Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the kinetics of lymphocyte proliferation during primary infection of macaques with pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) and to study the impact of short-term postexposure highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) prophylaxis. Twelve macaques were infected by intravenous route with SIVmac251 and given treatment for 28 days starting 4 h postexposure. Group 1 received a placebo, and groups 2 and 3 received combinations of zidovudine (AZT), lamivudine (3TC), and indinavir. Macaques in group 2 received AZT (4.5 mg/kg of body weight), 3TC (2.5 mg/kg), and indinavir (20 mg/kg) twice per day by the oral route whereas macaques in group 3 were given AZT (4.5 mg/kg) and 3TC (2.5 mg/kg) subcutaneously twice per day, to improve the pharmacokinetic action of these drugs, and a higher dose of indinavir (60 mg/kg). The kinetics of lymphocyte proliferation were analyzed by monitoring 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) uptake ex vivo and by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis. HAART did not protect against SIV infection but did strongly impact on virus loads: viremia was delayed and lowered during antiviral therapy in group 2, with better control after treatment was stopped, and in group 3, viremia was maintained at lower levels during treatment, with virus even undetectable in the blood of some macaques, but there was no evidence of improved control of the virus after treatment. We provide direct evidence that dividing NK cells are detected earlier than dividing T cells in the blood (mostly in CD45RA− T cells), mirroring plasma viremia. Dividing CD8+ T cells were detected earlier than dividing CD4+ T cells, and the highest percentages of proliferating T cells coincided with the first evidence of partial control of peak viremia and with an increase in the percentage of circulating gamma interferon-positive CD8+ T cells. The level of cell proliferation in the blood during SIV primary infection was clearly associated with viral replication levels because the inhibition of viral replication by postexposure HAART strongly reduced lymphocyte proliferation. The results and conclusions in this study are based on experiments in a small numbers of animals and are thus preliminary.

The immune response initiated during primary human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection fails to prevent the establishment of chronic infection. However, early immune effectors may make a significant contribution to partial control of the initial burst of viremia, possibly affecting long-term clinical outcome (27, 30, 31). Thus, an understanding of the mechanisms underlying the initial immune events of primary HIV infection is essential for the development of effective AIDS prophylaxis strategies, and for the development of vaccines in particular.

Present knowledge of the dynamics of the T-cell response to viral infections is largely restricted to studies in mice with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, gamma-herpesvirus, or influenza virus infections (5, 8, 22, 34, 65). In these models, the initial immune response involves considerable antigen (Ag)-driven activation and expansion of effector CD8+ T-cell populations. During virus clearance, a large proportion of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) undergo apoptosis, to be replaced by long-lasting memory cells, which provide a faster and more effective response to reinfection or virus rebound.

Little is known about the dynamics of the immunological events occurring in the first few days of HIV infection, probably because it is difficult to obtain biological material from humans shortly after contamination and due to the lack of appropriate small-animal models. CTL directed against HIV type 1 (HIV-1) are detectable during the first few weeks of infection and are associated with a decrease in viremia and viral set point (3, 20, 35). In macaques infected with pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), virus-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes are detected as early as 4 to 6 days after inoculation with the virus (63), which suggests that they are critical in the control of the initial burst of viral replication (16). Although this temporal association is not sufficient to determine cause or effect, these results are in accordance with the fact that the experimental depletion of CD8+ cells in macaques during primary infection with SIV prevents efficient control of viral load (45).

Virological and immunological events during primary infection may determine disease progression in the long term (23, 31). Studies in macaques have confirmed that, as in humans, viral RNA levels during the first few weeks after inoculation with the virus are predictive of disease progression (27, 47, 59). We recently reported that a combination of zidovudine (AZT), lamivudine (3TC), and indinavir, given orally as soon as 4 h after intravenous inoculation with pathogenic SHIV89.6P and maintained for 4 weeks, did not prevent infection but significantly decreased plasma viral load and did prevent dramatic decrease of CD4 counts, even in the long term (25, 48). Our results confirmed previous observations that a good clinical prognosis is correlated with low viremia or a lack of detection of virus in the peripheral blood and lymph nodes (12) after postexposure prophylaxis or early immunotherapy in infant or adult macaques (53, 54). Early down regulation of viral replication may also improve antiviral immune response. Indeed, chemotherapy during the acute phase of pathogenic SIV infection not only persistently decreases viral load but is also associated with a high frequency of strong SIV-specific lymphocyte proliferative responses. Such responses are correlated with protection against subsequent challenge, mimicking the effects of vaccination with live attenuated SIV (28, 44). In humans, the administration of potent antiviral therapy in the earliest stages of acute HIV-1 infection has led to persistent, strong HIV-1-specific T-helper cell responses, analogous to those seen in individuals able to control viremia without antiviral therapy (42).

Although we still have no vaccine to prevent HIV infection, the immunity induced in macaques by prototype vaccines has been shown to decrease the initial SIV or simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) viremia peak, and this is associated with clinical benefits in the long term (2, 46, 58).

Thus, an understanding of the kinetics of expansion of populations of T cells, NK cells, and B cells early after infection may shed light on the forces driving the long-term control of virus replication. It is also essential for the development of future efficient prophylactic strategies aimed at preventing HIV infection or rapid disease progression. During primary SIVmac infection in rhesus monkeys, it was recently concluded from Ki67 labeling experiments that the transient increase in the number of proliferating cells concerns mostly NK cells and CD8+ T cells, with little or no increase in CD4+ T-cell proliferation (18). The kinetics of proliferating T cells appeared to be related to the kinetics of SIV replication. In this context, Ki67+ T cells were mostly activated memory T cells, and the oligoclonal expansion of the proliferating CD8+ T-cell population suggests that this expansion is Ag specific.

In this study, we investigated the kinetics of lymphocyte proliferation and activation in cynomolgus macaques during primary infection with pathogenic SIVmac and the effects of early chemotherapy on the dynamics of T-cell population expansion during treatment and in the long term. We monitored lymphocyte proliferation by monitoring the ex vivo incorporation of 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) into lymphocyte DNA. We felt that this approach was more appropriate than classical intracellular detection of Ki67, the expression of which increases during the G1, S, G2, and M stages of the cell cycle, probably resulting in overestimation of the number of proliferating cells. BrdU is incorporated into mononuclear cell (MNC) DNA, therefore making it possible to estimate directly the percentages and absolute numbers of lymphocytes processing through S phase. We provide direct evidence that dividing NK (CD8+ CD3−) cells are detected earlier than dividing CD8+ CD3+ and CD4+ CD3+ T cells in the blood, mirroring the plasma viremia burst. Furthermore, dividing CD8+ T cells were detected before dividing CD4+ T cells, during T-cell population expansion. The highest percentages of proliferating T cells coincided temporally with partial control of peak viremia and with an increase in the percentage of circulating gamma interferon-positive (IFN-γ+) CD8+ T cells. Levels of cell proliferation in the blood during SIV primary infection were clearly associated with viral replication levels because the inhibition of viral replication by postexposure highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) strongly reduced lymphocyte proliferation. Furthermore, the most effective antiviral regimen, which kept viral load levels very low during treatment and was associated with reduced cell proliferation, led to a poor outcome when treatment was stopped compared to the less effective treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Twelve adult cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis), each weighing 4 to 6 kg, were imported from Mauritius. They were housed in single cages within level 3 biosafety facilities. All animals used in this study tested negative for SIV, simian T-lymphotropic virus, herpes B virus, filovirus, simian retrovirus 1, simian retrovirus 2, measles, hepatitis B virus HBsAg, and hepatitis B virus HBcAb, at the beginning of the study. All experimental procedures were conducted according to European guidelines for animal care (“Journal Officiel des Communautés Européennes,” L358, 18 December 1986). The animals were sedated with ketamine chlorhydrate (Rhone-Mérieux, Lyon, France), before virus injection, blood sample collection, and treatment.

Virus inoculation.

Macaques were inoculated, via the saphenous vein, with 50% animal infectious doses (50 AID50) of a cell-free virus stock of pathogenic SIVmac251 (kindly provided by A. M Aubertin, Université Louis Pasteur, Strasbourg, France) in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Virions were obtained from the cell-free supernatant of infected rhesus peripheral blood MNCs (PBMC). Cells were infected in vitro with a culture supernatant obtained from a coculture of rhesus PBMC and a spleen homogenate from a rhesus macaque infected with SIVmac251 (provided by R. C. Desrosiers, New England Regional Primate Center, Southborough, Mass.). The stock was titrated after intravenous, intrarectal, and intravaginal inoculation (24, 36). We checked that this virus stock was susceptible in vitro to AZT, 3TC, and indinavir: each compound, at a concentration of 50 nM, alone or in combination, inhibited SIVmac251 replication by over 90% in a human PBMC culture assay (data not shown).

Treatment of animals.

Four monkeys (group 2) received AZT (4.5 mg/kg of body weight), 3TC (2.5 mg/kg), and indinavir (20 mg/kg) twice per day by the oral route, through a nasogastric catheter, as described elsewhere (25, 48). Four macaques (group 3) were given AZT (4.5 mg/kg) and 3TC (2.5 mg/kg) subcutaneously twice per day, to improve the pharmacokinetic action of these drugs (unpublished results), and a higher dose of indinavir (60 mg/kg), orally, twice per day. Treatment was initiated 4 h after virus exposure and was continued for 4 weeks. Four macaques were treated with placebo given orally and subcutaneously (group 1).

