Abstract

No adequate means exist to identify the minority of ulcerative colitis (UC) patients destined to undergo neoplastic progression. Recognition of this subset would advance UC cancer surveillance by focusing the available management options onto the highest risk patients. Three different assays of genomic alterations in nondysplastic UC biopsies show promise for distinguishing patients with neoplasia (UC progressors) from those without (UC nonprogressors), including assays of telomere length, anaphase bridges, and chromosomal fluorescence in situ hybridization. Expanding the number of patients and testing of assays simultaneously in the same biopsy further validated their utility. A panel approach also improved testing outcome. A total of 14 UC progressors was readily separable from 15 UC nonprogressors and 6 normal controls. Chromosomal entropy (ie, the extent of alteration diversity) proved to be the most useful test. By receiver-operating characteristic analysis, mean chromosomal entropy in 28 patients over all four chromosomes yielded 100% sensitivity and 92% specificity for distinguishing progressors from nonprogressors with optimum choice of threshold. Moreover, separation was achieved using only nondysplastic and predominantly rectal (82.8%) biopsies that were remote from neoplasia, suggesting that full colonoscopy with extensive biopsies might be avoided for the majority of UC patients, the nonprogressors. These data further strengthen the concept that genomic biomarkers can distinguish UC progressors from nonprogressors and improve cancer surveillance in UC.

Extensive ulcerative colitis (UC) of greater than 8 years duration confers an increased risk of colorectal cancer.1,2 Clinical management options include lifelong intensive endoscopic biopsy surveillance versus prophylactic colectomy, which are difficult, inaccurate, discomforting to patients, and expensive.3 This study was conducted to better understand the earliest steps of UC tumorigenesis in the hope that this knowledge could identify the subset of patients at highest risk for progression to cancer and save the great majority with limited risk from unnecessary procedures.

UC cancers arise from pre-invasive dysplasia,4,5 developing within even larger genetically abnormal fields that often exhibit aneuploidy,5,6 p53 alterations,6,7 microsatellite instability,8 chromosomal aberrations assessed by metaphase comparative genomic hybridization,9 and DNA fingerprinting alterations.10,11,12 Using these techniques we found that genomic alterations are an early step in UC neoplastic progression that can even be detected in nondysplastic, diploid biopsies that are far distant from neoplasia. As such, these genomic changes predate morphological neoplasia and show promise as biomarkers of neoplastic risk.

A limitation of the above genomic assays (DNA ploidy, p53 alterations, microsatellite instability, comparative genomic hybridization, DNA fingerprinting) is that their detection requires clonal expansion of the abnormal cell population to encompass the majority of the tested cells. Further, none have been found to involve sufficiently broad fields within the colon to serve as ideal screening assays. An ideal mucosal screening assay for cancer risk would not only predate incurable cancer and be objective and reproducible, but it should be present throughout the entire colon. This latter feature would obviate sampling error, arguably the single most important problem in present day UC colorectal cancer surveillance.

The current gold standard biomarker for cancer risk in UC is histological dysplasia. Unfortunately, using standard colonoscopy, an estimated minimum of 33 jumbo biopsies is required to detect dysplasia with even 90% confidence.5 Chromoendoscopy and other endoscopic methodologies show promise that newer techniques might reduce sampling error, but this remains an area of active investigation.13,14 A pancolonic biomarker might circumvent sampling error altogether. Further, a pancolonic abnormality would also necessarily involve the most distal rectal mucosa and would therefore be accessible by far less invasive means than full colonoscopy.

Theorizing that nonclonal genomic alterations would likely be even earlier genetic events that might involve even broader colonic fields than the aforementioned clonal defects, we sought to analyze nonclonal alterations. We initially selected dual-color fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), with paired chromosome-specific centromeric and locus-specific arm probes on four different chromosomes. These FISH probes were selected based on consistent chromosomal abnormalities using conventional metaphase comparative genomic hybridization on nondysplastic, diploid mucosa from multiple UC progressors.15 FISH was selected because of its ability to identify chromosomal alterations in nonclonally expanded single interphase cells or small subpopulations representing <10% of the cells.16 FISH would thus allow for the detection of infrequent and possibly random changes predating clonal expansion.

Our prior studies have assessed only the percentage of cells exhibiting a specific FISH abnormality (arm gain or loss, centromere gain or loss). We now also assess the use of entropy as the measure of chromosomal aberrations, rather than just the percentage of cells with specified alterations. Entropy is a measure of how diverse the FISH aberrations are among the various possible categories of deviation, relative to the expected normal count of two FISH signals per probe per cell. For example, a sample with 70% of cells having a normal FISH signal of 2 for a given probe per cell and the remaining 30% of cells with FISH varying percentages of signals of 0, 1, 3, and 4 has greater entropy than a sample having 70% of cells with normal signals and all of the remaining 30% of cells having one specific aberration, for example three FISH signals for a certain marker per cell. Thus, entropy assesses the diversity of the low-level preclonal chromosomal alterations.

