Abstract

We previously described the phenotype associated with three alanine substitution mutations in conserved residues (Trp23, Phe40, and Asp51) in the N-terminal domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid protein (CA). All of the mutants produce noninfectious virions that lack conical cores and, despite having a functional reverse transcriptase (RT), are unable to initiate reverse transcription in vivo. Here, we have focused on elucidating the mechanism by which these CA mutations disrupt virus infectivity. We also report that cyclophilin A packaging is severely reduced in W23A and F40A virions, even though these residues are distant from the cyclophilin A binding loop. To correlate loss of infectivity with a possible defect in an early event preceding reverse transcription, we modeled disassembly by generating viral cores from particles treated with mild nonionic detergent; cores were isolated by sedimentation in sucrose density gradients. In general, fractions containing mutant cores exhibited a normal protein profile. However, there were two striking differences from the wild-type pattern: mutant core fractions displayed a marked deficiency in RT protein and enzymatic activity (<5% of total RT in gradient fractions) and a substantial increase in the retention of CA. The high level of core-associated CA suggests that mutant cores may be unable to undergo proper disassembly. Thus, taken together with the almost complete absence of RT in mutant cores, these findings can account for the failure of the three CA mutants to synthesize viral DNA following virus entry into cells.

The capsid protein (CA) of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) plays an important role in virus assembly and early postentry events in the virus life cycle and is derived from the Gag polyprotein (Pr55gag) (reviewed in references 12, 22, 63, and 72). Proteolytic processing of Gag by the viral protease (PR) (36, 51) is accompanied by viral “maturation,” i.e., structural rearrangements of the viral proteins within the particle, which result in conversion of immature particles to mature, infectious virions containing an electron-dense, cone-shaped core (34, 35, 64, 68) (reviewed in references 57, 63, and 72). Mature cores are inherently unstable, but recently, several groups have developed methods to isolate purified cores by using mild detergent treatment (1, 19, 43, 45, 67). The interior portion of the viral core is a ribonucleoprotein complex consisting of the host  primer, genomic RNA, and viral proteins, including reverse transcriptase (RT), integrase (IN), and nucleocapsid protein (63), as well as PR (67) and the accessory proteins Nef and Vpr (1, 18, 19, 45, 67).

primer, genomic RNA, and viral proteins, including reverse transcriptase (RT), integrase (IN), and nucleocapsid protein (63), as well as PR (67) and the accessory proteins Nef and Vpr (1, 18, 19, 45, 67).

The cores are thought to be organized as fullerene cones with curved hexagonal arrays of CA rings, whose ends are closed by 12 pentameric “defects” (29, 48). Hexameric arrangements of HIV-1 CA have also been proposed in another study (50). Proper assembly of cores (14, 17, 55, 58, 60, 64, 65) and optimal core stability (19) are apparently required for infectivity. CA forms a shell surrounding mature cores, but following virus entry into cells, it is released, allowing the ribonucleoprotein complex to initiate reverse transcription (33; reviewed in references 30, 63, and 72). This process is known as uncoating or disassembly and is an essential step in virus replication.

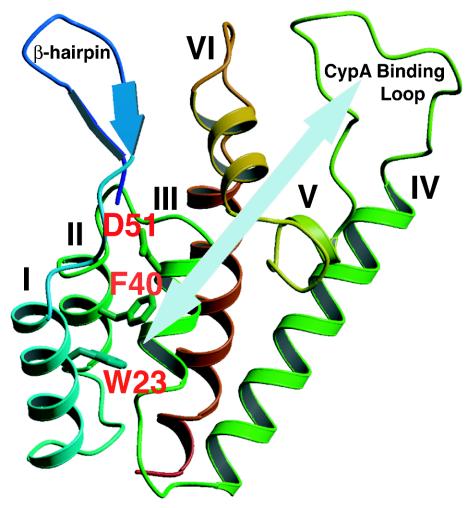

X-ray crystallographic and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies have shown that the HIV-1 CA protein, which has 231 amino acids, is composed of two independently folded domains connected by a short linker: an N-terminal “core” domain (residues 1 to 145) (31, 53) and a C-terminal “dimerization” domain (residues 151 to 231) (28) (For reviews, see references 22 and 62.) Comparison of the NMR structures of the N-terminal domains of mature CA and the immature form (covalently linked to matrix [MA]) (59) indicates that formation of the β-hairpin at the N terminus of mature CA, which occurs following proteolytic cleavage of Gag (31, 64), induces both an ∼2-Å displacement of helix VI and displacement of the cyclophilin A (CypA) binding loop (Fig. 1). Through the use of high-resolution mass spectrometry to monitor hydrogen/deuterium exchange, studies with in vitro assembled HIV-1 CA tubes provide strong biochemical evidence for structured interactions of the linker segment after assembly and for the predicted (48) role of C-terminal dimerization in promoting N-terminal hexamer interactions (47). In addition, cross-linking studies have revealed a previously unidentified interaction between Lys70 (N-terminal domain) and Lys182 (C-terminal domain) (47). Interestingly, analysis of C-terminal Rous sarcoma virus CA mutants with second-site suppressor mutations in the N-terminal domain also suggests that interdomain interactions are involved in functional activity of CA (7).

FIG. 1.

Ribbon diagram showing the front view of the N-terminal domain of HIV-1 CA. The β-hairpin structure, CypA binding loop, and seven α-helices are labeled, and the helices are numbered as designated by Gitti et al. (31). The three residues mutated in this study, W23, F40, and D51, are highlighted in red. The light blue arrow indicates that residues W23 (helix I) and F40 (helix II) are distant from the CypA binding loop. The diagram was generated by Molscript (46).

The N-terminal domain of CA is important for early postentry events in the virus life cycle, and mutations within this domain are associated with loss of infectivity, aberrant core formation, and defects in reverse transcription (5, 10, 14, 17, 19, 55, 56, 60, 64-66). A similar phenotype is induced by a new antiviral compound, termed “CAP-1,” which binds to N-terminal residues of CA (58). Recent analysis of a series of HIV-1 alanine-scanning CA mutants also indicates that a distinct surface comprised of helices I to III (Fig. 1) is required for formation of the mature core (65). Residues 85 to 93 in the exposed proline-rich loop (27, 73) constitute the binding site for CypA (49), a host peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase that is incorporated into virions (21, 54, 61). CypA packaging enhances virus infectivity and is significantly reduced by point mutations in the CypA binding loop or by more extensive mutations in other N-terminal residues (8, 11, 17, 21, 61, 69). Interestingly, although cyclosporin A, an immunosuppressive drug, inhibits CypA packaging and replication (20, 21, 61), infectivity can be restored by infecting target cells with virus particles pseudotyped with the vesicular stomatitis virus envelope protein (4) or preincubated in natural endogenous reverse transcription reactions (40). CypA has the properties of a molecular chaperone (3, 13), and recent evidence suggests that it catalyzes correct folding of CA and prevents random aggregation of CA (6, 32, 37, 69).

