Abstract

Post-Golgi transport of peptide hormone-containing vesicles from the site of genesis at the trans-Golgi network to the release site at the plasma membrane is essential for activity-dependent hormone secretion to mediate various endocrinological functions. It is known that these vesicles are transported on microtubules to the proximity of the release site, and they are then loaded onto an actin/myosin system for distal transport through the actin cortex to just below the plasma membrane. The vesicles are then tethered to the plasma membrane, and a subpopulation of them are docked and primed to become the readily releasable pool. Cytoplasmic tails of vesicular transmembrane proteins, as well as many cytosolic proteins including adaptor proteins, motor proteins, and guanosine triphosphatases, are involved in vesicle budding, the anchoring of the vesicles, and the facilitation of movement along the transport systems. In addition, a set of cytosolic proteins is also necessary for tethering/docking of the vesicles to the plasma membrane. Many of these proteins have been identified from different types of (neuro)endocrine cells. Here, we summarize the proteins known to be involved in the mechanisms of sorting various cargo proteins into regulated secretory pathway hormone-containing vesicles, movement of these vesicles along microtubules and actin filaments, and their eventual tethering/docking to the plasma membrane for hormone secretion.

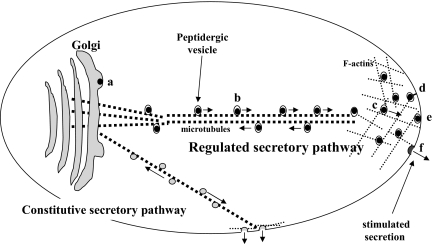

CELLS IN THE endocrine and nervous systems package peptide hormones, neuropeptide and specific neurotrophins [e.g. brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)], into secretory vesicles for release in a regulated manner upon stimulation. This is known as the regulated secretory pathway (RSP). Activity-dependent secretion of these molecules is critical for mediating various endocrine functions, neurotransmission, and neuronal plasticity (1,2,3,4). Secretion of these peptidergic vesicles requires them to be transported from the cell body where they are synthesized, to the secretion sites at the plasma membrane, which can be some distance away, e.g. at the nerve terminals in neurons. Within the cell body, peptidergic vesicles are formed at the trans-Golgi network (TGN) and transported along processes to the proximity of distal release sites, by a microtubule-based transport mechanism (see Fig. 1). Subsequently, peptidergic vesicles are transferred to cortical actin filaments. A pool of the vesicles is retained in the actin cortex as the reserve pool while another pool is tethered to the plasma membrane, and a subpopulation of them become docked (immobilized) and primed to form the readily releasable pool. During stimulation, docked and primed peptidergic vesicles in the readily releasable pool immediately fuse to the plasma membrane to release their contents into the extracellular space. The reserve vesicle pool then replenishes the vesicles in the readily releasable pool that have been depleted by exocytosis.

Figure 1.

Steps for post-Golgi RSP Vesicle Transport to the Release Site

Multiple steps are involved in transporting hormone-containing vesicles from the site of biogenesis at the TGN to the release site in the regulated secretory pathway: a, vesicle budding; b, microtubule-based transport; c, actin-based transport; d, vesicle tethering; e, docking; and f, fusion with the plasma membrane. These steps share some commonality with the trafficking of constitutive secretory vesicles, but there are differences as well (see Table 1).

In addition to the RSP, (neuro)endocrine cells, like all other cells, also have a constitutive secretory pathway (CSP) that supports continuous protein secretion, independent of stimulation (5). In the CSP, small secretory vesicles formed at the TGN are constantly transported to and fused to the plasma membrane without forming any storage pool (see Fig. 1). CSP vesicles are either directly transported to the plasma membrane from the TGN, or they pass through intermediate endosomal compartments (e.g. early/late endosome and recycling compartments) before reaching the plasma membrane (6,7). Because CSP proteins are continuously secreted, the CSP is mainly driven by the biosynthetic rate of secretory proteins at the endoplasmic reticulum (8). The CSP in (neuro)endocrine cells provide membrane proteins, such as receptors (9), to the plasma membrane, as well as various secretory proteins (10,11), for maintenance of cell survival, differentiation, and growth.

In this review we will focus our discussion primarily on the various cytoplasmic machineries that are involved in mediating post-Golgi RSP vesicle sorting and transport to the release site, as well as vesicle tethering to the plasma membrane (see Fig. 1). A comparison with CSP vesicle transport will be made. We will also discuss the mechanisms of sorting peptide hormone precursors into the RSP vesicles, but only briefly, because comprehensive reviews on this subject have been published by Blazquez and Shennan (12) and, more recently, by Dikeakos and Reudelhuber (13). The protein machinery involved in the priming, fusion, and exocytosis of vesicles at the plasma membrane will not be included in this review.

PROTEIN SORTING INTO RSP VESICLES

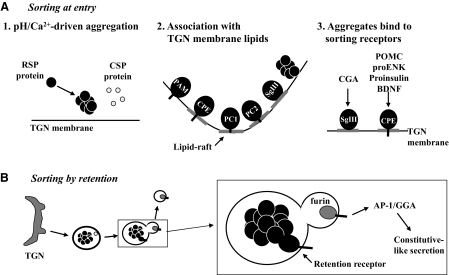

In this section, we will briefly discuss the various mechanisms proposed for the sorting of peptide hormone precursors and processing enzymes and granins into the RSP of (neuro)endocrine cells. Two modes of RSP protein sorting have been described: sorting-at-entry and sorting-by-retention [see reviews by Blazquez and Shennan (12), and Dikeakos and Reudelhuber (13)].

Mechanisms for sorting-at-entry are divided into different subcatergories (Fig. 2A). One mechanism involves initial aggregation of the cargo proteins such as the peptide hormone precursors and granins in a pH (6.0–6.5)- and cation-dependent manner (see “pH/Ca2+-driven aggregation” in Fig. 2). The aggregation process excludes the constitutive proteins (14,15,16,17). Thereafter, the aggregate binds to the TGN membrane, in some cases via a receptor protein (see “Aggregates bind to sorting receptors in Fig. 2). An example of such a sorting receptor is the membrane form of carboxypeptidase E (CPE), which has been demonstrated to sort proopiomelanocortin (POMC)/ACTH (18) and pro-BDNF (19), at the TGN to the RSP in pituitary cells and hippocampal neurons, respectively. This function of CPE has been debated and discussed in a recent review by Dikeakos and Reudelhuber (13). Secretogranin III (SgIII), a protein associated with cholesterol-sphingolipid-rich membrane microdomains (lipid rafts), at the TGN has been shown to be an RSP-sorting receptor for chromogranin A (20). SgIII was also proposed to play a distal role in sorting POMC to the RSP by transferring POMC from CPE to SgIII (21). However, this phenomenon seems redundant given that CPE can carry POMC into RSP vesicles.

Figure 2.

RSP Protein-Sorting Mechanisms

A, Sorting at entry (at the TGN): 1) Low pH and high Ca2+ concentration-drive RSP protein aggregation which excludes CSP proteins; 3) Protein aggregates associate with the TGN membrane, through direct interaction with lipids, some specifically at lipid-rafts, or 2) by protein-protein interaction with protein sorting receptors: e.g. CPE is a proposed RSP-sorting receptor for POMC, proenkephalin (proENK), proinsulin, and BDNF, whereas SgIII is a proposed sorting receptor for chromogranin A (CgA). The TGN membrane then buds to form the vesicle bringing along the aggregated protein cargo. B, Sorting by retention: in this model, RSP proteins along with some CSP proteins enter the immature secretory vesicle formed at the TGN. During maturation of the secretory vesicle, the RSP proteins are retained in the maturing vesicle by binding to a retention receptor, e.g. in pancreatic β-cells immature vesicles, membrane CPE binds and retains insulin (34) whereas CSP proteins (e.g. furin) are removed from the vesicle by an AP-1/GGA/clathrin-mediated budding mechanism to yield constitutive-like vesicles for secretion.

Another sorting-at-entry mechanism that has been proposed is one used by several prohormone processing enzymes, which involves direct insertion of the C-terminal domain of the enzyme into lipid rafts at the TGN. The transmembrane domains of several prohormone-processing enzymes have been shown to mediate their own sorting to the RSP (see “Association with TGN membrane lipids” in Fig. 2). For example, the transmembrane domain of α-amidating monooxygenase (PAM) contains information for correct routing of PAM to the RSP (22). Additionally, the C-terminal transmembrane domains of CPE, prohormone convertase 1/3 (PC1/3), and prohormone convertase 2 (PC2), are associated with lipid rafts and crucial for their own targeting to the RSP (23,24,25,26). Whereas the evidence for transmembrane orientation of CPE from two different laboratories is quite clear from biochemical (23) and functional studies (27,28), the transmembrane orientation of PC1/3 and PC2 is considered tentative among some investigators in the field. Nevertheless, it is generally accepted that the association of processing enzymes with lipids at the TGN is necessary for their sorting to the RSP (29,30,31,32).

