Abstract

Inflammatory mediators, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1beta, appear integral in initiating and/or propagating Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-associated pathogenesis. We have previously observed a significant increase in the number of mRNA transcripts encoding the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α, which correlated to regionally enhanced microglial activation in the brains of triple transgenic mice (3xTg-AD) before the onset of overt amyloid pathology. In this study, we reveal that neurons serve as significant sources of TNF-α in 3xTg-AD mice. To further define the role of neuronally derived TNF-α during early AD-like pathology, a recombinant adeno-associated virus vector expressing TNF-α was stereotactically delivered to 2-month-old 3xTg-AD mice and non-transgenic control mice to produce sustained focal cytokine expression. At 6 months of age, 3xTg-AD mice exhibited evidence of enhanced intracellular levels of amyloid-β and hyperphosphorylated tau, as well as microglial activation. At 12 months of age, both TNF receptor II and Jun-related mRNA levels were significantly enhanced, and peripheral cell infiltration and neuronal death were observed in 3xTg-AD mice, but not in non-transgenic mice. These data indicate that a pathological interaction exists between TNF-α and the AD-related transgene products in the brains of 3xTg-AD mice. Results presented here suggest that chronic neuronal TNF-α expression promotes inflammation and, ultimately, neuronal cell death in this AD mouse model, advocating the development of TNF-α-specific agents to subvert AD.

Inflammation has long been hypothesized to play a critical role in Alzheimer’s disease (AD).1,2,3 Focal and diffuse gliosis is highly evident in areas of pathology, especially at sites of ghost tangles, amyloid-bearing plaques, and angiopathic capillaries in late-stage AD brain.4,5,6,7,8 Correlating with pathology, steady-state levels of inflammatory molecules, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1beta, and complement components, are significantly enhanced in postmortem brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid from AD-afflicted individuals (reviewed in9). While extant data better support a secondary role for inflammation in AD pathogenesis rather than an etiological one, the precise function of inflammatory processes, especially those initiated at presymptomatic stages, has yet to be elucidated.

The cells of the central nervous system known to produce pro-inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α, in response to AD-related insults include astrocytes, microglia, and neurons (reviewed in10). Although microglia and astrocytes are classically believed to serve as the predominant sources of TNF-α in the central nervous system, neurons can highly express this cytokine in the setting of disease, including spinal cord injury,11 stroke,12 and sciatic nerve injury.13

Several AD-related studies have investigated the effects of TNF-α, particularly in relation to microglia-mediated release; however, none have explored the role of neuronally derived TNF-α during early AD pathogenesis. Using the triple transgenic-AD (3xTg-AD) mouse model, which exhibits progressive temporal and regional amyloid and tau-related pathologies, we previously demonstrated that TNF-α expression and numbers of microglia are markedly enhanced at prepathological time points in the brain.14 These inflammatory changes are coincident with the appearance of cognitive deficits and synaptic dysfunction in these mice,1,15 suggesting that TNF-α participates in early disease-related pathophysiology. Herein, we demonstrate that neurons in the brains of 3xTg-AD mice express TNF-α and investigate the effects that neuronally derived TNF-α impart on AD-related pathological outcome. TNF-α was constitutively expressed in the 3xTg-AD and non-transgenic (Non-Tg) mouse hippocampus beginning at 2 months of age via a recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 2 vector (rAAV). Brain-specific effects of TNF-α overexpression on pro-inflammatory gene expression, amyloid and tauopathy progression, and neuronal viability were assessed. Recombinant AAV-mediated TNF-α expression led to defined early activation of proximal microglia and the number of neurons harboring intracellular amyloid-β (Aβ), but imparted no apparent effect on glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-positive astrocytes in 3xTg-AD mice. Following a protracted period of TNF-α overexpression, significant neuronal death as well as pronounced activation of microglia and leukocyte infiltration, were clearly evident specifically in the brains of 3xTg-AD mice, suggesting that TNF-α-related signaling cascades and the AD-related transgene products of 3xTg-AD mice cooperate in vivo to lead ultimately to neuronal death. Overall, these data point to a potentially significant role of TNF-α-directed processes in the progression of early human AD.

Materials and Methods

Transgenic Mice

Triple transgenic-AD (3xTg-AD) and non-transgenic (Non-Tg) mice were created as previously described.15 Six-month-old mice were used for in situ hybridization studies, while 2-month-old mice were used at the initiation of the virus vector transduction experiments. All animal housing and procedures were performed in compliance with guidelines established by the University Committee of Animal Resources at the University of Rochester.

Combined Immunohistochemistry and in Situ Hybridization

Six-month old 3xTg-AD and Non-Tg mice were sacrificed and perfused using 10% buffered neutral formalin, followed by 24-hour incubations in 10% formalin, 1× PBS, 20% sucrose, and 30% sucrose before mounting sections onto slides in RNase-free conditions. Both immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization was performed under rigorous RNase-free conditions throughout the procedure. For immunohistochemistry, slides were incubated in 5× PBS for 15 minutes, followed by two incubations of 1× PBS for 30 minutes each. Slides were then incubated in 0.15 mol/L phosphate buffer (PB) containing 1% H2O2 for 25 minutes. Following peroxidase quenching, slides were incubated in 0.15 mol/L PB containing 0.1% Triton-X 100 for 5 minutes and then moved to blocking solution containing 0.1% Triton-X 100, 0.1% normal goat serum, 0.5% bovine serum albumin, and RNase inhibitor (RNAsin, Promega, Madison, WI) for 3 hours with gentle rotation. Primary NeuN (1:100; Chemicon, Temecula, CA) or F4/80 antibody (1:100; Serotec, Raleigh, NC) was then added in blocking solution and incubated for 36 hours at 4°C. Slides were then washed thrice, 10 minutes each, in blocking solution before 2-hour incubation with a biotinylated anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:500, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) in blocking solution at room temperature (∼22°C). Two 5-minute washes in 0.15 mol/L PB were used to remove excess secondary antibody. Slides were incubated in an avidin-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase complex (Vector Labs) in 0.15 mol/L PB for 1.5 hours, followed by a wash in 0.15 mol/L PB for 3 × 5 minutes and H2O for 2 × 5 minutes before diaminobenzidine (DAB) development (Vector Labs) for 15 minutes. The slides were subsequently rinsed in distilled water (dH2O) and held under RNase-free conditions in 1× PBS before proceeding to in situ hybridization.

For in situ hybridization, slides were washed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes, followed by 3× PBS, 1× PBS, 1× PBS, and dH2O for 5 minutes each. Slides were then incubated in a 37°C bath of 1 μg/ml proteinase K (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) in Tris/EDTA, pH 8.0 for 30 minutes. Slides were washed twice for 1 minute each in 1× PBS before a 10-minute fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde and then a 1-minute 0.2% glycine treatment. Slides were washed briefly before 0.25% acetic anhydride treatment in 0.1 mol/L TEA twice for 10 minutes each. Slides were subsequently washed in 1× PBS for 5 minutes, and dehydrated through ethanol, before a 20-minute incubation in chloroform. Following delipidation, slides were incubated in 100% and 95% ethanol before air-drying for 45 minutes.

Anti-sense and sense TNF-α riboprobes were synthesized from a TOPO plasmid with T7 directing anti-sense and SP6 RNA polymerase directing sense riboprobe production. The mouse TNF-α probe consisted of bases 45 through 557 of the mRNA coding sequence. Riboprobe synthesis was conducted using an in vitro transcription system (Promega) and 35S-UTP (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) to generate probes with a specific activity of approximately 1 × 108 cpm/μg. Excess nucleotides were removed using the RNAid clean-up kit (QbioGene, La Jolla, CA). Anti-sense and sense hybridization probes were made by adding probe to a hybridization solution containing 50% formamide, 0.3 mol/L salts solution, 0.1 mol/L dithiothreitol, and 10% dextran sulfate. Incubation at 80°C for 10 minutes was performed before incubation on ice and reheating to 56°C. Labeled probe was maintained at 56°C until addition to slides, coverslipping, DPX (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) mounting media of the coverslip edges, and placement in a hybridization chamber at 56°C for 12 hours.

Coverslips were removed in 4× standard saline citrate with 0.1 mol/L dithiothreitol and then all slides were washed in 4 changes of 4× standard saline citrate with 0.1 mol/L dithiothreitol for 30 minutes each. Ethanol dehydration with 0.3 mol/L ammonium acetate was performed on slides before movement to a high stringency formamide/Tris-EDTA wash at 78°C. A 10-minute wash in 2× SSC was performed and slides were treated in a 20 μg/ml RNase A (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) bath. Slides were washed twice for 15 minutes each in RNase bath buffer, and once for 30 minutes in 2× standard saline citrate containing 0.01 mol/L β-mercaptoethanol. Lastly, slides were dehydrated with ethanol and dried for 1 hour before placing them against emulsion-coated film overnight. In a darkroom, slides were subsequently dipped in NTB emulsion (Kodak, Rochester, NY) at 43°C, dried for 2 hours, and placed at 4°C for 8 weeks for development.

