Abstract

Objective

Medical comorbidity is common among children with anxiety disorders; however, little is known about the impact of such comorbidity on mental and functional health outcomes. Even less is known about these problems in high-risk samples of youth.

Method

Participants in this study were youth with at least one DSM-IV anxiety disorder with a physical illness (N=77) and without a physical illness (N=73), as well as youth with at least one physical illness (but no anxiety disorder) (N = 438). These youth were recruited as part of the Patterns of Care study in which the original set of participants (N = 1715) were randomly sampled from one of five public sectors of care (e.g., juvenile justice, child welfare, mental health, alcohol and substance use services, school services for children with serious emotional disturbance) in San Diego County. Psychiatric diagnoses were assessed with a structured interview and three standardized measures were used to assess child health, emotional, and behavior functioning.

Results

At least half of children with anxiety disorders had a comorbid physical illness. Allergies and asthma were the most common comorbid physical illnesses. Children with anxiety disorders who had a comorbid physical illness exhibited greater levels of emotional problems, more somatic complaints, and more functional impairment than anxious children without a physical illness as well as than children with physical illness alone. Parents of children in the comorbid group also reported greater caregiver strain than the other two groups.

Conclusions

Children with anxiety disorders have high rates of chronic illnesses such as asthma and allergies. These children experience considerable impairment and likely have unique needs that may complicate usual care.

Keywords: children, anxiety, physical illness, medical, comorbidity

Data from clinical and community studies suggest that children with anxiety disorders frequently present with chronic illnesses and physical health problems including asthma,1-3 respiratory problems,4-5 gastrointestinal disorders,6 and headaches7. The nature of these relationships is likely bidirectional with anxiety contributing directly to physical illness through a general weakening of the immune system or as a byproduct of stress and less directly through unhealthy behaviors that are often exhibited by anxious youth (e.g., alcohol and drug use, poor sleeping and eating habits, and less exercise).8-9 Furthermore, physical illness can often trigger the onset or exacerbate existing anxiety symptoms, such as by increasing the presence of somatic sensations which through misinterpretation may lead to panic attacks or by providing stimuli for additional worries.

In general, symptoms of child anxiety are associated with educational underachievement, 10-11 low-self esteem and loneliness,12 and increased risk for later psychiatric disorders including depression, substance use, and suicide attempts.13-15 Chronic physical illnesses are also associated with significant impairment such as bodily pain and discomfort, school absences, activity limitations, lower social competence, higher use of medication and health care visits, as well as increased risk for internalizing and externalizing problems.16-21 Given the impairment independently associated with anxiety and chronic illness, the impact of having both a psychiatric and physical health condition is likely to be considerable.

While various cross-sectional studies have assessed the prevalence of anxiety and other psychiatric disorders in children with physical illness 22-25, few studies have investigated the mental health impact of comorbid medical illnesses among children with anxiety disorders. In one study, parents and children with anxiety disorders, recruited from an anxiety disorders clinic, reported higher levels of internalizing problems if the child had an additional diagnosis of asthma compared to children without asthma.26 There was also a trend for children with an additional diagnosis of asthma to present with higher levels of externalizing problems, which is consistent with other studies that have found associations between physical illnesses and oppositional defiant/conduct disorder.27-29

At present, most of the data about the relationship between child anxiety and physical illness come from specialty service settings (e.g., anxiety disorder clinics) and general community samples. However anxiety disorders are also found in public sectors of care including child welfare, juvenile justice, county mental health, alcohol and drug abuse services and special education services.30 These sectors represent a unique context given the increased risk for both physical and mental health problems due to greater exposure to risk factors such as caregiver mental health problems, unstable income, large family size, single parent household, and domestic and/or community violence.31-34 Understanding the prevalence and impact of medical comorbidity is critical to developing interventions for children who are both physically and psychiatrically ill. Such findings may facilitate detection of anxiety problems by medical professionals as well as more effective treatment planning for these children.

METHOD

Participants

The children in this study are part of the 1715 youths (ages 6-18) in the “Patterns of Care” (POC) study sample, a prevalence study of psychiatric illness in public sectors of care30. The 588 participants in this study included all children from this sample of 1715 youths who had any anxiety disorder (n =150) as well as all children who had a physical illness but no anxiety disorder (n =438); no additional exclusion criteria were used to select these children. For the purposes of this study we examined three groups: 1) 73 children with an anxiety disorder and a physical illness; 2) 77 children with an anxiety disorder without a physical illness, and 3) 438 children with a physical illness but no anxiety disorder. The original sample of 1715 youth were randomly selected from a list of all youths who were “active” in one or more of five San Diego County public sectors of care (alcohol and drug (AD), child welfare (CW), juvenile justice (JJ), mental health (MH), and public school services for youths with serious emotional disturbance (SED) during the first half of 1997 (total population = 12,662). Simple random sampling techniques with stratification by race/ethnicity and restrictiveness of care (aggregate versus home residence) were used. Data were obtained for 67% of the eligible sample in interviews completed between late 1997 and early 1999. Participants did not differ significantly from non-participants on age, gender, sector affiliation, or racial/ethnic distribution except that slightly fewer Asian-Americans participated compared to the eligible sample. 30

Approximately 63% of the 588 participants were male, the mean age was 14.09 years (SD = 3.07; range = 7-18) and 48.0% were non-Hispanic White, 21% Latino American, 19% African American, 5% Asian American/Pacific Islander, and 7% were biracial or classified as “other.” Most of the parent/caregiver informants were biological parents (68%) while others included foster, adoptive, step-parents, and professional caregivers.