The mechanism for sorting-by-retention was first proposed by Arvan and Castle (33) for sorting of proinsulin in pancreatic β-cells (Fig. 2B). They observed that along with proinsulin, other proteins such as lysosomal enzymes were present in the immature granule compartment, which were subsequently removed by budding off of constitutive-like vesicles, whereas insulin was retained in the maturing vesicle (33). Our studies suggest that CPE may act as a retention receptor in this immature vesicle compartment, serving to retain insulin in pancreatic β-cell vesicles (34). In general, constitutively secreted proteins enter CSP vesicles by default [see review by Halban and Irminger (35)]. However, certain CSP proteins such as furin, a transmembrane enzyme, are packaged with the RSP proteins into immature secretory granules (36,37). Subsequent removal of furin from the immature vesicle requires that its cytoplasmic tail be phosphorylated by casein kinase-2 (38), and bind the adaptor protein 1 (AP-1) adaptor, phosphofurin acidic cluster sorting protein-1, in an ADP-ribosylation factor 1-dependent manner to initiate clathrin coating, followed by budding of furin-containing constitutive-like vesicles (39).

Hence, RSP proteins are segregated from CSP proteins and sorted into RSP-secretory vesicles at the TGN by aggregation, followed by membrane association of the aggregate either directly with lipids or via protein-sorting receptors. A secondary sorting step involves removal of CSP proteins that have inadvertently entered into RSP vesicles, by budding off of constitutive-like vesicles from the maturing RSP vesicle.

CYTOPLASMIC MACHINERY FOR POST-GOLGI VESICLE TRAFFICKING

Vesicle Coating and Budding at the TGN

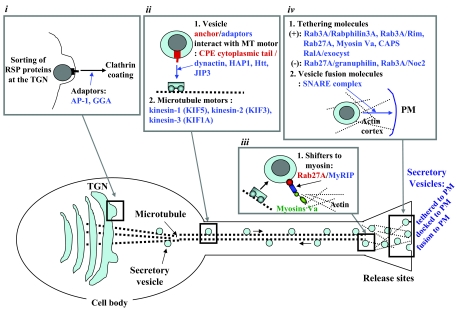

Clathrin coating is one of the mechanisms that drive budding and formation of vesicles at the TGN (see Fig. 3) (40). Both newly formed RSP (41) and CSP (42) vesicles that have just budded from the TGN contain a clathrin coat, which is then shed upon maturation of the vesicles (43,44). AP-1 and GGA (Golgi localized, γ-ear-containing ADP-ribosylation factor binding protein) are the major adaptor proteins that mediate clathrin coating on budding CSP vesicles, either independently, or cooperatively (45,46). In addition to the TGN vesicle budding, AP-1 also mediates sorting of furin from intermediate/recycling compartments back to the TGN (47). Both AP-1 and GGA are also found on immature RSP-secretory vesicles (48,49,50), suggesting that both these molecules might mediate clathrin coating of budding RSP vesicles as well.

Figure 3.

Hormone Vesicle Transport in the Regulated Secretory Pathway of (Neuro)Endocrine Cells

Molecules mediating different steps of vesicle transport to the RSP are shown in this model. Peptide hormones and neuropeptides are sorted and packaged into immature clathrin-coated vesicles at the TGN. The adaptors that might be involved in clathrin coating of budding RSP vesicles at the TGN are outlined in box i. The immature vesicles are then anchored to the microtubule (MT)-based transport system via linkers such as the cytoplasmic tail of vesicular transmembrane CPE and adaptors such as dynactin, which recruits various kinesin motor proteins (box ii) to effect movement to the proximity of the release site. The vesicles are then shifted from the microtubule-based system to the myosin transport system that moves these vesicles through the actin cortex to the proximity of the plasma membrane, forming a reserve vesicle pool. The recruitment of the vesicles to the myosin-based transport system is facilitated by rabGTPases and their effector molecules, outlined in box iii. A population of vesicles from the reserve pool are then moved and tethered to the plasma membrane via tethering molecules (box iv). In addition to positive tethering molecules, there are negative ones as well as indicated. A subpopulation of the tethered vesicles are then immobilized on the plasma membrane by SNARE complex (docking) and primed to become the readily releasable pool. Upon stimulation, the docked and primed vesicles are exocytosed, releasing the vesicle contents into the extracellular space. PM, Plasma membrane; MT, microtubule; HAP1, Huntington-associated protein 1; Htt, Huntington; KIF, kinesin-like family; MyRIP, myosin VIIa- and Rab-interacting protein.

Several accessory cytosolic proteins assist with AP-1-mediated clathrin coating of CSP vesicles by binding to the cytoplasmic tail of integral membrane CSP vesicle proteins such as β-secretase, sorLA (sorting protein-related receptor containing LDLR class A repeats), mannose-6-phosphate receptor (40), and furin (39), which contain AP-1 and GGA binding motifs. For example, phosphofurin acidic cluster sorting protein-1 facilitates binding of AP-1 to the acidic residues of furin cytoplasmic tail (39), and epsin-R is needed for AP-1-based packaging of mannose-6-phosphate receptor into clathrin-coated vesicles (51). γ-Synergin (52), aftiphilin (53), and adaptin-ear-binding coat-associated protein (54) also interact with AP-1, but their actual function in clathrin coating of vesicles at the TGN is unclear. Although likely, a role of these proteins in recruiting AP-1/GGA or the accessory proteins to RSP vesicles remains to be substantiated.

Microtubule-Based Vesicle Transport

Subsequent to budding from the TGN, both RSP and CSP vesicles are transported to the secretion sites at the plasma membrane via microtubule-based transport systems (see Fig. 3). Microtubules have been shown to mediate transport of RSP vesicles such as TRH vesicles in neurons of the paraventricular nucleus (55) and chromogranin B vesicles from the cell body to the proximity of the plasma membrane in AtT20 cells, a corticotroph cell line, and PC12 cells, a neuroendocrine cell line (56). Similarly, CSP vesicles containing growth factors, such as nerve growth factor, neurotrophin-3 and neurotrophin-4, and membrane proteins such as amyloid precursor protein (APP), are also transported by a microtubule-based system (57).

Vesicle anchors and adaptors (see Fig. 3) are required to anchor RSP and CSP vesicles to microtubule motors. Anterograde transport of BDNF-containing vesicles is facilitated by the adaptors dynactin and huntingtin-associated protein-1 (58). Although it has been shown that CPEs exist as soluble and peripheral membrane forms (59,60,61,62,63), our work supports the idea that there is a subpopulation of transmembrane CPE (23). We demonstrated that CPE has an atypical transmembrane α-helical structure (at an acidic pH 5.5–6.5 found in TGN and secretory granules), within the C terminus, and a cytoplasmic tail (23). Although the physicochemical properties of this domain would predict an energetically unfavorable presence in a membrane, the existence of other proteins within the cell that reduce the free energy and which then allow this transmembrane orientation cannot be ruled out, especially in light of the live cell imaging of the dominant-negative nature of a cytosolically expressed C-terminal tail of CPE (64). However, in the absence of any further studies to refute this data, the existence of a CPE C-terminal transmembrane domain and cytoplasmic tail remains a matter of debate with some investigators. The cytoplasmic tail of vesicular transmembrane CPE has been demonstrated not only to mediate recycling of endocytosed vesicles to the Golgi (27,28) but also to anchor ACTH vesicles to microtubule motors via interaction with the adaptor, dynactin (64). Although the size of the transmembrane pool has not been determined, only a small number of CPE cytoplasmic tails need to be present on peptide hormone- and BDNF-containing vesicles because a single connection between the vesicle and the motor complex is sufficient for transport. In contrast, CPE is not a vesicle anchor for CSP vesicles (19). However, in specific CSP vesicles, for example, the cytoplasmic tail of the type I transmembrane protein, APP, was shown to interact with microtubule motors, via the adaptor, JNK-interacting protein 1b, to mediate anterograde transport (65,66).

