Abstract

As a reducing agent, ascorbate serves as an antioxidant. However, its reducing function can in some settings initiate an oxidation cascade, i.e. appear to be a “pro-oxidant”. This dichotomy also appears to hold when ascorbate is present during photosensitization. Ascorbate can react with singlet oxygen producing hydrogen peroxide. Thus, if ascorbate is present during photosensitization the formation of highly diffusible hydrogen peroxide could enhance the toxicity of the photodynamic action. On the other side, ascorbate could decrease toxicity by converting highly reactive singlet oxygen to less reactive hydrogen peroxide, which can be removed via peroxide-removing systems such as glutathione and catalase. To test the influence of ascorbate on photodynamic treatment we incubated leukemia cells (HL-60 and U937) with ascorbate and a photosensitizer (verteporfin, VP) and examined: AscH− uptake; levels of glutathione; changes in membrane permeability; cell growth; and toxicity. Accumulation of VP was similar in each cell line. Under our experimental conditions, HL-60 cells were found to accumulate less ascorbate and have lower levels of intracellular GSH compared to U937 cells. Without added ascorbate, HL-60 cells were more sensitive to VP and light treatment than U937 cells. When cells were exposed to VP and light ascorbate acted as an antioxidant in U937 cells, while it was a “pro-oxidant” for HL-60 cells. One possible mechanism to explain these observations is that HL-60 cells express myeloperoxidase activity, while in U937 cells it is below detection limit. Inhibition of myeloperoxidase activity with 4-aminobenzoic acid hydrazide (4-ABAH) had minimal influence on the phototoxicity of VP in HL-60 in the absence of ascorbate. However, 4-ABAH decreased the toxicity of ascorbate on HL-60 cells during VP-photosensitization, but had no affect on ascorbate toxicity in U937 cells. These data demonstrate that ascorbate increases hydrogen peroxide production by VP and light. This hydrogen peroxide activates MPO, producing toxic oxidants. These observations suggest that in some settings, ascorbate may enhance the toxicity of photodynamic action.

Keywords: photosensitization, HL-60 cells, U937 cells, ascorbic acid, oxidative stress

Introduction

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a novel treatment for cancer that induces oxidative stress primarily through the light-mediated production of singlet oxygen [1]. Singlet oxygen and related reactive oxygen species initiate oxidations that damage malignant tissue. The generation of singlet oxygen requires oxygen, visible light, and a photosensitizing drug. Light exposure activates the drug and in the presence of O2 produces singlet oxygen through Type II energy transfer processes [2]. Benzoporphyrin derivative monoacid ring A (BPD-MA), the active component of Verteporfin (VP) is a second-generation photosensitizer that has been proposed for leukemic bone marrow purging [3], for treatment of human psoriasis [4, 5], and is in wide use for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) [6]. Using animal models, Verteporfin shows promise for cancer treatment [7, 8, 9, 10]. Verteporfin, as a lipid formulated drug preparation, localizes mainly in lipophilic structures of the mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum with a small fraction distributed within the cytoplasm [11]. The biological mechanism of phototoxicity in vitro appears in most cases to be mitochondrial induced apoptosis [12], as seen in human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 [13], mouse P815 mastocytoma [14], and HeLa epidermoid carcinoma [15].

Ascorbate (vitamin C) is a water-soluble, small molecule antioxidant and reducing co-factor. As a vitamin, it must be taken up from the diet; it is found in almost all tissues [16]. It’s concentration in the blood of normal individuals varies from 5 to 90 μM [17]. However, it is actively accumulated in human tissues to a concentration as much as 50-fold greater than plasma [18]. In vitro cancer cells also accumulate ascorbate [19, 20]. There are data demonstrating higher levels of vitamin C in neoplasms than in adjacent normal tissue [21]. Ascorbate can initiate new oxidation cascades [22] and thereby enhance the toxicity of photosensitization processes by forming H2O2 upon its reaction with singlet oxygen (1O2) [23], k = 3 × 108 M−1 s−1 [24, 25]

Singlet oxygen (1O2) is thought to have a very short lifetime (≈100 ns) within lipid membranes [26] and thus a very limited diffusion distance compared to H2O2. Hydrogen peroxide is a highly diffusible oxidant that could expand the damage inflicted by 1O2. It has been shown that 1O2 will readily diffuse from the interior of, or across a hydrophobic volume, such as a membrane, into the neighboring aqueous space [26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35]. Most of the 1O2 generated in the membrane would diffuse from the membrane and react with components in the water space [29, 36, 37]. Recent results studying the decay of 1O2 in single cells suggest its lifetime to be more than an order of magnitude greater in the water space of cells than previously thought [34, 35]. Thus singlet oxygen would have a diffusion distance greater than currently accepted, although much less than H2O2. Using the simple diffusion equation (r = (6Dt)0.5, where r is the diffusion distance, D the diffusion coefficient and t is time), an increase in the lifetime of 1O2 by a factor of 10 would increase the diffusion distance by 100.5. This would result in the effective reaction volume of singlet oxygen increasing by a factor of >30 (i.e., 100.5)3. Thus, singlet oxygen produced in one structure of a cell will diffuse a significant distance in the water space of cells [34, 35]. Thus possible reactions with aqueous solutes such as ascorbate could be significant. The reaction of ascorbate with singlet oxygen could lead to two opposite effects,

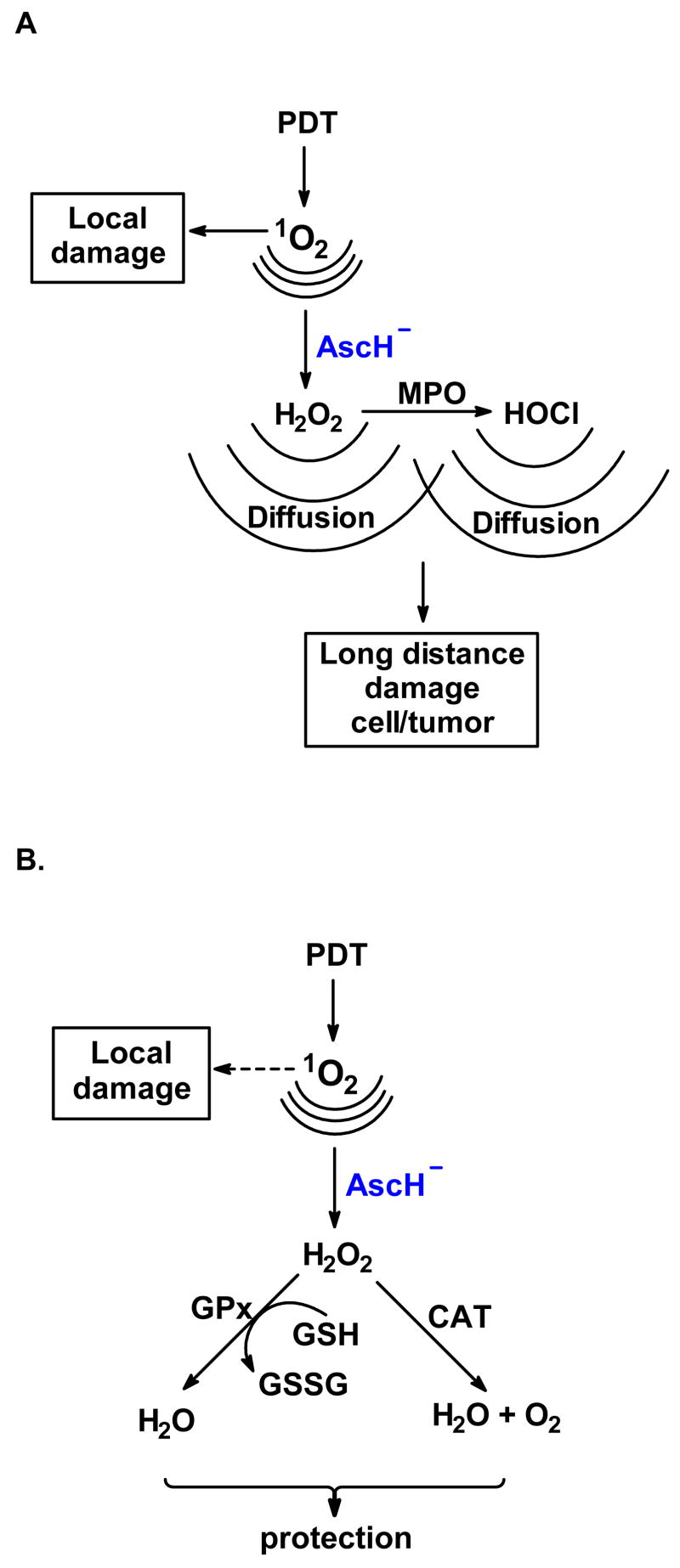

“pro-oxidant” effect: ascorbate enhances the toxicity of photodynamic action because the highly diffusible H2O2 can damage targets in different locations; the H2O2 will react with a different set of targets and can also lead to hydroxyl radical formation via Fenton chemistry [38, 39, 40] as well as the initiation of oxidative cascades via activation of heme-peroxidase enzymes [41], Figure 1A.

antioxidant effect: ascorbate can chemically quench singlet oxygen in the water space, thereby protecting aqueous targets that are sensitive to 1O2; this quenching would also limit the diffusion of 1O2 back into the membrane, thereby protecting membrane lipids and proteins. Although H2O2 is highly diffusible, protection would imply that the H2O2 formed would be less toxic than singlet oxygen, perhaps because of a robust antioxidant network that removes hydroperoxides, Figure 1B.

Figure 1. AscH− can enhance or protect against the oxidations of PDA.

A large percentage of the 1O2 produced in or near a membrane will diffuse out of the membrane and react with electron-rich molecules in the water space [29,36, 37]. Ascorbate (AscH−) can react with part of the singlet oxygen that diffuses out of the membrane into the aqueous phase, converting it into H2O2.

A. Ascorbate can enhance the damage initiated by PDA: H2O2 can produce different damage than 1O2 and can diffuse further, thereby spreading the damage throughout the tumor (bystander effect). Some of this H2O2 can be a substrate for myeloperoxidase resulting in the formation of hypochlorous acid. Thus, by converting part of the 1O2 to H2O2 ascorbate creates additional reactive oxygen species that can enhance the destruction of the tumor.

B. Ascorbate can protect against the damage initiated by PDA: Converting some of the singlet oxygen to H2O2 can result in a decrease of local damage, i.e. oxidation of lipids or proteins. Further, H2O2 can be converted to water by peroxide removing systems. These scenarios would lead to protection against photodynamic action.

Which of these two scenarios is dominant will probably depend on the activity of the peroxide removing enzyme systems as well as the levels of the small molecule antioxidants ascorbate and glutathione. Both of these antioxidants are present at high levels in cells in vivo. Glutathione is key to the removal of H2O2.

