Abstract

Smoking cessation interventions often target expectancies about the consequences of smoking. Yet little is known about the way smoking-related expectancies vary across different contexts. Two internal contexts that are often linked with smoking relapse are states associated with smoking abstinence and alcohol consumption. This report presents a secondary analysis of data from two experiments designed to examine the influence of smoking abstinence, and smoking abstinence combined with alcohol consumption, on smoking-related outcome expectancies among heavy smokers and tobacco chippers (smokers who had consistently smoked no more than 5 cigarettes/day for at least 2 years). Across both experiments, smoking abstinence and alcohol consumption increased expectancies of positive reinforcement from smoking. In addition, alcohol consumption increased negative reinforcement expectancies among tobacco chippers, such that the expectancies became more similar to those of heavy smokers as tobacco chippers’ level of subjective alcohol intoxication increased. Findings suggest that these altered states influence the way smokers evaluate the consequences of smoking, and provide insight into the link between smoking abstinence, alcohol consumption, and smoking behavior.

Introduction

Individuals form expectancies about the effects of smoking cigarettes that are associated with the initiation, maintenance, and cessation of smoking behavior (Andrews & Duncan, 1998; Brandon, Juliano, & Copeland, 1999). Accordingly, treatment guidelines and prominent theories of health behavior change indicate that challenging current smokers’ expectancies regarding the costs and benefits of smoking is an effective way to promote cessation (Fiore et al., 2000; Weinstein, 1993). The challenge for treatment providers and researchers is that smokers are often resistant to messages encouraging cessation, and smoking-related outcome expectancies are only modestly associated with subsequent smoking cessation (e.g., Hyland, Bauer, Giovino, Steger, & Cummings, 2004\).

Researchers interested in the association between smoking-related expectancies and behavior typically assess expectancies at one time point and use these responses to predict subsequent changes in behavior (Brewer, Weinstein, Cuite, & Herrington, 2004; Godin, Valois, Lepage, & Desharnais, 1992; Norman, Conner, & Bell, 1999). The assumption underlying this approach is that individual differences in smoking expectancies are relatively stable. Empirical evidence and prominent models of addictive behavior indicate, however, that this assumption is often inappropriate, because the association between smoking-related cognition and behavior varies across both internal states and external contexts (e.g., Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004; Gwaltney, Shiffman, & Sayette, 2005; Marlatt & Gordon, 1985). Because expectancies are usually assessed in neutral states, they may not correspond well with actual behavior. It therefore would be useful to account for the moderating influence of situational variables on the link between smoking-related outcome expectancies and subsequent smoking behavior (Sayette, 2004; Tennen, Affleck, & Armeli, 2003).

Among addictive health-risk behaviors, like cigarette smoking, it may be especially important to account for the influence of motivational states associated with drug deprivation (Baker, Brandon, & Chassin, 2004). Once tobacco dependence is established, smoking behavior appears to be influenced by withdrawal symptoms and drug craving. Several recent reports indicate that cigarette craving is among the best predictors of both regular smoking behavior and relapse (e.g., Killen & Fortmann, 1997; Shapiro, Jamner, Davydov, & James, 2002; Shiffman, Paty, Gwaltney, & Dang, 2004). Thus, one reason expectancies do not correspond with subsequent smoking behavior may be that smoking-related decision making often occurs while smokers are experiencing an immediate desire, or craving, to smoke. Craving may promote drug use by altering the way smokers process smoking-related information and make decisions regarding continued use (Sayette, 2004). For instance, craving has been found to increase generation of positive smoking-related information from memory (Sayette & Hufford, 1997).

Because smoking relapse is strongly associated with alcohol consumption, it also would be useful to assess the combined influence of smoking abstinence and alcohol consumption on smoking-related outcome expectancies (Shiffman & Balabanis, 1995). Data from field studies using ecological momentary assessment methods indicate that, among abstinent smokers, smoking lapses are associated more strongly with alcohol consumption than with other situational variables (e.g., Shiffman, Fischer et al., 1994). Moreover, smoking abstinence has been observed to increase the accessibility of smokers’ alcohol-related outcome expectancies, urges to drink, and the volume of alcohol consumed (Palfai, Monti, Ostafin, & Hutchison, 2000).

The present study reports findings from two experiments designed to examine the effect of smoking abstinence (Experiment 1), and smoking abstinence combined with alcohol consumption (Experiment 2), on smoking-related outcome expectancies among heavy smokers (HS) and tobacco chippers (TC; smokers who had consistently smoked no more than 5 cigarettes/day for at least 2 years). This work expands on initial expectancy findings we reported elsewhere (Sayette, Martin, Wertz, Perrott, & Peters, 2005; Sayette, Martin, Wertz, Shiffman, & Perrott, 2001). In each of these prior studies, smoking expectancy data were reported in the context of a multidimensional assessment. Results were limited to examining whether smoking abstinence and alcohol consumption manipulations affected the relative weighting of positive versus negative outcomes. Results indicated that smoking abstinence and smoker type, but not alcohol consumption, affected smokers’ evaluation of smoking consequences. A key limitation of this work was that it focused on difference scores, calculated by subtracting the mean probability value of negative from positive outcome expectancies. Thus it is unclear whether smoking abstinence alone and in combination with alcohol consumption increased positive outcome expectancies, decreased negative outcome expectancies, or both.

In addition to separately examining positive versus negative outcome expectancies, an aim of the present research was to study the effects of smoking abstinence and alcohol consumption on specific types of positive (i.e., reinforcement) expectancies. Discriminating between positive and negative reinforcement expectancies is thought to convey additional information about the reasons people choose to smoke, specifying whether they value the ability of smoking to enhance positive affect or to provide relief from negative affect (Goldman, Del Boca, & Darkes, 1999). A fine-grained examination of reinforcement expectancies also may help to distinguish between subgroups of smokers. For instance, HSs may be more likely than TCs to smoke for negative reinforcement (Shiffman, Paty, Gnys, Kassel, & Elash, 1995). Consequently, an aim of the present research was to contrast smoking expectancies held by HSs with those of TCs.

