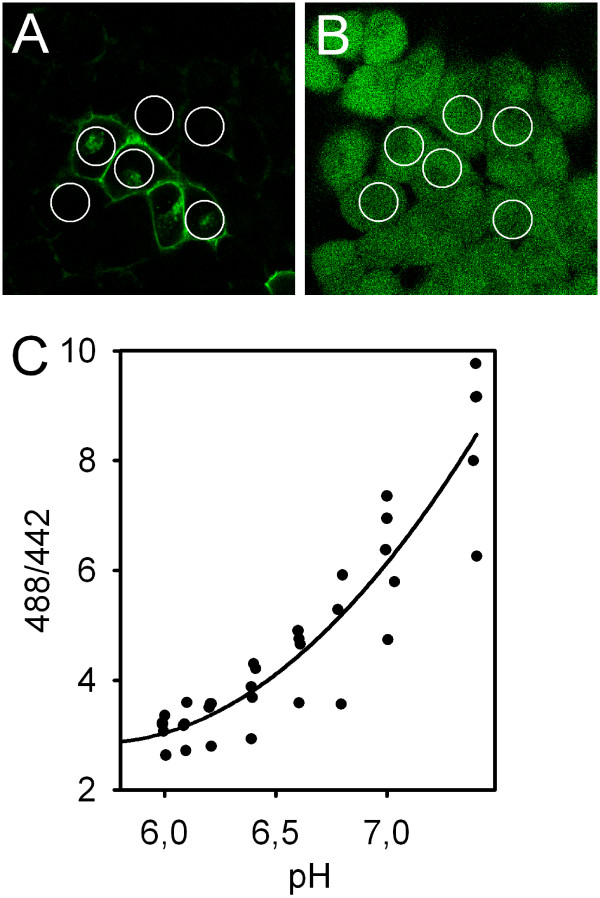

Next, transiently transfected HEK293 cells were visualized using confocal microscopy (Figure 2A). The transfection efficiency was consistently at 10–15% of the cells. After selecting regions of interest (ROIs) covering the major part of the cytoplasm, the image was digitized for documentation, and cells were in situ loaded with BCECF (Figure 2B). Two groups of cells were identified: Cells with a strong GFP signal along the cell membrane (subsequently called "GFP-positive" or "transfected"), and cells with no or very faint fluorescence in this location (subsequently called "GFP-negative" or "untransfected"). To exclude cells with intermediate GFP signal which only weakly express the transfected construct, the signal was quantified by placing a rectangular plot profile with vertical averaging over at least 20 pixels (for noise reduction) perpendicularly over the cell membrane using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) under standardized illumination settings [14]. Indeed, the first group of cells exhibited fluorescence intensity values of 98.8 ± 14.2 AU (arbitrary units), and the second group values of 17.0 ± 3.1 AU (p < 0.01 vs. first group, not significantly different from the background); the amount of cells with intermediate GFP signal was low (<10%), and these cells were not used for the functional experiments. Cells were then subjected to an NH4+-prepulse protocol to impose an acid load in the presence of CO2/HCO3- (Figure 3C). It is important to note in this context that the high pHi values achieved during the prepulse are overestimated, since our calibration approach is optimized for the low pHi values where transporter activity is actually measured. pHi recovery upon readdition of Na+ occurred faster in GFP-positive than in GFP-negative cells. Since the steady-state pHi appeared to be higher in transfected cells, we statistically compared the obtained values from untransfected and transfected cells, which indeed demonstrated a significantly more alkaline pHi in pNBC1-transfected cells, pointing to increased basal NBC activity (Figure 3A). The reference pHi, however, was not significantly different between the two (Figure 3B). Overall, the correlation between GFP signal intensity and recovery rates were excellent, demonstrating the correct identification of the transfected cells. The resting pHi and the reference pHi of mock-transfected cells were equal as in untransfected cells (not shown).

Figure 2.

Confocal images of HEK cells transiently transfected with GFP-pNBC1. Panel (A) shows the GFP staining of transfected cells and the weak autofluorescence of untransfected cells. After placing regions of interest covering most of the cytosol, cells were in situ loaded with the pH-sensitive dye BCECF (B), and the time course of the intracellular pH was recorded. C: To determine the optimal calibration procedure for the pH range of interest (for calculation of the recovery rates at the reference pHi, see Fig. 3B), a calibration curve was constructed using high K+/nigericin solution to clamp intracellular pH at different levels. As expected, its slope is less steep at low pHi values and steeper in the linear range (n = 6). To minimize the error during the calibration procedure within the pH range of interest, the calibration points 6.2 and 7.0 were chosen. Since the ratio values varied considerably between the experiments, each individual region was calibrated after the respective experiment subsequently.

Figure 3.