Procedure and Measures

Written informed consent was obtained from the parent and assent from the youths. Parents and youths were interviewed individually regarding the youth’s mental health use, needs, and a variety of factors associated with mental health service use (e.g., caregiver strain, family income). Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish, depending on the participant’s preference. The interview procedures averaged three hours and parents and youth were compensated (up to $40) for their time. Interviewer training and reliability checks have been described previously. 30, 35 All study procedures were approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Boards at the participating academic institutions and the various public sector agencies.

Demographic information was obtained through a series of standardized questions for parent and child age, child gender, parent and child race/ethnicity and parent highest level of education, and annual family income. Race/ethnicity was coded as non-Hispanic white or Other; the Other category included Latino Americans, Asian American/Pacific Islanders, African Americans and individuals who identified as being part of more than one ethnic group. Parents’ highest level of education was coded as no high school, high school diploma, community college, or college degree.

Sector of Care

Children were recruited from one of five public sectors of care. The sectors specializing most in providing mental health care included county mental health, alcohol and drug services, and special education services and are grouped here as “mental health sectors.” The juvenile justice and child welfare sectors whose missions are focused less on the provision of mental health care are grouped as “non-mental health sectors.”

Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children - IV (DISC-IV)36

The computer assisted parent and youth versions of the DISC-IV assessed DSM-IV psychiatric diagnoses during the past year. The reliability and validity of the DISC are well supported.36 To reduce interview duration, and given some findings which suggest that children and adolescents are the best informants for internalizing disorders,37 the mood and anxiety modules were administered only to youths who were 9-18 and not their parents. However among children who were age 6-8, the modules were administered to both youth and their parents. This section included major depressive disorder, dysthymia, manic episode, generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, social phobia, post traumatic stress disorder, panic disorder, and obsessive compulsive disorder. The disruptive behavior disorder module was administered to both parent and youth (ages 6-18) informants and diagnoses were considered present if either respondent’s report met diagnostic criteria using the DISC-IV scoring algorithms (including diagnostic specific functional impairment). These modules included: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder.

Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Substance Abuse Module (CIDI-SAM)38-39

The CIDI-SAM was administered to youth between the ages of 13-18. The CIDI-SAM provides diagnostic information regarding abuse and dependence for alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, opioids, stimulants, hallucinogens as well as other illicit substances. The CIDI-SAM has been used with adolescents aged 13 years and older.40-42

Services Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA)43

Parent and youth versions of the SACA assessed use of different types of mental health and substance abuse services. SACA test-retest reliability for past year service use is excellent for parent informants and is good for youth informants over age 10.43 In this study, past year mental health service use included any inpatient (e.g., inpatient psychiatric hospital, residential treatment center/group home, and/or in-patient alcohol-drug treatment) or outpatient mental health care (e.g., visits to psychologist, counselor, community mental health clinic and/or partial hospitalization or day treatment program). Basic questions were also asked regarding psychotropic medication use in the past year and included the use of stimulants, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, anxiolytics (e.g., benzodiazepines), and anti-psychotics. Any mental health service use (i.e., inpatient or outpatient care) as well as any psychotropic medication use was dichotomized as “present” or “absent.”

Caregiver Strain Questionnaire (CGSQ)44

The CGSQ assesses parents’ perceptions of the burden or impact of caring for a child with emotional and behavioral problems. Relevant domains include economic burden, impact on family relations, disruption of family activities, impact on psychological adjustment of family members, stigma, anger and worry/guilt. Response options are based on a 5 point scale ranging from 1=not at all; 2=a little; 3=somewhat; 4=quite a bit and 5=very much. The reliability and validity of this 21 item self-report measure are good.44

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)45

The CBCL is a widely used parent report measure of emotional and behavior problems for children ages 6-18. There are three broad band scales (Total problems, Internalizing problems and Externalizing problems) and nine narrow band scales: 1) Anxiety-depression, 2) Withdrawn, 3) Somatic complaints, 4) Thought problems, 5) Attention problems, 6) Social problems, 7) Aggression, 8) Delinquent and 9) Sex problems. The internalizing problems scale includes emotional problems like anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal while the externalizing problems scale includes disruptive and acting out behaviors. Gender and age corrected norms are used and T-scores are presented. On most of the scales, T-scores greater than 65 indicate scores that are in a clinical range and warrant further evaluation.45