Telomere shortening and anaphase bridge assays of genomic alteration have also been explored in UC neoplastic progression.17 Similarly to FISH, these assays evaluate individual cells and are therefore also able to detect preclonal and earlier alterations that theoretically might approximate an ideal, pancolonic distribution. Telomeres shorten with oxidative stress and with cell proliferation, both of which are elevated in UC relative to normal colon.18,19 Telomere shortening promotes chromosomal end-to-end fusions that result in chromosomal breakage during cell division at anaphase with subsequent arm gains and losses in the daughter cells. Such bridge-breakage-fusion cycles are documented by the formation of anaphase bridges, in which two anaphase daughter nuclei remain abnormally connected by strand(s) of fused chromosome(s) during mitosis.20,21,22

Our initial reports on these three preclonal assays in UC neoplasia demonstrate that genomic alterations are present throughout the colon of UC progressors, and are distinguishable from normal control patients.15,17 Using a small number of nonprogressor patients, we have also shown that the same appears to be true.17 These investigations are now expanded to assess whether this biomarker panel singly or in combination and measured simultaneously from the same biopsy can differentiate well-characterized patients who have undergone high-density colonoscopic biopsy surveillance throughout many years.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Biopsies

The University of Washington Human Subjects Review Board annually reviewed and approved this research. Patients were selected consecutively from our banked frozen mucosal archives based on being within one of three diagnostic categories: 1) normal controls without UC; ii) UC nonprogressors without evidence of dysplasia; and iii) UC progressors with concurrent dysplasia or carcinoma, and having nondysplastic mucosal biopsies for testing. Nondysplastic biopsies of nonprogressors were obtained from these patients’ most recent colonoscopies. From progressors, nondysplastic biopsies were taken from same colectomies as the most advanced neoplastic pathology (dysplasia or cancer). Nondysplastic biopsies from all study patients were preferentially selected from the rectum if available because the rectum represents the most clinically accessible large bowel location with the highest potential clinical utility.

The UC patients were followed by an intensive biopsy surveillance protocol. Four quadrant biopsies were taken every 10 cm throughout the colon and every 5 cm throughout the rectosigmoid region. Biopsies were freshly oriented and mounted at the time of endoscopy, followed by Hollande’s fixation and routine processing through step and serial sectioning, as previously described.5,6,7 Immediately adjacent fresh samples were frozen at −70°C in minimal essential medium with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide until use. All biopsies were histologically examined by gastrointestinal pathologists (M.P.B., C.E.R., and the late Dr. Rodger C. Haggitt). Inflammatory activity scores of 1 to 4 were assessed on every biopsy as follows: intraepithelial neutrophils = 1, rare crypt abscesses = 2, numerous crypt abscesses = 3, and erosion/ulceration = 4. The Inflammatory Bowel Disease Dysplasia Morphology Study Group consensus criteria were used to grade dysplasia, except that the indefinite for dysplasia category was not further subdivided.4 Flow cytometric DNA ploidy analysis was performed by a specialist in this technique (P.S.R.) in a subset of ∼20 biopsies per surveillance colonoscopy, as previously described.5 Aneuploidy was defined as a distinct nondiploid peak in excess of 5% of cells.23

Colonocyte Preparation

Epithelial cells were isolated from thawed mucosal biopsies by a shake-off technique in Hanks’ buffer with 20 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 5 mmol/L CaCl2, 5 mmol/L MgCl2, and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide at 4°C, as previously described.15,17 Cytokeratin expression by flow cytometry revealed the isolated cells in suspension using this shake-off technique to be greater than 90% pure epithelial cells.15