Combining PDT with high concentrations of AscH− might enhance the efficacy of PDT in certain settings. Evidence that ascorbate can increase the toxicity induced by photodynamic action with different photosensitizers has been demonstrated with both in vitro and [42, 43, 44] in vivo models [45, 46, 47, 48]. For example, ascorbate enhanced phthalocyanine-sensitized photo hemolysis of human erythrocytes [42]. It has also been shown that phthalocyanine and sodium ascorbate significantly slowed the growth of Ehrlich carcinoma in mice in comparison with the suppressive effect of PDT only [49]. But it’s still unclear why and in what settings ascorbate realizes its pro- or antioxidant capacities. To expand our knowledge on the conditions that allow ascorbate to initiate new oxidation cascades during photosensitization, we incubated leukemia cells with AscH− and a photosensitizer (verteporfin) and upon exposure to light determined: AscH− uptake; changes in membrane permeability; cell growth; and toxicity.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Verteporfin is produced by Novartis, (Switzerland) as a lipid-formulated photosensitizer (BPD-MA or VP) containing 13% BPD-MA. Propidium iodide, catalase, 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine, dimethylformamide, acetic acid, sodium acetate, and (4-ABAH) were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); Annexin V-FITC reagent and Annexin binding buffer were from Biovision Inc. (Mountain View, CA). Ascorbic acid (EMD Chemical Inc. - Merck, Gibbstown, NJ, USA) was dissolved in phosphate buffer (KH2PO4, 1.15 mM; Na2HPO4, 2.88 mM; NaCl, 154 mM) pH 7.4 just before the start of the experiments. Adventitious transition metals were removed from PBS with chelating resin (Sigma) using the batch method [50].

Cell culture

The human promyelocytic leukemia cell lines (HL-60 and U937) were obtained from ATCC (Rockville, MD, USA). Both cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (without phenol red) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (medium-10), 2 mM glutamine, penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL), all from GIBCO® (Grand Island, NY). Both cell lines were incubated at 37°C in a 95% humidity atmosphere under 5% CO2. Cells from passages 7–25 were used for the experiments. In cell growth experiments cells were counted daily using a Coulter® Counter Z2 (Beckman Coulter Inc, Fullerton, CA). When cells were incubated with ascorbate or with verteporfin, agents were added to the cell suspension (density 1 × 106/mL) in medium-2 (growth medium with 2% FBS) for 1 h, 37°C. Medium-2 was used because the uptake of VP was higher than in medium-10 [13, 14].

Photodynamic treatment

Aliquots of Verteporfin (2 mg/mL) in DMSO were stored at −80°C. For PDA experiments Verteporfin was added to medium-2 (10 ng/mL equivalent to 1.8 nM) with or with AscH− and cells incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were washed twice with RPMI 1640 and 7.5 × 106 cells were resuspended in 11 mL RPMI 1640 and placed into 100 mm dishes. Cells were then exposed to white light on a light box equipped with 2 linear 30 W daylight fluorescent bulbs and a UV light-removing surface. The intensity of the white light was measured with a NIST Traceable Radiometer Photometer with the probe for visible light from International Light Inc., Newburyport, MA. The light intensity was measured for all areas of the light box surface and samples were placed only in areas that had the same fluence rate, 2.2 mW cm−2. Cells were exposed to light for 10–20 min translating into a light dose of 1.32 – 2.62 J cm−2. Temperature in the cell suspensions increased no more than 1.5°C during treatment.

Verteporfin (BPD-MA) uptake

Fluorescence measurements were performed to determine the uptake of Verteporfin by leukemia cells. Cells were incubated with verteporfin (1.8 nM) in medium-2 for 1 h [51]. Cells (5 × 107/mL) were then washed twice with PBS and the cell pellet was resuspended in 0.75 mL PBS containing 2% Triton X-100. To lyze the cells, the cell suspension was freeze-thawed (3 times) in dry ice/EtOH and water (37°C). Methanol (0.5 mL) was then added to the cell suspension to precipitate the protein. The suspension was centrifuged and the supernatant stored at −20°C. Fluorescence of BPD-MA was measured using a Perkin Elmer LS50B Luminescence Spectrometer. The BPD-MA was excited at 430 nm and the emission spectrum was recorded, 650 – 750 nm. The concentration of standards of Verteporfin in PBS was determined with UV-Vis, ε689 = 1.35 × 104 M−1 cm−1 [52].

Trypan Blue Assay for membrane permeability

Membrane permeability was determined using trypan blue exclusion. Trypan blue dye solution (0.2%) was added to the cell suspension (1:1 v,v) and stained cells counted under a light microscope using a hematocytometer.

GSH measurements

GSH and GSSG were measured as described by Baker et al. [53]. GSSG is reduced by glutathione disulfide reductase and the total GSH of the sample is oxidized with DTNB (5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid)) (2GSH + DTNB → GSSG + 2TNB). Formation of TNB is measured at 405 nm with a microtiter plate reader. To determine [GSSG], the sample is first treated with 2-vinylpyridine, a compound that conjugates with GSH inhibiting its reaction with DTNB. The GSSG in the sample is then reduced by glutathione disulfide reductase in the presence of NADPH and oxidized with DTNB. Standards were made in 5% sulfosalicylic acid (SSA). GSH standards (10–100 μM), blank, or samples (30 μL) were added to a 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plate (Costar 3596). Triethanolamine (20 μL of a 0.657 M solution) was added to each well. Two hundred microliter enzyme cocktail (NADPH (0.298 mM) prepared in sodium-phosphate buffer, DTNB (6 mM), GR equivalent to 125 units), was added to each well. The plate was read at 405 nm with a microtiter plate reader (Tecan Spectrafluor Plus) using a kinetic analysis protocol (10 cycles). The GSHT concentration was calculated from the GSH standard curve and normalized against cell number. GSTT is used as the level of GSSG was always low in comparison to GSH and changes were small after all treatments. GSHT was calculated as [GSH] + 2[GSSG], the 2 being present to convert to equivalents of GSH.

Intracellular Hydrogen Peroxide

Steady-state levels of intracellular H2O2 were estimated using a sensitive assay based on the rate of inhibition of catalase by 3-amino-1H-1,2,4-triazole (AT, 20 mM) [54, 55, 56]. For catalase-activity assays cell pellets were thawed rapidly [57] and then homogenized in a Vibra Cell sonicator (Sonics and Materials Inc., Danbury, CT, USA). Spectrophotometric catalase activities were run as described [58]. For each assay the lysate of 1.0 × 106 cells was introduced into the cuvette. The kinetic reaction was initiated by the addition of 500 μL of a 30 mM H2O2 stock solution in phosphate buffer pH 7.0 and the loss of absorbance at 240 nm over a 2 min period was monitored. Catalase activities were calculated as a first-order reaction rate constant (k) and expressed as milli k units/106 cells. Cellular H2O2 concentrations were then determined by the kinetic analysis of the rate of decrease in catalase activity [55].

Cell survival by flow cytometry

Cell survival was determined with propidium iodide (PI) and Annexin V- FITC by flow cytometry. A stock solution of PI (1 mg/mL) was prepared in distilled water and stored at 4°C in the dark. Annexin V (0.8 μg/mL final) and PI (1 μg/mL final) were added to 0.5 mL of cell suspension (5 × 105) in 1X Annexin binding buffer and incubated for 5 min in the dark. Cell survival was determined with a Facscan flow cytometer from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA) equipped with an argon laser (488 nm). Data handling was performed by Cell Quest software from BD Biosciences. Because the border/area between Annexin staining and PI staining was not very distinct, we did not determine mode of cell death but rather combined both areas to determine overall killing.

Intracellular vitamin C by HPLC

Intracellular ascorbate concentrations were determined with HPLC following the protocol from Levine et al. [59]. Briefly, cells were incubated with ascorbate and washed twice with PBS. Cells were counted and then 3–4 × 106 cells were extracted with 0.50 mL methanol/H2O (60/40%) containing 250 μM DETAPAC. The mixture was kept on ice for 5 min to precipitate the protein, centrifuged, and the supernatant filtered with a 0.22 μm syringe filter and stored frozen (−80°C) until the day of measurement. HPLC analysis was performed with a PhotoDiodeArray detector from the Thermo Electron Corp (Waltham, MA) using a Luna (2) C-18, 5 μm, 250 × 4.6 mm column from Phenomenex Inc. (Torrance, CA). The mobile phase consisted of: 15% organic phase (36.6 μM tetra-octyl-ammionium bromide in methanol) and 85% aqueous phase (189 μM dodecyl-trimethyl-ammionium chloride, 0.05 M sodium phosphate monobasic and 0.05 M sodium acetate HPLC grade, pH adjustment to 4.8 with ortho-phosphoric acid). Standards of vitamin C were prepared fresh using the same extraction solution as for the samples; for quality control a standard sample was run every 5th injection.

Heme-peroxidase activity

The activity of myeloperoxidase was determined by the ability of the enzyme to oxidize tetramethylbenzidine [60]. The MPO activity is expressed as change absorbance units at 655 nm in three minutes. Briefly, cell homogenate ((0.1 – 0.5) × 106 cells) was placed in 3.05 mL 50 mM sodium acetate assay buffer pH 5.4. The assay was initiated with 200 μL of 5.25 mM H2O2 followed by the addition of 50 μL of 100 mM 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine in dimethylformamide. After a 3-min incubation of samples at 25°C the enzymatic reaction was stopped by addition of 100 μL of a catalase solution (100 U/mL) and then 3.4 mL ice-cold acetic acid (2 mM).

To inhibit myeloperoxidase cells were incubated with VP and ascorbate in medium-2 in the presence of 200 μM 4-ABAH (MPO inhibitor). Cell growth and trypan blue permeability of cells were checked at different times after light treatment.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± S.D. Statistical significance of differences between paired data was determined either by Student’s test (single comparisons) or one-way analysis of ANOVA variance for multiple comparisons. Difference among means were considered to be significant at p < 0.05.

Results and Discussion

Cell lines

Because the reducing nature of ascorbate leads to its function as an antioxidant as well as the initiation of oxidation cascades in some settings, we chose to work with two cell lines to determine if the effect of ascorbate on PDA is similar in somewhat different cellular environments. The two human leukemia cell lines were chosen because they are similar as cancer cells originating from the same myelomonocytic lineage. However, HL-60 cells have structure and properties of myelocytes while U937 originated from monocytic progenitors. Both cell lines were grown in the same medium. Because these two cell lines are closely related, we hypothesized that they would behave similar to ascorbate and PDA treatment.

