Abstract

We report here on an uncommon case of peliosis hepatis with hemorrhagic necrosis that was complicated by massive intrahepatic bleeding and rupture, and treated by emergent right lobectomy. We demonstrate the imaging findings, with emphasis on the triphasic, contrast-enhanced multidetector CT findings, as well as reporting the clinical outcome in a case of peliosis hepatis with fatal hemorrhage.

Keywords: Liver, CT; Liver, diseases; Peliosis hepatis; Hemorrhage

Peliosis hepatis is an uncommon condition characterized by blood-filled cystic cavities in the liver (1). The clinical presentation is quite variable from an asymptomatic presentation to hepatic failure, portal hypertension or fatal intraabdominal hemorrhage. The exact incidence of intrahepatic or intraperitoneal hemorrhage by liver rupture has not been determined in the literature and these complications have been demonstrated only in the form of about 20 case reports (2, 3).

On angiography, peliosis hepatis can be suspected by multiple small contrast accumulations that become distinct during the parenchymal phase and are persistent during the venous phase (4). There have been reports about the imaging findings of peliosis hepatis on ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); however, the features are quite variable and nonspecific (2, 3, 5-9).

Examinations using multidetector CT (MDCT) scanners, which provide thin-section, contrast-enhanced dynamic images, are increasing nowadays. Thus, this entity has a better chance to be incidentally encountered and to be a diagnostic challenge to the radiologists. Especially, in a case complicated by hemorrhage, the early correct imaging diagnosis is essential for guiding prompt and proper management. However, there are a few reports demonstrating the CT findings in cases with hepatic rupture caused by peliosis hepatis (2, 3), and there is no report about the contrast-enhanced dynamic MDCT features.

In this report, we present a case of peliosis hepatis with hemorrhagic necrosis that was complicated by massive intrahepatic bleeding and rupture. We demonstrate the imaging findings with emphasis on the contrast-enhanced dynamic MDCT features as well as the clinical outcome after treatment.

CASE REPORT

A 42-year-old female visited our emergency room (ER) with complaints of acute, diffuse abdominal pain. She had been treated for three days at a local clinic because of fever and right upper quadrant pain. She had no significant medical or medication history. The laboratory findings showed mild leukocytosis (11.2×103 cells/µL) and an elevated C-reactive protein level, and the hepatic parameters were markedly elevated. The serum hemoglobin level was 7.8 g/dL and she was transfused with whole blood.

The ultrasound examination performed on an ATL machine (HDI 5000, Bothell, WA) revealed a huge and heterogeneous lesion at the subcapsular area of the right hepatic lobe and also a perihepatic fluid collection (Fig. 1). The differential diagnosis was hepatic subcapsular abscess or a hepatic mass such as a cavernous hemangioma draping over the liver. MDCT was performed with a 4-channel scanner (Volume zoom; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with using following parameters; 120 kVp, 165 mAs, 3 mm collimation and a 1.5 mm reconstruction interval for the arterial and portal venous phases, and 7 mm collimation and a 5 mm reconstruction interval for the unenhanced and equilibrium phase images. After injection of 120 ml of non-ionic contrast material, the arterial phase images were obtained with a 40 sec delay, and 80 sec and 3 min delays were used for the portal venous and delayed phases, respectively. Coronal multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) was done at each phase.

Fig. 1.

Abdominal ultrasonogram shows a huge and heterogeneous lesion at the subcapsular area of the right hepatic lobe (arrows) and also a perihepatic fluid collection.

On the unenhanced images, about a 9 cm-sized, low density, irregular-shaped lesion was seen at the right hepatic dome. Most of the lesion was not enhanced, but multiple, irregular and linear, septa-like densities were demonstrated which were of isoattenuation to the adjacent normal parenchyma on all phases (Fig. 2). The unenhanced images also revealed a huge, heterogeneous and mainly hyperdense lesion occupying the entire right subcapsular area, and this was suggestive of acute hematoma (Fig. 3A). On the contrast-enhanced triphasic images, most of the lesion was not enhanced, except for multiple small enhancing foci that were gradually enlarged and isodense on all phases as compared with the liver parenchyma. The margin of the lesion at the junction with the normal parenchyma was shaggy and irregular. Another 1 cm-sized lesion was seen at the right hepatic lobe, and the lesion was of low density on the arterial phase; it showed peripheral isodense enhancement on the portal venous phase and it became totally isodense or slightly hyperdense on the delayed phase (Fig. 3). The MPR images helped us view all the above-mentioned findings at a glance (Fig. 4).

