Abstract

Self-reactive B cells not controlled by receptor editing or clonal deletion may become anergic. We report that fully mature human B cells negative for surface IgM and retaining only IgD are autoreactive and functionally attenuated (referred to as naive IgD+IgM− B cells [BND]). These BND cells typically make up 2.5% of B cells in the peripheral blood, have antibody variable region genes in germline (unmutated) configuration, and, by all current measures, are fully mature. Analysis of 95 recombinant antibodies expressed from the variable genes of single BND cells demonstrated that they are predominantly autoreactive, binding to HEp-2 cell antigens and DNA. Upon B cell receptor cross-linkage, BND cells have a reduced capacity to mobilize intracellular calcium or phosphorylate tyrosines, demonstrating that they are anergic. However, intense stimulation causes BND cells to fully respond, suggesting that these cells could be the precursors of autoantibody secreting plasma cells in autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus or rheumatoid arthritis. This is the first identification of a distinct mature human B cell subset that is naturally autoreactive and controlled by the tolerizing mechanism of functional anergy.

During B cell development, the near random nature of the VDJ recombination process leads to the unavoidable production of self-reactive antibodies. In fact, studies in humans have demonstrated that many if not most newly generated B cells are autoreactive (1). Extensive studies of self-tolerant B cells in transgenic mouse models have revealed the complicated systems of B cell selection used to avoid autoimmunity. Current models suggest that B cells expressing a transgenic surface Ig that binds DNA or protein autoantigens first attempt to alter the B cell receptor (BCR) by further variable gene rearrangement using “receptor editing” (2, 3). If receptor editing is unsuccessful, then the offending B cell may be eliminated by clonal deletion (4, 5) or it may enter maturity but with reduced or altered function so that it no longer reacts to the self-antigens, which is referred to as clonal anergy (6–8). In this paper, we describe a human B cell population that is anergic. Clonal anergy was first conceived by Nossal and Pike in 1980 (6) to explain why injection of neonatal mice with high dosages of an antigen induced deletion of the specific B cells, whereas lesser dosages allowed retention of the specific B cells, but the cells were incapable of becoming antibody-secreting cells. In 1988, Goodnow et al. (8) demonstrated and characterized B cell anergy in vivo using the MD4/ML5 transgenic mouse model in which all B cells were self-specific to the neoself antigen hen egg lysozyme (HEL), and so cells surviving to maturity became anergic, having reduced surface BCR density, reduced proliferation and antibody secretion, and reduced Ca2+ flux and tyrosine phosphorylation responses (9–11).

The level and form of tolerance induction and the decision between anergic states or deletion is dependent on antigen form, specificity, and location of encounter. For example, soluble forms of the HEL (neoself) antigen allow survival of anti-HEL (autoreactive) but anergic B cells, whereas membrane-conjugated forms of HEL induce extensive deletion of HEL-specific B cells (12). It has recently been demonstrated that in the HEL model of anergy, the B cells are arrested at the immature transitional 3 (T3) stage of B cell development (13). In fact, it appears that all T3 B cells are naturally anergic even if the specificity is unknown (13, 14). Other levels of B cell functional inactivation or anergy vary depending on the particular autoantigen specificity of the transgenic mouse model (for review see reference 15). Antiinsulin B cells maintain normal levels of BCR signaling, such as calcium mobilization, but are attenuated for T cell–dependent responses, proliferation, and Ig production after toll-like receptor induction (16, 17). Anti-DNA B cells (VH3H9) that are specific for both double-stranded DNA (dsDNA; 3H9 × Vk4) or single-stranded DNA (ssDNA; 3H9 × Vk8) are each limited in their secretion of DNA-specific antibodies but vary for other functions. Although the ssDNA-reactive B cells have a relatively normal response to BCR cross-linking, the dsDNA-reactive B cells are unresponsive, they have limited proliferation responses, and they are blocked in development at the immature B cell stage (18–20). Intriguingly, a different anti-ssDNA transgenic mouse model (Ars/A1) is developmentally arrested at the T3 stage and has reduced BCR signaling, no proliferation, and no antibody secretion upon BCR cross-linking (13, 21). Transgenic B cells binding Smith (Sm) antigen are fairly normal but they only proliferate weakly and do not become fully mature plasma cells (22). Finally, in humans, B cells with natural autoreactivity for polylactosamine chains (the 9G4 idiotype) are excluded from normal B cell responses (23–25) and have attenuated BCR signaling capacity but appear to function normally in lupus patients (26). However, because natural autoreactivity is difficult to detect, little is known about the fate and phenotype of most autoreactive B cells in humans.

In this paper, we describe a population of naive-like human B cells that do not express IgM, only IgD (BND cells for short). Analysis of recombinant monoclonal antibodies demonstrated that most BND cells are autoreactive, binding antigens on human HEp-2 cells or DNA. The autoreactivity occurs naturally, as the cells have completely germline (unmutated) variable genes and are fully mature by all measures. We suspected that the autoreactive receptors of BND cells might lead to chronic stimulation and induction of anergy. Indeed, based on analysis of calcium flux and phosphorylated tyrosine (pTyr) levels after BCR cross-linkage, BND cells are functionally attenuated. Because BND cells can be fully activated by sufficient stimulation, we propose that these cells may be the precursors that become high-affinity autoreactive B cells in diseases such as lupus or rheumatoid arthritis. The functional characterization of naturally autoreactive and anergic B cells herein is a critical step toward understanding and treating B cell mediated autoimmune pathology.

RESULTS

IgD+IgM− naive B cells from healthy humans express predominantly self-reactive BCRs

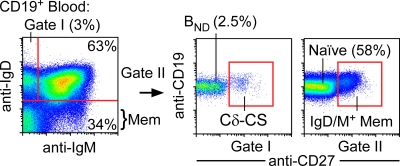

In transgenic mouse models of tolerance, B cells that predominantly express IgD isotype BCRs with low levels of surface IgM are anergic (9). We hypothesized that IgD+IgM−CD27− naive B cells of healthy humans (Fig. 1) might also be predominantly autoreactive and anergic. We therefore expressed recombinant monoclonal antibodies from isolated single B cells to test the specificity of naive B cell fractions (CD27−) that were IgD+IgM+ (true naive) versus IgD+IgM− BND cells. BND cells made up 1–10% (typically 2.5 ± 0.716%, SEM) of the naive B cells of 40 healthy adult blood donors (Fig. 1). Single B cells were sorted by flow cytometry into 96-well plates and amplified by multiplex single-cell RT-PCR to identify and clone the Ig heavy and light chain genes from a random assortment of B cells. To ensure that functional transcripts were cloned, RT-PCR primers were targeted to the variable gene leader sequences and to the respective constant region exons (Cμ, Cδ, Cκ, or Cλ). The variable genes were then cloned into expression vectors and expressed with IgG and Cκ or Cλ constant regions in the 293A human cell line (1, 25, 27).

Figure 1.

BND cells are gated as the IgD+IgM−CD27− cell fraction. Peripheral blood B cells (CD19+) from humans are separated according to expression of IgM and IgD and then can be further distinguished by the CD27 expression that is found on memory B cells and plasma cells. On average, 3% of all B cells are found in the IgD-only fraction (gate I) where we find BND cells (2.5%), which can be further distinguished from another IgD-only population in blood, Cδ-CS cells (0.5%), by CD27 expression. Naive B cells, representing the bulk of peripheral blood B cells (58%), are found in the double-positive fraction (gate II) and can be further separated from IgD+, IgM+, memory, or marginal zone (MZ) cells by CD27 expression. The remaining fractions (IgM only and double negative) represent IgM memory and class-switched memory B cells, respectively, and are CD27+. All population percentages shown here represent the averages from analysis of 40 healthy adult blood donors.