Starting pHi, reference pHi, and representative pHi tracings from pNBC1-transfected and untransfected HEK293 cells. A, B: Box and whisker diagram of the starting- and reference pHi values from pNBC1-transfected and untransfected cells. Steady-state pHi was significantly higher in transfected cells, pointing to increased baseline Na+/HCO3- cotransport activity (*: p < 0.001, Student's t-test for paired samples, n = 7). The reference pHi after acidification was, however, not different between the two. C: After imposing an acid load using the "NH4-prepulse" method, cells acidified to a similar extent. Upon Na+ readdition, most untransfected cells showed no significant recovery, while pHi increased rapidly in transfected cells (representative tracings). It should be noted that our 2-point calibration approach is optimized for the low pHi values at which transporter activity is measured, and that the higher pHi values are therefore overestimated.

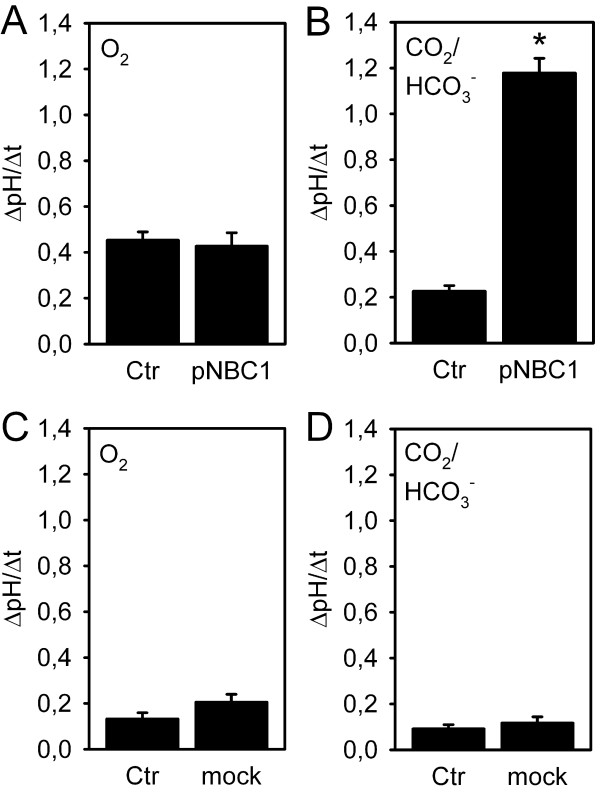

To determine whether pNBC1 transfected in HEK293 cells is functional, pHi recovery rates were quantified in untransfected and transfected cells in the presence and absence of CO2/HCO3- (Figure 4). In HEPES buffered solution, no significant difference in ΔpH/Δt was observed, indicating no Na+/HCO3--cotransport in HEK293 cells due to the lack of substrate (A). The alkalization under these conditions is most likely mediated by the Na+/H+-exchanger, of which the NHE1 and NHE3 isoforms are expressed in HEK293 cells [15,16]. In the presence of CO2/HCO3-, however, pHi recovery occurred significantly faster at a 5-fold higher rate in transfected vs. untransfected cells (B). This finding clearly demonstrates successful functional transfection of pNBC1. ΔpH/Δt appeared somewhat lower in untransfected cells in the presence than in the absence of CO2/HCO3-, probably due to a higher buffering capacity in its presence, but this difference did not reach statistical significance. To exclude that the GFP signal significantly influences the recovery rates, control experiments using mock-transfected HEK cells were carried out (C, D). Here, recovery rates were generally low, and not significantly different between mock-transfected vs. untransfected in the presence and absence of CO2/HCO3-, respectively.

Figure 4.

pHi recovery from an acid load in untransfected (Ctr) and transfected cells (pNBC1, mock) in the absence and presence of CO2/HCO3-. A: in O2/HEPES buffer, no significant difference in the pHi recovery rate in untransfected and pNBC1-transfected cells was noted (n = 8). B: In the presence of CO2/HCO3-, however, pHi was accelerated 5-fold in transfected vs. untransfected HEK293 cells (*: p < 0.05, Student's t-test for paired samples, n = 7), indicating successful functional transfection of the pNBC1 protein. C, D: in mock-transfected vs. untransfected cells on the same slide, pHi recovery rates were relatively low, and no significant differences were noted between mock-transfected and untransfected, or between the absence and presence of CO2/HCO3-, respectively (n = 6–8).