T-lymphocyte subset determination.

PBMC were analyzed by flow cytometry, using a direct immunofluorescence assay to determine the percentages of CD4+ CD8+ T lymphocytes. We incubated 3 × 105 PBMC at 4°C for 30 min with anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (MAb) (FN-18) (Biosource International, Camarillo, Calif.) and anti-CD4 MAb (Leu3a-phycoerythrin) (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- and phycoerythrin-conjugated immunoglobulins G1 (Immunotech, Marseille, France) were used as controls. Stained cells were washed twice in PBS and fixed (Cell-fix; Becton Dickinson). T-lymphocyte subsets were analyzed with a FACScan cytometer, using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson).

Plasma viral load determination.

Viral RNA was isolated from 200 μl of plasma collected into EDTA-containing vials, according to the instructions provided by the kit manufacturer (High Pure viral RNA kit; Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and stored frozen at −80°C. Viral RNA was quantified using an in-house viral RNA quantification technique (57). Briefly, 10 μl of the isolated RNA was subjected to reverse transcription and PCR for amplification of a region of gag. The reaction mixture contained 25 IU of murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Roche); 0.2 mM dATP, dCTP, and dGTP; 0.19 mM dTTP; 0.01 mM digoxigenin (DIG)-11-dUTP (PCR DIG labeling mix; Roche), 2 IU of RNase inhibitor (RNasin; Promega, Madison, Wis.); 0.5 IU of Taq DNA polymerase (Roche); and 20 nM (each) primers 5′-GTGCTGTTGGTCTACTTGTTTTTG-3′ and 5′-ATGTAGTATGGGCAGCAAATGAAT-3′, with the final volume being made up to 50 μl with H2O. The amplification was performed in a Crocodile III thermocycler (Appligene, Illkirch, France): heating at 42°C for 25 min and then at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 35 s, 60°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 1 min; the mixture was then heated at 60°C for 5 min and finally at 72°C for 5 min.

We quantified 10 μl of the amplification product by anti-DIG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (PCR enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay DIG detection; Roche), according to the manufacturer's instructions, using the following probe at a 20 nM concentration: 5′-CATTTGGATTAGCAGAAAGCCTGTTGGAGAACAAAGAAGGATGTCAA-3′. Samples were tested in duplicate, and two 1/10 dilutions were tested for each sample. As a positive control, we used a plasma sample previously quantified by two different approaches (reverse transcription-PCR and bDNA; Bayer Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The standard was a culture supernatant containing free SIVmac251 aliquoted and diluted in plasma from a seronegative macaque collected in EDTA. The limit of quantification of this method was 40 RNA copies/ml of plasma. Under this limit, although the method is not quantitative, positivity reflects the presence of virus in the plasma at a concentration below 40 copies/ml. The concentration of virus in the standard was estimated by two different approaches (quantitative reverse transcription-PCR and bDNA assay; Bayer).

Cell-associated virus load.

DNA was extracted from lymph node MNCs with a commercial kit (High Pure PCR template preparation kit; Roche Diagnostics). A series of 1/5 DNA dilutions were used for the first round of amplification with gag-specific primers (1386-, 5′-GAAACTATGCCAAAAACAAGT, and 2129, 5′-TAATCTAGCCTTCTGTCCTGG). The initial dilution tested contained 1 μg of tissue DNA in 10 μl. The reaction mixture contained diluted DNA and 1 U of Taq polymerase (Appligene), in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3)-1.5 mM MgCl2-50 mM KCl-0.1% Triton X-100-5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Appligene)-30 pmol of each primer, with the final volume made up to 100 μl with H2O. Amplification was performed in a Crocodile III thermocycler (Appligene). The DNA was denatured by heating for 3 min at 94°C. It was then subjected to 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 45 s, annealing at 56°C for 2 min, and extension at 72°C for 1.5 min. The reaction mixture was then heated at 72°C for 10 min.

Nested PCR was performed with 3 μl of the product from the first amplification reaction and was carried out with two internal primers: 1731N, 5′-CCGTCAGGATCAGATATTGCAGGAA, and 2042C, 5′-CACTAGCTTGCAATCTGGGTT. Amplification was performed as follows, using a reaction mixture identical to that for the first round of amplification, but in a final volume of 50 μl: denaturation at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 25 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 45 s, annealing at 56°C for 1.5 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min. The reaction mixture was then heated for 10 min at 72°C.

The number of copies of viral DNA was determined from the last dilution that gave a positive signal following electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. The standard consisted of DNA extracted from SIVmac251-infected CEMX174 cells containing known numbers of viral DNA copies. Results are expressed as arithmetic means of duplicates for each sample and indicate the number of SIV DNA copies per microgram of total tissue DNA.

T-cell proliferation assay.

Blood MNCs were obtained by centrifugation on a Ficoll density gradient. Red blood cells were then lysed by exposure for 5 min to hypotonic shock, and PBMC were washed twice in PBS. Cells were then stimulated, in triplicate, in flat-bottomed 96-well plates, with 10 μg of recombinant SIV p27Gag (kindly provided by N. Winter, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France)/ml or with concanavalin A, as a positive control. Thymidine was incorporated on day 3 for concanavalin A-stimulated PBMC and on day 5 for SIV p27Gag-stimulated PBMC. Results are expressed as stimulation indices (SI = mean counts for p27-stimulated wells/mean count for control wells without Ag). Proliferative responses to p27 were considered positive both if the mean count for triplicate wells stimulated with p27 exceeded 538 cpm [mean of all preinfection counts + (2.02 × standard deviation)] and if the SI exceeded 3.02 [mean of all preinfection p27 indices + (2.02 × standard deviation)].

Intracellular BrdU immunostaining.

The incorporation of BrdU into lymphocytes ex vivo was measured as previously described (49). It has been shown that the proportion of dividing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells determined by this method correlates well with the peak fraction of T cells labeled in vivo after a 30-min infusion of BrdU in patients with HIV infection (26). This correlation has also been demonstrated in mice, during response to bacterial enterotoxins (55).

Briefly, PBMC or lymph node MNCs were incubated overnight in 1 mg of BrdU (Sigma)/ml in culture medium, Glutamax supplemented with 10% heat-decomplemented fetal calf serum and antibiotics. The MNCs were then surface stained with various combinations of fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies: anti-CD3 (Clinisciences)-anti-CD8 (Becton Dickinson)-anti-CD4 (Becton Dickinson), anti-CD3-anti-CD8-anti-CD45RA (Becton Dickinson), anti-CD3-anti-CD8-anti-CD28 (Becton Dickinson), and anti-CD3-anti-CD20 (Immunotech). Surface-stained MNCs were then incubated at 4°C for 48 to 72 h in 1% paraformaldehyde (Sigma)-0.01% Tween 20 (Sigma) in PBS for fixation and permeabilization. BrdU was finally detected by the DNase method (29), with an FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody (Becton Dickinson). Four-color-stained MNCs were then analyzed in a Becton Dickinson FACScalibur cytometer, using Cell Quest software.

Baseline levels of proliferating PBMC were measured in the 12 macaques, at six time points during the year preceding infection. Proliferating cells consistently accounted for less than 0.5% of the population of each type of lymphocyte (median ± standard deviation of median: 0.10% ± 0.03% of NK cells, 0.07% ± 0.03% of CD8+ T cells, and 0.09% ± 0.03% of CD4+ T cells).

In vitro experiments, performed with macaque PBMC in different conditions of stimulation, showed that the drugs used for treatment did not modify cell proliferation (data not shown).

Ex vivo intracellular IFN-γ immunostaining.

Briefly, PBMC were surface stained with combinations of fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies: anti-CD3 (Clinisciences)-anti-CD8 Becton Dickinson). Stained cells were then washed twice in PBS, fixed, and permeabilized with the IntraPrep kit (Immunotech). Intracellular IFN-γ was stained by direct immunofluorescence with a commercial anti-IFN-γ MAb (MD-1 clone; Cliniscience), kindly FITC labeled by C. Creminon (CEA, Saclay, France). Labeled cells were then analyzed in a Becton Dickinson FACScalibur cytometer, using Cell Quest software.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was carried out using nonparametric Wilcoxon rank and Mann-Whitney tests, which are adapted to small sample sizes, using StatView software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, N.C).

RESULTS

Appearance of proliferating NK cells and CD8, CD4, and B lymphocytes in the blood after SIV inoculation.

After evaluating the proportions of proliferating PBMC before infection, by means of ex vivo BrdU incorporation, we inoculated four macaques (group 1) intravenously with 50 AID50 of uncloned pathogenic SIVmac251. We then monitored the proportions of proliferating cells in blood lymphocyte populations over time and compared them with baseline values, using Wilcoxon's signed rank test (Fig. 1).