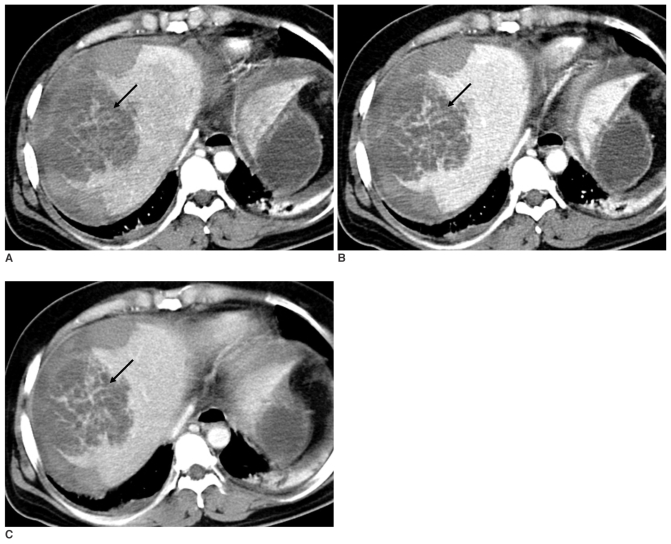

Fig. 2.

The triphasic, contrast-enhanced CT scan shows irregular and linear, septa-like densities (arrow) in the unenhancing, hypodense mass-like lesion at segment 8, which are isodense to liver parenchyma on the arterial (A), portal venous (B) and delayed (C) phases.

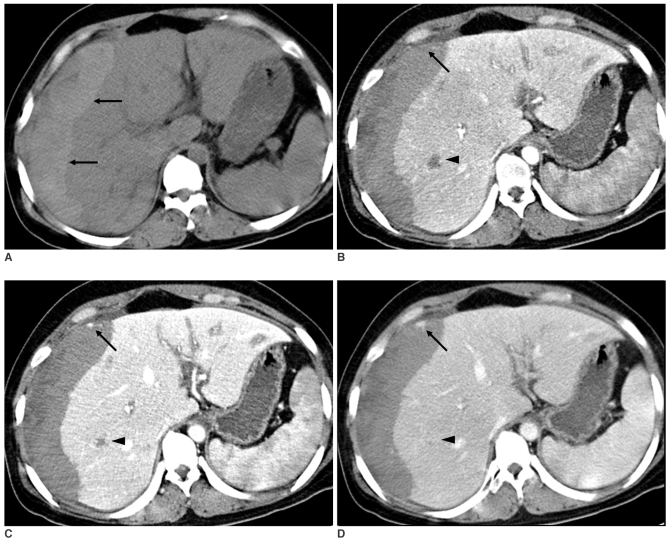

Fig. 3.

The unenhanced CT scan shows massive acute hematoma in the right subcapsular area (A, arrows). The triphasic, contrast-enhanced CT scan shows small enhancing focus (arrow) on the background of hemorrhage, which is isodense to liver parenchyma on the arterial (B), portal (C) and delayed (D) phases. Note a small lesion in the right lobe (arrowhead) that is hypodense on the arterial phase (B), peripherally enhanced on the portal venous phase (C), and it becomes totally isodense or slightly hyperdense on the delayed phase (D).