FISH

As previously described,15 cells were washed in 5 mmol/L CaCl2 with 0.1% Nonidet P-40, spun (10 minutes, 1000 × g), washed again in 1 ml of 5 mmol/L CaCl2 with 200 μl of chilled 3:1 methanol:acetic acid, and spun. Ten-μl nuclear suspensions were dropped on plain glass slides, fixed with 3:1 methanol:acetic acid, followed by 1% paraformaldehyde. Replicate slides from each biopsy were hybridized to pairs of fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled centromere and tetramethyl-rhodamine isothiocyanate-labeled locus-specific probes for chromosomes 8, 11, 17, and 18, as follows: D8Z2 (centromere), 8q21.3; D18Z1, 18q21.2 (Oncor, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD); p53 (17p13.1), 17 α (centromere); and cyclin D1 (11q13) and 11 SG (centromere) (Vysis, Inc., Downers Grove, IL). Analyses from tetramethyl-rhodamine isothiocyanate-labeled locus-specific probes on chromosomal arms are for simplicity referred to as analyses of chromosomal arms. Slides were dehydrated in graded 70 to 100% ethanols at 22°C, denatured in 70% formamide at 72°C, dehydrated in graded 70 to 100% ethanols at −20°C, and incubated overnight with the probe pairs described above. Slides were then washed in 2× standard saline citrate at 72°C and 2× standard saline citrate with 0.03% Tween, pH 5.3. Cells were covered with Anti-Fade (Oncor, Inc.) containing 0.25 ng/μl 4,6-diamindino-2-phenylindole (Sigma, St Louis, MO), and examined at ×100 under oil using an epifluorescence microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu C5810 charge-coupled device camera (Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan). For each sample and pair of probes, the number of red and green FISH spots was counted for 100 ± 6 nuclei (mean ± SD) by an observer blinded to sample identity. Counting was blindly repeated on a subset of samples to evaluate reproducibility, and was determined to be within expected statistical error. A semiquantitative quality scoring system on a scale of 1 to 5 was used to assess confidence in the FISH counts for each slide preparation, based on the yield, nuclear morphology, signal intensity, and autofluorescent background, with 1 being the poorest and 5 the best quality. The mean confidence score for the reported FISH data are 4 ± 1 (mean ± SD).

Telomere Length by Peptide Nucleic Acid FISH

As previously described,17,24 thawed biopsies were lightly fixed in 0.5% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes, followed by 70% ethanol fixation overnight at 4°C. After routine paraffin embedding and 5-μm-thick sectioning of the biopsy tissues, slides were incubated in 10 mmol/L sodium citrate for 10 minutes at 78°C, rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), dehydrated through an ethanol series (25%, 50%, 95%), and air-dried. This was followed by digestion with 1% pepsin in 0.01 mol/L HCl heated to 37°C for 2 minutes at 37°C, PBS rinsing, ethanol dehydration, and drying. The slides were then treated with 10 mg/ml of RNase for 10 minutes at 37°C, PBS-rinsed, ethanol-dehydrated, and drying. The tissue sections were hybridized with 100 μmol/L PNA telomere probe (5′-CCCTAACCCTAACCCTAA-3′) (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA), conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate, for 10 minutes at 78°C and incubated overnight at room temperature. The slides were then washed in a 70% formamide buffer four times for 15 minutes, followed by a PBS/0.05% Tween 20 wash four times for 5 minutes, ethanol dehydration, and drying. The nuclei were counterstained with the DNA dye TOTO-3 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 5 minutes, followed by a 1-minute wash with PBS and brief serial ethanol dehydration. Coverslips were mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and digitized images of the slides were obtained with an Axiovert 100TV confocal microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). For all colonic biopsies, the fluorescein isothiocyanate settings were maintained constant. For a subset of biopsies, 500 μg/ml of an α centromere repeat phosphoramidate probe (5′-ATTCGTTGGAAACGGGA-3′) (TAMRA label, a gift from Geron Corp., Menlo Park, CA) was hybridized simultaneously with the PNA telomere hybridization described above. Telomere FISH image analyses were performed using Optimas image analysis software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD). The DNA image plane was segmented using a watershed algorithm and the nuclei were manually identified as belonging to either epithelial or stromal cell groups. Within each nucleus in each group, a macro was used to analyze the green telomere and red centromere pixel intensity distributions.

Anaphase Bridge Measurement

Epithelial cells were isolated from biopsies by shake-off in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, as previously described.17 Epithelial cells from non-UC controls (n = 6), UC nonprogressors (n = 14), and UC progressors (n = 14) were 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole-stained and cells with G2/4N DNA content were sorted by flow cytometry onto glass slides. An average of 1753 sorted cells was manually examined by fluorescence microscopy for bridging strands of DNA between daughter nuclei (anaphase bridges). The frequency of anaphase bridges among the total sorted cells was determined. Because the proportion of cells sorted as G2/4N varied between observations and was contaminated with aggregated cells, the frequency of anaphase bridges was expressed within the three patient groups as the percentage of total cells in the biopsy using binomial regression with the percent sorted cells as a covariate.

Statistics

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to investigate the sensitivity and specificity of various genomic abnormalities for distinguishing histologically negative UC-progressors’ biopsies from UC nonprogressors’ biopsies and normal control patients’ biopsies.25,26,27 ROC analysis demonstrates the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity as the threshold for defining a positive test to identify progressors from nonprogressors is varied, such as the thresholds for the percentage of cells with FISH abnormalities, the telomere lengths, or the percentage of cells with anaphase bridges. Sensitivity in this context refers to the probability of a positive test result in an individual UC progressor biopsy. Specificity refers to the probability that the test is negative in a UC nonprogressor biopsy. ROC curves were analyzed for each assay separately and in various combinations. The optimal threshold cutoff was determined as that corresponding to the ROC point closest to the upper left corner of the plot. Cutoffs differ depending on the abnormality. Entropy was calculated as a measure of variation or diversity defined by the probability distribution of observed events. With P as the probability of an event a, the entropy H(A) for all events a in A is: H(A) = −SUMa P(a) log2 P(a), ie, the sum of the log2 probabilities of the model p, weighted by the real probabilities p.