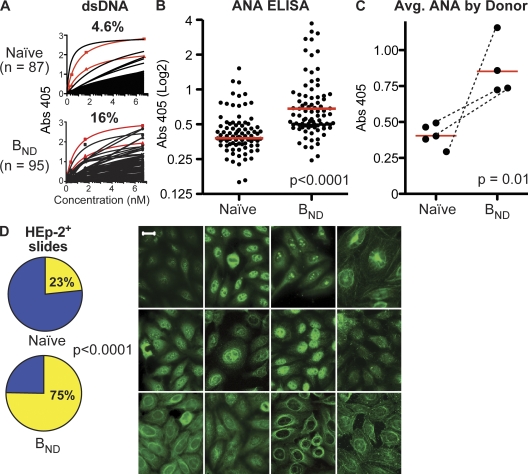

The production of antibodies that react to dsDNA are generally diagnostic of a pathological state in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and other autoimmune diseases (28–30). BND cells produced anti-DNA reactivity nearly fourfold more frequently than naive B cells in a relative comparison. The frequency of anti-DNA antibodies produced from naive versus BND cells was evaluated by ELISA. Antibodies were expressed from 87 naive B cells (n = 16, 37, 10, 10, and 14 by donor) and from 95 BND cells (n = 17, 21, 30, and 27 by donor). For comparison, we also expressed the variable genes encoding two well characterized antibodies that are used commonly to study anti-DNA reactivity (Fig. 2 A, red lines), including 3H9 (Fig. 2 A, squares) (2), and HN241 (Fig. 2 A, triangles) (29). Anti-DNA binding affinity was determined by regression analysis of the binding curves (see Materials and methods). The positive control antibody 3H9 was used to normalize all ELISA plates. Antibodies with BMAX absorbencies that were greater than the 95% confidence interval of the low positive control (HN241) and had measured affinities of >7 nM (half-maximal binding at ∼1 μg/ml) were scored as DNA binding. As indicated, of 95 antibodies from BND cells, 16% bound dsDNA, which is nearly fourfold more frequent than antibodies from the 87 naive cells, of which 4.4% bound dsDNA. The frequency of naive cells binding DNA was also similar to that reported previously by Wardemann et al. (1), whereas BND cells bound DNA at a frequency similar to that of early immature B cells before B cell selection. Analysis of insulin or LPS binding by ELISA found that although DNA-binding antibodies from naive cells are often polyreactive, only half of the BND cell–derived antibodies were polyreactive, and the remainder bound only DNA (Fig. S1, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20080611/DC1).

Figure 2.

BND cells express autoreactive antibodies. Recombinant monoclonal antibodies were expressed by transfection of human 293 cells with the variable genes from single BND (totaling 95 clones; n = 17, 21, 30, and 27) or naive B cells (totaling 87 clones; n = 16, 37, 10, 10, and 14 by donor) and tested for binding to dsDNA and to antigens within the human HEp-2 cell line. (A) ELISA analysis to determine the frequency of BND and naive B cells that bind to dsDNA. The variable genes encoding classical anti-DNA antibodies were also added (red lines), including 3H9 (squares) (2), and HN241 (triangles) (29). Both control antibodies were expressed as chimeric mouse/human IgG-κ recombinant monoclonals identically to the naive and BND antibodies so that all capture and detection reagents used were identical. Absorbencies were measured at OD415 (y axis) and normalized to the 3H9-positive control antibody included on every plate. Binding to DNA is plotted for the various antibodies at 1 μg/ml (6.67 nM) and three additional fourfold serial dilutions (x axis indicates nanomoles). Saturation curves were used to calculate relative affinities to determine if antibodies were positively reactive. (B) ELISA screens were performed to determine the amount of ANA reactivity. The BND and naive monoclonal antibodies from A were loaded at a concentration of 25 μg/ml onto commercially available ANA antigen ELISA plates. Absorbencies were measured at OD415 and compared and normalized to an in house positive clone, Cδ-CS clone B09 (25). The absorbencies of naive versus BND clones were significant by either Student's t test to compare means or Mann-Whitney to compare the medians (P < 0.0001 for either test; median absorbancies are indicated as red lines). (C) Antibody absorbencies from B averaged and compared by donor for naive population and BND population, including three matched comparisons of naive versus BND antibodies indicated with dotted lines. The BND cells were more often ANA reactive on average between donors (P < 0.02 by Student's t test with Welch's correction for unequal variance and P = 0.016 by Mann-Whitney test in comparing the medians). (D) HEp-2 reactivity was verified using immunofluorescence. Of the 95 antibodies derived from BND cells, 72 (75%) were clearly reactive with human HEp-2 cells. 20/87 (23%) of the antibodies from naive cells were HEp-2 reactive. Representative antigen binding patterns on HEp-2 slides for antibodies from BND cells are shown. Significance was established by χ2 analysis; P < 0.0001. Commercial HEp-2 slides were stained with recombinant monoclonal antibodies and with antihuman IgG-FITC secondary antibody and visualized using fluorescence microscopy. Bar, 20 μm.

Analysis of sera antibodies for binding to HEp-2 cells detected by indirect immunofluorescence is a classical test of autoreactivity. This antinuclear antibody (ANA) test is commonly used to assist with diagnosis of autoimmune diseases such as SLE (31). Three-quarters (72/95 or 75%) of the antibodies derived from BND cells were clearly reactive with human HEp-2 cells (Fig. 2 D, left). In contrast, consistent with previous reports (1, 25), only 23% (20 of 87) of the antibodies from naive cells bound to HEp-2 antigens (P < 0.0001 by χ2; Fig. 2 D, left). The HEp-2 binding patterns detected were quite variable, indicating a variety of autoreactivities, but, notably, the majority of BND cell antibodies bound to cytoplasmic antigens (Fig. 2 D, right). In addition, a quantitative assessment of the HEp-2 reactivity was determined using commercial ELISA-based ANA kits (Fig. 2 B). These assays demonstrated that ANA binding was significantly higher in the BND population compared with the naive cell antibodies both when mean or median binding is assessed for all antibodies (P < 0.0001 for either Student's t test or Mann-Whitney test; Fig. 2 B) and when compared between donors (P < 0.02 by Student's t test with Welch's correction for unequal variance and P = 0.016 by Mann-Whitney test; Fig. 2 C). In conclusion, unlike IgM+IgD+ naive B cells, most BND cells express autoreactive Igs.

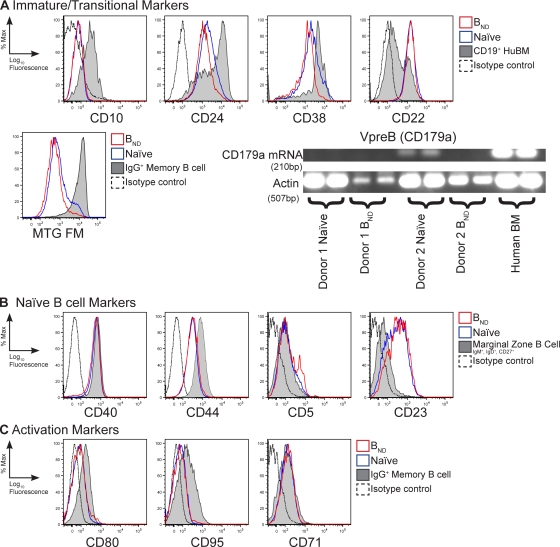

BND cells are mature naive-like B cells

As immature B cells before completing primary selection may be autoreactive, we hypothesize that BND cells might be immature. However, BND cells do not express markers found on immature B cells such as the B cell progenitor marker CD10 and, like mature cells, express only low levels of the development markers CD38 and CD24, which are commonly used to distinguish recent BM immigrant immature/transitional B cells that are CD38hiCD24hi (Fig. 3 A) (32). Furthermore, the BND and naive populations are both positive for the BCR-associated regulator CD22 that is expressed on mature B cells (33). In addition, recent reports have demonstrated that transitional B cells, as well as CD27+ IgG+ memory cells, in circulation can be distinguished because they do not express the ATP binding cassette ABCB1 transporter and, subsequently, they retain mitochondrial dyes such as Rhodamine 123 or MitoTracker Green (MTG) (34). Like naive cells, BND cells actively extrude MTG, further demonstrating that they are neither transitional B cells nor are they memory cells (Fig. 3 A, middle). Finally, BND cells do not produce CD179a (surrogate light chain; VpreB) transcripts, which distinguishes them from an autoreactive population of naive B cells that are in the process of receptor editing (35, 36) (Fig. 3 A, bottom).