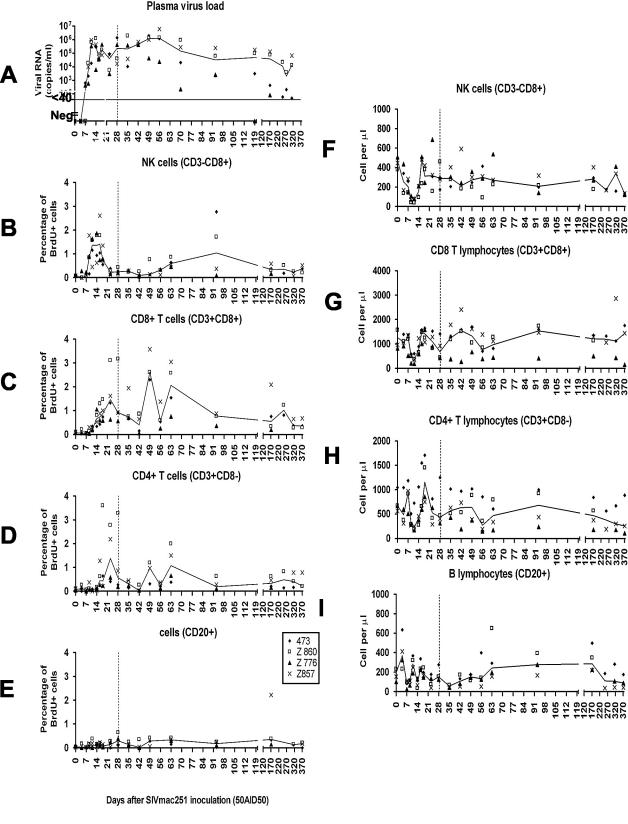

FIG. 1.

Longitudinal analysis of plasma SIV RNA load (A), proliferation of blood lymphocyte subpopulations (B to E), and lymphocyte blood counts (F to I) in four control macaques inoculated with 50 AID50 of pathogenic SIVmac251 (group 1). The results of ex vivo BrdU incorporation are given for each individual. Lines indicate the median values. Animals received a placebo from 4 h after virus inoculation to day 28 p.i., which is indicated by a vertical dashed line. In graph A, the limit of quantitative measurement of plasma virus load is indicated by a horizontal line at the level of 40 copies/ml. Negative values are plotted on the x axis.

The proportions of proliferating NK cells, T cells, and B cells all increased during primary infection, but with different kinetics (Fig. 1). Changes in the percentages of proliferating cells after virus exposure in the various lymphocyte populations and in plasma viral loads are shown in Fig. 1 for the group and separately, for one representative macaque, in Fig. 2.

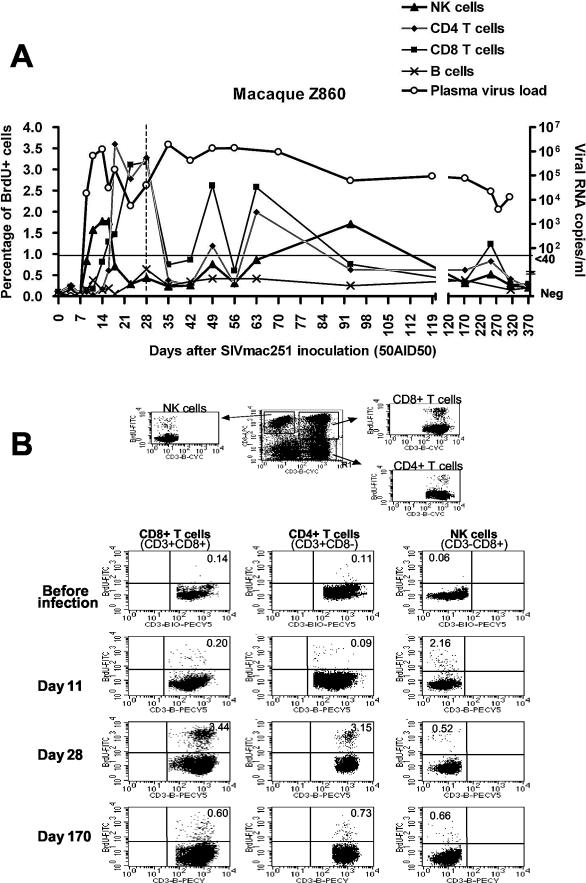

FIG.2.

(A) Evolution of proliferating (BrdU+) cell percentages in blood lymphocyte subpopulations and evolution of plasma viral load of one representative SIV-infected macaque of group 1 (Z860). The limit of quantitative measurement of plasma virus load is indicated by a horizontal line at the level of 40 copies/ml. Negative values are plotted on the x axis. (B) The electronic gates and representative dot plots used for the determination of proliferating NK cells and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are shown. Percentages of BrdU positive cells are indicated in each panel.

A transient increase in the proportion of proliferating NK cells was observed first, starting on day 9 (P < 0.0001). The percentage of NK cells proliferating remained high until day 18 postinfection (p.i.). On day 16 p.i., 1.41% ± 0.84% of blood NK cells incorporated BrdU ex vivo; this value is significantly different from baseline (P < 0.0001). The percentage of proliferating NK cells decreased rapidly thereafter, reaching a plateau on day 23 p.i. that persisted at a level significantly higher than baseline values until the end of the experiment (P = 0.0004 on day 371 p.i.).

The early increase in the proportion of proliferating NK cells in the blood overlapped with peak plasma viral load. Indeed, SIV RNA was detected in the plasma of two of four macaques on day 7 after virus inoculation (473 and 857), the other two macaques testing positive 2 days later (Z776 and Z860) (Fig. 1). Viremia peaks were reached on days 11 to 14 p.i. (613,198 ± 311,029 RNA copies/ml). First evidence of partial control of viremia was observed between days 16 and 23 (P = 0.0357 on day 16 p.i., P = 0.0251 on day 23 p.i., in comparison with days 11 and 14).

The percentage of proliferating CD8+ T cells increased in the blood as early as day 11 p.i. (P < 0.0001), at a time when plasma viremia peaked. Then, the percentage of proliferating CD8+ T cells reached a maximum between days 23 and 63. In all macaques, a first peak in the percentage of proliferating CD8+ T cells (1.47 ± 1.05; P < 0.0001 versus baseline) was observed on day 23, during the period of partial control of viremia. Therefore, the percentage of proliferating CD8+ T cells increased later than the percentage of proliferating NK cells and lasted longer but was similar in magnitude to the increase in proliferating NK cells. The highest increases were observed between day 21 and day 63, which coincided with the first evidence of partial control of plasma viremia.

The percentage of proliferating CD4+ T lymphocytes started to increase significantly on day 16 p.i. (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1 and 2), later than the increase in the proportion of proliferating CD8+ T cells (day 11 p.i.). Nevertheless, the magnitude of CD4+ T-cell proliferation in the blood was similar, with proliferating cells accounting for 1.38% ± 1.17% of total CD4+ T cells on day 23 p.i. As observed for CD8+ T cells, the percentage of proliferating CD4+ T lymphocytes remained high until day 63, returning thereafter to lower values and reaching a plateau significantly higher than baseline levels that was maintained until the end of the experiment (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). The percentage of proliferating CD4+ T cells was lower than that of proliferating CD8+ T cells (P < 0.0001, Wilcoxon signed rank test).

The percentage of proliferating B cells had increased significantly as early as the 9th day after SIV infection (P = 0.0196) (Fig. 1 and 2A), although this increase was smaller than that for NK and T cells. This percentage remained higher than before infection for the rest of the experiment.

The number of proliferating cells in the blood was then calculated from the percentages of proliferating cells in each population and cell counts in the blood for each population (data not shown). The kinetics of proliferation were similar whether determined as percentages or as absolute numbers, but the numbers of proliferating NK cells and proliferating CD8+ T cells in the blood increased 2 and 3 days later, respectively, than did the corresponding percentages. Nevertheless, the number of proliferating CD8+ T cells started to increase earlier than did the number of proliferating CD4+ T cells in the blood (day 14 p.i. for CD8+ T cells, P < 0.0001; day 16 p.i. for CD4+ T cells, P < 0.0001), with the number of proliferating NK cells increasing first (day 11 p.i., P = 0.0001).

This time lag between the increase in absolute counts and that in percentages of proliferating cells results from transient lymphocytopenia, which is observed for the NK and T-lymphocyte populations (Fig. 1), during the first 2 weeks of primary infection. NK cell lymphocytopenia started before T-cell lymphocytopenia, with a significant decrease in NK cell counts observed on day 4 (P < 0.0001), whereas CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell counts did not decrease until day 9 (P < 0.0001). Macaques completely recovered from T-cell and NK cell lymphocytopenia on day 16, but partial recovery was already detectable on day 14 for all lymphocyte populations. NK cell lymphocytopenia was more pronounced than T-cell lymphocytopenia in terms of both magnitude and duration. Although proliferating cells may not account for the observed massive recovery from transient lymphocytopenia, the number of proliferating cells in the blood did increase during recovery from lymphocytopenia (Fig. 1).

Thus, SIV infection induces a significant but transient burst of NK cell proliferation, which is temporally associated with the initial burst of SIV replication. In contrast, proliferating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were found circulating in the blood mostly after the initial peak of plasma viremia and were temporally associated with transient control of plasma viral load. Indeed, the increase in the proliferating NK cell population was not temporally associated with the increase in the proliferating T-cell population, indicating that the proliferation of these two cell types may not be driven by the same mechanism. Furthermore, although viremia remained high after primary infection, the proportions of proliferating cells in the blood decreased after the first 3 months, suggesting that more dividing cells circulate during primary infection than during chronic infection, despite persistent high levels of viral replication.