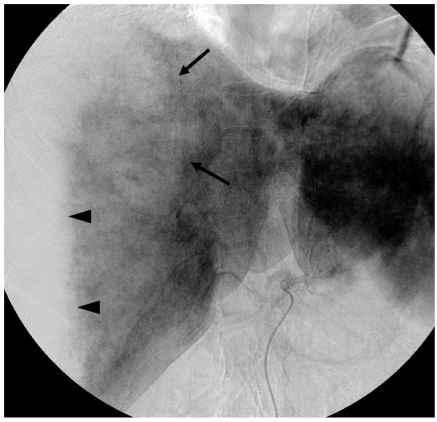

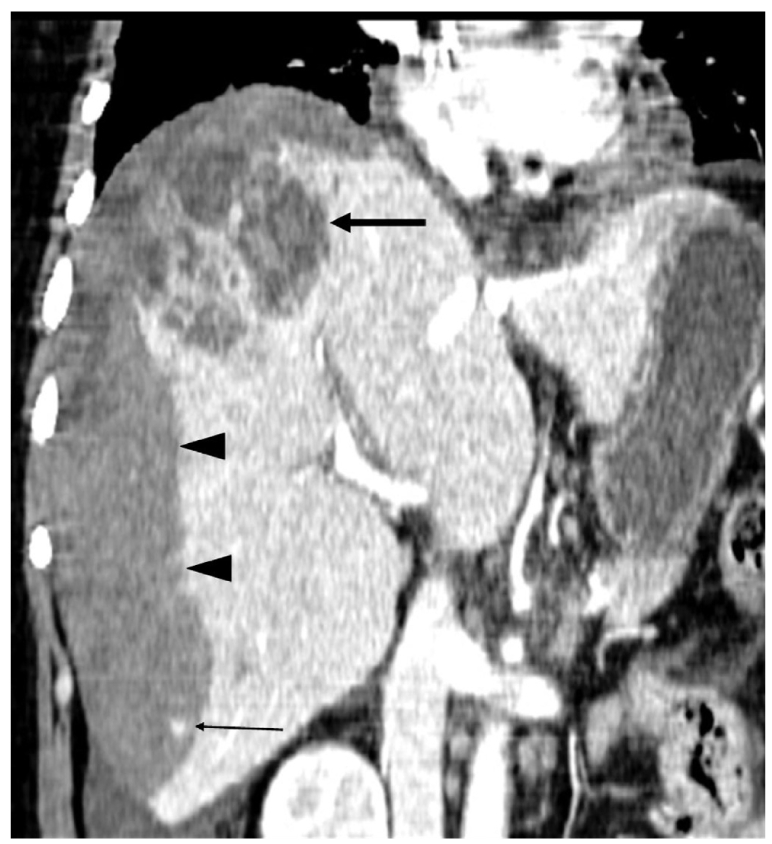

Fig. 4.

Coronal reconstruction image shows a necrotic mass-like lesion at the dome (arrow) and a small enhancing focus in the hematoma (thin arrow) as well as massive hemorrhage that occupies the entire right subcapsular area (arrowheads).

Angiography was performed for vascular embolization under the impression of rupture of hepatic tumor such as hepatic adenoma after the CT scan. The angiogram revealed a huge hypovascular area that conformed to the entire right subcapsular portion, which was compatible with hematoma, and an irregular parenchymal defect was seen in the hepatic dome without any feeding vessels, definite contrast accumulations or vascular malformations (Fig. 5). So, interventional procedures were not done and the diagnosis was not changed even after angiography.

Fig. 5.

Celiac angiogram shows an irregular parenchymal defect in the hepatic dome (arrows) and a huge hypovascular area that is displacing the right lobe: this suggests subcapsular hematoma (arrowheads).

The patient was given supportive care after angiography, but she suffered cardiac arrest that necessitated cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Finally, emergency right lobectomy was performed about 24 hours after her ER admission. At laparotomy, most of the portion of the right hepatic lobe was replaced by hematoma, and some inflammatory patches were present on the liver surface. A mass-like lesion was noted at segment 8, which had ruptured, and this resulted in a large amount of blood and necrotic material in the peritoneal cavity. On microscopic examination, the lesion was diagnosed as peliosis hepatis which was a blood filled cavity lined by fibrinous material and hepatocytes (Fig. 6). She was discharged about one month after surgery and has lived healthy without any symptoms or abnormal findings on follow-up CT examinations two years later.