Figure 3.

The BND phenotype is naive mature B cells. Peripheral blood B cells were isolated and stained with anti-CD19, CD27, IgM, and IgD, as well as one of each of the antibodies shown in the figure, to delineate phenotype differences between BND and naive populations for immaturity (A), maturity (B), or activation markers (C). Isotype controls were included and, where appropriate, CD19+ human BM, marginal zone–like peripheral blood B cells (CD19+, CD27+, IgM+, and IgD+), or fractions representing IgG memory B cells (CD27+, IgM−, and IgD−) were included for an internal positive and negative control. Histograms are representative of three to eight donors in at least three independent experiments. RT-PCR analysis was performed on sorted BND and naive cells for the presence of VpreB (CD179a) transcripts. Actin RT-PCR was included as a template control.

Besides IgD expression, BND cells also express other molecules found only on mature circulating B cells including CD23, CD44, and CD40 (Fig. 3 B). Lack of CD38 also distinguishes BND cells from germinal center and plasma cells. Furthermore, like naive cells, BND cells are not proliferating (CD71−) and express neither the T cell costimulatory molecule CD80 nor the programmed cell death receptor CD95 (Fas), which are found on germinal center and memory B cells (Fig. 3 C). Finally, like naive cells, most BND cells express little CD5 protein (Fig. 3 B) but, interestingly, included some cells that were CD5low, which is consistent with previous reports that CD5 expression is heterogeneous for various human B cell subsets (37). CD5 expression in mice marks the B1a subset of innate B cells and is known to be involved in negative regulation (38). The distinction of CD5 as a lineage marker is not established for human B cell populations, but it has been proposed to be a marker of activation (39). Although a connection of BND cells to a B1 cell type can't be completely ruled out, we conclude that in addition to autoreactive BCRs, BND cells are mature resting B cells that are most similar to naive B cells.

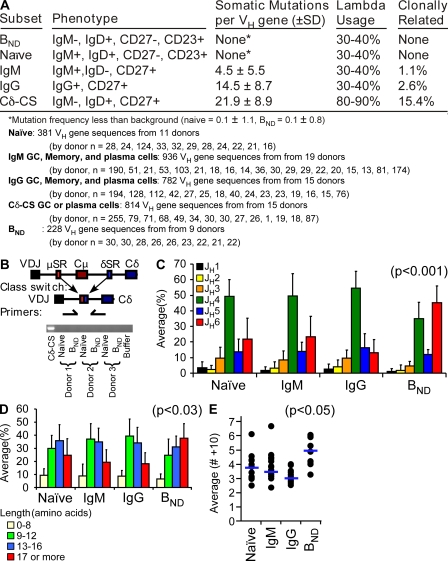

BND cells are naturally autoreactive, having no evidence of previous immune experience

Activated B cells rapidly proliferate and accumulate somatic mutations in the antibody variable genes to hone the specificity of the BCR. The cells also undergo class switch recombination to alter the antibody isotype. Variable regions from 228 gene sequences were analyzed from BND cells of nine blood donors and compared with historical data in the laboratory from various other B cell subpopulations (24, 25, 40–42). BND cells were analyzed from the four donors that antibodies were derived plus an additional five blood donors. As indicated in Fig. 4 A, there were no somatic mutations on the BND cell variable genes, indicating that the autoreactivity detected is natural and not generated during an immune response. In addition, no two BND cells sharing the same VDJ junctions were detected, likely indicating that they have not been clonally expanded. Finally, there is a small population of germinal center, memory, and plasma cells that have class switched to IgD at the genetic level (referred to as Cδ-CS) and so are also IgD+IgM− (43, 44). These cells also express autoreactive IgD receptors (25). However, PCR analysis found no evidence of recombination junctions between the μ and δ switch regions for BND cells (Fig. 4 B), indicating that IgD is expressed as a splice product of VDJ-Cμ-Cδ transcripts and that BND cells have not undergone class switch recombination. Cδ-CS B cells also have excessive somatic mutations of the variable genes and use predominantly Igλ light chains, further distinguishing them from BND cells (Fig. 4 A). Interestingly, further indicating an autoreactive phenotype (1, 24, 35), BND cells use predominantly JH6 gene segments to encode antibodies (Fig. 4 C). In addition, variable genes from B cells of humans with lupus and in mouse models of lupus (mrl/lpr mice) tend to have long CDR segments (45–47). Cells with long CDR3s are also counterselected during normal human B cell development (1). As indicated in Fig. 4, both the frequency of BND cells with long CDR3 segments (Fig. 4 D) and the mean CDR3 length (Fig. 4 E) is significantly increased for BND cells. In conclusion, BND cells are naturally autoreactive with no evidence of ever having been involved in an immune response.

Figure 4.

The variable region sequences suggest that BND cells are most like naive cells. (A) Sequence analysis from several healthy donors of BND, naive, IgG and IgM memory, and Cδ-CS (C-delta class switch) revealed that BND cells, like naive cells, did not have somatic mutations in the variable region, are not clonally related as determined by common CDR3s, and use predominantly κ light chains. (B) PCR of genomic DNA for the constant chain switch regions between μ and δ revealed no DNA recombination at the delta locus and, thus, the BND cells are not class switched to DNA at the genomic level. (C) Comparison of heavy chain sequences for mean (±SD) JH gene segment usage revealed increase use of JH6 (red bars) in BND cells compared with JH6 usage in naive, IgM, and IgG populations (P < 0.001 by Student's t test between the BND JH6 and separately JH6 in naive, IgM, and IgG populations; n values listed under the table in A). (D and E) BND cells had more amino acids on average (±SD) in their CDR3s as determined both by the frequency of cells with long CDR3s (17 aa+; red bars; P < 0.03) and the mean CDR3 length for each donor (points) and averaged for all donors (blue bars) as compared with the other blood B cell populations (E; P < 0.05; scale is amino acids >10).

BND cells display reduced mobilization of intracellular calcium after BCR cross-linkage

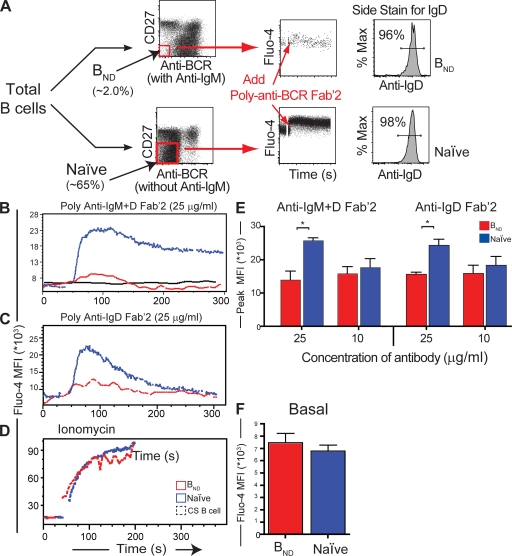

In mouse models, self-reactive B cells that constitutively bind autoantigens become anergic, resulting in diminished downstream signaling events upon BCR cross-linkage (11, 48–50). We hypothesized that the BND cell population would also exhibit reduced signaling capacity upon activation because they are autoreactive. Immediately detectable measurements of BCR signaling that are reduced in anergic B cells of mice include the degree of intracellular calcium flux and an overall decreased level of pTyr. To avoid prematurely stimulating the B cells, thus depleting calcium stores and affecting pTyr levels, a negative enrichment scheme was used to isolate the BND and control B cell populations. In brief, BND and naive B cells were enriched by differentially staining peripheral blood CD27− B cells loaded with the calcium dye Fluo-4 either in the presence or absence of anti-IgM so that we could identify BND or naive cells, respectively (Fig. 5 A and Materials and methods). Baseline intracellular calcium levels were established for 30 s, followed by treatment with various anti-BCR antibodies. Physiologically, antigen should bind all surface Ig regardless of isotype (i.e., IgD versus IgM). Therefore, to most accurately mimic physiological stimulation with antigen, we first used combined anti-IgM plus anti-IgD cross-linkage to stimulate the B cells. Upon anti-IgD/IgM stimulation, the BND population showed a dramatically decreased ability to flux intracellular calcium compared with a substantial biphasic flux from the naive population (Fig. 5 B). In comparison, the BND population gave a result similar to CD27+IgM/D/G− B cell (class switched) memory population representing both IgA and IgE memory cells, which, as predicted, do not respond to anti-IgD/IgM stimulation. Representative kinetic graphs are shown for 25 μg/ml of anti-IgM/D stimulant, representing three separate donors. Similar trends were also observed when various amounts of stimulant ranging from 10–50 μg/ml were used, representing eight donors in three independent trials. On average, the peak mean fluorescence of Flou-4 was significantly higher for naive versus BND, which is indicative of a more robust flux of intracellular calcium (Fig. 5 E; P < 0.05 by Student's t test). Similarly, BCR cross-linking with anti-κ/λ resulted in reduced BND calcium flux (Fig. S2 B, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20080611/DC1). This difference was not caused by a variegated uptake of the calcium dye Fluo-4 or reduced viability because calcium peaks between the BND and naive populations were equal when treated with the ionophore ionomycin (Fig. 5 D).