Recombinant AAV Plasmid Construction

The pFBGR plasmid harbors a cytomegalovirus promoter-driven enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) gene flanked by inverted terminal repeats (pAAV-eGFP, kindly provided by Dr. Robert Kotin). Human tumor necrosis factor-α (hTNF-α) cDNA from pE4 (ATCC, Manassas, VA) was cloned into the pBSFBRmcs shuttle vector and subsequently into a modified pFBGR plasmid backbone devoid of the eGFP gene. This resultant plasmid was designated pAAV-TNFα. The pAAV-eGFP and pAAV-TNFα plasmids were transiently transfected into baby hamster kidney cells and transgene expression confirmed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) before viral packaging.

rAAV2 Vector Packaging

The pAAV-eGFP and pAAV-TNFα plasmids were separately transposed into DH10-BAC E. coli (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and DNA purified before transfection into SF9 cells to produce baculovirus and finally AAV vector particles according to previously published methodology.16 293A cells were transduced with either rAAV-TNFα or rAAV-eGFP to confirm TNF-α expression by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or to obtain titer information via flow cytometry. Titers were expressed as transducing units (TU) per ml.

Stereotactic Infusion of rAAV-TNFα and rAAV-eGFP

Recombinant AAV-TNFα or AAV-eGFP vectors or saline were stereotactically delivered into 2-month-old 3xTg-AD and Non-Tg mice in accordance with approved University of Rochester animal use guidelines. Mice were anesthetized with Avertin (300 mg/kg) and monitored throughout the stereotactic procedure to maintain a plane of surgical anesthesia. After positioning the mouse in a stereotactic apparatus (ASI Instruments, Warren, MI), the skull was exposed via a midline incision, and two burr holes were drilled bilaterally over the designated hippocampal coordinates (Bregma, −2.7 mm; lateral, 2.0 mm; ventral, 1.3 mm; and Bregma, −2.9 mm; lateral, 2.5 mm; ventral, 1.7 mm). A 33 gauge needle was gradually advanced to the desired depth during a 1.5-minute period. All injections were performed using a microprocessor controlled pump (UltraMicro-Pump; WPI Instruments, Sarasota, FL). A total of 2 μl (3.0 × 109 TU) per injection was delivered at a constant rate of 200 nl/min. A 3xTg-AD mouse cohort sacrificed at 6 months for histological analysis was injected with either rAAV-TNFα or rAAV-eGFP in the right hippocampus and saline in the left (n = 4 for rAAV-TNFα injected and n = 3 for rAAV-eGFP). To confirm results of intracellular Aβ42 immunohistochemistry (described below), a second cohort of 3xTg-AD mice was identically injected (n = 4). Non-Tg and 3xTg-AD mice (n = 6/group) sacrificed at 12 months of age for histological analysis were injected bilaterally with rAAV-TNFα and rAAV-eGFP. Mice assessed by quantitative real time reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis were injected bilaterally with either rAAV-TNFα or rAAV-eGFP according to the stereotactic coordinates detailed above (n = 4/group for rAAV-TNFα injected and n = 3 for rAAV-eGFP at the 6-month time point and n = 6/group for the 12-month time point). Following each injection, the needle was extracted over a 3-minute period. Incisions were closed using vicryl sutures, topical 5% lidocaine ointment (Fougera, Melville, NY) applied, and mice were allowed to recuperate in a heated recovery chamber before returning to their housing cage and the vivarium.

qRT-PCR Analysis

RNA was isolated from microdissected hippocampi of rAAV-TNFα or rAAV-eGFP mice with TRIzol solution (Invitrogen) at 6 and 12 months of age, which represent 4 and 10 months postvector infusion, respectively, as described previously.14 One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed using Applied Biosystems High-Capacity cDNA Archive Kit. An aliquot of cDNA (100 ng) was used to assess the levels of 19 or 15 targets per mouse at the 6- and 12-month time points, respectively. Each sample was analyzed in a standard PE7900HT quantitative RT-PCR reaction as previously described14 using a TaqMan Assay-on-Demand primer-probe sets in Microfluidic cards (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). An included 18S RNA primer-probe set served as the control to which all samples were normalized. The resultant data were analyzed using the ΔΔCT method, normalizing the rAAV-TNFα values to samples from rAAV-eGFP injected 3xTg-AD or Non-Tg mice, or data were normalized to Non-Tg mice when 3xTg-AD mice were compared to the Non-Tg group in rAAV-TNFα specific differences. To determine statistical significance, Student’s t-test or analysis of variance with Bonferroni posthoc tests were performed, as indicated. For analysis of human APPSwe, PS1M146V, or TauP301L transgene expression and human TNF-α expression derived from the rAAV vector, 25 ng cDNA was analyzed in a 7300 quantitative PCR machine using a TaqMan Assay-on-Demand primer probe set to human APP, PS1, Tau or TNF-α (Applied Biosystems).

Immunohistochemistry

At 6 or 12 months of age, injected 3xTg-AD and Non-Tg mice were sacrificed and brains were fixed by transcardiac perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 mol/L PB. The brains were removed, postfixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 mol/L PB, transferred to a solution of 20% sucrose in PBS overnight, and subsequently placed in a solution of 30% sucrose in PBS. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on 30-μm free-floating brain sections using the following antibodies: MAB610 at 25 μg/ml (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) to detect hTNF-α; anti-GFP at 1:2000 (Invitrogen) to detect eGFP; anti-amyloid precursor protein A4, corresponding to the NPXY motif of hAPP (Clone Y188; AbCam, Cambridge, MA, 1:750); anti-hAPP/amyloid-β reactive to amino acid residues 1 to 16 of β-amyloid (6E10; Covance, Berkeley, CA; 1:1000); anti-amyloid β 1-42 clone 12F4 reactive to the C-terminus of β-amyloid and specific for the isoform ending at amino acid 42 (Covance/Signet, Berkeley, CA, 1:1000); anti-amyloid β 1-42 polyclonal antibody for intracellular amyloid-β staining (Invitrogen, formerly Biosource, Hopkinton, MA; 1:1000); AT180 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) to detect hyperphosphorylated tau at 1:200; F4/80 at 1:500 (Serotec, Raleigh, NC) to stain for microglia/macrophages; GFAP at 1:1000 (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) for astrocytes; and NeuN at 1:500 (Chemicon) to detect mature neurons.

The Aβ, APP/Aβ, AT180, F4/80, GFAP, and NeuN immunohistochemical analyses were performed using DAB development. Sections were washed three times for 5 minutes each to remove cyroprotectant, then three times for 30 minutes each in 0.15 mol/L PB. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubation in 0.15 mol/L PB containing 3% H2O2 for 25 minutes. Sections being processed for Aβ or APP/Aβ visualization were treated at this stage with 3% methanol. Sections were subsequently washed twice for 5 minutes each with 0.15 mol/L PB. Staining with 12F4 required epitope retrieval treatment using 90% formic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 minutes at room temperature, followed by two washes for 5 minutes each with PB. Tissue was permeabilized with 0.15 mol/L PB + 0.4% Triton-X 100 (Sigma-Aldrich). Non-specific interactions were blocked by incubation of the sections for 1 hour at 22°C with 0.15 mol/L PB + 0.4% Triton-X 100 + 10% normal goat serum (Gibco/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody diluted in 0.15 mol/L PB + 0.4% Triton-X 100 + 1% normal goat serum. Samples were washed three times for 10 minutes each with 0.15 mol/L PB + 0.4% Triton-X 100 + 1% normal goat serum, before addition of biotinylated species-specific secondary antibody IgG (H+L) generated in goat (1:1000; Vector Labs), diluted in 0.15 mol/L PB + 0.4% Triton-X 100 + 1% normal goat serum. Excess secondary antibody was washed away with 0.15 mol/L PB. A conjugate was formed with bound secondary and avidin:biotinylated complex in an enzyme reaction using 2 μl of solution A and 2 μl of solution B from a Vectastain ABC kit per ml of 0.15 mol/L PB (Vector Labs). Sections were developed using a DAB peroxidase kit, according to manufacturer’s instructions for nickel enhancement (Vector Labs) and mounted on slides for visualization by microscopy.

Immunocytochemistry was performed for enhanced GFP or hTNF-α, or in combination with NeuN or GFAP cell markers using fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies. Tissue sections were washed with PBS to remove cyroprotectant, as above. Sections were permeabilized with PBS + 0.1% Triton-X 100 for 5 minutes and then incubated with blocking serum (PBS + 0.1% Triton-X 100 and 10% normal goat serum) for 1 hour at 22°C. Primary antibody combinations were diluted into PBS + 0.1% Triton-X 100 + 0.1% normal goat serum overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed three times 10 minutes each and then incubated in appropriate secondary antibodies for 2 hours at 22°C. Anti-mouse Alexa 647 at 1:500 (Invitrogen) was used for hTNF-α immunohistochemistry, anti-rabbit Alexa 488 at 1:500 (Invitrogen) was used for eGFP immunohistochemistry. When appropriate, preconjugated (Alexa 568 Invitrogen) NeuN or a Cy3 GFAP (Sigma-Aldrich) was then applied and sections were incubated overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed with 0.1 mol/L PBS, mounted, and coverslipped with the aqueous mounting media Mowiol. Imaging was performed using a Zeiss Scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Minneapolis, MN).