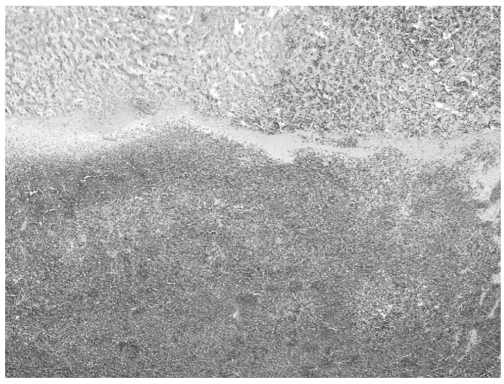

Fig. 6.

A photomicrograph reveals a blood-filled cavity lined by fibrinous materials and hepatocytes (H & E stain, ×40).

DISCUSSION

The etiology of peliosis hepatis is unknown; however, a number of causes have been postulated and its pathogenesis remains uncertain (10). Peliosis hepatis has been considered as a rare, incidental autopsy finding that's associated with chronic wasting diseases such as tuberculosis and malignancies. It has been associated with renal transplantation, hematologic disorders and infections such as pulmonary tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus. It has also been reported in patients treated with long-term with anabolic steroids, oral contraceptives, hormones or azathioprine (7). In 25-50% of the cases, no associated condition has been identified, the same as in this case (9).

The clinical presentations of patients with peliosis hepatis are variable. They range from asymptomatic to signs of acute infection and even to hepatic failure and intraabdominal hemorrhage. The patients with complicated fatal hemorrhage probably could have been successfully managed by surgical intervention such as partial hepatic resection or hepatic dearterialization, interventional selective hepatic arterial embolization or liver transplantation and adequate supportive care. Although there were some cases in which the patients died after treatment, the other patients who had survived the disease became healthy without any symptoms (2, 3).

Two morphologic patterns of hepatic peliosis were described by Yanoff and Rawson (10). In the phlebectatic type, the blood-filled spaces are lined with endothelium and they are based on by aneurismal dilatation of the central vein; in the parenchymal type, the spaces have no endothelial lining and they usually are associated with hemorrhagic parenchymal necrosis. Senf as reviewed by Zak (1) considered the two morphological patterns as one process initiated by focal necrosis of the liver parenchyma, which transforms into an area of hemorrhage (the parenchymal pattern). This pattern may progress to formation of fibrous walls and an endothelial lining around the hemorrhage (the phlebectatic type), or heal by fibrin deposition, thrombosis and sclerosis of the vascular spaces.

When reviewing the reports that have described the radiologic findings of peliosis hepatis with using various modalities, including angiography, US, CT and MRI, there were no specific features suggestive of peliosis hepatis. The imaging findings were so variable, depending on the histopathologic findings, including lesion size, the extent of communication with the sinusoids and the presence of thrombosis or hemorrhage within a lesion (8).

As for the angiographic appearances of peliosis hepatis, multiple small contrast accumulations or puddles have been described (2-4). Yet such findings were not shown in the present case because the major portion of the affected area was necrotized and replaced by hemorrhage, which attributed to delayed diagnosis and was the reason why radiologic intervention was not performed. Hypoechoic or hyperechoic nodule or diffuse heterogeneous hepatic echotexture have been reported as US findings (5, 6). In our case, only a heterogeneous subcapsular mass-like lesion was noted and interpreted as abscess that correlated to the signs of clinical infection, but in retrospect, we could have found a hyperechoic nodule at segment 8, which was considered to be a lesion that was demonstrated on CT scan. The MRI findings for peliosis hepatis largely depend on the age or status of hemorrhage, with hypo-, iso-, or hyperintensities on T1-weighted images and hyperintensity on T2-weighted images. The contrast enhancement may be usually slow and late (7-9).

On the unenhanced CT, the lesions are usually of low density, but the attenuation will vary with regard to the age of the lesion, as well as the presence of hemorrhage. They have been reported to usually become isodense or slightly hyperdense at the late venous or equilibrium phase with or without a central unenhancing portion, although with the presence of hemorrhage they may show little enhancement (8). Gouya et al. (7) reported a unique pattern of the early and high enhancement with centrifugal progression on triphasic CT; Kleinig et al. (5) reported a small lesion of which density was high on the arterial and portal venous phases, respectively. In our case, a small lesion in the right lobe showed gradual and centripetal enhancement, and the attenuation was nearly the same as that of parenchyma. We suggest that this feature might be a more usual dynamic enhancement pattern on triphasic-enhanced CT, including the arterial, portal and delayed phases, in the lesions without necrotic change or other complications.

