Abstract

Background

Fresh-frozen plasma (FFP) is unanimously recognised by international guidelines as the blood component of choice for the management of acute haemorrhage when accompanied by disorders of haemostasis, for disseminated intravascular coagulation in the presence of haemorrhage, for rare bleeding disorders when specific clotting factor concentrates are not available and for thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. The literature, however, reports a high percentage of inappropriate requests for FFP. This article presents the results of a pilot study of clinical auditing of the use of FFP in the Region of Umbria (Italy).

Methods

This study was based on the examination of the requests for FFP made in April 2006 to four Immunotransfusion Services (ITS) in Umbria and of the clinical records of the patients receiving transfusions. The following indicators were identified and evaluated: completeness of the request, appropriateness of the indication and the dose, completeness of the records in the clinical charts, adverse events, in-hospital morbidity and mortality, efficacy of the treatment (evaluated by analysing the changes between pre- and post-transfusion coagulation test results) and, as an indicator of the process, the correspondence between data in the paper request form and in the computerised database. The data were extracted from the ITS databases, from the paper request forms and from the patients’ clinical records.

Results

Two hundred and twenty-one requests (615 units of FFP) for 109 patients and 92.8% of the related clinical records were examined. The patients were admitted in medical (22.9%), surgical (51.4%) and critical care units (25.7%). In 50.7% of the cases, the completeness of the data in the individual requests was good (65–80% of the fields filled in). The indication was appropriate in 31.5% of the requests evaluated (56.1% of the total), with no difference related to different requesters. The dosage was appropriate in 62.7% of the requests evaluated (62% of the total). A comparison of pre- and post-transfusion laboratory data showed a significant correction of pathological values (p=0.02) only for the International Normalised Ratio (INR).

Conclusions

Critical areas that should be targeted by interventions to improve plasma usage are those related to the appropriateness of the indication, the completeness of the data entered in the request forms and the data recorded in the clinical charts.

Keywords: plasma, appropriateness, audit

Introduction

Fresh-frozen plasma (FFP) is widely used in clinical practice1,2 despite the fact that, in the major international guidelines, the indications for the use of this blood component are limited to a few conditions3–7: the treatment of acute haemorrhage only if accompanied by abnormal coagulation test results, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) only in the presence of haemorrhage, congenital or acquired deficiencies of single clotting factors and rare bleeding disorders for which a specific concentrate is not available, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and, albeit not unanimously agreed upon, as a treatment to neutralise iatrogenic dicoumarol-induced coagulopathy in the presence of bleeding or when surgery is to be performed. Inappropriate requests for plasma transfusions, besides exposing patients to the risks of transfusion8–11, reduce the availability of FFP that can be allocated to the production of plasma derivates, which still remains insufficient to cover national needs. Published data show that FFP is often inappropriately used, with values of appropriate use ranging from 27% to 90%12–18 in the series examined. Clinical auditing seems to be an effective instrument to improve the use of FFP: a 6-month audit carried out by Kakkar19 et al. in a hospital in the North of India and repeated after 2 months of medical education, through an information campaign, produced a 26.6% improvement in the appropriateness of requests. Decreases in inappropriate use of FFP were observed by Yeh20 et al. following an educational programme for doctors (decrease of 5.2%) and publication of computerised, consultable guidelines (decrease of 30%). In that study, it was predicted that the use and availability of the guidelines and periodic auditing could decrease transfusions by 74.6% and inappropriateness by 30–65%.

The current study is the pilot phase of a project of the Region of Umbria aimed at optimising the use of FFP throughout the Region by implementing a system of indicators of therapeutic appropriateness and efficacy and the introduction of shared guidelines. The aim of this study was to identify and evaluate the indicators of completeness and appropriateness of requests for FFP and the therapeutic efficacy of the product in a consecutive sample of requests for FFP managed at the regional ITS in a 1-month period.