For intracellular Aβ1-42 staining, a microwave/Target buffer (Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) epitope retrieval method was used as described in17; briefly the brain sections were washed with 0.15 mol/L PB for 2 hours to remove the cryoprotectant, then incubated with 3% H2O2 in 0.15 mol/L PB for 20 minutes to quench endogenous peroxidase activity before mounting sections onto slides (Superfrost Plus, VWR International, West Chester, PA). The Target buffer was heated to 98°C in a microwave (GE, Louisville, KY), and the slides submerged into the buffer and heated in the microwave, twice for 3 minutes at 450 W, and allowed to stand for 5 minutes between each microwave step. The sections were washed and permeabilized in 0.15 mol/L PB and 0.4% Triton X-100, followed by blocking in 0.15 mol/L PB + 0.4% Triton X-100 + 10% normal goat serum. After blocking, the sections were incubated in 0.15 mol/L PB + 0.4% Triton X-100 + 1% normal goat serum, with an Aβ1-42 specific primary antibody (polyclonal anti-amyloid β 1-42; Invitrogen). The sections were washed with 0.15 mol/L PB, and followed by an incubation with the appropriate secondary biotin-conjugated secondary antibody (Vector Labs; 1:1000) in 0.15 mol/L PB + 0.4% Triton X-100 + 1% normal goat serum. The sections were washed with 0.15 mol/L PB + 0.4%Triton X-100 + 1% normal goat serum, and incubated in the avidin-biotin complex (Vector Labs Vectastain ABC System as per manufacturer’s protocol). Sections were washed in 0.15 mol/L PB followed by rinses in dH2O. The sections were developed with nickel-enhanced DAB (Vector Labs), dried, and coverslipped.

All immunohistochemically stained sections were viewed using an Olympus AX-70 microscope, and DP71 camera, and controller software (Olympus, Center Valley, PA). Positive cells were visualized using an Olympus AX-70 microscope equipped with a motorized stage (Olympus, Melville, NY) and the SPOT camera and software (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI).

Nuclear Fast Red Counterstain and Enumeration of Cell Nuclei in Mouse Hippocampus

Following F4/80 DAB immunohistochemistry, 12-month time-point sections were incubated in Nuclear Fast Red counterstain (Vector Labs) for 30 minutes, followed by a 10-minute destaining step in dH2O, and alcohol dehydration before sealing under coverslips. Red nuclei were visualized in CA1 pyramidal and dentate gyrus (DG) granule cell layers, which predominately contain neurons, using an Olympus AX-70 microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY) connected to a SPOT camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). The MCID Elite 6.0 Imaging Software (Imaging Research, Inc.) was used for semiquantitative analysis. Three sections from 3.7 mm and 3.9 mm posterior from Bregma were analyzed from each region and each mouse (n = 6 for 3xTg-AD mice and n = 4 for Non-Tg mice). A defined region encompassing 175,000 μm2 was analyzed in each counting frame. All nuclei enumerated were negative for the microglial marker F4/80.

CD45 Immunohistochemistry

CD45 immunohistochemical analysis of brain sections from rAAV vector-injected 12 month-old 3xTg-AD and Non-Tg mice was performed directly on slides. Sections were washed three times for 5 minutes each to remove cyroprotectant, then three times for 30 minutes each in 0.15 mol/L PB. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubation in 0.15 mol/L PB containing 3% H2O2 for 25 minutes. Sections were subsequently washed twice for 5 minutes each with 0.15 mol/L PB. Tissue was permeabilized with 0.15 mol/L PB + 0.4% Triton-X 100 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 minutes before mounting on slides. Slides were then dried for 10 minutes on a slide warmer at 42°C and then repermeabilized for 15 minutes. Non-specific interactions were blocked by incubation of the sections for 1 hour at 22°C with PB + 0.4% PB Triton-X 100 + 10% normal goat serum (Invitrogen). Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with 500 μl solution of anti-CD45 MCA1031G (Serotec) antibody diluted in PB + 0.4% Triton-X 100 + 1% normal goat serum. Samples were washed three times for 10 minutes each with PB + 0.4% Triton- X 100 + 1% normal goat serum before addition of biotinylated anti-rat secondary antibody IgG generated in goat (1:1000; Vector Labs), diluted in PB + 0.4% Triton-X 100 + 1% normal goat serum. Excess secondary antibody was washed in 0.15 mol/L PB for 3 × 10 minutes. Sections were developed using a DAB peroxidase kit, according to manufacturer’s instructions for nickel enhancement (Vector Labs) for 4 minutes and allowed to dry before sealing and visualization by microscopy. CD45-positive cells were visualized in CA1 pyramidal and DG granule cell layers. Numbers of cells were enumerated using an Olympus AX-70 microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY) and MCID Elite 6.0 Imaging Software (Imaging Research, Inc.) Three sections from −3.7 mm and −3.9 mm relative to Bregma were analyzed from each region and each mouse (n = 4 for 3xTg-AD mice and n = 6 for Non-Tg mice). Three to six images were captured per section at 20× magnification and positive cells were identified in each region encompassing 985,000 μm2. Data are expressed as an average number of cells/area. Two-way analysis of variance was performed to determine significance of chronic TNF-α expression in 3xTg-AD mice compared to Non-Tg mice. Student’s t-test revealed significant differences between rAAV-TNFα and rAAV-eGFP injected hemispheres in 3xTg-AD and Non-Tg mice.

Imaging and Image Processing

For all figures with photomicrographic images, image processing consisted only of brightness and contrast alterations applied identically over all images within an experimental data set using Photoshop CS3 (Adobe Systems, Inc., San Jose, CA). No other image processing changes were made except in Figure 1 where photomicrographs of a given section were captured at two planes, one to visualize immunohistochemically stained cells and the other to visualize the developed emulsion grain layer from in situ hybridization, and images were overlaid using Photoshop CS3.

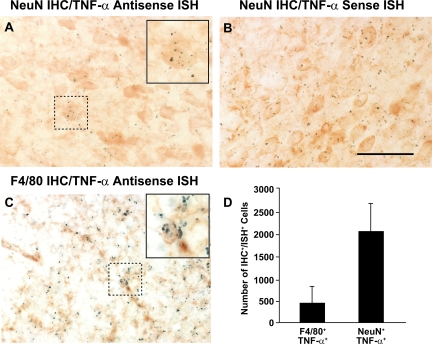

Figure 1.

Neurons in the 3xTg-AD mouse brain endogenously express TNF-α. Combined immunohistochemistry for neuronal nuclear antigen (NeuN) or microglia/macrophages (F4/80) and in situ hybridization specific for mouse TNF-α was performed on brain sections from 6-month-old 3xTg-AD mice (n = 4) that were perfused and sectioned under RNase-free conditions. Radiolabeled 35S-labeled riboprobes for an anti-sense TNF-α (A and C) and a sense TNF-α sequence (negative control, panel B) were used for in situ hybridization at a specific activity of 1 × 108 cpm/μg Sections were subsequently incubated with an anti-NeuN or anti-F4/80 antibody to stain neurons and microglia/macrophages, respectively. Positive TNF-α signal via in situ hybridization was indicated by at least 15 clustered grains that colocalized to single immunohistochemically NeuN (A) or F4/80-expressing cells (C). Dotted boxes outline areas magnified in insets shown in (A) and (C). The numbers of F4/80+/TNF-α+ and NeuN+/TNF-α+ cells were enumerated using quantitative image analysis and are depicted graphically in (D). Error bars indicate SD. Scale bar =50 μm.

Results

Neurons Endogenously Express TNF-α in the 3xTg-AD Brain

Neurons have been shown to express TNF-α in response to a number of brain-related injury models that elaborate an accompanying inflammatory response,11,12,13 but the impact of neuronally derived TNF-α on neurons themselves or on other proximal cell types is relatively underappreciated in the setting of neurodegeneration. To definitively address whether neurons in the 3xTg-AD mouse brain express TNF-α, we performed combined immunohistochemistry to identify neurons or microglia and in situ hybridization for murine TNF-α on brain sections derived from 6-month-old 3xTg-AD mice. Co-localization of mouse TNF-α mRNA, as depicted by emulsion grain accumulation within NeuN+ neurons and F4/80+ microglia/macrophages in sections incubated with the 35S-labeled anti-sense TNF-α probe, was observed in the entorhinal cortex (Figure 1, A and C, respectively). Incubation of adjacent brain sections with a radiolabeled mouse TNF-α sense probe revealed no significant grain accumulation in either of these regions (Figure 1B), indicating the specificity of the mouse TNF-α transcript signal detected with the anti-sense probe. Quantitative image analysis was performed on each section where positive TNF-α transcript signal via in situ hybridization was indicated by at least 15 clustered silver grains that co-localized to individual NeuN+ or F4/80+ cells (Figure 1D). Abundant numbers of NeuN+/TNF-α+ cells were detected in the brains of 6 month-old 3xTg-AD mice, indicating that neurons represent a major source of this potent cytokine.