Cell survival after PDA and ascorbate treatment

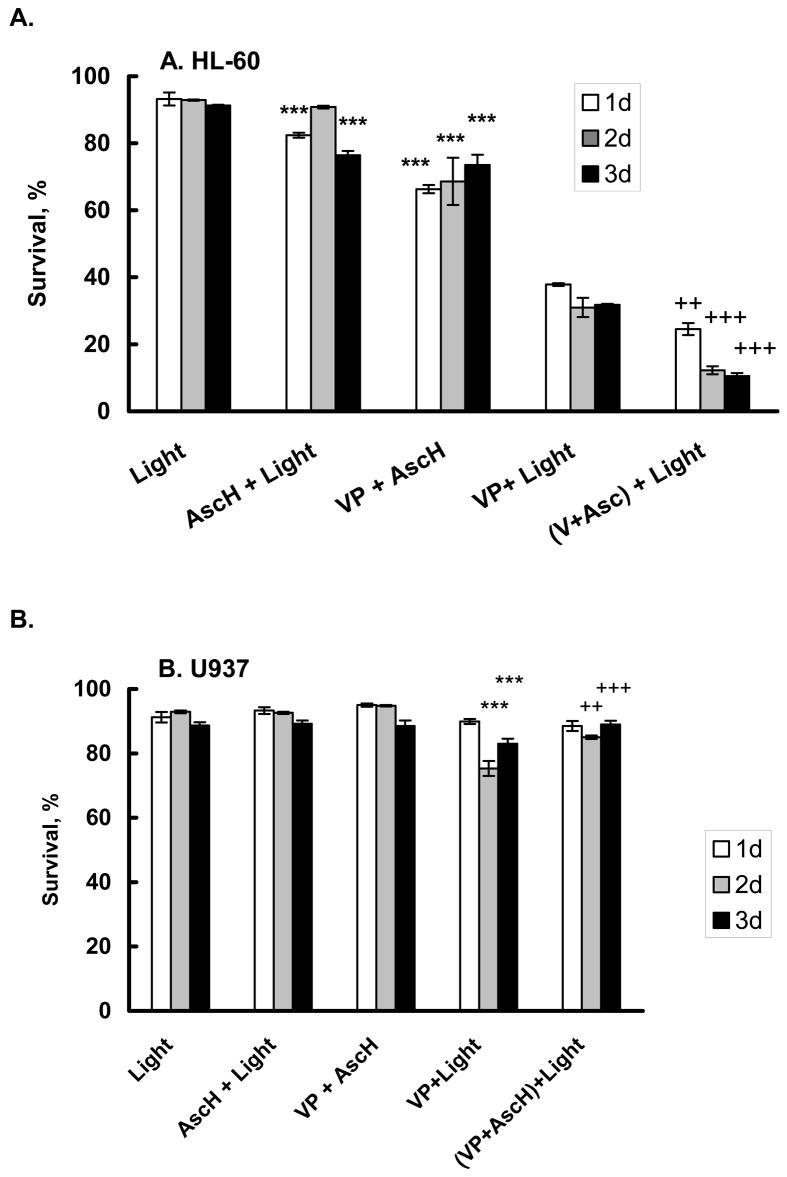

To investigate the effect of ascorbate on PDA we measured cell survival, cell growth, and membrane permeability after PDA and ascorbate treatment. Verteporfin (benzoporphyrin derivative, VP) is a photosensitizer that accumulates mainly in mitochondria [61]. Upon light exposure, VP produces singlet oxygen that can react with unsaturated fatty acids and proteins, leading to radical-formation and membrane-leakage. Some of the 1O2 produced diffuses out of the membrane into the cytosol where it can react with proteins and other electron-rich molecules, such as AscH− and produce diffusible H2O2, Figure 1. We hypothesized that ascorbate will react with some of the 1O2 produced during photodynamic action (PDA), and thereby enhance cellular damage. To test this hypothesis we adjusted PDA conditions so that approximately 40% of the HL-60 cells survived (Figure 2A, VP + light). We added 200 μM ascorbate during incubation with VP to determine the effect of ascorbate on cell survival. Cells were harvested every 24 h for 3 days and cell death determined using FACS analysis with PI and Annexin V-FITC. When HL-60 cells were exposed to ascorbate and light, a slight (10%) decrease in cell survival was observed compared to cells exposed to light alone. Incubation with verteporfin and ascorbate in the dark decreased survival by approximately 20% (P < 0.01). After PDA with verteporfin and light, survival of HL-60 cells decreased by 65% (24 h P < 0.01). Incubation with 200 μM ascorbate enhanced cell killing by an additional 3-fold 3 days after PDA. Thus ascorbate enhances the toxicity of PDA in HL-60 cells.

Figure 2. Ascorbate decreased survival of HL-60 cells (A) after photodynamic treatment but protects U937 cells (B, C).

Cells (1 × 106/mL) were incubated with verteporfin (1.8 nM) in the presence of AscH− (200 μM – (A); and 600 μM – (B,C)) for 1 h in medium containing 2% FBS. Cells were washed and placed into RPMI1640 for light exposure.

A. HL-60 cells were exposed to light, 1.32 J cm−2;

B. U937 cells were exposed to light, 1.32 J cm−2;

C. U937 cells were exposed to light, 1.98 J cm−2.

After light exposure, cells were washed and placed into regular growth medium. Cells were harvested every 24 h for 3 days and cell survival determined using propidium iodide (PI) and Annexin V- FITC. Each point and bar represents the mean and standard error of three independent determinations. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.02; *** P < 0.01 represents a significant difference of survival with respect to light treated cells. ++ P < 0.02; +++ P < 0.01 represents a significant difference of survival with respect to cells after PDA.

Using the same PDA conditions as used for the HL-60 cells, minimal changes in survival of U937 cells were observed, Figure 2B (VP and light). This demonstrates that U937 cells are more resistant to PDA compared to HL-60 cells. Even when the dose of ascorbate was increased to 600 μM no decrease in cell survival was observed. When the light dose was increased from 1.32 to 1.98 J cm−2, PDA alone decreased U937 survival to 20% (P <0.01) two days after light exposure, Figure 2C. In contrast to HL-60 cells, ascorbate showed a protective effect in U937 cells; cell survival was 2-fold higher than that of (VP + light).

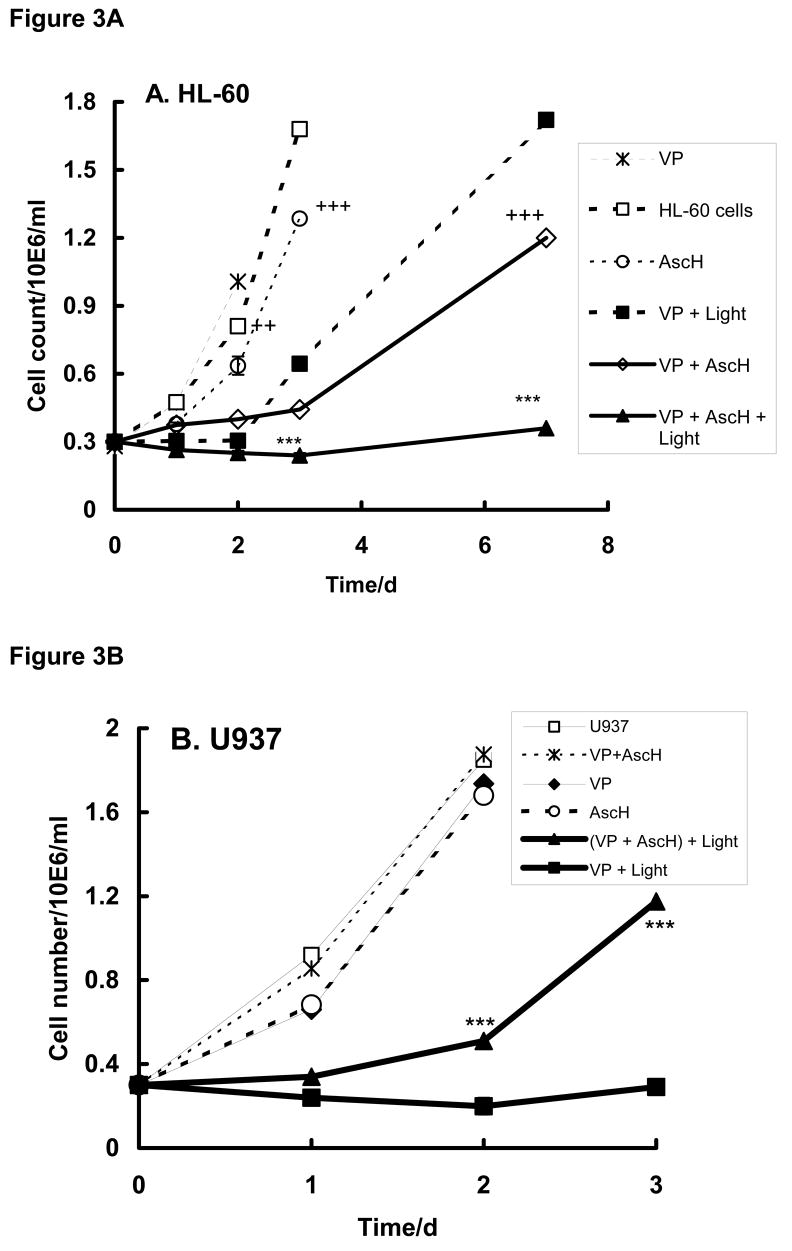

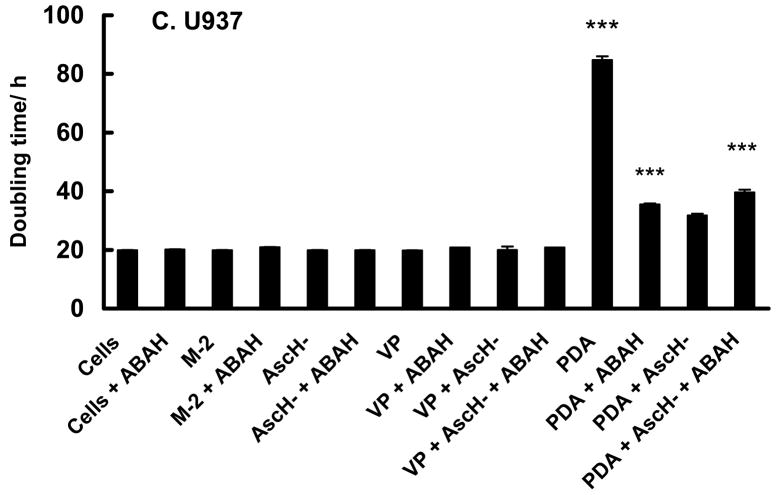

Growth after PDA and ascorbate treatment

In parallel with measurement of the influence of ascorbate and PDA on cell survival, we examined the growth rate of HL-60 and U937 cells after various treatments, Figure 3. Incubation of HL-60 cells with VP or ascorbate (200 μM) in the dark had minimal effect on the growth rate compared to cells with no treatment (P < 0.01). Interestingly, when HL-60 cells were incubated with VP and ascorbate with or without light a significant delay (3 days) in cell growth was observed. This delay was not seen with AscH− or VP alone. Thus, VP and AscH− produce some toxicity in HL-60 cells as seen in both survival and growth.