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 sought to examine the effects of smoking abstinence on HSs’ and TCs’ positive and negative smoking-related outcome expectancies, as well as their expectancies of positive and negative reinforcement. We hypothesized that, compared with nonabstinent smokers, abstinent smokers would rate both positive and negative reinforcement outcomes as more probable, while rating negative consequences as less probable. In addition, we expected an interaction between smoking abstinence and type of smoker, such that compared with TCs, HSs would be more sensitive to smoking abstinence and therefore rate both positive and negative reinforcement outcomes as being more probable, while rating negative consequences as less probable.

Method

Participants

Smokers (N=126; 60 men and 66 women) aged 21–35 years were recruited through advertisements in local newspapers and on radio programs. Exclusion criteria included illiteracy and medical conditions that ethically contraindicated nicotine administration. TCs (n=62) had to report smoking 5 or fewer cigarettes on any day of the week for at least 24 continuous months, whereas HSs (n=64) had to report smoking an average of 21 cigarettes/day or more for at least 24 continuous months (Shiffman, Paty, Kassel, Gnys, & Zettler-Segal, 1994). Abstinent HS and nonabstinent TC had to have carbon monoxide (CO) levels that did not exceed 16 ppm and 10 ppm, respectively. Age (M=24.7 years, SD=4.2), years of formal education (M=14.4, SD=1.8), and ethnic background (77% White, 17% Black, and 6% Hispanic or Asian American) did not differ significantly for the two types of smokers (p-values>.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by smoker type and treatment condition.

| Tobacco chippers | Heavy smokers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 (N=126) | Nonabstinent | Abstinent | Nonabstinent | Abstinent |

| Years smoking | 7.5 (4.1) | 6.0 (4.5) | 8.9 (5.3) | 9.2 (4.9) |

| Cigarettes per day | 4.3 (2.0) | 3.6 (1.5) | 24.8 (5.5) | 25.2 (5.3) |

| FTQ score | 6.3 (2.3) | 6.5 (2.1) | 6.3 (1.9) | 6.7 (1.6) |

| CO (ppm) | 7.3 (5.8) | 3.9 (2.3) | 27.7 (10.5) | 9.3 (3.7) |

| Urge pre SCQ-B | 27.1 (24.4) | 44.2 (32.3) | 32.7 (24.3) | 69.5 (23.1) |

| Experiment 2 (N=137) | Placebo | Alcohol | Placebo | Alcohol |

|

| ||||

| Years smoking | 5.5 (3.3) | 4.6 (2.6) | 8.0 (5.0) | 8.0 (3.4) |

| Cigarettes per day | 3.8 (1.6) | 3.9 (1.2) | 23.9 (4.1) | 24.3 (5.6) |

| FTQ score | 3.5 (2.6) | 4.0 (2.9) | 4.1 (3.0) | 3.4 (2.9) |

| CO (ppm) | 5.6 (5.8) | 5.9 (3.6) | 13.3 (4.6) | 12.6 (4.9) |

| Urge pre SCQ-B | 44.2 (27.5) | 53.4 (29.9) | 71.9 (24.3) | 77.5 (24.1) |

| SIS pre SCQ-B | 13.1 (12.9) | 40.1 (22.3) | 9.1 (8.9) | 32.8 (18.1) |

| BAC pre SCQ-B | — | .059 (.026) | — | .065 (.026) |

| BAC post SCQ-B | — | .066 (.022) | — | .069 (.018) |

Note. Values are means with standard deviations for smoking patterns, nicotine dependence (Fagerström Tobacco Questionnaire, FTQ), carbon monoxide (CO) level at outset of study. Urge to smoke (Urge), Subjective Intoxication Scale (SIS) score, and blood alcohol concentration (BAC) as recorded prior to completion of the Smoking Consequences Questionnaire-Brief (SCQ-B). All participants in Experiment 2 were 12-hr nicotine deprived.

Individual difference measures

To assess individual differences that may influence responses, we obtained data on age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education, and income. Also assessed with standard forms were smoking history and patterns, and current interest in quitting (Sayette et al., 2001).

Smoking abstinence response measures

Reported urge to smoke

Urge to smoke was assessed using a single-item urge rating scale ranging from 0 (absolutely no urge to smoke at all) to 100 (strongest urge to smoke I’ve ever experienced). A single-item scale was chosen to minimize reactivity, which is of concern when a measure is administered multiple times (Juliano & Brandon, 1998; Sayette et al., 2000).

Smoking Consequences Questionnaire-Brief (SCQ-B)

The SCQ-B is an abbreviated version of the SCQ (Copeland, Brandon, & Quinn, 1995). The SCQ-B includes 24 items from the Copeland et al. scale, 22 of which were analyzed in each of the present studies (for list of items, see Sayette, Martin, Hull, Wertz, & Perrott, 2003). Two weight-related items that did not correlate with the primary scales were excluded. For each item, participants rated on a 10-point scale the probability that they believed this consequence would occur (Copeland et al., 1995). Scale reliability was assessed by calculating coefficient alpha (Cronbach, 1951).

SCQ-B positive outcome expectancies

Positive outcome expectancies include expectancies of both positive and negative reinforcement. A total of 12 items were used to assess positive outcome expectancies, 6 of which were designed to assess positive reinforcement expectancies, and 6 designed to assess negative reinforcement expectancies. An example of a positive reinforcement item was “Cigarettes can really make me feel good,” and an example of a negative reinforcement item was “Smoking calms me down when I feel nervous.” Overall, coefficient alpha reliability was estimated as .84 for the 12 positive items, .69 for the 6-item positive reinforcement scale, and .82 for the 6-item negative reinforcement scale, indicating an adequate level of internal consistency in all scales assessing positive outcome expectancies.

SCQ-B negative outcome expectancies

A total of 10 items assessed negative outcome expectancies. Coefficient alpha reliability was estimated as .84 for these items, indicating an adequate degree of internal consistency. Seven of the items were designed to assess health-related consequences of smoking (α=.81), whereas the remaining three were designed to assess social consequences (α=.76). An example of a health-related item was “Smoking is taking years off my life,” and an example of a negative social item was “Smoking makes me seem less attractive.”

Procedure

Telephone screening and instructions

Participants who responded to advertisements underwent a telephone interview designed to exclude those not meeting selection criteria. Eligible smokers were asked to attend a 2-hr laboratory session. Those assigned to the smoking abstinence conditions were instructed to refrain from smoking for at least 7 hr and were told that breath samples would be recorded to ensure that they had abstained.