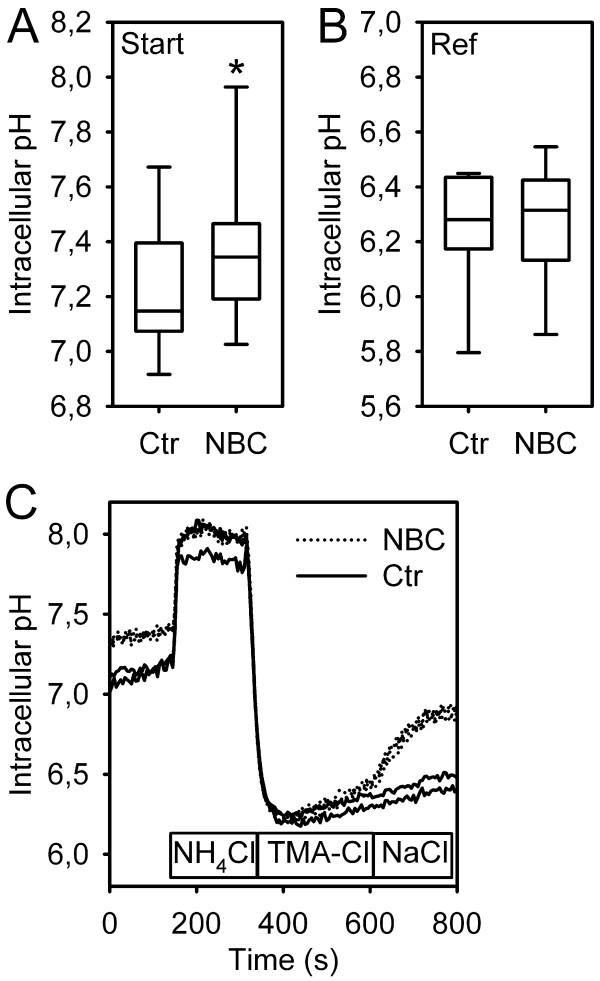

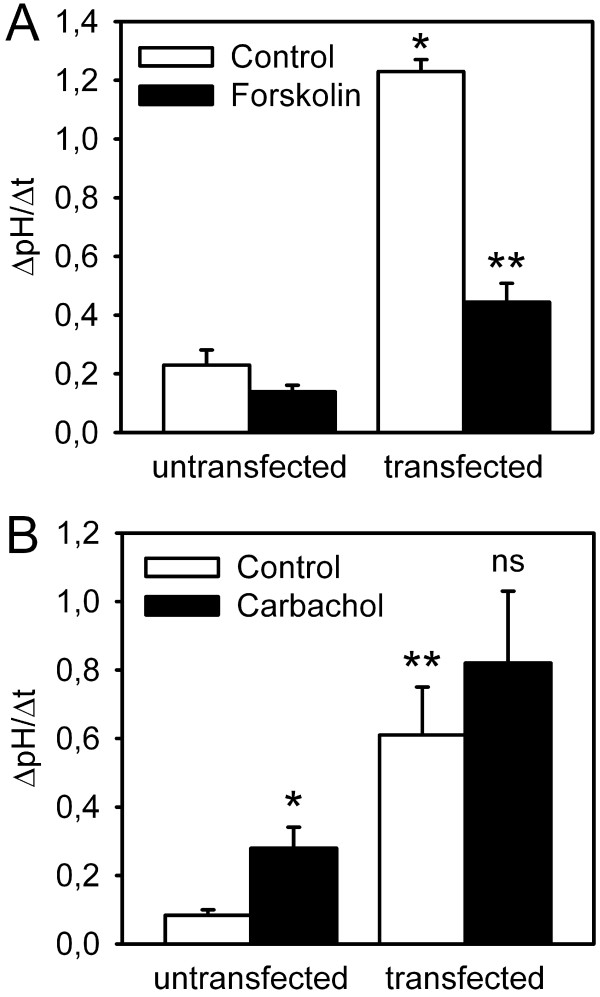

In our previous work, we had delineated the effects of secretagogues on endogenous Na+/HCO3--cotransport, which is most likely effectuated predominantly by the pNBC1 subtype of the electrogenic isoform NBC1, in murine proximal colonic crypts. In accordance with the concept of NBC as an anion importer during cAMP-dependent and cholinergic stimulation of anion secretion, we could demonstrate transporter activation by both types of secretagogues [4,6]. We now set off to investigate the influence of the cell type on cotransporter regulation by secretagogues, and therefore studied the effect of forskolin and carbachol on pNBC1 transfected into HEK293 cells as a non-intestinal cellular model. As depicted in figure 5A, an increase in intracellular cAMP did not significantly change pHi recovery rates in untransfected cells, indicating that this measure possibly causes differential, and balanced effects on the Na+/H+ exchanger isoforms expressed in HEK293 cells [15,16] and/or on endogenous NBC. However, forskolin stimulation significantly decreased pHi recovery rate in pNBC1-transfected HEK293 cells by more than 50%, which is in sharp contrast to the findings in native tissue [4,7].

Figure 5.

