Abstract

Sexual pressure among young urban women represents adherence to gender stereotypical expectations to engage in sex. Revision of the original 5-factor Sexual Pressure Scale was undertaken in two studies to improve reliabilities in two of the five factors. In Study 1 the reliability of the Sexual Pressure Scale for Women-Revised (SPSW-R) was tested, and principal components analysis was performed in a sample of 325 young, urban women. A parsimonious 18-item, 4-factor model explained 61% of the variance. In Study 2 the theory underlying sexual pressure was supported by confirmatory factor analysis using structural equation modeling in a sample of 181 women. Reliabilities of the SPSW-R total and subscales were very satisfactory, suggesting it may be used in intervention research.

Keywords: Sexual pressure, women, gender, sex scripts, HIV risk, SEM, ACASI

Sexual pressure represents a woman’s adherence to gender stereotypical expectations about engaging in sex and concern about adverse consequences ranging from losing the relationship to coercive force or threats by a male partner if these expectations are not met (Jones, 2006a, 2006b). In community samples of predominately African American and Latina young urban women, findings indicated that the concern about losing love, trust, or the relationship if one refused to engage in sex was far more pervasive than the experience of or fear of a male partner’s coercive threats or violence (Jones, 2004; Jones, 2006a; Sionean et al., 2002). The need to discriminate the broader concept of sexual pressure from the narrower concept of sexual coercion that involves threats or the use of force prompted the development of the Sexual Pressure Scale (SPS), a valid and reliable measure of gender stereotypical expectations to engage in sex (Jones, 2006a). Because alpha reliabilities of two of the five SPS factors fell below the recommended minimum alpha of .70 for new scales (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994), representative items were added to improve the subscale reliabilities. This paper reports two studies that were conducted to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Sexual Pressure Scale for Women-Revised (SPSW-R). Study 1 was designed to test the reliability of the SPSW-R and to determine the factor structure using principal components analysis. The purpose of Study 2, conducted with a separate sample, was to assess support for the theory underlying sexual pressure with a confirmatory analysis using structural equation modeling.

Background

Sexual pressure is of particular importance in regard to sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in women. Over 80% of women with HIV have been infected by unprotected sex with an infected male partner (aCenters for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]; 2007a). The CDC has described HIV/AIDS as a health crisis for African Americans (CDC, 2007b).

A valid assessment of sexual pressure could suggest the extent to which stereotypical gender expectations structure women’s patterns of thinking and behavior in ways that influence partner selection and limit women’s autonomy in sexual choices. For example, women with stereotypical gender expectations may be less assertive in communicating their desire to reduce risk and more likely to engage in sex with men whom they perceive to engage in HIV risk behaviors than women who disagree with these views (Morokoff et al. 1997; Quina, Harlow, Morokoff & Burkholder, 2000). Sexual assertiveness is considered to be an attribute of healthy sexual autonomy in women (Morokoff et al.). However, it could also be an expression of pressure to meet an expectation to engage in sex (Jones, 2006a; Jones & Oliver, 2007). Unprotected sex is part of a romance script (Gavey & McPhillips, 1999) that follows the logic to “do whatever it takes” to hold onto a man (Jones & Oliver), because the perceived benefits of unprotected sex appear to be prioritized over reducing risk (Albarracin et al., 2000; Gerrard, Gibbons, & Bushman, 1996).

Sexual Pressure: Influenced by a Sex Script

Stereotypical expectations to engage in sex occur in a broader structural context of a gender hierarchy that affects an individual’s expectations and sexual behavior (Anderson, 2005; Eagley & Wood, 2003; Travis & White, 2000). The environment is saturated with role models invoking women as sex objects in visual media and music (Ward, Hansbrough, & Walker, 2005).

Sexual pressure experienced in this context is influenced to a large extent by one’s sex script that defines these expectations to engage in sex. Scripts contain impressions about the sequence of events that occur in well known situations (Singer & Salovy, 1991). Sex scripts guide an individual’s or dyad’s expectations about appropriate sexual behavior (Simon & Gagnon, 1986). These scripts are dynamic, changing with social environments, with the individual’s evolving view of her own sexuality, and the closeness with which the dyad follows the script (Simon & Gagnon, 1986). Sex scripts have been used as a framework to understand sexual behavior in various populations (Emmers-Sommer & Allen, 2005; Hynie, Lydon, Cote, & Weiner, 1998; Jones, 2006a; Krahe, 2000; Metts & Spitzberg, 1996; Parsons et al., 2004).

Jones and Oliver (2007) conducted a series of focus groups with 43 urban African American, Afro Caribbean, and women of Puerto Rican descent in order to more fully understand reasons women engaged in unprotected sex with men they did not trust, whether women experienced sexual pressure, and if so, how sexual pressure would be described. Strauss and Corbin’s (1990) method of open and axial coding was followed. Sex script theory and the theory of power as knowing participation in change (Barrett, 1998) guided the interpretation of the content analysis. Descriptions of two sex scripts, a lower and a higher power sex script emerged (Jones & Oliver).

Sexual Pressure Conceptualized as a Lower Power Sex Script

According to Barrett (1998), power involves being aware of what one is choosing to do, having a tendency to explore all available choices, feeling freedom to act intentionally, and being involved in creating change. A key attribute of sexual pressure is a limited awareness of one’s choices, as this awareness is bound by a socially available, yet narrow, stereotypical vision of women and sexual expression. For example, findings indicate women with higher sexual pressure are also more likely to partner with a man who had sex with other women, or who engages in other risk behaviors (Jones, 2006a). A woman’s awareness of herself is central to whether she feels worthy of focusing on her own well being.

In a lower power sex script, women adhere to stereotypical expectations to engage in sex, believing that sex is necessary to hold onto a relationship, and although they perceive their partner to engage in a risk behavior, continue to engage in unprotected sex. Results of content analysis indicated the importance of “doing what it takes to hold onto a man.” Higher power sex scripts involve expanding awareness of one’s own value as a woman, the recognition that there are choices in partners and sexual behaviors, and the determination to pursue these choices (Jones, 2006b, Jones & Oliver, 2007). In a higher power sex script women practice various strategies to encourage their partners to use condoms or they abstain from sex.

These qualitative findings provide an in depth understanding of earlier quantitative findings that the distribution of sexual pressure and sex risk scores were positively skewed (Jones, 2004; Jones, 2006a), meaning most women did not hold stereotypical views about sex and did not engage in sex risk behaviors (i.e. had higher power sex scripts). Both lower and higher power sex scripts are present in young urban women.