Baseline assessment

Experimental sessions began between 3:00 P.M. and 5:00 P.M. Written informed consent was obtained from participants on arrival. To check compliance with abstinence instructions, participants reported the last time they smoked, and a CO reading (no. 1) was recorded. They next completed a baseline assessment, including urge to smoke (no. 1). At this time, all nondeprived participants smoked a cigarette. During this 5-min interval, abstinent participants sat quietly. Participants then provided CO no. 2 and rated their urge to smoke (no. 2).

Cue exposure

All participants were exposed to smoking cues (participants’ own cigarettes). At the beginning of a control cue-exposure sequence (not relevant to examination of SCQ-B), a tray holding an inverted plastic bowl was placed on the desk. Participants were instructed to lift the bowl, which revealed a roll of tape. After picking up the tape in their dominant hand, participants were asked to rate their urge to smoke (rating no. 3). Two minutes later, the experimenter replaced the first tray and bowl with a second tray and bowl, and participants provided another urge rating (no. 4). Participants then lifted the bowl, which revealed their pack of cigarettes, an ashtray, and a lighter. They were instructed to remove one cigarette from the pack and light it without putting it in their mouth. They then held the cigarette while providing urge rating no. 5 and then extinguished the cigarette. Finally, participants completed the SCQ-B. (Additional details about the cue-exposure procedure are reported in Sayette et al., 2001.)

Data analyses

Experiment 1 used a mixed factorial design, with HS and TC randomly assigned to 7-hr smoking abstinence or nonabstinence conditions. First, a series of analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted to test main and interaction effects for abstinence, smoker type, and gender. Hypotheses stem from our assumption that the abstinence manipulation increases urge to smoke. To verify this assumption, in the second stage of our analyses we conducted a series of mediational analyses to determine whether urge mediated any observed effects. In the event that significant interaction effects were observed, the nature and magnitude of these effects were assessed with the simple slope methods outlined by Aiken and West (1991) for interpreting significant interaction effects.

Results

Smoking abstinence manipulation check

As expected, and reported previously (Sayette et al., 2001), HSs reported higher urges than TCs. In addition, abstinent smokers reported higher urges than nonabstinent smokers, and a significant smoker type × abstinence interaction was observed, indicating that abstinent HSs reported significantly higher urges than did the other three groups.

Positive versus negative outcome expectancies

In an initial step, we tested the main and interaction effects of smoker type (HS vs. TC) and smoking abstinence (abstinent vs. nonabstinent) on the positive and negative outcome expectancy scales. A series of smoker type × abstinence ANOVAs revealed main effects of smoker type and smoking abstinence on positive outcome expectancies, with HS evaluating the likelihood of positive consequences to be more probable (M=5.8, SD=1.4) than did TC (M=4.8, SD=1.7), F(1, 124)= 13.2, p<.0005, and abstinent smokers evaluating the likelihood of positive smoking consequences to be more probable (M=5.7, SD=1.5) than did nonabstinent smokers (M=5.0, SD=1.7), F(1, 124)= 5.2, p<.03. The analyses indicated no main effects of smoker type or smoking abstinence on negative outcome expectancies, Fs (1, 124)< 1, and no smoker type × abstinence interaction for either positive or negative outcome expectancies. These latter findings extended to both the health-risk and social consequences subscales, Fs (1, 124)< 1. We also examined the main and interaction effects of gender on the positive and negative outcome expectancy scales. These analyses found that gender had no main effect on any of the expectancy scales, Fs (1, 124)< 1, and that gender did not moderate the observed effects of either smoking abstinence, Fs (1, 122)< 2, or smoker type, Fs (1, 122)< 1.

Positive versus negative reinforcement expectancies

To further assess the effects of smoking abstinence on participants’ expectancies of positive smoking consequences, we conducted separate analyses of the effects of smoker type and smoking abstinence on the positive reinforcement and negative reinforcement subscales. These analyses revealed main effects of smoker type on expectancies of positive reinforcement, F(1, 124)= 4.6, p<.03, and on negative reinforcement, F(1, 124)= 17.1, p<.001, with HSs judging the probability of positive reinforcement (M=4.8, SD=1.7) to be greater than did TCs (M=4.1, SD=1.8), and HSs judging the probability of negative reinforcement (M=6.9, SD=1.5) to be greater than did TCs (M=5.5, SD=2.0). A significant main effect of smoking abstinence on expectancies of positive reinforcement also emerged, F(1, 124)= 5.7, p<.01, with abstinent smokers evaluating the likelihood of positive reinforcement to be more probable (M=4.8, SD=1.7) than did nonabstinent smokers (M=4.0, SD=1.8). However, smoking abstinence did not significantly affect negative reinforcement, F(1, 124)< 2.7, p>.1, and the smoker type × abstinence interaction was not significant for either positive or negative reinforcement expectancies. Likewise, analyses found that gender had main effect on the reinforcement scales, Fs (1, 124)< 1, and that gender did not moderate the observed effects of either smoking abstinence, Fs (1, 122)< 2.4, or smoker type, Fs (1, 122)< 1.

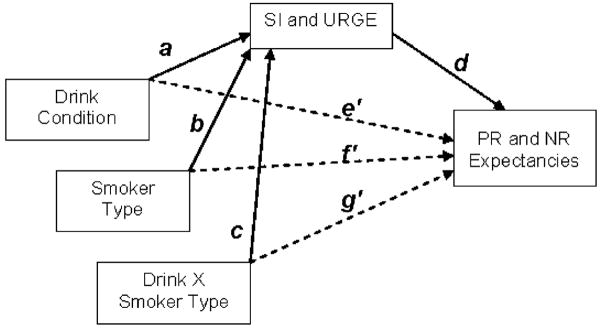

Reported urge to smoke and smoking-related expectancies

To determine whether the observed effects of our smoking abstinence (and cue-exposure) manipulation were mediated by increases in participants’ urge to smoke, we conducted a series of hierarchical regression analyses designed to assess the indirect influence of abstinence on participants’ expectancies through urge (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Preacher & Hayes, 2004). The first step of these analyses indicated that with postcue urge to smoke entered as a covariate, smoking abstinence was no longer a significant predictor of overall positive outcome expectancies, β=.32, p>.31, or positive reinforcement expectancies, β=.35, p>.29 (Figure 1). Step 2 indicated that smoking abstinence remained a significant predictor of urge to smoke, β=2.25, p<.001, and that urge was a significant predictor of both positive outcome expectancies, β=.15, p<.02, and positive reinforcement expectancies, β=.17, p<.007. Finally, results of Sobel’s test indicated that the indirect path from smoking abstinence to expectancies through urge was significant for both positive outcome expectancies, Z=1.99, p<.05, and positive reinforcement expectancies, Z=2.13, p<.05. Thus urge to smoke mediated the observed associations between smoking abstinence and participants’ smoking-related positive outcome expectancies.

