Summary Paragraph

Neurons and cancer cells utilize glucose extensively, yet the precise advantage of this adaptation remains elusive. These two seemingly disparate cell types also exhibit an increased regulation of the apoptotic pathway, which allows for their long term survival1. Here we show that both neurons and cancer cells strictly inhibit cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis by a mechanism dependent on glucose metabolism. We report that the proapoptotic activity of cytochrome c is influenced by its redox state and that increases in Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) following an apoptotic insult lead to the oxidation and activation of cytochrome c. In healthy neurons and cancer cells, however, cytochrome c is reduced and held inactive by intracellular glutathione (GSH) generated as a result of glucose metabolism by the pentose phosphate pathway. These results uncover a striking similarity in apoptosis regulation between neurons and cancer cells and provide insight into an adaptive advantage offered by the Warburg effect for cancer cell evasion of apoptosis and for long-term neuronal survival.

Keywords: Cytochrome c, ROS, caspases, apoptosis, Glycolysis, Pentose Phosphate Pathway

Apoptosis is a genetically regulated process that is essential for the development of the organism, but its dysregulation can lead to neurodegenerative disorders as well as cancer2, 3. A critical event in the apoptotic pathway is the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria. In healthy cells, cytochrome c resides in the mitochondrial intermembrane space where it serves as a redox carrier for the electron transport chain. However, in response to many apoptotic stimuli, cytochrome c is released into the cytosol where it can initiate the formation of the apoptosome complex, leading to caspase activation and subsequent cell death4. Emerging evidence indicates that cells such as postmitotic neurons, which last the lifetime of the organism, as well as cancer cells, which must overcome a cell death response, both strictly inhibit the apoptotic pathway1. Interestingly, despite the striking morphological and functional differences between neurons and cancer cells, both extensively metabolize glucose5, 6. Here we examined whether the mutual reliance on glucose metabolism was of critical importance to the increased resistance to apoptosis in neurons and cancer cells.

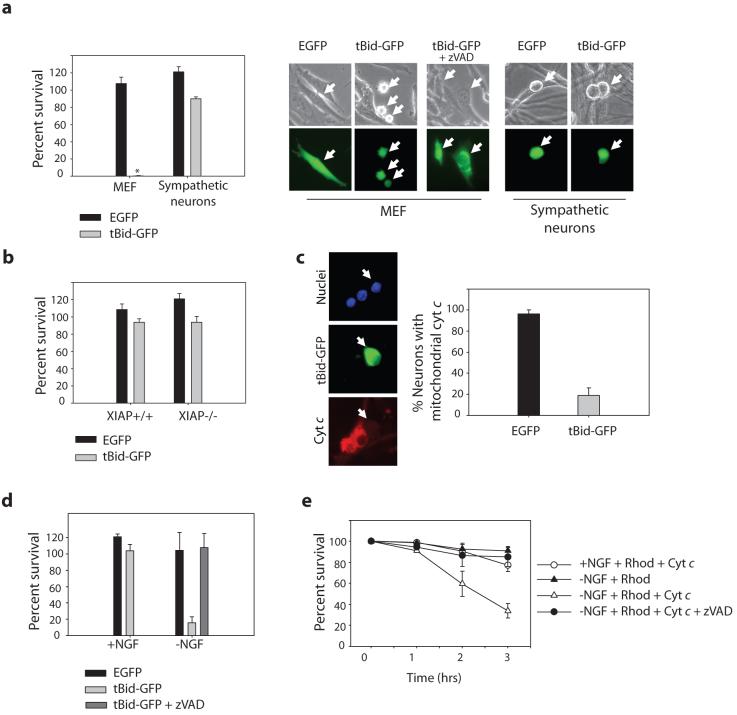

We assessed the ability of endogenous cytochrome c to activate apoptosis in sympathetic neurons by using truncated Bid (tBid). Full length Bid is cleaved intracellularly into tBid in response to certain apoptotic stimuli, where it then acts as a potent inducer of cytochrome c release from mitochondria7. While expression of tBid-GFP plasmid DNA in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) resulted in rapid and complete apoptosis, nerve growth factor (NGF)-maintained sympathetic neurons remained remarkably resistant to expression of tBid-GFP (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Information, Fig. S1). Sympathetic neurons are known to be resistant to exogenously microinjected cytochrome c because of the strict inhibition of caspases by XIAP. In contrast to wildtype neurons, XIAP-deficient sympathetic neurons are sensitive to microinjection of excess exogenous cytochrome c8. However, we were surprised to find that the release of endogenous cytochrome c with tBid was incapable of inducing apoptosis even in XIAP-deficient neurons (Fig. 1b). Although it did not induce apoptosis, tBid was completely capable of releasing cytochrome c in these neurons (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Information, Fig. S2a). Likewise, injection of a Bid BH3 peptide in neurons induced potent release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria that did not result in death (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1c, S2b). Interestingly, despite having released cytochrome c, these neurons maintain their mitochondrial membrane potential (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2c)9. Thus, in NGF-maintained neurons, the release of endogenous cytochrome c was incapable of inducing apoptosis even in the absence of XIAP (Supplementary Information, Fig. S3). To focus on this unexpected XIAP-independent mechanism of post-cytochrome c regulation, we conducted all following experiments in neurons isolated from XIAP-deficient mice.