Development of the Original Sexual Pressure Scale

The original Sexual Pressure Scale (SPS) was developed to measure sexual pressure in young urban women (Jones, 2006a). A convenience sample of 306 women, aged 18 to 29, was recruited from public housing developments, a public clinic that treats people with sexually transmitted infections (STI), a Women, Infant, and Children nutrition center, and dormitories at an urban public university in the Northeastern United States. Data were collected using audio computer assisted self-interview (ACASI) on laptop computers. With ACASI, the participant can hear the interview items in privacy over a headset, while reading the text on the screen. In order to participate, previous computer experience was not required, and the data were anonymous (Jones, 2003).

In the original SPS, exploratory principal components analysis with varimax rotation yielded 19 items in five factors. The five factors explained 62% of the variance in sexual pressure. Factor 1 (4 items), Condom Fear, reflected fear that the partner might say no, would leave, or become violent if asked to use a condom; Factor 2 (3 items), Sexual Coercion, reflected the experience of threats, choking, hitting, kicking, or pulling hair by the male partner if sex was not desired by the woman; Factor 3 (4 items), Women’s Sex Role, reflected a woman’s expectation that it is her responsibility to satisfy her male partner and that sex will provide evidence that she is the best partner for him; Factor 4 (5 items), Men Expect Sex, reflected the expectation that a male partner’s relationship priorities are to be with a woman for her body and to have sex; and Factor 5 (3 items), Show Trust, reflected the expectation that unprotected sex is proof of trust and relationship commitment.

Divergent validity was supported by negative relationships of the SPS factors with dyadic trust. Given that dyadic trust is belief in the partner’s benevolence and honesty (Larzelere & Huston, 1980), the moderately negative correlation between the SPS factor Show Trust and dyadic trust suggested that women’s expectation to engage in unprotected sex as a way to communicate trust and relationship closeness is a dimension of sexual pressure that can be discriminated from trust. The more women felt pressure to show trust by engaging in unprotected sex, the less they trusted their partner, meaning the less they trusted his concern for the welfare of the relationship. This interpretation was further supported by positive relations of the Show Trust factor with the more coercive forms of sexual pressure: the SPS Condom Fear factor, and the Sexual Experiences Survey (SES) classifications of sexual victimization that measure unwanted sexual contact (Koss & Gidycz, 1985). Convergent validity of the SPS was supported by a positive correlation of the SPS with the SES and with sex risk behavior.

The SPS alpha reliability was .81; factor reliabilities ranged from .63 to .82 (Jones, 2006a). Two of the five factors, Men Expect Sex (α = .63) and Show Trust (α = .67) failed to meet the recommended minimum alpha of .70 for new scales (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Improvement in reliability and validity of these factored subscales was undertaken in Study 1 reported below.

In addition to conducting exploratory factor analysis of the revised Sexual Pressure Scale, the following hypotheses were tested in Study 1 to assess construct validity:

Sexual pressure is positively related to sexual victimization.

Sexual pressure is positively related to HIV sexual risk behavior.

Sexual pressure is negatively related to dyadic trust.

Because sexual pressure is conceptualized as a component of a lower power sex script, it was hypothesized that sexual pressure is negatively related to sexual relationship power.

Because a higher score on the sex script video response is an indicator of a lower power sex script, higher sexual pressure is positively related to sex script video response.

Study 1

Method

The purpose of Study 1 was to evaluate the reliability of the SPSW-R and to assess factor structure after the addition of eight new items. Approval to conduct the Women to Women Study of Relationships with Male Partners study was obtained from the University Institutional Review Board.

The additional items for the two SPSW-R factors (Men Expect Sex and Show Trust) were generated from the aforementioned focus groups that were held as part of a larger study by the first author, to further understand sexual pressure, sex scripts, and power in relation to HIV sexual risk behavior (Jones & Oliver, 2007). The series of seven focus groups were held with 43 young, urban women at a job training center, an after school program, a childcare center, and three public housing developments in two adjacent cities in the urban Northeast. A purposive sampling strategy (Miles & Huberman, 1994) was used to assure representation of women in the age range of 18 to 25, and who were in a sexual relationship with a male primary or non-primary partner during the past 3 months. The members of six focus groups were predominately African American; and one group consisted of women of Puerto Rican descent. On the basis of content analysis of the focus group data, a total of 8 new items were developed and added to the original 19-item SPS to be evaluated in Study 1. The new items were based on the open coding of the raw data. Details of the focus groups and content analysis are discussed elsewhere (Jones & Oliver).

Sample

The sample was 325 urban women, aged 18 to 29 who had been in a relationship with a male partner in the past 3 months. The sample size was based on a 27-item scale with at least 10 cases per item (Tabachnik & Fidell, 2001). The sample was recruited from a storefront office in a downtown urban district, a Student Center at a public 4-year university, a daycare center, an urban 2-year community college, and a public clinic that treats people with STIs in two adjacent cities in the urban Northeast. Participants were recruited by the principal investigator (PI) and research assistants (RAs) who were culture, age, and gender representative of the target sample. The mean age of the women was 21.5 (SD = 4.1) with a median age of 20. The majority of the sample was African American and Latina (Table 1). The majority of women had no children and worked either part-time or full-time outside of the home. About half of the women had completed some college and less than one-third received public assistance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of Sample in Study 1 (N = 325) and Study 2 (N =181)

| Description | Study 1 | Study 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Education | ||||

| < High School | 58 | 17.8 | 42 | 23.2 |

| High School | 108 | 33.2 | 74 | 40.9 |

| Some College | 146 | 45.0 | 59 | 32.6 |

| ≥ 4 Years of College | 13 | 4.0 | 6 | 3.3 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| African American | 182 | 56.0 | 156 | 86.2 |

| Latina | 50 | 15.0 | 7 | 3.9 |

| Non-Spanish Speaking Caribbean | 32 | 10.0 | 7 | 3.9 |

| White | 16 | 5.0 | 2 | 1.0 |

| Other (African, Asian, Middle Eastern) | 45 | 14.0 | 9 | 5.0 |

| Children | ||||

| None | 203 | 62.5 | 75 | 41.5 |

| One | 69 | 21.2 | 65 | 35.9 |

| Two or more | 53 | 16.3 | 41 | 22.6 |

| Employment outside of the home | ||||

| None | 54 | 16.6 | 72 | 39.8 |

| ≤ 20 hours per week (part-time) | 164 | 50.4 | 36 | 19.9 |

| > 20 yours per week | 107 | 33.0 | 73 | 40.3 |

| Received Public Assistance | 94 | 28.9 | 75 | 41.4 |

| Drugs used before or during sex | ||||

| None | 265 | 81.6 | 112 | 61.9 |

| Marijuana | 50 | 15.4 | 65 | 35.9 |

| Other (Cocaine, Ecstacy, Speed) | 10 | 3.0 | 4 | 2.2 |

| Used alcohol before or during sex | ||||

| Never | 178 | 54.8 | 84 | 46.5 |

| Sometimes | 110 | 33.8 | 77 | 42.5 |

| Most or all the time | 37 | 11.4 | 20 | 11.0 |

| Condoms used during sex in past year | ||||

| Never | 89 | 27.4 | 51 | 29.8 |

| Sometimes | 70 | 21.5 | 37 | 20.4 |

| Most of the time | 71 | 21.8 | 41 | 22.7 |

| Always | 95 | 29.2 | 48 | 27.1 |

| Uses birth control during sex (condoms, other) | 171 | 52.6 | 85 | 47.0 |

| Believed that condoms helped reduce the risk of HIV/AIDS | 273 | 84.0 | 154 | 85.1 |