Materials and methods

Design of the study

The study was divided into the following steps: 1) analysis of the forms being used in the regional ITS for requesting plasma; 2) definition of the system of indicators and relative standards; 3) identification of the data to collect; 4) collection and processing of the data. The project included data from all patients who received transfusions of plasma in Umbrian hospitals in April 2006.

The informatic systems used in the ITS are: TMM (Mesis, Macerata, Italy) in one ITS and Emodata (Tesi, Milan, Italy) in the other three ITS. The latest update of this latter software, used in the SIT of Perugia health authority, includes a form designed to collect data for the evaluation of the appropriateness of requests, controls their conformity with guidelines used and, furthermore, guarantees the extraction of data in real time through online queries. The software used for the statistical analyses were: Stata (StataCorp LP, Texas, USA) and SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Participating centres

Four ITS of the region of Umbria participated in this study: the ITS in Perugia, Terni, Città di Castello and Foligno.

Indicators

The indicators identified and used were: a) completeness of compiling the request form; b) appropriateness of the indication stated in the request form; c) appropriateness of the dosage; d) completeness of the records in the clinical charts; e) adverse events; f) short-term morbidity and mortality in the treated population; g) efficacy of the treatment itself and h) correspondence between the data in the paper request form and in the database.

The data used to define the indicators were: description of the requests (requesting ward, time and date of the request); general information on the patient to receive the transfusion (surname, name, sex, date of birth, body weight); history (information on previous transfusions and on any adverse events); the indication for the transfusion (diagnosis, type of surgery, predicted bleeding, any concomitant clinical conditions, value of the parameter to be corrected); number of units requested; compilation of the clinical record forms (medical and/or nursing diary, transfusion sheet, coagulation tests).

Indicators of the completeness of the compilation of the request forms

The information required in the plasma request forms used in the four regional ITS were compared; the individual items were divided into those required by all the ITS (homogeneous fields) and those asked for in only some of the forms (specific fields). The completeness of the information provided was evaluated as a percentage of compilation of data entries required by all four regional ITS request forms (100% standard). The completeness of compilation of the individual different request forms was then evaluated for each ITS. In this latter evaluation, the request was defined as “excellent” if more than 80% of the fields were filled; “good” if between 65% and 80% were filled; “adequate” if between 55% and 65% of the fields were filled and “inadequate” if entries had been made in less than 55% of all the fields in the form.

Indicators of the appropriateness of the indication

The indicators used to evaluate the appropriateness of the indication were: the diagnosis or the reason for the plasma transfusion and the laboratory values in the 12 hours preceding the request. In accordance with guidelines from Perugia hospital21 the following indications for requesting FFP were considered appropriate: a) haemorrhage with abnormal coagulation test results (INR ≥1.5 or aPTTratio ≥1.2); b) congenital or acquired deficiencies of single clotting factors, in the presence of bleeding or when the patient had to undergo an invasive procedure and concentrates of the specific factors could not be used or when there was a lack of multiple factors; c) acute phase disseminated intravascular coagulation (abnormal PT and/ or aPTT required); d) thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, haemolytic-uraemic syndrome, HELLP syndrome; e) coagulopathy due to oral anticoagulants, within or above the therapeutic range, in the presence of active haemorrhage or the need for surgery.

Indicators of the appropriateness of the dosage

The indicators used to evaluate the appropriateness of the dosage were: body weight and the number of units of FFP requested. The dosage was considered appropriate if the amount of FFP requested was between 10 and 15 mL/ Kg, identified as the theoretical optimal quantity in the hospital guidelines21 and considering a mean volume of 175 mL ±10% for the units of plasma prepared in Umbria. Criteria for defining the appropriateness of the dosage for specific pathologies were not identified.

Indicators of the completeness of the data in the clinical records

The following parameters were used to evaluate the completeness of recording information in the clinical charts: presence of a copy of the paper form requesting the plasma, record of the number of units infused and any units returned to the ITS, record of the transfusion in the medical and/or nursing diary, and the presence of laboratory evaluations of coagulation tests carried out pre- and post-transfusion (within 12 hours before and after).