For the analysis of anaphase bridges, logistic regression was used to estimate the probability of being a progressor for a given mean bridge frequency adjusting for percentage of G2 cells. The predicted probabilities were used to differentiate progressors and nonprogressors in the ROC analysis. In the combined analysis of telomere and anaphase bridges, logistics regression was similarly used to estimate the probability of being a progressor for a given telomere length, anaphase bridge frequency, and percentage of G2 cells, and the predicted probabilities from such logistic model were used for the ROC analysis.

Results

Patients

The average subject age at the time of genomic biomarker testing for the six normal control patients (four males, two females) was 44.1 ± 7.9 years (mean ± SD; range, 32 to 54 years), whereas that of the 14 UC progressor patients (eight males, six females) was 47.2 ± 13.2 years (mean ± SD; range, 30 to 71 years), and the 15 UC nonprogressor patients (seven males, eight females) was 45.6 ± 13.3 years (mean ± SD; range, 25 to 72 years) (P = NS). The duration of disease in the UC nonprogressor patients was 18.2 ± 7.7 years (mean ± SD; range, 8 to 37 years) and in the UC progressor patients was 17.3 ± 12.8 years (mean ± SD; range, 1.5 to 50 years) (P = NS). A total of 2 of 14 progressors had primary sclerosing cholangitis, whereas none of the 6 normal controls or 15 nonprogressors did. The severity of inflammatory activity was similar in all of the UC patients, assessed over multiple colonoscopic surveillance and colectomy specimens involving more than 3000 histological samples. Inflammatory activity was present in the actual biomarker-tested biopsies of four progressors and four nonprogressors (P = NS), as provided for each patient in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient and Tested Biopsy Characteristics

| Patient | Age (years) | Gender | Disease duration | PSC | Most advanced pathology | Dysplasia grade on tested biopsy | Activity score on tested biopsy | Distance to neoplasia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal-1 | 32 | M | N | Rectal prolapse | Negative (rectum) | 0 | ||

| Normal-2 | 54 | M | N | Diverticulosis | Negative (sigmoid) | 0 | ||

| Normal-3 | 38 | M | N | Endometriosis | Negative (rectum) | 0 | ||

| Normal-4 | 49 | F | N | Diverticulosis | Negative (sigmoid) | 0 | ||

| Normal-5 | 46 | M | N | Diverticulosis | Negative (sigmoid) | 0 | ||

| Normal-6 | 46 | F | N | Meningomyelocele | Negative (rectum) | 0 | ||

| Nonprogressor-1 | 53 | F | 17 years | N | Negative | Negative (rectum) | 1 | |

| Nonprogressor-2 | 49 | M | >30 years | N | Negative | Negative (rectum) | 0 | |

| Nonprogressor-3 | 25 | M | 8 years | N | Negative | Negative (rectum) | 0 | |

| Nonprogressor-4 | 29 | M | 10 years | N | Negative | Negative (rectum) | 1 | |

| Nonprogressor-5 | 59 | F | 22 years | N | Negative | Negative (rectum) | 0 | |

| Nonprogressor-6 | 44 | F | 21 years | N | Negative | Negative (rectum) | 0 | |

| Nonprogressor-7 | 72 | F | 18 years | N | Negative | Negative (rectum) | 0 | |

| Nonprogressor-8 | 37 | M | 16 years | N | Negative | Negative (right colon) | 0 | |

| Nonprogressor-9 | 54 | M | 37 years | N | Negative | Negative (rectum) | 0 | |

| Nonprogressor-10 | 54 | M | 15 years | N | Negative | Negative (rectum) | 0 | |

| Nonprogressor-11 | 65 | F | 24 years | N | Negative | Negative (rectum) | 2 | |

| Nonprogressor-12 | 40 | F | 15 years | N | Negative | Negative (rectum) | 0 | |

| Nonprogressor-13 | 32 | F | 15 years | N | Negative | Negative (rectum) | 0 | |

| Nonprogressor-14 | 32 | M | 13 years | N | Negative | Negative (rectum) | 3 | |

| Nonprogressor-15 | 39 | F | 12 years | N | Negative | Negative (rectum) | 0 | |