Procedures

Recruitment flyers describing the “Women’s Project” were posted or distributed at the study sites. A private room was reserved for study-related activities at each site. During the interviews, the PI or RA provided child-care, as needed. Interviews were conducted using ACASI on portable tablet personal computers (PCs); data were entered by tapping on the touch screen with a pen-like stylus. The touch screen was chosen as an intuitive user interface. The data were directly entered into the database. A “Statement to the Participant” that included all the elements of informed consent, was played over the headset connected to the tablet PC and viewed on the monitor. To preserve anonymity, participants pressed the #1 key to indicate consent. The ACASI is interactive, so that participants see only questions relevant to their previous responses (i.e. partner type or engagement in sex). The data were automatically uploaded via a secured wireless network to a remote server. On completion, each participant was compensated $15 and provided a pamphlet that described ways to reduce HIV risk. The RA reviewed the pamphlet with the participant.

Instruments

The Sexual Experiences Scale (SES; Koss & Gidycz, 1985; Koss & Oros, 1982) measures sexual victimization. The SES uses a dichotomous response format of Yes or No to 10 items. Participants are classified according to the most severe self-reported sexual victimization. The classifications are (a) no sexual aggression, (b) sexual contact, (c) sexual coercion, (d) attempted rape, and (e) rape. The higher the classification, the higher the sexual victimization. The reported internal reliability for women was .74 and test-retest agreement after 1 week was 93% (Koss & Gidycz). In this study the Cronbach’s α was .85.

Sex Risk Behavior is the frequency of unprotected vaginal, oral, and anal sex with a perceived high risk partner during the previous 3 months. Three months is considered an acceptable period of recall (Schroder, Carey, & Vanable, 2003). At the onset of the interview the RA reviewed today’s date and that of 3 months ago in order to anchor the dates of the reporting period. Participants were asked the number of times they had each type of sex, and of these times, how many times a condom was used. (Protected acts were subtracted from total acts for the frequency of unprotected sex). The perception of partner risk consists of 3 items: “How likely is it that your partner had sex with another woman?” “How likely is it that your partner had sex with men?” and “How likely is it that your partner injected drugs in the past 3 months?” There is a 4-point response metric, from definitely do not feel=0, to definitely feel=3 (a range of 0 to 9). The sex risk score is the product of the frequency of unprotected sex and the perception of partner risk. The rationale for taking the product to measure sex risk behavior is that the lowest level of sex risk occurs when a person abstains from sex or perceives that her partner engages in no risky behavior. Sex risk is weighted by taking the product, so that a person who engages in unprotected sex with a partner with two risk factors (for example, sex with other women and sex with men) is considered to have twice the sex risk as someone with a partner with one risk factor. Similarly, someone who scores twice as high on unprotected sex is considered to have twice the risk given the same level of partner risk behaviors.

The Dyadic Trust Scale (Larzelere & Huston, 1980) measures trust in a close relationship. It is an 8-item scale that uses a 7-point response format ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Each woman is instructed to complete the Scale for either the partner she was with the longest or her most important partner during the past 3 months. The total score ranges from 8 to 56, a higher score indicating higher trust. Larzelere and Huston demonstrated convergent validity by significant associations of dyadic trust with love and intimacy of self-disclosure. Discriminant validity was demonstrated by low correlations with general trust. For the current study, Cronbach’s α was .89.

Sexual Relationship Power Scale (SRPS; Pulerwitz, Gortamker, & DeJong, 2000) is a 20-item scale measuring interpersonal power relations in a male-female main partner relationship. The SRPS is based on gender power inequality expressed as who has more control in the relationship and which partner dominates decision-making. The SRPS has two subscales, Relationship Control and Decision Making Dominance, that are combined for a total score. Women with higher relationship power were five times as likely as women with lower power to report consistent condom use (Pulerwitz, Amaro, De Jong, Gortmaker, & Rudd, 2002). Higher SRPS scores indicate higher relationship power. In a largely Latina sample of women with main partners, Cronbach’s α was .83. In the current study of women with main and non-main partners, Cronbach’s α was .87.

Kayla and Steve Sex Script Video and the Sex Script Video Response (SSVR). In a study by Hynie and Lydon (1995), participants read a fictitious woman’s diary and then responded to items designed to assess a sexual double standard. A similar approach was taken in this study with The Kayla and Steve Sex Script Video and SSVR. This 5-minute video was produced by the first author and is based on content analysis of the aforementioned focus groups. The video concerns a familiar event that may have been personally experienced. Participants respond to items asking what Kayla would do and what her friends would do if faced by the dilemma depicted in the video. Responses indicate whether there is a sex script that promotes unprotected sex. In the video, Kayla has not seen her partner, Steve, in 2 weeks and is anxiously awaiting a call from him. While she is outside she sees Steve talking to a woman whom she believes Steve is now seeing. That afternoon Kayla comes home to hear a message from Steve on her telephone answering machine. Steve is asking if he can come over. The video ends. The participant is asked to conclude what happened in the Kayla and Steve video.

The SSVR is a 12-item instrument developed by the PI to evaluate evidence of a sex script involving unprotected sex. Examples of the first 6 items are: Did Kayla let Steve come over? Did they have sex? Did they use a condom? (Cronbach’s alpha=.84). Six items repeat these questions but instead of focusing on Kayla these items begin with “Would most women you know …” (alpha = .90). Response options are on a 5-point metric, No, Don’t think so, Maybe, Possibly, Yes. The higher the score, the greater the expectation of the need to engage in unprotected sex to hold onto a relationship, indicative of a sex script involving unprotected sex. Cronbach’s α for the total SSVR was .85.