The completeness was also evaluated singularly for each indicator, considering the clinical records to be complete when all the parameters listed above were included.

Indicators of adverse events

The occurrence of any adverse events as a result of the transfusion of plasma was assessed by examining both the transfusion record sent from the wards to the ITS and the patients’ clinical records. Indicators of adverse events were considered to be anaphylaxis, non-haemolytic febrile reactions, TRALI, circulatory overload and minor allergic reactions.

Indicators of mid-term morbidity and mortality

Mid-term morbidity and mortality in the treated population were determined from the medical and/or nursing diary in the clinical records and, therefore, refer exclusively to the period spent in hospital after the transfusion.

Indicators of therapeutic efficacy

The parameters used to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of the transfusion of FFP were pre- and post-treatment laboratory results (INR and aPTT ratio), extracted from the clinical records. Treatment with plasma was defined as effective from a laboratory point of view when it corrected previously abnormal coagulation test results. This analysis was carried out in the subgroup of patients who had both pre- and post-transfusion data and abnormal pre-transfusion data.

Indicators of the process: correspondence between data entered in the paper request form and in the database

The data in the paper request form were compared with those entered into the database. The following data were considered: the patient’s general information (surname, name, date of birth and sex), amount of plasma requested, active haemorrhage, laboratory values, patient’s weight, degree of urgency of the request and reason for the transfusion of plasma. At the time of this study, only the ITS of Perugia hospital had a computerised database for these data. For each individual indicator, the percentage of concordant data was assessed.

All the data described above, extracted from the computerised archives, paper requests and clinical records and entered into an ad hoc database (Microsoft Excel, New Mexico, USA) were used in the subsequent stage of analysis.

Analysis of the data

Simple descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation and proportion expressed as a percentage) are used to characterise the population, the distribution of the requests, the quality of data entry in the informatic systems and the completeness of recording the transfusion and relative treatment in the clinical records. On the basis of the distribution observed, the patients who had a transfusion of FFP were grouped according to area of care (medical, surgical and critical care units) for subsequent analyses.

The χ2 test was used to compare the completeness and appropriateness of requests arriving from the different areas; p values less than 0.05 are considered statistically significant. The two-tailed t-test for paired data was used to compare coagulation test values before and after transfusion of plasma and Student’s t test to calculate the relative confidence intervals.

Financing and approval of the project

The project was approved by the General Management of the four health authorities involved and financed by the Region of Umbria in the context of research aimed at producing the Document Evaluating Determinants of Health and Strategies (DVSS) of the Regional Health Care Service for 2004. Authorisation to consult the patients’ clinical records was requested (Legislative Decrete n. 196/ 2003).

Results

During the observation period of the study there were 221 requests for a total of 615 units of FFP. However, 798 units were supplied because some of the requests did not specify the amount required but the units were nevertheless delivered after the transfusion doctor had obtained clarification from the requester. The ITS in Perugia received 78.3% of the requests for FFP; the ITS in Terni 13.1%, that in Città di Castello 6.3% and that in Foligno 2.3%. In 50.5% of the cases, the requests were made between 8 a.m. and 2 p.m., in 30.3% of cases between 2 p.m. and 8 p.m. and in 19.2% of cases between 8 p.m. and 8 a.m. Furthermore, 85.1% of the requests were made during working days. Overall, 109 patients (males=68.8%, females=31.2%; mean age 66.4 ± 21.3 years) received a transfusion of plasma; 22.9% of the patients were staying in medical, 51.4% in surgical and 25.7% in critical care units.

