Abstract

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a disabling psychiatric condition for which effective treatment remains an outstanding need. Antidepressants are currently the mainstay of treatment for depression; however, almost two-thirds of patients will fail to achieve remission with initial treatment. As a result, a range of augmentation and combination strategies have been used in order to improve outcomes for patients. Despite the popularity of these approaches, limited data from double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled studies are available to allow clinicians to determine which are the most effective augmentation options or which patients are most likely to respond to which options. Recently, evidence has shown that adjunctive therapy with atypical antipsychotics has the potential for beneficial antidepressant effects in the absence of psychotic symptoms. In particular, aripiprazole has shown efficacy as an augmentation option with standard antidepressant therapy in two, large, randomized, double-blind studies. Based on these efficacy and safety data, aripiprazole was recently approved by the FDA as adjunctive therapy for MDD. The availability of this new treatment option should allow more patients with MDD to achieve remission and, ultimately, long-term, successful outcomes.

Keywords: major depression, antipsychotic, mood disorder, aripiprazole

Introduction

Effective treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) remains an outstanding need in psychiatry. In the past, adjunctive antipsychotics were used primarily for treating psychotic symptoms in patients with MDD. However, current evidence indicates that these agents have antidepressant effects in patients with non-psychotic major depression. Recently, the atypical antipsychotic aripiprazole received approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as adjunctive therapy for patients with MDD. Given these developments, this review of the need for augmentation strategies, the range of options available, and the clinical evidence base for aripiprazole as the newest adjunctive medication for MDD was undertaken.

Epidemiology and disease burden

Major depressive disorder is a common and disabling psychiatric condition (Murray and Lopez 1996). Current estimates for lifetime prevalence of MDD range from 17% to 18%, making it one of the most prevalent mental health disorders (Kessler et al 2003). According to the Global Burden of Disease Study (Murray and Lopez 1996, 1997), depression currently ranks as the fourth leading cause of global disease burden, with the disorder affecting 13–14 million adults in the United States in a given year (Kessler et al 2003). By 2020, depression is projected to be the second leading cause of disease burden worldwide after heart disease. Furthermore, MDD is associated with high morbidity and mortality; for example, up to 15% of individuals with more severe forms of this disorder die by suicide (APA 2000). MDD also incurs huge health care costs: in 2000, depression (major depressive disorder, bipolar depression or dysthymia) incurred an estimated cost of US $83.1 billion, which was related to treatment costs, loss of productivity and suicide-related costs (Greenberg et al 2003). Another study that excluded bipolar depression found that employees with MDD have costs of lost work time totaling US$31 billion compared with peers without depression (Stewart et al 2003).

Depression comorbid with other chronic diseases, such as diabetes and arthritis, worsens overall health and well-being. Several studies have shown that there is an increased risk of major depression in individuals with one or more chronic diseases (Katon and Schulberg 1992; Noel et al 2004; Harpole et al 2005; Katon et al 2007). Indeed, data suggest that there is an interactive/synergistic effect between depression and chronic medical conditions, resulting in a negative effect on health beyond a simple additive effect of each condition (Moussavi et al 2007). In addition, depression aggravates the course of various medical conditions, even increasing mortality in patients with heart disease and stroke (Frasure-Smith et al 1993; Morris et al 1993).

If left untreated, depression may develop a chronic course or be recurrent, and over time be associated with increasing disability (Andrews 2001, Solomon et al 2000). Given the prevalence, chronicity and associated disability of MDD, there has been an increased focus on the development of new and more effective treatment options for this condition.

Diagnosis and neurobiology

MDD is a complex disease state with variable symptoms, presentation, features, and course. This variability is a challenge to the clinician and complicates diagnosis. The DSM-IV-TR defines MDD as the presence of single or multiple major depressive episodes once schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorders, bipolar illness and episodes due to substance abuse or medical illness have been excluded (APA 2000).

Major depression is a heterogeneous disorder and, to date, causal mechanisms remain unclear. Psychological, biological, and environmental factors have all been shown to contribute to the development of MDD. For example, a recent review of twin studies estimated that about 37% of the risk of MDD is inherited (Sullivan et al 2000).

The early observation that many compounds that inhibit monoamine reuptake have antidepressant properties suggested that these neurotransmitters may be involved in the etiology of depression. Subsequently, many abnormalities in the serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine systems have been identified but it remains unclear which are primary, which are compensatory, and which are changes unrelated to depression (Belmaker and Agam 2008). A possible role for serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine in various behaviors associated with depression has been suggested by animal studies; yet, to date, these relationships have not been validated in depressed human patients. In fact, a comparison of the symptom effects of two antidepressants selective for different neurotransmitters – serotonin and norepinephrine – found no differences in the symptoms that improved, suggesting that they both may act through a final common pathway (Nelson et al 2005).

Alternatively, the role of neurotransmitters in the mediation of antidepressant action is relatively better established. Studies that use tryptophan depletion to lower serotonin and alpha-methyl-paratyrosine to inferfere with the synthesis of catecholamines indicate that serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine are involved in the mechanism of action of most antidepressant compounds (Delgado et al 1990; Miller et al 1996).

Treatment and management

Treatment goals

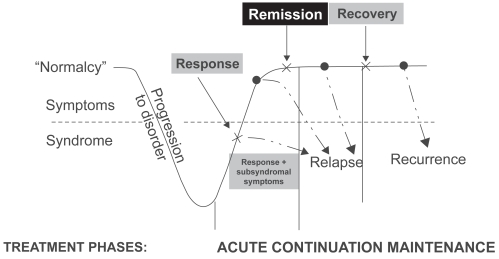

Once a patient is diagnosed with MDD, treatment of MDD should aim to achieve full resolution of symptoms and full restoration of psychosocial and occupational functioning. Treatment initially focuses on the rapid resolution of symptoms during the acute phase with the goal of remission. As the patient moves into continuation therapy, the goal is to maintain remission and prevent relapse. Remission represents a pivotal stepping stone on the road to recovery and is the key goal of pharmacological treatment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Remission is the key stepping stone between response to an acute episode and achieving full recovery (After Kupfer 1991).

