Abstract

Parents commonly label objects on television and for some programs, verbal labels are also provided directly via voice-over. The present study investigated whether toddlers’ imitation performance from television would be facilitated if verbal labels were presented on television via voice-over or if they were presented by parents who were co-viewing with their toddlers. Sixty-one 2-year-olds were randomly assigned to one of 4 experimental groups (voice-over video, parent video, parent video no label, parent live) or to a baseline control condition. Toddlers were tested with novel objects after a 24 hr delay. Although, all experimental groups imitated significantly more target actions than the baseline control group, imitation was facilitated by novel labels regardless of whether those labels were provided by parents or by voice-over on television. These findings have important implications for toddler learning from television.

Keywords: television, toddler, imitation, verbal labels, repetition

Toddlers live in a media rich environment. Beginning during the 1990’s and increasing at an exponential rate, programming such as Baby Einstein is being produced specifically for infants and toddlers (Garrison & Christakis, 2005). Annual sales of these infant-directed videos reached $100 million in 2004 (Garrison & Christakis, 2005) and toddlers are regularly exposed to these programs. Recent nationwide surveys in the United States report that between 74–90% of infants are exposed to television before age 2 and those exposed to television spend between 1–2 hours per day watching television and videos/DVDs (Rideout & Hamel, 2006; Rideout, Vandewater, & Wartella, 2003; Zimmerman, Christakis, & Meltzoff, 2007a, b). Such statistical data has not been reported in other nations/regions to date.

High levels of exposure to television occur despite the fact that the American Association of Pediatrics (AAP, 1999) has recommended no television exposure before the age of 2 years. Consistent with the AAP recommendation, a small but growing body of research has demonstrated that infants and toddlers learn less information from television than from live face-to-face interactions; a finding referred to as the video deficit effect (Anderson & Pempek, 2005; Barr, in press). Deferred imitation is often used to assess young children’s ability to learn from television. In the deferred imitation task, an experimenter performs an action or actions and the infant’s ability to reproduce that action or actions is assessed following a delay. Deferred imitation studies have demonstrated that 12- to 30-month-olds consistently imitate significantly fewer actions from television than from a live demonstration (Barr & Hayne, 1999; Hayne, Herbert, & Simcock, 2003; Hudson & Sheffield, 1999; McCall, Parke, & Kavanaugh, 1977). For example, Hayne and colleagues (2003) found that both 24- and 30-month-old toddlers in the video demonstration condition imitated significantly fewer actions than infants in the live demonstration condition when they were tested either immediately or after 24 hours. The video deficit is also exhibited in object search tasks (Deocampo & Hudson, 2005; Schmitt & Anderson, 2002; Suddendorf, 2003; Troseth, 2003; Troseth & DeLoache, 1998), emotion processing tasks with infants (Mumme & Fernald, 2003) and language based tasks with infants, toddlers (Kuhl, Tsao, & Liu, 2003), and preschoolers (Sell, Ray, & Lovelace, 1995). Similarly, researchers using event-related potentials (ERPs) have demonstrated that 18-month-olds process 2D images more slowly than they process 3D objects, recognizing a familiar 3D object very early in the attention process and recognizing a 2D digital photo significantly later (Carver, Meltzoff, & Dawson, 2006). The video deficit effect may be due to slower processing of information or increase in cognitive load incurred due to the need to transfer information from 2D encoding to 3D test conditions.

Under certain circumstances, however, the video deficit effect can be ameliorated. In one deferred imitation study, for example, repetition of the target actions on television enhanced imitation of two 3-step action sequences by 12- to 21-month-olds (Barr, Muentener, Garcia, Chavez, & Fujimoto, 2007). Presumably repetition enhances encoding and retrieval of the 2D attributes. It is important to note, that differences in looking time could not account for these findings. The authors reported that % looking time data did not vary as a function of age or experimental condition. Even though the video demonstration was longer, overall % looking time was not significantly less than the live presentation. These findings suggest that repetition allows for additional processing which enhances comprehension of material (Barr & Hayne, 1999; Hudson & Sheffield, 1999; Schmitt & Anderson, 2002; Suddendorf, 2003).