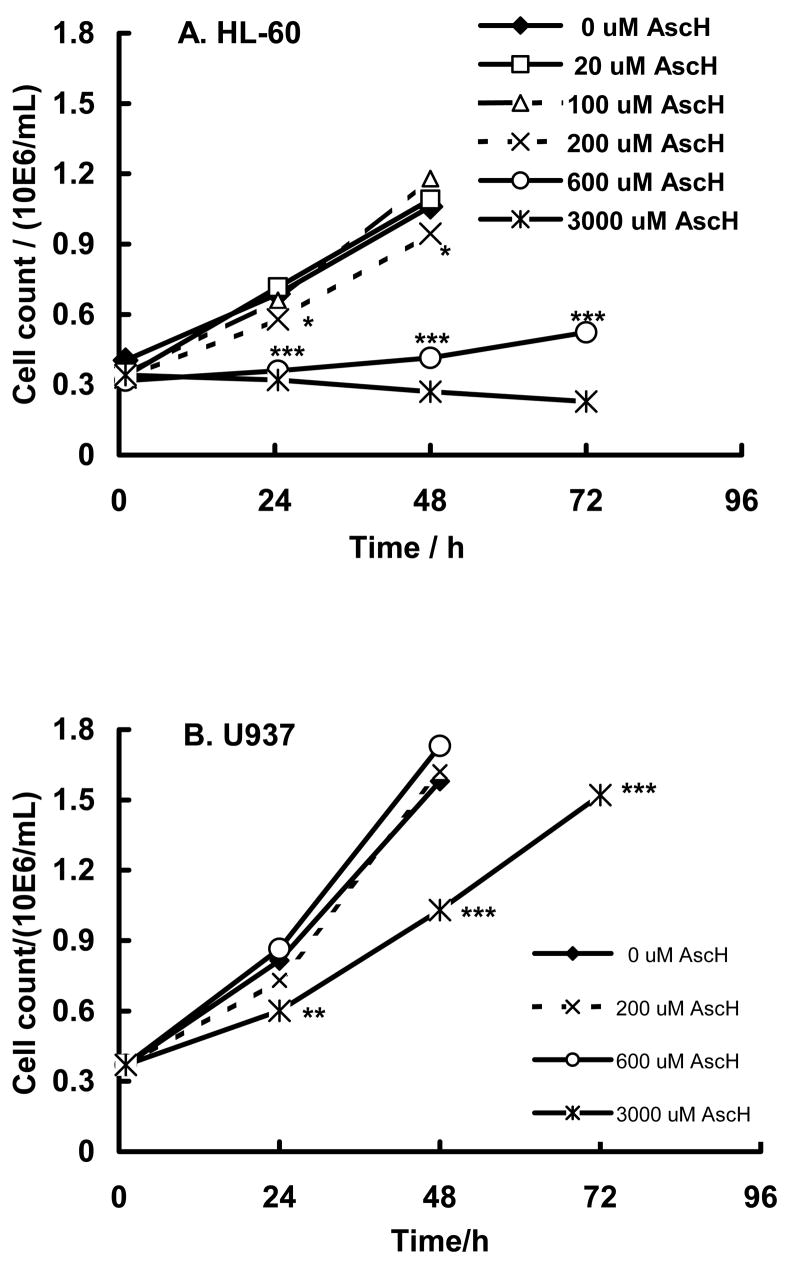

Figure 3. Ascorbate inhibits cell growth after PDA treatment.

Cells (1 × 106/mL) were incubated with verteporfin (1.8 nM) in the presence of AscH− (200 μM – (A); and 600 μM – (B) for 1 h in the medium-2. Cells were washed and placed into RPMI 1640 for light exposure.

A. HL-60 cells were exposed to light (1.32 J cm−2);

B. U937 cells were exposed to light (1.98 J cm−2).

Cells were then transferred into medium-10 and grown at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were counted every 24 h. Each point and bar represents the mean and standard error of three independent determinations. *** P < 0.01 represents a difference between data of (VP + Light) and (VP + AscH− + Light) groups. ++ P < 0.02; +++ P < 0.01 - represent a significant difference of cell growth rate with respect to cells in medium-2.

Exposure of HL-60 cells treated with VP plus light delayed growth by approximately 2 days and the growth rate was slower than in cells without treatment (td = 48.0 vs 28.4 h*, Table 1A and Figure 3A). When these cells were co-incubated with 200 μM ascorbate (AscH− + VP + light) the doubling time increased compared to VP plus light (td = 155 vs 48 h). These results are in agreement with the survival assays of Figure 2. Thus, for HL-60 cells, ascorbate in the presence of VP slows cell growth both in the dark and with light.

Table 1.

| Table 1-A. Doubling time (td) of proliferating HL-60 cells after combined ascorbate treatment with VP-light | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-A | Medium-2 | VP | AscH− + Light | VP + Light | VP + AscH− | VP + AscH− + Light |

| td/h | 28.4 ± 0.2a | 30.2 ± 0.1 | 23.4 ± 1.0 | 48.0 ± 1.8 | 66.7 ± 1.2 | 154.8 ± 24.9 |

| t test | P < 0.01 vs Medium-2 | P < 0.01 vs Medium-2 | P < 0.01 vs VP | P < 0.01 vs VP | P < 0.01 vs VP + AscH− | |

| Table 1-B Doubling time (td) of proliferating U937 after combined ascorbate treatment with VP-light | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium-2 | VP | AscH− + Light | VP + Light | VP + AscH− | VP + AscH− + Light | |

| td/h | 19.1 ± 1.1a | 19.0 ± 0.4 | 19.2 ± 0.6 | 87.1 ± 5.1 | 21.2 ± 0.2 | 39.9 ± 3.3 |

| t test | P < 0.01 vs VP | P < 0.02 vs VP | P < 0.01 vs VP + AscH− | |||

Each result represents the mean and standard error of three independent determinations.

U937 cells were found to be more resistant to PDA with VP, thus the light dose was increased (from 1.32 to 1.98 J cm−2) as well as the amount of ascorbate (from 200 to 600 μM). In the dark, incubation with VP, ascorbate, or both resulted in growth curves that were the same as U937 cells with no treatment. Exposure of U937 cells to VP + light suppressed growth by a factor of 4.6 compared to cells incubated with VP in the dark, Table 1B and Figure 3B. In contrast to HL-60 cells inclusion of ascorbate during PDA resulted in protection of U937 cells (td = 19.2 h in presence of ascorbate; td = 87.1 h for cells after PDA only, Table 1B). Thus, ascorbate protects U937 cells against PDA; this is similar to the effect seen in the cell survival experiment with U937 cells, Figure 2B.

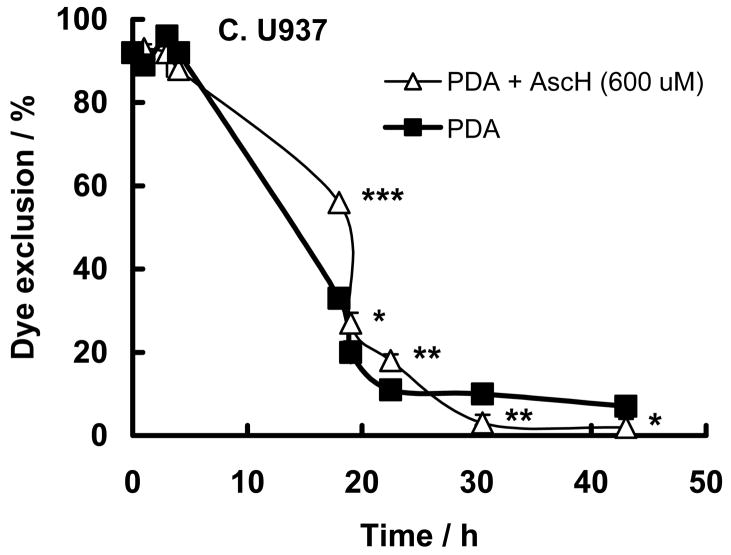

Ascorbate enhances PDA in HL-60 cells, but protects U937 cells as seen by membrane permeability

Membrane integrity can be a marker of cell damage. Oxidative damage to cell membranes can breach this integrity. As a measure of the oxidative damage induced by PDA changes in membrane integrity were determined by trypan blue dye exclusion. To test the effect of PDA and ascorbate on the plasma membrane we subjected cells to similar conditions as in Figure 2. In both cell lines the permeability of the plasma membrane was enhanced 20 h after PDA, Figure 4. In HL-60 cells 600 μM ascorbate enhanced PDA-induced membrane permeability (P <0.01), Figure 4A. Incubation with 600 μM ascorbate alone or together with the photosensitizer in the dark did not enhance permeability of the plasma membrane (data not shown). This supports the viability results that the reducing nature of ascorbate results in the initiation of oxidation processes in HL-60 cells.

Figure 4. Ascorbate changes membrane permeability after PDA.

HL-60 or U937cells (1 × 106/mL) were incubated with verteporfin (1.8 nM) (filled square) in the presence of AscH− (100 μM – open triangle; and 600 μM – open circle) for 1 h in medium containing 2% FBS. Cells were washed and placed into RPMI 1640 for light exposure.

A. HL-60 cells were exposed to light (1.32 J cm−2);

B. U937 cells were exposed to light (1.32 J cm−2);

C. U937 cells were exposed to light (1.98 J cm−2).

After light-exposure cells were washed and placed into regular growth medium. Membrane permeability was tested at different times (h) after light exposure with trypan blue exclusion. Each point and bar represents the mean and standard error of three independent determinations; some error bars are within the symbol. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.02; *** P < 0.01, represent comparisons between experiments with and without PDA.

In contrast to HL-60 cells ascorbate seems to protect against PDA in U937 cells, Figure 4B; the higher the ascorbate concentration the greater the protection against membrane permeability. However, when the light dose was increased the protective effect of ascorbate (600 μM) was lost, Figure 4C, probably because the flux of oxidants overwhelms the antioxidant aspects of ascorbate.

These results suggest that in general ascorbate acts as a “pro-oxidant” in HL-60 cells and an antioxidant in U937 during PDA. To probe for the reason why ascorbate behaves so differently in these two cells lines we investigated the following factors: uptake of VP, AscH− uptake and toxicity, redox environment via GSH and H2O2, and myeloperoxidase activity.