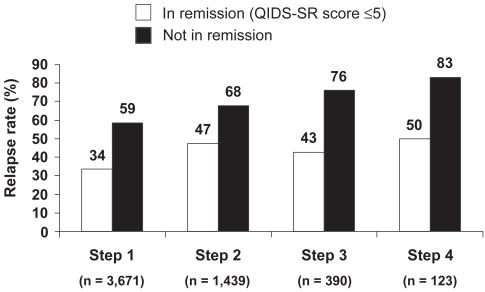

Early achievement of symptomatic remission is critical to the long-term success of treatment (Kupfer 2005). Residual symptoms and partial response are associated with an increased risk of relapse, faster time to relapse, a more severe and chronic course, and increased functional impairment (social, occupational, home life) (Paykel et al 1995; Papakostas et al 2004). The importance of achieving remission has been well illustrated in the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study. As shown in Figure 2, at each treatment level, patients who achieved remission were less likely to relapse than those not achieving remission (Rush et al 2006; Rush 2007). Collectively, these data validate the importance of remission as a clinically meaningful endpoint.

Figure 2.

Remission at entry into follow-up was associated with lower relapse rates than response without remission in STAR*D study (12-month follow-up period) (After Rush et al 2006).

Relapse = QIDS-SR score ≥ 11.

Treatments

Antidepressants are currently the mainstay of treatment for depression and depressive episodes. Many different classes of antidepressants exist, including monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MOAIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), serotonin modulators, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), dopamine-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (DNRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and norepinephrine-serotonin modulators. The effectiveness of antidepressant medications is generally comparable. Although a possible advantage for dual-action agents has been suggested, a meta-analysis of 93 studies comparing dual-action agents with SSRIs found the advantage, although significant, was small, with a pooled response rate of 63.6% for dual-action agents vs 59.3% for SSRIs (Papakostas et al 2007b).

Despite the availability of more than two dozen different antidepressants, these treatments often yield inadequate results. Up to 70% of patients with MDD do not reach remission with an adequate course of one antidepressant and experience poorer long-term outcomes (Fava 2003; Rush et al 2006; Trivedi et al 2006). In addition, STAR*D demonstrated that, with each failed treatment trial, remission rates declined. Remission rates after two or three failed treatments averaged less than 15% (Rush et al 2006).

According to American Psychiatric Association (APA) practice guidelines, if a patient with MDD has not responded to treatment or achieved only a partial response to treatment after 4–8 weeks of therapy during the acute phase, a change in dose, a switch to a new drug, or augmentation therapy is recommended (American Psychiatric Association 2000). A range of augmentation and combination strategies have been used (Fava et al 2003; Rush et al 2004). The challenge for clinicians is to tailor and adjust treatment options for individual patients in order to identify the most appropriate treatment approach.

Augmentation and combination strategies

Both augmentation and combination strategies have been used in patients with major depression. Combination strategies are those that use two antidepressants, each of which is approved as monotherapy. Augmentation strategies add an agent that is not conventionally used as first-line monotherapy (ie, atypical antipsychotic, lithium, T3) to an antidepressant. Augmentation and combination strategies have been proposed on the assumption that such combinations may have additive or synergistic effects (Rush et al 2006; Rutherford et al 2007). Furthermore, addition of a second agent in a partial responder has the practical advantage of maintaining any improvement made and may result in a rapid response. Notably, the efficacy of augmentation and combination treatments is not limited to partial responders, but has been less well studied in non-responders. For the purpose of this review article, we recognize the terms “augmentation” and “adjunctive” as similar in meaning and may use them interchangeably throughout the text.

Although combination approaches are commonly used, the evidence base is quite limited. The popular combination of bupropion and SSRI has not been examined in placebo-controlled studies. “Best evidence” is limited to an open-label, randomized comparison study in STAR*D (Trivedi et al 2006). Similarly, the best evidence for the combination of venlafaxine and mirtazapine is an open-label, randomized comparison (McGrath et al 2006). The combination of mirtazapine and an SSRI has been studied and found effective in two controlled studies of 26 and 62 patients, respectively (Carpenter et al 2002; Blier et al 2003). Desipramine added to fluoxetine has been demonstrated to be effective in a small study of 39 inpatients (Nelson et al 2004), but only half of the sample were previously treatment resistant. Overall, controlled trials of combination strategies are limited in number, are limited in sample size (largest is n = 62), and are variable in their requirements for prior treatment resistance.

A variety of agents have been used to augment antidepressants. The most frequently studied strategies are lithium, thyroid, stimulants, buspirone, pindolol, and omega-3 fatty acids. Addition of stimulants is one of the oldest strategies and most studies were small, open-label, and added dextro-amphetamine or methylphenidate to a tricyclic or an MAOI. A recent placebo-controlled, double-blind trial in 60 patients augmented an SSRI with methylphenidate but failed to find a significant advantage for the augmentation approach (Patkar et al 2006a). Open-label studies of buspirone and pindolol suggested efficacy but a controlled trial of buspirone failed (Landen et al 1998), as did two controlled trials of pindolol in treatment-resistant patients (Moreno et al 1997; Perez et al 1999).