| Progressor-1 | 45 | F | 9 years | N | HGD | Negative (rectum) | 0 | 43 cm |

| Progressor-2 | 42 | F | 35 years | N | HGD | Negative (rectum) | 0 | 70 cm |

| Progressor-3 | 41 | F | 16 years | N | HGD | Negative (rectum) | 0 | 49 cm |

| Progressor-4 | 31 | M | 4 years | N | CA | Negative (transverse) | 1 | 25 cm |

| Progressor-5 | 34 | M | 20 years | Y | HGD | Negative (rectum) | 0 | 32 cm |

| Progressor-6 | 71 | F | 50 years | N | CA | Negative (rectum) | 2 | 4 cm |

| Progressor-7 | 51 | M | 20 years | N | HGD | Negative (rectum) | 0 | 36 cm |

| Progressor-8 | 65 | M | 5 years | N | HGD | Negative (right colon) | 0 | 3 cm |

| Progressor-9 | 53 | F | 22 years | N | CA | Negative (rectum) | 0 | 8 cm |

| Progressor-10 | 32 | M | 16 years | N | HGD | Negative (rectum) | 0 | 12 cm |

| Progressor-11 | 63 | M | 10 years | N | CA | Negative (transverse) | 2 | 35 cm |

| Progressor-12 | 30 | M | 16 years | Y | HGD | Negative (cecum) | 1 | 3 cm |

| Progressor-13 | 53 | M | 18 years | N | LGD | Negative (rectum) | 0 | 55 cm |

| Progressor-14 | 50 | F | 1.5 years | N | CA | Negative (rectum) | 0 | 15 cm |

Negative, negative for dysplasia; LGD, low-grade dysplasia; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; HGD, high-grade dysplasia; CA, adenocarcinoma; M, male; F, female; Y, yes; N, no. Activity score; 1, cryptitis; 2, rare crypt abscess; 3, numerous crypt abscesses; 4, erosion/ulcer.

Biopsies

An average of 50.1 ± 14.7 biopsies was obtained per colonoscopy (mean ± SD; range, 33 to 89 biopsies) by jumbo biopsy forceps as 4-quadrant samples for routine histology from each of the UC patients. Of the UC progressor patients, five had a highest neoplastic diagnosis of cancer, and eight had high-grade dysplasia and one had low-grade dysplasia. One to two fresh-frozen biopsies without dysplasia were analyzed from each UC patient, the majority of which came from the rectum (82.8%) and the remainder from the transverse or right colon (Table 1). The average distance from the tested biopsies that were negative for dysplasia to the most advanced neoplasia (ie, cancer or high-grade dysplasia or low-grade dysplasia) was 27.9 ± 21.4 cm (mean ± SD; range, 3 to 70 cm) (Table 1). Aneuploidy was present at an average distance of 14 cm (range, 3 to 28 cm) from the diploid sites without dysplasia that were analyzed for the genomic biomarkers in this study.

The UC nonprogressor patients were followed as described at intervals of every 1 to 3 years for an average number of colonoscopies in our surveillance program of 2.4 per patient (range, 1 to 5). Throughout this surveillance period, 12 of the 15 UC nonprogressors patients continued to have histology that was negative for dysplasia and diploid by flow cytometric DNA ploidy analysis, whereas 3 developed focal alterations indefinite for dysplasia in areas of obscuring active inflammation, but remained diploid by flow cytometry at last follow-up.

FISH Sensitivity and Specificity

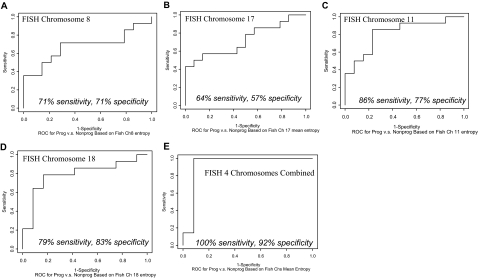

By FISH, abnormalities in chromosomal arms, especially losses, as compared to centromere changes, were more common and discriminatory between progressors and nonprogressors (data not shown). In addition to arm loss, FISH entropy was also assessed and was found to be the most discriminatory measure (Figure 1, A–E). The four individual chromosome ROC curves for entropy are shown in Figure 1, A–D, including the sensitivities and specificities with optimal choices of thresholds for each chromosome. As shown in Figure 1E, the mean total entropy over all four chromosomes, using one FISH arm probe per each of the four chromosomes, provides 100% sensitivity and 92% specificity with optimum choice of threshold. This represents the most discriminatory assay between UC progressors and nonprogressors in the study.

Figure 1.

Empirical ROC curves for individual chromosomal alterations to distinguish UC progressors from UC nonprogressors, as measured by FISH entropy. Individual chromosomes 8, 17, 11, and 18 are depicted (A–D, respectively). Mean total entropy combining all four chromosomes (E) improves the separation of progressor and nonprogressors relative to each individual chromosome alone. The sensitivities and specificities at optimal choices of thresholds are shown under each curve. The ROC curves do not show the actual assay values (here, entropy), but sensitivity increases as entropy increases.