Uptake of VP

A possible reason for the differences seen in the sensitivity of the two cell lines to the combined treatment of VP and ascorbate could be a variation in cellular uptake of VP. We examined the uptake of VP by these two leukemia cell lines in the presence or absence of ascorbate. The cells were incubated with VP for 1 h in medium-2 as described in Material and Methods. We found no difference in the fluorescent intensity of BPD-MA in cell extracts (50 × 106 cells) from HL-60 and U937 cells after incubation with VP (n = 4). The presence of ascorbate during incubation with VP increased the fluorescence of BPD-MA by 10–30% in both HL-60 and U937 cell extracts. Thus, possible differences in uptake of VP are not factors between the two cell lines and their response to PDA.

Ascorbate slows cell growth in vitro

Ascorbate has been shown that prolonged exposure of cells to ascorbate in culture medium can be cytotoxic due the production of H2O2 [63]; the rate of H2O2 production from oxidation of ascorbate is dependent on the medium [64]. To determine how ascorbate will influence the growth rate of HL-60 and U937 cells we incubated these cell lines with different concentrations of ascorbate (0 – 3000 μM). To allow cells to accumulate ascorbate and avoid prolonged exposure, cells were incubated for only 1 h with ascorbate in medium-2. Ascorbate-containing medium was then removed and replaced with medium-10 and cells were incubated at 37°C. Cells were counted every 24 h. Ascorbate inhibited the growth of HL-60 and U937 cells in a concentration-dependent manner. HL-60 cells were more sensitive to ascorbate compared to U937 cells, Figure 5. Media concentrations of ascorbate > 200 μM resulted in significant delay in cell growth in HL-60 cells (P < 0.01), while U937 cells tolerated ≥ 600 μM AscH− without a significant change in cell growth. Thus, HL-60 cells are more sensitive to the oxidations initiated by AscH− than U937. To minimize direct influence of ascorbate no more than 200 μM AscH− was used for most of the PDA-experiments with HL-60 cells.

Figure 5. Ascorbate slows cell growth.

HL-60 cells (A) and U937 cells (B) were incubated with ascorbate (0 – 3000 μM) in medium-2 for 1 h, then washed and placed in medium-10 at a density of 0.35 – 0.40 × 106 cells/mL. Cells were counted every 24 h. Each point represents the mean and standard error of three independent determinations. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.02 ***, P < 0.01 represent a significant difference of cell count after incubation of HL-60 cells in the presence of 200; 600; or 3000 μM compared to 0 μM AscH−; for U937 - in the presence of 3000 μM with respect to cells incubated in medium-2.

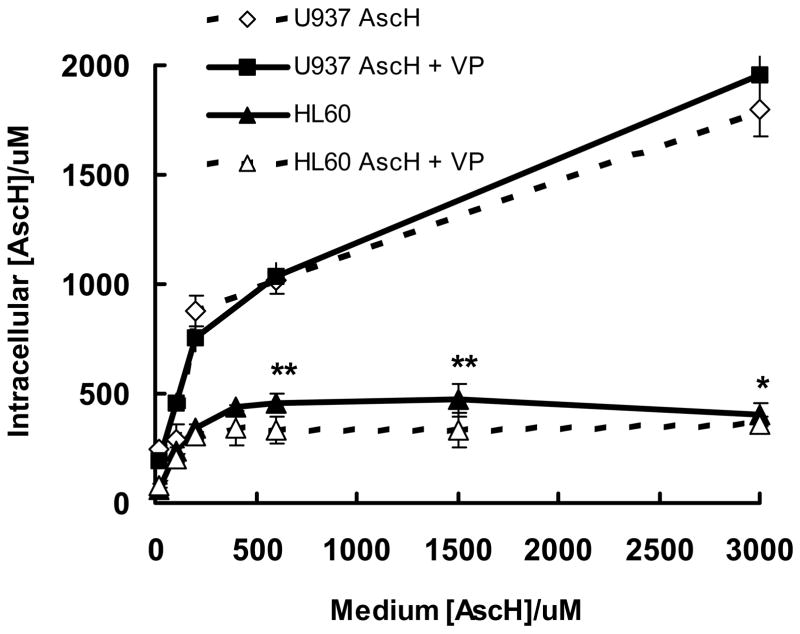

Cellular Uptake of AscH− is higher in U937 cells compared to HL-60 cells

To determine if ascorbate-uptake varies between HL-60 and U937 cells, intracellular concentrations of AscH− were measured using HPLC/EC. To determine how the intracellular levels of ascorbate varied with the concentration in the medium, ascorbate (0–3000 μM) was added to cells in medium-2 for 1 h and then intracellular ascorbate was measured. Ascorbate uptake by HL-60 cells increased as ascorbate was varied from 20 to 400 μM; relative uptake plateaued when media concentrations were greater than ≈400 μM, Figure 6. In contrast to HL-60 cells, U937 cells accumulated higher levels of intracellular AscH− (2- to 4-fold). AscH− uptake in U937 cells also appears to have two different phases. Like HL-60 cells, when AscH− in the medium ranges from 20 to 400 μM, intracellular changes in the uptake of ascorbate were steep. At concentrations higher than ≈400 μM, relative uptake decreased. These results are consistent with the known active accumulation of ascorbate by cells to concentrations many times more than in the extracellular space [18, 65, 66]. The ascorbate levels in human neutrophils and monocytes in vivo [16] are similar to the levels of ascorbate taken up by HL-60 and U937 cells, using our approach. Although the molar concentration of ascorbate is higher in the cells compared to the media, at 1 × 106 cell mL−1 there will be ≈50 – 200 times more moles of ascorbate in the media than in the cells. Thus, if there is significant oxidation of the ascorbate in the media, the H2O2 produced outside the cells could dominate the level of H2O2 in the cells. This would be in accordance with data demonstrating that the growth inhibitory effect of ascorbate is dependent on the concentration of ascorbate in the culture medium and not its intracellular concentration (compare Figures 5 and 6) [63, 67].

Figure 6. Uptake of ascorbate is higher in U937 cells compared to HL-60 cells.

HL-60 and U937cells (1 × 106/mL) were incubated with AscH− (0–3000 μM) with or without verteporfin (1.8 nM) for 1 h in medium-2. Cells were counted and intracellular [AscH−] determined by HPLC. Each point and bar represents the mean and standard error of three independent determinations. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.02, represent a significant difference with respect to HL-60 cells after treatment with AscH− + VP.

The presence of Verteporfin had no effect on intracellular ascorbate accumulation in U937 cells, but there was somewhat less ascorbate uptake (<15%) in HL-60 cells at higher levels of ascorbate, Figure 6. From Figure 6 we can infer that in the experiments of Figures 2–4 the intracellular concentration of ascorbate in HL-60 cells was three times lower (0.3 mM) than that of the U937 cells (1.0 mM). Therefore the effects of ascorbate on HL-60 cells during PDA must be due to factors other than the levels of intracellular ascorbate.

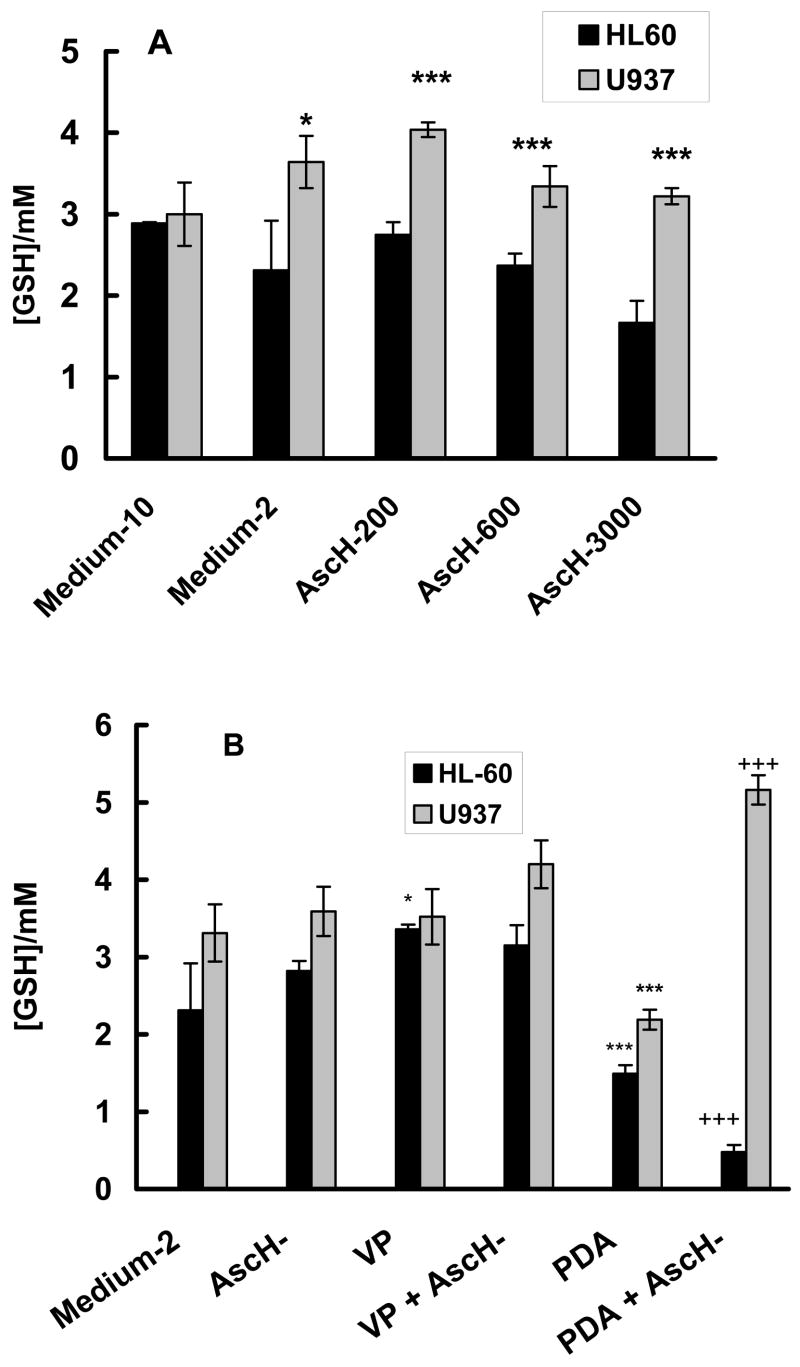

Intracellular GSH, AscH− and PDA

Ascorbate uptake in leukemia cells, such as HL-60 and U937, occurs mainly through the oxidized form DHA [65, 68, 69]. DHA is transported into cells by sodium-independent glucose transporters. Once inside the cell, DHA is reduced to AscH−. Reduction of DHA to AscH− can be both, GSH-dependent or independent [65, 70]. Glutathione is considered to be the principal redox buffer in the cell [71]. Depletion of GSH has been shown to increase the vulnerability of leukemia cells to exposure to ROS [72, 73]. To determine if ascorbate influences the levels of GSH, ascorbate (200 – 3000 μM) was added to the culture medium. The level of GSHT in HL-60 cells incubated in medium-2 was somewhat lower compared to incubation in medium-10, Figure 7A. The level in U937 cells in medium-2 was similar to that in medium-10. The GSHT level in the two cells lines were the same when incubated in medium-10. In addition, the intracellular ascorbate levels in both cell lines were similar in medium-10 (data not shown). Incubation of the two cell lines with 200 or 600 μM ascorbate in medium-2 resulted in minor changes in the intracellular concentration of GSHT. The intracellular GSHT in HL-60 cells was lower than that found in U937 cells. GSHT had a tendency to decrease with increasing ascorbate. However compared to the control (medium-2), ascorbate does not change the level of GSHT. The lower levels of GSHT and ascorbate in HL-60 cells compared to U937 cells indicates that the redox environment [71] of HL-60 is more oxidized than in U937 cells suggesting that HL-60 cells may have a lower capacity to buffer an increased flux of ROS and thus they would have a higher sensitivity to ROS.