Effect of cAMP-dependent and cholinergic stimulation on pHi recovery in untransfected and pNBC1-transfected HEK293 cells. A: Forskolin did not elicit any significant changes in pHi recovery in untransfected cells (n = 6). Again, transfected cells displayed a significantly faster pHi recovery under control conditions than their untransfected counterparts (*: p < 0.05 vs. untransfected control, Student's t-test for paired samples, n = 6). However, forskolin strongly inhibited pHi recovery in pNBC1-transfected HEK293 cells (**: p < 0.01 vs. unstimulated control, Student's t-test for unpaired samples, n = 7). B: Carbachol caused a slight acceleration of pHi recovery in untransfected cells, which might be due to effects on endogenous Na+/H+ exchange or on Na+/HCO3- exchanger isoforms other than pNBC1 or kNBC1 (*: p < 0.05 vs. unstimulated control, Student's t-test for unpaired samples, n = 6). pNBC1 transfection again led to a significantly faster pHi recovery (**: p < 0.05 vs. untransfected control, Student's t-test for paired samples, n = 8). However, carbachol did not cause any additional significant changes to pHi recovery in transfected cells (ns: not significant, n = 8).

HEK293 cells have been shown functionally express the M3 subtype of cholinergic receptors [17], which mediates NBC activation by carbachol in murine colonic crypts [6]. When untransfected cells were subjected to cholinergic stimulation, ΔpH/Δt was increased compared to the control, which points to the activation of NHE1 which is expressed in HEK293 cells. In pNBC1-transfected cells, however, carbachol had no additional stimulatory impact on pHi recovery and did not cause changes in pHi recovery altogether (Figure 5B). Given its effect on untransfected cells, carbachol does not stimulate NBC, but might even have an inhibitory effect on this transport system. This finding represents another discrepancy of endogenous intestinal versus heterologously transfected pNBC1 regulation [6].

Discussion

The renal and intestinal Na+/HCO3- cotransporters are differentially regulated by cAMP-dependent and cholinergic agonists [1,4-6]. Possible explanations for these findings are differences in their primary structure influencing regulatory properties, or features of the cell type in which they are expressed. In this study, we investigated the secretagogue regulation of the intestinal-pancreatic NBC subtype pNBC1 in HEK293 cells.

The group of Ira Kurtz has thoroughly studied the stoichiometry of NBC1 and found that the renal subtype kNBC1 is transporting 1 Na+ and 3 HCO3- with each cycle, which results in outward-directed transport [8]. Functional inhibition of kNBC1 by cAMP is probably in part due to a stoichiometry shift from 3:1 to 2:1, leading to a switch from export to import. On the other hand, the intestinal subtype pNBC1 serves the uptake of both ions with a 2:1 ratio under physiological conditions [18], and a stoichiometry change was not reported for the endogenously expressed transporter. However, pNBC1 can be activated via cAMP [4], which is due to the phosphorylation of a unique consensus phosphorylation site in its N-terminus [7]. As to a structure-function relationship regarding cholinergic stimulation, which increases the transport rate of both subtypes in a PKC-dependent manner [5,6], the possible relevance of the unique PKC-dependent phosphorylation site in the pNBC1 N-terminus remains to be assessed.

Importantly, cell type- and tissue-specific regulation has been recognized for many ion transporters including Na+/H+-exchange [10,11], anion exchange [12], and CFTR [13]. Expression of pNBC1 and kNBC1 is not restricted to the pancreas/intestinal tract and the kidney, respectively, and expression in other organs such as the eye [19], the gallbladder [20], and salivary glands [21] has been reported, but it has not been investigated whether these different cell types modulate transporter regulation. Gross et al. have previously studied the regulation of murine pNBC1 endogenously occurring in pancreatic duct cells and heterologously transfected into a mouse proximal tubule cell line [7]. They found that cAMP causes upregulation of endogenous pNBC1 via one PKA-dependent phosphorylation site not present in the kNBC1 sequence, while changing the stoichiometry from 3:1 to 2:1 and thereby transport direction via another common C-terminal site (Ser982 and Ser1026 for kNBC1 and pNBC1, respectively), the latter resembling kNBC1 regulation. In our experiments, however, we sought to clarify the cell-type dependency of the regulation of the presumed physiological function of pNBC1, which is HCO3- uptake during stimulated anion secretion, and which can be activated by imposing an acid load on the cytosol. In this setting of inward transport, stoichiometry would be expected to be already 2:1 [8], and there is no evidence that secretagogues can reverse it to 3:1 in either of the NBC1 subtypes. Accordingly, Pedrosa et al. did not find any influence of cAMP stimulation on kNBC1 in renal cells in pHi recovery experiments [22]; however, it is under debate whether kNBC1 can be a relevant base loader under physiological conditions, a recent study suggesting rather an adaptation of the pNBC1 and kNBC1 expression pattern in renal and submandibular gland epithelia during acid-base disturbances [23]. The differential regulation of SLC4 gene family members in different cell types might be related to possibly specialized roles of the transporters in the respective tissues (e. g. vectorial transport vs. homeostatic functions), but this aspect of NBC function is yet poorly understood.