Other factors may also potentially ameliorate the video deficit effect. Television producers include segments on prerecorded videotapes and DVDs that encourage parents to co-view with their infants and toddlers (Garrison & Christakis, 2005). In a recent study we found that parental-mediation influences infant interaction patterns and looking time during infant-directed programming (Barr, Zack, Garcia, & Muentener, 2008). A higher proportion of parent questions and labels/descriptions predicted higher infant looking time and greater infant responsiveness to video content. This finding suggests that parent labeling during co-viewing may facilitate learning from television. Furthermore, Krcmar, Grela and Lin (2007) reported that 15- to 24-month-olds were able to learn vocabulary from television if the adult spoke directly to the infant and there was minimal additional stimulation. Infants had more difficulty, however, with voice-overs until they were approximately 22 months old when they were able to also learn vocabulary from clips accompanied by voice-over. Studies conducted with older children, directly compared the effects of adult labeling and voice-over on children’s comprehension of a prosocial cartoon (Watkins, Calvert, Huston-Stein & Wright, 1980). They found that the 3- to 7-year-olds remembered significantly more information in the adult labeling condition than in the voice-over condition. The present study will directly compare the effect of parent labeling and voice-over labeling on toddlers’ imitation.

In the present experiment, we assessed the effect of providing novel labels on deferred imitation from television using a procedure originally described by Herbert and Hayne (2000). Herbert and Hayne (2000) examined whether toddlers could use an adult’s language to help them to solve a difficult deferred imitation problem. Groups of 18- and 24-month-olds were randomly assigned to the experimental or baseline control condition. Using a within subjects design, the experimenter demonstrated the target actions and provided a novel label for one stimulus set (a rattle or a wooden animal) but not the other. After a 24 hour delay, toddlers were presented with a novel version of each set of stimuli and the label for one stimulus set. The baseline control condition was simply provided with the stimuli at the time of the test. The verbal label enhanced generalization performance by the 24-month-olds but not the 18-month-olds. When no label was provided, performance did not exceed baseline at either age. The authors concluded that verbal labels enhance cognitive flexibility by 24 months at both encoding and retrieval.

In the past, researchers investigating imitation from television have always tested toddlers with the same object that was used to demonstrate the target actions on television. Studying generalization following televised demonstrations is important for both practical and theoretical reasons. First, findings from deferred imitation studies using live models have shown systematic age-related differences in generalization by 6- to 30-month-olds (Barnat, Klein, & Meltzoff, 1996; Hanna & Meltzoff, 1993; Hayne, Boniface, & Barr, 2000; Hayne, MacDonald, & Barr, 1997; Herbert & Hayne, 2000). For example, in the absence of a verbal label, generalization to a novel rattle or wooden toy did not occur until 30-months of age (Herbert & Hayne 2000). Therefore, examining generalization performance from television is interesting because it further examines cognitive flexibility under challenging representational circumstances (see also Simcock & Dooley, 2007 for a similar argument regarding book reading). Can toddlers transfer information from television and can they transfer information across objects? Second, from an ecological and practical point of view, toddlers are not likely to encounter exactly the same object in their homes as they see on television and an ability to generalize to novel yet functionally similar objects would enhance the potential educational value of television for toddlers. Furthermore, given that parents typically provide labels or voice-over including verbal labels during toddler-directed programming then it would be useful to examine whether toddlers are using this language to solve real world problems.

The present study examined whether toddlers can use language either learned from a parent or a voice-over to solve a difficult imitation task from television. There were two key questions for the present study. First, would repetition alone ameliorate a video deficit effect when generalization was being tested? Second, if the video deficit effect persisted, would verbal cues together with repetition ameliorate the video deficit? Toddlers were randomly assigned to four experimental conditions (live parent label, video parent label, video voice-over label, video no label). After a 24-hr delay, toddlers were tested with 2 sets of novel stimuli. Performance of the experimental conditions was compared to that of an age-matched baseline control condition.