In general, both RSP and CSP vesicles use the same type of microtubule motors, such as kinesin, for anterograde transport to the secretion sites, and cytoplasmic dynein for the retrograde transport back to the cell body (57). Kinesin-1, a major kinesin in (neuro)endocrine cells, is shown to transport RSP vesicles (67,68,69) as well as CSP vesicles to the microtubule plus ends located at the proximity of the plasma membrane (65,66). However, recent studies show that there is a subset of microtubule motors specialized for transport of RSP vesicles. Kinesin-2 and kinesin-3 [kinesin-loke family (KIF)1A] are reported to mediate anterograde transport of ACTH vesicles in anterior pituitary cells (64). In Caenorhabditis elegans, Unc-104, the kinesin-3 ortholog, mediates anterograde trafficking of synaptic vesicles and peptidergic RSP vesicles to the nerve terminals (70,71) via the adaptor, JNK-interacting protein 3 (72).

Interestingly, the activity and/or distribution of kinesin along the microtubules are modulated to favor RSP vesicle secretion during stimulation. For example, forskolin, the adenyl cyclase activator, increased the velocity of peptidergic vesicle trafficking in neuroblastoma NS20Y cells (73), putatively by affecting the activity of a yet unidentified kinesin. Another secretagogue, carbachol, induces changes in the activity and intracellular distribution of kinesin-1 in the acinar cells of rabbit lacrimal gland (67). Indeed, kinesin-1 purified from carbachol-treated acinar cells shows enhanced in vitro microtubule-gliding activity compared with unstimulated cells. In a partitioning analysis using a dextran-polyethyleneglycol two-phase system, a distributional shift of kinesin-1 from a Golgi compartment to the β-hexosaminidase-containing post-Golgi secretory vesicles was observed in these cells. This study suggests that carbachol-triggered signaling drives kinesin-1 to facilitate stimulated secretion of β-hexosaminidase. Similar stimulation-based redistribution of kinesin-1 to the RSP zymogen granules was also observed in pancreatic acinar cells treated with cholecystokinin or secretin (74).

For CSP vesicles, regulation of APP vesicle transport from the Golgi apparatus to the neurite terminal, by presenilin-1 found in these vesicles, has been reported (75,76). Presenilin-1 regulates the transport via the interaction of its cytoplasmic tail with glycogen synthase kinase 3b, which phosphorylates kinesin light chain 1, leading to inhibition of kinesin-1-mediated axonal transport of APP (77,78).

Thus, during microtubule-based transport, both RSP and CSP vesicles use a similar microtubule motor system. Considerable advancement has been made in identifying RSP and CSP vesicular transmembrane proteins and which cytoplasmic tails bind to different adaptors and microtubule motors to mediate transport. Factors that modulate microtubule activity and distribution that enhance RSP vesicle transport during stimulation of the cell have also been elucidated, thus increasing our understanding of regulation of vesicular transport in the RSP.

Transfer of Vesicles from Microtubules to the Actin Cortex

At the end of microtubule-based transport, both RSP and CSP vesicles are transferred to the actin cortex close to the plasma membrane (see Fig. 3). Myosin V, the F-actin motor protein, has been proposed to mediate the shifting of secretory vesicles from microtubules to the actin cortex via its direct interaction with microtubule-based motors (79,80,81), although this proposal needs further investigation because there is some controversy in the field. Myosin V, then, traffics both CSP (82,83) and RSP (84,85,86) vesicles through the F-actin-rich cortical region to the secretion sites proximal to the plasma membrane. In addition to its role as the transport platform for myosin motors, F-actins also appear to function as a physical barrier for RSP vesicle exocytosis (87), but only transiently for CSP vesicles (87). Additionally, myosin II has been reported to be involved in both RSP vesicle transport and actin caging (88), although its role in this respect remains controversial.

Much more intensive studies have been conducted regarding trafficking of RSP vesicles vs. CSP vesicles through the actin cortex. Myosin Va has been shown as the major myosin that carries the RSP dense core vesicles from the reserve pool to the docked/readily releasable pool compartment for exocytosis. Expression of a headless mutant of myosin Va in PC12 cells not only prevented secretory vesicles from reaching the secretion sites at the plasma membrane, resulting in clustering of the vesicles away from the plasma membrane, but also decreased motility of the vesicles in the actin cortex (86). A similar negative effect was observed in chromaffin cells injected with antimyosin head antibodies (85). Regulated insulin secretion in pancreatic β-cells also depends on myosin Va (89,90). Both silencing of myosin Va and expression of headless myosin mutant significantly suppressed glucose- or depolarization-induced insulin secretion from INS-1 cells by decreasing the number of insulin granules tethered/docked to the plasma membrane. Thus myosin Va is responsible for coordinating late transport events of RSP vesicles preceding their exocytosis. Additionally, recruitment of myosin Va onto RSP vesicles appears to be mediated by the small GTPase Rab27A and its effectors (see Fig. 3). Myosin Va is linked to RSP vesicles via melanophilin/Rab27A in melanocytes (91). In adrenal chromaffin cells and PC12 cells, myosin-VIIa- and Rab-interacting protein/Rab27A connects RSP vesicles to myosin Va for transport of these vesicles through the actin cortex (92).

In addition, the integral membrane form of PAM may play a role in facilitating peptidergic RSP vesicle trafficking in the actin cortex. The cytoplasmic tail of PAM in peptide hormone vesicles interacts with PAM COOH-terminal interactor protein 2, a kinase that phosphorylates PAM, and kalirin, a Rho family GDP/GTP exchange factor and an F-actin reorganizer (93,94,95). The ability of kalirin to reorganize F-actins may influence the movement of such RSP vesicles through the actin cortex.

Although both RSP and CSP vesicles use the common actin-based transporter myosin V to reach the plasma membrane, different molecules appear to influence RSP or CSP vesicle transport through actin cortex. For instance, Rab27A and its effectors appear to function only in the RSP actin cortex and enhance connection of RSP vesicle to myosin V.

Vesicle Tethering to the Plasma Membrane

Movement of the RSP and CSP vesicles through the actin cortex is followed by tethering of the vesicles to the plasma membrane for exocytosis. For RSP vesicles there is a reserve pool that is not tethered to the plasma membrane. The majority of the RSP pool of vesicles that are tethered remain mobile, but a subpopulation of these are immobilized and docked and primed at the plasma membrane (the readily releasable pool), ready for exocytosis (see Fig. 3). RSP vesicle tethering and docking are facilitated by a variety of cytoplasmic molecules, including the small guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) Rab proteins and their effectors. A recent study shows that myosin Va mediates docking (immobilization) of RSP vesicles at the plasma membrane (96), independent of its motor activity. In contrast, CSP vesicle tethering is mediated by an eight-subunit protein complex known as the “exocyst” (97) that is found to mediate tethering of CSP vesicles to the plasma membrane in yeast (98) and mammalian epithelial cells (99), adipocytes (96,100,101), and neurons (102,103). The adaptor protein AP-1B (104) and the small GTPase TC10 (100,101,105) facilitate the exocyst-driven CSP vesicle tethering. Additionally, the exocyst is involved in tethering of insulin-containing RSP vesicles to the plasma membrane of pancreatic β-cells (90,106) via its interaction with the plasma membrane-associated small GTPase protein, RalA. However, the exocyst appears to mainly function in CSP vesicle tethering.

Rab3A and Rab27A are the major Rab proteins in the regulated secretory pathway which regulate not only tethering of RSP vesicles to the plasma membrane, but also assembly/disassembly of a fusion complex between the RSP vesicles and the plasma membrane during initial membrane contact (107,108,109). Both Rab3A and Rab27A are recruited to the newly synthesized RSP vesicles and associate with the vesicles constantly even after stimulation (110). There is also a group of Rab3A and Rab27A effectors that operate in the regulated secretory pathway: Rab3D, Rabphilin3A, Rab3-interacting molecule (Rim), and Noc2 for Rab3A, and granuphilin-a for Rab27A. Rab3D, which was originally found on the zymogen granules and enhances regulated secretion of amylase from pancreatic acini (111), is required for association of Rab3A with RSP vesicles. A mutant form of Rab3D (N135I) caused a failure in the association of Rab3A with ACTH vesicles, resulting in defective docking of ACTH vesicles to the plasma membrane of AtT20 cells (112,113). Rabphilin3A (114,115) and Rim1 (116) appear to bind to Rab3A that is already associated with RSP vesicles and enhance its activity via an unknown mechanism. Rabphilin3A is reported to potentiate Ca2+-induced exocytosis of GH from bovine adrenal chromaffin cells (115,117), whereas Rim1 is shown to facilitate Rab3A-mediated formation of a fusion complex between synaptic vesicles and the presynaptic membrane in the synapses of hippocampal neurons (116). Especially, Rim1 appears to scaffold the formation of the fusion complex by recruiting a number of components such as mammalian homolog of unc-(Munc)13-1 (118), synaptosomal associated protein SNAP25 (synaptosomal associated protein of 25 kDa), and synaptotagmin (119). Rim1 also interacts with Rim-binding protein, a Ca2+ channel coupler (120), as well as α-liprins (121) and ELKS (protein containing the high levels of the aminoacids E, L, K, S) Rab3-interacting molecules/(cytomatrix at the active zone) [CAST CAZ-associated structural protein] (122), although their functions are unclear.