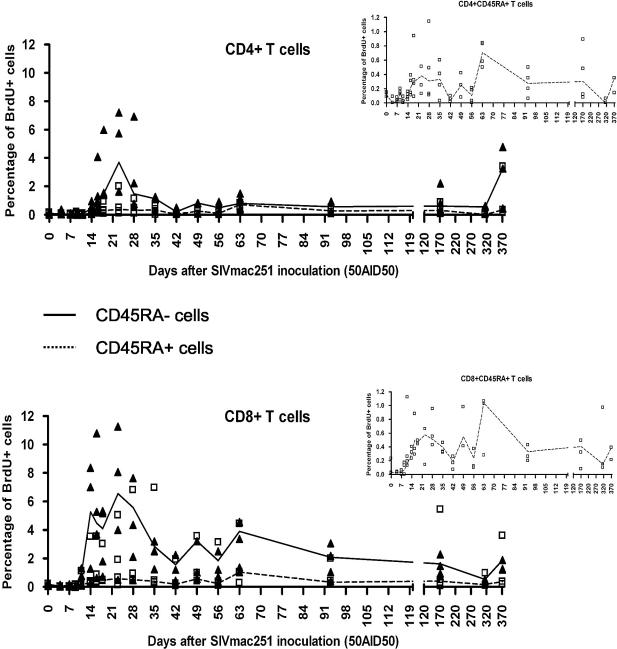

The increase in the frequencies of proliferating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells mostly concerns the CD45RA− cell population.

Combined four-color staining was used to characterize naive and memory proliferating T cells (Fig. 3). Both CD45RA+ and CD45RA− T cells incorporated BrdU during the period in which proliferation of the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations increased (Fig. 3). Indeed, on day 23, when the percentages of proliferating T cells peaked, 6.55% ± 3.27% of CD45RA− CD8+ T cells incorporated BrdU ex vivo (versus 0.19% ± 0.09% at baseline, P = 0.0004) whereas only 0.58% ± 0.78% of CD45RA+ CD8+ T cells incorporated BrdU (versus 0.03% ± 0.01% at baseline; P = 0.0004). Similar results were obtained for CD4+ T cells. On day 23, 0.38% ± 0.87% of CD45RA+ CD4+ T cells were proliferating (versus 0.12% ± 0.03% at baseline; P = 0.0086), whereas 3.69% ± 2.86% of CD45RA− CD4+ T cells were proliferating (versus 0.07% ± 0.10% at baseline; P = 0.0020). Furthermore, the proportion of CD45RA− CD8+ T cells displaying proliferation was higher than that for CD45RA− CD4+ T cells (P < 0.0001, Wilcoxon signed rank test), whereas the proportions of proliferating CD45RA+ CD8+ T cells and CD45RA+ CD4+ T cells were similar.

FIG. 3.

Longitudinal analysis of the proliferation of naive and memory CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes after SIV infection of group 1 macaques. CD45RA was used to designate CD3+ CD8+ and CD3+ CD8− as having a naive (CD45RA+) or memory (CD45RA−) phenotype. Curves represent median values. Open squares represent CD45RA− cells, and closed triangles represent CD45RA+ cells. For better visualization, the results obtained for CD45RA+ cells are also shown alone with a magnified scale (small graphs).

Naive CD45RA+ T cells accounted for the vast majority of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the blood of these macaques. Thus, differences between the numbers of proliferating naive and memory T cells in the blood were less clear-cut than were differences between percentages. Indeed, increases in the numbers of proliferating naive and memory CD8+ T cells were similar, and the population of proliferating CD45RA+ CD4+ T cells increased to a greater extent than that of CD45RA− CD4+ T cells, with the increase in proliferation occurring slightly earlier. This discrepancy in the behavior of CD4+ T cells may result from the active virus-induced destruction of activated CD4+ T cells.

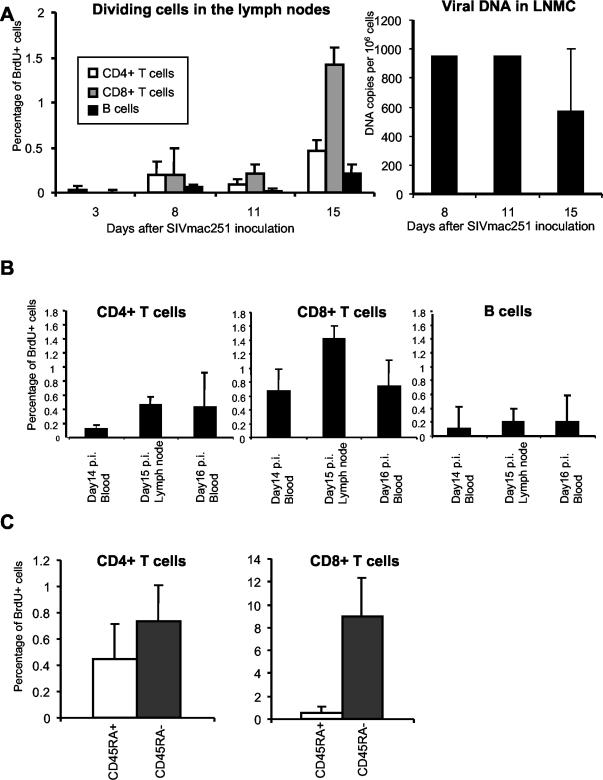

Increases in the percentages of proliferating T and B cells in the blood are associated with similar increases in the percentage of proliferating cells in lymph nodes.

Biopsies of accessible lymph nodes (inguinal and axillar) were carried out early in primary infection, on days 3, 8, 11, and 15 p.i. (Fig. 4A). On day 8 p.i., the percentages of proliferating T cells were already higher than on day 3, but they nonetheless remained low until day 11 (0.09% ± 0.02% for CD4+ T cells, 0.22% ± 0.05% for CD8+ T cells). The percentage of proliferating B cells showed no significant increase on days 8 and 11. The largest increase in the percentage of proliferating T cells was observed in lymph nodes on day 15 p.i. (Fig. 4A), at a time when two of four monkeys (473 and Z860) displayed evidence of partial control of viral load in the lymph nodes (Fig. 4A). This temporal association parallels that between proliferating T cells in the blood and the control of plasma viral load, strongly suggesting either that the observed T-cell proliferation is involved in the generation of specific and efficient effector T cells or that a sufficient threshold of viremia and time delay is needed to allow for detectable increase of T-cell division.

FIG. 4.

(A) Lymphocyte proliferation and cell-associated virus loads in the lymph nodes of group 1 control macaques inoculated with a pathogenic SIVmac251. LNMC, lymph node MNCs. (B) Comparison of the percentages of proliferating T and B cells in the blood (14 and 16 days p.i.) and in the lymph nodes (15 days p.i.). (C) Percentages of proliferating cells in CD45RA+ (naive) or CD45RA− (memory) T cells in the lymph nodes on day 15 after SIV infection. Median values ± standard deviations of the medians are represented.

The proportions of proliferating T cells in the lymph nodes increased to a similar extent as those in the blood at equivalent time points for CD4+ T cells and increased to a slightly greater extent for CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4B). As in the blood, the proportion of CD8+ T lymphocytes proliferating at day 15 (1.42 ± 0.13) was higher than the proportion of CD4+ T lymphocytes showing proliferation (0.46 ± 0.08). This may reflect either active destruction of proliferating CD4+ T cells in the lymph nodes or the recruitment of a larger number of CD8 T cells to this site of virus replication. This may be the reason why proliferating CD4+ T cells are detected in the blood later than proliferating CD8+ T cells. Indeed, on day 8 p.i., the proportions of proliferating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were similar in the lymph nodes. By days 11 and 15 p.i. this was no longer the case and the proportion of proliferating cells was higher for CD8+ T cells.

As in the blood, the increase in the proportion of proliferating CD8+ T cells in lymph nodes was higher for CD45RA− memory cells than for CD45RA+ cells (Fig. 4C). In CD4+ T cells, the percentage of proliferating cells did not differ significantly between the CD45RA− and CD45RA+ populations. This may reflect the induction by the virus of memory CD4+ T-cell destruction in the lymph nodes. Indeed, cell-associated viral load was already high on days 8 and 11 p.i. in the lymph nodes (Fig. 4A).

Effect of early HAART on cell proliferation during the primary immune response of macaques infected with the pathogenic SIVmac251.

We evaluated the impact of virus replication on cell division by carrying out the same analysis for two groups of four macaques subjected to postexposure HAART. Treatment was given for 28 days, starting 4 h after virus inoculation. Group 2 animals received AZT (4.5 mg/kg), 3TC (2.5 mg/kg), and indinavir (20 mg/kg) twice per day by the oral route. Group 3 macaques were given AZT (4.5 mg/kg) and 3TC (2.5 mg/kg) subcutaneously, twice per day, and a higher dose of indinavir (60 mg/kg) orally, twice per day.