Method

Participants

Sixty-one 24-months-olds (M = 24.47 months, SD = 8.63 days; 26 boys and 33 girls) and their caregivers (98% mothers, 2% fathers) were recruited through commercial mailing lists and by word-of-mouth. Participants were African-American (n = 2), Latino (n = 8), Caucasian (n = 43), and of mixed descent (n = 7). The majority of toddlers were from middle- to upper-class, highly educated families. Their parents’ mean educational attainment was 17.3 years (SD = 1.6) based on 100% of the sample reporting, and their mean rank of socioeconomic status (Nakao & Treas, 1992) was 79.4 (SD = 11.1) based on 90% of the sample reporting. Toddlers (n = 12/group) were randomly assigned to five conditions; live 3x parent label, video 6x parent label, video 6x parent no label, video 6x voice-over, and baseline conditions (see Table 1). Nineteen additional toddlers were excluded from the final sample due to equipment failure or experimenter error (n = 9), parental or sibling interference (n = 4), and refusal to play or crying (n = 6).

Table 1.

The presentation mode, number of demonstrations, provision of label and label provider as a function of experimental condition

| Condition | Presentation mode | Number of demonstrations | Label provided | Who provided label? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live 3x parent label | Live | 3 | Yes | Parent |

| Video 6x parent label | Video | 6 | Yes | Parent |

| Video 6x parent no label | Video | 6 | No | Parent |

| Video 6x voice over | Video | 6 | Yes | Voice over |

| Baseline | - | - | - | - |

Apparatus

The stimuli used in the present experiment were identical to those used by Herbert and Hayne (2000) and Barr et al. (2007). There were two types of stimuli (rattle and animal) and two versions of each type. The two versions of each stimulus set were constructed in such a way that the exact same target actions could be performed with each version (see Table 2).

Table 2.

The Three Target Actions Each Set Of Stimuli

| Stimulus set | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Rattle | Push block through diaphragm into jar | Put stick on jar attaching with Velcro | Shake stick to make noise |

| Red Rattle | Put the bead in the jar | Push the stick into the top of the jar | Shake stick to make noise |

| Rabbit | Pull lever in a circular | Place eyes on face | Put the carrot in the |

| motion to raise ears | attaching with Velcro | rabbit’s “mouth” | |

| Monkey | Pull lever in a circular motion to raise ears | Place eyes on face attaching with velcro | Put the banana in the monkey’s “mouth” |

The stimuli for the green rattle consisted of a green stick (12.5 cm long) attached to a yellow plastic lid (9.5 cm in diameter) with velcro attached to the underside of the lid, a blue octagonal bead (3 cm in diameter × 2.5 cm in height), and a clear plastic square cup with velcro around the top (5.5 cm in diameter × 8 cm in height). The opening of the plastic cup (3.5 cm in diameter) was covered with a 1 mm black rubber diaphragm, with 16 cuts radiating from the centre. The stimuli for the red rattle consisted of a red wooden stick (12.5 cm long) with a plug on the end which fitted into a clear plastic ball with a hole cut in the top (4 cm in diameter), and a clear plastic bead (2 cm in diameter) with a blue ring (2.5 cm diameter).

The stimuli for the rabbit toy consisted of two plastic eyes (3 × 2 cm) attached to a 9 × 6 cm piece of plywood with velcro on the back, a 12 cm orange wooden carrot with green string attached to the top, a white circle of wood (the head, 15 cm in diameter) mounted horizontally on a white rectangular wooden base (30 × 20 cm). A 3 cm (in diameter) hole was drilled at the bottom of the head and a 5 × 15 cm piece of white velcro was attached to the top of the head. Two white “ears” (20 × 5 cm) decorated with stripes of pink felt were hidden behind the head. A 10 cm wooden stick attached to the top of the right ear allowed the ears to be pulled up from behind the head in a circular motion to a point above the head. The stimuli for the monkey toy consisted of two plastic eyes (2.5 cm in diameter) with eyelashes that were attached to a piece of brown plywood in the shape of two diamonds joined at the center (11.5 cm in width, 6.5 cm in height), with brown velcro on the back, a 20.5 cm yellow plastic banana, and a brown wooden head and shoulders shape mounted horizontally on a brown rectangular wooden base (22 × 38 cm). A 4 cm hole was drilled at the bottom of the head and a 5 × 18 cm piece of brown velcro was attached to the top of the head. Two brown ears (3.5 × 7 cm) decorated with a piece of yellow felt were hidden behind the head. A 3 cm lever with a wooden button (3.5 cm in diameter) on the top, attached to the right ear, allowed for the ears to be pulled up from behind the head in a circular motion to the side of the head.