With respect to the HEK293 cells used in the current study, transfection studies investigating human heart (hhNBC) or renal NBC did not reveal any endogenous expression of the these isoforms by immunoblotting [24,25]. In their functional experiments, one group reported Na+- and HCO3--dependent pHi recovery after an acid load, which could be due to NHE or NBC [24], while another group described no recovery in the additional presence of amiloride, arguing against the presence of endogenous NBC [26]. In support of these findings, the recovery rates we measured in untransfected cells in the presence of CO2/HCO3- were very low, and, although not statistically comparable since measured in a different experiment, not higher than in its absence. Therefore, the transfection-independent recovery rate is most likely due to endogenous Na+/H+ exchangers, of which the NHE1 and NHE3 isoforms have previously been detected in HEK293 cells [15,16]. Since recovery rates were considerably lower in untransfected vs. transfected cells in the presence of CO2/HCO3- (Figure 4B), no attempt was made to pharmacologically inhibit the presumably relatively low endogenous transporter activities in the subsequent experiments. One limitation of the present study is therefore the lack of information on potential effects of carbachol and forskolin on endogenous base loading mechanisms.

The transfection efficiency was relatively low under all conditions we tried, e. g. serum free/serum containing media, lipophilic agents, or calcium precipitation. Furthermore, a suitable transfection system to serve as a control is not available, since the intestinal cell lines Caco-2 and HT-29 show endogenous NBC activities which are not well molecularly characterized [27-29], T84 cells express kNBC1 rather than pNBC1 (B. Bridges, communication), and our attempts to transfect pNBC1 into Caco-2 or T84 cells did not yield sufficient overexpression to achieve unequivocal results. One possible reason for the overall low transfection efficiency could be that NBC increases intracellular pHi above the optimum for cellular metabolism. However, the pHi changes we measured were minor, and the acidification of cytosolic pH by lowering medium pH did not improve NBC abundance (data not shown). More likely, transfection efficiency is limited by the large size of the GFP-pNBC1 transcript. To differentiate between transfected and untransfected cells in this setting, the fluorescence signal of the GFP tag was visualized using confocal microscopy. Since the C-terminal phosphorylation site was characterized as a crucial regulatory sequence which explains the regulation of kNBC1 and pNBC1 in renal cells [7,8], it appeared reasonable to tag the pNBC1 N-terminus to avoid interference of the tag with this sequence. Nevertheless, we observed an inhibition of NBC after preincubation with forskolin, which cannot be readily explained by the N-terminal GFP tag. However, we cannot exclude that the GFP tag interferes with the binding site for IRBIT close to the N-terminus (see below), which could in part explain our results with carbachol.

The molecular basis for the differential regulation of pNBC in intestinal vs. HEK293 cells remains unknown. The observed acid-induced NBC activity in HEK293 cells under basal conditions and the strong inhibitory effect of forskolin are difficult to reconcile with mere stoichiometry changes as described by Gross et al. [7], since they would further increase HCO3- import and thus accelerate pHi recovery. Possibly, the signal transduction machinery of the cell types provides an explanation. One could speculate about a possible role of associated proteins, such as NHERF (NHE regulatory factor) family members, IRBIT (IP3R binding protein released with IP3), and carbonic anhydrase. NHERF has been shown to be necessary for cAMP-dependent inhibition of renal NBC; however, no binding, NBC phosphorylation or change in NBC surface expression were observed [30,31]. As another regulatory protein, IRBIT was found to bind to pNBC1, but not kNBC1, and pNBC1 transfected into X. oocytes only attains functional activity comparable to the one of transfected kNBC1 when IRBIT is co-transfected [32]. IRBIT is expressed in the kidney [33], while its presence in HEK293 cells and the intestinal tract has not yet been clarified. Furthermore, carbonic anhydrase, of which several isoforms are differentially expressed in the kidney and the gastrointestinal tract [34], could potentially influence NBC transport capacity by HCO3- generation, but its functional relevance for NBC regulation is highly controversial at present [35-37].

Conclusion

In summary, we succeeded in functionally transfecting GFP-pNBC1 into HEK293 cells, thereby providing a non-intestinal cellular model to study its regulation. Na+/HCO3--cotransporter response to secretagogues in this system was strikingly different from our previous findings in native murine colon. This suggests a relevance of cellular factors, possibly associated proteins, in addition to structural features of this NBC1 variant. The characterization of the involved molecular mechanisms requires further studies.