Description of the completeness of data

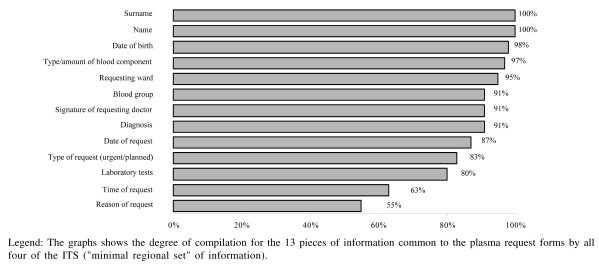

The information requested by the forms in use in the four ITS participating in this study was varied: the form used by the ITS in Perugia consists of 30 entries, the Terni form of 19, the Città di Castello form of 22 and the form used at Foligno of 13. A “minimal regional set” of information required by all the ITS plasma request forms was, therefore, adopted. The request forms were complete for the minimal regional set of data in 86/221 cases (38.9% considering the compilation of at least one of the fields “diagnosis” or “reason for transfusion”). The percentage of request forms lacking only one entry was 26.2% (58/ 221); in 38% of these, the information missing was the date of the request and in 50% the laboratory test results. The percentage of compilation of “homogeneous” information (i.e. information required in all four different forms) is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Completeness of the minimal regional set of information in the 221 request forms for plasma received in April 2006 by the four ITS in the Region of Umbria

The analysis of the individual ITS request forms considering both the minimum regional set and information not homogeneous between the ITS (Table I) revealed that: none of the requests was 100% complete; overall, compilation of the forms was “excellent” in 7.7% of cases (6.2% of the requests from surgical wards, 14.8% of the requests from critical care units and 4.3% of those from medical wards); the completeness of compilation was “good” in 50.7% of cases (51.6% of the requests from surgical wards, 46.3% from critical care units and 52.8% of those from medical wards); compilation was “adequate” in 32.6% of cases (27.9% of the requests from surgical wards, 31.5% of those from critical care units and 40.0% of the requests from medical wards) and, finally, the completeness of data compilation was inadequate in 9.0% of all the request forms (14.3% of the requests from surgical wards, 7.4% of those from critical care units and 2.9% of the forms from medical wards). An analysis of the variability of the frequencies showed, overall, a statistically significant difference (p=0.038), caused by a significant difference (p<0.05) between the areas for the same level of completeness (“good” and “insufficient”). Comparisons between areas for the other categories of completeness did not reveal statistically significant differences. Not all possible paired comparisons were analysed because of the weak power of such statistics given the limited numbers in some groups.

Table I.

Information “not homogeneously” required in the request forms for plasma in the four ITS in Umbria with the number of ITS asking for the specific piece of information and the percentage completeness of compilation of the entry

| “Not homogeneous” Information | SIT (No) | Completeness (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Administrative data | ||

| Code of the requesting ward | 2 | 74 |

| Identification of the doctor (in full) | 2 | 80 |

| Code number of the requesting doctor | 1 | 88 |

| Patient’s data | ||

| Sex | 3 | 95 |

| Body weight | 2 | 92 |

| Height | 1 | 59 |

| Clinical-historical data | ||

| Previous transfusions* | 3 | 78 |

| if yes, data of last transfusion | 2 | 42 |

| Previous transfusion reactions* | 3 | 72 |

| if yes, type of reaction | 2 | 0 |

| Births and/or abortions* | 2 | 9 |

| Children with haemolytic disease of the newborn* | 2 | 5 |

| Surgery | 1 | 18 |

| if yes, type of operation | 1 | 92 |

| if yes, date | 1 | 77 |

| Blood component | ||

| Type of plasma requested** | 1 | 26 |

| Laboratory tests | ||

| Date of test | 1 | 72 |

Legend: The table reports only the information not homogeneously common to the forms by all four ITS, that is, missing from at least one of the four forms. The third column reports the percentage of completed entries for each requested piece of information.

information for which the possible responses were “yes – no – not known”

information for which the possible responses were “standard – II level”