Figure 1. Endogenous cytochrome c release is incapable of inducing apoptosis in NGF-maintained sympathetic neurons.

a) Cultures of MEFs or sympathetic neurons were injected with tBid-GFP, or GFP plasmid. Cell survival was quantified by cell morphology and expressed as a percentage of alive and healthy green cells at 24 hrs compared to 5 hrs post-injection. *represents no MEF survival. Representative photographs of MEFs and neurons are shown; arrows point to injected cells. b) XIAP -/- sympathetic neurons or wildtype littermates were injected with EGFP or tBid-GFP, and cell survival was quantified as in (a). c) tBid-GFP was injected into sympathetic neurons, and allowed to express for 24 hrs. Cells were fixed, and the status of cytochrome c analyzed by immunofluorescence. Percentage of neurons with mitochondrial cytochrome c is quantified in XIAP -/- neurons. d) XIAP -/- sympathetic neurons were either maintained in NGF-containing media, or deprived of NGF for 8 hrs (with or without 50 μM zVAD), followed by injection with EGFP or tBid-GFP. Cell survival was quantified by cell morphology and expressed as a percentage of alive and healthy green cells at 16 hrs compared to 5 hrs post-injection. e) XIAP -/- sympathetic neurons were deprived of NGF (with or without 50 μM zVAD) for 12 hrs followed by injection with rhodamine alone, or cytochrome c (2.5 μg/μl) along with rhodamine to mark injected cells. Cell survival was assessed at various time points following injection. Error bars represent ±SEM of three independent experiments.

Despite the resistance of neurons to direct cytochrome c release by tBid, sympathetic neurons readily undergo cytochrome c-mediated cell death in response to multiple apoptotic stimuli10, 11. Thus, apoptotic stimuli must render endogenous cytochrome c capable of activating apoptosis in neurons. Indeed, NGF deprivation as well as DNA damage with etoposide sensitized sympathetic neurons to apoptosis induced by tBid-mediated cytochrome c release (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Information, Fig. S1b,c, S4a). Since tBid may cause the release of multiple factors from the mitochondria, we examined whether this observed effect was a direct result of sensitization to cytochrome c. Indeed, injection of cytochrome c into NGF-deprived or DNA-damaged neurons (at a time point prior to endogenous cytochrome c release) also showed increased sensitivity (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Information, Fig. S4b).