Demographic sheet

The demographic items were used to describe the sample with items such as age, ethnicity, years of formal education, age at first sex, use of drugs or alcohol before or during sex, and knowledge about condom use.

Data Analysis

Data for the studies were entered and analyzed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences Version 13.0. Data files were examined for accuracy of data entry and outliers. Cronbach’s α was used to determine the internal consistency of the total SPSW-R and its factored subscales. Exploratory factor analysis using principal component analysis and orthogonal rotation was undertaken to determine the underlying dimensionality and internal structure of the revised 27-item scale. Criteria used for examining the factor structure included: variables loading on a factor were consistent with the hypothesized latent concept, factor loadings above .50 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994), presence of marker variables that are highly correlated with one and only one factor, and the scree plot that demonstrated discontinuity in the plotted eigenvalues (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). Data from Study 1 revealed skewness of 2.0 or greater for 40.7% of the variables. Therefore exploratory factor analysis was conducted with raw data and for transformed normal scores. Bivariate correlations were performed to assess SPS convergent and divergent validity. In addition, hierarchical multiple regression was performed to assess whether sexual pressure and sex scripts that were significantly bivariately related to sex risk would remain significantly related in a multivariate model.

Results

Descriptive Findings

Most women reported they did not use drugs before or during sex. Of those who used drugs, marijuana was the most frequent substance used (Table 1). Among those who did use condoms, most used them inconsistently despite the report by most that condoms helped reduce the risk of HIV/AIDS.

Sex Script Response

There was evidence of a sex script. Of the 325 participants, 86.8% said Kayla let Steve come over (60% said most women they knew would let him come over). Of the 282 who indicated that Kayla let Steve come over, 75.5 % said Kayla and Steve had sex (55% of most women who would let him come over would have had sex with him), of the 213 who said Kayla and Steve had sex, only 44% said Kayla and Steve may have used condoms (for most women they knew, 52.3%), 65.5% said Kayla continued to have sex with Steve knowing he was still with the other woman. Only half of these (49 %) believed that Kayla and Steve would continue to use condoms. The majority (74.5%) believed that Kayla believes a woman needs to have unprotected sex to hold onto her man.

Construct Validity: Exploratory Factor Analysis

In conducting exploratory factor analysis, a 5-factor structure consistent with the original SPS was examined first. The first and 6 subsequent runs resulted in removal of variables that had high loadings on a secondary factor or were conceptually inconsistent with the primary factor. These analyses resulted in an 18-item, 4-factor model that explained 61% of the variance. Four of the five factors from the original SPS emerged: Factor 1 Show Trust (5 items) means women believe that they need to engage in unprotected sex as a sign of trust and relationship commitment. Factor 2 Women’s Sex Role (5 items) defines the sexual behavior that is expected if women are to find and hold onto a male partner. Factor 3 Men Expect Sex (5 items) is the perception that men view sexual intercourse as a highly important aspect of the relationship. Factor 4 Sex Coercion (3 items) is the perceived threat of reprisal if women do not comply.

Logarithmic transformation of the individual item scores and factor scores did not affect the results of correlations nor internal reliability. According to Norris and Aroian (2004) data transformations are not always needed or advisable when the Cronbach’s α or Pearson product moment correlation is calculated for instruments with skewed item responses. Therefore, it was decided to retain the results from the exploratory factor analysis using principal component and orthogonal rotated analysis with the raw data. The respective factor loadings together with the percentages of explained variance, eigenvalues, and alpha reliabilities for the exploratory factor analysis using raw data are reported in Table 2. Alpha reliability coefficients were .88 for the total SPSW-R and ranged between .76 and .85 for the factors. Polit and Beck (2004) indicate that coefficients in the vicinity of .70 are usually adequate for group-level comparisons.

Table 2.

Sexual Pressure Scale for Women-Revised: Principal Components Analysis with Varimax Rotation for Study 1 (N = 325)

| Variablea | Factor

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Show Trust | Women’s Sex Role | Men Expect Sex | Sex Coercion | |

| I do not ask my partner to use a condom because he may think I had sex with someone | .84 | .15 | .14 | .07 |

| He will think I caught something from someone | .81 | .18 | .20 | .17 |

| He may think I do NOT trust him | .81 | .21 | .18 | .12 |

| I’m afraid he might say NO | .63 | .06 | .08 | .34 |

| After we been doing it raw, I can’t start asking | .57 | .19 | .15 | .20 |

| If my partner wants sex, it’s my responsibility | .17 | .73 | .17 | .01 |

| It’s a woman’s responsibility to satisfy her man | .02 | .72 | .07 | .05 |

| A woman needs to please her man sexually | .18 | .70 | .20 | .02 |

| Sex with my partner shows him that I am the best | .14 | .67 | −.04 | .17 |

| There are plenty of women who are willing to have sex with him. | .26 | .55 | .34 | .06 |

| My partner makes me feel that I should try new ways to have sex | −.03 | .21 | .69 | .04 |

| My partner makes me feel he will cheat if he gets tired of having sex with me | .39 | .15 | .69 | .16 |

| My partner makes me feel like I owe him something and should have sex | .37 | .05 | .66 | .30 |

| My partner would leave me if I did not have sex | .30 | .23 | .63 | .27 |

| I have sex with my partner because I am afraid of losing the things he does for me | .10 | .03 | .55 | .38 |

| My partner has physically hurt me after I told him I would not have sex | .15 | .09 | .19 | .86 |

| My partner has threatened to hurt me after | .27 | .05 | .18 | .81 |

| My partner has yelled or cursed at me after | .24 | .15 | .30 | .69 |

| Percent of explained variance | 18.89 | 14.38 | 14.18 | 13.62 |

| Eigenvalue | 6.62 | 1.89 | 1.44 | 1.04 |

| Alpha reliability coefficient | .85 | .76 | .78 | .83 |

| Mean | 7.64 | 12.12 | 9.22 | 3.71 |

| SD | 4.59 | 5.12 | 4.72 | 1.87 |

Note. Cronbach’s Alpha for the SPS-R was .88.

The items as shown are not complete.

Correlations between the total SPSW-R and its factored subscales ranged between .66 and .83. Inter-correlations between factors were moderate and significant (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlations between the Sexual Pressure Scale for Women-Revised and Factored Subscales for Study 1 (N=325)

| Scale/Subscale | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Total SPS | 1.00 | ||||

| 2. Show Trust | .81 | 1.00 | |||

| 3. Women’s Sex Role | .77 | .44 | 1.00 | ||

| 4. Men Expect Sex | .83 | .55 | .45 | 1.00 | |

| 5. Sex Coercion | .66 | .50 | .29 | .58 | 1.00 |

Note. All correlations significant at p < .001

Construct Validity: Theoretically Related Constructs

The hypothesis that sexual pressure would be positively related to sexual victimization (SES) was supported, r = .45, p <.001. The hypothesis that sexual pressure would be positively related to HIV sexual risk behavior was supported, r = .38, p<.001. Women who scored higher on sexual pressure were more likely to have unprotected sex with a perceived higher risk partner. Each SPSW-R factor correlated significantly with sex risk: Show Trust (r =.36), Women’s Sex Role (r =.26), Men Expect Sex (r =.32), and Sex Coercion (r = .23), all p’s <.001.