Professionally produced 60 s video segments, one for each stimulus, were made for the study. The video used cuts to focus attention on the target actions. At the beginning of each videotape, toddlers saw the head and torso of the male experimenter but the stimuli were not visible. The experimenter began the video demonstration by saying “Look at this.” Next, toddlers saw a close-up of the experimenter’s hands as he modeled the target actions for one repetition (Barr & Hayne, 1999; McCall et al., 1977). Next, they saw the head and torso of the male experimenter again. The demonstration alternated between close-ups of the target actions and the head and torso of the male experimenter. The experimenter on the video demonstrated the actions with one set of stimuli six times and then demonstrated different actions with the other set of stimuli six times. The actions were demonstrated in exactly the same manner as for toddlers in the live 3x condition. Between the presentation of one set of stimuli and the other there was a 1s fade out to black. For the video 6x voice-over condition a female voice-over was added to the 4 video segments. The voice-over was inserted during the demonstration of the target actions and was identical to the script used by parents in the parent labeling conditions.

Procedure

During the initial visit, the purpose of the study and details of the procedure were explained to the caregiver and informed consent was obtained. All toddlers were tested in their homes at a time of day that the caregiver identified as an alert/play period. At the beginning of each session, the experimenter interacted with the toddler for approximately 5 minutes or until a smile was elicited. Parents also reported language production via the MacArthur Communication Development Inventory (MCDI; Fenson et al., 1994). Parents were also asked to estimate their typical daily household television use.

Demonstration session

The live and video demonstration conditions were equated as much as possible. For both groups, an experimenter demonstrated three specific actions with two different sets of stimuli, one rattle and one animal. For each condition, the number of demonstrations of the target actions is delineated as 3x or 6x to refer to the fact that they were shown the target actions 3 or 6 times respectively in a single session. The experimenter demonstrated the target actions for the first set of stimuli and then she demonstrated the target actions for the second set of stimuli. The target actions were always demonstrated in the order shown in Table 2. In order to later accurately measure looking time during the demonstration, the toddler’s face was videotaped.

For the live 3x parent label condition the total demonstration time for each set of stimuli was on average 40 s (M = 42.4 s, SD = 8.1). The variation in the live demonstration times were due to differences in time to disassemble the stimuli and occasional interruptions in the household such as a phone ringing. For toddlers in the live 3x parent label condition, the experimenter sat opposite the toddler and the caregiver on the floor, such that the stimuli were out of the toddler’s reach. The parent sat behind the toddler.

Toddlers in the video 6x condition watched as a different experimenter performed the same three specific actions with the sets of stimuli, however, each set of actions was demonstrated six times on pre-recorded videotape and the total demonstration for each set of stimuli was 60 to 63 s. The experimental setup for toddlers in the video condition was identical to that used in prior studies of imitation from television (Barr & Hayne, 1999; Barr, et al., 2007; Hayne et al., 2003). All toddlers were seated on the caregiver’s lap during the demonstration approximately 80 cm from the family’s most used television set such that the screen was at the toddler’s eye level but was out of reach. The participants’ home television screens ranged from 33 to 127 cm with an average screen size of 64.83 cm (SD = 15.4) and all were color. During the video demonstration, the experimenter remained in the room.

During the live and video demonstrations, the target actions were not verbally described by the experimenter but to maintain the toddlers’ attention on the test stimuli, the experimenter used phrases like, “Isn’t this fun?” or “One more time,” speaking in a manner characteristic of “motherese” in between demonstrations of the target actions.

The unique labels used by Herbert and Hayne (2000), “meewa” and “thornby”, were also used in the present study for each set of stimuli. Caregivers in the live 3x parent label and video 6x parent label conditions read a script using the unique labels, and for the video 6x voice-over condition the labels were prerecorded onto the DVD/videotape with a female voice. The female who provided the voice-over did not attend the visits. Caregivers in the video 6x parent no label condition read the same script but the word “something” instead of the novel label. Each time the target actions were demonstrated the following script was used. Just before the demonstration began, “Look, he’s going to make a thornby.” As the experimenter began putting the object together, “What’s he doing? He’s making a thornby.” Just after he put the object together, “Look. He’s made a thornby.” For the other set of stimuli the word “meewa” was used. Parents complied with the instructions to read and on average said the word “Thornby” or “Meewa” 8.2 times (SD =.95) during the live demonstration and 13.9 times (SD = 4.0) during the video demonstration. The stimuli, the order of the stimuli, and the labels that were used with each set of stimuli were counterbalanced across participants.