Lithium augmentation was the first approach suggested on the basis of a neurochemical rationale (De Montigny et al 1981). Subsequently, lithium augmentation has been studied in 10 placebo-controlled trials and a meta-analysis of these trials has been reported (Crossley and Bauer 2007). Although the meta-analysis showed evidence of efficacy, the value of lithium augmentation continues to be debated. The largest controlled lithium study included 61 patients but all the others were small studies (≤35 patients). Few included clearly resistant patients, and the only study that did include treatment-resistant patients failed to find any advantage for lithium (Nierenberg et al 2003). Addition of triiodothyronine (T3) has also received considerable attention. A recent meta-analysis of T3 studies found evidence for efficacy; however, when limited to placebo-controlled trials, only 75 patients were studied in four trials and the difference between T3 and placebo was not significant (Aronson et al 1996). All of these controlled trials added T3 to a tricyclic antidepressant. In the open, randomized STAR*D comparison (Nierenberg et al 2006), thyroid was significantly better tolerated than lithium augmentation and appeared to be effective. The other augmentation strategy with a growing literature is the addition of omega-3 fatty acids. Although results were variable, a meta-analysis and review document only ten double-blind, placebo-controlled studies in 329 patients with mood disorders who were receiving omega-3 PUFAs for ≥4 weeks (Lin and Su 2007). The results demonstrated a significant effect for omega-3-fatty acid but significant heterogeneity was noted, as was an indication of publication bias. Study designs, patient samples, dosing, and omega-3 constituents were variable. Finally, as with several other strategies, the efficacy of omega-3 in antidepressant-resistant patients needs further study.

Although other augmentation strategies have been suggested, the data for these are more limited. One large trial (n = 308) of modafinil in SSRI partial responders with prominent fatigue and sleepiness did show the drug to be more effective than placebo (Fava et al 2005). One controlled trial of folate in 127 depressed patients showed significant efficacy in women but not in men (Coppen and Bailey 2000). Augmentation studies of testosterone have been negative. Augmentation with estrogen or estrogen/progesterone combinations in post- or peri-menopausal women have been inconsistent (Morgan et al 2005, Dias et al 2006).

Atypical augmentation

Prior to 1980, more than 30 studies explored the use of typical antipsychotics in MDD (Nelson 1987). These trials are limited particularly by the use of earlier diagnostic systems; nevertheless, the findings suggested that patients experienced some relief with these agents. They were never recognized as true antidepressants, perhaps because they were not effective for treatment of two core symptoms of depression – loss of interest and motor retardation (Raskin et al 1970). Two formulations of an antipsychotic (perphenazine) and an antidepressant (amitriptyline) were licensed for use in depression. However, the use of the typical antipsychotics in non-psychotic depression declined rapidly during the 1980s with recognition of their risk of tardive dyskinesia.

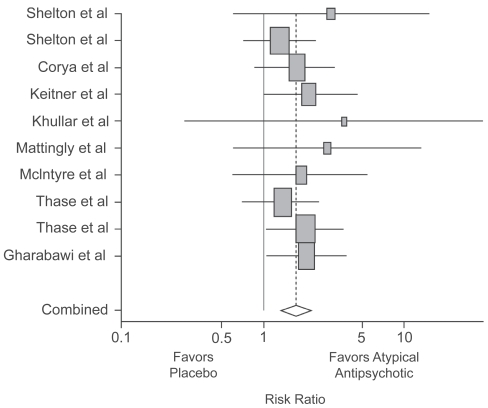

The advent of second-generation antipsychotics with an improved safety profile has prompted their exploration as effective agents for the treatment of MDD. In 1999, Ostroff and Nelson reported the apparent value of adding risperidone in 8 outpatients who had not responded to an SSRI (Ostroff and Nelson 1999). In 2001, Shelton et al reported the first controlled study of olanzapine and fluoxetine vs either drug with placebo in 28 patients showing an advantage for the combination (Shelton et al 2001). Subsequently, a number of open and controlled studies followed. In 2007, Papakostas et al published a review and meta-analysis of atypical augmentation studies (Papakostas et al 2007a). They found 10 studies (olanzapine 5, quetiapine 3, risperidone 2). The studies included 4 smaller samples of 15–58 patients and 6 larger samples of 100–303 patients. All included patients with non-psychotic major depression. Different from the previous literature, several of these studies required evidence of prior treatment failure, usually to one historical and one prospective treatment trial. The meta-analysis found that the trials as a group demonstrated efficacy, although several individual studies did not (Figure 3). The risk ratio for remission comparing atypical antipsychotics with placebo was 1.75 (95% CI 1.36, 2.24; p < 0.0001) and for response was 1.35 (95% CI 1.13, 1.63; p = 0.001). Pooled remission rates were 47.2% and 22.3% for the atypical agents and placebo, respectively. Pooled response rates were 57.2% and 35.4%, respectively. Although this meta-analysis showed no difference in overall discontinuation rates between atypical antipsychotics and placebo, the rate of discontinuations due to adverse events was more than three-fold higher in patients treated with atypical antipsychotic agents than placebo (p < 0.0001).

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of studies of atypical antipsychotic augmentation of antidepressants. Papakostas GI, Shelton RC, Smith J, et al 2007a. Augmentation of antidepressants with atypical antipsychotic medications for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry, 68:826–31. Copyright © 2007 Physicians Postgraduate Press. Reprinted with permission.

Aripiprazole represents one of the most recently developed second-generation atypical antipsychotics. Efficacy for aripiprazole augmentation in depression was demonstrated in two large, randomized, double-blind 14-week studies (Berman et al 2007b; Marcus et al 2008). A third study is currently ongoing. Based on the findings to date, aripiprazole recently received approval from the FDA for the treatment of major depression as an adjunctive agent to standard antidepressant therapy (ADT). Initial open-label studies reported the efficacy of adjunctive aripiprazole in patients with depression (Barbee et al 2004; Papakostas et al 2005; Simon and Nemeroff 2005; Worthington et al 2005; Patkar et al 2006b; Hellerstein et al 2007; Pae et al 2007; Rutherford et al 2007; Schule et al 2007). An overview of the pivotal clinical trial program for aripiprazole in MDD is provided in Table 1. This program provides the most rigorous dataset available for any single agent evaluated for augmentation treatment of MDD, supported by large patient populations, randomized and placebo-controlled study designs, and implementation of historical and prospective demonstration of antidepressant unresponsiveness (Table 1). The remainder of this review focuses on the findings of these studies.