Appropriateness of the indication

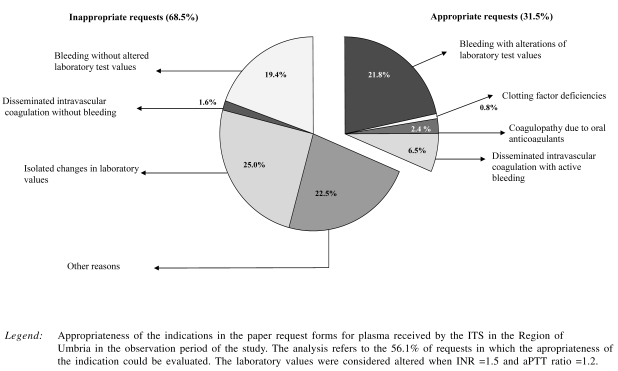

The appropriateness of the indication for transfusion of FFP could be analysed in the 56.1% of the requests that contained information on this issue (diagnosis or reason for the request, INR and/or aPTT ratio values with the date of test performance). It was found that 31.5% of the evaluable requests were appropriate (33.9% of the surgical requests, 23.5% of the requests from critical care units and 35.3% of the medical requests) without any statistically significant difference between the different areas.

In consequence, 68.5% of the evaluable requests were not appropriate. Among these inappropriate requests, 18.5% were made prior to an intervention in order to accelerate the supply of FFP in the case of haemorrhage during the intervention itself (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Appropriateness of the indications in the request forms sample

Appropriateness of the dose

An evaluation of the appropriateness of the requested dose was possible for 137 forms (62%). Using the reference parameters from the hospital guidelines adopted as indicators and standards (a dose of 10–15 mL/kg), the amount of plasma requested was appropriate in 62.7% of the evaluable cases. The requests were inadequate (FFP <10 mL/Kg) in 25.6% of cases and excessive (FFP >15 mL/Kg) in another 11.7% of cases.

Completeness of the data in the clinical records

It was possible to review 92.8% of the clinical records of patients who received a transfusion of plasma. It was found that a copy of the plasma request form was included in the clinical records in 71.2% of cases. The transfusion was recorded in the clinical diary in 77.5% of cases, while pre- and post-infusion laboratory test values were recorded in, respectively, 78.5% and 65.4% of cases. The number of units infused and any units returned to the ITS could be analysed in 100% of the cases, since this information could be retrieved from at least one of the following sources: the transfusion sheet, the form assigning the units and the surgical records.

Adverse events

A single case of hyperpyrexia and shivers occurred during a transfusion of plasma to an 80-year old man with a diagnosis of bacterial pneumonia and an INR of 2.1.

Morbidity and mortality

There were no deaths as a result of transfusion of plasma.

Therapeutic efficacy

The correlation between pre- and post-transfusion values of the parameter used to evaluate the appropriateness of the transfusion was measured in a group of 50 patients who had a pre-infusion INR value greater than 1.5 (mean pre-infusion INR: 2.40; 95% CI; 1.75–3.05; mean post-infusion INR: 1.69; 95% CI; 1.53–1.84). The change was statistically significant (p=0.02 t-test for paired data). In contrast, the correlation was not statistically significant for the aPTT ratio (p = 0.07, t-test for paired data) although the mean value decreased from 1.9 pre-infusion to 1.3 post-infusion (calculated using the data from 26 patients who had a pre-transfusion aPTT ratio greater than 1.2). The two subgroups did not include patients with a diagnosis of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Control of the process: correspondence between the data recorded in the paper request forms and in the database

The surname, name and date of birth of the patients undergoing transfusion were present in both the paper request forms and the computer data and coherent in all cases. Data on gender corresponded in 99% of the cases. The amount of FFP requested, present in only 125 of the paper request forms (72.3%), was always entered in the database (100%). The correspondence for both active bleeding and the patients’ body weight was 68%. The correspondence of the records of INR and aPTT ratio values was higher, being 94% and 86%, respectively. The correspondence for the degree of urgency of the request was 83%. As far as concerns the reason for the transfusion of plasma, the correspondence was 90.1%, but this aspect was evaluable in only a limited percentage of cases (43%), since the data were often entered in a free field not processed by the data extraction procedure set up for the study and different from the specific field provided by the programme.