The hypothesis that sexual pressure would be negatively related to dyadic trust was supported (r = −.41, p < .01). Significant negative correlations between the Dyadic Trust Scale and the SPSW-R factors were observed (Show Trust, r = −.36, Men Expect Sex, r = −.47, Sex Coercion, r = −.33, p’s < .001, Women’s Sex Role, r = −.14, p =.015). Relationship power (SRPS) was strongly negatively correlated with SPSW-R, r = − 59, p <.001, and with each of the four factors (Show Trust, r = −.47, Women’s Sex Role, r = −.35, Men Expect Sex, r = −.56, Sex Coercion, r = −.49, p’s <.001). As a key element of the sex script, sexual pressure was positively related to the total SSVR (r = .27, p < .001), and each of the SPSW-R factors were related to the sex script (r’s .15 to .24, p’s <.001).

To determine the unique contribution of sexual pressure to sex risk behavior, multivariate analysis with sexual risk as the dependent variable was performed. The only significant demographic variables were use of alcohol before or during sex and work outside the home (age, drug use, knowledge about condom use, and education, were not significantly related to sex risk behavior). Sex Script Video Response was entered in block 2, and sexual pressure was entered last. Together with the two demographic variables, sex script video response and sexual pressure accounted for 20% of the variance in sex risk F (1,320) = 32.61, p < .001. For sexual pressure alone, the Δ R2 was 8% (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analysis Indicating Significant Relationship of Sexual Pressure with Sexual Risk Behavior for Study 1 (N=325)

| Variable | B | SE of B | Beta | R2 | Δ R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment outside the home | −.24 | .11 | −.11 | .02 | .02* |

| Use of alcohol before or during sex | .18 | .06 | .16 | .09 | .07** |

| Sex Script | .01 | .004 | .11 | .12 | .03** |

| Sexual Pressure | .02 | .004 | .31 | .20 | .08*** |

p = .01

p =.001

p < .001

Study 2

The results of Study 1 demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity of the SPSW-R. The next step was to test whether the theorized model depicting sexual pressure was supported by the data. The four constructs within sexual pressure: Show Trust, Women’s Sex Role, Men Expect Sex, and Sex Coercion, were derived from the theoretical framework of sex scripts (Simon & Gagnon, 1986) and power as knowing participation in change (Barrett, 1998). This framework conceptualizes young urban women’s pressure to engage in unprotected sex to be influenced by a sex script that depicts unprotected sex as a means to hold onto a relationship with a male partner (Jones, 2006b, Jones & Oliver, 2007). Integrating Barrett’s theory of power, if women are aware of their value as women, are aware of choices and select their choices with deliberative intention, if they feel free to pursue their choices and are not deterred by obstacles, and if they are involved in creating the necessary changes to make these choices happen, they are unlikely to engage in a lower power sex script.

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted by structural equation modeling to determine if the theory driven concepts would support the construct of sexual pressure. Similar to Study 1, additional construct validity of the SPSW-R was conducted to examine the relations between the SPSW-R and theoretically related variables. It was again hypothesized that sexual pressure is: (a) positively related to HIV sexual risk behavior, (b) negatively related to dyadic trust, (c) negatively related to sexual relationship power, and (d) positively related to sex script video response.

Method

Sample and Design

Study 2 was conducted as part of a larger study by the first author that was funded by the National Library of Medicine (G08 LM008349) to develop and evaluate a decision support system (DSS). The study had a cross-sectional design. The sample of 181 women was between 18 and 29 years of age (M = 22, SD = 3.5). They had been in a relationship with a male partner (main or non-main) in the previous 3 months. The sample size was based on ratio of 10 subjects to 1 item, considered adequate for confirmatory factor analysis (Kline, 2005). Additional characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

Procedure

After Institutional Review Board approval, the data were collected at three different public housing developments and a public recreation center in the urban Northeast. Similar procedures for data collection were used in Study 2 as Study 1. The PI and RAs recruited participants by passing out flyers and explaining the study. However, this time, a recruiter from each public housing development and from the neighborhood of the recreation center assisted with recruitment by giving flyers to women who met the eligibility requirements and directing them to the study team. The recruiters were identified by the public housing staff and the Director at the recreation center based on their knowledge of the community and past leadership in promoting the interests of young adults. Final screening for eligibility was determined by the study team.

Instruments

The instruments were described in Study 1. Sex Risk Behavior was the product of the frequency of unprotected vaginal, oral, and anal sex with a perceived high risk partner during the previous 3 months. The Dyadic Trust Scale (Larzelere & Huston, 1980) was used to measure dyadic trust. In this study Cronbach’s α was .80. The Sexual Relationship Power Scale (SRPS; Pulerwitz et al., 2000) was used to evaluate relationship control and decision making dominance in a dyadic relationship. Cronbach’s α for this study was .84. The Kayla and Steve Sex Script Video was shown. The Sex Script Video Response (SSVR) assessed evidence of a sex script. The 6-items measured what the participant believed Kayla did (alpha = .84). Six items measured what she believes her friends would have done (alpha = .89). Cronbach’s α for the total SSVR was .84. The demographic sheet contained items that were used to describe the sample.

Data Analyses

Confirmatory factor analysis through structural equation modeling (LISREL Version 8.8; Joreskog & Sorbon, 2006) was employed with Study 2 data to test the underlying theory of the SPSW-R construct. Additionally, bivariate correlations were conducted to test the hypothesized relations.

Results

The descriptive findings of ethnicity, education, number of children, employment, and drug and alcohol use are reported in Table 1. Descriptive findings concerning condom use also are found in Table 1.