Child Health Questionnaire-Parent Form 28 (CHQ-PF28)46

The CHQ-PF28 is a shortened form of the original 50-item Child Health Questionnaire-Parent Form47-48 and assesses child health status and health-related quality of life (i.e., functional health outcomes) in domains of physical and psychosocial functioning. The instrument consists of 28 items measuring 12 domains of health related functioning including physical functioning, role-social limitations due to physical problems, general health perceptions, bodily pain/discomfort, family activities, role/social limitations due to emotional behavioral problems, parent impact time, parent impact emotion, self-esteem, mental health, family cohesion, and change in health. The parent impact items of the CHQ were not included in this study given that the Caregiver Strain Questionnaire was also included in this assessment battery. The CHQ-PF28 also includes a list of mental health, developmental, and medical conditions and asks “Have you ever been told by a teacher, school official, doctor, nurse or other health professional that your child has any of the following conditions?” Those conditions that were classified as physical illnesses included: Asthma, chronic allergies, chronic orthopedic, bone or joint problems, chronic respiratory lung or breathing trouble (not asthma), chronic rheumatic disease, diabetes, epilepsy (seizure disorder), and gastrointestinal problems (e.g., ulcers, chronic abdominal pain). Parents were also given the opportunity to report any other diagnosed illness using an open-ended response format that was subsequently coded. Items were summed and scores were recalibrated to a 0-100 scale with higher scores representing better functioning/adjustment.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted with SPSS statistical software.49 Chi square analyses and one way ANOVAs were used to assess sociodemographic and diagnostic differences across three groups: 1) Anxiety without a physical illness (subsequently referred to as anxiety alone); 2) Anxiety with comorbid physical illness, and 3) Physical illness with no anxiety (subsequently referred to as physical illness alone). MANCOVAs were used to examine the impact of a comorbid physical illness on three sets of variables; the three broad band scales of the CBCL, the eight narrow band scales of the CBCL, and the nine CHQ subscales. Covariates included those variables where there were significant differences across the three groups. A separate ANCOVA was conducted for the Caregiver Strain Questionnaire. Bonferroni corrections were used to control for the multiple univariate tests within the MANCOVAs.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the children with anxiety alone, anxiety with comorbid physical illness, and physical illness alone are presented in Table 1. There was a disproportionately higher number of boys in the anxiety with comorbid physical illness and physical illness alone groups when compared to the anxiety alone group. Family income was higher in the anxiety alone and physical illness alone groups than the anxiety comorbid with physical illness group. Age, parent level of education, and ethnic distribution were similar across the three groups as was the proportion of youth from mental health and non-mental health sectors. The use of specialty mental health services (i.e., inpatient and outpatient services) was similar across groups however there was a difference in psychotropic medication use with children in the anxiety comorbid with physical illness group using psychotropic medication most frequently. Diagnostically, there was a significantly higher proportion of children with externalizing disorders in the anxiety comorbid with physical illness group when compared to the other two groups. There were also a statistically higher proportion of mood disorders in the anxiety with and without physical illness groups when compared to the physical illness alone group. There was not a significant difference in the proportion of children with alcohol use or substance use disorders across the three groups. The distribution of specific anxiety disorders (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder, social phobia, separation anxiety) was similar across the anxiety alone and anxiety with comorbid physical illness groups as was the number of children with multiple anxiety disorders. Those variables which were significantly different across groups (gender, income, psychotropic medication use, disruptive behavior disorders, and depressive disorders) were included in the analyses as covariates.

Table 1.

Characteristics of POC youth with anxiety and physical illnesses (N =588)

| Anxious without physical illness n = 73 | Anxiety with physical illness n = 77 | No anxiety w/ physical illness n = 438 | Analysis | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Gender (male) | 43.8% | 61.0% | 66.7% | F = 14.2 | .001 |

| Child Age (years old) | 13.79 (SE = .40) |

14.03 (SE = .38) |

14.09 (SE =.14) |

F = .44 | .65 |

| Household income | 33,206 (SE = 4,040) |

20,750 (SE=1,926) |

30,885 (SE=1,296) |

F = 5.36 | .005 |

| Parent level of education No degree High school Community College University degree or more |

23.3.1% 45.2% 19.2% 12.3% |

26.3% 47.4% 19.7% 6.6% |

20.2% 44.1% 22.8% 12.9% |

F = 4.12 | .66 |

| Child Ethnicity Caucasian American Latino American African American Asian/Pacific Islander Other |

52.1% 26.0% 13.7% 6.8% 1.4% |

48.1% 18.2% 19.5% 7.8% 6.5% |

47.0% 21.2% 20.3% 3.7% 7.8% |

F = 9.99 | .27 |

| Sector (Mental Health) | 58.9% | 61% | 50% | F = 4.55 | .10 |

| Psychotropic Med use | 37.0% | 48.1% | 28.0% | 13.11 | .001 |

| Counseling Use | 75.3% | 64.9% | 62.1% | F = 4.8 | .09 |

| Separation Anxiety Disorder Social Phobia Generalized Anxiety Disorder Panic Disorder Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Obsessive Compulsive Disorder |

47.9% 28.8% 13.7% 2.7% 16.4% 19.2% |

48.1% 31.2% 10.4% 1.3% 26.0% 22.1% |

n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a |

F = .00 F = .10 F = .39 F = .40 F = 2.03 F = .19 |

.99 .75 .53 .52 .15 .66 |

| Number of comorbid anxiety disorders | 1.29 (SE=.07) |

1.39 (SE = .09) |

n/a | F= .81 | .37 |

| Comorbid depressive disorder | 28.4% | 34.7% | 5.3% | F = 71.33 | .001 |

| Comorbid disruptive disorder | 59.2% | 75.3% | 55.1% | F=11.1 | .004 |

| Comorbid substance use disorders (alcohol and illicit substances) | 21.4% | 27.4% | 20.1% | F=1.5 | .47 |