As part of an effort to elucidate the function of HIV-1 CA in virus replication, we have been investigating the effect of alanine substitution mutations in conserved residues in the N-terminal domain of CA. We previously described the unusual phenotype associated with three such mutations (60): in Trp23 and Phe40, which are among a group of highly conserved hydrophobic residues (53), and in Asp51, which forms a salt bridge with Pro1 (31, 64) (Fig. 1). All of the mutants produce noninfectious particles that lack cone-shaped cores and are unable to initiate reverse transcription in infected cells, although virions contain a functional RT.

In the present work, we have further investigated the mechanism by which these CA mutations block infectivity. We show that mutations in the hydrophobic residues (but not in Asp51) severely reduce incorporation of CypA into mature and immature virions, although these residues are distant from the CypA binding loop. Mutant cores retain a much larger amount of CA than can be detected in the wild-type preparation, which might induce a defect in proper disassembly. Most importantly, analysis of isolated cores of all three mutants indicates that they contain almost no RT. Taken together, these findings can account for the failure of the three CA mutants to synthesize viral DNA following virus entry into cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, transfection, and RT assay.

HeLa and 293T cells were maintained as previously described (60) and were transfected by a modified calcium phosphate precipitation procedure as follows: 19 μl of 2 M CaCl2 was added to 5 μg of plasmid DNA diluted to a final volume of 140 μl. After they were mixed well and left on ice for 5 min, 159 μl of 2× buffer, containing 42 mM HEPES, 0.3 M NaCl, 1.8 mM Na2HPO4, and 10 mM KCl, was added, and the solution was mixed again and was left on ice for 20 min. The mixture was put into a culture dish containing 5 ml of medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium) with 10% fetal calf serum, and the entire solution was mixed gently; this was followed by addition of 15 μl of 10 mM chloroquine (Sigma). After incubation for 6 h at 37°C, 5 ml of fresh medium was added and incubation was continued for another 16 h. In some experiments, HeLa cells were transfected with the Trans IT transfection reagent (Mirus, Madison, Wis.), as recommended by the manufacturer. RT activity was detected by exogenous RT assay, as described by Freed et al. (24).

Plasmids.

The HIV-1 protease-positive (PR+) pNL4-3 clone (2) and the env-negative pNL4-3KFS subclone (23, 26), containing wild-type or mutant CA sequences, have been described previously (60). The W23A, F40A, and D51A CA mutations (60) were also inserted into a pNL4-3 PR− subclone (38), which contains a PR active-site mutation at amino acid 25 (D25N). This was accomplished by independently ligating individual BssHII-SpeI fragments from each of the mutants to the PR− clone, which had been digested with the same restriction endonuclease enzymes. Mutant CA sequences were verified by sequencing performed by the Biopolymer Lab (University of Maryland, College Park). The parent pNL4-3/PR− clone is referred to as “wild type” since the CA domain in Gag has the wild-type sequence.

Sucrose density gradient centrifugation.

Isolation of virus particles present in the supernatant fluids of transfected cells by sucrose density gradient centrifugation was performed essentially as described by Willey et al. (71). Briefly, the supernatants were filtered to remove unattached cells and cell debris and were then centrifuged at 120,000 × g in a Beckman SW41 rotor for 45 min at 4°C. The resulting viral pellets were carefully resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Virus core particles were prepared according to the procedures described by Kiernan et al. (43). Aliquots (100 μl) of the fresh virus suspension were mixed with an equal volume of 0.6% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) (vol/vol) and were incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Untreated or detergent-treated virus samples were layered on top of 20% to 70% (wt/wt) linear sucrose density gradients and were centrifuged in a Beckman SW55Ti rotor at 120,000 × g for 16 h at 4°C. Twelve 0.4-ml fractions were collected from the top of the tube and were assayed for exogenous RT activity. In addition, viral proteins were analyzed by Western blotting (see below). The density of each fraction (ρ) was determined by the formula ρ (grams/milliliter) = (2.6496 × η) − 2.5323, where η is the refractive index (19). Note that fraction 1 represents the material of lowest density, whereas fraction 12 represents the densest material.

Sucrose step gradient centrifugation.

Sucrose step gradients were prepared by using the procedures described by Khan et al. (41) with some modification. Briefly, 2.4 ml of a 20% sucrose (wt/wt) solution was layered over 2.2 ml of a 60% sucrose (wt/wt) solution. Two hundred microliters of 0.3% NP-40-treated-virus (see above) was added above the 20% sucrose layer. Samples were centrifuged at 4°C in a Beckman SW55Ti rotor for 60 min at 120,000 × g. Five fractions (fractions 1 to 4, 1 ml; and fraction 5, 0.8 ml), representing all of the material in the gradient, were collected from the top of the tube. Aliquots of each fraction were subjected to Western blot analysis (see below).

Analysis of protein composition of HIV-1 virions and cores.

For Western blot analysis, viral proteins present in the gradient fractions were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in 12% ProtoGels (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, Ga.) and were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.). The Western-Star chemiluminescence detection system (TROPIX Inc., Bedford, Mass.) was used. Blots were placed in contact with standard X-ray film. The densities of the protein bands were quantified with a laser densitometer by using a model PDS1-P90 instrument from Molecular Dynamics Inc., Sunnyvale, Calif.

Antibodies used for analysis of viral proteins.

The following HIV-1 antisera were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: HIV-1 neutralizing sera, which we will refer to as AIDS patient sera (catalog no. 1983 and 1984); HIV-1SF2 CA (p24) antiserum (catalog no. 4250); anti-MA (p17) (catalog no. 4811); and anti-RT (catalog no. 6195). The following primary antibodies were also used: rabbit anti-HIV-2 IN, which is cross-reactive with HIV-1 IN (44); rabbit anti-Vif (kindly provided by Klaus Strebel, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.); and rabbit anti-CypA (kindly provided by David Ott, SAIC Frederick, Inc., NCI at Frederick, Frederick, Md.). The secondary antibodies used were alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) and anti-human IgG, which are supplied with the Western-Star chemiluminescence detection system.

Immunoprecipitation analysis.

The procedures used for metabolic labeling of transfected HeLa cells with [35S]Cys (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc., St. Louis, Mo.) have been described previously (25, 38). Concentrated 35S-labeled HIV-1 virions were treated with NP-40, and the resulting virus core particles were isolated by centrifugation in linear 20-to-70% (wt/wt) sucrose gradients, as described above. Four 1.2-ml fractions were collected from the top. Each gradient fraction was mixed with an equal volume of lysis buffer (300 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10 mM iodoacetamide, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 200 μg of leupeptin/ml) and was then immunoprecipitated with AIDS patient serum and was subjected to SDS-PAGE on 10% acrylamide/AcrylAide gels (25, 70). Radioactivity present in protein bands was quantified by scanning densitometry with a FujiX BAS2000 Bio-Image analyzer.

Transmission electron microscopy.