Figure 7. Influence of ascorbate on intracellular [GSH].

A. HL-60 (open bars) and U937 (filled bars) cells (1 × 106/mL) were incubated with AscH− (0 – 3000 μM) for 1 h in medium-2. Cells were washed, counted, lysed, and intracellular [GSH] determined by a GSH recycling assay. Control in medium-10 represents the GSH levels for the cells in their normal growth medium. Each bar represents the mean and standard error of at least three independent determinations. * P < 0.05; *** P < 0.01 represent a significant difference in the level of GSH in U937 cells compared to HL-60 cells incubated in medium-2.

B. Influence of ascorbate and PDA combined treatment on intracellular [GSH]. HL-60 (open bars) and U937 (filled bars) cells (1 × 106/mL) were incubated with verteporfin (1.8 nM) in the presence of AscH− (200 μM – HL-60; and 600 μM – U937) for 1 h in medium-2. Cells were washed and placed into RPMI 1640 for light exposure. HL-60 cells were exposed to a light-dose of 1.32 J cm−2 while U937 cells were exposed a light-dose of 1.98 J cm−2. Cells were washed, counted, lysed, and intracellular [GSH] determined by a GSH recycling assay. Control represents the GSH levels for cells incubated in medium-2 for 1 h. Each bar represents the mean and standard error of at least three independent determinations. * P < 0.05; *** P < 0.01 represent a significant difference in GSH levels with respect to cells incubated in medium-2. +++ P < 0.01 represents a significant difference in GSH with respect to cells after PDA.

Changes in GSHT levels could be a marker of toxicity induced by PDA and ascorbate. Thus, we checked for changes in GSHT after treatment with PDA/ascorbate, Figure 7B. U937 cells have higher levels of GSHT than HL-60 cells in all experimental groups, including after PDA. The GSHT level in U937 cells did not change after treatment with ascorbate, VP, or VP plus ascorbate. The GSHT level of HL-60 cells in all control groups was also the same, except for the group with VP. PDA induced significant loss of GSHT (P < 0.001) in both cell lines. However, ascorbate in combination with PDA resulted in further loss of GSHT in HL-60 cells (P < 0.001) but increased GSHT in U937 cells (P < 0.001). These changes in GSHT induced by PDA and ascorbate correlated with the cell survival of Figure 2. Thus the sensitivity of these cells to PDA may be related in part to their levels of GSHT.

Intracellular H2O2 is higher in HL-60 cells compared to U937 cells

Another indicator for the intracellular redox environment is the steady-state level H2O2. We examined the ambient intracellular levels of H2O2 via inhibition of catalase by aminotriazole [55, 56]. We found that untreated U937 cells have lower steady-state levels of intracellular H2O2 compared to HL-60 cells, 14.2 ± 0.7 pM vs 39.2 ± 0.6 pM respectively (Table 2). U937 cells have over twice the catalase activity of HL-60 cells. This can explain the lower intracellular hydrogen peroxide level in U937 cells and also our findings that U937 cells are more resistant to PDA-ascorbate treatment than HL-60 cells. Catalase can remove hydrogen peroxide formed by ascorbate and singlet oxygen, thereby preventing cellular damage.

Table 2.

Catalase activity and H2O2 level of leukemia cells

| Total catalase activity, k mU/106 cells | Catalase activity in presence of AT, k mU/106 cells | [H2O2]ss/pMa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HL-60 | 0.80 ± 0.15b | 0.24 ± 0.004 | 39.2 ± 0.6 |

| U937 | 1.74 ± 0.35 | 0.93 ± 0.24 | 14.2 ± 0.7 |

| t testc | P < 0.01 | P < 0.01 | P < 0.01 |

An estimate of the intracellular steady-state level of hydrogen peroxide.

Each result represents the mean and standard error of three independent determinations.

Each test is a comparison between cell lines.

The higher level of hydrogen peroxide is also consistent with the intracellular redox environment of HL-60 cells being more oxidizing than in U937 cells. This is also in line with the relative GSH levels in these two cell lines, Figure 7, as well as the lower levels of ascorbate, Figure 6. Unfortunately, the assay for intracellular hydrogen peroxide cannot be used in experiments with added ascorbate because ascorbate would interfere with the kinetics of the inactivation of catalase by AT. These observations are consistent with the formation of H2O2 by AscH− and that cells having a lower peroxide-removing capacity are sensitized to PDA.

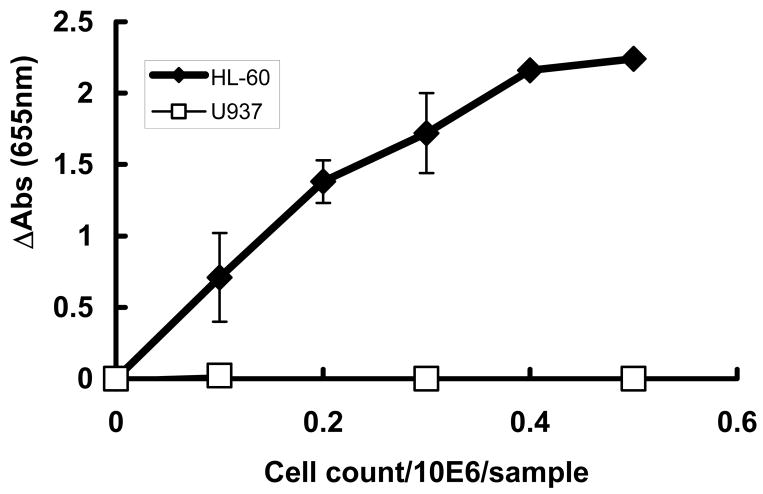

The toxicity of ascorbate is enhanced by MPO

Heme peroxidases, such as MPO, are activated by H2O2 to make more reactive oxidants, such as HOCl. To understand a possible role for MPO in the difference in the sensitivity of HL-60 and U937 cells to PDA the activity of MPO was determined, Figure 8. The activity of MPO in U937 cells was below the limit of detection, while HL-60 cells had high activity levels. This peroxidase activity in HL-60 cells was effectively inhibited by 200μM of ABAH, an inhibitor of MPO, (84 ± 2% with a 30 min incubation, n = 3) supporting the specificity of the assay. To examine if active MPO in HL-60 cells could be one of the factors responsible for the ascorbate toxicity we determined the effect of ascorbate on the growth rate and survival of HL-60 and U937 cells in the presence of ABAH.

Figure 8. HL-60 cells have MPO activity while U937 cells are void of MPO-activity.

For the MPO assay cell homogenates from 0.1 – 0.5 × 106 HL-60 (open squares) or U937 (filled squares) cells were placed in 3.05 mL of 50 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.4. The MPO activity was expressed in change in absorbance at 655 nm. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 6).

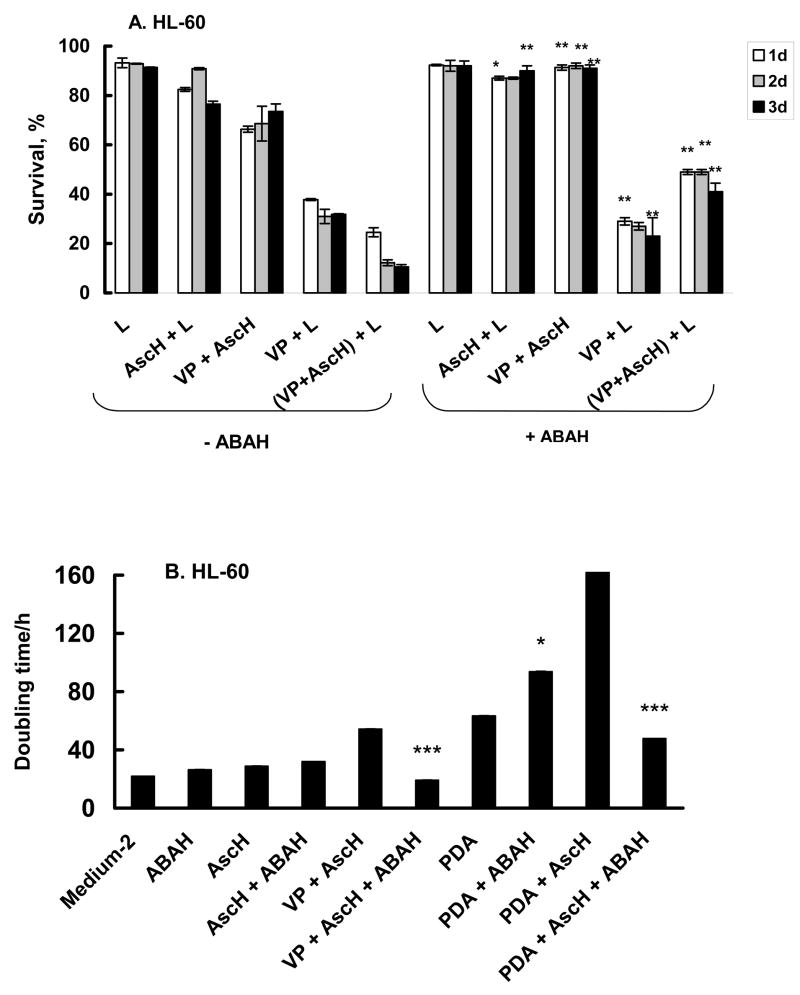

Cells were treated with ascorbate and PDA with or without 200 μM ABAH. ABAH maintained the survival of HL-60 cells treated with AscH− or AscH− and VP (Figure 9A). Interestingly, ABAH did not affect the survival of the group treated with VP + light, where singlet oxygen would be the major initiating oxidant. However, when AscH− was present during treatment with VP + light, ABAH provided protection. This protective effect is also reflected in cell growth (Figure 9B). ABAH increased the rate of growth (shorter doubling time) of HL-60 cells treated with PDA + AscH−, resulting in a doubling time similar to the doubling time of control cells (VP + AscH−). These data suggest that the H2O2 produced by AscH− and 1O2 is a substrate for MPO in HL-60 cells enhancing the toxicity of PDA. As expected, ABAH did not influence the antioxidant effect of ascorbate on U937 with the same experimental conditions (Figure 9C). These data clearly show that PDA in the presence of ascorbate increases the production of H2O2. This H2O2 can induce additional toxicity by initiating the two-electron oxidation of myeloperoxidase forming the highly oxidizing compound-I [74]. MPO compound-I will in turn initiate detrimental oxidations.