Test Session

Toddlers were tested after a 24-hour delay. Using a predetermined script for each set of stimuli, the experimenters said, “yesterday you saw how to make a meewa (or thornby), you can use these things to make a meewa (thornby)”. The experimenters asked the toddlers to make a “meewa” with one set of stimuli and a “thornby” with the other. For the no label condition, the experimenter used the word “something” for both sets of stimuli instead of saying meewa and thornby. Toddlers were tested with the rattle or animal that they had not seen during the demonstration. They were given 60 s per stimulus set to reproduce the target actions. To assess the spontaneous production of the target actions in the absence of the demonstration of the target actions, the baseline control condition was not shown the test stimuli prior to the test. For the baseline control condition this was the first and only session.

Coding and reliability

Demonstration session

Looking time was coded from videotaped sessions using a computer timer. The coder pressed a key to mark the beginning and end of the demonstration and pressed another key when toddlers looked at or away from the demonstration. The duration of the looks and overall percent looking were subsequently calculated (e.g., Anderson & Levin, 1976). Data were not recorded for 1 toddler due to technical errors. Based on 52% of the sessions, a Pearson product-moment correlation on percent looking time yielded an interobserver reliability coefficient of.92.

Test session

An observer noted the total number of target actions that each toddler imitated for each rattle and animal stimulus set during the videotaped test session (range 0–3 per task). Interobserver reliability was 94.5% (Kappa =.89) for the total scores, based on 55% of the test sessions. When the two raters differed, the primary rater’s score was assigned.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Language development in this sample was typical; on average the percentile rank on the MCDI was 47.6 (SD = 32.9). We also coded the number of words that toddlers knew to describe the tasks (carrot, banana, rabbit, monkey, ball, rattle, stick), and parents reported that toddlers produced on average 3.9 of the 7 words (SD = 1.7) suggesting that the stimuli included items that toddlers were familiar with. Based on reports by 87% of parents who completed a 24 hr household media diary, television was used on average for 2 hrs and 7 min per day (SD = 1 hrs 42 mins) and consistent with prior findings, toddlers were exposed to an average of 1 hr and 10 min per day (SD = 1 hr 6 mins), 83% of which was child-directed programming.

Demonstration session

For the experimental conditions, looking time during the demonstration, looking time during the target actions, frequency of points, frequency of smiles, and frequency of vocalizations were coded. The data are shown in Table 3 as a function of condition. A MANOVA was calculated on percent looking during target actions, looks away, pointing, smiling, and vocalizations as a function of group assignment. Behaviors were averaged across stimuli. The live condition data were weighted by session duration. There was only one significant main effect, percent looking during target actions, F(3,43) = 3.55, p <.03. Post-hoc Student Newman Kuhls tests (SNK, p <.05) indicated that the parent label 6x video condition had significantly lower looking time to the screen during the presentation of the target actions than the parent label 3x live, parent no label 6x video, or the voice-over 6x video conditions that did not differ from one another. The amount of vocalizing, pointing and smiling did not differ as function of group assignment.

Table 3.

Behavior (± SE) during the demonstration session as a function of group assignment

| Parent 3x live label | Parent 6x video | Voiceover 6x | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| label | no label | |||

| % Looking | 95 (2) | 88 (2)* | 95 (2) | 97 (1) |

| Looks away | .75 (.23) | 2.54 (.56) | 1.14 (.45) | .79 (.30) |

| Points | .30 (.12) | .08 (.08) | .14 (.07) | .25 (.18) |

| Vocalizations | .74 (.20) | 1.70 (.53) | 2.39 (.64) | .25 (.18) |

| Smiles | .75 (.19) | .95 (.29) | .70 (.29) | .37 (.11) |

To assess whether looking patterns were related to imitation score, we conducted a linear regression and entered the variable percent looking during target actions on imitation score during the test. Percent looking during the demonstration did not predict the number of target actions produced during the test, F(1,45) = < 1.