Methods

Construction of tagged full-length pNBC1

Full-length pNBC1 was generated by PCR, using the following sense and antisense primers: 5'-GAATTCAGGATGGAGGATGAAGCTGTCCTG-3' and 5'-AGCGGCCGCCTCAGCATGATGTGTGGCGTTCAAGGAATGT-3', respectively, based on the pancreatic NBC1 cDNA (AF069510). The amplified wild-type NBC1 DNA was fused translationally in-frame to green fluorescent protein (GFP) by cloning into pcDNA3.1/NT-GFP-TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany).

Transient expression of epitope-tagged pNBC1 in HEK293 cells

Transfection of HEK293 cells (purchased from the European Collection of Cell Cultures at passage 59) grown to 50% confluence on 35 mm tissue culture plates was performed either with the calcium phosphate method following Jordan et al. [38] using 6 μg expression construct DNA per dish, or with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions using 4 μg expression construct DNA and 12 μl Lipofectamine per dish for the pNBC1 construct (2 μg and 8 μl for the vector alone).

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for pNBC1 and kNBC1

The primers used for amplifying pNBC1 and kNBC1 were deduced from published sequence information [9,26], and from PCR protocols with murine samples [18] (5'-ATGTGTGTGATGAAGAAGAAGTAGAAG-3' and 5'-CACTGAAAATGTGGAAGGGAAG-3', respectively, as well as the common antisense primer 5'-GACCGAAGGTTGGATTTCTTG-3'). The following conditions were used for PCR: denature 94°C, 30 s; anneal 58°C, 30 s; extend 72°C, 180 s; for 30 cycles.

Determination of NBC activity by confocal microscopy

Transiently transfected HEK293 cells grown on a glass coverslip were transferred to a custom-made perfusion chamber and mounted on the heated stage of a fixed-stage upright confocal microscope (Leica DM LFSA, Leica TCS SP2 AOBS, Leica Microsystems, Bensheim, Germany) 48–72 h post transfection. After documentation of the GFP fluorescence, cells were loaded with 5 μM BCECF for 30 minutes in buffer A (120 NaCl, 14 HEPES, 7 TRIS, 3 KH2PO4, 2 K2HPO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 Ca2+-gluconate, 20 glucose, pH 7.4, gassed with 100% O2), and subsequently perfused with 95% O2/5% CO2-gassed buffers (buffer B: 20 mM NaCl of buffer A were replaced by NaHCO3; buffer C: 40 mM NaCl of buffer B were replaced by NH4Cl; buffer D: NaCl of buffer A was replaced by tetramethyl-ammonium chloride) following the respective protocol. The fluorescence ratio was recorded during alternating excitation with a 442 nm diode-pumped solid-state (DPSS) laser system and the 488 nm line of the built-in argon laser. The system's Acousto-Optical Beam Splitter (AOBS) was set to an emission range of 525 ± 10 nm. Subsequent 2-point calibration (pH 6.2 and 7.0) was carried out using the high-K+-nigericin method as described previously [6] to enable calculation of pHi from the ratio values for each individual ROI. These calibration points were chosen since the primary aim was to measure the steep initial pHi recovery rate from the reference pHi (Fig. 3B), and the slope of the calibration curve was found to be less steep in this pH range (Fig. 2C). GFP fluorescence was negligible compared to the BCECF signal (<1%).

Materials

2'-7'-bis-carboxyethyl-5,6-carboxyfluorescein acetoxymethyl ester (BCECF/AM) was purchased from Invitrogen (Karlsruhe, Germany), and cell culture media (DMEM) as well as fetal calf serum from Fluka (Seelze, Germany). Forskolin, carbachol and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Seelze, Germany), and were either of cell culture grade or the highest grade available.

Statistics

Results of the pHi recovery rates are given as means± SE (standard error), except for the box plot shown in figure 3 displaying the median and quartiles. Since transfected and untransfected cells were measured on the same plate in each individual experiment, statistical testing between the two was carried out using student's t-test in its paired form; otherwise, its unpaired form was used. For the calculation of standard errors and for statistics, n = 1 was defined as the mean of all ROIs (transfected or untransfected) from one experiment.

Authors' contributions

OB participated in the design and the coordination of the study, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. KF carried out the transfections, the initial PCR assays, and the fluorometric experiments. HY performed the final PCR assays and participated in the fluorometric experiments. BR participated in optimizing the PCR and the transfection. HCL and MS cloned the expression construct. MPM participated in the coordination of the study. US participated in the design of the study and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Georg Lamprecht and Florian Kühnel for helpful discussions. This study was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG Ba 2114/5-1 and -3), and a grant from the Lower Saxony ministry of science and culture (Niedersachsen-VW-Vorab) (to US). KF and HY were funded by DFG Ba 2114/5-1 and -3.