Figure 1.

Mediation of the relationship between smoking abstinence and positive reinforcement (PR) expectancies by urge to smoke (URGE). β′=direct effect controlling for URGE. *p<.02; **p-values<.007.

Discussion

Findings of Experiment 1 indicate that smoking abstinence influenced smokers’ positive outcome expectancies but did not affect smokers’ negative outcome expectancies. More specifically, results indicate that the effects of abstinence on positive expectancies primarily reflect increased expectancies of positive reinforcement. Smoking abstinence did not significantly affect negative reinforcement expectancies, though the mean differences were in the expected direction. Results also revealed differences between HS and TC, yet we found no significant effects of gender, and the expected interaction between smoker type and smoking abstinence did not emerge.

Smoking abstinence, smoker type, and gender did not influence smokers’ negative outcome expectancies. These null findings suggest that, among both HS and TC, negative outcome expectancies may be resistant to change. Although speculative, one explanation for this finding is that this was a relatively young sample not currently interested in quitting, for whom the negative consequences of smoking may not be an immediate concern. Thus, although all participants were willing to acknowledge the negative consequences of smoking, they may not have considered these consequences to be especially worrisome, and therefore would have no reason to lower them while in an abstinent state.

In sum, Experiment 1 supported the hypothesis that smoking expectancies, rather than being stable traits, are instead subject to fluctuations associated with situational contexts. Specifically, abstinent smokers viewed positive reinforcing consequences of smoking to be more likely to occur than did nonabstinent smokers. Because abstinent smokers often lapse while drinking alcohol (Shiffman, Fischer et al., 1994), we next examined the effects of alcohol consumption combined with smoking abstinence on smoking-related expectancies.

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 tested whether alcohol would magnify the effects of smoking abstinence on smoking-related outcome expectancies. We used a mixed factorial design, with 12-hr smoking-abstinent HS and TC randomly assigned to receive either alcohol (n=68) or placebo (n=69). Smoking cue exposure was conducted using the same methods as in Experiment 1. Additional methodological information regarding participants, measures, and procedures is outlined below and described in greater detail elsewhere (Sayette et al., 2005).

Several models bid to explain how alcohol may interact with smoking abstinence to influence risk-related probability judgments. Most of these models posit that alcohol disrupts executive cognitive processes, thereby reducing a drinker’s ability to consider delayed negative consequences relative to proximal rewards (e.g., Sayette, 1993; Steele & Josephs, 1990). These models suggest that alcohol should have a direct effect on smoking-related expectancies that is independent of smokers’ level of motivation to smoke. From this perspective, alcohol consumption would be expected to decrease the salience of negative smoking-related consequences regardless of smoking abstinence. Alternatively, the effects of alcohol on smokers’ expectancies may be mediated by their urge to smoke, such that smoking expectancies shift as alcohol consumption increases smokers’ smoking urge. Evidence indicates that alcohol consumption increases subjective smoking urge (Burton & Tiffany, 1997; King & Epstein, 2005; Sayette et al., 2005), but it is unclear whether alcohol consumption has an additive effect on expectancies that is independent of urge. A primary aim of Experiment 2 was to evaluate these alternative perspectives regarding the combined influence of smoking abstinence and alcohol consumption on smoking-related outcome expectancies.

We hypothesized that alcohol ingestion would moderate the effects of smoking abstinence, such that smokers who drank alcohol would rate positive consequences, including both positive and negative reinforcement outcomes, as being more probable, and negative consequences as less probable than would those who drank placebo. Because smoking patterns are more context dependent for TCs than for HSs, we also expected an interaction between alcohol consumption and smoker type, such that expectancies among TCs would be affected by alcohol versus placebo consumption more than would expectancies among HSs. We predicted alcohol consumption would increase positive expectancies and decrease negative expectancies relative to placebo among TCs, whereas expectancies among HSs would remain stable across the drink conditions.

Method

Participants

Smokers (N=137; 68 men and 69 women) aged 21–35 years were recruited via newspaper and radio advertisements (Table 1). Some 82% of the sample identified themselves as White, 11% as Black, and 7% as Hispanic or Asian American. Tobacco chippers (n=68) had to report smoking at least two days per week, and on smoking days they had to average one to five cigarettes. Heavy smokers (n=69) had to average 20–40 cigarettes/day. Both TC and HS had to report smoking at these rates for at least 24 continuous months. Potential participants were excluded if they reported a history of adverse reaction to the type or amount of beverage to be used in the study or medical conditions that contraindicate alcohol administration, if they met DSM-IV criteria for past alcohol abuse or dependence, or if they were illiterate. All participants provided informed consent. Heavy smokers and TCs had to have an initial CO level that did not exceed 20 ppm and 15 ppm, respectively. Smoker type × drink analyses revealed no differences on income, marital status, age, ethnic background, or current drinking patterns, although HS received fewer years of formal education and reported fewer previous quit attempts than did TCs, Fs (1, 135)> 4.6, p values<.04. A research assistant tossed a coin to randomly assign participants to each experimental condition.

Individual difference measures

Data on age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, and income, as well as smoking history, current patterns, and interest in quitting, were obtained with the same forms used in Experiment 1.

Reported urge to smoke

Participants’ urge to smoke was assessed using the single-item urge rating scale (ranging from 0 to 100) utilized in Experiment 1.

Smoking Consequences Questionnaire-Brief (SCQ-B)

As in Experiment 1, participants completed the SCQ-B, and coefficient alpha estimates indicated an adequate level of internal consistency in all scales. Coefficient alpha reliability estimates were .78 for the 12 positive items, .69 for the 6-item positive reinforcement scale, and .78 for the 6-item negative reinforcement scale. Coefficient alpha reliability estimates were .81 for the 10 negative items, .75 for the health-related consequences of smoking scale, and .77 for the social consequences scale.