The procedure for isolating HIV-1 cores for electron microscopic analysis was a modification of the method described by Accola et al. (1). Briefly, the supernatant fluid from HIV-1 pNL4-3-transfected 293T cells was sedimented at 120,00 × g in a Beckman SW55Ti rotor for 60 min at 4°C. The virus was resuspended in PBS in 1/100 of the original volume. Following treatment with 0.3% NP-40 (see above), the sample (200 μl) was loaded onto a sucrose step gradient (3.8 ml of 20% [wt/wt] sucrose layered over 1 ml of 30% [wt/wt] sucrose) and was sedimented at 100,000 × g in a Beckman SW55Ti rotor for 2 h at 4°C. The pellet containing HIV-1 cores was resuspended in 20 μl of 2.5% glutaraldehyde-PBS. Drops of the HIV-1 sample were applied to freshly glow-discharged carbon films mounted on electron microscope grids and were negatively stained with 1% uranyl acetate. The stained samples were examined in a FEI CM200 electron microscope.

RESULTS

Mutations in N-terminal hydrophobic residues block the incorporation of CypA.

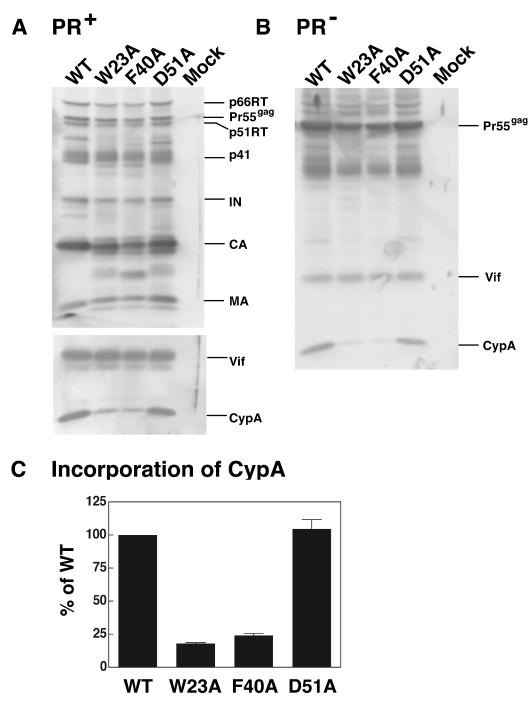

To further characterize the phenotype of the HIV-1 CA mutants, W23A, F40A, and D51A (see ribbon diagram in Fig. 1), we tested the ability of these mutants to incorporate CypA. In our initial experiments, we used the original wild-type and mutant clones (60), which contain the gene that encodes the viral PR (Fig. 2A). Western blot analysis of viral proteins indicated that the D51A mutation, which destroys the N-terminal salt bridge between Asp51 and Pro1 (64), had little or no effect on CypA incorporation. In sharp contrast, however, very low levels of CypA were detected in W23A and F40A virions, which bear mutations in conserved hydrophobic residues. To determine whether the block in CypA incorporation occurs prior to virus maturation, we also introduced the CA mutations into a PR− clone of pNL4-3 (38). Analysis of the proteins associated with wild-type and mutant PR− virions showed that similar amounts of Pr55gag and Vif protein were detected in each case (Fig. 2B). In addition, the level of CypA in D51A PR− virions was very close to that of the wild type. However, only very small amounts of CypA were found in PR− W23A and F40A virions.

FIG. 2.

Incorporation of CypA into mature and immature virus particles. HeLa cells were transfected with mutant and wild-type pNL4-3 (2) PR+ (A) and PR− (B) clones, as described in Materials and Methods. (A and B) Detection of virion-associated proteins by Western blot analysis. Virus particles were separated by SDS-PAGE in 12% gels and were analyzed by Western blotting. The blots were initially probed with anti-Vif and anti-CypA antibodies and were then reprobed with AIDS patient serum. The protein bands were visualized by chemiluminescence. The positions of the precursor and mature viral proteins are indicated. (C) Relative incorporation levels of CypA into mature virions. CypA in mature mutant and wild-type viral particles was quantified by scanning the band densities in the immunoblots and was normalized by calculating the ratios of CypA levels relative to the levels of IN; the ratio for the wild type was arbitrarily set at 100%. The data were plotted in a bar graph; error bars indicate standard deviation from three independent experiments. In this and all other figures, wild type is abbreviated as WT.

To obtain a more quantitative measure of the relative amounts of CypA incorporation in mature wild-type and mutant virions, the density of the bands was quantified by scanning densitometry and the values were normalized by determining the ratio of CypA incorporated relative to the level of IN; the wild-type value was set at 100% (Fig. 2C). As expected from inspection of the Western blots, incorporation of CypA by D51A was essentially equivalent to that of the wild type, whereas for W23A and F40A, incorporation was reduced ∼4- to 5-fold (∼18 and 24%, respectively) (Fig. 2C). Taken together, the results of Fig. 2 demonstrate that the mutations in the hydrophobic residues block the incorporation of CypA during virus assembly but before virus maturation. This finding is of special interest since the Trp and Phe residues are in helices I and II, respectively, distant from the CypA binding loop (Fig. 1; see below).

Protein composition of wild-type and mutant cores.