Figure 5.

BND cells have attenuated calcium responses compared with naive cells after BCR cross-linking. (A) A representative scheme of isolation and negative enrichment for the BND and naive populations. Negatively enriched B cells from human peripheral blood were split into two equal fractions: one stained with anti-CD27, anti-IgM, and anti-IgG (anti-BCR) to negatively gate BND cells and the other with anti-CD27 and anti-IgG (anti-BCR) to negatively gate naive cells. Cells were loaded with calcium dye Fluo-4 (Invitrogen) and transferred to flow cytometer, warmed to 37°C, and treated with different amounts and combinations of polyclonal Fab'2 BCR cross-linkers. Side stains were performed with these antibodies plus anti-CD19 and anti-IgD to test for population purity. In each case, B cell purities were >98% and BND and naive purities were >96% as indicated. Calcium curves were determined using average mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) over time. (B) Representative kinetic graphs of average Flou-4 MFI over time for naive, BND, and a B cell class-switched memory control (CS B cell) population representing IgA/E+ memory cells (CD27+, IgM−, IgG−, and IgD−; black line). Basal levels were established for 30 s and then the cells were treated with 50 μg/ml of anti-IgM Fab'2/anti-IgD Fab'2, 50 μg/ml of anti-IgD Fab'2 alone (C), or 20 μg/ml ionomycin (D). (E) Maximal peak fluorescence of Fluo-4 was averaged ±SD for B and C (*, P < 0.05; n = 3 donors; Student's t test). (F) Mean fluorescence of Fluo-4 ±SD representing the basal levels (the first 30 s) was calculated showing a slightly higher amount in the BND population.

One possibility was that the reduced calcium response was because the BND population expresses only surface IgD whereas naive cells also express IgM (Fig. 1), thus resulting in different frequencies of BCR cross-linkage or in qualitative differences in the signaling cascade. To gain functional insight, the cells were stimulated with anti-IgD alone. Anti-IgD alone also resulted in significantly less activation of the BND than the naive population (Fig. 5, D and E; P < 0.05 by Student's t test). This indicates that the reduced signaling capacity in the BND population was caused by an intrinsic overall reduction in receptor mediated signaling.

As reported for anergic B cells in mice (48, 51; for review see reference 15), basal calcium levels for the BND population were 10% higher on average than for naive cells, which is consistent with chronic stimulation by self-antigen (Fig. 5 F). We conclude from these experiments that BND cells have intrinsically attenuated BCR-induced calcium flux and that this anergized phenotype likely results from chronic exposure to self-antigen in vivo.

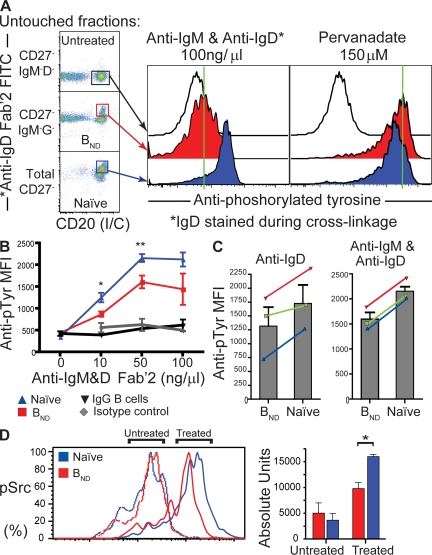

BND cells accumulate less pTyr when activated by BCR cross-linking

In addition to calcium flux, the signaling cascade seconds and minutes after BCR cross-linkage results in overall increases of cellular pTyr levels. Because relatively few BND cells can be isolated at any one time from human peripheral blood, we chose to analyze pTyr levels by using flow cytometry or “PhosFlow.” This powerful technique allows the quantification of both the pTyr magnitude for each individual cell and the frequency of cells affected. With this assay, total activated B cells are rapidly fixed seconds after receptor cross-linkage and before any manipulation that might reduce detectable pTyr levels. The phenotypes and pTyr levels of individual cells can then be resolved retrospectively by using immunostaining and detection on a flow cytometer (Fig. 6 A). Each B cell population was fractionated and depleted of other cell types. Naive and BND cells were first enriched through sorting with anti-CD27 and anti-IgM antibodies. Naive cells are predominantly in the total CD27− fraction, BND cells are predominantly in the IgM−CD27− fraction, and untreated cells that will not be activated by anti-IgM/D treatment are predominantly in the CD27−IgD−IgM− fraction (determined separately to be mostly IgG, IgA, or IgE+ B cells). By spiking the anti-IgM/IgD Fab′2 cross-linking mix with a fluorescently labeled (FITC) anti-IgD and then staining with intracellular anti-CD20 and anti-pTyr after stimulation, fixation, and permeabilization, we could gate and resolve each B cell population to high purity (Fig. 6 A, left). As indicated in the middle of Fig. 6 A, poststimulation pTyr levels were much greater in naive B cells than in BND cells after treatment with a combination of polyclonal anti-IgD/IgM for an optimal 45 s (determined separately to be the peak of activation; Fig. S2 A). The reduced pTyr induction is not caused by increased cell death or lack of viability in the BND population, as both they and naive cells are stimulated to the same level with the phosphatase inhibitor pervanadate (orthovandate H2O2; Fig. 6 A, right histogram).

Figure 6.

BND cells have reduced tyrosine phosphorylation, suggesting that they are natural anergic B cells. (A) Representative histogram of treated BND and naive cells sorted according to a least-touch strategy (see Materials and methods). 105 cells were incubated with anti-IgD Fab'2-FITC + IgM Fab'2 for 45 s at various concentrations, fixed, and permeabilized, followed by staining by anti-pTyr and intracellular anti-CD20. Histograms were built by FACS analysis and treated populations were compared with untreated controls. Cells were also stimulated with pervanadate as a positive control (right histogram). Green lines are used as qualitative references to mark the median fluorescence of the untreated controls, allowing a visual comparison of fluorescence shift with treated samples. (B) Cells were stimulated with anti-IgD Fab'2 FITC + IgM Fab'2 at concentrations of 10, 50, and 100 μg/ml to determine concentration dependency and were plotted as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ± SD of pTyr-PE (for each concentration point, n = 3 groups of 1–3 donors; *, P < 0.05 and **, P < 0.01 for 10 and 50 μg/ml, respectively, by Student's t test). Class switched B cells could also be gated (IgD−, IgM−, and CD20+; black line) from the peripheral set and are included as an internal negative control. Isotype controls (gray line) were established for the stimulated fractions. (C) Incubation of BND and naive cells with 50 μg/ml of anti-IgD Fab'2 alone or in combination with anti-IgM. Results of three donors are plotted as MFI of pTyr. Error bars represent the mean ± SD. Color lines represent individual donor variation between naive and BND population. (D) Cells were sorted as in A but stained with antiphosphorylated Src (pTyr 416; pSrc). Representative histograms are shown for naive and BND cells, untreated and treated with anti-IgD Fab'2 FITC + anti-IgM Fab'2. Bar graphs represent the mean absolute number of units/molecules ±SD of phosphorylated Src as determined by Sphero Rainbow Calibration beads (Invitrogen) from three healthy donors and compared between BND (red) and naive (blue) populations for both treated and untreated fractions. Significance for treated fractions (P < 0.05) was established by a Student's t test.