Alcohol-related measures

Blood alcohol concentration

Blood alcohol concentrations (BACs) were recorded using a DataMaster breath alcohol instrument (National Patent Analytical Systems, Mansfield, Ohio). The Data-Master calibrates infrared measurement systems prior to each test with an accuracy of ±0.003% at a BAC of .1%. The DataMaster was custom designed for false BAC display in the placebo conditions.

Subjective intoxication scale

Participants estimated their perceived intoxication level with the Subjective Intoxication Scale (SIS). They were asked to respond using a scale from 0 to 100, where 0= “not intoxicated at all” and 100= “the most intoxicated I have ever been.”

Procedure

Baseline assessment

Informed consent was obtained from participants on their arrival, and participants’ height and weight were recorded. Participants were then asked to report their urge to smoke (no. 1). Next, to test sobriety and to check compliance with abstinence instructions, participants reported the last time they smoked and drank, and baseline CO and BAC readings were recorded. Finally, participants were asked to rate their subjective intoxication using the SIS (the SIS was always administered during BAC assessment) and to again rate their urge to smoke (no. 2).

Drink administration

Drinks were administered in the early afternoon, over a 30-min period between 1:00 P.M. and 2:00 P.M. After participants consumed a weight-adjusted snack (a bagel with butter), drinks were mixed in front of participants to increase credibility in the placebo conditions (Rohsenow & Marlatt, 1981). The alcoholic beverage was one part vodka and 3.5 parts cranberry juice. For those drinking alcohol, the vodka bottle contained 100-proof vodka (Smirnoffs); for those administered a placebo, the vodka bottle contained flattened tonic water. Prior work has revealed that this procedure provides a successful placebo manipulation, the goal of which was to lead participants to believe they had drunk alcohol (Martin & Sayette, 1993).

Beginning at time zero, participants in the alcohol condition were administered one-third of a 0.82 g/kg dose of alcohol and asked to drink it evenly over a 10-min period. At 10- and 20-min, participants received the middle and final thirds of the beverage, respectively, and were asked to drink them evenly over the 10-min intervals. After the final third was finished (30 min), participants were asked to rinse their mouth with water, and postdrink BAC and SIS levels were assessed.

Cue exposure and BAC assessment

Cue exposure was conducted using the same methods employed in Experiment 1. As before, participants were asked to rate their urge to smoke during control cue exposure (rating no. 3), about 2 min after control cue exposure (no. 4), and during smoking cue exposure (no. 5). Next, participants completed the SCQ-B. Post-SCQ-B BAC and SIS levels were then assessed, followed by a behavioral choice task described by Sayette et al. (2005). BAC readings indicate that SCQ-B responses were obtained while participants were on the ascending limb of the BAC curve (see BAC values in Table 1).

Additional BAC and SIS ratings were recorded about 60 min after the start of drink administration for all participants. BACs were recorded at 10-min intervals until participants recorded three consecutively decreasing BACs. When BACs fell below .04%, participants completed a postexperimental questionnaire asking them to describe the study’s purpose, estimate their alcohol intake (in ounces), and use the SIS to estimate their peak level of intoxication over the course of the experiment. Participants were then debriefed, and when BACs dropped below .025%, they were paid US$80.00 and allowed to leave.

Data analyses

Experiment 2 used a mixed factorial design, with 12-hr smoking-abstinent HSs and TCs randomly assigned to receive either alcohol (n=68) or placebo (n=69). A series of ANOVAs were conducted to test main and interaction effects for alcohol consumption, smoker type, and gender. We expected observed effects of alcohol consumption to be driven by participants’ subjective level of alcohol intoxication. To test this assumption, in the second step of our analyses we conducted a series of mediational analyses to determine whether SIS ratings or urge to smoke mediated observed effects. In a final step, we interpreted observed interaction effects with the simple slope methods outlined by Aiken and West (1991).

Results

Beverage manipulation check

As noted in Sayette et al. (2005), participants consuming alcohol reached mean BACs of .071% (SD=.013) following smoking cue exposure, and .073% (SD=.012) after smoking. Placebo participants reported lower levels of intoxication on the post-drink SIS (M=11.0, SD=11.2) than did those drinking alcohol (M=36.4, SD=20.5), F(1, 135)= 81.3, p<.0001, and all participants reported drinking at least some vodka. Participants consuming alcohol reported a higher overall level of intoxication during the study (M=56.6, SD=22.5) compared with placebo participants (M=21.1, SD=16.6). In sum, as in prior studies, the placebo manipulation was successful in leading participants to believe they had consumed alcohol and to experience some degree of intoxication (for review, see Martin & Sayette, 1993).

Positive versus negative outcome expectancies

We first examined the main and interaction effects of smoker type (HS vs. TC) and drink (alcohol versus placebo) on the positive and negative outcome expectancy scales of the SCQ-B. A series of smoker type × drink ANOVAs revealed a main effect of smoker type on positive outcome expectancies, but not negative outcome expectancies, with HSs evaluating the likelihood of positive consequences as being more probable (M=5.9, SD=1.2) than did TC (M=4.9, SD=1.5), F(1, 135)= 17.5, p<.001. The analyses also revealed significant main effects of alcohol consumption on both positive and negative outcome expectancies. As expected, those consuming alcohol evaluated the likelihood of positive consequences from smoking as being more probable (M=5.7, SD=1.3) than did those consuming placebo (M=5.1, SD=1.5), F(1, 135)= 4.8, p<.03. Contrary to predictions, those consuming alcohol also evaluated the likelihood of negative consequences as more probable (M=4.4, SD=2.4) than did those consuming placebo (M=3.7, SD=2.2), F(1, 135)= 3.9, p<.05. Follow-up analyses indicated that this effect was driven by the effects of alcohol on expectancies of negative social consequences of smoking, F(1, 135)= 4.5, p<.04, with no significant effect on negative health-related consequences, F(1, 135)< 1.9. We also examined the main and interaction effects of gender on the positive and negative outcome expectancy scales. These analyses indicated that gender had no main effect on any of the expectancy scales, Fs (1, 135)< 1, and that gender did not moderate the observed effects of either alcohol consumption, Fs (1, 133)< 1, or smoker type, Fs (1, 133)< 1. No other effects were significant.