Conversely, Noc2 and granuphilin-a negatively regulate the function of Rab3A (123) and Rab27A (124,125), respectively. Additionally, granuphilin-a has been shown to control Rab27A-dependent regulated secretion of neuropeptide Y from PC-12 cells (124), and insulin from the pancreatic β cell line, MIN6 (125) by controlling interaction of Rab27A with syntaxin 1a and Munc18-1, proteins involved in the SNARE (soluble N-ethyl maleimide sensitive-factor attachment protein receptor) complex and vesicle fusion (126,127).

In addition to Rabs and their effectors, Ca2+-dependent activator protein for secretion 1 (CAPS1) and CAPS 2 are involved in the recruitment, perhaps by enhancing tethering of insulin-containing vesicles to the plasma membrane (128,129). Chromaffin cells from embryonic CAPS1- or CAPS2-knockout mice show decreases in the number of docked insulin vesicles and the level of insulin secretion. The mechanism of vesicle recruitment mediated by CAPSs, however, is unknown.

Subsequent to tethering, RSP vesicles are docked, primed, and fused to the plasma membrane via a series of steps as follows (130,131,132,133,134). The GTP-bound form of Rab3A on RSP vesicles tethers vesicles to the plasma membrane via its binding to Rim1 on plasma membrane. Rim1 is then released from Rab3A upon GTP hydrolysis, which activates Munc13, which, in turn, initiates the interaction between syntaxin-1, SNAP25, and vesicle-associated membrane protein (also known as synaptobrevin) to form the SNARE complex. Upon Ca2+ influx by stimulation, the Ca2+ sensor synaptotagmin binds the SNARE complex and triggers membrane fusion between vesicles and the plasma membrane. After fusion, the SNARE complex is disassembled by NSF and α-SNAP for recycling.

Thus, many molecules have been identified and shown to be necessary for mediating RSP vesicle tethering, docking, priming, and fusion.

SUMMARY

In this review, we have highlighted the cytoplasmic proteins that play a role in the transport of regulated secretory pathway vesicles, primarily those containing peptide hormones, from the site of genesis at the TGN to the secretion site at the plasma membrane. A model showing the cytoplasmic proteins that participate in the transport and tethering of RSP hormone-containing vesicles drawn from studies using different cell systems is shown in Fig. 3. At the TGN (Fig. 3, box i), sorting of RSP proteins into immature vesicle takes place. The various mechanisms of protein sorting into vesicles via aggregation followed by association of the aggregates to the TGN membrane via interaction with lipid rafts, or protein-sorting receptors are discussed in section entitled “Protein Sorting into RSP Vesicles” and Fig. 2. Simultaneously, clathrin-driven vesicle budding occurs at the TGN, facilitated by the recruitment of adaptors such as AP-1 and GGA found on RSP vesicles. Post-Golgi transport of RSP vesicles is mediated by a microtubule-based machinery (Fig. 3, box ii). How are RSP vesicles anchored to microtubules? Our recent studies have indicated that the cytoplasmic tail of transmembrane CPE on ACTH vesicles in pituitary cells interacts with the adaptor protein dynactin, which in turn recruits the motor kinesin-2 (KIF3) and kinesin-3 (KIF1A) (64). Others have shown that kinesin-1, -2, and -3 are involved in RSP vesicle transport in various types of endocrine cells. The microtubule-based transport system carries the RSP vesicles to the proximity of the release site at the plasma membrane. There the RSP vesicles are loaded on to the myosin V transport system (Fig. 3, box iii). The GTPase, rab27A, found associated with RSP vesicles, in conjunction with myosin-VIIa- and Rab-interacting protein, has been identified to play an important role in recruiting RSP vesicles on to the myosin transport system, which then moves them to the actin cortex where they are held as a reserve pool. Subsequently, a subpopulation of RSP vesicles are moved by the myosin system through the actin cortex, arriving just below the plasma membrane where they are tethered and some are docked to become the readily releasable pool. Thus, microtubules and F-actins function in a coordinated manner during vesicle transport to achieve precise delivery of hormone-containing RSP vesicles to the plasma membrane (56). The RSP vesicles are tethered to the plasma membrane via various molecules highlighted in Fig. 3, box iv. These include Rabs, primarily Rab3 and various effector molecules such as rabphillin and Rim1, that facilitate exocytosis.

Excessive membrane on the plasma membrane produced by exocytosis is removed by endocytosis [see review by Gundelfinger et al. (135)]. Thus, coupling between endocytosis and exocytosis is important to maintain constant membrane mass on the plasma membrane.

Comparison of cytoplasmic proteins involved in the transport of RSP and CSP vesicles revealed many commonalities, both in the clathrin-mediated budding process and the microtubule and actin-based trafficking mechanisms (Table 1). However, there are also differences, most significantly in the transport and tethering mechanisms within the actin cortex and at the plasma membrane, respectively (see Table 1). During post-Golgi transport, both RSP and CSP vesicles use microtubule-based motor systems, but each type of vesicle heads for distinctive destinations, e.g. to a reserve pool distant from the plasma membrane or directly to the plasma membrane for secretion, respectively. It has been speculated that variations in microtubule-associated proteins and posttranslational modification of microtubules (136) may distinguish the different routes. Hence, the different destinations of the RSP and CSP vesicles may be determined by selection of different subsets of microtubule motors that show high affinity to a certain route [e.g. kinesin-1 binds glutamylated microtubules more strongly (136)]. Indeed, the cytoplasmic tail of transmembrane CPE on RSP vesicles anchors on to dynactin, which interacts with kinesins, KIF1A and KIF3A, and a subset of modulators different from those present on CSP vesicles for movement (see Table 1). At the proximity of the plasma membrane, only RSP vesicles are captured in a reserve pool in the actin cortex. A subpopulation of RSP vesicles is tethered and docked to the plasma membrane using GTPase Rab proteins and a number of effectors (Fig. 3, box iv) and released upon stimulation. In contrast, CSP vesicles are tethered to the plasma membrane using the exocyst machinery and exocytose mostly in an unregulated manner (98,99,137).

Table 1.

Comparison of Molecules Involved in Vesicle Traffic in the RSP and CSP

| Commonalities RSP/CSP | Differences

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| RSP | CSP | ||

| Vesicle budding from TGN | Adaptors: AP-1, GGA Clathrin coat | AP-1/GGA effectors: unknown | AP-1 effectors: PACS-1, γ-synerigin, aftiphilin, NECAP |

| Vesicle transport along MTs | MT motors: kinesin-1 cytoplasmic dynein | MT motors/modulators: kinesin-3/JIP3 | MT motor/modulators: kinesin-1/PS1/APH-1/PEN-2/nicastrin kinesin-1/JIP1b |

| kinesin/dynactin-HAP1-Htt kinesin-2 and -3/dynactin | |||

| Vesicle transport in actin cortex | F-actin motor; myosin Va | Myosin Va recruiter: Rab27A/MyRIP Rab27A/melanophilin | Myosin Va recruiter: unknown but maybe Rabs |

| Interaction of PAM with actins | |||

| Vesicle tethering to PM | F-actins-based stabilization of tethered/docked vesicles on PM | Rab3A with Rab3D, Rim-1, Rabphilin3A, Noc2 | Exocyst |

| Rab27A with granuphilin-1 | |||

| CAPS | |||

| RalA/exocyst | |||

PM, Plasma membrane; TGN, trans-Golgi network; JIP, JNK-interacting protein; PACS-1, phosphofurin acidic cluster sorting protein-1; NECAP, adaptin-ear-binding coat-associated protein; PS1, presenilin 1; APH-1, anterior pharynx-defective-1; PEN-2, presenilin enhancer-2.