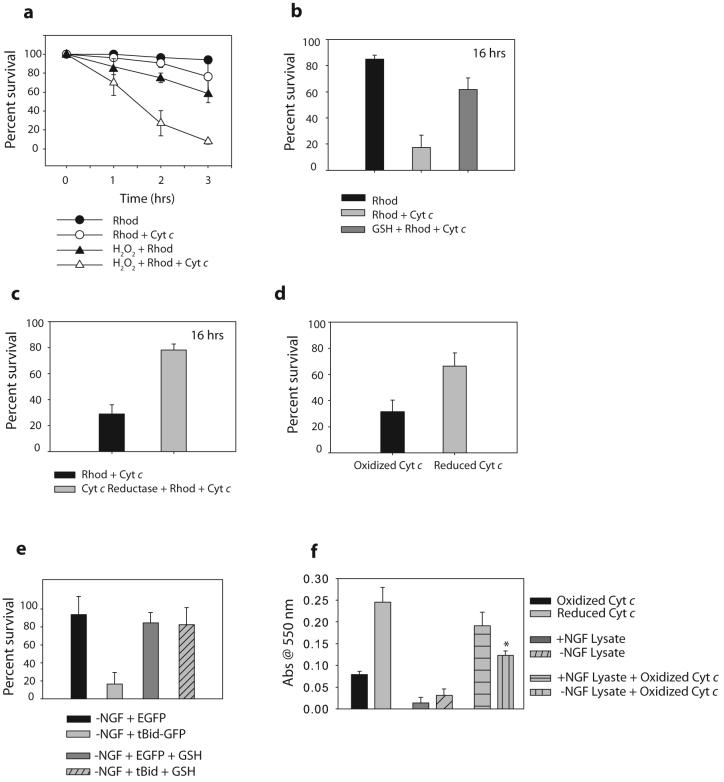

To be apoptotically active, cytochrome c must exist as a holoenzyme complete with its heme prosthetic group12. In vitro studies have examined whether the redox state of cytochrome c affects its apoptotic activity. While some show that oxidized cytochrome c is more apoptotically active, others suggest that the reduced form can also function13-19. In particular, a recent study by Borutaite and Brown showed that oxidation of cytochrome c by cytochrome c oxidase promotes caspase activation, whereas its reduction by tertamethylphenylenediamine blocks caspase activation18. Likewise, oxidized but not reduced cytochrome c was found to promote apoptosis in permeabilized HepG2 cells19. To determine whether the intracellular redox environment affects the sensitivity of intact neurons to cytochrome c, we treated neurons with either low levels of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to create a more oxidized environment, or cell permeable reduced glutathione (GSH) to simulate a reduced environment. Neurons injected with 2.5 μg/μl cytochrome c exhibit substantial death only 10-16 hrs after the injections (Fig. 2a, b). However, H2O2 greatly increased the sensitivity of neurons to injected cytochrome c (Fig. 2a), while neurons treated with GSH were resistant (Fig. 2b). These results show that in intact cells, the redox environment has a dramatic affect on the ability of cytochrome c to promote apoptosis.

Figure 2. Oxidation of cytochrome c increases its apoptotic activity.

a) XIAP -/- sympathetic neurons were treated with 20-50 μM of H2O2 for 20 minutes, followed by injection with cytochrome c protein and rhodamine, or rhodamine dye alone. Cell survival was assessed at various time points following injection. b) XIAP -/- sympathetic neurons were treated with 10 mM GSH ethyl ester for 12 hrs, followed by injection of cytochrome c along with rhodamine, or rhodamine alone. Cell survival was assessed at 16 hrs following injection. c) XIAP -/- sympathetic neurons were injected with either cytochrome c, or cytochrome c that was pre-incubated with 10 Units/ml of cytochrome c reductase. Cell survival was assessed at 16 hrs following injection. d) XIAP -/- sympathetic neurons were injected with either cytochrome c, or cytochrome c that had been pre-incubated with DTT (and subsequently separated) to reduce this cytochrome c. Percent survival was assessed after 6 hrs. e) XIAP -/- sympathetic neurons were deprived on NGF for 8 hrs in the presence of 10 mM GSH, followed by injection with EGFP or tBid-GFP constructs. Cell survival was quantified by cell morphology and expressed as a percentage of alive and healthy green cells at 16 hrs compared to 5 hrs post-injection. f) Exogenous cytochrome c (which is primarily oxidized) was added at a concentration of 10 uM to neuronal extracts, and Abs550 was measured following a 15 min. incubation. Control experiments measuring Abs550 of reduced or oxidized cytochrome c are also shown. Results are mean (±SEM) of three independent experiments.

As changes in the redox environment can have widespread affects, we determined whether the ability of the reduced cellular environment to inhibit cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis is a result of the specific inactivation of cytochrome c. Incubation of exogenous cytochrome c (which is predominantly oxidized) with cytochrome c reductase or DTT rendered this now reduced cytochrome c (Supplementary Information, Fig. S7a) less effective for promoting apoptosis in injected neurons (Fig. 2c,d). Thus, oxidized cytochrome c was a more potent inducer of apoptosis than reduced cytochrome c. In addition, we generated a N52I mutant of cytochrome c which has increased stability20. While the redox status of this protein in intact cells is unclear, injection of the N52I mutant cytochrome c into sympathetic neurons induced significantly less apoptosis than did wildtype cytochrome c (Supplementary Information, Fig. S5).

The observation that cytosolic cytochrome c requires an oxidized cellular environment to be proapoptotic leads to two predictions. First, that the ability of tBid-induced cytochrome c release to promote apoptosis in MEFs but not in NGF-maintained neurons could be due to a marked difference in their redox environment. Consistent with this, we find that the average intensity of the redox-sensitive dye 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2′, 7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2 DCFDA) was 5 fold less in sympathetic neurons as compared to MEFs, indicating reduced levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in sympathetic neurons (Supplementary Information, Fig. S6a). Second, that NGF deprivation, which sensitizes neurons to cytochrome c-induced death, may result in an increased oxidized cellular environment. It is known that the cellular redox status of cells can alter during apoptosis21. Indeed, ROS intensity as measured by CM-H2 DCFDA and dihydrorhodamine (DHR) was elevated more than 2.5 fold after NGF deprivation in neurons (Supplementary Information, Fig. S6b,c)22, 23. This increase in ROS following NGF deprivation was important to permit cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis, as addition of GSH completely inhibited the ability of NGF deprivation to sensitize neurons to cytochrome c release by tBid (Fig. 2e). Importantly, we examined whether there was a difference in the ability of NGF-maintained versus NGF-deprived lysates to affect the redox state of cytochrome c. As anticipated, while oxidized cytochrome c remained oxidized in NGF-deprived lysates, it was rapidly reduced upon incubation with NGF-maintained neuronal lysates (Fig. 2f). Likewise, addition of reduced cytochrome c resulted in its oxidation in NGF-deprived, but not NGF-maintained neuronal lysates (Supplementary Information, Fig. S7b), indicating that cytosolic cytochrome c would exist in a different redox state in NGF-maintained, healthy neurons, versus those that are undergoing apoptosis in response to NGF deprivation.