Contributor Information

Oliver Bachmann, Email: bachmann.oliver@mh-hannover.de.

Kristin Franke, Email: kristin.franke@charite.de.

Haoyang Yu, Email: guixuanyu@gmail.com.

Brigitte Riederer, Email: riederer.brigitte@mh-hannover.de.

Hong C Li, Email: hong.li@uc.edu.

Manoocher Soleimani, Email: Manoocher.Soleimani@uc.edu.

Michael P Manns, Email: manns.michael@mh-hannover.de.

Ursula Seidler, Email: seidler.ursula@mh-hannover.de.

References

- Ruiz OS, Arruda JA. Regulation of the renal Na-HCO3 cotransporter by cAMP and Ca-dependent protein kinases. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:F560–F565. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.262.4.F560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob P, Christiani S, Rossmann H, Lamprecht G, Vieillard-Baron D, Muller R, et al. Role of Na(+)HCO(3)(-) cotransporter NBC1, Na(+)/H(+) exchanger NHE1, and carbonic anhydrase in rabbit duodenal bicarbonate secretion. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:406–419. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.9358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun CH, Oh S, Zizak M, Steplock D, Tsao S, Tse CM, et al. cAMP-mediated inhibition of the epithelial brush border Na+/H+ exchanger, NHE3, requires an associated regulatory protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3010–3015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann O, Rossmann H, Berger UV, Colledge WH, Ratcliff R, Evans MJ, et al. cAMP-mediated regulation of murine intestinal/pancreatic Na+/HCO3-cotransporter subtype pNBC1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G37–G45. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00209.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz OS, Qiu YY, Cardoso LR, Arruda JA. Regulation of the renal Na-HCO3 cotransporter: VII. Mechanism of the cholinergic stimulation. Kidney Int. 1997;51:1069–1077. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann O, Reichelt D, Tuo B, Manns MP, Seidler U. Carbachol increases Na+-HCO3-cotransport activity in murine colonic crypts in a M3-, Ca2+/calmodulin-, and PKC-dependent manner. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G650–G657. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00376.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross E, Fedotoff O, Pushkin A, Abuladze N, Newman D, Kurtz I. Phosphorylation-induced modulation of pNBC1 function: distinct roles for the amino- and carboxy-termini. J Physiol. 2003;549:673–682. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.042226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross E, Kurtz I. Structural determinants and significance of regulation of electrogenic Na(+)-HCO(3)(-) cotransporter stoichiometry. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;283:F876–F887. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00148.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abuladze N, Lee I, Newman D, Hwang J, Boorer K, Pushkin A, et al. Molecular cloning, chromosomal localization, tissue distribution, and functional expression of the human pancreatic sodium bicarbonate cotransporter. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17689–17695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtazina R, Kovbasnjuk O, Zachos NC, Li X, Chen Y, Hubbard A, et al. Tissue specific regulation of sodium-proton exchanger isoform 3 (NHE3) activity in NA/H exchanger regulatory factor 1 (NHERF1) null mice: cAMP inhibition is differentially dependent on NHERF1 and exchange protein directly activated by cAMP(EPAC) in ileum versus proximal tubule. J Biol Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701910200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moe OW, Miller RT, Horie S, Cano A, Preisig PA, Alpern RJ. Differential regulation of Na/H antiporter by acid in renal epithelial cells and fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1703–1708. doi: 10.1172/JCI115487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossmann H, Bachmann O, Wang Z, Shull GE, Obermaier B, Stuart-Tilley A, et al. Differential expression and regulation of AE2 anion exchanger subtypes in rabbit parietal and mucous cells. J Physiol. 2001;534:837–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulka M, Dery R, Nahirney D, Duszyk M, Befus AD. Differential regulation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator by interferon gamma in mast cells and epithelial cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:563–570. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.087528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinar A, Chen M, Riederer B, Bachmann O, Wiemann M, Manns M, et al. NHE3 inhibition by cAMP and Ca2+ is abolished in PDZ-domain protein PDZK1-deficient murine enterocytes. J Physiol. 2007;581:1235–1246. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.131722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang K, Wagner C, Haddad G, Burnekova O, Geibel J. Intracellular pH activates membrane-bound Na(+)/H(+) exchanger and vacuolar H(+)-ATPase in human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2003;13:257–262. doi: 10.1159/000074540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby D, Masada N, Crossthwaite AJ, Ciruela A, Cooper DM. Localized Na+/H+ exchanger 1 expression protects Ca2+-regulated adenylyl cyclases from changes in intracellular pH. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30864–30872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414355200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Busillo JM, Benovic JL. M3 Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor-Mediated Signaling is Regulated by Distinct Mechanisms. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:338–347. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.044750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross E, Abuladze N, Pushkin A, Kurtz I, Cotton CU. The stoichiometry of the electrogenic sodium bicarbonate cotransporter pNBC1 in mouse pancreatic duct cells is 2 HCO(3)(-):1 Na(+) J Physiol. 2001;531:375–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0375i.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok D, Schibler MJ, Pushkin A, Sassani P, Abuladze N, Naser Z, et al. Immunolocalization of electrogenic sodium-bicarbonate cotransporters pNBC1 and kNBC1 in the rat eye. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;281:F920–F935. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.5.F920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser AJ, Gangopadhyay A, Bradbury NA, Peters KW, Frizzell RA, Bridges RJ. Electrogenic bicarbonate secretion by prairie dog gallbladder. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G1683–G1694. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00268.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YB, Yang BH, Piao ZG, Oh SB, Kim JS, Park K. Expression of Na+/HCO3-cotransporter and its role in pH regulation in mouse parotid acinar cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;304:593–598. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00632-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrosa R, Goncalves N, Hopfer U, Jose PA, Soares-da-Silva P. Activity and Regulation of Na+-HCO3-Cotransporter in Immortalized Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat and Wistar-Kyoto Rat Proximal Tubular Epithelial Cells. Hypertension. 2007;49:1186–1193. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.083444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandes A, Oehlke O, Schumann A, Heidrich S, Thevenod F, Roussa E. Adaptive redistribution of NBCe1-A and NBCe1-B in rat kidney proximal tubule and striated ducts of salivary glands during acid-base disturbances. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R2400–R2411. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00208.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandoudi N, Albadine J, Robert P, Krief S, Berrebi-Bertrand I, Martin X, et al. Inhibition of the cardiac electrogenic sodium bicarbonate cotransporter reduces ischemic injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;52:387–396. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(01)00430-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt BM, Biemesderfer D, Romero MF, Boulpaep EL, Boron WF. Immunolocalization of the electrogenic Na+-HCO-3 cotransporter in mammalian and amphibian kidney. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:F27–F38. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.1.F27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlal H, Wang Z, Burnham C, Soleimani M. Functional characterization of a cloned human kidney Na+:HCO3-cotransporter. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16810–16815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osypiw JC, Gleeson D, Lobley RW, Pemberton PW, McMahon RF. Acid-base transport systems in a polarized human intestinal cell monolayer: Caco-2. Exp Physiol. 1994;79:723–739. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1994.sp003803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez MA, Toriano R, Parisi M, Malnic G. Control of cell pH in the T84 colon cell line. J Membr Biol. 2000;177:149–157. doi: 10.1007/s002320001108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JX, Yang N, He Q, Tsang LL, Zhao WC, Chung YW, et al. Differential Cl- and HCO3-mediated anion secretion by different colonic cell types in response to tetromethylpyrazine. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1763–1768. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i12.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo AA, Kear FT, Santos AV, Ma J, Steplock D, Robey RB, et al. Basolateral Na(+)/HCO(3)(-) cotransport activity is regulated by the dissociable Na(+)/H(+) exchanger regulatory factor. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:195–201. doi: 10.1172/JCI5344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinman EJ, Evangelista CM, Steplock D, Liu MZ, Shenolikar S, Bernardo A. Essential role for NHERF in cAMP-mediated inhibition of the Na+-HCO3-co-transporter in BSC-1 cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42339–42346. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106153200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirakabe K, Priori G, Yamada H, Ando H, Horita S, Fujita T, et al. IRBIT, an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-binding protein, specifically binds to and activates pancreas-type Na+/ Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9542–9547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602250103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando H, Mizutani A, Matsu-ura T, Mikoshiba K. IRBIT, a novel inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptor-binding protein, is released from the IP3 receptor upon IP3 binding to the receptor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:10602–10612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210119200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purkerson JM, Schwartz GJ. Expression of membrane-associated carbonic anhydrase isoforms IV, IX, XII, and XIV in the rabbit: induction of CA IV and IX during maturation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R1256–R1263. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00735.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez BV, Loiselle FB, Supuran CT, Schwartz GJ, Casey JR. Direct extracellular interaction between carbonic anhydrase IV and the human NBC1 sodium/bicarbonate co-transporter. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12321–12329. doi: 10.1021/bi0353124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HM, Deitmer JW. Carbonic anhydrase II increases the activity of the human electrogenic Na+/HCO3-cotransporter. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13508–13521. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piermarini PM, Kim EY, Boron WF. Evidence against a direct interaction between intracellular carbonic anhydrase II and pure C-terminal domains of SLC4 bicarbonate transporters. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1409–1421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608261200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan M, Schallhorn A, Wurm FM. Transfecting mammalian cells: optimization of critical parameters affecting calcium-phosphate precipitate formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:596–601. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.4.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]