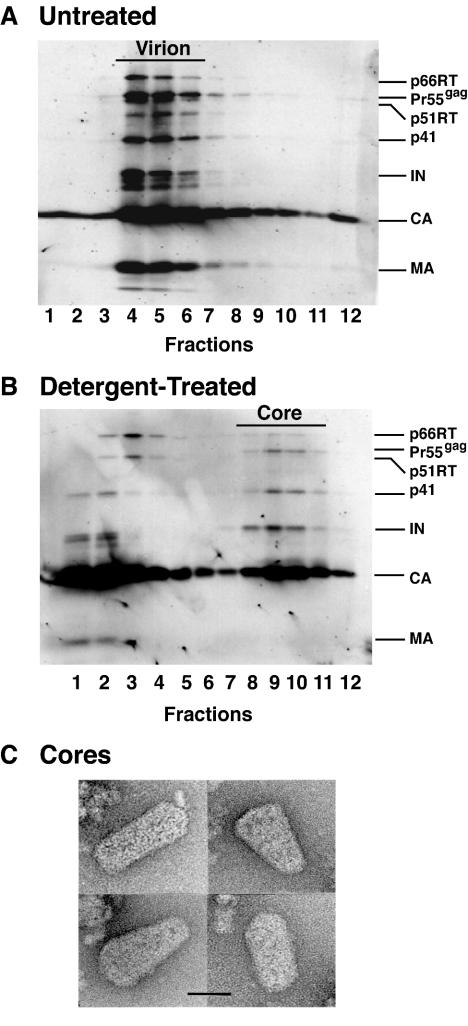

Previous results obtained with the three mutants suggested that they might have a defect in an early postentry step preceding reverse transcription (60). To investigate this possibility, we modeled virus disassembly by generating virus cores (mild detergent treatment of virions) and then sedimenting the samples in equilibrium linear sucrose density gradients (see Materials and Methods). The fractions obtained from gradients containing untreated (Fig. 3A) and detergent-treated (Fig. 3B) wild-type particles were subjected to Western blot analysis. The blots were initially probed with AIDS patient serum (Fig. 3A and B), and the identities of individual bands were confirmed by immunoblot with specific CA, RT, IN, and MA antisera (data not shown). Note that only traces of MA were detected in core fractions (Fig. 3B). As expected, without detergent treatment, the peak fractions (Fig. 3A, fractions 4 to 6) containing wild-type virions had a density of 1.14 to 1.16 g/ml, corresponding to the known density of intact retrovirus particles (data not shown). Following detergent treatment, a distinct peak of wild-type viral proteins was found at the density expected for retroviral cores (1.24 to 1.28 g/ml) (Fig. 3B, fractions 8 to 10; data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Western blot and electron microscopy analysis of purified wild-type HIV-1 virions and isolated cores. HIV-1 virions were harvested from HeLa cells transfected with the pNL4-3KFS plasmid containing the wild-type CA sequence and were concentrated by ultracentrifugation. Untreated (A) and detergent-treated (B) samples were layered onto 20% to 70% (wt/wt) linear sucrose density gradients and were sedimented, as described in Materials and Methods. Twelve fractions were collected from the top of the gradient. Virion- and core-associated proteins were identified by Western blot analysis with the use of AIDS patient serum. (C) Electron micrographs of HIV-1 wild-type core particles. The samples were prepared and were stained as described in Materials and Methods. Four representative images are shown. Scale bar, 50 nm.

For analysis by transmission electron microscopy, wild-type viral cores were isolated by sedimentation in a sucrose density step gradient (1) and were then negatively stained, as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 3C). Cone-shaped cores lacking the viral envelope were detected, as is characteristic of the cores of mature virions. In accord with previous observations (1, 45, 67), the cores exhibited heterogeneity in their exact size and shape. When the same conditions and procedures were used, recognizable cores could not be detected in any of the mutant samples, a result that was not unexpected since cores contained in mutant virions are very obviously aberrant (60).

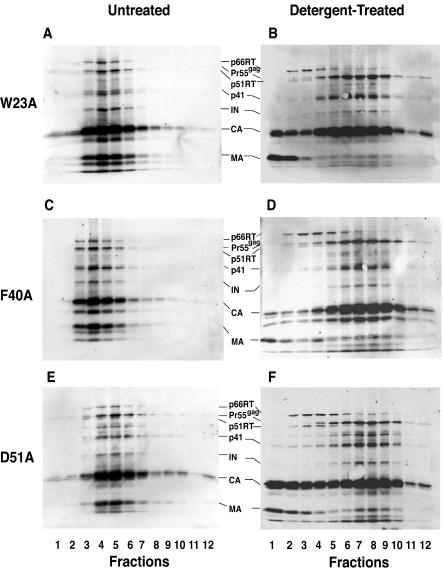

Figure 4 illustrates the protein profiles of untreated and detergent-treated mutant virus particles. Mutant virions (Fig. 4A, C, and E) had the same protein composition as wild-type virions (Fig. 3A), except that mutant CA proteins were partially degraded (Fig. 4A, C, and E) (60). Additionally, detergent-treated mutant (Fig. 4B, D, and F) and wild-type (Fig. 3B) particles exhibited similar protein profiles. Thus, CA was the major component present in wild-type and mutant cores, but as is the case with mutant virions (Fig. 4A, C, and E) (60), bands corresponding to degraded CA could be detected in mutant cores. Interestingly, Pr55gag, which migrates slightly slower than p51 RT, was most prominent in the core fractions (Fig. 3B and 4B, D, and F). IN was found almost exclusively in the core fractions of the wild type and mutants. Low levels of MA (more visible in the mutants [Fig. 4B, D, and F] than in the wild type [Fig. 3B]) could still be detected in the core fractions, in agreement with earlier reports (45, 67). Note that mutant virions and cores had densities that were similar to the corresponding densities of untreated and detergent-treated wild-type preparations, respectively (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Protein profiles of untreated and detergent-treated mutant particles. Mutant virions harvested from HeLa cells transfected with pNL4-3KFS plasmids containing mutant CA coding regions were concentrated by ultracentrifugation and were sedimented in linear sucrose density gradients without further treatment or following treatment with mild detergent, as described in the legend to Fig. 3 and in Materials and Methods. Western blot analysis with AIDS patient serum was used to identify virion- and core-associated proteins. Untreated virus: A, W23A; C, F40A; and E, D51A. Detergent-treated virus: B, W23A; D, F40A; and F, D51A.

It is of interest that the level of RT associated with wild-type cores (Fig. 3B, fractions 8 to 10) was substantially reduced compared with the amount in virions (Fig. 3A, fractions 4 to 6); this was also true for the mutants (compare Fig. 4A, C, and E with Fig. 4B, D, and F) (also, see below). In addition, inspection of the Western blot data revealed a major difference between wild-type and mutant cores. In the case of wild type, a significant amount of CA was found in the soluble fractions at the top of the gradient. In contrast, an unusually large amount of CA was found in mutant core fractions, while relatively small amounts of CA were detected in the low-density fractions. This is particularly obvious for mutants W23A and F40A (Fig. 4B and D).

Mutant cores retain an abnormally high level of CA.

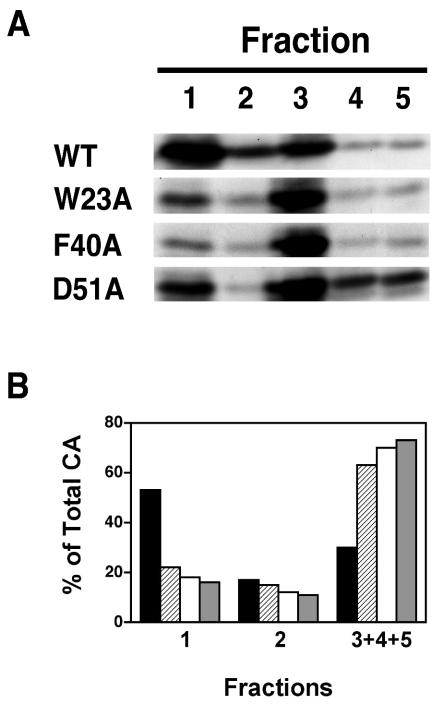

To further address the issue of CA retention in virus cores, NP-40-treated virus was sedimented in a sucrose step gradient, as described in Materials and Methods. Five fractions were collected from the top of each tube and were analyzed by Western blot. As shown in Fig. 5A, most of the wild-type CA was found in fraction 1, but for the mutants, most of the CA was found in fraction 3, with some CA also seen in fractions 4 and 5. The amounts of CA were quantified by densitometry, and in each case, the percentage of total CA protein in fractions 1 and 2 and the combined fractions 3 to 5 (core fractions) was plotted in a bar graph (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Retention of HIV-1 CA protein in wild-type and mutant viral cores. Detergent-treated virions were subjected to sedimentation in discontinuous sucrose gradients (step gradients), as described in Materials and Methods. Five fractions were collected from the top of the gradient. Aliquots of each fraction were subjected to Western blot analysis by using AIDS patient serum. (A) The protein bands representing HIV-1 CA are shown. Note that fraction 1 and fractions 3 to 5 from the step gradient contained the same complement of viral proteins seen in the soluble and core fractions, respectively, from the linear sucrose density gradients (Fig. 3B and 4B, D, and F; data not shown). (B) The amounts of CA were quantified and were plotted as the percentage of total CA protein recovered from the gradient. The values for fractions 1 and 2 represent the soluble and detergent-soluble fractions, respectively. The values for fractions 3, 4, and 5 were combined and represent the detergent-resistant core fractions. The samples were designated as follows in the bar graph: WT, black; W23A, diagonal stripes; F40A, white; and D51A, gray.