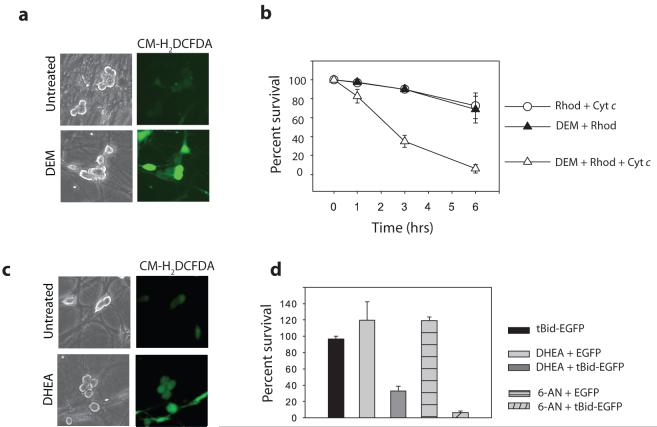

GSH is one of the most prevalent intracellular reducing agents and maintains redox homeostasis by scavenging ROS. We found that endogenous GSH is necessary for maintaining cytochrome c in an inactive state in NGF-maintained neurons, as removal of GSH with Diethyl Maleate (DEM) or inhibition of GSH synthesis by Buthioninesulfoximine (BSO) leads to an increase in ROS22 and sensitizes cells to cytosolic cytochrome c (Fig. 3a,b, Supplementary Information, Fig. S8a). Levels of GSH are maintained in cells by reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), which is generated when glucose is metabolized via the pentose phosphate pathway24. We examined whether the pentose phosphate pathway was important for regulating the redox status of neurons, and thus cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis. Neurons treated with the pentose phosphate pathway inhibitors, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) or 6-anicotinamide (6-AN), accumulated high levels of ROS and became sensitive to endogenous cytochrome c release with tBid (Fig. 3c,d, Supplementary Information, Fig. S8b). This effect was not unique to neurons derived from the superior cervical ganglia as sensory neurons from the Dorsal Root Ganglia (DRGs) were also resistant to cytochrome c release by tBid, but became sensitive after DHEA treatment (Supplementary Information, Fig. S9). Together, these data show that glucose metabolism via the pentose phosphate pathway promotes neuronal survival by maintaining GSH levels and directly restricting cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis.

Figure 3. Role of the pentose phosphate shunt in cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis.

a) Average ROS levels in sympathetic neurons were observed by fluorescence intensity of the redox-sensitive dye CM-H2DCFDA following 30 min of GSH depletion with 0.1 mM DEM. b) XIAP -/- sympathetic neurons (NGF-maintained) were treated with 0.1 mM DEM for 30 min followed by injection of cytochrome c and rhodamine, or rhodamine dye alone. Cell survival was assessed at various timepoints. c) Average ROS levels were observed as in (a) following inhibition of the Pentose Phosphate Pathway with 200 μM DHEA for 24 hrs. d) XIAP -/- sympathetic neurons (NGF-maintained) were treated with 200 μM DHEA for 6 hrs, 0.1 mM 6-AN for 24 hrs, or left untreated, followed by injection with tBid-GFP or EGFP constructs. Cell survival was expressed as a percentage of healthy green cells at 16 hrs compared to 5 hrs post-injection. Error bars represent ±SEM of n≥3.