Development of a Recombinant Adenoassociated Virus Vector to Specifically Overexpress Human TNF-α in Mouse Neurons

Given the early expression of TNF-α in the 3xTg-AD mice, we reasoned that by producing higher levels of this pro-inflammatory cytokine within neurons before the emergence to overt AD pathology, we could address its role in pathogenesis. To this end, we subsequently assessed the potential role that constitutively expressed TNF-α may play on AD-related pathological signatures in 3xTg-AD mice. Two recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vectors were constructed: one expressing human TNF-α (rAAV-TNFα) and a second expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (rAAV-eGFP) as a negative control. The individual transgenes were transcriptionally controlled by the human cytomegalovirus promoter (Figure 2A). The vectors were packaged into serotype 2 virions using a baculovirus-based rAAV preparation method to achieve neuron-directed expression.16 The human TNF-α cDNA was chosen to facilitate immunological differentiation from endogenous mouse TNF-α, and the human homolog has been shown to function similarly to the murine counterpart in mouse models.18 To confirm that rAAV-TNFα was expressing high levels of secreted hTNFα, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was performed on supernatants from pAAV-TNFα-transfected baby hamster kidney cells and rAAV-TNFα-transduced 293A cells (Figure 2B).

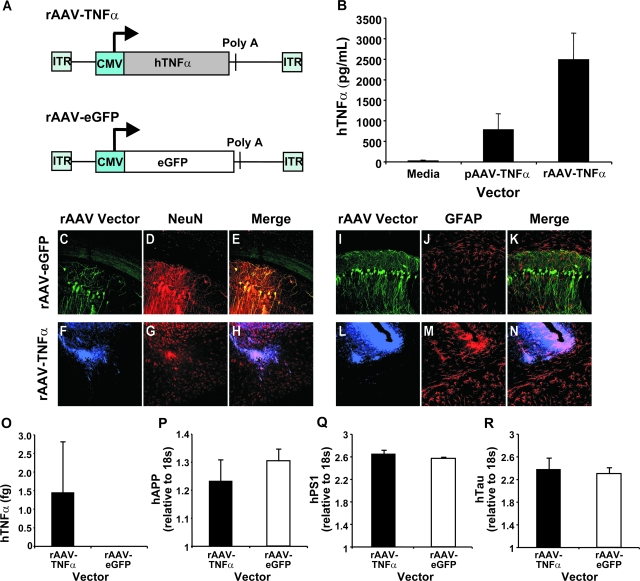

Figure 2.

Vector construction and characterization of rAAV vectors expressing hTNFα and eGFP. Two rAAV vectors were constructed: one expressing human TNF-α (rAAV-TNFα) and a second expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (rAAV-eGFP) as a negative control. The individual transgenes were placed under the transcriptional control of the human cytomegalovirus promoter (A). Baby hamster kidney cells were transfected with pAAV-TNFα or 293A cells transduced with 109 particles of rAAV-TNFα. A human TNF-α enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was performed on cell culture supernatants 72 hours after transduction according to manufacturer’s instructions to determine the concentration (pg/ml) of human TNF-α product by each vector tested (B). A cohort of 3xTg-AD mice subsequently injected with 3 × 109 TU of rAAV-egfp (ipsilateral)/saline (contralateral) or rAAV-TNFα (ipsilateral)/saline (contralateral) were sacrificed 4 months postinjection, perfused, and sectioned coronally at 30 μm. Sections were co-incubated with a primary antibody specific for either eGFP (green signal; C, E, I, K) or human TNF-α (blue signal; F, H, L, N) and primary antibodies specific for neurons (NeuN; D, E, G, H; red signal) or astrocytes (GFAP; J, K, M, N; red signal). Following incubation with a designated set of secondary antibodies, photomicrographs of the transduced CA1 subregion of the hippocampal formation were captured by 2-color confocal microscopy (n = 3 per vector). Overlapping signals appear yellow in color for eGFP (E and K), or pink in color for human TNF-α (H and N). A separate set of 3xTg-AD mice (n = 4) were injected intrahippocampally with 3 × 109 TU of rAAV-eGFP or rAAV-TNFα, sacrificed 4 months postinjection, hippocampal tissue microdissected, and mRNA isolated and processed for quantitative real-time RT-PCR using a human TNF-α-specific TaqMan fluorogenic primer/probe set (O). These mRNA samples were subsequently analyzed via real-time RT-PCR using a human APPSwe, human PS1M146V, or human TauP301L-specific TaqMan fluorogenic primer/probe set to determine whether rAAV-TNFα transduction resulted in transcriptional up-regulation of the resident transgenes (P, Q, or R, respectively). Error bars in B, O, P, Q, and R indicate SD. C-N: 40 × magnification.

The rAAV-TNFα vector and rAAV-eGFP control vector were stereotactically infused into the CA1 layer of the 3xTg-AD and Non-Tg mouse hippocampus at 2 months of age. At this early time point, 3xTg-AD mice do not harbor detectable hAPP/Aβ as determined by immunohistochemical methods,14 and therefore, this age represented a pre-pathological stage from which to test a TNF-α mediated response. At 6 months of age, a subset of vector-injected mice were sacrificed and assessed for cell type expression specificity of the hTNF-α and eGFP transgene products by co-immunocytochemistry. rAAV-eGFP transduction led to a predominantly neuron-specific expression pattern along the transduced pyramidal layer of the hippocampal CA1 subregion, as evidenced by overlap in NeuN- and eGFP-positive signals (Figure 2, C–E), with the non-secreted reporter gene product observable throughout the cell body, dendrites and axons. Co-staining for GFAP-positive astrocytes and eGFP did not result in signal co-registration (Figure 2, I–K). This neuronal preference is consistent with serotype-2 rAAV vector-mediated gene delivery.19,20,21 Hippocampally targeted rAAV-TNFα was detected in CA1 neurons (Figure 2, F–H). However, TNF-α is a secreted transgene product and significant overlap of TNF-α- and GFAP-positive signals could be observed (Figure 2, L–N). Expression of rAAV vector-driven hTNF-α in vivo was further verified by qRT-PCR (Figure 2O). Notably, rAAV-TNFα transduction of the 3xTg-AD mouse hippocampus did not induce an increase in hAPP, hPS1, or hTau transgene levels at this time point (Figure 2, P, Q, R, respectively), indicating that any effects arising as a result of rAAV vector-derived hTNF-α could not be attributed to enhanced expression of the resident human transgenes in 3xTg-AD mice.

Evidence for Enhanced Microglial/Macrophage Activation and Premature AD-Related Pathologies in rAAV-TNFα Transduced 3xTg-AD Mouse Hippocampus Four Months Post-Transduction

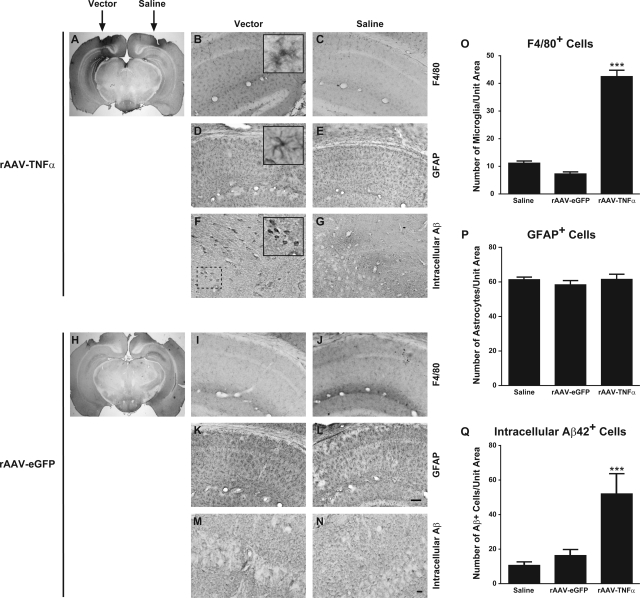

Microglia and astrocytes are known to participate in inflammatory processes attending AD pathophysiology and may produce and respond to disease-associated TNF-α.3 Previously, we had identified a regional and age-dependent increase in numbers of F4/80+ microglial cells in the brains of 3xTg-AD mice that correlated with an increase in endogenous TNF-α expression.14 This observation suggested microglial activation enhancement and/or recruitment could be occurring in response to local TNF-α expression. To determine the cell type(s) responding to neuronally derived TNF-α, we assessed the extent of microglial and astrocytic cell marker staining in the hippocampi of 3xTg-AD mice that had received rAAV-TNFα and rAAV-eGFP. We observed marked microglial activation as a result of rAAV-TNFα transduction (Figure 3A, B, O), while no apparent alteration in F4/80 staining patterns or intensity was detected in mice receiving the rAAV-eGFP control virus (Figure 3, H, I) or saline injections (Figure 3, C, J, O). In adjacent brain sections, GFAP staining patterns for astrocytes were indistinguishable between rAAV-TNFα and rAAV-eGFP injected groups (Figure 3, D, K, P). Moreover, the intensities of GFAP immunopositivity in sections from both treatment groups were similar to saline-injected 3xTg-AD controls at 6 months of age (Figure 3, E, L, P). These results indicated an anatomically restricted activation of cells comprising the microglia/macrophage lineage by neuronally derived TNF-α, a finding supportive of our previous observations correlating region-specific microglial activation with endogenous TNF-α expression enhancement in 3xTg-AD mice.