For the wild-type sample, 70% of the total CA protein was found in the soluble fractions, most of it in fraction 1 and a small amount in fraction 2; only about 30% of CA was present in the combined fractions 3 to 5. In contrast, mutant D51A had 73% of total CA protein in fractions 3 to 5. With the hydrophobic mutants W23A and F40A, the amounts of CA in the high-density combined fractions were also large; i.e., 63 and 70% of total CA remained associated with cores, respectively. These findings demonstrate that, in the case of the mutants, core-associated CA is unusually resistant to detergent.

Very small amounts of RT are associated with mutant cores.

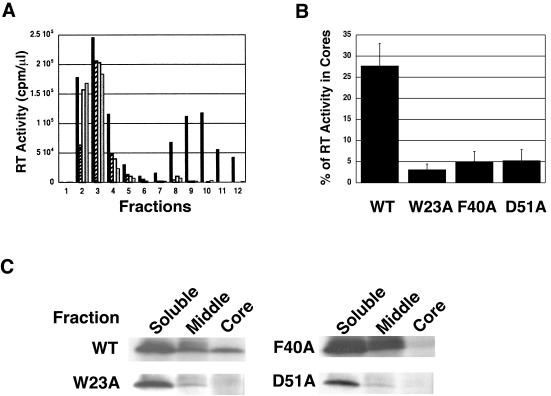

Western blot analysis of the sucrose density gradient fractions derived from wild-type and mutant detergent-treated virus particles (Fig. 3B and 4B, D, and F) indicated that most of the RT in these preparations was found in the soluble fractions and not in the core-containing fractions. To quantify the amount of RT associated with cores, our first approach was to measure the amount of RT activity in sucrose density gradient fractions obtained after equilibrium sedimentation of detergent-treated virions (Fig. 6A). The wild-type sample exhibited two peaks of RT activity: one in the low-density fractions, corresponding to RT released into the soluble fractions, and another, in the high-density fractions, representing RT retained in viral cores. However, for all three mutants, only one RT peak could be detected and this peak was located in the soluble fractions; only trace amounts of RT activity were detected in the core fractions. The percentage of RT activity associated with core fractions was quantified and was plotted in a bar graph (Fig. 6B). The data showed that 28% ± 5% of total RT activity was retained in wild-type cores, whereas 5% or less of total RT activity could be recovered from cores derived from the three CA mutants.

FIG. 6.

Retention of HIV-1 RT in wild-type and mutant viral cores. Virions harvested from the supernatants of transfected HeLa cells were treated with detergent and were sedimented through 20% to 70% (wt/wt) linear sucrose density gradients, as described in Materials and Methods. Aliquots of each fraction were assayed for RT activity. (A) RT activity plotted in a bar graph. The designation of the samples is as follows: WT, black; W23A, diagonal stripes; F40A, white; and D51A, gray. (B) RT activity in the core fractions (density equivalent to 1.24 to 1.28 g/ml) was quantified and was plotted as the percentage of total RT activity. Error bars indicate the standard deviation from three independent experiments. (C) Analysis of p66 RT metabolically labeled with [35S]Cys. 35S-labeled HIV-1 particles were concentrated and treated with NP-40 and were then sedimented in linear sucrose density gradients, as detailed in Materials and Methods. Four 1.2-ml fractions were collected from the top. In each case, fractions labeled “soluble” and “middle” correspond to soluble or detergent-soluble viral proteins, respectively, whereas the fraction labeled “core” corresponds to the core fraction. (Note that analysis of the bottom fraction is not shown.) Each fraction was immunoprecipitated with AIDS patient serum and was subjected to gel electrophoresis to separate core-associated proteins. Data for p66 RT are shown, since the p66 band is the most reliable marker for RT protein. Other viral proteins were also detected (data not shown), in accord with the findings depicted in Fig. 3B and 4B, D, and F.

To confirm these results, the amount of RT protein was estimated by immunoprecipitation analysis (Fig. 6C). Viral particles were metabolically labeled with [35S]Cys, treated with NP-40, and sedimented to equilibrium in linear sucrose density gradients, as described in Materials and Methods. Four fractions were collected, and viral proteins were immunoprecipitated with AIDS patient serum and separated by SDS-PAGE. The p66 RT bands in the soluble, middle, and core fractions are shown. Quantitation by PhosphorImager analysis indicated that, for the wild type, about 26% of the RT present in these three fractions could be detected in the core fraction. In contrast, only trace amounts (∼1%) of RT were found in the mutant core fraction. Note that the quantitation in Fig. 6C is in excellent agreement with the RT activity data in Fig. 6B. Interestingly, the amount of Pr160gag-pol in immature cores is the same for the wild type and the mutants (data not shown).

Collectively, the data in Fig. 6 demonstrate that wild-type cores retain easily detectable amounts of RT, whereas mutant cores contain levels of RT that are barely detectable in the RT activity and immunoprecipitation assays. These findings are highly significant, since the deficiency of RT in mutant cores correlates with the inability of the CA mutants to initiate reverse transcription in infected cells (60).

DISCUSSION

In earlier work, we described the phenotype associated with alanine substitution mutations in three conserved residues in the N-terminal domain of HIV-1 CA: Trp23, Phe40, and Asp51 (60). We found that mutant virions are noninfectious and lack a cone-shaped core and, despite having a functional RT, are unable to initiate reverse transcription in infected cells. These results suggested that the mutants are blocked in an early postentry event preceding reverse transcription. The present study focuses on elucidating the mechanism by which these CA mutations disrupt virus infectivity. Our approach was to model disassembly by isolating viral cores following treatment of virus particles with mild detergent. We now report that mutant core structures have unusual biochemical properties, i.e., a striking deficiency in RT and abnormally high retention of CA, which are likely to account for the failure of the mutants to synthesize viral DNA in vivo.

The phenotypes that we observe are presumably a reflection of significant changes in CA structure resulting from the alanine substitutions. For example, the D51A mutation destroys a salt bridge formed by Asp 51 and Pro1 in mature CA (31, 64). NMR analysis of the D51A protein indicates that the mutation results in destabilization of the N-terminal β-hairpin (64), which has a deleterious effect on assembly of conical cores in mature virions (60, 64) and on in vitro assembly of CA (64).