Test session

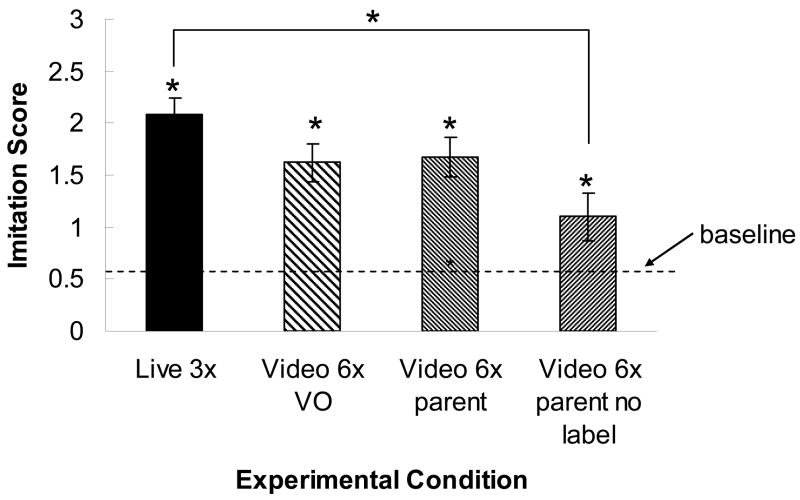

A preliminary analysis was conducted as a function of stimuli, order of presentation, and gender. There were no main effects or interactions as a function of order or gender. The data were therefore collapsed across these variables for further analysis. There was a main effect of stimuli, F(3,55) = 3.43, p <.03. Post-hoc SNK tests indicated that toddlers imitated significantly more actions using the rattle stimulus sets than the animal stimulus sets but there was no difference as a function of type of rattle or type of animal. Given that all infants were tested with both stimuli, the mean number of target actions was averaged across the two stimuli. A one-way ANOVA yielded a significant main effect of condition on the average number of behaviors reproduced during the test session, F(4, 56) = 11.03, p <.001. The post-hoc analysis of this effect addressed two main questions. First, did the experimental conditions perform above baseline? Second, did the video conditions continue to show a video deficit relative to the live demonstration condition? To answer these questions Dunnett’s post-hoc t-tests (p <.05) were used to compare each group to the baseline group. We also compared each group to the live 3x parent label group. As shown in Figure 1, all of the experimental groups performed significantly above baseline. Furthermore, the video 6x no label group performed significantly worse than the live 3x parent group. The video 6x parent label and the video 6x voice-over label groups did not differ from the live 3x parent group. That is, repetition alone improves performance above baseline but does not remove the video deficit. Doubling the number of repetitions on video and providing verbal labels, either from the parent or voice-over, removes the video deficit effect.

Figure 1.

The mean imitation score as a function of experimental group. The baseline control group performance is indicated by a dashed line. Group performance that was significantly above baseline is indicated by an asterisk. A difference in performance between the video 6x parent no label group and live 3x parent label group is indicated by a line above and connecting the two groups.

Discussion

The findings replicate and extend those of Herbert and Hayne (2000) and Barr and colleagues (2007). Extending Herbert and Hayne (2000), the present study examined how imitation performance would be affected when demonstration was presented on television rather than live. Extending Barr and colleagues, the present study examined the effect of repetition on generalization performance. Previously, Hayne and Herbert (2000) demonstrated that toddlers generalized when experimenters provided novel labels during the demonstration but did not perform above baseline when no labels were provided. Barr and colleagues (2007) found that repetition of the target actions removed the video deficit when infants were tested with the same stimuli at test as had been presented during the televised demonstration. Replicating Hayne and Herbert (2000), in the present study when parents, rather than experimenters, provided verbal labels during the live demonstration toddlers generalized to the new stimuli and imitated significantly above baseline. The video no label group performed significantly above baseline but their performance was significantly worse than that of the live parent label group. That is, comparing across experiments it could be inferred that repetition increased group performance above baseline but did not remove the video deficit. The present findings suggest the repetition not only ameliorates the video deficit effect when the test stimuli are the same as the demonstration but enhances learning when the test stimuli are novel. When parents or a video voice-over provided the verbal label during the video demonstration, toddlers generalized to the new stimuli and imitated significantly above baseline and no longer exhibited a video deficit. Toddlers were able to use novel verbal labels provided by their parents or a voice-over to solve a difficult imitation problem from television. Taken together, the present study suggests that both repetition of information and provision of unique verbal labels led to increased generalization performance following a video demonstration.