On average, from multiple blood samples, BND cells accumulated significantly less total tyrosine phosphorylation than naive cells at various anti-IgD/IgM concentrations (Fig. 6 B; significance for 10 and 50 μg/ml is P < 0.05 and 0.01, respectively by Student's t test). Each point in Fig. 6 B represents the mean and SD for at least three independent analyses of BND or naive cells pooled from at least three different donors for each repetition. As with calcium, treatment with anti-IgD alone also caused greater reduction in pTyr induction in BND cells than in naive B cells for each of three trials (Fig. 6 C). The red, green, and blue lines represent the cells from independent blood donors simultaneously assayed for anti-IgD alone (Fig. 6 C, left) or in combination with anti-IgM (Fig. 6 C, right). More specifically, Src family tyrosine kinases (Lyn, Fyn, and Blk), which are known to be important for transducing signals directly associated with receptor cross-linking, were evaluated for activation through detection of pTyr residue 416. Using calibration beads to establish absolute units, we found that in comparison to naive cells the BND population had reduced pSrc levels upon treatment with anti-IgD and anti-IgM (Fig. 6 D; P < 0.05 by Student's t test, based on three independent trials). In summary, pTyr levels were reduced for BND cells after cross-linking in every instance for 12 independent trials (totaling 30 pooled blood donors). Interestingly, if BND cells were rested overnight in culture, they phosphorylated tyrosines and fluxed calcium at similar levels as naive cells (Fig. S3 E, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20080611/DC1), which is consistent with observations in transgenic mice where removal of the chronic self-stimulation rapidly allows return to a nonanergic state (52).

In conclusion, likely because of chronic self-stimulation, BND cells are anergic, displaying reduced activation levels after BCR cross-linkage. This analysis suggests that BND cells have a decreased ability to respond to antigen binding, thus avoiding the eventual secretion of autoantibodies. Future characterization of the specific signaling pathways disrupted in BND cells should provide insight into the intrinsic mechanisms of immune tolerance for B cells and may identify specific pathways that can be therapeutically targeted to treat autoimmune diseases.

DISCUSSION

Mature and naive autoreactive (and thus potentially pathogenic) B cells in the periphery have been shown to account for up to 20% of the circulating B cell pool in healthy human adults (1, 25). The presence of these autoreactive cells begs many but ultimately two important questions: why have they survived selection and how are they tolerized? Focusing on the latter, extensive studies of self-tolerant B cells in transgenic mouse models over the last two decades have revealed the complicated systems of B cell selection used to avoid autoimmunity. B cells expressing transgenic surface Ig that bind DNA or protein autoantigens that do not alter the BCR by receptor editing (2, 3) may be eliminated (clonal deletion) (4). Importantly, and pertinent to this work, many autoreactive cells pass these checkpoints for reasons not well understood and survive to the periphery, but with reduced or altered function so they no longer react to the self-antigens (clonal anergy) (7, 8).

A key advance to understanding and treating human autoimmune disease is to link the numerous fundamental discoveries of the past 20 yr concerning autoreactive B cells in transgenic mice to immune tolerance in humans. Through analyses of a mature naive human B cell population, we have shown that, similar to the classical anti-HEL/HEL model of anergy developed by Goodnow (8), IgD+ B cells with no surface IgM are predominantly autoreactive and are functionally attenuated. The mechanistic connection between anergy and reduced IgM expression is not known and is not a universal phenotype of all anergic B cells (for review see reference 15) but may represent a consequence of constant self-antigen exposure in the early life of the cell (53).

As described, anergy in the BND population is not solely dependent on receptor density (or lack of surface IgM expression), as signaling through IgD alone was also less effective for BND than for naive cells (Fig. 5 & 6). However, it is notable that naive cells responded differently to cross-linking by IgM versus IgD, suggesting that down-regulation of surface IgM could have functional consequences for the BND cells. Though the initial burst of stimulation was similar with either cross-linking reagent, a subsequent plateau of sustained increased calcium levels was maintained after IgM stimulation but was lost after IgD stimulation (Fig. S2 C). Combined stimulation through both IgM and IgD resulted in an additive response, with an initial burst similar to either reagent alone, followed by a plateau of sustained calcium levels similar to the anti-IgM response. Thus, assuming that the anti-IgD and anti-IgM reagents similarly cross-link their respective target epitopes, the maintenance of anergy in BND cells may also be influenced by the lack of surface IgM. The exact mechanism behind the receptor-mediated lack of response in the BND population will need to be further elucidated.

BND cells exhibit a well-characterized naive phenotype in that they are CD44+, CD23+, CD38−, CD95−, CD80−, and CD5−. They were not clonally expanded and had no somatic mutations. Importantly, BND cells can also be distinguished from immature new BM immigrant B cells described in recent reports (1, 32) because the immature cells are CD44− and CD38+ as well as being IgD− and IgM+. BND cells also do not express surrogate light chains (CD179a), distinguishing them from preB cells, editing B cells, or recent bone emigrants from the BM (35, 36). Thus, BND cells appear mature by all measures; however, we cannot rule out the possibility that they have recently transitioned from an immature state. Similarly, although the attenuated signaling of BND cells demonstrated that these cells are anergic, we cannot completely rule out some specialized B cell differentiation similar to B1 or MZ cells in mice because these populations have not been well established in humans. However, based on all analyses to date we propose that BND cells arise from autoreactive naive cells that have matured in the classical B-2 pathway.

Similarly to previous reports of anergy, BND cells show attenuation in Ca2+ response and a decrease in accumulation of phosphotyrosines upon treatment with BCR cross-linkers. However, much like anergic B cells in mice, an active mechanism and exposure to autoantigen appears necessary to maintain anergy because rest in tissue culture media overnight restores BND cell signaling to levels similar to naive cells (Fig. S3). In addition, the function of BND cells can be rescued when treated with the soluble T cell factors Il-4 and CD40L, leading them to proliferate, express CD80 and the proliferation marker CD71, and differentiate into plasmablast-like CD38hiCD27hi cells (Fig. S3). Thus, as in previous reports (52, 54, 55), anergy in the BND population appears transient and reversible if the cells receive appropriate pro-T/B cell signals or if the cells are removed from the autoreactive environment. Importantly, Chang et al. (56) recently found that IgD+IgMlowCD27− B cells that we suspect are BND cells become increased in SLE patients. Unlike healthy people, in SLE patients these cells also displayed evidence of activation such as up-regulated CD80/86 levels. Thus, BND cells may pose a serious danger in the development of acute or chronic autoimmune pathology, especially if T cell tolerance is also breached allowing helper activation of these autoreactive cells. We propose that the BND population may be an important source of precursors for pathological autoantibody-secreting cells activated in lupus or other autoimmune diseases.

In conclusion, we have characterized a population of naturally autoreactive B cells in humans that have become anergic. We can now study the molecular and functional characteristics of this manifestation of anergy and its role in avoiding autoimmunity, or if these cells are not properly controlled, in causing autoimmune disease. Further, studies to elucidate the mechanisms inducing anergy may identify molecular pathways that can be exploited pharmacologically to induce an anergic state in reactive B cells to treat autoimmune diseases or avoid organ rejection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

B cell enrichment, sorting, and FACS analyses.