| Any alcohol use disorder | 14.5% | 21.1% | 15.9% | F = 1.11 | .57 |

Medical illness comorbidity

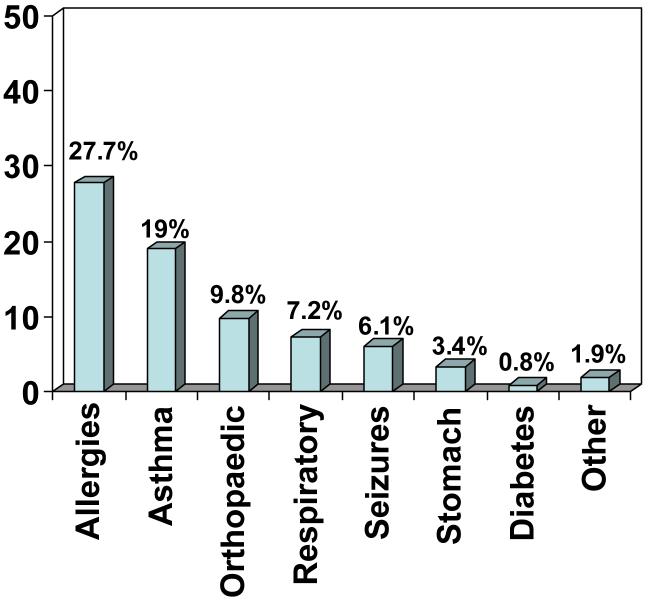

Figure 1 presents prevalence rates of various physical illness problems as assessed by the Child Health Questionnaire. Rates were highest for allergies and asthma and lowest for diabetes. In total, 51% of children with an anxiety disorder had a physical illness; 29% had one physical illness, 17% had two physical illnesses, 4% had three physical illnesses and 1% had more than three physical illnesses. Among all the children with any physical illness (n = 515) in the total sample of 1715 youth, 15% had an anxiety disorder.

Figure 1.

Bar graph representing percentages of children with anxiety disorder who had a specific physical illness.

Impact on CBCL Scores

Separate MANCOVAs were performed to examine the effects of anxiety alone, anxiety with comorbid physical illness, and physical illness alone on the broad band and narrow band scales of the CBCL with disruptive behavior disorders, depressive disorders, psychotropic medication use, family income, and child gender, entered as covariates. Multivariate analyses revealed a main effect on the broad band scales, Wilk’s F (6, 1042) = 2.76, p = .012 as well as the narrow band scales, Wilk’s F (16,1024) = 1.87, p =.02. As shown in Table 2 (with bonferroni corrections applied), parents of children in the anxiety with comorbid physical illness group reported significantly higher scores (suggesting more problems) on the internalizing problems scale and the total problems scale of the CBCL than parents of both children in the anxiety alone and physical illness alone groups. On the eight narrow band scales, children with an anxiety disorder comorbid with physical illnesses had higher scores on the somatic complaints and the anxiety/depression scales (see Table 3) than the other two groups. Children in the two anxiety groups had significantly higher scores (more problems) on the withdrawal scale than the physical illness alone group. There were no significant differences across groups for the thought problems, social problems, and behavior problems scales (aggression, delinquency, etc.).

Table 2.

CBCL broad band mean T-scores and standard errors for children with anxiety alone, anxiety comorbid with physical illness, and physical illness alone (alpha = .017)

| Anxiety alone Mean (SE) | Anxiety with physical illness Mean (SE) | Physical illness alone Mean (SE) | Analysis P value | Partial Eta2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Externalizing Problems | 60.36 (1.35) | 64.26 (1.33) | 61.76 (.53) | F = 2.33 P = .10 |

.009 |

| Internalizing Problems | 60.55 (1.43)a | 66.03 (1.41)b | 60.09 (.56)a | F = 7.43 P = .001 |

.028 |

| Total Problems | 62.07 (1.34)a | 67.02 (1.32)b | 62.61 (.52)a | F = 5.12 P = .000 |

.019 |

Note: Higher scores signify more problems. For each row, groups with same superscripts are not significantly different from each other.

Table 3.

CBCL narrow band mean T-scores and standard errors for children with anxiety alone, anxiety comorbid with physical illness, and physical illness alone (alpha =.006)

| Anxiety alone Mean (SE) | Anxiety with physical illness Mean (SE) | Physical illness alone Mean (SE) | Analysis P value | Partial Eta2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Withdrawn | 60.7 (1.21) ab | 63.58 (1.19) a | 59.38 (.47) b | F = 5.17 P = .006 |

.020 |

| Somatic Complaints | 58.60 (1.21)a | 65.00 (1.19)b | 60.60 (.47) a | F = 6.63 P =.001 |

.025 |

| Anxiety Depression | 62.83 (1.23) a | 67.22 (1.21) b | 61.40 (.48) a | F = 9.57 P = .001 |

.036 |

| Social Problems | 61.67 (1.19) | 63.36 (1.17) | 61.13 (.46) | F = 1.51 P = .223 |

.006 |

| Thought problems | 61.18 (1.19) ab | 64.51 (1.22) a | 59.72 (.49) b | F= 3.68 P = .026 |

.014 |

| Attention | 62.45 (1.20) | 65.17 (1.19) | 62.29 (.47) | F = 2.49 P = .08 |

.010 |

| Delinquent | 63.15 (1.20) | 66.27 (1.19) | 62.17 (.47) | F = 2.05 P = .129 |

.008 |

| Aggressive | 62.05 (1.19) | 64.48 (1.21) | 61.90 (.49) | F = 1.61 P = .191 |

.006 |

Note: Higher scores signify more problems. For each row, groups with same superscripts are not significantly different from each other.