Both parent labeling and voice-over were effective in enhancing imitation of the target actions on a novel stimulus but behavior during the demonstration differed across experimental conditions. When parents provided verbal labels during the video demonstration, looking time was significantly lower than for other experimental groups. The video parent label condition involved a complex joint visual attention situation when new language information was provided by the parent and new visual information was provided on the screen, much like a typical book reading situation. Even though looking time decreased, imitation performance did not, demonstrating that toddlers were able to integrate the labels provided by parents with the 2D information presented on the screen. In contrast, looking time remained high for the video no label group when no new language was provided by parents. Given that looking time is sometimes a reflection of endogenous attention and encoding of information (Kannass & Colombo, 2007) one possible interpretation of the data is that the parent-label group actually facilitated learning relative to the voice-over condition.

Analogous to the book reading situation where parents act as a scaffold to promote literacy, parents can enhance learning from television as well. Social contingency has been found to increase toddlers’ learning from television (e.g., Troseth, Saylor, & Archer, 2006). Troseth and colleagues assigned 2 year olds to a contingent or non-contingent close-circuit interaction. Toddlers in a contingent condition interacted with an experimenter across a close-circuit television screen for 5 minutes. At the end of the interaction, the experimenter told children where they could find the hidden toy in the room next door and asked them to go and find it. Toddlers in the non-contingent control group watched pre-taped social interactions that were not contingent upon their behavior. The 2-year-olds who received contingent feedback were significantly more likely to find the hidden toy than were the toddlers who had seen a pre-taped non-contingent interaction. Troseth et al. (2006) concluded that that during the second year of life, toddlers increasingly expect to obtain relevant information from a contingent social partner. Lack of contingency during the televised demonstration disrupts the transfer of information from television to real-life activities. The present study extends the findings of Troseth and her colleagues to suggest that learning can be scaffolded via parental mediation or via voice-over presentations. It is somewhat surprising that the voice-over condition produced similar results given that there was no social contingency. It is possible that fast mapping of the novel labels by toddlers when target actions were clearly displayed allowed such generalization to occur (see also Krcmar et al., 2007).

These findings have implications for future programming aimed at toddlers of this age. Repetition, increased parental involvement, and voice-overs may influence the success of toddlers’ retention of information from television and facilitate their vocabulary development. Voice-over may be particularly effective beginning around 2 years of age. It is less likely that providing verbal labels via voice-over would be as effective for children under 2 given Herbert and Hayne’s (2000) original negative findings with unique labels during a live demonstration. Krcmar and colleagues (2007) also found that infants 22 months and older were able to learn words from a voice-over videoclip but those under 22 months were not. Additional research is required to investigate all three techniques at different ages to assess when these strategies would be most effective. Furthermore, it would be important to assess whether adding letters and numbers act as a distracter for toddlers in this age range. Krcmar and colleagues (2007) found that presentation of simple adult word naming was easier to learn than word learning embedded in a more complex video display. These authors suggested that it may be difficult for infants to know where to focus their attention on the screen. Furthermore, symbol learning in general is highly complex and deficits are often seen until the third year of life (e.g. Troseth & Deloache, 1998).

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our thanks to the families that have participated in our study. Thanks to Beverly Good, Ann-Marie Faria, Kara Garrity, and Katherine Salerno for their help in the data collection and coding. The research was funded by an NICHD grant to Rachel Barr (# HD043047-01) and by NSF grant to Children’s Digital Media Center (# NSF 0126014) and the Georgetown University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics COPE. Media Education. Pediatrics. 1999;104:341–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DR, Pempek T. Television and very young children. American Behavioral Scientist. 2005;48:505–522. [Google Scholar]

- Barnat SB, Klein PJ, Meltzoff AN. Deferred imitation across changes in context and object: Memory and generalization in 14-month-olds. Infant Behavior & Development. 1996;19:241–252. doi: 10.1016/S0163-6383(96)90023-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr R. Attention to and learning from media during infancy and early childhood. In: Calvert SL, Wilson BJ, editors. Blackwell Handbook of Child Development and the Media. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Barr R, Hayne H. Developmental changes in imitation from television during infancy. Child Development. 1999;70:1067–1081. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr R, Muentener P, Garcia A, Chavez V, Fujimoto M. The effect of repetition on imitation from television during infancy. Developmental Psychobiology. 2007;49 doi: 10.1002/dev.20208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr R, Zack E, Garcia A, Muentener P. Attention to infant-directed programming: Influence of prior exposure and parent-infant interactions. Infancy. 2008;13:30–56. [Google Scholar]