B lymphocytes were isolated from the buffy coat component from 500 ml of freshly donated peripheral human blood obtained from the Oklahoma Blood Institute (Oklahoma City, OK) according to established National Institutes of Health guidelines and protocols with approval from the Oklahoma Medical research Foundation Institutional Review Board. Lymphocytes were isolated by placement over a Ficoll density gradient to remove RBCs and other leukocytes followed by B cell–specific enrichment by negative magnetic bead selection as described previously (24, 40, 57). Cell sorting was performed by staining the cells with monoclonal antihuman antibodies against CD27-FITC, CD19-PE–Alexa Fluor 610 (Invitrogen), IgM-APC (SouthernBiotech), and IgD-PE (BD). BND and naive B cell populations were resolved as in Fig. 1 using a MoFlo flow cytometer (Dako) in the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation flow core facility. For phenotype profiles, populations were resolved as in Fig. 1 and stained with various antihuman antibodies labeled with either FITC or PE fluorophores (Invitrogen), including monoclonal antibodies against CD38, CD44, CD80, CD71, CD95, CD138, CD5, CD179a, CD23, CD21, and Annexin-V. For analyses of mitochondrial dye retention, MTG FM dye (Invitrogen) was loaded into sorted BND and naive B cell populations at a concentration of 100 nM for 30 min and chased with fresh media as previously described (34). For single-cell PCR, bulk cells of either phenotype were first sorted and then resorted into 96-well PCR plates to ensure purity of single cells (98–99% pure). FACS analysis was performed using flow core facility FACSCalibur, FACSAria, or LSR-II flow cytometers (BD) and software analysis was performed with FlowJo Cytometric software (Tree Star, Inc.).

Sequencing and repertoire analysis.

Cells were sorted into the different populations as indicated above and as previously described (24, 40, 57). V region amplification and sequence analysis was performed as described but, in brief, VH4 and VH3 family specific leader sense primers were paired with antisense primers to particular constant region gene (μ or δ). These primers included the following: VH4 sense primer, 5′-ATGAAACACCTGTGGTTCTT-3′; Cμ antisense primer, 5′-CACGTTCTTTTCTTTGTTGC-3′; and Cδ antisense primer, 5′-GTGTCTGCACCCTGATATGATGG-3′. PCR products were amplified using TA or TOPO-TA cloning kits (Invitrogen), and plasmid purification was performed using the miniprep kit (QIAGEN). Sequencing was done at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation sequencing core. All V regions were analyzed using in house analysis software and the National Center for Biotechnology Information IgBlast server (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/igblast/) or the Immunogenetics server (http://imgt.org/IMGT_vquest/share/textes/).

For VpreB (CD179a) analysis, RNA was extracted from 104–105 freshly sorted BND and naive fractions using RNAWiz (Ambion), followed by One-Step RT-PCR (QIAGEN) RNA to cDNA amplification in 40 repeated cycles of equal RNA amounts, using the following primer sets: VpreB sense, 5′-GAGTCAGAGCTCTGCATGTCTG-3′; VpreB antisense, 5′-GTGAGGCCGGATTGTGGTTCCAAG-3′; actin sense. 5′-TACCACTGGCATCGTGATGGACT-3′; and actin antisense, 5′-TCCTTCTGCATCCTGTCGGCAAT-3′. Direct PCR products were analyzed on 1% agarose gels with TAE buffer.

Production of recombinant monoclonal antibodies from single human B cell.

In order to test the specificity of BND cells, recombinant monoclonal antibodies were produced from the variable region genes of isolated single cells. Using a modified strategy similar to previous reports (1, 25, 36), single B cells were sorted by flow cytometry into 96-well plates, and the variable genes amplified by multiplex single-cell RT-PCR to identify and clone the Ig heavy and light chain genes from a random assortment of cells. These variable genes were then cloned into expression vectors and expressed with IgG constant regions in the 293A human cell line. A total of 95 antibodies from BND cells (n = 17, 21, 30, and 27 by donor) were compared with 87 antibodies from naive B cells (IgD+IgM+CD38−; n = 16, 37, 10, 10, and 14 by donor). Three sets of naive and BND antibodies were matched from individual donors. Each antibody was purified from the serum-free tissue culture media.

ELISA and HEp-2 analyses for autoreactivity.

To screen the expressed antibodies for DNA reactivity or polyreactivity, ELISA microtiter plates (Costar; Corning) were coated with 10 μg/ml of calf thymus ssDNA or dsDNA (Invitrogen), LPS (Sigma-Aldrich), or recombinant human insulin (Fitzgerald). Goat anti–human IgG (γ chain specific) peroxidase conjugate (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) was used to detect binding of the recombinant antibodies followed by development with horseradish peroxidase substrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Absorbencies were measured at OD415 on a microplate reader (MDS Analytical Technologies). Antibody affinities to the various antigens were compared by endpoint regression analyses to predict the absorbencies expected based on the binding curve for four fourfold dilutions of antibody (beginning at 1 μg/ml, 7 nM) against a fixed concentration of antigen. Antibodies with BMAX absorbencies that were above the 95% confidence interval of the low positive control (HN241) and had measured affinities of <7 nM (half-maximal binding at ∼1 μg/ml) were scored as DNA binding. All antibodies were screened for ANA reactivity using the QUANTA Lite ANA ELISA kit (INOVA Diagnostics, Inc.) as per the manufacturer's direction. ANA results were verified on a subset of antibodies by immunofluorescence using commercial HEp-2 slides (Bion Enterprises) as previously described (1, 36) and as per the manufacturer's suggested protocol. HEp-2 slides were analyzed using a fluorescent microscope (Axioplan II; Carl Zeiss, Inc.). All HEp-2 and ANA reactivity were compared with positive control sera from a lupus patient and to nonreactive sera from a healthy blood donor.

Calcium flux.

Fresh human PBMCs from buffy coats were enriched for B cells (see B cell enrichment, sorting, and FACS analysis) and split into four equal fractions of 106 cells for each donor (1): naive (2), BND (3), ionomycin naive (4), and ionomycin BND. Cells were resuspended in preprepared HBSS containing 1 μM Ca2+and 1 μM Mg2+ ions supplemented with 1% BSA and were warmed to 30°C for 10 min. After temperature equilibration, cells were loaded with Fluo-4 AM calcium indicator (Invitrogen) at a final concentration of 5 μM and incubated for 15 min in the dark. Cells were then washed and resuspended in HBSS/BSA containing 2.5 μM Probenecid (Sigma-Aldrich) for an additional 30 min at 30°C. After calcium dye loading, cells were placed on ice and differentially stained for 30 min. The naive fractions, including ionomycin naive, received anti-CD27 PE (Invitrogen) and anti–IgG-APC (BD) antibodies. The BND fractions, including ionomycin BND, received anti-CD27 PE, anti–IgM-APC, and anti–IgG-APC. Cells were also stained with anti–CD3-Bio and streptavidin-PE (Invitrogen) to gate out T cells and other non-B cells that escaped column purification. Non–Fluo-4-loaded B cells from each donor were also simultaneously stained, but with the addition of anti-IgD to evaluate the purity of measured fractions. After staining, cells were washed in HBSS/BSA/Probenecid and placed at 37°C for 10 min. Cells were then placed on a LSRII flow cytometer and gates were drawn for the subpopulations naive and BND. Baselines were read for 30 s, after which the cells were removed and stimulated with indicated amounts of Fab′2 anti-IgM (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and Fab′2 anti-IgD (SouthernBiotech) or Fab′2 anti-IgD alone or Fab′2 anti-κ/λ (SouthernBiotech) antibodies. Calcium curves were read for 5–7 min. In the ionomycin fractions, 5 μl of 1 mg/ml ionomycin/EtOH (Sigma-Aldrich) was added 30 s after baseline reads to control for dye loading and cell activation potential. Kinetic curves for each calcium response were generated using FlowJo software.

PhosFlow analysis.

Human B cells from blood buffy coats were isolated (see B cell enrichment, sorting, and FACS analysis) and split into two pools for sorting, one (pool 1) stained with anti–CD27-FITC and the other (pool 2) with anti–CD27-FITC and anti–IgM-APC. Pool 1 B cells were sorted for CD27-negative cells and represented primarily naive cells. Pool 2 cells, representing the BND cells, were sorted for the IgM−CD27− population. Each pool was then washed and resuspended in RPMI without FCS and preheated to 37°C. The cells were then split into aliquots (105 cells/tube) and incubated for 45 s with polyclonal anti-IgD Fab 2′-FITC (SouthernBiotech) and polyclonal anti-IgM Fab 2′ (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Cells were then immediately fixed with PhosFlow Fix Buffer I (BD) for 10 min at 37°C. Cells were then washed two times in PhosFlow Perm/Wash Buffer I (BD), and stained with anti–pTyr-PE (clone PY20; BD) or antiphosphorylated Src (phosphorylated Tyr 416; Cell Signaling Technology). Cells were simultaneously stained with intracellular anti–CD20-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone H1-FB1; BD) at the amounts suggested by the manufacturer. For the pSrc analysis, Sphero Rainbow Beads (BD) were used at the amounts suggested by the manufacturer to calibrate the FACS machine for direct comparisons from multiple experiments. For a positive control, a separate fraction (105) of each population was incubated for 5 min with 5 μl of the protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor pervanadate/H2O2 (3% 100 mM orthovanadate and 3% H2O2 in dH2O). Populations were resolved using FACS and compared with an untreated control. All computational analysis was performed with FlowJo software.