Positive versus negative reinforcement expectancies

To further assess the effects of alcohol consumption on participants’ expectancies of positive smoking consequences, we examined responses to both the positive and negative reinforcement scales. A series of smoker type × drink ANOVAs revealed main effects of smoker type on expectancies of positive and negative reinforcement, Fs (1, 135)> 7.8, p-values<.005, with HSs judging both to be more probable (M=4.9, SD=1.5) than did TCs (M=4.1, SD=1.7). Alcohol consumption had a significant main effect on expectancies of positive reinforcement, F(1, 135)= 5.1, p<.03, but not negative reinforcement, F(1, 135)< 2.2, with those consuming alcohol evaluating the likelihood of positive reinforcement as being more probable (M=4.9, SD=1.7) than did those consuming placebo (M=4.2, SD=1.6). In addition, a significant smoker type × drink interaction emerged, F(1, 133)= 4.5, p<.04, indicating that alcohol differentially affected negative reinforcement expectancies among HSs and TCs. Post-hoc contrasts revealed that alcohol consumption had a selective effect on TCs, such that TCs who consumed alcohol reported significantly greater negative reinforcement expectancies (M=6.1, SD=1.5) than did those who consumed placebo (M=5.1, SD=1.9), whereas negative reinforcement expectancies among HSs remained high (M=6.8, SD=1.3) regardless of drink content. As before, analyses indicated that gender had no main effect on the reinforcement scales, Fs (1, 135)< 1, and that gender did not moderate the observed effects of either alcohol consumption, Fs (1, 133)< 1, or smoker type, Fs (1, 133)< 1.

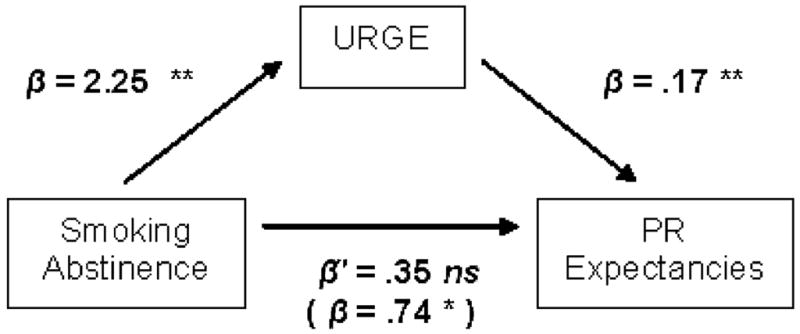

Reported urge to smoke, subjective intoxication, and smoking-related expectancies

To determine whether the observed effects of our drink manipulation were driven by increases in participants’ subjective level of alcohol intoxication or their urge to smoke, we conducted a series of mediational analyses (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). Figure 2 presents a path diagram that corresponds to each of the analyses described below. Step 1 indicated that with post-cue subjective intoxication and post-cue urge to smoke entered as covariates, alcohol was no longer a significant predictor of overall positive outcome expectancies, β=.09, p>.72, positive reinforcement expectancies, β=.19, p>.58, or negative social expectancies, β=.73, p>.14 (Figure 2, path e′). Step 2 indicated that alcohol consumption remained a significant predictor of subjective intoxication (path a), β=2.99, p<.00, but only a marginal predictor of urge to smoke, β=.81, p<.06. Step 3 indicated that although subjective intoxication remained a significant predictor of positive outcome expectancies (path d), β=.12, p<.05, and positive reinforcement expectancies, β=.15, p<.04, subjective intoxication was no longer associated with negative social consequences, β=.05, p>.63. Although urge to smoke remained a significant predictor of positive outcome expectancies (path d), β=.11, p<.03, urge was not associated with positive reinforcement expectancies, β=.00, p>.90, or negative social consequences, β=.06, p>.38.

Figure 2.

Path diagram illustrating mediation and mediated moderation of the relationship between drink condition, smoker type, and reinforcement expectancies by subjective intoxication (SI) and urge to smoke (URGE). Paths a, b, c, and d=indirect effects through SI and URGE. Paths e′, f′, g′=direct effects controlling for SI and URGE.

Results of Sobel’s test confirmed this pattern of results, indicating that the indirect path from alcohol consumption to expectancies (paths a and d) through subjective intoxication was significant for positive outcome expectancies, Z=1.97, p<.05, and positive reinforcement expectancies, Z=2.11, p<.05, but not negative social consequences, Z<.45. The indirect path associated with urge (paths a and d) was nonsignificant for positive outcome expectancies, Z=1.45, p<.12, positive reinforcement expectancies, Z<.20, and negative social consequences, Z<.30. Thus, although a trend suggests that urge to smoke partially mediated the effects of alcohol consumption on positive outcome expectancies, findings indicate that only subjective intoxication fully mediated the observed associations between alcohol consumption and participants’ positive expectancies related to smoking.

We next conducted a mediated moderation analysis to determine whether subjective intoxication or urge to smoke mediated the observed interaction effect between drink condition and smoker type on expectancies of negative reinforcement. Consistent with the mediational analyses for main effects, this analysis indicated that the interaction term was no longer a significant predictor of negative reinforcement when subjective intoxication and urge to smoker were entered in the model (Figure 2, path g′). Although the unique indirect effect of subjective intoxication remained significant (paths c and d), Z=1.79, p<.07, the unique effect of urge to smoke was nonsignificant, Z<.25, confirming that subjective intoxication mediated the interaction between alcohol and smoker type on negative reinforcement expectancies.