Table 1.

Overview of clinical data for aripiprazole in major depressive disorder

| Study | Aripiprazole starting dose (permitted adjustment), mg | Comparator | Duration | Total n | Primary endpoint | Primary publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN138–139 | 5 (2–20) | Placebo | 6 weeks | 362 | Mean change in MADRS from baseline to Week 6: −8.8 vs −5.8, p < 0.001 | Berman et al 2007 |

| CN138–163 | 5 (2–20) | Placebo | 6 weeks | 381 | Mean change in MADRS from baseline to Week 6: −8.5 vs −5.7, p = 0.001 | Marcus et al 2008 |

| CN138–462 | 10 (10–20) | N/A | 15 days | 38 | No meaningful effects on the pharmacokinetic parameters for venlafaxine (Cmax, Cmin, Tmax, AUC(TAU)) when administered alone and co-administered with aripiprazole | Boulton et al in press |

| CN138–463 | 10 (no adjustment) | N/A | 15 days | 25 | No meaningful effects on the pharmacokinetic parameters for escitalopram (Cmax, Cmin, Tmax, AUC(TAU)) when administered alone and co-administered with aripiprazole | Boulton et al in press |

| CN138–164 | Continuation dose from Studies CN138–139 and CN138–163 | Placebo | 52 weeks | 930 | Incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events | Berman et al 2008 |

| CN138–165 | 5 (2–20) | Placebo | 6 weeks | 349 | Incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events | Unpublished data |

Focus on aripiprazole

Pharmacological rationale

Although the mechanism of action of augmentation is not well understood, it is possible that the distinct pharmacological profile of aripiprazole may make it a suitable adjunctive agent for the treatment of MDD. Differing from conventional antipsychotics, which were thought to have essentially a one-dimensional effect related to D2 antagonism, the atypical drugs have neuropharmacologic profiles that are quite different and may have different implications in depression. Thus, although these agents appear to have similar efficacy in schizophrenia, it is not clear that they have similar efficacy in depression. For example, all of the atypical agents have 5-HT2 antagonist effects that might contribute to antidepressant effects. The synergistic effects of olanzapine and fluoxetine on synaptic levels of 5HT, NE, and dopamine may be useful, and for ziprasidone the possible addition of 5-HT and norepinephrine reuptake blockade is of potential interest. For aripiprazole, the interesting features are its partial-agonist activity at the D2/D3 receptors, in addition to partial-agonist activity at the serotonin 1A (5-HT1A) receptor (Shapiro et al 2003; Jordan et al 2004, Stark et al 2007). An agent, such as aripiprazole, that engages several mechanisms of action might be particularly effective in depression; however, all of these possible synergies are hypothetical and it is unclear how they translate into clinical efficacy.

Pharmacokinetics and dosing

Pharmacokinetic interaction studies have shown that aripiprazole 2–20 mg/kg does not affect the clearance of escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, or venlafaxine; thus, no dosage adjustment is required for these antidepressants when aripiprazole is added. Across four studies, aripiprazole had no clinically meaningful effects on the pharmacokinetics of these standard antidepressant therapies (escitalopram, 10–20 mg/day; fluoxetine, 20–40 mg/day; paroxetine controlled-release, 37.5–50 mg/day; sertraline, 100–150 mg/day; or venlafaxine extended-release, 150–225 mg/day) in either healthy subjects or patients with MDD (personal communication/manuscript submitted). However, fluoxetine and paroxetine are both inhibitors of CYP2D6, and are likely to increase aripiprazole plasma levels (Abilify 2007). The pivotal augmentation studies used the same flexible-dose design. Patients randomized to receive adjunctive aripiprazole were treated with a starting dose of 5 mg/day, which could be increased weekly in 5 mg/day increments to a maximum dose of 15 mg/day (patients receiving fluoxetine or paroxetine CR, due to their CYP2D6 inhibition increasing aripiprazole levels) or 20 mg/day (all other patients) based on assessment of tolerability and clinical response. If tolerated, all patients were to receive a target minimum dose of 10 mg/day. Doses could be decreased at any visit, based on tolerability; patients unable to tolerate 5 mg/day could have their dose decreased to 2 mg/day. The FDA have approved an initial dose of adjunctive aripiprazole in patients with MDD of 2–5 mg/day, with a recommended target dose of 5–10 mg/day and a maximal dose of 15 mg/day. However, the relative efficacy of different doses has not been tested in MDD in fixed-dose studies. Some case studies have been published showing efficacy of aripiprazole augmentation at a dose as low as 3 mg/day (Terao 2007).

Efficacy

In patients with major depression without psychosis who showed an inadequate response to ADT, adjunctive aripiprazole has been shown to augment antidepressant efficacy in two 14-week, double-blind, randomized trials of identical design (Berman et al 2007b; Marcus et al 2008). The studies comprised a screening phase, an 8-week prospective treatment phase, and a 6-week randomization phase. During prospective treatment, patients received escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine controlled-release, sertraline or venlafaxine extended-release, each with single-blind adjunctive placebo. Subjects with an inadequate response (<50% reduction HAM-D17 Total, HAM-D 17 ≥ 14 and Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement [CGI-I] ≥ 3 at the end of the ADT phase) continued ADT and were randomly assigned to adjunctive placebo or adjunctive aripiprazole; subjects were blinded to randomization (ie, the use of single-blind placebo). In the Marcus et al study, a total of 381 patients were randomized to adjunctive placebo (n = 190) or adjunctive aripiprazole (n = 191) in the randomized, double-blind treatment phase (Marcus et al 2008). In the Berman et al study, a total of 178 patients were randomly assigned to adjunctive placebo and 184 to adjunctive aripiprazole (Berman et al 2007b). It is also notable that, in both studies, the use of benzodiazepines or other sleep aids were not permitted, so that sedation/somnolence-inducing agents would not confound the efficacy results.