Discussion

Clinical audit of the use of FFP is considered a valid method for improving the use of this blood component22. A study carried out in two stages by Lahrmann’s group23 showed that the percentage of inappropriate requests for plasma decreased from 46.4% to 38.9% following systematic education of health care staff with related procedural modifications.

Our pilot study enabled us to photograph the current use of FFP in Umbria, in preparation for a similar intervention, planned at a regional level in accordance with the Committees for the Good Use of Blood, which discussed the results of the study in order to introduce improvements in the hospital practice. The picture that emerged was not completely satisfactory and revealed critical areas requiring the greatest attention. In particular, the degree of completeness of compilation of the request forms was evaluated. As demonstrated by Hui24, changes in a request form have considerable effects on the percentage of appropriateness of the requests themselves25. Our working hypothesis was that a well-structured, unequivocal request form, reporting data targeted at a correct evaluation of the appropriateness, would facilitate prospective audits. Our survey showed that the information collected in the request forms differed considerably between the four hospital authorities involved (the number of entries ranged from 13 to 30). Some fields considered indispensable in most guidelines (e.g. the patient’s weight) were not present in one of the forms, although these data were usually added next to the fields for the entries concerning the patient’s general information. Our study has highlighted the need to uniform the collection of data in order to be able to evaluate the good use of FFP at a regional level. It is probable that plasma request forms that require only fundamental, but complete, information would make compilation by the requesting doctor easier and more precise as well as facilitating subsequent evaluation by the ITS doctor. In this view, the percentage of information provided could be a valid instrument for preparing an educational intervention aimed at improving the compilation of the request forms.

Another indicator that, in our opinion, is important with regards to both the clinical indication and the dose of plasma is the appropriateness of the use of FFP. Concordant with other data reported in the literature15–18, our study showed that the indication for the use of FFP was fully correct in only 31.5% of the requests; 19.4% of the requests cited only haemorrhage as the indication, which according to the reference guidelines is not appropriate alone as an indication. However, following an analysis of the clinical records, it was found that in 1.6% of the cases (two requests) laboratory tests were in fact abnormal and in 4.0% of cases (five requests) were ongoing while the request was processed. Thus, the major factor conditioning the evaluation of the inappropriateness of requests was actually incorrect compilation of the request form. Moreover, for reasons of local organisation, a further 18.5% of requests were sent before a patient was to undergo major surgery and then confirmed telephonically during the operation itself if needed. The appropriateness of these requests is difficult to evaluate, and even if they were combined with those appropriate in the first instance and those appropriate after checking the data in the clinical records, the overall percentage of appropriate indications would reach no more than 55.6%. The requested dose was appropriate in 62.7% of the forms. It should, however, be remembered that there are sources of variability in the calculation of the required dose: the mean volume of units of FFP is 175 mL ±10% and it is affected by differences in the amount of whole blood collected (450 mL ± 10%) and the donor’s haematocrit. One factor potentially responsible for the low levels of appropriateness is the lack of shared regional guidelines adopted by the various regional ITS and the specialists most involved in the use of FFP. Periodic updating of such guidelines could constitute an occasion for ad hoc education aimed at improving the appropriateness of the requests.

In the context of the evaluation of the completeness of data recording in the clinical charts, it emerged that the procedures for archiving documents varied greatly between the hospitals; this not only made the collection of data difficult, but also highlighted the need to uniform some procedures, such as, for example, recording the transfusion on an appropriate transfusion sheet.

During the period of this pilot study, only one adverse event was observed which was, moreover, only mild and with non-specific symptoms that could not be related unequivocally to the plasma transfusion.