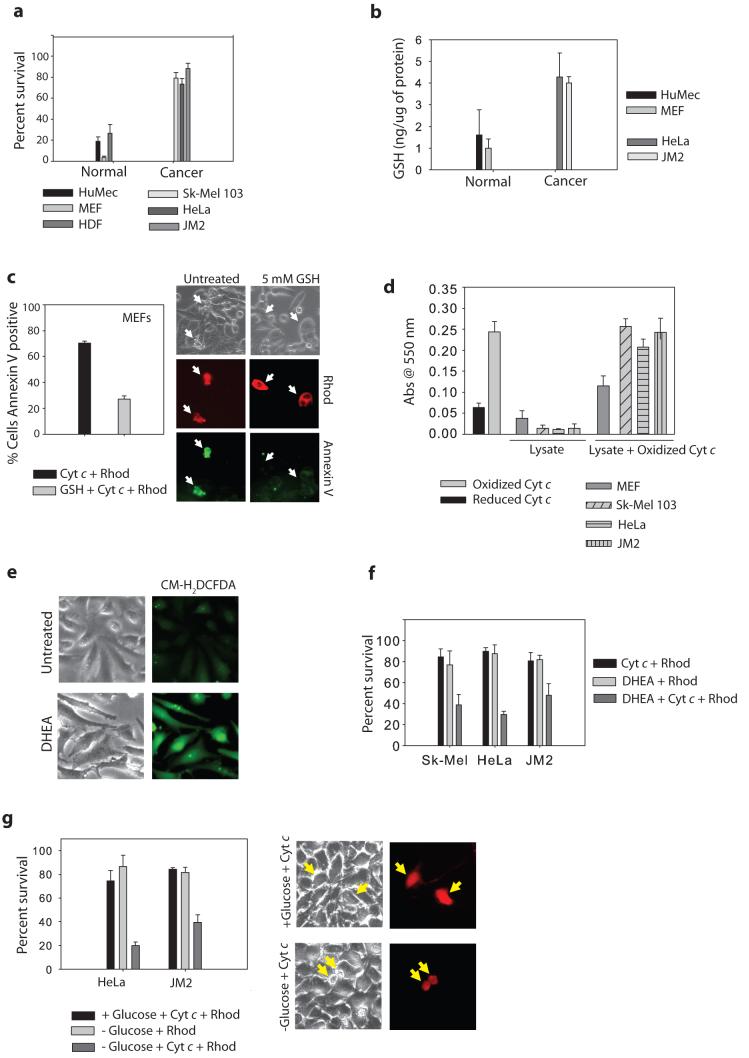

Like neurons, many cancer cells are known to metabolize glucose extensively, a phenomenon known as the Warburg effect6. To investigate whether increased glucose metabolism in cancer cells directly regulates apoptosis at the point of cytochrome c, we first examined the sensitivity of cancer cells to cytosolic injection of cytochrome c. Cytochrome c was injected in the presence of Smac to eliminate the activity of IAPs that are known to block caspase activation in many cancer cells25, thus focusing on IAP-independent mechanisms of cytochrome c regulation. While normal cells readily underwent apoptosis in response to cytosolic cytochrome c, cancer cells showed an increased resistance (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Information, Fig. S10a). Strikingly, the decreased sensitivity to cytochrome c correlated well with the increased levels of intracellular GSH found in these cancer cells (Fig. 4b). Interestingly, treatment of MEFs with cell permeable GSH increased their resistance to cytosolic cytochrome c (Fig. 4c). In addition, while incubation of oxidized cytochrome c with MEF lysate did not significantly affect the redox state of oxidized cytochrome c, oxidized cytochrome c was rapidly reduced upon incubation with lysates generated from cancer cells (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4. Glucose metabolism protects cancer cells from cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis.

a) Normal cells (Human Mammary Epithelial Cells-HuMECs, MEFs, Human Dermal Fibroblasts-HDFs) or cancer cell lines (Sk-Mel 103, HeLa, JM2) were injected with cytochrome c and Smac protein and cell survival was assessed after 30 minutes. b) Total glutathione (GSH) was measured in normal mitotic cells as well as cancer cell lines, and expressed as a concentration of GSH to total cellular protein. c) MEFs were treated with 5 mM GSH ethyl ester for 15 min, followed by injection with cytochrome c. After 1 hr, injected cells were assessed for Annexin V positivity. Photographs show representative Annexin V-FITC staining of cytochrome c injected cells (arrows). d) Exogenous cytochrome c (which is primarily oxidized) was added at a concentration of 10 μM to normal or cancer cell extract, and Abs550 was measured following a 15 min incubation. e) Average ROS levels in HeLa cells measured by fluorescence of CMH2DCFDA in the absence or presence of the pentose phosphate pathway inhibitor, DHEA (200 μM) for 6 hrs. f) The pentose phosphate pathway was inhibited in various cancer cell lines for 6 hrs by addition of 200 μM DHEA, followed by injection of cytochrome c and Smac protein. Cell survival was assessed at 3 hrs. g) JM2 and HeLa cells were deprived of glucose for 16 hrs followed by injection with cytochrome c and Smac, and assessed for survival at various time points. Images are representative of JM2 cells at 3 hrs following cytochrome c injection. Error bars represent ±SEM of n≥3.

We next examined whether enhanced glucose metabolism through the pentose phosphate pathway in HeLa and JM2 cancer cells contributes to cellular redox homeostasis, and thus resistance to cytochrome c. Indeed, addition of the pentose phosphate inhibitor DHEA increased ROS levels and specifically rendered these cancer cells sensitive to cytosolic cytochrome c (Fig. 4e,f, Supplementary Information, Fig. S10b). Importantly, glucose deprivation also resulted in a similar increase in sensitivity to cytochrome c (Fig. 4g). Together, these results show that the ability of cytochrome c to induce apoptosis is strictly regulated by its redox state and that glucose flux is a critical regulator of cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis.