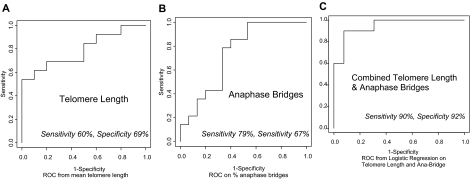

Telomere Length and Anaphase Bridge Sensitivity and Specificity

Using optimal choice of threshold on ROC analysis, the sensitivity and specificity for telomere length measurement by in situ PNA FISH were 60% and 69%, respectively (Figure 2A). For anaphase bridge quantitation, they were 79% and 67%, respectively (Figure 2B). When analyzed in combination, using logistic regression on the two measures, the ROC results with optimal choice of threshold improved to 90% and 92%, respectively (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Empirical ROC curves for distinguishing UC progressors and nonprogressors using telomere length by PNA FISH (A), percent anaphase bridge formation (B), and logistic regression on telomere length and percent anaphase bridges combined (C). The sensitivities and specificities at optimal choices of thresholds are shown under each curve.

Discussion

Current cancer prevention strategies in UC present great difficulties for patients and physicians alike. Management options are highly invasive and include prophylactic colectomy or lifelong intensive colonoscopic biopsy surveillance. An estimated minimum of 33 biopsies on colonoscopy are needed to detect dysplasia within the formidably large surface area comprising the colon.5 This is quite difficult for patients and suffers from inaccuracies at both the endoscopic and histological levels. Considering that ∼90% of UC patients will never develop neoplastic change, this situation is woefully inadequate. There is thus a great need for improved biomarkers to identify the subpopulation of UC patients who are going to develop dysplasia and/or cancer. This would focus surveillance efforts onto this ∼10% highest risk group and allow the remaining large majority to avoid unnecessary testing. FISH, telomere length, and anaphase bridge genomic biomarkers, as reported herein, show considerable promise toward this goal.

Our initial study demonstrated that FISH can differentiate single normal control colonic biopsies from nondysplastic biopsies of UC progressors with dysplasia or cancer elsewhere in their colons.15 The fact that this difference was detectable using single nondysplastic rectal biopsies that were far distant from these UC progressors’ neoplasms indicated widespread colonic alterations. The current study further examines the next logical question of whether genomic biomarkers on nondysplastic biopsies can also differentiate UC progressors with concurrent cancer/dysplasia from UC nonprogressors, who remain dysplasia-free during long-term surveillance. Our initial study reported this on a smaller number of patients and without simultaneous testing of all biomarkers on the same nondysplastic sample.17 We now confirm these results on more patients and show improved discrimination when the assays are used in combination. Specifically, FISH on all four chromosomes combined or telomere length combined with anaphase bridges, yields better discrimination of progressors and nonprogressors than each assay separately. The additional statistical rigor of ROC analysis and FISH entropy calculations are newly applied as well and also further document that UC progressors can be distinguished from nonprogressors. By ROC analysis, mean total entropy combining all four chromosomes yields a promising 100% sensitivity and 92% specificity with optimum choice of threshold for distinguishing the tested cohort of UC progressors from long-term UC nonprogressors.

The genomic alterations detected in this study were based on random tiny samples of one to two biopsies from UC progressors. These were obtained from the distal most (82.8% of tested samples were rectal) nondysplastic mucosa available from colectomies with simultaneous diagnoses of dysplasia/cancer elsewhere. In fact, the tested nondysplastic samples were located an average 28 cm from the patients’ simultaneous cancers or dysplasias. Thus, the abnormal genomic field appears to involve a large area, if not the entire colon, of the tested UC progressors. Such diffuse involvement is exciting, as it may fulfill, if true, an important requirement for the ideal biomarker on UC colonic mucosa. Diffuse distribution would eliminate the sampling error that today is arguably the greatest problem facing the gold standard of biopsy surveillance for histological dysplasia. As such, these genomic biomarkers could have profound implications for future surveillance strategy in UC by preventing unnecessary colonoscopy in nonprogressors while better identifying the highest risk potential progressor group.

The chromosomal alterations we have observed in nondysplastic biopsies from UC progressors involve diverse changes in multiple chromosomes, with loss of chromosomal arms as the most frequent early event,15,17 which is now further established. Most of the progressor nondysplastic biopsies show diverse and low-level (<10%) FISH abnormalities, suggesting that these changes are not yet clonal. This level of preclonal chromosomal alteration is not present in the chronic UC nonprogressors we have tested,17 which is further strengthened by the current study. We hypothesize that neoplastic progression in UC progressors begins with an accelerated mutation rate, according to the mutator phenotype formulated by Loeb.29 Chromosomal alterations are initially mostly a random process, with chromosomal arm losses occurring predominantly over a very large field of cells. Some of these changes result in loss of tumor suppressor loci with subsequent clonal expansion and neoplastic clonal evolution as described by Nowell.28 We hypothesize that a subset of UC patients have increased susceptibility to genomic alterations, through as yet unknown mechanisms, and that these patients represent the group at increased risk of cancer.