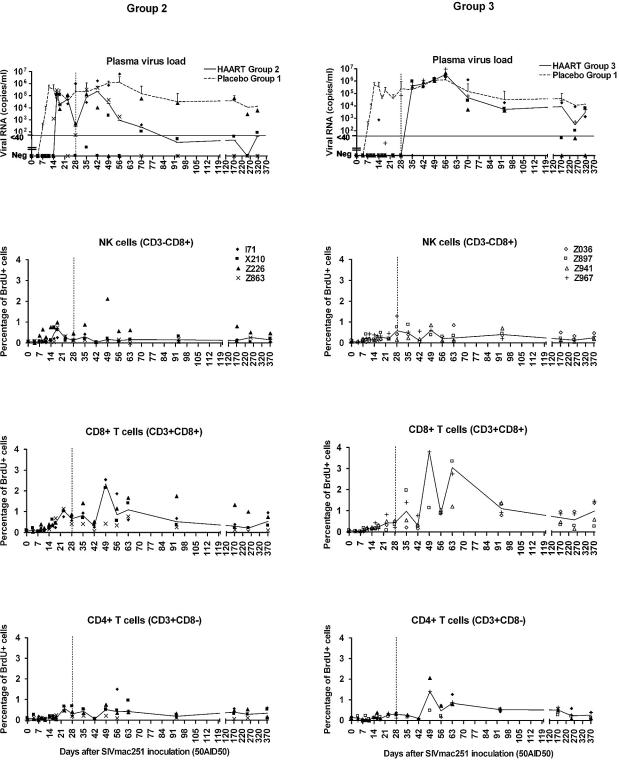

Treatment did not prevent infection, but the kinetics of plasma viremia were strongly affected in treated monkeys. During treatment, viremia increased later in the monkeys of group 2 (Fig. 5, left top panel) than in those of group 1 (placebo-treated monkeys) (Fig. 1 and 5), with peak levels lower for group 2. After the end of treatment, three of the four animals of group 2 displayed improvements in control of plasma viral loads. This observation suggests that immune response was improved during treatment in the context of a much lower virus burden.

FIG. 5.

Effect of HAART on plasma viral load (top panels) and on proliferation of NK cells and CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes (middle and bottom panels) in macaques treated with HAART after SIV exposure. Group 2 macaques (left panels) were treated twice per day orally with a combination of AZT (4.5 mg/kg), 3TC (2.5 mg/kg), and indinavir (20 mg/kg); group 3 macaques (right panels) were treated twice per day subcutaneously with a combination of AZT (4.5 mg/kg) and 3TC (2.5 mg/kg) and orally with indinavir (60 mg/kg). Treatment was started 4 h postexposure and was stopped on day 28 p.i., which is indicated on each panel by a vertical dashed line. Curves show medians of four macaques per group. In the top panels, the median of plasma viral loads of group 1 control monkeys which were treated with a placebo is superimposed (dashed line), and the limit of quantitative measurement of plasma virus load is indicated by a horizontal line at the level of 40 copies/ml. Negative values are plotted on the x axis.

In group 3 monkeys, virus was undetectable or detected infrequently and only at low levels in the blood until day 28. Plasma viral load then increased rapidly within 1 or 2 weeks after treatment interruption (Fig. 5, right top panel). Viral replication was strongly inhibited during treatment, but these animals showed no significant improvement in the control of viremia after treatment was stopped, with viral loads not significantly different from those of placebo-treated animals (group 1) after day 42 p.i. (Fig. 5).

These results strongly suggest that the more effective antiviral regimen, which kept viral load levels very low during treatment, led to a poorer outcome after treatment was stopped than did less effective treatment. Indeed, when comparing the areas under curve of plasma virus loads for macaques of groups 1 and 2 after the viral set point (days 93 to 312), the Mann-Whitney U test gave P = 0.0771. This tendency became significant when excluding from the analysis macaque Z226 in group 2, which showed no evidence of improved control of plasma virus load (P < 0.05). During the same period of time, plasma virus loads of group 3 macaques were not statistically different from those of group 1 (P = 0.2888).

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that two monkeys in group 3 which had undetectable plasma virus when treatment was stopped on day 28 were already above 105 RNA copies/ml 7 days later, whereas in control macaques more time was needed to reach similar levels of plasma virus load. This could result from the fact either that some virus had already expanded before day 28 in macaques of group 3, allowing for the constitution of a viral reservoir, or that the immune response in that case is less efficient than in naive monkeys.

The percentage of proliferating CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes increased to a similar extent in group 2 and group 1 monkeys (P = 0.2482). As in control monkeys, the percentage of proliferating CD8+ T cells increased in group 2 before the percentage of proliferating CD4+ T cells.

A transient increase in the proportion of proliferating NK cells was also observed in group 2, coinciding with the increase in plasma viral load, and therefore later than the equivalent increase in control macaques. The proliferation of NK cells was strongly associated with the level and kinetics of plasma viremia.

During HAART, the plasma viral load of group 3 was low or undetectable. An increase in the proportions of proliferating T cells was found, but this increase was smaller than that observed for groups 1 and 2 (P < 0.05 on day 23 p.i.). However, after treatment was stopped, the percentage of proliferating T cells increased in group 3 macaques to levels similar to those in groups 1 and 2. In group 3 macaques, viremia peaks were observed on day 35 and were followed by peaks in the percentage of proliferating T cells between days 49 and 63 p.i. Group 3 macaques showed only a small increase in the proportion of NK cells between days 28 and 49.

Thus, the transient increase in the proliferation of T cells in the blood during primary infection was strongly associated with virus replication and occurred after the peak in plasma viral load. This observation suggests either that T-cell proliferation was involved in the partial control of viremia or that a sufficient load of virus is needed to reach detectable T-cell proliferation.

Ag-specific helper T-cell response.

We assessed the proliferative responses of PBMC to recombinant p27 SIV Ag at various times, as a means of evaluating Ag-specific helper T-cell responses. Responses were considered positive if SI exceeded 3.02 and mean counts exceeded 538 cpm, on the basis of statistical analysis of baseline values as stated in Materials and Methods.

During the treatment period, Ag-specific helper T-cell responses were detected in one of four animals in group 1 (2 of 16 SI classed as positive, with values between 13 and 37), two of four in group 2 (4 of 16 SI classed as positive, with values between 4 and 60), and one of four in group 3 (1 of 16 SI positive, with a value of 4) (Table 1). Thus, during treatment, positive SI values were obtained more frequently in the monkeys of group 2.

TABLE 1.

In vitro proliferative responses to recombinant SIV p27Gag antigen in macaques inoculated with SIVmac251 and treated with HAART (groups 2 and 3) or with a placebo (group 1)a

| Monkey | SI (cpm) at day p.i.:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 14 | 23 | 28 | 35 | 42 | 49 | 56 | 63 | 93 | 312 | 392 | |

| Group 1 | ||||||||||||

| 473 | 37 (14,570) | 13 (5,230) | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Z776 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Z857 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Z860 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Group 2 | ||||||||||||

| I71 | 60 (4,936) | NS | 4 (1,541) | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| X210 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Z226 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 5 (1,252) | NS | 21 (1,016) | NS | NS | NS |

| Z863 | 16 (1,136) | NS | 12 (1,969) | NS | NS | 47 (3,504) | NS | NS | 15 (1,139) | NS | NS | NS |

| Group 3 | ||||||||||||

| Z036 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 9 (560) | NS | NS | NS |

| Z897 | NS | 4 (561) | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 20 (1,122) | NS | NS | NS |

| Z941 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Z967 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

Proliferative responses were considered positive when the average count of triplicate wells stimulated with recombinant p27 was above 538 cpm and the SI was above 3.02 (see Materials and Methods for statistical analysis). NS, no stimulation. Baseline values showed no stimulation, except for monkey I71, for which one baseline value was not determined.

After the end of treatment, two of the four monkeys had transiently positive SI in each of groups 2 and 3, with SI of 6 to 47. No positive SI were obtained for the placebo-treated group.

Furthermore, animals of group 2 with positive virus-specific helper T-cell responses after the end of treatment (Z226 and Z863) also displayed the most efficient control at viral set point (3 months p.i.).

Overall, the group 2 monkeys with the most efficient control of plasma viral load after treatment were also more likely to display proliferative responses.

Activation of CD8+ T cells during primary infection.

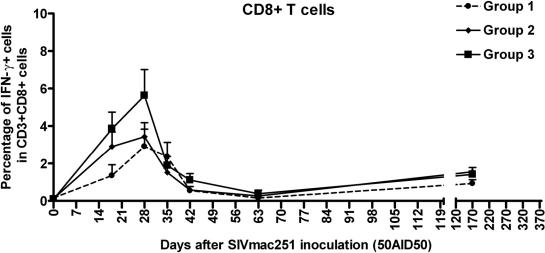

PBMC were stained ex vivo for intracellular IFN-γ, to evaluate cellular immune activation. At baseline, before infection, the percentages of cells in the blood staining positive for IFN-γ were very low (0.11% ± 0.05%) (Fig. 6). The proportion of CD8+ T lymphocytes positive for intracellular IFN-γ increased during primary infection between days 18 and 42 after SIV inoculation (P = 0.0117, Wilcoxon signed rank test). No significant difference was found among the three groups. The detection of IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells in the blood of macaques from group 3 during HAART (days 18 and 28), when these animals had very low viral loads and small proportions of proliferating CD8+ T cells, suggests that proliferation and activation are dissociated, at least for this group. This dissociation may result from Ag concentrations sufficiently high to activate CD8+ T cells but too low for expansion in the context of low CD4+ helper T-cell responses.

FIG. 6.

Intracellular IFN-γ expression in blood CD8+ T cells over time. PBMC were labeled ex vivo. CD8+ T cells were defined on the basis of membrane expression of both CD3 and CD8. Curves represent median values from four macaques per group. Group 1, placebo-treated macaques; groups 2 and 3, macaques treated postexposure with different combinations of AZT, 3TC, and indinavir.

In groups 1 and 2, CD8+ T-cell activation occurred at the same time as CD8+ T-cell proliferation. No IFN-γ-positive cells were detected among helper T cells (CD3+ CD8−) or NK cells (CD3− CD8+) at any time during the experiment.