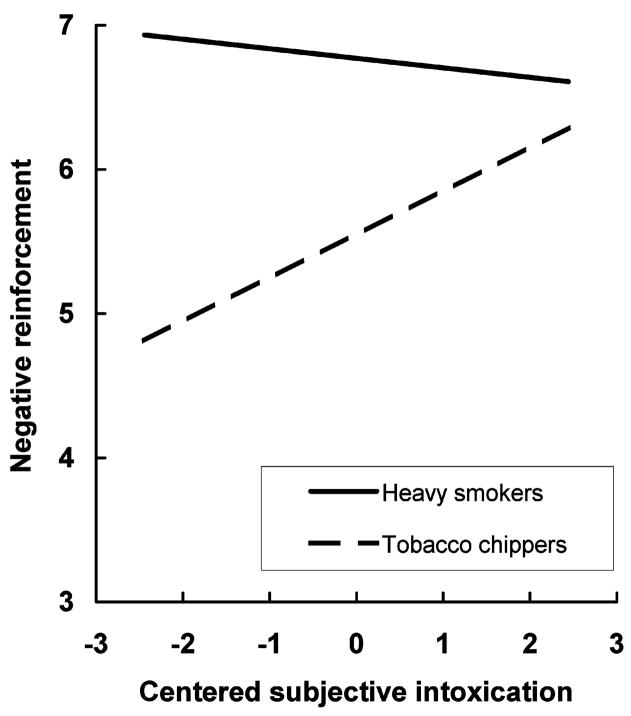

Finally, participants’ subjective intoxication ratings were used to interpret the significant interaction between alcohol consumption and smoker type on negative reinforcement expectancies. Procedures outlined by Aiken and West (1991) for interpreting interactions between one continuous variable (subjective intoxication) and one categorical variable (smoker type) were used. Subjective intoxication scores were centered before computing interaction terms (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2002). We found significant main effects of subjective intoxication and smoker type, Fs (1, 135)> 5.1, p values<.03, as well as a significant subjective intoxication × smoker type group interaction, F (1, 133)= 9.4, p<.003.

As Figure 3 illustrates, simple slope contrasts indicated that increased subjective intoxication levels were associated with greater negative reinforcement expectancies among TCs, β=.30 (.07), t=4.13, p<.000, while negative reinforcement expectancies of HSs remained uniformly elevated, β=.06 (.08), t=−.86, p>.39. These estimates and standard errors were then used to test for mediation within each of the smoker type groups. This final set of analyses confirmed that subjective intoxication mediated the association between alcohol consumption and negative reinforcement expectancies among TCs, Z=2.37, p<.05, but not among HSs, Z<.93.

Figure 3.

Association between subjective intoxication and expectancies of negative reinforcement from smoking as a function of smoker type.

Discussion

Alcohol consumption exerted a main effect on abstinent smokers’ positive outcome expectancies, increasing their expectancies of positive, but not negative, reinforcement from smoking. Results also revealed that HSs reported greater positive outcome expectancies than did TCs. In addition, we found a smoker type × drink interaction, indicating that whereas HSs’ negative reinforcement expectancies were elevated regardless of whether they consumed alcohol, TCs’ negative reinforcement expectancies were positively associated with their subjective level of intoxication. As in Experiment 1, we found no main or interaction effects involving gender.

Neither alcohol consumption nor smoker type was found to decrease abstinent smokers’ negative outcome expectancies. To the contrary, alcohol consumption increased negative social expectancies, although tests of mediation indicated that this effect was not driven by increased levels of subjective intoxication. Although speculative, it may be that smokers who consumed alcohol were less concerned with self-presentation than were those consuming placebo, and as a consequence they were more willing to acknowledge these fears.

General discussion

A principal aim of the present study was to document the instability of smokers’ beliefs about risks and benefits of continued smoking. Two factors (smoking abstinence and alcohol consumption) were posited to affect judgments about smoking consequences. This research extended prior work by offering a more fine-grained analysis of smoking outcomes, including both aversive and reinforcing outcomes, and then further probed subtypes of reinforcing outcomes. Data indicate that smoking abstinence and alcohol consumption can influence smoking-related expectancies.

Overall, both smoking abstinence and alcohol consumption were found to alter smokers’ judgments about the probability of various smoking-related outcomes. Also, as expected, HSs reported greater expectancies of positive outcomes than did TCs across the studies. Mediational analyses confirmed that the observed effects of smoking abstinence and alcohol ingestion were driven by smokers’ urge to smoke and subjective intoxication, respectively. A parallel set of analyses found that the effects of alcohol on smoking expectancies was not explained by reported urge to smoke, providing support for the notion that alcohol consumption yields independent effects on cognitive processes associated with smoking-related probability judgments.

Data from both experiments indicate that neither smoking abstinence alone, nor smoking abstinence combined with alcohol consumption, affected expectancies of negative health-related consequences. This finding seems to contradict the notion that addictive behavior is characterized by a steep discounting of distal negative consequences relative to immediate rewards. One explanation for our data is that, because the health risks of smoking generally are well known, health-related expectancies are relatively stable. Alternatively, this finding may reflect a tendency for relatively healthy continuing smokers to acknowledge the long-term negative health risks associated with smoking while underestimating their personal vulnerability to smoking-related disease and the addictive nature of smoking (e.g., Windschitl, 2002).

In Experiment 2, the interaction that emerged between alcohol consumption and smoking status offers a new perspective on the association between alcohol use and smoking among TCs. TCs sometimes report that they smoke only when they drink, and several theories have been proposed to explain this association (Shiffman & Balabanis, 1995). The present data suggest that the association between alcohol use and smoking among TCs may be influenced by the effects of subjective alcohol intoxication on expectancies of negative reinforcement from smoking. Whereas HSs may be keenly aware of the negative reinforcing properties of smoking with or without alcohol, it seems that TCs associate smoking with negative reinforcement only as they become more intoxicated, perhaps to counteract the sedating effects of alcohol consumption. These data support the notion of a person-level link between alcohol use and smoking among HSs, whereas they suggest a situational link specific to negative reinforcement among TCs (Shiffman & Balabanis, 1995).

An important consideration is whether observed differences in self-report responses on the SCQ-B were artifacts of measurement error. Several indicators suggest, however, that it is reasonable to assume that differences observed in this study are related to our experimental manipulations and not to differential sensitivity of the subscales. The coefficient alpha levels for each of the expectancy subscales indicated an adequate level of internal consistency and were comparable in magnitude. The subscales also had similar standard deviations across each of the study groups, and mean scores did not approach the minimum or maximum limits of the range, which would have raised the possibility of floor or ceiling effects.

Some limitations of this study should be addressed. First, the generalizability of the results is necessarily limited because only self-reported expectancies were included. The use of implicit expectancy measures would be a valuable addition to this line of research (Wiers & Stacy, 2006). Future research also might subdivide negative outcomes more precisely (e.g., expectation of a negative outcome versus the removal of a positive outcome). Second, because we used only a single dose of alcohol, we cannot rule out the possibility of a dose–response relation between alcohol and self-report responses (King & Epstein, 2005). We also did not examine BAC limb effects, so future research that contrasts the effects of alcohol on expectancies during the rising and falling limbs of the BAC curve would be useful. Although we included alcohol and placebo (i.e., told alcohol, given nonalcohol) beverage groups, we did not include a nonalcohol control group (i.e., told nonalcohol, given nonalcohol). Such a control group would have allowed further investigation of the effects of dosage-set on smoking-related expectancies (Martin & Sayette, 1993).