It is also intriguing how multiple cytoplasmic molecules can fit and work together within a limited space beneath a single RSP vesicle without any steric hindrance to mediate trafficking and tethering to the plasma membrane. Studies now show that this phenomenon can be accomplished by usage of multisubunit protein complexes such as dynactin (138), or a scaffolding protein such as Rim1, which interacts with multiple proteins (118,122,139,140). A multisubunit protein complex or scaffold protein capable of binding several proteins simultaneously can function as a multiarm adaptor to allow even a single cytoplasmic tail to interact with multiple proteins at the same time. This is exemplified by our recent study showing that the CPE cytoplasmic tail found in all peptide hormone-containing vesicles interacts with dynactin (64), which consists of 11 different subunits. This enables various adaptor proteins (138) to be recruited to the CPE tail to mediate transport, tethering, and docking of RSP vesicles to the plasma membrane for exocytosis in (neuro)endocrine cells.

Another question is how do different molecules corroborate to drive vesicles in one direction vs. another. So far, there are various proposed hypotheses regarding this issue. For example, in the tug-of-war model (141,142), microtubule motors of opposite polarity compete with each other whereas motors of the same polarity increase the speed of vesicle movement. One recent study shows a cooperative effort between kinesin-1 and myosin V (143) for processive vesicle movement. Myosin V confers processivity to kinesin-driven movement on microtubules whereas kinesin-1 confers it to myosin-mediated movement on F-actins. However, because this study is based on in vitro experiments, the cooperation might not occur in vivo. Thus, further study is necessary to verify this phenomenon in vivo.

In conclusion, the understanding of the cytoplasmic mechanism(s) that coordinate the trafficking and tethering of hormone-containing vesicles to the plasma membrane in the regulated secretory pathway of (neuro)endocrine cells is still at its infancy. The field has only just begun to identify the different vesicular transmembrane and cytosolic proteins that mediate these transport and tethering processes, and much of the data are derived and assembled in our model (Fig. 3) from studies of different (neuro)endocrine cell types. To this end, these players serve as excellent candidates for studying vesicle trafficking in the specific neuroendocrine cell system of interest. However, as a cautionary note, it cannot be assumed that all RSP peptidergic vesicles use the same vesicular anchors, motors, and cytosolic effector proteins in different neuroendocrine cell types for trafficking and tethering to the plasma membrane, although there is much in common as the literature indicates. What is certain is that the differences between RSP and CSP vesicle transport (Table 1) will stand.

It is clear that there are still many unanswered questions. How are the different cytosolic proteins selectively recruited to RSP vesicles but not CSP vesicles? What initiates and mediates the recruitment of different proteins to assemble the transport machinery complex? How are the recruited proteins switched during post-Golgi vesicle traffic through different junctions: microtubules, actin cortex, and finally the plasma membrane? Are the protein complexes and transport machinery modulated or reorganized in an activity-dependent manner? If so, how does stimulation induce the change? Ultimately, answers to these questions will fully uncover the transport and tethering mechanisms and the proteins that govern regulated secretion of peptide hormones and neuropeptides. This will eventually facilitate identification of endocrinological and neurological diseases associated with defects [e.g. mutations in the kinesin and dynactin genes (144,145,146,147,148)] in the proteins of the RSP vesicle transport system.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Niamh Cawley [National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Institutes of Health (NIH)], and Dr. Andre Phillips (NICHD, NIH) for their suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver, NICHD, NIH.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online July 31, 2008

Abbreviations: AP-1A, Adaptor protein 1A; APP, amyloid precursor protein; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CAPS, Ca2+-dependent activator protein for secretion; CSP, constitutive secretory pathway; CPE, carboxypeptidase E; GGA, Golgi localized, γ-ear-containing ADP-ribosylation factor binding protein; GTPase, guanosine triphosphatase; KIF, kinesin-like family; Munc18, mammalian homolog of unc-18; Noc2, no C2 domain; PAM, α-amidating monooxygenase; PC, prohormone convertase; POMC, proopiomelanocortin; Rim, Rab3-interacting molecule; RSP, regulated secretory pathway; SgIII, secretogranin III; SNAP25, synaptosomal associated protein of 25 kDa; SNARE, soluble N-ethyl maleimide sensitive-factor attachment protein receptor; SorLA, sorting protein-related receptor containing LDLR class A repeats; TGN, trans-Golgi network.