Figure 9. Myeloperoxidase inhibitor (ABAH) protected HL-60 cells against ascorbate but not PDA toxicity.

Cells (1 × 106/mL) were incubated with verteporfin (1.8 nM) and AscH− (200 μM) in the presence or absence of ABAH (200 μM) for 1 h in medium-2. Cells were washed and placed into RPMI 1640 for light exposure. HL-60 cells were then exposed to light, 1.32 J cm−2. After light exposure, cells were washed and placed into regular growth medium. Cells were harvested every 24 h for 3 days and cell survival determined using propidium iodide (PI) and Annexin V- FITC. Each point and bar represents the mean and standard deviation of three independent determinations. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.02; *** P < 0.01, represent comparison between groups of data (−ABAH) vs. (+ABAH).

Summary

This work clearly demonstrates that ascorbate can have quite different effects on the phototoxicity of two closely related human cell lines. U937 and HL-60 cells are derived from a promyelocytic progenitor; HL-60 cells have structure and properties of myelocytes while U937 have properties of monocytes. We hypothesized that ascorbate could increase the flux of hydrogen peroxide during photodynamic action. Thus, the peroxide-removing systems of the two cell lines would be central to the potential toxicity of this H2O2. We have found that U937 cells have a somewhat higher level of GSH and twice the catalase activity of HL-60 cells, consistent with the observations of Cai et al. [75]. They also found that the GPx-1 and total SOD activity of these two cell lines to be similar. This difference in catalase activity could render HL-60 cells more vulnerable to an increased flux of H2O2. However, a key difference in these two cell lines is that HL-60 cells have a high level of MPO, while in U937 cells this enzyme activity is below the limit of detection. Upon exposure to H2O2, this MPO is activated producing oxidants that are toxic to HL-60 cells [76]. The data of Figure 9 clearly show that ascorbate enhances the production of H2O2 associated with the photodynamic action of VP + light and that this H2O2 can enhance the toxicity of PDA. Thus ascorbate could be an adjuvant for photodynamic therapy, but the capacity of the tumor to remove peroxide would be a central consideration in its use.

Acknowledgments

We thank George Rasmussen for the excellent technical support in Flow Cytometry assays and Brett A. Wagner for advise on the intracellular H2O2 and MPO activity measurements. This study was supported by NIH Grant CA-66081.

Abbreviations

- ABAH

4-aminobenzoic acid hydrazide

- AscH−

ascorbic acid monoanion

- AT

3-amino-1H-1,2,4-triazole

- BPD-MA

benzoporphyrin derivate monoacid ring A, the active component of VP

- DETAPAC

diethylenediaminepentaacetic acid

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- DTNB

5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid)

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GPx

glutathione peroxidase

- GR

glutathione disulfide reductase

- GSH

glutathione

- GSHT

total glutathione

- GSSG

glutathione disulfide

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- NADPH

reduced nicotine amid dinucleotide phosphate

- PDA

photodynamic action, i.e. VP + light

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- td

doubling time

- VP

verteporfin

Footnotes

Here td is not the traditional doubling time for cell growth [62] because at time zero the cells were a mixture of dying and surviving cells. Thus, td is a value for the growth rate of this mixture.