Albeit on a limited quantity of data, the analysis of the clinical records revealed that plasma was often requested because of the finding of a prolonged INR, even if not always in the presence of bleeding, as illustrated in figure 2. The INR value was modified significantly from a mean value of 2.4 to 1.7 within 12 hours of the transfusion, usually without further requests for plasma. It is difficult to reconcile this finding with the indication in the best accredited guidelines of considering INR values below 1.5 as safe, even though a recent update of the American Society of Anesthesiologists guidelines26 has suggested the use of a threshold value of 2. The correction in aPTT ratio values, reduced from a mean of 1.9 to 1.3, were not statistically significant. The guidelines should specify unequivocally when plasma is indicated and at what dose to revert dicumarol-induced anticoagulation.

Another interesting aspect of this study was the evaluation of the accuracy of data entry into the ITS computerised data management system. A comparison of the data recorded on paper and those entered into the ITS database was used as an indicator of the process. In fact, in this study the indicator was not used to evaluate two different methods of making a request, but to verify the accuracy of data entry in the ITS, showing that this cannot be assumed to occur without error. In fact, the information missing in the database, where called for, was mostly that entered in fields containing “free text” rather than in “structured” fields. As a consequence, when designing the on-line request form for use in the wards (in preparation at the ITS of Perugia hospital), great care must be given to making the compilation simple and unambiguous in order to improve the data available in the informatic system.

The main limitation of our retrospective study is its short observation period (April 2006), since there is a sensible risk of having sampled a period not representative of real clinical practice. This brief observation period was, however, chosen as a compromise to reconcile resources available and the aim of the working group, which was to determine whether the study design was appropriate before continuing with a second observation phase of 6 months.

Another limitation of our study is related to its retrospective nature: the criteria used for the appropriateness evaluations were established after the compilation of the request forms. These criteria were defined on the basis of the major existing guidelines, whose indications are, in fact, rather heterogeneous. The aim of the study was, however, to photograph the existing situation, in order to introduce improvements. A verification of the level of appropriateness obtained after the introduction of shared regional guidelines will be demonstration of the validity of our working hypothesis.

Finally, the heterogeneity of the procedures and related forms used in the region’s different hospitals made the analysis of data difficult and made it complicated to establish evaluation criteria that could be applied to the whole set of requests.

In conclusion, the results of this study show that not only must the quality of prescription of FFP be improved, but also that all procedural aspects need to be uniformed, from the request form itself to the management of the information and the documents in the clinical records, since data produced by the measurement and evaluation systems are important from clinical, epidemiological and management points of view. The completeness of the compilation of both the request forms and the clinical records, as well as the appropriateness of the indication for and the dose of FFP were found to be the most critical issues to deal with during the production of regional guidelines and those most necessary to subject to constant evaluation, through periodic auditing, in order to determine the appropriateness of the use of FFP. Only regular audits, conducted by a multidisciplinary working group, will be able to monitor and verify the efficacy, if any, of the interventions that should be implemented to produce improvements, such as the production of guidelines agreed upon at a regional level, training courses for all staff, the introduction of a standard form for use throughout the Region, and the adoption of shared standard operative procedures for all the relevant steps, from the acceptance of the request forms to the recording of data in the clinical charts.

References

- 1.Palo R, Capraro L, Hovilehto S, et al. Population-based audit of fresh-frozen plasma transfusion practices. Transfusion. 2006;46:1921–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Triulzi DJ. The art of plasma transfusion therapy. Transfusion. 2006;46:1268–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits de Santé. Transfusion de plasma frais congelé: produits, indications. Transfus Clin Biol. 2002;9:322–32. doi: 10.1016/s1246-7820(02)00265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crosby E, Ferguson D, Hume HA, et al. Guidelines for red blood cell and plasma transfusion for adult and children. Can Med Assoc J. 1997;156 (Suppl):S1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) ASoBTA. Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Use of Blood Components (red blood cells, platelets, fresh frozen plasma and cryoprecipitate) 2002. Available at: http://www.nhmrc.health.gov.au.