Although we do not have direct evidence for specific changes in the CA structure of the hydrophobic mutants, X-ray crystallographic analysis indicates that these residues are important for maintaining the stability of CA structure (53). The inability of W23A (helix I) and F40A (helix II) to incorporate CypA into virions (Fig. 2) is surprising, since these residues are distant from the CypA binding site (Fig. 1) and are buried deep within the hydrophobic core of the helical N-terminal CA structure (31, 53). Reduction in CypA packaging was also reported in earlier studies with a series of N-terminal CA deletion or insertion mutants, which lack changes in the CypA binding loop (11, 61). These results are consistent with a recent NMR study showing that CypA-catalyzed isomerization of the Gly89-Pro90 peptide bond involves chemical shifts in residues distal to the CypA binding loop (6) and also suggest that overall CA structure plays a key role in CypA binding and activity. The W23A and F40A mutations appear to have a profound effect on CA structure, which could involve global changes in protein conformation that prevent proper interactions with CypA. In contrast, the D51A mutation, while still causing structural defects (see above), seems to be less severe, since this mutation has little or no effect on CypA packaging (Fig. 2).

Now one may ask: what are the major consequences of structural distortions in CA and how do they impact the biochemical and biological activities of the virus? Clearly, the overall effect is a complete loss of infectivity (60). Although CypA incorporation is dramatically reduced in W23A and F40A virions and is a marker for defective CA structure (Fig. 2; see above), it does not appear to be the main reason for the loss of infectivity. This conclusion is based on the fact that a complete block in CypA incorporation in the absence of other defects causes only a modest delay in virus replication (61). In addition, D51A packages essentially normal levels of CypA (Fig. 2), while exhibiting other more severely altered phenotypic properties in common with the hydrophobic mutants. Rather, defects in mutant viral cores (see below) are more likely to be ultimately responsible for the noninfectious phenotype.

To address the question of core defects, we isolated wild-type and mutant cores by sedimentation in sucrose density gradients (Fig. 3 and 4). Detection of typical cone-shaped cores in wild-type peak gradient fractions following negative staining and transmission electron microscopy validates the experimental approach employed in this work (Fig. 3C). As mentioned above, recognizable core structures from mutant samples could not be detected in the electron microscope, which is not surprising since mutant virions contain cores that are clearly aberrant (60). However, it is of interest that, despite having an aberrant phenotype, mutant cores sediment with a density similar to that of wild-type cores in linear sucrose density gradients (data not shown), although the peak is reproducibly somewhat broader with the mutant samples (compare Fig. 3B with Fig. 4B, D, and F).

One of the striking results of this study is the finding that mutant cores retain abnormally high levels of CA (65 to 70% of total CA in step gradient fractions) (Fig. 5). In contrast, isolated wild-type cores retain 20 to 30% of total CA present in core preparations (Fig. 5) (1, 17, 19, 41, 45). Interestingly, mutants with single amino acid substitutions in certain HIV-1 N-terminal Pro residues have aberrant core morphology and also retain substantially increased levels of CA in pelleted cores (17). These findings demonstrate that core-associated CA in certain groups of mutants is highly resistant to detergent. Forshey et al. (19) have described two noninfectious CA mutants that have cone-shaped cores but release CA from isolated cores with a reduced rate and extent compared with wild-type cores in an in vitro disassembly assay. Abnormally high retention of CA in viral cores would be expected to interfere with the disassembly process, which in turn could affect synthesis of viral DNA.

Another major core defect that could impact the ability of mutant virions to initiate reverse transcription concerns the amount of core-associated RT (Fig. 6). The CA mutations under investigation here have no effect on the activity, expression, and packaging of RT in mature virions (60) or on the amount of Pr160gag-pol in cores of PR− (i.e., immature) particles (data not shown). However, using an assay for exogenous RT activity or measuring the amount of immunoprecipitated 35S-labeled RT protein, we find that mutant cores isolated from mature virions retain 5% or less of total RT in fractions from sucrose density gradients. Under the same conditions, ∼30% of total RT is associated with wild-type cores (Fig. 6). In the literature, some reports show that virions and cores contain similar amounts of RT (45, 67), while other work indicates that there is less RT in cores than in virions (1, 19, 41). In an interesting parallel to our findings, Cairns and Craven (10) have shown that, after detergent treatment of wild-type Rous sarcoma virus particles, 30% of RTα and 40% of RTβ were associated with the pellet, whereas similar treatment of a CA mutant with a single amino acid change in the major homology region led to complete solubilization of RTα and only ∼5% of RTβ still remaining with the pellet.

Taken together, these findings support the conclusion that RT is loosely associated with wild-type viral cores and that only trace amounts of RT are present in core structures of certain CA mutants. In contrast, IN has a stable association with wild-type (Fig. 3B) (1, 19, 41, 45, 67) and mutant (Fig. 4B, D, and F) cores. The “topography” of individual components in viral cores is not known. However, image reconstruction analysis shows that the CA lattice structure is quite open (48) and this feature might play a role in RT release from cores. The extent to which RT is detected in ribonucleoprotein complexes from infected cells can vary (9, 15, 16, 39, 42, 52), presumably because of differences in the conditions of isolation. However, it is of interest that, in one case where RT was detected (16), it was found almost entirely in low-density sucrose gradient fractions, dissociated from viral DNA, early in infection.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the D51A mutation, which disrupts the salt bridge with Pro1, and the W23A and F40A mutations, which would be expected to destabilize the coiled-coil-like structure within the N-terminal domain of HIV-1 CA, result in loss of infectivity that is associated with severe defects in the architecture and protein composition of viral cores and failure to synthesize viral DNA postentry. Interestingly, this phenotype is moderated if Phe, rather than Ala, replaces Trp at position 23 (S. Tang et al., unpublished data). Our findings clearly reveal a crucial role for the conserved hydrophobic residues in HIV-1 replication and suggest that the hydrophobic core represents a potential new target for antiviral drugs and other therapeutic approaches for combating the AIDS epidemic.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to David Ott and Klaus Strebel for their generous gifts of anti-CypA and anti-Vif sera, respectively. We also thank Akira Ono for helpful discussions, Zhonglin Yang for generating the ribbon diagram used to illustrate the N-terminal CA domain, and Alan Rein for critical reading of the manuscript.