In both studies, remission rates (defined as a MADRS Total score of ≤10 and ≥50% reduction in MADRS Total score from baseline [end of prospective treatment]) were significantly higher with adjunctive aripiprazole than with adjunctive placebo: 26.0% versus 15.7%, p = 0.01 (Berman et al 2007b); and 25.4% versus 15.2%, p < 0.05 (Marcus et al 2008). Remission was achieved in significantly more patients with adjunctive aripiprazole versus placebo early in both studies, as early as week 1 (Berman et al 2007b) and week 2 (Marcus et al 2008).

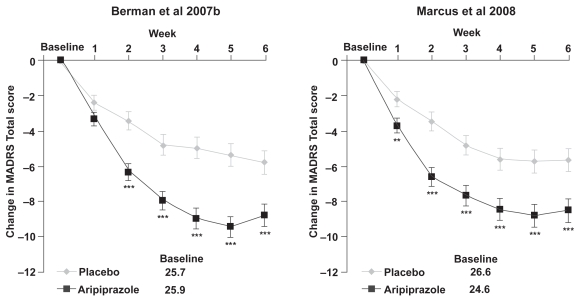

Although remission is critical as an endpoint in real-life practice, for registration purposes the primary endpoint of these studies was the mean change in MADRS Total score from baseline to Week 6. Both studies showed significant improvements with adjunctive aripiprazole over placebo on this measure: −8.8 vs −5.8, p < 0.001 (Berman et al 2007b); −8.5 vs −5.7, p = 0.001 (Marcus et al 2008) (Figure 4). Again, the onset of a significant difference with adjunctive aripiprazole over placebo was apparent by week 1 in the study by Marcus et al (2008) and week 2 in the study by Berman et al (2007b), with the adjunctive aripiprazole group continuing to show improvement throughout the study. Response, defined as ≥50% improvement in MADRS total score from baseline, was achieved by significantly more patients in the adjunctive aripiprazole than adjunctive placebo group in both studies at endpoint. Additional measures of efficacy – the Clinical Global Impression of Severity (CGI-S) scores and Clinical Global Impression of Improvement (CGI-I) response rates – showed significantly greater improvements with adjunctive aripiprazole compared with adjunctive placebo (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Change from baseline in MADRS Total score (last observation carried forward) in the two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of adjunctive aripiprazole.

**p < 0.01 vs placebo.

***p < 0.001 vs placebo; MADRS Total score is rated from 0 to 60, where a negative change indicates improvement.

Abbreviations: MADRS, Montgomery – Asberg Depression Rating Scale; LOCF, last observation carried forward.

Efficacy in difficult-to-treat subgroups

In a post-hoc analysis, data from the two double-blind efficacy trials (efficacy sample, n = 722) were pooled in order to determine the efficacy of aripiprazole in subpopulations of patients with MDD. Although it has been suggested that antidepressants may be less effective in anxious depression (Fava et al 2008) and that tricyclics may be less effective in atypical depression, adjunctive aripiprazole showed significantly greater efficacy than placebo in patients with anxious depression (defined by a total score of ≥7 on the anxious/somatization factor of the HAM-D17) or atypical depression (defined using the Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology-Self Rated (IDS-SR) to determine the presence of DSM criteria for Major Depression with Atypical Features) (Thase et al 2007). In addition, adjunctive aripiprazole was effective in both partial responders (≥25% but <50% improvement on the MADRS Total score) and minimal responders (<25% improvement on the MADRS Total score). Change scores on the MADRS Total score were −7.2 with aripiprazole and −5.4 with placebo in partial responders and −9.4 with aripiprazole and −6.0 with placebo in minimal responders (Thase et al 2007).

Tolerability

Overall in the clinical studies, adjunctive aripiprazole was well tolerated. There was a high completion rate in both studies (adjunctive aripiprazole, 87.9%; adjunctive placebo, 90.9% [Berman et al 2007b]; adjunctive aripiprazole, 84.8%; adjunctive placebo, 85.3% [Marcus et al 2008]), and a low discontinuation rate due to adverse events (AEs) (adjunctive aripiprazole, 3.3%; adjunctive placebo, 2.3% [Berman et al 2007b]; adjunctive aripiprazole, 3.7%; adjunctive placebo, 1.1% [Marcus et al 2008]).

Akathisia was the most common AE reported with adjunctive aripiprazole in the two samples occurring in 24.8% of the patients. However, a post-hoc pooled analysis of the 737 patients in the two studies showed that akathisia was of mild to moderate severity in 92% of the cases, only 3 of 371 aripiprazole-treated patients (0.8%) discontinued treatment because of it, and half of the akathisia events resolved at endpoint. The most common interventions associated with resolution were dose reduction (51%) and no intervention (36%) (Nelson et al 2007).

Because both of these studies used a “guided-flexible” dosing strategy that limited changes in aripiprazole dose to 5 mg in weekly increments and recommended a minimum dose of 10 mg/day, the rates of akathisia may overestimate rates obtained in clinical practice in which dosing is further individualized. Aiming for the minimum effective dose may be a prudent strategy. Indeed, in the Berman et al study, approximately half of the patients who completed the study and responded to adjunctive aripiprazole were receiving a dose of 10 mg/day or less (Berman et al 2007b).