By coupling the proapoptotic activity of cytochrome c to the pentose phosphate pathway, cells which have increased glucose metabolism, such as neurons and cancer cells, are able to effectively maintain a restrictive environment for cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis. Such a regulation would be of particular physiological importance for neurons that have limited regenerative potential and survive long term, and advantageous to cancer cells in evading apoptosis. Flux through the pentose phosphate pathway is likely to inhibit apoptosis in multiple scenarios. For example, upregulation of TIGAR following p53 activation by DNA damage was recently shown to engage the pentose phosphate pathway and promote cell survival26. Overexpression of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase is also shown to promote tumor formation by increasing GSH through pentose phosphate pathway27. Our results suggest that a specific mechanism by which this could inhibit apoptosis is through direct inactivation of cytochrome c.

Although maintenance of redox homeostasis is a primary function of the pentose phosphate pathway, flux through this pathway may also inhibit apoptosis at other points. For example, NADPH production through the pentose phosphate pathway maintains caspase-2 in an inactive state in Xenopus egg extracts by a mechanism independent of GSH synthesis28.

Neurons undergoing cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis must overcome multiple blocks in order to undergo cell death. We have shown previously that endogenous XIAP is a potent inhibitor of cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis in neurons8, and here, that endogenous cytochrome c itself is incapable of inducing apoptosis in NGF-maintained neurons. In response to developmental apoptosis after trophic factor deprivation, these neurons not only exhibit degradation of XIAP to allow for caspase activation, but also a marked decrease in glucose uptake29 and increase in ROS (Supplementary Information, Fig. S6b,c)8, 22, 23 which our results show is essential for the activation of cytochrome c, and thus, apoptosis.

Increases in intracellular ROS as well as mitochondrial damage are commonly seen during aging and associated with apoptotic cell death in many neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson's Disease30, 31. Our results provide mechanistic insight into how even a modest increase in ROS would prime neurons to undergo apoptosis in response to otherwise potentially non-lethal events of mitochondrial damage and cytochrome c release.

Neurons and cancer cells are indeed strikingly distinct by most criteria. Different cancer cells themselves appear to inhibit the apoptotic pathway at different points. However, these results bring into focus the possibility that the multiple mechanisms evolved by neurons to restrict apoptosis would be the same ones adapted by some mitotic cells during their progression to becoming cancerous.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

All reagents were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO) or Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) unless otherwise stated. Collagenase and trypsin were purchased from Worthington Biochemical Corporation (Freehold, NJ). The GSH:GSSG kit was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Horse cytochrome c was purchased from Sigma. zVAD-fmk was purchased from Enzyme Systems (Livermore, CA). Annexin VFITC was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Recombinant Smac protein was purified from bacteria as previously described8 and used at a concentration of 1.5 mg/ml. MEFs were a kind gift provided by Dr. Douglas Green (St. Jude's Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN). HDFs and HeLa cells were obtained from UNC Tissue Culture Facility, and JM2 cells were a kind gift of Dr. Ekhson Holmuhamedov (UNC, Chapel Hill, NC). Sk-Mel 103 cells were a kind gift from Dr. Channing Der (UNC, Chapel Hill, NC). XIAP-/- mice were a kind gift from Dr. Craig Thompson (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA).

Sympathetic neuronal cultures

Primary sympathetic neurons were dissected from the superior cervical ganglia of postnatal day 0-1 mice from wildtype ICR or XIAP-deficient C57BL/6 mice and maintained in culture as described previously8. Cells were plated on collagen coated dishes at a density of 10,000 cells per well. Neurons were grown for 4-5 days in NGF-containing media before treating them with experimental conditions. For NGF deprivation, cultures were rinsed three times with medium lacking NGF, followed by the addition of goat anti-NGF neutralizing antibody to this media. Cells were treated with various compounds used at the concentration indicated: Etoposide (20 μM); DHEA (200 μM), 6-AN (0.1 mM); DEM (0.1 mM); GSH-ethyl ester (10 mM); BSO (200 μM).

Microinjection and quantitation of cell survival

Cells were injected with horse cytochrome c protein (2.5 μg/μl) or Bid BH3 peptide (8 mM) (AnaSpec) along with Rhodamine dextran (4 μg/μl) in microinjection buffer containing 100 mM KCl and 10 mM KPi, pH 7.4 as described previously8. Immediately after injections, the number of rhodamine-positive cells were counted. At various times after injections, the number of viable injected cells remaining was determined using the same counting criteria and expressed as a percentage of the original number of microinjected cells. This method of assessing survival has correlated well with other cell survival assays such as trypan blue exclusion and staining with calcein AM8.

