Abstract

We report here on the diffusion-weighted imaging of unusual white matter lesions in a case of Menkes disease. On the initial MR imaging, the white matter lesions were localized in the deep periventricular white matter in the absence of diffuse cortical atrophy. The lesion showed diffuse high signal on the diffusion-weighted images and diffuse progression and persistent hyperintensity on the follow up imaging. Our case suggests that the white matter lesion may precede diffuse cortical atrophy in a patient with Menkes disease.

Keywords: Brain, Magnetic Resonance (MR), Menkes disease, White Matter, Diffusion study

Menkes disease is an X-linked disorder that's caused by impaired intracellular transport of copper (1, 2). The clinical manifestations include failure to thrive, mental retardation, seizure and characteristic hypopigmented "kinky hair", and all this could be explained by dysfunction of the copper dependent enzymes (2). The previous neuroimaging reports on this disorder have been described diffuse brain atrophy, subdural effusion or hematoma, white matter changes and vascular tortuosity (3-6). However, the diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) of the cerebral lesions in this disease has rarely reported on and the previous report has been limited to the deep gray matter lesion (7).

We describe here the DWI findings of unusual and progressive white matter lesions in a case of Menkes disease.

CASE REPORT

A 10-month-old male was admitted with a few days history of fever. He was delivered at 38 weeks gestation following an unremarkable pregnancy and labor, and his birth weight was 2,960 g. He had a sister and there was no significant familial history. A cephalhmatoma over the parietooccipital region was detected at delivery. A skull radiograph showed numerous Wormian bones in the lambdoid suture. At two months of age, he underwent inguinal herniorrhaphy under the diagnosis of bilateral inguinal hernia. He had a history of recurrent pneumonia and urinary tract infection. The retrograde vesicogram demonstrated the presence of multiple bladder diverticula.

On presentation, he was found to be very delayed in growth and development. His growth parameters were less than the 3rd percentile (weight: 7,500 g and length: 73.7 cm). He had pale skin and very sparse hair, which was lightly pigmented and curly. Microscopic examination of the hair showed fragile and brittle filaments curled up in their own axis, which is called in pili torti. Neurologic examination revealed diffuse hypotonia with poor head and trunk support. He blinked to bright light stimulation, but he did not fix or follow. The deep tendon reflexes were hyperreflexic bilaterally, with clonus at the ankles. The Barbinski responses were bilateral extension. The serum copper level was 27µg/dL (normal = 70-130µg/dL) and the ceruloplasmin was 9.07µg/dL (normal = 20-60µg/dL). The clinical and biochemical data confirmed the diagnosis of Menkes disease.

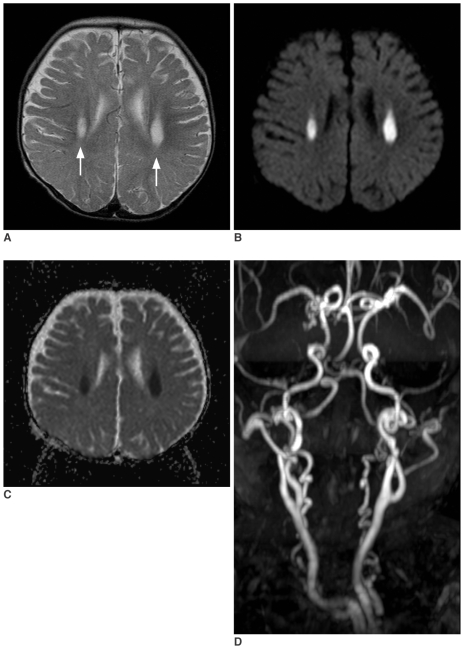

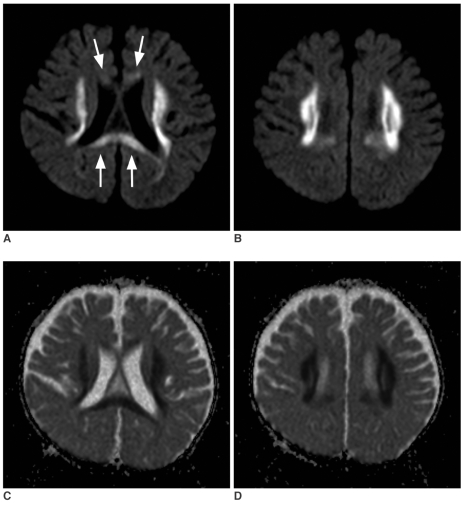

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging was obtained using a 1.5T clinical scanner (Sonata, Siemens, Germany). The imaging protocol included DWI, axial pre- and post T1-weighted and T2-weighted spin echo images, and fluid attenuated inversion recovery images. On the initial MR examination, the T2-weighted images demonstrated symmetric hyperintense lesions in both deep cerebral white matters (Fig. 1A). There was mild atrophy of the cerebellum and brainstem, yet atrophy of the cerebral hemispheres was not prominent. DWI demonstrated high signal intensity of the lesions, and their apparent diffusion coefficients (ADCs) were decreased on the ADC maps (Figs. 1B, C). Three dimensional MR angiography (Fig. 1D) showed markedly tortuous intracranial and extracranial vessels, which are characteristic of Menkes disease. The follow up MR imaging at 13 months of age showed marked progression of white matter lesions without definite progression of the cortical atrophy. The lesions extended to the deep white matter and corpus callosum (Figs. 2A, B). The extended lesions also showed high signal intensity on DWI and decreased ADC, similar to those of the initial lesions (Figs. 2C, D).

Fig. 1.

Initial MR images obtained at age of 10 months.

A. T2-wieghted axial image (TR/TE = 4700/104 msec, 5 mm thickness) demonstrates symmetric hyperintense lesion in both deep periventricular white matters (arrows).