Mean weight gain with adjunctive aripiprazole was higher than adjunctive placebo in both studies (+2.01 ± 0.17 kg vs +0.34 ± 0.18 kg, p < 0.001 [Berman et al 2007b]; +1.47 ± 0.16 kg vs +0.42 ± 0.17 kg, p < 0.001 [Marcus et al 2008]) over a 6-week treatment period. Importantly, no patients in either study discontinued treatment due to weight gain. Significantly, a pooled analysis of the metabolic parameters across both studies showed that the effects of adjunctive aripiprazole on mean change in body weight did not appear to be specific to any baseline body mass index category or to any dose of aripiprazole (Berman et al 2007a). Furthermore, the increase in body weight occurred in the absence of a clinically significant increase in other metabolic measures (Berman et al 2007a). During the double-blind, randomized treatment phase in Berman et al, two patients experienced suicidal ideation, both in subjects who were receiving placebo (Berman et al 2007a). In the second study, no suicide-related AEs were reported with either adjunctive aripiprazole or placebo during the double-blind randomized phase.

No new cases of tardive dyskinesia were observed during the study; however, the 6-week duration of the trials may underestimate rates observed with long-term treatment. Correll et al reviewed rates of tardive dyskinesia observed with the second-generation antipsychotics, and concluded that these rates (0.8% in non-elderly adults) were substantially lower than those observed with conventional agents (5.4% in adults on haloperidol) (Correll et al 2004). Nevertheless, tardive dyskinesia can occur with all antipsychotic agents. The rate of tardive dyskinesia in populations with MDD treated with aripiprazole in the 1-year safety study (0.4%) (Berman et al 2008) was comparable to what has been reported for other atypicals in other populations in long-term studies (0.8%; Correll 2004) and lower than that seen with olanzapine–fluoxetine combination (1.8%) (Corya et al 2003). All of the cases resolved within 45 days of discontinuing medication.

Functioning

In addition to efficacy for symptoms of major depression, an ideal treatment will also reduce or minimize functional disability associated with the disorder. The Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) is an instrument used to assess the impact of illness-related impairment in three domains of functioning – work/school, social life, and family life/home responsibilities. Patients with MDD display greater functional impairment in social and family areas rather than work (Kessler et al 2003). Both the double-blind studies used the SDS and found that adjunctive treatment of standard ADT with aripiprazole improved family and social functioning (both p < 0.05). In addition, adjunctive aripiprazole treatment did not adversely affect sexual functioning in either study, as measured on the Sexual Function Index (SFI) scale, and resulted in significant improvements in ‘interest in sex’ (p < 0.001) and ‘sexual satisfaction’ (p = 0.015) items during one of the studies (Marcus et al 2008).

Conclusions

Achieving remission early in the course of depression is critical for the success of long-term treatment outcomes. A range of augmentation and combination strategies have been used in order to increase the chance of achieving remission. Indeed, for some patients, initiating combination and augmentation strategies earlier in treatment may increase the likelihood of remission; however, this strategy has not been well studied.

Although augmentation and combination strategies are commonly used for treatment of MDD, until recently there were relatively few large, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials to support this approach. As reviewed above, even the controlled trials used sample sizes that were usually very small. In addition, until recently treatment resistance was often poorly defined, if at all. The studies of the atypical antipsychotics are the first class of augmentation strategies to attempt to define unresponsive depression using adequate historical and prospective antidepressant trials. There is now growing evidence for the efficacy of atypical antipsychotics for adjunctive treatment of depressive symptoms of MDD in the absence of psychotic symptoms. In two large clinical trials, the addition of aripiprazole to standard ADT monotherapy was significantly more effective than the addition of placebo for the treatment of depression in patients with MDD who failed to respond to one prospective ADT trial and one to three historical trials during the current episode. Whether aripiprazole is more effective than other atypical agents has not been studied. Nor has the efficacy of aripiprazole been compared with lithium, thyroid or other augmentation strategies. These questions, as well as the long-term use of these agents in depression, await further study.

Key clinical questions

How do you decide when to augment versus switch in MDD?

Clinical wisdom, as reflected in surveys and treatment choice in STAR*D, suggests that augmentation is favored in partial responders. This is primarily based on practical considerations – namely, that addition of a second agent allows the initial response to be maintained while a switch might not.

However, in patients with minimal response, data comparing augmentation strategies with switch options are lacking.

The tolerability of the initial agent plays a role here. A poorly tolerated initial agent suggests a switch.

Is there an accepted definition of inadequate treatment response/partial response or treatment-resistant patients?

No definition of treatment-resistant depression has been adequately validated.

Lack of response to a minimum of two adequate trials of medication from different classes has been proposed as the basic definition of treatment resistance in MDD (Thase 2002).

The STAR*D findings suggest that remission rates drop considerably after two failed trials, supporting the recommendation that two failed trials defines treatment resistance.

How does onset of action influence your decision when choosing a pharmacologic agent for MDD?

Antidepressant medications are generally considered to have a delayed onset of action.

In STAR*D, one half of the patients achieved remission during weeks 6–12.

However, evidence of initial response can be observed in 1 or 2 weeks.

Compared with switching, augmentation strategies may be more rapid, especially since no time is lost tapering the initial treatment.

Early response to antidepressants is an unmet medical need and one that should be addressed in future treatment paradigms.

How can we manage side effects of adjunctive aripiprazole therapy?

The key to successful treatment with any agent is awareness of the clinical profile and education of the patient about the drugs used.

As clinical experience with aripiprazole has grown, some management strategies for the treatment of side effects have emerged.

Although few predictors of akathisia have been identified, in patients with a history of akathisia, a more gradual dosing strategy might be used. Rates of akathisia appear higher in patients under age 40 years.

For mild–moderate akathisia, dose reduction is an option if it does not compromise efficacy. If tolerable, akathisia appears to abate with time.