Impact on CHQ Scores

A MANCOVA was performed with the nine subscales of the CHQ as the dependent variables and comorbid disruptive behavior disorders, comorbid depressive disorders, psychotropic medication use, family income, and child gender entered as covariates. As shown in Table 4, a main effect was found, Wilk’s F (18,1034) = 3.47, p = .001, and univariate tests were significant for three of the nine CHQ subscales; bonferroni corrections applied. Children who had an anxiety disorder comorbid with a physical illness reported significantly lower scores (indicating more impairment) on role functioning due to emotional and behavior problems than the anxiety alone and physical illness alone groups. The two anxiety groups (i.e., anxiety with and without physical illness) also reported more depression and anxiety than the physical illness alone group while both the physical illness groups (i.e., anxiety with comorbid physical illness and physical illness alone) reported more bodily pain than the anxiety alone group. There were no significant differences for the other comparisons.

Table 4.

Child Health Questionnaire-Parent Form-28 subscale mean scores (0-100 scale) and standard errors for children with anxiety alone, anxiety comorbid with physical illness, and physical illness alone (alpha =.0056)

| Anxiety alone Mean (SE) | Anxiety with physical illness Mean (SE) | Physical illness alone Mean (SE) | Analysis P value | Partial Eta2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 90.87 (3.29) | 81.52 (3.22) | 86.13 (1.28) | F = 2.15 P =.118 |

.008 |

| Role functioning limitations due to physical health | 96.84 (3.35) | 87.28 (3.28) | 88.51 (1.30) | F = 2.94 P = .05 |

.011 |

| Bodily pain | 84.04 (3.67)a | 65.32 (3.59) bc | 70.49 (1.42)c | F = 7.82 P = .000 |

.029 |

| General health perceptions | 62.72 (3.12) | 58.00 (3.05) | 60.46 (1.21) | F = .61 P = .54 |

.002 |

| General Behavior (Acting Out) | 53.12 (2.84) a | 41.87 (2.77) b | 47.92 (1.10) a | F = 4.21 P = .015 |

.016 |

| Mental health (Anxiety and Depression) | 53.70 (2.68) a | 46.64 (2.62) a | 60.93 (1.04) b | F = 18.32 P = .000 |

.049 |

| Role functioning limitations due to emotional problems | 66.06 (4.70) a | 48.67 (4.60) b | 68.02 (1.83) a | F = 7.38 P = .001 |

.027 |

| Self-esteem | 58.54 (3.07) | 54.84 (3.00) | 60.91 (1.19) | F = 1.76 P = .173 |

.007 |

| Family Cohesion | 56.48 (3.61) | 54.78 (3.54) | 56.50 (1.40) | F = .10 P = .90 |

.00 |

Note: Lower scores reflect poorer functioning. For each row, groups with same superscripts are not significantly different from each other.

Impact on Caregiver Strain

Although the full table of results is not presented here due to space limitations, an ANCOVA, with group membership as the independent variable and disruptive behavior disorders, depressive disorders, psychotropic medication use, family income, and child gender, as covariates, revealed that children with anxiety and comorbid physical illness had higher scores on parent reported caregiver strain (M = 2.67, SE = .10) than children with anxiety alone (M = 2.29, SE = .10) as well as than children with physical illness alone (M = 2.38, SE = .04), F (2,536) = 6.48, p = .002. The anxiety alone group was not significantly different form the physical illness alone group.

DISCUSSION

Anxiety disorders are common among children recruited from public sectors of care. In this study, approximately 8.7% of children had an anxiety disorder which is similar to estimates of 6-10% found in the general population.50-51 Estimates of physical illnesses among children with anxiety disorders were higher than general population estimates. For example, in the general population, estimates of asthma are 13% and chronic allergies such as hay fever, respiratory allergies, and other allergies range from 10.4-13.0%.52 Similar rates have been found in poor children.52 In this study, the prevalence rate for comorbid asthma was 19% and 27.7% for any chronic allergy (questions regarding specific types of allergies were not asked). The fact that 51% of children with an anxiety disorder reported any physical illness further supports a possible association between anxiety and physical illness. Furthermore, a prevalence rate of 15% for anxiety disorders among patients with any physical illness is somewhat higher than general population estimates of anxiety disorders and may be partially explained by the high-risk nature of this sample.

Given the relationship between anxiety and physical illness, the primary aim of this study was to examine the impact of having both a psychiatric and medical condition in a high risk sample. Findings from this study suggest that having an anxiety disorder comorbid with a physical illness is associated with more severe levels of emotional problems as well as greater functional impairment than having an anxiety disorder or physical illness alone. Children in the comorbid group reported greater total problems in general, and internalizing problems in particular, as well as more somatic complaints and higher levels of anxiety and depression than children with anxiety alone or physical illness alone. Important to note, on most of the CBCL scales, children in the comorbid anxiety with physical illness condition had scores which met the established clinical cutoff of 65 whereas those in the anxiety and physical illness alone groups had scores that were below this cutoff and either in the subthreshold or nonclinical range. Children who score in the clinical range on these scales are often recommended for further evaluation and possible treatment.

It is likely that the relationship between anxiety as well as other psychiatric problems (e.g., depression, and behavioral disorders) and chronic physical illness is bidirectional with each disorder influencing the other through factors such as self-care (e.g., diet, exercise and sleep), common biobehavioral risks (e.g., stress), and biological processes (e.g., immune functioning).53-55 For example, chronic worry and stress/anxiety may decrease immune functioning, making an individual more susceptible to viral infections, and likewise increasing the severity of allergies and asthma.56-57 Chronic worry and stress also may contribute to gastrointestinal problems such as the formation or worsening of duodenal ulcers. In other cases, having respiratory problems such as asthma may make a child more uncomfortable about being away from their parents, thereby increasing calamitous thoughts and anxiety about separation. Additionally, somatic symptoms attached to an actual illness may provide more frequent triggers for panic attacks and subsequent anxiety disorders. In general, the additive and reciprocal effect of having two distinct disorders likely leads to greater actual and perceived distress both in the physical (e.g. somatic complaints) and emotional domains (e.g., depression/anxiety).