In experiments involving microinjection of DNAs, 100 ng/μl of the tBid expressing plasmid, or EGFP vector in microinjection buffer was injected into the nucleus of neurons or MEFs. To quantitate survival after injection, GFP-positive cells were counted 5 hours after injection as well as 24 hours following injection. Cell survival is expressed as a ratio of viable GFP-positive cells at 24 hours post-injection over GFP-positive cells at 5 hours post injection. Since tBid is such a rapid inducer of death (under certain conditions), the window between detectable expression of tBid-GFP in cells and apoptosis is narrow. Therefore, we picked an early time point for time zero in order not to exclude any cells that may die soon after this. Under conditions where injection of tBid-GFP, or GFP alone does not kill cells, this number becomes greater than 100% as a few additional cells begin to express visible GFP after the initial count. In conditions where cell death occurred, this death was confirmed as caspase dependent as it could be inhibited with zVAD-fmk (50 μM). Cell survival was also assessed by Annexin-V positivity according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Immunofluorescence for assessing cytochrome c release

The status of cytochrome c (whether intact in the mitochondria or released) was examined by immunofluorescence. Sympathetic neurons exhibit a punctate mitochondrial staining with anti-cytochrome c antibody, which is lost as cytochrome c is released from the mitochondria. Briefly, cultured sympathetic neurons were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated overnight with anti-cytochrome c (556432, BD Biosciences), or anti-GFP (Cell Signaling) primary antibody followed by a 2 hour incubation with anti-mouse Cy3, anti-mouse Alexa 488, and anti-Chicken Alexa 488 secondary antibody (Jackson Labs). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33258 (Molecular Probes).

ROS measurement

The redox-sensitive dye CM-H2 DCFDA or dihydrorhodamine (DHR) (Molecular Probes) was used to measure ROS levels in sympathetic neuronal cultures and cell lines using the protocol described previously22. CM-H2 DCFDA is non-fluorescent when reduced and following permeabilizing of the cell is cleaved by esterases and is trapped in the cell where oxidation converts it to a fluorescent form. After treatment of cells with various experimental conditions, cells were incubated with 10 μM CM-H2 DCFDA or 10 μM DHR for 20 minutes followed rinsing 3 times in PBS. Fluorescent intensity of cells was represented as an image, and or quantitated by measuring pixel intensity in a 50 μm2 area within individual soma using Metamorph software or by measuring the fluorescence intensity using a Fluoroskan (ThermoLabSystems) plate reader.

Preparing reduced cytochrome c, and assessing cytochrome c redox status

Cytochrome c was reduced by incubating it with 10 Units/ml of cytochrome c reductase (NADPH) followed by injection into neurons. Alternatively, cytochrome c was reduced with 0.5 mM DTT, followed by separation on PD-10 columns (GE Healthcare). The redox status of cytochrome c was assessed by monitoring its absorbance at 550 nm on Nanodrop spectrophotometer. For experiments involving analysis of redox activity of cytochrome c following NGF deprivation, sympathetic neurons were plated at a density of 100,000 cells, and maintained in NGF, or deprived of NGF for 12 hours. Neuronal lysate was collected and incubated with oxidized cytochrome c (10 μM) for 15 min prior to analysis as described above. For mitotic cells, oxidized cytochrome c (10 μM) was incubated with 200 μg cell lysates for 15 min before measurement at 550 nm.

Reduced glutathione measurements

Measurements of GSH:GSSG were carried out using the GSH:GSSG ratio kit according to the manufacturer's protocol of a modified method by Tietze32. Briefly, cells were lysed in 5% Metaphosphoric acid for 15 min, centrifuged, and the glutathione contents of the supernatant were measured by the rate of colorimetric change of 5,5′-dithiobis(nitrobenzoic acid) at 412 nm in the presence of glutathione reductase and NADPH. The acid pellet was resuspended in 1 N NaOH and the solubilized protein concentration measured by the Lowry method (BioRad). Total glutathione (GSH) is represented as ng of glutathione per μg of cellular protein.