A.C.S. acknowledges support from the NIH Intramural AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Accola, M. A., Å. Öhagen, and H. G. Göttlinger. 2000. Isolation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cores: retention of Vpr in the absence of p6gag. J. Virol. 74:6198-6202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adachi, A., H. E. Gendelman, S. Koenig, T. Folks, R. Willey, A. Rabson, and M. A. Martin. 1986. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J. Virol. 59:284-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agresta, B. E., and C. A. Carter. 1997. Cyclophilin A-induced alterations of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 CA protein in vitro. J. Virol. 71:6921-6927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aiken, C. 1997. Pseudotyping human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) by the glycoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus targets HIV-1 entry to an endocytic pathway and suppresses both the requirement for Nef and the sensitivity to cyclosporin A. J. Virol. 71:5871-5877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alin, K., and S. P. Goff. 1996. Amino acid substitutions in the CA protein of Moloney murine leukemia virus that block early events in infection. Virology 222:339-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosco, D. A., E. Z. Eisenmesser, S. Pochapsky, W. I. Sundquist, and D. Kern. 2002. Catalysis of cis/trans isomerization in native HIV-1 capsid by human cyclophilin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:5247-5252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowzard, J. B., J. W. Wills, and R. C. Craven. 2001. Second-site suppressors of Rous sarcoma virus CA mutations: evidence for interdomain interactions. J. Virol. 75:6850-6856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braaten, D., E. K. Franke, and J. Luban. 1996. Cyclophilin A is required for an early step in the life cycle of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 before the initiation of reverse transcription. J. Virol. 70:3551-3560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bukrinsky, M. I., N. Sharova, T. L. McDonald, T. Pushkarskaya, W. G. Tarpley, and M. Stevenson. 1993. Association of integrase, matrix, and reverse transcriptase antigens of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with viral nucleic acids following acute infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:6125-6129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cairns, T. M., and R. C. Craven. 2001. Viral DNA synthesis defects in assembly-competent Rous sarcoma virus CA mutants. J. Virol. 75:242-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiu, H.-C., F.-D. Wang, S.-Y. Yao, and C.-T. Wang. 2002. Effects of gag mutations on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particle assembly, processing, and cyclophilin A incorporation. J. Med. Virol. 68:156-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cimarelli, A., and J.-L. Darlix. 2002. Assembling the human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59:1166-1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dietrich, L., L. S. Ehrlich, T. J. LaGrassa, D. Ebbets-Reed, and C. Carter. 2001. Structural consequences of cyclophilin A binding on maturational refolding in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid protein. J. Virol. 75:4721-4733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorfman, T., A. Bukovsky, Å. Öhagen, S. Höglund, and H. G. Göttlinger. 1994. Functional domains of the capsid protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 68:8180-8187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farnet, C. M., and W. A. Haseltine. 1991. Determination of viral proteins present in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 preintegration complex. J. Virol. 65:1910-1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fassati, A., and S. P. Goff. 2001. Characterization of intracellular reverse transcription complexes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 75:3626-3635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzon, T., B. Leschonsky, K. Bieler, C. Paulus, J. Schröder, H. Wolf, and R. Wagner. 2000. Proline residues in the HIV-1 NH2-terminal capsid domain: structure determinants for proper core assembly and subsequent steps of early replication. Virology 268:294-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forshey, B. M., and C. Aiken. 2003. Disassembly of human immunodeficiency vius type 1 cores in vitro reveals association of Nef with the subviral ribonucleoprotein complex. J. Virol. 77:4409-4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forshey, B. M., U. von Schwedler, W. I. Sundquist, and C. Aiken. 2002. Formation of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 core of optimal stability is crucial for viral replication. J. Virol. 76:5667-5677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franke, E. K., and J. Luban. 1996. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by cyclosporine A or related compounds correlates with the ability to disrupt the Gag-cyclophilin A interaction. Virology 222:279-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franke, E. K., H. E. H. Yuan, and J. Luban. 1994. Specific incorporation of cyclophilin A into HIV-1 virions. Nature 372:359-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freed, E. O. 1998. HIV-1 gag proteins: diverse functions in the virus life cycle. Virology 251:1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freed, E. O., E. L. Delwart, G. L. Buchschacher, Jr., and A. T. Panganiban. 1992. A mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein gp41 dominantly interferes with fusion and infectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:70-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freed, E. O., G. Englund, and M. A. Martin. 1995. Role of the basic domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix in macrophage infection. J. Virol. 69:3949-3954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freed, E. O., and M. A. Martin. 1994. Evidence for a functional interaction between the V1/V2 and C4 domains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein gp120. J. Virol. 68:2503-2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freed, E. O., and M. A. Martin. 1995. Virion incorporation of envelope glycoproteins with long but not short cytoplasmic tails is blocked by specific, single amino acid substitutions in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix. J. Virol. 69:1984-1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gamble, T. R., F. F. Vajdos, S. Yoo, D. K. Worthylake, M. Houseweart, W. I. Sundquist, and C. P. Hill. 1996. Crystal structure of human cyclophilin A bound to the amino-terminal domain of HIV-1 capsid. Cell 87:1285-1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gamble, T. R., S. Yoo, F. F. Vajdos, U. K. von Schwedler, D. K. Worthylake, H. Wang, J. P. McCutcheon, W. I. Sundquist, and C. P. Hill. 1997. Structure of the carboxyl-terminal dimerization domain of the HIV-1 capsid protein. Science 278:849-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ganser, B. K., S. Li, V. Y. Klishko, J. T. Finch, and W. I. Sundquist. 1999. Assembly and analysis of conical models for the HIV-1 core. Science 283:80-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gelderblom, H. R. 1991. Assembly and morphology of HIV: potential effect of structure on viral function. AIDS 5:617-637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gitti, R. K., B. M. Lee, J. Walker, M. F. Summers, S. Yoo, and W. I. Sundquist. 1996. Structure of the amino-terminal core domain of the HIV-1 capsid protein. Science 273:231-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grättinger, M., H. Hohenberg, D. Thomas, T. Wilk, B. Müller, and H.-G. Kräusslich. 1999. In vitro assembly properties of wild-type and cyclophilin-binding defective human immunodeficiency virus capsid proteins in the presence and absence of cyclophilin A. Virology 257:247-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grewe, C., A. Beck, and H. R. Gelderblom. 1990. HIV: early virus-cell interactions. J. Acquired Immune Defic. Syndr. 3:965-974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gross, I., H. Hohenberg, C. Huckhagel, and H.-G. Kräusslich. 1998. N-terminal extension of human immunodeficiency virus capsid protein converts the in vitro assembly phenotype from tubular to spherical particles. J. Virol. 72:4798-4810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gross, I., H. Hohenberg, T. Wilk, K. Wiegers, M. Grättinger, B. Müller, S. Fuller, and H.-G. Kräusslich. 2000. A conformational switch controlling HIV-1 morphogenesis. EMBO J. 19:103-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henderson, L. E., M. A. Bowers, R. C. Sowder II, S. A. Serabyn, D. G. Johnson, J. W. Bess, Jr., L. O. Arthur, D. K. Bryant, and C. Fenselau. 1992. Gag proteins of the highly replicative MN strain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: posttranslational modifications, proteolytic processings, and complete amino acid sequences. J. Virol. 66:1856-1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howard, B. R., F. F. Vajdos, S. Li, W. I. Sundquist, and C. P. Hill. 2003. Structural insights into the catalytic mechanism of cyclophilin A. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10:475-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang, M., J. M. Orenstein, M. A. Martin, and E. O. Freed. 1995. p6Gag is required for particle production from full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 molecular clones expressing protease. J. Virol. 69:6810-6818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karageorgos, L., P. Li, and C. Burrell. 1993. Characterization of HIV replication complexes early after cell-to-cell infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 9:817-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan, M., M. Garcia-Barrio, and M. D. Powell. 2003. Treatment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virions depleted of cyclophilin A by natural endogenous reverse transcription restores infectivity. J. Virol. 77:4431-4434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khan, M. A., C. Aberham, S. Kao, H. Akari, R. Gorelick, S. Bour, and K. Strebel. 2001. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif protein is packaged into the nucleoprotein complex through an interaction with viral genomic RNA. J. Virol. 75:7252-7265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khiytani, D. K., and N. J. Dimmock. 2002. Characterization of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 pre-integration complex in which the majority of the cDNA is resistant to DNase I digestion. J. Gen. Virol. 83:2523-2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kiernan, R. E., A. Ono, and E. O. Freed. 1999. Reversion of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix mutation affecting Gag membrane binding, endogenous reverse transcriptase activity, and virus infectivity. J. Virol. 73:4728-4737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klutch, M., A. M. Woerner, C. J. Marcus-Sekura, and J. G. Levin. 1998. Generation of HIV-1/HIV-2 cross-reactive peptide antisera by small sequence changes in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and integrase immunizing peptides. J. Biomed. Sci. 5:192-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kotov, A., J. Zhou, P. Flicker, and C. Aiken. 1999. Association of Nef with the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 core. J. Virol. 73:8824-8830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kraulis, P. J. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structues. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24:946-950. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lanman, J., T. T. Lam, S. Barnes, M. Sakalian, M. R. Emmett, A. G. Marshall, and P. E. Prevelige, Jr. 2003. Identification of novel interactions in HIV-1 capsid protein assembly by high-resolution mass spectrometry. J. Mol. Biol. 325:759-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li, S., C. P. Hill, W. I. Sundquist, and J. T. Finch. 2000. Image reconstructions of helical assemblies of the HIV-1 CA protein. Nature 407:409-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luban, J., K. L. Bossolt, E. K. Franke, G. V. Kalpana, and S. P. Goff. 1993. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein binds to cyclophilins A and B. Cell 73:1067-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mayo, K., D. Huseby, J. McDermott, B. Arvidson, L. Finlay, and E. Barklis. 2003. Retrovirus capsid protein assembly arrangments. J. Mol. Biol. 325:225-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mervis, R. J., N. Ahmad, E. P. Lillehoj, M. G. Raum, F. H. R. Salazar, H. W. Chan, and S. Venkatesan. 1988. The gag gene products of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: alignment within the gag open reading frame, identification of posttranslational modifications, and evidence for alternative gag precursors. J. Virol. 62:3993-4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miller, M. D., C. M. Farnet, and F. D. Bushman. 1997. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 preintegration complexes: studies of organization and composition. J. Virol. 71:5382-5390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Momany, C., L. C. Kovari, A. J. Prongay, W. Keller, R. K. Gitti, B. M. Lee, A. E. Gorbalenya, L. Tong, J. McClure, L. S. Ehrlich, M. F. Summers, C. Carter, and M. G. Rossmann. 1996. Crystal structure of dimeric HIV-1 capsid protein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 3:763-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ott, D. E., L. V. Coren, D. G. Johnson, R. C. Sowder II, L. O. Arthur, and L. E. Henderson. 1995. Analysis and localization of cyclophilin A found in the virions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 MN strain. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 11:1003-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reicin, A. S., A. Ohagen, L. Yin, S. Hoglund, and S. P. Goff. 1996. The role of Gag in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virion morphogenesis and early steps of the viral life cycle. J. Virol. 70:8645-8652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reicin, A. S., S. Paik, R. D. Berkowitz, J. Luban, I. Lowy, and S. P. Goff. 1995. Linker insertion mutations in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag gene: effects on virion particle assembly, release, and infectivity. J. Virol. 69:642-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Swanstrom, R., and J. W. Wills. 1997. Synthesis, assembly, and processing of viral proteins, p. 263-334. In J. M. Coffin, S. H. Hughes, and H. E. Varmus (ed.), Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. [PubMed]