In addition to greater symptom severity, children with anxiety and comorbid physical illnesses also reported more school and social impairment due to emotional and behavioral problems than children with either anxiety or physical illness alone. Similar to symptom severity, the effect of having both conditions may have an additive effect on functional impairment. Role functioning at school is often affected by anxiety related school avoidance, low self-esteem, and difficulties with concentration. Physical illnesses can result in further impairment due to illness related absences, concentration difficulties, bodily pain, and medication regimens. With regard to social impairment, anxiety and physical illness may contribute to lower perceptions of competence regarding physical appearance (particularly if signs of physical illness are visible), athletic competence, and social acceptance, leading to varying forms of avoidance and social maladjustment.20, 58-59 Physical conditions also may lead to necessary restrictions on physical/social activities, which limit social interactions and further affect perceptions of social competence. Again, the impact of having both conditions is worse than the impact associated with either disorder alone.

On a final measure of impact (the Caregiver Strain Questionnaire), parents of children with anxiety comorbid with physical illnesses reported more caregiver strain related to child’s behavioral/emotional functioning than parents of children in the anxiety alone and physical illness alone groups. CGSQ items assess economic burden, impact on family relations, disruption of family activities, impact on psychological adjustment of family members, stigma about mental health problems, anger, worry, and guilt stemming from the child’s emotional or behavioral problem. The greater severity of psychiatric symptoms (e.g. higher levels of depression, anxiety, somatic complaints, and functional impairment as measured by the CBCL and CHQ) in the comorbid group may lead to increased levels of caregiver strain, including possible restricted family activities, parent disagreement about ways to cope with child behaviors, frustration with the child, parental self-blame, as well as worry regarding the child’s emotional and behavioral functioning. In addition, severity is often a predictor of service use,60-62 so it may be that anxious children with comorbid physical illnesses use services more frequently leading to additional parent impact, economic burden, and stress. These analyses controlled for potential confounds such as demographic characteristics and other comorbid clinical conditions, including diagnoses of disruptive and depressive disorders.

The possible implications of these results are numerous. First of all, children with comorbid anxiety and physical problems are likely to present with more severe levels of anxiety, depression and somatic complaints than children with only an anxiety disorder or only a physical illness. Consequently, these children may seek additional reassurance and/or require more intensive services. Interventions may need to provide coping skills to help deal with the consequences of having medical problems, social skills training to address potentially greater social impairment in this group, and training in self-regulation relaxation strategies that can impact both the child’s medical and psychological health. Additionally, anxiety interventions may need to be adapted to be more inclusive of the physical health needs of children and to ensure that therapeutic techniques (e.g., exposure to anxiety inducing triggers, deep breathing, etc.) are not contraindicated given a child’s medical condition. To date, treatment outcome data for children with anxiety disorders and comorbid medical illnesses are scarce. Among adults, data from at least one treatment study, suggest that patients with an anxiety disorder respond equally well to an anxiety intervention regardless of their level of comorbid medical illness.63 However, in this study, patients with medical illness started off with more severe psychiatric symptoms and likely required more intensive treatment to achieve full remission. A team based approach where pediatricians, mental health providers, and other allied professionals work collaboratively may be necessary to meet the multiple and sometimes complex needs of children with anxiety and comorbid physical illnesses. Limitations

The participants in this study are from San Diego County and therefore findings may not be generalizable to other regions. Also, this is a high-risk sample of youth who have experienced greater socioeconomic disadvantage and stressful experiences. Consequently, study findings may not be consistent with those from general community and clinic samples of children with anxiety disorders.

Substantial comorbidity existed in this sample, making it difficult to study the effects of physical illness among children with only anxiety disorders. As a result it was necessary to statistically control for potential clinical confounds such as co-existing externalizing and depressive disorders. In addition, we also controlled for potential sociodemographic confounds such as annual household income, child gender, and medication use when assessing impact on functioning. It is possible however that we did not control for all variables that may have been important such as parent health status, child abuse, exposure to violence and other life stressors.

Lastly, we used a measure of health status and functioning that was based on parent report, did not query all possible physical illnesses, and did not specify severity of each illness. The CHQ is a well-established measure of child health functioning and has sound psychometric properties.46,48 Parent report has been used frequently in surveys of child health64 and although not optimal to rely on parent report alone, was conducive to the time, financial and subject burden constraints of this study. Although the list of physical illnesses was not as extensive as it could have been, parents were given the opportunity to report any other illnesses in an open-ended response format that was subsequently coded. Differences between groups on impairment and functioning may have been greater if we had only included children with severe physical illness, however in previous studies, findings supporting a relationship between illness severity and psychiatric symptoms have been mixed.65-66 As demonstrated by this study, children with any type of comorbid physical illness, regardless of severity, are likely to present with greater emotional and social impairment than children without physical illnesses.