References

- 1.Dougherty TJ, Gomer CJ, Henderson BW, Henderson BW, Jori G, Kessel D, Korbelic M, Moan J, Peng Q. Photodynamic Therapy: Review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:889–902. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.12.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henderson BW, Dougherty TJ. How does photodynamic therapy work? Photochem Photobiol. 1992;55:145–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1992.tb04222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jamieson C, Hornby A, Richter A, Mitchell D, Levy J. Relative sensitivity of leukemic (CML) and normal progenitor cells to treatment with the photosensitizer benzoporphyrin derivative and light. J Hematother. 1993;2:383–386. doi: 10.1089/scd.1.1993.2.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bissonnette R, McLean DI, Reid G, Kelsall J, Lui H. Photodynamic therapy of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with BPD verteporfin. Seventh Biennial Congress of the International Photodynamic Association; Nantes France. 1998. p. Abs RC87. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calzavara-Pinton PG, Szeimies R-M, Ortel B, Zane C. Photodynamic therapy with systemic administration of photosensitizers in dermatology. J Photochem Photobiol. 1996;B 35:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(96)07377-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnold J, Blemenkranz M, Bressler NM, Bressler SB, Deslandes J-Y, Donati G, Fish Gragoudas ES, Harvey P, Huber G, Kaiser PK, Kaus L, Koenig F, Koester J, Lewis H, Lobes L, Margherio RR, Miller JW, Mones J, Murphy S, Reaves A, Rosenfeld PJ, Schachat AP, Strong HA, Stur M, Williams GA. Photodynamic therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration with verteporfin: One year results of 2 randomized clinical trials-TAP report. Treatment of age-related macular degeneration with photodynamic therapy (TAP) study group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:1329–1345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richter AM, Waterfield E, Jain AK, Allison B, Sternberg ED, Dolphin D, Levy JG. Photosensitizing potency of structural analogues of benzoporphyrin derivative (BPD) in a mouse tumour model. BrJ Cancer. 1991;63:87–93. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allison BA, Waterfield E, Richter AM, Levy JG. The effects of plasma lipoproteins on in vitro tumor cell killing and in vivo tumor photosensitization with benzoporphyrin derivative. Photochem Photobiol. 1991;54:707–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1991.tb02079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cincotta L, Szeto D, Lampros E, Hasan T, Cincotta AH. Benzophenothiazine and benzoporphyrin derivative combination phototherapy effectively eradicates large murine sarcomas. Photochem Photobiol. 1996;63:229–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1996.tb03019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carthy CM, Granville DJ, Jiang H, Levy JG, Rudin CM, Tompson CB, Hunt DW. Early release of mitochondrial cytochrome c and expression of mitochondrial epitope 7A6 with a porphyrin derived photosensitizer: Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL overexpression do not prevent early mitochondrial events but still depress caspase activity. Lab Invest. 1999;79:953–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Runnels JM, Chen N, Kato D, Hassan T. BPD-MA-mediated photosensitization in vitro and in vivo: Cellular adhesion and β1 integrin expression in ovarian cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:946–953. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Granville DJ, Hunt DW. Porphyrin-mediated photosensitization – Taking the apoptosis fast lane. Current Opinion in Drug Discovery and Development. 2000;3:232–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granville DJ, Jiang H, An MT, Levy JG, McManus BM, Hunt DW. Bcl-2 overexpression blocks caspase activation and downstream apoptotic events instigated by photodynamic therapy. BrJ Cancer. 1998;79:95–100. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Granville DJ, Levy JG, Hunt DW. Photodynamic treatment with benzoporphyrin derivative monoacid ring A produces protein tyrosine phosphorylation events and DNA fragmentation in murine P815 cells. Photochem Photobiol. 1998;67:358–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carthy CM, Granville DJ, Jiang H, Levy JG, Rudin CM, Thompson CB, McManus BM, Hunt DW. Early release of mitochondrial cytochrome c and expression of mitochondrial epitope 7A6 with a porphyrin-derived photosensitizer: Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL overexpression do not prevent early mitochondrial events but still depress caspase activity. Lab Invest. 1999;79:953–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Omaye ST, Schaus EE, Kutnink MA, Hawkes WC. Measurement of vitamin C in blood components by high-performance liquid chromatography. Implication in assessing vitamin C status. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1987;498:389–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb23776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levine M, Conry-Cantilena C, Wang YH, Welch RW, Washko PW, Dhariwall KR, Park JB, Lazarev A, GraumLich J, King J, Cantilena LR. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: Evidence for a recommended dietary allowance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3704–3709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welch RW, Wang Y, Crossman AJ, Park JB, Kirk KL, Levine M. Accumulation of vitamin C (ascorbate) and its oxidized metabolite dehydroascorbic acid occurs by separate mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12584–12592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baader SL, Bruchelt G, Trautner MC, Boschert H, Niethhammer D. Uptake and cytotoxicity of ascorbic acid and dehydroascorbic acid in neuroblastoma (SK-N-SH) and neuroectodermal (SK-N-LO) cells. Anticancer Res. 1994;14:221–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spielholz C, Golde DW, Houghton AN, Nualart F, Vera JC. Increased facilitated transport of dehydroascorbic acid without changes in sodium-dependent ascorbate transport in human melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2529–2537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langemann H, Torhorst J, Kabiersch A, Krenger W, Honegger CG. Quantitative determination of water- and lipid – soluble antioxidants in neoplastic and non-neoplastic human breast tissue. Int J Cancer. 1989;43:1169–1173. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910430634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buettner GR, Jurkiewicz BA. Catalytic metals, ascorbate, and free radicals: combinations to avoid. Rad Research. 1996;145:532–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buettner GR, Need MJ. Hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl free radical production by hematoporphyrin derivative, ascorbate and light. Cancer Lett. 1985;25:297–304. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(15)30009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rougee M, Bensasson RV. Determination of the decay-rate constant of singlet oxygen (1Δg) in the presence of biomolecules. CR Seances Acad Sci, Ser II. 1986;302:1223–1226. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bisby RH, Morgan CG, Hamblett I, Gormahn AA. Quenching of singlet oxygen by trolox C, ascorbate and amino acids: Effects of pH and temperature. J Chem Phys A. 1999;103:7454–7459. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanofsky JR, Sima PD. Singlet oxygen chemiluminescence at gas-liquid interfaces: theoretical analysis with a one-dimensional model of singlet oxygen quenching and diffusion. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;312:244–253. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee PC, Rodgers MAJ. Singlet molecular oxygen in micellar systems. 1. Distribution equilibriums between hydrophobic and hydrophilic compartments. J Phys Chem. 1983;87:4894–4898. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodgers MAJ, Lee PC. Singlet molecular oxygen in micellar systems. 2. Quenching behavior in AOT reverse micelles. J Phys Chem. 1984;88:3480–3484. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baker A, Kanofsky JR. Quenching of singlet oxygen by biomolecules from L1210 leukemia cells. Photochem Photobiol. 1992;55:523–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1992.tb04273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker A, Kanofsky JR. Time-resolved studies of singlet-oxygen emission from L1210 leukemia cells labeled with 5-(N-hexadecanoyl)amino eosin. A comparison with a one-dimensional model of singlet-oxygen diffusion and quenching. Photochem Photobiol. 1993;57:720–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1993.tb02944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fu YX, Sima PD, Kanofsky JR. Singlet-oxygen generation from liposomes: A comparison of 6 beta-cholesterol hydroperoxide formation with predictions from a one-dimensional model of singlet-oxygen diffusion and quenching. Photochem Photobiol. 1996;63:468–476. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu YX, Kanofsky JR. Singlet oxygen generation from liposomes – A comparison of the time-resolved 1270 nm emission with singlet-oxygen kinetics calculated from a one-dimensional model of singlet oxygen diffusion and quenching. Photochem Photobiol. 1995;62:692–702. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanofsky JR. Quenching of singlet oxygen by human red cell ghosts. Photochem Photobiol. 1991;53:93–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1991.tb08472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skovsen E, Snyder JW, Lambert JDC, Ogilby PR. Lifetime and diffusion of singlet oxygen in a cell. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:8570–8573. doi: 10.1021/jp051163i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snyder JW, Skovsen E, Lambert JDC, Ogilby PR. Subcellular, time-resolved studies of singlet oxygen in single cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:14558–14559. doi: 10.1021/ja055342p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu YX, Sima PD, Kanofsky JR. Singlet-oxygen generation from liposomes: A comparison of 6 beta-cholesterol hydroperoxide formation with predictions from a one-dimensional model of singlet-oxygen diffusion and quenching. Photochem Photobiol. 1996;63:468–476. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fu YX, Kanofsky JR. Singlet oxygen generation from liposomes – A comparison of the time-resolved 1270 nm emission with singlet-oxygen kinetics calculated from a one-dimensional model of singlet oxygen diffusion and quenching. Photochem Photobiol. 1995;62:692–702. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Girotti AW. Mechanisms of lipid peroxidation. J Free Radic Biol Med. 1985;1:87–95. doi: 10.1016/0748-5514(85)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelley EE, Domann FE, Buettner GR, Oberley LW, Burns CP. Increased efficacy of in vitro Photofrin photosensitization of human oral squamous cell carcinoma by the prooxidants iron and ascorbate. J Photochem Photobiol. 1997;40:273–277. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(97)00068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelley EE, Buettner GR, Burns CP. Production of lipid-derived free radicals in L1210 murine leukemia cells is an early event in the photodynamic action of Photofrin. Photochem Photobiol. 1997;65:576–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1997.tb08608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Everse J, Everse KE, Grisham MB, editors. Peroxidases in Chemistry and Biology. CRC Press, Vol I; Boca Raton, FL: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ito A, Ito T. Enhancing effect of ascorbate on toluidine blue photosensitisation of yeast cells. Photochem Photobiol. 1982;35:501–505. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh H, Vadasz JA. Singlet oxygen quenchers and the photodynamic inactivation of E. Coli ribosomes by methylene blue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1977;76:391–397. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(77)90737-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosental I, Ben-Hur E. Ascorbate-assisted, phtalocyanine-sensitized photohaemolysis of human erythrocytes. Int J Radat Biol. 1977;62:481–486. doi: 10.1080/09553009214552371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meerovich GA, Torshina NL, Loschenov VB, Stratonnikov AA, Volkova AI, Vorozhtsov GN, Kaliya OL, Lukyanets EA, Kogan BYa, Butenin AV, Kogan EA, Gladskikh OP, Polyakova LN. The experimental study of PDT with aluminum sulphophthalocyanine using sodium ascorbate and hyperbaric oxygenation. In: Ehrenberg B, Berg K, editors. Proc SPIE, Photochemotherapy of Cancer and Other Deseases. Vol. 3563. 1999. pp. 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gong XL. Effect of hematoporphyrin derivative (HPD) plus light on DNA repair synthesis and enhancement of HPD photosensitization by vitamin C in mouse hepatoma. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 1992;14:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen Y, Li C, Liu Y. Effect of ascorbate on the permeation and photosensitizing activity hematoporphyrin derivative (HPD) in tumor. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 1997;19:350–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gal’perin EI, Diuzheva TG, Nakhamiiaev VR, Goloshchapov RS, Bochkarev VP, Mogirev SV. Selective-occlusive method of drug administration in the treatment of experimental liver tumors. Khirurgiia. 2001;8:24–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kalija OL, Meerovich GA, Torshina NL, Loschenov VB, Kogan EA, Butenin AV, Vorozhtsov GN, Kuzmin SG, Volkova AI, Posypanova AM. The improvement of cancer PDT using sulphophtalocyanine and sodium ascorbate. In: Berg K, Ehrenberg B, Malik Z, Moan J, editors. Proc SPIE, Photochemotherapy: Photodynamic Therapy and Other Modalities III. Vol. 3191. 1997. pp. 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buettner GR. In the absence of catalytic metals, ascorbate does not autoxidize at pH 7: Ascorbate as a test for catalytic metals. J Biochem Biophys Meth. 1988;16:20–40. doi: 10.1016/0165-022x(88)90100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lemoli RM, Igarashi T, Knizewski M, Acaba L, Richter A, Jain A, Mitchell D, Levy J, Gulati SC. Dye-Mediated Photolysis Is Carable of Eliminating Drug-Resistant (MDR+) Tumor Cells. Blood. 1993;81:793–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aveline B, Hasan T, Redmond RW. Photophysical and Photosensitizing properties of benzoporphyrin Derivative Monoacid ring A (BPD-MA) Photochem Photobiol. 1994;59:328–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1994.tb05042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baker MA, Cerniglia GJ, Zaman A. Microtiter platereader assay for the measurement of glutathione and glutathione disulfide in large numbers of biological samples. Anal Biochem. 1990;190:360–365. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90208-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yusa TJ, Beckman S, Crapo JD, Freeman BA. Hyperoxia increases H2O2 production by brain in vivo. J Appl Physiol. 1987;63:353–8. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.1.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Royall JA, Gwin PD, Parks DA, Freeman BA. Responses of vascular endothelial oxidant metabolism to lipopolysaccharide and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;294:686–94. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90742-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wagner BA, Evig CB, Reszka KJ, Buettner GR, Burns CP. Doxorubicin increases intracellular hydrogen peroxide in PC3 prostate cancer cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;440:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cao E, Chen Y, Cui Z, Foster PR. Effect of freezing and thawing rates on denaturation of proteins in aqueous solutions. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2003;82:684–690. doi: 10.1002/bit.10612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Levine M, Wang Y, Rumsey SC. Analysis of ascorbic acid and dehydroascorbic acid in biological samples. Meth Enzymol. 1999;299:65–76. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)99009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bozeman PM, Learn DB, Thomas EL. Assay of the human leukocyte enzymes myeloperoxidase and eosinophil peroxidase. J Immunological Methods. 1990;126:125–133. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90020-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Runnels JM, Chen N, Kato D, Hassan T. BPD-MA-mediated photosensitization in vitro and in vivo: Cellular adhesion and β1 integrin expression in ovarian cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:946–953. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martin BN. Tissue Culture Techniques. Birkhäuser; Boston: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen Q, Espey MG, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB, Corpe CP, Buettner GR, Shacter E, Levine M. Ascorbic acid at pharmacologic concentrations selectively kills cancer cells: ascorbic acid as a pro-drug for hydrogen peroxide delivery to tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13604–13609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506390102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clement MV, Ramalingam J, Long LH, Halliwell B. The in vitro cytotoxicity of ascorbate depends on the culture medium used to perform the assay and involves hydrogen peroxide. Antioxdants & Redox Signaling. 2001;3:157–163. doi: 10.1089/152308601750100687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vera JC, Rivas CI, Zhang RH, Farber CM, Golde DW. Human HL-60 myeloid leukemia cells transport dehydroascorbic acid via the glucose transporter and accumulate reduced ascorbic acid. Blood. 1994;84:1628–1634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Park JB, Levine M. Intracellular accumulation of ascorbic acid is inhibited by flavonoids via blocking of dehydroascorbic acid and ascorbic acid uptakes in HL-60, U937 and Jurkat cells. J Nutrition. 2000;130:1297–302. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.5.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Koh WS, Lee SJ, Lee H, Park C, Park MH, Kim WS, Yoon SS, Park K, Hong SI, Chung MH, Park CH. Differential effects and transport kinetics of ascorbate derivatives in leukemic cell lines. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:2487–2493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guaiquil VH, Farber CM, Golde DW, Vera JC. Efficient transport and accumulation of vitamin C in HL-60 cells depleted of glutathione. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9915–9921. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Laggner H, Schmid S, Goldenberg H. Hypericin and photodynamic treatment do not interfere with transport of vitamin C during respiratory burst. Free Rad Res. 2004;38:1073–1081. doi: 10.1080/10715760412331284780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Winkler BS. Unequivocal evidence in support of the nonenzymatic redox coupling between glutathione/glutathione disulfide and ascorbic acid/dehydroascorbic acid. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1992;1117:287–290. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(92)90026-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schafer FQ, Buettner GR. Redox state of the cell as viewed though the glutathione disulfide/glutathione couple. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:1191–1212. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qin J, Ye N, Yu L, Liu D, Fung Y, Wang W, Ma X, Lin B. Simultaneous and ultrarapid determination of reactive oxygen species and reduced glutathione in apoptotic leukemia cells by microchip electrophoresis. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:1155–1162. doi: 10.1002/elps.200410136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gantchev TG, Hunting DJ. Enhancement of etoposide (VP-16) cytotoxicity by enzymatic and photodynamically induced oxidative stress. Anticancer Drugs. 1997;8:164–173. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199702000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hurst JK. Myeloperoxidase: Active site structure and catalytic mechanism. In: Everse J, Everse KE, Grisham MB, editors. Peroxidases in chemistry and biology, volume I. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cai X, Shen Y-L, Zhu Q, Jia P-M, Yu Y, Zhou L, Huang Y, Zhang J-W, Xiong S-M, Chen S-J, Wang Z-Y, Chen Z, Chen G-Q. Arsenic trioxide –induced apoptosis and differentiation are associated respectively with mitochondrial transmembrane potential collapse and retinoic acid signaling pathways in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2000;14:262–270. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wagner BA, Buettner GR, Oberley LW, Darby CJ, Burns CP. Myeloperoxidase is involved in H2O2-induced apoptosis of HL-60 human leukemia cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22461–22469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]