- 58.Tang, C., E. Loeliger, I. Kinde, S. Kyere, K. Mayo, E. Barklis, Y. Sun, M. Huang, and M. F. Summers. 2003. Antiviral inhibition of the HIV-1 capsid protein. J. Mol. Biol. 327:1013-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tang, C., Y. Ndassa, and M. F. Summers. 2002. Structure of the N-terminal 283-residue fragment of the immature HIV-1 Gag polyprotein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:537-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tang, S., T. Murakami, B. E. Agresta, S. Campbell, E. O. Freed, and J. G. Levin. 2001. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 N-terminal capsid mutants that exhibit aberrant core morphology and are blocked in initiation of reverse transcription in infected cells. J. Virol. 75:9357-9366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thali, M., A. Bukovsky, E. Kondo, B. Rosenwirth, C. T. Walsh, J. Sodroski, and H. G. Göttlinger. 1994. Functional association of cyclophilin A with HIV-1 virions. Nature 372:363-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Turner, B. G., and M. F. Summers. 1999. Structural biology of HIV. J. Mol. Biol. 285:1-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vogt, V. M. 1997. Retroviral virions and genomes, p. 27-69. In J. M. Coffin, S. H. Hughes, and H. E. Varmus (ed.), Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. [PubMed]

- 64.von Schwedler, U. K., T. L. Stemmler, V. Y. Klishko, S. Li, K. H. Albertine, D. R. Davis, and W. I. Sundquist. 1998. Proteolytic refolding of the HIV-1 capsid protein amino-terminus facilitates viral core assembly. EMBO J. 17:1555-1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.von Schwedler, U. K., K. M. Stray, J. E. Garrus, and W. I. Sundquist. 2003. Functional surfaces of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid protein. J. Virol. 77:5439-5450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang, C.-T., and E. Barklis. 1993. Assembly, processing, and infectivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag mutants. J. Virol. 67:4264-4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Welker, R., H. Hohenberg, U. Tessmer, C. Huckhagel, and H.-G. Kräusslich. 2000. Biochemical and structural analysis of isolated mature cores of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 74:1168-1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wiegers, K., G. Rutter, H. Kottler, U. Tessmer, H. Hohenberg, and H.-G. Kräusslich. 1998. Sequential steps in human immunodeficiency virus particle maturation revealed by alterations of individual Gag polyprotein cleavage sites. J. Virol. 72:2846-2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wiegers, K., G. Rutter, U. Schubert, M. Grättinger, and H.-G. Kräusslich. 1999. Cyclophilin A incorporation is not required for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particle maturation and does not destabilize the mature capsid. Virology 257:261-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Willey, R. L., J. S. Bonifacino, B. J. Potts, M. A. Martin, and R. D. Klausner. 1988. Biosynthesis, cleavage, and degradation of the human immunodeficiency virus 1 envelope glycoprotein gp160. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:9580-9584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Willey, R. L., T. Klimkait, D. M. Frucht, J. S. Bonifacino, and M. A. Martin. 1991. Mutations within the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp160 envelope glycoprotein alter its intracellular transport and processing. Virology 184:319-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wills, J. W., and R. C. Craven. 1991. Form, function, and use of retroviral Gag proteins. AIDS 5:639-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yoo, S., D. G. Myszka, C. Yeh, M. McMurray, C. P. Hill, and W. I. Sundquist. 1997. Molecular recognition in the HIV-1 capsid/cyclophilin A complex. J. Mol. Biol. 269:780-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]