The genomic alterations in progressors are exciting for several additional reasons. The high rates of chromosomal alteration in histologically negative epithelium from UC progressors implicate more targeted mechanisms of genomic instability than previously understood. Oxidative injury,30,31,32,33 telomere shortening,22,34 and loss of mitotic fidelity35,36 are possible contributors. Telomere shortening may be contributing to chromosomal alteration via end-to-end chromosome fusion and consequent nondisjunction or bridge-breakage-fusion.20,22,37 Finally, these observations suggest that medical intervention to reduce chromosomal damage may prevent neoplastic progression in susceptible UC patients.

Based on the high sensitivity, high specificity, and widespread distribution, involving only one to two biopsies from the most accessible distal colonic mucosa, these biomarkers hold promise for improving UC cancer surveillance. The retrospective nature of these early studies demonstrate that the minority subset of UC patients (∼10%) most likely to benefit from intensive cancer surveillance and prevention strategies can be separately identified from the much larger UC nonprogressor majority (∼90%). Conceivably, if the assays perform as well in future testing, UC patients could be tested for these far less invasive genomic assays on minimal samplings limited to distal rectal mucosa and only thereafter referred for full colonoscopy and biopsy sampling for dysplasia if they harbor diagnostic genomic alterations. Those without genomic alterations on periodic testing might be able to avoid colonoscopy altogether. Further prospective confirmation, reproducibility testing, and longitudinal analyses over time will be essential future investigations to assess the robustness of these assays, the optimal numbers and sites of biopsy sampling, and the timing of testing onset and intervals.

Acknowledgments

This study is dedicated to the memory of our departed colleague and friend, Dr. Rodger C. Haggitt, without whose dedication, insight, and uncompromising standards of excellence, this study would not have been possible.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Mary P. Bronner, M.D., The Cleveland Clinic, Department of Anatomic Pathology, L-25, 9500 Euclid Ave., Cleveland, OH 44195. E-mail: bronnem@ccf.org.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants R01 CA068124 and R29 CA77607) and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

M.P.B. and J.N.O. contributed equally to this study.