Concomitant medications (eg, benzodiazepines, beta-blockers, or anticholinergic agents) may be useful for more severe akathisia but their efficacy in this situation is based more on clinical experience than controlled trials. Given high rates of improvement with time, it is not clear that these interventions are better than time.

Footnotes

Disclosures

During the past 12 months, Dr Nelson has been a consultant to or on the advisory boards of Bristol-Myers Squibb, Corcept, Eli Lilly, Merck, Orexigen; receives research support from NIMH; and receives no lecture honoraria. Dr Pikalov is an employee of Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc. Dr Berman is an employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Editorial support for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Ogilvy Healthworld Medical Education; funding was provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

References

- Abilify. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company/Otsuka America Pharmaceutical Inc, Aripiprazole (Abilify) Prescribing Information. Bristol-Myers Squibb Co and Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc: Princeton, NJ; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (revision). American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G. Should depression be managed as a chronic disease? BMJ. 2001;322:419–21. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7283.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson R, Offman HJ, Joffe RT, et al. Triiodothyronine augmentation in the treatment of refractory depression. A meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:842–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830090090013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association [APA] Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barbee JG, Conrad EJ, Jamhour NJ. Aripiprazole augmentation in treatment-resistant depression. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2004;16:189–94. doi: 10.1080/10401230490521954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmaker RH, Agam G. Major depressive disorder. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:55–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra073096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman R, Fava M, Baker RA, et al. Metabolic effects of aripiprazole adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder subpopulations (Studies CN138–139 and CN138–163). Presented at the Annual Meeting of American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; Boca Raton, Florida, USA. 2007a. [Google Scholar]