We also investigated the Ag-specific activation of T cells in this animal model (M. fascicularis), for which major histocompatibility complex tetramer technology is not available, by carrying out IFN-γ ELISPOT assays at various times after virus inoculation. This assay was adapted from the work of Larsson et al. (21) to the detection of SIV-specific T-cell responses. Briefly, PBMC were incubated with recombinant vaccinia viruses producing the SIV Gag, Pol, and Env proteins, or with wild vaccinia virus as control, and spots were counted after 16 h of ex vivo stimulation. Control wells with no stimulation at all (PBMC in medium alone) were also performed when a sufficient amount of PBMC was available. IFN-γ was captured by using purified GZ4 MAb (Mabtech), and spots were revealed by using biotinylated 7B6-1 antibody (Mabtech). ELISPOTs were performed on PBMC frozen on days 0, 7, 30, and 70 p.i. The median number of spots per million PBMC in wild-type vaccinia virus-stimulated wells remained persistently similar to that in SIV recombinant vaccinia virus-stimulated wells. Nevertheless, on day 30, the number of spots per million PBMC had increased from 84 ± 53 (median ± standard error of the median of all preinfection assays) to 593 ± 116, 307 ± 30, and 300 ± 91 for groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. These values were not significantly different from that in wells incubated in medium alone (P = 0.7860). Thus, we were unable to detect the secretion of IFN-γ upon Ag-specific stimulation due to high background levels, but our interpretation is that PBMC were already activated in vivo due to SIV infection per se and did not require further stimulation in vitro to secrete IFN-γ as shown by the results of direct ex vivo labeling of intracellular IFN-γ (Fig. 6).

DISCUSSION

There is a growing body of evidence that the antiviral immune responses generated during lentivirus primary infection are crucial for the initial control of viral replication and the outcome of chronic infection (1-4, 20, 41). However, little is known about the dynamics of T-cell proliferation and the effect of early HAART during HIV or SIV primary infection. In this study, we used the nucleoside analog BrdU to study the kinetics of cell proliferation ex vivo over a period of 1 year from the time of SIV infection in macaques untreated or treated with HAART from 4 h to 28 days after intravenous virus inoculation. In rodents, BrdU has been widely used to evaluate T-cell turnover (29, 37, 38, 51). BrdU is incorporated into cellular DNA during the S phase of the cell cycle and therefore unambiguously labels proliferating cells. It can be detected by flow cytometry, facilitating simultaneous determination of the phenotypes of various lymphocyte subsets. Our method was based on the measurement of ex vivo BrdU incorporation into MNCs from blood and lymph node samples harvested at a number of time points shortly after SIV infection in macaques. This method has proved to be particularly suitable for longitudinal studies involving the sequential determination of instantaneous DNA replication activities. We obtained an unprecedented detailed analysis of blood cell proliferation kinetics, particularly during the first 4 weeks after SIV infection. In the absence of antiviral treatment (group 1), macaques inoculated with pathogenic SIV demonstrated a burst of NK (CD8+ CD3−) cell proliferation between days 9 and 16 p.i., following the first detection of virus in plasma (day 7). NK cell proliferation was followed by an increase in the proportion of proliferating CD8+ (day 14) and CD4+ (day 16) T cells. The kinetics and magnitude of the increase in proliferation differed between groups of macaques, and these differences appeared to result from differences in the kinetics and rates of SIV replication. Dramatic depletion of the blood cells of the innate (NK) and adaptive (CD4+ and CD8+ T cells) immune systems was observed early after infection with SIV in the untreated group, and the numbers of proliferating cells increased after this transient blood lymphocytopenia. We think that these decreases in cell counts may result from redistribution to other body compartments rather than the actual disappearance of cells (43). Indeed, lymphocytopenia is restricted to the blood compartment, which contains only a very small part of the total lymphoid pool (60). Similar redistributions of total and Ag-specific cycling T cells between blood and lymphoid organs have been observed in the acute immune response in mice (55).

In the absence of specific reagents for SIV-reactive T cells in cynomolgus macaques, we were unable to evaluate the specificity of proliferating cells. However, several observations indicate that there is a significant Ag-specific component at the height of proliferation. Indeed, the kinetics of CD8+ T-cell proliferation paralleled the appearance of IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells in the blood compartment. However, we cannot exclude the possibility of bystander activation (14, 50, 52). Previous studies of bystander activation have suggested that this process is common in CD8+ T cells and more limited in CD4+ T cells. With the advent of novel techniques for counting Ag-specific cells, bystander activation in CD8+ T cells has now been shown to be minimal in in vivo systems (5, 33, 64).

The rapidity of the host response and the order in which cells proliferate—first NK cells, then CD8+ and CD4+ T cells—suggest that both innate and Ag-specific immune responses are triggered. During a typical in vivo viral infection, NK cells are activated by various cytokines, including IFN-α/β, interleukin-12, and interleukin-18, and these cells influence the selection and activation of an appropriate type of adaptive immunity (19, 39). When virus-specific cytotoxic T-cell responses start to develop, NK cell activity declines and returns to preinfection levels (11). Infection with SIV resulted in an increase in NK cytotoxicity, which peaked 2 weeks p.i., coinciding with peak of viremia (11). Thus, our results show that the proliferation of NK cells paralleled the NK cytotoxicity described during primary SIV infection and that cell division may participate in their expansion. The involvement of NK cells in the control of primary SIV infection is not known, but macaques depleted of CD8+ lymphocytes, which may include CD8+ T cells and NK cells, at the time of SIV exposure display uncontrolled SIV replication and rapid disease progression (45). As the antibody used in this previous study recognized the CD8 α chain, which is present in both CD8+ T and NK cells, the participation of NK cells cannot be excluded. Overall, these data suggest that NK cells may contribute to the initial containment of primary SIV infection, although temporal association is not sufficient to determine cause or effect.

Proliferation was detected earlier in CD8+ T cells than in CD4+ T cells, but the maximum percentage of cells synthesizing DNA was similar in the two populations (day 23 p.i.). Differences in the proliferative responses of CD4+ and CD8+ cells were observed in vitro and in vivo (10, 13, 15, 17, 32, 56, 62).

The lower rate of proliferation of CD4+ T cells may account for CD4+ T-cell proliferation peaking 1 to 2 days after the proliferation of CD8+ T cells, during primary SIV infection in our study and during other primary viral infections (13, 61).

On that point, it is difficult to compare our data with those from other studies, because cellular immune responses in mice have been investigated mostly by measuring Ag-specific cells in lymphoid organs, the spleen in particular. The spleen has been shown to be the site of secondary accumulation of postcycling Ag-specific cells, just before the contraction phase of the immune response (6, 40). This may account for the percentages of Ag-specific cells being generally higher than the percentages of cycling cells in blood reported here. Indeed, blood is only a transit compartment, and circulating cells are very rapidly renewed (60). When BrdU is used in conjunction with peptide-major histocompatibility complex tetramers (9, 34), it is infused in vivo for long periods of time, providing data on proliferative history rather than on the proliferation of lymphocytes at a given time point, which was the aim of our study. In primates, no direct detailed kinetic study of lymphocyte DNA synthesis in primary infection has been carried out.

Our results for primary SIV infection in macaques differ from those reported by Kaur et al. (18), who observed higher percentages of Ki67+ cells (up to 40 and 50% in CD8+ T lymphocytes and NK cells, respectively) and a large difference between the percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Ki67 expression was not significantly higher in CD4+ T cells in this study. However, as pointed out by Kaur et al. (18), Ki67+ cells include cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle that might not go on to S phase and division (7). Thus, assessments of Ki67 Ag expression may overestimate the size of the proliferating cell population. However, ex vivo BrdU incorporation gives lower values than the administration of BrdU in vivo (26), although this difference is minimized by controlling the duration of BrdU exposure (C. Penit and F. Vasseur, unpublished results). In vivo BrdU labeling cannot be used for multiple determinations separated by short time intervals like those used here. We were able to obtain a detailed picture of PBMC proliferation kinetics during SIV primary infection, to detect differences between lymphoid subsets, and to compare these data with viral dynamics data. We thus provide direct evidence for an early increase in NK cell proliferation associated with viral load. The proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, mostly concerning CD8+ CD45RA− cells, occurred later than the proliferation of NK cells and coincided with an increase in levels of circulating IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells and the initial decline of viremia.

We extended our analysis to consider the impact of viral load on the dynamics of cell proliferation during the early phase of infection by studying two groups of macaques given two different HAART regimens. In macaques which received exclusively intragastric treatment (group 2), SIV replication was delayed but not abolished during treatment, with a peak on day 16 after infection. In these monkeys, NK cell proliferation was only slightly delayed (increased significantly from baseline on day 14, P = 0.0299, instead of day 9 in group 1) and lower, considering the height of the peak, but T-cell proliferation was not statistically different. This group of monkeys displayed better control of virus replication after the end of treatment than untreated macaques. The treatment was more effective in group 3. The virus was undetectable or viral load was very low during the treatment period, and T-cell and NK cell proliferation was almost abolished. However, after treatment had ended, the monkeys of group 3 showed an increase in SIV replication, which peaked on day 56 p.i., and showed no significant improvement in the control of viral load, with cell proliferation detectable. The proliferation burst corresponded to a sharp increase in plasma viral load, which remained very high and stable thereafter, suggesting defective control of virus replication. These observations have important implications for our understanding of the early pathogenesis of HIV infection and for the design of therapeutic protocols aiming to limit immune system damage during primary HIV infection.