- Carver LJ, Meltzoff AN, Dawson G. Event-related potential (ERP) indices of infants’ recognition of familiar and unfamiliar objects in two and three dimensions. Developmental Science. 2006;9:51–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00463.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deocampo JA, Hudson JA. When seeing is not believing: Two-year-olds’ use of video representations to find a hidden toy. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2005;6:229–258. [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick S, Bates E, Thal D, Pethick SJ, Tomasello M, Mervis CB, Stiles J. Variability in Early Communicative Development. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59(5) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison M, Christakis DA. A teacher in the living room: Educational media for babies, toddlers, and preschoolers. Menlo Park, CA: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna E, Meltzoff AN. Peer imitation by toddlers in laboratory, home, and day-care contexts: Implications for social learning and memory. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:702–710. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.29.4.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayne H, Boniface J, Barr R. The development of declarative memory in human infants: Age-related changes in deferred imitation. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2000;114:77–83. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayne H, Herbert J, Simcock G. Imitation from television by 24- and 30-month-olds. Developmental Science. 2003;6:254–261. [Google Scholar]

- Hayne H, MacDonald S, Barr R. Developmental changes in the specificity of memory over the second year of life. Infant Behavior & Development. 1997;20:233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert J, Hayne H. Memory retrieval by 18–30-month-olds: Age-related changes in representational flexibility. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:473–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JA, Sheffield EG. The role of reminders in young children’s memory development. In: Tamis-LeMonda CS, Balter L, editors. Child psychology: A handbook of contemporary issues. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 1999. pp. 193–214. [Google Scholar]

- Kannass KN, Colombo J. The effects of continuous and intermittent distractors on cognitive performance and attention in preschoolers. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2007;8:63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Krcmar M, Grela B, Lin K. Can Toddlers Learn Vocabulary from Television? An Experimental Approach. Media Psychology. 2007;10:41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl PK, Tsao F, Liu H. Foreign language experience in infancy: Effects of short term exposure and interaction on phonetic learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100:9096–9101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1532872100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall RB, Parke RD, Kavanaugh RD. Imitation of live and televised models by children one to three years of age. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1977;42(5) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumme DL, Fernald A. The infant as onlooker: learning from emotional reactions observed in a television scenario. Child Development. 2003;74:221–237. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao K, Treas J. The 1989 Socioeconomic Index of Occupations: Construction from the 1989 Occupational Prestige Scores (No. 74) Chicago, IL: NORC; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rideout V, Hamel E. The media family: Electronic media in the lives of infants, toddlers, preschoolers and their parents. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rideout V, Vandewater E, Wartella E. Zero to six: Electronic media in the lives of infants, toddlers, and preschoolers. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt KL, Anderson DR. Television and reality: Toddlers’ use of visual information from video to guide behavior. Media Psychology. 2002;4:51–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sell MA, Ray GE, Lovelace L. Preschool children’s comprehension of a Sesame Street video tape: The effects of repeated viewing and previewing instructions. Educational Technology Research and Development. 1995;43:49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Simcock G, Dooley M. Generalization of learning from picture books to novel test conditions by 18- and 24-month-old children. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1568–1578. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suddendorf T. Early representational insight: twenty-four-month-olds can use a photo to find an object in the world. Child Development. 2003;74:896–904. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troseth GL. TV guide: two-year-old children learn to use video as a source of information. Developmental psychology. 2003;39(1):140–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troseth GL, DeLoache JS. The medium can obscure the message: young children’s understanding of video. Child Development. 1998;69:950–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troseth GL, Saylor MM, Archer AH. Young children’s use of video as a source of socially relevant information. Child Development. 2006;77:786–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins BA, Calvert SL, Huston-Stein A, Wright JC. Children’s recall of television material: Effects of presentation mode and adult labeling. Developmental Psychology. 1980;16:672–674. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman F, Christakis D, Meltzoff AN. Television and DVD/video viewing by children 2 years and younger. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.5.473. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]