- Berman RM, Kaplita S, McQuade RD, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of open-label aripiprazole augmentation of antidepressant therapy in major depressive Disorder (CN138–164). Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC, USA. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman RM, Marcus RN, Swanink R, et al. The efficacy and safety of aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007b;68:843–53. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blier P, Gobbi G, Turcotte JE. A double-blind prolongation study of the combined treatment of depression with mirtazapine and paroxetine. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit; Boca Raton, Florida, USA. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Boulton DW, Balch AH, Royzman K, et al. The pharmacokinetics of standard antidepressants with aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy: studies in healthy subjects and in patients with major depressive disorder. J Psychopharmacol. doi: 10.1177/0269881108096522. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter LL, Yasmin S, Price LH. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of antidepressant augmentation with mirtazapine. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:183–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppen A, Bailey J. Enhancement of the antidepressant action of fluoxetine by folic acid: a randomised, placebo controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2000;60:121–30. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Leucht S, Kane JM. Lower risk for tardive dyskinesia associated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review of 1-year studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:414–25. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corya SA, Andersen SW, Detke HC, et al. Long-term antidepressant efficacy and safety of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination: a 76-week open-label study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1349–56. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley NA, Bauer M. Acceleration and augmentation of antidepressants with lithium for depressive disorders: two meta-analyses of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:935–40. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KL, Charney D, Coyle JT, et al. Neuropsychopharmacology: The Fifth Generation of Progress. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- De Montigny C, Grunberg F, Mayer A, et al. Lithium induces rapid relief of depression in tricyclic antidepressant drug non-responders. Br J Psychiatry. 1981;138:252–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.138.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado PL, Charney DS, Price LH, et al. Serotonin function and the mechanism of antidepressant action. Reversal of antidepressant-induced remission by rapid depletion of plasma tryptophan. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:411–18. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810170011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias RS, Kerr-Correa F, Moreno RA, et al. Efficacy of hormone therapy with and without methyltestosterone augmentation of venlafaxine in the treatment of postmenopausal depression: a double-blind controlled pilot study. Menopause. 2006;13:202–11. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000198491.34371.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M. Diagnosis and definition of treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:649–59. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, et al. Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:342–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. Background and rationale for the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2003;26:457–94. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(02)00107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Thase ME, DeBattista C. A multicenter, placebo-controlled study of modafinil augmentation in partial responders to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with persistent fatigue and sleepiness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:85–93. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Talajic M. Depression following myocardial infarction. Impact on 6-month survival. JAMA. 1993;270:1819–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, et al. The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1465–75. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpole LH, Williams JW, Jr, Olsen MK, et al. Improving depression outcomes in older adults with comorbid medical illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellerstein DJ, Batchelder S, Hyler S, et al. Aripiprazole as an adjunctive treatment for refractory unipolar depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;32:744–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan S, Koprivica V, Dunn R, et al. In vivo effects of aripiprazole on cortical and striatal dopaminergic and serotonergic function. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;483:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Lin EH, Kroenke K. The association of depression and anxiety with medical symptom burden in patients with chronic medical illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:147–55. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Schulberg H. Epidemiology of depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14:237–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(92)90094-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer DJ. Long-term treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52:28–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer DJ. The pharmacological management of depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2005;7:191–205. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2005.7.3/dkupfer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landen M, Bjorling G, Agren H, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of buspirone in combination with an SSRI in patients with treatment-refractory depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:664–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PY, Su KP. A meta-analytic review of double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressant efficacy of omega-3 fatty acids. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1056–61. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus R, McQuade R, Carson W, et al. The efficacy and safety of aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder: a second multicenter, randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:156–65. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31816774f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Fava M, et al. Tranylcypromine versus venlafaxine plus mirtazapine following three failed antidepressant medication trials for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1531–41. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller HL, Delgado PL, Salomon RM, et al. Clinical and biochemical effects of catecholamine depletion on antidepressant-induced remission of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:117–28. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830020031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno FA, Gelenberg AJ, Bachar K, et al. Pindolol augmentation of treatment-resistant depressed patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:437–9. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan ML, Cook IA, Rapkin AJ, et al. Estrogen augmentation of antidepressants in perimenopausal depression: a pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:774–80. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris PL, Robinson RG, Andrzejewski P, et al. Association of depression with 10-year poststroke mortality. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:124–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:851–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Evidence-based health policy – lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Science. 1996;274:740–3. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349:1498–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JC. The use of antipsychotic drugs in the treatment of depression. In: Zohar J, Belmaker RH, editors. Treating Resistant Depression. New York: PMA Publishing Corp; 1987. pp. 131–46. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JC, Kaplita S, Tran QV, et al. Safety and tolerability of adjunctive aripiprazole in major depressive disorder: a pooled analysis (Studies CN138–139 and CN138–163). Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; Boca Raton, Florida, USA. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JC, Mazure CM, Jatlow PI, et al. Combining norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibition mechanisms for treatment of depression: a double-blind, randomized study. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JC, Portera L, Leon AC. Are there differences in the symptoms that respond to a selective serotonin or norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor? Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1535–42. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, et al. A comparison of lithium and T(3) augmentation following two failed medication treatments for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1519–530. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nierenberg AA, Papakostas GI, Petersen T, et al. Lithium augmentation of nortriptyline for subjects resistant to multiple antidepressants. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:92–5. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200302000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel PH, Williams JW, Jr, Unutzer J, et al. Depression and comorbid illness in elderly primary care patients: impact on multiple domains of health status and well-being. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:555–62. doi: 10.1370/afm.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutt D, Demyttenaere K, Janka Z, et al. The other face of depression, reduced positive affect: the role of catecholamines in causation and cure. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21:461–71. doi: 10.1177/0269881106069938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutt DJ. The role of dopamine and norepinephrine in depression and antidepressant treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 6):3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostroff RB, Nelson JC. Risperidone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in major depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:256–9. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pae CU, Patkar AA, Jun TY, et al. Aripiprazole augmentation for treatment of patients with inadequate antidepressants response. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24:522–6. doi: 10.1002/da.20244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papakostas GI. Dopaminergic-based pharmacotherapies for depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;16:391–402. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papakostas GI, Petersen T, Denninger JW, et al. Psychosocial functioning during the treatment of major depressive disorder with fluoxetine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:507–11. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000138761.85363.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papakostas GI, Petersen TJ, Kinrys G, et al. Aripiprazole augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1326–30. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papakostas GI, Shelton RC, Smith J, et al. Augmentation of antidepressants with atypical antipsychotic medications for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007a;68:826–31. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papakostas GI, Thase ME, Fava M, et al. Are antidepressant drugs that combine serotonergic and noradrenergic mechanisms of action more effective than the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treating major depressive disorder? A meta-analysis of studies of newer agents. Biol Psychiatry. 2007b;62:1217–27. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patkar AA, Masand PS, Pae CU, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of augmentation with an extended release formulation of methylphenidate in outpatients with treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006a;26:653–6. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000246212.03530.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patkar AA, Peindl K, Mago R, et al. An open-label, rater-blinded, augmentation study of aripiprazole in treatment-resistant depression. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2006b;8:82–7. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v08n0205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paykel ES, Ramana R, Cooper Z, et al. Residual symptoms after partial remission: an important outcome in depression. Psychol Med. 1995;25:1171–80. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700033146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez V, Soler J, Puigdemont D, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of pindolol augmentation in depressive patients resistant to serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Grup de Recerca en Trastorns Afectius. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:375–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin A, Schulterbrandt JG, Reatig N, et al. Differential response to chlorpromazine, imipramine, and placebo. A study of subgroups of hospitalized depressed patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1970;23:164–73. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1970.01750020068009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ressler KJ, Nemeroff CB. Role of serotonergic and noradrenergic systems in the pathophysiology of depression and anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2000;12(Suppl 1):2–19. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:1+<2::AID-DA2>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ. STAR*D: what have we learned? Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:201–4. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D): rationale and design. Control Clin Trials. 2004;25:119–42. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1905–17. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford B, Sneed J, Miyazaki M, et al. An open trial of aripiprazole augmentation for SSRI non-remitters with late-life depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22:986–91. doi: 10.1002/gps.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schule C, Baghai TC, Eser D, et al. Mirtazapine monotherapy versus combination therapy with mirtazapine and aripiprazole in depressed patients without psychotic features: a 4-week open-label parallel-group study. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2007;8:112–22. doi: 10.1080/15622970601136203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro DA, Renock S, Arrington E, et al. Aripiprazole, a novel atypical antipsychotic drug with a unique and robust pharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1400–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton RC, Tollefson GD, Tohen M, et al. A novel augmentation strategy for treating resistant major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:131–4. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon JS, Nemeroff CB. Aripiprazole augmentation of antidepressants for the treatment of partially responding and nonresponding patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1216–20. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:229–33. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl M. Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Applications. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stark AD, Jordan S, Allers KA, et al. Interaction of the novel antipsychotic aripiprazole with 5-HT(1A) and 5-HT (2A) receptors: functional receptor-binding and in vivo electrophysiological studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;190:373–82. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0621-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, et al. Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. JAMA. 2003;289:3135–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1552–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terao T. Small doses of aripiprazole augmentation of antidepressants: three case reports. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:843–53. [Google Scholar]

- Thase ME. What role do atypical antipsychotic drugs have in treatment-resistant depression? J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:95–103. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thase ME, Trivedi MH, Swanink R, et al. Efficacy of adjunctive aripiprazole in major depressive disorder: a pooled subpopulation analysis (Studies CN138–139 and CN138–163). Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; Boca Raton, Florida, USA. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1243–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthington JJ, 3rd, Kinrys G, Wygant LE, et al. Aripiprazole as an augmentor of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in depression and anxiety disorder patients. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;20:9–11. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]