Our findings confirm that macaques are not protected against SIV infection by postexposure prophylaxis during primary infection using a combination of AZT, 3TC, and indinavir but that partial control of viremia can be achieved in the long term depending on the efficiency during treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Agence Nationale de la Recherche sur le SIDA (ANRS, Paris, France) and by the Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique (CEA, Fontenay-aux-Roses, France). K.B.-C. received a CIFRE grant allocated by Agence Nationale de la Recherche Technique (ANRT, Paris, France) and by Glaxo-Smithkline Laboratories (Marly-le Roi, France).

We thank G. Walckenaer and D. Lapierre from GSK and M.-C. Gervais and P. Duprat from Merck Sharp & Dohme-Chibret for effective scientific collaboration and for providing the drugs used in the study. We also thank B. Delache and C. Feuillat-Aubenque for expert technical assistance and D. Renault, P. Pochard, and J. C. Wilk for animal care.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, T. M., D. H. O'Connor, P. Jing, J. L. Dzuris, B. R. Mothe, T. U. Vogel, E. Dunphy, M. E. Liebl, C. Emerson, N. Wilson, K. J. Kunstman, X. Wang, D. B. Allison, A. L. Hughes, R. C. Desrosiers, J. D. Altman, S. M. Wolinsky, A. Sette, and D. I. Watkins. 2000. Tat-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes select for SIV escape variants during resolution of primary viraemia. Nature 407:386-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barouch, D. H., S. Santra, J. E. Schmitz, M. J. Kuroda, T. M. Fu, W. Wagner, M. Bilska, A. Craiu, X. X. Zheng, G. R. Krivulka, K. Beaudry, M. A. Lifton, C. E. Nickerson, W. L. Trigona, K. Punt, D. C. Freed, L. Guan, S. Dubey, D. Casimiro, A. Simon, M. E. Davies, M. Chastain, T. B. Strom, R. S. Gelman, D. C. Montefiori, M. G. Lewis, E. A. Emini, J. W. Shiver, and N. L. Letvin. 2000. Control of viremia and prevention of clinical AIDS in rhesus monkeys by cytokine-augmented DNA vaccination. Science 290:486-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borrow, P., H. Lewicki, B. H. Hahn, G. M. Shaw, and M. B. Oldstone. 1994. Virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity associated with control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 68:6103-6110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borrow, P., H. Lewicki, X. Wei, M. S. Horwitz, N. Peffer, H. Meyers, J. A. Nelson, J. E. Gairin, B. H. Hahn, M. B. Oldstone, and G. M. Shaw. 1997. Antiviral pressure exerted by HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) during primary infection demonstrated by rapid selection of CTL escape virus. Nat. Med. 3:205-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butz, E. A., and M. J. Bevan. 1998. Massive expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during an acute virus infection. Immunity 8:167-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coles, R. M., S. N. Mueller, W. R. Heath, F. R. Carbone, and A. G. Brooks. 2002. Progression of armed CTL from draining lymph node to spleen shortly after localized infection with herpes simplex virus 1. J. Immunol. 168:834-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Combadiere, B., C. Blanc, T. Li, G. Carcelain, C. Delaguerre, V. Calvez, R. Tubiana, P. Debre, C. Katlama, and B. Autran. 2000. CD4+ Ki67+ lymphocytes in HIV-infected patients are effector T cells accumulated in the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:3598-3603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doherty, P. C., and J. P. Christensen. 2000. Accessing complexity: the dynamics of virus-specific T cell responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:561-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flynn, K. J., J. M. Riberdy, J. P. Christensen, J. D. Altman, and P. C. Doherty. 1999. In vivo proliferation of naive and memory influenza-specific CD8+ T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:8597-8602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foulds, K. E., L. A. Zenewicz, D. J. Shedlock, J. Jiang, A. E. Troy, and H. Shen. 2002. Cutting edge: CD4 and CD8 T cells are intrinsically different in their proliferative responses. J. Immunol. 168:1528-1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giavedoni, L. D., M. C. Velasquillo, L. M. Parodi, G. B. Hubbard, and V. L. Hodara. 2000. Cytokine expression, natural killer cell activation, and phenotypic changes in lymphoid cells from rhesus macaques during acute infection with pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 74:1648-1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haigwood, N. L., A. Watson, W. F. Sutton, J. McClure, A. Lewis, J. Ranchalis, B. Travis, G. Voss, N. L. Letvin, S. L. Hu, V. M. Hirsch, and P. R. Johnson. 1996. Passive immune globulin therapy in the SIV/macaque model: early intervention can alter disease profile. Immunol. Lett. 51:107-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Homann, D., L. Teyton, and M. B. Oldstone. 2001. Differential regulation of antiviral T-cell immunity results in stable CD8+ but declining CD4+ T-cell memory. Nat. Med. 7:913-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huleatt, J. W., and L. Lefrancois. 1995. Antigen-driven induction of CD11c on intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes and CD8+ T cells in vivo. J. Immunol. 154:5684-5693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jelley-Gibbs, D. M., N. M. Lepak, M. Yen, and S. L. Swain. 2000. Two distinct stages in the transition from naive CD4 T cells to effectors, early antigen-dependent and late cytokine-driven expansion and differentiation. J. Immunol. 165:5017-5026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin, X., D. E. Bauer, S. E. Tuttleton, S. Lewin, A. Gettie, J. Blanchard, C. E. Irwin, J. T. Safrit, J. Mittler, L. Weinberger, L. G. Kostrikis, L. Zhang, A. S. Perelson, and D. D. Ho. 1999. Dramatic rise in plasma viremia after CD8+ T cell depletion in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J. Exp. Med. 189:991-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaech, S. M., and R. Ahmed. 2001. Memory CD8+ T cell differentiation: initial antigen encounter triggers a developmental program in naive cells. Nat. Immunol. 2:415-422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaur, A., C. L. Hale, S. Ramanujan, R. K. Jain, and R. P. Johnson. 2000. Differential dynamics of CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocyte proliferation and activation in acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Virol. 74:8413-8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kos, F. J. 1998. Regulation of adaptive immunity by natural killer cells. Immunol. Res. 17:303-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koup, R. A., J. T. Safrit, Y. Cao, C. A. Andrews, G. McLeod, W. Borkowsky, C. Farthing, and D. D. Ho. 1994. Temporal association of cellular immune responses with the initial control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 syndrome. J. Virol. 68:4650-4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsson, M., X. Jin, B. Ramratnam, G. S. Ogg, J. Engelmayer, M. A. Demoitie, A. J. McMichael, W. I. Cox, R. M. Steinman, D. Nixon, and N. Bhardwaj. 1999. A recombinant vaccinia virus based ELISPOT assay detects high frequencies of Pol-specific CD8 T cells in HIV-1-positive individuals. AIDS 13:767-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lau, L. L., B. D. Jamieson, T. Somasundaram, and R. Ahmed. 1994. Cytotoxic T-cell memory without antigen. Nature 369:648-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, T. H., H. W. Sheppard, M. Reis, D. Dondero, D. Osmond, and M. P. Busch. 1994. Circulating HIV-1-infected cell burden from seroconversion to AIDS: importance of postseroconversion viral load on disease course. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 7:381-388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le Grand, R., P. Clayette, O. Noack, B. Vaslin, F. Theodoro, G. Michel, P. Roques, and D. Dormont. 1994. An animal model for antilentiviral therapy: effect of zidovudine on viral load during acute infection after exposure of macaques to simian immunodeficiency virus. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 10:1279-1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le Grand, R., B. Vaslin, J. Larghero, O. Neidez, H. Thiebot, P. Sellier, P. Clayette, N. Dereuddre-Bosquet, and D. Dormont. 2000. Post-exposure prophylaxis with highly active antiretroviral therapy could not protect macaques from infection with SIV/HIV chimera. AIDS 14:1864-1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lempicki, R. A., J. A. Kovacs, M. W. Baseler, J. W. Adelsberger, R. L. Dewar, V. Natarajan, M. C. Bosche, J. A. Metcalf, R. A. Stevens, L. A. Lambert, W. G. Alvord, M. A. Polis, R. T. Davey, D. S. Dimitrov, and H. C. Lane. 2000. Impact of HIV-1 infection and highly active antiretroviral therapy on the kinetics of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell turnover in HIV-infected patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:13778-13783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lifson, J. D., M. A. Nowak, S. Goldstein, J. L. Rossio, A. Kinter, G. Vasquez, T. A. Wiltrout, C. Brown, D. Schneider, L. Wahl, A. L. Lloyd, J. Williams, W. R. Elkins, A. S. Fauci, and V. M. Hirsch. 1997. The extent of early viral replication is a critical determinant of the natural history of simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Virol. 71:9508-9514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lifson, J. D., J. L. Rossio, R. Arnaout, L. Li, T. L. Parks, D. K. Schneider, R. F. Kiser, V. J. Coalter, G. Walsh, R. J. Imming, B. Fisher, B. M. Flynn, N. Bischofberger, M. Piatak, Jr., V. M. Hirsch, M. A. Nowak, and D. Wodarz. 2000. Containment of simian immunodeficiency virus infection: cellular immune responses and protection from rechallenge following transient postinoculation antiretroviral treatment. J. Virol. 74:2584-2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lucas, B., F. Vasseur, and C. Penit. 1993. Normal sequence of phenotypic transitions in one cohort of 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine-pulse-labeled thymocytes. Correlation with T cell receptor expression. J. Immunol. 