Until now, there has been no report describing the contrast-enhanced dynamic CT features in a case with peliosis hepatis with hemorrhagic necrosis, intrahepatic hemorrhage and rupture. Here we demonstrated several features that can provide radiologists with clues suggesting that the cause of extensive subcapsular hemorrhage is a peliosis hepatis, or that a low density, mass-like lesion may be peliosis hepatis with hemorrhagic necrosis. The first clue is multiple small enhancing foci that are located at the boundary of the acute subcapsular hemorrhage and enlarge according to the passage of time. These densities are isodense to the parenchyma on all phase images, with the highest Hounsfield number on the portal venous phase. This finding is considered to correspond to multiple small accumulations of contrast material on angiography, and this finding was first described by Pliskin (4). In our case, the densities were not visualized on US or angiography and it is now clear that visualization of these small foci is attributed to the excellent spatial resolution of MDCT. The second clue is a shaggy border of parenchyma with hemorrhage, which may give an impression that the subcapsular high density is not just simple hemorrhage, but it is associated with peliosis hepatis. The last clue is multiple, irregular and linear, septa-like structures inside a low density mass, which show isoattenuation compared to the adjacent parenchyma on all phases. The structures may suggest uncomplicated peliotic parenchyma in contrast to the surrounding, hemorrhagic necrosis.

The differential diagnosis of peliosis hepatis may be different according to the presented imaging findings. In the case of hypervascular, well-enhancing lesions, the differential diagnosis includes benign hepatic tumors such as hepatic hemangioma, adenoma, focal nodular hyperplasia, hemangiosarcoma, hypervascular metastasis or arteriovenous malformation. A hypovascular lesion must be differentiated from abscess, hypovascular metastasis or other necrotic masses. Yet the addition of the delayed phase imaging can help rule out abscess or metastasis via the finding of disappearance or a decrease in size of the lesion, as compared to the arterial or portal phase images.

In conclusion, familiarity with the imaging characteristics and the possible clinical manifestations of peliosis hepatis with or without complications can help radiologists make the early and correct diagnosis. Thin-section, triphasic-enhanced MDCT can provide quite useful and conclusive information for the diagnosis of peliosis hepatis.

Footnotes

This paper was supported by Wonkwang University in 2004.

References

- 1.Zak FG. Peliosis hepatis. Am J Pathol. 1950;26:1–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang SJ, Ruggles S, Vade A, Newman BM, Borge MA. Hepatic rupture caused by peliosis hepatis. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1456–1459. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.26397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fidelman N, LaBerge JM, Kerlan RK., Jr SCVIR 2002 film panel case 4: massive intraperitoneal hemorrhage caused by peliosis hepatis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13:542–545. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61539-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pliskin M. Peliosis hepatis. Radiology. 1975;114:29–30. doi: 10.1148/114.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleinig P, Davies RP, Maddern G, Kew J. Peliosis hepatis: central "fast surge" ultrasound enhancement and multislice CT appearances. Clin Radiol. 2003;58:995–998. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(03)00141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savastano S, San Bortolo O, Velo E, Rettore C, Altavilla G. Pseudotumoral appearance of peliosis hepatis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:558–559. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.2.01850558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gouya H, Vignaux O, Legmann P, de Pigneux G, Bonnin A. Peliosis hepatis: triphasic helical CT and dynamic MRI findings. Abdom Imaging. 2001;26:507–509. doi: 10.1007/s00261-001-0023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinke K, Terraciano L, Wiesner W. Unusual cross-sectional imaging findings in hepatic peliosis. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:1916–1919. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1675-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vignaux O, Legmann P, de Pinieux G, Chaussade S, Spaulding C, Couturier D, et al. Hemorrhagic necrosis due to peliosis hepatis: imaging findings and pathological correlation. Eur Radiol. 1999;9:454–456. doi: 10.1007/s003300050691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanoff M, Rawson AJ. Peliosis hepatis. An anatomic study with demonstration of two varieties. Arch Pathol. 1964;77:159–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]