Figure 3.

rAAV-TNFα delivery results in selective localized enhancement of F4/80+ microglial cell staining and intracellular Aβ42 accumulation four months post-transduction. Two month-old 3xTg-AD mice were stereotactically injected with either rAAV-TNFα and saline (A–G) or rAAV-eGFP and saline (H–N) and were sacrificed at 6 months of age (n = 4 per group). Mice were perfused and brains were removed and sectioned at 30 μm for immunohistochemical staining for either microglia/macrophages using an F4/80 marker-specific antibody (A–C and H–J), for astrocytes using a GFAP-specific antibody (D, E, K, L), or for intracellular Aβ42 using an Aβ1–42 specific antibody (F, G, M, N). Sections were subsequently processed using DAB histochemistry and photomicrographs were obtained at original magnification ×1.25 (A and H), ×20 (B–E and I–L), or ×40 (F, G, M, N). Insets in (B), (D), and (F) represent digitally magnified images of the respective photomicrograph for better visualization of stained cell morphology. Scale bars in (L) and (N) = 50 μm. Quantitative image analyses for cells/pathologies staining positive for F4/80 (O), GFAP (P), and intracellular Aβ42 (Q) were performed on each brain and presented in histogram format. Error bars indicate SD. ***P < 0.001 as determined by one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni posthoc analysis using the saline-injected hemisphere as the baseline comparator.

Liao and colleagues previously demonstrated in vitro that TNF-α, as well as other pro-inflammatory cytokines, could enhance γ-secretase-mediated cleavage of APP via JNK-dependent signaling, leading to increased elaboration of Aβ.22 Although controversial, the accumulation of intracellular Aβ in the setting of AD has been put forth as a potential contributor to synaptic dysfunction and learning/memory deficits observed during early disease pathogenesis (reviewed by23). Given the reported effects of TNF-α on APP processing and the possible early role of intracellular Aβ in neuronal dysfunction, it was plausible that rAAV vector-mediated overexpression of TNF-α in 3xTg-AD mice led to marked accumulation of intracellular Aβ peptides in regions proximal to vector infusion. Using an immunocytochemical staining method optimized for visualization of intracellular Aβ42 peptide,17 we detected significant enhancement of intracellular Aβ accumulation in brains of 3xTg-AD mice receiving rAAV-TNFα (Figure 3, F and Q) as compared to rAAV-eGFP (Figure 3, M and Q) and saline-treated control mice (Figure 3, G, N, Q).

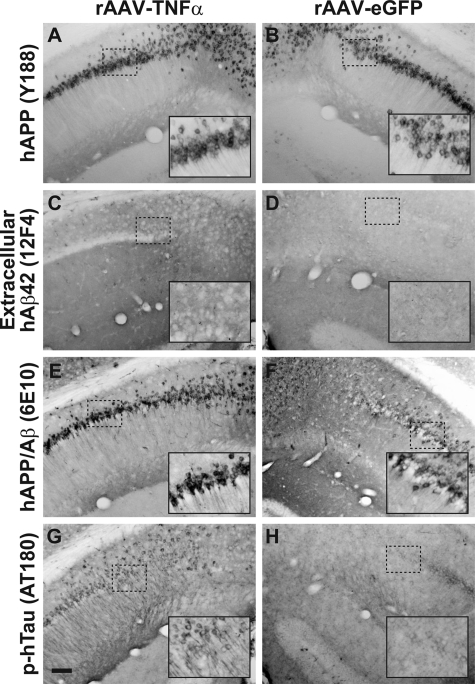

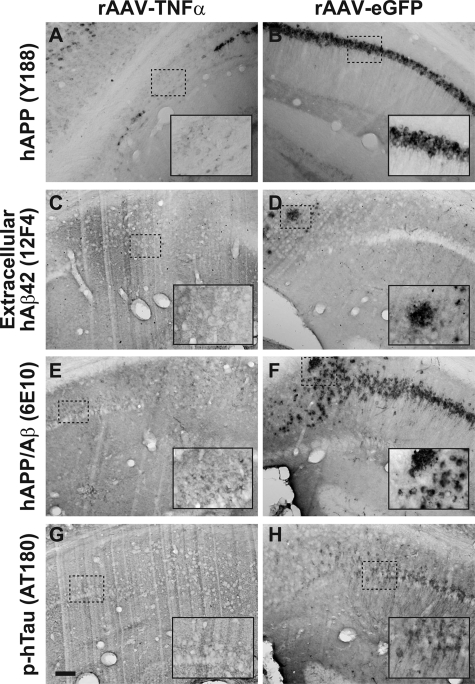

Immunohistochemical examination of these 6-month-old 3xTg-AD mice for other AD-related pathologies revealed specific differences in rAAV-TNFα transduced mice as compared to rAAV-eGFP control vector-infused mice. Consistent with our transcript analyses illustrated in Figure 2, staining for hAPP using the Y188 antibody further confirmed that the hAPP transgene product expression pattern is unaffected by transduction with either rAAV-TNFα or rAAV-eGFP (Figure 4, A and B). Moreover, assessment of extracellular Aβ42 accumulation demonstrates that TNF-α overexpression for 4 months does not lead to exacerbated plaque pathology (Figure 4, C and D). However, staining intensities for sections incubated with the 6E10 antibody, which recognizes both hAPP and hAβ, or the phospho-Tau epitope-specific antibody AT180 were notably enhanced in mice intrahippocampally infused with rAAV-TNFα (Figure 4, E–H). These latter findings are consistent with the enhancement in intracellular Aβ in the rAAV-TNFα injected 3xTg-AD mice, suggesting that 4 months of neuronally derived TNF-α expression had incited a pathological cascade within the vector-transduced zone.

Figure 4.

Four months of chronic TNF-α expression in 3xTg-AD hippocampus leads to subtle alterations in AD-related pathologies. 3xTg-AD mice injected with rAAV-TNFα (A, C, E, G) or rAAV-eGFP (B, D, F, H) at 2 months of age were sacrificed at 4 months postinjection and brains were sectioned at 30 μm and analyzed for the presence of human APP transgene product (A and B), extracellular human Aβ1–42 (C and D), hAPP/Aβ (E and F), and a hyperphosphorylated epitope of hTau (G and H) via immunohistochemistry with DAB development. The inset in each panel represents a sixfold magnification of the region outlined by the dotted box for more optimal visualization of stained pathological hallmarks. Scale bar in (G) = 100 μm.

Chronic rAAV-TNFα Enhances a Subset of Transcriptional Targets Specifically in 3xTg-AD Mice

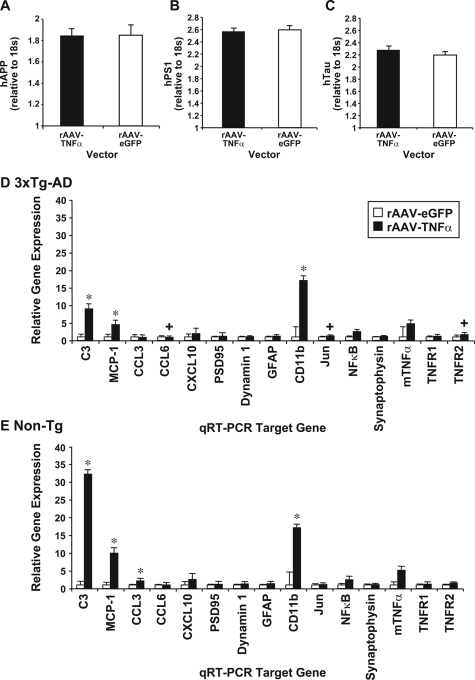

Given that 4 months of neuron-expressed TNF-α in the 3xTg-AD mice had led to marked changes in inflammatory state and early pathology, a separate cohort of identically treated animals was analyzed at 12 months of age, a time when AD-related processes are quite evident in 3xTg-AD mice.15 To assess transcriptional targets that are expressed at a time point following a more protracted period of TNF-α expression, we performed qRT-PCR on mRNA isolated from microdissected hippocampi of rAAV-TNFα and rAAV-eGFP injected 3xTg-AD and Non-Tg mice 10 months post-transduction (12 months of age). Transcript levels of the individual transgenes harbored by 3xTg-AD mice were unaffected by either rAAV vector infusion (Figure 5A–C). We observed that 3xTg-AD and Non-Tg mice injected with rAAV-TNF-α exhibited significant up-regulation in C3 component of complement, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and CD11b when compared to rAAV-eGFP injected counterparts (Figure 5, D and E). When rAAV-TNF-α injected 3xTg-AD mice were compared to rAAV-TNFα injected Non-Tg mice, we observed that the 3xTg-AD cohort expressed enhanced TNFRII and Jun transcript levels. These two targets are well characterized in signaling cascades that promote pro-apoptotic responses. Additionally, enhanced CCL6 chemokine expression was observed specifically in 3xTg-AD mice (Figure 5D), suggesting that microglial recruitment was sustained at this later time point post-rAAV vector delivery.

Figure 5.

Chronic expression of TNFα reveals transcript level differences between 3xTg-AD and Non-Tg mice. Hippocampi were dissected from 3xTg-AD and Non-Tg mice injected with rAAV-TNFα or AAV-eGFP at 12 months of age (n = 6). RNA was extracted and cDNA was synthesized using Applied Biosystems High-Capacity cDNA Archive kit. Samples were analyzed by quantitative real-time RT-PCR for steady-state expression levels of the transcripts derived from the three resident transgenes in 3xTg-AD mice: human APPSwe (A), human PS1M146V (B), and human TauP301L (C). A separate 100-ng sample for each transduced 3xTg-AD and Non-Tg mouse was loaded onto Microfluidic Cards (Applied Biosystems) and qRT-PCR was performed. rAAV-TNFα values are compared to rAAV-eGFP control samples and data are expressed as fold-change for 3xTg-AD (D) and Non-Tg mice (E). *P < 0.05 as assessed by two-way analysis of variance and Bonferroni posthoc test for intragenotype comparisons. Additional intergenotype comparisons were performed between rAAV-TNFα injected Non-Tg and 3xTg-AD mice with one-way analysis of variance to decipher differences in transcript expression. +P < 0.05; error bars represent the SD of the ΔCT values.