Construct Validity: Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis using maximum likelihood estimation was used to determine whether the theorized model depicting sexual pressure among women was supported by data. Based on information from a previous study (Jones, 2006a) and results from Study 1, it was hypothesized that 18 indicators from the revised SPSW-R would measure four latent factors: Show Trust (5 indicators), Women’s Sex Role (5 indicators), Men Expect Sex (5 indicators), and Sex Coercion (3 indicators). LISREL 8.8 software was used for the statistical analysis. Model fit was determined by examining the model chi-square, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) which examines residual error, goodness of fit index (GFI) which examines the ratio of the sum of squared discrepancies to the observed variances, and normed fit index (NFI) which indicates the percentage improvement in fit over the null model (Kelloway, 1998; Kline, 2005). A good fit is indicated when the model chi-square test is not significant, RMSEA of ≤ .05 that indicates close approximate fit, and both GFI and NFI values above .90 indicating a good fit to the data (Kelloway; Kline). Because large samples generally result in significant chi-square values, Tabachnick and Fidell (2001) stated that a ratio of the X2 value to the degrees of freedom of < 2, suggests that the model fits the data.

Initial testing of the hypothesized model failed to produce a satisfactory fit of the proposed model to the data, as the RMSEA was greater than .05 and GFI was less than .90. Examination of the modification indexes suggested adding error covariance between two residual variances in the latent factor, Show Trust (between indicator # 1, “I do not ask my partner to use a condom because he may think I had sex with someone else” and indicator # 2), and between three residual variances in the latent factor, Women’s Sex Role (indicator #6, “If my partner wants sex, it’s my responsibility as his woman to have sex with him” and indicator # 7, “It’s a woman’s responsibility to satisfy her man sexually” and between indicator # 7 and #8, “A woman needs to please her man sexually to hold onto him”). This modification led to a satisfactory fit of the model to the data (See Table 5).

Table 5.

Goodness of Fit Statistics for the Sexual Pressure Scale for Women-Revised Model (Study 2)

| 18-Indicator Model

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Fitness Measure | Initial Model | Modified Model |

| Chi-Square Model* | 1.89 | 1.53 |

| Root Mean Square Error of | 0.067 | 0.05 |

| Approximation (RMSEA) | ||

| Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | 0.87 | 0.90 |

| Normed Fit Index (NFI) | 0.90 | 0.92 |

Chi-Square Model Value represents the ratio between X 2 and df.

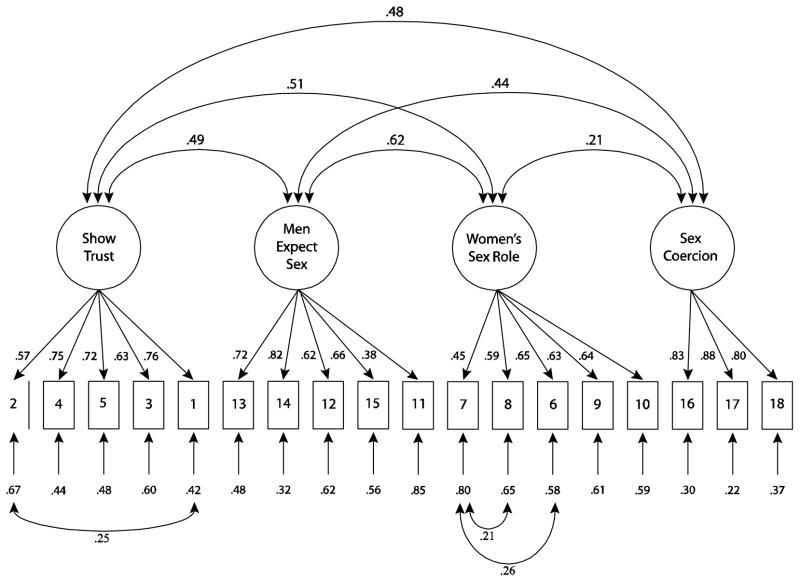

The slightly modified model demonstrated standardized factor loadings for the latent factors that ranged between .57 and .76 for Show Trust, between .45 and .65 for Women’s Sex Role, between .38 and .82 for Men Expect Sex, and between .80 and .83 for Sex Coercion (See Figure 1). All t values for the standardized factor loadings were statistically significant at p < .001. The amount of variance accounted for by the latent factors in their respective indicators is shown in Table 6.

Figure 1.

. Modified Model of the Sexual Pressure Scale-Revised

Table 6.

Variance Contributed by Latent Factors to their Respective Indicators (Study 2)

| Latent Variable and Indicator Number | Description of Indicator a | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| Show Trust | ||

| 2 | I do not ask my partner to use a condom because he may think I had sex | .33 |

| 4 | After we’ve been doing it raw, I can’t start asking my partner | .56 |

| 5 | I’m afraid to ask my partner to use a condom, he might say NO | .52 |

| 3 | He will think I caught something from someone | .40 |

| 1 | He may think I had sex with someone else | .58 |

| Women’s Sex Role | ||

| 7 | It’s a woman’s responsibility to satisfy her man sexually | .20 |

| 8 | A woman needs to please her man sexually to hold onto him | .35 |

| 6 | If my partner wants sex, it’s my responsibility as his woman | .42 |

| 9 | Having sex with my partner will show him that I am the best | .39 |

| 10 | I should have sex with my partner because there are plenty of women | .41 |

| Men Expect Sex | ||

| 13 | My partner makes me feel like I owe him something | .52 |

| 14 | I feel my partner would leave me if I did not have sex | .68 |

| 12 | My partner makes me feel he will cheat if he gets tired of having sex with me | .38 |

| 15 | I have sex with my partner because I am afraid of losing the things he does for me | .44 |

| 11 | My partner makes me feel that I should try new ways to have sex | .15 |

| Sex Coercion | ||

| 16 | My partner has physically hurt after I told him I would not have sex | .70 |

| 17 | My partner has threatened to hurt me after I told him I would not have sex | .78 |

| 18 | My partner has yelled or cursed at me after I told him I would not have sex | .63 |

Indicators as shown are not complete

Construct Validity: Theoretically Related Constructs

The hypothesized theoretical relations were supported: sexual pressure was positively related to HIV sexual risk behavior, r =.23, p =.002 and negatively related to dyadic trust, r = −.26, p <.001. Sexual pressure was negatively related to sexual relationship power, (r = −.55, p< .001) as were the SPSW-R factors (Show Trust, r = −.34, Women’s Sex Role, r = −.29, Men Expect Sex, r = −.54, Sex Coercion, r = −.52, all p’s <.001). Sexual pressure was positively related to sex script video response (SSVR total, r = .21, p =.005). Findings for theoretically related constructs were similar to Study 1, except there was a non-significant relation of the SPSW-R factor, Women’s Sex Role, with sex risk and trust. The Women’s Sex Role mean score was lower in Study 2 (M=11.55, SD =5.5) compared to Study 1 (M=12.12, SD = 5.12), and that may be responsible for the non-significant result.