B. Diffusion weighted image (TR/TE = 3500/92, b maximum = 1000 s/mm2, three directions, 5 mm thickness) shows the bright signal intensity of the lesion.

C. On the apparent diffusion coefficient map, the lesion shows diffuse low signal intensities, suggesting restricted diffusion.

D. Three dimensional MR angiography shows markedly tortuous intracranial and extracranial vessels, which are characteristics of Menkes disease.

Fig. 2.

Follow up diffusion study obtained at the age of 13 months.

A, B. Consecutive diffusion-weighted images (TR/TE = 3500/95, b maximum = 1000 s/mm2) demonstrate marked extension of the white matter lesions to the adjacent white matter. The lesion also involves the corpus callosum (arrows). Note there is no definite progression of cortical atrophy.

C, D. Apparent diffusion coefficient maps of the lesion show diffusely decreased apparent diffusion coefficient, similar to that of the initial lesions (Fig. 1C).

DISCUSSION

Menkes disease is an X-linked recessive disorder, and it is due to an inborn error of copper metabolism. The cause of Menkes disease has been isolated to a genetic defect in copper-transporting adenosine triphosphatase, and this results in low levels of intracellular copper (1, 2). It is characterized clinically by failure to thrive, retarded mental and motor development, clonic seizure and peculiarly coarse, sparse and colorless scalp hair. These clinical findings can be explained by a dysfunction of the copper-dependent enzymes (2). Significant secondary mitochondrial dysfunction due to cytochrome c oxidase deficient activity can explain some of the metabolic features, and deficient lysyl oxidase and superoxide dismutase may explain some of the structural and vascular features.

The CT and MR imaging reports on Menkes disease have shown severe neuronal loss that's manifested by diffuse cerebellar and cortical atrophy, white matter lesions and subdural hematoma or effusions (3-5). The white matter lesions of our case showed unusual features: the lesions were symmetric and localized in the deep periventricular white matter on the initial MR imaging (Fig. 1), and the lesions showed marked progression with the absence of diffuse cortical atrophy on the follow-up imaging. This pattern of involvement was unusual and has never before been reported. The white matter lesion in the absence of cortical atrophy is thought to be unusual because the white matter lesions in Menkes disease have been explained by secondary degeneration and demyelination followed by extensive degeneration of the gray matter (4). In addition, our case had symmetric lesions localized in the deep white matter. Although localized white matter lesions have been previously reported on, those lesions were usually asymmetric, and they involved lobar white matter rather than deep white matter (4, 8, 9).

Diffusion-weighted imaging of the cerebral lesion in Menkes disease has been reported and this has been limited to the gray matter lesion (7). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report about the DWI of the white matter lesion in a Menkes disease patient. The white matter lesions demonstrated restricted diffusion, that is, diffuse high signals on DWI and decreased ADC, and this was persistent on the follow-up imaging (Figs. 1, 2). The pathogenesis of these findings is uncertain, but it may be metabolic and related to a deficiency in a mitochondrial copper containing enzyme (2). Transient ischemic changes or demyelination in the brain are often observed in the patients with mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS), in which these changes are caused by a decrease in cytochrome coxidase activity (10). Cytochorme c oxidase activity is also known to be decreased in the brain of patients with Menkes disease (2). Decreased activity of superoxide mutase, an enzyme responsible for the regulation and sequestration of oxygen free radicals, lowers protection against oxidative stress and it may lead to a cytotoxic effect and cell damage (2). Tortuous and irregular vessels might produce erratic and turbulent blood and so predispose the sufferer to diffuse white matter ischemia (7).

In summary, we have described unusual, progressive white matter lesion in a patent with Menkes disease. DWI demonstrated the diffuse high signal intensity and restricted diffusion of the lesion. Our case might suggest that the white matter lesion could precede diffuse cortical atrophy in those patients with Menkes disease.

References

- 1.Menkes JH, Alter M, Steigleder GK, Weakley DR, Sung JH. A sex-linked recessive disorder with retardation of growth, peculiar hair, and focal cerebral and cerebellar degeneration. Pediatrics. 1962;29:764–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaler SG. Menkes disease. Adv Pediatr. 1994;41:263–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faerber EN, Grover WD, DeFilipp GJ, Capitanio MA, Liu TH, Swartz JD. Cerebral MR of Menkes kinky-hair disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1989;10:190–192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leventer RJ, Kornberg AJ, Phelan EM, Kean MJ. Early magnetic resonance imaging findings in Menkes' disease. J Child Neurol. 1997;12:222–224. doi: 10.1177/088307389701200314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi S, Ishii K, Matsumoto K, Higano S, Ishibashi T, Zuguchi M, et al. Cranial MRI and MR angiography in Menkes' syndrome. Neuroradiology. 1993;35:556–558. doi: 10.1007/BF00588724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim OH, Suh JH. Intracranial and extracranial MR angiography in Menkes disease. Pediatr Radiol. 1997;27:782–784. doi: 10.1007/s002470050231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsich GE, Robertson RL, Irons M, Soul JS, du Plessis AJ. Cerebral infarction in Menkes' disease. Pediatr Neurol. 2000;23:425–428. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(00)00207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blaser SI, Berns DH, Ross JS, Lanska MJ, Weissman BM. Serial MR studies in Menkes disease. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1989;13:113–115. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198901000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozawa H, Kodama H, Murata Y, Takashima S, Noma S. Transient temporal lobe changes and a novel mutation in a patient with Menkes disease. Pediatr Int. 2001;43:437–440. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2001.01402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valanne L, Ketonen L, Majander A, Suomalainen A, Pihko H. Neuroradiologic findings in children with mitochondrial disorders. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:369–377. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]