References

- Prior P, Gyde SN, Macartney JC, Thompson H, Waterhouse JA, Allan RN. Cancer morbidity in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1982;23:490–497. doi: 10.1136/gut.23.6.490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, Adami HO. Ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1228–1233. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011013231802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RH, Jr, Feldman M, Fordtran JS. Colon cancer, dysplasia, and surveillance in patients with ulcerative colitis. A critical review. N Engl J Med. 1987;26:1654–1658. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706253162609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddell RH, Goldman H, Ransohoff DF, Appelman HD, Fenoglio CM, Haggitt RC, Ahren C, Correa P, Hamilton SR, Morson BC, Sommers SC, Yardly JH. Dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: standardized classification with provisional clinical applications. Hum Pathol. 1983;11:931–968. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(83)80175-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin CE, Haggitt RC, Burmer GC, Brentnall TA, Stevens AC, Levine DS, Dean PJ, Kimmey M, Perera DR, Rabinovitch PS. DNA aneuploidy in colonic biopsies predicts future development of dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1611–1620. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmer GC, Rabinovitch PS, Haggitt RC, Crispin DA, Brentnall TA, Kolli VR, Stevens AC, Rubin CE. Neoplastic progression in ulcerative colitis: histology, DNA content, and loss of a p53 allele. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1602–1610. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brentnall TA, Crispin DA, Rabinovitch PS, Haggitt RC, Rubin CE, Stevens AC, Burmer GC. Mutations in the p53 gene: an early marker of neoplastic progression in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1994;2:369–378. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brentnall TA, Crispin DA, Bronner MP, Cherian SP, Hueffed M, Rabinovitch PS, Rubin CE, Haggitt RC, Boland CR. Microsatellite instability is present in non-neoplastic mucosa from patients with chronic ulcerative colitis. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1237–1240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willenbucher RF, Zelman SJ, Ferrell LD, Moore DH, II, Waldman FM. Chromosomal alterations in ulcerative colitis-related neoplastic progression. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:791–801. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Rabinovitch PS, Crispin DA, Emond MJ, Koprowicz KM, Bronner MP, Brentnall TA. DNA fingerprinting abnormalities can distinguish ulcerative colitis patients with dysplasia and cancer from those who are dysplasia/cancer free. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:665–672. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63860-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Bronner MP, Crispin DA, Rabinovitch PS, Brentnall TA. Characterization of genomic instability in ulcerative colitis neoplasia leads to discovery of putative tumor suppressor regions. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2005;162:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Rabinovitch PS, Crispin DA, Emond MJ, Bronner MP, Brentnall TA. The initiation of colon cancer in a chronic inflammatory setting. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1513–1519. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Schofield G, Forbers A, Price AB, Talbot IC. Pancolonic indigo carmine dye spraying for the detection of dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2004;53:256–260. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.016386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiesslich R, Neurath MF. Chromoendoscopy: an evolving standard in surveillance for ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:695–696. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200409000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovitch PS, Dziadon S, Brentnall TA, Emond M, Crispin DA, Haggitt RC, Bronner MP. Pancolonic chromosomal instability precedes dysplasia and cancer in ulcerative colitis. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5148–5153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Genetic instability in colorectal cancers. Nature. 1997;6625:623–627. doi: 10.1038/386623a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan JN, Bronner MP, Brentnall TA, Finley JC, Shen WT, Emerson S, Emond MJ, Gollahon KA, Moskovitz AH, Crispin DA, Potter JD, Rabinovitch PS. Chromosomal instability in ulcerative colitis is related to telomere shortening. Nat Genet. 2002;32:280–284. doi: 10.1038/ng989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Zglinicki T. Role of oxidative stress in telomere length regulation and replicative senescence. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2000;908:99–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn EH. Structure and function of telomeres. Nature. 1991;350:569–573. doi: 10.1038/350569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hande MP, Samper E, Lansdorp P, Blasco MA. Telomere length dynamics and chromosomal instability in cells derived from telomerase null mice. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:589–601. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.4.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artandi SE, Chang S, Lee SL, Alson S, Gottlieb GJ, Chin L, DePinho RA. Telomere dysfunction promotes non-reciprocal translocations and epithelial cancers in mice. Nature. 2000;406:641–645. doi: 10.1038/35020592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey SM, Murnane JP. Telomeres, chromosome instability and cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2408–2417. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankey TV, Rabinovitch PS, Bagwell B, Bauer KD, Duque RE, Hedley DW, Mayall B, Wheeless L, Cox C. Guidelines for implementation of clinical DNA cytometry. Cytometry. 1993;14:472–477. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990140503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan JN, Finley JC, Risques RA, Shen WT, Gollahon KA, Moskovitz AH, Gryaznov S, Harley CB, Rabinovitch PS. Telomere length assessment in tissue sections by quantitative FISH: image analysis algorithms. Cytometry A. 2004;58:120–131. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotnitzky A, Jewell NP. Hypothesis testing of regression parameters in semiparametric generalized linear models for cluster correlated data. Biometrika. 1990;77:485–497. [Google Scholar]

- McCullagh P, Nelder JA. New York: Chapman and Hall,; Generalized Linear Models. (ed 2) 1989:p 124ff. [Google Scholar]

- Pagano M, Gauvreau K. Belmont: Duxbury Press,; Principles of Biostatistics. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- Nowell PC. Mechanisms of tumor progression. Cancer Res. 1986;46:2203–2207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb LA. Mutator phenotype may be required for multistage carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3075–3079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffinton GD, Doe WF. Depleted mucosal antioxidant defenses in inflammatory bowel disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;19:911–918. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)94362-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EW, Yong SL, Eiznhamer D, Keshavarzian A. Glutathione content of colonic mucosa: evidence for oxidative damage in active ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1088–1095. doi: 10.1023/a:1018899222258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie SJ, Baker MS, Buffinton GD, Doe WF. Evidence of oxidant-induced injury to epithelial cells during inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:136–141. doi: 10.1172/JCI118757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lih-Brody L, Powell SR, Collier KP, Reddy GM, Cerchia R, Kahn E, Weissman GS, Katz S, Floyd RA, McKinley MJ, Fisher SE, Mullin GE. Increased oxidative stress and decreased antioxidant defenses in mucosa of inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:2078–2086. doi: 10.1007/BF02093613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinouchi Y, Hiwatashi N, Chida M, Nagashima F, Takagi S, Maekawa H, Toyota T. Telomere shortening in the colonic mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:343–348. doi: 10.1007/s005350050094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill DP, Lengauer C, Yu J, Riggins GJ, Willson JK, Markowitz SD, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Mutations of mitotic checkpoint genes in human cancers. Nature. 1998;392:300–303. doi: 10.1038/32688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihan GA, Purohit A, Wallace J, Knecht H, Woda B, Quesenberry P, Doxsey SJ. Centrosome defects and genetic instability in malignant tumors. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3974–3985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens UM, Zijlmans JM, Poon SS, Dragowska W, Yui J, Chavez EA, Ward RK, Lansdorp PM. Short telomeres on human chromosome 17p. Nat Genet. 1998;18:76–80. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]