Chronic TNF-α Exposure Leads to AD-Related Neuronal Death and Extensive Microglial Activation

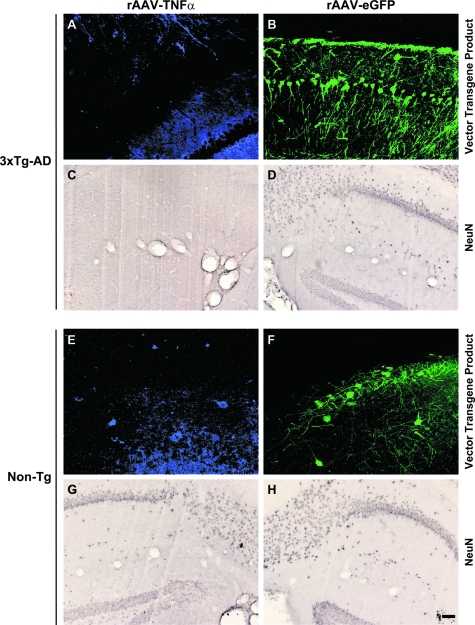

In light of the finding that rAAV-TNFα treated mice exhibited enhanced TNFRII and Jun transcript expression, we sought to determine the potential neurotoxic effects TNF-α may be exacting over the protracted period of expression. Immunocytochemistry was performed for hTNF-α, eGFP, or neuron-specific nuclear protein (NeuN) on brain sections from the transduced 12-month-old 3xTg-AD and Non-Tg mice described above. Mice from all treatment groups harbored immunocytochemically detectable hTNF-α and eGFP, indicating that the rAAV vectors continued to express these transgenes at 10 months post-transduction (Figure 6A, B, E, F). Interestingly, 3xTg-AD mice injected with rAAV-TNFα exhibited pronounced NeuN-positive cell loss (Figure 6C) at the injection site and proximally located DG (Figure 6C), whereas identically injected Non-Tg and rAAV-eGFP treated mice exhibited typical NeuN staining patterns (Figure 6, D, G, H). This finding suggested that the effect of TNF-α overexpression alone was insufficient, but rather required the coincident expression of one or all of the pathogenic transgene products expressed by 3xTg-AD mouse neurons.

Figure 6.

Loss of NeuN-positive neurons specifically in 3xTg-AD mice injected with rAAV-TNFα indicates a role for TNF-α in AD-related neurotoxicity. Two month-old 3xTg-AD mice (A–D) and Non-Tg (E–H) control mice injected with rAAV-TNFα (A, C, E, G) or rAAV-eGFP (B, D, F, H) were sacrificed at 12 months of age, and brains were sectioned at 30 μm and analyzed for the expression of TNF-α (blue signal) or eGFP (green signal) by fluorescence immunocytochemistry and for the presence of NeuN-positive neurons via immunohistochemistry with DAB development. Photomicrographs of the injected hippocampal CA1 area were obtained (n = 6 per group). Scale bar in (H) = 50 μm.

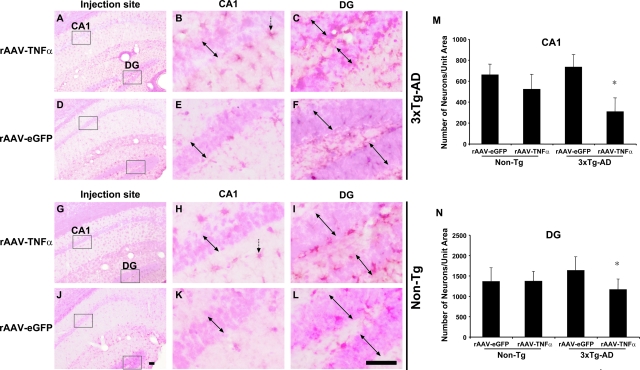

Because it was possible that chronic TNF-α expression in 3xTg-AD mouse brain could result in the down-regulation of NeuN protein expression and not necessarily neuronal loss, a histochemical method was used to further confirm the demise of neurons in the rAAV-TNFα transduced CA1 and proximal DG layers. Nuclear fast red staining was used in conjunction with F4/80 immunohistochemistry to visualize the extent of microglial activation in proximity to regions of putative neuronal loss. (Figure 7A–L). Patches of cell loss were readily apparent specifically in CA1 and DG regions of 3xTg-AD mice injected with rAAV-TNFα (Figure 7, A, B, C). No appreciable neuronal loss was visible in rAAV-TNFα injected non-transgenic mice or in rAAV-eGFP injected mice of either genotype, depicted by densely packed groups of neurons in the CA1 and DG layers (Figure 7, D–L). The observation of no appreciable cell loss in the rAAV-TNFα injected Non-Tg mice underscores the specificity for this phenomenon in requiring the co-expression of one or more of the AD-related transgene products and the pro-inflammatory cytokine. These qualitative results were further substantiated by enumerating the number of Nuclear Fast Red-positive nuclei at the injection site in each cohort. While the numbers of intact nuclei in rAAV-TNFα and rAAV-eGFP transduced CA1 and DG of Non-Tg mice were similar, there was a 42% reduction in the number of nuclei in the CA1 pyramidal layer and a 29% reduction in the DG granule cell layers of 3xTg-AD mice injected with rAAV-TNFα in comparison to identical hippocampal subfields of the rAAV-eGFP control group (Figure 7, M and N).

Figure 7.

Neuronally derived TNF-α induces heightened chronic microglial activation and contributes to neuronal loss in the CA1 and dentate gyrus of 3xTg-AD mice following 10 months of chronic cytokine expression. 3xTg-AD (A–F) and Non-Tg (G–L) mice stereotactically injected with either rAAV-TNFα (A–C and G–I) or rAAV-eGFP (D–F and J–L) were sacrificed at 10 months postinjection, and brains were sectioned at 30 μm and analyzed for the presence of F4/80-positive microglia via immunohistochemistry with DAB development and a subsequent Nuclear Fast Red counterstain. Photomicrographs of the injected hippocampi were obtained at original magnification ×10 (A, D, G, J). The CA1 (B, E, H, K) and DG regions (C, F, I, L) of the hippocampus were further magnified sixfold for more optimal visualization of stained microglia (brown/purple) and nuclei (red) in regions outlined with boxes. Double-headed arrows depict the boundaries of the pyramidal and granule layers of the CA1 and DG, respectively. Single-headed vertical arrows point to representative F4/80-positive microglia. Scale bars = 50 μm. Nuclear Fast Red-stained nuclei residing in the injected CA1 (M) and proximal DG layers (N) were enumerated (*P < 0.05 as determined by Student’s t-test when compared to rAAV-eGFP values). Error bars indicate SD.

rAAV-TNF-α Expression in the 3xTg-AD Hippocampus Leads to Robust CD45-Positive Cell Infiltration that is Not Evident in Identically Treated Non-Tg Mice

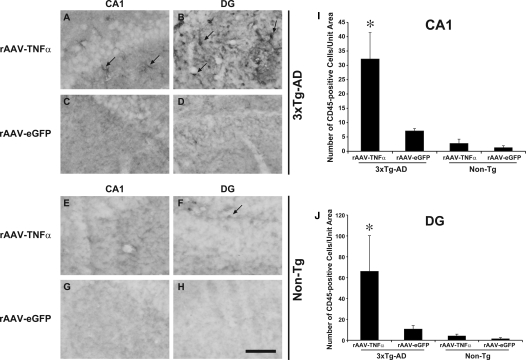

Coincident with significant neuronal nuclei loss in the hippocampi of 3xTg-AD mice stereotactically injected with rAAV-TNFα, we observed increased numbers of Nuclear Fast Red-positive small nuclei in the proximity of the microvasculature and within brain parenchyma specifically in this cohort of mice (data not shown), suggesting these cells represent an infiltrating population of peripheral origin. Infiltrating immune cells, including neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes have all been implicated in neurodegenerative disease processes and brain injury (reviewed by24), and to that end may contribute to the marked neuron loss observed in rAAV-TNFα injected 3xTg-AD mice. To address this possibility, we performed CD45 immunohistochemistry on brain sections from these mice to assess the numbers of infiltrating leukocytes, where CD45 is a protein tyrosine phosphatase expressed on cells comprising the hematopoietic lineage, excluding erythrocytes and platelets.25 Quantitation of CD45-positive cells revealed that the dentate gyrus and the CA1 region of the hippocampus harbored significantly higher numbers of infiltrating leukocytes specifically in 3xTg-AD mice injected with rAAV-TNFα (Figure 8). Fewer CD45-positive cells were detected in identically treated Non-Tg mice or in either genotype infused with the control vector, rAAV-eGFP, indicating that the combination of chronic TNF-α expression and AD-related pathogenic protein expression in the context of rAAV-TNFα treated 3xTg-AD mice results in enhancement of peripheral cell infiltration, microglial cell activation, and neuronal death.