References

- Egan MF, Kojima M, Callicott JH, Goldberg TE, Kolachana BS, Bertolino A, Zaitsev E, Gold B, Goldman D, Dean M, Lu B, Weinberger DR 2003 The BDNF val66met polymorphism affects activity-dependent secretion of BDNF and human memory and hippocampal function. Cell 112:257–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemin R, Vargo T, Rossier J, Minick S, Ling N, Rivier C, Vale W, Bloom F 1977 β-Endorphin and adrenocorticotropin are selected concomitantly by the pituitary gland. Science 197:1367–1369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte Jr D, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG 2000 Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature 404:661–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoenen H 2000 Neurotrophins and activity-dependent plasticity. Prog Brain Res 128:183–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RB 1985 Pathways of protein secretion in eukaryotes. Science 230:25–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futter CE, Connolly CN, Cutler DF, Hopkins CR 1995 Newly synthesized transferrin receptors can be detected in the endosome before they appear on the cell surface. J Biol Chem 270:10999–11003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnambalam S, Baldwin SA 2003 Constitutive protein secretion from the trans-Golgi network to the plasma membrane. Mol Membr Biol 20:129–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland FT, Gleason ML, Serafini TA, Rothman JE 1987 The rate of bulk flow from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cell surface. Cell 50:289–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Zastrow M, Link R, Daunt D, Barsh G, Kobilka B 1993 Subtype-specific differences in the intracellular sorting of G protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem 268:763–766 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green R, Shields D 1984 Somatostatin discriminates between the intracellular pathways of secretory and membrane proteins. J Cell Biol 99:97–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RB, Buckley KM, Burgess TL, Carlson SS, Caroni P, Hooper JE, Katzen A, Moore HP, Pfeffer SR, Schroer TA 1983 Membrane traffic in neurons and peptide-secreting cells. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 48:697–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazquez M, Shennan KI 2000 Basic mechanisms of secretion: sorting into the regulated secretory pathway. Biochem Cell Biol 78:181–191 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikeakos JD, Reudelhuber TL 2007 Sending proteins to dense core secretory granules: still a lot to sort out. J Cell Biol 177:191–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauerfeind R, Huttner WB 1993 Biogenesis of constitutive secretory vesicles, secretory granules and synaptic vesicles. Curr Opin Cell Biol 5:628–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canaff L, Brechler V, Reudelhuber TL, Thibault G 1996 Secretory granule targeting of atrial natriuretic peptide correlates with its calcium-mediated aggregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:9483–9487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanat E, Huttner WB 1991 Milieu-induced, selective aggregation of regulated secretory proteins in the trans-Golgi network. J Cell Biol 115:1505–1519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes HH, Rosa P, Phillips E, Baeuerle PA, Frank R, Argos P, Huttner WB 1989 The primary structure of human secretogranin II, a widespread tyrosine-sulfated secretory granule protein that exhibits low pH- and calcium-induced aggregation. J Biol Chem 264:12009–12015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cool DR, Normant E, Shen F, Chen HC, Pannell L, Zhang Y, Loh YP 1997 Carboxypeptidase E is a regulated secretory pathway sorting receptor: genetic obliteration leads to endocrine disorders in Cpe(fat) mice. Cell 88:73–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou H, Kim SK, Zaitsev E, Snell CR, Lu B, Loh YP 2005 Sorting and activity-dependent secretion of BDNF require interaction of a specific motif with the sorting receptor carboxypeptidase E. Neuron 45:245–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosaka M, Watanabe T, Sakai Y, Uchiyama Y, Takeuchi T 2002 Identification of a chromogranin A domain that mediates binding to secretogranin III and targeting to secretory granules in pituitary cells and pancreatic β-cells. Mol Biol Cell 13:3388–3399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosaka M, Watanabe T, Sakai Y, Kato T, Takeuchi T 2005 Interaction between secretogranin III and carboxypeptidase E facilitates prohormone sorting within secretory granules. J Cell Sci 118:4785–4795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgram SL, Mains RE, Eipper BA 1996 Identification of routing determinants in the cytosolic domain of a secretory granule-associated integral membrane protein. J Biol Chem 271:17526–17535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanvantari S, Arnaoutova I, Snell CR, Steinbach PJ, Hammond K, Caputo GA, London E, Loh YP 2002 Carboxypeptidase E, a prohormone sorting receptor, is anchored to secretory granules via a C-terminal transmembrane insertion. Biochemistry 41:52–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assadi M, Sharpe JC, Snell C, Loh YP 2004 The C-terminus of prohormone convertase 2 is sufficient and necessary for Raft association and sorting to the regulated secretory pathway. Biochemistry 43:7798–7807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanvantari S, Loh YP 2000 Lipid raft association of carboxypeptidase E is necessary for its function as a regulated secretory pathway sorting receptor. J Biol Chem 275:29887–29893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang CF, Dhanvantari S, Lou H, Loh YP 2003 Sorting of carboxypeptidase E to the regulated secretory pathway requires interaction of its transmembrane domain with lipid rafts. Biochem J 369:453–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaoutova I, Jackson CL, Al-Awar OS, Donaldson JG, Loh YP 2003 Recycling of Raft-associated prohormone sorting receptor carboxypeptidase E requires interaction with ARF6. Mol Biol Cell 14:4448–4457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CM, Chang HT, Chang MD 2004 Membrane-bound carboxypeptidase E facilitates the entry of eosinophil cationic protein into neuroendocrine cells. Biochem J 382:841–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvan P, Zhang BY, Feng L, Liu M, Kuliawat R 2002 Lumenal protein multimerization in the distal secretory pathway/secretory granules. Curr Opin Cell Biol 14:448–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glombik MM, Gerdes HH 2000 Signal-mediated sorting of neuropeptides and prohormones: secretory granule biogenesis revisited. Biochimie 82:315–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa H, Takata K 1995 The granin family—its role in sorting and secretory granule formation. Cell Struct Funct 20:415–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele C, Huttner WB 1998 Protein and lipid sorting from the trans-Golgi network to secretory granules-recent developments. Semin Cell Dev Biol 9:511–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvan P, Castle D 1998 Sorting and storage during secretory granule biogenesis: looking backward and looking forward. Biochem J 332:593–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanvantari S, Shen FS, Adams T, Snell CR, Zhang C, Mackin RB, Morris SJ, Loh YP 2003 Disruption of a receptor-mediated mechanism for intracellular sorting of proinsulin in familial hyperproinsulinemia. Mol Endocrinol 17:1856–1867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halban PA, Irminger JC 1994 Sorting and processing of secretory proteins. Biochem J 299:1–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannies PS 1999 Protein hormone storage in secretory granules: mechanisms for concentration and sorting. Endocr Rev 20:3–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuliawat R, Klumperman J, Ludwig T, Arvan P 1997 Differential sorting of lysosomal enzymes out of the regulated secretory pathway in pancreatic β-cells. J Cell Biol 137:595–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittie AS, Thomas L, Thomas G, Tooze SA 1997 Interaction of furin in immature secretory granules from neuroendocrine cells with the AP-1 adaptor complex is modulated by casein kinase II phosphorylation. EMBO J 16:4859–4870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump CM, Xiang Y, Thomas L, Gu F, Austin C, Tooze SA, Thomas G 2001 PACS-1 binding to adaptors is required for acidic cluster motif-mediated protein traffic. EMBO J 20:2191–2201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K, Wakatsuki S 2003 The structure and function of GGAs, the traffic controllers at the TGN sorting crossroads. Cell Struct Funct 28:431–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner DF, Michael J, Houghten R, Mathieu M, Gardner PR, Ravazzola M, Orci L 1987 Use of a synthetic peptide antigen to generate antisera reactive with a proteolytic processing site in native human proinsulin: demonstration of cleavage within clathrin-coated (pro)secretory vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84:6184–6188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teuchert M, Schafer W, Berghofer S, Hoflack B, Klenk HD, Garten W 1999 Sorting of furin at the trans-Golgi network. Interaction of the cytoplasmic tail sorting signals with AP-1 Golgi-specific assembly proteins. J Biol Chem 274:8199–8207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tooze J, Tooze SA 1986 Clathrin-coated vesicular transport of secretory proteins during the formation of ACTH-containing secretory granules in AtT20 cells. J Cell Biol 103:839–850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Nesterov A, Carter RE, Sorkin A 2001 Trafficking of yellow-fluorescent-protein-tagged mu1 subunit of clathrin adaptor AP-1 complex in living cells. Traffic 2:345–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino JS 2004 The GGA proteins: adaptors on the move. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5:23–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doray B, Ghosh P, Griffith J, Geuze HJ, Kornfeld S 2002 Cooperation of GGAs and AP-1 in packaging MPRs at the trans-Golgi network. Science 297:1700–1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas G 2002 Furin at the cutting edge: from protein traffic to embryogenesis and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3:753–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakhlon O, Sakya P, Larijani B, Watson R, Tooze SA 2006 GGA function is required for maturation of neuroendocrine secretory granules. EMBO J 25:1590–1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittie AS, Hajibagheri N, Tooze SA 1996 The AP-1 adaptor complex binds to immature secretory granules from PC12 cells, and is regulated by ADP-ribosylation factor. J Cell Biol 132:523–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauloin A, Tooze SA, Michelutti I, Delpal S, Ollivier-Bousquet M 1999 The majority of clathrin coated vesicles from lactating rabbit mammary gland arises from the secretory pathway. J Cell Sci 112:4089–4100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills IG, Praefcke GJ, Vallis Y, Peter BJ, Olesen LE, Gallop JL, Butler PJ, Evans PR, McMahon HT 2003 EpsinR: an AP1/clathrin interacting protein involved in vesicle trafficking. J Cell Biol 160:213–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page LJ, Sowerby PJ, Lui WW, Robinson MS 1999 γ-Synergin: an EH domain-containing protein that interacts with γ-adaptin. J Cell Biol 146:993–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst J, Borner GH, Harbour M, Robinson MS 2005 The aftiphilin/p200/γ-synergin complex. Mol Biol Cell 16:2554–2565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattera R, Ritter B, Sidhu SS, McPherson PS, Bonifacino JS 2004 Definition of the consensus motif recognized by γ-adaptin ear domains. J Biol Chem 279:8018–8028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander K, Nikodemova M, Kucerova J, Strbak V 2005 Colchicine treatment differently affects releasable thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) pools in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and the median eminence (ME). Cell Mol Neurobiol 25:681–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolf R, Salm T, Rustom A, Gerdes HH 2001 Dynamics of immature secretory granules: role of cytoskeletal elements during transport, cortical restriction, and F-actin-dependent tethering. Mol Biol Cell 12:1353–1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein LS, Yang Z 2000 Microtubule-based transport systems in neurons: the roles of kinesins and dyneins. Annu Rev Neurosci 23:39–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier LR, Charrin BC, Borrell-Pages M, Dompierre JP, Rangone H, Cordelieres FP, De Mey J, MacDonald ME, Lessmann V, Humbert S, Saudou F 2004 Huntingtin controls neurotrophic support and survival of neurons by enhancing BDNF vesicular transport along microtubules. Cell 118:127–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackin RB, Noe BD 1987 Characterization of an islet carboxypeptidase B involved in prohormone processing. Endocrinology 120:457–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson HW, Hutton JC 1987 The insulin-secretory-granule carboxypeptidase H. Purification and demonstration of involvement in proinsulin processing. Biochem J 245:575–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson D 1990 Two soluble forms of bovine carboxypeptidase H have different NH2-terminal sequences. J Biol Chem 265:17101–17105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker LD, Das B, Angeletti RH 1990 Identification of the pH-dependent membrane anchor of carboxypeptidase E (EC 3.4.17.10). J Biol Chem 265:2476–2482 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra A, Song L, Fricker LD 1994 The C-terminal region of carboxypeptidase E is involved in membrane binding and intracellular routing in AtT-20 cells. J Biol Chem 269:19876–19881 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JJ, Cawley NX, Loh YP 2008 Carboxypeptidase E cytoplasmic tail-driven vesicle transport is key for activity-dependent secretion of peptide hormones. Mol Endocrinol 22:989–1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inomata H, Nakamura Y, Hayakawa A, Takata H, Suzuki T, Miyazawa K, Kitamura N 2003 A scaffold protein JIP-1b enhances amyloid precursor protein phosphorylation by JNK and its association with kinesin light chain 1. J Biol Chem 278:22946–22955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taru H, Iijima K, Hase M, Kirino Y, Yagi Y, Suzuki T 2002 Interaction of Alzheimer’s β-amyloid precursor family proteins with scaffold proteins of the JNK signaling cascade. J Biol Chem 277:20070–20078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm-Alvarez SF, Da Costa S, Yang T, Wei X, Gierow JP, Mircheff AK 1997 Cholinergic stimulation of lacrimal acinar cells promotes redistribution of membrane-associated kinesin and the secretory protein, β-hexosaminidase, and increases kinesin motor activity. Exp Eye Res 64:141–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senda T, Yu W 1999 Kinesin cross-bridges between neurosecretory granules and microtubules in the mouse neurohypophysis. Neurosci Lett 262:69–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varadi A, Tsuboi T, Johnson-Cadwell LI, Allan VJ, Rutter GA 2003 Kinesin I and cytoplasmic dynein orchestrate glucose-stimulated insulin-containing vesicle movements in clonal MIN6 β-cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 311:272–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DH, Hedgecock EM 1991 Kinesin-related gene unc-104 is required for axonal transport of synaptic vesicles in C. elegans. Cell 65:837–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka AJ, Jeyaprakash A, Garcia-Anoveros J, Tang LZ, Fisk G, Hartshorne T, Franco R, Born T 1991 The C. elegans unc-104 gene encodes a putative kinesin heavy chain-like protein. Neuron 6:113–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd DT, Kawasaki M, Walcoff M, Hisamoto N, Matsumoto K, Jin Y 2001 UNC-16, a JNK-signaling scaffold protein, regulates vesicle transport in C. elegans. Neuron 32:787–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn CL, Bean JE, Silverman MA, Pellegrino MJ, Yates PA, Allen RG 2002 Regulation of peptidergic vesicle mobility by secretagogues. Traffic 3:801–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe KJ, Farshori P, Torgerson RR, Anderson KL, Miller LJ, McNiven MA 1998 Changes in kinesin distribution and phosphorylation occur during regulated secretion in pancreatic acinar cells. Eur J Cell Biol 75:140–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai D, Leem JY, Greenfield JP, Wang P, Kim BS, Wang R, Lopes KO, Kim SH, Zheng H, Greengard P, Sisodia SS, Thinakaran G, Xu H 2003 Presenilin-1 regulates intracellular trafficking and cell surface delivery of β-amyloid precursor protein. J Biol Chem 278:3446–3454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leem JY, Saura CA, Pietrzik C, Christianson J, Wanamaker C, King LT, Veselits ML, Tomita T, Gasparini L, Iwatsubo T, Xu H, Green WN, Koo EH, Thinakaran G 2002 A role for presenilin 1 in regulating the delivery of amyloid precursor protein to the cell surface. Neurobiol Dis 11:64–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morfini G, Szebenyi G, Elluru R, Ratner N, Brady ST 2002 Glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylates kinesin light chains and negatively regulates kinesin-based motility. EMBO J 21:281–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigino G, Morfini G, Pelsman A, Mattson MP, Brady ST, Busciglio J 2003 Alzheimer’s presenilin 1 mutations impair kinesin-based axonal transport. J Neurosci 23:4499–4508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JR, Peacock-Villada EM, Langford GM 2002 Globular tail fragment of myosin-V displaces vesicle-associated motor and blocks vesicle transport in squid nerve cell extracts. Biol Bull 203:210–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JR, Simonetta KR, Sandberg LA, Stafford P, Langford GM 2001 Recombinant globular tail fragment of myosin-V blocks vesicle transport in squid nerve cell extracts. Biol Bull 201:240–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JD, Brady ST, Richards BW, Stenolen D, Resau JH, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA 1999 Direct interaction of microtubule- and actin-based transport motors. Nature 397:267–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SL, Gelfand VI 2000 Membrane trafficking, organelle transport, and the cytoskeleton. Curr Opin Cell Biol 12:57–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruyne DW, Schott DH, Bretscher A 1998 Tropomyosin-containing actin cables direct the Myo2p-dependent polarized delivery of secretory vesicles in budding yeast. J Cell Biol 143:1931–1945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler TW, Kogel T, Bukoreshtliev NV, Gerdes HH 2006 The role of myosin Va in secretory granule trafficking and exocytosis. Biochem Soc Trans 34:671–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose SD, Lejen T, Casaletti L, Larson RE, Pene TD, Trifaro JM 2003 Myosins II and V in chromaffin cells: myosin V is a chromaffin vesicle molecular motor involved in secretion. J Neurochem 85:287–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolf R, Kogel T, Kuznetsov SA, Salm T, Schlicker O, Hellwig A, Hammer III JA, Gerdes HH 2003 Myosin Va facilitates the distribution of secretory granules in the F-actin rich cortex of PC12 cells. J Cell Sci 116:1339–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giau R, Carrette J, Bockaert J, Homburger V 2005 Constitutive secretion of protease nexin-1 by glial cells and its regulation by G-protein-coupled receptors. J Neurosci 25:8995–9004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neco P, Giner D, Viniegra S, Borges R, Villarroel A, Gutierrez LM 2004 New roles of myosin II during vesicle transport and fusion in chromaffin cells. J Biol Chem 279:27450–27457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivarsson R, Jing X, Waselle L, Regazzi R, Renstrom E 2005 Myosin 5a controls insulin granule recruitment during late-phase secretion. Traffic 6:1027–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varadi A, Tsuboi T, Rutter GA 2005 Myosin Va transports dense core secretory vesicles in pancreatic MIN6 β-cells. Mol Biol Cell 16:2670–2680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom M, Hume AN, Tarafder AK, Barkagianni E, Seabra MC 2002 A family of Rab27-binding proteins. Melanophilin links Rab27a and myosin Va function in melanosome transport. J Biol Chem 277:25423–25430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waselle L, Coppola T, Fukuda M, Iezzi M, El-Amraoui A, Petit C, Regazzi R 2003 Involvement of the Rab27 binding protein Slac2c/MyRIP in insulin exocytosis. Mol Biol Cell 14:4103–4113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam MR, Caldwell BD, Johnson RC, Darlington DN, Mains RE, Eipper BA 1996 Novel proteins that interact with the COOH-terminal cytosolic routing determinants of an integral membrane peptide-processing enzyme. J Biol Chem 271:28636–28640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell BD, Darlington DN, Penzes P, Johnson RC, Eipper BA, Mains RE 1999 The novel kinase peptidylglycine α-amidating monooxygenase cytosolic interactor protein 2 interacts with the cytosolic routing determinants of the peptide processing enzyme peptidylglycine α-amidating monooxygenase. J Biol Chem 274:34646–34656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mains RE, Alam MR, Johnson RC, Darlington DN, Back N, Hand TA, Eipper BA 1999 Kalirin, a multifunctional PAM COOH-terminal domain interactor protein, affects cytoskeletal organization and ACTH secretion from AtT-20 cells. J Biol Chem 274:2929–2937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desnos C, Huet S, Fanget I, Chapuis C, Bottiger C, Racine V, Sibarita JB, Henry JP, Darchen F 2007 Myosin va mediates docking of secretory granules at the plasma membrane. J Neurosci 27:10636–10645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee Y, Yoo JS, Hazuka CD, Peterson KE, Hsu SC, Scheller RH 1997 Subunit structure of the mammalian exocyst complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:14438–14443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TerBush DR, Maurice T, Roth D, Novick P 1996 