Reliability

Internal consistency reliability based on Cronbach’s α for the latent factors was satisfactory with a range between .76 and .88 as shown in Table 7. Item-to-total scale correlations for the factor indicators across the latent factor subscales ranged between .33 and .79 suggesting that the indicators are measuring phenomena pertinent to the construct yet still not redundant. Cronbach’s α for the total SPSW-R was .86.

Table 7.

Characteristics of the Sexual Pressure Latent Factors for Study 2 (N=181)

| Latent Factor | # Items | Mean | Std. Dev. | Minimum | Maximum | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Show Trust | 5 | 8.63 | 5.16 | 5.00 | 25.00 | .83 |

| Women’s Sex Role | 5 | 11.55 | 5.49 | 5.00 | 25.00 | .77 |

| Men Expect Sex | 5 | 8.71 | 4.55 | 5.00 | 25.00 | .76 |

| Sex Coercion | 3 | 4.18 | 2.61 | 3.00 | 15.00 | .87 |

| Total SPS-Revised Scale | 18 | 33.06 | 12.96 | 18.00 | 70.00 | .86 |

Discussion

The results of both studies indicate that the SPSW-R is a valid and reliable tool to assess sexual pressure in young adult urban women. Principal components analysis performed in Study 1 resulted in an 18-item 4-factor model that was a more parsimonious solution than the original scale with improved internal reliability. The Condom Fear factor was eliminated from the original SPS because some items loaded on several factors. Removing this factor strengthened both validity and reliability. The original 5-factor scale comprised 62% of the variance in sexual pressure, whereas the 4-factor scale comprised 61% of the variance. Alpha reliability for the original 19-item SPS was .81 with factor reliabilities ranging from .63 to .82. Cronbach’s α for the 18-item SPSW-R was .88 with factor reliabilities ranging from.76 to .85. These findings were repeated in Study 2, revealing a stable 4-factor solution.

In exploratory factor analysis, the first component is that component which extracts the greatest percentage of the total variance (Pedhazur & Schmelkin, 1991), in this case, of sexual pressure. In the original SPS, the first component was Condom Fear and the second was Sex Coercion. In the SPSW-R, the first component was Show Trust and the second was Women’s Sex Role. The revised structure is more congruent with the conceptual definition of sexual pressure, which places greater emphasis on stereotypical gender role expectations, such as the need to show trust, than on physical coercion. Convergent and divergent validities were again supported.

The hypothesized model (tested in Study 2) with slight modification led to a satisfactory fit between the model and data. Correlations among the latent factors are moderate to low suggesting discriminate validity between the constructs. Overall, the moderate to large standardized factor loadings within the respective factors suggest reasonably good convergent validity.

When the residual or error variance of an indicator correlates with the error variance of another indicator in a factor, it suggests that these error variances measure something in common that is not explicitly represented in the factor (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). It is plausible that what is in common between the two error variances in the Show Trust items #1 and #2 is the fear of reprisal. It is also plausible that the correlated errors between Women’s Sex Role items #6 and #7, and #7 and #8, represent lower power, if women are aware of their own needs but follow what is expected of them sexually. According to the conceptual framework, not acting on one’s awareness of choices is an aspect of lower power. Co-varying the error variance of these items improved the model, but further research is needed to confirm these tenets.

Evidence of construct validity was found in the support for the hypothesized positive relations of sexual pressure, sex scripts, and sex risk, and negative relations of sexual pressure with relationship power and trust. The SPSW-R and its factors correlated positively with sex risk and negatively with trust in Study 1 and in Study 2. However, although the SPSW-R factor, Women’s Sex Role, correlated positively with sex risk and trust in Study 1, it did not in Study 2. It is unlikely that sample differences in ethnicity would explain why Women’s Sex Role mean scores were lower in Study 2 than Study 1. In Study 1, mean Women’s Sex Role scores were higher among African American women compared to Latinas. Because there were relatively fewer Latinas in Study 2, higher mean scores would be expected instead of lower scores. No difference by ethnicity was found on the other SPSW-R factors, indicating similarities between African American and Latina urban women in Show Trust, Men Expect Sex, and Sex Coercion. Pleck and O’Donnell (2001) also did not find differences in gender difference beliefs, sexual intercourse, and condom use in early adolescent Black women and Latinas. Further investigation into demographic differences in this stereotypical expectation may be important in tailoring an intervention to reduce sexual pressure.

There are limitations to these two studies. One is the potential for error in self-reported data. Several recommendations by Weinhardt, Forsyth, Carey, Jaworsksi, and Durant (1998) were followed to reduce systematic error in self-reporting, such as; enhancing participant’s memory recall by placing the items in the context of a particular relationship, using ACASI, and limiting the time period of recall to 3 months. Generally, use of ACASI and anonymity are approaches to increase comfort in responding to questions of a personal nature (Jones, 2003; Rogers, 2005; Turner et al., 1998). Although various lengths of recall to measure sex risk behavior have been reported, Noar, Cole, and Carlyle (2006) cautioned against recall of sex risk behavior for a period greater then 3 months, and Schroder et al., (2003) suggested that a reporting period of less than 3 months presents the risk of not obtaining a representative sample of sex behavior. Data were collected in a variety of settings in two adjacent cities in the urban Northeast, and samples were predominately African American and Latina. These were samples of convenience, thus, the findings are not generalizable to other populations, such as younger or older women, women of different cultural backgrounds, or women in suburban or rural areas. The findings of this study suggest that further study in different populations of women is needed to determine if the four-factor structure of the SPSW-R scale based on the framework of sex script theory (Simon & Gagnon, 1986) and the theory of power as knowing participation in change (Barrett, 1998), can be replicated in women of different cultural backgrounds, as well as different geographic areas.

Conclusion

Sexual pressure is a set of gender specific expectations to engage in sex or fear reprisal in the form of losing the benefits of the relationship, the male partner abandoning the relationship, and/or coercive threats or force. Sexual pressure is a complex, multidimensional construct that is broader than sexual coercion. The discrimination of Show Trust, the pressure to communicate trust by engaging in unprotected sex, from relationship trust is a consistent finding. Results of exploratory and confirmatory analyses in the two studies supported a 4-factor SPSW-R structure. Reliabilities of the SPSW-R total and subscales were very satisfactory suggesting use of the scale in intervention research. A key attribute of sexual pressure is awareness of limited choices that are bound by a socially available, yet narrow, stereotypical vision of women and sexual expression. Women’s relationship needs that manifest in lower power sex scripts involving unprotected sex; may be addressed by promoting the ideas and behaviors of higher power scripts, particularly as both scripts are contemporary expressions among young urban women. Further study is needed to test the SPSW-R in women with different cultural backgrounds and environments.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants to the first author from the National Institute of Nursing Research (RO3 NR009349), the National Library of Medicine (G08 LM008349) and the Rutgers University Busch Biomedical Research Grant. The authors gratefully acknowledge Kianna Cromedy, Shauday Rodney, Tina Truncellito, and Esmeralda Valle for their insights and assistance with data collection, the directors of participating public housing developments, the public recreation center, and the STD clinic, and especially the women who participated in these studies.