151:4574-4582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lyles, R. H., A. Munoz, T. E. Yamashita, H. Bazmi, R. Detels, C. R. Rinaldo, J. B. Margolick, J. P. Phair, and J. W. Mellors. 2000. Natural history of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viremia after seroconversion and proximal to AIDS in a large cohort of homosexual men. Multicenter AIDS cohort study. J. Infect. Dis. 181:872-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mellors, J. W., C. R. Rinaldo, Jr., P. Gupta, R. M. White, J. A. Todd, and L. A. Kingsley. 1996. Prognosis in HIV-1 infection predicted by the quantity of virus in plasma. Science 272:1167-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murali-Krishna, K., and R. Ahmed. 2000. Cutting edge: naive T cells masquerading as memory cells. J. Immunol. 165:1733-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murali-Krishna, K., J. D. Altman, M. Suresh, D. Sourdive, A. Zajac, and R. Ahmed. 1998. In vivo dynamics of anti-viral CD8 T cell responses to different epitopes. An evaluation of bystander activation in primary and secondary responses to viral infection. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 452:123-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murali-Krishna, K., J. D. Altman, M. Suresh, D. J. Sourdive, A. J. Zajac, J. D. Miller, J. Slansky, and R. Ahmed. 1998. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: a reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity 8:177-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Musey, L., J. Hughes, T. Schacker, T. Shea, L. Corey, and M. J. McElrath. 1997. Cytotoxic-T-cell responses, viral load, and disease progression in early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:1267-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neildez, O., R. Le Grand, A. Cheret, P. Caufour, B. Vaslin, F. Matheux, F. Theodoro, P. Roques, and D. Dormont. 1998. Variation in virological parameters and antibody responses in macaques after atraumatic vaginal exposure to a pathogenic primary isolate of SIVmac251. Res. Virol. 149:53-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Penit, C. 1986. In vivo thymocyte maturation. BUdR labeling of cycling thymocytes and phenotypic analysis of their progeny support the single lineage model. J. Immunol. 137:2115-2121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rocha, B., C. Penit, C. Baron, F. Vasseur, N. Dautigny, and A. A. Freitas. 1990. Accumulation of bromodeoxyuridine-labeled cells in central and peripheral lymphoid organs: minimal estimates of production and turnover rates of mature lymphocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 20:1697-1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romagnani, S. 1992. Induction of TH1 and TH2 responses: a key role for the ‘natural’ immune response? Immunol. Today 13:379-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roman, E., E. Miller, A. Harmsen, J. Wiley, U. H. Von Andrian, G. Huston, and S. L. Swain. 2002. CD4 effector T cell subsets in the response to influenza: heterogeneity, migration, and function. J. Exp. Med. 196:957-968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenberg, E. S., M. Altfeld, S. H. Poon, M. N. Phillips, B. M. Wilkes, R. L. Eldridge, G. K. Robbins, R. T. D'Aquila, P. J. Goulder, and B. D. Walker. 2000. Immune control of HIV-1 after early treatment of acute infection. Nature 407:523-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenberg, E. S., L. LaRosa, T. Flynn, G. Robbins, and B. D. Walker. 1999. Characterization of HIV-1-specific T-helper cells in acute and chronic infection. Immunol. Lett. 66:89-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenberg, Y. J., and G. Janossy. 1999. The importance of lymphocyte trafficking in regulating blood lymphocyte levels during HIV and SIV infections. Semin. Immunol. 11:139-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenwirth, B., P. ten Haaft, W. M. Bogers, I. G. Nieuwenhuis, H. Niphuis, E. M. Kuhn, N. Bischofberger, J. L. Heeney, and K. Uberla. 2000. Antiretroviral therapy during primary immunodeficiency virus infection can induce persistent suppression of virus load and protection from heterologous challenge in rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 74:1704-1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmitz, J. E., M. J. Kuroda, S. Santra, V. G. Sasseville, M. A. Simon, M. A. Lifton, P. Racz, K. Tenner-Racz, M. Dalesandro, B. J. Scallon, J. Ghrayeb, M. A. Forman, D. C. Montefiori, E. P. Rieber, N. L. Letvin, and K. A. Reimann. 1999. Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CD8+ lymphocytes. Science 283:857-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sutjipto, S., N. C. Pedersen, C. J. Miller, M. B. Gardner, C. V. Hanson, A. Gettie, M. Jennings, J. Higgins, and P. A. Marx. 1990. Inactivated simian immunodeficiency virus vaccine failed to protect rhesus macaques from intravenous or genital mucosal infection but delayed disease in intravenously exposed animals. J. Virol. 64:2290-2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ten Haaft, P., B. Verstrepen, K. Uberla, B. Rosenwirth, and J. Heeney. 1998. A pathogenic threshold of virus load defined in simian immunodeficiency virus- or simian-human immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J. Virol. 72:10281-10285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thiebot, H., F. Louache, B. Vaslin, T. de Revel, O. Neildez, J. Larghero, W. Vainchenker, D. Dormont, and R. Le Grand. 2001. Early and persistent bone marrow hematopoiesis defect in simian/human immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques despite efficient reduction of viremia by highly active antiretroviral therapy during primary infection. J. Virol. 75:11594-11602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tissot, O., J. P. Viard, C. Rabian, N. Ngo, M. Burgard, C. Rouzioux, and C. Penit. 1998. No evidence for proliferation in the blood CD4+ T-cell pool during HIV-1 infection and triple combination therapy. AIDS 12:879-884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tough, D. F., P. Borrow, and J. Sprent. 1996. Induction of bystander T cell proliferation by viruses and type I interferon in vivo. Science 272:1947-1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tough, D. F., and J. Sprent. 1994. Turnover of naive- and memory-phenotype T cells. J. Exp. Med. 179:1127-1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tripp, R. A., S. Hou, A. McMickle, J. Houston, and P. C. Doherty. 1995. Recruitment and proliferation of CD8+ T cells in respiratory virus infections. J. Immunol. 154:6013-6021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Rompay, K. K., J. M. Cherrington, M. L. Marthas, P. D. Lamy, P. J. Dailey, D. R. Canfield, R. P. Tarara, N. Bischofberger, and N. C. Pedersen. 1999. 9-[2-(Phosphonomethoxy)propyl]adenine (PMPA) therapy prolongs survival of infant macaques inoculated with simian immunodeficiency virus with reduced susceptibility to PMPA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:802-812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Rompay, K. K., P. J. Dailey, R. P. Tarara, D. R. Canfield, N. L. Aguirre, J. M. Cherrington, P. D. Lamy, N. Bischofberger, N. C. Pedersen, and M. L. Marthas. 1999. Early short-term 9-[2-(R)-(phosphonomethoxy)propyl]adenine treatment favorably alters the subsequent disease course in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected newborn rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 73:2947-2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vasseur, F., A. Le Campion, J. H. Pavlovitch, and C. Penit. 1999. Distribution of cycling T lymphocytes in blood and lymphoid organs during immune responses. J. Immunol. 162:5164-5172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Veiga-Fernandes, H., U. Walter, C. Bourgeois, A. McLean, and B. Rocha. 2000. Response of naive and memory CD8+ T cells to antigen stimulation in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 1:47-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verrier, B., R. Le Grand, Y. Ataman-Onal, C. Terrat, C. Guillon, P. Y. Durand, B. Hurtrel, A. M. Aubertin, G. Sutter, V. Erfle, and M. Girard. 2002. Evaluation in rhesus macaques of Tat and rev-targeted immunization as a preventive vaccine against mucosal challenge with SHIV-BX08. DNA Cell Biol. 21:653-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Villada, I. B., L. Mortara, A. M. Aubertin, H. Gras-Masse, J. P. Levy, and J. G. Guillet. 1997. Positive role of macaque cytotoxic T lymphocytes during SIV infection: decrease of cellular viremia and increase of asymptomatic clinical period. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 19:81-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watson, A., J. Ranchalis, B. Travis, J. McClure, W. Sutton, P. R. Johnson, S. L. Hu, and N. L. Haigwood. 1997. Plasma viremia in macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus: plasma viral load early in infection predicts survival. J. Virol. 71:284-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Westermann, J., and R. Pabst. 1990. Lymphocyte subsets in the blood: a diagnostic window on the lymphoid system? Immunol. Today 11:406-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Whitmire, J. K., R. A. Flavell, I. S. Grewal, C. P. Larsen, T. C. Pearson, and R. Ahmed. 1999. CD40-CD40 ligand costimulation is required for generating antiviral CD4 T cell responses but is dispensable for CD8 T cell responses. J. Immunol. 163:3194-3201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wong, P., and E. G. Pamer. 2001. Cutting edge: antigen-independent CD8 T cell proliferation. J. Immunol. 166:5864-5868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yasutomi, Y., K. A. Reimann, C. I. Lord, M. D. Miller, and N. L. Letvin. 1993. Simian immunodeficiency virus-specific CD8+ lymphocyte response in acutely infected rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 67:1707-1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zarozinski, C. C., and R. M. Welsh. 1997. Minimal bystander activation of CD8 T cells during the virus-induced polyclonal T cell response. J. Exp. Med. 185:1629-1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zimmerman, C., K. Brduscha-Riem, C. Blaser, R. M. Zinkernagel, and H. Pircher. 1996. Visualization, characterization, and turnover of CD8+ memory T cells in virus-infected hosts. J. Exp. Med. 183:1367-1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]