The exocyst is a multiprotein complex required for exocytosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J 15:6483–6494 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SC, TerBush D, Abraham M, Guo W 2004 The exocyst complex in polarized exocytosis. Int Rev Cytol 233:243–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Chiang SH, Chang L, Chen XW, Saltiel AR 2006 Compartmentalization of the exocyst complex in lipid rafts controls Glut4 vesicle tethering. Mol Biol Cell 17:2303–2311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzaki M, Pessin JE 2003 Insulin signaling: GLUT4 vesicles exit via the exocyst. Curr Biol 13:R574–R576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerges NZ, Backos DS, Rupasinghe CN, Spaller MR, Esteban JA 2006 Dual role of the exocyst in AMPA receptor targeting and insertion into the postsynaptic membrane. EMBO J 25:1623–1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sans N, Prybylowski K, Petralia RS, Chang K, Wang YX, Racca C, Vicini S, Wenthold RJ 2003 NMDA receptor trafficking through an interaction between PDZ proteins and the exocyst complex. Nat Cell Biol 5:520–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsch H, Pypaert M, Maday S, Pelletier L, Mellman I 2003 The AP-1A and AP-1B clathrin adaptor complexes define biochemically and functionally distinct membrane domains. J Cell Biol 163:351–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XW, Leto D, Chiang SH, Wang Q, Saltiel AR 2007 Activation of RalA is required for insulin-stimulated Glut4 trafficking to the plasma membrane via the exocyst and the motor protein Myo1c. Dev Cell 13:391–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez JA, Kwan EP, Xie L, He Y, James DE, Gaisano HY 2008 The RalA GTPase is a central regulator of insulin exocytosis from pancreatic islet β-cells. J Biol Chem 283:17939–17945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matteoli M, Takei K, Cameron R, Hurlbut P, Johnston PA, Sudhof TC, Jahn R, De Camilli P 1991 Association of Rab3A with synaptic vesicles at late stages of the secretory pathway. J Cell Biol 115:625–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolmachova T, Anders R, Stinchcombe J, Bossi G, Griffiths GM, Huxley C, Seabra MC 2004 A general role for Rab27a in secretory cells. Mol Biol Cell 15:332–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboi T, Fukuda M 2006 Rab3A and Rab27A cooperatively regulate the docking step of dense-core vesicle exocytosis in PC12 cells. J Cell Sci 119:2196–2203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handley MT, Haynes LP, Burgoyne RD 2007 Differential dynamics of Rab3A and Rab27A on secretory granules. J Cell Sci 120:973–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi H, Samuelson LC, Yule DI, Ernst SA, Williams JA 1997 Overexpression of Rab3D enhances regulated amylase secretion from pancreatic acini of transgenic mice. J Clin Invest 100:3044–3052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldini G, Wang G, Weber M, Zweyer M, Bareggi R, Witkin JW, Martelli AM 1998 Expression of Rab3D N135I inhibits regulated secretion of ACTH in AtT-20 cells. J Cell Biol 140:305–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabellini G, Baldini G, Baldini G, Bortul R, Bareggi R, Narducci P, Martelli AM 2001 Localization of the small monomeric GTPases Rab3D and Rab3A in the AtT-20 rat pituitary cell line. Eur J Histochem 45:347–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joberty G, Stabila PF, Coppola T, Macara IG, Regazzi R 1999 High affinity Rab3 binding is dispensable for Rabphilin-dependent potentiation of stimulated secretion. J Cell Sci 112:3579–3587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung SH, Takai Y, Holz RW 1995 Evidence that the Rab3a-binding protein, rabphilin3a, enhances regulated secretion. Studies in adrenal chromaffin cells. J Biol Chem 270:16714–16718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Okamoto M, Schmitz F, Hofmann K, Sudhof TC 1997 Rim is a putative Rab3 effector in regulating synaptic-vesicle fusion. Nature 388:593–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishida S, Shirataki H, Sasaki T, Kato M, Kaibuchi K, Takai Y 1993 Rab3A GTPase-activating protein-inhibiting activity of Rabphilin-3A, a putative Rab3A target protein. J Biol Chem 268:22259–22261 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz A, Thakur P, Junge HJ, Ashery U, Rhee JS, Scheuss V, Rosenmund C, Rettig J, Brose N 2001 Functional interaction of the active zone proteins Munc13–1 and RIM1 in synaptic vesicle priming. Neuron 30:183–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola T, Magnin-Luthi S, Perret-Menoud V, Gattesco S, Schiavo G, Regazzi R 2001 Direct interaction of the Rab3 effector RIM with Ca2+ channels, SNAP-25, and synaptotagmin. J Biol Chem 276:32756–32762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibino H, Pironkova R, Onwumere O, Vologodskaia M, Hudspeth AJ, Lesage F 2002 RIM binding proteins (RBPs) couple Rab3-interacting molecules (RIMs) to voltage-gated Ca(2+) channels. Neuron 34:411–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann N, DeProto J, Ranjan R, Wan H, Van Vactor D 2002 Drosophila liprin-α and the receptor phosphatase Dlar control synapse morphogenesis. Neuron 34:27–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Liu X, Biederer T, Sudhof TC 2002 A family of RIM-binding proteins regulated by alternative splicing: implications for the genesis of synaptic active zones. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:14464–14469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes LP, Evans GJ, Morgan A, Burgoyne RD 2001 A direct inhibitory role for the Rab3-specific effector, Noc2, in Ca2+-regulated exocytosis in neuroendocrine cells. J Biol Chem 276:9726–9732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda M, Kanno E, Saegusa C, Ogata Y, Kuroda TS 2002 Slp4-a/granuphilin-a regulates dense-core vesicle exocytosis in PC12 cells. J Biol Chem 277:39673- 39678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi Z, Yokota H, Torii S, Aoki T, Hosaka M, Zhao S, Takata K, Takeuchi T, Izumi T 2002 The Rab27a/granuphilin complex regulates the exocytosis of insulin-containing dense-core granules. Mol Cell Biol 22:1858–1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii S, Takeuchi T, Nagamatsu S, Izumi T 2004 Rab27 effector granuphilin promotes the plasma membrane targeting of insulin granules via interaction with syntaxin 1a. J Biol Chem 279:22532–22538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi T, Gomi H, Kasai K, Mizutani S, Torii S 2003 The roles of Rab27 and its effectors in the regulated secretory pathways. Cell Struct Funct 28:465–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speidel D, Salehi A, Obermueller S, Lundquist I, Brose N, Renstrom E, Rorsman P 2008 CAPS1 and CAPS2 regulate stability and recruitment of insulin granules in mouse pancreatic β cells. Cell Metab 7:57–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speidel D, Bruederle CE, Enk C, Voets T, Varoqueaux F, Reim K, Becherer U, Fornai F, Ruggieri S, Holighaus Y, Weihe E, Bruns D, Brose N, Rettig J 2005 CAPS1 regulates catecholamine loading of large dense-core vesicles. Neuron 46:75–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizo J 2006 Illuminating membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:19611–19612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen JB 2005 SNARE complexes prepare for membrane fusion. Trends Neurosci 28:453–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojilkovic SS 2005 Ca2+-regulated exocytosis and SNARE function. Trends Endocrinol Metab 16:81–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimer RM, Richmond JE 2005 Synaptic vesicle docking: a putative role for the Munc18/Sec1 protein family. Curr Top Dev Biol 65:83–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Chin LS 2003 The molecular machinery of synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Cell Mol Life Sci 60:942–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundelfinger ED, Kessels MM, Qualmann B 2003 Temporal and spatial coordination of exocytosis and endocytosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4:127–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakamper S, Meyhofer E 2006 Back on track—on the role of the microtubule for kinesin motility and cellular function. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 27:161–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Roth D, Walch-Solimena C, Novick P 1999 The exocyst is an effector for Sec4p, targeting secretory vesicles to sites of exocytosis. EMBO J 18:1071–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroer TA 2004 Dynactin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 20:759–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuka T, Takao-Rikitsu E, Inoue E, Inoue M, Takeuchi M, Matsubara K, Deguchi-Tawarada M, Satoh K, Morimoto K, Nakanishi H, Takai Y 2002 Cast: a novel protein of the cytomatrix at the active zone of synapses that forms a ternary complex with RIM1 and munc13-1. J Cell Biol 158:577–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch S, Castillo PE, Jo T, Mukherjee K, Geppert M, Wang Y, Schmitz F, Malenka RC, Sudhof TC 2002 RIM1α forms a protein scaffold for regulating neurotransmitter release at the active zone. Nature 415:321–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross SP 2004 Hither and yon: a review of bi-directional microtubule-based transport. Phys Biol 1:R1–R11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kural C, Kim H, Syed S, Goshima G, Gelfand VI, Selvin PR 2005 Kinesin and dynein move a peroxisome in vivo: a tug-of-war or coordinated movement? Science 308:1469–1472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali MY, Lu H, Bookwalter CS, Warshaw DM, Trybus KM 2008 Myosin V and Kinesin act as tethers to enhance each others’ processivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:4691–4696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier-Larsen E, Holzbaur EL 2006 Axonal transport and neurodegenerative disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1762:1094–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munch C, Sedlmeier R, Meyer T, Homberg V, Sperfeld AD, Kurt A, Prudlo J, Peraus G, Hanemann CO, Stumm G, Ludolph AC 2004 Point mutations of the p150 subunit of dynactin (DCTN1) gene in ALS. Neurology 63:724–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puls I, Jonnakuty C, LaMonte BH, Holzbaur EL, Tokito M, Mann E, Floeter MK, Bidus K, Drayna D, Oh SJ, Brown Jr RH, Ludlow CL, Fischbeck KH 2003 Mutant dynactin in motor neuron disease. Nat Genet 33:455–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid E, Kloos M, Ashley-Koch A, Hughes L, Bevan S, Svenson IK, Graham FL, Gaskell PC, Dearlove A, Pericak-Vance MA, Rubinsztein DC, Marchuk DA 2002 A kinesin heavy chain (KIF5A) mutation in hereditary spastic paraplegia (SPG10). Am J Hum Genet 71:1189–1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Takita J, Tanaka Y, Setou M, Nakagawa T, Takeda S, Yang HW, Terada S, Nakata T, Takei Y, Saito M, Tsuji S, Hayashi Y, Hirokawa N 2001 Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A caused by mutation in a microtubule motor KIF1Bβ. Cell 105:587–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]