Statistical analyses.

Graphing and statistical analysis were performed using Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc.) or Excel (Microsoft). For comparisons of antibody autoreactivity between total naive and BND antibodies the χ2 statistic was used. To compare the ANA values generated by the ANA ELISA assays, we used both Student's t tests to compare the means and Mann-Whitney tests to compare the medians. The Student's t tests were done with a Welch's correction because of unequal variances between the naive and BND datasets (determined by the F test). However, although not significantly so, there was a non-Gaussian distribution notable in these datasets and, therefore, we also used the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test to compare the median distributions. Also, because of the non-Gaussian distribution the medians are noted in Fig. 2 rather than the means. PhosFlow analyses of pTyr levels and variable gene repertoire analyses used two-tailed Student's t tests (paired for PhosFlow analyses and heteroscedastic for the repertoire analyses).

Online supplemental material.

Fig. S1 illustrates the frequency of polyreactive antibodies PCR-cloned from the naive and BND cells. Fig. S2 includes graphs of the time course of activation of naive versus BND cells as measured by pTyr accumulation (A), calcium flux induced by anti-κ light chain treatment (B), and an illustration of the qualitative differences in calcium flux comparing cross-linking of naive B cells through the IgM or IgD receptors individually and in combination (C). Fig. S3 illustrates the rescue of a functional state for BND cells by stimulation with cofactors such as CD40L, IL-4, and IL-10 (A-D) or after rest in culture ex vivo, presumably without the self-stimulation (E). Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20080611/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Leni Abraham and Matt Jared for technical assistance in the preparation of recombinant monoclonal antibodies. Also, we thank Arlene Wilson, Zena Peters, and the Oklahoma Blood Institute for providing the blood. In addition, we acknowledge Sheryl Christofferson and the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation sequencing core for all DNA sequencing, and Jacob Bass, Diana Hamilton, and the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation flow core for all flow cytometry. Dr. J. Donald Capra, Judith James, and Dr. Mark Coggeshall were instrumental in reviewing the manuscript and for extensive discussion. Dr. Inaqi Sanz provided helpful suggestions.

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grant P20RR018758-01 (P.C. Wilson).

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Abbreviations used: ANA, antinuclear antibody; BCR, B cell receptor; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; HEL, hen egg lysozyme; MTG, MitoTracker Green; pTyr, phosphorylated tyrosine; SLE; systemic lupus erythematosus; ssDNA, single-stranded DNA; T3, transitional 3.

References

- 1.Wardemann, H., S. Yurasov, A. Schaefer, J.W. Young, E. Meffre, and M.C. Nussenzweig. 2003. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science. 301:1374–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gay, D., T. Saunders, S. Camper, and M. Weigert. 1993. Receptor editing: an approach by autoreactive B cells to escape tolerance. J. Exp. Med. 177:999–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tiegs, S.L., D.M. Russell, and D. Nemazee. 1993. Receptor editing in self-reactive bone marrow B cells. J. Exp. Med. 177:1009–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talmage, D.W. 1957. Allergy and immunology. Annu. Rev. Med. 8:239–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burnet, F.M. 1976. A modification of Jerne's theory of antibody production using the concept of clonal selection. CA Cancer J. Clin. 26:119–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nossal, G.J., and B.L. Pike. 1980. Clonal anergy: persistence in tolerant mice of antigen-binding B lymphocytes incapable of responding to antigen or mitogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 77:1602–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nossal, G.J. 1983. Cellular mechanisms of immunologic tolerance. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1:33–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodnow, C.C. 1996. Balancing immunity and tolerance: deleting and tuning lymphocyte repertoires. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93:2264–2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodnow, C.C., J. Crosbie, S. Adelstein, T.B. Lavoie, S.J. Smith-Gill, R.A. Brink, H. Pritchard-Briscoe, J.S. Wotherspoon, R.H. Loblay, K. Raphael, et al. 1988. Altered immunoglobulin expression and functional silencing of self-reactive B lymphocytes in transgenic mice. Nature. 334:676–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodnow, C.C., J. Crosbie, H. Jorgensen, R.A. Brink, and A. Basten. 1989. Induction of self-tolerance in mature peripheral B lymphocytes. Nature. 342:385–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooke, M.P., A.W. Heath, K.M. Shokat, Y. Zeng, F.D. Finkelman, P.S. Linsley, M. Howard, and C.C. Goodnow. 1994. Immunoglobulin signal transduction guides the specificity of B cell–T cell interactions and is blocked in tolerant self-reactive B cells. J. Exp. Med. 179:425–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartley, S.B., J. Crosbie, R. Brink, A.B. Kantor, A. Basten, and C.C. Goodnow. 1991. Elimination from peripheral lymphoid tissues of self-reactive B lymphocytes recognizing membrane-bound antigens. Nature. 353:765–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merrell, K.T., R.J. Benschop, S.B. Gauld, K. Aviszus, D. Decote-Ricardo, L.J. Wysocki, and J.C. Cambier. 2006. Identification of anergic B cells within a wild-type repertoire. Immunity. 25:953–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teague, B.N., Y. Pan, P.A. Mudd, B. Nakken, Q. Zhang, P. Szodoray, X. Kim-Howard, P.C. Wilson, and A.D. Farris. 2007. Cutting edge: Transitional T3 B cells do not give rise to mature B cells, have undergone selection, and are reduced in murine lupus. J. Immunol. 178:7511–7515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cambier, J.C., S.B. Gauld, K.T. Merrell, and B.J. Vilen. 2007. B-cell anergy: from transgenic models to naturally occurring anergic B cells? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7:633–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Acevedo-Suarez, C.A., C. Hulbert, E.J. Woodward, and J.W. Thomas. 2005. Uncoupling of anergy from developmental arrest in anti-insulin B cells supports the development of autoimmune diabetes. J. Immunol. 174:827–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rojas, M., C. Hulbert, and J.W. Thomas. 2001. Anergy and not clonal ignorance determines the fate of B cells that recognize a physiological autoantigen. J. Immunol. 166:3194–3200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erikson, J., M.Z. Radic, S.A. Camper, R.R. Hardy, C. Carmack, and M. Weigert. 1991. Expression of anti-DNA immunoglobulin transgenes in non-autoimmune mice. Nature. 349:331–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roark, J.H., A. Bui, K.A. Nguyen, L. Mandik, and J. Erikson. 1997. Persistence of functionally compromised anti-double-stranded DNA B cells in the periphery of non-autoimmune mice. Int. Immunol. 9:1615–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen, K.A., L. Mandik, A. Bui, J. Kavaler, A. Norvell, J.G. Monroe, J.H. Roark, and J. Erikson. 1997. Characterization of anti-single-stranded DNA B cells in a non-autoimmune background. J. Immunol. 159:2633–2644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benschop, R.J., K. Aviszus, X. Zhang, T. Manser, J.C. Cambier, and L.J. Wysocki. 2001. Activation and anergy in bone marrow B cells of a novel immunoglobulin transgenic mouse that is both hapten specific and autoreactive. Immunity. 14:33–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borrero, M., and S.H. Clarke. 2002. Low-affinity anti-Smith antigen B cells are regulated by anergy as opposed to developmental arrest or differentiation to B-1. J. Immunol. 168:13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pugh-Bernard, A.E., G.J. Silverman, A.J. Cappione, M.E. Villano, D.H. Ryan, R.A. Insel, and I. Sanz. 2001. Regulation of inherently autoreactive VH4-34 B cells in the maintenance of human B cell tolerance. J. Clin. Invest. 108:1061–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng, N.Y., K. Wilson, X. Wang, A. Boston, G. Kolar, S.M. Jackson, Y.J. Liu, V. Pascual, J.D. Capra, and P.C. Wilson. 2004. Human immunoglobulin selection associated with class switch and possible tolerogenic origins for C delta class-switched B cells. J. Clin. Invest. 113:1188–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koelsch, K., N.Y. Zheng, Q. Zhang, A. Duty, C. Helms, M.D. Mathias, M. Jared, K. Smith, J.D. Capra, and P.C. Wilson. 2007. Mature B cells class switched to IgD are autoreactive in healthy individuals. J. Clin. Invest. 117:1558–1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cappione, A. III, J.H. Anolik, A. Pugh-Bernard, J. Barnard, P. Dutcher, G. Silverman, and I. Sanz. 2005. Germinal center exclusion of autoreactive B cells is defective in human systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Clin. Invest. 115:3205–3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wrammert, J., K. Smith, J. Miller, T. Langley, K. Kokko, C. Larsen, N.Y. Zheng, I. Mays, C. Helms, J. James, et al. 2008. Rapid cloning of high affinity human monoclonal antibodies against influenza virus. Nature. 453:667–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koffler, D., R.I. Carr, V. Agnello, T. Fiezi, and H.G. Kunkel. 1969. Antibodies to polynucleotides: distribution in human serums. Science. 166:1648–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stollar, B.D., G. Zon, and R.W. Pastor. 1986. A recognition site on synthetic helical oligonucleotides for monoclonal anti-native DNA autoantibody. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 83:4469–4473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radic, M.Z., and M. Weigert. 1995. Origins of anti-DNA antibodies and their implications for B-cell tolerance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 764:384–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bradwell, A.R., R.P. Stokes, and G.D. Johnson. 1995. Atlas of HEp-2 patterns. The Binding Site LTD, Birmingham, England. 118 pp.