Figure 8.

Chronic TNF-α expression leads to a significant and specific enhancement in the numbers of CD45-positive cells at the vector infusion site in 3xTg-AD mice. 3xTg-AD (A–D) and Non-Tg (E–H) mice stereotactically injected with either rAAV-TNFα (A, B, E, F) or rAAV-eGFP (C, D, G, H) were sacrificed at 10 months post injection, and brains were sectioned at 30 μm and analyzed for the presence of CD45-positive cells at the vector-infusion sites via immunohistochemistry with DAB development. Arrows point to representative CD45-positive cells. CD45-positive cells residing in the injected CA1 (I) and proximal DG layers (J) were enumerated (*P < 0.002 and *P < 0.02 respectively, as determined by Student’s t-test when compared to rAAV-eGFP values). Error bars indicate SD.

Long-Term TNF-α Exposure Leads to a Decrease in Aβ Peptide Accumulation and tau Hyperphosphorylation in Hippocampi of 3xTg-AD Mice Presumably Due to Loss of AD Transgene-Expressing Neurons

To determine the effect of chronic hTNF-α-mediated inflammatory processes on the evolution and severity of AD-related pathologies, we assessed rAAV-TNFα and rAAV-eGFP injected 3xTg-AD mice at 12 months of age. By this age, 3xTg-AD mice typically exhibit detectable amyloid and tau pathology in the cortex and hippocampus.15,15,26 Immunohistochemical analysis of regions proximal to rAAV-TNFα transduction revealed a significant reduction in detectable human APP, Aβ42, and hyperphosphorylated tau in the hippocampi of rAAV-TNFα injected 3xTg-AD mice as compared to the rAAV-eGFP control vector-infused cohort (Figure 9). Moreover, the use of the 6E10 antibody, which recognizes epitopes on human Aβ and APP, further confirmed that rAAV-TNFα injected 3xTg-AD mice harbored lower levels of Aβ/APP in regions proximal to the injection site at 12 months of age (Figure 9, E and F). Additionally, we detected minimal later-stage hyperphosphorylation events in rAAV-TNFα injected 3xTg-AD mice (Figure 9, G and H). This observed loss of AD-related pathology can be attributed to the substantial loss of transgene-expressing neurons in regions of chronic TNF-α expression.

Figure 9.

Ten months after intrahippocampal administration of rAAV-TNFα, plaque load and tau pathology are appreciably reduced in 3xTg-AD mice. 3xTg-AD mice injected with rAAV-TNFα (A, C, E, G) or rAAV-eGFP (B, D, F, H) were sacrificed at 10 months post injection and brains were sectioned at 30 μm and analyzed for the presence of human APP transgene product (A and B), extracellular human Aβ1–42 (C and D), hAPP/Aβ (E and F), and a hyperphosphorylated epitope of hTau (G and H) via immunohistochemistry with DAB development. The inset in each panel represents a sixfold magnification of the region outlined by the dotted box for more optimal visualization of stained pathological hallmarks. Scale bar in (G) = 100 μm.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates chronic, neuronally expressed TNF-α exposure in the 3xTg-AD mouse brain leads to enhanced microglial activation, up-regulation of known TNF-α downstream target molecules, and significant peripheral cell infiltration. Perhaps more importantly, our findings support an integral role of TNF-α as a major contributor to neuronal death in the AD brain. TNF-α is a central pro-inflammatory cytokine, produced in response to various intrinsic and extrinsic stimuli.27 Generally, TNF-α is produced as an innate mediator in multiple tissues, including the central nervous system, promoting chemokine and cytokine expression and extravasation of immune cells. The functions that cytokines perform in AD pathogenesis are controversial as some studies show that inflammatory processes seem beneficial, while others reveal exacerbation of pathology. In fact, the overexpression of an inflammatory mediator may impart differential effects depending on the molecule expressed and the source of that molecule. For example, long-term expression of MCP-1 from astrocytes in brains of an AD mouse model reveal exacerbated amyloid pathology.28 However, a recent study overexpressing interleukin-1beta from astrocytes ameliorated amyloid pathology without overt neuronal death.29

Our results further support a role of TNF-α in contributing to neuronal death in AD. While we do not yet know the precise signaling mechanisms at play, the observed enhancement of TNFRII and Jun transcripts specifically in 3xTg-AD mice suggest pro-apoptotic signaling mediated by TNF-α in these mice. It has been shown that the transmembrane form of TNF-α can signal through TNFRII, recruiting TRAF2, TRAF1, and cIAP 1 and 2, and activating the JNK/cJun pathway, which stimulates pro-apoptotic gene expression.30 A number of in vitro studies have shown that TNF-α can contribute to neuronal death in the context of AD-related pathogenic mediators. For example, TNF-α application alone or in conjunction with exogenously applied Aβ peptides has been shown to be neurotoxic.31,32 Of note, rAAV-TNFα injected 3xTg-AD mice at 4 months postinjection exhibited intracellular Aβ42 accumulation and phospho-Tau epitope detection as compared to control mice (Figures 3 and 4), suggesting that these processes may represent early events along a path toward eventual neuronal demise. Non-Tg mice injected with TNF-α did not exhibit significant evidence of neuronal death, underscoring the toxic combined effects of TNF-α along with 3xTg-AD transgene products. The contribution of the transgene products expressed in 3xTg-AD mice and resultant pathologies may sensitize the neurons to TNF-α release among other effects, altering their ability to survive. Evidence for increased vulnerability of 3xTg-AD neurons may be due in part to [Ca2+]i dysregulation as promoted by the PS1 knock-in mutation engineered into these mice.33

The extensive microglial activation observed in regions proximal to neuritic plaques and neuron loss in the setting of AD strongly implicates these cells as playing a key role in disease pathophysiology. Chronic expression of TNF-α in the hippocampus of 3xTg-AD mice via rAAV-TNFα transduction led to a significant enhancement in numbers of F4/80-immunopositive microglia and CD45-expressing leukocytes, and these cells may have participated in the observed demise of neurons. Moreover, the microglial marker CD11b was specifically enhanced within rAAV-TNFα transduced mice. These observations were limited to regions transduced via stereotactic rAAV vector delivery, as analysis of other brain structures distal to the transduction field revealed evidence of typical AD-related pathological development in manipulated 3xTg-AD mice (data not shown). TNF-α has been previously demonstrated to activate microglia to release stored glutamate, which is excitotoxic to neurons at supraphysiologic concentrations.34 Additionally, it was shown that Aβ-mediated stimulation of microglia leads to secretion of TNF-α and subsequent iNOS-dependent apoptosis in neurons.35 The identification of such a striking increase in complement protein C3 by TNF-α mirrors the complement activation observed in the human AD brain, which is purported to exacerbate pathology.36 Moreover, while complement may have a protective role in assistance in Aβ clearance, high levels could contribute to extensive activation of microglia and autolytic neuritic attack at later stages of disease.37 Therefore, one possibility for why Aβ and tau pathologies are reduced in rAAV-TNFα injected 3xTg-AD mice could be that TNF-α was integral in clearing Aβ but that the extent of coincident microglial activation also contributed to neuronal death. Since the evolution of Aβ pathology precedes disease-related events associated with tau in this model and accumulation of Aβ is purported to contribute to hyperphosphorylation of tau,38 it is possible that the clearance of Aβ prevented the onset of tau pathology in rAAV-TNFα treated 3xTg-AD mice. Alternatively, it is likely that the extent of the TNF-α-elicited neurotoxic response contributed to neuronal loss before the appearance of later stage Aβ or tau pathology. Understanding the temporal relationships among these processes and their potential interdependence are the foci of future experimentation.

Given the abundance of neuronal loss in TNF-α treated mice, it was somewhat surprising that we did not observe transcriptional down-regulation of synaptic molecules dynamin-1, PSD95, and synaptophysin. However, recent studies demonstrating that TNF-α is involved in synaptic scaling39 may indicate that a potential compensatory mechanism is at play, whereby proximal unaffected neurons increase synaptic connections to compensate for neurons undergoing cellular demise. Additional experimentation would be required to address the potential contribution of TNF-α mediated synaptic scaling to the quantitative transcript data sets associated with this study.

Although transgenic models incompletely recapitulate many AD-related pathological hallmarks, neuronal death is not common in many of the currently used AD models (reviewed in40). However, neuronal loss is the ultimate fate in late-stage AD patients with cognitive decline. Data from our model suggest that a chronic inflammatory event mediated by TNF-α contributes to AD-related neuronal death and provide the rationale for developing TNF-α-specific agents to subvert the disease process. Support for such an endeavor is preliminarily provided by a recently conducted open-label pilot study, where mild to severe AD patients were perispinally administered etanercept, a human TNFRII antagonist.41 After 6 months of treatment, a subset of patients exhibited cognitive improvement, suggesting that interfering with TNF-α mediated signaling can improve disease symptomatology.