Conclusions

While existing theoretical models begin to explain the co-occurrence of psychiatric and physical disorders, the functional impact of having both conditions has received little attention. This study suggests that children with comorbid psychiatric and medical conditions will often present with more severe symptomatology in varying domains of emotional functioning as well as greater impairment in school and social functioning. Given epidemiological data suggesting that certain medical illnesses (e.g., asthma, allergies, gastrointestinal disorders) are common among children with internalizing disorders,1-7 pediatric subspecialty clinics, such as allergy, pulmonology and gastroenterology may be logical points of detection and service delivery. Screening efforts to detect anxiety disorders among children in these settings may lead both to better medical and mental health outcomes. Multidisciplinary efforts will likely be necessary to optimize treatment and meet the diverse needs of children with anxiety and comorbid physical illnesses. The effectiveness and feasibility of collaborative interventions which include medical, psychiatric, and psychological subspecialties awaits further research.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIMH grant U01 MH55282 to Dr. Hough, NIMH grant K01 MH072952 to Dr. Chavira, and NCMHD grant #P60MD00220 to Dr. Daley.

REFERENCES

- 1.Feldman JM, Ortega AN, McQuaid EL, et al. Comorbidity between asthma attacks and internalizing disorders among Puerto Rican children at one-year follow-up. Psychosomatics. 2006;47:333–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.4.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasler G, Gergen PJ, Kleinbaum DG, et al. Ashtma and panic in young adults: A twenty year prospective community study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:1224–1230. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200412-1669OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ortega AN, McQuaid EL, Canino G, et al. Association of psychiatric disorders and different indicators of asthma in island Puerto Rican children. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38:220–6. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0623-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harter MC, Conway KP, Merikangas KR. Associations between anxiety disorders and physical illness. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;253:313–320. doi: 10.1007/s00406-003-0449-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koltek M, Wilkes TC, Atkinson M. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in an adolescent inpatient unit. Can J Psychiatry. 1998;43:64–68. doi: 10.1177/070674379804300107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campo JV, Bridge J, Ehmann M, et al. Recurrent abdominal pain, anxiety, and depression in primary care. Pediatrics. 2004;113:817–824. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egger HL, Costello EJ, Erkanli A, et al. Somatic complaints and psychopathology in children and adolescents: stomach aches, musculoskeletal pains, and headaches. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:852–860. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199907000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson SE, Cohen P, Naumova EN, et al. Association of depression and anxiety disorders with weight change in a prospective community-based study of children followed up into adulthood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:285–91. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson SE, Cohen P, Naumova EN, et al. Relationship of childhood behavior disorders to weight gain from childhood into adulthood. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2006;6:297–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Ameringen M, Mancini C, Farvolden P. The impact of anxiety disorders on educational achievement. J Anxiety Disord. 2003;17:561–571. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM. Life course outcomes of young people with anxiety disorders in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1086–1093. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200109000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fordham K, Stevenson-Hinde J. Shyness, friendship quality, and adjustment during middle childhood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40:757–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Essau CA, Conradt J, Petermann F. Course and outcome of anxiety disorders in adolescents. J Anxiety Disord. 2002;16:67–81. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(01)00091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, et al. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:56–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stein MB, Fuetsch M, Mueller N, et al. Social anxiety disorder and the risk of depression: A prospective community study of adolescents and young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:251–256. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cadman D, Boyle M, Szatmari P, et al. Chronic illness, disability, and mental and social well-being: Findings of the Ontario Child Health Study. Pediatrics. 79:805–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gortmaker SL, Walker DK, Weitzman M. Chronic conditions, socioeconomic risks, and behavioral problems in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1990;85:267–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson Allen PL, Vessey JA. Primary care of a child with a chronic condition. Mosby; St. Louis, MO: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drotar D. Relating parent and family functioning to the psychological adjustment of children with chronic health conditions: What have we learned? What do we need to know? J Pediatr Psychol. 1997;22:149–165. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/22.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lavigne JV, Faier-Routman J. Psychological adjustment to pediatric physical disorders: A meta-analytic review. J Pediatr Psychol. 1992;17:133–157. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/17.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kashani JH, Barbero GJ, Wilfley DE, et al. Psychological concomitants of cystic fibrosis in children and adolescents. Adolescence. 1988;23:873–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katon W, Lozano P, Russo J, McCauley E, Richardson L, Bush T. The prevalence of DSM-IV anxiety and depressive disorders in youth with asthma compared with controls. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41:455–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vila G, Nollet-Clemencon C, de Blic J, Mouren-Simeoni MC, Scheinmann P. Prevalence of DSM IV anxiety and affective disorders in a pediatric population of asthmatic children and adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2000;58:223–231. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ortega AN, Huertas SE, Canino G, Ramirez R, Rubio-Stipec M. Childhood asthma, chronic illness, and psychiatric disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190:275–281. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200205000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodwin RD, Pine DS, Hoven CW. Asthma and panic attacks among youth in the community. J Asthma. 2003;40:139–145. doi: 10.1081/jas-120017984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meuret AE, Ehrenreich JT, Pincus DB, et al. Prevalence and correlates of asthma in children with internalizing psychopathology. Depress Anxiety. 2006;23:502–508. doi: 10.1002/da.20205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bardone AM, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, et al. Adult physical health outcomes of adolescent girls with conduct disorder, depression, and anxiety. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:594–601. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199806000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delligatti N, Akin-Little A, Little S. Conduct disorder in girls: Diagnostic and intervention issues. Psychology in the Schools. 2003;40:183–192. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dobkin P, Tremblay R, McDuff P. Can childhood behavioural characteristics predict adolescent boys’ health? A nine-year longitudinal study. J Health Psychol. 1997;2:445–456. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garland AF, Hough RL, McCabe KM, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in youths across five sectors of care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:409–18. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen E, Martin AD, Mathews KA. Understanding health disparities: The role of race and socioeconomic status in children’s health. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:702–708. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.048124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garland AF, Hough R, Landsverk J, et al. Multi-sector complexity of systems of care for youth with mental health needs. Children’s Services: Social Policy, Research and Practice. 2001;4:123–140. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glisson C, Hemmelgarn A. The effects of organizational climate and interorganizational coordination on the quality and outcomes of children’s service systems. Child Abuse Negl. 1998;22:401–421. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Starfield B, Robertson J, Riley AW. Social class gradients and health in childhood. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2:238–246. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2002)002<0238:scgahi>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aarons GA, Brown SA, Hough RL, et al. Prevalence of adolescent substance use disorders across five sectors of care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:419–26. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, et al. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cantwell DP, Lewinsohn PM, Rhode P, et al. Correspondence between adolescent report and parent report of psychiatric diagnostic data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;36:610–619. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199705000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cottler LB, Robins LN, Helzer JE. The reliability of the CIDI-SAM: a comprehensive substance abuse interview. Br J Addict. 1989;84:801–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robins LN, Cottler LB, Babor T. The WHO/ADAMHA Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Substance Abuse Module (SAM) Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine; St Louis: 1990. http://epi.wustl.edu/epi/EPlasseSAM.html. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crowley TJ, Mikulich SK, MacDonald M, et al. Substance-dependent, conduct-disordered adolescent males: severity of diagnosis predicts two-year outcome. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;49:225–237. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riggs PD, Baker S, Mikulich SK, et al. Depression in substance-dependent delinquents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:764–771. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199506000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whitmore EA, Mikulich SK, Thompson LL, et al. Influences on adolescent substance dependence: conduct disorder, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and gender. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;47:87–97. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horwitz SM, Hoagwood K, Stiffman AR, et al. Reliability of the Services Assessment for Children and Adolescents. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1088–1094. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.8.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brannan AM, Heflinger GA, Bickman L. The Caregiver Strain Questionnaire: Measuring the impact on the family of living with a child with serious emotional disturbance. J Emotional Behav Disord. 1997;5:212–222. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raat H, Botterweck AM, Landgraf JM, et al. Reliability and validity of the short form of the child health questionnaire for parents (CHQ-PF28) in large random school based and general population samples. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;59:75–82. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.012914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Landgraf JM, Abetz L, Ware JE. The CHQ user’s manual. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; Boston: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Langraf JM, Maunsell E, Speechley KN, et al. Canadian-French, German and UK versions of the child health questionnaire: methodology and preliminary item scaling results. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:433–445. doi: 10.1023/a:1008810004694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.SPSS for Windows, Rel. 14.0.2. SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Costello EJ, Shugart MA. Above and below the threshold: Severity of psychiatric symptoms and functional impairment in a pediatric sample. Pediatrics. 1992;90:359–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Briggs-Gowan MJ, Horwitz SM, Schwab-Stone M, et al. Mental health in pediatric settings: Distribution of disorders and factors related to service use. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:841–849. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200007000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bloom B, Dey AN, National Center for Health Statistics Summary Health Statistics for U.S. Children: National Health Interview Survey, 2004. Vital Health Stat. 2006;10(227) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anderson SE, Cohen P, Naumova EN, et al. Association of depression and anxiety disorders with weight change in a prospective community-based study of children followed up into adulthood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:285–91. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Katon W, Sullivan MD. Depression and chronic medical illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51:12–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Katon W, von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, et al. Behavioral and clinical factors associated with depression among individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:914–920. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.4.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goodwin RD, Castro M, Kovacs M. Major depression and allergy: does neuroticism explain the relationship? Psychosom Med. 2006;68:94–98. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000195797.78162.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Richardson LP, Lozano P, Russo J, et al. Asthma symptom burden: relationship to asthma severity and anxiety and depression symptoms. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1042–1051. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Varni JW, Setoguchi Y, Rappaport LR, et al. Psychological adjustment and perceived social support in children with congenital/acquired limb deficiencies. J Behav Med. 1992;15:31–44. doi: 10.1007/BF00848376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thompson RJ, Hodges K, Hamlet KW. A matched comparison of adjustment in children with cystic fibrosis and psychiatrically referred and nonreferred children. J Pediatr Psychol. 1990;15:745–759. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/15.6.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alegria M, Canino G, Lai S, et al. Understanding caregivers’ help-seeking for Latino children’s mental health care use. Med Care. 2004;42:447–455. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000124248.64190.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Angold A, Messer SC, Stangl D, et al. Perceived parental burden and service use for child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:75–80. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Essau CA. Frequency and patterns of mental health services utilization among adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2005;22:130–137. doi: 10.1002/da.20115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roy-Byrne PP, Stein MB, Russo J, et al. Medical illness and response to treatment in primary care panic disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:237–43. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goodwin RD. Asthma and anxiety disorders. Adv Psychosom Med. 2003;24:51–71. doi: 10.1159/000073780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Richardson LP, Lozano P, Russo J, et al. Asthma symptom burden: relationship to asthma severity and anxiety and depression symptoms. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1042–51. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wamboldt MZ, Krafchick D, Fritz G. Relationship of asthma severity and psychological problems in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:943–950. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199809000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]