Researchers interested in the link between health-related cognitions and behavior have begun to recognize the need to account for the influence of momentary affective influences on risk perceptions and behavior. Examinations of addictive health-risk behaviors may include the influence of motivational states associated with substance dependence (e.g., as produced with a combination of smoking abstinence and exposure to smoking cues), as well as the acute effects of drug ingestion. Our data suggest that smoking urge and alcohol consumption influence smokers’ beliefs about the consequences of smoking, such that smoking becomes more attractive. Future research should examine further the impact of these factors on decision-making processes related to regular smoking and smoking cessation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grant DA10605. The authors thank Kasey Griffin and the staff of the Alcohol and Smoking Research Laboratory for their assistance. Portions of these data were presented at the annual meeting of the Society of Behavioral Medicine (Boston, April 2005).

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews J, Duncan S. The effect of attitude on development of adolescent cigarette use. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1998;10:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)80135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Brandon TH, Chassin L. Motivational influences on cigarette smoking. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:463–491. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon T, Juliano L, Copeland A. Expectancies of tobacco smoking. In: Kirsch I, editor. How expectancies shape experience. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 1999. pp. 263–299. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer N, Weinstein ND, Cuite C, Herrington J. Risk perceptions and their relation to risk behavior. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27:125–130. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton SM, Tiffany ST. The effects of alcohol consumption on craving to smoke. Addiction. 1997;92:15–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West S, Aiken L. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland A, Brandon T, Quinn E. The Smoking Consequences Questionnaire—Adult: Measurement of smoking outcome expectancies of experienced smokers. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:484–494. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, Dorfman SF, Gritz ER, Heyman RB, Holbrook J, Jaen CR, Kottke TE, Lando HA, Mecklenbur R, Mullen PD, Nett LM, Robinson L, Stitzer M, Tommasello AC, Villejo L, Wewers ME. Treating tobacco use and dependence. Clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Godin G, Valois P, Lepage L, Desharnais R. Predictors of smoking behaviour—An application of Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior. British Journal of Addiction. 1992;87:1335–1343. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman M, Del Boca FK, Darkes J. Alcohol expectancy theory: The application of cognitive neuroscience. In: Leonard KE, Blane HT, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 203–246. [Google Scholar]

- Gwaltney CJ, Shiffman S, Sayette M. Situational correlates of abstinence self-efficacy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:649–660. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A, Li Q, Bauer J, Giovino G, Steger C, Cummings K. Predictors of cessation in a cohort of current and former smokers followed over 13 years. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6(Suppl 3):S363–S370. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331320761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano LM, Brandon TH. Reactivity to instructed smoking availability and environmental cues: Evidence with urge and reaction time. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1998;6:45–53. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.6.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen J, Fortmann S. Craving is associated with smoking relapse: Findings from three prospective studies. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1997;5:137–142. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.5.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Epstein AM. Alcohol dose-dependent increases in smoking urge in light smokers. Alcohol: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:547–552. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000158839.65251.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Gordon JR, editors. Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. New York: Guilford; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Martin C, Sayette MA. Experimental design in alcohol administration research: Limitations and alternatives in the manipulation of dosage-set. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:750–761. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman P, Conner M, Bell R. The theory of planned behavior and smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 1999;18:89–94. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palfai TP, Monti PM, Ostafin B, Hutchinson K. Effects of nicotine deprivation on alcohol-related information processing and drinking behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:96–105. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow D, Marlatt GA. The balanced placebo design: Methodological considerations. Addictive Behaviors. 1981;6:107–122. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(81)90003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA. An appraisal-disruption model of alcohol’s effects on stress responses in social drinkers. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:459–476. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA. Self-regulatory failure and addiction. In: Baumeister R, Vohs K, editors. Handbook of self-regulation. New York: Guilford; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA, Hufford M. Effects of smoking urge on generation of smoking-related information. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1997;27:1395–1405. [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA, Martin C, Hull JG, Wertz J, Perrott M. Effects of nicotine deprivation on craving response covariation in smokers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:110–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA, Martin C, Wertz J, Perrott M, Peters AR. The effects of alcohol on cigarette craving in heavy smokers and tobacco chippers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:263–270. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA, Martin C, Wertz J, Shiffman S, Perrott M. A multi-dimensional analysis of cue-elicited craving in heavy smokers and tobacco chippers. Addiction. 2001;96:1419–1432. doi: 10.1080/09652140120075152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA, Shiffman S, Tiffany ST, Niaura RS, Martin C, Shadel WG. The measurement of drug craving. Addiction. 2000;95:S189–S210. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro D, Jamner L, Davydov D, James P. Situations and moods associated with smoking in everyday life. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:342–345. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.16.4.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Balabanis M. Associations between alcohol and tobacco. In: Fertig J, Allen J, editors. Alcohol and tobacco: From basic science to policy. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse; 1995. pp. 17–36. National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse, Research Monograph No. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Fischer LA, Paty JA, Gnys M, Hickox M, Kassel JD. Drinking and smoking: A field study of their association. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1994;16:203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Paty J, Gnys M, Kassel J, Elash C. Nicotine withdrawal in chippers and regular smokers: Subjective and cognitive effects. Health Psychology. 1995;14(4):301–309. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.4.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Paty J, Gwaltney C, Dang Q. Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: An analysis of unrestricted smoking patterns. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:166–171. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Paty J, Kassel J, Gnys M, Zettler-Segal M. Smoking behavior and smoking history of tobacco chippers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1994;2:126–142. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennen H, Affleck G, Armeli S. Daily processes in health and illness. In: Suls J, Wallston K, editors. Social psychological foundations of health. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein ND. Testing four competing theories of health-protective behavior. Health Psychology. 1993;12:324–333. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.4.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, Stacy AW. Handbook of implicit cognition and addiction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Windschitl PD. Judging the accuracy of a likelihood judgment: The case of smoking risk. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 2002;15:19–35. [Google Scholar]