Our ongoing work seeks to dissect these pathways to further understand the signaling mechanisms underlying chronic TNF-α neurotoxicity in vivo. The combination of viral vector-based gene transfer and a complex AD mouse model provides flexibility for examining TNF-α function throughout the lifetime of the animal and also within a selected brain region in which TNF-α function is modified. Altering the age at which TNF-α activity is experimentally manipulated may elucidate differential roles of this cytokine during various stages of the disease process, whereas changing the region of TNF-α activity modulation may provide insights into the regional specificity of AD pathology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Robert Kotin (NHLBI) for kindly providing the rAAV vector packaging platform, Dr. Terry Wright (University of Rochester) for providing the mTNF-α cDNA, Maya Desai (University of Rochester) for confocal microscope assistance and advice, Dr. James Powers (University of Rochester) for neuropathology consulation, and Landa Prifti (University of Rochester) for animal care and husbandry.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to William J. Bowers, Ph.D., Department of Neurology, Center for Neural Development and Disease, University of Rochester Medical Center, 601 Elmwood Ave., Box 645, Rochester, NY 14642. E-mail: william_bowers@urmc.rochester.edu.

Supported by grants NIH F31NS049995 to M.C.J., NIH R01-AG020204 to H.J.F., and NIH R01-AG023593 and R01-AG026328 to W.J.B.

Current address of H.J.F.: Office of the Executive Vice President for Health Sciences, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC.

References

- Billings LM, Oddo S, Green KN, McGaugh JL, LaFerla FM. Intraneuronal Abeta causes the onset of early Alzheimer’s disease-related cognitive deficits in transgenic mice. Neuron. 2005;45:675–688. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WS. Inflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:470S–474S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.470S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit WJ. Microglia and Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J Neurosci Res. 2004;77:1–8. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy PE, Rapport M, Graf L. Glial fibrillary acidic protein and Alzheimer-type senile dementia. Neurology. 1980;30:778–782. doi: 10.1212/wnl.30.7.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga S, Akai K, Ishii T. Demonstration of microglial cells in and around senile (neuritic) plaques in the Alzheimer brain. An immunohistochemical study using a novel monoclonal antibody. Acta Neuropathol. 1989;77:569–575. doi: 10.1007/BF00687883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itagaki S, McGeer PL, Akiyama H, Zhu S, Selkoe D. Relationship of microglia and astrocytes to amyloid deposits of Alzheimer disease. J Neuroimmunol. 1989;24:173–182. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(89)90115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandybur TI. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and astrocytic gliosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1989;78:329–331. doi: 10.1007/BF00687764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst A, Ulrich J, Heitz PU. Senile dementia of Alzheimer type: astroglial reaction to extracellular neurofibrillary tangles in the hippocampus. An immunocytochemical and electron-microscopic study. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1982;57:75–79. doi: 10.1007/BF00688880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer PL, McGeer EG. Local neuroinflammation and the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurovirol. 2002;8:529–538. doi: 10.1080/13550280290100969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohmeyer R, Rogers J. Molecular and cellular mediators of Alzheimer’s disease inflammation. J Alzheimers Dis. 2001;3:131–157. doi: 10.3233/jad-2001-3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtori S, Takahashi K, Moriya H, Myers RR. TNF-alpha and TNF-alpha receptor type 1 up-regulation in glia and neurons after peripheral nerve injury: studies in murine DRG and spinal cord. Spine. 2004;29:1082–1088. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200405150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Clark RK, McDonnell PC, Young PR, White RF, Barone FC, Feuerstein GZ. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression in ischemic neurons. Stroke. 1994;25:1481–1488. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.7.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafers M, Geis C, Svensson CI, Luo ZD, Sommer C. Selective increase of tumour necrosis factor-alpha in injured and spared myelinated primary afferents after chronic constrictive injury of rat sciatic nerve. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:791–804. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janelsins MC, Mastrangelo MA, Oddo S, LaFerla FM, Federoff HJ, Bowers WJ. Early correlation of microglial activation with enhanced tumor necrosis factor-alpha and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression specifically within the entorhinal cortex of triple transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2005;2:23. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-2-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, Murphy MP, Golde TE, Kayed R, Metherate R, Mattson MP, Akbari Y, LaFerla FM. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39:409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urabe M, Ding C, Kotin RM. Insect cells as a factory to produce adeno-associated virus type 2 vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:1935–1943. doi: 10.1089/10430340260355347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrea MR, Reiser PA, Polkovitch DA, Gumula NA, Branchide B, Hertzog BM, Schmidheiser D, Belkowski S, Gastard MC, Andrade-Gordon P. The use of formic acid to embellish amyloid plaque detection in Alzheimer’s disease tissues misguides key observations. Neurosci Lett. 2003;342:114–118. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasek W, Feleszko W, Golab J, Stoklosa T, Marczak M, Dabrowska A, Malejczyk M, Jakobisiak M. Antitumor effects of the combination immunotherapy with interleukin-12 and tumor necrosis factor alpha in mice. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1997;45:100–108. doi: 10.1007/s002620050408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger C, Gorbatyuk OS, Velardo MJ, Peden CS, Williams P, Zolotukhin S, Reier PJ, Mandel RJ, Muzyczka N. Recombinant AAV viral vectors pseudotyped with viral capsids from serotypes 1, 2, and 5 display differential efficiency and cell tropism after delivery to different regions of the central nervous system. Mol Ther. 2004;10:302–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCown TJ. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors in the CNS. Curr Gene Ther. 2005;5:333–338. doi: 10.2174/1566523054064995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondhi D, Peterson DA, Giannaris EL, Sanders CT, Mendez BS, De B, Rostkowski AB, Blanchard B, Bjugstad K, Sladek JR, Jr, Redmond DE, Jr, Leopold PL, Kaminsky SM, Hackett NR, Crystal RG. AAV2-mediated CLN2 gene transfer to rodent and non-human primate brain results in long-term TPP-I expression compatible with therapy for LINCL. Gene Ther. 2005;12:1618–1632. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao YF, Wang BJ, Cheng HT, Kuo LH, Wolfe MS. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1beta, and interferon-gamma stimulate gamma-secretase-mediated cleavage of amyloid precursor protein through a JNK-dependent MAPK pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49523–49532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFerla FM, Green KN, Oddo S. Intracellular amyloid-beta in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:499–509. doi: 10.1038/nrn2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll G, Jander S. The role of microglia and macrophages in the pathophysiology of the CNS. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;58:233–247. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunderland CA, McMaster WR, Williams AF. Purification with monoclonal antibody of a predominant leukocyte-common antigen and glycoprotein from rat thymocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1979;9:155–159. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830090212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S, Caccamo A, Kitazawa M, Tseng BP, LaFerla FM. Amyloid deposition precedes tangle formation in a triple transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanisch UK. Microglia as a source and target of cytokines. Glia. 2002;40:140–155. doi: 10.1002/glia.10161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Horiba M, Buescher JL, Huang D, Gendelman HE, Ransohoff RM, Ikezu T. Overexpression of monocyte chemotactic protein-1/CCL2 in beta-amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice show accelerated diffuse beta-amyloid deposition. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1475–1485. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62364-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaftel SS, Kyrkanides S, Olschowka JA, Miller JN, Johnson RE, O'Banion MK. Sustained hippocampal IL-1 beta overexpression mediates chronic neuroinflammation and ameliorates Alzheimer plaque pathology. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1595–1604. doi: 10.1172/JCI31450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varfolomeev EE, Ashkenazi A. Tumor necrosis factor: an apoptosis JuNKie? Cell. 2004;116:491–497. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg PB. Clinical aspects of inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2005;17:503–514. doi: 10.1080/02646830500382037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Yang L, Lindholm K, Konishi Y, Yue X, Hampel H, Zhang D, Shen Y. Tumor necrosis factor death receptor signaling cascade is required for amyloid-beta protein-induced neuron death. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1760–1771. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4580-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutzmann GE, Smith I, Caccamo A, Oddo S, Laferla FM, Parker I. Enhanced ryanodine receptor recruitment contributes to Ca2+ disruptions in young, adult, and aged Alzheimer’s disease mice. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5180–5189. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0739-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi H, Jin S, Wang J, Zhang G, Kawanokuchi J, Kuno R, Sonobe Y, Mizuno T, Suzumura A. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces neurotoxicity via glutamate release from hemichannels of activated microglia in an autocrine manner. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21362–21368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600504200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs CK, Karlo JC, Kao SC, Landreth GE. Beta-amyloid stimulation of microglia and monocytes results in TNFalpha-dependent expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and neuronal apoptosis. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1179–1188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01179.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradt BM, Kolb WP, Cooper NR. Complement-dependent proinflammatory properties of the Alzheimer’s disease beta-peptide. J Exp Med. 1998;188:431–438. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.3.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer EG, Klegeris A, McGeer PL. Inflammation, the complement system and the diseases of aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26 Suppl 1:94–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S, Billings L, Kesslak JP, Cribbs DH, LaFerla FM. Abeta immunotherapy leads to clearance of early, but not late. Hyperphosphorylated tau aggregates via the proteasome. Neuron. 2004;43:321–332. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellwagen D, Malenka RC. Synaptic scaling mediated by glial TNF-alpha. Nature. 2006;440:1054–1059. doi: 10.1038/nature04671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins GA, Jacobsen H. Transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease: phenotype and application. Behav Pharmacol. 2003;14:419–438. doi: 10.1097/01.fbp.0000088420.18414.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobinick E, Gross H, Weinberger A, Cohen H. TNF-alpha modulation for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a 6-month pilot study. Med Gen Med. 2006;8:25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]