Contributor Information

Rachel Jones, Assistant Professor, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, College of Nursing, Ackerson Hall, 180 University Ave, Newark, NJ 07102, Telephone 973-353-5326, Fax 973-353-1943.

Elsie Gulick, Professor Emeritus, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, College of Nursing.

References

- Albarracin D, Ho RM, McNatt PS, Williams WR, Rhodes F, Malotte CK, et al. Structure of outcome beliefs in condom use. Health Psychology. 2000;19:458–468. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.5.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SA. Sex under pressure: Jerks, boorish behavior, and gender hierarchy. Res Publica. 2005;11:349–369. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett EAM. A Rogerian practice methodology for health patterning. Nursing Science Quarterly. 1998;11:136–138. doi: 10.1177/089431849801100402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS and women. 2007a Retrieved April 17, 2008, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/women/overview_partner.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fighting HIV/AIDS among African Americans: A heightened national response. 2007b Retrieved April 17, 2008, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/aa/resources/factsheets/pdf/AA_response_media_fact.pdf.

- Eagley AH, Wood W. The origins of sex differences in human behavior: Evolved dispositions versus social roles. In: Travis CB, editor. Evolution, gender, & rape. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2003. pp. 383–411. [Google Scholar]

- Emmers-Sommer TM, Allen M. Safer sex in personal relationships: The role of sexual scripts in HIV infection and prevention. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gavey N, McPhillips K. Subject to romance: Heterosexual passivity as an obstacle to women initiating condom use. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1999;23:349–367. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Bushman BJ. Relation between perceived vulnerability to HIV and precautionary sexual behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119:390–409. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynie M, Lydon JE. Women’s perceptions of female contraceptive behavior. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1995;19:563–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1995.tb00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynie M, Lydon JE, Cote S, Weiner S. Relational sexual scripts and women’s condom use: The importance of internalized norms. Journal of Sex Research. 1998;35:370–380. [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. Survey data collection using audio computer assisted self-interview. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2003;25:349–358. doi: 10.1177/0193945902250423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. Relationships of sexual imposition, dyadic trust, and sensation seeking with sexual risk behavior in young urban women. Research in Nursing & Health. 2004;27:185–197. doi: 10.1002/nur.20016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. Reliability and validity of the Sexual Pressure Scale. Research in Nursing & Health. 2006a;29:281–293. doi: 10.1002/nur.20142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. Sex scripts and power: A framework to explain urban women’s HIV sexual risk with male partners. Nursing Clinics of North America. 2006b;41:425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R, Oliver M. Young urban women’s patterns of unprotected sex with men engaging in HIV risk behaviors. AIDS & Behavior. 2007;11:812–821. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9194-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbon D. LISREL (Version 8.8). [Computer Software] Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway EK. Using LISREL for structural equation modeling: A researcher’s guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA. Sexual Experiences Survey: Reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:422–423. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Oros CJ. Sexual Experiences Survey: A research instrument investigating sexual aggression victimization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:455–457. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahe B. Sexual scripts and heterosexual aggression. In: Eckes T, Trautner HM, editors. The developmental social psychology of gender. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 273–292. [Google Scholar]

- Larzelere RE, Huston TL. The Dyadic Trust Scale: Toward understanding interpersonal trust in close relationships. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1980;42:595–604. [Google Scholar]

- Metts S, Spitzberg BH. Sexual communication in interpersonal contexts: A script-based approach. In: Burleson BR, editor. Communication yearbook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. pp. 49–91. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Morokoff PJ, Quina K, Harlow LL, Whitmire L, Grimely DM, Gibson PR, et al. Sexual Assertiveness Scale (SAS) for women: Development and validation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:790–804. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.4.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Cole C, Carlyle K. Condom use measurement in 56 studies of sexual Risk: Review and Recommendations. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2006;35:327–345. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris AE, Aroian KJ. To transform or not transform skewed data for psychometric analysis: That is the question! Nursing Research. 2004;53:67–71. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200401000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. 3. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Vicioso KJ, Punzalan JC, Halkitis PN, Kutnick A, Velasquez MM. The impact of alcohol use on the sexual scripts of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. The Journal of Sex Research. 2004;41:160–172. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedhazur EJ, Schmelkin LP. Measurement, design, and analysis: An integrated approach. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pleck J, O’Donnell LN. Gender attitudes and health risk behaviors in urban African American and Latino early adolescents. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2001;5:265–272. doi: 10.1023/a:1013084923217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research: Principles and methods. 7. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, & Williams; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Amaro H, De Jong W, Gortmaker SL, Rudd R. Relationship power, condom use and HIV risk among women in the USA. AIDS Care. 2002;14:789–800. doi: 10.1080/0954012021000031868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Gortamker SL, DeJong W. Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/STD research. Sex Roles. 2000;42:637–660. [Google Scholar]

- Quina K, Harlow LL, Morokoff PJ, Burkholder G. Sexual communication in relationships: When words speak louder than actions. Sex Roles. 2000;42:523–549. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SM. Audio computer assisted self interviewing to measure HIV risk behaviors in a clinic population. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2005;81:501–507. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.014266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder KE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behavior: II. Accuracy of self-reports. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26:104–123. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2602_03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon W, Gagnon JH. Sexual scripts: Permanence and change. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1986;15:97–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01542219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JL, Salovey P. Organized knowledge structure and personality: Person schemas, self schemas, prototypes, and scripts. In: Horowitz MJ, editor. Person schemas and maladaptive interpersonal patterns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1991. pp. 33–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sionean C, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby R, Cobb BK, Harrington K, et al. Psychosocial and behavioral correlates of refusing unwanted sex among African-American adolescent females. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30:55–63. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00318-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 4. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Travis CB, White JW. Sexuality, society, and feminism. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL, et al. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward LM, Hansbrough E, Walker E. Contributions of music video exposure to Black adolescents gender and sexual schemas. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2005;20:143–166. [Google Scholar]

- Weinhardt LS, Forsyth AD, Carey MP, Jaworsksi BC, Durant LE. Reliability and validity of self-report measures of HIV-related sexual behavior: Progress since 1990 and recommendations for research and practice. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1998;27:155–180. doi: 10.1023/a:1018682530519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]