- 6.O’Shaughnessy DF, Atterbury C, Bolton MP. Guidelines for the use of fresh-frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate and cryosupernatant. Br J Haematol. 2004;126:11–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Task Force on Blood Component Therapy. Practice Guidelines for blood component therapy: a report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 1996;83:732–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowden R, Sayers M. The risk of trasmitting cytomegalovirus infection by fresh frozen plasma. Transfusion. 1990;30:762–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1990.30891020340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan H, Belsher J, Yilmaz M, et al. Fresh frozen plasma and platelet transfusions are associated with development of acute lung injury in critically ill medical patients. Chest. 2007;131:1308–14. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Politis C, Kavallierou L, Hantziara S, et al. Quality and safety of fresh-frozen plasma inactivated and leucoreduced with the Theraflex methylene blue system including the Blueflex filter: 5 years’ experience. Vox Sang. 2007;92:319–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2007.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Webert KE, Blajchman MA. Transfusion-related acute lung injury. Transfus Med Rev. 2003;17:252–62. doi: 10.1016/s0887-7963(03)00039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beloeil H, Brosseau M, Benhamoud D. Transfusion of fresh frozen plasma (FFP): audit of prescriptions. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2001;20:686–92. doi: 10.1016/s0750-7658(01)00462-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schofield WN, Rubin GL, Dean MG. Appropriateness of platelet, fresh frozen plasma and cryoprecipitate transfusion in New South Wales public hospitals. MJA. 2003;178:117–21. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luk C, Eckert KM, Barr RM, Chin-Yee IH. Prospective audit of the use of fresh-frozen plasma, based on Canadian Medical Association transfusion guidelines. Can Med Assoc J. 2002;166:1539–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blumberg N, Laczin J, McMican A, et al. A critical survey of fresh-frozen plasma use. Transfusion. 1986;26:511–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1986.26687043615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brien WF, Butler RJ, Inwood MJ. An audit of blood component therapy in a Canadian general teaching hospital. Can Med Assoc J. 1989;140:812–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones P, Jones A, Al-Ismail SS. Clinical use of FFP: results of retrospective process and outcome audit. Transfus Med. 1998;8:37–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3148.1998.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mozes B, Epstein M, Bassat BI, et al. Evaluation of the appropriateness of blood product transfusion using present criteria. Transfusion. 1989;29:473–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1989.29689318442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kakkar N, Kaury R, Dhanoa J. Improvement in fresh frozen plasma transfusion practice: results of an outcome audit. Transfus Med. 2004;14:231–5. doi: 10.1111/j.0958-7578.2004.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeh CJ, Wu CF, Hsu WT, et al. Transfusion audit of fresh-frozen plasma in southern Taiwan. Vox Sang. 2006;91:270–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2006.00819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Comitato per il buon uso del sangue. Azienda Ospedaliera di Perugia. [Accessed on line on 12 September 2007];Standard terapeutici e modalità operative per il buon uso del sangue 2002. Available at: www.ospedale.perugia.it.

- 22.Barnette RE, Fish DJ, Eisenstaedt RS. Modification of fresh-frozen plasma transfusion practices through educational intervention. Transfusion. 1990;30:253–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1990.30390194348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lahrmann C, Hojlund K, Kristensen T, Georgensen J. Use of fresh frozen plasma in patient treatment. Indications illustred by a literature review and a study of practice at a university hospital. Ugeskr Laeger. 1996;158:3467–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hui CH, Williams I, Davis K. Clinical audit of the use of fresh-frozen plasma and platelets in a tertiary teaching hospital and the impact of a new transfusion request form. Intern Med J. 2005;35:283–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2005.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuckfield A, Haeusler MN, Grigg AP, Metz J. Reduction of inappropriate use of blood products by prospective monitoring of transfusion request forms. Med J Aust. 1997;167:473–6. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb126674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Society of Anesthesiologist. Practice guidelines for preoperative blood transfusion and adjuvant therapies. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:198–208. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200607000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]