Image acquisition and processing

All images were acquired by a Hamamatsu ORCAER digital B/W CCD camera mounted on a Leica inverted fluorescence microscope (DMIRE 2). The image acquisition software was Metamorph version 5.0 (Universal Imaging Corporation). Images were scaled down and cropped in Adobe Photoshop to prepare the final figures.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Jeffery Rathmell, Dr. Gary Pielak, Dr. Eugene Johnson, and members of the Deshmukh Lab for helpful discussions and critical review of this manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants NS42197 and GM078366 (to MD), NS055486 (to AEV) and by the UNC Cancer Research Fund.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Wright KM, Deshmukh M. Restricting apoptosis for postmitotic cell survival and its relevance to cancer. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1616–1620. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.15.3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuan J, Yankner BA. Apoptosis in the nervous system. Nature. 2000;407:802–809. doi: 10.1038/35037739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green DR, Evan GI. A matter of life and death. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:19–30. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang X. The expanding role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2922–2933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schubert D. Glucose metabolism and Alzheimer's disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2005;4:240–257. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esposti MD. The roles of Bid. Apoptosis. 2002;7:433–440. doi: 10.1023/a:1020035124855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potts PR, Singh S, Knezek M, Thompson CB, Deshmukh M. Critical function of endogenous XIAP in regulating caspase activation during sympathetic neuronal apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:789–799. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deshmukh M, Kuida K, Johnson EM., Jr. Caspase inhibition extends the commitment to neuronal death beyond cytochrome c release to the point of mitochondrial depolarization. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:131–143. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neame SJ, Rubin LL, Philpott KL. Blocking cytochrome c activity within intact neurons inhibits apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:1583–1593. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.6.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaughn AE, Deshmukh M. Essential postmitochondrial function of p53 uncovered in DNA damage-induced apoptosis in neurons. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:973–981. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang J, et al. Prevention of apoptosis by Bcl-2: release of cytochrome c from mitochondria blocked. Science. 1997;275:1129–1132. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hancock JT, Desikan R, Neill SJ. Does the redox status of cytochrome C act as a fail-safe mechanism in the regulation of programmed cell death? Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:697–703. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00646-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan Z, Voehringer DW, Meyn RE. Analysis of redox regulation of cytochrome c-induced apoptosis in a cell-free system. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:683–688. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suto D, Sato K, Ohba Y, Yoshimura T, Fujii J. Suppression of the proapoptotic function of cytochrome c by singlet oxygen via a haem redox state-independent mechanism. Biochem J. 2005;392:399–406. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hampton MB, Zhivotovsky B, Slater AF, Burgess DH, Orrenius S. Importance of the redox state of cytochrome c during caspase activation in cytosolic extracts. Biochem J. 1998;329(Pt 1):95–99. doi: 10.1042/bj3290095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kluck RM, et al. Cytochrome c activation of CPP32-like proteolysis plays a critical role in a Xenopus cell-free apoptosis system. EMBO J. 1997;16:4639–4649. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borutaite V, Brown GC. Mitochondrial regulation of caspase activation by cytochrome oxidase and tetramethylphenylenediamine via cytosolic cytochrome c redox state. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:31124–31130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700322200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li M, Wang AJ, Xu JX. Redox state of cytochrome c regulates cellular ROS and caspase cascade in permeablized cell model. Protein Pept Lett. 2008;15:200–205. doi: 10.2174/092986608783489490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doyle DF, Waldner JC, Parikh S, Alcazar-Roman L, Pielak GJ. Changing the transition state for protein (Un) folding. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7403–7411. doi: 10.1021/bi960409u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai J, Jones DP. Mitochondrial redox signaling during apoptosis. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1999;31:327–334. doi: 10.1023/a:1005423818280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirkland RA, Franklin JL. Evidence for redox regulation of cytochrome C release during programmed neuronal death: antioxidant effects of protein synthesis and caspase inhibition. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1949–1963. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01949.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenlund LJ, Deckwerth TL, Johnson EM., Jr. Superoxide dismutase delays neuronal apoptosis: a role for reactive oxygen species in programmed neuronal death. Neuron. 1995;14:303–315. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplowitz N, Aw TY, Ookhtens M. The regulation of hepatic glutathione. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1985;25:715–744. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.25.040185.003435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verhagen AM, Vaux DL. Cell death regulation by the mammalian IAP antagonist Diablo/Smac. Apoptosis. 2002;7:163–166. doi: 10.1023/a:1014318615955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bensaad K, et al. TIGAR, a p53-inducible regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis. Cell. 2006;126:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuo W, Lin J, Tang TK. Human glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) gene transforms NIH 3T3 cells and induces tumors in nude mice. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:857–864. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000315)85:6<857::aid-ijc20>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nutt LK, et al. Metabolic regulation of oocyte cell death through the CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation of caspase-2. Cell. 2005;123:89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deckwerth TL, Johnson EM., Jr. Temporal analysis of events associated with programmed cell death (apoptosis) of sympathetic neurons deprived of nerve growth factor. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1207–1222. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.5.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carney JM, Smith CD, Carney AM, Butterfield DA. Aging- and oxygen-induced modifications in brain biochemistry and behavior. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;738:44–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb21788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rego AC, Oliveira CR. Mitochondrial dysfunction and reactive oxygen species in excitotoxicity and apoptosis: implications for the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurochem Res. 2003;28:1563–1574. doi: 10.1023/a:1025682611389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tietze F. Enzymic method for quantitative determination of nanogram amounts of total and oxidized glutathione: applications to mammalian blood and other tissues. Anal Biochem. 1969;27:502–522. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(69)90064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.