- 32.Sims, G.P., R. Ettinger, Y. Shirota, C.H. Yarboro, G.G. Illei, and P.E. Lipsky. 2005. Identification and characterization of circulating human transitional B cells. Blood. 105:4390–4398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tedder, T.F., J. Tuscano, S. Sato, and J.H. Kehrl. 1997. CD22, a B lymphocyte-specific adhesion molecule that regulates antigen receptor signaling. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:481–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wirths, S., and A. Lanzavecchia. 2005. ABCB1 transporter discriminates human resting naive B cells from cycling transitional and memory B cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 35:3433–3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meffre, E., E. Davis, C. Schiff, C. Cunningham-Rundles, L.B. Ivashkiv, L.M. Staudt, J.W. Young, and M.C. Nussenzweig. 2000. Circulating human B cells that express surrogate light chains and edited receptors. Nat. Immunol. 1:207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meffre, E., A. Schaefer, H. Wardemann, P. Wilson, E. Davis, and M.C. Nussenzweig. 2004. Surrogate light chain expressing human peripheral B cells produce self-reactive antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 199:145–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carsetti, R., M.M. Rosado, and H. Wardmann. 2004. Peripheral development of B cells in mouse and man. Immunol. Rev. 197:179–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bikah, G., J. Carey, J.R. Ciallella, A. Tarakhovsky, and S. Bondada. 1996. CD5-mediated negative regulation of antigen receptor-induced growth signals in B-1 B cells. Science. 274:1906–1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller, R.A., and J. Gralow. 1984. The induction of Leu-1 antigen expression in human malignant and normal B cells by phorbol myristic acetate (PMA). J. Immunol. 133:3408–3414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson, P.C., O. de Bouteiller, Y.J. Liu, K. Potter, J. Banchereau, J.D. Capra, and V. Pascual. 1998. Somatic hypermutation introduces insertions and deletions into immunoglobulin V genes. J. Exp. Med. 187:59–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson, P.C., K. Wilson, Y.J. Liu, J. Banchereau, V. Pascual, and J.D. Capra. 2000. Receptor revision of immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region genes in normal human B lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 191:1881–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng, N.Y., K. Wilson, M. Jared, and P.C. Wilson. 2005. Intricate targeting of immunoglobulin somatic hypermutation maximizes the efficiency of affinity maturation. J. Exp. Med. 201:1467–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu, Y.J., O. de Bouteiller, C. Arpin, F. Briere, L. Galibert, S. Ho, H. Martinez-Valdez, J. Banchereau, and S. Lebecque. 1996. Normal human IgD+IgM- germinal center B cells can express up to 80 mutations in the variable region of their IgD transcripts. Immunity. 4:603–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arpin, C., O. de Bouteiller, D. Razanajaona, I. Fugier-Vivier, F. Briere, J. Banchereau, S. Lebecque, and Y.J. Liu. 1998. The normal counterpart of IgD myeloma cells in germinal center displays extensively mutated IgVH gene, Cμ-Cδ switch, and λ light chain expression. J. Exp. Med. 187:1169–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ichiyoshi, Y., and P. Casali. 1994. Analysis of the structural correlates for antibody polyreactivity by multiple reassortments of chimeric human immunoglobulin heavy and light chain V segments. J. Exp. Med. 180:885–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klonowski, K.D., L.L. Primiano, and M. Monestier. 1999. Atypical VH-D-JH rearrangements in newborn autoimmune MRL mice. J. Immunol. 162:1566–1572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Link, J.M., and H.W.J. Schroeder. 2002. Clues to the etiology of autoimmune diseases through analysis of immunoglobulin genes. Arthritis Res. 4:80–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Healy, J.I., R.E. Dolmetsch, L.A. Timmerman, J.G. Cyster, M.L. Thomas, G.R. Crabtree, R.S. Lewis, and C.C. Goodnow. 1997. Different nuclear signals are activated by the B cell receptor during positive versus negative signaling. Immunity. 6:419–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dolmetsch, R.E., R.S. Lewis, C.C. Goodnow, and J.I. Healy. 1997. Differential activation of transcription factors induced by Ca2+ response amplitude and duration. Nature. 386:855–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vilen, B.J., K.M. Burke, M. Sleater, and J.C. Cambier. 2002. Transmodulation of BCR signaling by transduction-incompetent antigen receptors: implications for impaired signaling in anergic B cells. J. Immunol. 168:4344–4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weintraub, B.C., J.E. Jun, A.C. Bishop, K.M. Shokat, M.L. Thomas, and C.C. Goodnow. 2000. Entry of B cell receptor into signaling domains is inhibited in tolerant B cells. J. Exp. Med. 191:1443–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gauld, S.B., R.J. Benschop, K.T. Merrell, and J.C. Cambier. 2005. Maintenance of B cell anergy requires constant antigen receptor occupancy and signaling. Nat. Immunol. 6:1160–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raff, M.C., J.J. Owen, M.D. Cooper, A.R. Lawton III, M. Megson, and W.E. Gathings. 1975. Differences in susceptibility of mature and immature mouse B lymphocytes to anti-immunoglobulin-induced immunoglobulin suppression in vitro. Possible implications for B-cell tolerance to self. J. Exp. Med. 142:1052–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goodnow, C.C., R. Brink, and E. Adams. 1991. Breakdown of self-tolerance in anergic B lymphocytes. Nature. 352:532–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eris, J.M., A. Basten, R. Brink, K. Doherty, M.R. Kehry, and P.D. Hodgkin. 1994. Anergic self-reactive B cells present self antigen and respond normally to CD40-dependent T-cell signals but are defective in antigen-receptor-mediated functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:4392–4396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chang, N.H., T. McKenzie, G. Bonventi, C. Landolt-Marticorena, P.R. Fortin, D. Gladman, M. Urowitz, and J.E. Wither. 2008. Expanded population of activated antigen-engaged cells within the naive B cell compartment of patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J. Immunol. 180:1276–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pascual, V., Y.J. Liu, A. Magalski, O. de Bouteiller, J. Banchereau, and J.D. Capra. 1994. Analysis of somatic mutation in five B cell subsets of human tonsil. J. Exp. Med. 180:329–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.